Abstract

Patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) reported significantly more constipation and flatulence than healthy controls. An altered gut microbiome can be associated with gastrointestinal symptoms. However, comprehensive information about associated risk of intestinal disorders and ADHD remains limited. A systematic review of the literature was therefore conducted to investigate the association between ADHD and different types of intestinal disorders. A total of 11 studies with 3,851,163 unique individuals, including 175 806 individuals with ADHD and 3 675 357 individuals without ADHD were included. The pooled OR of intestinal disorders for individuals with ADHD was 1.25 (95%CI, 0.75–2.07). A significant positive association was found between ADHD and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (OR 1.63 [95% CI 1.45–1.83]). Studies conducted in Eastern Mediterranean Region yielded a summary OR estimate that was higher than summary OR estimates in studies conducted in Region of the Americas, European Region and Western Pacific Region (3.03 [1.53–5.99] vs. 2.20 [1.05–4.63], 1.04 [0.44–2.41], 0.68 [0.25–1.87]), with p value 0.053, indicating a trend towards significance. High heterogeneity was observed. Our study supports association between ADHD and increased risk of IBS. Our study suggests an altered gut microbiome is the potential link that bridges gap between ADHD and intestinal disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a chronic neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsiveness, which usually begins its course from childhood and persists through adulthood1. ADHD is one of the most prevalent neuropsychiatric childhood disorders with prevalence ranging from 3.4 to 14%2. The prevalence of symptomatic adult ADHD was 6.76%, translating to 366.33 million affected adults in 2020 globally3. ADHD has been linked to a broad range of adverse consequences for affected individuals, including increased risk of smoking4, substance-related disorders5, sexual risk-taking behaviour6, greater driving risk7 and suicidal behaviour8. The chronic debilitating disease poses a significant economic burden on families and society9.

Clinically, ADHD is characterized by specific behavioural traits with inattention and hyperactivity. In addition, psychological comorbidity with ADHD is substantial. ADHD is known to co-occur with various neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, learning disorders, tic disorders, depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder10. Apart from neuropsychiatric disorders, ADHD has been associated with increased risk of medical conditions including obesity, sleep disorder and asthma11. These factors contribute to its classification as a significant public health concern12.

Intestinal disorders are a wide spectrum of diseases describing diseases originating from the intestine or affecting the normal function of digestion and absorption of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract13. The exact cause of the certain types of intestinal disorders are entirely unclear. Intestinal disorders can be classified into different types. Functional intestinal disorder is a spectrum of chronic gastrointestinal disorders characterized by symptoms or signs of abdominal pain, bloating, distention and bowel habit abnormalities, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)14. Insufficient evidence exists regarding the etiology of other inflammatory intestinal disorders including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)15 and celiac disease16. There is increasing evidence suggesting the role of gut microbiota in developing intestinal disorders and neuropsychiatric disorders. Gut-brain axis17 refers to the network of connections involving multiple biological systems that allows bidirectional communication between gut bacteria and the brain. The healthy gut microbiome refers to the collection of bacteria, viruses, bacteriophages, protozoa and fungi residing in the human gut that confer health benefits18. Dysbiosis, in contrast, is the imbalanced state of gut microbial communities that can lead to dysregulation of bodily functions and various diseases19. An altered gut microbiome has been implicated in various neuropsychiatric disorders including Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease and autism spectrum disorders20. An altered gut microbiome can be associated with gastrointestinal symptoms, including constipation, diarrhoea and flatulence. Children with ADHD reported significantly more constipation and flatulence symptoms than the healthy controls21.

Given the abundance of studies trying to connect the gut-brain-axis with ADHD, an investigation into whether ADHD patients exhibit more gastrointestinal pathologies than the neurotypical population is the first step to identify dysbiosis in ADHD. The objective of this meta-analysis is to consolidate the available literature on the association between ADHD and intestinal disorders including IBS, IBD, celiac disease, constipation, dyspepsia, recurrent abdominal pain, Shigellosis, peptic ulcer, and fecal incontinence from different geographical regions in the East and West, and to shed light on future investigations and management of intestinal disorders in patients with ADHD.

Method

This meta-analysis was developed per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses22 reporting guideline. The study was registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42023486812).

Study design

A systematic literature search of key databases, including EMBASE, Medline, Web of Science and APA PsycINFO, was conducted to identify relevant studies from their inception until 16 November 2023. Search terms were related to diarrhoea, bowel disease, bowel disorder, inflammatory bowel, Crohn’s disease, colitis, mucous, colon, irritable bowel, irritable bowel syndrome, functional gastrointestinal disorder, ulcerative colitis, constipation, colonic inertia, dyschezia, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, ADHD, ADDH, behavior disorder, disruptive, attention deficit, hyperkinetic, hyperactivity, minimal brain dysfunction, and can be found in Appendix 1 in Supplement. Grey literature was searched via Google Scholar using the search terms and the reference list of included articles.

Study selection

Studies included in the meta-analysis were control studies, nested case-control studies, cohort studies and cross-sectional studies. We included studies that met the following criteria1: including patients diagnosed with ADHD by medical professionals using standardized ADHD diagnosis criteria of all ages2; reporting the number of patients with intestinal disorders3; providing odds ratios (ORs) or relative risks (RRs) or hazard ratio (HR) with corresponding 95% CIs as measures of association or allowing for computation of these measures based on count data reported in the article; and4 published in English. We excluded studies that1 constituted narrative and/or systematic reviews, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts or theses; and2 lacked a clear clinical definition of ADHD or intestinal disorder.

Data extraction

After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened, followed by full-text screening. Screening was completed by 2 independent reviewers (Kwok and Tang), and full text review was completed by 2 independent reviewers (Tang and Cheung) according to eligible criteria set by review team, with discrepancies resolved via discussion among the review authors. A data extraction template was developed, and the following information was extracted for each study by 2 independent reviewers (Cheung and Kwok): authors, year of publication, country, continent, study design, study type, age group, ADHD treatment, ADHD diagnosis criteria, data source of study, number of patients with ADHD, number of patients without ADHD, intestinal disorders with ADHD and intestinal disorders in patients without ADHD and type of intestinal disorder. Included studies were assessed for internal validity and bias risk using the critical appraisal tool, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Appraisal Checklist for reporting prevalence data23. The JBI tool is found in Appendix 2 in Supplement. The research team decided that good-quality studies were required to score 70% or greater (score of > = 7 of 9), moderate-quality studies needed to score 50% to less than 70%(score of 5 or 6 of 9), and poor-quality studies scored less than 50% (score of < = 4 of 9). These quality assessment threshold scores have been used in past reviews24. Quality assessment was completed on all included studies by 2 independent reviewers (Yang and Ng). Any disputes relating to quality assessment between the reviewers were resolved by discussion with senior supervisor (Ip).

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was the OR of intestinal disorders among individuals with ADHD compared with those without and the secondary outcome measure was the OR of specific type of intestinal disorder. The included studies for data analysis25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 were case control studies, cohort or cross-sectional studies. A random-effects meta-analysis was chosen for meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity between the studies was evaluated using univariate meta-regression and subgroup analysis for age group, study type, study design, World Health Organization (WHO) region, number of subjects, and ADHD diagnosis criteria with the I2 statistic and Cochran Q test. Heterogeneity was considered an issue if the I2 statistic was greater than 40% and/or the Q statistic was significant at 2-sided P = 0.0136. Leave-one-out method was used in the sensitivity analysis. The Egger’s test was used to assess publication bias. Package ‘meta’ and ‘metafor’ in the R environment was used throughout the data analysis.

Results

Study selection

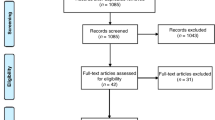

A total of 1992 studies were initially identified through a systematic search. Following a process of duplicate exclusion and abstract screening, 97 studies were considered potentially relevant and subjected to a thorough full-text review. Finally, 11 studies were included, encompassing a combined study population of 3,851,163 individuals, including 175 806 individuals with ADHD and 3 675 357 individuals without ADHD. The stepwise selection process is depicted in Fig. 1.

The publication timeline of the included studies varied, with 2 studies published in 2000 s, 5 studies published in 2010 s and 4 studies published in 2020 s. Geographically, the studies covered a wide range of regions, with 2 studies conducted in North America, 4 in Europe and 5 in Asia. Five cohort studies, five case-control studies and one cross-sectional study were included. The World Health Organization’s Ninth Revision, International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) was used for ADHD diagnosis in 5 (45.5%) studies, while Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) was used in 3 (27.3%) studies, and both diagnostic criteria were used for diagnosis in 1 (9.1%) study. 9 (81.8%) studies were retrospective studies, while 2 (18.2%) studies were prospective studies. The detailed characteristics of each included study can be found in Table 1.

Quality assessment of the included studies

The JBI quality checklist (https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools) determined that most the studies were of good quality (10 [91%]). One study (9%) was of moderate quality. No studies were excluded from the main meta-analysis based on the JBI score. The quality assessment score for each study is in Table 1.

ADHD and intestinal disorders

The association between ADHD and intestinal disorders was investigated in 11.

studies. The summary estimate of ADHD as a risk factor for intestinal disorders was OR of 1.25 (95%CI, 0.75–2.07), with heterogeneity of I2 = 99% (P < 0.01). Figure 2 showed the overall risk estimates of association between ADHD and all types of intestinal disorders reported in the included studies, including IBS, IBD subtype, celiac disease, constipation, dyspepsia, recurrent abdominal pain, Shigellosis, peptic ulcer, and fecal incontinence.

Forrest plot showing odds ratios (OR) for all types of intestinal disorders in ADHD. The size of the box representing the point estimate for each study in the forest plot is proportional to the contribution of that study’s weight estimate to the summary estimate. The diamond represents the pooled odds ratio (OR); the lateral tips of the diamond represent the associated 95%CIs.

Association between ADHD and all types of intestinal disorders

Figure 3: Forrest plot showing odds ratios (OR) for irritable bowel syndrome in ADHD. The size of the box representing the point estimate for each study in the forest plot is proportional to the contribution of that study’s weight estimate to the summary estimate. The diamond represents the pooled odds ratio (OR); the lateral tips of the diamond represent the associated 95%CIs.

Meta-regression and subgroup analysis

Meta-regression and subgroup analysis, stratified by various study-level characteristics, were conducted to explore sources of heterogeneity. In univariate meta-regression, none of the study-level characteristics were found to be significantly associated with the outcome, although WHO regions had the largest contribution (R² = 1.17%). Similarly, in the subgroup analysis, studies conducted in Eastern Mediterranean Region yielded a summary OR estimate that was higher than the summary OR estimates in studies conducted in Region of the Americas, European Region and Western Pacific Region (3.03 [1.53–5.99] vs. 2.20 [1.05–4.63], 1.04 [0.44–2.41], 0.68 [0.25–1.87]), with p value 0.053, indicating a trend towards significance (Appendix 3 in Supplement). No statistically significant differences in OR estimates were found between subgroups of studies stratified by age group (adults, children, or subjects of all ages), study type, study design (case-control study, cross-sectional study, or cohort study) and number of subjects (less than 1000 versus equal or more than 1000).

Sensitivity analysis

Appendix 4 in Supplement showed Leave-one-out analysis. After excluding 1 potential outlier (Van den Heuvel et al.) studying constipation among children, a case-control study with a relatively small sample size and the use of outpatient control (instead of community control), the pooled odds ratio (OR 1.47 [95% CI 1.00–2.16] revealed a statistically significant positive association between ADHD and intestinal disorders.

Publication Bias

Figure 4 shows a funnel plot illustrating the potential publication bias. The studies are distributed around the pooled effect size (indicated by the vertical line at the center), both within and outside the funnel’s contours. This suggests a reduced likelihood of significant bias in smaller studies, which are more susceptible to yielding nonsignificant results and therefore potentially going unnoticed. Egger’s test does not provide strong evidence for the presence of funnel plot asymmetry and publication bias in the meta-analysis (p-value = 0.38).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis comprehensively summarized the available literature and revealed an association between ADHD and IBS. Notably, in subgroup analysis, there was a trend that studies conducted in Eastern Mediterranean Region yielded a summary OR estimate of intestinal disorders that was higher than those in Region of the Americas, European Region and Western Pacific Region (p = 0.053).

ADHD has been associated with increased risk for intestinal disorders21. Compared with previous studies, the novelty of our study lies in providing the pooled estimates of the published studies with a wide range of international population using meta-analysis. Limited research existed to study the association between intestinal disorders with ADHD with inconsistent findings. Some studies reported a higher rate of encopresis37, stomach bloating and cramps38 in children of ADHD compared with those without ADHD. Other study showed no difference of gastrointestinal problems in ADHD and non-ADHD twins39. In our study, more detailed and specific data focusing on ADHD and different types of intestinal disorders with clinical diagnostic criteria determined by clinical professionals instead of patients’ symptoms would be useful for a broad range of physicians as well as parents.

Our results showed a trend towards significance for the subgroup difference of the risk of intestinal disorders in ADHD in different WHO regions, with OR estimate of Eastern Mediterranean Region higher than those in Americas, European Region and Western Pacific Region. Differences in ADHD prevalence in different geographical regions40 may be due to differences in study methodologies, including sample size, response rate, information sources from parents or teachers, cultural factors and clinical diagnosis criteria of ADHD. Similar ADHD patient populations from North American and non-North America were identified with the same diagnostic assessment, yielding a uniform disease prevalence with the use of standardized diagnostic criteria41. This study highlights the importance of standardized ADHD diagnostic criteria when researchers compare data from different regions.

Our study showed a positive association between ADHD and IBS, with odds of IBS in ADHD patients 1.63 times greater than that in controls. The etiology of IBS was poorly understood as it is often multifactorial. It has been postulated that IBS pathogenesis involves altered or overgrowth of gut microbiome, hypersensitivity to food, post infection reactivity or inflammation, and altered intestinal motility42. Specifically, IBS patients had significantly lower alpha diversity and enrichment of Gram-negative bacteria with reduction in pathways associated short-chain fatty acid, differentiating microbial features in healthy and IBS subtypes43. Our results suggest that gut microbiome may explain the link between ADHD and IBS. Our finding of the positive association between ADHD and IBS suggests that clinicians should be aware of gastrointestinal symptoms in children and adults with ADHD. Gastrointestinal symptoms were independently associated with aberrant behaviour checklist in patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and ADHD44. Screening of IBS may be considered during assessment of patients with ADHD, especially those presenting with abdominal discomfort or other gastrointestinal complaints. Appropriate assessment of intestinal disorders in patients with ADHD may help diagnosis and early management. This could improve quality of life in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders and their families.

IBS considerably affects quality of life in affected patients. Its presence in ADHD patients may further complicate the management of ADHD. Treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms due to IBS in ADHD patients could improve overall functioning of ADHD patients. On the other hand, methylphenidate, the first line treatment for ADHD, increases the risks of abdominal pain in ADHD patients45. There is a need for clinicians to adopt a more proactive approach in the assessment gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with ADHD. Although patients with ADHD experience increased direct health care costs46, there is lack of evidence of prediction of later development of more severe gastrointestinal conditions in childhood ADHD patients suffering from IBS or other gastrointestinal disorders. More studies are needed on the long-term clinical outcome of ADHD patients.

As a neurodevelopmental disorder, ADHD still remains a chronic disease with largely unexplained etiology. There is evidence of strong genetic component of common variants in the polygenic architecture of ADHD with 22% of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)-based heritability47. Although considered a highly familial disorder, ADHD heritability estimates of 60–80% highlight a potential role of environmental factors in the susceptibility of this disorder48. ADHD has been associated with an increased oxidative stress and neuroinflammation49. Recent studies have highlighted the potential influence of gut microbiota on health and disease. Gut microbial therapy by administration of probiotics, synbiotics and prebiotics may alleviate the medical condition in specific disorders, for example reduction of C-reactive protein50, low-density lipoprotein (LDL)51, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase52 and insulin resistance53 among non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Gut microbiome is recognized as a key player in the pathogenesis of ADHD in gut-brain axis54,55, where the neural, endocrine and immunological pathways are involved this communication interplay56. Alterations in gut microbiome in ADHD were reported in previous studies, with ADHD group showing higher level of Dialister and Megamonas and lower abundance of Anaerotaenia and Gracilibacter at the genus level57, and Bacteroides species correlating with levels of hyperactivity and impulsivity58. Microorganisms influence the brain through their ability to produce and modify metabolic, immunological and neurochemical factors in the gut that ultimately impact on the central nervous system59. In turn, brain activity also impacts the gut microbiota composition60. The gut microbiota influences gut barrier and produce neurotransmitters, amino acids and microbial metabolites61. This dynamic bidirectional communication between the gut microbiota and the central nervous system influences brain function, cognition and behavior. Future studies are needed to elucidate the role of the gut microbiota in ADHD and the associated comorbid medical conditions including intestinal disorders.

Microbiota-targeted interventions, including mixture of probiotic and prebiotic, was shown to increase propionic acid levels in children with ADHD, contributing to lowering of higher-than-normal proinflammatory intercellular adhesion molecule 1 levels in a randomized controlled trial62. Higher therapeutic efficacy was associated with the usage of probiotics as an adjunct to methylphenidate in the treatment of ADHD63. Future studies are warranted to systemically investigate the role of microbiota-targeted interventions in the treatment of ADHD.

Alterations of gut microbiome is associated with pathogenesis of various intestinal disorders. Gut dysbiosis in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis is characterized by reduced abundance of the phylum Firmicutes and increase in the phylum Proteobacteria64. Depletion of butyrate-producing bacteria results in a metabolic reorientation of surface colonocytes towards anaerobic glycolysis and an increase of oxygen diffusion into the lumen leading to luminal aerobe and/or facultative anaerobe expansion65. On the other hand, environmental stimuli may play a role in Celiac disease, another autoimmune disease with unknown etiology. Alterations in the gut microbiota, functional pathways and metabolome were identified in a prospective study of infants who developed Celiac disease. Increased abundances of several microbial species, including Dialister invisus and Parabacteroides species were detected before onset of Celiac disease, which were previously linked to autoimmune conditions66.

Limitations

This meta-analysis has several limitations. First, nearly half of studies were from Asia, which may lead to bias and lack of certainty in generalizing the results to other regions. Second, heterogeneities between examined studies warrant attention. The study population differed to a certain degree, for example, some studies focused on specific individuals, 6 studies included children, 3 studies included adults and 2 included participants of all ages. These discrepancies in the findings may be due to differences in study design, study population, diagnostic criteria for ADHD and GI diseases. ICD has a stricter clinical definition for ADHD while DSM is more lenient which depends on operational criteria requiring combination of criteria. Third, this meta-analysis has a small sample size including data from 11 studies. Fourth, the small number of studies included in some of the groups may have biased some subgroup analysis results. Fifth, the finding of WHO regional differences for the association of ADHD and intestinal disorders indicating a trend towards significance may be due to a small sample size, but this noteworthy difference warrants further investigation. Sixth, majority of the studies (n = 9) included in this meta-analysis were retrospective studies, which were prone to recall bias and incomplete data collection. This might result in overestimation or underestimation of the true relationship between ADHD and risk of intestinal disorders.

Conclusions

To conclude, our study showed no significant association between ADHD and all types of intestinal disorders, but it demonstrated an increased incidence of irritable bowel syndrome among ADHD patients. Further studies are needed for systemic investigation of the role of intestinal microbiota in ADHD. An altered gut microbiome and its inflammatory effect is the potential link that bridges the gap between ADHD and intestinal disorder. The exact detailed mechanism of dysbiosis and its effect on inflammatory dysregulation is yet to be elucidated in future studies. Hence, it would be important to conduct both basic science and clinical studies to investigate any possible changes in neurotransmitters, neurometabolism, and neuroanatomy that may be caused by dysbiosis. More studies are warranted to confirm a significant relationship between ADHD and intestinal disorders.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Posner, J., Polanczyk, G. V. & Sonuga-Barke, E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet (British edition). 395 (10222), 450–462 (2020).

Ayano, G., Demelash, S., Gizachew, Y., Tsegay, L. & Alati, R. The global prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. J. Affect. Disord. 339, 860–866 (2023).

Song, P. et al. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Global Health ;11. (2021).

McCabe, S. E. et al. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder symptoms and later E-Cigarette and tobacco use in US youths. JAMA Netw. Open. 8 (2), e2458834–e (2025).

Groenman, A. P., Janssen, T. W. & Oosterlaan, J. Childhood psychiatric disorders as risk factor for subsequent substance abuse: a meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 56 (7), 556–569 (2017).

Spiegel, T. & Pollak, Y. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and increased engagement in sexual risk-taking behavior: the role of benefit perception. Front. Psychol. 10, 1043 (2019).

El Farouki, K. et al. The increased risk of road crashes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) adult drivers: driven by distraction? Results from a responsibility case-control study. PLoS One. 9 (12), e115002 (2014).

Garas, P. & Balazs, J. Long-term suicide risk of children and adolescents with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder—a systematic review. Front. Psychiatry. 11, 557909 (2020).

Sciberras, E. et al. Social and economic costs of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. J. Atten. Disord. 26 (1), 72–87 (2022).

Gnanavel, S., Sharma, P., Kaushal, P. & Hussain, S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity: A review of literature. World J. Clin. Cases. 7 (17), 2420 (2019).

Instanes, J. T., Klungsøyr, K., Halmøy, A., Fasmer, O. B. & Haavik, J. Adult ADHD and comorbid somatic disease: a systematic literature review. J. Atten. Disord. 22 (3), 203–228 (2018).

Rowland, A. S., Lesesne, C. A. & Abramowitz, A. J. The epidemiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a public health view. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 8 (3), 162–170 (2002).

Lacy, B. E. et al. Bowel Disorders Gastroenterol. ;150(6):1393–1407. (2016). e5.

Black, C. J., Drossman, D. A., Talley, N. J., Ruddy, J. & Ford, A. C. Functional Gastrointestinal disorders: advances in Understanding and management. Lancet 396 (10263), 1664–1674 (2020).

Fiocchi, C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 115 (1), 182–205 (1998).

Parzanese, I. et al. Celiac disease: from pathophysiology to treatment. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiology. 8 (2), 27 (2017).

Morais, L. H., Schreiber, I. V. H. L. & Mazmanian, S. K. The gut microbiota–brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19 (4), 241–255 (2021).

Shanahan, F., Ghosh, T. S. & O’Toole, P. W. The healthy microbiome—what is the definition of a healthy gut microbiome? Gastroenterology 160 (2), 483–494 (2021).

Hou, K. et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 7 (1), 135 (2022).

Cryan, J. F., O’Riordan, K. J., Sandhu, K., Peterson, V. & Dinan, T. G. The gut Microbiome in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 19 (2), 179–194 (2020).

Ming, X. et al. A gut feeling: a hypothesis of the role of the Microbiome in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders. Child. Neurol. Open. 5, 2329048X18786799 (2018).

The PRISMA2020 statement. An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews [Available from: https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/prisma

The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist tool for use in JBI systematic reviews. [ (2017). Available from: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Prevalence_Studies2017_0.pdf

Hall, N. Y., Le, L., Majmudar, I. & Mihalopoulos, C. Barriers to accessing opioid substitution treatment for opioid use disorder: A systematic review from the client perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 221, 108651 (2021).

Chen, M-H. et al. Comorbidity of allergic and autoimmune diseases among patients with ADHD: a nationwide population-based study. J. Atten. Disord. 21 (3), 219–227 (2017).

Güngör, S., Celiloglu, Ö. S., Özcan, Ö. Ö., Raif, S. G. & Selimoglu, M. A. Frequency of Celiac disease in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 56 (2), 211–214 (2013).

Hegvik, T-A., Instanes, J. T., Haavik, J., Klungsøyr, K. & Engeland, A. Associations between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autoimmune diseases are modified by sex: a population-based cross-sectional study. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psych. 27, 663–675 (2018).

Hodgkins, P., Montejano, L., Sasané, R. & Huse, D. Cost of illness and comorbidities in adults diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a retrospective analysis. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disorders. 13 (2), 26160 (2011).

Holmberg, K. & Hjern, A. Health complaints in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acta Paediatr. 95 (6), 664–670 (2006).

Hu, J-M. et al. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A nationwide, population-based cohort study. Front. Psychiatry. 12, 537137 (2021).

Kedem, S. et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and Gastrointestinal morbidity in a large cohort of young adults. World J. Gastroenterol. 26 (42), 6626 (2020).

McKeown, C., Hisle-Gorman, E., Eide, M., Gorman, G. H. & Nylund, C. M. Association of constipation and fecal incontinence with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 132 (5), E1210–E5 (2013).

Merzon, E. et al. Early childhood shigellosis and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study with a prolonged follow-up. J. Atten. Disord. 25 (13), 1791–1800 (2021).

Van Den Heuvel, E., Starreveld, J., De Ru, M., Krauwer, V. & Versteegh, F. Somatic and psychiatric co-morbidity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Paediatr. 96 (3), 454–456 (2007).

Zafari, Z., Shokri, S., Hasanvand, A., Ahmadipour, S. & Anbari, K. The relationship between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and functional constipation in patients referred to pediatric Gastrointestinal clinic of the hospitals of Khorramabad City, Iran. Crescent J. Med. Biol. Sci. ;8(3). (2021).

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023 [Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Johnston, B. D. & Wright, J. A. Attentional dysfunction in children with encopresis. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 14 (6), 381–385 (1993).

Kaplan, B. J., McNICOL, J., Conte, R. A. & Moghadam, H. Physical signs and symptoms in preschool-age hyperactive and normal children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 8 (6), 305–310 (1987).

Pan, P-Y. & Bölte, S. The association between ADHD and physical health: a co-twin control study. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 22388 (2020).

Salari, N. et al. The global prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital. J. Pediatr. 49 (1), 48 (2023).

Buitelaar, J. K. et al. A comparison of North American versus non-North American ADHD study populations. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psych. 15, 177–181 (2006).

Saha, L. Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 20 (22), 6759 (2014).

Phan, J. et al. Alterations in gut Microbiome composition and function in irritable bowel syndrome and increased probiotic abundance with daily supplementation. mSystems 6 (6), e01215–e01221 (2021).

Kurokawa, S. et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and sensory abnormalities associated with behavioral problems in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Autism Res. 14 (9), 1996–2001 (2021).

Holmskov, M. et al. Gastrointestinal adverse events during methylphenidate treatment of children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomised clinical trials. PLoS One. 12 (6), e0178187 (2017).

Jennum, P. et al. Long-term effects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on social functioning and health care outcomes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 182, 212–220 (2025).

Walters, R. K. et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat. Genet. 51 (1), 63–75 (2019).

Froehlich, T. E. et al. Update on environmental risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 13, 333–344 (2011).

Corona, J. C. Role of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Antioxidants 9 (11), 1039 (2020).

Mahapatro, A. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics and synbiotics on patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an umbrella study on meta-analyses. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 57, 475–486 (2023).

Naghipour, A. et al. Effects of gut microbial therapy on lipid profile in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an umbrella meta-analysis study. Syst. Reviews. 12 (1), 144 (2023).

Amini-Salehi, E. et al. The impact of gut microbiome-targeted therapy on liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an umbrella meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 82 (6), 815–830 (2024).

Vakilpour, A. et al. The effects of gut Microbiome manipulation on glycemic indices in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a comprehensive umbrella review. Nutr. Diabetes. 14 (1), 25 (2024).

Bercik, P., Collins, S. & Verdu, E. Microbes and the gut-brain axis. Neurogastroenterology Motil. 24 (5), 405–413 (2012).

Zhao, M. et al. A bibliometric analysis of studies on gut microbiota in attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder from 2012 to 2021. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1055804 (2023).

Montiel-Castro, A. J., González-Cervantes, R. M., Bravo-Ruiseco, G. & Pacheco-López, G. The microbiota-gut-brain axis: neurobehavioral correlates, health and sociality. Front. Integr. Nuerosci. 7, 70 (2013).

Richarte, V. et al. Gut microbiota signature in treatment-naïve attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Translational Psychiatry. 11 (1), 1–7 (2021).

Gkougka, D. et al. Gut Microbiome and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. Pediatr. Res. 92 (6), 1507–1519 (2022).

Erny, D. et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 18 (7), 965–977 (2015).

Kuwahara, A. et al. Microbiota-gut-brain axis: enteroendocrine cells and the enteric nervous system form an interface between the microbiota and the central nervous system. Biomed. Res. 41 (5), 199–216 (2020).

Dalile, B., Van Oudenhove, L., Vervliet, B. & Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota–gut–brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16 (8), 461–478 (2019).

Yang, L. L. et al. Effects of a synbiotic on plasma immune activity markers and short-chain fatty acids in children and adults with ADHD—a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 15 (5), 1293 (2023).

Liang, S-C. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of probiotics for symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: meta-analysis. BJPsych Open. 10 (1), e36 (2024).

Nagalingam, N. A. & Lynch, S. V. Role of the microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18 (5), 968–984 (2012).

Andoh, A. & Nishida, A. Alteration of the gut Microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion 104 (1), 16–23 (2023).

Leonard M.M. et al. Microbiome signatures of progression toward Celiac disease onset in at-risk children in a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118 (29), e2020322118 (2021).

Funding

The work described in this paper was fully supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China. [Project No.: CUHK 24115121]

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.R.W.Y: Drafting of the manuscript, administrative, technical, or material support, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. C.Z.: Statistical analysis, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Y.L.: Drafting of the manuscript, statistical analysis, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. W.O.W.H: Administrative, technical, or material support, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. L.A.S.Y.: Administrative, technical, or material support, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. T.K.W.: Administrative, technical, or material support, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. K.N.M.W.: Statistical analysis, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. T.L.H.Y.: Statistical analysis, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. C.P.M.H.: Statistical analysis, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. C.P.K.S.: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, supervision, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. I.M.: Concept and design, full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ng, R.W., Chen, Z., Yang, L. et al. Association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders and intestinal disorders: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Sci Rep 15, 19278 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04303-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04303-x