Abstract

Accurate prediction of silicon content in blast furnace ironmaking is essential for optimizing furnace temperature control and production efficiency. However, large-scale industrial datasets exhibit complexity, dynamism, and nonlinear relationships, posing challenges for feature selection. Traditional methods rely heavily on static statistical techniques and expert knowledge, limiting their adaptability to dynamic operating conditions. This study proposes a Bayesian online sequential update and support vector regression recursive feature elimination (BOSVRRFE) algorithm for dynamic feature selection. By integrating Bayesian dynamic updating and recursive optimization, BOSVRRFE adjusts feature importance in real-time, efficiently optimizing input variables. Experiments with data from a large steel enterprise validate BOSVRRFE’s performance in silicon content prediction. Results show that BOSVRRFE outperforms traditional static methods in prediction accuracy, real-time adaptability, and model stability. Additionally, it rapidly responds to operational changes, supporting real-time industrial prediction and optimization. This study provides theoretical and practical guidance for silicon content prediction and introduces an innovative approach to feature selection in complex dynamic industrial data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blast furnace smelting is a core process in steel production, aiming to reduce iron ore and coke into molten iron while producing slag as a byproduct. This process involves complex interactions among multiphase materials and concurrent physical and chemical phenomena, making it one of the most challenging nonlinear dynamic systems in metallurgy1. Furnace temperature control is critical in blast furnace smelting; it directly affects production efficiency and molten iron quality, and it determines the stability of iron composition and the safety of equipment operation2. As an important component of molten iron, the silicon content’s concentration variation serves as a key reference for furnace temperature regulation. Accurately predicting the silicon content is therefore essential for optimizing furnace temperature control and enhancing blast furnace operational efficiency3.

The core challenge in predicting silicon content lies in the complexity of the data. Blast furnace data encompass real-time sensor readings and historical process records, characterized by multi-source origins, varying frequencies, inconsistent data quality, and noise issues, These factors significantly increase the difficulty of extracting key features from massive datasets, Efficiently identifying critical variables essential for silicon content prediction is central to building an accurate prediction model4.

Traditional feature selection methods often combine domain expert experience with static statistical techniques. While intuitive and straightforward, these methods are highly subjective and struggle to cope with dynamic changes and nonlinear relationships in blast furnace operating conditions. Additionally, when faced with complex industrial data and real-time demands, traditional methods often lack efficiency, failing to meet practical production needs.

To address these issues, this study proposes a novel dynamic feature selection algorithm termed BOSVRRFE, which integrates Bayesian online sequential updating with support vector regression-based recursive feature elimination (SVR-RFE). BOSVRRFE is designed to dynamically optimize feature subsets in response to evolving industrial conditions, thereby maintaining model robustness and adaptability over time. Furthermore, a lightweight real-time adaptation mechanism is developed, enabling continuous adjustment of feature importance without requiring full model retraining. This significantly enhances system responsiveness and computational efficiency. By leveraging Bayesian updating to dynamically track changes in feature relevance and employing recursive feature elimination to refine the feature set, BOSVRRFE achieves efficient screening and automatic optimization of input variables, ultimately improving the predictive performance of the silicon content prediction model.

Extensive experiments conducted on large-scale real blast furnace datasets validate the superior performance of the proposed method. Compared to traditional static feature selection approaches, BOSVRRFE exhibits higher prediction accuracy, greater stability, and improved real-time adaptability. The experimental results demonstrate that the method can predict molten iron silicon content in real time and quickly respond to changes in furnace conditions, providing scientific guidance for operators in the production environment. Furthermore, the algorithm has important application value in enhancing blast furnace production efficiency and product quality. The research findings provide theoretical basis and practical guidance for constructing blast furnace silicon content prediction models based on machine learning.

Related work

Process-oriented feature categorization

The blast furnace ironmaking process is a complex, nonlinear, and time-delayed system. Multiple physical and chemical reactions occur simultaneously across different zones of the furnace. Among the key indicators, the silicon content Si in hot metal reflects the furnace’s thermal state and is influenced by a wide range of operational parameters.

In this study, a large number of features were extracted from the blast furnace data system, covering raw materials, burden structure, gas flow, temperatures, pressures, and slag composition. Instead of listing all variables, we group them according to their relevance to different furnace zones:

-

Charging zone: burden composition, coke and sinter ratios;

-

Gas reaction zone: top gas temperature, gas composition;

-

Combustion zone: hot blast temperature, oxygen enrichment, blast volume;

-

Hearth zone: hearth temperature, slag ratios (e.g., CaO/SiO₂, MgO/Al₂O₃);

-

Process feedback: pressure differentials, tuyere gas properties.

To support this grouping, Fig. 1 shows a schematic of the blast furnace, with major temperature zones, flow directions, and chemical reactions. The selected features correspond to physical phenomena occurring in these zones, providing a meaningful basis for model development.

This process-based organization improves the interpretability of feature selection and aligns data-driven modeling with industrial knowledge.However, selecting relevant features from such high-dimensional, process-driven data presents its own set of challenges, which are discussed in the next section.

Challenges of feature selection in blast furnace silicon content prediction

Feature selection plays a key role in constructing reliable silicon content prediction models under complex blast furnace conditions. However, it faces the following main challenges:

Redundancy and diversity in complex industrial data

Blast furnace production involves multi-source heterogeneous data, including burden composition (e.g., silicon, carbon, iron content), reaction conditions (e.g., temperature and pressure), and gas distribution (e.g., CO, CO₂ concentrations). These data exhibit significant complexity and diversity, with some variables potentially being redundant or weakly correlated. This increases the complexity of feature selection and can negatively impact model performance. Therefore, efficiently identifying key variables crucial for silicon content prediction from complex industrial data is the primary challenge for feature selection5,6.

Adaptability to dynamic operating conditions

Dynamic operating conditions in the blast furnace ironmaking process—such as burden fluctuations, blast volume adjustments, and environmental condition changes—cause significant variations in data distribution over time, altering feature importance. Traditional static feature selection methods cannot dynamically adjust feature subsets to accommodate these changes, potentially compromising model robustness in complex environments. Consequently, feature selection methods must possess dynamic adjustment capabilities to evaluate and update feature importance in real time, ensuring models respond quickly to changing conditions and maintain real-time predictive performance7.

Complex nonlinear and interaction relationships among features

Changes in furnace temperature and silicon content are influenced by the synergistic effects of multiple variables. For example, significant nonlinear relationships or interaction effects may exist between burden composition and gas utilization rates. Traditional feature selection methods based on linear correlation struggle to capture these complex interaction patterns, potentially leading to the omission of key features. Feature selection methods need to uncover nonlinear relationships and variable interaction patterns to enhance model prediction performance under complex operating conditions8,9.

In summary, feature selection methods for predicting silicon content in blast furnace ironmaking must effectively address redundancy in complex industrial data, ensure real-time adaptability under dynamic operating conditions, and uncover nonlinear relationships to guarantee prediction accuracy and stability in practical industrial scenarios.

Literature review

Accurate prediction of silicon content in blast furnace ironmaking is critical for furnace temperature control and production efficiency. Traditional feature selection strategies mainly rely on domain expertise and process mechanism analysis, focusing on selecting physical and chemical attributes directly related to silicon content variation (e.g., burden composition, reaction temperature, and pressure).While intuitive and straightforward, these methods exhibit several limitations: they are subjective, difficult to scale to high-dimensional data, and lack adaptability to changing operational conditions. Given the complex, nonlinear, and time-varying nature of industrial processes, more systematic, data-driven feature selection strategies are needed.

Machine learning-driven feature selection methods in industrial prediction

Machine learning methods have demonstrated significant advantages in feature selection, especially in industrial prediction tasks. For instance, Stein et al.10 developed the iGATE tool, which combines domain expert knowledge with statistical analysis to identify key process parameters affecting top gas efficiency in steel manufacturing. Wang et al.11 applied kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) for feature selection, effectively extracting key features for silicon content prediction and improving model accuracy and stability. Xianpeng Wang et al.12 proposed the MOENE-EFS model, which uses multi-objective evolutionary algorithms and nonlinear integration methods to optimize silicon content prediction, albeit with high computational complexity. Jiang et al.13 introduced a multi-level feature fusion and dynamic data-driven model that captures trends in silicon content variation, providing theoretical support for monitoring and optimizing blast furnace processes. These studies highlight the excellent performance of machine learning-based feature selection methods in handling high-dimensional and nonlinear industrial data.

At a theoretical level Bolón-Canedo et al.14 provided a comprehensive review of feature selection for high-dimensional data, offering a theoretical framework for feature selection in big data environments. Guyon and Elisseeff15 ocused on objective functions and efficient search strategies for feature selection, providing technical guidance for applications in complex data scenarios. Venkatesh and Anuradha16 emphasized the challenges of feature selection in dynamic data scenarios, such as IoT and web applications, and proposed future research directions. Li et al.17 further extended these ideas to heterogeneous and streaming data contexts. However, most existing methods remain static and are not designed to accommodate feature importance changes over time—a major limitation in industrial settings where data distributions evolve continuously.

SVR-RFE and its limitations

Among embedded methods, support vector regression combined with recursive feature elimination (SVR-RFE) has gained popularity due to its ability to model nonlinear relationships and rank features through model-internal weights. It has been successfully. For example, Hu et al.18 integrated bootstrap SVR with improved RFE for aircraft engine maintenance cost prediction, significantly enhancing model performance. Goli et al.19 applied SVR-RFE in breast cancer survival prediction, improving model accuracy. Fang and Tai20 optimized the combination of mutual information, genetic algorithms, and SVR to enhance QSAR regression model predictions. Despite its success in various domains, the application of SVR-RFE in industrial dynamic data scenarios, such as silicon content prediction in blast furnace ironmaking, remains limited. Traditional SVR-RFE methods face challenges in dynamically adjusting feature importance and addressing computational complexity under the dynamic and real-time demands of industrial data.

Recent progress in dynamic and streaming feature selection

To address the challenge of evolving data, recent studies have explored online and dynamic feature selection frameworks. Wang et al.21 proposed a fast streaming feature screening algorithm under concept drift. Haug et al.22 introduced FIRES, a stable online selection method using model-inherent importance measures. Sun et al.23 incorporated causal inference into dynamic feature selection for soft sensors in industrial processes. Wang et al.24 designed a hybrid framework combining ensemble learning and evolutionary selection for blast furnace silicon content modeling. While these methods move toward adaptability, many lack physical interpretability or integration with embedded learning models such as SVR.

Deep learning models for silicon prediction

In parallel, deep learning has become increasingly prominent in silicon content prediction. Zhang et al.25 used LSTM networks to capture temporal dependencies in sequential furnace data. Yang et al.26 applied CNNs to learn local correlations from spatially distributed sensor inputs. Zhao et al.27 developed a CNN-LSTM hybrid model for robust soft sensing. More recently, Wang et al.28 used attention-based temporal convolutional networks (TCN-Attn), and Liu et al.29 applied transformers for end-to-end sequence modeling of silicon fluctuations.

While these models show impressive accuracy, they often suffer from drawbacks including high data requirements, limited transparency, and weak real-time adaptability. Their black-box nature also hinders industrial deployment where interpretability and control feedback are crucial.

Research gaps and motivation

Despite recent progress, key challenges remain unsolved in silicon content prediction for blast furnace operations. Specifically, few methods offer real-time adaptability to dynamic feature importance, integrated uncertainty modeling, and lightweight deployment for industrial applications. Moreover, many deep learning approaches lack domain interpretability and require large-scale labeled data, which may not be feasible in production environments.

To bridge this gap, we propose BOSVRRFE, a novel feature selection framework that integrates nonlinear modeling (via SVR), Bayesian online importance updating, and dynamic redundancy-aware pruning. Unlike traditional methods, BOSVRRFE is explicitly designed for streaming industrial data and offers both interpretability and adaptability. It provides a unified, physically informed, and computationally efficient approach for online feature selection in high-dimensional, non-stationary prediction tasks such as blast furnace silicon content modeling.

Methodology

This section introduces the proposed dynamic feature selection framework BOSVRRFE, which is designed to address the challenges of high-dimensionality, nonlinear relationships, and real-time adaptability in blast furnace silicon content prediction. The methodology is presented in three parts: the problem formulation, theoretical foundations, and algorithm design.

Problem definition

Let \({X}_{t}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{d}\) denote the observed feature vector at time step \({t}_{1}\), and \({y}_{t}\in {\mathbb{R}}\) the corresponding target variable (e.g., silicon content). The goal of dynamic feature selection is to select a subset of relevant features \({S}_{t}\subseteq \text{1,2},\dots ,d\) and construct a prediction model, such that the expected prediction loss is minimized, while maintaining sparsity and computational efficiency.

We formulate the objective as Eq. (1).:

where:

-

\(\mathcal{L}\left(\cdot \right)\) is a loss function (e.g., MSE),

-

\(\left|{S}_{t}\right|\) is the number of selected features at time t,

-

\(\lambda >0\) is a regularization coefficient controlling sparsity.

The model \({f}_{t}\) is updated online to reflect the evolving data distribution \(P\left({X}_{t},{y}_{t}\right)\), making the selection and prediction process adaptive to changing industrial conditions.

Theoretical foundations

The proposed algorithm is grounded in three core theoretical foundations: Support Vector Regression (SVR), Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), and Bayesian Optimization. This section provides an overview of these theoretical methods to establish the basis for the proposed approach.

Support vector regression (SVR)

SVR is an extension of Support Vector Machine (SVM) tailored for regression tasks. Unlike SVM, which is primarily employed for classification, SVR focuses on fitting continuous numerical data by identifying an optimal hyperplane. SVR maps data into high-dimensional spaces using kernel functions, effectively handling complex nonlinear relationships. Commonly used kernels include linear, polynomial, and radial basis function (RBF) kernels. SVR allows fine-tuning of generalization error by adjusting the regularization parameter C and error tolerance ϵ, balancing model complexity and sensitivity to outliers30,31.

Let the feature set F be defined as \(\{\left({\text{x}}_{\text{i}},{\text{y}}_{\text{i}}\right)\}\), where \(i = 1, 2, \dots , n\). Here, \({\text{x}}_{\text{i}}\) denotes the input features of each sample, and \({\text{y}}_{\text{i}}\) denotes the corresponding output values. By employing a kernel function and a nonlinear mapping function ϕ(x), the low-dimensional feature space is mapped to a high-dimensional space. The regression function \(f\left(\text{x}\right)\) is defined to output \(y\) given \(x\), as articulated in Eq. (2).

where, \(w\) is the vector of weight coefficients. \(b\) is the bias term. \(\phi \left(\text{x}\right)\) denotes the high-dimensional feature vector obtained after mapping \({\text{w}}^{\text{T}}\) represents the transpose of the weight vector w.

SVR incorporates an epsilon-insensitive loss function to measure the discrepancy between the predicted values and the actual values. This loss function is defined by Eq. (3)

where, \(L\left(\text{y},\text{f}\left(\text{x}\right)\right)\) denotes the epsilon-insensitive loss. \(y\) represents the actual output value.\(f\left(\text{x}\right)\) signifies the predicted output. \(\varepsilon\) is the epsilon parameter, which determines the width of the insensitive zone around the actual value within which the prediction is deemed acceptable without penalty.

The training process of SVR involves solving a convex optimization problem to determine the weight vector w and the bias term b. The optimization problem can be formulated as shown in Eq. (4)

where, C > 0 is the regularization parameter that controls the trade-off between achieving a low training error and maintaining a margin that is as large as possible.

The optimization problem in SVR can be transformed into a dual problem by introducing Lagrange multipliers, which allows us to find the optimal Lagrange multipliers \({{\upalpha }}_{i}\) and \({{\upalpha }}_{i}^{*}\). The weight vector \(w\) can then be computed using Eq. (5), For the computation of the bias term b, one can select any support vector \(i\) and calculate it using Eq. (6):

where, only the Lagrange multipliers corresponding to the support vectors \({{\upalpha }}_{i}\) and \({{\upalpha }}_{i}^{*}\) are non-zero. Support vectors are those sample points that violate the epsilon-insensitive tube constraints or lie on the boundary of the tube. These support vectors are crucial in defining the final regression function.

SVR fits data by finding a linear hyperplane in a high-dimensional space. It employs an epsilon-insensitive loss function to reduce the sensitivity to outliers and uses a regularization parameter to control the model’s complexity, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization capability. By transforming the optimization problem into its dual form and solving it using optimization algorithms, SVR demonstrates robustness against outliers, in this study, SVR plays two primary roles:

-

Feature Importance Evaluation: A linear kernel is employed in SVR to ensure interpretability in feature importance estimation. Under this configuration, the absolute values of the model weights \(\left|{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}\right|\) directly reflect the contribution of each feature to the regression outcome. This enables explicit and stable feature ranking without the need for additional transformations or approximations.

-

Balancing Complexity and Interpretability: Although the underlying system exhibits nonlinear behavior, using nonlinear kernels such as RBF would obscure the direct relationship between input features and model output, making feature scoring less interpretable. Moreover, nonlinear kernels typically entail higher computational overhead, which may be unsuitable for time-sensitive industrial applications such as blast furnace control. Therefore, we deliberately adopt a linear kernel in SVR to maintain computational efficiency and support real-time decision-making.

While linear kernels may not capture all nonlinear dependencies, this choice reflects a trade-off between model complexity and practical interpretability, aligning with the objectives of dynamic feature selection in an industrial setting.

Recursive feature elimination (RFE)

In the prediction of silicon content in molten iron, the primary objectives of feature selection are to enhance the predictive accuracy of the regression model and to improve its interpretability. RFE is an efficient method for feature selection that optimizes model performance by incrementally reducing the number of features, thereby achieving dimensionality reduction and enhancing model efficiency. RFE is predicated on a greedy search algorithm32. The principal steps of the algorithm are as follows:

-

Setp 1 Initialization: A regression model is trained using all available features. For instance, in the ordinary least squares linear regression model, the parameters w can be estimated using Eq. (7):

$$\begin{array}{c}w={\left({X}^{T}X\right)}^{\left\{-1\right\}{X}^{T}y}\end{array}$$(7)where X is the feature matrix, and y is the target variable. For Support Vector Regression (SVR) or other regression models, the corresponding algorithms are employed for training.

-

Setp 2 Feature Importance Assessment: The importance of features is evaluated based on the model’s internal feature importance metrics. In linear regression, the importance of a feature is typically calculated using the absolute value of the model coefficients as shown in Eq. (8). For nonlinear regression models, such as Random Forest Regression, the built-in feature importance metrics of the model are used to compute the importance of each feature

$$\begin{array}{c}{I}_{i}=\left|{w}_{i}\right|\end{array}$$(8)where \({I}_{i}\) denotes the importance of the feature and \({w}_{i}\) represents the model coefficient.

-

Setp 3 Recursive Feature Elimination: Features are sequentially removed based on their importance, starting with the least important. This process is articulated in Eq. (9):

$$\begin{array}{c}{S}^{{^{\prime}}}=S\setminus \left\{f\right\}\end{array}$$(9)where, \(S^{\prime }\) is the new set of features after the removal of feature \(f.\) This process is repeated until \(S^{\prime }\) contains the desired number of features.

-

Setp 4 Performance Evaluation: After each iteration, the model’s performance is assessed to ensure that the reduction in features does not compromise the model’s effectiveness.

-

Setp 5 Final Model Selection: After multiple iterations, the model corresponding to the feature subset that yields the optimal performance is chosen as the final model.

As an extension of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) re-evaluates the significance of features in each fold of the cross-validation process. This methodology involves the repeated assessment of feature importance across k-fold cross-validation and calculates the average cross-validation score for each subset of features. Consequently, this approach allows for the evaluation of performance variation across different models with varying feature subsets, ensuring that the selected feature set exhibits consistent performance across multiple folds. The calculation of the cross-validation score is detailed in Eq. (10).

where, F denotes the number of folds in the cross-validation process, and \({C}_{i}\left(S\right)\) represents the score of the regression model for the i-th fold.

RFE and RFECV offer effective solutions to feature selection problems in machine learning. RFE is adept at rapid feature screening, whereas RFECV enhances the robustness of feature selection through cross-validation, which can improve model performance, mitigate the risk of overfitting, and enhance the interpretability of the model.

In the proposed algorithm, RFE is not only utilized in the initialization phase to filter features but also integrated with the Bayesian updating mechanism to dynamically optimize feature subsets, adapting to the dynamic nature of blast furnace data.

Bayesian online updating (BO)

Bayesian optimization is an efficient method for black-box function optimization, primarily leveraging Gaussian processes to model the objective function. Its core idea is to combine prior distributions with an acquisition function to dynamically update and sample the objective function, minimizing evaluation iterations while locating the global optimum33. The process involves the following key steps:

-

Setp 1 Gaussian Process Modeling: A Gaussian process serves as a surrogate model for the objective function. The Gaussian process regression model can be represented by Eq. (11).

$$\begin{array}{c}f\left(x\right)\sim GP\left(m\left(x\right), k\left(x, {x}^{{^{\prime}}}\right)\right)\end{array}$$(11)where m(x) is the mean function, and \(k\left(x, {x}^{{^{\prime}}}\right)\) is the kernel function.

-

Setp 2 Iterative optimization: The posterior distribution of the objective function is predicted using the Gaussian process, and the next evaluation point is selected through an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement, EI). The Expected Improvement is calculated by Eq. (12)

$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {EI\left( x \right) = \mathbb{E}\left[ {max\left( {0,f^{{\text{*}}} - f\left( x \right)} \right)} \right]} \\ \end{array}$$(12)where \({f}^{*}\) is the best known objective function value.

-

Setp 3 Model update: The results of the new evaluation point are used to update the Gaussian process model. The posterior distribution of the model is updated and can be represented by Eq. (13).

$$f\left(x\right)\mid X,y\mathcal{G}\mathcal{P}\sim m\left(x\right)+K\left(x,X\right)K{\left(X,X\right)}^{-1}\left(y-m\left(X\right)\right),$$$$\begin{array}{c}k\left(x,{x}^{{^{\prime}}}\right)-K\left(x,X\right)K{\left(X,X\right)}^{-1}K\left(X,x\right)\end{array}$$(13)where X is the set of known input points, y is the corresponding target function value, \(K\left(x,X\right)\) is the covariance between the new point and known points, and \(K\left(X,X\right)\) is the covariance matrix of the known points.

Bayesian optimization dynamically adjusts sampling points for efficient global search and optimization of complex objective functions.

In the proposed algorithm, the role of Bayesian methods is not limited to hyperparameter optimization. Instead, they dynamically adjust feature importance distributions to balance the influence of historical data and current observations. Through Bayesian optimization, the algorithm updates feature importance distributions in real-time, achieving a balance between global optimization and local dynamic adaptation, providing dynamic guidance for feature selection.

Our algorithm framework

Overview and design objectives

To address the challenges of complex industrial data, dynamic variability, and nonlinear complexity in blast furnace Silicon content prediction, this study proposes a dynamic feature selection algorithm based on Bayesian dynamic updating and Support Vector Regression Recursive Feature Elimination (SVR-RFE). The algorithm dynamically adjusts feature importance distributions and optimizes feature subsets in real time, significantly improving model performance to meet the demands for accuracy and real-time operation in industrial applications. The primary objectives of the proposed algorithm are as follows:

-

Improve Prediction Accuracy: Dynamically evaluate feature importance and extract the most representative features in real time, reducing the interference of redundant features on the model and thereby enhancing the accuracy of blast furnace temperature prediction.

-

Enhance Dynamic Adaptability: Utilize a Bayesian dynamic updating mechanism combined with batch data processing to adjust feature importance distributions in real time. This enables dynamic optimization of feature subsets, ensuring the model can respond swiftly to changes in operating conditions and adapt to complex environments.

-

Optimize Computational Efficiency: Reduce the dimensionality of input features using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) while employing an online updating strategy to avoid retraining the full model. This significantly improves the algorithm’s efficiency, meeting the real-time prediction requirements of industrial applications.

Beyond the methodological composition, BOSVRRFE introduces several innovations. While prior approaches have employed SVR, RFE, or Bayesian inference independently, our framework reformulates these components into a unified and modular architecture tailored for streaming data scenarios. In particular, BOSVRRFE leverages closed-form Bayesian inference applied to SVR-derived feature importance scores, enabling interpretable and dynamically adjustable feature subsets without full model retraining. Moreover, the framework avoids reliance on deep learning architectures, which often lack transparency, require extensive data and computational resources, and are less suitable for deployment in latency-sensitive industrial systems. BOSVRRFE addresses these limitations by offering a lightweight, scalable, and theoretically grounded solution that facilitates real-time feature selection and robust predictive performance in complex, non-stationary environments.

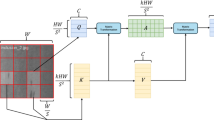

Framework architecture

The proposed BOSVRRFE algorithm integrates support vector regression (SVR), recursive feature elimination (RFE), and Bayesian online updating to support dynamic feature selection in industrial scenarios. It consists of three core modules: Feature Initialization, Feature Importance Updating, and Dynamic Feature Selection. The overall framework is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Framework of the proposed BOSVRRFE algorithm, including offline initialization and online dynamic adaptation stages. And comprises three main modules: Feature Initialization, Feature Importance Updating, and Dynamic Feature Selection.

-

Feature Initialization Module

The objective of the Feature Initialization Module is to construct a foundational framework for feature selection using initial data, selecting key features, and establishing a Bayesian prior distribution for feature importance to support subsequent dynamic adjustments. This module combines SVR and RFE. SVR maps feature to high-dimensional space using kernel functions to capture nonlinear relationships, with the absolute values of weights reflecting feature importance. RFE employs a greedy strategy to recursively remove features contributing the least to the model, yielding the optimal feature subset.

For the initial dataset \({X}_{\text{train}}\) and target values \({y}_{\text{train}}\), a linear kernel SVR model is first trained to obtain weights \(w\) for each feature. RFE ranks the absolute values of \(w\), recursively eliminating less important features, and selects the initial feature subset \({F}_{\text{init}}\). The mean of feature importance is defined as Eq. (14)

where \({w}_{i}\) represents the absolute regression weight of feature \(i\) . Unselected features are assigned a mean of zero. The variance of feature importance is initialized to a large value to reflect uncertainty, as shown in Eq. (15):

The prior mean \({\upmu }_{\text{prior}}\) and variance \({\upsigma }_{\text{prior}}^{2}\) constitute the Bayesian prior distribution for feature importance, providing a basis for subsequent updates.

-

Feature Importance Updating Module

The Feature Importance Updating Module is responsible for dynamically adjusting the feature importance distribution over time. It plays a central role in enabling temporal adaptability by integrating historical importance estimates with new information derived from the most recent data batch. This is achieved through Bayesian updating, which produces a posterior distribution of feature importance that reflects both prior belief and current evidence.

At each time step \(t ,\) a linear kernel SVR model is trained on the newly arrived batch data \(({X}_{\text{batch}}\), \({Y}_{\text{batch}}\) \()\), and the absolute regression weights are treated as the observed importance estimates \({\mu }_{\text{obs}}.\) The prior distribution for each feature is represented by a mean \({\mu }_{{\text{pri}}{\text{or}}}\) and variance \({\sigma }_{\text{prior}}^{2}\), carried over from the previous update. The posterior distribution is computed using the closed-form Bayesian update Eqs. (16):

The posterior variance is updated using Eq. (17):

In this implementation, the observational variance is set as \({\sigma }_{\text{obs}}^{2}=1\), based on the following considerations: First, the input data have been standardized, ensuring that all features have zero mean and unit variance, which naturally aligns the observational noise scale with a unit variance assumption. Second, in industrial process applications, the importance of features typically exhibits relatively small and stable fluctuations over time, making the unit variance assumption both realistic and practically acceptable. Finally, fixing the observational variance simplifies the Bayesian updating process, reduces computational complexity, and avoids the need for additional hyperparameter estimation, thereby enhancing the real-time adaptability of the proposed method. This simplification is widely adopted in probabilistic modeling when features are standardized, as it ensures consistent importance scaling and improves computational stability in online inference settings34,35,36.

The updated posterior mean \({\mu }_{\text{post}}\) captures the temporally smoothed and uncertainty-weighted importance of each feature. To prevent excessive sensitivity to transient fluctuations, we apply smoothing by restricting the updated mean within a confidence interval (e.g., 95%). The resulting posterior distribution is then used in the next module to compute feature scores, serving as the input to dynamic feature subset optimization.

-

Dynamic Feature Selection Module

The Dynamic Feature Selection Module optimizes the feature subset based on updated feature importance distributions. It introduces sparsity constraints and correlation analysis to adjust feature subset size and remove redundant features, ensuring sparsity and effectiveness. Feature importance scores are calculated using the posterior mean and variance, as shown in Eq. (18):

where \({S}_{i}\) is the importance score for feature \(i\) , and \(\varepsilon\) is a small constant to prevent division by zero.

This scoring mechanism is designed to prioritize features with higher estimated contributions and lower associated uncertainty. Specifically, by dividing the posterior mean by the posterior variance plus a small constant, the method effectively captures the signal-to-uncertainty ratio of each feature. Features with a large posterior mean and small variance are favored, ensuring that the selected features are not only strong in predictive power but also reliable. This design balances the strength of feature contributions against the confidence in their estimates, thereby improving the robustness of dynamic feature selection under changing industrial conditions.

The number of dynamically adjusted features \({n}_{\text{dynamic}}\) is determined using Eq. (19):

where, 20 ensures a minimum number of features for low-dimensional data, while 0.6 adjusts the feature subset size based on sparsity constraint. The choice of 20 as the minimum feature number is based on domain knowledge and empirical evaluation: in blast furnace operation datasets, retaining at least 20 features ensures that key variables governing the process are adequately represented, preventing critical information loss and maintaining predictive robustness even under reduced dimensionality conditions. Features with correlations above a threshold (e.g., 0.9) are removed, retaining those with higher importance scores. The correlation threshold of 0.9 is selected based on domain knowledge and statistical considerations, as feature pairs with correlation coefficients exceeding 0.9 are generally regarded as highly redundant in industrial process data. Setting this threshold helps eliminate redundant information while preserving the essential diversity among selected features, thereby enhancing model generalization and stability. The top \({n}_{\text{dynamic}}\) features are selected to update the feature subset \({F}_{\text{selected}}\).

The Feature Initialization Module uses SVR and RFE to establish an initial feature selection framework and constructs Bayesian prior distributions. The Feature Importance Updating Module dynamically adjusts feature importance using new data, adapting to variations in feature contributions. The Dynamic Feature Selection Module optimizes the feature subset using sparsity constraints and correlation analysis. Together, these modules provide a precise and efficient dynamic feature selection method for blast furnace temperature prediction.

Real-time execution and deployment considerations

To enable real-time and robust deployment of the proposed BOSVRRFE framework in industrial settings, the algorithm is designed to operate in a streaming environment where the feature subset is updated continuously with each new batch of data. This ensures that the prediction model consistently uses the most relevant features under evolving operational conditions. Feature importance is incrementally adjusted through Bayesian updating without requiring access to the full historical dataset, which greatly improves computational efficiency.

Regarding model execution, two feature integration strategies are considered. The first is an online retraining mode, in which the prediction model (e.g., SVR) is retrained for each batch using the newly selected feature subset. This allows the model to stay aligned with the updated features and maintain adaptability. The second is a dynamic feature switching mode, in which a pre-trained model dynamically changes its input layer to accommodate the current top-ranked features without full retraining. In our implementation, we adopt the online retraining approach as it strikes a practical balance between accuracy and computational cost. This entire process is fully automated and synchronized with the industrial control system’s data acquisition frequency, ensuring that each update and prediction cycle is completed within the required time frame, without manual intervention.

To further enhance the algorithm’s robustness and deployment flexibility, several engineering mechanisms are incorporated. First, key hyperparameters—including the forgetting factors (α, β), SVR regularization coefficient (C), and kernel parameters—can be automatically optimized using Bayesian optimization techniques to balance prediction performance and computational efficiency. Second, in cases of abnormal furnace conditions or sensor failures, a rollback mechanism is implemented to restore the feature subset or prior distribution to a previously stable state. When excessive fluctuation in feature importance is detected, the system may trigger a full reset to maintain output stability. Finally, although the online phase operates with low computational complexity by processing only the current feature subset, parallel or distributed computing frameworks can be adopted to ensure real-time performance in extremely high-dimensional scenarios.

Summary and comparison

In summary, the proposed BOSVRRFE framework integrates nonlinear modeling via support vector regression, Bayesian sequential updating, and redundancy-aware feature selection into a unified, dynamic process. It effectively tracks feature importance with uncertainty quantification and adaptively refines the feature subset based on temporal relevance and correlation analysis. Compared with recent deep learning models for silicon content prediction—which often require large volumes of labeled data, incur high computational costs, and lack interpretability—BOSVRRFE offers a lightweight and transparent alternative suitable for industrial deployment. Furthermore, unlike most streaming or dynamic feature selection methods that rely on heuristic scoring or shallow classifiers, BOSVRRFE embeds learning directly into the selection process, enabling real-time responsiveness and stable predictive performance under noisy, high-dimensional, and evolving operating conditions.

Industry experimental

This experiment aims to validate the effectiveness of the Dynamic Bayesian Fusion SVRRFE feature selection algorithm in predicting Silicon content in blast furnace. Through this experiment, we seek to evaluate the algorithm’s performance in dynamic operating conditions, including its real-time adaptability to changes in feature importance, the sparsity and stability of selected features, and improvements in prediction accuracy. Additionally, by comparing this algorithm with static feature selection methods and modeling without feature selection, we analyze its comprehensive performance in prediction accuracy, feature optimization, and computational efficiency, providing reliable technical support for real-time industrial blast furnace prediction.

Data description

Data source

The data were sourced from Blast Furnace No. 5 of a steel company in China, with a volume of 1,080 cubic meters. This furnace, with excellent equipment conditions and highly independent operational data, was chosen as the pilot for experimental analysis. This study is based on historical production data, filtering 300,000 records from three months of operation. The data are categorized as follows:

-

Sensor Data: Collected by sensors at millisecond-level frequency, including dynamic parameters such as pulverized coal injection rates, air volumes, and pressure differences. These data are organized in time-series format.

-

Manual and ERP System Data: Which includes manually recorded shift reports and laboratory assay data extracted from the ERP system (e.g., silicon content in molten iron), used to supplement and validate the sensor data.

These datasets provide a reliable foundation for experimenting with the dynamic feature selection model, particularly the high-frequency collection and time-series characteristics of sensor data, which support the model’s real-time processing and delayed feature analysis.

Data preprocessing

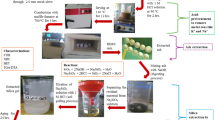

Blast furnace production data exhibit multi-source heterogeneity, including differences in frequency, format, and precision. To ensure data quality and consistency, the following preprocessing steps were applied:

-

Sensor Data Standardization: Millisecond-level recorded data were averaged to one-minute intervals and stored as time series, resolving frequency inconsistencies.

-

Interpolation and Alignment for Discrete Data: Time-series interpolation and padding were performed on discrete ERP system data to synchronize with sensor data.

-

Anomaly Handling: Based on instrument ranges and expert knowledge, abnormal data were removed, such as negative pulverized coal injection rates, unusually high air volumes, and unreasonable readings caused by sensor calibration issues.

-

Outlier Removal: The three-sigma rule was applied to remove extreme outliers, ensuring the rationality of analysis results. For example, as illustrated in 0, outlier analysis was conducted for molten iron assay data, including Si, P, S, and Mn content.

As depicted in Fig. 3 The green dashed lines represent the three-sigma range. Blue dots indicate normal data, while red dots indicate identified outliers. Outliers such as Si content exceeding 1.5, P content exceeding 0.15, S content exceeding 0.14, and Mn content exceeding 0.5 were successfully removed. Normal data (blue dots) were concentrated within the green dashed line range.

Through these preprocessing steps, abnormal data were effectively cleaned, inconsistencies in multi-source heterogeneous data were resolved, and data quality and reliability were significantly improved. These preparations provide a solid foundation for training and analyzing the dynamic feature selection model.

Data exploring

To elucidate the relationships between various indicators and molten iron silicon (Si) content, we employed time-series analysis and scatter plot techniques to preliminarily investigate the potential correlations between key variables and Si content. As illustrated in Fig. 3, we focused on key variables such as wind volume, pressure differential, coal injection rate, and theoretical combustion temperature, and explored their dynamic relationships with Si content over time.

As depicted in Fig. 4, the relationships between the exemplary sample parameters and the silicon content in molten iron are illustrated.

-

Wind Volume and Silicon Content: The trend lines exhibit a consistent pattern, albeit with a subtle correlation, suggesting a modest relationship between the two. This indicates that incorporating features related to wind volume in subsequent feature engineering may be beneficial.

-

Pressure Differential and Silicon Content: The trend lines demonstrate a positive correlation, with fluctuations in the average pressure differential correlating with corresponding changes in silicon content. This suggests that features reflecting the average pressure differential could be instrumental in explaining variations in silicon content.

-

Coal Injection and Silicon Content: The trend lines do not readily reveal a direct relationship. However, upon shifting the coal injection trend line by approximately two hours, a similar trend emerges, indicating a delayed effect of coal injection on furnace temperature. Thus, it is reasonable to include features related to coal injection in feature engineering.

-

Theoretical Combustion Temperature and Silicon Content: Analysis of the trend lines reveals a certain lag in the response of silicon content to changes in theoretical combustion temperature, suggesting that the latter contains information predictive of future silicon content variations. Therefore, including theoretical combustion temperature in feature engineering is valuable.

Through these exploratory analysis steps, we have concluded that the mean values, variations, and trend information of various parameters are significantly important for predicting changes in the silicon content of molten iron. We segmented the data into multiple phases and constructed distinct features for each phase, resulting in a comprehensive dataset with 184 feature variables. These feature variables encompass multiple dimensions, including raw material properties, process conditions, and production outcomes. Table 1 lists the details of the feature descriptions.

Data normalization

In this pater, to mitigate the impact of features with different scales on model performance and to ensure that data is processed on a unified scale, we employed Min–Max Normalization. This normalization technique linearly transforms the values of the original data into a specified range, typically [0, 1], facilitating subsequent data processing and analysis. The normalization process follows Eq. (20):

where , \({x}_{ij}\) represents the observed value of the \(i\) sample on the j-th feature in the original dataset, \({x}_{ij}^{*}\) denotes the normalized value, \(\text{max}\left({x}_{ij}\right)\) and \(\text{min}\left({x}_{ij}\right)\) are the maximum and minimum values of the \(j\) feature across the entire dataset, respectively.

Through this normalization, we ensure that the values of each feature fall within the [0, 1] range, which not only aids in accelerating the convergence rate of certain algorithms but also helps to prevent bias in weights due to differences in feature scales.

Experimental methodology and procedure

This experiment is designed to evaluate the proposed BOSVRRFE (Bayesian Online SVR-RFE) feature selection framework, focusing on its dynamic adaptability and feature optimization capabilities for blast furnace temperature prediction under streaming data conditions. The experiment is divided into two phases: the Initialization Phase and the Dynamic Adjustment Phase.

Initialization phase

The cumulative contribution rate method is applied with a 90% threshold to select important features from 184 candidate features. Feature importance means are computed using a linear kernel SVR, and the initial variance is set to \({10}^{6}\) to reflect high uncertainty. The selected feature subset is used to train a baseline model, and initial performance metrics (MSE, MAE, and \({R}^{2}\)) are recorded.

Dynamic adjustment phase

The remaining data are sequentially processed in batches according to their temporal order. For each batch, the importance distribution of all features is recalculated, and Bayesian updating is applied to dynamically adjust the mean and variance of feature importance. Based on the updated posterior scores, a new feature subset is selected, and highly correlated features are removed through threshold-based correlation analysis. The prediction model is then retrained using the refined subset, and key indicators such as feature count, performance metrics, and runtime are recorded. In addition, the frequency with which each feature is selected across all batches is analyzed to evaluate the temporal stability of important variables.

This experimental setup provides a robust foundation for assessing both the effectiveness of the feature selection mechanism and the overall predictive performance of BOSVRRFE in realistic industrial scenarios.

Baseline selection and justification

To ensure a fair and meaningful comparison, several widely used, interpretable, and computationally efficient baseline methods were selected. These baselines are representative of common approaches to feature selection or dimensionality reduction and are suitable for real-time industrial applications. The baseline methods include:

-

No Feature Selection: A full feature model using all input variables.

-

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): A static wrapper-based method applied once before model training.

-

Lasso Regression: A sparsity enforcing linear model using L1 regularization.

-

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A dimensionality reduction method that projects feature into uncorrelated principal components.

-

TreeBased Feature Importance: A selection based on feature importance scores from gradient boosted decision trees.

Although the BOSVRRFE framework is model-agnostic and can be integrated with any supervised learning algorithm that supports explicit feature subset input, XGBoost was selected as the predictive model in this study based on both methodological and practical considerations. XGBoost has demonstrated strong performance on structured industrial data, particularly in handling sparse and high-importance feature subsets. It also supports rapid retraining, which aligns well with the batch-wise update mechanism employed by BOSVRRFE.

Deep learning models such as LSTM and Transformer architectures were not included in the comparative analysis. While these models are highly effective for end-to-end prediction, they are not inherently designed for explicit, interpretable feature selection—the central focus of this work. Moreover, deep learning models often require large volumes of labeled data, introduce significant inference latency, and pose considerable deployment complexity, making them less suitable for real-time, high-frequency industrial systems such as blast furnace control.

Most selected baselines are static methods, reflecting the practicality and maturity of interpretable techniques commonly used in real-time applications. Existing dynamic feature selection approaches such as Online Streaming Feature Selection (OSFS) and Alpha-Investing37,38 are primarily designed for classification tasks and rely on heuristic updates. They lack explicit importance scoring and are generally unsuitable for regression scenarios requiring stable and transparent evaluation.

BOSVRRFE is tailored for regression tasks with interpretable, batch-wise updates. As such, classification-oriented dynamic methods were excluded. Future work may consider comparisons with regression-compatible dynamic approaches as they become available and practically viable.

In summary, the use of XGBoost and the selected classical baselines ensures alignment with the problem setting of interpretable, efficient, and dynamically adaptable feature selection, providing a fair and practically relevant comparison for evaluating the performance of the proposed BOSVRRFE framework.

Evaluation and validation

To validate the effectiveness of the feature selection, we applied the trained XGBoost model to the test dataset and calculated key performance metrics, including Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Coefficient of Determination (\({R}^{2}\)). Together, these metrics form a multidimensional evaluation system that reflects the model’s predictive power and accuracy from various perspectives.

MSE

This metric measures the average of the squares of the differences between the predicted and actual values. It penalizes larger errors more heavily, thus providing a sensitive reflection of the model’s predictive performance on extreme values, MSE is defined as Eq. (21)

where, n is the number of samples, \({y}_{i}\) is the actual value of the i-th observation, \({\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted value of the i-th observation.

MAE

This metric calculates the average of the absolute differences between the predicted and actual values, giving equal weight to errors of all magnitudes and providing an intuitive measure of the model’s predictive accuracy, MAE is defined as Eq. (22)

where, n is the total number of predictions, \({y}_{i}\) is the actual value of the ii-th observation, \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) is the predicted value of the i-th observation, \(\left|{y}_{i}- \widehat{{y}_{i}}\right|\) represents the absolute difference between the actual and predicted values.

\({{\varvec{R}}}^{2}\)

The \({R}^{2}\) is an important metric for evaluating the goodness-of-fit of regression models, measuring the model’s ability to explain the variance of the target variable. Its value ranges from [0, 1], where an \({R}^{2}\) closer to 1 indicates better fit to the target variable. \({R}^{2}\) is specifically defined as Eq. (23):

where,\({y}_{i}\): Actual value of the target variable, \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) : Predicted value of the target variable, \(\overline{y }\) : Mean of the actual values. The numerator represents the squared error between the predicted and actual values, while the denominator represents the total variance of the actual values.

-

\({R}^{2}=1\) : The model perfectly fits the actual data, indicating the best performance.

-

\({R}^{2}=0\): The model’s performance is equivalent to using the mean of the target variable for prediction.

-

\({R}^{2}<0\) : The model performs worse than simply predicting with the mean of the target variable.

As a standardized metric, \({R}^{2}\) facilitates performance comparison between different models and provides an intuitive measure of a model’s ability to explain the variance of the target variable. However, \({R}^{2}\) has limited applicability for classification models or highly nonlinear models.

Through the steps, we have been able to not only validate the impact of feature selection on model performance but also to comprehensively assess the performance of the XGBoost model on a specific dataset. These evaluation results are significant for guiding future model optimizations and feature engineering endeavors.

Experimental results

Initialization phase analysis

During the initialization phase, feature subsets were selected using different cumulative contribution thresholds (0.80, 0.85, and 0.90), resulting in 78, 92, and 109 initial features, respectively. A 90% contribution threshold was ultimately adopted, yielding 109 initial features. The baseline model’s performance with this feature subset was as follows: \({\text{MSE}}\)= 0.0031, MAE = 0.0439, and \({R}^{2}\) = 0.6820. These results demonstrate that the initial feature subset captures most of the important information for the target variable, providing a strong foundation for subsequent dynamic adjustments. The impact of the contribution threshold on the number of initial features is shown in Fig. 5.

Dynamic feature selection phase analysis

During the dynamic phase, the number of selected features was dynamically adjusted within a range of 10 to 90. Performance analysis revealed that when the feature count was low (10–30 features), model performance deteriorated significantly, with \({R}^{2}\) falling below 0.65. However, as the feature count increased to 80–90, model performance improved steadily, with MSE and MAE reaching optimal levels. For example:

-

In Batch 1, with 80 features, MSE = 0.0030, \({R}^{2}\) = 0.6922.

-

In Batch 2, with 90 features, \(MAE\)= 0.0031, \({R}^{2}\) = 0.6809.

This trend indicates that dynamic feature selection effectively approaches the optimal feature subset while balancing sparsity control and performance optimization, which is shown in Fig. 6

Across batches, the dynamic method exhibited stable performance, with \({\text{MSE}}\) and MAE fluctuating between 0.0030–0.0035 and 0.0416–0.0460, respectively, and \({R}^{2}\) stabilizing in the range of 0.63–0.69. Optimal performance was consistently achieved with 80–90 features, which is shown Fig. 7 This demonstrates the method’s ability to adapt to changes in feature importance under dynamic conditions.

Balancing sparsity and performance

The proposed dynamic feature selection method achieves a good balance between model sparsity and prediction performance. As shown in Fig. 8, using fewer features (e.g., 10–30) does not necessarily result in degraded accuracy. In fact, the model achieves its best performance in Batch 7 when using only 10 features (R2 = 0.6843, MSE = 0.0030), outperforming the configuration with 90 features (R2 = 0.6703, MSE = 0.0032).

This phenomenon may appear counterintuitive at first, but it is consistent with well-known principles in feature selection and generalization. Incorporating a large number of features can introduce redundancy, irrelevant variables, or noise—especially in real-world industrial datasets—leading to increased variance and reduced robustness. This effect is particularly pronounced in industrial systems such as blast furnace processes, where input features often suffer from sensor noise, delayed feedback, and strong correlations due to overlapping measurements. As the number of features increases, the risk of multicollinearity and model overfitting also rises.

By contrast, a compact set of highly informative features can help the model generalize better and avoid overfitting. The results confirm that BOSVRRFE effectively identifies such compact and relevant subsets, enabling high prediction accuracy even under strong sparsity constraints. This sparsity-aware behavior enhances the model’s suitability for real-time industrial applications, where low-latency and efficient computation are essential.

In summary, the dynamic feature selection method dynamically adjusts feature subsets to balance sparsity control and performance optimization. Compared to the initialization phase, the dynamic method exhibited high adaptability and stability during multi-batch streaming data adjustments. The experimental results confirm that dynamic feature selection effectively responds to evolving feature importance, making it a robust and efficient solution for prediction tasks in dynamic environments.

Comparative experimental analysis

Performance validation

This study evaluates the Dynamic (BOSVRRFE) method against several static feature selection methods, including Lasso, PCA, Tree-Based, and Relief, to assess its performance in dynamic scenarios. The evaluation focuses on three aspects:

-

(1)

Prediction Performance measured using Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Coefficient of Determination (\({R}^{2}\)).

-

(2)

Inter-Batch Stability assessed using the standard deviation of \({R}^{2}\).

-

(3)

Feature Sparsity and Selection Capability, examining the number of selected features to evaluate the balance between sparsity and information retention.

MSE, MAE, R2 comparison results

The Dynamic (BOSVRRFE) method consistently outperformed static feature selection methods across all evaluation criteria. The result listed in Table 2:

As shown in Table 2 the proposed BOSVRRFE method demonstrates clear advantages over static feature selection approaches across multiple evaluation dimensions.

-

Prediction Performance:

BOSVRRFE achieved the highest predictive accuracy, with an R2 of 0.6710, MSE of 0.003159, and MAE of 0.04385. Its dynamic feature adjustment mechanism enables the model to effectively track evolving feature importance under varying industrial conditions. In contrast, static methods presented distinct trade-offs. The No Selection approach retained all 184 features and achieved a relatively high R2 (0.6661), but at the cost of increased redundancy and complexity. Lasso and Relief reduced feature count significantly (38 and 36 features, respectively), but their performance dropped accordingly (R2 = 0.6469 and 0.6437), indicating the exclusion of useful but less dominant features. PCA yielded the poorest performance (R2 = 0.0359), reflecting information loss due to aggressive dimensionality reduction. Tree-based selection, though moderately sparse (19 features), also underperformed (R2 = 0.6386), likely due to over-concentration on a narrow set of features.

-

Stability and Sparsity:

BOSVRRFE maintained strong performance consistency across data batches, with a low R2 standard deviation of 0.0166, highlighting its robustness to temporal variation. Static methods, which relied on fixed feature sets, lacked such adaptability and exhibited greater performance variance. In terms of sparsity, BOSVRRFE selected an average of 98 features—significantly fewer than No Selection (184) yet more balanced than Lasso (38) and Relief (36). PCA and Tree-Based methods selected even fewer features (10 and 19), but their excessive sparsity led to significant performance degradation.

Overall, BOSVRRFE outperformed static baselines by achieving a superior trade-off between prediction accuracy, feature sparsity, and inter-batch stability. Its dynamic selection mechanism enables it to maintain high predictive performance under changing process conditions, whereas static methods either retained too many irrelevant features or were overly sparse, compromising model generalization.

R2 gain trend analysis

The Fig. 9 illustrates the \({R}^{2}\) gain trends of the Dynamic method compared to static methods across batches.

-

Significant Gains: Compared to PCA, the Dynamic method achieved the largest gains across all batches, with increases consistently exceeding 0.6, showcasing its ability to dynamically adjust feature subsets and improve PCA performance significantly.

-

Balance of Sparsity and Performance: Compared to Lasso, the Dynamic method showed smaller but more stable gains (fluctuations of 0.03–0.05), highlighting its ability to balance sparsity control and performance improvement.

-

Adaptability: Compared to Tree-Based and Relief methods, the Dynamic method exhibited consistent gains (approximately 0.02–0.07), reflecting its superior adaptability in dynamically adjusting feature subsets.

In summary, the Dynamic method consistently outperformed static methods in \({R}^{2}\) gain trends, effectively balancing sparsity, performance, and adaptability to maintain robust predictions across dynamic scenarios.

Performance comparison summary

The Dynamic (BOSVRRFE) method demonstrated significant advantages in dynamic scenarios over static methods in three key areas:

-

(1)

Predictive Performance: Highest \({R}^{2}\) average and lowest \({\text{M}}{\text{SE}}\) and MAE, confirming its effectiveness in dynamically adjusting feature subsets to improve prediction accuracy.

-

(2)

Inter-Batch Stability: Small \({R}^{2}\) standard deviation, indicating robust performance across batches and adaptability to changes in the target variable.

-

(3)

Sparsity and Information Retention: Balanced feature count (80–90 features), achieving a compromise between sparsity control and retention of critical information. Static methods, limited by fixed feature subsets, lacked this dynamic adaptability, resulting in reduced performance in dynamic scenarios. PCA suffered severe performance degradation due to information loss.

In summary, The Dynamic (BOSVRRFE) method significantly outperformed static methods in dynamic scenarios by dynamically adjusting feature subsets to enhance model performance. It effectively extracts the most relevant features and leverages the efficient modeling capabilities of XGBoost, achieving optimal balance between prediction accuracy, sparsity, and interpretability. The results in Table 1 validate the method’s superiority in blast furnace silicon content prediction tasks.

Conclusion and future work

This study proposed a Dynamic BOSVRRFE feature selection method to address challenges in dynamic feature importance and complex industrial data for blast furnace silicon content prediction. By combining SVR, RFE, and BO updating, the method dynamically adjusts feature subsets, achieving superior predictive accuracy (\({R}^{2}\) = 0.671037, MSE = 0.003159, MAE = 0.043850), strong adaptability (\({R}^{2}\) standard deviation = 0.016619), and an effective balance between sparsity and information retention (98 average features). Compared to static methods like PCA and Lasso, it demonstrated significant advantages in dynamic industrial environments.

In designing this method, we deliberately avoided using fully Bayesian SVR formulations, such as those based on evidence maximization, due to their computational complexity and lack of explicit feature control. Instead, BOSVRRFE maintains modularity by combining interpretable SVR-based weights with lightweight Bayesian updates, making it more suitable for real-time deployment in industrial systems.

Future research could focus on extending the method to other industrial scenarios characterized by complex and evolving data, integrating it with advanced models such as deep learning for further accuracy improvements, and developing real-time deployment capabilities for immediate decision-making in industrial systems. The proposed method provides a robust and efficient solution for dynamic feature selection, offering significant potential to enhance predictive modeling, operational efficiency, and decision-making in complex industrial environments.

Data availability

The raw data used in this study originate from real-world industrial production en-vironments and cannot be publicly disclosed due to commercial sensitivity and confi-dentiality agreements. However, intermediate datasets that were anonymized and pro-cessed during the research workflow may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Access to these data will be subject to prior review and compliance with applicable confidentiality and data protection obligations.

References

Geerdes, M. et al. Modern Blast Furnace Ironmaking: An Introduction 4th edn. (IOS Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.3233/STAL9781643681238.

Liu, Y., Zhang, H. & Shen, Y. A data-driven approach for the quick prediction of in-furnace phenomena of pulverized coal combustion in an ironmaking blast furnace. Chem. Eng. Sci. 260, 117945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2022.117945 (2022).

Wang, Ht. et al. Current status and development trends of innovative blast furnace ironmaking technologies aimed to environmental harmony and operation intellectualization. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 24, 751–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1006-706X(17)30115-2 (2017).

Navarro, L. C. et al., Temperature prediction in blast furnaces: A machine learning comparative study. In 2022 35th SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images (SIBGRAPI), Natal, Brazil 192–197 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/SIBGRAPI55357.2022.9991787

Li, J. et al. Feature selection: A data perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 50(6), 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1145/3136625 (2017).

Joe Qin, S. Survey on data-driven industrial process monitoring and diagnosis. Ann. Rev. Control 36(2), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2012.09.004 (2012).

Rahmaninia, M. & Moradi, P. OSFSMI: Online stream feature selection method based on mutual information. Appl. Soft Comput. 68, 733–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2017.08.034 (2018).

Yu, L. & Liu, H. Efficient feature selection via analysis of relevance and redundancy. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 5, 1205–1224 (2004).

Brown, G., Pocock, A., Zhao, M.-J. & Luján, M. Conditional likelihood maximisation: A unifying framework for information theoretic feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 13, 27–66 (2012).

Stein, S., Leng, C., Thornton, S. & Randrianandrasana, M. A guided analytics tool for feature selection in steel manufacturing with an application to blast furnace top gas efficiency. Comput. Mater. Sci. 186, 110053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.110053 (2021).

Wang, Y., Gao, C. & Liu, X. Using LSSVM model to predict the silicon content in hot metal based on KPCA feature extraction. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 59(2), 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.721.461 (2012).

Wang, X., Hu, T. & Tang, L. A mult objective evolutionary nonlinear ensemble learning with evolutionary feature selection for silicon prediction in blast furnace. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2021.3059784 (2022).

Jiang, K. et al. Classification of silicon content variation trend based on fusion of multilevel features in blast furnace ironmaking. Inf. Sci. 521, 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.02.039 (2020).

Bolón-Canedo, V., Sánchez-Maroño, N. & Alonso-Betanzos, A. Feature selection for high-dimensional data. Prog. Artif. Intell. 5, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13748-015-0080-y (2016).

Guyon, I. & Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 1157–1182. https://doi.org/10.1145/944919.944968 (2003).

Venkatesh, B. & Anuradha, J. A review of feature selection and its methods. Cybern. Inf. Technol. 19(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.2478/cait-2019-0001 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Feature selection: A data perspective. ACM Comput. Surv. 50(6), Article 94. https://doi.org/10.1145/3136625 (2017).

Hu, J. et al. Point and interval prediction of aircraft engine maintenance cost by bootstrapped SVR and improved RFE. J. Supercomput. 79, 7997–8025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-022-04986-3 (2023).

Goli, S., Mahjub, H., Faradmal, J., Mashayekhi, H. & Soltanian, A.-R. Survival prediction and feature selection in patients with breast cancer using support vector regression. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2016, Article 2157984, 12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2157984

Fang, J. & Tai, D. Evaluation of mutual information, genetic algorithm and SVR for feature selection in QSAR regression. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 8(2), 107–111. https://doi.org/10.2174/157016311795563839 (2011).

Wang, M. & Barbu, A. Online feature screening for data streams with concept drift. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. early access (2022).

Haug, J., Pawelczyk, M., Broelemann, K. & Kasneci, G. FIRES: Feature importance ranking for explainable sample-efficient learning. KDD 2020 (2020).

Sun, Y., Qin, W., Hu, J., Xu, H. & Sun, P. Z. H. A causal model-inspired automatic feature selection method for developing data-driven soft sensors. Engineering 22(3), 82–93 (2023).

Wang, X., Hu, T. & Tang, L. A multiobjective evolutionary nonlinear ensemble learning with evolutionary feature selection for silicon prediction in blast furnace. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33(5), 2080–2093 (2021).

Zhang, L., et al. Time series prediction of silicon content in blast furnace based on LSTM network. J. Iron Steel Res. (2020)

Yang, C., et al. CNN-Based Feature Learning for Blast Furnace Parameter Prediction. Control Engineering of China (2021).

Zhao, X. et al. A hybrid CNN-LSTM model for soft sensor application in blast furnace. J. Process Control 108, 34–45 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Attention-based temporal convolutional networks for silicon content prediction in ironmaking. Comput. Chem. Eng. 174, 108054 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Transformer-based modeling for dynamic prediction of hot metal composition in blast furnace. IEEE Access 11, 14475–14488 (2023).

Awad, M. & Khanna, R. Support vector regression In Efficient Learning Machines (Apress, Berkeley, CA, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4302-5990-9_4

Smola, A. J. & Sch√∂lkopf, B. A tutorial on support vector regression. Stat. Comput. 14(3), 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:STCO.0000035301.49549.88 (2004).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Linear model selection and regularization. In An Introduction to Statistical Learning. Springer Texts in Statistics, vol 103 (Springer, New York, NY, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7138-7_6

Shahriari, B., Swersky, K., Wang, Z., Adams, R. P. & de Freitas, N. Taking the human out of the loop: A review of Bayesian optimization. Proc. IEEE 104(1), 148–175. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2015.2494218 (2016).

Garnett, R. Bayesian Optimization (Cambridge University Press, 2023) (ISBN: 9781108425780).

Ghahramani, Z. Probabilistic machine learning and artificial intelligence. Nature 521(7553), 452–459. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14541 (2015).

Broderick, T., Boyd, N., Wibisono, A., Wilson, A. C. & Jordan, M. I. Streaming variational Bayes. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 26 (2013). https://arxiv.org/abs/1307.6769

Wu, X., Yu, K., Ding, W., Wang, H. & Zhu, X. Online feature selection with streaming features. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 35(5), 1178–1192. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2012.197 (2013).

Zhou, J., Foster, D. P., Stine, R. A. & Ungar, L. H. Streaming feature selection using alpha-investing. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery in Data Mining 384–393 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1145/1081870.1081914

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junyi Duan conducted all aspects of the research and authored the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article