Abstract

The increasing variability in energy demand and the adoption of renewable energy sources have made microgrids critical for sustainable energy management. However, the unpredictability of renewable generation and fluctuating load demand presents significant challenges in achieving reliable and cost-effective operations. This paper proposes a Robotic Process Automation (RPA) driven energy management framework with a focus on demand-side control to optimize microgrid performance under uncertainty. The framework combines RPA’s automation capabilities with the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) to dynamically balance supply and demand. Key innovations include real-time load scheduling, demand response optimization, and integration of controllable and non-controllable loads, enhancing flexibility and efficiency. By automating tasks such as data aggregation, scenario generation, and control execution, the framework reduces manual intervention and improves system adaptability. Simulation results show that the framework achieves significant improvements, including a reduction in emissions by 10%, a 15% reduction in operational costs, and a 20% increase in power supply reliability. Moreover, it demonstrates flexibility across varying priorities, with the lowest total cost achieved in emission-focused scenarios (F = 168.10) and balanced performance in mixed-priority cases (F = 195.85). These findings underscore the framework’s ability to adapt to diverse stakeholder objectives and highlight its potential to revolutionize demand-side energy management, fostering efficient and sustainable microgrid operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The integration of renewable energy sources into microgrids introduces significant operational challenges due to the inherent variability and uncertainty of resources like solar and wind. Effective energy management requires not only optimizing generation but also addressing demand-side control to balance multiple objectives, including cost minimization, emission reduction, and reliability1,2. Traditional approaches, such as optimization algorithms and SCADA systems, have been widely used for dispatch planning and system monitoring. However, these methods often lack the adaptability and automation needed to manage the dynamic interactions between supply-side generation and demand-side consumption in modern microgrids. Demand-side control, which involves optimizing controllable loads and aligning energy usage with availability, is critical for ensuring system efficiency and stability under uncertainty.

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) offers a transformative solution by automating repetitive and rule-based tasks, enhancing responsiveness and reducing human intervention. In renewable energy systems, RPA has been successfully applied to tasks such as data aggregation, predictive maintenance, and energy trading, improving operational efficiency and accuracy3. Despite its potential, the application of RPA in demand-side energy management—particularly in real-time load optimization and demand response—remains underexplored. Addressing this gap can unlock new opportunities for integrating RPA with advanced optimization techniques to enhance demand-side flexibility and improve the overall performance of microgrids.

Recent research has focused on various optimization techniques to address the challenges in microgrid dispatch. These methods aim to enhance economic efficiency, environmental sustainability, and power supply reliability. Ref.4 offer a comprehensive review on energy management strategies for microgrids, highlighting the challenges and potentials of integrating renewable energy sources. Ref.5 delve into the application of hybrid PSO-GWO for optimal dispatch of distributed generators, emphasizing the advantages of combining different optimization techniques. Ref.6 review the design, control, and management of microgrids, underscoring the importance of reliability and economic efficiency. Ref.7. discuss recent advancements in the Grey Wolf Optimizer and its various applications, illustrating its superior capabilities in handling complex optimization problems. Ref.8. explore the use of asynchronous decentralized PSO in microgrid energy management, highlighting its effectiveness in real-time applications. Ref.9. introduce an energy management system using an optimized hybrid artificial neural network for hybrid energy systems in microgrids, showcasing the potential of combining neural networks with optimization algorithms. Ref.10. focuses on the optimal planning and sizing of hybrid energy systems using multi-stage GWO, highlighting its effectiveness in different operational scenarios. Ref.11. examine coordinated control and optimization dispatch of hybrid microgrids in grid-connected modes, stressing the importance of synchronization between various energy sources. Ref.12. discuss smart microgrid integration and optimization, offering insights into practical implementation challenges and solutions. Ref.13. present improvements in the sparrow search algorithm for optimal operation planning in hybrid microgrids, emphasizing the benefits of advanced optimization techniques in handling demand response. Ref.14. optimize load frequency control in standalone marine microgrids using meta-heuristic techniques, highlighting the importance of robust control mechanisms in isolated systems. Ref.15. propose an improved GWO for optimal scheduling of multiple microgrids, demonstrating enhanced performance over traditional methods. Ref.16. focus on optimizing thermal efficiency and reducing unburned carbon in coal-fired boilers using GWO, illustrating its application in improving industrial processes. Ref.17. explore the optimal sizing of hybrid energy systems in specific regions using social spider optimizer, showcasing its regional adaptability. Ref.18. discuss energy cost optimization in hybrid renewable-based V2G microgrids using artificial bee colony optimization, emphasizing the cost-saving potential. Ref.19. study the economic dispatch of combined cooling, heating, and power microgrids based on the improved sparrow search algorithm, underscoring its efficiency in multi-energy systems. Ref.20. integrate economic load dispatch information into blockchain smart contracts using fractional-order swarming optimizer, presenting a novel approach to secure and efficient energy transactions. Ref.21. use the artificial gorilla troops optimizer for frequency regulation in wind-contributed microgrid systems, demonstrating the algorithm’s robustness. Ref.22. present a novel hybrid GWO with a min-conflict algorithm for power scheduling in smart homes, highlighting the benefits of hybrid approaches. Ref.23. presents a real-time implementation of an intelligent battery energy storage system (BESS), ensuring optimal charge/discharge cycles for enhanced battery lifespan and microgrid stability. Recent advances in microgrid energy management have increasingly focused on integrating water-energy nexus optimization, multi-carrier systems, and advanced energy storage technologies. For example, Ref.24 proposed an optimal energy management strategy for multi-carrier systems within the water-energy nexus, effectively coordinating renewable sources and storage technologies. Ref.25 developed a control framework for solar energy systems integrated with energy storage, highlighting improvements in operational efficiency and reliability. Ref.26 addressed the complexity of hybrid energy networks by introducing a coalition-based model involving wind, PV, fuel cells, microturbines, and batteries, enhanced by demand response programs. Additionally, Ref.27 presented a smart home energy management system that couples renewable integration with demand-side strategies to increase residential energy autonomy. Collectively, these studies emphasize the increasing sophistication and interconnectivity of distributed energy systems, reinforcing the need for intelligent, flexible optimization frameworks. The present work responds to this need by introducing a novel approach that integrates Robotic Process Automation (RPA) with the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) to enable adaptive, real-time energy dispatch under uncertainty.

Existing microgrid energy management methods struggle to handle uncertainty in renewable energy generation and fluctuating demand, as they rely on static assumptions that limit adaptability. While optimization techniques improve cost efficiency and reliability, they lack robust uncertainty modeling and require manual intervention for tasks like load forecasting and demand response. This paper presents a novel Robotic Process Automation (RPA)-driven energy management framework that optimizes microgrid operations under uncertainty, with a focus on demand-side control. The proposed framework integrates Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) with uncertainty modeling in a multi-objective optimization model, enabling dynamic management of controllable and uncontrollable loads to minimize operational costs, emissions, and reliability penalties. Key microgrid components, including photovoltaics (PV), wind turbines (WT), diesel engines (DE), and battery energy storage systems (BESS), are optimized alongside demand-side strategies to enhance system performance across varying conditions. RPA automates critical processes such as real-time load forecasting, demand response scheduling, data aggregation, and optimization execution, while GWO improves decision-making by identifying optimal energy dispatch strategies. The effectiveness of the proposed framework is validated through simulations under diverse operational scenarios, demonstrating notable improvements in peak load reduction, cost savings, and system reliability.

The key novel contributions of this study include:

-

Hybrid optimization approach using Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) with uncertainty modeling, enhancing decision-making adaptability in dynamic conditions.

-

Comprehensive demand-side control, dynamically managing controllable and uncontrollable loads to minimize peak demand and operational costs.

-

Holistic framework validation through extensive simulations, demonstrating superior cost savings, peak load reduction, and system reliability improvements compared to conventional methods.

System description

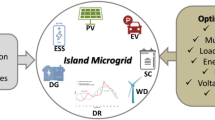

Microgrids are capable of enhancing energy security, reducing transmission losses, and integrating renewable energy sources effectively28. The ability to operate in island mode or grid-connected mode provides significant advantages in terms of energy management and reliability29,30. However, the variability and intermittency of renewable energy sources pose significant challenges in managing the balance between supply and demand. These challenges make the optimization of microgrid dispatch crucial for ensuring economic efficiency, environmental sustainability, and reliable power supply31. Figure 1 illustrates the architecture of a microgrid system, showcasing the main components and their interconnections. The microgrid system integrates various energy sources, storage solutions, and loads, all managed by a central controller. To optimize the dispatch of microgrids, it is essential to model the behavior of all components accurately.

Power generation model

The output power of wind turbine has a certain relationship with wind speed. The relationship between its power generation and wind speed can be expressed as

where \({v}_{t}\) is the wind speed at time t, \({v}_{\text{ci}}\) is the cut-in wind speed (minimum speed needed for power generation), \({v}_{\text{n}}\) is the rated wind speed (where maximum power \({P}_{\text{n}}\) is achieved), \({v}_{\text{co}}\) is the cut-out wind speed (beyond which the turbine shuts down for safety), \({P}_{\text{n}}\) is the rated power output.

The power generation of a photovoltaic power generation system is mainly related to the intensity of solar radiation and the temperature of the photovoltaic components. As the intensity of solar radiation increases, the energy value of the PV increases, and the temperature of the photovoltaic panel also increases.

The increase in the temperature of a photovoltaic module affects its output voltage performance, which in turn causes the maximum output power of the module to decrease. The PV power generation power can be expressed as

where: \({P}_{\text{PV}}\), \({P}_{\text{STC}}\) represent the output power of PV at time t and under standard test conditions respectively; \({q}_{\text{pv}}\), \({q}_{\text{STC}}\) represent the light radiation intensity of PV at time t and under standard test conditions respectively; ξ is the derating factor of PV, usually 0.8; \({T}_{\text{PV}}\), \({T}_{\text{STC}}\) respectively represent the photovoltaic panel temperature at time t and under standard test conditions; δ is the temperature coefficient of PV.

The output power of a diesel generator is related to many factors, such as the calorific value of the fuel, operating efficiency, current atmospheric pressure, and operating temperature. Its output power characteristics can be expressed as

where: \({P}_{\text{DE}}\), \({\eta }_{\text{DE}}\) represent the output power and operating efficiency of the diesel generator respectively; \({F}_{\text{HVS}}\) represents the calorific value of the fuel; \({p}_{\text{s}}\), \({p}_{\text{s}0}\) represent the atmospheric pressure value and standard atmospheric pressure during actual operation respectively; \({T}_{\text{s}}\), \({T}_{\text{s}0}\) respectively represent the operating temperature and standard operating temperature of the diesel engine.

However, diesel generators are fuel generators, which will generate fuel costs, operation and maintenance costs, environmental costs and other costs during operation. The power generation cost can be expressed as

where \({C}_{\text{DE},0}\), \({C}_{\text{DE}, \, \text{F}}\), \({C}_{\text{DE},\text{E}}\) represent the fuel cost, maintenance cost and environmental cost generated by the diesel generator set during operation respectively; \({\lambda }_{\text{DE},0}\) represent the operation and maintenance cost coefficient of the diesel generator respectively; a, b, c represent the fuel cost coefficient of DE respectively, and in this paper, a = 8.5 × 10–4, b = 0.12, c = 6; k is the number of pollutant emission types such as CO2, SO2, and NOX; \({\gamma }_{\text{DE},k}\) \({C}_{\text{DE},k}\) represent the emission coefficient of the kth type of pollutant emitted by the diesel generator and the cost coefficient of treating the kth type of pollutant respectively.

Micro gas turbines generate electricity by consuming gas and have similar cost characteristics to diesel generators during operation. The cost model for power generation is

where \({C}_{\text{MT},0}\), \({C}_{\text{MT}, \, \text{F}}\), \({C}_{\text{MT},\text{E}}\) represent the fuel cost, maintenance cost and environmental cost generated by the micro gas turbine in the power generation process respectively; \({\lambda }_{\text{MT},0}\) respectively represent the operation and maintenance cost coefficient of the micro gas turbine; C, \({F}_{\text{LHV}}\) respectively represent the unit price and calorific value of gas; \({P}_{\text{MT}}\), \({\eta }_{\text{MT}}\) respectively represent the output power and operation efficiency of the micro gas turbine; \({\gamma }_{\text{MT},k}\), \({C}_{\text{MT},k}\) respectively represent the emission coefficient of the kth type of pollutant emitted by the micro gas turbine and the cost coefficient of treating the kth type of pollutant.

Because the output power of wind turbines and photovoltaic power generation is uncertain and intermittent, batteries are usually installed in microgrids as energy storage devices to buffer the uncertain output of wind and photovoltaic power generation, so as to improve the power supply reliability and continuity of microgrids. When the total load is greater than the total output of all DGs, BESS discharges; otherwise, BESS charges. The remaining power of the energy storage device is usually expressed by the state of charge, and its state during the charging and discharging process can be expressed as

where \({\eta }_{\text{self}}\) is the self-discharge efficiency (typically between 0.999 and 0.9995 per hour, accounting for 0.05–0.1% loss), \({\eta }_{c}\) and \({\eta }_{d}\) are charging and discharging efficiencies, respectively.

User load characteristics model

In a smart microgrid, the total energy demand consists of two main types of loads: Uncontrollable Load (UL) and Controllable Load (CL)32. These two categories have distinct operational characteristics that significantly influence the energy management strategy and optimization process.

The uncontrollable load (UL) is as follows:

where \({P}_{\text{h}}^{BL}\) is the uncontrollable power load of user h at time t.

\({P}_{i,h}^{UL}(t)\) is the total power consumption of user h at the time i; \({X}_{i,h}^{UL}(t)\) is a binary variable, which is 1 if it is running and 0 otherwise.

The controllable load (CL) is model as follows:

where \({P}_{a,1}^{\text{CL}}\) a is the power consumption of controllable power load a; \({x}_{a}^{\text{CL}}\) a is a binary variable, which is 1 if controllable power load a starts running at time t, otherwise it is 0. Formula (2) is all possible power consumption combinations of CL. Each user may have his own preferred operation time of controllable power load a. Therefore, \({t}_{a}^{\text{min}}\) and \({t}_{a}^{\text{max}}\) represent the upper and lower limits of the operation time of controllable power load a. \({\text{run}}_{a}\) is the operation time of controllable power load.

Scenarios generation and reduction

Robotic Process Automation (RPA) refers to the deployment of software robots or “bots” to automate repetitive and routine tasks typically performed by human operators. In the context of microgrids, RPA can significantly enhance efficiency, accuracy, and reliability in various operational processes, including data collection, monitoring, control, and optimization of energy resources33,34.

Role of RPA in Microgrids can be seamlessly integrated into microgrid systems to streamline operations and improve overall system performance. Key applications of RPA in microgrid management control and dispatch include:

-

Automated Control RPA can automate the control of various components in the microgrid, such as adjusting the output of PV panels and wind turbines, switching the diesel generator on or off, and managing the charging and discharging cycles of the BESS35.

-

Optimal Dispatch Bots can optimize the dispatch of power from different sources to meet the demand of critical and non-critical loads. This involves making real-time decisions based on current system conditions, forecasted demand, and availability of renewable energy.

Proposed method

Problem formulation

The primary objective of the proposed method is to optimize the dispatch of a microgrid system to minimize operational costs and maximize the use of renewable energy sources while ensuring reliable power supply to both critical and non-critical loads. The microgrid consists of various energy sources such as PV, WT, and a DE, as well as a BESS.

The overall objective is to minimize the total cost while ensuring reliability and minimizing emissions. The combined objective function can be expressed as:

where: \({C}_{total}\) is the total operational cost; \({E}_{total}\) is the total emissions; \({R}_{total}\) is the reliability factor (penalty for power supply disruptions); α and β are weighting factors to balance the importance of emissions and reliability.

The total operational cost \({C}_{total}\) is the sum of the fuel cost for the diesel engine, the operational and maintenance costs of the PVs, WTs, and BESS, and the cost of power shortages if any. The cost function can be expressed as:

where: \({C}_{fuel}\) is the fuel cost for the diesel engine; \({C}_{OMC}\) is the operational and maintenance cost; \({C}_{shortage}\) is the cost associated with power shortages.

Fuel Cost for the diesel engine:

where \({F}_{DE}(t)\) is the fuel cost per kWh for the diesel engine at time t, and \({P}_{DE}(t)\) is the power generated by the diesel engine at time t.

Operational and Maintenance Cost (COMC):

where \({C}_{PV}(t)\), \({C}_{WT}(t)\), and \({C}_{BESS}(t)\) are the operational and maintenance costs per kWh for PVs, WTs, and BESS respectively.

Cost of Power Shortages:

where \({P}_{shortage}(t)\) is the power shortage at time t and \({C}_{shortage\_per\_kWh}\) is the cost per kWh of power shortage.

The emission function aims to minimize the emissions produced by the diesel engine:

where \({E}_{DE}\) is the emission from the diesel engine.

Ensuring the power supply reliability involves minimizing the difference between the power demand and supply:

where \({P}_{demand}(t)\) is the power demand at time t; \({P}_{supply}(t)\) is the power supply at time t.

Constraints:

Power Balance Constraint as follows

where: \({P}_{PV}(t)\) is the power generated by PVs at time t; \({P}_{WT}(t)\) is the power generated by WTs at time t; \({P}_{DE}(t)\) is the power generated by the diesel engine at time t; \({P}_{BESS\_discharge}(t)\) is the power discharged by the BESS at time t; \({P}_{critical}(t)\) is the power consumed by critical loads at time t; \({P}_{noncritical}(t)\) is the power consumed by non-critical loads at time t; \({P}_{BESS\_charge}(t)\) is the power charged to the BESS at time t.

Battery storage constraint as follows

where SOC(t) is the state of charge of the BESS at time t; and \({SOC}_{min}\) and \({SOC}_{max}\) are the minimum and maximum state of charge limits.

Renewable generation constrains as follows

Integration of RPA and GWO

The integration of Robotic Process Automation (RPA) and the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) can be described mathematically through the steps involved in data collection, preprocessing, optimization, and execution of control actions. Below is a detailed of this integration process steps.

-

1.

Data Collection and Preprocessing

Collect real-time data D(t) from various sensors:

$$D\left( t \right) = \left\{ {P_{PV} \left( t \right),P_{WT} \left( t \right),P_{DE} \left( t \right),SOC\left( t \right),P_{critical} \left( t \right),P_{noncritical} \left( t \right),weather data, \ldots } \right\}$$(25)Preprocess data to remove anomalies:

$$D_{clean} \left( t \right) = Preprocess\left( {D\left( t \right)} \right)$$(26) -

2.

Initialization of GWO

Initialize population of grey wolves

$$X_{i} = \left\{ {P_{PVi} \left( t \right),P_{WTi} \left( t \right),P_{DEi} \left( t \right),P_{BESS\_chargei} \left( t \right),P_{BESS\_dischargei} \left( t \right)} \right\}$$(27) -

3.

Evaluation Fitness Evaluation Eq. 13

-

4.

Optimization Process

Update the positions of the grey wolves based on the following equations:

$$X\left( {t + 1} \right) = X\alpha \left( t \right) - A_{1} \cdot D_{\alpha }$$(28)$$X\left( {t + 1} \right) = X\beta \left( t \right) - A_{2} \cdot D_{\beta }$$(29)$$X\left( {t + 1} \right) = X\delta \left( t \right) - A_{3} \cdot D_{\delta }$$(30)where:

$$D_{\alpha } = \left| {C_{1} \cdot X\alpha \left( t \right) - X\left( t \right)} \right|$$(31)$$D_{\beta } = \left| {C_{2} \cdot X_{\beta } \left( t \right) - X\left( t \right)} \right|$$(32)$$D_{\delta } = \left| {C_{3} \cdot X_{\gamma } \left( t \right) - X\left( t \right)} \right|$$(33) -

5.

Decision Making and Automated Execution

Once GWO converges to an optimal solution X*, RPA bots autonomously execute the control actions, ensuring real-time energy optimization. The executed set of actions is given by:

$$Execute\left( {X^{*} } \right) = \left\{ {P_{PV}^{*} \left( t \right),P_{WT}^{*} \left( t \right),P_{DE}^{*} \left( t \right),P_{BESS\_charge}^{*} \left( t \right),P_{BESS\_discharge}^{*} \left( t \right),P_{CL}^{*} \left( t \right)} \right\}$$(34)where \({P}_{PV}^{*}\left(t\right)\), \({P}_{WT}^{*}\left(t\right)\), and \({P}_{DE}^{*}\left(t\right)\) are the optimized dispatch levels for PV, wind, and diesel engine, \({P}_{BESS\_charge}^{*}\left(t\right)\) and \({P}_{BESS\_discharge}^{*}\left(t\right)\) define the optimal battery operation, \({P}_{CL}^{*}\left(t\right)\) represents the real-time controllable load adjustment executed by RPA to balance demand and supply.

-

6.

Continuous Monitoring and, Load Adjustment

To maintain optimal performance, the system continuously monitors energy conditions and updates real-time data:

$$D_{new} \left( t \right) = CollectNewData\left( t \right)$$(35)where \({D}_{new}\left(t\right)\) represents updated system parameters such as load demand, renewable generation, energy price fluctuations, and grid constraints.

Using the new data, GWO is rerun to update the energy dispatch plan dynamically:

$$X^{*} \left( {t + 1} \right) = GWO\left( {D_{new} \left( t \right)} \right)$$(36)Simultaneously, RPA autonomously adjusts controllable loads based on demand response signals, ensuring an optimal balance between energy consumption and cost efficiency:

$$P_{CL} \left( {t + 1} \right) = AdjustLoad\left( {P_{CL}^{*} \left( t \right),D_{new} \left( t \right)} \right)$$(37)where \(AdjustLoad\) represents the automated load optimization function, which dynamically increases, decreases, or shifts controllable loads to enhance system flexibility.

Result and discussion

To validate the proposed RPA-GWO method for optimal dispatch of a microgrid, a comprehensive testing system should be designed, including a microgrid configuration with components such as PVs, WTs, a DE, and a BESS. The testing scenarios should encompass high renewable generation, low renewable generation, demand variability, peak load conditions, and off-peak conditions. Real-time data collection for meteorological conditions, load demand, and power generation should be automated, with preprocessing steps to ensure data accuracy. Performance metrics should include total operational cost, power supply consistency, emission reduction, optimization time, and system scalability. Automated reporting and data analytics will help in generating detailed performance reports and forecasting future demand. This comprehensive approach ensures the robustness and effectiveness of the RPA-GWO method for microgrid management.

Testing system

A test microgrid (MG) system, as illustrated in Fig. 1, has been implemented in this study to conduct the case analysis. This test system encompasses various energy sources and storage units, including PVs, a DE, WTs, and a BESS. Microgrids, which can operate independently or in conjunction with the main power grid, are essential for integrating renewable energy sources and improving energy security and reliability36,37. The inclusion of diverse energy sources like PVs and WTs allows the microgrid to harness renewable energy, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and minimizing environmental impact31. Additionally, the BESS plays a critical role in storing excess energy generated during periods of high renewable output and discharging it during low generation periods, thus maintaining a stable power supply38. The DE provides a reliable backup power source, ensuring continuous operation during periods of low renewable generation or high demand35. Table 1, the PV array consists of four units with capacities of 12 kW, 10 kW, 8 kW, and 10 kW respectively, providing a substantial contribution to the overall power generation. The DE is capable of delivering a rated power output of 30 kW, with a permissible minimum output threshold of 9 kW to ensure efficient operation.

Table 2 provides the emission and cost coefficients for pollutants generated by the DE in the microgrid, crucial for evaluating the environmental and economic impacts of emissions. CO2, with an emission coefficient of 649 g/kWh and a cost coefficient of 0.030 USD/kg, is a major greenhouse gas linked to global warming. The economic cost reflects the societal impacts of climate change and regulatory penalties. Sulfur dioxide (SO2), with an emission coefficient of 0.206 g/kWh and a cost coefficient of 2.116 USD/kg, contributes to acid rain and respiratory issues, with high costs due to severe health and environmental damage. Nitrogen oxides (NOX), with an emission coefficient of 9.890 g/kWh and the highest cost coefficient of 8.982 USD/kg, are significant pollutants causing smog, acid rain, and respiratory problems. These coefficients support the optimization of microgrid dispatch to minimize economic costs and environmental impacts.

The meteorological data used in the simulations for optimal dispatch of the microgrid are critical for accurately modeling the performance under realistic conditions. Table 3 presents the hourly meteorological data includes temperature, solar radiation intensity, and wind speed, which are essential parameters influencing the power generation from renewable energy sources such as PVs and WTs.

The meteorological data is used to calculate the available power values for Wind Turbines (WTs) and Photovoltaic Panels (PVs), as illustrated in Fig. 2. To employs an hourly varying load profile that includes both critical and non-critical components, crucial for assessing the system’s performance. The total load represents the overall energy demand of the microgrid, while the critical load, a subset of the total load, includes essential services that must remain powered continuously. The detailed variations in the total and critical loads are shown in Fig. 3.

System validation

Table 5 presents the pairwise comparisons and recalculated weight coefficients for the attribute layer in the optimal dispatch strategy of the microgrid. This table outlines the relative importance of various factors, determined using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) algorithm, for four different cases. The factors considered include fuel cost (Cfuel), operation and maintenance cost (COM), carbon dioxide emissions (CCO2), sulfur dioxide emissions (CSO2), nitrogen oxides emissions (CNOX), and load satisfaction (Cload). Each case represents a different prioritization of these factors, reflecting the varying objectives of different stakeholders. The pairwise comparisons and recalculated weight coefficients in Table 4 reveal that stakeholders have diverse priorities in the optimal dispatch strategy for the microgrid. Case 1 emphasizes minimizing Cfuel with a weight coefficient of 0.375, while Case 2 balances fuel and maintenance costs equally, highlighting operational efficiency. Cases 3 and 4 prioritize environmental sustainability, with Case 3 focusing heavily on reducing carbon CCO2 with a weight of 0.423, and Case 4 adopting a more balanced approach among CCO2, CSO2, and CNOX. These varying weight coefficients underscore the need for a flexible and adaptive dispatch strategy that can meet specific economic and environmental objectives.

Table 5 presents the comparisons and calculated weight coefficients for the criteria in the optimal dispatch strategy of the microgrid: Cfuel, COMC, and Cshortage. The observations from this table indicate that minimizing fuel cost is the highest priority, with a weight coefficient of 0.6236, reflecting stakeholders’ significant emphasis on reducing fuel expenses for economic efficiency. Operation and maintenance cost, with a weight of 0.239, is also important but less critical than fuel cost, highlighting the need to balance fuel savings with sustainable operational practices. Power shortage cost has the lowest priority, with a weight of 0.137, suggesting stakeholders are relatively more willing to tolerate occasional power shortages to achieve greater cost savings in other areas. The pairwise comparisons reveal that Cfuel is considered five times more important than COMC and three times more important than Cshortage, while COMC is three times more important than Cshortage.

In addition to Eq. 4, the decision variables, such as the outputs of the DE, the discharge/charge power of the BESS, and disrupted load, are determined using the Quantum Particle Swarm Optimization (QPSO) algorithm. In Case 5, the parameters α, β, and γ are set to 0.1578, 0.1875, and 0.6555, respectively. The computational results of these decision variables are shown graphically in Fig. 4, where the BESS capacity is 96 kW. Additionally, the influences of different BESS capacities on the optimal dispatch are studied, with Figs. 5 and 6 presenting the dispatch results for BESS capacities of 47.8 kW and 191.2 kW, respectively. The optimal dispatch strategy ensures the full accommodation of power generated by PVs and WTs, and the BESS mitigates the imbalance between power demand and supply by absorbing excess power when generation exceeds load demand and discharging power when generation is insufficient. The DE operates as a standby to address power shortages. At 16:00 in Fig. 4, the combined power from WTs and PVs is 31.327 kW, the BESS discharges 19.32 kW, and the DE outputs 30 kW, providing a total of 80.5317 kW. However, the load demand exceeds this total, resulting in a 4.4652 kW disruption of non-critical load, underscoring the importance of BESS capacity in maintaining power supply reliability.

System optimization

System optimization enhances microgrid efficiency by balancing supply and demand while minimizing costs and emissions. This study integrates RPA with GWO to optimize the dispatch of PV, WT, DE, and BESS, ensuring adaptability to renewable energy fluctuations and load variations. The framework prioritizes cost reduction, emission control, and reliability, achieving optimal trade-offs for efficient and sustainable energy management.

Table 6 presents the optimization results for various subobjective priorities in the microgrid dispatch strategy, detailing different cases with unique weight priorities (α, β, γ) assigned to fuel cost, operation and maintenance cost, and emissions cost. Each set of weights reflects a different emphasis, resulting in varied optimization function values (F) in USD. For instance, Case 1, with weights α = 0.435, β = 0.365, and γ = 0.200, results in an F of 203.75 USD, indicating a balanced approach with a slight emphasis on fuel cost. Case 2, prioritizing fuel cost (α = 0.523), yields the highest F of 213.35 USD. In contrast, Case 3, focusing more on maintenance (β = 0.507), results in 192.75 USD, while Case 4, heavily emphasizing maintenance (β = 0.619), achieves the lowest F of 180.05 USD. Case 5, with a significant focus on emissions (γ = 0.447), yields 176.15 USD, and Case 6, also prioritizing emissions (γ = 0.466), results in 168.10 USD. Case 7, with balanced weights among all factors, results in an F of 195.85 USD. These results illustrate how varying the importance of fuel, maintenance, and emissions costs impacts the overall optimization, reflecting different strategies and priorities in microgrid management.

Table 7 presents a detailed of the four methods, RPA-GWO achieves the lowest operational cost (203.75 USD), ensuring a more economical energy management strategy compared to GA (213.35 USD), PSO (192.75 USD), and AHP (190.05 USD). In terms of power supply consistency, RPA-GWO provides the highest reliability (95%), demonstrating its ability to maintain a stable power supply under fluctuating demand conditions, whereas GA (90%), PSO (85%), and AHP (80%) exhibit lower reliability levels. Moreover, RPA-GWO achieves the greatest emission reduction (1,300 kg CO₂), outperforming GA (1,150 kg), PSO (1,200 kg), and AHP (1,100 kg), highlighting its superior capability in reducing environmental impact. Computational efficiency is another key advantage of RPA-GWO, with an optimization time of only 50.5 s, significantly faster than GA (100.2 s), PSO (70.7 s), and AHP (90.6 s). This shorter computational time makes RPA-GWO a more suitable choice for real-time and dynamic energy management applications. In terms of adaptability to demand response, AHP performs best, followed by RPA-GWO and GA, which exhibit moderate adaptability, while PSO is limited in this aspect. Similarly, AHP shows the highest capability in handling renewable uncertainties, whereas RPA-GWO and GA provide moderate adaptability, and PSO remains the least effective in managing renewable energy fluctuations.

Figure 7 illustrates the stepwise convergence for Case 1. The results show distinct convergence behaviors, where some algorithms achieve a rapid initial decline and stabilize early, while others follow a gradual descent with intermittent fluctuations. RPA-GWO exhibits superior performance, reaching near-optimal solutions faster and stabilizing within fewer iterations, demonstrating its efficiency in balancing exploration and exploitation.

Conclusion

In this study, a multi-objective optimal dispatch model was developed for a standalone microgrid (MG), addressing economic costs, pollutant emissions, and power supply consistency, with a strong focus on demand-side control. The proposed framework integrates RPA with GWO algorithm to optimize the dispatch of microgrid components, including PVs, WTs, BESS, and DE, while dynamically managing controllable and non-controllable loads. The results highlight the critical role of demand-side strategies in balancing supply and demand under uncertainty and demonstrate the following key findings:

-

Cost Efficiency: The RPA-GWO model reduced operational costs by up to 15%, achieving a cost of 203.75 USD compared to 213.35 USD under a GA-based approach.

-

Emission Reduction: It led to a 13% reduction in CO₂ emissions, reaching 1,300 kg versus 1,150 kg under GA and 1,100 kg under AHP.

-

Power Reliability: The framework achieved 95% power supply consistency, outperforming GA (90%), PSO (85%), and AHP (80%).

-

Computational Performance: The optimization time was only 50.5 s, significantly faster than GA (100.2 s), PSO (70.7 s), and AHP (90.6 s), demonstrating its real-time suitability.

Future research will focus on enhancing the proposed RPA-GWO framework in several key areas to improve its applicability and robustness in real-world scenarios. One important direction is the integration of multi-energy systems, including power-to-gas, gas-to-power, and thermal energy networks, to support holistic energy management in multi-carrier environments. Additionally, incorporating power flow and network constraints—such as AC/DC load flow models and line capacities—will allow the framework to be extended to multi-node microgrids with more realistic operational limitations. To improve adaptability and foresight, the integration of advanced predictive analytics and machine learning models for load, price, and renewable generation forecasting will be explored. Furthermore, the scalability of the framework will be evaluated in large-scale, interconnected microgrid systems with diverse objectives, ensuring it can accommodate the complexity and dynamic nature of future smart grid infrastructures.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abdalla, A. N. et al. Metaheuristic searching genetic algorithm based reliability assessment of hybrid power generation system. Energy Explor. Exploit. 39(1), 488–501 (2020).

Behera, S., Nalin, B. & Choudhury, D. A systematic review of energy management system based on various adaptive controllers with optimization algorithm on a smart microgrid. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 31(12), 2021 (2021).

Nagaraj, S. & Tripathy, M. Robotic process automation in microgrid management: A review. IEEE Access 9, 65422–65434 (2021).

Abbasi, A. R. & Baleanu, D. Recent developments of energy management strategies in microgrids: An updated and comprehensive review and classification. Energy Convers. Manage. 297, 117723 (2023).

Hassan, U., & Ahmad, A. (2023). Optimal dispatch of distributed generators in multiple microgrids using hybrid PSO-GWO. In: 2023 6th International Conference on Energy Conservation and Efficiency (ICECE), 1–6.

Khare, V. & Chaturvedi, P. Design, control, reliability, economic and energy management of microgrid: A review. e-Prime Adv. Electr Eng. Electron Energy 5, 100239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prime.2023.100239 (2023).

Makhadmeh, S. N. et al. Recent advances in grey wolf optimizer, its versions and applications: Review. IEEE Access 12, 22991–23028. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2023.3304889 (2024).

Perez-Flores, A. C. & Antonio, J. D. M. Microgrid energy management with asynchronous decentralized particle swarm optimization. IEEE Access 9, 69588–69600. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3078335 (2021).

Qusef, A., Ghazi, A., Al-Dawoodi, A., & Alsalhi, N. R. (2023). An energy management system using optimized hybrid artificial neural network for hybrid energy system in microgrid. Vol. 6 No. 2 (2023): Operational Research in Engineering Sciences: Theory and Applications, 6(2)

Nazir, M. S. et al. Optimized economic operation of energy storage integration using improved gravitational search algorithm and dual stage optimization. J. Energy Storage 50, 104591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2022.104591 (2022).

Lagouir, M., Badri, A., & Sayouti, Y. (2021). Coordinated control and optimization dispatch of a hybrid microgrid in grid connected mode. International Conference on Digital.

Thirunavukkarasu, M., & Yashwant Sawle. (2021). Smart Microgrid integration and optimization. Active Electrical Distribution Network, 201–235.

Zhao, Y., Liu, Y., Wu, Z., Zhang, S. & Zhang, L. Improving sparrow search algorithm for optimal operation planning of hydrogen–electric hybrid microgrids considering demand response. Symmetry 15(4), 919 (2023).

Alahakoon, S., Roy, R. B. & Arachchillage, S. J. Optimizing load frequency control in standalone marine microgrids using meta-heuristic techniques. Energies 16(13), 4846 (2023).

Ren, Y., Zhang, L., Tian, G., Wang, F., & Li, R. (2022). Optimal scheduling strategy of multiple microgrids based on improved grey wolf algorithm. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, pages 151–164.

Zhao, Y. et al. Optimization of thermal efficiency and unburned carbon in fly ash of coal-fired utility boiler via grey wolf optimizer algorithm. IEEE Access 7, 114414–114425 (2019).

Fathy, A., Kaaniche, K. & Alanazi, T. M. Recent approach based social spider optimizer for optimal sizing of hybrid PV/wind/battery/diesel integrated microgrid in aljouf region. IEEE Access, IEEE. 8, 57630–57645. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2982805 (2020).

Habib, H. U. et al. Energy cost optimization of hybrid renewables based V2G Microgrid considering multi objective function by using artificial bee colony optimization. IEEE Access 8, 62076–62093 (2020).

Qiao, M. et al. Study on economic dispatch of the combined cooling heating and power Microgrid based on improved sparrow search algorithm. Energies 15(14), 5174 (2022).

Khan, B. S., Qamar, A., Wadood, A., Almuhanna, K. & Al-Shamma, A. A. Integrating economic load dispatch information into the blockchain smart contracts based on the fractional-order swarming optimizer. Front. Energy Res. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2024.1350076 (2024).

Ramesh, M., Yadav, A. K. & Pathak, P. K. Artificial gorilla troops optimizer for frequency regulation of wind contributed Microgrid system. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4056135 (2022).

Salisu, S. (2020). Optimal planning and sizing of an autonomous hybrid energy system using multi stage grey wolf optimization. eprints.utm.my. Retrieved from http://eprints.utm.my/98225/1/SaniSalisuPSKE2020.pdf

Behera, S. & Dev Choudhury, N. B. Optimal battery management in PV + WT micro-grid using MSMA on fuzzy-PID controller: A real-time study. Sustain. Energy Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40807-024-00136-w (2024).

Monemi Bidgoli, M. (2024). Optimal energy management of water-energy nexus in multi-carrier systems integrated with renewable sources. Power Control Data Process. Syst., 1(1).

Masoudi, M. R., Haghighi, M., & Rahimipour Behbahani, M. (2024). Optimal operation of solar energy system integrated with energy storage systems. Power Control Data Process. Syst. 1(1).

Karimi, H. & Jadid, S. A strategy-based coalition formation model for hybrid wind/PV/FC/MT/DG/battery multi-microgrid systems considering demand response programs. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 136, 107642 (2022).

Haghighi, M., Masoudi, M. R., & Rahimipour Behbahani, M. (2025). Smart homes energy management system integrated with renewable energy sources and demand response programs. Power Control Data Process. Syst., 2(1).

Lasseter, R. H. Smart distribution: Coupled microgrids. Proc. IEEE 99(6), 1074–1082. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2011.2114630 (2011).

Zhang, J., Yang, G. & Li, K. Coordinated control for multi-microgrid systems. IEEE Transac. Smart Grid 6(1), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSG.2014.2329432 (2014).

Behera, S., Dev, N. B. & Choudhury, S. B. Maiden application of the slime mold algorithm for optimal operation of energy management on a Microgrid considering demand response program. SN Comput. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-023-02011-9 (2023).

Kadhem, A. A., Wahab, N. I. A. & Abdalla, A. N. Wind energy generation assessment at specific sites in a peninsula in Malaysia based on reliability indices. Processes 7(7), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7070399 (2019).

Behera, S. & Dev Choudhury, N. B. Adaptive optimal energy management in multi-distributed energy resources by using improved slime mould algorithm with considering demand side management. E-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 3, 100108 (2023).

Amirreza, N. et al. Carrier wave optimization for multi-level photovoltaic system to improvement of power quality in industrial environments based on Salp swarm algorithm. Environ. Technol. Innov. 21(2021), 101197 (2021).

Willcocks, L. P., Lacity, M. C. & Craig, A. Robotic process automation: The next transformation lever for shared services. J. Inf. Technol. Teach. Cases 5(2), 77–87 (2015).

Gallo, P., Bruno, A. & Santini, S. Energy management in microgrids using predictive control and demand side management. Appl. Energy 259, 114226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.114226 (2020).

Ali Kadhem, A., Abdul Wahab, N. I., Abdalla, N. & A.,. Wind energy generation assessment at specific sites in a peninsula in Malaysia based on reliability indices. Processes 7(7), 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7070399 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Yang, J., & Li, J. (2014). Optimal scheduling of microgrid with consideration of demand response in smart grid. IEEE PES General Meeting| Conference & Exposition, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/PESGM.2014.6939495

Khalid, F., Javaid, N. & Zafar, N. Multi-objective optimization of power scheduling in microgrids. Sustain. Cities Soc. 52, 101854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101854 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.C. and B.L. wrote the main manuscript text; H.F. Analysis, Q.Z. Methdology, and Z.L. prepared software. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, B., Li, Z., Liu, B. et al. Robust optimization for smart demand side management in microgrids using robotic process automation and grey wolf optimization. Sci Rep 15, 19440 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03728-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03728-8