Abstract

Early extracellular water (ECW) alterations might act as preclinical markers of disease, as these changes often occur in early stages. Quantifying this relationship could provide insights into clinical practice and evaluating nutritional interventions in personalized health. This study examined the association between extracellular water/total body water ratio (ECW/TBW) and all-cause mortality in adults using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1999–2004) and mortality follow-up until 2019. Among 6338 participants, 307 died over 20 years. Kaplan–Meier curves showed higher mortality with elevated ECW/TBW (log-rank P = 0.038). Multivariable Cox models indicated the highest ECW/TBW quartile (≥ 44.6%) had an adjusted HR of 1.60 (95% CI 1.15–2.23; P = 0.005). Restricted cubic spline analysis revealed a J-shaped non-linear relationship (P = 0.009), with an inflection point at 42.4%. Piecewise regression showed an adjusted HR of 1.10 (95% CI 1.05–1.15; P < 0.001) for ECW/TBW ≥ 42.4%. Specifically, each one-unit increase in ECW/TBW beyond the inflection point was associated with a 10% higher risk of all-cause mortality. This suggests ECW/TBW could be a useful marker for risk assessment and guiding interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Early alterations in body water distribution may occur in the initial stages of disease progression, and extracellular water (ECW) has been proposed as a potential preclinical disease marker. Advances in bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) have facilitated the quantification of body fluids, including total body water (TBW) and fat-free mass, making such assessments more feasible in both research and clinical settings1,2. As a result, the ECW/TBW has gained recognition as a clinically relevant indicator of fluid distribution3,4.

Numerous studies have explored the relationship between body water distribution and health outcomes across diverse patient populations. For instance, research has demonstrated that in patients with cancer—including gastrointestinal cancer, cancer cachexia, and cancer-related sarcopenia—a higher ECW/TBW ratio is associated with reduced survival rates2,5,6. Studies conducted among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease7, cardiovascular diseases8, acute heart failure9, renal diseases10, and those undergoing peritoneal dialysis11 and hemodialysis12,13 have also identified a significant association between fluid imbalance and poor prognosis. A study on the appendicular extracellular-to-intracellular water ratio (AE/I) and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly individuals in Japan found that AE/I was positively associated with all-cause mortality and could serve as a predictive marker for early death in this population14. Consistent with these findings, two studies on COVID-19 patients reported that an elevated ECW/TBW ratio was associated with increased mortality rates, establishing ECW/TBW as a significant predictor of mortality15,16. Collectively, these studies suggest that a higher ECW/TBW ratio is linked to greater disease severity and a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality. However, the precise quantitative relationship between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality risk in the general population remains unclear.

To address this knowledge gap, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a large and nationally representative study of the U.S. population, provides a unique research opportunity. By integrating comprehensive demographic, clinical, biochemical, and BIA-derived data, NHANES facilitates robust statistical analyses and an in-depth examination of ECW/TBW in relation to key health indicators while accounting for important confounders17,18.

In this study, we demonstrate that a higher ECW/TBW ratio is significantly associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality in the general population, with an inflection point of 42.4%. A deeper understanding of this relationship may provide valuable quantitative insights for early detection, individualized ECW/TBW interventions, and improved health management strategies.

Materials and methods

Data source

We utilized a cohort from the United States, the NHANES, by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, has been conducting 2-year cycles since 1999 to assess the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population19,20. NHANES uses a complex, stratified, multistage probability sampling method in each survey to select a nationally representative sample. The survey encompasses two components: household interviews and medical examinations conducted at a Mobile Examination Center (MEC)21. The data from NHANES collected between 1999 and 2004, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Data collection included in-home interviews, standardized physical examinations, and laboratory tests performed at the MEC.

Standard protocol approval, registration, and patient consent

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The NHANES study protocols adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki and have been ethically approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), with all participants providing written informed consent22. Our secondary analysis followed the STROBE guidelines for cohort studies, and did not require additional institutional review board approval23. Detailed information regarding NHANES’ methodology and ethics is available on the CDC and NCHS website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

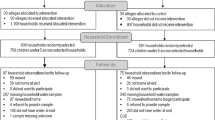

Study design and population

For this study, we included participants aged 18 years or older with complete and valid body composition measurements. Exclusion criteria included individuals under 18 years of age, pregnant women, participants with lacking essential body composition information, and those missing data on all-cause mortality. Figure 1 illustrates the detailed participant enrollment process and the final analytic sample.

Ascertainment of all-cause mortality

Mortality data and causes of death were obtained by linking the cohort database to the CDC’s National Death Index as of December 31, 2019. All-cause mortality was defined as death from any cause24. The follow-up period for each participant was calculated from the date of MEC testing to the date of death or the end of the follow-up period (December 31, 2019).

Assessment of ECW/TBW

ECW and TBW data were collected during MEC testing using the HYDRA ECW/ICW Bio-Impedance Spectrum Analyzer (Model 4200) manufactured by Xitron Technologies, Inc. (San Diego, California). These assessments were conducted by trained health technicians following standardized protocols detailed in the Body Composition Procedures Manual available on the NHANES website25. BIA is a non-invasive method for assessing body composition with significant clinical potential. It accurately determines body composition by emitting electrical signals and measuring resistance across a broad spectrum of frequencies26,27,28,29,30. Among various BIA-derived parameters, ECW/TBW serves as a key indicator of volume status, expressed as ECW-to-TBW ratio3,4.

Definitions of other covariates

Covariates were selected based on established clinical relevance and previous research findings11,14,31,32. They included the following:

-

Sociodemographic factors: Age, sex, marital status (married, living with a partner, or living alone), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, or other races), educational level (< 9 years, 9–12 years, or > 12 years), and family income. Family income was categorized as low (poverty income ratio [PIR] ≤ 1.3), medium (1.3 < PIR ≤ 3.5), or high (PIR > 3.5)21.

-

Lifestyle factors: Smoking Status: Never (fewer than 100 cigarettes smoked in a lifetime), former (quit smoking after smoking ≥ 100 cigarettes), and current21. Drinking Status: Defined by consuming ≥ 12 alcoholic drinks in any given year33. Physical Activity: Sedentary, moderate (≥ 10 min of light to moderate exercise in the past 30 days), or vigorous (≥ 10 min of heavy exercise in the past 30 days)21.

-

Clinical conditions: Hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and coronary heart disease, each determined by self-reported physician diagnosis.

-

Anthropometric measures: Body Mass Index (BMI): Computed as weight (kg) / height (m)2.

-

Laboratory measurements: Albumin and Creatinine: Analyzed using a Hitachi Model 917 multichannel analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN)34. C-Reactive Protein (CRP): Measured by latex-enhanced nephelometry on a Dade Behring Nephelometer II Analyzer (BNII)35.

Statistical analysis

In accordance with the complex sampling design of NHANES, our analysis incorporated sample weights, clustering, and stratification. Following NHANES guidelines for survey sample weights, we applied MEC weights. The sampling weights were calculated as follows: weights for 1999–2002 were assigned as two-thirds of the 4-year MEC weight, while weights for 2003–2004 were one-third of the 2-year MEC weight.

Categorical variables were presented as unweighted counts (weighted percentages), whereas continuous variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR). Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables, while regression analyses were applied for continuous variables. Potential multicollinearity among covariates was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), with VIF ≥ 5 indicating significant multicollinearity. Additionally, multiple imputation was applied for covariates with missing values.

The KM method was employed to estimate survival rates, and the log-rank test was used to assess differences between groups. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were utilized to estimate HRs and 95% CIs for the association between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality. For continuous variables, the HR represents the relative risk increase per unit change in the variable compared to a reference value. For categorical variables, the HR was computed relative to the baseline category (Quartiles ECW/TBW < 44.6%). Three models were constructed:

-

Model 1: Adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education level, and family income) and NHANES cycle.

-

Model 2: Further adjusted for lifestyle factors (smoking status, drinking status, and physical activity).

-

Model 3: Fully adjusted for all covariates, on the basis of model 2, further including hypertension, diabetes, cancers, coronary heart disease, BMI, creatinine, CRP, and albumin.

Furthermore, we employed restricted cubic spline models to construct HR curves, exploring potential non-linear relationships between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality and analyzing the association threshold between ECW/TBW and mortality risk. The bootstrap resampling method was used to determine inflection points.

Additionally, fully adjusted, complex sampling-weighted subgroup analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazards models to examine associations stratified by key variables, including age (< 35 or ≥ 35 years), gender (male vs. female), marital status (married or living with a partner vs. living alone), education level (< 9 vs. 9-12 vs. > 12 years), family income (low vs. medium vs. high), smoking status (never smoker vs. former smoker vs. current smoker), drinking status (drinker vs. non-drinker), physical activity (sedentary vs. moderate vs. vigorous), comorbid hypertension (yes vs. no), diabetes (yes vs. no), cancer (yes vs. no), BMI (< 25.0 vs. ≥ 25.0 kg/m2), creatinine levels (< 75.0 vs. ≥ 75.0 umol/L), CRP (< 0.15 vs. ≥ 0.15 mg/dL), and albumin (< 40 vs. ≥ 40 g/L). Likelihood ratio testing was conducted to assess interactions among subgroups, and results were visualized using a forest plot.

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses. First, to address potential reverse causality bias, we repeated the analyses after excluding deaths that occurred within the first 2 years of follow-up. Second, we performed the same analyses after excluding participants who had cancer at baseline. Third, an E-value was computed to estimate the potential effect of unmeasured confounders.

All analyses were carried out using R software (version 4.2.1; http://www.Rproject.org), the R survey package (version 4.1-1), and Free Statistics software (version 2.1; Beijing Free Clinical Medical Technology Co., Ltd.). A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed from November and December 2024.

Results

Study population

Of the 31,126 participants of the NHANES 1999–2004, 24,788 were excluded for the following reasons:

-

Under 18 years of age (n = 14,065);

-

Pregnancy (n = 927);

-

Missing ECW/TBW data (n = 9791);

-

Missing all-cause mortality data (n = 5).

Thus, 6338 participants were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics

During the 20-year follow-up, 307 (4.64%) all-cause mortality occurred. Among these, malignant neoplasms (cancer mortality) 84 (1.32%), diseases of heart (cvd mortality) 55 (0.82%), and non-specific mortality including diabetes mellitus 14 (0.25%), cerebrovascular diseases 13 (0.20%), chronic lower respiratory diseases 7 (0.11%), nephrotic syndrome 4 (0.04%), influenza and pneumonia 3 (0.05%), Alzheimer’s disease 0 (0%), accidents (unintentional injuries) 41 (0.68%), and all other causes (residual) 86 (1.4%) (Table S1).

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the 6338 study participants according to their ECW/TBW quartiles. Extrapolated to the national level, these results are representative of about 97,627,499 individuals in the U.S. The mean (SD) age of the study participants was 31.4 (10.1) years, and 3,279 (51.1%) individuals were male. The median ECW/TBW was 42.4 (40.4, 44.6)%. Individuals who with a high ECW/TBW often tended to be older (32.5 [10.6] y versus 29.6 [9.5] y, respectively); more often female (1366 [85.8%] versus 203 [11%], respectively); and more likely to be married or living with a partner (801 [62%] versus 706 [55.8%], respectively). They were also more frequently non-Hispanic white (776 [74.1%] versus 518 [58.9%], respectively). They tended to have a higher incidence of diabetes (60 [3.2%] versus 19 [1.2%], respectively) and cancers (53 [4.8%] versus 12 [1.1%], respectively). Higher ECW/TBW was associated with higher C-reactive protein (0.2 [0.0, 0.4] mg/dL versus 0.1 [0.0, 0.3] mg/dL, respectively), and lower BMI (25.9 [6.5] kg/m2 versus 27.8 [5.3] kg/m2, respectively), creatinine (61.7 [24.5] umol/L versus 81.8 [27.4] umol/L, respectively), and albumin levels (43.0 [3.4] g/L versus 45.3 [3.2] g/L, respectively). In addition, individuals who with a low ECW/TBW often tended to engage in vigorous physical activity (837 [53.3%] versus 566 [37.4%], respectively).

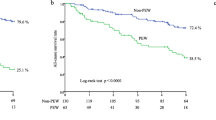

Kaplan–Meier curves for all-cause mortality

KM survival curves for all-cause mortality showed that participants in the higher ECW/TBW group (Q4, Quartiles ECW/TBW ≥ 44.6%) had lower survival ( log -rank P < 0.038) (Fig. 2). KM survival curves for male/female all-cause mortality and KM survival curves for cancer mortality / non-specific mortality showed the same trend, as shown in Supplementary Figure S2a and S2b.

Relationship between ECW/TBW and mortality

The univariate Cox analysis showed that a higher ECW/TBW was significantly associated with elevated risks of all-cause death (HR of 1.05, 95%CI 1.00–1.10, P < 0.049). A higher ECW/TBW was independently associated with elevated risks of all-cause death even after adjustment for age, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, education level, family income, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, physical activity, hypertension, diabetes, cancers, coronary heart disease, BMI and creatinine (adjusted HR of 1.05, 95% CI 1.00–1.10, P = 0.041). Compared to participants with lower ECW/TBW (< 44.6%, Quartiles), those with upper quartile of ECW/TBW (≥ 44.6%, Q4) had an adjusted HR of 1.60 (95% CI 1.15–2.23, P = 0.005) for all- cause mortality. The risk of all-cause death increased by 60% for those with ECW/TBW more than 44.6% (Table 2). Hazard ratios of cancer / cvd / non-specific mortality by ECW/TBW were shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Non-linear relationship between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality

To investigate the potential non-linear relationship between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality, we performed a complex sampling-weighted Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) analysis using an ECW/TBW value of 42.4% as the reference point. The statistical analysis demonstrated a significant overall association (P < 0.001) and a notable non-linear trend (P = 0.009), indicating a strong non-linear relationship between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality risk. The resulting curve exhibited a J-shape: the risk remained stable before the reference point, while the risk of all-cause mortality rose with increasing ECW/TBW after the reference point (Fig. 3). Association between ECW/TBW and cancer / cvd / non-specific mortality by RCS were shown in Supplementary Figure S3.

Association between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality by restricted cubic spline (RCS). The association between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality exhibited a J-Shaped curve (P = 0.009). The solid curved line represents the estimates for the association of ECW/TBW with mortality, and shading, the 95% CI. ECW, extracellular water; ECW/TBW, extracellular water/total body water ratio; TBW, total body water.

In a subsequent threshold (two-piecewise) analysis, the HR for all-cause mortality was 1.10 (95% CI 1.05–1.15, P < 0.001) for ECW/TBW values ≥ 42.4%, indicating that the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 10% for every one-unit increase in ECW/TBW. However, no significant association was observed between the extracellular water-to-total body water ratio and all-cause mortality in participants with ECW/TBW values < 42.4% (Table 3). Threshold effect analysis of the relationship of ECW/TBW with cancer / cvd / non-specific mortality was shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Stratified analyses based on variables

Stratified analyses were conducted to evaluate potential effect modifiers in the relationship between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figure S1). Subgroup analyses were conducted on samples categorized by age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, hypertension, and diabetes. No significant interactions were detected across any subgroups (P > 0.05), indicating that the positive association between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality was largely consistent across these factors. Additionally, when accounting for multiple testing, a p-value of less than 0.05 for the interaction with age may not represent statistical significance.

The relationship between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality according to basic features. Except for the stratification component itself, each stratification factor was adjusted for all other variables, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol drinking status, hypertension, diabetes, respectively. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the stability of association results. The association between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality risk is shown in Tables 2 and 4. The significant association remained, on the one hand, after excluding deaths that occurred within 2 years of follow-up, on the other hand, after excluding participants who had cancer (P < 0.05) (Table 4). The E-value for this association was 2.58 (95% CI 1.57), indicating that a considerable unmeasured confounder would be required to negate these observed effect estimates. Thus, the observed associations appear robust to potential biases (Supplementary Figure S4).

Discussion

The findings of this cohort study demonstrate that a higher ECW/TBW ratio is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality. Overall, an increase of one-unit in ECW/TBW was associated with a 5% increase in the risk of all-cause mortality. Subsequent analyses revealed a J-shaped relationship between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality, with an inflection point at approximately 42.4%. Below this inflection point, the association between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality was not significant; however, beyond the inflection point, the risk of mortality increased sharply with rising ECW/TBW values. Specifically, each one-unit increase in ECW/TBW beyond the inflection point was associated with a 10% higher risk of all-cause mortality. Moreover, individuals with an ECW/TBW greater than 44.6% had a 60% higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to those with an ECW/TBW less than or equal to 44.6%.

The association between ECW/TBW and mortality rates is both epidemiologically and clinically plausible. From an epidemiological perspective, elevated ECW/TBW has been strongly linked to an increased risk of cancer, hemodialysis, kidney diseases, and cardiovascular diseases7,8,12,36,37, which are major contributors to all-cause mortality. Interestingly, our study revealed that the association between ECW/TBW and non-specific mortality (ECW/TBW ≥ 42.4%, HR of 1.14, 95% CI 1.03–1.25, P = 0.010) was more pronounced than the association with deaths caused by malignant neoplasms or heart diseases. This discrepancy might be attributed to the limited sample size for these specific conditions.

From a clinical perspective, higher ECW/TBW levels are indicative of individual hydration status4, nutritional status13,38, and inflammation levels14,39. Nutritional deficiencies can compromise the integrity of cell membranes, leading to a reduction in intracellular water and a relative increase in extracellular water40. Additionally, decreased protein synthesis and increased protein breakdown further deplete intracellular water while drawing more water into the extracellular space13. Inflammation also plays a role by increasing vascular permeability, causing fluid to leak into the interstitial spaces and augmenting extracellular water41. Edema and fluid overload further elevate the ECW/TBW levels. Collectively, these mechanisms contribute to an increase in the ECW/TBW. These factors are known to play pivotal roles in the onset and progression of various diseases38,42, which might be the leading causes of all-cause mortality.

Water is the cornerstone of life on Earth and a major component of the human body, playing a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis43,44. A healthy human body typically consists of 50% to 70% water, which is essential for transporting nutrients to cells and expelling waste, highlighting its indispensable role in bodily functions28. Generally, approximately 33% of TBW resides outside the cells, while the remaining 67% is intracellular. Any increase in extracellular osmolarity draws fluid out of the cells, resulting in an expansion of ECW45. The measurement of intracellular and extracellular water can reflect the functional status of tissues and provide insights into the physiological state of human cells.

This study highlights that ECW/TBW serves as an important biomarker for assessing hydration status, nutritional status, and levels of inflammation-factors that play pivotal roles in the epidemiology of numerous diseases. BIA is widely recognized for its speed, non-invasiveness, reproducibility, ease of use, and safety in body composition assessment6,46. These advantages make BIA a practical and accessible tool for widespread use in clinical and research settings47. As an important clinical index to evaluate body composition, ECW/TBW has a normal range of 35.6–40.3%32. Monitoring ECW/TBW might facilitate a deeper understanding of disease progression, predicts patient outcomes, and offers opportunities for more personalized treatment and management strategies. Multiple strategies may help reduce ECW/TBW. (1) Sodium restriction: A high-salt diet elevates extracellular osmotic pressure, driving water from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment and increasing ECW/TBW. Reducing salt intake can lower this osmotic gradient, diminishing extracellular fluid volume48. (2) Weight management: Lowering body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference is typically accompanied by beneficial shifts in body composition, potentially reducing ECW/TBW49. (3) Exercise and physical activity: In individuals with abdominal obesity, increasing physical activity may improve metabolic parameters and redistribute fluid, ultimately decreasing extracellular water48. (4) Nutritional and inflammatory status: Nutritional support (e.g., protein supplementation, optimized caloric intake) combined with anti-inflammatory therapy (e.g., IL-6 inhibitors) has been shown in clinical trials to reduce ECW/TBW and improve survival rates50,51. Addressing these factors under medical supervision could help optimize fluid balance.

While this study has several strengths, including a comprehensive analysis of a nationally representative sample, long-term follow-up, and careful adjustment for various confounding factors, some limitations should be acknowledged.

First, although we employed multivariable Cox proportional hazards models and performed extensive subgroup and sensitivity analyses, residual confounding cannot be entirely ruled out. NHANES data capture a wide range of variables, but not all potential confounders (e.g., over-the-counter medication use or acute illness) may be accounted for. Second, ECW/TBW data were only collected in NHANES from 1999 to 2004, restricting our ability to use data from other NHANES cycles for further validation. Third, although BIA measurements were performed using standardized protocols, specific conditions such as fasting state, bladder fullness, time of day, and recent physical activity were not fully controlled or documented. Fourth, a one-time measurement of ECW/TBW was used in this study. Future research should consider serial measurements to strengthen the robustness and reliability of the analysis. Fifth, this study focused solely on all-cause mortality, and disease-specific mortality was not fully investigated due to the small sample sizes for specific conditions. Finally, further research is warranted to validate the application of ECW/TBW as a population-level screening tool. As this study was conducted in a U.S. population, investigating the association between ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality in other populations would enhance the generalizability of these findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this national cohort study identified a J-shaped relationship between the ECW/TBW and all-cause mortality risk among U.S. adults, with a critical inflection point at approximately 42.4%. These findings provide strong evidence that ECW/TBW may serve as a non-invasive and easily obtainable screening tool for estimating mortality risk and identifying high-risk individuals. This novel concept has the potential to be integrated into public health strategies for nutritional guidance and health management in the general population.

Data availability

The data used in this study are publicly available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) NHANES website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/. Researchers can access the dataset following the NHANES data usage guidelines.

Abbreviations

- BIA:

-

Bioelectrical impedance analysis

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- ECW:

-

Extracellular water

- ECW/TBW:

-

Extracellular water/total body water ratio

- HD:

-

Hemodialysis

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- KM:

-

Kaplan–Meier

- MEC:

-

Mobile Examination Center

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Procedure Manuals. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BODY COMPOSITION PROCEDURES MANUAL. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/1999/manuals/bc.pdf

Ge, Y. Z. et al. Extracellular water to total body water ratio predicts survival in cancer patients with sarcopenia: A multi-center cohort study. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 19, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-022-00667-3 (2022).

Zhao, W. et al. Association of differential body water composition by sex, measured using BIA, with survival in a real-world lung cancer cohort. Nutrition 103–104, 111804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2022.111804 (2022).

Chung, Y. J., Lee, G. R., Kim, H. S. & Kim, E. Y. Effect of rigorous fluid management using monitoring of ECW ratio by bioelectrical impedance analysis in critically ill postoperative patients: A prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled study. Clin. Nutr. 43, 2164–2176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2024.07.040 (2024).

Katsura, N., Yamashita, M. & Ishihara, T. Extracellular water to total body water ratio may mediate the association between phase angle and mortality in patients with cancer cachexia: A single-center, retrospective study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 46, 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.10.009 (2021).

Yoon, S. L., Grundmann, O., Williams, J. J., Gordan, L. & George, T. J. Jr. Body composition changes differ by gender in stomach, colorectal, and biliary cancer patients with cachexia: Results from a pilot study. Cancer Med. 7, 3695–3703. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1665 (2018).

Faisy, C., Rabbat, A., Kouchakji, B. & Laaban, J. P. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in estimating nutritional status and outcome of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 26, 518–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001340051198 (2000).

Tsai, Y. C. et al. Association of fluid overload with cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality in stages 4 and 5 CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 39–46. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.03610414 (2015).

Lee, K. S., Kim, J. H., Kang, J., Cho, H. J. & Lee, H. Y. Association between changes in bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) parameter and the clinical outcomes in patients with acute heart failure. J. Korean Med. Sci. 38, e276. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e276 (2023).

Park, C. H. et al. Association between volume status assessed by bioelectrical impedance analysis, lung ultrasound, or weight change and mortality in patients with sepsisassociated acute kidney injury receiving continuous kidney replacement therapy. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 43, 93–100. https://doi.org/10.23876/j.krcp.23.162 (2024).

Pérez-Morales, R. et al. Extracellular water/total body water ratio as predictor of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Ren. Fail. 43, 821–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022X.2021.1922442 (2021).

Demirci, C. et al. Impedance ratio: A novel marker and a powerful predictor of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 48, 1155–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-016-1292-1 (2016).

Ruperto, M. & Barril, G. The extracellular mass to body cell mass ratio as a predictor of mortality risk in hemodialysis patients. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081659 (2022).

Iwasaka, C. et al. Association between the appendicular extracellular-to-intracellular water ratio and all-cause mortality: A 10-year longitudinal study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glad211 (2024).

Cornejo-Pareja, I. et al. Overhydration assessed using bioelectrical impedance vector analysis adversely affects 90-day clinical outcome among SARS-CoV2 patients: A new approach. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14132726 (2022).

Rodriguez-Moguel, N. et al. Fluid status assessment in critically ill patients with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13020540 (2024).

Ge, Y. Z. et al. The age-related obesity paradigm: Results from two large prospective cohort studies. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 15, 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13415 (2024).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES Survey Methods and Analytic Guidelines. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/AnalyticGuidelines.aspx

Zipf, G. et al. National health and nutrition examination survey: Plan and operations, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat. 1, 1–37 (2013).

Liu, H., Wang, L., Chen, C., Dong, Z. & Yu, S. Association between dietary niacin intake and migraine among American adults: National health and nutrition examination survey. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153052 (2022).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ethics Review Board Approval. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about/erb.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm

Qing, L., Zhu, Y., Yu, C., Zhang, Y. & Ni, J. Exploring the association between dietary Inflammatory Index and chronic pain in US adults using NHANES 1999–2004. Sci. Rep. 14, 8726. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58030-w (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Association between migraine and cardiovascular disease mortality: A prospective population-based cohort study. Headache 63, 1109–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14616 (2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES 1999-2000. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Data/Nhanes/Public/1999/DataFiles/BIX.htm#Protocol_and_Procedure

Lee, Y. H., Lee, J. D., Kang, D. R., Hong, J. & Lee, J. M. Bioelectrical impedance analysis values as markers to predict severity in critically ill patients. J. Crit. Care 40, 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.03.013 (2017).

Yilmaz, Z. et al. Evaluation of fluid status related parameters in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: Clinical usefulness of bioimpedance analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 50, 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medici.2014.10.007 (2014).

Malbrain, M. L. et al. The use of bio-electrical impedance analysis (BIA) to guide fluid management, resuscitation and deresuscitation in critically ill patients: A bench-to-bedside review. Anaesthesiol. Intensive Ther. 46, 381–391. https://doi.org/10.5603/AIT.2014.0061 (2014).

Basso, F. et al. Fluid management in the intensive care unit: Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis as a tool to assess hydration status and optimal fluid balance in critically ill patients. Blood Purif. 36, 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356366 (2013).

Armstrong, L. E. Hydration assessment techniques. Nutr. Rev. 63, S40-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2005.tb00153.x (2005).

Liu, C. A. et al. Muscle distribution in relation to all-cause and cause-specific mortality in young and middle-aged adults. J. Transl. Med. 21, 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04008-7 (2023).

Akimoto, T., Tasaki, K., Ishihara, M., Hara, M. & Nakajima, H. Association of body water balance, nutritional risk, and sarcopenia with outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A single-center prospective study. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132165 (2024).

Zhang, T. Y. et al. The relationship between system inflammation response index and coronary heart disease: A cross-sectional study (NHANES 2007–2016). Front Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1439913. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1439913 (2024).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory Procedure Manual, Biochemistry Profile, Serum, Hitachi Model 917 Multichannel Analyzer. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/1999/labmethods/lab18_met_biochemistry_profile.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory Procedure Manual, C-Reactive Protein, Matrix: Serum, Nephelometry. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2003/labmethods/l11_c_met_c_reactive_protein.pdf

Wu, B. et al. Comparative performance of body composition parameters in prediction of death in hospitalized patients on maintenance hemodialysis: A cohort study. Sci. Rep. 10, 10199. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67019-0 (2020).

Low, S. et al. Higher extracellular water to total body water ratio was associated with chronic kidney disease progression in type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complic. 35, 107930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2021.107930 (2021).

Lee, Y., Kwon, O., Shin, C. S. & Lee, S. M. Use of bioelectrical impedance analysis for the assessment of nutritional status in critically ill patients. Clin. Nutr. Res. 4, 32–40. https://doi.org/10.7762/cnr.2015.4.1.32 (2015).

Woodrow, G. Extracellular water expansion: Part of the malnutrition-inflammation-atherosclerosis syndrome?. Perit. Dial. Int. 26, 566–570 (2006).

Rymarz, A., Bartoszewicz, Z., Szamotulska, K. & Niemczyk, S. The associations between body cell mass and nutritional and inflammatory markers in patients with chronic kidney disease and in subjects without kidney disease. J. Ren. Nutr. 26(2), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2015.09.005 (2016).

Risović, I.A.-O., Vlatković, V., Popović-Pejičić, S. & Trbojević-Stanković, J. Relationship between leptin level, inflammation, and volume status in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Ther. Apher. Dial. 23(1), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-9987.12750 (2022).

Kim, E. J. et al. Extracellular fluid/intracellular fluid volume ratio as a novel risk indicator for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients. PLoS ONE 12, e0170272. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170272 (2017).

Jequier, E. & Constant, F. Water as an essential nutrient: The physiological basis of hydration. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2009.111 (2010).

Popkin, B. M., D’Anci, K. E. & Rosenberg, I. H. Water, hydration, and health. Nutr. Rev. 68, 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x (2010).

Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems v. 9th edition. (Cengage Learning, 2016).

Nishikawa, H. et al. Extracellular water to total body water ratio in viral liver diseases: A study using bioimpedance analysis. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081072 (2018).

Pescari, D., Mihuta, M. S., Bena, A. & Stoian, D. Comparative analysis of dietary habits and obesity prediction: Body mass index versus body fat percentage classification using bioelectrical impedance analysis. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193291 (2024).

Chen, J., Sabir, S. & Al Khalili, Y. Physiology, osmoregulation and excretion. In StatPearls Internet. (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Lee, J. & Shields, R. K. Extracellular to intracellular body water and cognitive function among healthy older and younger adults. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk7010018 (2022).

Cai, Z. et al. Associations between body composition and nutritional assessments and biochemical markers in patients with chronic radiation enteritis: A case-control study. Nutr. J. 15, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-016-0177-6 (2016).

Antlanger, M. et al. Fluid overload in hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study to determine its association with cardiac biomarkers and nutritional status. BMC Nephrol. 14, 266. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-14-266 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank the clinical scientist team for contribution to the statistical support, study design consultations, and comments regarding the manuscript. Additionally, the authors would like to thank the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for making NHANES data publicly available. The authors also acknowledge the efforts of NHANES participants and data collection staff.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. J.L. contributed to data interpretation, manuscript revision, and critical review. H.H. assisted in drafting the manuscript. Q.L., L.Z., G.W., and X.S. assisted in data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Liu, J., Hao, H. et al. Non-linear association between extracellular water/total body water ratio and all-cause mortality: a population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 19032 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04202-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04202-1