Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is a contagious bacterial disease affecting millions of people globally and is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality, particularly in the developing world. The spread of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) tuberculosis has emerged as a major challenge to TB treatment, demanding the discovery of novel drug candidates. The process requires fast and efficient lead identification methodologies. This research content embarks on a comprehensive exploration of machine learning algorithms applied to identify potential compounds active against TB. Leveraging a comprehensive dataset encompassing 23,791 molecules from 5 targets with unique SMILES and ChEMBL IDs obtained from the ChEMBL database, a total of 103 classification models were developed based on six different types of molecular representations, namely RDKit descriptors (RDKitDes), MACCS fingerprints (MACCSFP), Morgan fingerprints (MorganFP), Atom-pair fingerprints (PairsFP), PubChem fingerprints (PubChemFP), and RDKit fingerprints (RDKitFP). In this regard, seven machine learning algorithms, e.g., Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Decision Tree (DT), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), Logistic Regression (LR), and ANN, were employed to build these models using different combinations of dataset. Further, the performance of the models was assessed using a tenfold cross-validation, with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) as the evaluation metric. In addition to that, the contribution of the important descriptors in the molecule’s bioactivities was interpreted using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), basically caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), has remained a major global public health crisis for many years, affecting millions of lives each year. According to the 2024 report by WHO, in the year 2023, tuberculosis was the world’s leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, and caused almost twice as many deaths as HIV/AIDS. More than 10 million people continue to fall ill with TB every year, and the number has been rising continuously since 20211.

M. tuberculosis is the most common TB strain and the primary cause of human TB. Other members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC), comprising M. africanum, M. canettii, and M. bovis, can also cause TB2,3,4. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) gets transmitted through respiratory droplets expelled from infected people by coughing, sneezing, or spitting, affecting an individual primarily through the lungs. The disease, though asymptomatic in the initial stages, can manifest in various forms in later stages, like persistent cough lasting three weeks or longer, chest pain, coughing up blood, weakness, weight loss, fever, night sweats, etc. Pulmonary TB is the most common type to occur in humans and, if left untreated, can be fatal. Vulnerable populations, including young children and individuals with weakened immune systems, basically bear the brunt of TB’s impact5,6,7.

The approved treatments for TB take too long to cure and, therefore, are too complicated to administer. Many people have negative interactions between commonly used antiretrovirals and the drugs used for TB treatment8. TB drugs often impart adverse toxic effects on patients over their prolonged use9. Moreover, the lengthy treatment and inappropriate or ineffectual medication bring up the risk of developing more difficult-to-treat drug-resistant TB. The emergence of drug-resistant strains of the bacterium or simply the activation of drug efflux pumps significantly hinders the efforts to combat TB10,11,12. The Anti-TB drugs that were previously used or are currently administered, can divided into first-line drugs, including rifampicin (R), isoniazid (H), ethambutol (E), pyrazinamide (Z), and streptomycin, and second-line drugs, including bedaquiline (Bdq), linezolid (Lzd), moxifloxacin (Mfx), levofloxacin (Lfx), clofazimine (Cfz), cycloserine (Cs), para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS), propylthiouracil, and amikacin (Am)13,14.

The success rate of the TB drug development, either by identifying new potent molecules or by finding novel targets following different mechanisms of action, is not very encouraging15,16. Rifampicin was the last first-line anti-TB drug, which was developed almost sixty years ago17. Since then, only a few drug candidates have qualified for clinical trials, and of them, two compounds, Bedaquiline and Delamanid, despite having unfavorable side effects, have been approved for treating multidrug-resistant TB (MDRTB)18. Combination therapies using approved drugs are usually adopted over monotherapy in different treatment regimens to achieve more effective results. In 2019, pretomanid was approved by the FDA as a treatment in combination therapy for drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB)19. For example, in 2019, the commonly given 6-month regimen was developed to treat multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB, comprising three drugs, i.e., bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid20,21. Another 4-month regimen, containing rifapentine and moxifloxacin, has given comparable results to treat drug-susceptible TB at the 12-month follow-up20,21. Recently, the six-month BPaLM regimen has been approved and implemented in India as a more effective treatment option for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), which includes four components: bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, and moxifloxacin22.

Therefore, new anti-TB drugs that are equally efficacious in monotherapies, effective in shorter treatment regimens, better tolerated by most patient populations, and particularly useful against drug-resistant TB strains are urgently needed. It steers tuberculosis research toward identifying novel compounds (either by the discovery of new molecules or by repurposing the existing molecules) to develop first-in-class drug candidates to cure TB23.

In the formulation of anti-TB drugs, mainly two approaches are used for hit identification, i.e., the target-based screening against a particular essential enzyme, and the phenotype screening of wild-type or recombinant whole-Mtb cells24. Although quite successful and widely utilized, high-throughput phenotype screening (HTS) suffers from limitations of being time-consuming, expensive, and laborious. With the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), the capability of computational tools has been boosted significantly to expedite the drug discovery and treatment process using data-driven prediction models. Being capable of managing the storage, management, analysis, and modeling of potential therapeutic compounds, the computer-aided drug design (CADD) greatly assisted the search for new therapeutics against Mtb25,26,27,28. Different machine learning (ML) models are developed to detect TB in different stages as well as to predict quantitative structure–activity/property relationships (QSAR/QSPR), drug-drug interactions, drug repurposing, and pharmacogenomics in developing new anti-TB drug candidates29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36.

With the continuous accumulation of experimental data, computational QSAR-based models have been developed to predict Mtb-active molecules37,38,39. Prathipati et al. (2008) developed Bayesian classification models using 15 types of fingerprints using a dataset of 3779 compounds with 0.00316 nM to 4094 μM Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values. Based on the ECFP12 fingerprints, the best classifier was developed, and testing it on a set of 2880 compounds resulted in a prediction accuracy of 0.7340. Ekins et al. (2014) constructed classification models with a dataset of 773 compounds using naïve Bayes (NB), support vector machine (SVM), and recursive partitioning (RP) algorithms. Upon testing the mouse TB infection model, the Bayesian model accurately predicted 8 out of 11 in vivo actives41. Lane et al. (2018) developed classification models based on a comprehensive Mtb dataset of 18,886 molecules using six ML algorithms. However, the decision on the best model remains inconclusive since DL and SVM outperformed others for training and cross-validation regardless of the descriptor type. In contrast, the BNB model provided the best predictions for an external test set with 1171 molecules42. Recently, using a dataset of 8518 molecules from three CHEMBL Target IDs, Hou et al. (2021) have developed 24 classification models, including two ensemble methods based on six molecular descriptors/fingerprints using four ML algorithms. The stacking model, developed by combining the predictions from the models based on the 2D descriptors and Morgan fingerprints, performed the best18.

It is evident from the preceding literature that the previous reports lack in terms of either of the parameters e.g. the volume of the datasets of the molecules, the number of machine learning algorithms used, the number of models developed with the various combinations of molecular descriptors/fingerprints, and the robustness of the best models as evaluated18,40,41,42. The lack of any of the four parameters in the individual cases hinders the evaluation and performance of the respective best models and opens a potential research gap to dig into the topic. Compared to the previous studies, this report describes the development of robust classification models using a larger, comprehensive dataset of 23,791 molecules obtained from five ChEMBL target IDs. Using various combinations of datasets, 103 classification models were developed during the entire study. In this regard, seven machine learning algorithms, e.g., Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Decision Tree (DT), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), Logistic Regression (LR), and ANN, were employed to develop 42 classification models based on six different types of molecular representations, namely RDKit descriptors, Morgan fingerprints, PubChem fingerprints, Atom Pair fingerprints, and MACCS keys. In addition to that, another 35 classification models were developed using the seven above-mentioned algorithms based on five molecular representations obtained by combining each fingerprint with RDKit descriptors separately. Further, two ensemble techniques, e.g., voting and stacking, were also used to improve the prediction uniformity, stability, precision, and generalization. RDKit descriptors combined with Morgan fingerprints were employed to capture the structural properties and molecular features, providing a comprehensive dataset useful for the model development. Among the single models, the XGBoost classifier, trained on RDKit descriptors and Morgan fingerprints, achieved an excellent accuracy of 90% and an AUC value of 0.87, outperforming the developed models reported earlier. In ensemble models, voting and stacking techniques provided excellent results on the test dataset. In addition to that, the contribution of the important descriptors in the molecule’s bioactivities was interpreted using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method.

Materials and methods

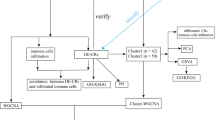

As illustrated in Fig. 1, our proposed workflow involves several key steps: data acquisition and preprocessing, feature engineering, model development and training, model evaluation, and model interpretation. A comprehensive dataset of anti-tubercular compounds was curated from the ChEMBL database, cleaned, preprocessed, and transformed into suitable representations for machine learning. Molecular descriptors and fingerprints were generated using the RDKit package to capture relevant chemical features. Various machine learning algorithms were trained on the prepared dataset, and hyperparameter tuning was performed to optimize model performance. The performance of the trained models was evaluated using rigorous metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC. The SHAP method was employed to interpret the decision-making process of the models and identify the most influential molecular features.

Data processing

A comprehensive dataset of 23,791 anti-tubercular compounds was curated from the ChEMBL database by querying five specific target IDs (CHEMBL360, 2111188, 612960, 613086, and 615052)43. The dataset was pre-processed to ensure data quality and consistency. Duplicate entries were removed, and missing values were handled appropriately. To standardize the activity measurements, Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values were converted to a common unit (µM), using the equations below (1,2).

where nM is nanoMolar, μgmL-1 is microgram per milliliter, and μM is microMolar.

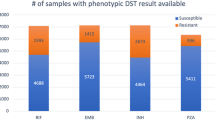

Compounds with MIC values exceeding 10 µM were classified as 'inactive,' while those with 10 µM or lower were categorized as 'active.' The final dataset, comprising SMILES strings and corresponding activity labels, was used as the foundation for subsequent machine-learning model development (Fig. 2).

Descriptor and fingerprint generation

Molecular descriptors and fingerprints are numerical representations of molecular structures that capture the essential chemical features. These representations serve as crucial inputs for machine learning models, enabling them to recognize patterns and predict the biological activity of molecules. A diverse set of descriptors and fingerprints, namely RDKit descriptors (RDKitDes), MACCS fingerprints (MACCSFP), Morgan fingerprints (MorganFP), Atom-pair fingerprints (PairsFP), PubChem fingerprints (PubChemFP), and RDKit fingerprints (RDKitFP), were generated using the RDKit package in Python and employed to capture various chemical and physical properties relevant to identifying molecules with anti-tubercular activity. After generating the descriptors and fingerprints, the original SMILES strings were removed from the dataset, leaving only the numerical representations and the corresponding activity labels. The processed datasets were subsequently used to train and evaluate machine learning models44.

Different types of datasets were constructed following the generation of fingerprints and descriptors. Five fingerprint-only datasets included Morgan, MACCS, PubChem, Atom-pair, and RDKit fingerprints, whereas the single descriptor-only dataset contains RDKit Descriptors. Five combined datasets were generated by compounding each fingerprint with RDKit Descriptors. Each dataset retained the ‘Activity’ column from the original data. These processed datasets were subsequently employed for developing machine learning (ML) models via training and testing. The ensuing sections will elaborate on model training, hyperparameter tuning, and evaluation methodologies.

Model selection

Diverse sets of machine-learning algorithms, including Random Forest, Decision Tree, K-Nearest Neighbors, Gaussian Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, ANN, and XGBoost, were employed to develop classification models45,46,47,48,49,50,51. Each algorithm was selected based on its strengths and suitability for the dataset. Hyperparameter tuning was performed to optimize the performance of the models. The XGBoost models were implemented using the XGBoost library, while the ANN models were developed using PyTorch. The remaining models were implemented using the sci-kit-learn library. By leveraging these powerful machine learning tools, we aimed to develop models to predict the anti-tubercular activity of compounds.

In brief, the Random Forest, an ensemble method, leverages multiple decision trees to improve accuracy and reduce overfitting. Decision Trees, while interpretable, can be prone to overfitting. KNN, a non-parametric algorithm, classifies data points based on their nearest neighbors. Gaussian Naive Bayes, a probabilistic classifier, assumes feature independence. Logistic Regression, a statistical model, estimates class probabilities. DLs, inspired by biological neural networks, can learn complex patterns. XGBoost, a powerful gradient-boosting algorithm, is known for its speed and accuracy. Ensemble methods such as stacking and voting were employed to enhance the predictive performance further52,53. Stacking combines the predictions of multiple base models using a meta-model, while voting aggregates the predictive analyses of various base models through a majority voting scheme.

Model evaluation metrics

In our analysis, the method of tenfold cross-validation was utilized on the training dataset for internal validation. This involved dividing the dataset into ten folds, training the model on nine folds, and evaluating its performance on the remaining fold. This process was repeated ten times, providing a robust estimate of the model’s generalization capability. The Stratified Shuffle Split method was applied for dataset splitting to maintain an approximate class distribution balance across training and validation folds. A random Search technique was employed for hyperparameter tuning. In this technique, sampling of each parameter was done from a probability distribution over the possible values. The optimization of hyperparameters was based on maximizing the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) during the tenfold cross-validation. Several binary classification metrics, including Accuracy, Sensitivity (Recall), Specificity, Precision, F1 Score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), Balanced Accuracy, False Positive Rate (FPR), and AUC-ROC, were implemented to assess the performance of the classification models.

These metrics are defined as follows in the Eqs. (3–10)54.

Here, TP, TN, FP, and FN represent True Positive, True Negative, False Positive, and False Negative, respectively.

Model interpretation

The SHAP method was employed to interpret the developed machine learning models. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is a framework based on cooperative game theory and the concept of Shapley values. SHAP provides a detailed understanding of the importance and contribution of each feature towards a particular prediction. The SHAP method considers all possible combinations of features. It assigns a value to each feature that quantifies its contribution to a specific prediction, revealing key insights about the model’s decision-making process. Thus, the method fairly distributes credit among the features, ensuring the consistency and local accuracy of the explanation54,55.

Here, the TreeExplainer explanation method of SHAP, specifically designed for tree-based models, was utilized. The TreeExplainer method allows efficient, trackable computation of local explanations and ensures that the explanations retain fidelity to the original model. The model interpretation was conducted in two key steps: a) Local Explanation: For each prediction, SHAP assigns a numerical credit to each input feature, reflecting how much that feature contributed to the specific prediction; b) Global Structure: By aggregating multiple local explanations across the dataset, a global understanding of the model’s behavior is constructed. This global explanation maintains local faithfulness to the model’s decisions56.

Results and discussions

This section presents a comprehensive analysis of the developed machine learning models. The experimental setup details the data processing techniques, feature engineering approaches, and model selection process. Hyperparameter tuning was employed to optimize model performance. A comparative analysis of various machine learning algorithms was conducted to identify the most effective models. The performance of these models was evaluated using rigorous metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC. Additionally, the SHAP method was utilized to interpret the decision-making process of the models and identify the key molecular features that contribute to their predictions.

Experiment setup

To identify potential drug candidates against tuberculosis using a machine-learning approach, a dataset of 23,791 molecules was curated from the ChEMBL database with five ChEMBL target IDs (CHEMBL360, 2,111,188, 612,960, 613,086, and 615,052). The dataset was rigorously pre-processed to ensure data quality and consistency. Data cleaning, feature engineering, and activity classification were performed to prepare the data for machine learning model development. In this regard, seven machine learning algorithms, e.g., Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Decision Tree (DT), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), Logistic Regression (LR), and ANN, were employed to develop the classification models based on six different types of molecular representations namely RDKit descriptors (RDKitDes), MACCS fingerprints (MACCSFP), Morgan fingerprints (MorganFP), Atom-pair fingerprints (PairsFP), PubChem fingerprints (PubChemFP), and RDKit fingerprints (RDKitFP). Two ensemble techniques, e.g., voting and stacking, were used to improve the prediction uniformity, stability, precision, and generalization. RDKit descriptors combined with Morgan fingerprints were employed to capture the structural properties and molecular features, providing a comprehensive dataset useful for the model development. A tenfold cross-validation strategy was adopted to evaluate model performance using a range of metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC. Hyperparameter tuning was conducted to optimize model performance.

The SHAP method was utilized to gain insights into the underlying mechanisms of model predictions. By analyzing the feature importance scores provided by SHAP, we identified the key molecular features that contribute to the model’s predictions.

Hyperparameter tuning process

To optimize model performance, rigorous hyperparameter tuning was conducted using the RandomizedSearchCV and ParameterSampler techniques to optimize model performance. This approach efficiently explores the hyperparameter space, significantly reducing computational costs compared to an exhaustive grid search. The ParameterSampler technique was used for the hyperparameter tuning in the case of DL, whereas the RandomizedSearchCV technique was used for the rest of the models.

For Random Forest, key hyperparameters such as the number of trees (n_estimators, from 50 to 200, interval = 10), maximum depth (max_depth, from 1 to 30, interval = 1), minimum samples split (min_sample_split, from 2 to 10, interval = 1), and minimum samples leaf were tuned. Similarly, for Decision Trees, maximum depth (max_depth, from 1 to 30, interval = 1), minimum samples split (min_sample_split, from 2 to 10, interval = 1), and minimum samples leaf (min_samples_leaf, from 1 to 10, interval = 1) were optimized.

In the case of KNN, the number of neighbors (n_ neighbors, from 1 to 30 interval = 1), weight function (uniform or distance), and algorithm for nearest neighbor computation (ball_tree, kd_tree, brute) were tuned whereas, for Gaussian Naïve Bayes, the variance smoothing parameter (var_smoothing, from 1e−9 to 1e−7, interval = 1e−9) was tuned. The regularization strength (C, from 0.1 to 10, interval = 0.1) and type (L1, L2, elastic net) were optimized for Logistic Regression. Hyperparameters such as the number of hidden layers (layers, from 1 to 3), neurons per layer (neurons, from 32 to 128, interval = 32), activation function (relu, tanh, sigmoid), optimizer (adam, rmsprop), learning rate (learning_rate, from 0.001 to 0.01, interval = 0.001), batch size (batch_size, from 16 to 64, interval = 16), and dropout rate were tuned for Deep Learning. For XGBoost, the number of gradient-boosted trees (n_estimators, from 50 to 300, interval = 10), maximum depth (max_depth, from 1 to 30, interval = 1), and the balance of positive and negative weights (scale_pos_weight, from 0.1 to 10, interval = 0.1), were optimized.

Performance comparison of different ML algorithms

A diverse set of machine-learning algorithms, including Random Forest, XGBoost, Decision Tree, K-Nearest Neighbors, Gaussian Naive Bayes, Logistic Regression, and ANN, were utilized in conjunction with various molecular representations (RDKit descriptors, MACCS, Morgan, Atom-pair, PubChem, and RDKit fingerprints to develop 42 predictive machine learning (ML) models. Consequently, the models were evaluated for predicting anti-tubercular activity by assessing their performance across metrics such as AUC, accuracy, F1 score, and recall. Figures 3 and 4 compare fingerprint representations and their influence on model performance across different evaluation metrics by evaluating the corresponding heatmaps (Fig. 3) and boxplots (Fig. 4).

Heatmap for fingerprint and resultant metric comparison on various models. Demonstration of Model Performance Metrics Across Fingerprint Representations—(a) ROC-AUC, (b) False Positive Rate, (c) Precision, (d) Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), (e) F1 Score, (f) Accuracy, (g) Recall, (h) Specificity, and (i) Balanced Accuracy.

Boxplot for fingerprint and resultant metric comparison on various models. Demonstration of Model Performance Metrics Across Fingerprint Representations—(a) Accuracy, (b) ROC-AUC, (c) F1 Score, (d) Recall, (e) Specificity, (f) Balanced Accuracy, (g) Precision, (h) False Positive Rate, and (i) Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC).

Figure 3a illustrates the performance of six classifiers across various molecular fingerprints, evaluated by the ROC_AUC metric. Random Forest, XGBoost, and KNN consistently demonstrate the highest ROC_AUC values (~ 0.88–0.90), establishing them as the top-performing models for this dataset. On the other hand, Gaussian Naive Bayes exhibits significantly lower performance, particularly with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints, suggesting its unsuitability for this classification task. The heatmap in Fig. 3b depicts the False Positive Rate (FPR) for each classifier and fingerprint combination. Notably, Gaussian Naive Bayes has the highest FPR, especially with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints, indicating a high rate of false positive predictions. In contrast, Random Forest, XGBoost, and KNN consistently maintain lower FPR values, making them more reliable in terms of minimizing false positive classifications. Figure 3c highlights the precision scores of the classifiers across different fingerprints. Random Forest, XGBoost, and KNN once again demonstrate strong performance, achieving higher precision values compared to other models. Gaussian Naive Bayes, however, exhibits significantly lower precision, particularly with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints, suggesting a high rate of false positive predictions.

The heatmap in Fig. 3d illustrates Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient (MCC) for each classifier and fingerprint combination. Random Forest, XGBoost, and ANN models consistently achieve higher MCC values, indicating strong predictive performance across various molecular fingerprints. On the other hand, Gaussian Naive Bayes demonstrates significantly lower MCC scores, particularly with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints, suggesting limited predictive power for this dataset. Figure 3e depicts the F1 scores of the classifiers across different fingerprints. Random Forest, XGBoost, and DL models maintain high F1 scores, indicating a good balance between precision and recall. Gaussian Naive Bayes, however, exhibits lower F1 scores, especially with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints, suggesting suboptimal performance in precision and recall. The heatmap in Fig. 3f showcases the accuracy of each classifier and fingerprint combination. Random Forest, XGBoost, and ANN consistently achieve the highest accuracy scores, demonstrating strong overall predictive performance. Gaussian Naive Bayes demonstrates significantly lower accuracy, particularly with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints, indicating poor predictive ability for this dataset.

Figure 3g illustrates the recall scores of the classifiers across different molecular fingerprints. Random Forest, XGBoost, and ANN models achieve consistently moderate recall values. XGBoost in the Morgan dataset achieves higher recall, indicating better performance in identifying positive instances. Gaussian Naive Bayes, on the other hand, demonstrates inconsistent scores. Significantly higher recall scores were obtained, particularly with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints. In contrast, the scores are very low in other cases, suggesting limited ability to correctly identify true negative cases, except for the two cases. Heatmap Fig. 3h depicts the specificity scores of the classifiers across different fingerprints. Random Forest, XGBoost, and ANN are the highest performers. In contrast, Gaussian Naive Bayes exhibits lower specificity scores, especially with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints, suggesting its poor performance in correctly identifying true negative cases. Figure 3i showcases the balanced accuracy of each classifier and fingerprint combination. Balanced accuracy considers both sensitivity (recall) and specificity, providing a more balanced evaluation metric. Random Forest, XGBoost, and ANN models consistently achieve the highest balanced accuracy scores, demonstrating strong overall predictive performance. Gaussian Naive Bayes, however, demonstrates significantly lower balanced accuracy, particularly with AtomPairs and PubChem fingerprints, indicating low predictive performance.

The box plots in Fig. 4 illustrate the distribution of scores of different metrics across different molecular fingerprints. The accuracy and specificity scores (Fig. 4a,e) show a narrow distribution with consistently higher accuracies and specificities with values over 0.8 and 0.9, respectively, for almost all the fingerprints, signifying the comparable efficiencies of all the models across different fingerprints and descriptors concerning the two metrics. Whereas the box plots of ROC_AUC, F1, balanced accuracy, precision, and MCC scores across different molecular fingerprints (Fig. 4b,c,f,g,i) show a comparatively wide distribution, signifying the varying efficiency of the models for these metrics. A mixed distribution of scores was observed in the case of recall across different fingerprints and descriptors (Fig. 4d), whereas FPR scores show a narrow distribution, signifying parallel efficiency of all the models to the FPR metric (Fig. 4h). The presence of outliers suggests that certain models or corresponding datasets might have significantly different performances in terms of that particular metric.

Having the results of the performances of different models in hand, we went for the development of improved models further by combining each fingerprint (Morgan, Atom-pair, PubChem, and RDKit fingerprints) with RDKit descriptors, generating 35 models. The model’s performances were assessed across metrics such as ROC_AUC, accuracy, F1 score, specificity, balanced accuracy, precision, MCC, FPR, and recall for predicting anti-tubercular activity. Figures 5 and 6 compare fingerprint representations and their influence on model performance across different evaluation metrics by evaluating the corresponding heatmaps (Fig. 5) and boxplots (Fig. 6).

Heatmap for fingerprint + RDKit des and resultant metric comparison on various models. Demonstration of Model Performance Metrics Across Fingerprint Representations—(a) ROC-AUC, (b) Accuracy, (c) Recall, (d) Specificity, (e) Precision, (f) Balanced Accuracy, (g) F1 Score, (h) Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and (i) False Positive Rate.

Boxplot for fingerprint + Descr and resultant metric comparison on various models. Demonstration of Model Performance Metrics Across Fingerprint Representations—(a) ROC-AUC, (b) Precision, (c) Recall, (d) False Positive Rate, (e) Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), (f) Accuracy, (g) F1 Score, (h) Specificity, and (i) Balanced Accuracy.

The heatmap for ROC_AUC 5a illustrates the performance of six classifiers across various molecular fingerprints, evaluated by the ROC_AUC metric. XGBoost and Random Forest consistently demonstrate the highest ROC_AUC values, establishing the corresponding models as the top-performing for the dataset. On the other hand, Gaussian Naive Bayes exhibits significantly lower performance, particularly with atompair + RDKit des and PubChem + RDKit des, suggesting its unsuitability for the classification task. A similar pattern was observed for the accuracy and specificity (Fig. 5b,d). Figure 5c depicts the heatmap illustrating the recall scores of the classifiers across different RDKit descriptors combined with molecular fingerprints. Gaussian Naive Bayes achieves the highest recall values, particularly with AtomPairs + RDKit des, and PubChem + RDKit des, indicating strong performance in identifying positive instances. Random Forest, XGBoost, and ANN with RDKit demonstrate comparatively lower recall scores. The Heatmap 5e depicts the precision scores of the classifiers across different fingerprints. Random Forest outperformed other classifiers with the highest metric score, whereas XGBoost, ANN, and KNN maintained relatively high precision values. Gaussian Naive Bayes exhibits significantly lower precision, particularly with atompairs + RDKit des and PubChem + RDKit des, suggesting a high rate of false positive predictions.

The heatmap for Balanced Accuracy Fig. 5f showcases the balanced accuracy of each classifier and fingerprint combination. Balanced accuracy considers sensitivity (recall) and specificity, providing a more balanced evaluation metric. XGBoost demonstrates the highest demonstrating strong overall predictive performance. Gaussian Naive Bayes, however, demonstrates significantly lower balanced accuracy, particularly with atompairs + RDKit des and PubChem + RDKit des. The heatmap Fig. 5g illustrates the F1 scores of the classifiers across different molecular fingerprints. XGBoost consistently achieves the highest F1 score, indicating a good balance between precision and recall. On the other hand, Gaussian Naive Bayes demonstrates significantly lower F1 scores, particularly with atompairs + RDKit des and PubChem + RDKit des, suggesting suboptimal performance in terms of precision and recall. Figure 5h depicts Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient (MCC) for each classifier and fingerprint combination. XGBoost demonstrates the highest MCC score, indicating strong predictive performance. Gaussian Naive Bayes exhibits significantly lower MCC scores, particularly with atompairs + RDKit des and PubChem + RDKit des, suggesting limited predictive power for this dataset. The heatmap Fig. 5i showcases a False Positive Rate (FPR) for each classifier and fingerprint combination. XGBoost and Random Forest maintain relatively low FPR values, indicating good performance in minimizing false positive classifications. Gaussian Naive Bayes exhibits significantly higher FPR, particularly with atompairs + RDKit des and PubChem + RDKit des, suggesting a high rate of false positive predictions.

To illustrate and visualize the distribution of scores of different metrics across different molecular fingerprints, corresponding box plots were derived as shown in Fig. 6. The distribution pattern was similar concerning the performances of the previous models developed with only fingerprints and descriptors (Fig. 4). The FPR, accuracy, and specificity scores (Fig. 6d,f,h) show a narrow distribution with consistently lower false positive rates (below 0.07) and higher accuracies and specificities with values over 0.8 and 0.9 respectively for almost all the fingerprints signifying the comparable efficiencies of all the models across different fingerprints + RDKit des concerning the metrics. In contrast, the box plots of ROC_AUC, precision, MCC, F1, and balanced accuracy scores across different molecular fingerprints (Fig. 6a,b,e,g,i) show a comparatively wide distribution, signifying the varying efficiency of the models for these metrics. A mixed distribution of scores was also observed in the case of recall across different fingerprints + RDKit des (Fig. 6c), with a maximum score of around 0.6. The presence of outliers suggests that certain models or corresponding datasets might have significantly different performances in terms of that particular metric.

The strategy to combine RDKit descriptors with different sets of molecular fingerprints led to improved performance of the ML models. The optimal feature set was identified as RDKitDes + MorganFP. The performances of the classification models based on different ML algorithms for the RDKitDes + MorganFP on training data were evaluated in search of the best models among the developed models. A relative comparison of the performances is summarized in Table 1, highlighting the strengths and limitations of each approach. Table 1 indicates that among the individual models, the XGBoost (XGB) and Random Forest (RF) models built using Morgan and RDKit fingerprints achieved the best performance with an AUC of 0.8989 and 0.8932, with slightly better accuracy of 88.28%. was observed with the XGBoost (XGB) compared to the Random Forest (RF) with an accuracy of 86.97%. However, the recall score (0.2934) of the Random Forest (RF) model was significantly lower than that of XGBoost (0.5357), indicating limitations in detecting positive instances. This superior performance can be attributed to its gradient-boosting framework, which effectively captures non-linear relationships and handles complex data structures in molecular datasets. Tree-based algorithms like XGBoost are well-suited for these tasks due to their robustness in managing feature interactions and imbalanced data. The ANN model exhibited a balanced performance with an AUC of 0.8881 and an accuracy of 87.98%, but fell short in terms of its recall value (0.4875) compared to XGBoost. K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) demonstrated consistent metrics, including a high AUC (0.8913), balanced accuracy (0.7169), and precision (0.6979). Models like Naive Bayes (NB) and Logistic Regression (LR) showed relatively lower performance across most metrics.

Our analysis also highlights the performance differences between the models in terms of recall and precision. For instance, while Naïve Bayes (NB) achieved a high recall of 0.8227 (Table 1), its precision was notably low at 0.3047, suggesting a trade-off between detecting positive cases and avoiding false positives. This further emphasizes the need for ensemble methods to effectively balance these metrics.

To address the class imbalance issue and improve overall predictive performance, ensemble methods such as voting and stacking were employed. From the training results, the four best-performing models (XGB, DL, KNN, and RF) were selected and combined using voting and stacking methods to evaluate their performance on the test dataset. To our satisfaction, these ensemble techniques leverage the strengths of individual models for improved predictions.

When moving to ensemble strategies, Table 2 reveals that the stacking ensemble model outperformed all individual models by combining the predictions using a meta-learner, achieving an impressive accuracy of 90.69% and an AUC of 0.8063. This can be attributed to the model’s ability to leverage the strengths of multiple classifiers, effectively mitigating the weaknesses observed in individual models like RF and DL. Notably, the stacking model’s balanced accuracy (0.8063) and high F1 score (0.6683) underscore its effectiveness in managing both positive and negative predictions. The model demonstrated a low false positive rate (0.0537), ensuring reliability in predictions.

Furthermore, the voting ensemble strategy also delivered a competitive performance with an accuracy of 88.20% and an AUC of 0.8719 (Table 2). The precision (0.5522) and recall (0.8579) indicate the model’s ability to balance false positives and false negatives effectively. The superior balanced accuracy of 0.8719 highlights the ensemble’s capability to balance sensitivity and specificity, making it a robust approach for predictive tasks.

While the models exhibited strong performance on the training set, it is essential to assess their generalization ability. To this end, a test set was used for external validation (Fig. 7). The stacking model consistently outperformed individual models, highlighting the benefits of ensemble methods. However, it is important to note that the performance of DL models can be sensitive to the structural composition of the dataset.

Model interpretation by SHAP analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the established models, we used the SHAP method to identify the important structural features, calculating their contribution in the context of structural prediction of antitubercular molecules. Through SHAP analysis, we identified the key molecular features that drive the model’s predictions, summarized in Table 3.

As illustrated in Fig. 8, the SHAP method can be used to visualize the impact of specific molecular features on the predicted activity of compounds. For example, Figs. 8B,C show the SHAP values for different molecular features in the context of the compounds Moxifloxacin and Delamanid. The role of specific substructures in moxifloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic, was analyzed using Morgan fingerprints. Features Morgan 497 and Morgan 650 were identified as significant contributors to the XGBoost model’s predictions. These substructures enhance moxifloxacin’s efficacy against Mtb by influencing its interaction with bacterial enzymes critical for DNA replication. The role of specific substructures in Delamanid, a nitro-dihydro-imidazooxazole antibiotic, was also analyzed using Morgan fingerprints. Features Morgan 530 and Morgan 317 are identified as significant contributors to the XGBoost model’s predictions, as these substructures enhance Delamanid’s efficacy against Mtb by targeting mycolic acid synthesis, disrupting the bacterial cell wall structure and integrity, essential for Mtb survival.

Importance of the representative molecular descriptors (top 20) based on the XGBoost model. (A) The SHAP values for each molecular descriptor: Moxifloxacin; (B) Ten most important molecular descriptors toward Moxifloxacin; (C) Ten most important molecular descriptors toward Delamanid; (D) Important molecular substructures of Moxifloxacin; (E). Important molecular substructures of Delamanid; (F) ChemDraw structure of Moxifloxacin; (G) ChemDraw structure of Delamanid.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully developed and evaluated advanced machine learning models for predicting anti-tubercular activity, leveraging a diverse and significantly larger dataset compared to previous studies. By integrating seven classifiers with several possible combinations of molecular representations, 103 highly efficient, robust prediction models were developed. The evaluations of the developed models on different metrics resulted in quite improved results compared to the previous reports. Among the individual models, the XGBoost model developed on RDKit descriptors and Morgan fingerprints outperformed the others. In contrast, voting and stacking predominate in the case of ensemble models while dealing with the test datasets. Further, the SHAP method analyzed the contribution of the molecular features in predicting the anti-tubercular activity of molecules. Consequently, the best features were identified and validated using two drug molecules, namely Moxifloxacin and Delamanid.

Using a large dataset, robust models with better prediction performances, and diverse kinds of model analysis, our research demonstrates the development of significantly improved, reliable machine learning models compared to the previous ML models to predict anti-tubercular molecules. With these aspects, we expect that the developed models will be capable of accelerating tuberculosis research by efficiently identifying potential anti-tubercular drug candidates to reduce the time and cost associated with traditional preclinical drug-discovery approaches.

Data availability

In this study, publicly available raw data and synthetic data were used to build the classification models. The raw data can be accessed from ChemBL at [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/], providing a foundational dataset for our analysis. Additionally, we generated synthetic data tailored to our specific requirements to enhance our study. The complete codebase and the synthetic data are available in the link https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1AvwM4twZ6XbIdBD28-R6W9tFgYkzbBnk?usp=sharing to ensure transparency and reproducibility of our findings.

References

Global tuberculosis report 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Dey, R., Nandi, S., Samadder, A., Saxena, A. & Saxena, A. K. Exploring the potential inhibition of candidate drug molecules for clinical investigation based on their docking or crystallographic analyses against M. tuberculosis Enzyme Targets. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 20, 2662–2680 (2020).

Prasad, R., Singh, A. & Gupta, N. Adverse drug reactions with first-line and second-line drugs in treatment of tuberculosis. Ann. Natl. Acad. Med. Sci. 57, 15–35 (2021).

Moopanar, K., Nomfundo, A., Nyide, G., Senzani, S. & Mvubu, N. E. Clinical strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis exhibit differential lipid metabolism-associated transcriptome changes in in vitro cholesterol and infection models. Pathogens Dis. 81, ftac046 (2023).

Smith, I. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and molecular determinants of virulence. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16, 463–496 (2003).

https://www.cdc.gov/tb/signs-symptoms/index.html last browsed on 10.05.2025.

https://www.webmd.com/lung/understanding-tuberculosis-basics; browsed on 31.12.2023.

McIlleron, H., Meintjes, G., Burman, W. J. & Maartens, G. Complications of antiretroviral therapy in patients with tuberculosis: Drug interactions, toxicity, and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 196, S63–S75 (2007).

Chantaphakul, H., Cheungpasitporn, W., Ruxrungtham, K. & Klaewsongkram, J. Adverse reaction to anti-tuberculosis drugs. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125, AB154 (2010).

Mase, S. R. & Chorba, T. Treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis. Clin. Chest. Med. 40, 775–795 (2019).

Ahmed, S., Nandi, S. & Saxena, A. K. An updated patent review on drugs for the treatment of tuberculosis (2018-present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 32, 243–260 (2021).

Seung, K. J., Keshavjee, S. & Rich, M. L. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 5, a017863 (2015).

Benedetta, S. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibitors: An updated patent review (2021–present). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 34, 1215–1230 (2024).

Sekyere, O. J., Maningi, N. E. & Fourie, P. B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, antimicrobials, immunity, and lung-gut microbiota crosstalk: Current updates and emerging advances. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1467, 21–47 (2020).

Wu, C. et al. Effects of second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs on the intestinal microbiota of patients with rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 13, 1127916. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1127916 (2023).

Shetye, G. S., Franzblau, S. G. & Cho, S. New tuberculosis drug targets, their inhibitors, and potential therapeutic impact. Transl. Res. 220, 68–97 (2020).

Opromolla, D. V., de Lima, L. S. & Caprara, G. Rifamycin SV in the treatment of lepromatous leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 36, 123–131 (1965).

Ye, Q. et al. Identification of active molecules against Mycobacterium tuberculosis through machine learning. Brief. Bioinform. 22, 1–15 (2021).

Deb, U. & Biswas, S. Pretomanid: The latest USFDA-approved anti-tuberculosis drug. Indian J. Tuberc. 68, 287–291 (2021).

Conradie, F. et al. Treatment of highly drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 893–902 (2020).

Dorman, S. E. et al. Four-month rifapentine regimens with or without moxifloxacin for tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1705–1718 (2021).

Silva, D. R. et al. Bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, and moxifloxacin (BPaLM) for multidrug- or rifampin-resistant tuberculosis: A systematic review. J. Bras. Pneumol. 50, e20240295 (2025).

Dartois, V. A. & Rubin, E. J. Anti-tuberculosis treatment strategies and drug development: Challenges and priorities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 685–701 (2022).

Singh, V. Tuberculosis drug discovery & development: Drug targets, chemical matter, and approaches. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 755459 (2021).

Ejalonibu, M. A. et al. Drug discovery for Mycobacterium tuberculosis using structure-based computer-aided drug design approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 13259 (2021).

Ananthan, S. et al. High-throughput screening for inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Tuberculosis 89, 334–353 (2009).

Reynolds, R. C. et al. High throughput screening of a library based on kinase inhibitor scaffolds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Tuberculosis 92, 72–83 (2012).

Maddry, J. A. et al. Antituberculosis activity of the molecular libraries screening center network library. Tuberculosis 89, 354–363 (2009).

Khan, A. U. Descriptors and their selection methods in QSAR analysis: Paradigm for drug design. Drug. Discov. Today 21, 1291–1302 (2016).

Yang, X., Wang, Y., Byrne, R., Schneider, G. & Yang, S. Concepts of artificial intelligence for computer-assisted drug discovery. Chem. Rev. 119, 10520–10594 (2019).

Mswahili, M. E., Martin, G. L., Woo, J., Choi, G. J. & Jeong, Y.-S. Antimalarial drug predictions using molecular descriptors and machine learning against plasmodium falciparum. Biomolecules 11, 1750 (2021).

Xiong, Y. et al. Automatic detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis using artificial intelligence. J. Thorac. Dis. 10, 1936–1940 (2018).

Liang, S. et al. The application of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis and drug resistance prediction of pulmonary tuberculosis. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9, 935080 (2022).

Jamal, S. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning based prediction of resistant and susceptible mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 10, 5487 (2020).

Sharma, A. et al. An accurate artificial intelligence system for the detection of pulmonary and extra pulmonary Tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 131, 102143 (2021).

Acharya, V. et al. AI-assisted tuberculosis detection and classification from chest x-rays using a deep learning normalization-free network model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2399428 (2022).

Lewis, R. A. & Wood, D. Modern 2D QSAR for drug discovery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 4, 505–522 (2014).

Ekins, S. et al. Machine learning and docking models for Mycobacterium tuberculosis topoisomerase I. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 103, 52–60 (2017).

Winkler, D. A. The impact of machine learning on future tuberculosis drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 17, 925–927 (2022).

Prathipati, P., Ma, N. L. & Keller, T. H. Global Bayesian models for the prioritization of antitubercular agents. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 48, 2362–2370 (2008).

Ekins, S., Pottorf, R. & Reynolds, R. C. Looking back to the future: predicting in vivo efficacy of small molecules versus mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 54, 1070–1082 (2014).

Lane, T., Russo, D. P. & Zorn, K. M. Comparing and validating machine learning models for mycobacterium tuberculosis drug discovery. Mol. Pharm. 15, 4346–4360 (2018).

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/search_results/tuberculosis browsed on 09.07.2024.

RDKit Documentation. RDKit: Open-Source Cheminformatics Software. Available from: https://www.rdkit.org/docs/.

Breiman, L., Friedman, J., Olshen, R. & Stone, C. Classification and regression trees (Wadsworth Int. Group, 1984).

Cover, T. M. & Hart, P. E. Nearest neighbor pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 13, 21–27 (1967).

Duda, R. O., Hart, P. E. & Stork, D. G. Pattern classification 2nd edn. (Wiley, 2001).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction 2nd edn. (Springer, 2009).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep learning (MIT Press, 2016).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016, 785–794 (2016).

Zhou, Z.-H. Ensemble methods: Foundations and algorithms (CRC Press, 2012).

Powers, A. Evaluation: From precision, recall, and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness & correlation. J. Mach. Learn. Technol. 2, 37–63 (2011).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inform. Process Syst. 30, 30 (2017).

Lundberg, S. M., Nair, B. & Vavilala, M. S. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2, 749–760 (2018).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Acknowledgements

All the authors sincerely acknowledge Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University for providing literature access, research facilities and several other expenses related to the manuscript. S.C. thanks DST (INSPIRE division) for providing fellowship and research grants (INSPIRE Faculty Fellowship registration no: IFA17-CH274).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R. and S.G. carried out the data curating, writing the software, and drafting the paper. C.P. validated the method, analyzed the results, and assisted in drafting the paper. S.C. conceptualized the work, collected the data, supervised the work, and finalized the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Dedicated to Dr. Wahajul Haq acknowledging his exceptional contribution in the field of medicinal chemistry.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rawat, A., Gupta, S., Pal, C. et al. Development of machine learning models to identify potentially active compounds against tuberculosis. Sci Rep 15, 45678 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04668-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04668-z