Abstract

Single-atom nanozymes (SAzymes) made of iron show great potential as artificial enzymes due to their consistent active sites closely resembling the active centers found in natural enzymes. They can be produced from accessible and affordable raw materials, making them suitable options for various applications. In the present research, Iron single-atom anchored N-doped carbon (Fe–N–C) as a laccase-mimicking nanozyme was prepared using 2-methylimidazole, Zinc nitrate, and Iron(II) chloride and characterized using various techniques. Fe–N–C/DDQ was used as a bioinspired oxidative cooperative catalytic system for the oxidation of 1,4-dihydropyridine and 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones to pyridines (87–96% yield), and quinazolinones (82–94% yield), respectively, with O2 as a suitable oxidant in water/acetonitrile at room temperature. The main advantages and novelties of this method are: (1) this is the first time that the Fe–N–C SAzyme/DDQ catalyst system has been used for the aerobic oxidation of N-heterocyclic compounds (2) oxidation of a wide range of 1,4-dihydropyridines and 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones were performedusing an ideal oxidant with good to high yields under mild conditions (3) Fe–N–C SAzyme was prepared using a simple method and available and inexpensive raw materials system (4) Fe–N–C SAzyme couples the benefits of heterogeneous (easy separation and reusability) and homogeneous catalysts (high activity and reproducibility).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Enzymes are advanced catalysts that assist biological reactions within living organisms1,2,3. Nevertheless, their inherent disadvantages, such as expensive manufacturing, susceptibility to damage, time-consuming purification process, etc., have significantly restricted their broad use, encouraging ongoing attempts to create artificial enzymes4. Nanozymes, nanomaterials mimicking enzymes, have been acknowledged as a novel type of synthetic enzymes. By overcoming the current limitations of natural enzymes, they have attracted widespread attention in this field5,6,7,8. Due to their inherent characteristics like inexpensive production, easy mass production, good stability, and distinct physicochemical properties, Nanozymes have found extensive use in various applications like cancer therapy, biosensing, and antibacterial and antioxidant treatments, and they are emerging as the next generation of synthetic enzymes9. Iron-based Nanozymes, like ferromagnetic (Fe3O4) nanoparticles, were first noted for their peroxidase-like properties, making them a leading example of Nanozymes with strong potential for tumor catalytic therapy and combating antimicrobial resistance10,11. Nevertheless, the catalytic effectiveness of iron oxide nanoparticles is frequently inferior to that of natural enzymes due to the lower utilization rate of iron atoms in catalysis12. With Quick progress and an increasingly thorough comprehension of nanoscience and nanotechnology, single-atom nanozymes with metal atoms dispersed individually on supports have effectively tackled the challenges9,13,14,15. The distinct features of the SAzyme result in higher atom utilization rates compared to nanoparticles, which can be attributed to its specific geometric and electronic structures16,17. By optimizing the metal centers and ligand environment, SAzymes achieved equal or superior catalytic performance compared to their natural counterparts18,19,20,21. For example, iron single-atom Nanozymes contain active sites like FeN4, FeN5, or FeN3P, showing catalytic efficiency and kinetics as natural enzymes18,22. Also, SAzymes can be produced from accessible and affordable raw materials, making them suitable options for various applications. Hence, the SAzymes have attracted significant interest, as evidenced by the rapid increase in published articles9,21. Recently, the SAzymes were employed as heterogeneous catalysts for aerobic oxidation reactions23,24. The most efficient strategy to extend the application of SAzymes in theaerobic oxidation of organic compounds is the simultaneous use of these single-atom catalysts and mediators.

A specific stoichiometric organo-oxidant that can carry out a variety of organic transformations is 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ)25,26,27. Nonetheless, the stoichiometric application of DDQ produces equimolar amounts of the 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-hydroquinone (DDQH2) byproduct that results in challenging purification on an extensive scale. Furthermore, DDQ is toxic and expensive. As a result, to mitigate these drawbacks, utilizing a catalytic quantity of DDQ alongside safe and eco-friendly oxidants that restore DDQ from its reduced hydroquinone state has garnered more interest as a potential substitute for the commonly employed traditional DDQ in organic synthesis. There are various stoichiometric co-oxidants used to regenerate DDQ, including MnO2 (up to 6 equivalents)28, Mn(OAc)3 (3 equivalents)29, and FeCl3 (3 equivalents)30. Though these techniques have partially solved certain issues of the stoichiometric DDQ, these reagents exhibit low atom efficiency. Green chemistry promotes the development of eco-friendly processes that utilize O2 or air as an efficient, environmentally safe, and plentiful oxidant while reducing the production of harmful substances31. Thus, it would be perfect if molecular O2 or air could act as the final oxidizing agent in reactions mediated by DDQ. However, DDQH2 cannot be transformed into DDQ through a direct reaction with molecular oxygen at mild temperatures32,33. Certainly, a redox compound ought to serve as the link between molecular O2 and the DDQH2/DDQ cycling. Within this specific situation, various research teams have employed NO/NO2-based redox cycle systems alongside DDQ to facilitate the aerobic oxidizing of organic substances, which encompasses the oxidative cleavage of benzylic ethers34, oxidation of alcohols35, and amination of arenes35, and dehydrogenation of saturated carbon–carbon bonds36. Recently, enzymes have been utilized as a cocatalyst in combination with catalytic DDQ in oxidation reactions conducted under aerobic conditions37. Despite these methods showing significant advancements in aerobic oxidation reactions with a catalytic amount of DDQ, the need for a stable, effective, and inexpensive cocatalyst, when used with DDQ, is highly desired for catalyzing the aerobic oxidation of organic compounds under mild conditions. The best alternative to enzymes is SAzymes.

Heterocyclic compounds are diverse organic compounds found in biologically active synthetic and natural materials, synthetic intermediates, and pharmaceutical products38,39,40,41,42. Heterocycles consist of a ringed structure containing a heteroatom such as oxygen, sulfur, or nitrogen rather than carbon. Due to their great significance in various fields such as drug design, medicinal chemistry, and functional materials, synthesizing heterocyclic compounds, especially ones with oxygen and nitrogen, has gained immense attention in organic synthesis43,44,45,46,47,48,49. Quinazolinones are nitrogen-containing bicyclic compounds, that have attracted significant attention among various nitrogen-containing heterocycles50,51,52,53. The heterocyclic structure of quinazolinone and its derivatives plays a crucial role in various cellular processes. They are well-known for their significant therapeutic benefits in treating hypertension, infections, high cholesterol, inflammation, Alzheimer’s disease, and seizures54,55,56,57,58. Due to their significant applications, numerous synthetic efforts have been dedicated to quinazolinone and its derivatives. Despite the extensive efforts in synthesizing quinazolinones, these methods still suffer from several drawbacks, including the use of costly stoichiometric oxidants, high temperatures, prolonged reaction times, and other inherent limitations59,60,61,62,63,64,65.

Pyridines, a crucial category of heterocycles, are frequently found in scents and flavors and natural substances, agricultural chemicals, medications, dyes, and polymers66,67. They are utilized as reactants and essential elements in organic synthesis, also serving as ligands in coordination chemistry37,68,69. Traditionally, 1,4-dihydropyridines are synthesized through a one-pot reaction of β-ketoesters, aldehydes, and an ammonia source. These dihydropyridine compounds can then be oxidized to yield pyridines66,70. However, these methods come with certain unavoidable drawbacks, such as the need for expensive stoichiometric oxidants, the excessive use of additives, the production of undesirable by-products, and the requirement for high temperatures71,72,73,74,75,76. Given the importance of pyridines and quinazolinones and the challenges in their production, developing catalytic systems for their efficient synthesis is essential.

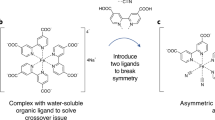

Based on our best knowledge, no reports have been published on employing SAzymes/mediators as a bioinspired cooperative catalyst system in the aerobic oxidation of organic compounds. Continuing our systematic research on the application of the Laccase-mediated system in organic synthesis37,64,75,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87, herein, we report Fe–N–C (laccase-like) with DDQ for aerobic oxidation of 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones and 1,4-dihydropyridines compounds under mild conditions (Scheme 1).

Experimental

Materials and instrumentation

Every chemical and solvent used in the synthesis of Fe–N–C, including Iron(II) chloride tetrahydrate (FeCl2·4H2O), Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2∙6H2O), 2-methylimidazole (CH3C3H2N2H), DDQ, and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Furthermore, Acetonitrile (CH3CN), EtOAc, n-Hexane, and Ethanol (EtOH) were purchased from Merck without further purification. The instruments used to characterize Fe–N–C included XRD, HRTEM, ICP-OES, FT-IR, FE-SEM, EDX, TEM, and BET.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using Co Kα (λ = 1.78897 Å) radiation, with a 2θ scan rate of 5°/min. The Zeiss-EM10C field emission microscope, operating at 200 kV was used to capture TEM images. The structure of the nanocomposites was examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope(FESEM-TESCAN MIRA3). Iron (Fe) loadings within the Fe–N–C SAzyme were quantified using an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, 730-ES Varian). Surface characteristics of the samples were analyzed through nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms at a temperature of −197 °C with a micromeritics ASAP 2000 device, and the pore size and surface area distribution were evaluated using BJH and BET methods. Analysis with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was conducted using the MIRA3TESCANXMU equipment. FT-IR spectra were recorded using a BRUKER spectrophotometer model VRTEX 70 in KBr pellets and presented in cm−1. Also, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was used to determine the main structure of the sample. The Raman analysis was performed using a HORIBA HR Evolution spectrometer with an argon ion laser (532 nm) as the excitation light source.

Synthesis of Fe–N–C SAzyme

Fe–N–C was synthesized based on the method reported by Xing et al.88 with some modifications as follows:

In a round-bottom flask of 150 mL, 1.31 g of 2-methylimidazole (16 mmol) and 40 mL of deionized water were added to 1.46 mL of Aniline (16 mmol) at room temperature and the mixture was vigorously stirred to obtain a homogenous solution, which was labeled as solution A. In the following, a solution of 1.18 g of Zn(NO3)2∙6H2O (4 mmol) and 0.039 g of FeCl2∙4H2O (0.2 mmol), in 40 mL distilled water was added to solution A. The composition was whisked for 4 h at room temperature. Afterward, the product was separated using centrifugation, washed with deionized water for further purification, and dried at 60 °C. Ultimately, the powder was exposed to pyrolysis in quartz boats under an N2 atmosphere, beginning at room temperature and gradually reaching 900 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min. The temperature was kept constant for 1 h to produce Fe–N–C.

A general procedure for aerobic oxidation of 1,4-dihydropyridines to pyridines in the presence of Fe–N–C/DDQ catalyst system

A round-bottomed flask was loaded with 70 mg of Fe–N–C (containing 0.043 mmol of Fe) along with DDQ (0.1 mmol), 1,4-dihydropyridine (1 mmol), and 2 mL of MeCN/H2O (1:1). Afterward, the mixture was stirred at room temperature under an oxygen (O2) atmosphere (using a balloon) for the duration specified in Table 2. Following the completion of the reaction, as confirmed by TLC (EtOAc/n-Hexane, 4:1), the Fe–N–C was filtered, the product was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10), and the combined organic phases were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated using a vacuum pump. The crude product underwent purification through flash chromatography on SiO2. The products were identified by comparing their physical characteristics (melting point) and NMR with authentic samples.

A general procedure for aerobic oxidation of 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones to quinazolinones in the presence of Fe–N–C/DDQ catalyst system

In a flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, 80 mg Fe–N–C (containing 0.050 mmol of Fe) was mixed with 2 mL of MeCN/H2O (1:1), 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones (1 mmol), and DDQ (0.2 mmol). Then, the solution was whisked at room temperature under O2 (balloon) for the time indicated in Table 3. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC (EtOAc/n-Hexane, 2:3). After the reaction was consummate, the Fe–N–C was separated by filtration and the reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL), the organic phase was dried using anhydrous Na2SO4, and the solvent was removed with a vacuum pump. Ultimately, the crude product underwent purification through column chromatography on SiO2 using a mixture of n-Hexane and ethyl acetate (3:1).

Results and discussion

Characterization of Fe–N–C SAzyme

The general synthetic method of Fe–N–C is summarized in Scheme 2. A Fe single-atom/N-doped carbon material (Fe–N–C) was initially synthesized with aniline and imidazolate (ZIF) at 900 °C for 1 h, based on the procedure mentioned. ZIFs are an emerging subclass of MOFs consisting of transition-metal cations and ligands based on imidazole, which have attracted much attention in heterogeneous catalysis due to their plentiful functionalities, exceptional chemical and thermal stabilities, rapid electron transfer ability, and unimodal micropores89. The presence of aniline can attach to the surface of ZIFs, aiding in the creation of small-scale particles and increasing the specific surface area88. In addition, heating up to 900 °C leads to the vaporization of zinc to achieve a greater BET surface area in the final products, and the formation of extensively graphitized carbon improves the electronic interaction of Fe–N–C. In continuation of research about the Fe–N–C SAzyme, the catalytic performance of Fe–N–C was assessed through the reaction of 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones and 1,4-dihydropyridines.

FT-IR studies

As presented in Fig. 1, the FT-IR approaches can characterize and confirm the preparation of the catalyst in the comparative FT-IR absorption of structures 2-methylimidazole and Fe–N–C. The absorption observed within the bounds of 600–1500 cm−1 is indicative of the stretching and bending mode of the imidazole ring (Fig. 1A). The FT-IR spectra of Fe–N–C exhibited absorptions around 1145 and 485 cm−1 which could be attributed to the vibrations of the C-N and Fe–N respectively (Fig. 1B)90.

FE-SEM and TEM studies

FE-SEM is a useful technique for analyzing synthesized nanoparticles’ morphology and particle size distribution, Fig. 2 Shawns FE-SEM images of the Fe-ZIF and Fe–N–C SAzyme catalyst. As shown, spherical particles with dimensions under 35 nm are observed in Fe–N–C without obvious changes in morphology compared to Fe–N–C starting material (ZIF)88,91.

Furthermore, TEM analysis was conducted on Fe–N–C to gain a more in-depth understanding of the structure. The resulting image can be seen in Fig. 3 at various magnifications. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) examination reveals that the Fe–N–C nanocomposite contains no highly crystalline Fe. Consequently, it validates the presence of Fe in the form of single atoms (Fig. 3).

EDX and elemental mapping analysis

The element composition of the synthesized Fe–N–C SAzyme was studied using EDX and elemental mapping analysis which showed the existence of Fe, C, and N in the prepared SAzyme (Fig. 4). The results confirmed the successful immobilization of Fe metal on the substrate. Further, the images from elemental mapping confirmed that N and Fe were successfully fine-doped into the carbon matrix (Fig. 5). The result of the ICP-AES analysis of Fe–N–C showed metal content (3.5 wt%) in this synthesized SAzyme.

XRD pattern studies

X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD) of the Fe–N–C is presented in Fig. 6. The XRD analysis revealed two characteristic diffraction peaks at 26° and 44°, which can be indexed to the (002) and (101) planes of graphitic carbon. The XRD pattern of the Fe–N–C catalyst confirms the successful anchoring of single-atom iron to nitrogen sites in the carbon matrix, as evidenced by the absence of characteristic metallic iron peaks92.

HRTEM studies

An examination of iron nanoparticles was conducted utilizing a high-resolution transmission electron microscope. In the HRTEM image of the Fe–N–C catalyst, the distinct dots representing Fe single atoms spread throughout the carbon support can be identified owing to the varying atom Z-contrast. Hence, significant quantities of individual iron atoms were detected and highlighted with white circles as typical examples, demonstrating the successful creation of iron single-atom sites (Fig. 7)88,93.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms studies

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were used to examine the specific surface area and porous size distributions of Fe–N–C (Fig. 8). The diagram shows a type IV hysteresis loop, which, according to the IUPAC classification, type four isotherms indicate the presence of micro/mesopores in Fe–N–C. Furthermore, according to BJH analysis, the surface area, the pore volume, and the pore size of the catalyst are 236.32 m2 g−1, 1.097 cm3 g−1, and 1.29 nm, respectively.

Iron species mainly exist in the form of Fe2+ and Fe3+ in the Fe–N–C structure88.

Raman studies

The D band (defect) at 1369 cm−1 and G band (graphitic) at 1594 cm−1 indicate that the surface of Fe–N–C contains both defect and graphitic carbon. These features facilitate the exposure of active iron sites and enhance electronic conductivity (Fig. 9)88.

Catalytic studies

Continuing, we examined the catalytic performance of Fe–N–C in the oxidation of oxidizing 1,4-dihydropyridines to pyridines.

First, the 1,4-dihydropyridine reaction was selected as the model reaction to optimize conditions using the Fe–N–C/DDQ catalyst system. As shown in Table 1, the effect of various reaction parameters, such as the amount of catalyst, DDQ, and solvent, has been thoroughly investigated. To identify the most suitable solvent for the reaction, we tested the method using various solvents, including MeCN, EtOH, MeCN/H2O, and H2O (Table 1, entries 8–11). The results indicated that MeCN/H2O was the optimal solvent for the reaction. Furthermore, the reaction was carried out in various amounts of Fe–N–C (Table 1, entries 1–5). With just 70 mg of Fe–N–C, the reaction proceeded rapidly, and the products were formed with high efficiency. Without Fe–N–C, the reaction mixture did not progress, resulting in the lowest yield (Table 1, entry 12). Also, the effect of different amounts of the DDQ in the reaction was studied (Table 1, entries 5–8). As anticipated, the desired product was obtained using 10 mol% DDQ, which emerged as the optimal condition (Table 1, entry 8). The reaction had a very low yield in the presence of Fe-Zif and FeCl2•4H2O, which serve as precursors to Fe–N–C (Table 1, entries 14 and 15). Additionally, Fe3O4 and CoFe2O4 were also used as catalysts, but they did not exhibit catalytic activity, which might be due to the inability of air to regenerate them (Table 1, entries 16 and 17). Ultimately, the reaction wasexecuted in an open flask, and completed after 12 h with satisfactory results (Table 1, entry 18).

Following the optimization of reaction conditions, various derivatives of 1,4-dihydropyridines were studied in the presence of a Fe–N–C/DDQ catalyst system (Table 2). The data in Table 2 indicates that the electronic structure of the R substituent at the C-4 position can influence the rate of oxidative aromatization in the examined 1,4-DHPs. The data presented in Table 2 suggests that 1,4-DHPs with electron-withdrawing aromatic substituents exhibit a relatively lower yield of oxidative aromatization when compared with those with electron-rich substituents (Table 2, entries 1–10). The reaction was highly effective for 1,4-DHP featuring a cinnamyl substituent group, as indicated in Table 2 (Entry 11). Previous studies have shown that the oxidative reactions of 1,4-DHPs can yield a mixture of both 4-substituted and unsubstituted pyridines71,72,73. A comparison of our findings with those in Ref.71,72,73 suggests that the experimental conditions used in our study are relatively mild.

Furthermore, the activity of the Fe–N–C synthesized catalyst in the oxidation of 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones to Quinazolinones was also investigated. As shown in Table 3, the effect of various reaction conditions, such as the amount of catalyst, DDQ, and solvent, was studied. At first, the impact of different solvents such as MeCN, EtOH, MeCN/H2O, and H2O was examined. The results revealed that MeCN/H2O is an appropriate solvent for this reaction (Table 3, entries 6–9). Next, the impact of various amounts of Fe–N–C on the reaction’s results was examined, revealing that with 80 mg of catalyst, the reaction proceeded rapidly and the products were formed with high efficiency (Table 3, entries 1–3). Without the Fe–N–C, the reaction showed no progress after 24 h (Table 3, entry 11). Also, the reaction did not advance in the presence of Fe-Zif and FeC12.4H2O (Table 3, entries 12,13). As shown in Table 3, the optimal conditions for the reaction were achieved with 20 mol% of the DDQ, which completed the reaction efficiently (Table 3, entries 2,4–6).

After obtaining the appropriate optimal conditions, various derivatives of 2,3-dihydroquinazolinone were studied in the presence of a Fe–N–C/DDQ catalyst (Table 4). The data presented in Table 4 demonstrate that 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones with electron-donating (e.g., 4-methylbenzyl, 4-methoxybenzyl, …) and electron-withdrawing (e.g., chlorobenzyl, bromobenzyl, …) groups were efficiently transformed into their respective products with very good to excellent yields (Table 4, entries 1–11). It was also observed that the current method is highly effective for the oxidation of 2,3-dihydroquinazolinone substituted with 5-methyl furan-2-yl groups (Table 2, entry 12).

According to previous reports25,27,82,86,102, the proposed mechanisms for the aerobic oxidation of 1,4-dihydropyridines and 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones have been presented in Scheme 3, respectively. At first, a radical cation (intermediates A and B in Scheme 3) and a DDQ radical anion are produced by a single electron transfer from the 1,4-dihydropyridines or 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones to DDQ. The radical oxygen in the DDQ abstracts a hydrogen atom in its radical form. Then the anionic oxygen of the DDQ abstracts the proton atom attached to the nitrogen, forming the target products (pyridines and quinazolinones) and DDQH2. Fe–N–C regenerates the reduced DDQH2, leading to DDQ and a reduced form of Fe–N–C. Ultimately, molecular oxygen can reenergize Fe–N–C and complete the catalytic cycle (Scheme 3A and B).

The benefits of this catalyst compared to other catalysts’ performance are as follows. Our study comparing different catalysts indicates that the Fe–N–C catalyst performs better than previously reported catalysts in the oxidation of 1,4-dihydropyridines (Table 5) and 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones (Table 6). Factors such as ease of Fe–N–C separation, selectivity reaction temperature, reaction time, and yield all clearly show the superior status of the Fe–N–C/DDQ catalytic system. This catalyst provides high efficiency with good to high yields under mild conditions and demonstrates significant advantages in terms of environmental impact. Compared to existing catalytic systems, the Fe–N–C/DDQ catalyst system offers a more sustainable and environmentally friendly solution for this important transformation.

Recycling of Fe–N–C SAzyme

For practical reasons, the ease of recycling the catalyst is very beneficial. To explore this matter, we focused on the reusability of Fe–N–C SAzyme. The recyclability was studied for the aerobic oxidation of 2,6-dimethyl-4-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate under optimized conditions. After the completion of the reaction, the Fe–N–C was collected using centrifuges (3000 rpm, 3 min) and washed several times with ethanol, permitting the Fe–N–C to be reused in subsequent reaction runs. As shown in Fig. 10, the Fe–N–C can be recycled up to 5 runs without any significant activity loss. The structure of recycled Fe–N–C was studied using FE-SEM and TEM analyses. This SAzyme’s FE-SEM, TEM, and FT-IR analyses showed that Fe–N–C retained its chemical structure after the fifth run (Fig. 11A, B, and C).

Large-scale synthesis experiment for the model reaction

To highlight the feasibility of the Cu–N-C/DDQ catalyst system for large-scale oxidation of 1,4-dihydropyridine, a synthesis experiment was carried out under the optimized conditions outlined in Table 1. This experiment utilized 10 mmol of diethyl 2,6-dimethyl-4-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate, along with DDQ (1 mmol), Cu–N-C (700 mg), and CH3CN/H2O as a solvent (1:1, 20 mL) under an oxygen atmosphere (balloon) at room temperature. The product was successfully obtained after 11 h, achieving a 90% yield. As expected, this approach proves economical and practical for producing these compounds (Scheme 4).

Conclusions

In summary, an iron single-atoms SAzyme (Fe–N–C) was prepared and utilized as a nanozyme resembling laccase in a highly efficient Fe–N–C/DDQ catalyst system for the aerobic oxidation of a wide range of 1,4-dihydropyridines and 2,3-dihydroquinazolinones for the first time. This method stands out due to its more effective, easier-to-use, and more feasible approach compared to other reported methods. The use of O2 as an ideal oxidant, Fe–N–C as a highly efficient and reusable SAzyme, aqueous media as the solvent, and ambient temperature contribute to its advantages. Additionally, this novel cooperative catalyst system demonstrates high efficiency, selectivity, and a low metal content in Fe–N–C, making it a sustainable and environmentally friendly solution. These benefits enable the system to accomplish other organic transformations effectively. Further optimization and refinement of this cooperative catalyst system are currently underway in our laboratory.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Rui, J. et al. Directed evolution of nonheme iron enzymes to access abiological radical-relay C (sp3)− H azidation. Sci. 376, 869–874. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj28 (2022).

Wang, K.-Y. et al. Bioinspired framework catalysts: From enzyme immobilization to biomimetic catalysis. Chem. Rev. 123, 5347–5420. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00879 (2023).

Zhang, L., Wang, H. & Qu, X. Biosystem-inspired engineering of nanozymes for biomedical applications. Adv. Mater. 36, 2211147. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202211147 (2024).

Huang, J. et al. Unnatural biosynthesis by an engineered microorganism with heterologously expressed natural enzymes and an artificial metalloenzyme. Nat. Chem. 13, 1186–1191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-021-00801-3 (2021).

Wei, H. et al. Nanozymes: A clear definition with fuzzy edges. Nano Today 40, 101269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2021.101269 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): Next-generation artificial enzymes (II). Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 1004–1076. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cs00457a (2019).

Huang, Y., Ren, J. & Qu, X. Nanozymes: Classification, catalytic mechanisms, activity regulation, and applications. Chem. Rev. 119, 4357–4412. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00672 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. An erythrocyte-templated iron single-atom nanozyme for wound healing. Adv. Sci. 11, 2307844. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202307844 (2024).

Guo, Z., Hong, J., Song, N. & Liang, M. Single-atom nanozymes: From precisely engineering to extensive applications. Acc. Mater. Res. 5, 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1021/accountsmr.3c00250 (2024).

Qin, T. et al. Catalytic inactivation of influenza virus by iron oxide nanozyme. Theranostics. 9, 6920. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.35826 (2019).

Chen, M. et al. Ultrasound-enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species for MRI-guided tumor therapy by the Fe@ Fe3O4-based peroxidase-mimicking nanozyme. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 639–647. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.9b01006 (2019).

Zandieh, M. & Liu, J. Nanozyme catalytic turnover and self-limited reactions. ACS Nano 15, 15645–15655. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c07520 (2021).

Huang, L., Chen, J., Gan, L., Wang, J. & Dong, S. Single-atom nanozymes. Sci. Adv. 5, 5490. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aav5490 (2019).

Cai, S., Zhang, W. & Yang, R. Emerging single-atom nanozymes for catalytic biomedical uses. Nano Res. 16, 13056–13076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-023-5864-y (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Engineering single-atom nanozymes for catalytic biomedical applications. Small 19, 2300750. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202300750 (2023).

Ji, S. et al. Chemical synthesis of single atomic site catalysts. Chem. Rev. 120, 11900–11955. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00818 (2020).

Jiao, L. et al. When nanozymes meet single-atom catalysis. Angew. Chem. 132, 2585–2596. https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.201905645 (2020).

Ji, S. et al. Matching the kinetics of natural enzymes with a single-atom iron nanozyme. Nat. Catal. 4, 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-021-00609-x (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Thermal atomization of platinum nanoparticles into single atoms: An effective strategy for engineering high-performance nanozymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18643–18651. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c08581 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Atomic-level regulation of cobalt single-atom nanozymes: engineering high-efficiency catalase mimics. Angew. Chem. 135, e202301879. https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202301879 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Regulating the N coordination environment of Co single-atom nanozymes for highly efficient oxidase mimics. Nano Lett. 23, 1505–1513. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c04944 (2023).

Xu, B. et al. A bioinspired five-coordinated single-atom iron nanozyme for tumor catalytic therapy. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107088. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202107088 (2022).

Bates, J. S., Johnson, M. R., Khamespanah, F., Root, T. W. & Stahl, S. S. Heterogeneous MNC catalysts for aerobic oxidation reactions: Lessons from oxygen reduction electrocatalysts: Focus review. Chem. Rev. 123, 6233–6256. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00424 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Nitrogen-neighbored single-cobalt sites enable heterogeneous oxidase-type catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4166–4176. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c12586 (2023).

Cheng, D. & Bao, W. Propargylation of 1, 3-dicarbonyl compounds with 1, 3-diarylpropynes via oxidative cross-coupling between sp3 C− H and sp3 C− H. J. Org. Chem. 73, 6881–6883. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo8010039 (2008).

Ohmura, T., Masuda, K., Takase, I. & Suginome, M. Palladium-catalyzed silylene-1, 3-diene [4+ 1] cycloaddition with use of (aminosilyl) boronic esters as synthetic equivalents of silylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 16624–16625. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja907170p (2009).

Guo, X., Zipse, H. & Mayr, H. Mechanisms of hydride abstractions by Quinones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13863–13873. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja507598y (2014).

Liu, L. & Floreancig, P. E. 2, 3-Dichloro-5, 6-dicyano-1, 4-benzoquinone-catalyzed reactions employing MnO2 as a stoichiometric oxidant. Org. Lett. 12, 4686–4689 (2010).

Sharma, G., Lavanya, B., Mahalingam, A. & Krishna, P. R. Mn (OAc) 3—an efficient oxidant for regeneration of DDQ: deprotection of p-methoxy benzyl ethers. Tetrahedron Lett. 41, 10323–10326. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(00)01855-4 (2000).

Chandrasekhar, S., Sumithra, G. & Yadav, J. Deprotection of mono and dimethoxy phenyl methyl ethers using catalytic amounts of DDQ. Tetrahedron Lett. 37, 1645–1646. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-4039(96)00081-0 (1996).

Liu, Y.-F. et al. Two sandwich-type uranyl-containing polytungstates catalyze aerobic synthesis of benzimidazoles. Rare Met. 43, 1316–1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-023-02532-5 (2024).

Piera, J., Närhi, K. & Bäckvall, J. E. PdII-catalyzed aerobic allylic oxidative carbocyclization of allene-substituted olefins: Immobilization of an oxygen-activating catalyst. Angew. Chem. 118, 7068–7071. https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.200602421 (2006).

Miyamura, H., Maehata, K. & Kobayashi, S. In situ coupled oxidation cycle catalyzed by highly active and reusable Pt-catalysts: Dehydrogenative oxidation reactions in the presence of a catalytic amount of o-chloranil using molecular oxygen as the terminal oxidant. ChemComm. 46, 8052–8054. https://doi.org/10.1039/C0CC02865G (2010).

Shen, Z. et al. Aerobic oxidative deprotection of benzyl-type ethers under atmospheric pressure catalyzed by 2, 3-dichloro-5, 6-dicyano-1, 4-benzoquinone (DDQ)/tert-butyl nitrite. Tetrahedron Lett. 54, 1579–1583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.01.045 (2013).

Shen, Z. et al. 2, 3-Dichloro-5, 6-dicyano-1, 4-benzoquinone (DDQ)/tert-butyl nitrite/oxygen: A versatile catalytic oxidation system. Adv. Synth. Catal. 353, 3031–3038. https://doi.org/10.1002/adsc.201100429 (2011).

Das, S., Natarajan, P. & König, B. Teaching old compounds new tricks: DDQ-Photocatalyzed C− H amination of arenes with carbamates, urea, and N-heterocycles. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 18161–18165. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201705442 (2017).

Cheng, D., Yuan, K., Xu, X. & Yan, J. The oxidative coupling of benzylic compounds catalyzed by 2, 3-dichloro-5, 6-dicyano-benzoquinone and sodium nitrite using molecular oxygen as a co-oxidant. Tetrahedron Lett. 56, 1641–1644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.02.018 (2015).

Shariati, M., Imanzadeh, G., Rostami, A., Ghoreishy, N. & Kheirjou, S. Application of laccase/DDQ as a new bioinspired catalyst system for the aerobic oxidation of tetrahydroquinazolines and Hantzsch 1, 4-dihydropyridines. CR Chim. 22, 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crci.2019.03.003 (2019).

Borah, B., Dwivedi, K. D., Kumar, B. & Chowhan, L. R. Recent advances in the microwave-and ultrasound-assisted green synthesis of coumarin-heterocycles. Arab. J. Chem. 15, 103654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103654 (2022).

Bur, S. K. & Padwa, A. The Pummerer reaction: Methodology and strategy for the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Chem. Rev. 104, 2401–2432. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020090l (2004).

Kumar, B., Babu, N. J. & Chowhan, R. L. Sustainable synthesis of highly diastereoselective & fluorescent active spirooxindoles catalyzed by copper oxide nanoparticle immobilized on microcrystalline cellulose. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 36, e6742. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.6742 (2022).

Veisi, H., Rostami, A., Amani, K. & Hoorijani, P. Copper nitrate as a powerful and eco-friendly natural catalyst for mediator-free aerobic oxidation of 2, 3-dihydroquinazolinones and 1, 4-dihydropyridines under mild conditions. J. Mol. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2024.140621 (2024).

Yang, G. et al. Dy/Ho-encapsulated tartaric acid-functionalized tungstoantimonates: Heterogeneous catalysts for isoindolinone synthesis. ChemComm. 60, 10934–10937. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4CC03675A(2024).

Xing, Z. et al. Recent advances in quinazolinones as an emerging molecular platform for luminescent materials and bioimaging. Org. Chem. Front. 8, 1867–1889. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0QO01425G (2021).

Mermer, A., Keles, T. & Sirin, Y. Recent studies of nitrogen containing heterocyclic compounds as novel antiviral agents: A review. Bioorg. Chem. 114, 105076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105076 (2021).

Patrusheva, O. S., Volcho, K. P. & Salakhutdinov, N. F. Synthesis of oxygen-containing heterocyclic compounds based on monoterpenoids. Russ. Chem. Rev. 87, 771. https://doi.org/10.1070/RCR4810 (2018).

Majumdar, P., Pati, A., Patra, M., Behera, R. K. & Behera, A. K. Acid hydrazides, potent reagents for synthesis of oxygen-, nitrogen-, and/or sulfur-containing heterocyclic rings. Chem. Rev. 114, 2942–2977. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300122t (2014).

Yang, G. et al. Mixed carboxylate ligands bridging tetra-Pr3+-encapsulated antimonotungstate: syntheses, structure, and catalytic activity for imidazoles synthesis. Inorg. Chem. 63, 22955–22961. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c04086 (2024).

Yang, G. et al. Assembly of Y (III)-containing antimonotungstates induced by malic acid with catalytic activity for the synthesis of imidazoles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 110274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2024.110274 (2024).

Yang, G.-P. et al. A meso butterfly-like Ce (III)-containing antimonotungstate with catalytic activity for synthesizing Isoindolinones. Inorg. Chem. 63, 19039–19045. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c03662 (2024).

Auti, P. S., George, G. & Paul, A. T. Recent advances in the pharmacological diversification of quinazoline/quinazolinone hybrids. RSC Adv. 10, 41353–41392. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0RA06642G (2020).

Dherbassy, Q. et al. Enantioselective copper-catalyzed borylative cyclization for the synthesis of quinazolinones. Angew. Chem. 133, 14476–14480. https://doi.org/10.1002/ange.202103259 (2021).

Hao, S. et al. Linear-organic-polymer-supported iridium complex as a recyclable auto-tandem catalyst for the synthesis of quinazolinones via selective hydration/acceptorless dehydrogenative coupling from o-aminobenzonitriles. Org. Lett. 23, 2553–2558. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00475 (2021).

Li, K. et al. Highly-stable Silverton-type U IV-containing polyoxomolybdate frameworks for the heterogeneous catalytic synthesis of quinazolinones. Green Chem. 26, 6454–6460. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4GC00877D (2024).

Liu, K. et al. Discovery, optimization, and evaluation of quinazolinone derivatives with novel linkers as orally efficacious phosphoinositide-3-kinase delta inhibitors for treatment of inflammatory diseases. J. Med. Chem. 64, 8951–8970. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00004 (2021).

Moftah, H. K. et al. Novel quinazolinone derivatives: Design, synthesis and in vivo evaluation as potential agents targeting Alzheimer disease. Bioorg. Chem. 143, 107065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2023.107065 (2024).

Rudolph, J. et al. Quinazolinone derivatives as orally available ghrelin receptor antagonists for the treatment of diabetes and obesity. J. Med. Chem. 50, 5202–5216. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm070071+ (2007).

Hwang, S. H. et al. Tumor-targeting nanodelivery enhances the anticancer activity of a novel quinazolinone analogue. Mol. Cancer Ther. 7, 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0548 (2008).

Khan, I. et al. Quinazolines and quinazolinones as ubiquitous structural fragments in medicinal chemistry: An update on the development of synthetic methods and pharmacological diversification. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 24, 2361–2381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2016.03.031 (2016).

Kim, N. Y. & Cheon, C.-H. Synthesis of quinazolinones from anthranilamides and aldehydes via metal-free aerobic oxidation in DMSO. Tetrahedron Lett. 55, 2340–2344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.02.065 (2014).

Jiang, J. B. et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-styrylquinazolin-4 (3H)-ones, a new class of antimitotic anticancer agents which inhibit tubulin polymerization. J. Med. Chem. 33, 1721–1728. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm00168a029 (1990).

Horton, D. A., Bourne, G. T. & Smythe, M. L. The combinatorial synthesis of bicyclic privileged structures or privileged substructures. Chem. Rev. 103, 893–930. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020033s (2003).

Tian, X. et al. Metal-free one-pot synthesis of 1, 3-diazaheterocyclic compounds via I 2-mediated oxidative C-N bond formation. RSC Adv. 5, 62194–62201. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5RA11262A (2015).

Davoodnia, A., Allameh, S., Fakhari, A. & Tavakoli-Hoseini, N. Highly efficient solvent-free synthesis of quinazolin-4 (3H)-ones and 2, 3-dihydroquinazolin-4 (1H)-ones using tetrabutylammonium bromide as novel ionic liquid catalyst. Chin. Chem. Lett. 21, 550–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2010.01.032 (2010).

Ghorashi, N., Shokri, Z., Moradi, R., Abdelrasoul, A. & Rostami, A. Aerobic oxidative synthesis of quinazolinones and benzothiazoles in the presence of laccase/DDQ as a bioinspired cooperative catalytic system under mild conditions. RSC Adv. 10, 14254–14261. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9RA10303A (2020).

Sun, J. et al. Metal-free oxidative cyclization of 2-amino-benzamides, 2-aminobenzenesulfonamide or 2-(aminomethyl) anilines with primary alcohols for the synthesis of quinazolinones and their analogues. Tetrahedron Lett. 59, 2099–2102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.04.054 (2018).

Huang, X. et al. An unprecedented 2-fold interpenetrated lvt open framework built from Zn6 ring seamed trivacant polyoxotungstates used for photocatalytic synthesis of pyridine derivatives. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 323, 122134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.122134 (2023).

Qilong, H., Li, K., Chen, X., Liu, Y. & Yang, G. Polyoxometalate catalysts for the synthesis of N-heterocycles. Polyoxometalates 3(1), 9140048. https://doi.org/10.26599/POM.2023.9140048 (2024).

Kwong, H.-L. et al. Chiral pyridine-containing ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 251, 2188–2222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2007.03.010 (2007).

Li, S. et al. Silver-modified polyniobotungstate for the visible light-induced simultaneous cleavage of C–C and C–N bonds. Polyoxometalates 2(2), 9140024. https://doi.org/10.26599/POM.2023.9140024 (2023).

Stout, D. M. & Meyers, A. Recent advances in the chemistry of dihydropyridines. Chem. Rev. 82, 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr00048a004 (1982).

Anniyappan, M., Muralidharan, D. & Perumal, P. T. A novel application of the oxidizing properties of urea nitrate and peroxydisulfate-cobalt (II): Aromatization of NAD (P) H modelHantzsch 1, 4-dihydropyridines. Tetrahedron 58, 5069–5073. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00461-1 (2002).

Liao, X., Lin, W., Lu, J. & Wang, C. Oxidative aromatization of Hantzsch 1, 4-dihydropyridines by sodium chlorite. Tetrahedron Lett. 51, 3859–3861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.05.091 (2010).

Anastas, P. & Eghbali, N. Green chemistry: Principles and practice. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1039/B918763B (2010).

Han, B. et al. An efficient aerobic oxidative aromatization of Hantzsch 1, 4-dihydropyridines and 1, 3, 5-trisubstituted pyrazolines. Tetrahedron 62, 2492–2496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2005.12.056 (2006).

Khaledian, D., Rostami, A., Zarei, S. A. & Mohammadi, B. Aerobic oxidative aromatization of Hantzsch 1, 4-dihydropyridines via an anomeric-based oxidation in the presence of Laccase enzyme/4-Phenyl urazole as a cooperative catalytic oxidation system. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 16, 1871–1878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13738-019-01664-9 (2019).

Zolfigol, M. A. et al. Oxidation of 1,4-dihydropyridines under mild and heterogeneous conditions using solid acids. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 3(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03245793 (2006).

Rostami, A., Abdelrasoul, A., Shokri, Z. & Shirvandi, Z. Applications and mechanisms of free and immobilized laccase in detoxification of phenolic compounds—a review. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 39, 821–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-021-0984-0 (2022).

Shokri, Z., Azimi, N., Moradi, S. & Rostami, A. A novel magnetically separable laccase-mediator catalyst system for the aerobic oxidation of alcohols and 2-substituted-2, 3-dihydroquinazolin-4 (1H)-ones under mild conditions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5899. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.5899 (2020).

Moradi, S., Shokri, Z., Ghorashi, N.,Navaee, A. & Rostami, A. Design and synthesis of a versatile cooperative catalytic aerobic oxidation system with co-immobilization of palladium nanoparticles and laccase into the cavities of MCF. J. Catal. 382, 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2019.12.023 (2020).

Saadati, S., Ghorashi, N., Rostami, A. & Kobarfard, F. Front cover: laccase‐based oxidative catalytic systems for the aerobic aromatization of tetrahydroquinazolines and related N‐heterocyclic compounds under mild conditions (Eur. J. Org. Chem. 30/2018). Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018(30), 4038–4038. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201801099 (2018).

Saadati, S., Ghorashi, N., Rostami, A. & Kobarfard, F. Laccase-based oxidative catalytic systems for the aerobic aromatization of tetrahydroquinazolines and related n-heterocyclic compounds under mild conditions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 4050–4057. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejoc.201800466 (2018).

Khaledian, D., Rostami, A. & Zarei, S. A. Laccase-catalyzed in situ generation and regeneration of N-phenyltriazolinedione for the aerobic oxidative homo-coupling of thiols to disulfides. Catal. Commun. 114, 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catcom.2018.06.007 (2018).

Rostami, A., Mohammadi, B., Shokri, Z. & Saadati, S. Laccase-TEMPO as an efficient catalyst system for metal-and halogen-free aerobic oxidation of thioethers to sulfoxides in aqueous media at ambient conditions. Catal. Commun. 111, 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catcom.2018.03.032 (2018).

Rouhani, S., Rostami, A., Salimi, A. & Pourshiani, O. Graphene oxide/CuFe2O4 nanocomposite as a novel scaffold for the immobilization of laccase and its application as a recyclable nanobiocatalyst for the green synthesis of arylsulfonyl benzenediols. Biochem. Eng. J. 133, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2018.01.004 (2018).

Rahimi, A., Habibi, D., Rostami, A., Zolfigol, M. A. & Mallakpour, S. Laccase-catalyzed, aerobic oxidative coupling of 4-substituted urazoles with sodium arylsulfinates: Green and mild procedure for the synthesis of arylsulfonyl triazolidinediones. Tetrahedron Lett. 59, 383–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.12.048 (2018).

Habibi, D., Rahimi, A., Rostami, A. & Moradi, S. Green and mild laccase-catalyzed aerobic oxidative coupling of benzenediol derivatives with various sodium benzenesulfinates. Tetrahedron Lett. 58, 289–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.11.119 (2017).

Rouhani, S., Rostami, A. & Salimi, A. Preparation and characterization of laccases immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles and their application as a recyclable nanobiocatalyst for the aerobic oxidation of alcohols in the presence of TEMPO. RSC Adv. 6, 26709–26718. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA00103C (2016).

Lin, Y., Wang, F., Yu, J., Zhang, X. & Lu, G.-P. Iron single-atom anchored N-doped carbon as a ‘laccase-like’nanozyme for the degradation and detection of phenolic pollutants and adrenaline. J. Hazard. Mater. 425, 127763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127763 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. The application of Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) and their derivatives based materials for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution and pollutants treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 417, 127914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.127914 (2021).

Gkatziouras, C., Solakidou, M. & Louloudi, M. Formic acid dehydrogenation over a recyclable and self-reconstructing Fe/activated carbon catalyst. Energy Fuels 38, 17914–17926. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.4c03191 (2024).

Liu, P. et al. Analyte-triggered oxidase-mimetic activity loss of Ag3PO4/UiO-66 enables colorimetric detection of malathion completely free from bioenzymes. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 338, 129866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2021.129866 (2021).

Park, M. et al. Oxygen reduction electrocatalysts based on coupled iron nitride nanoparticles with nitrogen-doped carbon. Catalysts 6(6), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal6060086 (2016).

Gamm, B. et al. Quantitative high-resolution transmission electron microscopy of single atoms. Microsc. Microanal. 18, 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1431927611012232 (2012).

Török, B., De Paolis, O., Baffoe, J. & Landge, S. Multicomponent domino cyclization-oxidative aromatization on a bifunctional Pd/C/K-10 catalyst: An environmentally benign approach toward the synthesis of pyridines. Synth. 2008, 3423–3428. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1083177 (2008).

Sharma, S., Choudhary, A., Sharma, S., Shamim, T. & Paul, S. TEMPO supported amine functionalized magnetic titania: A magnetically recyclable catalyst for the aerobic oxidative synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Monatsh. Chemie. 152, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-020-02714-2 (2021).

Zolfigol, M. A. et al. An efficient method for the oxidation of 1, 4-dihydropyridines under mild and heterogeneous conditions via in situ generation of NOCl. J. Chem. Res. 2003, 18–20. https://doi.org/10.3184/030823403103172788 (2003).

Wang, R. et al. Metal-free catalyst for the visible-light-induced photocatalytic synthesis of quinazolinones. Mol. Catal. 509, 111668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcat.2021.111668 (2021).

Xu, W., Jin, Y., Liu, H., Jiang, Y. & Fu & Hua.,. Copper-catalyzed domino synthesis of quinazolinones via Ullmann-type coupling and aerobic oxidative C− H amidation. Org. Lett. 13, 1274–1277. https://doi.org/10.1021/ol1030266 (2011).

Qiu, Q. et al. Design, synthesis, and pharmacological characterization of N-(4-(2 (6, 7-Dimethoxy-3, 4-dihydroisoquinolin-2 (1 H) yl) ethyl) phenyl) quinazolin-4-amine derivatives: Novel inhibitors reversing P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance. J. Med. Chem. 60, 3289–3302. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01787 (2017).

Soheilizad, M., Soroosh, S. & Pashazadeh, R. Solvent-free copper-catalyzed three-component synthesis of 2-substituted quinazolin-4 (3 H)-ones. Monatsh. Chemie. 148, 739–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-016-1804-9 (2017).

Mendogralo, E. Y. et al. The synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-(1 H-Indol-3-yl) quinazolin-4 (3 H)-one derivatives. Mol. 28, 5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28145348 (2023).

Clausen, D. J. & Floreancig, P. E. Aromatic cations from oxidative carbon-hydrogen bond cleavage in bimolecular carbon-carbon bond forming reactions. J. Org. Chem. 77, 6574–6582. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo301185h (2012).

Abdel-Mohsen, H. T., Conrad, J. & Beifuss, U. Laccase-catalyzed oxidation of Hantzsch 1, 4-dihydropyridines to pyridines and a new one pot synthesis of pyridines. Green Chem. 14, 2686–2690. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2GC35950B (2012).

Prakash, P. et al. Direct and co-catalytic oxidative aromatization of 1, 4-dihydropyridines and related substrates using gold nanoparticles supported on carbon nanotubes. Catal. Sci. Techno. 6, 6476–6479. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6CY00453A (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to the University of Kurdistan for financial support of this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. V. Visualization, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. A. R. Writing–review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Veisi, H., Rostami, A. The single Fe atoms and DDQ catalyst system for the aerobic dehydrogenation of dihydropyridines and dihydroquinazolinones. Sci Rep 15, 22673 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03750-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03750-w