Abstract

Immortalized cell lines constructed through transfecting genes such as the hTERT and the SV40-LT provide stable cellular resources for both scientific exploration and industrial implementation. Although advancements have been documented in the establishment of immortalized cell types, research on immortalization of specialized animal cell types remains an underexplored domain. To explore the applicable value of the dzo, a yak-cattle hybrid endemic to northwestern China, and develop potential cell substrates that can be used for the production of BVDV vaccines, this study adopts an immortalization strategy with the hTERT and SV40-LT genes to construct an immortalized dzo kidney cell line. This study employed a lentiviral vector system to stably integrate SV40-LT into dzo renal cells, successfully generating the immortalized NBLS cell line. Compared to liposome-mediated transfection, lentiviral delivery demonstrated superior gene transfer efficiency through high integration capacity and broad tropism. NBLS cells maintained robust proliferation (viability > 90%), normal cell cycle distribution, and diploid karyotype (2n = 60) through 50 passages, whereas hTERT-only transfectants exhibited viability decline below 70% after passage 10. Functional validation revealed NBLS cells displayed enhanced BVDV susceptibility (lgTCID50 = 10^− 6.59/0.1 mL), with tenfold increased sensitivity compared to primary counterparts. The results will provide potential materials for BVDV vaccine production and species-specific cellular models for investigating plateau-adapted disease resistance mechanisms and screening novel vaccine antigens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cellular senescence, which is a biological barrier limiting proliferative capacity, serves as the theoretical basis for creating immortalized cells by overcoming it1. Among existing immortalization strategies, two molecular tools are commonly used to establish immortalized cell lines across various life forms including humans, model organisms, and agricultural species. One is the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT), the key catalytic subunit of the ribonucleoprotein complex, which maintains replicative potential by elongating telomeric structures at chromosome termini, thereby overcoming replicative senescence2. The other is the large T antigen (LT) encoded by simian virus 40 (SV40), functioning as a viral oncoprotein that targets and inhibits tumor suppressor proteins such as p53/pRB, effectively deregulating cell cycle checkpoint controls3. The synergistic action of these two molecular mechanisms effectively overcomes the barriers to cellular proliferation: replicative senescence mediated by telomere attrition and cell cycle arrest induced by DNA damage4.

The immortalized cells constructed based on the aforementioned molecular strategies exhibit distinctive application merits5. They enable cell populations characterized by challenging subculturing, slow proliferation kinetics, and senescence predisposition to acquire sustained proliferative capacity, thereby providing a stable cellular resource for both scientific exploration and industrial implementation6. As pivotal carriers for in vitro disease modeling, these cells serve critical functions in elucidating pathogenic mechanisms, screening therapeutic strategies, and investigating tumor proliferation regulation. Currently, widely utilized immortalized cell lines include MDCK, VERO, and HELA cells. Nevertheless, the number of reported immortalized cell lines remains limited, with many early-established lines being derived from neoplastic tissues, posing biohazard risks and presenting inherent limitations in both fundamental research and practical applications7,8. Although advancements have been documented in the establishment of immortalized cell types such as porcine lung-derived monocyte-derived macrophage (IPLuM), human corneal stromal stem cells (SV40T-imCSSC), and mouse intestinal smooth muscle cells (ISMC-Hc)3,9,10, research on immortalization of specialized animal cell types remains an underexplored domain.

The interspecific hybrid dzo (yak-cattle hybrid), derived from crossbreeding between yaks and domestic cattle, exhibits unique genetic advantages in northwestern China11. Dzo exhibit significant genetic advantages in milk production traits (e.g., milk fat content) due to the polymorphism of ACACA and SCD1 genes12. Additionally, the enhanced expression of skeletal muscle metabolism and myofiber development-related genes may contribute to improved meat tenderness and water-holding capacity13. Although dzos demonstrate adaptive disease resistance against highland pathogens, current research predominantly focuses on zootechnical phenotypic traits. However, there remains a gap in exploring the relationship between cell immortalization and viral susceptibility.

Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) is a pathogen which can cause clinical symptoms such as diarrhea, gastrointestinal mucosal lesions, and reduced milk production, and it severely threatens global cattle industries14. Classified as a Class III animal disease by China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, BVDV presents formidable challenges due to its extraordinary genetic diversity and rapid mutation rate, which render existing vaccines poorly matched to antigenic variations in circulating strains15. Despite global registration of over 120 BVDV vaccines, China’s vaccine development confronts dual bottlenecks16: only three inactivated vaccine strains were domestically approved by 2021 with no imported alternatives available, and production relies on foreign-derived MDBK cell lines, which are susceptible to batch variability from limited cellular sources and individual animal differences.

To further explore the applicable value of dzo and develop potential cell substrates that can be used for the production of BVDV vaccines, this study adopts an immortalization strategy using dzo renal cells with plateau—adaptive characteristics. To overcome the limitations of in vitro passaging, the hTERT and SV40-LT genes were introduced using liposome-mediated transfection and lentiviral vector systems. The results will provide potential materials for BVDV vaccine production and species-specific cellular models for investigating plateau-adapted disease resistance mechanisms and screening novel vaccine antigens. The research also holds strategic significance for promoting utilization of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau genetic resources.

Materials and methods

Primary cell resuscitation and subculture

To resuscitate primary cells and conduct subculture, three cryopreserved primary dzo kidney cell (The cell was isolated and stored at the Biomedical Research Center of Northwest Minzu University in Lanzhou, Gansu Province) vials (F1 cells) were thawed in a 37 °C water bath with shaking (90 s), followed by 24 h incubation. Dead cells were removed by medium replacement, and adherent cells were subcultured at 1:3 upon reaching > 85% confluency, with growth status documented microscopically. For cryopreservation, F3 cells were then cryopreserved for subsequent procedures, through a step-wise freezing process: 4 °C for 30 min, − 20 °C for 1 h, and − 80 °C overnight, followed by liquid nitrogen storage17.

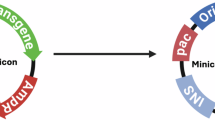

Preparation of plasmid and virus for transfection

The hTERT and SV40-LT lentiviral solutions used in the experiment were procured from Shanghai Genechem Company Limited (Co., Ltd.), and the plasmid vector containing hTERT (pcl-neo-CMV-EGFP-Linker-hTERT) was constructed by Wuhan Miaoling Biotechnology Co., Ltd. To extract and identify the plasmid, the expression vector was first transformed into DH5α competent cells, plated on ampicillin-containing Luria–Bertani (LB) agar, and incubated at 37 °C for 9–12 h. Resistant colonies were then selected, inoculated in ampicillin-supplemented LB liquid medium, and subjected to 12–16 h shaking culture prior to plasmid extraction using an extraction kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.)18. The concentration of the extracted plasmids was determined via a Nucleic Acid Ultraviolet (UV) Detection System using a dilution of 1000-fold. Plasmid integrity was verified through EcoR I/Not I (Takara Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.) double digestion, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis and sequencing for confirmation.

Screening of G418 and purinomycin

For antibiotic selection of recombinant cells, the minimum lethal concentrations of Geneticin (G418) and puromycin were determined by inoculating F3 dzo kidney cells at 1 × 104 cells/well in culture plates and allowing adherence until 50%–60% confluence. In order to determine the threshold concentration, G418 screening employed a concentration gradient (0–1000 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL increments) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines and methods reported in literature, with medium refreshed every 48 h and cellular viability monitored microscopically until complete mortality occurred between days 10–1419. Meanwhile, parallel puromycin testing was conducted and utilized a 0–10 μg/mL gradient (1 μg/mL increments) under identical culture conditions, with cell death typically observed by days 4–7 post-treatment, establishing the minimal effective dose. The photography of cellular responses was documented throughout the two assays.

Transfection and positive cell screening

According to the recommended cell number in the cell transfection instructions, F3 dzo kidney cells were inoculated in 12-well culture dishes at 1 × 104 cells/well after cell recovery. This seeding density ensured logarithmic-phase growth until reaching 1 × 105 cells/well, as determined by plate surface area and growth kinetics.

Liposome transfection was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Three plates with 85% confluent cells were transfected with the pcl-neo-CMV-EGFP-Linker-hTERT plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Untransfected cells were used as blank controls, and successfully transfected cells were referred to as NZLT.

For lentiviral transduction20, two independent sets of three plates (50% confluency) were infected with either hTERT-encoding (3445 bp) or SV40-LT-encoding (2168 bp) lentiviral particles (Shanghai Genechem). Untransfected cells were used as controls. Transfected cells were referred to as NBLT (hTERT-transduced) and NBLS (SV40-LT-transduced), respectively.

At 72 h post-transfection/transduction, fluorescent signals in NZLT, NBLT, and NBLS cells were documented via fluorescence microscopy and quantified using ImageJ. Fluorescence-positive clones were then expanded in selective media: NZLT in G418-containing medium, NBLT/NBLS in puromycin-supplemented medium. Drug-resistant monoclonal populations surviving this selection were classified as F1 generation cells, storing in liquid nitrogen for subsequent procedures.

QPCR

Cryopreserved NZLT, NBLT, and NBLS cells were thawed and cultured in T25 flasks until reaching 80%–90% confluence with optimal morphology. After removing the culture medium and washing with PBS, cells were lysed by adding 2 mL TRIzol reagent and the total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol method. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed using a reverse transcription kit (Anoroad Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) of the transfected genes (hTERT and SV40-LT) was conducted using Synergetic Binding Reagent (SYBR) Green Master Mix, with the endogenous β-Actin (ACTB) as control (detailed information of the primers is listed in Table 1). Amplification curves and Ct values were analyzed using real-time PCR instrumentation to quantify relative gene expression levels.

Western blot

Cells were lysed and washed first with ice-cold PBS and then with a buffer containing Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). After that, the cell suspension was centrifuged, and the obtained supernatants were freeze-thawed three times. Protein concentrations were determined via Bicinchoninic Acid Assay (BCA) using BCA standards. Quantified samples were mixed with loading buffer, denatured at 100 °C, and electrophoresed in PVDF gel. Proteins were then transferred to methanol-activated Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) membranes (200 mA, 90 min), blocked with 5% skim milk, and incubated sequentially with primary antibodies (hTERT, SV40-LT, ACTB; 4 °C overnight) and Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (room temperature, 1.5 h). Chemiluminescent signals were detected using Millipore reagents, and band molecular weights were analyzed via gel imaging after 10-s X-ray film exposure.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with 5% normal goat serum and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in 5% BSA, followed by 1-h incubation at room temperature with species-matched secondary antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with 4ʹ,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Beyotime Biotechnology) using an anti-fade mounting medium. Fluorescence imaging was performed using a confocal microscope (Olympus Corporation Co., Ltd.)

Cell viability and cell growth curve

Cell suspensions were loaded into counting chambers using an automated cell counter (following the manufacturer’s protocols) to ensure complete filling of the chamber, and viability measurements were recorded based on membrane integrity analysis.

Cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well in triplicate. Cells were collected, trypsin-treated to detach them from the culture surface, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min, and subsequently resuspended in single-cell suspension on a daily basis for further processing. Viable cell counts were determined using an automated counter, with the average of triplicate measurements calculated per timepoint over 12 consecutive days. Population doubling time (PDT) was calculated using the following formula: PDT = (t × log 2)/(log Nt − log N0), where t represents culture duration, N0 denotes initial cell count, and Nt corresponds to final cell count at time t.

Cell cycle detection and cell apoptosis detection

For cell cycle detection, cells were trypsinized, washed with ice-cold PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol at 4 °C for 2 h. After centrifugation at 1000 rpm and 4 °C to remove ethanol, the cells were stained with a DNA staining solution that contained 10 μL of permeabilization solution. The cell-solution mixture was briefly vortexed to ensure uniform staining and then incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Samples were analyzed using a flow cytometer with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. The acquisition speed was set at 1000 events per second (low speed) to ensure accurate data collection. Red fluorescence emission in the range of 600–700 nm was detected, along with forward and side light scattering, enabling the analysis of cell size, granularity, and the presence of fluorescently labeled molecules. Cell cycle histograms and phase distributions (G0/G1, S, G2/M) were quantified using ModFit LT (Verity Software House).

For cell apoptosis detection, cells were trypsinized, washed with ice-cold PBS, and resuspended in 500 μL 1 × Binding Buffer. After staining with Annexin V-FITC (5 μL) and PI (10 μL), samples were incubated in darkness at room temperature for 5 min. Flow cytometry (Ex/Em: 488/530 nm for Annexin V-FITC; 535/615 nm for PI) was used to quantify apoptotic subpopulations (viable, early/late apoptotic, necrotic), and the data were then analyzed using ModFit LT to generate distribution plots and percentage tables.

Chromosome karyotype analysis

Thawed cells were cultured in 6-well plates until 70%–80% confluency. Mitotic cells were arrested with 0.1 μg/mL colchicine (6 h), followed by hypotonic treatment in 0.075 M KCl (37 °C, 30 min). Cells were fixed with methanol-acetic acid (3:1), centrifuged (1500 rpm, 5 min), and washed twice. Suspensions were dropped onto pre-chilled slides from 50 cm height, air-dried, and stained with 10% Giemsa for 20 min. Chromosomal spreads were microscopically analyzed for numerical/structural abnormalities.

TCID50

To detect the sensitivity of the transfected cells to virus, cells were incubated with 10-fold diluted BVDV solution, and after grown to confluence in the 96-well culture plate. Dzo cells were cultured to confluent monolayers, trypsinized, and seeded into a 96-well plate (2 × 105–5 × 105 cells/mL, 100–200 µL/well) with two control columns containing maintenance medium. After 24 h (37 °C /5% CO2), cells were washed with PBS and infected with tenfold serially diluted BVDV (10–1–10–10 in DMEM with 2.5 μg/mL trypsin; 8 replicates/dilution). Controls were treated with PBS or medium. Plates were incubated for 72 h (37 °C /5% CO2), and cytopathic effects (CPE) were monitored daily. Viral titers (log 50% Tissue Culture Infective Dos (TCID 50)/mL) were calculated via the Reed-Muench method21:

Distance ratio = (lesion rate higher than 50%–50%)/(lesion rate higher than 50%—lesion rate lower than 50%); LgTCID50 = logarithm of maximum viral dilution above 50% lesion rate + distance ratio.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed via GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software). The data of NZLT, NBLT and NBLS cells were obtained from the transfection of the same dzo kidney cells, and all were subjected to biological replicates. The values are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the distribution of the variables. p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (ns p > 0.05, *p < 0.05).

Results

Characterization and evaluation of primary dzo kidney cells

After a one-month cryopreservation, F3 cells maintained their characteristic spindle-shaped monolayer arrangement (Fig. 1a). The cells exhibited tight intercellular connections and uniformly covered the flask surface without apparent membrane rupture or organelle disintegration. Their static adherent growth pattern showed high consistency with the polarized arrangement of normal renal tubular epithelial cells, effectively preserving cytoskeletal architecture and polarity features. Viability assessment further confirmed a survival rate of 90.15%, meeting the requirement that a cell viability rate of over 90% is needed to conduct subsequent transfection22. Post-cryopreserved cells demonstrated proliferative capacity similar to that of freshly isolated cells, maintaining excellent metabolic activity and membrane integrity. Subsequent transfection can be performed.

Morphological integrity and viability assessment of primary and immortalized cells (scale bar: 200 μm, magnification: 40×). (a) Untransfected dzo kidney cells at passage F3; (b) F10-NBLT cells; (c–h) NBLS cells from passages F3 to F50. All groups (a–h) exhibited nearly identical morphological characteristics, displaying a pavement-like monolayer adherent growth pattern with tightly connected intercellular junctions, absence of membrane rupture or organelle fragmentation, and cytoskeletal polarity consistent with the polar arrangement of normal renal tubular epithelial cells.

Application of UV spectrophotometry to evaluate the physicochemical properties of plasmids: the purity (OD260/OD280 = 1.965) indicated < 5% protein contamination, while the concentration (1003 ng/μL) satisfied transfection requirements, complemented by A260/A230 > 2.0 confirming minimal salt residue. Furthermore, PCR amplification validated the presence of the insert fragment, bidirectional restriction enzyme digestion confirmed proper gene orientation, ensuring the absence of frameshift mutations or unintended nucleotide substitutions23.

Transfection and positive cell screening

The purity of the nucleic acid sample, with an OD260/OD280 ratio of 1.965, indicated less than 5% protein contamination. The concentration, measured at 1003 ng/μL, met the transfection requirements. Additionally, an A260/A230 ratio greater than 2.0 confirmed minimal salt residue. Furthermore, PCR amplification validated the presence of the insert fragment, and bidirectional restriction enzyme digestion confirmed proper gene orientation.

Concentration gradient experiments revealed that the toxic threshold of G418 was 200 μg/mL, which falls precisely at the lower limit of the recommended range for mammalian cells (200–2000 μg/mL) (Fig. 2a–c). In contrast, the effective low concentration of puromycin was determined to be 2 μg/mL (Fig. 2d–f), a value significantly below the upper limit of 10 μg/mL reported in some literature.

Dose-dependent cytotoxicity of G418 and puromycin in dzo kidney cell monolayers (scale bar: 200 μm; magnification: 40×). This figure illustrates the morphological responses of yak renal cell monolayers to varying concentrations of G418 (upper row: a–c) and puromycin (lower row: d–f) through grayscale micrographs captured at uniform magnification (40×), with drug concentrations annotated in yellow/green text. In the G418-treated groups, untreated cells (a: 0 μg/mL) remained intact and adherent, while sporadic detachment was observed at 100 μg/mL (b), and complete cell death occurred at 200 μg/mL (c). The puromycin-treated groups exhibited progressive cell death: untreated monolayers (d: 0 μg/mL) maintained normal morphology, partial disintegration emerged at 1 μg/mL (e), and non-viable cells predominated at 2 μg/mL (f).

The results of fluorescence microscopy showed that the cells transfected with pcl-neo-CMV-EGFP-Linker-hTERT alone did not show detectable EGFP fluorescence expression after 72 h, while the cells transfected with hTERT and SV40-LT virus showed obvious green fluorescence signal (positive rate > 70%) (Table 2).

Morphological analysis

Following drug resistance screening, two cell lines, NBLT and NBLS, were successfully established and subcultured to F10 and F50 generations, respectively. The drug-selected NBLT and NBLS cell lines exhibited distinct stability profiles during passaging. At the F10 generation, NBLT cells preserved a typical spindle-shaped monolayer arrangement, with cells closely interconnected and evenly distributed. There were no significant morphological or growth state alterations, ensuring the consistent functionality of these cells (Fig. 1b). In contrast, NBLS cells exhibited progressive morphological heterogenization from F3 to F50 generations, characterized by significant cellular elongation, with the average cell length increasing by approximately 50%, and notable volume reduction, with the average cell volume decreasing by about 30% (Fig. 1c–h).

Gene stability analysis

QPCR revealed stable hTERT expression in F10-generation NBLT cells (Fig. 3a); SV40-LT remained consistently positive in NBLS cells from F3 to F50 generations (Fig. 3b), with gene copy numbers showing a non-significant increasing trend across passages (P > 0.05). Western blot further confirmed sustained protein expression of both targets, with SV40-LT showing no statistically significant differences in expression levels across generations (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3c–f), suggesting transcriptional and translational stability during intergenerational propagation24. Immunofluorescence revealed cytoplasmic localization (red fluorescence signals) of both hTERT and SV40-LT proteins, with no nuclear expression observed (blue-stained nuclear regions) (Fig. 3g–h), contrasting with previously reported nuclear localization patterns of SV40-LT.

Exogenous gene expression and localization of hTERT and SV40-LT in NBLT and NBLS cells. (a) qPCR quantification of hTERT gene copies in F10 NBLT cells (y-axis: relative copy number; x-axis: cell passage number, *P < 0.05); (b) qPCR quantification of SV40-LT gene copies in F3–F50 NBLS cells (y-axis: relative copy number; x-axis: cell passage number, *P < 0.05); (c) Western blot analysis of hTERT protein (y-axis: band intensity; lanes: F10 NBLT vs. control). (d) Quantification of hTERT protein by Western blotting (y-axis: normalized intensity; x-axis: cell passages F3–F10; *P < 0.05). (e) Quantification of SV40-LT protein by Western blotting (y-axis: normalized intensity; x-axis: cell passages F3–F50; *P < 0.05). (f) Western blot analysis of SV40-LT protein (y-axis: band intensity; lanes: F3–F50 NBLS vs. control); (g) Immunofluorescence localization of hTERT in NBLT cells and (h) SV40-LT in NBLS cells (scale bar: 100 μm; magnification: 100 ×). Red fluorescence (hTERT/SV40-LT antibody) indicates cytoplasmic localization of the proteins, while blue (DAPI) marks the nuclei. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using GraphPad Prism software.

Cell growth characteristics analysis

Untransfected dzo renal cells exhibited excellent viability (> 90%) and proliferative capacity with a doubling time of approximately 27 h, displaying a growth curve characterized by entry into the logarithmic growth phase on day 3, during which the cells showed a more elongated and densely packed morphology, and peak density attainment by day 5 (Fig. 4a,b). In contrast, transfected F10 NBLT cells showed significantly reduced viability (< 70%), prolonged doubling time exceeding 40 h, and a linear growth pattern. The cells appeared more irregular in shape and less densely packed, with persistently slow proliferation from days 1–7, indicating severe impairment of proliferative capacity (Table 3). Meanwhile, NBLS cells maintained consistently high viability (> 90%) across passages F3 to F50, demonstrating growth kinetics that were identical to those of untransfected cells. They entered the logarithmic phase on day 3 and reached peak density by day 8. This similarity in growth patterns strongly confirmed their superior genetic stability, suggesting that the transfection process did not significantly disrupt the fundamental growth characteristics and genetic integrity of NBLS cells.

Proliferation dynamics and cellular health status of transfected cells (NBLT/NBLS) versus untransfected dzo kidney cells in growth, cell cycle, and apoptosis characteristics. (a) (NBLT growth curve) : With time (days) as the X-axis and cell density (× 104/mL) as the Y-axis, F10 NBLT cells exhibited linear proliferation from days 1–7, peaking on day 8 (P ≤ 0.05); (b) (NBLS growth curve) : NBLS cells (passages F3–F50) showed a growth pattern similar to untransfected cells, entering the logarithmic growth phase by day 3 and peaking on day 8 (P ≤ 0.05); (c) (Cell cycle distribution) : Untransfected cells displayed balanced G1/S phase proportions (~ 40% each) with 11.78% in G2 phase, while F10 NBLT cells exhibited marked G1 phase arrest (> 90%) and minimal S/G2 phase representation (< 5%, P ≤ 0.05); (d) (Apoptosis rate) : F10 NBLT cells demonstrated significantly higher apoptosis (> 10%) and reduced viability (< 90%) compared to untransfected controls (apoptosis < 2%, viability > 95%). In contrast, NBLS cells maintained low apoptosis rates (< 2%) across all passages, indicating no transfection-associated toxicity (P > 0.05).

The F10 NBLT cell line exhibited abnormal cell cycle distribution, with G1 phase proportion exceeding 90% and S/G2 phases accounting for less than 5%, which was markedly higher than non-transfected cells (G1/S phases each approximately 40% and G2 phase 11.78%) (Table 4, Fig. 4c). Concurrently, its apoptosis rate surpassed 10%, with viable cell ratio below 90%, forming a stark contrast to non-transfected counterparts (apoptosis rate < 2% and viability > 95%). In contrast, NBLS cells maintained apoptosis rates below 2% across passages, while their G1/S phase proportions showed no statistical divergence from non-transfected cells (both > 40%), indicating preserved anti-apoptotic capacity unaffected by transfection (Table 5, Fig. 4d).

In summary, NBLS cells demonstrated sustained viability and stable proliferative capacity through 50 successive passages, whereas F10 NBLT cells exhibited a precipitous decline in survival rates with complete cessation of mitotic activity beyond this stage, rendering them incapable of serial propagation.

Genetic trait analysis

Karyotype analysis revealed that the diploid chromosome number of transfected cells (NBLT and NBLS) remained stable at 2n = 60, consistent with untransfected controls (Fig. 5a). Immunofluorescence assays showed cytoplasmic red fluorescence signals for both vimentin (a mesenchymal marker) and cytokeratin-18 (an epithelial marker), with DAPI-stained nuclei appearing blue (Fig. 5b,c). Overall, the transfection process preserved genomic integrity without inducing phenotypic aberrations.

Genetic and phenotypic traits of transfected NBLT/NBLS cells evaluated through karyotype analysis and immunofluorescence staining. (a) displays six metaphase chromosome spreads (three transfected NBLT/NBLS cells and three controls) stained with G/Q banding, showing a diploid chromosome number of 2n = 60 (scale bar: 10 μm; magnification: 1000×). No aneuploidy or structural abnormalities (e.g., breaks, translocations) were observed, as validated by the clarity of chromosome dispersion and banding patterns. Panels (b) and (c) present immunofluorescence grids (12 images per marker) with cytoplasmic red fluorescence for vimentin and cytokeratin-18, alongside blue DAPI-stained nuclei (scale bar: 100 μm; magnification: 100×).

Functional verification

The results of viral infection demonstrated that the viral titer in F50 NBLS cells (lgTCID50 = 10^− 6.59/0.1 mL) exhibited an approximately tenfold enhancement compared to F3 cells (10^− 5.62/0.1 mL) (Table 6), with this disparity conforming to the Poisson distribution pattern25.

Discussion

This study employed liposome and lentiviral transfection approaches to introduce hTERT and SV40-LT genes for establishing an immortalized dzo renal cell line. Our results demonstrated that liposome-mediated hTERT transfection was unsuccessful, as no detectable hTERT gene expression was observed in the transfected cells. In contrast, lentiviral vectors achieved stable and high-level expression of both hTERT and SV40-LT genes while maintaining normal karyotypes in transfected cells, indicating the efficiency and safety of this transfection method. However, lentivirally transfected hTERT cells (NBLT) exhibited limited proliferation capacity, sustaining only up to passage F10. In contrast, SV40-LT-transfected cells (NBLS) demonstrated significantly enhanced proliferative activity with relatively stable cellular states during serial passaging. These cells have been successfully propagated to passage F50.

Transfection efficiency is significantly influenced by factors such as cell type and transfection method. Notably, lipid-based reagents such as Lipofectamine 3000 exhibit inherent cytotoxicity during transfection processes, frequently inducing cell death while demonstrating substantial limitations in delivery efficacy. Studies have shown that cells treated with liposomal reagents exhibited a significant decline in viability (average survival rate 60%–70%) within 24 h post-transfection, whereas optimized electroporation techniques maintained over 80% cell survival26,27. Mechanistic investigations further demonstrated that cationic liposomes trigger cellular stress responses through activation of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome pathways, ultimately leading to apoptosis or necrosis, an effect particularly pronounced in immune cells like macrophages28,29. In this study, concordant results from quantitative fluorescence intensity analysis and fluorescence-positive rate detection confirmed the failure of liposome-mediated transfection to achieve effective gene delivery, thereby validating the suboptimal performance of this methodology in specific experimental systems.

Our study showed that the hTERT (3445 bp) and SV40-LT (2168 bp) genes were successfully transfected into cells via lentiviral vectors, with results demonstrating significantly higher transfection efficiency and qPCR quantification levels for SV40-LT compared to hTERT. This discrepancy may be attributed to the high GC content (> 65%) of the hTERT sequence, as DNA templates exceeding 60% GC content are prone to form secondary structures such as hairpin loops or G-quadruplexes, which impede primer binding and polymerase extension during PCR amplification, thereby reducing amplification efficiency and compromising transfection outcomes30. Functional analysis revealed that while hTERT delays cellular senescence through telomerase activation-mediated telomere elongation, its standalone application typically fails to achieve complete immortalization in specific cell types like fibroblasts, necessitating synergistic cooperation with SV40-LT. In contrast, SV40-LT directly inhibits tumor suppressor proteins p53 and pRB, effectively disrupting cell cycle regulation and apoptosis pathways to induce immortalization more efficiently31,32. This mechanistic divergence explains SV40-LT’s superior immortalization capacity observed in the current study. Furthermore, SV40-LT exhibits broader applicability, successfully immortalizing diverse cell types including fibroblasts and epithelial cells, whereas hTERT demonstrates complete inefficacy in certain models such as chicken preadipocytes, highlighting distinct target specificity and cell-type dependency between the two genes33.

During the serial passaging of NBLS F3-F50 cells, the observed morphological elongation and size reduction may reflect a metabolic shift toward glycolysis. The elongated morphology could be associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers34, potentially involving downregulation of E-cadherin and upregulation of vimentin35. Notably, although SV40-LT gene copy numbers progressively increased during passaging (potentially due to puromycin-mediated positive cell enrichment), protein level did not increase in tandem with the gene level across successive generations, suggesting compensatory post-transcriptional regulation such as translational suppression or ubiquitin–proteasome degradation36. Furthermore, both F10 NBLT and F3–F50 NBLS lines exhibited preserved diploid karyotypes alongside sustained cytokeratin-18 and vimentin markers, confirming lineage fidelity despite immortalization. This phenotypic stability arises from multiple factors: the cytoplasmic localization of SV40-LT minimizes nuclear interference with differentiation-related genes, while cytoskeletal regulatory networks (e.g., the activator protien-1 (AP-1) pathway) mediate cytokeratin maintenance of original cellular characteristics37. Collectively, these findings demonstrate the capacity of immortalization tools to preserve native cellular properties while overcoming replicative senescence38.

Research indicates that hTERT and SV40-LT gene transfection exhibit distinct regulatory effects on cell proliferation and immortalization. Lentivirus-mediated hTERT transfection activates telomerase activity, reduces survival rates and prolongs doubling times in NBLT cells compared to untransfected counterparts, with elevated linear growth curves and apoptosis rates suggesting genomic instability-induced suppression of long-term growth39. In contrast, SV40-LT-transfected F3–F50 NBLS cells maintain S-shaped growth kinetics, viability, cell cycle distribution (G1/S/G2 phase ratios), and passage stability comparable to primary cells (P > 0.05), confirming that SV40-LT antigen sustains proliferative capacity. Mechanistically, hTERT exhibits cell type-dependent functionality: its expression knockdown via RNA interference induces apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia cells (HL-60), while prolonged overexpression in Schwann cells triggers cell cycle arrest40. Conversely, SV40-LT activates proliferation via the phosphorylation-mediated regulation of key cyclins (e.g., p21 and Cyclin D1) and the activation of apoptosis-resistance pathways39. These molecular divergences highlight hTERT’s suitability for models requiring precise telomere modulation, whereas SV40-LT demonstrates superior efficacy in establishing immortalized cell lines, providing critical strategic insights for tumor therapeutic target screening and stem cell engineering applications.

Our results showed that BVDV effectively infected both dzo renal cells and SV40-LT-immortalized NBLS cells, with the latter exhibiting significantly higher TCID50 values, indicative of enhanced viral susceptibility in immortalized cells. This may stem from SV40-LT-mediated modulation of host cellular pathways to promote viral tropism41. For instance, SV40-LT-immortalized human cells demonstrate amplified Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) replication capacity, a mechanism potentially involving SV40-LT-driven cell cycle progression (e.g., G1/S phase transition acceleration) and suppression of antiviral defenses42. Substantiating this hypothesis, SV40-LT inhibits ATM kinase activity—a critical regulator of DNA damage repair—thereby attenuating host stress responses and elevating viral infectivity. Therefore, the enhanced NBLS cell susceptibility to BVDV possibly due to two reasons: (1) cell cycle reprogramming to create replication-favorable environments43, and (2) suppression of ATM/p53-dependent DNA repair and immune surveillance pathways44. These observations underscore SV40-LT’s broad-spectrum modification of host pathways as a unifying mechanism for increased viral vulnerability, ultimately resulting in higher TCID50 values compared to non-immortalized dzo renal cells.

Our study pioneers the successful immortalization of yak kidney cells via a lentiviral-SV40-LT system, addressing the critical gap in cellular models for plateau-dwelling livestock and providing a foundational tool for virology, vaccine development, and comparative medicine. In addition, the immortalized NBLS cell line demonstrates immediate utility, exemplified by its heightened sensitivity to BVDV. However, unresolved mechanistic complexities (e.g., cytoplasmic localization of SV40-LT conflicting with its canonical nuclear role) and safety concerns (e.g., untested tumorigenicity) necessitate systematic investigation. Future efforts should integrate multi-omics technologies and interdisciplinary collaboration to elucidate molecular mechanisms underlying immortalization, optimize biosafety profiles, and advance translational applications in preclinical research (e.g., antiviral drug screening) and industrial platforms (e.g., vaccine production). These endeavors will foster the convergence of veterinary and biomedical sciences, driving innovation and sustainable development in both fields.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- st:

-

Small T-antigen

- NBLT:

-

Dzo kidney cells transfected with hTERT

- NBLS:

-

Dzo kidney cells transfected with SV40-LT

- hTERT:

-

Human telomerase reverse transcriptase

- LT:

-

Large T antigen

- SV40:

-

Simian virus 40

- p53:

-

Tumor protein 53

- pRB:

-

Retinoblastoma protein

- BVDV:

-

Bovine viral diarrhea virus

- MDBK:

-

Madin–Darby canine kidney cell

- Co., Ltd:

-

Company limited

- EGFP:

-

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- LB:

-

Luria–bertani

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- UV:

-

Ultraviolet

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative PCR

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

- SYBR:

-

Synergetic binding reagent

- ACTB:

-

β-Actin

- PMSF:

-

Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride

- BCA:

-

Bicinchoninic acid assay

- PVDF:

-

Polyvinylidene fluoride

- HRP:

-

Horseradish peroxidase

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum albumin

- DAPI:

-

4ʹ,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- PDT:

-

Population doubling time

- CPE:

-

Cytopathic effects

- TCID 50:

-

50% Tissue culture infective dos

- SDs:

-

Standard deviations

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- STAT3:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- BCL-2:

-

B-cell lymphoma-2

References

Wang, L. et al. A hepadnavirus regulatory element enhances expression of a type 2 bovine viral diarrhea virus E2 protein from a bovine herpesvirus 1 vector. J. Virol. 77(16), 8775–8782 (2003).

Wang, Z. et al. Induction of robust and specific humoral and cellular immune responses by bovine viral diarrhea virus virus-like particles (BVDV-VLPs) engineered with baculovirus expression vector system. Vaccines (Basel) 9(4), 350 (2021).

Takenouchi, T. et al. Establishment and characterization of the immortalized porcine lung-derived mononuclear phagocyte cell line. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 1058124 (2022).

Shay, J. W. & Wright, W. E. Telomeres and telomerase: three decades of progress. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20(5), 299–309 (2019).

Maqsood, M. I. et al. Immortality of cell lines: challenges and advantages of establishment. Cell Biol. Int. 37(10), 1038–1045 (2013).

Ben-David, U. et al. Patient-derived xenografts undergo mouse-specific tumor evolution. Nat. Genet. 49(11), 1567–1575 (2017).

Ben-David, U. et al. Genetic and transcriptional evolution alters cancer cell line drug response. Nature 560(7718), 325–330 (2018).

Hughes, P. et al. The costs of using unauthenticated, over-passaged cell lines: how much more data do we need?. Biotechniques 43(5), 575 (2007).

Dos Santos, A. et al. Generation of functional immortalized human corneal stromal stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(21), 13399 (2022).

Chen, H. et al. Construction and identification of an immortalized rat intestinal smooth muscle cell line. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 34(8), e14359 (2022).

Cui, Y. et al. Expression analysis of molecular chaperones Hsp70 and Hsp90 on development and metabolism of different organs and testis in Cattle (Cattle-yak and Yak). Metabolites 12(11), 1114 (2022).

Wan, R. D. et al. Identification of candidate genes related to hybrid sterility by genomic structural variation and transcriptome analyses in cattle-yak. J. Dairy Sci. 108(1), 679–693 (2025).

Pengyu, Z. et al. Study on the mineral content of Yak Milk and Cattle-Yak Milk in Qinghai Province. China Dairy. 11, 85–90 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Highly pathogenic bovine viral diarrhea virus BJ-11 unveils genetic evolution related to virulence in calves. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1540358 (2024).

Wei, M. et al. Design and assessment of two broad-spectrum multi-epitope vaccine candidates against bovine viral diarrhea virus based on the E0 or E2 envelope glycoprotein. Vet. J. 309, 106296 (2025).

Koethe, S. et al. Bungowannah pestivirus chimeras as novel double marker vaccine strategy against bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vaccines (Basel) 10(1), 88 (2022).

Wu, S. X. et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals dysregulated gene expression networks in Sertoli cells of cattle-yak hybrids. Theriogenology 203, 33–42 (2023).

Chi, Y., Zhang, S. & Ji, S. Delivery of a hepatitis C virus vaccine encoding NS3 linked to the MHC class II chaperone protein invariant chain using bacterial ghosts. Biomedicines 12(3), 525 (2024).

Rashid, M. I. et al. Simple and efficient differentiation of human iPSCs into contractible skeletal muscles for muscular disease modeling. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 8146 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Establishment and characterization of a novel immortalized human aortic valve interstitial cell line. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 10917 (2025).

Zaharieva, M. M. et al. Photodynamic inactivation of bovine coronavirus with the photosensitizer toluidine blue O. Viruses 16(1), 48 (2023).

Yan, B. et al. Cryopreserved umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells show comparable effects to un-cryopreserved cells in treating osteoarthritis. Cell Transplant. 34, 9636897241297632 (2025).

Brezinger-Dayan, K. et al. Impact of cryopreservation on CAR T production and clinical response. Front. Oncol. 12, 1024362 (2022).

Funnell, T. et al. Single-cell genomic variation induced by mutational processes in cancer. Nature 612(7938), 106–115 (2022).

Grigorov, B. et al. Rapid titration of measles and other viruses: optimization with determination of replication cycle length. PLoS ONE 6(9), e24135 (2011).

Radzevičiūtė-Valčiukė, E. et al. Effects of buffer composition and plasmid toxicity on electroporation-based non-viral gene delivery in mammalian cells using bursts of nanosecond and microsecond pulses. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 12, 1430637 (2024).

Chernousova, S. & Epple, M. Live-cell imaging to compare the transfection and gene silencing efficiency of calcium phosphate nanoparticles and a liposomal transfection agent. Gene Ther. 24(5), 282–289 (2017).

Liang, R. et al. The role of NLRP3 inflammasome in aging and age-related diseases. Immun. Ageing 21(1), 14 (2024).

Jorgensen, I., Rayamajhi, M. & Miao, E. A. Programmed cell death as a defence against infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17(3), 151–164 (2017).

Wilson, K. A., Chateau, M. L. & Porteus, M. H. Design and development of artificial zinc finger transcription factors and zinc finger nucleases to the hTERT locus. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2(4), e87 (2013).

Chen, Y. et al. Characterization and establishment of an immortalized rabbit melanocyte cell line using the SV40 large T antigen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(19), 4874 (2019).

Lee, Y. et al. Development of immortalized feline respiratory epithelial cells in an air-liquid-interface culture system for feline herpesvirus-1 study. Virus Res. 326, 199063 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Immortalization of human normal and NF1 neurofibroma Schwann cells. Lab Invest. 96(10), 1105–1115 (2016).

Sun, M., Chen, X. & Yang, Z. Single cell mass spectrometry studies reveal metabolomic features and potential mechanisms of drug-resistant cancer cell lines. Anal. Chim. Acta 1206, 339761 (2022).

Bulle, A. et al. Gemcitabine induces Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in patient-derived pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma xenografts. Am. J. Transl. Res. 11(2), 765–779 (2019).

Mahon, M. J. Vectors bicistronically linking a gene of interest to the SV40 large T antigen in combination with the SV40 origin of replication enhance transient protein expression and luciferase reporter activity. Biotechniques 51(2), 119–128 (2011).

Zhong, C. Y. et al. MAPK/AP-1 signal pathway in tobacco smoke-induced cell proliferation and squamous metaplasia in the lungs of rats. Carcinogenesis 26(12), 2187–2195 (2005).

Maiques, O. et al. Matrix mechano-sensing at the invasive front induces a cytoskeletal and transcriptional memory supporting metastasis. Nat. Commun. 16(1), 1394 (2025).

Carbone, M., Rudzinski, J. & Bocchetta, M. High throughput testing of the SV40 Large T antigen binding to cellular p53 identifies putative drugs for the treatment of SV40-related cancers. Virology 315(2), 409–414 (2003).

Mark Welch, D. B. et al. Transcriptomes reflect the phenotypes of undifferentiated, granulocyte and macrophage forms of HL-60/S4 cells. Nucleus 8(2), 222–237 (2017).

Rohaly, G. et al. Simian virus 40 activates ATR-Delta p53 signaling to override cell cycle and DNA replication control. J. Virol. 84(20), 10727–10747 (2010).

Andrei, G. et al. Insights into the mechanism of action of cidofovir and other acyclic nucleoside phosphonates against polyoma- and papillomaviruses and non-viral induced neoplasia. Antiviral Res. 114, 21–46 (2015).

Cho, H. J., Park, S. G. Regulation of Hepatitis B virus cccDNA by metabolic pathways. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. (2025).

Kwok, M. et al. Targeting the p53 pathway in CLL: State of the art and future perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 13(18), 4681 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Ling Tian, Shuwu Chen, Jiachen Shi, and Shouqin Guo for their assistance in the laboratory.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chengguan District Science and Technology Talents Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project (No. 2023RCCX0002), the Technology Project of Gansu Province (No. 23YFFA0071), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 31920250002, No. 31920250125-01), and the 2024 Laboratory Open Projects of Northwest Minzu University (SYSKF-2024096).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L.: Methodology; formal analysis; writing—original draft and editing; C.X.: Methodology; J.W.: Data curation; N.S.: Resources; Z.M.: Resources; J.Z.: Conceptualization; J.C.: Investigation; Y.L.: Conceptualization; supervision; Z.Q.: Conceptualization; validation; writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, W., Xu, C., Wang, J. et al. Establishment and evaluation of an immortalized dzo kidney cell line. Sci Rep 15, 19020 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03997-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03997-3