Abstract

Full-color wavelength complex modulations are essential to usher in the era of holographic displays. Although metasurfaces have been developed for passive holograms, only a limited number of active metasurfaces capable of complex modulation in the visible wavelength range have been reported. In this study, we successfully optimized a liquid crystal on a metasurface device to achieve complex reflectivity modulation for the first time. Specifically, we achieved complete phase modulation over \(2\pi\) and amplitude modulation in the range of 0.3–0.6 at blue and green wavelengths and red wavelengths with varying antenna widths. Our analysis indicates that three coupled modes of surface plasmon polariton and gap surface plasmon are crucial in complex modulation for blue, green, and red color wavelengths, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light modulation is crucial in holographic displays because it creates realistic and interactive three-dimensional (3D) images1,2. Proper light modulation allows for accurately representing depth, motion, and perspective, making the holographic image appear more lifelike. In addition, controlled light modulation can provide a wide viewing angle and a larger field of view, enhancing the viewer’s experience.

In this regard, metasurfaces can be suggested as a technical means for effective and precise light modulation. The metasurface comprising subwavelength optical structures allows precise control over the phase, amplitude, and polarization of light at a scale previously unattainable with conventional optics. The inherent interference property of the metasurface can be used to modulate the amplitude of light waves by absorption or reflection. When the light impinges on meta-atoms, a unit structure of a metasurface, a phase shift occurs. Thus, by designing the arrangement and size of the meta-atom, it is possible to modulate the phase of the light. Practically, metasurface geometry can be tailored to achieve specific optical functionalities, such as optical sensing, imaging, telecommunications, and augmented reality.

While metasurfaces are promising for optical modulation, fabricating metasurfaces presents several technical challenges due to their nanoscale features and the precision required. Some important hurdles include nanoscale precision, materials selection, uniformity, and reproducibility slm-ito:Qiu20,slm-ito:park21,holo:kim2023,holo-vectorial:kim2021, lc-dual:jang22, And because metasurface is not used alone but with other components, integration and compatibility with existing platforms and technologies also strongly matter. With the technical objectivity of achieving complex optical modulation in the visible range, we present an optical modulator comprising a metasurface and liquid crystal (LC) parts.

Metasurfaces are typically static, but combining them with LCs’ dynamic functionality can be introduced3,4,5,6. The electrically tunable orientation of LC can significantly contribute to enhancing the capabilities of modulating the amplitude reflectivity and phase reflectivity. To be specific, the metasurface and LC components are designed to function as a coupled mode of gap surface plasmon and surface plasmon polariton and operate in twisted nematic mode, respectively7. Because our approaches function across the visible spectrum, including blue color, they can be applied to ultrahigh resolution displays in which high color quality is required. In this paper, we demonstrate the complex reflectivity modulation capability from blue to red color wavelengths.

Results and discussion

Fabrication of LConMeta device

We recently demonstrated complex reflectivity modulation at the orange color wavelength using a liquid crystal on a metasurface device (LConMeta). In our analysis, as reported in7, we analyzed the measured reflectance to extract the absorption characteristics as a function of the applied voltages across both the antenna and the metal electrodes.

Additionally, we proposed novel methods to estimate the phase characteristics from the reflectance of the LConMeta device. This was made possible due to the coupling between the metasurface reflection (signal wave) and the round-trip Fabry-Perot oscillation (reference wave) occurring within the liquid crystal. The metasurface device was recently applied to a wavelength-selective security device with versatile image representation, using a liquid crystal-based striped metasurface8.

Gap surface plasmon (GSP) modes are well-known for their behavior of bouncing off antenna edges9, and were utilized for orange color complex modulation in our previous work. However, we realized that achieving complex modulation across the entire visible wavelength range using a single GSP mode would be challenging.

Let us assume the initial resonance wavelength of the GSP mode is 550 nm. To cover the full visible spectrum for complex modulation, its resonance wavelength would need to be controlled across a range from 450 nm to 650 nm, requiring a variation of approximately ±20%. However, liquid crystals, which are widely used to adjust resonance wavelengths, exhibit a refractive index change of about 16% (e.g., from 1.51 to 1.75 in the case of E7).

To achieve complex modulation across the visible spectrum with this refractive index variation, the resonance wavelength of the GSP mode would need to respond quickly, with a sensitivity factor of 2.5 relative to the refractive index change. Unfortunately, it is well known that the resonance wavelength of the GSP mode is only weakly dependent on changes in the surrounding refractive index.

Thus, we moved away from using GSP mode and instead sought electrically adjustable resonance modes that are directly dependent on the refractive index change of the liquid crystal to enhance the sensitivity. We explored modes operating within the same device, each with different initial resonance wavelengths, such as 470 nm ±10%, 530 nm ±10%, and 660 nm ±10%. Since the required variation for each resonance wavelength is smaller than the refractive index changes, controlling the device becomes more feasible.

To explore new modes for modulating full-color wavelength complex reflectivity, we examined six LConMeta devices featuring reduced antenna widths while maintaining antenna pitches similar to those of orange wavelength devices, which have a width of 95 nm and a pitch of 158 nm.

Figure S1 in the supplementary file shows top-view Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of these metasurface devices, each defined by variations in antenna widths, spacings, and pitches. We labeled each device according to its row and column position on the sample wafer. Although 16 metasurface devices were fabricated and measured, our analysis focuses on six devices—from (1,1) to (2,3)—that exhibited distinct reflectance characteristics.

The antenna dimensions (widths, spacings, and pitches) for these selected devices are summarized in Table 1.

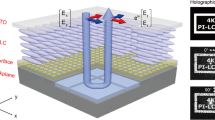

Modeling of the LConMeta device

Figure 1a illustrates a schematic representation of a liquid crystal (LC) integrated with a metasurface device. The metasurface is composed of the following key components: Metal Electrode acts as one of the conductive components, enabling the application of voltage to control the liquid crystal orientation. Oxide Dielectric serves as an insulating layer that separates the electrodes, ensuring electrical isolation. Antenna Electrode positioned above the oxide dielectric enhances electromagnetic interactions and plays a crucial role in resonance phenomena. The E7 liquid crystal occupies the cell gap and exhibits distinctive electro-optical properties that are influenced by the applied electric field.

(a) Schematic diagram of a liquid crystal on metasurface device: The foundation of the device consists of a 100 nm-thick layer made of TiW (10% titanium and 90% tungsten). A 15 nm-thick \(\hbox {Al}_2\hbox {O}_3\) (alumina) thin film is deposited over the TiW layer using atomic layer deposition (ALD). A patterned antenna, consisting of 40 nm-thick molybdenum, is deposited on top of the \(\hbox {Al}_2\hbox {O}_3\) film using electron beam lithography (EBL). The space above these structures is filled with E7 liquid crystal, known for its excellent electro-optical properties that enable dynamic light modulation when electrically controlled. The rotation of the liquid crystal is schematically drawn in four combinations of \(\hbox {V}_{antenna}\) = 0 V or 1 V and \(\hbox {V}_{metal}\) = 0 V or − 1 V. The red line is the electric field line. (b) The reflectivity of the LConeMeta device can be modeled with the modified Fabry-Perot oscillator. \(\psi _{LC}\) represents the round-trip propagation phase delay in LC\(\_\)1, \(r_{11}\) is the surface reflectivity coefficient at the air/liquid crystal boundary, \(t_{12}\) is the transmission coefficient at the air/liquid crystal boundary, \(r_{22}\) and \(t_{21}\) represent the reflectivity and transmission coefficients at the liquid crystal/air boundary, and \(|\rho _{22}| e^{\phi _{meta}}\) is the complex reflectivity at the liquid crystal/metasurface boundary. (c) Metasurface can generate the plasmon waves such as SPP (surface plasmon polariton) and GSP (gap surface polariton). (d) Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) image, which provides a detailed view of the microstructure and the layering within a sample metasurface device.

In the initial state, the liquid crystal is in the twisted nematic phase, where the direction of the liquid crystal near the top electrode is along the rubbing direction (the x-axis) and the direction of the liquid crystal near the antenna electrode aligns with the antenna direction (the y-axis) due to the anchoring effect of the the metasurface device.

When a voltage is applied only at the antenna electrode, an electric field is generated to cause both the liquid crystals between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode as well as the region at the top of the antenna electrode. When we remember that the electric field will be perpendicular to the metal boundary, the liquid crystal will rotate to the perpendicular direction when the applied voltage is enough to overcome the elastic energy term of the liquid crystal.

When a voltage is applied only at the metal electrode, the electric field generated between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode will be similar to that generated when a voltage is applied only at the antenna electrode. However, there will be a negligible electric field on top of the antenna electrode.

when a voltage is applied at both the antenna electrode and the metal electrode, the electric field at the top of the antenna electrode will originate from the antenna electrode voltage, while the electric field between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode will arise from the voltage difference between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode.

This reorientation alters the refractive index in the vicinity of the metasurface device, leading to shifts in resonance wavelengths. By dynamically modulating the applied voltage, the optical properties and functionalities of the LConMeta device can be precisely controlled.

The reflectance of the LConMeta device can be modeled with the modified Fabry-Perot oscillator, as shown in Fig. 1b, and can be represented as follows,

where \(\psi _{LC}\) represents the round-trip propagation phase delay, \(r_{11}\) is the surface reflectivity coefficient at the air/liquid crystal boundary, \(t_{12}\) is the transmission coefficient at the air/liquid crystal boundary, \(r_{22}\) and \(t_{21}\) represent the reflectivity and transmission coefficients at the liquid crystal/air boundary, and \(|\rho _{22}| e^{\psi _{meta}}\) is the complex reflectivity from the metasurface boundary10. Since surface reflection is not critical for the subsequent analysis, we approximated the reflectance using Eq. (2) with \(r_{11} = 0.\)

The Fabry-Perot oscillator assumes that the complex reflectivity, \(\rho _{22}\), is independent of wavelength. Under this assumption, the reflectance of the Fabry-Perot oscillator exhibits a uniform oscillation magnitude and reaches a local reflectance maximum at the wavelength condition \(\psi _{LC} + \psi _{meta} = (k_0 + k) 2 \pi\). Here, the mode number is expressed as the sum of a fixed integer, \(k_0\), and a variable integer, k, for analytical convenience.

In an LConMeta device, as a modified Fabry-Perot oscillator, the complex reflectivity, \(\rho _{22}\), becomes wavelength-dependent near the resonance wavelength of the metasurface. The metasurface in Fig. 1c can generate plasmon waves such as SPP (surface plasmon polariton), GSP (gap surface polariton) along the boundary of the metal electrode and the dielectric as shown in Fig. 1d, and becomes resonant when the plasmon waves bounce off the boundary and interfere constructively interference with itself.

Absorption characteristics as a function of voltages

To investigate the resonance modes, we first analyze the absorption characteristics of the LConMeta device, as shown in Fig. 2a, b.

Analysis of the reflectance for the (1,3) metasurface device when the metal electrode voltage is − 0.9 V. (a) From the reflectance data, we extract the local maximum reflectance (red), local minimum reflectance (green), and absorption (calculated as the difference between the local maximum and minimum reflectance, shown in blue) when the antenna voltage is 1.3 V. The numbers at the peaks correspond to the Fabry-Perot resonance mode number, \(k_0 + k\). (b) A contour plot of the extracted absorption is shown for different antenna voltages. The cyan-colored region is the area of no interest, as the reflectance in this region is higher than that of the highest contour line. (c) From the reflectance, the experimental peak wavelength (shown in black) is collected and fitted (in red) using the perturbed Fabry-Perot resonance equation (Eq. 3). By analyzing the difference between the experimental data and the fitting, we can extract the phase information of the metasurface (in magenta) using equation (Eq. 2). By focusing on the phase change from positive to negative, we can obtain the resonance wavelength. (d) The obtained resonance wavelength with different voltages of the antenna electrode and the metal electrode in the (1, 3) metasurface device.

The absorption characteristics (depicted in blue) as a function of wavelength were obtained by subtracting the local minimum reflectance (green) from the local maximum reflectance (red), calculated using the nearby maximum/minimum method. The maximum absorption of the metasurface device occurs at the wavelength where the reflectance difference within the Fabry-Perot oscillation is minimized.

For the (1,3) metasurface device, the maximum absorption occurs at 530 nm when the antenna electrode voltage is 1.3 V, and the metal electrode voltage is − 0.9 V. As shown in Fig. 2b, the maximum absorption wavelength of the LConMeta device decreases as the voltage applied to the antenna electrode increases.

Because the maximum absorption wavelength is related to the resonance mode wavelength of the metasurface device, we can infer the origin of the resonance mode of the metasurface device.

When the voltage of the metal electrode is fixed, the voltage applied to the antenna electrode enhances the alignment of the liquid crystal’s molecules in the direction of the electric field as shown in Fig. 1. However, E7 liquid crystal has a positive anisotropic refractive index; the refractive index of the longer axis is higher (1.75) than that along the short axis (1.51). Therefore, the directional alignment of the liquid crystal due to the increase of the voltage of the antenna electrode induces an increase of the refractive index in the horizontal direction (the x-axis) along the side of the antenna electrode and in the vertical direction(the z-axis) along the top of the antenna electrode

However, the resonance wavelength of surface plasmon polariton between the metal and the dielectric is proportional to \(\sqrt{\frac{1}{{n_{LC}}^2} + \frac{1}{{n_{Metal}}^2}}\) where \(n_{LC}\) is the refractive index of the liquid crystal along the electric field direction on the boundary.

From the downward movement of the resonance wavelength of the surface plasmon polariton as a function of the antenna voltage, we can conjecture that the resonant mode of the metasurface device comes from the refractive index increase in the horizontal direction along the side of the antenna electrode and in the vertical direction along the top of the antenna electrode.

If we add the other control parameter of the voltage of the metal electrode, we need to modify the modeling slightly.

As shown in Fig. S2 in the supplementary file, the voltage of the antenna electrode for the strong absorption is not a constant but a function of the voltage of the metal electrode. As the voltage of the metal electrode is lowered, the voltage of the antenna electrode for the strong absorption decreases as well.

That is, the alignment of the liquid crystal along the side of the antenna electrode is controlled by the voltage difference between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode.

Phase characteristics of LConMeta device

Now, let’s focus on the reflectivity phase of the LConMeta device. Typically, reflectance data does not include phase information. However, when coupling is involved, we can extract the reflectivity phase indirectly.

From Eq. (2), we understand that when \(\psi _{LC} + \psi _{meta} = (k_0 + k) 2 \pi\), a local maximum reflectance occurs at the wavelength corresponding to the local maximum wavelength (\(\lambda _p\)), within Fabry-Perot oscillation. The local maximum wavelength satisfies the following equation.

If we fit the inverse of local maximum wavelength as a function of natural number, k, with linear regression as shown in Fig. 2c, we can obtain round-trip propagation distance, \({2 n_{LC} h_{LC}}\), from the slope and constant mode number, \(k_0\) from the intercept of the linear regression.

From \(\psi _{meta} = (k_0 + k) 2 \pi - \psi _{LC}\) , the reflectivity phase of the metasurface was calculated in Fig. 2c. By focusing on the phase change from positive to negative, we can observe the resonance at a 540 nm wavelength, which is consistent with Fig. 2b when the voltage of the antenna electrode is 1.3 V and the metal electrode is − 0.9 V.

By gathering the resonance wavelength as a function of the voltage of the metal electrode, as shown in Fig. 2d and in Fig. S3 of the supplementary file.

To directly measure the phase of the metasurface device, we set up the lateral shear interferometer using a displacer and polarized camera to measure the phase of the LConMeta device7.

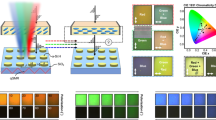

Complex reflectivity (a) at 473 nm for the (1,2) metasurface device and the (2,1) metasurface device, (b) at 532 nm for the (2,1) metasurface device and the (2,2) metasurface device, (c) at 660 nm for the (1,1) metasurface device and the (1,3) metasurface device. The antenna voltage is from 0.1 V to 2.5 V, and the metal voltage is from − 0.1 V to − 2.5 V.

To check the complex modulation in the full color wavelength, we used a diode laser with a 473 nm, 532 nm, and 660 nm wavelength to measure the phase of the metasurface device and plot the complex reflectivity, as shown in Fig. 3 (Figs. S4, S5, and S6 in the supplementary file shows complex modulation characteristics at 473 nm, 532 nm, 660 nm wavelength in six devices, respectively.)

In the blue color wavelength of Fig. 3a, five out of six metasurface devices show complete 2\(\pi\) modulation as a function of the voltages of the antenna electrode and the metal electrode. Additionally, the (1,2) and (1,3) metasurface devices show amplitude modulation from 0.3 to 0.6, which is comparable to the modulation in7.

After completing the measurement at the blue color wavelength of 473 nm, we changed the diode laser to the green color wavelength of 532 nm. Figure 3b shows the complex reflectivity coefficient at 532 nm by combining the square root of the reflectance and the phase from the lateral shear interferometer. Four out of six devices show the complete 2\(\pi\) modulation, and (2,1) and (2,2) metasurface devices show similar amplitude modulation ability of 0.3\(\sim\)0.6.

When we use a red color laser of 660 nm, Fig. 3c shows the complex reflectivity coefficient at 660 nm by combining the square root of the reflectance and the phase from the lateral shear interferometer. Two out of six devices show the complete 2 \(\pi\) modulation, and (1,1) metasurface devices show similar amplitude modulation ability of 0.3\(\sim\)0.6.

Origin of the resonance modes in LConMeta device

To check the origin of the resonance mode of the LConMeta device, we first calculate the liquid crystal directional distribution as a function of the voltage using FEM (finite element method, scifem)11 and imported it to the FDTD (finite difference time division, Lumerical) to obtain the electromagnetic profiles as shown in Fig. 4. The magnitude of electric field (Ex, Ey, Ez), magnetic field (Hx, Hy, Hz), and pointing vector (Px, Py, Pz) are calculated with (1, 2) metasurface device when the antenna voltage is 0.1 V and the metal voltage = − 0.1 V.

Compared with the electromagnetic field distribution of those of previous devices, such as Fig. 5 in the previous paper7, which had an antenna width of 95 nm and showed complex modulation due to the GSP (gap surface plasmon polariton) mode, we can understand the following characteristics.

There is also a GSP-like mode with a strong Px (x component pointing vector) between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode. Because we already know that the GSP mode is not possible in the visible wavelength due to the small antenna width below 63 nm, we consider that the GSP-like mode might occur through the coupling with the other modes.

The other characteristic is a strong y-component magnetic field, Hy, along the side of the antenna electrode as shown in the Fig. 4. In the surface plasmon polariton theory, the Hy field propagates in the vertical direction (the z-axis) along the side of the antenna electrode because SPP moves along the boundary of the metal and the dielectric. So the associated electric field direction of the SPP will be the horizontal direction (the x-axis). That means the refractive index increase along the horizontal direction at the side of the antenna electrode influences the resonance wavelength of the SPP directly, which is consistent with the experimental conjecture. That is, the resonance of the LConMeta device will be a function of the difference between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode, which will induce reorientation of the liquid crystal along the horizontal direction.

However, there is also a strong x-component magnetic field, Hx, along the top of the antenna electrode. In the same way as the strong magnetic field along the side of the antenna electrode, the x-component magnetic field, Hx, means that SPP will propagate in the antenna direction (the y-axis). So the associated electric field direction will be vertical (the z-axis). That means the refractive index increase along the vertical direction at the top of the antenna electrode influences the resonance wavelength of the SPP directly, which is consistent with the experimental conjecture as well.

To understand the relation between the resonant modes and the strong magnetic fields (Hy field along the side of the antenna electrode and the strong Hx field along the top of the antenna electrode), we explore the magnetic field distribution of the LConMeta device as a function of the incident light wavelength as shown in Fig. 5.

(a) The resonance wavelengths of six LConMeta devices. Magnetic field strength of the (1, 2) LConMeta device at the incident light wavelength of (b) 643 nm, (c) 541 nm, and (d) 464 nm. The schematic diagram for (e) STSG (\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)-\(\hbox {SPP}_{top}\)-\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)-GSP) mode, (f) SGS (\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)-\(\hbox {GSP-SPP}_{side}\)) mode, and (g) STS (\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)-\(\hbox {SPP}_{top}\)-\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)) modes. (h) The estimated resonance wavelength of coupled STSG, SGS, STS modes.

From the above analysis, we learned that a strong Hy field along the side wall and a strong Hx field along the top of the antenna electrode are important to enhance the resonance wavelength movement with applied voltages of the antenna electrode and the metal electrode.

Figure 5a is the collection of the resonance wavelength of the LConMeta device in six devices as a function of the voltages of the antenna electrode and the metal electrode. It clearly shows that there are three regions: blue region (resonance wavelength is between 450 nm and 500 nm), green region (resonance wavelength between 500 nm and 550 nm), red region (resonance wavelength between 600 nm and 700 nm).

At three different regions, the magnetic field strength shows somewhat characteristic profiles such as in Fig. 5b–d. In the red region of Fig. 5b, there is a strong H field at the gap between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode, and the magnetic field at the antenna electrode is connected through the side of the antenna electrode and to that of the top of the antenna electrode. In the green region of Fig. 5c, there is a strong H field at the gap between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode, and it is connected to that of the side of the antenna electrode. In the blue region of Fig. 5d, there is a strong H field at the top of the antenna electrode, which is connected to that of the side of the antenna electrode. The H field at the gap between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode is relatively smaller than that of the top electrode.

From the magnetic field strength profile, we assumed three resonance modes as shown in Fig. 5e–g. The first mode for the blue region is the STS (\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)-\(\hbox {SPP}_{top}\)-\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)) mode, which combines the top SPP wave and the side SPP wave. The second mode for the green region is the SGS (\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)-GSP-\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)) mode, which combines the GSP wave and the side SPP wave. Final mode is STSG (\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)-\(\hbox {SPP}_{top}\)-\(\hbox {SPP}_{side}\)-GSP) mode, which combines the GSP wave, top SPP wave, and the side SPP.

All three modes are designed to include the side SPP wave to include the experimental result that the resonant wavelength is a function of the voltage difference between the antenna electrode and the metal electrode, but have different propagation wavevectors to explain the three different regions. We can use the coupled mode theory to calculate the propagation wavevector of the GSP wave, the top SPP wave, and the side SPP wave. For the suggested mode, we calculate the resonance wavelength as follows.

where \(\beta _{side}, \beta _{top}, \beta _{GSP}\) is the propagation wavevector of the side SPP, top SPP, and GSP waves, and w, h are the width and the height of the antenna electrode, respectively.

Figure 5h shows the calculated resonance wavelength as a function of the refractive index of the liquid crystal. The resonance wavelength of the STS mode is in the blue color region, that of the SGS mode is in the green color region, and that of the STSG is in the red color region. All three suggested modes explain the resonant wavelength of the LConMeta device.

Experimentals

Metasurface structure of the LConMeta device

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram for a liquid crystal on a metasurface device with a TEM image.

As a metal electrode, TiW (10 \(\%\) titanium and 90 \(\%\) tungsten) was selected due to the process compatibility in comparison with Ag and the high atomic number useful for an electron beam align key fabrication. Then, a 15 nm thick \(\hbox {Al}_2\hbox {O}_3\) thin film covered a 100 nm TiW metal electrode via atomic layer deposition. Finally, 40 nm thick molybdenum was deposited and patterned by electron beam lithography for the antenna electrode. Molybdenum was critical for the LConMeta device because it has the property to align the liquid crystal horizontally along the antenna electrode without rubbing material such as polyimide.

Liquid crystal of the LConMeta device

Removing the rubbing material in the LConMeta device is crucial for the complex modulation. Removing the rubbing material only enables the liquid crystal to fill the gap between the antenna electrodes. The liquid crystal can change the refractive index as a function of the voltages of the antenna electrode and the metal electrode, which are the key mechanisms for complex modulation. For the liquid crystal, we used E7 (Merck) and filled the LConMeta with a twisted nematic mode.

LConMeta device has three electrodes: the top electrode, the antenna electrode, and the metal electrode. The top electrode is the common electrode fixed to zero voltage and works as the reference voltage of the liquid crystal movement. The voltages of the antenna electrode and the metal electrodes were varied with a 1 kHz square wave pattern, and the voltage of the antenna electrode was out of phase with the voltage of the metal electrode. We will display the voltage of the antenna electrode as a positive number and the voltage of the metal electrode as a negative number, to recall the phase difference.

Coupled mode theory

The propagation wavevector of the GSP wave can be obtained using the coupled mode theory as shown in7.

where \(\epsilon _{antenna}\), and \(\epsilon _{LC}\) represent the dielectric constants of the antenna electrode, and the liquid crystal, respectively12.

Conclusion

We successfully demonstrated blue-to-red color complex reflectivity modulation using the LConMeta device. The reflectivity phase modulation was a complete 2 \(\pi\) radian, and the reflectivity amplitude modulation ranged from 0.3 to 0.6.

The essential idea for achieving complex modulation across the entire visible wavelength range was to divide the target wavelength range using different resonance modes and increase the resonance wavelength variation by optimizing the sensitivity to the refractive index controllability of the liquid crystal.

Recently, we have successfully applied LConMeta device to a wavelength-selective security device with versatile image representation8. Because the LConMeta device is dependent on the polarization of the incident light, controlling the polarization states via LCs enables the desired images with flexibility.

More direct application for the beam steering and the hologram reconstruction using the complex modulation characteristics of LConMeta device is the next target. For the direct application, we also need to consider the control logic. In the unit pixel of the application device, such as SLM, there are transistors, capacitors, and a light modulation device such as LConMeta. Because the fill factor, the area ratio between the LConMeta and the unit pixel, is usually 50 %, the realistic amplitude modulation will be different from that of the LConMeta device because of the uncontrolled area.

To confirm the possibility of the hologram reconstruction with small amplitude modulation, we compared the complex hologram with 6 levels (2 levels for amplitude modulation and 3 levels for phase modulation) with a phase hologram or an amplitude hologram with 6 levels, as shown in Fig. S7 in the supplement file. We confirmed that only 6 levels of digitization in the complex modulation can reconstruct the image well.

The suggested resonance modes worked even when the width of the antenna was only about 40 nm to 60 nm, making the application to high-definition optical devices, such as spatial light modulators, promising. The bottleneck of the spatial light modulator in the visible wavelength range was the pixel pitch of the modulator, which could be overcome with the liquid crystal on a metasurface device.

To enhance the modulation of the reflectivity amplitude, we need to consider the metal materials more carefully. Because Ag is prohibited in the semiconductor industry and Al is notorious for oxidation, we used TiW as an alternative for the metal electrode. However, TiW shows low reflectance, lowering the Fabry-Perot oscillation magnitude. In the future, we will test other metal electrode materials or other structural designs to enhance the amplitude modulation capability.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Jiang, Q., Jin, G. & Cao, L. When metasurface meets hologram: principle and advances. Adv. Opt. Photon. 11(3), 518–576. https://doi.org/10.1364/AOP.11.000518 (2019).

Kim, G. et al. Metasurface-empowered spectral and spatial light modulation for disruptive holographic displays. Nanoscale 14, 4380–4410. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1NR07909C (2022).

Veetil, R. M. et al. Nanoantenna induced liquid crystal alignment for high performance tunable metasurface. Nanophotonics 2023, 55 (2023).

Sharma, M., Hendler, N. & Ellenbogen, T. Electrically switchable color tags based on active liquid-crystal plasmonic metasurface platform. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8(7), 1901182. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201901182 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Metasurface-enabled high-resolution liquid-crystal alignment for display and modulator applications. Laser Photon. Rev. 16(1), 2100396. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202100396 (2022).

Driencourt, F. F. et al. Electrically tunable multicolored filter using birefringent plasmonic resonators and liquid crystals. ACS Photon. 2020, 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphotonics.9b01404 (2020).

Kim, Y.-H. et al. Complex reflectivity modulation characteristics at visible wavelength using liquid crystal on a metasurface device. Adv. Photon. Res. 2024, 2400135. https://doi.org/10.1002/adpr.202400135 (2024).

Yu, J.-S., Kim, Y.-H., Hwang, C.-S. & Kim, J.-H. Wavelength-selective security device with versatile image representation in a liquid crystal-based striped metasurface. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 58(16), 165101. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/adbaff (2025).

Ding, F., Yang, Y., Deshpande, R. A. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. A review of gap-surface plasmon metasurfaces: fundamentals and applications. Nanophotonics 7(6), 1129–1156. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2017-0125 (2018).

Emeric, L., Deeb, C., Pardo, F. & Pelouard, J.-L. Critical coupling and extreme confinement in nanogap antennas. Opt. Lett. 44(19), 4761–4764. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.44.004761 (2019).

Gustafsson, T. & McBain, G. D. Scikit-fem: a Python package for finite element assembly. J. Open Sourc. Softw. 5(52), 2369. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.02369 (2020).

Sndergaard, T. & Bozhevolnyi, S. I. Strip and gap plasmon polariton optical resonators. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 245(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.200743225 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (RS-2021-NR057360, RS-2024-00408286, RS-2020-NR049597, RS-2021-NR066115). This work was supported by Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) grant funded by the Korean government (23ZH1300, Research on hyper-realistic interaction technology for five senses and emotional experience).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H.Kim wrote the main manuscript, J.Moon prepared the figures, K. Choi, J.H.Yang, J.E.Pi, J.H.Choi, C.S.Hwang fabricated the metasurface devices. J.S.Yu and J.H.Kim provided the LC on the metasurface. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, YH., Choi, K., Moon, J. et al. From blue to red color wavelength complex modulation characteristics of liquid crystal on a metasurface device. Sci Rep 15, 19283 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04777-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04777-9