Abstract

Animal glues have been used since antiquity, but their popularity decreased in the twentieth century with the rise of synthetic adhesives. Currently they are primarily used in restoration of works of art. This study focuses on animal glue samples derived from bone and hide tissues used mainly for veiling and carpentry applications, examining their secondary structure, thermal and rheological properties, to shed light into their adhesive behaviour. Thermogravimetric analysis and differential scanning calorimetry highlight differences between hide and bone glues, showing that the latter are more hydrolysed. The calorimetric curves show varying values of denaturation enthalpy thus indicating a varying degree of gelatine renaturation. Additionally, the calorimetric analysis demonstrates the physical ageing of the glue samples, which is known to play a key role in maintaining their adhesive properties under specific storage conditions. The rheological data provide fundamental information on properties which are relevant for the use of animal glues as adhesives in various applications. XRD data suggest a low structural order in the samples investigated, where the amorphous component complicates the univocal interpretation of the spectra. FTIR reveal a relatively high content of β-structures in all commercial glue samples, as well as gelatine and collagen standards. Moreover, spectra of the glue films dried for 1 week show that the β-structures are recovered following dissolution in water and application. Therefore, β-structures seem crucial to explain the structure-dependent mechanical properties observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Animal glues have been used for centuries as adhesives in a variety of applications1,2. The earliest evidence of its use dates back to the Palaeolithic period, where traces of animal glue were found in cave paintings3. In later years, the use of animal glues became an integral part of various industries and everyday life4,5. In the twentieth century, the demand for animal glue declined due to the advent of synthetic adhesives and animal glue remained the adhesive of choice for traditional bookbinders, luthiers and restorers6,7.

For the conservation of artifacts, animal glues and synthetic glues are used alternatively based on the type of intervention to be carried out. Animal glues are mostly used in countries such as Italy or Spain, since they are traditionally employed in their restoration processes and old recipes. Animal ones follow one of the cardinal principles of modern conservation, the compatibility of restoration materials with the constituent materials of ancient works8. This characteristic is not found in synthetic glues.

On the other hand, synthetic adhesives are useful in case of unfavorable thermo-hygrometric conditions of the conservation environment of the artwork, in this case it is preferable to introduce a more inert, not hygroscopic material that cannot be attacked by microorganisms.

Scientific research is trying to experiment with mixtures of both natural and synthetic glues9, to exploit the good characteristics of both.

The glue production process from animal tissue involves the hydrolysis and denaturation of native triple helix of collagen to obtain water-soluble gelatine, mainly in a random coil conformation10,11,12,13,14.

Typically, the glue production process consists of several steps: (1) the raw material is washed with cold water to remove residual blood and other impurities; (2) the washed material is pre-treated in acids or alkalis; (3) the treated material is boiled in water at temperatures of around 60–70 °C for several cycles; (4) the “glue liquor” obtained is dried and crushed into flakes or pellets12.

Glues derived from hide are usually pre-treated with lime, an inorganic material consisting mainly of calcium oxides and hydroxides, while those derived from bone are pre-treated in dilute acids10,13. The temperature of the boiling process can also vary, but in this case, it mainly depends on the age of the animal: the older the animal, the higher the temperature used14.

The amino acid composition of gelatine may differ slightly from that of collagen as the manufacturing process may result in the chemical modification of the amino acids14. For example, the alkaline process employed for gelatine extraction results in the deamination of glutamine15. Consequently, the primary structure of gelatine closely resembles that of collagen, with glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline as the main amino acids. However, its secondary and higher-order structures are significantly different. A partial recovery of the collagen structure occurs during cooling and drying, where the helices partially reform. This process is called renaturation or gelation process14. The structural order achieved depends on the molecular weight of the polypeptide chains and on several other factors including their amino acidic composition (mainly Pro and Hyp content). The molecular weight distribution of the gelatine polypeptides depends on the production process, which causes molecular degradation16 as well as the type of tissue and the age of the animals.

As reported by Elharfaoui et al.16, the extraction of highly cross-linked collagen from old tissue results in the formation of high molecular weight gelatine molecules. However, these molecules are highly branched making the renaturation very improbable.

Guo et al.17 reported that gelatine can be organised in different ways depending on the length of the α-chains, which also affects the stability and reversibility of these structures. Different types of reorganisation at a higher structural level can occur involving one or more helices linked by hydrogen bonds17. These lead to the formation of gel junction zones which act as sites for the formation of a three-dimensional network. The structural order of the network depends on molecular weight and chemical composition (mainly Pro and Hyp content) of gelatine molecules. Long, high molecular weight chains and high Pro and Hyp content promote highly ordered network18,19.

There are some studies in the literature that investigate the chemical structure of glue and relate it to the mechanical and adhesive properties of animal glues20,21,22, but the adhesion mechanism is far from being well understood.

Literature reports that the content of native-like triple helixes formed during the renaturation process is important as it affects the thermal, mechanical and adhesive properties of the glues20,21,22.

The degree of renaturation and the structural order achieved by the gelatine also depends on the storage conditions, in particular temperature and humidity23,24,25. Obas et al.23 have reported that in high-solids confectionary gel made with gelatine, the amount of renatured structures is reduced when the gelatine sample is stored at or above the gelling temperature (20 °C). Furthermore, Dai et al.24. have observed that the amount of structural gelatine in films is strictly dependent on the drying temperature with the degree of renaturation decreasing as the temperature increases. Recently, Mosleh et al.26 have reported on the effect of hygrothermal ageing on the properties of various gelatine glues films from mammalian and fish tissues, showing how humidity and temperature affect the microstructure of the gelatine and, thus, the mechanical properties of the glue.

Generally, the presence and content of triple-helix-like structures are determined through X-ray diffraction analysis and differential scanning calorimetry as the enthalpy of denaturation is positively correlated with the amount of triple-helix-like structures21,22,23,26,27,28. The few studies reported in the literature directly correlate the amount of triple helices present with the mechanical and adhesion properties. In particular, a greater quantity of these structures leads to a reduction in the degree of swelling, an increase in gel strength (higher degree of Bloom) and an increase in Young’s modulus20,21.

β-structures have an influence on the properties of silk protein and gelatine-electrospun materials29,30, but the effect of β-structures on the mechanical properties of adhesives has not been investigated. Therefore, this aspect warrants attention and should be considered in the study of gelatine-based adhesives.

Further insights can be gained from the calorimetric analysis of polymers and biopolymers. From the enthalpy relaxation superimposed on the glass transition, it is possible to obtain insights into physical ageing. Physical aging in polymers and biopolymers refers to the gradual changes in the physical properties of a polymeric material over time due to its molecular structure and the environmental conditions it is exposed to. This process is related to the relaxation of the polymer’s chains toward a more thermodynamically stable state. As polymers age, they can undergo various physical changes that can impact their mechanical, thermal, and optical properties31,32.

Physical ageing is commonly observed when an amorphous polymer is rapidly cooled below its glass transition temperature (tg) and then stored at a temperature below tg31. An amorphous polymer in the glassy state is in a non-equilibrium condition, whereas in the rubbery state, above the glass transition temperature, it reaches an equilibrium state. Consequently, if the polymer is stored at a temperature below its tg, it will gradually tend to relax towards a state of thermodynamic equilibrium. Physical ageing affects the thermodynamic and mechanical properties of the polymer31. The identification of this phenomenon is crucial in material studies, particularly in the pharmaceutical and food area, as it offers valuable insights into optimal storage conditions, shelf life, and how material properties may evolve over time due to factors such as temperature, humidity, and irradiation. Therefore, although this phenomenon has primarily been studied in synthetic polymers31,33,34,35,36,37, recent interest in examining the physical aging of biopolymers has grown. These studies have observed physical ageing in carbohydrates38,39 and several protein-based materials40,41,42,43,44.

Literature reports that in synthetic glues physical ageing affects their properties causing a reduction in adhesion strength, an increase in brittleness, a loss of structural integrity, and a loss of flexibility45,46,47. Recently it has been reported that physical ageing can affect also the properties of gelatine glue. Enrione et al.48 has conducted a study of physical aging of a model gelatine film, which was prepared obtained by dissolving salmon gelatine in water and then drying it, using the same procedure applied in the production of animal glue. The results have showed that during the ageing of the model gelatine film the material changes its mechanical properties becoming stiffer. Physical ageing causes also a modification in porosity and density. All these can decrease the adhesive properties over time26,49.

In this study, we have examined the structural characteristics of a subset of gelatine-based animal glues derived from hide and bone tissues, among those characterized by Ntasi et al.50, and compared them to commercial collagen, gelatine A and gelatine B. The work of Ntasi et al.50 focused on the determination of the animal origin, degree of deamidation of glutamine and asparagine, the molecular weights of the acid-soluble collagen fraction, backbone cleavage and the amount of 2,5-diketopiperazines produced during thermal degradation. Table 1 reports the samples investigated in this work and it also includes a summary of the main results of Ntasi et al.50 on the same samples.

The glues analysed were divided into two main groups based on the material used in their production. The first group includes glues derived from hide, further divided into HP and HM depending on whether they come from a single animal (HP) or from multiple animals (HM). The second group includes glues derived from bones (BM), all from multiple animals.

All HM and HP glues were originally labelled as “rabbit glues,” while BM glues were categorized as “strong glues.” However, this classification did not reflect the real biological origin of the materials, as pointed out in the study by Ntasi et al.50. The labels mainly referred indeed to the adhesive properties of the glues themselves. The “rabbit glues”, compared to other animal-based glues, are distinguished by their transparency, stability and good elasticity. Because they can be diluted in varying proportions, their adhesive strength can be adjusted, making them ideal for tasks such as veiling and small bonding applications. In addition, they can be combined with gypsum to fill any imperfections51. Generally, rabbit glues have a high bloom strength, ranging from 300 to 550 g52.

Samples of HM and HP were used, for example, to make the plastering of a 15th-century painting on panel and plaster of Bologna (Fig. 1a, HP3 sample) and the veiling of a 17th-century painting on canvas (Fig. 1b, HM1 sample).

(a) Plastering with rabbit glue and Bologna gypsum, “Sacred conversation with the Madonna of the girdle”, Unknown, fifteenth century, panel painting, church of SS. Annunziata—Sorrento (NA); (b) Facing with rabbit glue,” portrait of a warrior”, Unknown, seventeenth century, canvas painting, private collection; (c) preparation of BM5 glue samples; (d) use of BM5 glue in carpentry.

The “strong glue”, derived primarily from the bones of large animals, offer adhesion, stiffness and heat resistance greater than rabbit glue. These adhesives are commonly used for structural bonding, often in combination with nails, joints and strong materials that require considerable holding force. Figure 1c,d reports the preparation and the use of BM5 in carpentry. Typically, strong glues are classified as low Bloom degree, with values ranging from 50 and 300 g52.

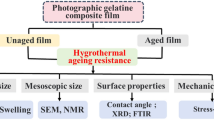

In this work we have used thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), to compare their thermal degradation profiles, attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) to obtain information on their secondary structures, including helix, β-structures and random coil content, and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to determine temperature and denaturation enthalpy, glass transition temperature (a useful parameter for the application of protein biomaterials), and enthalpy relaxation related to physical ageing. XRD diffractograms and rheological data have been collected on a sub-set of samples to obtain information about the degree of crystallinity, viscosity, gel strength, shear resistance, and gelation temperature which are fundamental parameters for the study of adhesive materials.

Materials and methods

The animal glue samples were provided by Museo Nacional del Prado (Madrid) and restoration workshop of the University Suor Orsola Benincasa (Naples). Table 1 reports the samples’ list including sample name, and a summary of the main results for each sample obtained by Ntasi et al.50, such as taxonomy, molecular weight (MW) of acid soluble collagen (ASC) obtained by SDS-PAGE, backbone cleavage %, and the area of the pyrolytic signals related to all 2,5-diketopiperazines (DKPs) detected by Py-GC/MS. According to this, the samples were classified as Hide Pure (HP), Hide Mixed (HM) and Bone Mixed (BM).

Standard gelatine A from porcine skin (G2500, MW = 50–100 kDa) and gelatine B from bovine skin (G9382, MW = 40–50 kDa) and standard collagen derived from calf skin (Bornstein and Traub Type I) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). These samples were characterized for their taxonomy, backbone cleavage % and deamidation degree, according to the protocols reported in Ntasi et al.50, except for minor modifications due to changes in the laboratory equipment and software availability (refer to the section “Materials and methods” in the supplementary material for details). A summary of the main results obtained is also given in Table 1.

For rheological and XRD analysis, a representative subset of glue samples was selected including HM1 and HM4 among mixed hide samples, HP6 and HP4 among pure hide samples, BM1 and BM5 among bone-derived samples.

The solutions for rheological analysis were prepared dispersing the solid in deionized water in a concentration of 6.6%m/v for 24 h and then heating at 60 °C for 30 min. Subsequently the samples were centrifugated at 360 rpm for 30 s to eliminate the air micro bubbles. This preparation methodology is inspired by the procedure traditionally used for glue preparation in handicrafts, and the choice of the 6.6% m/v concentration is according to Bloom’s degree determination6,53,54.

The glue films for XRD analysis were obtained by brushing the solution (6.6%m/v aqueous solution) on a glass slide for a representative sub-set of glue samples (HM1, HM4, HP6, HP4, BM1, BM5). The glue films were left to dry for 1 week at room temperature before the analysis.

Both the solution and film samples were also analysed by ATR-FTIR.

Thermogravimetric analysis

TG measurements were conducted on collagen, gelatine A and B and on solid glue samples using TA Instruments Thermobalance model Q5000IR, from 25 to 900 °C, at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The thermogravimetric analysis was carried out under nitrogen flow (25 mL/min). Approximatively 5 mg of sample were weighted and put in platinum crucibles. The instrument was mass calibrated using certified mass standards in the range of 0–100 mg and temperature calibrated using five reference materials (Alumel, Ni, Ni83%Co17%, Ni63%Co37%, Ni37%Co63%). TA Universal Analysis 200 ver. 4.5A was employed for data treatment.

Differential scanning calorimetry

DSC analyses were performed by TA Instruments Discovery DSC model 250 under nitrogen flow (50 mL/min). The instrument was temperature calibrated with indium. For each sample, about 5 mg was weighted and hermetically sealed into aluminium DSC pans. An empty pas was used as a reference.

Collagen, gelatine A and B, and solid glue samples were subjected to heating/cooling/heating cycle in the temperature range of 10–130 °C at heating rate of 10 °C/min and cooling rate of 50 °C/min.

Physical ageing study was carried out on glue samples consisting of one type of collagen belonging to the same animal species, Bos taurus, i.e. HP3, HP4, HP6, HP8 samples and on one sample derived from bone tissue, namely BM5. The procedure was the following. The samples were heated/cooled/reheated under the same conditions as described above, and after the second heating scan, the samples were cooled to 40 °C (temperature below the glass transition temperature) at 50 °C/min, held at 40 °C (annealing temperature) for up to 3 h and heated to 130 °C at 10 °C/min. The samples were then cooled to 40 °C at 50 °C/min, held at 40 °C for up to 6 h and heated to 130 °C at 10 °C/min. The sequence was repeated with the sample held at 40 °C for up to 12 h. The same procedure was repeated at an annealing temperature of 30 °C only on HP6 in order to confirm the presence of physical ageing. This procedure was inspired by Farahnaky et al.40.

For each calorimetric method used, a baseline was recorded and subtracted from the calorimetric curve of each sample. TRIOS v5.1.1 was employed for data treatment.

Attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

ATR-FTIR investigation of the protein secondary structure in the collagen, gelatine A and B and animal glue samples was performed using a Perkin-Elmer Frontiers FTIR spectrophotometer, equipped with a universal Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory and a triglycine sulphate TGS detector.

To monitor any changes in the secondary structure during the process of glue dissolution in water and subsequent drying, spectra were recorded on: (1) all commercial glue samples as is; (2) few microliters of 6.6%m/v solution of a representative sub-set of glue samples described in before; and (3) a representative sub-set of glue film described in before. For the ATR measurements of the solution few microliters of 6.6%m/v solution were deposited on the ATR crystal and left to dry for few seconds.

All the spectra were recorded in the 4000–600 cm−1 range in ATR mode after background acquisition. For each sample, 128 scans were recorded, averaged, and Fourier transformed to generate a spectrum with a nominal resolution of 4 cm−1. Spectrum software (Perkin-Elmer) and a written-in house LabVIEW program for peak fitting were employed to run and process spectra, respectively55,56,57. A straight baseline passing through the ordinates at 1800 cm−1 and 1480 cm−1 was subtracted before processing the curves, and the spectra were normalized in the 1700–1600 cm−1 region. This approach was taken to avoid artefacts in absorptions near the limits of the region examined. The second derivatives of the amide I band of the spectra examined were then analysed to determine the initial data (number and position of the Gaussian components) required for the deconvolution procedure. The amide I band was chosen for structural analysis because of the very low contribution of the amino acid side chain absorptions present in this region58,59, and its higher intensity compared to the other amide modes (amide II at 1540 cm−1 and Amide III between 1350 and 1190 cm−1). Based on the infrared assignment of amide components, assuming that the extinction coefficient is the same for all the secondary structures, the secondary structure composition can be obtained from the FTIR spectra. The percentages of the different secondary structures were estimated by expressing the amplitude value of the bands assigned to each of these structures as a fraction of the total sum of the amplitudes of the amide I components. Although the general validity of the above assumption about extinction coefficients remains to be verified, there are studies in the literature that show good correlation between the distribution of secondary structures obtained by FTIR and X-ray crystallography approaches, suggesting that the assumption made is reasonable56.

X-ray diffraction

X-ray powder diffractograms were collected using a Bruker D8 Venture single-crystal diffractometer equipped with a Photon III CCD area detector, available at Center for Instrument Sharing of the University of Pisa (CISUP), simulating a Gandolfi-like geometry (microfocus CuKα radiation).

The analysis was conducted on the representative sub-set of commercial glue samples and films described before to check for the presence of crystalline domains.

Rheological analysis

Rheological measurements on gelatine standards and glue solution samples described before were conducted by Thermo Scientific HAAKE Rheostress 6000 controlled stress rheometer equipped with Peltier temperature control unit. The geometry plate-plate with 35 mm diameter, and a gap of 0.3 mm was used.

In steady state condition the viscosity flow curves were obtained by rotational measurements in which the shear rate (\(\dot{\gamma }\)) was varied in the range 1–100 s−1 and the shear stress (τ, Pa) was recorded. The range of shear rate investigated was chosen considering a manual application of the glue, by brush or spatula, which is the commonly used method for applying these samples. The viscosity (ƞ, Pa s) was obtained by the ratio between τ and \(\dot{\gamma }\).

Temperature sweep test was performed varying the temperature in the 15–40 °C range at shear stress of 0.1 Pa and frequency of 1 Hz (values within the linear viscoelastic range). The presence of a gel point can be determined by the presence of a cross-over point between storage modulus (G′, parameter proportional to the elastic/solid component of the material) and loss modulus (G″, parameter proportional to the viscous/liquid component of the material). RheoWin DataManager software was employed for data treatment.

Results

Thermogravimetric analysis

The thermal degradation of collagen, gelatine standards and glue samples was investigated by TGA under nitrogen flow. Figure 2 shows thermogravimetric (TG), and differential thermogravimetric (DTG) curves obtained for all samples.

All the samples exhibit the same thermal degradation profile, which primarily consists of two steps. The first mass loss (10–12% w/w) below 60 °C is due to moisture evaporation and the second (65–75% w/w) centred at 300–320 °C is due to protein pyrolysis resulting in the formation of 2,5-diketopiperazines (DKP), the most abundant of which in the glue samples are cyclo(Pro-Gly) and cyclo(Pro-HyP)50 and of several aromatic and nitrogen-containing compounds, such as pyrrole, indole, phenol, and the respective alkylated compounds60,61.

The residue at 900 °C is in the range of 15–20% w/w, as generally reported in literature for proteins. Table S1 shows the percentage mass loss and the corresponding temperatures determined for each sample.

Standard collagen showed an additional degradation step below 200 °C. As reported in the literature, this is due to the evaporation of the strongly H-bonded water involved in the stabilization of the triple helix62,63,64.

By observing the shape of the DTG related to water loss, gelatine standards exhibited a broader signal over a wide temperature range (from 30 to 200 °C) indicating the presence of structural water. The DTG curves of glue samples suggest that HP3, HP6 and HM5 contain more structural water than the standard gelatine, while the other samples have little to none.

Different degree of hydrolysis of collagen and the different animal species can affect the thermal degradation50,65,66,67.

By considering the tendset and tonset (Table S2), a slight difference was observed for gelatine standards, as gelatine A has tonset higher than gelatine B that indicates higher thermal stability, but tendset lower than gelatine B, i.e. a lower amount of thermostable cross-linked/aggregated structures. This result agrees with the literature and depends on the different production process used. Gelatine A undergoes an acid pretreatment whereas gelatine B undergoes a basic pretreatment. This leads to gelatine with different properties and, in general, gelatine A is less covalently cross-linked than gelatine B68, probably due to the protonation of groups involved in cross-linking formation.

A slight shift of the maximum towards lower temperatures was observed for animal glue samples, suggesting the presence of more hydrolysed molecules compared to gelatine and collagen. Furthermore, looking at the tendset in Table S4, BM sample completed its degradation at a lower temperature than the other samples. This result further suggests a higher degree of hydrolysis, a lower degree of aggregation and the presence of molecules with a lower molecular weight in BM samples, as reported by Ntasi et al.50, who identified highly hydrolysed collagen in BM samples through the SDS-PAGE, backbone cleavage percentage and Py-GC/MS analysis (Table 1). Another factor to consider is the percentage of deamidation. Notably, hide glues exhibit higher levels of deamidation compared to bone glues50. This increased deamidation can result in a higher number of charges, potentially leading to the formation of more thermally stable aggregates.

Regarding the HP and HM samples, no clear difference in thermal degradation was observed. Both HP and HM samples have a tonset lower than that of collagen and gelatine and a tendset lower than collagen but equal to or higher than that of gelatine, indicating the presence of more hydrolysed molecules as well as thermostable aggregates.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Calorimetric analysis was performed on glue samples to obtain information on the thermal stability of the protein structures and to compare them with those of gelatine and collagen standards. The calorimetric curves obtained are reported in Fig. 3. The glass transition temperature (tg) and associated heat capacity change (∆Cp) determined from the first and second heating scans, onset temperature (tonset), peak temperature (tpeak), width signal expressed as the difference between the temperature at the start and end of the event (∆t), and enthalpy (∆H) calculated for the two signals observed in the first heating scan only are reported in Table S3.

The calorimetric curve of the collagen standard showed in the first heating scan a broad endothermic signal between 36 and 121 °C with a maximum at 82 °C accounting for 18 J/g as enthalpy value and ascribable to collagen unfolding69. In the second heating scan, the only signal observed was the glass transition occurring at almost 0 °C. This result is not expected, as the literature reports a glass transition temperature for tendon collagen of around 40–45 °C70,71. No information is provided about the processes undergone by standard collagen, but this difference may suggest that standard collagen is not in its native form and has undergone a treatment that partially altered its structure, as also observed in the secondary structure analysis.

The unfolding enthalpy of collagen reported in the literature is in the range 40–50 J/g70,71. Our lower value could be due to a partial denaturation of collagen, as indicated by the β-sheets content. Considering the proximity of β-sheets and native collagen helix in the Ramachandran plot72, collagen is unlikely to return to its native shape, but rather it could give rise to β-sheet structures, which are notoriously very stable.

The calorimetric curve of both gelatine A and B showed two distinct endothermic signals during the first heating scan. The first signal (6 J/g and 12 J/g, respectively) at about 70 °C is an overshooting overlapped to the glass transition. The second signal (11 J/g and 3 J/g, respectively) at 95 °C corresponds to the unfolding of the gelatine structure, which is associated with the degree of renaturation of the gelatine25,71. The results indicate that gelatine A exhibits a higher degree of renaturation compared to gelatine B. This difference may be attributed to variations in their covalent cross-linking levels, as well as the conditions (temperature and humidity) during the renaturation process. The presence of a higher number of covalent bonds in gelatine B may hinder the reorganisation, resulting in a lower degree of renaturation.

The calorimetric profiles of all glue samples in the first heating scan were similar to gelatine more than collagen, displaying two endothermic signals: the first in the temperature range 50–80 °C, overlapping the glass transition, the second, in the temperature range 80–110 °C (Fig. 3). In the second heating scan all the analysed samples exhibited only the signal related to glass transition (Figure S1 in supporting information).

The signal superimposed to the glass transition was better investigated in order to confirm it to be associated with structural relaxation associated with physical ageing of the sample as reported in literature for synthetic polymers, some proteins and gelatines25,40,73,74.

The study of physical ageing was performed on glue samples of the same animal origin (HP3, HP4, HP6, HP8) to reduce the variability associated with different animal sources and on one bone glue sample (BM5) to confirm the presence of this phenomenon also in the bone glues. To study the physical ageing, after the first heating up to 130 °C, the samples were kept at 40 °C (temperature below the tg) for different periods of time (3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h) as specified in the experimental section and heated to 130 °C in order to observe the enthalpy relaxation signal. Since the extent of physical ageing depends on the annealing temperature, the experiment was repeated on sample HP6 also at the annealing temperature of 30 °C. Specifically, as the annealing temperature increases, both the peak temperature and the relaxation enthalpy value also increase40,41,75. The values of the enthalpy relaxation and the peak temperature calculated at each time point are reported in the table S4. Figure 4 reports the DSC curves obtained for HP6 as example.

DSC curves of HP6 before and after physical ageing: black line: first heating at 10 °C/min from 10 to 130 °C; grey line: second heating at 10 °C/min from 10 to 130 °C; green line: third heating at 10 °C/min from 10 to 130 °C carried out after 3 h of isothermal; purple line: fifth heating at 10 °C/min from 10 to 130 °C carried out after 12 h of isothermal at 40 °C; orange line: fifth heating at 10 °C/min from 10 to 130 °C carried out after 24 h of isothermal at 40 °C.

The characteristics of this relaxation peak are compatible with the physical ageing phenomenon occurring in the glues, as described in the literature40: the signal intensity increases over time and the peak temperature increases linearly with the logarithm of the ageing time (Fig. 5). The same behaviour was observed for BM5 (Table S4).

Regarding the glass transition, when applied to proteins, this term refers to the change in the dynamic properties of proteins that takes place at a specific temperature. It has been reported in the literature that at temperatures above the glass transition the dynamics of protein molecules are dominated by large scale motions of groups of atoms, whereas at lower temperatures vibrational motions predominate. The temperature at which this change in molecular dynamics occurs is influenced by the degree of hydration of the protein and the intrinsic temperature dependence of the motions76.

All the glue samples have the same moisture content (around 10%, as proved by TGA data reported below) and the tg values, obtained from the first heating scan, range from 52 °C (i.e., HP8) to 73 °C. (i.e., HM1), with the gelatine A and B values almost in the middle at 62 °C and 68 °C, respectively, without any clear correlation with the animal source (Figure S1 and Table S3). In general, tg is lower in the second heating scan compared to the first one, except for HP4 and HP8, which exhibited nearly the same temperature. As reported in ref34 and by Tseretely and Smirnova77, this is due to the release of bounded water during the denaturation process, which acts as a plasticiser by lowering the tg.

The values of the heat capacity change (∆Cp) associated with the glass transition, are in the range 0.65–1.3 J/Kg and 0.53–1.3 J/Kg calculated from the first and second heating scan, respectively. These values agree with the data reported in literature on amorphous gelatines and disordered crystalline gelatines76 and they are slightly higher than those reported for other proteins32,43,78.

All the glues (both from hide and from bone) show the relaxation enthalpy peak superimposed to the glass transition with values varying between 5 (i.e., HP4 and HP8) and 11 J/g (i.e., HM4). The value obtained for gelatine is 6 J/g as well as HM5 (Table S3a). For the collagen standard, as well as BM3, BM4, and BM5 samples, it was not possible to determine the relaxation enthalpy associated with the glass transition due to the signal overlapping with other signals at higher temperatures. This signal is often overlooked and there are few studies in which the enthalpy relaxation has been determined in gelatinous samples. Enrione et al.48, determined the enthalpy associated with physical ageing of fish gelatine film and obtained a value of 2.42 J/g after an ageing of 40 h at annealing temperature 5 °C lower than tg, i.e., 29 °C. The higher enthalpy relaxation values of the glue samples obtained in this study could be due to the annealing temperature used, which was 20–30 °C lower than tg. In these conditions, the enthalpy relaxation can be higher because the sample is far away from equilibrium state.

The unfolding peak in the hide glues is well separated in temperature from the relaxation enthalpy peak with a tpeak varying between 89 °C (i.e., HP8) and 100 °C (i.e., HM1) and enthalpy values varying between 3 (i.e., HP3) and 11 J/g (i.e., gelatine and HP6), and almost absent in HP4 and HM4. These values are lower than those obtained for collagen, indicating a lower structural order due to the higher degree of hydrolysis and lower molecular weight of the gelatine molecules that hinder renaturation77.

For bone glues is not possible to determine separate values for the relaxation enthalpy and for the unfolding one, because all the DSC peaks are partially superimposed.

Secondary structure of gelatine in animal glue samples

ATR-FTIR analysis was carried out on commercial animal glue samples, collagen, gelatine A and B, solutions and films of the representative sub-set described in “Materials and Methods section”. (HM1, HM4, HP6, HP4, BM1, BM5), to investigate the protein secondary structures. Figure S2, S3 and S4 shows the FTIR spectra obtained for all commercial samples, for the sub-set solutions and for the sub-set films. Spectra display the typical features of protein materials, i.e. the amide I band in the 1700–1600 cm−1 region (corresponding to C=O stretching vibration), the amide II in the 1600–1480 cm−1 region (corresponding to out-of-phase combination of the NH in plane bend and the CN stretching vibration) and the amide III in the 1350–1190 cm−1 region (corresponding to in-phase combination of the NH bending and the CN stretching vibration)16. The amide I frequency is strongly affected by the protein conformation16, consequently the amide I shift observed in the animal glue samples clearly indicates a change in the protein structure.

To gain a deeper understanding of the gelatine conformation, a curve-fitting method was applied to deconvolve the complex amide I band, allowing for the determination of the different percentages of secondary structures55,56,57.

Characteristic components of the Amide I band are assigned to the following secondary structures: helix (1650–1660 cm−1), random (1637–1660 cm−1), collagen native triple helix (1660–1666 cm−1), antiparallel β-sheets (two components around 1620 cm−1 and 1690 cm−1), parallel β-sheets (one component around 1630 cm−1), β-turns (1670–1685 cm−1)59. Table 2, Table S5 and Table S6 show the secondary structure percentages, the wavenumber in cm−1 and half height bandwidth (HHBW), based on the results of the peak fitting of Amide I band, of all the commercial samples (Table 2), of the sub-set solutions (Table S5), and of the sub-set films (Table S6). Figure 6 compares the data of secondary structure of all glue samples of the sub-set and the reference gelatine A and B.

The assignment of the bands assigned to helix and random coil structures is challenging, as the bands due to these structures overlap in these kinds of samples because of the wide bandwidth of the band assigned to random structure and the likely low percentage of helix (Table 2). Thus, it was not possible to discriminate between these two structures in all glue samples.

The assignment to β-sheet structures in Table 2 includes parallel and antiparallel β-sheets and β-turn59,79.

The results obtained on the standard of collagen indicate that the collagen is not in its native form, as a significant amount of β-structures are present. The same results can be observed for gelatine standards.

Looking at the results shown in Fig. 6, the secondary structures of gelatine A and B samples undergoes similar changes after the dissolution and 7 day drying process, and they remain predominantly random/helix and β-sheet structures. The analysis of gelatine A and B solutions on ATR crystal show a certain percentage of helix (10–35%). All solid glue samples are predominantly β-sheet and helix/random structures. Once dissolved in water, the random structure increases and their structural order decrease. After 7 days drying the “strong glues” BM1 and BM5 recover more than 50% of β-sheets respect to the initial β-sheets content (BM1 = 128% and BM5 = 56%). “Rabbit like-glues” HM1, HM4 and HP4 recover less than 60% of β-sheets, whereas “fish like-glue” HP6 recover about 100%.

XRD measurements were performed on a subset of solid glues before and after dissolution in water and drying to check for the possible presence of crystalline domains (Figure S5). The XRD diffractograms are characterized by a broad characteristic peak, more or less visible, around 2θ = 8.0° and another around 20°20,26,80, resulting in agreement with those reported in the literature for gelatins. However, these profiles are suggestive of low-order material where the amorphous component complicates the univocal interpretation of the XRD spectra.

Bond strength, viscosity and viscoelastic properties of animal glue samples

The rheological behavior of animal glue samples during the laying and application steps were studied by recording the steady-state flow curve and temperature sweep.

Figure 7 and Figure S6 show the flow curves and the trend of G’ and G’' as temperature changes, respectively.

The results show higher viscosity and pseudoplastic behaviour for both standards gelatine and HM1 glue. The other samples have viscosity lower than gelatines and HM1 and they show a decrease in viscosity in the shear rate range from 1 s−1 to about 10 s−1. In contrast, for shear rates above 10 s−1 they exhibit Newtonian behaviour. The different behaviours observed may be due to the difference in molecular weight of the gelatines. Higher viscosity and pseudoplastic behaviour are indicative of the presence of molecules with longer chains that can form stronger and more robust polymer networks.

From the curves obtained from the temperature sweep measurements (Figure S3), it results that sample BM5 behaves like a liquid over the entire temperature range investigated, as the loss modulus is always higher than the storage modulus. For the other samples, it is possible to identify the temperature at which the sol–gel transition occurs. Gelatine A and HM1 have a gelation temperature (32 °C) higher than the other samples. Gelatine B gel has a gelation temperature at 29 °C and following a decreasing order we find HM4, HP6, BM1 and HP4 (Table 3). Gelling temperature is a key parameter in the use of glues because it determines the transition between the liquid and gelled state of the material. This has a direct impact on viscosity, which in turn affects both ease of application and adhesive performance. The temperature at which gelation occurs depends on the molecular weight. Gelatins with higher molecular weights exhibit a higher gelation temperature.

Another important parameter for evaluating the performance of a glue is the shear resistance. An indication of this parameter can be provided by observing the value of the storage modulus (G'). Specifically, considering 25 °C as the reference temperature, glues with higher G’ value will have higher shear resistance. The data show that gelatine A has the highest shear resistance compared to the others, followed by HM1, gelatine B, and HM4. HP4, HP6, BM1 and BM5 have a very low G’ value, thus showing very low shear resistance (Table 3).

Regarding bond strength, in the case of gelatine, this is referred to the Bloom’s degree, which is the measure of gel strength of a 6.6% m/v solution6,53,54, and is related to the length and degree of cross-linking of the chains. Generally, the higher the MW of the gelatine the higher the degree of Bloom. High Bloom degree gelatines are characterized by having a high gelation temperature, a high G’ shear modulus, and higher viscosity. Therefore, considering the rheological data obtained, we can classify HM1 as a high Bloom degree glue, while all others as low Bloom degree glues.

Discussion and conclusion

TGA data clearly indicated that glue samples are more similar to gelatine than to the reference collagen. Therefore, they do not show the degradation step at around 200 °C that is due to the evaporation of the strongly H-bonded water involved in the stabilization of the triple helix62,63,64. In addition, they present an unfolding enthalpy that is less than half of that of collagen.

HP and HM samples are less hydrolyzed than BM samples, having an average MW above 40 KDa (Table 1). HP4 and HM4 appear to be the glue samples with the lowest degree of structural order given their low enthalpy value (about 1 J/g). This is likely due to the conditions used during the drying process after extraction, the storage conditions and the possible presence of covalent cross-linking preventing renaturation.

BM3, BM4, and BM5 have exhibited a calorimetric curve significantly different from the other samples. Their signal consists of several overlapping signals, likely due to the higher degree of hydrolysis in the gelatine, as it was found by Ntasi et al.50. This suggests that a well-defined three-dimensional network is unlikely to form, but rather several aggregates with lower structural order. In contrast, BM1 and BM2 displayed a denaturation signal similar to that of HP and HM samples, indicating a higher degree of renaturation compared to the other BM samples.

Rheological results obtained revealed that HM1 showed a high degree of Bloom. A glue with a high degree of Bloom is more difficult to apply uniformly, tends to form stiffer films with higher cohesion, which may improve the strength of the glue once dry, but may reduce the initial adhesiveness compared to glue with a lower degree of Bloom. HM1 is confirmed to have a “rabbit glue” behaviour and it is commonly used in veiling restoration (Fig. 1b). A lower degree of Bloom leads to a less viscous and more fluid glue, which promotes better penetration into porous materials and thus more effective adhesion on some surfaces. Glues with a low degree of Bloom can form more flexible films, which is useful for applications in which the glue must retain some elasticity after drying. The BM samples with a low Bloom’s degree are “strong glue” employed in carpentry (Fig. 1c,d).

Another key observation in this study is that the physical ageing characterizes all the glue samples analysed, regardless of animal origin or tissue type. As reported in the literature, the enthalpy relaxation value is influenced by storage conditions, including temperature and humidity. Since the glass transition temperature is higher than room temperature, physical aging will inevitably occur, and because it affects the mechanical properties of the material, it should be considered when animal glues are used.

XRD data collected on a sub-set of glue samples investigated in this work, both before and after dissolution in water show profiles in agreement with the XRD diffractograms reported in literature for the animal glues20,26,80. These profiles are suggestive of a low-order material where the amorphous component complicates the univocal interpretation of the spectra. Thus, XRD measurements, as well as FTIR analysis, make objectively impossible to discriminate the helical component from the random one.

FTIR results revealed a relative high content of β-structures in all commercial glue samples, gelatine and collagen. This highlights that it is extremely difficult to obtain native collagen after the extraction process from tissue and it explains the low denaturation enthalpy of collagen. Moreover, spectra of the glue films dried for 1 week at room temperature have shown that the secondary structure tends to return to the structure of the solid glue before the dissolution process. It is important to highlight that, under the drying conditions used, gelatine molecules assemble into β-sheet structures rather than α-helix. Probably, under these conditions, the formation of hydrogen bonds is favoured, which guide the reorganisation into β-sheet. In fact, in the literature, many studies reported on the effect of the drying conditions on the structural reorganization of gelatine protein23,24,25,26. Saiani et al.81 reported that the type of surface on which the peptide dries can also induce one type of secondary structure rather than another.

The percentage of β-structure recovery partially correlates with the adhesive behaviour of the glues studied. In fact, “strong glues” (BM1 and BM5), characterized by a very short setting time, show a very high degree of β-structure recovery after 1 week of drying, while “rabbit-like glues” (HM1, HM4 and HP4) show a lower one, with some variability within the subset. “Fish-like glue” (HP6) recovers almost as well as a strong glue. This behaviour suggests that the presence of β-structures has an influence on adhesiveness, but other factors play a role in the adhesive and mechanical behaviour of a gelatine glue such as molecular heterogeneity mainly due to the processing history. The gelatine adhesives analysed are inherently polydisperse mixtures, containing a range of fragments including α-, β-, and γ-chains, as well as smaller peptides17. This work and the work of Ntasi et al.50 show that these samples have different degrees of hydrolysis and different degrees of deamidation, resulting in different molecular weights and charge distributions. Thus, the structural and mechanical characterization could be specific to each gelatine depending on its manufacturing conditions.

The presence of β-sheet structures in the examined glues could contribute significantly to their mechanical properties, as it is reported in the literature that β-sheet protein structures thanks to the architecture of their hydrogen bonds give molecular assemblies characterized by extraordinary strength and unique properties. The zig-zag pattern, stabilized by hydrogen bonds is further stabilized by hydrophobic interactions between sheets and are held together by van der Waals interactions82,83,84. These structures are known for their high resistance to rupture and high strength (e.g. in silk exhibiting high tensile strength and in amyloid fibrils forming rigid, cohesive structures)85,86,87. Moreover, in gelatine-electrospun materials was observed that the stiffness increases with the increasing of β-sheet content30.

Although the structural analysis of gelatine in the literature is focused on the evaluation of the triple helix content using X-ray diffraction, supported by DSC results21,23,25,26,48,78,88 and structure property studies link the mechanical properties of glues to the triple helix content21,23,26, we believe that in animal glues, it is crucial to consider not only the triple-helix-like structures but also the amount of β-sheet structures to explain the structure-dependent mechanical properties and the adhesive mechanism.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Adhesives. in Building Decorative Materials (eds. Li, Y. & Ren, S.) 325–341 (Woodhead Publishing, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857092588.325

Pearson, C. Animal Glues and Adhesives (2003). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203912225.ch21

Solazzo, C. et al. Identification of the earliest collagen- and plant-based coatings from Neolithic artefacts (Nahal Hemar cave, Israel). Sci. Rep. 6, 31053 (2016).

Lucas, A. & Harris, J. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries (Courier Corporation, 2012).

Bleicher, N., Kelstrup, C., Olsen, J. V. & Cappellini, E. Molecular evidence of use of hide glue in 4th millennium BC Europe. J. Archaeol. Sci. 63, 65–71 (2015).

Handbook of Adhesives. (Springer US, 1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-0671-9

Schellmann, N. C. Animal glues: A review of their key properties relevant to conservation. Stud. Conserv. 52, 55–66 (2007).

Brandi, C. Teoria Del Restauro.

Colombo, A., Minotti, D., Mecklenburg, M., Cremonesi, P. & Rossi Doria, M. Studio Delle Proprietà Meccaniche di Consolidanti Utilizzati Per Il Restauro di Beni Policromi Mobili (2008).

Ebnesajjad, S. 8—Characteristics of adhesive materials. In Handbook of Adhesives and Surface Preparation (ed. Ebnesajjad, S.) 137–183 (William Andrew Publishing, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4377-4461-3.10008-2.

Raimundo, M. Monograph Animal Glues: A Review of Their Key Properties Relevant to Conservation.

Shields, J. Adhesives Handbook (Elsevier, 2013).

Fay, P. A. 1—A history of adhesive bonding. in Adhesive Bonding (Second Edition) (ed. Adams, R. D.) 3–40 (Woodhead Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819954-1.00017-4

Duconseille, A., Astruc, T., Quintana, N., Meersman, F. & Sante-Lhoutellier, V. Gelatin structure and composition linked to hard capsule dissolution: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 43, 360–376 (2015).

Taheri, A., Abedian Kenari, A. M., Gildberg, A. & Behnam, S. Extraction and physicochemical characterization of greater lizardfish (Saurida tumbil) skin and bone gelatin. J. Food Sci. 74, E160–E165 (2009).

Elharfaoui, N., Djabourov, M. & Babel, W. Molecular weight influence on gelatin gels: Structure, enthalpy and rheology. Macromol. Sympos. 256, 149–157 (2007).

Guo, L., Colby, R. H., Lusignan, C. P. & Whitesides, T. H. Kinetics of triple helix formation in semidilute gelatin solutions. Macromolecules 36, 9999–10008 (2003).

Gómez-Guillén, M. C. et al. Structural and physical properties of gelatin extracted from different marine species: A comparative study. Food Hydrocoll. 16, 25–34 (2002).

Kozlov, P. V. & Burdygina, G. I. The structure and properties of solid gelatin and the principles of their modification. Polymer 24, 651–666 (1983).

Bigi, A., Panzavolta, S. & Rubini, K. Relationship between triple-helix content and mechanical properties of gelatin films. Biomaterials 25, 5675–5680 (2004).

Mosleh, Y. et al. The structure–property correlations in dry gelatin adhesive films. Adv. Eng. Mater. 23, 2000716 (2021).

Bigi, A., Cojazzi, G., Panzavolta, S., Rubini, K. & Roveri, N. Mechanical and thermal properties of gelatin films at different degrees of glutaraldehyde crosslinking. Biomaterials 22, 763–768 (2001).

Obas, F.-L., Thomas, L. C., Terban, M. W. & Schmidt, S. J. Characterization of the thermal behavior and structural properties of a commercial high-solids confectionary gel made with gelatin. Food Hydrocoll. 148, 109432 (2024).

Dai, C.-A., Chen, Y.-F. & Liu, M.-W. Thermal properties measurements of renatured gelatin using conventional and temperature modulated differential scanning calorimetry. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 99, 1795–1801 (2006).

Aguirre-Alvarez, G., Pimentel-González, D. J., Campos-Montiel, R. G., Foster, T. & Hill, S. E. The effect of drying temperature on mechanical properties of pig skin gelatin films El efecto de la temperatura de secado sobre las propiedades mecánicas de películas de gelatina de cerdo. CyTA J. Food 9, 243–249 (2011).

Mosleh, Y. et al. Hygrothermal ageing of dry gelatine adhesive films: Microstructure–property relationships. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 131, 103654 (2024).

Rahman, M. S., Al-Saidi, G., Guizani, N. & Abdullah, A. Development of state diagram of bovine gelatin by measuring thermal characteristics using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and cooling curve method. Thermochim. Acta 509, 111–119 (2010).

Achet, D. & He, X. W. Determination of the renaturation level in gelatin films. Polymer 36, 787–791 (1995).

Htut, K. Z. et al. Correlation between protein secondary structure and mechanical performance for the ultra-tough dragline silk of Darwin’s bark spider. J. Roy. Soc. Interface 18, 20210320 (2021).

Pulidori, E. et al. Analysis of gelatin secondary structure in gelatin/keratin-based biomaterials. J. Mol. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.134984 (2023).

Hutchinson, J. M. Physical aging of polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 20, 703–760 (1995).

Ferrari, C. & Johari, G. P. Thermodynamic behaviour of gliadins mixture and the glass-softening transition of its dried state. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 21, 231–241 (1997).

White, J. R. Polymer ageing: Physics, chemistry or engineering? Time to reflect. C. R. Chim. 9, 1396–1408 (2006).

Johari, G. P. Localized motions and the loss of chemical and physical metastabilities during ageing of amorphous polymers studied by dielectric measurements. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 93, 2303–2308 (1997).

Righetti, M. C. & Johari, G. P. Enthalpy and entropy changes during physical ageing of 20% polystyrene–80% poly(α-methylstyrene) blend and the cooling rate effects. Thermochim. Acta 607, 19–29 (2015).

Johari, G. P. Decrease of heat capacity on aging, long and linear extrapolations for fictive temperature, and the case of 20-million-year-old fossil-amber. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 611, 122301 (2023).

Pelosi, C., Tombari, E., Wurm, F. R. & Tiné, M. R. Unfreezing of molecular motions in protein-polymer conjugates: A calorimetric study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 147, 12631–12639 (2022).

Chung, H.-J., Yoo, B. & Lim, S.-T. Effects of physical aging on thermal and mechanical properties of glassy normal corn starch. Starch Stärke 57, 354–362 (2005).

Noel, T. R. et al. Physical aging of starch, maltodextrin, and maltose. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 8580–8585 (2005).

Farahnaky, A., Badii, F., Farhat, I. A., Mitchell, J. R. & Hill, S. E. Enthalpy relaxation of bovine serum albumin and implications for its storage in the glassy state. Biopolymers 78, 69–77 (2005).

Farahnaky, A. & Majzoobi, M. An investigation on physical ageing of lactoglobulin and implications for its storage. Int. J. Food Eng. 8, 1–9 (2012).

Struik, L. C. E. & Pezzin, G. Physical aging of dry elastin. Biopolymers 19, 1667–1673 (1980).

Sartor, G. & Johari, G. P. Polymerization of a vegetable protein, wheat gluten, and the glass-softening transition of its dry and reacted state. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 19692–19701 (1996).

Mo, X. & Sun, X. Effects of storage time on properties of soybean protein-based plastics. J. Polym. Environ. 11, 15–22 (2003).

Tan, W., Na, J. & Zhou, Z. Effect of service temperature on mechanical properties of adhesive joints after hygrothermal aging. Polymers 13, 3741 (2021).

Zhou, S., Fang, X., He, Y. & Hu, H. Towards a deeper understanding of creep and physical aging behavior of the emulsion polymer isocyanate. Polymers 12, 1425 (2020).

Dobilaitė, V. et al. Effect of artificial aging of peel adhesion of self-adhesive tapes on different construction surfaces. Appl. Sci. 13, 8947 (2023).

Enrione, J. I. et al. Structural relaxation of salmon gelatin films in the glassy state. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 5, 2446–2453 (2012).

Liu, J. et al. Enhancement of the hygrothermal ageing properties of gelatine films by ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether. Herit. Sci. 12, 297 (2024).

Ntasi, G. et al. Proteomic characterization of collagen-based animal glues for restoration. J. Proteome Res. 21, 2173–2184 (2022).

Cennini, C. & Frezzato, F. Il libro dell’arte. (Neri Pozza, 2009).

Bhat, R. & Karim, A. A. Ultraviolet irradiation improves gel strength of fish gelatin. Food Chem. 113, 1160–1164 (2009).

Wainewright, F. W. Physical tests for gelatin and gelatin products. in The Science and Technology of Gelatin 507–531 (Academic Press, 1977).

Bramanti, E., Bramanti, M., Stiavetti, P. & Benedetti, E. A frequency deconvolution procedure using a conjugate gradient minimization method with suitable constraints. J. Chemom. 8, 409–421 (1994).

Bramanti, E. & Benedetti, E. Determination of the secondary structure of isomeric forms of human serum albumin by a particular frequency deconvolution procedure applied to Fourier transform IR analysis. Biopolymers 38, 639–653 (1996).

Bramanti, E., Ferrari, C., Angeli, V., Onor, M. & Synovec, R. E. Characterization of BSA unfolding and aggregation using a single-capillary viscometer and dynamic surface tension detector. Talanta 85, 2553–2561 (2011).

Chirgadze, Yu. N., Fedorov, O. V. & Trushina, N. P. Estimation of amino acid residue side-chain absorption in the infrared spectra of protein solutions in heavy water. Biopolymers 14, 679–694 (1975).

Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 1073–1101 (2007).

Orsini, S., Parlanti, F. & Bonaduce, I. Analytical pyrolysis of proteins in samples from artistic and archaeological objects. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 124, 643–657 (2017).

Orsini, S., Duce, C. & Bonaduce, I. Analytical pyrolysis of ovalbumin. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 130, 62–71 (2018).

Bozec, L. & Odlyha, M. Thermal denaturation studies of collagen by microthermal analysis and atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 101, 228–236 (2011).

Lim, J. J. Thermogravimetric analysis of human femur bone. J. Biol. Phys. 3, 111–129 (1975).

Tomaselli, V. P. & Shamos, M. H. Electrical properties of hydrated collagen. I. Dielectric properties. Biopolymers 12, 353–366 (1973).

Sebestyén, Z. et al. Characterization of historical leather bookbindings by various thermal methods (TG/MS, Py-GC/MS, and micro-DSC) and FTIR-ATR spectroscopy. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 162, 105428 (2022).

Carsote, C. & Badea, E. Micro differential scanning calorimetry and micro hot table method for quantifying deterioration of historical leather. Herit. Sci. 7, 48 (2019).

Bañón, E., García, A. N. & Marcilla, A. Thermogravimetric analysis and Py-GC/MS for discrimination of leather from different animal species and tanning processes. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 159, 105244 (2021).

Alipal, J. et al. A review of gelatin: Properties, sources, process, applications, and commercialisation. Mater. Today Proc. 42, 240–250 (2021).

Fessas, D. et al. Thermal analysis on parchments I: DSC and TGA combined approach for heat damage assessment. Thermochim. Acta 447, 30–35 (2006).

Del Campo, F. F., Paneque, A., Ramirez, J. M. & Losada, M. Thermal transitions in collagen. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 66, 448–452 (1963).

Flory, P. J. & Garrett, R. R. Phase transitions in collagen and gelatin systems 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 4836–4845 (1958).

Shoulders, M. D. & Raines, R. T. Collagen structure and stability. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 929–958 (2009).

Díaz-Calderón, P., MacNaughtan, B., Hill, S., Mitchell, J. & Enrione, J. Reduction of enthalpy relaxation in gelatine films by addition of polyols. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 109, 634–638 (2018).

Bier, J. M., Verbeek, C. J. R. & Lay, M. C. Thermal transitions and structural relaxations in protein-based thermoplastics. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 299, 524–539 (2014).

Sydykov, B., Oldenhof, H., Sieme, H. & Wolkers, W. F. Hydrogen bonding interactions and enthalpy relaxation in sugar/protein glasses. J. Pharm. Sci. 106, 761–769 (2017).

Ringe, D. & Petsko, G. A. The ‘glass transition’ in protein dynamics: What it is, why it occurs, and how to exploit it. Biophys. Chem. 105, 667–680 (2003).

Tseretely, G. I. & Smirnova, O. I. DSC study of melting and glass transition in gelatins. J. Therm. Anal. 38, 1189–1201 (1992).

Wang, Z., Zhao, S., Song, R., Zhang, W. Z. S. & Li, J. The synergy between natural polyphenol-inspired catechol moieties and plant protein-derived bio-adhesive enhances the wet bonding strength. Sci. Rep. 7, 9664 (2017).

Fevzioglu, M., Ozturk, O. K., Hamaker, B. R. & Campanella, O. H. Quantitative approach to study secondary structure of proteins by FT-IR spectroscopy, using a model wheat gluten system. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 164, 2753–2760 (2020).

Sochava, I. V. & Smirnova, O. I. Heat capacity of hydrated and dehydrated globular proteins. The denaturing increment of heat capacity. Mol. Biol. (Mosk) 27, 348–357 (1993).

Saiani, A. et al. Self-assembly and gelation properties of α-helix versus β-sheet forming peptides. Soft Matter 5, 193–202 (2009).

Cohen, N. & Eisenbach, C. D. Molecular mechanics of beta-sheets. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 6(4), 1940–1949 (2020).

Ghosh, P., Katti, D. R. & Katti, K. S. Impact of β-sheet conformations on the mechanical response of protein in biocomposites. Mater. Manuf. Process. 21(7), 676–682 (2006).

Feng, Z., Xia, F. & Jiang, Z. The effect of β-sheet secondary structure on all-β proteins by molecular dynamics simulations. Molecules 29, 2967 (2024).

Xiao, S., Xiao, S. & Gräter, F. Dissecting the structural determinants for the difference in mechanical stability of silk and amyloid beta-sheet stacks. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 8765–8771 (2013).

Johari, N. et al. Ancient fibrous biomaterials from silkworm protein fibroin and spider silk blends: Biomechanical patterns. Acta Biomater. 153, 38–67 (2022).

Weiwen, D. et al. Changes in advanced protein structure during dense phase carbon dioxide induced gel formation in golden pompano surimi correlate with gel strength. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7, 1189149 (2023).

Duconseille, A. et al. The effect of origin of the gelatine and ageing on the secondary structure and water dissolution. Food Hydrocoll. 66, 378–388 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Museo Nacional del Prado (Madrid) and restoration workshop of the University Suor Orsola Benincasa (Naples) are acknowledged for providing the animal glues samples. We would like to thank Prof. Cristian Biagioni of the Department of Pharmacy at the University of Pisa for his support with XRD analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by MUR project PRIN 2022 PNRR ArtDECOW (project code P2022HWL7L). The project is financed by European Union-Next Generation EU, Mission 2, Component 1 (M2C1) CUP: I53D23005990001.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.P., C.D. and E.B. conceptualization; E.P. investigation; E.P., G.T., L.C. data curation; E.P. Writing—Original Draft; C.D., E.B., L.B., B.C., L. D. I., G.T., L.C. and I.L. Writing—Review & Editing; C.D., E.B., and I.B Supervision; C.D., E.B., L.B, and I.B. Funding acquisition; L.B and L. D. I., Resources.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pulidori, E., Duce, C., Bramanti, E. et al. Characterization of the secondary structure, renaturation and physical ageing of gelatine adhesives. Sci Rep 15, 23022 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04910-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04910-8