Abstract

Cancer incidence continues to increase every year. Scientists strive to search for new anticancer compounds to combat this disease. Appealingly, marine environmental niches are still an untapped scaffold for natural products with chemical and biomedical diversity. Hence, fungi isolated from the Red Sea sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda were explored. Two strains were purified from the sponge and identified, depending on 18 S rRNA gene sequence, as Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2). The obtained fungal extracts were submitted to LC-HR-ESI-MS metabolomics evaluation, which showed notable variation in the chemical profiles of both extracts. The cytotoxic activity was assessed against three cancer cell lines: HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma human), MCF7 (breast cancer) and CaCo-2 (human colon carcinoma), via MTT assay. UR1 extract displayed higher antiproliferative activity with IC50 values 2.61 ± 0.12, 3.23 ± 0.21 and 3.41 ± 0.18 µg/ml against HepG2, CaCo-2 and MCF7, respectively. Whereas UR2 extract exhibited a less potent effect with IC50 values of 17.65 ± 0.28, 18.38 ± 0.19, and 22.45 ± 0.27 µg/ml. Additionally, molecular docking was conducted. Most identified compounds established strong binding affinity with the PPARG gene. Compounds 6 and 16 showed binding energy with S values − 9.13 and − 8.38 kcal/mol, respectively. The findings suggested the importance of Spheciospongia vagabunda-derived fungi in the production of cytotoxic natural compounds that could be used for cancer management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is a disease involving impaired cellular function characterized by abnormal cells growing beyond their natural boundaries1. It is globally considered a primary public health and among the leading causes of mortality, hence, it puts a tremendous burden on healthcare systems2. This threat is estimated to aggravate enormously during the coming years owing to the growing population, socioeconomic effects, and exposure to risk factors including chemicals, radiation, viruses, and genetic mutations3,4. Scientists are facing a variety of challenges related to the presently available anticancer medicaments. Accordingly, they are attempting to discover therapeutic alternatives that could be less toxic to patients and more active against resistant tumours4.

Numerous in vitro and in vivo investigations confirmed the antitumour potential of natural products5. Microbes, plants and marine organisms have all been used to produce anticancer leads6. Notably, marine ecological niches have been demonstrated to be a massive reservoir of structurally distinct bioactive metabolic products due to their unexplored biodiversity and harsh atmosphere compared to terrestrial habitats. This chemical diversity correlates exponentially with unexpected pharmacological activities and new mechanisms of action7. Marine fungi, derived from marine invertebrates, including sponges and soft corals, as well as fungi from marine plants or marine sediments have been observed to possess profound chemical and biological profiles. Several potent anticancer compounds have been identified from marine-associated fungi and are depicted as potential candidates for medical application8. Plinabulin, a fungal product from marine origin, has advanced to clinical studies9,10.

Remarkably, fungi constitute up to 73% of sponge-derived microbes. In addition, approximately 20% of all new secondary metabolites from marine fungi were purified from sponge-derived ones between 2010 and 202011. Moreover, sponges have been investigated extensively as massive producers of cytotoxic compounds, and in various cases, the isolated metabolites were found in the fungi isolated from the same sponge12,13,14,15. Therefore, exploiting marine sponge-derived fungi can, in some cases, boost the production of some valuable metabolites derived from sponges and, in other cases aiming to fight and adapt to the marine environmental conditions, they can biosynthesize completely new metabolites16. This fascinating relationship between sponges and their associated fungi has inspired us to study the fungi obtained from the Red Sea-derived sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda.

The marine sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda belongs to family Clionaidae17. Extracts obtained from S. vagabunda have displayed cytotoxic effects against several tumour cells18,19. Subsequent chemical inspection of S. vagabunda has brought about the purification of many secondary metabolites. For instance, ceramides that have exhibited pronounced cytotoxicity against liver and breast cancer cell lines18,20.

In the current research work, we explore the fungi associated with the Red Sea-derived sponge S. vagabunda with regard to the diversity in biology and chemistry. Two fungi were isolated and identified as Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2). The chemical profiles of these fungi were analysed by means of LC-HRES-MS-based untargeted metabolomics. The extracts derived from each culture were as well in vitro evaluated for the cytotoxic potential against three different cancer cell lines. Eventually, in silico molecular docking was implemented to inspect the most active metabolites and to predict their putative action mechanism. Our findings heightened the relevance of Spheciospongia vagabunda-associated fungi as an interesting source for natural anticancer lead molecules, imposing further investigations.

Materials and methods

Collection and identification of the sponge

The sponge was collected from Ahia Reefs, in the Red Sea (at latitudes 27°17′01.0′′ N and longitudes 33°46′21.0′′ E), nearly five kilometers north of Hurghada, at a depth of approximately 3 m. This area is distinguished by a long irregular reef with many lagoons and depressions. The bottom topography is featured by the presence of corals besides the seagrasses and algae in subtidal and intertidal areas. El-Sayed Abde El-Aziz (Invertebrates Department, National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Red Sea Branch, 84511 Hurghada, Egypt), identified the collected sponge as Spheciospongia vagabunda. The sponge sample was immediately put in a sterilized plastic bag comprising seawater inside an icebox, then carried for fungal isolation in the laboratory. A voucher specimen has been stored in the Pharmacognosy Department herbarium, Faculty of Pharmacy, Deraya University, New Minya City, Egypt with the number of registration Der-Ph-0112.

Chemicals

All reagents and chemicals utilized in this current research work were of high analytical grade, they were acquired from Sigma Chemical Co Ltd. (St Louis, MO, USA) and Merck (Germany).

Isolation and purification of the sponge-associated fungi

The sponge biomass was washed using sterilized sea water, dissected into fragments of about 1 cm3, then rigorously homogenized with nearly 10 times the volume of sterile seawater in a sterile mortar. Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) was used as a solid growth medium for isolating of the marine sponge-derived fungal strains. Amoxicillin and gentamycin (100 µg/L) were added to the prepared medium, in order to inhibit any contamination from bacteria. The supernatant was subjected to serial dilutions of 1 × 10− 2, 1 × 10− 3, 1 × 10− 6 and 1 × 10− 9, then subsequently transferred into the previously prepared media and set for incubation at 30 °C (1–3 days). The fungal growth was carefully monitored and the distinct hyphal tips were taken away and repeatedly sub-cultured till pure strains were recovered. For long-term storage, pure strains were maintained on plates containing 30% glycerol at -80 °C5,21.

Molecular identification of the isolated fungi and phylogenetic analysis

The fungal strains UR1 and UR2 were identified phylogenetically using sequence analyses of the partial 18 S rRNA gene and ITS (internal transcribed spacer) region, that comprises ITS1, 5.8 S rRNA gene, and ITS2 sequences, along with MasterPure Yeast DNA extraction kit (Epientre, Madison, Wisconsin), which was used to extract DNA from fungal biomass. Employing the universal fungal primers NS1 (5′- GTAGTCATATGCTTGTCTC − 3′)22 and ITS-4 (5′-TTCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′)23, DNA amplification of the 18 S rRNA gene and the complete ITS region was carried out. Sanger sequencing was performed with primers NS1 (partial 18 S rRNA gene sequence analysis) and ITS-4 (ITS sequence analysis) by LGC Genomics (Germany). MEGA11 version 11.0.1 was used for phylogenetic analysis and manual sequence corrections24. The RefSeq Targeted Loci project databases (BioProjects PRJNA39195 and PRJNA177353; both updated on 2024-10-18) were used to identify next-related strains using the BLASTn tool of NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The next-type material strains’ 18 S rRNA gene sequences and ITS sequences have been loaded into MEGA11 and aligned utilizing ClustalW25. Uniform rates were applied at all nucleotide sites, and paired deletions were used to compare sequences. The General Time Reversible model26 was used for the 18 S rRNA gene and the Kimura 2-parameter model27 for the ITS sequence dissimilarity matrix construction to determine phylogenetic trees, along with the maximum likelihood method (18 S rRNA gene sequences) and the neighbour joining method (ITS sequences). The bootstrap option (100 replications) was used to test the phylogenies. For the examination of 18 S rRNA gene and ITS sequence-based analyses, a total of 50 to 100 reference sequences were considered each. Number of reference sequences were further reduced during tree construction. Type material sequences of Talaromyces species were used as outgroup sequences. The gene sequences of strains UR1 and UR2 were submitted to GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ with accession numbers PP843230-PP843231 (18 S rRNA gene sequences) and PP843228-PP843229 (ITS sequences).

Cultivation of the pure fungal strains and culture extraction

The two pure fungal isolates were cultivated on a solid medium28,29. About 150 µL of each fungus was transferred to twenty solid plates of SDA (10 g peptone, 40 g dextrose, and 20 g agar in 1 L distilled water, Merk). Following ten days of incubation at 30 °C, agar was cut into tiny parts and then put in flasks with the extraction solvent (ethyl acetate, 300 ml). Ethyl acetate is a suitable extraction solvent because it stops the fermentation and diminishes the spores which could be brought into air after opening the Petri dishes30,31. Disruption of the mycelia is accomplished by utilizing the ultrasonic cleaner (Bransonic®) at power of 100 W, for at least 30 min. The crude extract (0.5 g) from every fungus was obtained after filtration and concentration with decreased pressure at nearly 40 °C, with the aid of a rotary evaporator (Heidolph®, 154 rpm).

LC-HR-ESI-MS metabolomics analysis

The obtained ethyl acetate extracts of the two isolated fungi were submitted to LC-HR-ESI-MS metabolomics analysis as previously reported32,33. Reversed-phase HPLC column was employed as the stationary phase in this chromatographic separation. It was a HiChrom (Berkshire, UK) C18, 75 mm × 3.0 mm, 5 μm HPLC column. Gradient elution was carried out with the use of purified water (A) and acetonitrile (B) in addition to formic acid (0.1%), applied at 300 µL/min. The chromatographic steps began by 10% B, then gradually raised to reach 100% B, followed by isocratic elution for 5 min, then reduced back to 10% B for one min (Accela HPLC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Karlsruhe, Germany) using UV-visible detector and mass spectrometer (Exactive-Orbitrap, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The HR-ESI-MS was conducted employing negative and positive ionization modes combined with spray voltage at 4.5 Kv, mass ranging from m/z 150 to 1500 and capillary temperature at 320 °C. Mzmine 2.10 data mining software was used to analyze the unprocessed MS data. Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) http://dnp.chemnetbase.com/faces/chemical/Chemi calSearch.xhtml as well as METLIN were the databases employed for the identification of the dereplicated metabolites. Whereas, the chemical structures were drawn using Chem Bio Draw Ultra 14.0 software.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity was in vitro tested against several cancer cell lines; comprising hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), human breast cancer (MCF7) and human colon carcinoma (CaCo-2), implementing the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method34. The American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) is where the cell lines were purchased. The cells were cultured utilizing DMEM (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, USA) in addition to 10% FBS (Hyclone, USA), 1% streptomycin-penicillin and 10 µg/mL of insulin (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), then placed into 96-well plates (at a density of 1.2–1.8 × 10,000 cells/well) in a volume of 100 µL with 100 µL of the tested sample per well, added in concentrations of 100, 25, 6.3, 1.6, 0.4 µg/mL. Then after 24 h, equal amounts of the MTT solution were included with 10% of the volume of the culture medium. Two to four hours were spent for incubation of the cultures, according to cell densities and their metabolic activities, at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Afterward, the cultures were taken out of the incubator, then DMSO was added in equal parts to the volume of the original culture medium for the purpose of dissolving the produced formazan crystals. Spectrophotometric measurements of the absorbance were made at wavelength of 570 nm, utilizing a microplate reader (Model 550, Bio-Rad, USA). The experiment was performed in triplicate. The IC50 values were then determined, and the results were evaluated in comparison with the standard drug doxorubicin (D1515, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), used at concentration of 100 µg/mL.

Computational study

Network pharmacology-based analysis

Screening for the targets of UR1 and UR2 compounds

The target genes of compounds characterized in the extracts derived from Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2) were obtained through searching in the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database, Analysis Platform (TCMSP) database (https://old.tcmsp-e.com/index.php)35 and Swiss Target Prediction Database (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/), with regard to chemical similarities, protein interactions and pharmacophore models. Afterwards, these target genes were transformed into their conical gene names with the use of UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/)36.

Screening of HepG2 and CaCo-2 cancer cell lines associated target genes

Genes linked to colorectal adenocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma in human were acquired from GeneCards (www.genecards.org)37 as well as the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)38 adopting the keywords " human colorectal adenocarcinoma and CaCo-2, hepatocellular carcinoma and HepG2” and species limited to “Homo sapiens”. Following the elimination of duplicate targets, overlapping component-related and disease-related proteins were determined using Venny (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/)39 intersections to anticipate the overlap among the target genes impacted by UR1 and UR2 ingredients and the potential target genes associated with HepG2 and CaCo-2 cancer cell lines.

Constructing protein–protein interaction (PPI) network

A query list of target genes was used to create a PPI network with STRING version 12.0 (https://string-db.org/)40, which was then exported to the Cytoscape software version 3.10.1 (USA)41, a free software program designed to visualize, model and analyze the networks of molecular and genetic interactions (confidence score = 0.400). Cytohubba plug-in was used for screening of the top ten important genes.

Molecular docking

The crystal structures of the potential target genes were obtained using the Protein Data Bank, EGFR (PDB ID: 1M17), PPARG (PDB ID: 7AWD), ESR1 (PDB ID: 7UJW), and GSK3B (PDB ID: 5K5N)42. AutoDockTools was utilized to create the input files for the dereplicated secondary metabolites, protein structures and cocrystallized ligands43, whereas OpenBable v2.4 was employed to process all ligands44. Molecular docking of the compounds to the proteins under investigation was conducted via AutoDock Vina45. Grid boxes that were not larger than 27,000 3 were chosen, and the “exhaustiveness” was set to 32, that is the recommended value for employing small boxes. For the purpose of validating the docking process, shown in S1 Fig, co-crystallized ligands were redocked for protein crystal structures in complexes with binding molecules. With the aid of Discovery Studio Visualizer 17.2.0, the interactions between docked compounds and the key proteins were examined.

Results

Isolation and identification of the marine sponge-associated fungi and phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic identification of the two strains depending on partial 18 S rRNA gene and ITS sequences showed that the strains represent an Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and a Penicillium sp. (UR2). Strain UR1 shared the highest partial 18 S rRNA gene sequence identity (99.39%) with Aspergillus nidulans ATCC 10074 (NG_064803) and the highest ITS sequence identity (99.80%) with Aspergillus pseudodeflectus NRRL 6135 (NR_135372.1). Strain UR2 shared highest partial 18 S rRNA gene sequence identity (99.8%) with Penicillium limosum CBS 339.97 (NG_062729.1) followed by strains of three other species with 99.7% (Penicillium samsonianum, Penicillium subarcticum, and Penicillium tricolor) and highest ITS sequence identity (99.81%) with Penicillium oxalicum NRRL 787 (NR_121232.1). The phylogenetic placement of the strains to the next related species was confirmed by the calculated phylogenetic trees shown in S2 and S3 Figures.

Metabolomics profiling of the fungi Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2) associated with the marine sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda

Metabolomic analysis is a very useful technique for chemical profiling and fingerprinting for complex crude extracts of natural origins. It is considered a large-scale analysis for secondary metabolites and serves primarily in the annotation and dereplication of major and minor constituents. Correspondingly, it plays a crucial part in the successful investigation of natural products chemo-diversity for drug discovery46,47. Considering this, the total extracts of the fungi Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2), purified from the sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda, were subjected to untargeted LC-HR-ESI-MS-based metabolomic profiling for the aim of dereplication. Both negative and positive modes of ionization were implemented to maximize the possible detection of secondary metabolites which could differ according to their ionization potential and physical characteristics (S4-S7 Figs). The tentative identification of secondary metabolites was accomplished through searching some databases namely DNP and Marinlit. S1 Table and Figs. 1 and 2 summarize the dereplicated metabolites of the marine-derived fungal strains obtained from the sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda.

Chemical dereplication of Aspergillus sp. (UR1)

Metabolomic analysis of Aspergillus sp. (UR1) total extract has brought about the putative identification of 13 diverse compounds, dereplicated mainly as alkaloids, cyclic peptides and polyketides. The mass ion peak at m/z 563.3117 [M + H]+ for the assumed molecular formula C33H42N2O6 was characterized as teraspiridole A (1), an alkaloid that had previously been purified from the creek-bottom-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus48. Another alkaloid, of benzodiazepine type, was identified as circumdatin J (2), according to the mass ion peak at m/z 376.1298 [M-H]−and the molecular formula C21H19N3O4. This compound had earlier been isolated from the marine fungus Aspergillus ostianus49. Whereas, the compound with the molecular formula C21H35NO was dereplicated as the piperidine alkaloid asperidine B (3), and/or the pyrrolidine alkaloid preussin (4) from the mass ion peak at 318.2800 [M + H] +. The former has previously been obtained from the soil-derived Aspergillus sclerotiorum PSU-RSPG17850, and the latter has been purified earlier from the fungus Simplicillium lanosoniveum TAMA 17351. Likewise, a cyclic tripeptide was characterized as sclerotiotide C (5), concurring with the mass ion peak at m/z 447.2957 [M + H]+ and the molecular formula C24H38N4O4; it had earlier been purified from the salt sediment-derived fungus Aspergillus sclerotium PT06-152. Whereas, the mass ion peak at m/z 465.2145 [M + H]+, corresponding to the suggested molecular formula C25H28N4O5, was characterized as aspercolorin (6), a cyclic tetrapeptide that had previously been obtained from Aspergillus versicolor53,54.

Alongside the previously stated compounds, two polyketides were dereplicated with mass ion peaks at m/z 407.2345 and 312.1804 [M + H]+, identified as ICM0301 C (7), previously obtained from Aspergillus sp. F-149155, and wasabidienone E (8), formerly obtained from the sponge-derived Aspergillus flocculosus 01nt.1.1.556, matched with the molecular formulas C24H35ClO3 and C16H25NO5, respectively. Moreover, the mass ion peak at m/z 337.1789 [M + H]+, concurring with the predicted molecular formula C22H24O3, was identified as asperrubrol (9), a phenylpolyene compound formerly obtained from Aspergillus niger57. The sesquiterpenoid nitrobenzyl ester with the molecular formula C22H25NO7 was characterized as 14-hydroxy-6β-p-nitrobenzoyl-cinnamolide (10) from the mass ion peak at m/z 414.1562 [M-H]−. It was previously purified from the marine green alga-derived Aspergillus versicolor58. Furthermore, metabolomics analysis of Aspergillus sp. (UR1) has brought about the characterization of a diterpenoid with norcleistanthane-type skeleton, aspergiloid D (isopimarane) (11) in consonance with the mass ion peak at m/z 321.2429 [M + H]+ and the molecular formula C20H32O3, which had previously been isolated from the endophyte Aspergillus sp. YXf359. Azaspirofuran B (12), a hetero-spirocyclic γ-lactam previously reported from the marine sediment-derived Aspergillus sydowii D2-6, was also dereplicated from the mass ion peak at m/z 396.1078 [M-H]− coinciding with the predicted formula C21H19NO760,61. Further, the mass ion peak at m/z 231.1346 [M + H]+, matched to the formula C10H18N2O4, was characterized as terramide C (13), a piperazine-2,5-dione, where hydroxamic acid residues make up both of the amino acid components. It was previously obtained from Aspergillus terreus CMI 44,33962.

Chemical dereplication of Penicillium sp. (UR2)

Chemical profiling of the marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. (UR2) total extract has led to the detection of 13 compounds, demonstrating that this fungus is a prolific reservoir of different metabolites such as diterpenoids, meroterpenoids and alkaloids. The alkaloid having the molecular formula C22H29N3O2 was dereplicated as brevicompanine A (14) and/or allo-brevicompanine B (15) from the mass ion peak at m/z 368.2323 [M + H]+. These are diketopiperazine alkaloids previously obtained from Penicillium brevicompactum63 and the deep-ocean sediment-derived Penicillium sp.64, respectively. Another closely related compound designated as mollenine B (16), was identified on the basis of the mass ion peak at m/z 397.2118 [M + H]+ and in consonance with the molecular formula C23H28N2O4. This dioxomorpholine-type alkaloid had been formerly found in Eupenicillium molle NRRL 13,06265. One more alkaloid, tyrosine-derived, was identified as TAN-1251B (17) considering the mass ion peak at m/z 397.2476 [M + H]+and the molecular formula C24H32N2O3, it had previously been discovered in Penicillium thomii RA-8966.

Besides the aforementioned compounds, metabolomic analysis of Penicillium sp. revealed the presence of diterpenoids. As an example, a cyclopiane-class diterpene was dereplicated as conidiogenone H (18) in light of the determined mass ion peak at m/z 321.2429 [M + H]+and according to the molecular formula C20H32O3. This compound had formerly been reported from the marine red alga-derived Penicillium chrysogenum QEN-24 S67. Another spiro-diterpenoid was identified as brevione I (19), in response to the determined mass ion peak at m/z 439.2483 [M + H]+, and in compliance with the molecular formula C27H34O5. This diterpenoid had been earlier purified from the deep-sea sediment-derived Penicillium sp68. Moreover, a meroterpenoid, arisugacin F (20), in agreement with the mass ion peak at m/z 439.2483 [M + H]+ and the molecular formula C27H34O5, which had previously been isolated from the endophytic fungus Penicillium sp. SXH-65, was also detected69. Whereas the mass ion peak at m/z 519.2962 [M + H]+, complying with the assumed molecular formula C29H42O8, was dereplicated as austalide H acid butyl ester (21), another meroterpenoid formerly obtained from the marine brown alga-derived Penicillium thomii KMM 464570. Also, the mass ion peak at m/z 455.2285 [M + H]+ for the anticipated molecular formula C24H30N4O5 was identified as the tetrapeptide viridic acid (22), a mycotoxin that had been isolated before from Penicillium viridicatum71. Meanwhile, the mass ion peak at m/z 323.1845 [M + H]+, agreeing with the estimated molecular formula C18H26O5, was dereplicated as the polyketide rezishanone D (23), earlier obtained from Penicillium notatum72. Furthermore, a benzopyran derivative that had formerly been reported from the marine green alga-derived Penicillium sp.73,74 was dereplicated as penostatin C (24), matched with the mass ion peak at m/z 325.2179 [M-H]− and the molecular formula C22H30O2. Additionally, one 12-membered macrolide was identified according to the mass ion peak at m/z 211.1323 [M + H]+, affirming the formula C12H18O3, as patulolide A (25), it had already been isolated from Penicillium urticae SllR5975. Finally, a methylpyrrolidine-2,4-dione derivative, characterized as cissetin (26), earlier purified from the endophytic fungus Preussia sp76. , was characterized from the mass ion peak at m/z 386.2335 [M-H]−, in consonance with the formula C23H33NO4.

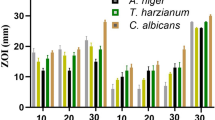

Cytotoxic activity

The crude extracts of the two fungi Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2), purified from the Red Sea sponge S. vagabunda, were in vitro assessed for their cytotoxic activity implementing MTT reduction colorimetric assay. Three different cancer cell lines; hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), human breast cancer (MCF7) and human colon carcinoma (CaCo-2) were used in this evaluation. The Aspergillus sp. (UR1) extract showed the highest antiproliferative activity with IC50 values of 2.61 ± 0.12, 3.23 ± 0.21, and 3.41 ± 0.18 µg/ml against HepG2, CaCo-2 and MCF7, respectively. Whereas Penicillium sp. (UR2) extract exhibited a less potent effect with IC50 values 17.65 ± 0.28, 18.38 ± 0.19, and 22.45 ± 0.27 µg/ml, against the same cancerous cell lines. All results are included in Table 1.

Computational study

Network pharmacology-based analysis

The significant cytotoxic activity observed, particularly targeting hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) and human colon carcinoma (CaCo-2), in the extracts derived from Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2) underscore the potential of network pharmacology. This approach proves efficacious in constructing a comprehensive network linking compounds, proteins/genes, and diseases, all in a high-throughput fashion77,78.

Screening for the targets of UR1 and UR2 compounds

The target genes of UR1 and UR2 ingredients were recuperated from the Swiss Target Prediction and TCMSP databases, including 473 genes related to UR1 ingredients and 432 genes related to UR2 ingredients. The UniProt database was then used to convert these genes into their canonical gene names.

Screening of HepG2 and CaCo-2 cancer cell lines associated target genes

The most common 167 target genes after removing duplicates are included in both HepG2 and CaCo-2 cancer cell lines and were retrieved from the databases GeneCards and NCBI. Particular search criteria were implemented to extract these genes, including the keywords “human colorectal adenocarcinoma and CaCo-2, hepatocellular carcinoma and HepG2” with a species restriction limited to “Homo sapiens”. The overlap between the target genes impacted by UR1 and UR2 components and the potential target genes associated with HepG2 and CaCo-2 cancer cell lines, was carefully visualized through creating a Venn diagram. The visual representation of two networks shared targets, as illustrated in Fig. 3. After eliminating duplicates, a set of 20 vital gene targets that UR1 and UR2 ingredients have in common and effectively target HepG2 and CaCo-2 cancer cell lines were identified as the most prominent targets.

Constructing protein–protein interaction (PPI) network

A protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was built up by submitting the 20 commonly identified targeted genes to the STRING database. The obtained results were utilized to produce a graphical representation of the PPI network via the use of Cytoscape 3.10.1 software. This network comprised 20 nodes and 124 edges, the average node connectivity was 12.40, as demonstrated in Fig. 4. The top ten important genes were then identified and extracted employing the Cytohubba plugin according to their connectivity degree throughout the network, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The higher the degree value of any gene, the more apparent it will be in the pathogenesis of the disease. These genes, in ascending manner, are EGFR, PPARG, ESR1, GSK3B, MTOR, PARP1, MMP9, CCND1, AR and PTGS2. S2 Table provides a summary of the topological parameters, comprising node degree, closeness and betweenness and for each protein.

Molecular docking

Docking studies were performed to investigate the binding between potential targets and active compounds that were detected within the UR1 and UR2 extracts. The identified compounds were undergoing molecular docking within the active sites of the top four hub genes, namely EGFR, PPARG, ESR1, and GSK3B were selected to represent the four different pathways. Firstly, we validated the docking protocol through performing re-docking of co-crystallized ligands, establishing that the RMSD was less than 2 Å, between the crystal pose and the docked pose, for a successful validation S1 Fig. Then, we docked the extracted compounds into these hub genes and the obtained docking scores are presented in S3 Table.

The docking analysis results indicated that the identified compounds in both extracts of Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2) exhibit favorable binding affinity scores with selected hub genes in comparison to the co-crystallized ligands associated with these genes. In particular, the binding modes of complexes involving EGFR-compound 13 (-6.27 kcal/mol), PPARG-compound 6 (− 9.13 kcal/mol), ESR1-compound 7 (− 7.86 kcal/mol), and GSK3B-compound 2 (− 5.95 kcal/mol) correspond to extracts from UR1. On other hands, UR2 extracts show variable binding affinity within these active sites especially, EGFR-compound 21 (− 6.23 kcal/mol), PPARG-compound 16 (-8.38 kcal/mol), ESR1-compound 15 (− 8.21 kcal/mol), and GSK3B-compound 25 (− 6.76 kcal/mol).

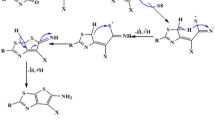

It was observed from docking results that all compounds extracted from both UR1 and UR2 exhibited strong to outstanding binding affinity with the PPARG gene when compared to other hub genes. For instance, compound 6 (identified in UR1 extract) binds to PPARG (with S value= − 9.13 kcal/mol) through forming two hydrogen bond interactions with Glu 295 and Glu 343 amino acid residues as well as forming three hydrophobic interactions with Cys 285, Ala 292 and Met 329 amino acid residues Fig. 6.

In addition, compound 16 (identified in UR2 extract) binds to PPARG (with S value= − 8.38 kcal/mol) via forming three hydrogen bond interactions with Arg 288 and Ser 342 amino acid residues. Also, it showed five hydrophobic interactions with Leu 228, Cys 285, Ile 326, Met 329, and Leu 333 amino acid residues (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Sponge-associated fungi have been shown to be abundant sources of metabolites with distinctive structures and biological activities. We investigate, herein, the chemical profiles of the total extracts of two fungal strains purified from the Red Sea-derived sponge S. vagabunda.

The fungal strains were isolated from the sponge and were identified, according to the 18 S rRNA gene sequence analysis, as Aspergillus sp. (UR1) and Penicillium sp. (UR2). The strains were then cultured, and each culture was extracted with ethyl acetate. The resulting extracts were submitted to metabolomics evaluation through LC-HR-ESI-MS. Chemical profiling of Aspergillus sp. (UR1) extract has resulted in the characterization of 13 metabolites, dereplicated mainly as alkaloids, cyclic peptides and polyketides. Whereas, the chemical profiling of Penicilluim sp. (UR2) extract brought about the putative identification of 13 compounds of various classes comprising alkaloids, diterpenoids and meroterpenoids.

Furthermore, the cytotoxic activity of both extracts was assessed, applying the MTT colorimetric reduction assay, against 3 cancer cell lines; HepG2, CaCo-2 and MCF7. Aspergillus sp. (UR1) extract displayed higher antiproliferative activity with IC50 values 2.61 ± 0.12, 3.23 ± 0.21 and 3.41 ± 0.18 µg/ml against HepG2, CaCo-2 and MCF7, respectively. Similarly, Penicillium sp. (UR2) extract revealed a less potent effect with IC50 values of 17.65 ± 0.28, 18.38 ± 0.19, and 22.45 ± 0.27 µg/ml, against the same cancerous cell lines. The presence of cytotoxic secondary metabolites in the investigated crude extracts might provide an explanation for the observed cytotoxic potential. Apparently, many of the identified compounds have been reported in earlier studies to display cytotoxicity towards different cancer cell lines, which may eventually support the conclusion of our investigation. For instance, compound 4 was found to exhibit significant cytotoxicity against the triple-negative breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB231)79. Whereas, compound 7 has been shown to display weak cytotoxic effect towards Hela S3 and NCI-H69 cells80. In addition, compound 10 has been reported to exert significant cytotoxicity against HCT-116 human colon carcinoma cells and moderate selective toxicity towards a panel of renal tumour cell lines58, and compound 12 was proved to exhibit notable cytotoxic and antitumour activities81. Furthermore, it has been reported that compound 15 showed weak inhibitory effect on five human cancer cell lines (K-562, HL-60, Hela, BGC-823 and MCF-7)82. However, compound 19 has been documented to display significant cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 comparable to the positive control cisplatin68. Moreover, previous studies also reported that compound 20 demonstrated weak cytotoxicity towards Hela, HL-60 and K-562 cell lines69, and compound 24 has been also evidenced to exert significant cytotoxic effect against a panel of cancer cell lines73.

Additionally, in silico screening was carried out to fully comprehend the cytotoxic potential of the dereplicated metabolites in the fungal extracts. The compounds were undergoing molecular docking within the active sites of EGFR, PPARG, ESR1, and GSK3B genes (being the top four hub genes), representing four different pathways. The results demonstrated that most of the identified secondary metabolites have established strong binding affinities with the PPARG (Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma) gene. PPARG is one of the transcription factors that belongs to the nuclear receptor family. Its anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic characteristics have been extensively documented across various cancers such as colon, esophageal, breast, lung, and prostate cancer83. Recent studies have demonstrated that activating endogenous or ectopically expressed PPAR-γ ligands is adequate to trigger growth arrest and apoptosis in diverse cancer cell lines84. Noteworthy, compound 6 (identified in UR1 extract) showed a binding energy to PPARG with S value of -9.13 kcal/mol, whereas compound 16 (identified in UR2 extract) showed a binding energy to PPARG with S value of -8.38 kcal/mol.

In summary, our study emphasized the prominence of the Red Sea sponge S. vagabunda-associated fungi as a valuable source of cytotoxic metabolites, which could promote future drug development for cancer management. Thus, additional studies are recommended.

Data availability

The gene sequences (of strains UR1 and UR2) generated/analysed during the current study are available in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ with accession numbers PP843230-PP843231 (18 S rRNA gene sequences) and PP843228-PP843229 (ITS sequences).

References

Gutschner, T. & Diederichs, S. The hallmarks of cancer. RNA Biol. 9(6), 703–719 (2012).

Siegel, R. L. et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. Ca Cancer J. Clin. 73(1), 17–48 (2023).

Xia, C. et al. Cancer statistics in China and united States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin. Med. J. 135 (05), 584–590 (2022).

Adido, H. E. F. et al. In silico studies on cytotoxicity and antitumoral activity of acetogenins from Annona muricata L. Front. Chem. 11 (2023).

Taher Mohie el-dien. Paralemnalia thyrsoides-associated fungi: Phylogenetic diversity, cytotoxic potential, metabolomic profiling and docking analysis. BMC Microbiol. 23(1), 308 (2023).

Sofi, F. A. & Tabassum, N. Natural product inspired leads in the discovery of anticancer agents: An update. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 41(17), 8605–8628 (2023).

El-Hossary, E. M. et al. Natural products repertoire of the red sea. Mar. Drugs. 18(9), 457 (2020).

Nathani, N. M. et al. Marine Niche: Applications in pharmaceutical sciences. Transl. Res. 10, 978–981 (2020).

Mohanlal, R. W., LLoyd, K. & Huang, L. Plinabulin, a novel small molecule clinical stage IO agent with anti-cancer activity, to prevent chemo-induced neutropenia and immune related AEs (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2018).

Blayney, D. W. et al. Efficacy of plinabulin vs pegfilgrastim for prevention of docetaxel-induced neutropenia in patients with solid tumors: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 5(1), e2145446–e2145446 (2022).

Trinh, P. T. H. et al. Cytoprotective polyketides from sponge-derived fungus Lopadostoma pouzarii. Molecules 27(21), 7650 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. Neuritogenic activity-guided isolation of a free base form manzamine A from a marine sponge, Acanthostrongylophora aff. ingens (Thiele, 1899). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 56(6), 866–869 (2008).

Waters, A. L. et al. An analysis of the sponge Acanthostrongylophora igens’ microbiome yields an actinomycete that produces the natural product manzamine A. Front. Mar. Sci. 1, 54 (2014).

McKay, M. J. et al. 1, 2-Bis (1 H-indol-3-yl) ethane-1, 2-dione, an Indole alkaloid from the marine sponge Smenospongia sp. J. Nat. Prod. 65(4), 595–597 (2002).

Asiri, I. A., Badr, J. M. & Youssef, D. T. Penicillivinacine, antimigratory diketopiperazine alkaloid from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium vinaceum. Phytochem. Lett. 13, 53–58 (2015).

Samirana, P. O. et al. Marine sponge-derived fungi: Fermentation and cytotoxic activity. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 11, 21–39 (2021).

Chan, Y. S. et al. Antimicrobial, antiviral and cytotoxic activities of selected marine organisms collected from the coastal areas of Malaysia. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 26(1), 13 (2018).

Eltamany, E. et al. Antitumor metabolites from the red sea sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda. Planta Med. 80(10), PB5 (2014).

Eltamany, E. et al. Anticancer activities of some organisms from Red Sea, Egypt. Catrina: Int. J. Environ. Sci. 9(1), 1–6 (2014).

Eltamany, E. E. et al. Cytotoxic ceramides from the Red Sea sponge Spheciospongia vagabunda. Med. Chem. Res. 24, 3467–3473 (2015).

Ahmed, A. M. et al. Evaluation of the anti-infective potential of the seed endophytic fungi of Corchorus olitorius through metabolomics and molecular docking approach. BMC Microbiol. 23(1), 355 (2023).

May, L. A., Smiley, B. & Schmidt, M. G. Comparative denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of fungal communities associated with whole plant corn silage. Can. J. Microbiol. 47(9), 829–841 (2001).

White, T. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics (PCR Protocols: A guide to methods and applications/Academic Press, Inc, 1990).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38(7), 3022–3027 (2021).

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22(22), 4673–4680 (1994).

Nei, M. & Kumar, S. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics 3 (Oxford University Press, 2000).

Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16, 111–120 (1980).

Hisham Shady, N. et al. Metabolomic profiling and cytotoxic potential of three endophytic fungi of the genera Aspergillus, penicillium and fusarium isolated from Nigella sativa seeds assisted with docking studies. Nat. Prod. Res. 37 (17), 2905–2910 (2023).

Katoch, M. et al. Diversity, phylogeny, anticancer and antimicrobial potential of fungal endophytes associated with Monarda citriodora L. BMC Microbiol. 17, 1–13 (2017).

Abdelwahab, M. F. et al. Tanzawaic acid derivatives from freshwater sediment-derived fungus Penicillium sp. Fitoterapia 128, 258–264 (2018).

Kjer, J. et al. Methods for isolation of marine-derived endophytic fungi and their bioactive secondary products. Nat. Protoc. 5(3), 479–490 (2010).

Abdelaleem, E. R. et al. Apple extract protects against indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in rats by suppressing oxidative stress–the implication of Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway: In silico and in vivo studies. J. Funct. Foods. 112, 105926 (2024).

Elsayed, Y. et al. Metabolomic profiling and biological investigation of the marine spong-derived bacterium Rhodococcus sp. UA13. Phytochem. Anal. 29 (6), 543–548 (2018).

Ahmed, S. S. et al. Metabolomics of the secondary metabolites of Ammi visnaga L. roots (family Apiaceae) and evaluation of their biological potential. South. Afr. J. Bot. 149, 860–869 (2022).

Ru, J. et al. TCMSP: a database of systems Pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminform. 6, 13 (2014).

UniProt, C. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 (D1), D480–D489 (2021).

Stelzer, G. et al. The genecards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 54 (1–1 30 33), 1 (2016).

Sayers, E. W. et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(D1), D23–D28 (2019).

Oliveros, J. C. VENNY. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn Diagrams. (2007). http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html.

Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1), D638–D646 (2023).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13(11), 2498–2504 (2003).

Berman, H. M. et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 235–242 (2000).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30(16), 2785–2791 (2009).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31(2), 455–461 (2010).

Jaghoori, M. M., Bleijlevens, B. & Olabarriaga, S. D. 1001 Ways to run AutoDock Vina for virtual screening. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 30(3), 237–249 (2016).

El-Hawary, S. S. et al. Metabolomic profiling of three Araucaria species, and their possible potential role against COVID-19. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 40(14), 6426–6438 (2022).

Wolfender, J.-L. et al. Current approaches and challenges for the metabolite profiling of complex natural extracts. J. Chromatogr. A 1382, 136–164 (2015).

Cai, S. et al. Spiro fused diterpene-indole alkaloids from a creek-bottom-derived Aspergillus terreus. Org. Lett. 15(16), 4186–4189 (2013).

Ookura, R. et al. Structure revision of circumdatins A and B, benzodiazepine alkaloids produced by marine fungus Aspergillus ostianus, by X-ray crystallography. J. Org. Chem. 73(11), 4245–4247 (2008).

Phainuphong, P. et al. Asperidines A-C, pyrrolidine and piperidine derivatives from the soil-derived fungus Aspergillus sclerotiorum PSU-RSPG178. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26(15), 4502–4508 (2018).

Fukuda, T. et al. Isolation and biosynthesis of preussin B, a pyrrolidine alkaloid from Simplicillium lanosoniveum. J. Nat. Prod. 77(4), 813–817 (2014).

Zheng, J. et al. Cyclic tripeptides from the halotolerant fungus Aspergillus sclerotiorum PT06-1. J. Nat. Prod. 73(6), 1133–1137 (2010).

Sarojini, V. et al. Cyclic tetrapeptides from nature and design: A review of synthetic methodologies, structure, and function. Chem. Rev. 119(17), 10318–10359 (2019).

Lin, W. et al. Novel chromone derivatives from the fungus aspergillus versicolor isolated from the marine sponge Xestospongia exigua. J. Nat. Prod. 66(1), 57–61 (2003).

Kumagai, H. et al. ICM0301s, new angiogenesis inhibitors from Aspergillus sp. F-1491 I. taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and biological activities. J. Antibiotics 57(2), 97–103 (2004).

Trinh, P. T. H. et al. Antimicrobial activity of natural compounds from sponge-derived fungus Aspergillus flocculosus 01NT.1.1.5. J. Biotechnol. 16(4), 729–735 (2018).

Rabache, M., Neumann, J. & Lavollay, J. Phenylpolyenes d’Aspergillus niger: Structure et proprietes de l’asperrubrol. Phytochemistry 13(3), 637–642 (1974).

Belofsky, G. N. et al. New cytotoxic sesquiterpenoid nitrobenzoyl esters from a marine isolate of the fungus Aspergillus versicolor. Tetrahedron 54(9), 1715–1724 (1998).

Guo, Z. K. et al. p-Terphenyl and diterpenoid metabolites from endophytic Aspergillus sp. YXf3. J. Nat. Prod. 75(1), 15–21 (2012).

Ibrahim, S. R. M. et al. Secondary metabolites, biological activities, and industrial and biotechnological importance of Aspergillus sydowii. Mar. Drugs 21(8), 441 (2023).

Ren, H. et al. Two new hetero-spirocyclic γ-lactam derivatives from marine sediment-derived fungus Aspergillus sydowi D2–6. Arch. Pharmacal. Res. 33(4), 499–502 (2010).

Garson, M. J., Jenkins, S. M., Staunton, J. & Chaloner, P. A. Isolation of some new 3, 6-dialkyl-1, 4-dihydroxypiperazine-2, 5-diones from Aspergillus terreus. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1, 901–903 (1986).

Miyako Kusano, G. S. Brevicompanines A and B: new plant growth regulators produced by the fungus, Penicillium brevicompactum. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1(17), 2823–2826 (1998).

Du, L. et al. Diketopiperazine alkaloids from a deep ocean sediment derived fungus Penicillium sp. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 57(8), 873–876 (2009).

Wang, H.-J. et al. Mollenines A and B: New dioxomorpholines from the ascostromata of Eupenicillium molle. J. Nat. Prod. 61(6), 804–807 (1998).

Bonjoch, J. & Diaba, F. Synthesis of immunosuppressant FR901483 and biogenetically related TAN1251 alkaloids. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry (ed. Atta.Ur, R.) 3–60 (Elsevier, Netherlands, 2005).

Gao, S.-S. et al. Conidiogenones H and I, two new diterpenes of cyclopiane class from a marine-derived endophytic fungus Penicillium chrysogenum QEN-24S. Chem. Biodivers. 8(9), 1748–1753 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. A sterol and spiroditerpenoids from a Penicillium sp. isolated from a deep sea sediment sample. Mar. Drugs 10(2), 497–508 (2012).

Sun, X. et al. Two new meroterpenoids produced by the endophytic fungus Penicillium sp. SXH-65. Arch. Pharm. Res. 37(8), 978–982 (2014).

Zhuravleva, O. I. et al. Meroterpenoids from the alga-derived fungi Penicillium thomii Maire and Penicillium lividum Westling. J. Nat. Prod. 77(6), 1390–1395 (2014).

Lund, F. & Frisvad, J. C. Chemotaxonomy of Penicillium aurantiogriseum and related species. Mycol. Res. 98(5), 481–492 (1994).

Maskey, R. P., Grün-Wollny, I. & Laatsch, H. Sorbicillin analogues and related dimeric compounds from Penicillium notatum. J. Nat. Prod. 68(6), 865–870 (2005).

Iwamoto, C. et al. Absolute stereostructures of novel cytotoxic metabolites, penostatins A-E, from a Penicillium species separated from an Enteromorpha alga. Tetrahedron 55(50), 14353–14368 (1999).

Takahashi, C. et al. Penostatins, novel cytotoxic metabolites from a Penicillium species separated from a green alga. Tetrahedron Lett. 37(5), 655–658 (1996).

Sekiguchi, J. et al. Structure of patulolide a, a new macrolide from penicillium urticae mutants. Tetrahedron Lett. 26(19), 2341–2342 (1985).

Talontsi, F. M. et al. Antiplasmodial and cytotoxic dibenzofurans from Preussia sp. harboured in Enantia chlorantha Oliv. Fitoterapia 93, 233–238 (2014).

Wang, J. & Li, X.-J. Network pharmacology and drug discovery. Sheng li ke xue jin zhan [Progress in physiology] 42(4), 241–245 (2011).

Zhang, R. et al. Network pharmacology databases for traditional Chinese medicine: Review and assessment. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 123 (2019).

Seabra, R. et al. Effects and mechanisms of action of preussin, a marine fungal metabolite, against the triple-negative breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231, in 2D and 3D cultures. Mar. Drugs 21(3), 166 (2023).

Kumagai, H. et al. ICM0301s, new angiogenesis inhibitors from Aspergillus sp. F-1491 I. taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and biological activities. J. Antibiot. 57(2), 97–103 (2004).

Zihad, S. N. K. et al. Isolation and characterization of antibacterial compounds from Aspergillus fumigatus: An endophytic fungus from a mangrove plant of the Sundarbans. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022(1), 9600079 (2022).

Wang, N. et al. Penicimutanin C, a new alkaloidal compound, isolated from a neomycin-resistant mutant 3-f-31of Penicillium purpurogenum G59. Chem. Biodivers. 17(7), e2000241 (2020).

Astarci, E. & Banerjee, S. PPARG (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma). J. Atl. Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. 13, 417–421 (2009).

Grommes, C., Landreth, G. E. & Heneka, M. T. Antineoplastic effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. Lancet Oncol. 5(7), 419–429 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank Deraya University for support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This project China 25 was financially supported by the Academy of Scientific Research and Technology (ASRT), Egypt.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.H.A., A.M.A. and M.F.A. contributed to investigation, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft and writing—reviewing and editing of the manuscript. A.H.E. contributed to formal analysis, validation and review and editing of the manuscript. MH was involved in methodology, software, formal analysis, visualization and writing—reviewing and editing of the manuscript. S.P.G. and P.K. contributed to methodology, data curation, validation and writing—reviewing and editing of the manuscript. JW and URA were involved in conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, methodology, validation and writing—reviewing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelhafez, O.H., Abdelwahab, M.F., Elmaidomy, A.H. et al. Cytotoxicity evaluation and metabolomic profiling of Spheciospongia vagabunda-associated fungi corroborated by in silico studies. Sci Rep 15, 20115 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04162-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04162-6