Abstract

New antibacterial agents with novel actions are vital to treat drug-resistant bacterial infections. Silver and gold-based organometallic N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) complexes have emerged as promising candidates with notable antibacterial potential. Here, four new Ag(I)- and Au(I)-NHCcomplexes, 1a, 1b, and 2a, 2b, have been synthesized from the proligand 2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-2H-imidazo[1,5-α]pyridine-4-ium hexafluorophosphate and 1-methyl 2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-2H-imidazo[1,5-α]pyridine-4-ium hexafluorophosphate, respectively, and characterized using several spectroscopic techniques. All the NHC complexes 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b were revealed to have antimicrobial activity against ampicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus, ranging from 32 to 256 µg/mL. Complex 1b and 2b showed a MIC value of 64 and 32 µg/mL, respectively which is further reduced eightfolds when used in combination with ampicillin. The most potential NHC complex 2b is also efficiently able to eradicate S. aureus biofilms in the presence of ampicillin. Electron microscopy and molecular docking studies demonstrated significant cell membrane disruption accompanied by a marked depletion of the intracellular ATP pooland β-lactamase inhibition as major mechanisms of action against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus. Thus, thiophene-functionalized Ag(I) and Au(I)-NHC complexes could be developed as potential antibacterial agents to control drug-resistant bacteria and infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a severe global health threat, rendering common infections harder to treat and increasing mortality rates1. If unaddressed, AMR could lead to 10 million deaths annually by 2050, surpassing cancer-related fatalities. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) exemplifies the peril of antibiotic resistance, causing severe, often life-threatening infections. Its resilience against multiple antibiotics makes it a formidable challenge in conventional antibiotics. The development of a new antibacterial agent is crucial to effectively manage the threats of antibiotic resistance2,3,4.

Recently, antimicrobial properties of Ag(I) and Au(I) complexes, particularly against antibiotic-resistant pathogens are well documented5,6. The framework of Ag(I)-tazobactam exhibits enhanced activity against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Notably, these complexes demonstrated superior efficacy compared to tazobactam alone7. Recently, the combination of NHC-Ag(I) have beenreceiving specialattention for developing more potent antibacterial agents8,9,10. Among these, quinoline-based ligands stand out for their ability to form structurally diverse Ag(I) complexes with notable biological activity11. The novel study of Youngs and co-workers shows that alkanolN-functionalized silver-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes exhibit better antibacterial activity than currently available silver-based drugs12. Esarev et al. demonstrated that silver NHC halide complexes, particularly iodide-containing variants, exhibit strong antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria by targeting thioredoxin and glutathione reductases13. Among the various metal–NHC complexes investigated, pyrrole-NHC silver complexes exhibit potent antibacterial activity, particularly against Gram-negative bacteria14. The interest in using gold and its complexes dates back to ancient times, and it was an important part of alchemy in medieval Europe and the Renaissance when gold was an essential element in so-called aurum vitae treatments15. With the discovery of penicillin and its widespread production, the usefulness of gold as an antimicrobial diminished, bringing in the era of antibiotics in modern science and medicine16,17,18,19. Ongoing research into NHC-gold complexes has highlighted their potential in therapeutic, photonic, and catalytic applications20,21. TheAu(I)-NHC compound, has been identified as a potent bactericidal agent against Pseudomonas aeruginosa22. Investigations into its mechanism revealed that Au(I) disrupts bacterial membrane integrity, leading to cell death22. This disruption was evidenced by increased membrane permeability and morphological changes observed through electron microscopy22. Further study with pyrazine-functionalized Au(I)-NHC complexesdemonstrated their effectiveness against antibiotic-resistant human pathogens23. These complexes not only inhibited bacterial growth but also prevented biofilm formation by both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The proposed mechanism involves binding to peptidoglycan layers, resulting in cell wall damage and increased membrane permeability23. Gold(I) selenium N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) complexes have demonstrated superior antibacterial activity compared to auranofin against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria by targeting thioredoxinreductase, as reported by Chen et al24. Marine natural product-based NHC ligands, such as those from norzooanemonin, support the formation of Au(I) complexes with notable antibacterial potential25. Stenger and Özdemir et al. established monocarbeneAu(I) complexes of benzimidazolylidene inhibit the growth of S. aureus and Enterococcus faecalis in vitro but have no impact on Gram-negative bacteria26,27.

More recently, Ag(I)- and Au(I)- complexes of NHC ligands with lipophilic substituents with low oxidation states have shown better kinetic stability than the available silver-based drugs. This was due to reducing the σ-donation and improving the π-accepting nature of these ligands23,28. A review of published research suggests that the thiophene moiety has significantly piqued the interest of medicinal chemists and biochemists in organizing, planning, and implementing novel ideas for the discovery of new therapeutics. Thiophene and its derivatives are a significant type of compounds in the medical domain with various therapeutic potentials i.e. they adhere to nucleic acids and show anti-bacterial, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory properties29,30,31. According to recent SAR investigations, monocarbene gold complexes possess considerably enhanced antibacterial properties and TrxR inhibition relative to cationic dicarbene complexes32. In the present study, we have attempted for the synthesis of novel thiophene-functionalized NHC-Ag(I) and NHC-Au(I) complexes to combat the antibiotic-resistant bacteria. We have used an ampicillin-resistant S. aureus strain to check the efficacy of newly synthesized NHC complexes and also elucidate the respective crushing mechanism of action (Fig. 1).

Results and discussions

Synthesis

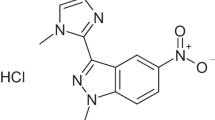

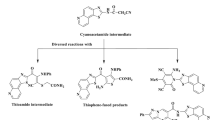

The imidazolium salt, 2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-2H-imidazo[1,5-α]pyridin-4-ium hexafluorophosphate(V) (1.HPF6) was synthesized by the cyclization reaction of the respective Schiff base (E)-N-(pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-1-(thiophen-2-yl)methanamine with paraformaldehyde, triethylorthofomate and 4(N) HCl as reported procedure33. By following a similar procedure 1-methyl 2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-2H-imidazo[1,5-α]pyridin-4-ium hexafluorophosphate(V) (2.HPF6) was prepared from the Schiff base (E)-N-((1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethylidene)-1-(thiophen-2-yl)methanamine. The silver complex 1a was prepared directly by overnight stirring of 1.HPF6 with Ag2O at ambient temperature in acetonitrile and isolated with 77% yield. Similarly, silver complex 2a was prepared from 2.HPF6 and Ag2O were obtained as 76.14% yield. The gold complexes 1b and 2b were obtained via the carbene-transfer reaction of the corresponding silver complexes 1a and 2a with (SMe2)AuCl in acetonitrile34 (as shown in Fig. 2). The complexes 1a, 1b, and 2a were identified by SCXRD. The ligands and complexes were also analyzed by using 1HNMR, 13C NMR, and elemental analysis.

In DMSO-d6 the 1H NMR spectrum of the ligand precursors, 2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-2H-imidazo[1,5-α]pyridin-4-ium hexafluorophosphate, 1.HPF6 displayed ten resonances comprising nine in thearomatic region assigned to imidazo[1,5-α]pyridine andthiophene ring protons and the distinctive singletemerging at 9.77 ppm specified to –NCHN– proton of the imidazolium ring (Figure S1). There was significant shifting of the signals in 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of the complexes. As predicted, after silver and gold coordination in 1a and 1b, the –NCHN– proton signal of 1.HPF6 disappeared (Figure S5, S7), which confirms the formation of Ag(I)-NHC, 1a and Au(I)-NHC, 1b. Again in 13C NMR spectra, the carbenic carbon signal appears at 172.32 and 174.81 ppm respectively for 1a and 1b (free procarbene 136.03 ppm) supporting the formation of complexes (Figure S2, S6 and S8). Similarly, the formation of proligand 1-methyl 2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-2H-imidazo[1,5-α]pyridin-4-ium hexafluorophosphate(V); 2.HPF6 was confirmed by the appearance of imidazolium singlet –NCHN– signal at δ = 9.59 ppm and methyl group signal at 2.62 ppm in 1H NMR (Figure S3) and the disappearance of –NCHN– signal and downfield shift of other aromatic proton signal confirms the formation of complexes 2a and 2b (Figure S9, S11). The maximum shifting of the carbenic carbon signal from 135.80 to 172.89 ppm (for complex 2a) and 174.07 ppm (for complex 2b) was also validated the formulations 2a and 2b (Figure S4, S10 and S12).

Single-crystal X-ray crystallography has been employed to determine the solid-state structures of 1a, 1b, and 2a. The crystallographic parameters were presented in Table S1, whereas bond parameters were listed in Tables S2 and S3. X-ray quality crystals were accomplished from the slow diffusion of diethyl ether into the saturated solution of the corresponding complexes in acetonitrile. The Ag(I)-NHC complex 1a (Fig. 3) was crystallized in the triclinic space group of P-1, whereas complex 2a (Fig. 4) was crystallized in the monoclinic space group of P21/c. Complex 1a had an asymmetric unit containing one and a half bis-carbene complex cation and one and a half hexafluorophosphate anion while a single bis-carbene complex cation and one hexafluorophosphate anion are present in the asymmetric unit of complex 2a. Around the silver(I) center, both the complexes exhibit a slightly deformed linear coordination geometry with the bond angles of 176.88(17)° [C(1)-Ag(1)-C(13)] and 176.42(13) [C(1)-Ag(1)-C(14)] for 1a and 2a, respectively. The internal ring angles at carbene carbon centers in both the complexes are 104.7(4)° [N(1)-C(1)-N(2)], 104.6(4)° [N(3)-C(13)-N(4)] and 103.9(3)° [N(1)-C(1)-N(2)], 104.1(3)° [N(3)-C(14)-N(4)], respectively for 1a and 2a and close to previously reported annulated systems35. The Ag-Ccarbene bond distances, Ag(1)-C(1) 2.092(4)Å and Ag(1)-C(13) 2.101(5)Å for 1a and Ag(1)-C(1) 2.087(3)Å and Ag(1)-C(14) 2.091(3)Å for 2a, which are less than the sum of the individual van der Waal radii of silver (1.72 Å) and carbon (1.70 Å), and are comparable with the reported complexes by our group36,37.

As described earlier the single crystals of 1b suitable for X-ray diffraction were grown by the diffusion of Et2O into acetonitrile solution of 1b. The crystal crystallized in the triclinic space group of P-1. The solid state structure of 1b revealed the bis-carbene connectivity which is similar to complex 1a. As observed in Figure 5, Au(I) adopts a linear geometry, Ccarbene-Au(I)-Ccarbene angle i.e. C(1)-Au(1)-C(13) 177.9(2)°. The Au-Ccarbene separations Au(1)-C(1) 2.017(5)Å and Au(1)-C(13) 2.018(6)Å, which were comparable with other gold(I)-NHC compounds39 reported by our group and less than sum of the van der Waal radii of Au (1.66 Å) and C (1.70 Å). In all three complexes, the solid-state stability is primarily stabilized by intermolecular π…π stacking interactions.

The UV-Vis absorption and emission spectra were recorded at room temperature for the proligands 1.HPF6 and 2.HPF6and for the complexes 1a, 1b, 2a and 2b in CH3CN (concentration cα., 1 × 10−5 M) were reported in Figure S12 and S13 respectively. The ligand precursors 1.HPF6 and 2.HPF6 were characterized by an absorption band at 230–300 nm which can be attributed to annulated imidazole based π–π* ligand-centered (LC) transitions. Metal coordination generated perturbations of these LC bands, which were generally slightly red-shifted in case of Ag(I) and Au(I) in comparison to those of the proligands which were assumed as ILCT, but in present complexes no additional metal-centered bands could be identified. Photoluminescence properties were checked at room temperature, the precursors and metal complexes are emissive and emission maxima (λmaxemission) around 361.49 nm (1.HPF6), 399.97 nm (2.HPF6), 373.45 nm (1a), 372.78 nm (1b), 382.38 nm (2a) and 378.42 nm (2b) (Figure S14) was observed after excitation at 276 nm (as shown in Table S4). The proligand likewise exhibits weak luminescence, but this intensity is enhanced with complexation, and in the case of Ag(I)-NHC highest intensity was found. The IR spectra of the ligands show characteristic peaks that shift upon complexation with Ag(I) and Au(I), indicating metal–carbene interactions. In 1.HPF6, the peaks at 763 cm−1 and 716 cm−1 shift to 733.28 cm−1 (1a) and 721 cm−1 (1b) due to changes in thiophene ring vibrations upon metal coordination. Additionally, the Au complex exhibits new peaks at 2919 cm−1 and 2847 cm−1, likely arising from C–H stretching modes activated by the stronger π-back bonding and relativistic effect (Figure S15). In the case of 2.HPF6, the IR spectrum shows peaks at 1450 cm−1 and 1342 cm−1, which shift to 1432 cm−1 and 1329 cm−1 in both Ag and Au complexes, indicating metal coordination affecting C=N and C–N stretching. Additionally, the peak at 774 cm−1 in the proligand shifts to 757 cm−1 in 2a and 761 cm−1 in 2b, suggesting changes in thiophene ring vibrations due to metal–carbene bonding (Figure S16).

Electrochemical studies

The cyclic voltammetry studies were performed in dry CH3CN with 0.1 M N(n-Bu)4PF6 as a supporting electrolyte to examine the oxidative-reductive nature of Au(I)-NHC complexes. A potential range of − 1.75 to + 1.75 V was applied to analyze the electrochemical behavior of Au(I)-NHC complex 1b and 2b. The cyclic voltammetric result of 1b and 2b scanning at 100 mV/s is shown in Figure S17 and Figure S18, respectively. There was one irreversible reduction peak, identified as R1, at − 1.33 V (− 1.34 V for 1b) assigned for the reduction of Au(I) to metallic Au(0), and the potential is comparable to similar systems reported earlier for Au(I)-NHC analogs38,39. Moreover, the Au(I)/Au(0) redox process became quasi-reversible and a re-oxidation wave (O1) appeared at − 0.34 V. A quick diffusion or breakdown of species electrogenerated during the R1 process may be indicated by the decrease in O1 at lower sweep rates. Upon further extending the potential window to + 1.75 V, a noticeable positive anodic peak denoted as O2 was observed at about 0.96 V for complex 2b (0.95 V for complex 1b). This results from the oxidative dissolution of Au(0), which would have accumulated on the electrode during the first reduction, to Au(I)40.

Antibacterial activity

NHC complexes showed activity against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus

Successful synthesis and characterization of desired NHC complexes, a primary antimicrobial test is performed using agar well diffusion assay. All four NHC complexes including Ag-NHC and Au-NHC (1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b) tested against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, respectively. The agar well diffusion assay demonstrated that synthesized complexes exhibited selective antibacterial activity, effectively inhibiting the growth of S. aureus but not the P. aeruginosa. The varying diameters of inhibition zones indicated differing efficacies among the complexes against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus, with Au-NHC complexes 1b and 2b showing the strongest antibacterial potency (Figure S19).

To further quantitate the antimicrobial potential of the synthesized complexes, MIC assay were performed which in agreement with the agar well diffusion assay and confirmed that Au-NHC complexes, 1b, and 2b have the lowest MIC values against S. aureus as, 64 and 32 μg/mL, respectively. On the other hand, Ag-NHC complexes (1a, and 2a) revealed to have MIC values as 256 and 128 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 6A). Overall, Au-NHC complex, 2b, confirmed to have most potent complex against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus (Table S5).

MIC determination of Ag(I)/Au(I)-NHC complexes against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus. (A) MIC determination of Ag(I)-NHC and Au(I)-NHC complexes. All the complexes were dissolved in DMSO. Untreated S. aureus cells were used as control. (B) MIC determination of Au(I)-NHC complexes in combination with ampicillin using growth inhibition assay. Untreated S. aureus cells and ampicillin alone were used as controls. All the experiments were performed three times independently in triplicates. Bars showed a standard deviation (SD) while statistical significance is considered acceptable when P < 0.05.

Au-NHC complexes able to eliminate ampicillin resistance of S. aureus

As the tested target strain of S. aureus was ampicillin-resistant, we were further interested in exploring the efficacy and mechanism of action of NHC complexes against this strain in combination with ampicillin. To check the synergistic action of NHC complexes and ampicillin, an agar well diffusion assay was performed followed by MIC determination using a growth inhibition assay. Interestingly, agar well diffusion assay revealed a synergistic action of Au-NHC complexes, 1b, and 2b in combination with ampicillin which seems enhanced in comparison to the activity of complexes when used alone (Figure S19). To further, validate the synergistic action of Au-NHC complexes with ampicillin, MIC values were determined quantitatively. Surprisingly, results showed an eight-fold reduction in MIC values of complexes 1b, and 2b as 8 and 4 μg/mL when compared to 64 and 32 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 6B). Thus, Au-NHC complexes, 1b, and 2b were able to kill ampicillin-resistant S. aureus more efficiently when used in combination with ampicillin while complex 2b found as most potent. This also indicates that Au-NHC complexes facilitate S. aureus to overcome ampicillin resistance via a specific mechanism other than their killing mechanism of action.

Au-NHC (2b) efficiently eradicates the biofilm of ampicillin-resistant S. aureus

Since the biofilm functions as a barrier of defense for the bacteria, its creation may lessen the potency of antibiotics against bacteria. In general, bacteria exploit the formation of biofilms as a survival tactic to sustain steady development under adverse environmental conditions41,42. As complex 2b was confirmed to have the most potent efficacy against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus, we were further curious to investigate its potential against S. aureus biofilms. A crystal violate assay was carried out to check the biofilm eradication potential of complex 2b, alone and in combination with ampicillin. Assay results revealed a reduction of approximately 25% in the presence of 4 μg/mL of 2b while about 95% of biofilm eradication is observed when 2b is present in combination 10 μg/mL of ampicillin (Fig. 7A). Complex 2b is confirmed to have potent biofilm eradication potential when used in combination with ampicillin.

Biofilm eradication and mechanism of action of Au(I)-NHC complexes against S. aureus. (A) Crystal violate assay of 2b in combination with ampicillin. Untreated S. aureus cells and 1% Triton X-100 are used as negative and positive controls, respectively. (B) ATP release determination from ampicillin-resistant S. aureus upon treatment with Au(I)-NHC complexes, 1b, and 2b. Untreated S. aureus cells were used as control. (C) SEM images of ampicillin-resistant S. aureus after 30 min of treatment with 2b alone. Untreated S. aureus cells were used as control (i). Bars showed a standard deviation (SD) while statistical significance is considered acceptable when P < 0.05.

Au-NHC complexes kill ampicillin-resistant S. aureus by disruption of membrane and ATP pool

Au-NHC complexes were further used to explore their mechanism of action against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus following ATP release assay and scanning electron microscopy study. If antibacterial action is associated with pore-formation or any kind of membrane disruption, the ATP pool also gets abolished and results in ATP release43. An ATP release assay is performed to check if the antibacterial activity of Au-NHC complexes is associated with membrane-specific mechanisms of action and ATP release. Interestingly, the resultsagreed with MIC experiments as complex 2b demonstrate more potent ATP reduction than complex 1b. Results confirmed about 80% of the decrease in ATP pool after one hour of treatment with complex 2b (32 μg/mL) when compared to untreated controls (Fig. 7B). It is indicating a membrane-specific mechanism of Au-NHC complexes to kill ampicillin-resistant S. aureus. Membrane disruption by the action of compound is further confirmed by scanning electron microscopy which clearly showed cell clumping, membrane disintegration, and cell number reduction when treated with 32 μg/mL of concentration for 30 min of treatment time, while the untreated cells were observed as round smooth, and symmetrically organized (Fig. 7C).

Au-NHC complexes are inhibiting β-lactamase

Au-NHC complexes are confirmed to have a membrane-specific mechanism of action against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus. More importantly, both 1b and 2b exhibited efficient activity in the presence of ampicillin. Similarly, 2b demonstrated efficient eradication of biofilms as well when used in combination with ampicillin. Overall, Au-NHC complexes make the ampicillin-resistant S. aureus sensitive to ampicillin by replenishing the resistance. Interestingly, the mechanism of synergistic action with ampicillin displayed by Au-NHC complexes remains unknown and is worth investigating. It is well known fact that ampicillin is a β-lactam antibiotic and β-lactamase is the key factor behind ampicillin resistance44. In consideration of this fact, it seems that Au-NHC complexes might inhibit the β-lactamase of ampicillin-resistant S. aureus and so make it more sensitive towards the combination of Au-NHC complexes and ampicillin. To check the interaction between β-lactamase of S. aureus and 2b, a molecular docking experiment is performed. Molecular docking results revealed a negative binding free energy score (− 124.76 kcal/mol). Complex 2b interacted with chain A of S. aureus β-lactamase where amino acid residues, Ser70, Tyr105, Asn132, Gln237, and Ile239 are specifically involved in the inhibition mechanism (Fig. 8). Overall, Au-NHC complexesmightbeinvolved in the inhibition of β-lactamase and replenish the S. aureus resistance towards ampicillin.

Molecular docking analysis of Au(I)-NHC complex, 2b with β-lactamase of S. aureus. Β-lactamase showed as a dusky yellow color solid structure while 2b showed as a stick. Interacting amino acids of β-lactamase with 2b are represented as colored sticks while interacting bonds are shown as colorful dotted lines.

Conclusions

The rapid emergence of antibiotic drug resistance and new infections is one of the greatest problems in clinical therapeutics. Many of the drug-resistant bacteria have already been classified on the urgent threat list, issued by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, USA45,46. There is an urgent need for new antimicrobials with novel mechanisms to combat rising antibiotic resistance. Present work identified novel Au(I)-NHC complexes with their strong antimicrobial potential against ampicillin-resistance S. Aureus. Mechanism studies revealed a membrane-specific killing by complex 2b via disrupting of ATP pool alongwith membrane disintegration (Fig. 9). Additionally, molecular docking analysis suggested Au-NHC complexes as β-lactamase inhibitors. Overall, Au-NHC complexes might have some potential for the development of new antibacterials to combat drug-resistant bacteria. Au-NHC complexes-based drugs might also be used in combination with existing antibiotics to replenish the existing antibiotic drug resistance.

Material and methods

Chemicals and antibiotics

The synthesis of proligands, 1.HPF6 and 2.HPF6 and the corresponding Ag(I) complexes (1a and 2a) and Au(I) complexes (1b and 2b) were prepared under an open atmosphere otherwise stated. Chemicals required and used in the synthesis of thiophene functionalized-NHC complexes were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, including, pyridine-2-carboxaldehyde, 2-acetyl pyridine, 2-thiophene methylamine, Ag2O, paraformaldehyde, KPF6, polylysine, sodium cacodylate, and glutaraldehyde. Acetonitrile (CH3CN), tetramethylsilane (TMS, C4H12Si), toluene, diethyl ether, DMSO, and HCl were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, India. Au(SMe2)Cl was prepared following the previously described method21. The proper drying agents were used to distill the solvents. TMS was used as an internal standard while recording NMR spectra on a Bruker (AC) 400 MHz FT-NMR spectrometer. A Shimadzu UV-1601 was used to analyze the UV–Vis spectra, and a Perkin Elmer spectrophotometer model LS55 was used to obtain fluorescence spectra. Cyclic voltammetry measurements were carried out with the use of CH Instruments, USA model CHI660C using dry acetonitrile solutions of the complexes that contained N(n-Bu)4PF6 (TBAP) as a supporting electrolyte. All the antibiotics for primary testing, including Ampicillin was purchased from HiMedia, India. A cork-borer set of different sizes to punch the wells on nutrient agar was purchased from Sigma, USA (Z165220).

Synthesis of 2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-2H-imidazo[1,5-α]pyridin-4-ium hexafluorophosphate(V); (1.HPF6)

The proligand 1.HPF6 was synthesized from a mixture of pyridine-2-carboxaldehyde (1500 mg, 14 mmol) and 2-thiophene methylamine (1585 mg, 14 mmol) in toluene which was stirred for 10 h at room temperature. Then crushed 91% paraformaldehydepowder (304 mg, 10.12 mmol) was added to the corresponding Schiff base (E)-N-(pyridin-2-yl)methylene)-1-(thiophen-2-yl)methanamine (2250 mg, 11.12 mmol) and stirring was continued for 18 h. After that, 5 mL of 4(N) HCl in diethyl ether was added slowly, which resulted in a rapid separation of layers. After separating the lower viscous yellowish layer, aqueous KPF6 was added and immediately white precipitation was observed. The precipitate was separated by filtration and dried, then recrystallized from acetonitrile/diethyl ether, and finally dried under reduced pressure. Yield was 2636.44 mg (7.31 mmol, 85.46%). FT-IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3160.96 (C-Haliph), 1433.13, 1332 (Carom-Nimi), 840.25 (P-F), 764, 716 (C-SThioph). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.77 (s, 1H, hi), 8.59 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, ha), 8.26 (s, 1H, he), 7.84 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, hh), 7.66 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H, hd), 7.42 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H, hf), 7.27 (dd, J = 9.1, 6.8 Hz, 1H, hb), 7.18 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, hg), 7.12 (dd, J = 4.8, 3.7 Hz, 1H, hc), 5.99 (s, 2H, hj). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 136.03, 130.34, 129.98, 128.98, 128.04, 126.63, 125.30, 124.88, 118.69, 117.99, 113.51, 47.96. Anal. Calc. for C12H11N2SPF6: C, 40; H, 3.08; N, 7.77. Found: C, 39.06; H, 2.23; N, 6.15%.

Synthesis of 1-methyl 2-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-2H-imidazo[1,5-α]pyridin-4-ium hexafluorophosphate(V); (2.HPF6)

Synthesis of 2.HPF6 is similar to 1.HPF6. A mixture of 2-acetyl pyridine (1500 mg, 12.38 mmol) and 2-thiophene methylamine (1401.44 mg, 12.38 mmol) in 5 mL of toluene was stirred for 10 h at room temperature. Then stirring of crushed 91% paraformaldehyde powder (304 mg, 10.12 mmol) and corresponding Schiff base (E)-N-((1-(pyridin-2-yl)ethylidene)-1-(thiophen-2-yl)methanamine (2210.38 mg, 10.21 mmol) was continued for 18 h. After that, 5 mL of 4(N) HCl in diethyl ether was added slowly. The rest of the procedure is similar to 1.HPF6. Yield was 2500 mg (6.68 mmol, 86.16%). FT-IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3170 (C-Haliph), 1450, 1342 (Carom-Nimi), 843(P-F), 774 (C-SThioph).1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6). δ 9.59 (s, 1H, hi), 8.45 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, ha), 7.82 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, hg), 7.64 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, hd), 7.31 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, he), 7.17 (m, 4H, hb,f), 7.11 (t, J = 4 Hz, 1H, hc), 5.90 (s, 2H, hh), 2.62 (s, 3H, hj). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 135.80, 130.37, 129, 128.13, 127.21, 125.38, 124.27, 123.65, 122.03, 118.15, 113.85, 45.82, 8.46. Anal. Calc. for C13H13N2SPF6: C, 41.72; H, 3.50; N, 7.48. Found: C, 41.52; H, 2.63; N, 6.55%.

Ag(I)-NHC complex, 1a

Ag2O (55.54 mg, 0.24 mmol) was floated in an acetonitrile solution of 1.HPF6 (150 mg, 0.41 mmol), and was stirred for 6 h in the dark at room temperature until most of the Ag2O disappeared. To get rid of the unreacted Ag2O, the solution was filtered through a Celite plug. Following the removal of the remaining solvent at lower pressure, the resultant solid was recrystallized from acetonitrile/diethyl ether. Yield was 160 mg, (0.23 mmol, 77%). FT-IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3145(C-Haliph), 1441.79, 1334.14(Carom-Nimi), 840.25(P-F), 733.28(C-SThioph). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.59 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, ha), 8.03 (s, 1H, he), 7.63 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, hh), 7.50 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, hd), 7.28 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H, hf), 7.07–6.97 (m, 2H, hb,c), 6.87 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H, hc), 5.94 (s, 2H, hj). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.32, 139.46, 131.09, 128.41, 127.73, 127.64, 124.54, 123.74, 118.39, 114.93, 113.15, 50.64. Anal. Calc. for C24H20N4S2AgPF6: C, 42.30; H, 2.96; N, 8.22; Found: C, 41.65; H, 2.19; N, 7.67%.

Au(I)-NHC complex, 1b

The complex 1a (185 mg, 0.27 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL of acetonitrile at room temperature; a white precipitate was formed after adding Au(SMe2)Cl (79.80 mg, 0.27 mmol), into 1a. The mixture was filtered and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the resulting solid was recrystallized from acetonitrile/diethyl ether. Yield was 199.20 mg (0.26 mmol, 75.23%). FT-IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3149.30, 2919, 2847 (C-Haliph), 1450, 1346(Carom-Nimi), 841(P-F), 721(C-SThioph). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) 8.69 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, ha), 8.06 (s, 1H, he), 7.66 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, hh), 7.49 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, hd), 7.29 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, hf), 7.08 (dd, J = 8.9, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (dd, J = 5.0, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.94 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 5.97 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 174.81, 138.86, 131.56, 130.67, 128.62, 127.75, 124.26, 118.55, 115.77, 113.46, 50.25, 29.51. Anal. Calc. for C24H20N4S2AuPF6: C, 37.41; H, 2.62; N, 7.27; Found: C, 36.68; H, 1.57; N, 6.48%.

Ag(I)-NHC complex, 2a

Similar to complex 1a, complex 2a was prepared by taking the mixture of 2.HPF6 (150 mg, 0.40 mmol) and silver oxide (55.54 mg, 0.24 mmol) in 15 mL dry acetonitrile and stirred for 6 h, rest of the procedure like 1a. Yield was 157.21 mg, (0.23 mmol, 76.49%). FT-IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3160 (C-Haliph), 1432, 1329(Carom-Nimi), 842(P-F), 757(C-SThioph). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.51 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (m, 1H), 7.13 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 5.86 (s, 2H), 2.01 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.89, 139.38, 135.69, 128.39, 128.12, 127.70, 125.55, 124.42, 123.63, 118.28, 114.91, 48.44, 8.95. Anal. Calc. for C26H24N4S2AgPF6: C, 44.02; H, 3.40; N, 7.90; Found: C, 43.52; H, 2.69; N, 7.08%.

Au(I)-NHC complex, 2b

When the acetonitrile solution of Au(SMe2)Cl solution (76.79 mg, 0.26 mmol in 5 mL acetonitrile) was added dropwise to the acetonitrile solution of complex 2a (185 mg, 0.26 mmol) immediate white precipitate of AgCl was observed. The mixture was continued to stirrer for another 2 h and the rest of the procedure like 1b. Yield was 199.32 mg (0.25 mmol, 76.14%). FT-IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3158(C-Haliph), 1432, 1329(Carom-Nimi), 840(P-F), 761(C-SThioph). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.66 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (m, 1H), 7.16 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 5.94 (s, 2H), 2.18 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 174.07, 143.31, 138.71, 129.96, 128.08, 127.54, 125.60, 124.41, 123.61, 115.70, 112.78, 45.72, 8.53. Anal. Calc. for C26H24N4S2AuPF6: C, 39.10; H, 3.02; N, 7.02; Found: C, 38.48; H, 2.63; N, 6.29%.

Crystallography

A Bruker CCD X8 Kappa APEX II diffractometer was used with a graphite monochromator and MoKα radiation (l = 0.71073). Direct techniques using SHELX-97 were employed to solve the molecular crystal structure of the Ag(I), and Au(I) complexes 47. Hydrogen atoms were refined isotropically as riding atoms at their theoretical optimal places in the final structure using SHELXL, except the hydrogen atoms that were positioned for a discussion of interactions and bonding. All non-hydrogen atoms in the structure had anisotropic displacement parameters. ORTEP software was used for structural drawing. Table S1 provides more thorough details on the structural determination.

Electrochemistry

Cyclic voltammetry experiments were performed with CH instrument, USA (model CHI660C) in a three electrodes electrochemical cell. A Pt-disc working electrode, a platinum wire auxiliary electrode, and a saturated calomel reference electrode were contained within the electrochemical cell. All the experiments were conducted in an argon environment using acetonitrile (0.1 M, Bu4N[PF6] solution. Complex 1b and 2b were applied after each experiment as an internal standard, according to US recommendations.

Bacterial strain and media

Ampicillin is a broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic, however, some of the S. aureus strains are resistant to ampicillin. To check and compare the antimicrobial potential of the newly synthesized thiophene functionalized-NHC complexes, a clinically isolated ampicillin-resistant strain of S. aureus was received from the Department of Microbiology, BankuraSammilani Medical College and Hospital, Kenduadihi, Bankura 722,102, West Bengal, India and used a test strain. The ampicillin-resistant S. aureus was grown on nutrient agar (NA) and nutrient broth (NB), for single colonies and liquid cultures, respectively. All solid and liquid growth media were purchased from HiMedia, India.

Antimicrobial assay

After successful synthesis and characterization of all four NHC complexes were further checked for antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacteria, S. aureus, and Gram-negative bacteria, P. aeruginosa using an agar well diffusion assay. The bacterial cultures were grown for and maintained in NA and NB. The complexes 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b were dissolved in DMSO to check antimicrobial activity. DMSO alone and ampicillin disk (10 µg/mL) alone were used controls in respective experiments. The agar well diffusion assay was performed on NA plates as described earlier 44. The zone of clearance surrounding the bored well is considered an activity of the respective complex.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination

The MIC assay for complexes 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b was performed using 96 well microtitre plate dilution method. Different dilutions of NHC complexes (0–512 µg/mL) were prepared in DMSO using synthesized dry powder. Culture conditions and experiment setup were followed as described earlier. MIC was determined as the minimum concentration that restricts the S. aureus while the final OD was recorded after 24 h of incubation with NHC complexes48next, to check and confirm the MIC values and synergistic activity of NHC complexes with ampicillin, S. aureus was grown in the presence of respective combinations of complexes and ampicillin (10 µg/mL). OD was recorded every 2 h of intervals till 24 h while the untreated cultures were used as control43. All the experiments were performed three times independently in triplicates to analyze the final results.

Crystal violate assay

To check the biofilm eradication potential of NHC complexes, a crystal violate assay was performed using 48 h fully grown ampicillin-resistant S. aureus biofilms. Untreated biofilms and 1% triton X-100 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively while 1% DMSO was used as blank. Biofilms treated with NHC complexes with or without ampicillin were used as tests to determine the individual or synergistic potential against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus biofilms. The whole experimental setup and design were followed as described earlier49. The experiment was performed three times independently in triplicates to conclude the final results.

ATP release assay

Actively growing cultures (1 mL) of S. aureus (0.2 OD600 24 h grown culture) were treated with compound 1b (64 µg/ mL) and 2b (32 µg/ mL) in a time-dependent manner. After incubation, the cells were separated by centrifugation (8000 g) and washed with PBS (Gibco, USA) twice. The cells were recovered from the pellets were resuspended in 50 µl of lysis buffer (Promega, USA), mixed gently for 1 min and centrifuged (8000 g). The supernatant was collected and 10 µl of the dilution was added to standard reaction solution (90 µl) from the ATP determination kit (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, USA). Oxyluciferin concentration was determined after measuring luminescence on a white plate using a Lumat LB 9501 luminometer (Promega, USA). The protein content was assayed using the BCA kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) and sample luminescence was expressed as RLU/mg of protein. Data from three separate measurements were used to calculate average values.

Scanning electron microscopy

To confirm and determine the antimicrobial action of NHC complexes on bacterial cells, a scanning electron microscopy experiment is carried out. All the sample preparation and experiment setup were followed as described earlier with some modifications as per requirement with the sample process50,51. Ampicillin-resistant S. aureus cell samples were treated with lethal or sub-lethal doses or respective NHC complexes while untreated cell samples were used as negative control. Samples were observed and imaged at multiple different places of coverslips to ensure the results before the conclusion.

Molecular docking analysis

To elucidate the mechanism of action of NHC complexes against ampicillin-resistant S. aureus, the refined crystal structure of β-lactamase, PDB: 3BLM (S. aureusPC1) is retrieved from the RCSB PDB database (http://www.rcsb.org). The β-lactamase structure was used as a target for docking analysis and further modified by removing preoccupied ligands, ions, and water molecules by using Chimera 1.15 (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/). For a precise output of docking, the active site residues of β-lactamase were predicted by using, Fpocket (https://bioserv.rpbs.univ-paris-diderot.fr/services/fpocket/). The refined structure of β-lactamase was finally modified again using Chimera 1.15 to remove any protein chains that are not involved in the active site52,53. The final structures of NHC complexes were determined by 1H NMR and saved in SDF format, followed by in PDB file by Biovia Discovery Studio for further interaction studies. Molecular docking experiments were performed using the HDOCK online server (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn) and analyzed further as described earlier30. The final interactions were compared and analyzed using PyMOL and Biovia Discovery Studio visualization software packages as described earlier 54,55.

Statistical analysis

All experiments including the experiments having non-parametric data have been performed independently three times in triplicates. All respective results in the present study are based on the mean ± standard deviation of the mean (SD). Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) along with the Bonferroni post-test method for comparison between groups are used for the analysis of parametric data while column statistics for non-parametric data were analyzed by one-sample t-test. The final results are only considered significant when P < 0.05 in all experiments in the respective experiments wherever applicable.

Supplementary information

The supplemental crystallographic data for this paper are contained in CCDC 2377750 (for 1a), CCDC 2377752 (for 2a), and CCDC 2377753 (for 1b). These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Data availability

The data will be available from corresponding authors on request.

Abbreviations

- NHC:

-

N-heterocyclic carbene

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- SCXRD:

-

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

- NA:

-

Nutrient agar

- NB:

-

Nutrient broth

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- OD:

-

Optical density

References

Akshay, S. D., Deekshi, V. K., Raj, J. M. & Maiti, B. Outer membrane proteins and efflux pumps mediated multi-drug resistance in salmonella: Rising threat to antimicrobial therapy. ACS Infect. Dis. 9, 2072–2092 (2023).

Sahu, P. et al. Design, synthesis and bioactivity evaluation of Ag(I)-, Au(I)- and Au(III)-quinoxaline-wingtip N-heterocyclic carbene complexes against antibiotic resistant bacterial pathogens. ChemMedChem 19, e202400236 (2024).

Theuretzbacher, U., Outterson, K., Engel, A. & Karlén, A. The global preclinical antibacterial pipeline. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 275–285 (2020).

da Cunha, B. R., Fonseca, L. P. & Calado, C. R. C. Antibiotic discovery: Where have we come from, where do we go?. Antibiotics 8, 45 (2019).

Kasca-Nebioglu, A. et al. Synthesis from caffeine of a mixed N-heterocyclic carbene−silver acetate complex active against resistant respiratory pathogens. J. Med. Chem. 49, 6811–6818 (2006).

Chakraborty, P. et al. An organogold compound as potential antimicrobial agent against drug-resistant bacteria: Initial mechanistic insights. ChemMedChem 16, 3060–3070 (2021).

Ferreira, D. R., Alves, P. C., Kirillov, A. M., Rijo, P. & André, V. Silver(I)-tazobactam frameworks with improved antimicrobial activity. Front. Chem. 9, 815827 (2022).

Smoleński, P. et al. New water-soluble polypyridine silver(I) derivatives of 1, 3, 5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane (PTA) with significant antimicrobial and antiproliferative activities. Dalton Trans. 42, 6572–6581 (2013).

Andrejević, T. P. et al. Copper(II) and silver(I) complexes with dimethyl 6-(pyrazine-2-yl)pyridine-3,4-dicarboxylate (py-2pz): The influence of the metal ion on the antimicrobial potential of the complex. RSC Adv. 13, 4376–4393 (2023).

Aulakh, J. K. et al. Silver derivatives of multi-donor heterocyclic thioamides as antimicrobial/anticancer agents: Unusual bio-activity against methicillin resistant S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and E. faecalis and human bone cancer MG63 cell line. RSC Adv. 9, 915470–915487 (2019).

Hemmert, C., Fabié, A., Fabre, A., Benoit-Vical, F. & Gornitzka, H. Synthesis, structures, and antimalarial activities of some silver(I), gold(I) and gold(III) complexes involving N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 60, 64–75 (2013).

Melaiye, A. et al. Formation of water-soluble pincer Silver(I)-carbene complexes: A novel antimicrobial agent. J. Med. Chem. 47, 973–977 (2004).

Esarev, I. V. et al. Silver organometallics that are highly potent thioredoxin and glutathione reductase inhibitors: Exploring the correlations of solution chemistry with the strong antibacterial effects. ACS Infect. Dis. 10, 1753–1766 (2024).

Gaudillat, Q. et al. Antibacterial surfaces prepared through electropolymerization of N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: A pivotal role of the metal. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 8, 2299–2311 (2025).

Balfourier, A. et al. Gold-based therapy: From past to present. PNAS 117, 22639–22648 (2020).

Hutchings, M., Truman, A. & Wilkinson, B. Antibiotics: Past, present and future. CurrOpinMicrobiol. 51, 72–80 (2019).

Cook, M. A. & Wright, G. D. The Past, Present, and Future of Antibiotics. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, 7793 (2022).

Chen, X., Lv, L., Wei, S. & Liu, W. The antimicrobial activity of auranofin and other gold complexes. Future Med. Chem. 17, 263–265 (2025).

Liu, Y. et al. Repurposing of the gold drug auranofin and a review of its derivatives as antibacterial therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 27, 1961–1973 (2022).

Mercs, L. & Albrecht, M. Beyond catalysis: N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as components for medicinal, luminescent, and functional materials applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1903–1912 (2010).

Raubenheimer, H. G. & Cronje, S. Carbene complexes of gold: Preparation, medical application and bonding. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1998–2011 (2008).

Wang, J. et al. Identification of an Au(I) N-heterocyclic Carbene compound as a bactericidal agent against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Chem. 10, 895159 (2022).

Roymahapatra, G. et al. Pyrazine functionalized Ag(I) and Au(I)-NHC complexes are potential antibacterial agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 19, 4184–4419 (2012).

Chen, X. et al. Gold(I) selenium N-heterocyclic carbene complexes as potent antibacterial agents against multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria via inhibiting thioredoxinreductase. Redox Biol. 60, 102621 (2023).

Mahdavi, S. M. et al. Synthesis of N-heterocyclic carbene gold (I) complexes from the marine betaine 1, 3-dimethylimidazolium-4-carboxylate. Dalton Trans. 53, 1942–1946 (2024).

Stenger-Smith, J. R. & Mascharak, P. K. Gold drugs with {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety: Advantages and medicinal applications. ChemMedChem 15, 2136–2145 (2020).

Özdemir, I., Denizci, A., Öztürk, H. T. & Çetinkaya, B. Synthetic and antimicrobial studies on new gold(I) complexes of imidazolidin-2-ylidenes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 18, 318–322 (2004).

Dinda, J., Adhikary, S. D., Seth, S. K. & Mahapatra, A. Carbazole functionalized luminescent Silver(I), Gold(I) and Gold(III)-N-heterocyclic carbene complexes: A new synthetic disproportionation approach towards Au(I)-NHC to provide Au(III)-NHC. New J. Chem. 37, 431–438 (2013).

Shah, R. & Verma, P. K. Therapeutic importance of synthetic thiophene. Chem. Cent. J. 12, 137 (2018).

Zhao, M. et al. Thiophene derivatives as new anticancer agents and their therapeutic delivery using folate receptor-targeting nanocarriers. ACS Omega 4, 8874–8880 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Discovery of a series of 4-Amide-thiophene-2-carboxyl derivatives as highly potent P2Y14 receptor antagonists for inflammatory bowel disease treatment. J. Med. Chem. 67, 11989–12011 (2024).

Mahdavi, S. M. et al. Gold(I) and gold(III) carbene complexes from the marine betainenorzooanemonin: Inhibition of thioredoxinreductase, antiproliferative and antimicrobial activity. RSC Med. Chem. 15, 3248–3255 (2024).

Samanta, T. et al. Synthesis, Structure and Theoretical Studies of Hg(II)-NH Carbene Complex of Annulated Ligand pyridinyl[1,2-a]{2-Pyridylimidazol}-3-ylidene hexaflurophosphate. Inorg. Chim. Acta 375, 271–279 (2011).

Behera, P. K. et al. Therapeutic potential of Ag(I)-, Au(I)-, and Au(III)-NHC complexes of 3-pyridyl wingtip N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs) against lung cancer. New J. Chem. 47, 18835–18848 (2023).

Ghdhayeb, M. Z., Haque, R. A. & Budagumpi, S. Synthesis, Characterization and Crystal Structures of silver(I)- and gold(I)-N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes Having Benzimidazol-2-Ylidene Ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 757, 42–50 (2014).

Hsu, T. H. T., Naidu, J. J., Yang, B. J., Jang, M. Y. & Lin, I. J. B. Self-assembly of silver(I) and gold(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes in solid state, mesophase, and solution. Inorg. Chem. 51, 98–108 (2012).

Dinda, J. et al. N-heterocyclic carbene supported Au(I) and Au(III) complexes: A comparison of cytotoxicities. New J. Chem. 38, 1218–1224 (2014).

Ballarin, B. et al. Primary amino-functionalized N-heterocyclic carbene ligands as support for Au(i)⋯Au(i) Interactions: Structural, electrochemical, spectroscopic and computational studies of the dinuclear [Au2(NH2(CH2)2imMe)2][NO3]2. Dalton. Trans. 41, 2445–2455 (2012).

Pažický, M. et al. Synthesis, reactivity, and electrochemical studies of gold(I) and gold(III) complexes supported by N-heterocyclic carbenes and their application in catalysis. Organometallics 29, 4448–4458 (2010).

Maity, L., Barik, S., Biswas, R., Natarajan, R. & Dinda, J. N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) boosted photoluminescence: Synthesis, structures, and photophysical properties of Bpy/phen-Au(III)-NHC complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 36, e6854 (2022).

Chakraborty, S. et al. Anti-biofilm action of cineole and Hypericum perforatum to combat pneumonia-causing drug-resistant P. aeruginosa. Antibiotics 13, 689 (2024).

Manna, S., Ghanty, C., Baindara, P., Barik, T. K. R. & Mandal, S. M. Electrochemical communication in biofilm of bacterial community. J. Basic Microbiol. 60, 819–827 (2020).

Baindara, P. et al. Characterization of the antimicrobial peptide penisin, a class Ia novel lantibiotic from Paenibacillus Sp. strain A3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 162, 1286–1299 (2016).

Chakraborty, S., Baindara, P., Mondal, S. K., Roy, D. & Mandal, S. M. Synthesis of a tetralone derivative of ampicillin to control ampicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 7(14), 149974 (2024).

Lessa, F. C. & Sievert, D. M. Antibiotic resistance: A global problem and the need to do more. Clin. Infect. Dis. 77, S1–S3 (2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 (2019 AR Threats Report).

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELX-97, Program for Crystal Structure Solution and Refinement. Univ. G{ö}ttingen, Ger. 1456 (1997).

Baindara, P., Roy, D. & Mandal, S. M. CycP: A novel self-assembled vesicle-forming cyclic antimicrobial peptide to control drug-resistant S. aureus. Bioengineering 11, 855 (2024).

Mandal, S. M. A novel hydroxyproline rich glycopeptide from pericarp of Datura stramonium: Proficiently eradicate the biofilm of antifungals resistant Candida Albicans. Biopolymers 98, 332–337 (2012).

Baindara, P. et al. Characterization of the antimicrobial peptide penisin, a class Ia novel lantibiotic from Paenibacillus Sp Strain A3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 580–591 (2016).

Dinata, R. & Baindara, P. Laterosporulin25: A probiotically produced, novel defensin-like bacteriocin and its immunogenic properties. Int. Immunopharmacol. 121, 110500 (2023).

Baindara, P., Chowdhury, T., Roy, D., Mandal, M. & Mandal, S. M. Surfactin-like lipopeptides from Bacillus clausii efficiently bind to spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 41, 14152–14163 (2023).

Baindara, P., Roy, D., Mandal, S. M. & Schrum, A. G. Conservation and enhanced binding of SARS-CoV-2 omicron spike protein to coreceptor neuropilin-1 predicted by docking analysis. Infect. Dis. Rep. 14, 243–249 (2022).

DeLano, W. L. Pymol: An open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsl. ProteinCrystallogr. 40, 82–92 (2002).

San Diego: Accelrys Software Inc. Discovery Studio Modeling Environment, Release 3.5.

Acknowledgements

JD is grateful to Prof. Sabita Acharya, Vice Chancelloor, Utkal University for constant encouragment and incitavies for PAIR programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.D. performed the experiments, data collection and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. N.J. solved the single crystal structure of the complexes. P.B. and S.M. conducted the antibacterial studies and edited the manuscript. S.J. carried out the cyclic voltammetry study. J.D. contributed to design, writing, reviewing, editing, and supervision and administered the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Das, P., Jana, N.C., Baindara, P. et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of thiophene-functionalized Ag(I) and Au(I) N-heterocyclic carbene complexes against ampicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci Rep 15, 34137 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04100-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04100-6

This article is cited by

-

Computational evaluation of an Ag (I)-N-heterocyclic carbene complex as a novel gas scavanger

Scientific Reports (2025)