Abstract

Explainable AI has garnered significant traction in science communication research. Prior empirical studies have firmly established that explainable AI communication could improve trust in AI and that trust in AI engineers was argued to be an under-explored dimension of trust. In this vein, trust in AI engineers was also found to be a factor in determining public perceptions and acceptance. Thus, a key question emerges: Can explainable AI improve trust in AI engineers? In this study, we set out to investigate the effects of explainability perception on trust in AI engineers, while accounting for trust in AI system. More concretely, through a public opinion survey in Singapore (N = 1,002), structural equation modelling analyses revealed that perceived explainability significantly shaped all trust in AI engineers’ dimensions (i.e., ability, benevolence, and integrity). Results also revealed that trust in the ability of AI engineers subsequently shaped people’s attitude and intention to use various types of autonomous passenger drones (i.e., tourism/daily commute/cross-country/city travel). Several serial mediation pathways through trust in ability and attitude were identified between explainability perception and use intention. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Science fiction movies have long portrayed pilotless flying vehicles as a future mode of transportation. Today, this imagined future has, to some extent, materialized. In China, autonomous passenger drones, which have received operation certification1, are now commercially available in the private market. Autonomous drone technologies are also researched and developed in countries such as the U.S2 and Germany3. What movie producers had not realized at the time was that they were in fact depicting what is now known as “urban air mobility (UAM)”4, a concept that entails drone fleet operation in urban low-altitude airspace. As a mode of transportation, UAM offers a more sustainable option of transport due to electric drone’s low emission levels and shorter travel time. It can also increase accessibility due to lower operating costs5,6. Powered by AI, these benefits can be substantially enhanced as algorithms facilitate the computation of optimal flight trajectories and power efficiency, minus the cost, work schedule, and the inevitable errors of a human pilot7.

However, people tend not to readily place trust in risk-laden AI applications such as these “flying cars.” Indeed, empirical research reports that people generally held a negative view toward AI. For example, a majority of the American people believed that AI was either risky or that its risks outweighed its benefits8. A major problem, as research suggests, relates to the perception of uncertainty toward the AI model and the output it produces9. The use of explainable AI (XAI) has been proposed to be a key technique that improves technological acceptance through uncertainty reduction10,11. In this vein, uncertainty reduction theory (URT)12 offers an appropriate theoretical framework to examine how XAI operates to yield desirable end-user internal outcomes. Some recent theoretical works similarly point to the promises of URT in understanding mechanisms leading to trust in AI13.

As social sciences research suggests that XAI could result in various desirable cognitive and affective outcomes14, it seems particularly clear that XAI has great potential in improving end-user trust 15,16,17. Recognizing the complexities of the trust in AI concept18,19, Ho and Cheung20 argued that there exists a need to conceptually differentiate between trust in AI system and trust in AI engineers. They contended that, while trust in system is a direct and largely intuitive concept, AI systems are nevertheless neutral by default. Instead, biases and errors often originate from human-level factors such as data training and value definition. This raises an important question: Can explainability perception exert effects on human entities? More concretely, trust in AI engineers? If so, it may suggest that the XAI technique operates as more than a system level factor that shapes perceptions toward the creators behind the algorithms. This may indicate that XAI presents broader implications than what literature currently suggests. The present study is an attempt to address this question.

We set out to elucidate the relationship between explainability perception, trust in AI engineers, and public acceptance. By isolating the effects on trust in AI engineers through accounting for trust in system, we add to the field by proposing that explainability perception can exert a direct effect on trust in AI engineers, independent of trust in AI system. A significant finding may suggest that trust in AI engineers can be as important as AI system trust in the XAI context. Moreover, we seek to advance trust models by examining the distinct contributions of human trustworthiness factors, thereby offering a more complete understanding of the internal processes that underlie public opinion and acceptance of AI.

Literature review

Explainable AI (XAI) and perceived explainability

Explainable AI (XAI) is a fast-growing field in academia as it has great potential to offer a range of benefits in the midst of rapid AI development21. Broadly put, XAI is a technique that explicitly explains the algorithms and the output it produces22,23. The use of XAI appropriately addresses the “black box” nature of AI, in which end-users are obscured from the algorithmic decision-making process24. Indeed, the XAI technique enjoys many benefits, including but not limited to, engineering verification, data improvement, and legal certification25. While social sciences and engineering fields largely share similar conceptual definitions of XAI, its application significantly diverges. For example, even though engineers define XAI as “the ability of machine learning models to offer understandable justifications for their predictions or decisions” (p. 2), they typically refer to it as mathematical equations that demonstrate the rationale of algorithmic behaviors26. Gunning and colleagues27 offered a conceptual definition well-suited for communication science in the lay context, defined as methods that “make [the AI system’s] behavior more intelligible to humans by providing explanations” (p. 4). It is equally important to recognize that the objectives of XAI can also significantly diverge across its intended recipients. For example, XAI geared toward professionals are different from those intended for laypeople. From our perspective, an “un-explainable” AI is a system that does not afford end-users to comprehend the reasoning behind the decisions and the structure of the model, rendering it challenging for human beings to make assessments of the algorithmic attributes.

There has been growing interest in the social sciences field in exploring the effects of XAI. Glomsrud and colleagues28, for example, presented a comprehensive account of XAI in the context of autonomous ferries. In essence, end-users require explanations that offer a sense of certainty knowing that the autonomous navigation system is behaving at its best, as it should, and in their interests. A large body of experimental studies has offered empirical observations with various XAI delivery methods on cognitive and affective outcomes29 ranging from explanation style variation on perceived fairness30, XAI background variation on perceived friendliness, intelligence, and confidence31, to anthropomorphic variation on trust32. In observational research, the perception of explainability, generally referred to as the extent to which an individual perceives the AI decisions and/or model to be explainable and interpretable, is often examined. From this perspective, Xie and colleagues33 reported that perceived explainability in social media algorithm was associated with AI resistance behaviors such as ignoring algorithmic suggestions. Zhang and colleagues34 reported that perceived explainability in autonomous vehicles was associated with perceptions such as ease of use, usefulness, safety, and intelligence. There is also substantial empirical evidence on the effects of explainability perception on trust and fairness perception16,17,35. In this vein, Cheung and Ho15 further reported that the perception of explainability could be acquired through news media.

Trust in AI

A fundamental factor governing human-human relationships, especially in situations in which knowledge about the other person is limited and control surrendered, is trust. It is also applicable in human-AI interactions because AI has advanced to behave not merely as a tool but more as a social partner36. Conceptually, trust is “a mental state where the trustor holds an expectation towards the trustee that the trustee will perform a specific action that is desirable for achieving a goal” under conditions of risk or uncertainty37, p. 1441; whereas trustworthiness is “the quality in [the trustee] that satisfies this mental state” (p. 1441). While conceptually distinct, one can infer the level of trust from trustworthiness factors because the latter justifies the state of the former. Trust is a, if not the most, critical variable in perception studies on AI. Not only is trust predictive of overcoming resistance to AI38, but it also enhances the quality of human-AI interaction39. It is especially relevant in the AI context because of its distinct nature vis-à-vis other technoscientific innovations, as AI can seemingly operate intelligently on its own. Naturally, a proliferation of research has emerged in the trust in AI scholarship, examining its effects40,41 and determinants42,43,44.

Theoretical underpinnings of trust

In theory, Mayer and colleagues45 delineated three dimensions of trustworthiness in a human trustee, namely ability, referring to “the group of skills, competencies, and characteristics that enable the trustee to influence the domain” (p. 59); benevolence, referring to “the extent to which the intents and motivations of the trustee are aligned with those of the trustor” (p. 59); and integrity, referring to “the degree to which the trustee adheres to a set of principles the trustor finds acceptable” (p. 59). Lee and See46 later conceptualized the trust in automation framework with much of Mayer et al.’s conception of trust as theoretical base. They viewed trust in automation along the dimensions of performance, referring to “the competency or expertise as demonstrated by [the automation’s] ability to achieve the operator’s goals” (p. 59); purpose, referring to “the degree to which the automation is being used within the realm of the designer’s intent” (p. 59); and process, referring to “the degree to which the automation’s algorithms are appropriate for the situation and able to achieve the operator’s goals” (p. 59). In AI perception studies, trust is often operationalized in terms of trustworthiness factors47. We accordingly measured trust variables along these dimensions.

A human factor in trust models

In traditional trust in AI models, researchers have generally viewed trust as a mental state placed exclusively in the AI system. Yet, the trust in AI concept is inherently a complex one that involves more than a single dimension43. Emerging research has found support for the inclusion of human factors. For example, Skaug Sætra48 suggested that trust in AI could involve organizational trust because the technology companies typically assume a central role in the development, monitoring, and upgrading of the AI system. Sheir and colleagues49 similarly suggested that individuals developed trust by evaluating the accountability of entities responsible for algorithmic decisions and failures. A framework of trust for autonomous vehicles grounded in the trustworthiness of various stakeholders such as policymakers, AI developers, and news media outlets was recently identified by Goh and Ho50. Taken together, we contend that it is necessary to examine human factors in trust in AI models.

Notably, Ho and Cheung20 investigated the effectiveness of trust in AI engineers, in which engineers were defined as “experts who engage in programming and coding of the algorithms from its associated artificial intelligence system” (p. 4). They held the view that trust placed in the engineers behind the AI has significance independent of, and on par with, that placed in the AI system. This is because algorithmic biases (i.e., intended and unintended “systemic faults in algorithmic systems that generate unfair discriminations, such as favoring a certain group of users over others”51, p. 105) can often be traced back to engineers through profiles of the assigned engineers, data selected for model training, and values defined in the algorithmic outputs52. In this view, even though trust in AI engineers inherently intertwine with trust in system, the two variables are conceptually distinct. Trust in AI system primarily relates to systemic attributes, whereas trust in AI engineers concerns human attributes. Empirically, Ho and Cheung20 revealed that trust in engineers indirectly shaped behavioral intention through attitude.

Uncertainty reduction and trust in AI engineers

Our primary objective is to examine the effectiveness of explainability perception on trust in AI engineers. While the relationship between explainability and trust in AI system has been rather firmly established 15,16,17, the current body of literature does not illuminate how explainability relates to trust in AI engineers. This appears counterintuitive. Primarily, explainability offers an understanding of the inner workings of the algorithm, through which end-users can infer algorithmic biases. Empirical research has shown that XAI could enhance awareness of algorithmic biases53, and as we noted, these biases can originate from human biases stemming from data selection and value definition encoded into the algorithms. Further, when algorithmic errors take place, a clear understanding of the AI decision-making process may likewise facilitate an attribution of causes. This may afford a sense of reassurance to end-users that the engineers had adhered to ethical and legal guidelines in the development of algorithms. Thus, we set out to examine the effectiveness of explainability perception on trust in AI engineers while controlling for trust in AI system. This analytical approach enables us to examine the effects independent of the conventional conception of trust in AI and allows for observations on the distinct relationship between XAI and trust in AI engineers.

Recent developments in XAI research suggest that explanations operate through an uncertainty reduction process to achieve desirable cognitive and affective outcomes10,11. It is hypothesized in URT that during the initial stage of contact, strangers tend to engage in information seeking behaviors to reduce uncertainty about each other12. A successful reduction results in the development of favorable attitudes. As AI transforms itself to become more of a “human partner” than a technological tool54, the uncertainty reduction perspective offers an overarching theoretical account of how XAI can improve trust. Indeed, research suggests that XAI delivery could improve trust in the ability, benevolence, and integrity dimensions (or performance, purpose, and process) of AI systems55. Venturing beyond, we hypothesize that explainability perception can shape trust in AI engineers’ ability. In URT, uncertainty reduction involves increasing predictability of behaviors that may take place in the interaction. If algorithmic behaviors can be deduced from XAI, it may then act as a platform through which AI engineers demonstrate their understanding of the AI model structure and its output. Especially when confusing algorithmic behaviors are accounted for through XAI delivery, it may reveal, at least from the perspective of the end-user, that engineers had previously anticipated these scenarios. In this sense, XAI may offer a foundation for end-users to form trust in engineers’ ability. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is formulated for examination:

H1: Perceived AI explainability is positively associated with trust in ability.

We contend that explainability perception may play an even more important role in improving trust in AI engineers’ benevolence and integrity. By rendering the algorithms explainable, engineers are able to demonstrate their intention to keep end-users well informed in the algorithmic decision-making process, even at the cost of potentially exposing the system’s limitations. Through XAI, end-users are also made aware that the attribution of causes are more readily available should algorithmic errors occur. Indeed, there has been research identifying transparency and accountability as key dimensions associated with trust in AI technology developers’ integrity50. These considerations enable them to perceive engineers as acting in their interest as well as adhering to appropriate ethical standards in the development and monitoring of algorithms. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are formulated for examination:

H2: Perceived AI explainability is positively associated with trust in benevolence.

H3: Perceived AI explainability is positively associated with trust in integrity.

Trust, attitude, and behavioral acceptance

Another key objective of our investigation is to delve into the downstream effects through various trust dimensions in the public opinion formation process associated with technoscientific acceptance. In Davis’s technology acceptance model (TAM)56, attitude is hypothesized as a key but partial mediator between perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and use intention. Attitude is conceptualized in TAM as a disposition toward the behavior of using the technology, a conception that aligns with well-recognized theories such as the theory of reasoned action57 and the theory of planned behavior58. Still, different conceptualizations exist59. Koenig60, for example, pointed out that attitude has sometimes been treated as an attitude toward the system itself or its associated regulations. This is despite that the strength of the attitude-behavior relationship was reported to be less robust when it had been defined as an evaluation toward the object as opposed to the specific behavior of using the object61. Yet, we conceptualize attitude as an internal evaluation of the AI application. We argue that this approach was necessary, as the technology of interest has not been publicly introduced, thereby rendering it challenging for individuals to accurately evaluate an attitude toward usage behaviors in the absence of such services.

The TAM perspective offers a solid conceptual understanding that places internal evaluations of technology as antecedent to attitude and subsequently acceptance. In theory, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use predict an internal evaluation toward the technology. This establishes a “causal chain connecting system design features to user acceptance”61, p. 16. Indeed, as emerging empirical evidence recognizes the importance of trust in AI perception research43, much TAM research in the AI field incorporates trust constructs alongside usefulness and ease of use perceptions62. Relatedly, Siegrist63 noted that trust could act as a heuristic cue that facilitates cognitive and affective evaluations such as risk and benefit perceptions. Especially in complex technoscientific applications such as AI, trust in engineers may then operate as a heuristic cue that addresses heightened concerns, thereby facilitating more favorable attitudes.

Ho and Cheung20 preliminary demonstrated the predictive value of trust in AI engineers in use intention through attitude. This study, however, has not illuminated the effectiveness of each trust dimension. Rather than treating trust as a composite construct, we propose to examine trust in a segmented approach as we recognize the complexities of the trust in AI concept18. This is, then, an extension of prior works to understand the effectiveness of trust in AI engineers. Not only can this finding contribute to practical communication strategies, but more significantly, it can also advance trust models by offering precise observations on the unique contribution of each trust factor. As this is one of the first attempts to delineate the differential effects of trust dimensions in AI engineers, we raise the following research question:

RQ1: What are the relationships between trust in AI engineers’ dimensions and attitude?

Consistent with established theoretical models such as TAM and the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT)64, we offer a complete understanding of public perceptions by specifying paths to the final endogenous variable of use intention, an indicator of behavioral acceptance. Importantly, extant research suggests that explainability perception could have important implications for behavioral acceptance15,34. As we set out to investigate public perceptions of AI applications, we delve into how attitude shapes use intention of various types of autonomous passenger drones (i.e., drones for tourism; daily commute; and cross-country/city travel). Through this investigation, we are able to observe how favorable the public views a specific passenger drone application. That is, how willing the public is to use each type of autonomous passenger drone. Based on the TAM perspective, supplemented with empirical data that supports the attitude-intention link, the following hypotheses are formulated for examination:

H4: Attitude is positively associated with intention to use autonomous passenger drones for tourism.

H5: Attitude is positively associated with intention to use autonomous passenger drones for daily commute.

H6: Attitude is positively associated with intention to use autonomous passenger drones for cross-country/city travel.

The present study proposes that explainability perception can shape trust in AI engineers, which in turn shapes attitude, and consequently use intention. Various theoretical accounts, primarily URT on the XAI-trust link, as well as public perception research15 have offered theoretical and empirical support to our proposed conceptual model, we thus hypothesize serial mediation effects between explainability perception and behavioral intention. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is formulated for examination:

H7: Trust in AI engineers and attitude serially mediate the relationship between perceived AI explainability and use intention.

Note, that the hypothesized theoretical model includes the covariate of trust in AI system to allow for an isolated examination of trust in AI engineers (See Fig. 1).

Method

Procedure

Prior to data collection, we had obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (IRB ref no.: IRB-2023-275), ensuring all methods carried out in the present study were in accordance with the institution’s guidelines and regulations. Data was collected after obtaining informed consent from the respondents. The data analyzed in this study was a subset of a large-scale public survey conducted to evaluate public opinion on AI-powered drones. Related studies on autonomous passenger drones investigating explainability and trust in engineers in different conceptual angles were published elsewhere15,20.

The present study collected data from 1,002 respondents, a practice consistent with public opinion survey research65,66,67. We commissioned Rakuten Insight, a research firm, to engage in public survey data collection from 28th April, 2023 through 17th May, 2023 in Singapore. Data collection was performed online. Inclusion criteria of respondents included: (1) Singaporean or permanent resident in Singapore, and (2) aged 21 or above. To eliminate confounds, samples were stratified to ensure representativeness according to the latest population distribution in terms of age, gender, and ethnicity. To ensure consistent understanding of the study context, all respondents were presented at the beginning of the survey with a conceptual definition of autonomous passenger drones, defined as “vehicles in the air which can operate fully autonomously with artificial intelligence (AI) technology and without human intervention in executing the flight mission for the purpose of human transportation from location to location,” as well as a brief conceptual definition of AI and an image of an autonomous passenger drone.

Measurements

Perceived AI explainability

Perceived explainability was measured by an adapted three-item 5-point Likert scale15,16 asking respondents to evaluate their perception of explainability in the algorithm of autonomous passenger drones. Higher scores reflected higher levels of perceived explainability.

Trust in ability/benevolence/integrity

Trust in AI engineers’ ability, benevolence, and integrity were measured by three adapted four-item 5-point Likert scales68 asking respondents to evaluate their levels of trust in AI engineers developing autonomous passenger drones in these trustworthiness attributes. A conceptual definition of engineers — “engineers are experts who engage in programming and coding of the algorithms from its associated artificial intelligence (AI) system” — had been provided prior to the measurement in the survey. Higher scores reflected higher levels of trust.

Attitude toward autonomous passenger drones

Attitude was measured by an adapted version of the nine-item 5-point Emerging Technologies Semantic Differential Scale69 asking respondents to evaluate their attitude toward autonomous passenger drones. Four items with low factor loadings (< 0.60) identified in confirmatory factor analysis were removed from the analyses. Higher scores reflected a more positive attitude.

Use intention

Intention to use autonomous passenger drones for tourism/daily commute/cross-country/city travel were measured by three adapted three-item 5-point Likert scales70 asking respondents to evaluate their level of behavioral intention to use autonomous passenger drones across applications. Higher scores reflected higher levels of intention.

Trust in AI system (Control variable)

Trust in AI system was measured by three dimensions of trust factors corresponding to trust in AI engineers’. These dimensions included performance (i.e., ability), purpose (i.e., benevolence), and process (i.e., integrity)46. Each of the dimensions was measured by an adapted four-item 5-point Likert scale71 asking respondents to evaluate their levels of trust in each systemic attribute. The three dimensions were collapsed together to form a second-order latent variable in the analyses as covariate. Higher scores reflected higher levels of trust.

Other control variables

Demographic variables such as gender, age, ethnicity, education level, residential arrangement, marital status etc. were measured. Prior use of civilian drones (e.g., drones not powered by AI) were also measured.

Exact item wording and descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

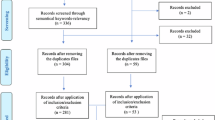

Analysis

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was applied to test the hypothesized model using MPlus 8.372. The SEM approach is well-established in communication and science and technology research for theory testing and refinement15,66,73,74. Following the two-step approach75, a measurement model was estimated to specify the relationships between the observed indicators and latent variables. The measurement model allows for the estimation of overall model fit indices, and thereafter factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variances extracted (AVE). These four indicators provide support for convergent and discriminant validity of the measurements76. Subsequently, a structural model was estimated to specify the relationships between the latent variables to test the hypothesized model.

To address common method biases, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test to evaluate common method variance. The first factor accounted for 42.70% of the variance, which suggests that it is not likely that common method bias is posing substantial influence on our analyses. However, recognizing the insufficiency of the Harman’s test, Podsakoff and colleagues77 suggested conducting confirmatory factor analysis with a method factor specified to load onto all observed variables. We observed that the model with the added method factor did not improve model fit, again suggesting that common method bias did not substantially affect our analyses.

The present analyses followed model fit criteria recommended by Hu and Bentler78 in which the model should present comparative fit index (CFI) above 0.95, 90% confidence interval of the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below 0.06, and the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) below 0.08. The measurement model presented good model fit, χ2/ df = 3.07; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.045, 90% CI = [0.043, 0.048]; SRMR = 0.031. Items presented with low factor loadings (< 0.60) were removed from the attitude semantic differential scale. No error covariances were specified except between the three trust variables. The measurement model presented satisfactory CR and AVE values above 0.70 and 0.50, respectively79. Subsequently, we estimated the structural model based on the hypothesized model. The structural model presented good model fit, χ2/ df = 2.57; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.040, 90% CI = [0.038, 0.041]; SRMR = 0.048. The structural model controlled for demographic variables, prior use of drones, and importantly, trust in AI system, allowing for an isolated examination of trust in AI engineers. A single error covariance within the trust in purpose factor (i.e., trust in AI system; control variable) was specified based on modification indices.

Consequently, indirect effects were estimated to illuminate the effect mechanisms80. The bootstrap method was deployed to estimate standard errors for indirect effects with 5,000 bootstrap samples. This method is widely recognized as an alternative approach to overcome the shortcomings of the Baron and Kenny’s81 causal model approach to mediation analyses, by estimating path coefficients using bootstrap bias-corrected confidence intervals82.

Results

Respondent assessments

Respondents who were unable to pass attention check questions (i.e., two out of three), or complete the survey within a reasonable time frame had been removed. A total of 1,002 respondents were recruited and retained in the analyses. Among this sample, there were 910 Singaporeans (90.8%) and 92 permanent residents (9.2%). Assessments of the respondents’ gender, age, ethnicity, education level, and residential arrangements are presented in Table 2.

Bivariate correlations

Correlational analysis revealed that all variables of interest presented positive and significant correlations, presenting preliminary support to our hypotheses. The zero-order correlation matrix is presented in Table 3.

Structural equation modelling

The structural model accounted for 49.60% of the variance in the final endogenous variable of intention to use autonomous passenger drones for tourism, 44.90% in intention to use for daily commute, and 45.00% in intention to use for cross-country/city travel. In the structural model, the direct relationships between perceived AI explainability and trust in ability (β = 0.15, p < .001), trust in benevolence (β = 0.13, p < .001), and trust in integrity (β = 0.28, p < .001) were significant. Thus, H1 through H3 were supported. Answering RQ1, the direct relationship between trust in ability and attitude was significant (β = 0.27, p < .001), but not for the direct relationships between trust in benevolence (p = .386), trust in integrity (p = .997), and attitude. Subsequently, the direct relationships between attitude and intention to use autonomous passenger drones for tourism (β = 0.25, p < .001), intention to use for daily commute (β = 0.17, p < .001), and intention to use for cross-country/city travel (β = 0.15, p < .001) were significant. Thus, H4 through H6 were supported. Finally, mediation analyses revealed that trust in ability and attitude serially mediated the relationship between perceived AI explainability and intention to use for tourism (B = 0.01, β = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.002, 0.023]), intention to use for daily commute (B = 0.01, β = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.016]), and intention to use for cross-country/city travel (B = 0.01, β = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.014]). The indirect effect through these two latent variables accounted for 6.90% of the total effect between perceived AI explainability and intention to use for tourism, 3.93% between perceived AI explainability and daily commute, and 3.45% between perceived AI explainability and cross-country/city travel, respectively. Trust in benevolence and attitude, as well as trust in integrity and attitude did not serially mediate the relationship between perceived AI explainability and other use intention variables. Thus, H7 was partially supported. Results are presented in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Analyzing trust through different trustworthiness latent factors, our data suggests that explainability perception was effective in shaping all dimensions of trust in AI engineers, even after accounting for trust in system. Our findings reported here firmly extend our understanding of XAI as we observed its effectiveness beyond trust in the AI system. We subsequently observed that only trust in AI engineers’ ability was related to use intention through attitude. Importantly, we identified several serial mediation pathways in which the relationship between perceived explainability and various types of use intention were mediated by trust in ability and, subsequently, attitude. Our theoretical model underscores the value of taking human trust factors into account within the development of public opinion toward AI.

Theoretical implications

We expand our understanding of the relationship between explainability and trust. Not only does our data establish the theoretical robustness of XAI through an uncertainty reduction perspective, but it also extends our knowledge about what XAI can achieve. A great body of empirical work suggests that perceived explainability directly, and indirectly, shaped trust in AI system15,16. This view may be incomplete. When we entered both trust constructs into the model, the effect of explainability perception on trust in AI engineers remained statistically significant. Granted, that the coefficient estimates in our model presented weaker associations than those in the explainability-systemic trust links15, and that trust in AI engineers and attitude only accounted for ~ 3% through ~ 7% in the total effects. We nonetheless argue that the implications for trust in AI engineers remain theoretically robust. When algorithmic errors take place, growing research suggests that the perceptions of errors were often attributed to human entities rather than the AI49,83, indicating that people may be well aware that systemic failures could be traced back to human errors. There is growing salience in this matter as more algorithmic bias issues are being reported in news media e.g84,85. Our data suggests that XAI communication has the potential to mitigate this problem.

By delineating dimensions of trust in AI engineers, we were able to make precise observations on how trust could exert downstream effects on acceptance. It seems clear, however, that the public predominantly relied on trust in the ability aspect. In other words, when engineers were perceived as competent, people tended to hold a favorable view toward the system they had developed. This is concerning. It implies that individuals may be overly reliant on human ability rather than design motivation and ethical conduct. If algorithmic biases are as prevalent as news reports suggest, and that these biases can be traced back to the engineers, one naturally expects people to place significant weight on benevolence and integrity of the engineers. It may be erroneous to assume a competent engineer is necessarily a well intentioned one. We recognize that this may have reflected the conceptualization and thereby operationalization of the attitude construct. In our operational definition, attitude may be more theoretically aligned with the evaluation of functionality of the autonomous passenger drones. A broader attitudinal concept or other variables such as fairness, risk, or benefit perceptions may present different patterns of observations86,87. This may also be a reflection on the differences between cognitive and affective trusts, in which cognitive trust refers to the extent of confidence to depend on the trustor’s competence, and affective trust, which refers to the extent of confidence to depend on the trustor’ care88,89. In this sense, our data may suggest that although explainability could shape both aspects of trust, cognitive trust appeared to be more relevant in determining acceptance of AI, at least at the current stage of technological development. These observations call for more research to investigate the intricate relationships between trust in AI engineers and other cognitive and affective outcomes. We note that the differentiation of trust factors has great potential to advance theorizing on the mechanisms through which AI perceptions are developed. Future research is strongly encouraged to continue analyze trust in this approach.

Practical implications

Emerging research in AI perception has gradually recognized the value of human factors in AI trust models. Montag and colleagues90, for example, reported that trust in human could translate well into trust in AI. We argue that this relationship may be more significant when the human actors behind the AI are explicitly considered. Engineers have considerable influence in determining the what, how, and why of AI applications. Their role in AI will only grow more prominent as AI continues to revolutionize modern society. The application of XAI offers an effective technique to keep engineers in check. Further, we recognize that the principles of XAI should be extended beyond human-AI interaction. For example, communication of intricacies and failures of AI can be presented through public information and news media reporting. Indeed, research has reported that news media could significantly shape attitude of and support for AI87, and that news media and technology developers could play a key role in the introduction of AI technologies50. Our findings inform science communication practitioners that XAI seems to exert greater influence than previously understood. As different individuals perceive information about AI differently91, more attention should be paid to scenarios in which XAI communication may enhance trust in AI system but undermine trust in AI engineers, and vice versa. For example, if XAI communication overwhelmingly reveals limitations of the system, it may facilitate trust in the engineers but, at the same time, undermine systemic trust. In XAI designs, a delicate balance must be struck.

What types of AI applications may benefit more from XAI communication? Venturing beyond previous reports20, we observed that attitude appeared to be more robustly associated with intention to use autonomous passenger drones for touristic purposes, vis-à-vis daily commuting and cross-country/city travelling drones. This may indicate that while the public was, by and large, supportive of the autonomous passenger drone technology, they may be comparatively more conservative when it came to drones that offer longer and more regular journeys. Indeed, these types of transportation options may present greater uncertainty and therefore personal threats. As the data suggests that explainability perception could address uncertainty issues, we encourage relevant stakeholders to actively consider XAI designs that target risk-laden AI applications.

Limitations and future directions

Despite our best intentions, our study comes with several limitations. First, because this is a cross-sectional dataset, we refrain from causality assertions. Second, we recognize that the measurement of explainability may reflect, to a certain extent, efficacy to comprehend AI, rather than a systemic affordance on explainability. The measurement is also plagued by the imaginative nature in responding the survey as autonomous passenger drones are yet to be introduced in Singapore. Third, because Singapore has active plans to introduce passenger drones in recent years, the Singaporean public may have increased levels of awareness, knowledge, and higher expectations. Our findings may not generalize.

Our study presents an extended theoretical understanding of XAI. By offering a snapshot as to how this may play out with trust in AI engineers, our study opens new avenues for future research. For example, how can XAI communication strike the balance between trust in AI system and engineers? What kinds of explanations constitute as “complete?” Where and when should XAI communication take place? Experimental and qualitative research is strongly encouraged to adopt psychological as well as rhetorical and psychological theories to continue theoretical advancement.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined the intricate relationships between perceived AI explainability, trust in AI engineers, attitude, and intention to use various types of autonomous passenger drones. Notably, we found that perceived AI explainability shaped all dimensions of trust in AI engineers, even after controlling for trust in AI system. This indicates that XAI may have broader effects than what the literature currently suggests. We observed that only the trust in ability dimension was associated with attitude and subsequently use intention. The same pattern of observations was made with the serial mediation effects between perceived AI explainability and use intention. Our findings extend theoretical understanding on XAI and call for more research to consider human factors in trust models. Statistically, quantitative researchers are encouraged to study trust and complex latent constructs such as risk and benefit perceptions through a segmented approach with structural equation modelling. Practically, we urge XAI designers and science communicators to consider XAI’s effects on trust in AI engineers, with particular care dedicated to striking that balance between trust in engineers and system.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, subject to compliance with the University’s IRB rules and regulations.

References

Reuters China drone maker EHang starts selling flying taxis on Taobao. Reuters https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/china-drone-maker-ehang-starts-selling-flying-taxis-taobao-2024-03-18/ (2024).

Meade, D. NASA flies drones autonomously for air taxi research, NASA Flies Drones Autonomously for Air Taxi Research. https://www.nasa.gov/aeronautics/nasa-flies-autonomous-drones/

Elshamy, M. Air taxis failed to get certified for the Paris Olympics. There’s still hope for LA 2028. Associated Press https://apnews.com/article/olympics-2024-paris-flying-taxis-82af3b21726dc6ebbc99da076b98d14b (2024).

Cohen, A. & Shaheen, S. Urban air mobility: opportunities and Obstacles. Inst. Transp. Stud. UC Berkeley. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102671-7.10764-X (2021).

Biehle, T. Social sustainable urban air mobility in Europe. Sustainability 14 (15), 9312. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159312 (2022).

Pak, H. et al. Can urban air mobility become reality? Opportunities and challenges of UAM as an innovative mode of transport and DLR contribution to ongoing research. CEAS Aeronaut. J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13272-024-00733-x (2024).

Causa, F., Franzone, A. & Fasano, G. Strategic and tactical path planning for urban air mobility: overview and application to real-world use cases. Drones 7 (1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7010011 (2022).

Bao, L. et al. Whose AI? How different publics think about AI and its social impacts. Comput. Hum. Behav. 130, 107182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107182 (2022).

Shin, D. Explainable algorithms, In: Algorithms, Humans, and Interactions: How Do Algorithms Interact with People? Designing Meaningful AI Experiences, 1st ed., New York: Routledge, 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1201/b23083. (2022).

Jiang, J., Kahai, S. & Yang, M. Who needs explanation and when? Juggling explainable AI and user epistemic uncertainty. Int. J. Hum. -Comput Stud. 165, 102839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2022.102839 (2022).

Liu, B. In AI we trust? Effects of agency locus and transparency on uncertainty reduction in human–AI interaction. J. Comput. -Mediat Commun. 26 (6), 384–402. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab013 (2021).

Berger, C. R. & Calabrese, R. J. Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Hum. Commun. Res. 1 (2), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1975.tb00258.x (1975).

Aquilino, L., Bisconti, P. & Marchetti, A. Trust in AI: Transparency, and uncertainty reduction. Development of a new theoretical framework. In: 2nd Workshop on Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Human-AI Team. (2023).

Leichtmann, B., Humer, C., Hinterreiter, A., Streit, M. & Mara, M. Effects of explainable artificial intelligence on trust and human behavior in a high-risk decision task. Comput. Hum. Behav. 139, 107539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107539 (2023).

Cheung, J. C. & Ho, S. S. Explainable AI and trust: how news media shapes public support for AI-powered autonomous passenger drones. Public. Underst. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625241291192 (2024).

Shin, D. The effects of explainability and causability on perception, trust, and acceptance: implications for explainable AI. Int. J. Hum. -Comput Stud. 146, 102551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102551 (2021).

Shin, D. Why does explainability matter in news analytic systems? Proposing explainable analytic journalism. J. Stud. 22 (8), 8. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1916984 (2021).

Besley, J. C. & Tiffany, L. A. What are you assessing when you measure ‘trust’ in scientists with a direct measure? Public. Underst. Sci. 32 (6), 709–726. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625231161302 (2023).

Bostrom, A. et al. Trust and trustworthy artificial intelligence: A research agenda for AI in the environmental sciences. Risk Anal. 44 (6), 1498–1513. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14245 (2024).

Ho, S. S. & Cheung, J. C. Trust in artificial intelligence, trust in engineers, and news media: factors shaping public perceptions of autonomous drones through UTAUT2. Technol. Soc. 77, 102533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102533 (2024).

Mathew, D. E., Ebem, D. U., Ikegwu, A. C., Ukeoma, P. E. & Dibiaezue, N. F. Recent emerging techniques in explainable artificial intelligence to enhance the interpretable and Understanding of AI models for human. Neural Process. Lett. 57 (1), 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11063-025-11732-2 (2025).

Longo, L. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) 2.0: A manifesto of open challenges and interdisciplinary research directions. Inf. Fusion. 106, 102301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102301 (2024).

Miller, T. Explanation in artificial intelligence: insights from the social sciences. Artif. Intell. 267, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artint.2018.07.007 (2019).

Adadi, A. & Berrada, M. Peeking inside the black-box: A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access. 6, 52138–52160. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2870052 (2018).

Samek, W., Wiegand, T. & Müller, K. R. Explainable artificial intelligence: Understanding, visualizing and interpreting deep learning models. http://arxiv.org/abs/1708.08296 (Accessed 27 May 2024). (2017).

Taffese, W. Z., Zhu, Y. & Chen, G. Explainable AI based slip prediction of steel-UHPC interface connected by shear studs. Expert Syst. Appl. 259, 125293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125293 (2025).

Gunning, D. et al. XAI—Explainable artificial intelligence. Sci. Robot. 4 (37), 37. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.aay7120 (2019).

Glomsrud, J. A., Ødegårdstuen, A., St., A. L., Clair & Smogeli, Ø. Trustworthy versus explainable AI in autonomous vessels. In: Proceedings of the International Seminar on Safety and Security of Autonomous Vessels (ISSAV) and European STAMP Workshop and Conference (ESWC) 2019 O. Alejandro Valdez Banda, P. Kujala, S. Hirdaris, and S. Basnet, Eds., 37–47. https://doi.org/10.2478/9788395669606-004 (Sciendo, 2020).

Laato, S., Tiainen, M., Najmul, A. K. M., Islam & Mäntymäki, M. How to explain AI systems to end users: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Internet Res. 32 (7), 7. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-08-2021-0600 (2022).

Shulner-Tal, A., Kuflik, T. & Kliger, D. Fairness, explainability and in-between: Understanding the impact of different explanation methods on non-expert users’ perceptions of fairness toward an algorithmic system. Ethics Inf. Technol. 24 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-022-09623-4 (2022).

[31], U. et al. The who in XAI: How AI background shapes perceptions of AI explanations. In: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1145/3613904.3642474 (2024).

Shin, D. The perception of humanness in conversational journalism: an algorithmic information-processing perspective. New. Media Soc. 24 (12), 2680–2704. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444821993801 (2022).

Xie, X., Du, Y. & Bai, Q. Why do people resist algorithms? From the perspective of short video usage motivations. Front. Psychol. 13, 941640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.941640 (2022).

Zhang, T., Li, W., Huang, W. & Ma, L. Critical roles of explainability in shaping perception, trust, and acceptance of autonomous vehicles. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 100, 103568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2024.103568 (2024).

Shulner-Tal, A., Kuflik, T., Kliger, D. & Mancini, A. Who made that decision and why? Users’ perceptions of human versus AI decision-making and the power of explainable-AI. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2024.2348843 (2024).

Valori, I., Jung, M. M. & Fairhurst, M. T. Social touch to build trust: A systematic review of technology-mediated and unmediated interactions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 153, 108121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108121 (2024).

Chen, M. Trust and trust-engineering in artificial intelligence research: theory and praxis. Philos. Technol. 34 (4), 1429–1447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00465-4 (2021).

Gillath, O. et al. Attachment and trust in artificial intelligence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 115, 106607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106607 (2021).

Klingbeil, A., Grützner, C. & Schreck, P. Trust and reliance on AI — An experimental study on the extent and costs of overreliance on AI. Comput. Hum. Behav. 160, 108352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108352 (2024).

Choung, H., David, P. & Ross, A. Trust in AI and its role in the acceptance of AI technologies. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 39 (9), 1727–1739. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2050543 (2023).

Kerstan, S., Bienefeld, N. & Grote, G. Choosing human over AI doctors? How comparative trust associations and knowledge relate to risk and benefit perceptions of AI in healthcare. Risk Anal. 44 (4), 939–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.14216 (2024).

Bach, T. A., Khan, A., Hallock, H., Beltrão, G. & Sousa, S. A systematic literature review of user trust in AI-enabled systems: an HCI perspective. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 40 (5), 1251–1266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2138826 (2024).

Kaplan, A. D., Kessler, T. T., Brill, J. C. & Hancock, P. A. Trust in artificial intelligence: Meta-analytic findings. Hum. Factors. 65 (2), 337–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187208211013988 (2023).

Wintterlin, F. et al. Predicting public trust in science: the role of basic orientations toward science, perceived trustworthiness of scientists, and experiences with science. Front. Commun. 6, 822757. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.822757 (2022).

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H. & Schoorman, F. D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manage. Rev. 20 (3), 3. https://doi.org/10.2307/258792 (1995).

Lee, J. D. & See, K. A. Trust in automation: designing for appropriate reliance. Hum. Factors. 46 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1518/hfes.46.1.50_30392 (2004).

Leschanowsky, A., Rech, S., Popp, B. & Bäckström, T. Evaluating privacy, security, and trust perceptions in conversational AI: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 159, 108344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108344 (2024).

H. Skaug Sætra, A machine’s ethos? An inquiry into artificial ethos and trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 153, 108108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108108 (2024).

Sheir, S., Manzini, A., Smith, H. & Ives, J. Adaptable robots, ethics, and trust: a qualitative and philosophical exploration of the individual experience of trustworthy AI. AI Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-01938-8 (2024).

Goh, T. J. & Ho, S. S. Trustworthiness of policymakers, technology developers, and media organizations involved in introducing AI for autonomous vehicles: A public perspective. Sci. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470241248169 (2024).

Shin, D. Algorithmic bias, In: Algorithms, Humans, and Interactions: How Do Algorithms Interact with People? Designing Meaningful AI Experiences, 1st ed., New York: Routledge, 103–125. https://doi.org/10.1201/b23083. (2022).

Howard, A. & Borenstein, J. The ugly truth about ourselves and our robot creations: the problem of bias and social inequity. Sci. Eng. Ethics. 24 (5), 1521–1536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9975-2 (2018).

Chuan, C. H., Sun, R., Tian, S. & Tsai, W. H. S. EXplainable artificial intelligence (XAI) for facilitating recognition of algorithmic bias: an experiment from imposed users’ perspectives. Telemat Inf. 91, 102135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2024.102135 (2024).

Lyons, J. B., Hamdan, I. & Vo, T. Q. Explanations and trust: what happens to trust when a robot partner does something unexpected? Comput. Hum. Behav. 138, 107473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107473 (2023).

Kollerup, N. K., Wester, J. & Skov, M. B. and N. Van Berkel, How can I signal you to trust me: Investigating AI trust signalling in clinical self-assessments, In: Designing Interactive Systems Conference 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1145/3643834.3661612 (IT University of Copenhagen Denmark: ACM, 2024).

Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 13 (3), 319. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Fishbein, M. & Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. In: Addison-Wesley Series in Social Psychology (Addison-Wesley, 1975).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50 (2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T (1991).

Cugurullo, F. & Acheampong, R. A. Fear of AI: an inquiry into the adoption of autonomous cars in spite of fear, and a theoretical framework for the study of artificial intelligence technology acceptance. AI Soc. 39 (4), 1569–1584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01598-6 (2024).

Koenig, P. D. Attitudes toward artificial intelligence: combining three theoretical perspectives on technology acceptance. AI Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-01987-z (2024).

Davis, F. D. & Granić, A. The technology acceptance model: 30 years of TAM. In: Human–Computer Interaction Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing, doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45274-2. (2024).

Ismatullaev, U. V. U. & Kim, S. H. Review of the factors affecting acceptance of AI-infused systems. Hum. Factors. 66 (1), 126–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187208211064707 (2024).

Siegrist, M. Trust and risk perception: A critical review of the literature. Risk Anal. 41 (3), 480–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13325 (2021).

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B. & Davis, F. D. User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 27 (3), 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540 (2003).

Choi, D. H., Yoo, W., Noh, G. Y. & Park, K. The impact of social media on risk perceptions during the MERS outbreak in South Korea. Comput. Hum. Behav. 72, 422–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.004 (2017).

Liao, Y., Ho, S. S. & Yang, X. Motivators of pro-environmental behavior: examining the underlying processes in the influence of presumed media influence model. Sci. Commun. 38 (1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547015616256 (2016).

Pleger, L. E., Guirguis, K. & Mertes, A. Making public concerns tangible: an empirical study of German and UK citizens’ perception of data protection and data security. Comput. Hum. Behav. 122, 106830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106830 (2021).

Mayer, R. C. & Davis, J. H. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 84 (1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.1.123 (1999).

Ajani, T. & Stork, E. Developing a semantic differential scale for measuring users’ attitudes toward sensor-based decision support technologies for the environment. J. Inf. Syst. Appl. Res. 7 (1), 16–22 (2014).

Gansser, O. A. & Reich, C. S. A new acceptance model for artificial intelligence with extensions to UTAUT2: an empirical study in three segments of application. Technol. Soc. 65, 101535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101535 (2021).

Jensen, T. et al. Anticipated emotions in initial trust evaluations of a drone system based on performance and process information. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 36 (4), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2019.1642616 (2020).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide 8th edn (Muthén & Muthén, 1998).

Pang, H. & Zhang, K. How multidimensional benefits determine cumulative satisfaction and eWOM engagement on mobile social media: reconciling motivation and expectation disconfirmation perspectives. Telemat Inf. 93, 102174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2024.102174 (2024).

Pang, H. & Wang, Y. Deciphering dynamic effects of mobile app addiction, privacy concern and cognitive overload on subjective well-being and academic expectancy: the pivotal function of perceived technostress. Technol. Soc. 81, 102861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2025.102861 (2025).

Anderson, J. C. & Gerbing, D. W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 103 (3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411 (1988).

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S. & Wang, L. C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y (2023).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 (2003).

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ Model. Multidiscip J. 6 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Cheung, G. W. & Wang, C. Current approaches for assessing convergent and discriminant validity with SEM: Issues and solutions. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2017 (1), 12706. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2017.12706abstract (2017).

Holbert, R. L. & Stephenson, M. T. The importance of indirect effects in media effects research: testing for mediation in structural equation modeling. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media. 47 (4), 556–572. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4704_5 (2003).

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 (1986).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36 (4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553 (2004).

Isaac, M. S., Jen-Hui Wang, R., Napper, L. E. & Marsh, J. K. To err is human: Bias salience can help overcome resistance to medical AI. Comput. Hum. Behav. 161, 108402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108402 (2024).

Tiku, N. & Chen, S. Y. What AI thinks a beautiful woman looks like: mostly white and thin. Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/interactive/2024/ai-bias-beautiful-women-ugly-images/ (2024).

Pressly, L. & Escribano, E. Domestic violence: Spain police algorithm said Lina was at ‘medium’ risk. Then she was killed. BBC News https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/clyw7g4zxwzo (2025).

Brell, T., Philipsen, R. & Ziefle, M. sCARy! Risk perceptions in autonomous driving: the influence of experience on perceived benefits and barriers. Risk Anal. 39 (2), 342–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13190 (2019).

Brewer, P. R., Bingaman, J., Paintsil, A., Wilson, D. C. & Dawson, W. Media use, interpersonal communication, and attitudes toward artificial intelligence. Sci. Commun. 44 (5), 559–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/10755470221130307 (2022).

Johnson, D. & Grayson, K. Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. J. Bus. Res. 58 (4), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00140-1 (2005).

Johnson-George, C. & Swap, W. C. Measurement of specific interpersonal trust: construction and validation of a scale to assess trust in a specific other. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 43 (6), 1306–1317. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.6.1306 (1982).

Montag, C., Becker, B. & Li, B. J. On trust in humans and trust in artificial intelligence: A study with samples from Singapore and Germany extending recent research. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2 (2), 100070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2024.100070 (2024).

Deng, R. & Ahmed, S. Perceptions and paradigms: an analysis of AI framing in trending social media news. Technol. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2025.102858 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Research Foundation, Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. conceptualized the study, conducted data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. S.H. conceptualized the study, acquired funding, and supervised the manuscript write-up.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, J.C., Ho, S.S. The effectiveness of explainable AI on human factors in trust models. Sci Rep 15, 23337 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04189-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04189-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hallucination to truth: a review of fact-checking and factuality evaluation in large language models

Artificial Intelligence Review (2026)