Abstract

Carotid artery stenosis (CAS) is a significant health problem associated with poor cerebral perfusion, which might negatively affect patients’ psychological, physical, and cognitive health status. This study aimed to examined the relationship between CAS, cognitive status, and quality of life (QoL) among patients with CAS. A cross-sectional study was recruited a convenience sample of 140 adults (≥ 18 years) diagnosed via Doppler ultrasound with CAS of ≥ 10% severity from two tertiary hospitals in Jordan. Exclusion criteria included patients who had undergone CAS revascularization procedures and those with confirmed psychiatric disorders. Data was collected using three sections; demographic data, the World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF, and the mini-mental state examination tools. About 56.6% of the patients had moderate-severe CAS, and 87.1% had moderate-severe cognitive impairment. A significant association was observed between CAS severity and cognitive impairment (χ2 = 33.91, p < 0.001). Notably, 66% of patients with mild CAS exhibited moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment, rising to 71.3% in those with moderate-to-severe CAS. The overall patents’ QoL was poor while the highest mean was for psychological domain (58.86 ± SD = 16.15), and the lowest mean was for physical domain (45.46 ± SD = 19.62). There was a significant impact of the level of cognitive impairment on physical health [F (138) = 5.31, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.072], psychological health [F (138) = 7.05, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.093], and total QoL score [F (138) = 4.59, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.063]. The hierarchical regression revealed that cognitive status does significantly affect QoL, with severe cognitive impairment being associated with worse QoL. After controlling for sociodemographic variables, severe CAS (β = − 0.273, p = 0.015) and severe cognitive impairment (β = − 0.291, p = 0.007) were associated with poor QoL. Patients with CAS exhibited moderate cognitive impairment and reduced QoL, particularly in psychological and social domains. Integrating routine cognitive assessments into clinical evaluations is critical to guide holistic care addressing both vascular and cognitive health. Further interventions are required to reduce the potential for cognitive decline while also enhancing patients’ QoL, particularly by improving emotional well-being, daily functioning, and social engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carotid artery stenosis (CAS) is a major vascular condition characterized by the progressive narrowing of the carotid arteries due to atherosclerosis1,2. This narrowing compromises cerebral blood flow and increases the risk of stroke, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and other cerebrovascular events3,4. While CAS is widely recognized for its impact on cardiovascular and neurological outcomes5, emerging evidence suggests that it may also contribute to cognitive decline, even before overt cerebrovascular events occur6,7. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion and microembolization; which commonly associated with CAS; have been implicated in cognitive dysfunction, raising concerns about its potential impact on QoL among affected individuals6,7,8.

Quality of life is a multidimensional concept encompassing physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and environmental factors. Research suggests that cognitive impairment may negatively affect various aspects of daily living, including autonomy, mental health, and overall life satisfaction7. Several studies have explored the link between CAS and cognitive impairment, particularly in patients with severe stenosis (≥ 70%), demonstrating that significant carotid artery calcification is associated with measurable declines in cognitive function9,10. However, most of these studies have focused on cognitive changes following revascularization procedures, such as carotid endarterectomy or stenting, with limited research on the cognitive and QoL burden in pre-surgical CAS patients6,8,10,11,12,13.

Understanding the cognitive and QoL implications of CAS beside other co-morbidities such as hypertension and diabetes is particularly relevant in populations with a high burden of cardiovascular diseases1,14,15. In Jordan, where chronic illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are prevalent, CAS is likely a significant yet underexplored contributor to cognitive impairment and diminished QoL16,17,18,19,20. Despite the growing recognition of the importance of cognitive function in vascular diseases9,21,22,23, studies specifically addressing the relationship between CAS and QoL in Jordan remain limited. Given the complex interplay between cognitive status and various QoL domains, there is a need for research that examines how cognitive impairment affects the daily lives and well-being of CAS patients, particularly before surgical intervention. Specifically, in Jordan as there a substantial proportion of Jordanian patients contend with chronic illnesses and the elderly often present with comorbidities24,25 which could be contribute to the observed high percentage of CAS. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between CAS, cognitive status, and QoL among pre-surgical patients with CAS.

Method

Design

Analytical cross-sectional design was utilized.

Setting

The study was conducted in two major Jordanian hospitals: one public and one military. The public hospital has a total capacity of 1101 beds across four centers covering 35% of Jordanian population, including a specialized cardiac center with 110 beds with an annual admittance rate of 25,000 patients26. Similarly, the military hospital has 1414 beds distributed among nine centers covering 27% of Jordanian population with an annual admittance rate of 25,000 patients and dedicated cardiac center housing 130 beds. Both hospitals provide comprehensive cardiac and vascular care for inpatients and outpatients, offering multidisciplinary services for CAS patients, including diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up within internal medicine and cardiology units27.

Sample and sampling

A convenience sampling method was employed to recruit participants due to feasibility constraints, including limited access to a broader patient population and logistical challenges in implementing a probabilistic sampling approach such as stratified random sampling. While convenience sampling is susceptible to selection bias and limits the generalizability of findings, it was necessitated by the limited availability of eligible patients and the need for timely data collection in clinical settings.

The sample size was determined a priori using G*Power 3.1 software for a one-way ANOVA (fixed effects, omnibus) test. Parameters were set as follows: effect size f = 0.3, alpha = 0.05, and power = 0.80 (two-tailed). The effect size of 0.3 was selected based on Cohen’s conventions for a moderate effect size and supported by previous studies reporting moderate associations between CAS severity and cognitive decline10,28,29. Determine the value of alpha at 0.05 and power at 0.80 aligns with standard statistical practice to minimize Type I and Type II errors in clinical research30. This calculation yielded a required minimum of 111 participants. Accounting for a 10% attrition rate, the final calculated sample size was 122 patients. Ultimately, 140 participants were recruited to enhance robustness.

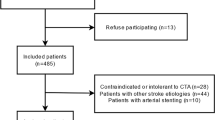

Inclusion criteria comprised adults aged ≥ 18 years with CAS confirmed by Doppler ultrasound, defined as ≥ 10% stenosis in the internal carotid artery (unilateral or bilateral) according the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) criteria with no upper age limit was applied. The exclusion criteria were (1) patients who underwent carotid revascularization (e.g., endarterectomy, stenting) within the past 6 months were excluded to minimize confounding effects from acute post-procedural recovery or transient cognitive changes associated with surgery (MRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial Collaborative31,32. (2) Patients with a documented history of any psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder with psychotic features, were excluded. These diagnoses were determined based on medical records and physician documentation.

Measuring CAS

Various diagnostic methods for CAS include magnetic resonance angiography, computed tomography angiography, and digital subtraction angiography. However, carotid Doppler ultrasound remains the most accessible, cost-effective, and non-invasive diagnostic tool for initial screening and monitoring29. Carotid Doppler ultrasound assesses stenosis severity by measuring blood flow velocity changes, which correlate with the degree of narrowing in the carotid artery. Peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end-diastolic velocity (EDV) are key parameters used to estimate stenosis severity, with higher velocities indicating more significant narrowing.

The direct measurement of carotid stenosis via Doppler ultrasound provides a straightforward, rapid, and reliable approach30. Unlike methods requiring ratio calculations, such as the NASCET (North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial) method, direct ultrasound measures reduce variability arising from differences in distal internal carotid artery size among patients. Additionally, Doppler ultrasound allows for the classification of carotid stenosis severity, with the NASCET-style ratio categorizing stenosis as mild (< 59%), moderate (50–69%) or severe (≥ 70%)33,34.

Instruments

In addition to the demographic questionnaire, two tools were used to collect data.

World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF)

The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire includes 26 questions of four domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environmental health. The first two questions were related to the overall QoL. The first domain was about physical health and included seven items (3, 4, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18). The second domain is about psychological health and includes six items (5, 6, 7, 11, 19, 26). The third domain was about social relationships, including three questions (items 20, 21, 22). The Fourth domain was about environmental health, including eight items (8, 9, 12, 13, 14, 23, 24, 25)35. All items were asked participants to report their experiences in the last 2 weeks to capture recent physical, psychological impacts of CAS on their QoL. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Each item has scored from 1 denoted the minimum effects to 5 denoted the maximum effects on a response scale. The result of WHOQOL-BREF ranged from 4 to 20, and the domain scores were calculated by multiplying the mean domain score by a factor of 436. The possible total score of WHOQOL-BREF ranged from 26 to 130; the higher total scores reflected a higher QoL. For the four domains of QoL, physical health has a raw score between 7 and 35; psychological health has a raw score between 6 and 30; social relationships have a raw score between 3 and 15; and environmental health has a raw score between 8 and 40. Furthermore, a transformed score for QoL ranged between 0 and 100 was used, with lower transformed scores revealed a poor QoL. This questionnaire is available in the Arabic language which validated in various diseases with a Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.7 to 09137,38,39. In the current study, reliability was 0.86.

The mini-mental state examination (MMSE)

It is a comprehensive tool that systematically evaluates mental status through 11 questions assessing five cognitive functions. These functions include orientation to time (year, month, day, date, and season), orientation to place (country, town, state, hospital, and floor), registration of three given objects, attention, and calculation by backward spelling or counting from 7 to 1, recall of the earlier three objects, language skills encompassing various tasks like naming objects, repeating phrases, following commands, writing a sentence, and copying a picture. One point was assigned for each correct answer. Scores ranged from 0 to 30, with cognitive impairment defined as an MMSE score ≤ 23. The MMSE score categorized into no impairment (25–30), mild/moderate impairment (11–24), and severe impairment (0–10)40. The MMSE, created in 1975, is extensively validated and utilized in research and clinical settings. It effectively discerns individuals with cognitive impairment from those without and is instrumental in monitoring changes in cognitive status. This questionnaire is available in Arabic language and has been validated in various countries, with a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.71 to 0.8241,42,43,44. In the current study, reliability was 0.75. Use of the MMSE-Arabic version in this study was authorized through a licensing agreement with Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. (PAR), which holds the exclusive publication and licensing rights to the MMSE.

Data collection

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan and the selected hospitals. After obtaining the approval, the researcher met with the head nurses at each location to explain the study’s purpose and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A list of eligible patients was requested from the administrative unit of each hospital’s interventional radiology departments, cardiovascular clinics, and vascular departments to determine when the patients had appointments. The intended participants were then informed of the study’s purpose and all related ethical concerns. The names and appointments of in-patients and outpatients with CAS were taken in the vascular clinics and interventional radiology departments. The researcher interviewed outpatients upon arrival, and if they agreed to participate in the study, they were informed of all the details related to the purpose of the study. A written consent form was signed, and the participants filled out the questionnaire while waiting for the physician. In the case of in-patients, the researcher interviewed them in their rooms after completing the Doppler ultrasound. These patients were informed about the study’s purpose and permitted to complete the questionnaire while waiting for the ultrasound. All patients were requested to complete the questionnaire using two tools. The first tool measured the patient’s QoL, which they could fill out independently. The second tool measured the patient’s mental state, which the researcher completed by asking them questions and writing their answers verbatim.

A total of 185 patients were approached and provided with questionnaires. Of these, 45 questionnaires were excluded due to incomplete responses, resulting in a final sample of 140 patients (response rate was 75.7%). The incomplete responses were attributed to feeling fatigue (n = 18), or preparing for carotid stenting (n = 23) or endarterectomy (n = 4), which limited their ability to complete the questionnaire. No incentives were offered for participation, and patients completed the survey voluntarily. Finally, the patients were thanked for their cooperation and participation. If patients were unable to read or write, they were initially assisted by a family member or a researcher. However, all patients who required assistance ultimately incomplete the survey responses due to fatigue (n = 18) and they were excluded from the analysis.

Data analysis

Analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. Descriptive statistics were employed for categorical variables, including frequency, percentages, mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum. The Pearson correlation test was used to examine the relationship between MMSE scores (independent variable) and total QoL scores (dependent variable). To further analyze the impact of different levels of cognitive status on QoL, a one-way ANOVA was conducted, with cognitive status categorized into mild, moderate, and severe as the independent variable and total QoL score as the dependent variable. Similarly, a separate one-way ANOVA was performed to compare differences in total QoL scores across different levels of CAS severity. Post-hoc Bonferroni tests were applied to identify specific group differences when ANOVA results were significant. Chi-square test was used to compare the frequency distribution between different levels of cognitive status and the severity of CAS to identify potential associations between these categorical variables. Multivariate analysis was performed using linear regression to assess the effect of cognitive status and CAS severity on QoL while controlling for sociodemographic variables. The continuous variables (e.g. total QoL) were normally distributed (shaper test > 0.05). The statistical significance was determined at a p value of < 0.05.

Result

The study included participants with a mean age of 61.72 years (± SD = 12.27), ranging from 26 to 85 years. Most patients were male (59.3%), and all participants were married. Most participants had up to secondary level education (51.4%) and when they asked to self-report whether they have sufficient household income (> 168 JOD ≈ 237$/person/month) or insufficient household income (≤ 168 JOD ≈ 237$/person/month) as the sufficient household income in Jordan is defined as an income greater than 168 JOD (approximately 237 USD) per person per month (46). Most of them (52.1%) indicated that they had insufficient household income. All participants had chronic illnesses, with the majority have health insurance coverage. The most common comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), and transient ischemic attack (TIA) (36.9%), followed by hypertension and cerebrovascular accident (CVA) (23.8%) (Table 1).

The number of patients who had mild CAS was 53 (43.4%) while the most of them had moderate-severe CAS (56.6%). The mean of MMSE score was 16.2 (± SD = 3.46). According to MMSE classification scores, most patients (87.1%) had moderate-severe risk for cognitive impairment. A significant association was observed between CAS severity and cognitive impairment scores (χ2 = 33.91, p < 0.001). Notably, 66% of patients with mild CAS exhibited moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment, rising to 71.3% in those with moderate-to-severe CAS (Table 2).

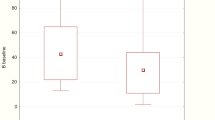

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics for the four domains of QoL. The highest mean is for psychological health (58.86 ± SD = 16.15), and the lowest mean is for physical health (45.46 ± SD = 19.62). The mean score for the total QoL is (52.91 ± SD = 13.97) reflecting that our patients had poor QoL, where the minimum score is (22.32%) and the maximum score is (91.41%) (Table 3).

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the impact of cognitive impairment on QoL at four domain scores and the total QoL score for mild, moderate, and severe cognitive impairment. The results showed a significant effect of the level of cognitive impairment on the physical health [F (138) = 5.31, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.072], psychological health [F (138) = 7.05, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.093], and total QoL score [F (138) = 4.59, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.063]. However, there were no significant effects on the level of cognitive impairment in social relationships [F (138) = 2.27, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.032] and environmental health [F (138) = 1.54, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.022] (Table 4).

Post-hoc comparisons using the Bonferroni test showed mild cognitive impairment (M = 52.77 ± SD = 19.88) was significantly higher than severe cognitive impairment (M = 21.42 ± SD = 5.52). Furthermore, in the psychological subscale, the mean score for mild cognitive impairment (M = 59.25 ± SD = 11.21) was significantly higher than for severe cognitive impairment (M = 33.33 ± SD = 5.52). For the overall QoL score, the mean score for mild cognitive impairment (M = 56.19 ± SD = 13.99) was significantly higher than severe cognitive impairment (M = 35.56 ± SD = 5.50). However, there are no significant differences between other cognitive levels and QoL subscales (p < 0.05). Overall, severe cognitive impairment has a higher impact on poor physical, psychological, and overall QoL than mild cognitive impairment among patients with CAS. Additionally, the level of cognitive impairment does not significantly affect social relationships and environmental health (Table 4).

A hierarchical linear regression was conducted to analyze the effect of the cognitive status and level of CAS on total QoL with adjusting for sociodemographic variables. The first regression model consisted of participants’ age, gender, education level, income, and insurance coverage to predict QoL. While the second model level of CAS and cognitive status to predict QoL. The data met the assumption of independent errors (Durbin–Watson value = 1.74) and the normality of unstandardized residual (Shapiro–Wilk test p < 0.01). The overall regression for the first model predicted approximately the variance in total QoL (R2 = 0.220, F (5,134) = 7.556, p < 0.01). patients’ age, gender, having insurance, income and CAS predicted approximately 20% of the variance in total QoL. However, only the age, education level, and insurance coverage were significant predictor of total QoL. Older patients (β = − 0.291, p < 0.01), primary educational level (β = − 0.256, p = 0.01), and had no insurance (β = − 0.12, p = 0.001) were associated with poor QoL (Table 5).

In the model two, the factors predicted approximately 39% of the variance in QoL (R2 = 0.394, F (7,132) = 12.244, p < 0.01). Only the gender, education, insurance coverage, CAS severity, and cognitive status were significantly predicted cognitive status. Have no insurance coverage (β = − 0.173, p = 0.024), and severe CAS (β = − 0.273, p = 0.015), severe cognitive impairment (β = − 0.291, p = 0.007) were associated with poor QoL (Table 5).

Discussion

Our findings revealed that 87 (62.1%) of patients exhibited moderate to severe stenosis. These patients require urgent interventions to prevent further complications46. Our results revealed that most patients had moderate to severe risk for cognitive impairment. This finding aligned with previous literature indicating that increased CAS levels are associated with poor cognitive status24,48. However, while some studies suggest cognitive improvement following carotid revascularization, others report no significant change or even potential cognitive decline post-intervention12,47,48. The variation in findings could be relied on several factors such as differences in sample characteristics, follow-up duration, and assessment tools used to measure cognitive function. Future research should further explore these inconsistencies and identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from intervention.

Mechanistically, the observed relationship between cognitive impairment and QoL may be explained by neurovascular pathways. Chronic hypoperfusion due to carotid stenosis can lead to cerebral ischemia, affecting executive function, processing speed, and memory (6–8). Additionally, the interplay between vascular pathology and neuroinflammation could contribute to cognitive decline, which in turn impacts daily functioning and psychological well-being6,7,9. This warrants further investigation into potential biomarkers or neuroimaging studies to confirm the underlying mechanisms.

The current study revealed that CAS was associated with QoL, particularly in the psychological and social health domains. Previous studies have similarly reported decreased QoL and heightened psychological distress, including anxiety and depression, in patients with carotid stenosis6,7,49. While Piegza et al.23 reported that 12% of CAS patients had anxiety and 14% had depression, attributing poor QoL solely to these conditions oversimplifies the issue. Our study demonstrates that the impact of cognitive status on an individual’s QoL spans all domains, which was a positive correlation that means improving cognitive status leads to improvement in all domains of QoL. Poor cognitive status often necessitates assistance in daily living activities and can lead to emotional challenges like anxiety and depression50. QoL is a multidimensional construct influenced by physical disability, treatment burden, financial stress, and healthcare accessibility7,50. A more holistic approach to patient assessment and management is necessary to address these diverse contributors to QoL. Notably, the psychological impact may be link to vascular depression theories, which suggest that cerebrovascular dysfunction contributes to depressive symptoms due to disrupted front-subcortical circuits51.

The social health impact may stem from the reduced independence and mobility associated with cognitive decline and cardiovascular symptoms, which hinder social participation52. Although Jordanian culture promotes strong social support networks, these may not fully alleviate the negative psychological and social consequences of carotid stenosis. In Jordan, family and community ties play a crucial role in patient care, with relatives often taking on caregiving responsibilities and providing emotional and financial support53. However, the burden of caregiving can lead to stress and fatigue among family members, potentially diminishing the quality of support received by the patient54,55. Additionally, social stigma surrounding chronic illness and cognitive impairment may discourage patients from openly discussing their struggles, further exacerbating psychological distress56. Future qualitative research could provide deeper insights into patient experiences within this sociocultural context, exploring how traditional support systems interact with the challenges posed by carotid stenosis and cognitive decline.

In contrast to the broad claim that cognitive impairment affects all domains of QoL, it is important to recognize that our study establishes only an association rather than causation. QoL is influenced by multiple factors, including age, socioeconomic status, pre-existing mental health conditions, and comorbidities19,36,57. These confounding variables may partially explain the observed relationship between cognitive function and QoL. In the Jordanian context, socioeconomic disparities play a significant role in healthcare accessibility, with patients from lower-income backgrounds often facing barriers to timely diagnosis and intervention45,56,58. Additionally, variations in education levels may influence health literacy, affecting how patients perceive and manage their cognitive symptoms16,59,60. Mental health stigma remains prevalent in Jordan, potentially discouraging individuals from seeking psychological support, which may further impact QoL55. Given these considerations, future research should employ longitudinal designs and adjust for these confounding factors to better understand the complex interplay between cognitive impairment and QoL in Jordanian patients with carotid stenosis. Also, clinicians should adopt a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to addressing cognitive, psychological, and social challenges in this patient population.

Implication for clinical practice, research, and education

The findings underscore the necessity of integrating cognitive health assessments into routine clinical care for CAS patients, particularly through standardized tools like MoCA or MMSE during pre-intervention evaluations. Early identification of cognitive impairment can guide personalized interventions, such as cognitive rehabilitation and vascular risk management, to preserve function and improve QoL. Clinicians (nurses and physicians) should adopt interdisciplinary care models that bridge vascular and cognitive health, fostering collaboration between neurologists, cardiologists, and neuropsychologists. Concurrently, research should prioritize elucidating mechanisms linking CAS to cognitive decline (e.g., hypoperfusion) and evaluate therapies targeting these pathways. Longitudinal studies tracking post-revascularization cognitive trajectories are also critical to refine rehabilitation strategies.

For education, CAS-related cognitive health modules must be embedded into medical curricula, with continuing professional development workshops to enhance clinicians’ competency in interpreting assessments and addressing patient-reported outcomes like autonomy and psychological well-being. Policymakers must mandate cognitive screening in CAS management guidelines and allocate resources for community-based early monitoring programs to mitigate long-term disability costs. A unified, multi-sectoral approach including clinical practice, research, education, and policy; is essential to address the dual burden of vascular and cognitive morbidity in CAS, ultimately improving patient outcomes and reducing societal impact.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The use of convenience sampling may have introduced selection bias, potentially leading to an overrepresentation of patients with better functional status or healthcare access. Additionally, cognitive function was assessed using validated scales, but the potential for reporting bias and ceiling effects in these tools should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional nature of our study prevents us from drawing conclusions about changes in cognitive function or QoL over time. Future research should incorporate longitudinal designs and objective neuroimaging measures to better understand these relationships.

Conclusion

Patients with CAS in this study exhibited moderate cognitive impairment and poor QoL, particularly in psychological and social domains. These findings underscore the necessity of incorporating routine cognitive assessments into clinical management to identify at-risk individuals early. Given the potential impact of cognitive impairment on patients’ functional independence and emotional well-being, future research should explore targeted interventions, such as cognitive training programs and vascular health optimization strategies, to mitigate cognitive decline. Additionally, longitudinal studies are needed to assess the long-term effects of carotid revascularization on cognitive function and QoL. Policymakers should consider integrating cognitive screenings into standard care protocols for patients with carotid artery disease to improve clinical outcomes and reduce healthcare burdens.

Data availability

All data that were analyzed during this study are included in this article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Change history

10 September 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: Majdi Alzoubi was incorrectly affiliated. The correct Information now accompanies the original Article.

References

Santos-Neto, P. J. et al. Association of carotid plaques and common carotid intima-media thickness with modifiable cardiovascular risk factors. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 30(5), 105671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105671 (2021).

Chou, C. L. et al. Segment-specific prevalence of carotid artery plaque and stenosis in middle-aged adults and elders in Taiwan: A community-based study. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 118(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2018.01.009 (2019).

Adhikary, D. et al. Prevalence of carotid artery stenosis in ischaemic heart disease patients in Bangladesh. SAGE Open Med. 7, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312119830838 (2019).

Ranjan, R., Adhikary, D., Das, D. & Adhikary, A. B. Prevalence and risk factors analysis of carotid stenosis among ischaemic heart diseases patient in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 15, 3325–3331 (2022).

Sulženko, J. & Pieniazek, P. The cardiovascular risk of patients with carotid artery stenosis. Cor Vasa 60(1), e42–e48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crvasa.2017.09.006 (2018).

Pavol, M. A., Sundheim, K., Lazar, R. M., Festa, J. R. & Marshall, R. S. Cognition and quality of life in symptomatic carotid occlusion. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 28(8), 2250–2254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.05.007 (2019).

Aber, A., Howard, A., Woods, H. B., Jones, G. & Michaels, J. Impact of carotid artery stenosis on quality of life: A systematic review. Patient Patient Cent. Outcomes Res. 12, 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0337-1 (2019).

Pucite, E. et al. Changes in cognition, depression and quality of life after carotid stenosis treatment. Curr. Neurovasc. Res. 16(1), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567202616666190129153409 (2019).

Gao, H. L. et al. Effects of carotid artery stenting on cognitive impairment in patients with severe symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Medicine 101(37), e30605. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000030605 (2022).

Chu, Z., Cheng, L. & Tong, Q. Carotid artery calcification score and its association with cognitive impairment. Clin. Interv. Aging 14, 167–177. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S192586 (2019).

He, S. et al. Altered functional connectivity is related to impaired cognition in left unilateral asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis patients. BMC Neurol. 21, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-021-02385-4 (2021).

Lal, B. K. et al. Asymptomatic carotid stenosis is associated with cognitiveáimpairment. J. Vasc. Surg. 66(4), 1083–1092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2017.04.038 (2017).

Nickel, A. et al. Cortical thickness and cognitive performance in asymptomatic unilateral carotid artery stenosis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 19, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-019-1127-y (2019).

Neyazi, A. et al. Hypertension, depression, and health-related quality of life among hospitalized patients in Afghanistan. J. Hum. Hypertens. 38(6), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-024-00914-5 (2024).

Heck, D. & Jost, A. Carotid stenosis, stroke, and carotid artery revascularization. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 65, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2021.03.005 (2021).

Alkhawaldeh, A. et al. Assessment of cognitive impairment and related factors among elderly people in Jordan. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 29(1), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_169_22 (2024).

Alnaeem, M. M. & Ahmad, M. Constipation severity and quality of life among patients with cancer who received prophylactic laxatives: Quasi-experimental study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 23(10), 3473–3480. https://doi.org/10.31557/APJCP.2022.23.10.3473 (2022).

Almomani, F. M., McDowd, J. M., Bani-Issa, W. & Almomani, M. Health-related quality of life and physical, mental, and cognitive disabilities among nursing home residents in Jordan. Qual. Life Res. 23, 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0461-2 (2014).

Jarab, A. S., Almousa, A., Rababa’h, A. M., Mukattash, T. L. & Farha, R. A. Health-related quality of life and its associated factors among patients with angina in Jordan. Qual. Life Res. 29, 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02383-7 (2020).

Subih, M., Al-Kalaldeh, M., Salami, I., Al-Hadid, L. & Abu-Sharour, L. Predictors of uncertainty among postdischarge coronary artery bypass graft patients in Jordan. J. Vasc. Nurs. 36(2), 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvn.2017.11.001 (2018).

Gray, V. L. et al. Asymptomatic carotid stenosis is associated with mobility and cognitive dysfunction and heightens falls in older adults. J. Vasc. Surg. 71(6), 1930–1937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2019.09.020 (2020).

Peng, C., Burr, J. A. & Han, S. H. Cognitive function and cognitive decline among older rural Chinese adults: The roles of social support, pension benefits, and medical insurance. Aging Ment. Health 27(4), 771–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2022.2088693 (2023).

Piegza, M. et al. Cognitive functions and sense of coherence in patients with carotid artery stenosis—Preliminary report. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1237130. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1237130 (2023).

Almansour, I., Ahmad, M. & Alnaeem, M. Characteristics, mortality rates, and treatments received in last few days of life for patients dying in intensive care units: A multicenter study. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 37(10), 761–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120902976 (2020).

Bustami, M. et al. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among women in Jordan: A risk factor for developing chronic diseases. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 14, 1533–1541. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S313172 (2021).

Jordan Ministry of Health. Yearly Statistical Report. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.jo/ebv4.0/root_storage/ar/eb_list_page/report_2021.pdf. Accessed on 3 Nove 2022 (2021).

Hammad, E. A. et al. Hospital unit costs in Jordan: Insights from a country facing competing health demands and striving for universal health coverage. Heal. Econ. Rev. 12(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13561-022-00356-0 (2022).

Pucite, E., Krievina, I., Miglane, E., Erts, R. & Krievins, D. Influence of severe carotid stenosis on cognition, depressive symptoms and quality of life. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health CP EMH 13, 168. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901713010168 (2017).

Rerkasem, A. et al. Impact of arterial stiffness on health-related quality of life in older Thai adults with treated HIV infection: A multicenter cohort study. Qual. Life Res. 33(12), 3245–3257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03796-9 (2024).

Polit, D. F. & Beck, C. T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice (Google Books, 2017).

MACSTC Group. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 363(9420), 1491–1502. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16146-1 (2004).

Johansson, E., Gu, T. & Fox, A. J. Defining carotid near-occlusion with full collapse: A pooled analysis. Neuroradiology 64(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-021-02728-5 (2022).

Bartlett, E. S., Walters, T. D., Symons, S. P., Aviv, R. I. & Fox, A. J. Classification of carotid stenosis by millimeter CT angiography measures: Effects of prevalence and gender. Am. J. Neuroradiol. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A1210 (2008).

Bartlett, E. S., Walters, T. D., Symons, S. P. & Fox, A. J. Quantification of carotid stenosis on CT angiography. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 27(1), 13–19 (2006).

Nedjat, S., Montazeri, A., Holakouie, K., Mohammad, K. & Majdzadeh, R. Psychometric properties of the Iranian interview-administered version of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF): A population-based study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 8, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-61 (2008).

Gobbens, R. J. & Remmen, R. The effects of sociodemographic factors on quality of life among people aged 50 years or older are not unequivocal: Comparing SF-12, WHOQOL-BREF, and WHOQOL-OLD. Clin. Interv. Aging 14, 231–239. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S189560 (2019).

Almarabheh, A. et al. Validity and reliability of the WHOQOL-BREF in the measurement of the quality of life of sickle disease patients in Bahrain. Front. Psychol. 14, 1219576. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1219576 (2023).

Khoshhal, S. et al. Assessment of quality of life among parents of children with congenital heart disease using WHOQOL-BREF: A cross-sectional study from Northwest Saudi Arabia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 17, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1249-z (2019).

Ibrahim, D. H. M., Albakari, S. M., Abdelbasit, M. S. & Abdelsalam, H. A. Assessment of quality of life, anxiety, and depression via WHOQOL-BREF, and HADS among Egyptian patients on warfarin therapy: A cross-sectional study. Zagazig Univ. Med. J. 30(14), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.21608/zumj.2024.279308.3309 (2024).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12(3), 189–198 (1975).

Dahbour, S. S., Hamdan, M. Z. & Kittaneh, Y. I. Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores in healthy educated adult Jordanian population. Jordan Med. J. 45(4), 317–322 (2011).

Alshammari, S. A. et al. Assessing the cognitive status of older adults attending primary healthcare centers in Saudi Arabia using the mini-mental state examination. Saudi Med. J. 41(12), 1315. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2020.12.25576 (2020).

Rami, Y., Diouny, S., Kissani, N. & Yeou, M. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Moroccan version of the mini-mental state examination: A preliminary study. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 31(4), 595–600. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2022.2046583 (2024).

El-Hayeck, R. et al. An Arabic version of the mini-mental state examination for the Lebanese population: Reliability, validity, and normative data. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 71(2), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-1812 (2019).

World Bank. World Development Report 2024: Economic Growth in Middle Income Countries. [Available from: Jordan https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/jordan/overview: Development news, research, data (World Bank, 2024).

Mihindu, E. et al. Patients with moderate to severe strokes (NIHSS score> 10) undergoing urgent carotid interventions within 48 hours have worse functional outcomes. J. Vasc. Surg. 69(5), 1471–1481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2018.07.079 (2019).

Piegza, M. et al. Cognitive functions after carotid artery stenting—1-Year follow-up study. J. Clin. Med. 11(11), 3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11113019 (2022).

Sridharan, N. D., Asaadi, S., Thirumala, P. D. & Avgerinos, E. D. A systematic review of cognitive function after carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic patients. J. Vasc. Surg. 75(6), 2074–2085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2021.12.059 (2022).

Everts, R. et al. Cognitive and emotional effects of carotid stenosis. Swiss Med. Wkly. 144, w13970. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2014.13970 (2014).

Zhang, Y. & Fang, Q. Clinical study of stent forming for symptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis. Medicine 99(25), e20637. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000020637 (2020).

Aizenstein, H. J. et al. Vascular depression consensus report—A critical update. BMC Med. 14, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0720-5 (2016).

Mannoh, I., Hussien, M., Commodore-Mensah, Y. & Michos, E. D. Impact of social determinants of health on cardiovascular disease prevention. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 36(5), 572–579. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0000000000000893 (2021).

Gharaybeh, K. General socio-demographic characteristics of the Jordanian society: A study in social geography. Res. Hum. Soc. Sci. 4(1), 1–10 (2014).

Al-Daken, L. I. & Ahmad, M. M. Predictors of burden and quality of sleep among family caregivers of patients with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 26(11), 3967–3973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4287-x (2018).

Bahari, G. Caregiving burden, psychological distress, and individual characteristics among family members providing daily care to patients with chronic conditions. Perspect. Psychiatr Care 58(4), 2043–2049. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.13026 (2022).

Mosleh, S. M., Alja’afreh, M., Alnajar, M. K. & Subih, M. The prevalence and predictors of emotional distress and social difficulties among surviving cancer patients in Jordan. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 33, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2018.01.006 (2018).

Abdulrahim, S., Ajrouch, K. J. & Morrison, M. Hiding health problems: Culture and stigma. In Biopsychosocial Perspectives on Arab Americans: Culture, Development, and Health (eds Nassar, S. C. et al.) 75–94 (Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28360-4_5.

Al-Herz, A. et al. Accessibility to biologics and its impact on disease activity and quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Kuwait. Clin. Rheumatol. 40, 1759–1765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05444-2 (2021).

Alnaeem, M. M., Islaih, A., Hamaideh, S. H. & Nashwan, A. J. Using primary healthcare facilities and patients’ expectations about triage system: Patients’ perspective from multisite Jordanian hospitals. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 75, 101476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2024.101476 (2024).

Borda, M. G. et al. Educational level and its association with the domains of the Montreal cognitive assessment test. Aging Ment. Health 23(10), 1300–1306. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1488940 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R444) Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R444) Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alnaeem M, and Obeid A. performed the literature search, collected and interpreted the data. Suleiman K drafted the work and contributed to the writing of this manuscript. Al-Mugheed K., edited and drafted the final version of this manuscript. Amany ASA and Sally MFA. reviewed the final version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan [IRB number: 2023-2022/405/03] as well as by the Military hospital [TF3/1/professional ethics/1428] and Jordanian Ministry of Health [B/A/18631]. Before participation, patients provided consent after being informed that their involvement was voluntary and that all gathered information would be solely utilized for scientific purposes. Participants retained the right to withdraw from the study at any point without impacting their care or treatment negatively, and there was no financial benefit from them. Formal permission to use the MMSE-Arabic version was obtained from PAR (Supplementary file 1). All gathered information and completed questionnaires were stored in sealed envelopes within the researcher’s office to ensure confidentiality. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review at all sites.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after providing a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participants were assured of their voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw at any time without consequences. Additionally, they were encouraged to ask questions to ensure full understanding before giving consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alnaeem, M.M., Obeid, A., Suleiman, K. et al. Cognitive impairment and quality of life among patients with carotid artery stenosis in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 19639 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04004-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04004-5