Abstract

Cholesterol metabolism-related genes (CMRGs) have been associated with osteoarthritis (OA), but their specific regulatory mechanisms remain unclear. This study aimed to investigate the role of CMRGs in OA and provide new insights into its treatment. In this study, two OA datasets, GSE55457 and GSE55235, were applied, which contained the transcriptome data of 10 OA samples and 10 control samples (synovial tissue) respectively. Using these two OA datasets and CMRGs, 21 candidate genes were identified by overlapping CMRGs and differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Protein–protein interaction networks were constructed, revealing interactions among candidate genes. Three machine learning algorithms identified ATF3, CHKA, CLU, CTNNB1, and FASN as potential biomarkers. Further evaluation in two datasets confirmed ATF3, CLU, and FASN as biomarkers, with quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) results showing elevated CLU and decreased ATF3 and FASN expression in OA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and a nomogram model demonstrated high accuracy in predicting OA. Among them, in the GSE55457 dataset, the Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of ATF3 was 0.78 (95% CI 0.71–0.85), the AUC value of CLU was 0.82 (95% CI 0.75–0.89), and the AUC value of FASN was 0.76 (95% CI 0.69–0.83). The AUC value of the nomogram model based on these biomarkers in the training set was 0.90 (95% CI 0.80–0.90), and the slope of the calibration curve was close to 1. Immunocorrelation analysis revealed favorable correlations between ATF3, FASN, and immune cell activities. In conclusion, ATF3, CLU, and FASN were identified as cholesterol metabolism biomarkers in OA, offering new perspectives on the relationship between CMRGs and OA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disease in the world and the most common age-related degenerative disease of total joints. Pain, activity limitation, and joint deformation are the most common clinical symptoms, and they have an extensive effect on OA patients’ quality of life and work1. OA is mainly manifested as local joint degenerative lesions that causes progressive articular cartilage deterioration, osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, synovitis, and meniscus degeneration2,3. Furthermore, genetic predisposition, gender, age, joint position, and joint misalignment have been considered risk factors for the development of OA4,5,6. Over 240 million people globally are impacted with OA7. In a large cohort study, the prevalence of symptomatic and radiographic OA was 13.5% and 18.7%8 in males and females, respectively. It ranks sixth in Asia and eleventh in the world in terms of years of disability9. Pain and loss of function can be debilitating; Not only does osteoarthritis seriously impacts an individual’s standard of life, but it also throws an extensive medical burden on patients10. For the time being, the main treatment modalities include lifestyle changes, surgery and medication11. However, regardless of the method used, the treatment results are not perfect, and there are still many patients whose pain symptoms are not relieved obviously after treatment. Therefore, new advances in the for diagnosis and treatment of OA are urgently needed.

Cholesterol is a lipid substance in human blood, usually synthesized by the liver or ingested from food, which plays an important role in the normal growth and development of the human body. Cholesterol mainly acts to produce cholic acid, form cell membrane, and synthesize hormones. Over the past few years, a large number of animal studies have been conducted to reveal the role of cholesterol in the pathogenesis of OA12,13. Meanwhile, a cross-sectional study in South Korea showed a positive correlation between high cholesterol and OA pain14. It has been noted that cholesterol metabolism and related genes were closely related to the development of OA, however the specific mechanism is still debated15. Although OA is currently considered to be associated with metabolic disorders, Some studies have also revealed the molecular mechanisms by which cholesterol metabolism disorders lead to OA16. However, further in-depth research and exploration are still needed in these areas.

As objective measurement indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic mechanisms, or responses to therapeutic intervention drugs, biomarkers have attracted increasing attention in recent years for their roles in the diagnosis, disease progression, and treatment of OA. A number of studies have explored the value of biomarkers in predicting the severity of clinical diseases17.

In addition, machine learning has also been widely applied in the field of OA diseases18. Three algorithms, namely LASSO, SVM-RFE, and Boruta, are relatively common methods in machine learning. LASSO is a linear regression analysis method. By adding a regularization term (L1 penalty term) to the regression model, it can simultaneously achieve variable selection and regression analysis19; SVM-RFE is a feature selection method based on support vector machines. It recursively removes the features that contribute the least to classification, gradually reduces the size of the feature set, and finally selects the features that are most valuable for classification20; Boruta is a feature selection algorithm based on random forests, which evaluates the importance of each feature by introducing "shadow features" (i.e., randomly permuted features)21. These methods provide effective tools and ideas for the accurate prediction of relevant biomarkers and their disease progression22.

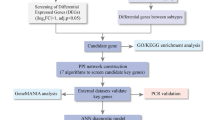

In this study, we intended to explore the mechanism of CMRGs in osteoarthritis and provide new ideas for the treatment of OA. Therefore, based on the transcriptome data of 20 OA patients and 20 normal controls in the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database, through gene differential expression analysis and a series of bioinformatics means such as Gene Ontology (GO)/Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis, and machine learning, this study comprehensively explored the expression, function, and immune regulation of cholesterol metabolism-related biomarkers ATF3, CHKA, CLU, CTNNB1, and FASN, to reveal their potential roles and molecular mechanisms in OA.

Materials and methods

Data source

The GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds) yielded two datasets relating to OA (GSE55457, GSE55235, GSE12021, GSE51588 and GSE98918). Both GSE55457 (GPL96) and GSE55235 (GPL96) have 10 OA and 10 control samples (synovial tissues) The GSE12021 database contained 10 OA samples and 9 control samples. The OA cartilage dataset (GSE51588) contained 40 OA samples and 10 control samples, and the OA meniscus dataset (GSE98918) contained 12 OA samples and 12 control samples. The 123 cholesterol CMRGs were identified in the published literature23 (Table S1).

Differential expression and enrichment analysis

The GSE55457 dataset was investigated using the limma package (v 3.52.4)24 to discover differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between OA and controls (|log2FC|> 0.5, p value < 0.05). Then the DEGs were visualized with ggplot2 (v 3.3.6)25 and complexpheatmap (v 1.0.12)26. The overlapping genes (candidate genes) of CMRGs and DEGs were evaluated with Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)27,28,29 via clusterProfiler (v 4.4.4)30 to determine their functions and pathways (p < 0.05). Ultimately, candidate genes were placed into the Search Tool for Retrieving Interacting Genes (STRING, https://string-db.org/) database to investigate the interactions of proteins encoded by candidate genes (medium confidence > 0.4).

Machine learning for filtering candidate biomarkers

To look for candidate biomarkers associated with cholesterol metabolism in OA, three machine learning procedures employ genes with connections in PPI networks. First, to reduce the feature dimensions, a Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) analysis was performed using glmnet (v 4.1–4)31. The parameter "family" was set to "binomial", and the cross-validation was set with 3 folds. The genes with the smallest Lambda value were selected as the LASSO feature genes. Subsequently, for effective feature selection, the e1071 (v 1.7–13)32 package was used to evaluate the Support Vector Machine-Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE) model. Through the svmRFE function, the parameters "k" was set to 3 and "halve.above" was set to 100 to obtain the importance and importance ranking of each gene. The genes corresponding to the model with the lowest error rate were selected as the SVM-RFE feature genes. Then, to improve the interpretability of the data, the screening process was continued using Boruta (v 8.0.0)33. By iteratively removing genes with low correlation, the Boruta feature genes were identified’ Ultimately, the location of the feature genes obtained from the three machine learning algorithms were selected as a candidate biomarkers.

Assessment of the ability of biomarkers to predict OA

The Wilcoxon rank sum test was executed to investigate the expression of candidate biomarkers in GSE55457 and GSE55235 datasets, and genes that were substantially distinct expressed between groups in both datasets and indicated consistent expression trends were chosen as biomarkers. Moreover, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated in two datasets via pROC (v 1.18.0)34, and the area under the curve (AUC) values were determined to assess the diagnostic ability of biomarkers in two datasets (AUC > 0.7). At the same time, the GSE12021 dataset was used to conduct expression verification of the biomarkers, and the AUC values were also calculated. To validate the expression of the biomarkers in different types of tissues, the expression levels of the biomarkers were verified using the osteoarthritis (OA) cartilage dataset (GSE51588) and the OA meniscus dataset (GSE98918). Furthermore, with rms program (v 6.3-0)35, a nomogram model was created with respect to the expression data of biomarkers in GSE55457 to evaluate its capability to predict the occurrence of OA. Ultimately, the nomogram’s predictive efficacy was validated using calibration and ROC curves.

Function and gene localization of biomarkers

To further understand the regulatory interactions between biomarkers and presumably other genes, a gene–gene interaction (GGI) network was created with the gene multivariate integrated network inference algorithm (GeneMINIA) database (http://genemania.org/). Thereafter, with KEGG as background gene set, clusterProfiler and org.Hs.eg.db package (v 3.15.0)36 were employed to conduct a single-gene Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of the biomarkers to investigate their potential involvement in functional pathways (|NES|> 1, NOMP < 0.05, q < 0.25). Next, chromosomal localization was executed via RCircos (v 1.2.2)37 to check the biomarker gene localization. Simultaneously, the biomarkers were further assessed for subcellular localization using the RNALOCATE database (http://www.rna-society.org/rnalocate/). In order to investigate the functional similarities between the biomarkers, GOSemSim (v 2.28.0)38 was implemented for investigation.

Analysis of immune infiltration and molecular regulation

To explore the immune cells that may be involved in the development of OA, we performed immune infiltration analysis using Cell-type Identification By Estimating Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT)39 in GSE54557 dataset and compared the differences between OA and controls (P < 0.05). Moreover, the Spearman correlation between distinct immune cells and biomarkers was evaluated via ggcorrplot (v 0.92)40. Employing public databases, we also investigated the biomarkers’ molecular regulatory processes. First, biomarker-miRNAs were predicted through the miRDB (Score > = 60) (http://mirdb.org), miRWalk (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de), and miRstarBase databases (http://miRTarBase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/), with the intersecting miRNAs serving as the target miRNAs. The competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) network was subsequently built after lncRNAs were predicted in accordance with the target miRNAs in the starbase database (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn) (clipExpNum > 10).

Drug prediction and molecular docking

Medications that target all biomarkers at the same time were recognized as target medications by the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD; http://ctdbase.org/), resulting in a biomarker-drug network. Then,to explore potential therapeutic strategies, we extracted the tertiary structures of the biomarkers from Protein Data Bank database (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/), as well as the secondary structures of target medications from pubchem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and turned them into 3D structures with the Chem3D 14.0.0.17 https://software.stanford.edu/software/chem3d-ultra. At last, molecular docking and visualization (selection of structures with reduced binding free energy and hydrogen bonding (highest binding affinity)) were carried out with the applications Autodock and Pymol, respectively.

The quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

First, we extracted total RNA from the synovial tissues of 5 OA patients and 5 control samples (The detailed information of the patients can be found in Table S2) from Nanning First People’s Hospital. During this process, the tissues were lysed using Trizol reagent (Ambion, USA). Chloroform was added to separate the liquid into layers, and then the mixture was centrifuged at 12000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. It could be seen that the liquid was divided into three layers, and the RNA remained in the colorless upper aqueous phase. The upper aqueous phase was carefully aspirated into another EP tube. Then, an equal volume of ice-cold isopropanol was added, and the tube was inverted and allowed to stand for 10 min. After that, it was centrifuged at 12000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and a white RNA precipitate could be observed in the tube. Then, measured the RNA level with a NanoPhotometer N50. The isolated RNA was converted to cDNA using reverse transcriptase (SureScript-First-strand-cDNA-synthesis-kit, servicebio). And biomarkers and internal reference genes were measured using SYBR Green and the CFX Connect real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR equipment. Additionally, GAPDH standardized biomarker expression, and the 2-ΔΔCt technique was implemented to quantify relative gene expression. The primer sequences are presented in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

The R program (v 4.2.2) was employed for all bioinformatics analyses. The Wilcoxon-rank sum test was implemented to compare data from different cohorts. Differences were judged noteworthy at P < 0.05 level.

Results

In OA, 21 DEGs linked to the metabolism of cholesterol were gained

Applying differential expression analysis in GSE55457 dataset, a total of 2246 DEGs emerged (833 elevated and 1413 reduced DEGs) (Fig. 1a and b, Table S3). Using the overlap between DEGs and CMRGs, we located 21 candidate genes (Fig. 1c, Table S4). Besides, functional enrichment of the candidate genes revealed that they were primarily associated with plasma lipoprotein particle, amide binding, and cholesterol metabolic process functions, as well as cholesterol metabolism, alcoholic liver disease, and the AMPK signaling pathway, which were consistent with our predictions (Fig. 1d and e, Tables S5 and S6). A subsequent PPI network suggested interactions between the proteins encoded by 17 out of 21 candidate genes, including FASN-PRKAA1 and ATF3-CTNNB1 (Fig. 1f).

Screening and functional analysis of candidate genes (a) Volcanic diagram of DEGs expression between disease group and control group. Green represented up-regulated differential genes, orange represented down-regulated differential genes (b) Heat map of DEGs expression between the disease group and the control group. Green indicated high expression, and orange indicated low expression. (c) Venn diagram of candidate gene set obtained by intersection of DEGs and CMRGs (d) GO enrichment map of candidate gene, The larger the bubble was, the greater the number of genes enriched in this pathway was. (e) KEGG enrichment map of candidate gene. The colored bands in the circles corresponded to the pathway colors in the legend below the figure. (f) The PPI network analysis of the candidate genes. The higher the degree of interaction was, the yellower the color of the nodes was.

ATF3, CLU, and FASN determined to be biomarkers associated with cholesterol metabolism in OA

To discover more precise biomarkers, three machine learning algorithms were run simultaneously on 17 candidate genes with interactions. Initial, when Lambda was equal to 0.02, the LASSO procedure detected 6 feature genes (ATF3, CHKA, CLU, CTNNB1, FASN, and MVD) (Fig. 2a and b). Meanwhile, the SVM-RFE model error rate was 0.0933, which corresponds to 13 feature genes (Fig. 2c Table S7). In addition, 10 feature genes were produced with the Boruta technique (Fig. 2d). As a result, we chose the feature genes that were simultaneously tested by three machine learning algorithms, namely ATF3, CHKA, CLU, CTNNB1, and FASN, as candidate biomarkers (Fig. 2e). Further expression evaluation of the candidate biomarkers in GSE55457 and GSE55235 datasets revealed that only ATF3, CLU, and FASN matched the criteria for intergroup differences and trend consistency in both datasets, so we classified them as biomarkers (Fig. 2f and g). In addition, the GSE12021 dataset was further utilized to verify the expression of key genes, The results showed that the biomarkers ATF3, CLU, and FASN exhibited expression trends consistent with those in the previous two datasets within this dataset (Fig. 2h). Based on this, the expression of the biomarkers in different tissue types was validated using the cartilage dataset (GSE51588) and the OA meniscus dataset (GSE98918). The results showed that the expression trends of the biomarkers were consistent with those in the training set, but the differences were not significant. This indicated to some extent that the expression of these genes was tissue-specific. (Fig. 2i and j) The qRT-PCR results were consistent with the dataset results, which all demonstrated that CLU was enhanced while ATF3 and FASN expression were decreased in OA (Fig. 2k–m).

Machine learning screening of key genes. (a, b) LASSO regression analysis screened key genes. (c) SVM-RFE analysis screened key genes. (d) Boruta algorithm screened key genes (green color represented the important feature genes). (e) Wayne’s plots of key genes were obtained by taking the intersection of the three machine learning algorithms. (f) Expression of 5 key genes was validated in the training set. (g) Expression assessment validation plots of 5 key genes were obtained in external validation set GSE55235 dataset. (h) Expression assessment validation plots of 5 key genes were obtained in external validation set GSE12021 dataset. (i) Expression of key genes in the cartilage dataset (GSE51588). (j) Expression of key genes in OA Meniscus dataset (GSE98918) (k–m) Expression levels of key genes in OA were assessed using qRT-PCR. (k) ATF3 (l) CLU (m) FASN.

ATF3, CLU, and FASN had strong predictive efficacy for OA

To evaluate the diagnostic effectiveness of biomarkers for OA, ROC curves were produced individually. The outcomes displayed that the AUC values of three biomarkers under the ROC curves in GSE55457 and GSE55235 datasets were all more than 0.7, indicating that ATF3, CLU, and FASN might accurately diagnose OA (Fig. 3a and b). The AUC values of these three biomarkers were found to range from 0.629 to 0.971 by ROC analysis in GSE12021, suggesting that these biomarkers have a strong potential for predicting disease (Fig. 3c) Furthermore, a nomogram was created on the basis of biomarkers’ expression (Fig. 3d), and both the calibration curve (slope near to 1) and the ROC curve (AUC = 1) demonstrated that this nomogram was highly predictive of OA (Fig. 3e and f). Interestingly, the circle plot demonstrated that all three biomarkers were placed on autosomes, with ATF3 on chromosome 1, CLU on chromosome 8, and FASN on chromosome 17 (Fig. 3g). The biomarkers’ subcellular localization revealed that ATF3 was specifically localized to the cytoplasm, FASN to the membrane, and CLU to the cytosol, ribosome, insoluble cytoplasm nucleus, and exosomes (Fig. 3h). Lastly, we discovered that CLU and ATF3 shared more functional similarities than FASN, indicating a potential synergistic effect (Fig. 3i).

Validation of key gene evaluation, localization analysis and construction of related models (a) The validation plot of ROC curves for the key genes in the training set GSE55457 was obtained. (b) The validation plot of ROC curves for the key genes in the validation set GSE55235 was obtained. (c) The validation plot of ROC curves for the key genes in the validation set GSE12021 was obtained. (d) ATF3, CLU and FASN nomogram (e) Correction curve of nomogram (f) ROC graph of nomogram (g) Chromosome mapping of ATF3, CLU and FASN (h) Subcellular mapping of ATF3, CLU and FASN (i) Functional similarity analysis diagram of ATF3, CLU and FASN.

Mast cells might have a regulatory role in OA

A GGI network was established to better understand how biomarkers interacted with other genes. The findings indicated the top 20 genes most likely to be connected with three biomarkers (including DDIT3 and AASDHPPT), which were mostly involved in functions like co-expression and integrated stress response signaling (Fig. 4a). Meanwhile, GSEA demonstrated that FASN and ATF3 were enriched to consistent top five pathways, such as oxidative phosphorylation and parkinsons disease, yet CLU was more closely associated to leishmania infection and systemic lupus erythematosus (Fig. 4b–d). Subsequently, immunological infiltration revealed mast cell activation, resting mast cell, and memory resting CD4 T cell were differed significantly between OA and control (Fig. 4e and f). Meanwhile, the connection of biomarkers and differential immune cells proved that memory resting CD4 T cell was positively connected with ATF3 (r = 0.6) and FASN (r = 0.7), while activated mast cells had a strong association with ATF3 (r = 0.85) (Fig. 4g).

Functional and immune-related analyses of key genes (a) GGI network was constructed for key genes. (b–d) GSEA enrichment analysis was conducted for key genes. (b) AFF3 (c) CLU (d) FASN (f) Box diagram of infiltration difference between 22 kinds of immune cells (g) Correlation thermogram of ATF3, CLU and FASN with differential immune cells.

Gentamicins might be beneficial therapeutic medicines addressing three biomarkers

To explore the molecular regulatory mechanisms that three biomarkers might have, we constructed a ceRNA network. The outcomes indicated that ATF3 had one intersecting miRNA in three databases (Fig. 5a), CLU had 19 (three databases had no intersections, so miRDB and miRWalk were considered) (Fig. 5b), and FASN had seven (Fig. 5c). After deleting duplicates, the intersecting miRNAs predicted by the three biomarkers were merged to yield 10 target miRNAs. Focusing on the 10 target miRNAs, 22 lncRNAs were forecasted in the starbase database (clipExpNum > 10, after removing duplicates). The ceRNA network encompassing the 3 biomarkers, 10 miRNAs, and 22 lncRNAs was then created, including FASN-hsa-miR-15a-5p-XIST and CLU-hsa-miR-6866-3p-MALAT1, among others (Fig. 5d). Ultimately, 96 drugs targeting three biomarkers simultaneously were predicted through CTD. The study selected the drug D005839 (Gentamicins) with the highest Reference Count and conducted molecular docking with key genes (Table S8). Among them, ATF3-gentamicin (binding energy = − 2.89 kcal/mol), CLU-gentamicin (binding energy = − 3.64 kcal/mol), and FASN-gentamicin (binding energy = − 6.45 kcal/mol) demonstrated stronger binding affinities (Fig. 5e–i).

Construction and molecular docking validation of key gene-associated network graphs. (a–c) Venn diagram of different databases predicted miRNAs for key genes (a) ATF3 (b) CLU (c) FASN (d) CeRNA network construction diagram (Red represents key genes; blue stands for miRNA; orange stands for lncRNA) (e) ATF3, CLU and FASN drugs predict wayne diagram (f) Key gene-drug network construction map (Red represents key genes; blue represents the predicted drug) (g) Docking results of ATF3 and gentamicins molecules (h) Docking results of CLU and gentamicins molecules (i) Docking results of FASN and gentamicins molecules.

Discussion

OA is a prevalent degenerative joint disease characterized by the degeneration of articular cartilage and bones. Synovial inflammation also plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of OA. Synovial inflammation not only causes joint pain and swelling but also directly damages the cartilage tissue by releasing inflammatory mediators (such as TNF-α and IL-1β) and proteases (such as matrix metalloproteinases, MMPs). These inflammatory mediators and proteases can decompose the components of the cartilage matrix, accelerate cartilage degeneration, and thus promote the progression of OA41. Cholesterol is an essential substance in the human body. Genes involved in cholesterol metabolism are known as cholesterol CMRGs. Studies have shown that osteoarthritis may be associated with obesity42, which implies a potential link between cholesterol metabolism and osteoarthritis. In addition, recent studies have indicated that cholesterol metabolism is closely related to the inflammatory response43, and synovial tissue plays a key role in the inflammatory process of OA41. However, the underlying mechanisms of the complex interactions between cholesterol metabolism and osteoarthritis have not been fully elucidated44. In this study, we employed a machine learning algorithm to further refine the list of candidate genes and subsequently evaluated and validated these key genes, including performing correlation analysis between the genes in the disease and normal group. Additionally, we constructed an interaction network of key genes and adopted three machine learning algorithms for feature gene intersection. Finally, drug prediction was performed on key genes and the prediction was performed in the CTD database. This study aims to identify the biomarkers related to cholesterol metabolism and their potential molecular mechanisms in OA.

In this study, we first identified 21 cholesterol metabolism genes associatedto OA through differential expression analysis. We then analyzed the pathways and functions of candidate gene co-enrichment using gene ontology (GO) and kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) databases. GO enrichment analysis revealed that these genes were enriched in cholesterol metabolic process, sterol metabolic process, cholesterol biosynthetic process, plasma lipoprotein particle, lipoprotein particle receptor binding, and Tau protein binding. The KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the gene was significantly enriched in such pathways as cholesterol metabolism, alcoholic liver disease, fatty acid biosynthesis, terpenoid backbone biosynthesis and AMPK Signaling Pathway. Cohort studies of knee OA have shown that hyperlipidemia is associated with joint pain and an increased prevalence of OA45. One study found that OA patients with elevated cholesterol had higher pain levels than controls46. Furthermore, Kellgrenelal et al. were the first to report that serum cholesterol levels in women are connected with the risk of hand arthritis47. Furthermore, a research of 1,003 middle-aged women revealed that raised serum total cholesterol (TC) was associated with an increased risk of unilateral and bilateral knee osteoarthritis44,48. Moreover, both TC and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels have proven to be positively linked with the development of OA44. Consistent with our research result, we therefore speculated that 21 differentially expressed genes related to cholesterol metabolism related to OA were positively correlated with the occurrence of OA.

Early diagnosis of OA is crucial for effective treatment, as it allows for the opening of a "treatment window" for early intervention, potentially altering the progression of the disease in a positive way49. Currently, the diagnosis of OA is based on imaging changes, and there is a lack of research on the diagnosis of biological markers of OA. Molecular markers can indicate biological changes and play an important role in the early detection of OA50. We constructed a protein–protein interaction (PPI) for 21 candidate genes and found that 17 genes had interaction relationship. Then the 17 candidate genes with interaction were further screened and evaluated by machine learning algorithm. Then we assessed and verified the diagnostic efficacy of key genes by using the expression level of external verification set and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The results showed that the expression trends of ATF3, CLU and FASN in the two data sets were consistent, and the differences between groups had statistical significance. Besides, the area under the curve (AUC) values of ROC were greater than 0.7, indicating that the diagnostic efficacy of the three genes was good. Our study confirmed the high accuracy and stability of ATF3, CLU and FASN in the diagnosis of OA through PPI analysis, machine learning, expression of external verification set and ROC curve. The expression levels of the biomarkers were also evaluated using quantitative reverse transcription Polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The qRT-PCR results were consistent with the results of the dataset all showed that CLU was elevated while ATF3 and FASN expression was decreased in OA.

Activated transcription factor (ATF) 3 is a member of the ATF/ cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein transcription factor family. In the promoter region of inflammation-related factors, leucine zipper structure is adopted to bind other transcription factors through homodimer or heterodimer, thus serving as an important inflammatory inhibitor51. Furthermore, ATF3 is involved in many pathological processes, including gastric cancer52, atherosclerosis53, acute kidney injury54, diabetes55, and so on. According to research, ATF3 regulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines in chondrocytes and plays a role in the development of OA56. Generally inflammatory cytokines /NF-kB/ATF3 with feedforward loops in chondrocytes are considered to be new targets for OA treatment57. In conclusion, we believe that the NF-κB signaling pathway plays an important role in the inflammatory response of OA. ATF3 inhibits the expression of inflammatory factors through its interaction with the NF-κB signaling pathway58. The low expression of ATF3 may lead to the overexpression of inflammatory factors, thereby exacerbating joint inflammation. In our current study, we found that ATF3 demonstrated good diagnostic efficacy for OA, and provided effective data support for the treatment of OA.

Clusterin (CLU; Also known as apolipoprotein J), is an ATP-independent maintenance enzyme chaperone that prevents protein toxicity due to protein aggregation. It is an approximately 60 kDa disulfide-linked heterodimer protein involved in cell debris removal and apoptosis regulation. Synovial membrane and whole-body CLU have great potential as biomarkers of OA. Recent studies have highlighted CLU’s potential to as a clinically important biochemical marker59 associated with carcinogenesis and neoplasia60, neurodegeneration61, obesity and inflammation62. Recent research has underscored its important role in inflammatory arthritis. The overexpression of CLU can be detected in the synovial membrane and synovial fluid of OA patients. In terms of inflammation, previous studies have shown that CLU can enhance the inflammatory response63. Other studies have indicated that CLU is associated with the mediation of inflammatory oxidative stress64. Through PPI analysis, machine learning, expression analysis in an external validation set, and ROC curve analysis, it was found that CLU is highly expressed in osteoarthritis compared with the control group. This is consistent with existing research findings. We speculate that in osteoarthritis, CLU may stimulate the activation of inflammatory factors through the oxidative stress response and potentially contribute to the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis is a prevalent age-related disease characterized by dysregulation of extracellular matrix metabolism, lipid metabolism, and up-regulation of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Fatty acid synthase (FASN) is a major lipogenic regulatory factor in the de novo lipogenesis (DNL) process65 and is considered to be a promising therapeutic target66 for various diseases. Activation of FASN is a major metabolic event in tumor cells67,68,69. FASN interacts with CircRREB1 to mediate chondrocyte senescence and osteoarthritis progression. It has been reported that the Circling 1-FasN axis inhibits FGF18 and FGFR3-mediated PI3K-AKT signal transduction, and then increases P21 expression. The Circling 1-FasN axis is a key regulator in the pathogenesis of age-related OA, and it achieves40 based on these studies, we infer that the low expression of FASN may lead to lipid metabolism disorders. Such metabolic disorders may exacerbate the degeneration of chondrocytes, thereby promoting the development of OA. In addition, in OA, the low expression of FASN may also lead to the premature senescence of chondrocytes, thus intensifying cartilage degeneration. Of course, the specific functional mechanisms still require further research. At present, the relationship between FASN and the occurrence of osteoarthritis has not been fully studied. However, our research report provides an important source of data for the role of FASN in the occurrence and development of osteoarthritis.

Subsequently, through GSEA enrichment analysis, we found that the first five pathways for significant enrichment of FASN and ATF3 were consistent, namely, OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION, KEGG_PARKINSONS_DISEASE, KEGG_HUNTINGTONS_DISEASE, KEGG_ALZHEIMERS_DISEASE and KEGG_LYSOSOME. From these results, it can be speculated that FASN and ATF3 have similar regulatory effects in OA, and they may play important roles in the immune response involved in OA, and there is a positive correlation. Therefore, we continued to analyze the relationship between key genes and immunity, and the results showed that the correlation trends of the three key genes with differential immune cells were approximately the same, showing a positive correlation. Among them, the correlation between the key gene ATF3 and activated Mast cells in differential immune cells was as high as 0.85. Memory resting T cells CD4 differential immunocytes had a 0.6 correlation with ATF3 and a 0.7 correlation with FASN.

These results indicate that treatments targeting ATF3 may effectively alleviate the symptoms of patients with OA by inhibiting the activity of mast cells and reducing the release of inflammatory mediators. In addition, regulating the expression levels of FASN and CLU may affect the activity of CD4 + T cells, thereby reducing the inflammatory response in OA. For example, in this study, it was found that the expressions of ATF3 and FASN were decreased in the disease group. Combined with immunology-related research findings, we believe that the reason for this result is that ATF3 can regulate the activation of mast cells. When the expression of ATF3 is decreased, it may lead to the activation of mast cells towards a pro-inflammatory type, thus exacerbating the inflammatory response within the joint. The expression of FASN in immune cells is also related to the proliferation and function of immune cells. A decrease in its expression may affect the normal immune response of immune cells such as CD4 + T cells, and further influence the progression of the disease course of OA. Although these are still in the speculative stage, in the future, targeted therapies for key genes are expected to provide new theoretical support for the design of personalized immunotherapy regimens for osteoarthritis by regulating the functions of immune cells.

In addition, Loucks et al. have conducted research indicating that mast cells may have an impact on osteoarthritis70. In contrast to their focus, which may have been more on the regulatory mechanisms of mast cells themselves in osteoarthritis, our study, while exploring the relationships between ATF3, CLU, FASN and osteoarthritis, has found that they are associated with mast cells. This provides a new perspective for understanding the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. This research approach that combines osteoarthritis, cholesterol metabolism, and the regulatory role of mast cells is an important complement to existing studies. It helps to reveal the previously overlooked mechanisms of metabolic-immune interactions in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis, enriches the understanding of the mechanisms of mast cells in osteoarthritis, and expands the depth and breadth of the research. With significant advances in drug delivery technologies, molecular targeted therapy appears to be a potential early intervention therapy for OA71. Studies have demonstrated that a single dose of gentamicin was used as a standard antibiotic to prevent infection around the joint prosthesis before knee replacement. Although the difference rate did not reach statistical significance, the infection rate in the gentamicin cohort decreased by one-third, which indirectly indicated the therapeutic prospect of gentamicin osteoarthritis72. In this study, it was determined that FASN and ATF3 had similar effects in the immune response to OA and had a large relationship with the occurrence of OA. Therefore, for the key genes in this study, we conducted drug prediction, screened out drugs that could jointly regulate the expression of the three key genes, and constructed the interaction network between drug genes to reveal the interaction relationship between drugs and proteins, and found that Gentamicins had a large interaction relationship with ATF3, CLU, and FASN. Gentamicin is a bactericidal antibiotic effective against a broad spectrum of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria at low concentrations. Studies have shown that73 gentamicin and other aminoglycoside antibiotics can regulate the inflammatory response, and gentamicin has also been clinically verified to a certain extent in the treatment of some inflammatory diseases74. Combining with the results of molecular docking, we speculate that gentamicin binds to key genes to regulate the inflammatory response, which may have an impact on the development of osteoarthritis (OA). The specific effects still need to be further verified. In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that these genes can be used as immune targets, and Gentamicins has a certain therapeutic effect on these targets, providing a new possible way for the clinical drug treatment of OA.

Currently, the research on biomarkers of OA mainly focuses on aspects such as cartilage degradation products75 and inflammatory factors76. However, in the research related to cholesterol metabolism in OA, there is a lack of a comprehensive revelation of the overall disease mechanism. For example, some studies have found that cholesterol metabolism is related to the occurrence and development of OA, but its potential biomarkers have not been clearly identified16. In this study, by integrating transcriptomic data and CMRGs, biomarkers closely related to OA (such as ATF3, CLU, and FASN) were screened out. These biomarkers are not only closely related to cholesterol metabolism but also involve multiple pathological processes such as inflammatory responses and immune regulation, providing a new perspective for a comprehensive understanding of the pathogenesis of OA. Through this study, it was found that in patients with OA, the expression of CLU increased, while the expression of ATF3 and FASN decreased. We believe that the differential expression of these genes is related to the process of inflammatory immune response, which intensifies the inflammatory response of joints and makes it easier for the corresponding population to obtain OA. If it is used in clinic, by detecting the expression levels of ATF3, CLU, and FASN, it is expected to identify high-risk individuals before the onset of symptoms, thus enabling early intervention. Currently, traditional X-rays and MRIs are mainly used to detect changes in joint structures. However, these changes are usually only obvious in the late stages of OA, making early diagnosis difficult. The detection of biomarkers has, to a certain extent, solved this problem and delayed the progression of the disease. There may be individual differences in the pathogenesis and pathological processes of OA among different patients. Detecting the expression levels of these biomarkers can help classify patients into different subgroups, thereby providing a basis for the formulation of personalized treatment plans. For example, patients with high expression of CLU may be closely related to the inflammatory response. For such patients, treatment strategies aimed at suppressing the inflammatory response can be preferentially considered. During the treatment process, regularly monitoring the expression levels of these biomarkers helps to evaluate the treatment effect in real time, adjust the treatment plan in a timely manner, and thus improve the precision and effectiveness of treatment. In this study, through the analysis of multiple datasets, the expression patterns of ATF3, CLU, and FASN in the synovial membrane, cartilage, and meniscus tissues of osteoarthritis (OA) were explored. Although no statistically significant differences in expression were observed in the cartilage and meniscus, the expression trends of these genes were consistent with the results in the synovial membrane tissue. This suggests that ATF3, CLU, and FASN may play similar roles in the pathological process of OA, but their expression changes in the synovial membrane tissue are more significant, which may be closely related to the crucial role of synovial inflammation in the pathogenesis of OA. Therefore, ATF3, CLU, and FASN may be more suitable as synovial membrane tissue-specific biomarkers for the early diagnosis of OA and the assessment of inflammatory activity. However, future studies should further explore the specific functions and regulatory mechanisms of these genes in different tissues to verify their clinical application value as biomarkers.

However, there are still some limitations in this study. Firstly, although the RT-qPCR experiments have supported our bioinformatics results to a certain extent, there is a certain difference between mRNA and protein expression. Our study lacks verification at the protein level. In the future, we will consider using mouse experiments or clinical samples to verify the expression of the above-mentioned genes at the protein level through Western blot or immunohistochemistry experiments, so as to provide more support for the bioinformatics results and open up a new direction for the prevention and treatment of osteoarthritis. In addition, during the process of RT-qPCR verification, we only used one housekeeping gene, which may lead to certain bias. In the future, we will use 3 to 5 different housekeeping genes for verification to increase the reliability of the results. Overall, although the current study provides preliminary insights into the potential biomarkers of osteoarthritis, further experimental verification and optimization are still needed to lay a more solid foundation for clinical application.

Data availability

Two OA-related datasets (GSE55457 and GSE55235) from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds).

References

Hunter, D. J. & Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 393(10182), 1745–1759 (2019).

Lespasio, M. J. et al. Knee osteoarthritis: A primer. Perm. J. 21, 16–183. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-183 (2017).

Katz, J. N., Arant, K. R. & Loeser, R. F. Diagnosis and treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis: A review. JAMA 325, 568–578. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.22171 (2021).

Favero, M. et al. Infrapatellar fat pad features in osteoarthritis: A histopathological and molecular study. Rheumatology 56, 1784–1793. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex287 (2017).

Abramson, S. B., Attur, M. & Yazici, Y. Prospects for disease modification in osteoarthritis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2, 304–312. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncprheum0193 (2006).

Poole, A. R. Osteoarthritis as a whole joint disease. HSS J. 8, 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11420-011-9248-6 (2012).

Tang, X. et al. The prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in China: Results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68, 648–653. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.39465 (2016).

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386, 743–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 (2015).

Tschon, M., Contartese, D., Pagani, S., Borsari, V. & Fini, M. Gender and sex are key determinants in osteoarthritis not only confounding variables. A systematic review of clinical data. J. Clin. Med. 10, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10143178 (2021).

Jordan, J. M. et al. Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: The Johnston county osteoarthritis project. J. Rheumatol. 34, 172–180 (2007).

Glyn-Jones, S. et al. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 386, 376–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60802-3 (2015).

Choi, W. S. et al. The CH25H-CYP7B1-RORα axis of cholesterol metabolism regulates osteoarthritis. Nature 566, 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0920-1 (2019).

Warmink, K. et al. High-fat feeding primes the mouse knee joint to develop osteoarthritis and pathologic infrapatellar fat pad changes after surgically induced injury. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 28, 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.03.008 (2020).

Dahaghin, S., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M., Koes, B. W., Hazes, J. M. & Pols, H. A. Do metabolic factors add to the effect of overweight on hand osteoarthritis? The Rotterdam study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 66, 916–920. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2005.045724 (2007).

Schwager, J. L. et al. Association of serum low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, and total cholesterol with development of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 74, 274–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24455 (2022).

Farnaghi, S., Crawford, R., Xiao, Y. & Prasadam, I. Cholesterol metabolism in pathogenesis of osteoarthritis disease. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.13061 (2017).

Braaten, J. A. et al. Biomarkers for osteoarthritis diseases. Life https://doi.org/10.3390/life12111799 (2022).

Binvignat, M. et al. Use of machine learning in osteoarthritis research: A systematic literature review. RMD Open https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001998 (2022).

Jiasheng, W. A L1 regularized logistic regression model for highdimensional questionnaire data analysis. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2078/1/01205 (2021).

Ullah, M. et al. PScL-HDeep: Image-based prediction of protein subcellular location in human tissue using ensemble learning of handcrafted and deep learned features with two-layer feature selection. Brief. Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab278 (2021).

Hyunji, S. et al. Predictive model for abdominal liposuction volume in patients with obesity using machine learning in a longitudinal multi-center study in Korea. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 29791. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79654-y (2024).

Mathema, V. B., Sen, P., Lamichhane, S., Orešič, M. & Khoomrung, S. Deep learning facilitates multi-data type analysis and predictive biomarker discovery in cancer precision medicine. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 21, 1372–1382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2023.01.043 (2023).

Zhao, N. et al. Identification of a cholesterol metabolism-related prognostic signature for multiple myeloma. Sci. Rep. 13, 19395. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46426-z (2023).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv007 (2015).

Gustavsson, E. K., Zhang, D., Reynolds, R. H., Garcia-Ruiz, S. & Ryten, M. ggtranscript: An R package for the visualization and interpretation of transcript isoforms using ggplot2. Bioinformatics 38, 3844–3846. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac409 (2022).

Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw313 (2016).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (1999).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2022).

Zhou, R. S. et al. Integrated analysis of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA network in squamous cell carcinoma of tongue. BMC Cancer 19, 779. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5983-8 (2019).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1–22 (2010).

Sanz, H., Valim, C., Vegas, E., Oller, J. M. & Reverter, F. SVM-RFE: Selection and visualization of the most relevant features through non-linear kernels. BMC Bioinform. 19, 432. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-018-2451-4 (2018).

Maurya, N. S., Kushwah, S., Kushwaha, S., Chawade, A. & Mani, A. Prognostic model development for classification of colorectal adenocarcinoma by using machine learning model based on feature selection technique boruta. Sci. Rep. 13, 6413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33327-4 (2023).

Robin, X. et al. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 (2011).

Liu, T. T. et al. Identification of CDK2-related immune forecast model and ceRNA in lung adenocarcinoma, a pan-cancer analysis. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 682002. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.682002 (2021).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Zhang, H., Meltzer, P. & Davis, S. RCircos: An R package for Circos 2D track plots. BMC Bioinform. 14, 244. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-244 (2013).

Yu, G. Gene ontology semantic similarity analysis using GOSemSim. Methods Mol. Biol. 2117, 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0301-7_11 (2020).

Chen, B., Khodadoust, M. S., Liu, C. L., Newman, A. M. & Alizadeh, A. A. Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol. Biol. 1711, 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7493-1_12 (2018).

Lu, Y., Tan, L., Xie, J., Cheng, L. & Wang, X. Distinct microglia alternative splicing in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 14, 6554–6566. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204223 (2022).

Sanchez-Lopez, E., Coras, R., Torres, A., Lane, N. E. & Guma, M. Synovial inflammation in osteoarthritis progression. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-022-00749-9 (2022).

Kulkarni, K., Karssiens, T., Kumar, V. & Pandit, H. Obesity and osteoarthritis. Maturitas 89, 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.04.006 (2016).

Bauer, R., Brüne, B. & Schmid, T. Cholesterol metabolism in the regulation of inflammatory responses. Front. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1121819 (2023).

Cao, C. et al. Cholesterol-induced LRP3 downregulation promotes cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis by targeting Syndecan-4. Nat. Commun. 13, 7139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34830-4 (2022).

Zhou, M. et al. The cross-sectional and longitudinal effect of hyperlipidemia on knee osteoarthritis: Results from the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort in China. Sci. Rep. 7, 9739. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10158-8 (2017).

Li, H., George, D. M., Jaarsma, R. L. & Mao, X. Metabolic syndrome and components exacerbate osteoarthritis symptoms of pain, depression and reduced knee function. Ann. Transl. Med. 4, 133. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2016.03.48 (2016).

Kellgren, J. H. Osteoarthrosis in patients and populations. Br. Med. J. 2, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.5243.1 (1961).

Hart, D. J., Doyle, D. V. & Spector, T. D. Association between metabolic factors and knee osteoarthritis in women: The Chingford study. J. Rheumatol. 22, 1118–1123 (1995).

Wang, Q. et al. Diagnosis of early stage knee osteoarthritis based on early clinical course: Data from the CHECK cohort. Arthritis Res. Ther. 23, 217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-021-02598-5 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Six macrophage-associated genes in synovium constitute a novel diagnostic signature for osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol. 13, 936606. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.936606 (2022).

Hai, T., Wolfgang, C. D., Marsee, D. K., Allen, A. E. & Sivaprasad, U. ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expr. 7, 321–335 (1999).

Fu, D., Wang, C., Yu, L. & Yu, R. Induction of ferroptosis by ATF3 elevation alleviates cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer by restraining Nrf2/Keap1/xCT signaling. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 26, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-021-00271-y (2021).

Wu, X., Qiu, F., Jin, X., Zhou, J. & Zang, W. ATF3: A novel biomarker for the diagnosis of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery. Ann. Transl. Med. 9, 1655. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm-21-5231 (2021).

Huo, S. et al. ATF3/SPI1/SLC31A1 signaling promotes cuproptosis induced by advanced glycosylation end products in diabetic myocardial injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021667 (2023).

Iezaki, T. et al. ATF3 deficiency in chondrocytes alleviates osteoarthritis development. J. Pathol. 239, 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4739 (2016).

Lou, Y., Song, F., Kang, Y. & Xu, Y. Periodic mechanical stress inhibits the development of osteoarthritis via regulating ATF3-Akt axis. J. Inflamm. Res. 16, 5613–5628. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S419186 (2023).

Chen, X., Halberg, R. B., Ehrhardt, W. M., Torrealba, J. & Dove, W. F. Clusterin as a biomarker in murine and human intestinal neoplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9530–9535. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1233633100 (2003).

Wei, W., Ken-Ichi, N., Takao, H. & Makoto, I. Anti-inflammatory effects of naturally occurring retinoid X receptor agonists isolated from Sophora tonkinensis Gagnep. via retinoid X receptor/liver X receptor heterodimers. J. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11418-018-01277-1 (2019).

Santilli, G., Aronow, B. J. & Sala, A. Essential requirement of apolipoprotein J (clusterin) signaling for IkappaB expression and regulation of NF-kappaB activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38214–38219. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C300252200 (2003).

Desikan, R. S. et al. The role of clusterin in amyloid-β-associated neurodegeneration. JAMA Neurol. 71, 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4560 (2014).

Won, J. C. et al. Plasma clusterin (ApoJ) levels are associated with adiposity and systemic inflammation. PLoS ONE 9, e103351. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103351 (2014).

Kalvaityte, U. et al. Exploring the translational potential of clusterin as a biomarker of early osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Transl. 32, 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2021.10.001 (2022).

Zhenqing, L. et al. Astrocytic response mediated by the CLU risk allele inhibits OPC proliferation and myelination in a human iPSC model. Cell Rep 42(8), 112841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112841 (2023).

Gil-Soon, C. et al. Role of clusterin/progranulin in toluene diisocyanate-induced occupational asthma. Exp. Mol. Med. 50(5), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-018-0085-2 (2018).

Park, S., Baek, I. J., Ryu, J. H., Chun, C. H. & Jin, E. J. PPARα-ACOT12 axis is responsible for maintaining cartilage homeostasis through modulating de novo lipogenesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27738-y (2022).

Che, L. et al. Cholesterol biosynthesis supports the growth of hepatocarcinoma lesions depleted of fatty acid synthase in mice and humans. Gut 69, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317581 (2020).

Lim, S. A. et al. Lipid signalling enforces functional specialization of T(reg) cells in tumours. Nature 591, 306–311. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03235-6 (2021).

Xie, P. et al. Neddylation of PTEN regulates its nuclear import and promotes tumor development. Cell Res. 31, 291–311. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-00443-z (2021).

Gong, Z. et al. CircRREB1 mediates lipid metabolism related senescent phenotypes in chondrocytes through FASN post-translational modifications. Nat. Commun. 14, 5242. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40975-7 (2023).

Matthieu, E., Grégoire, M., Mekki, T., Henri, F., Matthieu, O. Comments on: "Lateral knee laxity increases the risk of excessive joint line obliquity after medial opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy" by BA Matache, PO Jean, S Pelet, AM Roger, J Dartus, E Belzile published in Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2023: doi.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2023.103717. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res, 110(3), 103862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2024.103862 (2024).

Steinle, H. et al. Delivery of synthetic mRNAs for tissue regeneration. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 179, 114007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.114007 (2021).

Ashkenazi, I. et al. Does addition of gentamicin for antibiotic prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty reduce the rate of periprosthetic joint infection. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 143, 5255–5260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-022-04744-3 (2023).

Olekson, M. A. et al. Ultrahigh dose gentamicin alters inflammation and angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. Wound Repair Regen. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.12557 (2017).

Lev-Tzion, R. et al. Oral vancomycin and gentamicin for treatment of very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion https://doi.org/10.1159/000475660 (2017).

Dyer, J., Davison, G., Marcora, S. M. & Mauger, A. R. Effect of a mediterranean type diet on inflammatory and cartilage degradation biomarkers in patients with osteoarthritis. J. Nutr. Health Aging https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0806-y (2017).

Warmink, K., Vinod, P., Korthagen, N. M., Weinans, H. & Rios, J. L. Macrophage-driven inflammation in metabolic osteoarthritis: Implications for biomarker and therapy development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076112 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues in the laboratory for their valuable guidance and suggestions during the whole research process, and for their help in the processing and analysis of experimental data. We sincerely thank our family and friends for their support and understanding in our academic and research process. Finally, we thank all those who have supported and helped us all the way. Without your support, this research is impossible.

Funding

This project did not receive any funds to assist in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JZ and HH designed the study. CL analyzed the datasets and interpreted the results. WW, and JC wrote and edited the manuscript. SL and XL and HQ provided software support. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The collection of human synovial samples was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (LW2024-009-01), and the collection method followed the guidelines stipulated in the Helsinki Declaration. Obtain the written informed consent of the participants.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lao, C., Wei, W., Cheng, J. et al. Screening biomarkers related to cholesterol metabolism in osteoarthritis based on transcriptomics. Sci Rep 15, 21218 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04550-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04550-y