Abstract

Circular RNA (circRNA) is a unique closed ring structure of noncoding RNA. Although many human diseases have been confirmed to be inextricably linked with circRNAs, whether circRNAs have a potential regulatory function in the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs) remains to be further elucidated. In a previous study by our team, all the differentially expressed circRNAs and messenger RNAs (mRNAs) involved in the osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs were identified via high-throughput sequencing, and a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) regulatory network was constructed via bioinformatics analysis. The circRNA_1809/miR-370-3p/Kitlg axis may be involved in regulating the osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs. In this study, gene knockdown/overexpression, small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection and mimic/inhibitor treatment were used to evaluate the regulatory effects of circRNA_1809 on the miR-370-3p/Kitlg pathway and the osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (rBMMSCs) in vitro. The results revealed that circRNA_1809 was upregulated and that miR-370-3p was downregulated during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. The low expression of circRNA_1809 significantly downregulated the expression of Kitlg and decreased the protein expression of ALP and RUNX2. The expression of miR-370-3p was negatively correlated with the expression of Kitlg in rBMMSCs and the ability to undergo osteogenic differentiation. In addition, a dual-luciferase assay confirmed the binding of miR-370-3p and circRNA_1809, and si-circRNA_1809 + miR-370-3p inhibitor cotransfection reversed some of the downregulation of Kitlg induced by si-circRNA_1809, whereas si-circRNA_1809 + miR-370-3p mimic increased the downregulation of Kitlg. Therefore, circRNA_1809 may promote the expression of Kitlg by regulating miR-370-3p and subsequently promote the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone defects are a common problem in clinical treatment. At present, autogenous bone transplantation is the gold standard for the treatment of bone defects. However, owing to the influence of limited materials, donor site injury and postoperative complications, it is difficult to repair bone defects beyond the critical size by autogenous bone transplantation, which limits its clinical application1,2. The goal of regenerative repair is to combine tissue engineering scaffold materials with partially defective tissues, and new bone and soft tissue can actively multiply and differentiate from tissue engineering scaffold materials3.

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs) are widely used in bone tissue engineering and regenerative medicine because of their multidifferentiation potential and easy access. Activating the osteogenic differentiation of stem cells is a promising research direction to promote bone tissue regeneration and repair4. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) is an important indicator of the ability of cells to undergo osteogenic differentiation. Its activity is often used to measure the ability of cells to undergo osteogenic differentiation. It is recognized as a marker of the early osteogenic differentiation of cells5,6. Currently, among the BMP subtype factors, BMP-2 has the strongest ability to induce direct bone formation and has the strongest activity among the osteogenesis-inducing growth factors7. Studies have shown that BMP-2 can not only promote the proliferation and differentiation of tissue cells but also induce stem cells to differentiate into osteoblasts. BMP-2 levels rise rapidly at the very early stage when mesenchymal stem cells are exposed to osteogenic induction stimulation8. RUNt-associated transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), a key marker of the osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs, plays a core regulatory role in the differentiation of BMMSCs into osteoblasts. Many studies have shown that, in the early stage of osteogenesis induction, RUNX2 expression is rapidly upregulated, which induces the expression of osteocalcin, osteopontin and a series of osteoblastation-related genes and promotes extracellular matrix mineralization. When RUNX2 expression is inhibited, the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMMSCs is significantly decreased. In studies of osteoporosis and bone defect repair, RUNX2 expression is closely related to bone formation ability and is an important indicator for evaluating the osteogenic differentiation status of BMMSCs9.

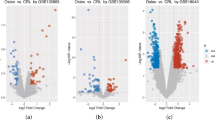

Many experiments have shown that noncoding RNAs can specifically regulate gene expression through a variety of mechanisms, including the regulation of biological activities such as the proliferation and differentiation of new bone tissues and cells10,11. These characteristics have made noncoding RNAs a focus in the field of RNA research in recent years12,13. Among them, circular RNAs (circRNAs) are highly stable and resistant to RNA debranching enzymes and RNA exonucleases because they lack 2ʹ to 5ʹ carbon bonds and are free of 3ʹ or 5ʹ ends14. CircRNAs are not only more stable than common linear RNAs but are also ten-fold more abundant than linear RNAs in some cells15. As a class of endogenous noncoding RNA molecules, circRNAs are closely related to a variety of diseases. Their special ring structure endows them with stability and tissue specificity so that they plays an important role in the occurrence and development of diseases16. High-throughput sequencing can be used to analyse the differential expression of circRNAs under different conditions. By comparing RNA-seq data from different tissues, cell types, developmental stages or disease states, differentially expressed circRNAs can be identified, which helps to understand disease pathogenesis and provide potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases. In previous studies, we identified all the differentially expressed circRNAs and mRNAs during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs through high-throughput sequencing, and the results revealed that among the upregulated circRNAs, circRNA_1809 presented the greatest upregulation. The results of the mRNA assessment revealed that the Kitlg gene was the most significantly upregulated gene among the differentially expressed mRNAs. Enrichment analysis was used to explore the signalling pathways that might regulate the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs, and bioinformatics analysis was used to construct a ceRNA regulatory network. circRNA_1809 may be involved in the osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs by targeting the Kitlg gene through miR-370-3p17.

In this study, by silencing circRNA_1809 and silencing/overexpressing miR-370-3p in rBMMSCs by transfection, we explored the mechanism by which circRNA_1809 regulates the osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs through miR-370-3p. This study provides new evidence and a theoretical basis for the application of circular RNA in bone defect repair.

Methods

Isolation, culture and osteogenic induction of rBMMSCs

Four-week-old male SPF-grade SD rats, with body weights of approximately 80–100 g, were provided by the Animal Experimental Center of Xinjiang Medical University (K202409-04). The animal studies were conducted following ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In vivo Experiments).All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. SD rats were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 1% pentobarbital solution (Sigma‒Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The hindlimbs were removed, and the soft tissues of the tibia and femur were removed in an aseptic environment. The femurs and tibias of the rats were separated, and the bone fragments were washed twice with PBS solution. The two ends of the bone were cut to expose the bone marrow cavity, the bone marrow cavity was rinsed repeatedly with α-MEM (Gibco, Grand Island, USA) containing 15% foetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, USA), the washed bone marrow fluid was blown evenly from the bone shafts, and the precipitate was collected after centrifugation at 1200 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min. The isolated rat BMMSCs were inoculated in a 25 cm2 tissue culture bottle containing 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin‒streptomycin (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel). α-MEM was added, and the mixture was cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 wet incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA).

Before osteogenic induction, all the BMMSCs were subjected to flow cytometry to confirm that the surface markers of the isolated rBMMSCs met the stem cell standards and that the purity and viability were greater than 90%. Third-generation rat BMMSCs were inoculated into six-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well from the cell bottle, and 2 mL of medium was added to each well to continue the culture. When the cells were 80% confluent, the culture medium was removed from the well, and the cells were rinsed twice with PBS solution. Two millilitres of osteogenic differentiation medium (Cyagen Biosciences, Santa Clara, California) was added to each well in the osteogenic induction group, while normal medium was added to the control group. The culture medium was changed every 3 days, and the cells were collected at a specified time point.

Construction of si-circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p inhibitor/mimic plasmids

The plasmid vector used in the cost-effective experiment was designed by GenPharma Company (Shanghai, China). The si-circRNA_1809 target sequence (5ʹ-3ʹ) was CGTGTCAGCAGTT. The miR-370-3p inhibitor target sequence (5ʹ-3ʹ) was CGTGTCAGCAGTT. The MiR-370-3p mimic had the target sequence (5ʹ-3ʹ) GCTGCTGGTGACTGT. The designed plasmid was constructed by Jemma and stored in bacteria maintained in glycerol. The bacteria were cultured by shaking at 220 rpm in a 37 °C constant temperature shaker for 12 h before use, and the plasmid was extracted from the bacterial mixture to ensure the transfection efficiency.

Plasmid transfection of rBMMSCs

P3 generation cells were inoculated in a six-well plate, and the cell density reached 5 × 105 in each well. The cells were transfected when the cells were in the logarithmic growth phase. The following experiments were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the steps were as follows: In the dark, 100 μL of special Opti-MEM (Gibco, Grand Island, USA) was added to each EP tube for transfection, followed by the addition of 5 μL of LTX transfection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). The rinsed cell suspension was mixed by pipetting. After being mixed well, 100 μL of Opti-MEM was added to the tube, and 2.5 μL of PLUS reagent was added. The ratio of plasmid DNA to PLUS reagent was 1:1. The dose of plasmid needed in each group was calculated according to the formula v = c/ρ (v represents the volume of plasmid solution required for each set of experiments, c represents the concentration of plasmid DNA, which is a parameter known before the experiment, and ρ represents the number of plasmids that should be contained in the cell culture system per unit volume). After the addition of plasmid DNA, the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 ~ 10 min. The plasmid transfection reagent was mixed circularly, and the plasmid DNA was added evenly to each well. The six-well plate was shaken slightly to mix the transfection solution with the cell culture medium fully and evenly, the plasmid name and transfection time were clearly marked, and the plate was cultured in an incubator. Thirty-six hours after transfection, the transfected cells were observed via laser confocal microscopy. The BMMSCs successfully transfected with the DNA plasmid expressed green fluorescence, and the transfection rate was calculated according to the results (transfection rate = the number of fluorescent cells/total cells × 100%).

Alizarin red staining and quantification

On the 7th day of osteogenic induction, the culture medium from the six-well plate was removed and discarded, and the rat BMMSCs were washed twice with PBS. Then, 0.5 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde solution was added to each well, and the samples were fixed for 30 min at 4 °C. The cells were washed twice with distilled water, and 0.5 mL of 0.1% alizarin red (Solarbio, Beijing, China) was added for staining for 30 min. The alizarin red dye solution was removed, the cells were washed with distilled water three times, and images of the cells were acquired under a microscope. The dye was dissolved in 1 mL of 10% cetylpyridine (Sigma‒Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) for 1 h for decolorization. ImageJ (V1.8.0.112) was used to quantify the ARS-stained areas. The specific steps were as follows: the picture type was converted to an RGB stack, and the positive area was selected in the “Adjust” threshold. The “measure” was used to obtain the “%Area”. GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 was used to draw charts and analyse the value of the %Area directly.

Von Kossa staining and quantification

The BMMSCs were washed twice with PBS, and after 30 min, they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 4 °C. The fixed cells were washed twice with distilled water and incubated with 5% silver nitrate (Sigma‒Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) for 1 h under ultraviolet radiation. The cells were stained with 5% sodium thiosulfate solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 5 min, observed under a microscope and photographed. ImageJ was used to quantify the Von Kossa-stained areas. The specific steps were as follows: the picture type was converted to an RGB stack, and the positive area was selected in the “Adjust” threshold. The “measure” was used to obtain the “%Area”. GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 was used to draw charts and analyse the value of the %Area directly.

Fluorescence quantitative PCR

The cell precipitates were collected and lysed with TRIzol reagent (Sigma‒Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). The cells were transferred to an enzyme-free EP tube and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Chloroform was added to the cell lysate, which was shaken for 15 s, incubated for 3 min at room temperature, and centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation, delamination of the solution, which included a clear and transparent upper RNA layer, a white film-like middle protein layer and a pink transparent lower DNA layer, was observed in the bottle. Anhydrous ethanol solution was added to the collected RNA supernatant, and the mixture was transferred to an RNeasy microcolumn (QIAGEN, Duesseldorf, Germany). The mixture was subsequently centrifuged at room temperature for 15 s, after which the waste liquid in the collection tube was discarded. The RWT was added to the RNeasy microcolumn and centrifuged at room temperature for 15 s, and the waste liquid in the collection tube was discarded. RPE was added to the RNeasy microcolumn and centrifuged at room temperature for 15 s, and the waste liquid in the collection tube was discarded. The new collection tube was placed into the RNeasy microcolumn, and the membrane was further dried by full-speed centrifugation for 1 min. The RNeasy microcolumn was transferred to a new EP tube, and 30–50 μL of enzyme-free water was added to the RNeasy microcolumn. One minute of centrifugation was carried out at room temperature until the elution was complete. At this time, RNA was extracted from the EP tube, labelled, and stored at − 80 °C.

The miRcute Plus miRNA First Strand cDNA Kit (QIAGEN, Duesseldorf, Germany) was used, and reverse transcription of the first strand cDNA of the miRNA was carried out via the tail-adding method. The specific procedure of the experiment was as follows: first, E. coli poly(A) polymerase was used to add poly(A) to the end of miRNA3’, then reverse transcription was carried out via the universal reverse transcription primer oligo(dT)-Universal Tag method, and finally, the first chain of cDNA matched with the miRNA was formed. The miRcute Plus miRNA SYBR Green qPCR Kit (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) was used strictly according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Eight rows of tubes were arranged and marked according to the target gene, the mixed system was added, and the mixture was shaken fully to remove bubbles. After a short period of centrifugation, the eight-row tube was placed in an ABI Quant Studio 6 Flex fluorescence quantitative PCR (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) according to the 20 μL reaction system and the corresponding procedure. The internal reference gene of the miRNA was U6, and the relative expression was calculated by the 2−△△Ct method. The results were obtained from three independent experiments, and each gene was analysed in triplicate. The primer sequences of related genes can be found in Table 1.

Protein immunoblotting

After 36 h of plasmid transfection in each group, the cells were scraped off along the bottom of the six-well plate with a cell scraper and suspended in PBS solution. The samples were subsequently centrifuged at 1000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min, after which the supernatant was discarded. After PMSF and RIPA lysis buffer (PMSF: RIPA = 1:100, Solarbio, China) were added to the cells and incubated for 30 min on ice, the mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. Protein quantification was carried out according to the instructions of the BCA protein quantification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). In accordance with the protein concentration of each group, the appropriate amount of 5× loading buffer solution was added, and the mixture was boiled for 10 min at 100 °C to cause denaturation. After the samples returned to room temperature, they were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. SDS‒PAGE electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) was performed. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes, and Western blot experiments were carried out. The PVDF membrane (Merck Millipore, Billerica, USA) was blocked with 5% skim milk powder at room temperature for 1 h and washed with TBST three times, after which the rabbit monoclonal antibodies against GAPDH (1:10,000, ab181602, Abcam), ALP (1:2000, ab186421, Abcam), RUNX2 (1:1000, ab236639, Abcam), and Kitlg (1 µg/mL, ab64677, Abcam) were added. The samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C, washed with TBST three times, supplemented with rabbit anti-rat enzyme-labelled secondary antibody (1:5000, ab6734, Abcam), and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. ECL chromogenic solution (AB133406; Abcam) and a fully automated chemiluminescence system were used for immunoblot imaging. The intensity of each band was quantitatively analysed via ImageJ, and the differences were calculated.

Dual-luciferase reporter gene detection

The plasmid psiCHECK 2 was used as the skeleton vector, and the target gene circ_1809 was inserted into it to construct the circ_1809 dual-luciferase vectors circ_1809-WT-psiCHECK 2 and circ_1809-MUT-psiCHECK 2. The template was derived from the circ_1809 gene and was verified by sequencing. The circ_1809 gene sequence was selected for primer design (see Table 2 for the primer sequence) to construct a gene subclone vector. The bacterial mixture containing the vector plasmid was cultured overnight, and the plasmid was extracted from 3–5 mL of fresh bacterial mixture. The specific reference method for plasmid extraction can be found in the plasmid instruction manual (QIAGEN, Duesseldorf, Germany). One microgram of the fresh plasmid was removed, and the corresponding restriction endonuclease sites in the plasmid were cleaved by double endonuclease digestion. The enzyme digestion reaction was carried out at 37 °C for approximately 3 h. The reaction was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the effect of the enzyme digestion was verified. After agarose gel electrophoresis, the gel was recovered, and under an ultraviolet lamp, the gel containing the target fragment was removed. The gel weight was calculated by subtracting the weight of the empty tube from the total weight, and the gel was melted thoroughly by adding binding solution in a 65 °C water bath. All the previous liquids were transferred to the filter column, and the column was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 s. The liquid in the tube was subsequently discarded, and 500 μL of WA solution was added to the filter column. The mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 s. The liquid in the tube was discarded, and 50 μL of wash solution was added to the column. The mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 s. The mixture was then left for 3 min. The filter column was replaced with a new EP tube (1.5 mL) and placed at room temperature. Next, 35 μL of ddH2O solution was added to the column, and the concentration was determined after 5 min and centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 1.5 min. The recovered mixture was amplified to complete the ligation between the target gene and the vector. The plasmid was extracted and subsequently transfected into 293 T cells. After the reporter gene-containing cells were mixed evenly, lysis buffer was added, and the cells were fully lysed. After lysis was fully complete, the samples were centrifuged for 3–5 min at 10,000–15,000×g, and the amount of the supernatant was determined. For detection of luciferase in the lysed cells, The temperature of the samples was allowed to equilibrate to the indoor temperature, the multifunctional enzyme labelling instrument or chemiluminescence instrument was turned on, and the interval was set to 2 s, with a determination time of 10 s. Samples (20–100 μL) were taken for analysis. One hundred microlitres of firefly luciferase detection reagent was added, and the relative light units (RLUs) were determined after the mixture was mixed evenly with a liquid transfer gun. After the determination of firefly luciferase activity, the same amount of sea kidney luciferase detection solution was added to determine the RLUs. The ratio of the two types of luciferases was calculated, and the differences in the ratios of the different groups were compared.

Statistical analysis

All the data are representative experimental results, and each experiment had three replicates. The experimental data were processed and analysed via SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The measurement data are expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means (means ± SEMs), and the normality of the data was tested via the Shapiro‒Wilk test. A t test (independent-samples t test) of independent samples was used if the two groups of data were normally distributed (P > 0.05), and the Mann‒Whitney rank sum test (Mann‒Whitney U test) was used if the data of the two groups were not normally distributed (P < 0.05). Multiple groups of data were tested by a test of homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test), and the differences among multiple groups of data were compared by single-factor analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA). For the comparison of multiple groups of data, the LSD test was used if it conformed to the assumption of homogeneity of variance (P > 0.05), and Dunnett’s T3 test was used if it did not conform to the assumption of homogeneity of variance (P < 0.05).

Results

CircRNA_1809 is upregulated and miR-370-3p is downregulated during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs

The dynamic expression of osteogenic markers (ALP, RUNX2), circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p in rBMMSCs was assessed via fluorescence quantitative PCR at 3, 7 and 14 days after osteogenic differentiation. The results revealed that the expression of both ALP and RUNX2 increased during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs (Fig. 1A, B). CircRNA_1809 was upregulated, with its expression gradually increasing. However, the expression of miR-370-3p during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs decreased significantly on the 14th day (Fig. 1C, D). Next, to explore the regulatory role of circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p in the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs, we constructed si-circRNA_1809, miR-370-3p mimic and miR-370-3p inhibitor plasmids to transfect rBMMSCs. The si-circRNA_1809 plasmid and the control vector were transfected into rBMMSCs. Twenty-four hours after transfection, RT‒PCR confirmed that the expression of circRNA_1809 in the si-circRNA_1809 group was significantly lower than that in the control group (Fig. 1E). After the rBMMSCs were transfected with the miR-370-3p mimic plasmid or the miR-370-3p inhibitor plasmid, the fluorescence quantitative PCR results revealed that the expression of miR-370-3p in the miR-370-3p overexpression group was significantly increased and was almost twice as high as that in the control group. However, the expression of miR-370-3p in the miR-370-3p-knockdown group was significantly decreased (Fig. 1F). The plasmids we constructed successfully induced the silencing or overexpression of circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p.

The expression of rBMMSCs changes during osteogenesis. The dynamic expression levels of the osteogenic markers ALP (A), RUNX2 (B), circRNA_1809 (C) and miR-370-3p (D) in rBMMSCs were assessed via fluorescence quantitative PCR at 3 days, 7 days and 14 days after osteogenic differentiation. (E) The expression of circRNA_1809 in rBMMSCs after knocking down circRNA_1809. (F) The expression of miR-370-3p in rBMMSCs after miR-370-3p inhibitor/mimic treatment. The statistical results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

CircRNA_1809 knockdown inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs

The expression of circRNA_1809 increased significantly during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. We speculated that silencing circRNA_1809 may inhibit the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. ARS staining (Fig. 2A) and Von Kossa staining (Fig. 2B) revealed that on the 14th day, the area of alizarin red staining in the si-circRNA_1809 group was lower than that in the control group, and the difference was greater than that on the 7th day. Similarly, the amount of matrix mineralization in the si-circRNA_1809 group was significantly lower than that in the control group on the 7th and 14th days. Quantitative analysis of the images revealed that the knockdown of circRNA_1809 significantly reduced the calcium deposition (Fig. 2C) and matrix mineralization (Fig. 2D) of the rBMMSCs on the 7th and 14th days of osteogenic differentiation. In addition, the fluorescence quantitative PCR results revealed that the mRNA expression of the osteogenic markers ALP and RUNX2 in the si-circRNA_1809 group was significantly lower than that in the control group 14 days after induction (Fig. 2E). The Western blot results were consistent with the results of the fluorescence-based quantitative PCR (Fig. 2F). The results of the quantitative analysis of the ALP and RUNX2 proteins confirmed that the knockdown of circRNA_1809 decreased the osteogenic ability of the rBMMSCs (Fig. 2G). These findings suggest that knocking down circRNA_1809 inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs and that the expression of circRNA_1809 is positively correlated with the expression of osteogenic-related genes.

circRNA_1809 knockdown inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. (A) Alizarin red staining of rBMMSCs on the 7th and 14th days of osteogenic differentiation; scale bar = 500 μm. (B) Von Kossa staining results on the 7th and 14th days of osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs; scale bar = 500 μm. (C) Quantitative image of the alizarin red staining results in (A). (D) Quantitative map of the Von Kossa staining results in (B). (E) The expression of ALP and RUNX2 mRNAs, which are osteogenic markers, was normalized to the expression of GAPDH on the 14th day of osteogenic differentiation in rBMMSCs after circRNA_1809 knockdown, as determined via fluorescence quantitative PCR. (F) Western blot analysis of the expression of the osteogenic markers ALP and RUNX2 on the 14th day of osteogenic differentiation in rBMMSCs after circRNA_1809 knockdown. (G) Expression was quantified via ImageJ and normalized to β-tubulin expression. The full-length blots are presented in the Supplementary Figures. All the samples were derived from the same experiment, and the gels/blots were processed in parallel. The statistical results are expressed as the means ± SEMs, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

miR-370-3p inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs

To determine whether miR-370-3p is involved in the regulation of the osteogenic differentiation of BMMSCs, a miR-370-3p mimic and a miR-370-3p inhibitor were transfected into rBMMSCs. ARS and Von Kossa staining (Fig. 3A, B) and the quantitative results (Fig. 3C, D) revealed that the number and size of calcium nodules in the miR-370-3p overexpression group were significantly lower than those in the control group at 7 and 14 days after rBMMSC osteogenesis induction, whereas the number and size of calcium nodules in the miR-370-3p knockdown group were greater than those in the control group. Over time, the difference in the calcification areas between the groups increased. The results revealed that the osteogenic differentiation ability of rBMMSCs decreased in the miR-370-3p overexpression group. miR-370-3p silencing promoted the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. Fluorescence quantitative PCR (Fig. 3E) and Western blotting (Fig. 3F, G) also confirmed that on the 14th day of osteogenic induction, the mRNA and protein expression levels of the osteogenic markers ALP and RUNX2 in the miR-370-3p overexpression group were significantly lower than those in the control group, while knocking down miR-370-3p could increase the gene expression of osteogenic markers.

miR-370-3p inhibits the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. (A) Alizarin red staining of rBMMSCs on the 7th and 14th days of osteogenic differentiation; scale bar = 500 μm. (B) Von Kossa staining results on the 7th and 14th days of osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs; scale bar = 500 μm. (C) Quantitative map of the alizarin red staining results in (A). (D) Quantitative map of the Von Kossa staining results in (B). (E) The expression of ALP and RUNX2 mRNAs, which are osteogenic markers, was normalized to the expression of GAPDH on the 14th day after the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs after the overexpression of miR-370-3p or its knockdown, as determined via fluorescence quantitative PCR. (F) Western blot analysis of the expression of the osteogenic markers ALP and RUNX2 on the 14th day of osteogenic differentiation in rBMMSCs after miR-370-3p overexpression or knockdown. (G) Expression was quantified via ImageJ and normalized to β-tubulin expression. The full-length blots are presented in the Supplementary Figures. All the samples were derived from the same experiment, and the gels/blots were processed in parallel. The statistical results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

circRNA_1809 affects osteogenic differentiation through miR-370-3p

After circRNA_1809 downregulation, the expression of miR-370-3p in undifferentiated rBMMSCs and osteoblast-differentiated rBMMSCs increased significantly (Fig. 4A). To confirm the interaction between circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p, we predicted the binding site (Fig. 4B) between circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p. A luciferase vector containing the wild-type or mutant circRNA_1809 binding site was constructed and cotransfected with the miR-370-3p mimic into rBMMSCs. Luciferase reporter gene analysis revealed that the luciferase activity of circRNA_1809 wild-type cells was strongly inhibited by the miR-370-3p mimic, whereas the luciferase activity of the mutant cell line was not affected by the miR-370-3p mimic (Fig. 4C). Next, we cotransfected the circRNA_1809 silencing vector with the miR-370-3p mimic/miR-370-3p inhibitor into rBMMSCs. The ability to undergo osteogenic differentiation was assessed by ARS and Von Kossa staining. Images (Fig. 4D, E) and quantitative results (Fig. 4F, G) are displayed. Compared with si-circRNA_1809 transfection alone, cotransfection with si-circRNA_1809 and the miR-370-3p mimic decreased the osteogenic ability of rBMMSCs, whereas the miR-370-3p inhibitor reversed the inhibitory effect of si-circRNA_1809 on the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. In addition, rBMMSCs were cotransfected with si-circRNA_1809 and a plasmid overexpressing miR-370-3p. Fourteen days after osteogenic induction, fluorescence quantitative PCR revealed that knocking down circRNA_1809 increased the inhibitory effect of miR-370-3p overexpression on rBMMSC osteogenic differentiation and strongly weakened the osteogenic differentiation ability of rBMMSCs. Compared with those in the si-circRNA_1809 group, the expression levels of ALP and RUNX2 in the si-circRNA_1809 + miR-370-3p mimic group decreased by more than half (Fig. 4H). In addition, Western blotting revealed that knocking down circRNA_1809 increased the inhibitory effect of the miR-370-3p mimic transfection on the expression of the osteogenic markers ALP and RUNX2 at the protein level(Fig. 4I, J). Similarly, we cotransfected low levels of circRNA_1809 and a plasmid for knockdown of miR-370-3p into rBMMSCs and found that knocking down circRNA_1809 partially reversed the promoting effect of miR-370-3p inhibitor transfection on the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. Compared with cells transfected with miR-370-3p inhibitor alone, ALP and RUNX2 expression levels (Fig. 4H-J).were decreased by cotransfection. These results suggest that miR-370-3p is a potential target of circRNA_1809 and plays an opposite role in regulating the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs.

circRNA_1809 acts as a molecular sponge for miR-370-3p. (A) Fluorescence quantitative PCR was used to assess the expression of miR-370-3p in rBMMSCs after knocking down circRNA_1809. (B) The binding site in circRNA_1809 for miR-370-3p. (C) Results of the circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p dual-luciferase assays. (D–G) Alizarin red and Von Kossa staining images and quantitative results for si-circRNA_1809-overexpressing/miR-370-3p-cotransfected rBMMSCs; scale bar = 500 μm. (H) On the 14th day after the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs cotransfected with si-circRNA_1809 and plasmids for knockdown or overexpression of miR-370-3p, the expression of ALP and RUNX2 mRNAs was normalized to the expression of GAPDH. (I) Western blot analysis of the expression of the osteogenic markers ALP and RUNX2 in rBMMSCs cotransfected with si-circRNA_1809 and plasmids for knockdown or overexpression of miR-370-3p on the 14th day of osteogenic differentiation. (J) Expression was quantified via ImageJ and normalized to β-tubulin expression. The full-length blots are presented in the Supplementary Figures. All the samples were derived from the same experiment, and the gels/blots were processed in parallel. The statistical results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

circRNA_1809 may regulate Kitlg expression through miR-370-3p

The TargetScan and miRDB sites were used to identify potential downstream targets of miR-370-3p. Notably, there is a potential binding site (Fig. 5A) for miR-370-3p in Kitlg. To verify whether Kitlg is involved in the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs, we used fluorescence PCR to observe the dynamic changes in Kitlg from the beginning of osteogenic induction to the 14th day of osteogenic induction. The results revealed that the mRNA level of the Kitlg gene increased, the expression of the Kitlg gene at each time point was greater than that of the rBMMSCs cultured in ordinary medium, and the difference gradually increased over time (Fig. 5B). Western blotting also revealed that the level of Kitlg protein in rBMMSCs cultured in osteogenic induction medium was significantly greater than that in those cultured in normal medium (Fig. 5C, D) at 14 days after osteogenic induction. To verify whether miR-370-3p acts on Kitlg, we transfected a miR-370-3p inhibitor and a miR-370-3p mimic into rBMMSCs. On the 14th day after osteogenic induction, fluorescence quantitative PCR (Fig. 5E) and Western blotting analysis (Fig. 5F, G) revealed that, compared with that in the control rBMMSCs, the expression of Kitlg was significantly greater in the cells transfected with the miR-370-3p inhibitor, whereas the expression of Kitlg was significantly lower in those transfected with the miR-370-3p mimic. In summary, these results show that Kitlg may be a direct target of miR-370-3p.

circRNA_1809, as a sponge of miR-370-3p, regulates the expression of Kitlg. (A) The binding site of miR-370-3p in Kitlg. (B) The expression of Kitlg mRNA during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs was assessed via fluorescence quantitative PCR. (C,D) Western blotting was used to analyse the protein expression of Kitlg on the 14th day of the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. (E) Fluorescence quantitative PCR was used to assess the effects of knocking down/increasing miR-370-3p on Kitlg mRNA expression. (F,G) Effects of knocking down or increasing miR-370-3p on the protein expression of Kitlg were analysed via Western blotting. (H) The effect of cotransfection of si-circRNA_1809 and plasmids for the knockdown/overexpression of miR-370-3p on the expression of Kitlg mRNA was assessed by fluorescence quantitative PCR. (I,J) The effects of cotransfection of si-circRNA_1809 and plasmids for the knockdown/overexpression of miR-370-3p on the protein expression of Kitlg were analysed via Western blotting. q-PCR data were normalized to GAPDH expression, and Western blot data were quantified via ImageJ and normalized to β-tubulin expression. The full-length blots are presented in the Supplementary Figures. All the samples were derived from the same experiment, and the gels/blots were processed in parallel. The statistical results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To verify whether Kitlg acts as a downstream target of circRNA_1809/miR-370-3p, we transfected rBMMSCs with the miR-370-3p mimic, the miR-370-3p inhibitor and si-circRNA_1809. Fluorescence quantitative PCR (Fig. 5H) and Western blotting (Fig. 5I, J) were used to assess the expression of Kitlg. The results showed that the mRNA and protein levels of Kitlg in rBMMSCs cotransfected with si-circRNA_1809 and the miR-370-3p mimic were significantly lower than those in rBMMSCs cotransfected with si-circRNA_1809 alone. In the rBMMSCs cotransfected with si-circRNA_1809 and the miR-370-3p inhibitor, the expression level of Kitlg was relatively increased. These results suggest that circRNA_1809 acts upstream of miR-370-3p and inhibits the targeting effect of miR-370-3p on Kitlg.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that circRNAs are involved in a variety of biological activities, including those associated with tumorigenesis and certain diseases18,19. However, their role in cell osteoblastic differentiation remains unclear. The purpose of this study was to investigate the regulatory effects of circRNAs on the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs at the cellular and molecular levels. In previous studies, high-throughput sequencing and fluorescent quantitative PCR revealed that circRNA_1809 was significantly upregulated during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs17. This led us to hypothesize that it is involved in promoting osteogenic differentiation and to explore it further with RNA interference techniques20.

In this study, we determined that silencing circRNA_1809 inhibited the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs, that there was a targeting relationship between circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p, and that their expression was negatively correlated. These findings are consistent with the classical regulatory mechanism of circRNAs as miRNA “molecular sponges”21,22,23. miR-370-3p was shown to play an inhibitory role in the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs, and circRNA_1809 adsorbed miR-370-3p, thereby removing its inhibitory effect on downstream target genes. This mode of regulation has also been reported in other cell differentiation and disease-related studies. In cancer research, some circRNAs can affect the biological behaviours of tumour cells, such as proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis, by adsorbing specific miRNAs24,25. Our study further expands the application of this mechanism in bone tissue biology and provides a new perspective for understanding the molecular regulatory network involved in the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs.

In addition, this study revealed that Kitlg may be a direct gene target of miR-370-3p and that circRNA_1809 affected the expression of Kitlg by regulating miR-370-3p. Kitlg, a ligand of c-Kit, is also known as stem cell factor (SCF)26. Previous studies have shown that Kitlg plays an important role in the osteogenic differentiation and haematopoietic regulation of mesenchymal stem cells and that changes in its expression level directly affect the osteogenic ability of cells27. These findings are consistent with the results of the present study, which revealed that Kitlg expression increased during the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs. Previously, through GO and KEGG enrichment analyses, we reported that the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway is closely related to circRNAs and mRNAs that are differentially expressed during rBMMSC osteogenesis17. Previous studies have shown that Kitlg can promote cell survival and proliferation by activating the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway and can also participate in the process of cell differentiation28,29. Patocyte growth factor (HGF) and stem cell factor (SCF) maintain the stemness of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBMSCs) during long-term expansion by preserving mitochondrial function via the PI3K/AKT, ERK1/2, and STAT3 signalling pathways28. Therefore, in this study, Kitlg may have affected the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs by activating the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, which is consistent with the conclusions of other studies that this signalling pathway plays a key role in cell proliferation, differentiation and antiapoptotic effects30,31. For example, in the process of bone formation induced by BMP-2, the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway is activated to promote new bone formation32. In this study, the indirect regulatory effect of circRNA_1809 on Kitlg provides a new regulatory pathway for osteogenic differentiation. We hypothesize that the circRNA_1809/miR-370-3p/Kitlg axis may promote the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs by activating the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway.

Although this study has revealed certain findings, it has several limitations. First, we verified the interaction between circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p and the regulatory role of both in the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs only at the cellular level. Although circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p have regulatory effects on Kitlg expression, our understanding of the interaction between this regulatory axis and other signalling pathways is limited. The intracellular signal transduction network is a complex system in which each signalling pathway influences and regulates each other. The effect of circRNA_1809 on cell osteoblastic differentiation has not been further verified in animal models. Future studies can establish relevant animal models to explore the role of this regulatory axis in bone tissue repair and regeneration in vivo and further study the crosstalk between the circRNA_1809/miR-370-3p/Kitlg axis and other signalling pathways. These studies will contribute to a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanism of the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs to evaluate their clinical application potential more comprehensively.

Conclusion

In summary, the results of this study further elucidate the regulatory mechanism of circRNAs in the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs and confirmed that both circRNA_1809 and miR-370-3p have regulatory effects on the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs and that there is an interactive relationship between the two. Silencing circRNA_1809 inhibited the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs through competitive binding with miR-370-3p. Kitlg was found to be the downstream target of circRNA_1809 that regulates miR-370-3p and may affect the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs by activating PI3K/Akt pathway. However, the specific molecular details of the regulatory effects of the circRNA_1809/miR-370-3p/Kitlg axis on the osteogenic differentiation of rBMMSCs and the interactions between this regulatory axis and other signalling pathways still need to be further studied. In the future, our research will further explore these aspects and provide a more solid theoretical basis for the application of circRNAs in bone tissue engineering and bone defect repair.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- BMP-2:

-

Bone morphogenetic protein-2

- ceRNA :

-

Competing endogenous RNA

- circRNA :

-

Circular RNA

- BMMSCs:

-

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- hBMMSCs:

-

Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- rBMMSCs:

-

Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

- mRNA :

-

Messenger RNA

- si-circRNA :

-

Small interfering circular RNA

- RLU:

-

Relative light unit

- RUNX2:

-

RUNt-associated transcription factor 2

- SCF:

-

Stem cell factor

References

Sakkas, A., Wilde, F., Heufelder, M., Winter, K. & Schramm, A. Autogenous bone grafts in oral implantology-is it still a “gold standard”? A consecutive review of 279 patients with 456 clinical procedures. Int. J. Implant Dent. 3(1), 23 (2017).

Chiapasco, M. & Casentini, P. Horizontal bone-augmentation procedures in implant dentistry: prosthetically guided regeneration. Periodontol 2000 77(1), 213–240 (2018).

Salhotra, A., Shah, H. N., Levi, B. & Longaker, M. T. Mechanisms of bone development and repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21(11), 696–711 (2020).

Chen, D. et al. Bidirectional regulation of osteogenic differentiation by the FOXO subfamily of Forkhead transcription factors in mammalian MSCs. Cell Prolif. 52(2), e12540 (2019).

Kitao, T. et al. A novel oral anti-osteoporosis drug with osteogenesis-promoting effects via osteoblast differentiation. Yakugaku Zasshi 139(1), 19–25 (2019).

Pang, X., Zhong, Z., Jiang, F., Yang, J. & Nie, H. Juglans regia L. extract promotes osteogenesis of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through BMP2/Smad/Runx2 and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 17(1), 88 (2022).

Hollander, J. M. & Zeng, L. The emerging role of glucose metabolism in cartilage development. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 17(2), 59–69 (2019).

Cai, H., Zou, J., Wang, W. & Yang, A. BMP2 induces hMSC osteogenesis and matrix remodeling. Mol. Med. Rep. 23(2), 125 (2021).

Xu, J., Li, Z., Hou, Y. & Fang, W. Potential mechanisms underlying the Runx2 induced osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Am. J. Transl. Res. 7(12), 2527–2535 (2015).

Agrawal, N. et al. RNA interference: biology, mechanism, and applications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67(4), 657–685 (2003).

Zhu, K. Y. & Palli, S. R. Mechanisms, applications, and challenges of insect RNA interference. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 65, 293–311 (2020).

Aurilia, C. et al. The involvement of long non-coding RNAs in bone. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(8), 3909 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. long non-coding RNA BNIP3 inhibited the proliferation of bovine intramuscular preadipocytes via cell cycle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(4), 4234 (2023).

Slack, F. J. & Chinnaiyan, A. M. The role of non-coding RNAs in oncology. Cell 179(5), 1033–1055 (2019).

Kumari, A., Sedehizadeh, S., Brook, J. D., Kozlowski, P. & Wojciechowska, M. Differential fates of introns in gene expression due to global alternative splicing. Hum. Genet. 141(1), 31–47 (2022).

Kristensen, L. S. et al. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20(11), 675–691 (2019).

Yao, Y. et al. Differential circRNA and mRNA expression profiling during osteogenic differentiation in rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Med. Sci. Monit. 28, e936761 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Roles and mechanisms of exosomal non-coding RNAs in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6(1), 383 (2021).

Seroussi, U. et al. Mechanisms of epigenetic regulation by C. elegans nuclear RNA interference pathways. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 127, 142–154 (2022).

Gao, M., Zhang, Z., Sun, J., Li, B. & Li, Y. The roles of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks in the development and treatment of osteoporosis. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 945310 (2022).

Li, J., Sun, D., Pu, W., Wang, J. & Peng, Y. Circular RNAs in cancer: Biogenesis, function, and clinical significance. Trends Cancer 6(4), 319–336 (2020).

Misir, S., Wu, N. & Yang, B. B. Specific expression and functions of circular RNAs. Cell Death Differ. 29(3), 481–491 (2022).

Ashfaq, M. A. et al. Post-transcriptional gene silencing: Basic concepts and applications. J. Biosci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12038-020-00098-3 (2020).

Zhang, M. et al. circRNA-miRNA-mRNA in breast cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 523, 120–130 (2021).

Liang, Z. Z., Guo, C., Zou, M. M., Meng, P. & Zhang, T. T. circRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory network in human lung cancer: an update. Cancer Cell Int. 20, 173 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. Stem cell factor (SCF) protects osteoblasts from oxidative stress through activating c-Kit-Akt signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 455(3–4), 256–261 (2014).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Lnk-dependent axis of SCF-cKit signal for osteogenesis in bone fracture healing. J. Exp. Med. 207(10), 2207–2223 (2010).

Cao, Z., Xie, Y., Yu, L., Li, Y. & Wang, Y. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and stem cell factor (SCF) maintained the stemness of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBMSCs) during long-term expansion by preserving mitochondrial function via the PI3K/AKT, ERK1/2, and STAT3 signaling pathways. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 11(1), 329 (2020).

Liao, F. et al. ECFC-derived exosomal THBS1 mediates angiogenesis and osteogenesis in distraction osteogenesis via the PI3K/AKT/ERK pathway. J. Orthop. Transl. 37, 12–22 (2022).

Hoxhaj, G. & Manning, B. D. The PI3K-AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20(2), 74–88 (2020).

Wu, B. et al. A novel role for RILP in regulating osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 103(5), 100067 (2023).

Dong, J., Xu, X., Zhang, Q., Yuan, Z. & Tan, B. Critical implication of the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway during BMP2-induced heterotopic ossification. Mol. Med. Rep. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2021.11893 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Science Foundation of the Nature Foundation of Xinjiang Autonomous Region (project name: circRNA_1809/miR-370-3p/Kitlg Regulation mechanism of osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, project number: 2023D01C230).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Mengjie Xu, Refeina Tuerxun, and Mireyeti Shahatibieke. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yidan Xu. Lei Zhang and Ningning Liu commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Medical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University (permit number: K202409-04).The animal studies were conducted according to the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments).All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.The authors declare that they have not use AI-generated work in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Xu, Y., Liu, N. et al. CircRNA_1809 promotes the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells through miR-370-3p. Sci Rep 15, 19950 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03711-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03711-3