Abstract

Nested named entity recognition (NNER), a subtask of named entity recognition (NER), aims to recognize more types of entities and complex nested relationships, presenting challenges for real-world applications. Traditional methods, such as sequence labeling, struggle with the task because of the hierarchical nature of these relationships. Although NNER methods have been extensively studied in various languages, research on Chinese NNER (CNNER) remains limited, despite the complexity added by ambiguous word boundaries and flexible word usage in Chinese. This paper proposes a multi-scale transformer prototype network (MSTPN)-based CNNER method. Multi-scale bounding boxes for entities are deployed to identify nested named entities, transforming the recognition of complex hierarchical entity relationships into a more straightforward task of multi-scale entity bounding box recognition. To improve the accuracy of multi-scale entity bounding box recognition, MSTPN, leverages the sequence feature extraction capabilities of transformers and utilizes the advantages of prototype networks in few-shot and multiple-category tasks. A distance-based multi-bounding box cross-entropy loss method is introduced to optimize MSTPN, ensuring the coordinated optimization of transformer and prototype parameters. Experiments using the ACE05, ChiNesE, and RENMIN datasets demonstrate that MSTPN outperforms state-of-the-art methods, highlighting the effectiveness of prototype networks in natural language processing tasks involving long sequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

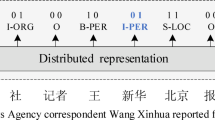

Named entity recognition (NER) is a fundamental task1 in natural language processing (NLP) that identifies entities in unstructured text. It is categorized into flatten NER, which deals with discrete, non-overlapping entities2, and nested NER (NNER), which identifies overlapping entities by capturing multilevel relationships . Flatten NER typically involves limited data types and simpler structures, while NNER handles nested entities3, thereby enabling the identification of a larger range of labels and entities. Its complexity is because of multilevel entity relationships and the diversity of entity label types, which has attracted increasing research interest in this area. Figure 1 shows examples of nested NER using this concept.

NNER has been applied in fields such as journalism4, biology5, and law6, primarily using English datasets. However, research on Chinese NNER (CNNER)7 remains limited. Unlike English, where words are separated by spaces, Chinese lacks clear word delimiters, increasing the complexity of entity representation and the difficulty tasks. The most commonly used methods for NNER can be broadly divided into two categories: sequence-labeling-based8 and span-based9,10 methods.

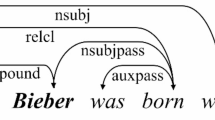

(1) Sequence-Labeling Methods: These approaches define additional labels for nested entities and employ classification models (e.g., TextCNN11, Bi-LSTM12, or BERT13) to assign labels to tokens, which are then parsed to identify entities in the sentence. This class of methods deals with continuous sequences, which makes it difficult to obtain the relationship between different levels of sequences, resulting in inaccurate results for nested entity recognition.

(2) Span-Based Methods14,15: A span text box is created from the input text to represent potential entities, and a classifier is then used to categorize the spans, eliminate non-entity spans, and identify the entity categories of valid spans. While effective for simple nested entities, it suffers from issues such as low accuracy in entity boundary identification and inaccurate span recognition due to its neglect of explicit boundary information and the correlation between entity types and entity spans during span classification. Additionally, such methods generally require an enumeration analysis of spans, leading to a high computational complexity for the model.

To address the above issues, in order to comprehensively consider the correlation between Span regions and entity type features, and further reduce the complexity of model computation. Researchers have drawn inspiration from object detection16,17,18 to recognize nested entities by treating them as nested targets and designing entity recognition methods based on text bounding box predictions. Xu19 proposed a method that simultaneously identifies entity positions and categories, leverages multi-head self-attention to detect entity types, and integrates semantic information of varying granularities to improve bounding box recognition accuracy. This method is based on neural network inference, capable of simultaneously predicting entity scopes and types across multiple scales, enhancing accuracy while reducing the computational complexity of the model. It employs a regression model for entity scope identification and utilizes a general recognition model for entity classification. However, issues such as a wide margin of error and inaccurate entity type recognition in cases of uneven sample distribution exist. Entity recognition tasks demand a higher level of accuracy for delineating entity boundaries in comparison to image recognition, with a narrower margin of error being permitted. Consequently, errors in entity boundary recognition have a substantial impact on the performance of this method.

To enhance the accuracy of entity scope identification and fully leverage the associative relationship between entity boundaries and entity types, we utilize more definitive one-hot vectors to achieve accurate identification of entity regions and employ a prototype network for the recognition of entity types. The prototype networks20,21 is capable of enhancing the recognition efficacy of classification tasks under conditions of uneven sample distribution with only a slight increase in computational complexity. Additionally, it exhibits strong performance in few-shot classification tasks22, allowing this methodology to concurrently elevate the accuracy of entity boundary recognition and the precision of entity type identification.

This study focuses on accurately and efficiently identifying element entities within long Chinese text sequences under a multilabel hierarchy and uneven data distribution. We propose a Multi-Scale Transformer Prototype Network (MSTPN)-based CNNER method. First, entity bounding boxes are designed to represent different entities, transforming the CNNER task into a multi-scale entity bounding box recognition task and exploring the practicability of entity recognition based on bounding box detection. To address the challenges of multilabel hierarchies and uneven sample distributions in entity bounding box recognition, we use prototype networks and design a CNNER method based on the MSTPN. Furthermore, we propose a loss function for the joint optimization of backbone networks and prototypes that facilitates the optimization of multi-scale prototype networks. We also experimentally validate the effectiveness of the prototype networks in transformer-based recognition methods. The main contributions of this study are as follows.

1) We propose a novel method for MSTPN-based CNNER. This is the first time that a multi-scale entity bounding box has been proposed and that a multi-scale transformer prototype network has been implemented to accurately and efficiently recognize Chinese nested named entities under multiple categories and uneven sample distribution conditions.

2) We have designed a distance-based multi-bounding box cross-entropy loss (DMCE) function that defines the loss for NER based on entity bounding boxes, supports the joint optimization of transformer networks and prototype parameters, and thereby achieves the fast and effective convergence of MSTPN parameters.

3) The experimental results on three publicly available datasets (ACE05, ChiNesE, and RENMIN) show that the proposed method achieves the best results in the CNNER task, with an average improvement of 0.22% over the second-best method.

Related work

This section introduces related works by dividing them into three categories: Nested NER, Chinese Nested NER, and Prototype Networks.

Nested named entity recognition (NNER). NNER is a branch of NER in which entities can be nested within each other7. Early approaches were primarily rule-based23,24, such as defining entity recognition rules25 or using hidden Markov models-based NER models. With the advent of deep learning in NLP and its significant potential, more advanced methods emerged: (1) Hierarchical methods26,27, such as Wang28 ’s use of multiple label layers to recognize entities at different nesting depths. (2) Region-based methods29, such as the biaffine30 nested NER approach, which predicts multiple start/end coordinates to extract named entities. (3) Graph-based methods31, which leverage hypergraph frameworks to represent nested entity structures, in which edges represent different entities and nodes and edges are identified separately. (4) Sequence parsing methods32, which use letter stacks, buffers, and transition matrices to extract nested named entities. While these existing NER methods are primarily optimized for English, they are not directly applicable to Chinese tasks. In particular, they lack support for Chinese-specific entity label categories and hierarchies, making them ill-suited for CNNER.

Chinese nested NER. Few studies focus on CNER. Fu33 addressed this task as a hierarchical grouping problem for character sequences and proposed a two-layer conditional random field-based entity recognition method. However, this method is limited to recognizing nesting depths greater than two. Chen34 combined neural networks with hierarchical entity-recognition architectures, first detecting different entity boundaries and combining them to form entity candidates, which are then filtered using neural networks. Yang35 proposed lexicon-aware character representations, integrating word-level knowledge, and implemented entity recognition using transformers and biaffines. Yang36 introduced an entity recognition method based on bounding boxes of varying scales, designed to identify nested entities at different positions and scales. Additionally, more CNNER datasets36,37 were constructed to further advance research on CNNER tasks. These approaches directly leverage neural networks for feature extraction models and use fully connected networks for entity classification. However, they tend to overfit under few-shot conditions and exhibit relatively poor performance in multilabel recognition tasks.

Prototype model. Also known as learning vector quantization (LVQ)38, prototype modeling is derived from K-nearest neighbors or 1-nearest neighbors and is primarily used for classification tasks. It retains multiple learnable class prototypes for each input class. Initially, researchers focused on designing of optimization rules during the training process. Recently, however, prototype optimization has been approached as a holistic algorithm optimization problem. Different optimization loss functions were designed to jointly optimize parameters in deep models and prototypes, achieving optimal overall performance. Liu39 summarized early prototype optimization methods, which relied heavily on manually designed rules for feature extraction and learning algorithms. These methods have highlighted the need for researchers to carefully align features and optimization strategies. The compatibility between extracted features and optimization strategies is crucial for achieving optimal effectiveness. Without this alignment, end-to-end optimized neural network models may not yield the desired results. Increasingly, researchers are exploring end-to-end optimization methods to enhance performance. For example, Snell22 proposed a small-sample learning algorithm that integrates a CNN with prototype network distance metrics. In this approach, prototype and model optimizations are treated independently. Yang35 constructed a convolutional prototype network and designed a distance-based cross-entropy loss as well as a one-versus-all loss to optimize the CNN and prototype parameters simultaneously, demonstrating the method’s efficacy in few-shot tasks on open datasets. Feng40 combined the principles of prototypes and ontologies to represent entity categories under few-sample conditions, applying these concepts to few-sample NER tasks. However, existing prototype networks have been predominantly designed for classification tasks in the image domain and have yet to be systematically extended to NLP tasks.

Methods

In this study, we propose a transformer-based prototype network (MSTPN) for the CNNER method that utilizes entity bounding boxes to identify nested named entities, where each entity bounding box consists of an entity category label and length. All entities in the input sentence can be detected by predicting multi-scale entity bounding boxes at different text positions. The DMCE was applied to optimize the MSTPN. Figure 2 shows an overview of the proposed MSTPN.

As shown in Fig. 2, we first used a transformer41,42 network to obtain the embedding vectors for all characters in each given input sentence. These character embeddings are processed through a Bi-LSTM network, followed by fully connected layers, resulting in character representation vectors. The distances between the representation vector and the different prototypes were calculated, and the prototype category corresponding to the closest distance was assigned as the entity category. The representation vector simultaneously predicted the entity length, and the named entity by combining the predicted entity category and length. However, each entity bounding box can only correspond to one entity category and one entity length, and it cannot recognize nested entities. Inspired by Mulco36 and based on analyses of sample data, we designed prototype category labels of different scales to recognize multi-scale nested named entities. Multi-scale entity bounding boxes are composed of multiple single-scale object bounding boxes BBox_i. Each BBox_i detects the location and category information of named entities at a specific scale. Multiple BBox_i with different scales(small scale, large scale) and positions (starts at i, ends at i) are designed to achieve multi-scale named entity detection. The detection method for each BBox_i is delineated in Fig. 3.

Recognizing named entities with single entity bounding boxes

The NNER task aims to identify all entities in a given sentence that have certain containment relationships. Inspired by the integrated approach of target detection and recognition in computer vision, we developed entity bounding boxes to represent the positional information of entities in the sentence. Each entity bounding box contains the entity’s starting position, entity length, and category information, represented by a triplet \(\left( {e,l,c} \right)\). The notation represents a single entity bounding box with i as the starting point. For the input text “I love Beijing Tiananmen Square”, \({d_{s\_3}}\) represents the entity starting with “Beijing”, \({d_{s\_4}}\) represents the entity starting with “Tiananmen”, the entity “Beijing” has a length of 1 and belongs to the Location category, so the triplet for the entity bounding box corresponding to \({d_{s\_3}}\) is \(\left( {3,1,LOC} \right)\), and the triplet for the entity “Tiananmen Square” is \(\left( {4,2,GPE} \right)\).

This approach treats each input token as a detecting grid and predicts the entity bounding box corresponding to the current token, the details are illustrated in Fig. 3. In Chinese, the i th character in the input text sentence \(T = {\{ {w_i}\} _{1 \le i \le N}}\) is represented by \({w_i}\), where N is the length of the sentence. For each character \({w_i}\) in the sentence, a bounding box \(\left( {e,l,c} \right)\) is predicted with it as the boundary. The entity bounding box includes the entity’s starting position(e), length(l), and category(c). The coordinates of the current token are typically directly taken as the values of e in the entity bounding box, with l and c taking the following values:

When \({w_i}\) is the boundary of an entity, its corresponding entity bounding box length l takes the value of the entity’s length, and its category corresponds to the entity’s category. Otherwise, the length l of the entity bounding box is set to 0 and the category is None.

Multi-scale transformer-based prototype network for CNNER

As previously mentioned, identifying a single-entity bounding box involves recognizing the entity category and its length. The natural approach for predicting entity length is length regression, which is widely used in computer vision tasks16,18. However, given that NER tasks require zero error tolerance for entity length, regression can lead to significant errors. To address this, a one-hot vector technique was employed to represent the entity length, transforming the original length regression problem into a classification problem.

To accurately predict entity types, it is essential to leverage the contextual semantic information of the text. Prototype networks have demonstrated remarkable performance in image classification tasks20. However, the application of prototype networks in NLP tasks has been limited because of the need to process individual words in a sentence. We propose a method based on a transformer prototype network for entity recognition that uses bounding boxes to identify named entities.The method uses a Transformer-like model to encode the text sequence and a Bi-LSTM model to capture contextual information. The hidden vector \({h_i}\) is obtained by fully connected layers with dimensions consistent with the prototype vector. The distances between the hidden vector and different prototype vectors \({m_{jk}}\) are calculated, resulting in the distance \(d\left( {{h_i},{m_{jk}}} \right)\) between the hidden vector and the prototype. Finally, we compute the mean distance of the hidden vector for the various prototype distances. This approach shows promising results in terms of improving the accuracy of entity recognition in NLP:

The category of entity bounding boxes corresponding to the implicit vector \({h_i}\) is:

In this equation, where j represents different prototype categories, k represents different prototypes under the same category of prototypes, and d represents the distance function between the two vectors, which can be cosine distance.

The Flat NER task requires predicting a single entity bounding box for each character, which is adequate to cover all entity box types. However, this is insufficient for nested named entity tasks, such as “Haidian district of Beijing”, where “Bei” corresponds to “Beijing,LOC” and “Haidian district of Beijing,LOC”. Using a single entity bounding box is no longer sufficient to meet the entity recognition requirements for such tasks. Inspired by Mulco’s36 framework, we designed a strategy that utilizes four different entity bounding boxes to identify the smallest and largest scale bounding boxes starting at \({w_i}\), along with the smallest and largest scale bounding boxes ending at \({w_i}\). Four distinct-scale entity bounding boxes (\(b_i^{B - Max}\), \(b_i^{B - Min}\), \(b_i^{E - Max}\), \(b_i^{E - Min}\)) are predicted for each character in the input sentence, yielding all the predicted entity bounding boxes of the input sentence. To obtain all entity predictions for the entire sentence, merging and deduplicating the predictions for all characters is essential.

Distance-based multi-boundingbox cross entropy loss (DMCE)

A distance-based cross entropy loss function is designed to optimize the training of a multi-scale transformer-based prototype network. For an input text sentence \(T = {\{ {w_i}\} _{1 \le i \le N}}\), the encoding representation of each character is extracted from a Transformer-based pre-trained model.

In sentence T, Erepresents the sequence of character encodings, where each \(e_i\) represents the encoding of the i th character, \({e_i} \in {\mathbb {R}^d}\). The dimension of the embedding vector is d, \(Transformer\left( \cdot \right)\) defines the function that uses a transformer-based model to extract the embedding vectors of the input sentence.

Although the encodings obtained from the transformer-based model contain some contextual semantic information, they can be made more efficient. In order to obtain character embedding vectors with more contextual information, the encoding obtained from the transformer is fed into a Bi-LSTM model to extract additional contextual semantic information and then mapped to a hidden vector through a fully connected layer:

Where, \({h_i}\) represents the hidden vector corresponding to the i th character, \({h_i} \in {\mathbb {R}^m}\), where m is the dimension of the contextual semantic embedding vector, \(BiLSTM\left( \cdot \right)\) extracts contextual semantic vectors, and \(FC\left( \cdot \right)\) maps the embedding vectors to the m-dimensional space.

After obtaining the contextual embedding vectors, we used fully connected layers and a prototype network based on the cosine distance to predict the four-scale bounding boxes and infer the length and category information of the entity bounding box. Taking B-max as an example, the length of the entity bounding box is calculated as follows:

\(l_i^{B - \max }\) corresponds to the one-hot length vector of the longest entity starting from \({w_i}\), \(l_i^{B - \max } \in {\mathbb {R}^{{N_l}}}\). \(W_L^{B - \max } \in {\mathbb {R}^{m \times {N_l}}}\), \(b_L^{B - \max } \in {\mathbb {R}^{{N_l}}}\) are trainable parameters of the B-Max length prediction classifier.

The category of entity bounding boxes is calculating by first computing the probability that each textual implicit vector \({h_i}\) belongs to some prototype \({m_{jk}}\):

Where \(d\left( \cdot \right)\) represents the distance function that calculates the distance between different vectors, and \(\gamma\) is a constant, the probability that the entity belongs to the category is calculated as:

The loss of the entity bounding box is:

The overall loss of the input is:

Where \({\mathscr {L}}_i^{B - \min }\), \({\mathscr {L}}_i^{E - \max }\) and \({\mathscr {L}}_i^{E - \min }\) correspond to the losses of the other three entity bounding boxes, respectively.

In this loss function, the prototype network loss extends the DCE loss when applying transformer-based models. The formula demonstrates that optimizing the classification loss function will minimize the distance between the model’s predicted outputs and the corresponding prototypes. This loss function can simultaneously optimize all associated prototypes and the model.This contrasts with optimization methods such as MCE and MCL20, which optimize one prototype at a time, thereby accelerating the convergence of the algorithm. Unlike classification tasks in computer vision, we decompose the loss of the entire text sentence into the loss of each character concerning the prototypes and then obtain the loss of the whole sentence by summing or averaging. Experiments were conducted to validate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed method.

Experiments

Datasets

This algorithm is primarily used for CNNER. To evaluate its effectiveness, we used three datasets: ACE200543, ChiNesE36, and the People’s Daily44(also known as RENMIN). ACE2005 is a multilingual dataset collected from various sources, including broadcasts, newswires, and weblogs, and it comprises English, Arabic, and Chinese data. Among the labels, “Person” boasts the highest sample count, with 14,539 instances, whereas “Weapon” exhibits the lowest, with only 374 instances. This is currently the most widely used dataset for NNER. Following Lu’s work45, we set the ratio of the training, validation, and test data to 8:1:1. The ChiNesE dataset, constructed from Chinese Wikipedia data, is better suited for CNNER tasks, and the division of the training, validation, and testing datasets was determined by the original dataset partitioning. The label with the largest number of samples is “Person,” comprising 20,510 entries, whereas the label with the smallest number of samples is “Organisms,” consisting of 3,326 entries. The People’s Daily dataset includes both non-nested and nested NER. The maximum number of samples in the dataset tested above is 5-40 times the minimum number of samples, which can effectively validate the model performance under the condition of uneven sample distribution. The details of the dataset analysis are presented in Table 1:

Experimental setting

Transformer-based models, such as BERT13, RoBERTa46, LongFormer47, and RoFormer48 are commonly used in Chinese text processing because of their effectiveness. Concerning the selection of the transformer model, a series of experiments were conducted using the aforementioned transformers on different data sets. Subsequently, the model demonstrating the optimal performance was selected as the encoder. Subsequently, a Bi-LSTM model was used to capture additional contextual information, followed by a fully connected layer to get the hidden vector. The dimension of the prototype vector is denoted as \({N_c} \times {N_P} \times 768\), where \({N_c}\) represents the number of prototype categories and \({N_P}\) represents the number of prototypes in each category. The cosine distance function is chosen as the distance function between vectors and prototypes, maintaining a consistent distance interpretation, defined as \(d\left( {x,y} \right) = 1 - \lambda \cos \left( {x,y} \right)\). Experiments were conducted on the ACE2005, ChiNesE, and People’s Daily datasets. The main parameters are set as follows in the table 2:

Experimental results & analysis

We evaluate the algorithm’s effectiveness using three indicators: accuracy, recall, and F1 value. The experimental results are shown in the table 3. From Table 3 , it can be seen that the proposed MSTPN achieved the highest F1, which can effectively improve the recognition of Chinese nested ners. This is because the proposed MSTPN is dedicated to improving the recognition ability of nested named entities.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed MSTPN, we evaluate the statistical significance of the performance improvement. We assembled and obtained the full set of training, validation, and test data from the ACE2005-ch, ChiNesE, and People’s Daily datasets, respectively, and randomly divided them into training and test sets in the ratio of 4:1. We conducted five random experiments, and the results are shown in Table 4. A paired samples t-test was then used for significance analysis. We analysed the significance between the proposed MSTPN and the mAP means of Mulco using the experimental data in Table 4. The detailed significance analysis is presented in Table 5. As can be seen from Table 5, the performance improvement of the proposed MSTPN is statistically significant (p < 0.05) compared to other attention models. The evaluation results show that MSTPN has significant advantages over other methods.

Effect of different distance functions and pre-trained models

To assess the impacts of different base models and strategies on the experimental results, we conducted ablation experiments on different datasets. Table 6 lists the final experimental results. These results indicate that the BERT and RoBERTa pretrained models achieved the highest performance across both tasks. Furthermore, the integration of LSTM and fully connected networks resulted in an accuracy improvement of 1 to 2 percentage points.

To verify the reliability of the experimental results presented in Table 6, we assessed the statistical significance of the performance improvement. We chose a more representative dataset ChiNesE, and randomly divided it into a training set and a test set in a ratio of 4:1. Subsequently, we performed five independent random experiments, with the outcomes summarized in Table 7. Following this, we applied a paired-sample t-test to evaluate the significance of the differences in F1 scores between our proposed model and the Mulco model across the above three datasets. The detailed significance analysis is provided in Table 8. As evident from Table 8, the mean F1 scores achieved by our model on these three datasets consistently surpass those of the Mulco model. P are less than 0.05, which indicates that the differences in mean F1 scores between our model and the Mulco model across the three datasets are statistically significant. These evaluation results demonstrate that, compared to Mulco, the proposed model exhibits a marked advantage in Chinese nested named entity recognition.

Effect of prototype number K

To further investigate the effect of the number of prototypes in each class on model accuracy within the prototype network, we conducted a controlled experiment with the same base network while varying the test datasets and number of prototypes. Figure 4 shows the results of these experiments.

The results show that increasing the number of prototypes does not necessarily improve the model performance and may even lead to a decline in the final experimental results. Considering that transformer-based models are effective at encoding text and capturing contextual semantic features after passing through a bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) network, increasing the number of prototypes may result in overfitting and reduced performance.

Analysis of model computation efficiency

In this section, we investigate the computational complexity of the model using the ChiNesE dataset as an example and trained the model using MSTPN, Mulco. The computational efficiency of the model is compared with related work, as shown in Table 9.

As can be seen from Table 9, compared to Biaffine which recognises entities at different scales by setting up bi-affine matrices, our model has an extra BiLSTM module and a prototype network module, increasing the number of parameters slightly. Compared with Mulco, MSTPN replaces the original multiple fully-connected layers with prototype network, which reduces the number of parameters, but increases a part of the computation as MSTPN needs to compute the distances between vector representations and different prototypes during the inference process, but this part of the computational complexity is certain, and the overall computational complexity is controllable. These results show that our model is competitive in terms of computational efficiency.

Case study

To further demonstrate the performance of MSTPN, a case study was conducted on the ChiNesE dataset. Figure 5 illustrates two real-case predictions made by MSTPN. As illustrated in panel (a), each entity detection box is designed to detect a distinct set of entities. However, none of these boxes are capable of detecting all possible entities. However, by synthesising the results from all entity detection boxes, all named entities with complex nested structures can be obtained. Furthermore, the results obtained from different detection boxes can corroborate and complement each other. For instance, the recognition results of E-Min and E-Max are consistent with the B-Max detection box for “Yanwo Town Middle School” and “Lijin County Yanwo Town Middle School”, respectively. In panel (b), the named entity “Swan” was not correctly identified. This may be because “swan” itself represents an animal, but in this sentence, it serves as a modifier for an event, and its contextual semantics differ significantly from the common semantics of animals. Additionally, E-Max made an erroneous prediction, identifying “China Swan Poetry Award” as the longest named entity ending with “award”. In instances where three or more entity detection boxes are associated with the same token, errors may occur in predicting the longest or shortest entity. However, as MSTPN comprises four scopes, such errors in a single scope may not lead to overall erroneous predictions for named entities, as they can be recognized by multiple scopes.

Discussion

This paper proposes a novel multi-scale transformer-based prototype network (MSTPN) method for CNNER. The main contributions include the use of entity bounding boxes for NER, application of a multi-scale transformer-based prototype network for entity bounding box recognition, formulation of a loss function, and successful application to CNNER tasks. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a prototype network has been applied to NNER tasks, demonstrating the potential of prototype networks in NLP applications. To implement the MSTPN, entity bounding boxes were innovatively designed to represent named entities, and multi-scale entity bounding boxes were constructed to identify named entities of different hierarchies and categories, inspired by object recognition techniques. Furthermore, a DMCE loss function was employed to simultaneously optimize the neural networks and model parameters, showcasing the effectiveness of prototype networks in long-sequence recognition tasks. The experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed MSTPN framework, which can support diverse pretrained models and varying numbers of prototypes. Moreover, the results suggest that this framework can be applied to a broader range of natural language processing tasks, such as text classification, relation extraction, and event detection. These applications represent potential directions for future studies.

Theoretical implications

CNNER typically adopts sequence labeling or span-based recognition methods. However, some approaches recognize named entities by identifying entity boundaries, inspired by object detection techniques. This study proposes a mesh grid-based entity bounding box detection approach to enrich and extend theoretical methods for nested entity recognition. Prototype networks, primarily used for image processing, have seen some adaptation for constructing category prototypes in NER tasks within NLP. However, prototype networks are not well-suited for long-sequence NLP tasks. This study proposes the MSTPN framework and DMCE loss function to comprehensively address the training and application issues of prototype networks in long-sequence NLP tasks. The experimental results demonstrate the excellent performance of our models in the CNNER task. In future work, we plan to deepen the prototype learning and parameter optimization over hierarchical semantics, refine the intermodel correlations, and investigate strategies for optimizing multiple entity spans that share the same starting position. This will enable the model to effectively address scenarios where multiple entities of different types and scales overlap at the same starting point, thereby improving its performance in Chinese named entity recognition. Furthermore, we aim to explore the applicability of the prototype network in multi-label text classification and other related tasks, validating its scalability and effectiveness within the domain of natural language processing.

Practical value

CNNER is a critical technology for structuring unstructured data, and it is essential for applications such as sentiment analysis, information retrieval, financial and legal analyses, and intelligent question answering. In sentiment analysis, the accurate identification of nested named entities can help researchers analyze different entities and relationships, thereby enabling an accurate understanding of public opinion trends and event evolution. In the information retrieval domain, entity recognition help systems better interpret user intent and providing more accurate information recommendations. In the financial and legal domains, NNER facilitates the analysis of entities and their relationships, improves the understanding of unstructured data, and contributes to work efficiency. In the current era of explosive data growth, the quick identification of key data points brings more efficient and intelligent information processing capabilities to various application scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, P., Guo, Y., Wang, F. & Li, G. Chinese named entity recognition: The state of the art. Neurocomputing 473, 37–53 (2021).

Katiyar, A. & Cardie, C. Nested named entity recognition revisited. 861–871 (Association for Computational Linguistics, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2018).

Kim, J.-D., Ohta, T., Tateisi, Y. & Tsujii, J. Genia corpus - a semantically annotated corpus for bio-textmining. Bioinformatics 19(Suppl 1), i180-2 (2003).

Sun, L., Ji, F., Zhang, K. & Wang, C. Multilayer toi detection approach for nested ner. IEEE Access 7, 186600–186608 (2019).

Loukachevitch, N. V. et al. Nerel-bio: a dataset of biomedical abstracts annotated with nested named entities. Bioinformatics 39, btad161 (2022).

Zhang, X., Luo, X. & Wu, J. A roberta-globalpointer-based method for named entity recognition of legal documents. 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) 1–8 (2023).

Wang, Y., Tong, H., Zhu, Z. & Li, Y. Nested named entity recognition: A survey. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data. 16, 1–29 (2022).

Ju, M., Miwa, M. & Ananiadou, S. A neural layered model for nested named entity recognition. In North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2018).

Liu, C., Fan, H. & Liu, J. Handling negative samples problems in span-based nested named entity recognition. Neurocomputing 505, 353–361 (2022).

Yang, P., Cong, X., Sun, Z. & Liu, X. Enhanced language representation with label knowledge for span extraction. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing 4623-4635 (2021).

Kim, Y. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (2014).

Huang, Z., Xu, W. & Yu, K. Bidirectional lstm-crf models for sequence tagging. ArXiv arXiv:1508.01991 (2015).

Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2019).

Geng, R., Chen, Y., Huang, R., Qin, Y. & Zheng, Q. Planarized sentence representation for nested named entity recognition. Inf. Process. Manag. 60, 103352 (2023).

Li, F., Lin, Z., Zhang, M. & Ji, D. A span-based model for joint overlapped and discontinuous named entity recognition. In Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W. & Navigli, R. (eds.) Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), 4814–4828 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021).

Liu, W. et al. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In European Conference on Computer Vision (2015).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S. K., Girshick, R. B. & Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 779–788 (2015).

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. B. & Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 39, 1137–1149 (2015).

Xu, Y., Huang, H., Feng, C. & Hu, Y. A supervised multi-head self-attention network for nested named entity recognition. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2021).

Yang, H.-M., Zhang, X.-Y., Yin, F., Yang, Q. & Liu, C.-L. Convolutional prototype network for open set recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44, 2358–2370 (2020).

Yang, H.-M., Zhang, X.-Y., Yin, F. & Liu, C.-L. Robust classification with convolutional prototype learning. 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 3474–3482 (2018).

Snell, J., Swersky, K. & Zemel, R. S. Prototypical networks for few-shot learning. In Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Shen, D., Zhang, J., Zhou, G., Su, J. & Tan, C.-L. Effective adaptation of hidden Markov model-based named entity recognizer for biomedical domain. In Proceedings of the ACL 2003 Workshop on Natural Language Processing in Biomedicine, 49–56 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Sapporo, Japan, 2003).

Zhou, G. Recognizing names in biomedical texts using mutual information independence model and svm plus sigmoid. Int. J. Med. Inform. 75(6), 456–67 (2006).

Zhou, G., Zhang, J., Su, J., Shen, D. & Tan, C. L. Recognizing names in biomedical texts: a machine learning approach. Bioinformatics 20(7), 1178–90 (2004).

Jia, L., Liu, S., Wei, F., Kong, B. & Wang, G. Nested named entity recognition via an independent-layered pretrained model. IEEE Access 9, 109693–109703 (2021).

Shibuya, T. & Hovy, E. H. Nested named entity recognition via second-best sequence learning and decoding. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 8, 605–620 (2019).

Wang, J., Shou, L., Chen, K. & Chen, G. Pyramid: A layered model for nested named entity recognition. In Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2020).

Zheng, C., Cai, Y., Xu, J., fung Leung, H. & Xu, G. A boundary-aware neural model for nested named entity recognition. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (2019).

Yu, J., Bohnet, B. & Poesio, M. Named entity recognition as dependency parsing. In Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (2020).

Wang, B., Lu, W., Wang, Y. & Jin, H. A neural transition-based model for nested mention recognition. 1011–1017 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Brussels, Belgium, 2018).

Marinho, Z., Mendes, A., Miranda, S. & Nogueira, D. Hierarchical nested named entity recognition. Proceedings of the 2nd Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop (2019).

Fu, C. & Fu, G. A dual-layer crfs based method for chinese nested named entity recognition. 2012 9th International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery 2546–2550 (2012).

Chen, Y. et al. Recognizing nested named entity based on the neural network boundary assembling model. IEEE Intell.Syst. 35, 74–81 (2020).

Yang, Z., Shi, S., Tian, J., Li, E. & Huang, H. Lacnner: Lexicon-aware character representation for chinese nested named entity recognition. In International Conference on Swarm Intelligence (2022).

Yang, J. et al. Mulco: Recognizing chinese nested named entities through multiple scopes. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, 2980–2989 (New York, NY, USA, 2023).

Li, P. et al. Epic: An epidemiological investigation of covid-19 dataset for chinese named entity recognition. Inf. Process. Manag. 61, 103541 (2024).

Kohonen, T. & Kohonen, T. Learning vector quantization. Self-organizing maps 245–261 (2001).

Liu, C. & Nakagawa, M. Evaluation of prototype learning algorithms for nearest-neighbor classifier in application to handwritten character recognition. Pattern Recognit. 34, 601–615 (2001).

Feng, J., Xu, G., Wang, Q., Yang, Y. & Huang, L. Note the hierarchy: Taxonomy-guided prototype for few-shot named entity recognition. Inf. Process. Manag. 61, 103557 (2024).

Kalyan, K. S., Rajasekharan, A. & Sangeetha, S. Ammus: A survey of transformer-based pretrained models in natural language processing. ArXiv arXiv.2108.05542(2021)

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Walker, C., Strassel, S., Medero, J. & Maeda, K. Ace 2005 multilingual training corpus. Linguistic Data Consortium, Philadelphia 57, 45 (2006).

Jin, Y., Xie, J. & Wu, D. Chinese nested named entity recognition based on hierarchical tagging. J. Shanghai Univ.(Natural Sci. Ed.) 28, 270–280 (2022).

Lu, W. & Roth, D. Joint mention extraction and classification with mention hypergraphs. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (2015).

Xu, L. et al. Clue: A chinese language understanding evaluation benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.05986 (2020).

Xiao, C., Hu, X., Liu, Z., Tu, C. & Sun, M. Lawformer: A pre-trained language model for chinese legal long documents. AI Open 2, 79–84 (2021).

Su, J., Lu, Y., Pan, S., Wen, B. & Liu, Y. Roformer: Enhanced transformer with rotary position embedding. ArXiv abs/2104.09864 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. Diffusionner: Boundary diffusion for named entity recognition. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 3875–3890 (2023).

Li, Y., Liao, N., Yan, H., Zhang, Y. & Wang, X. Bi-directional context-aware network for the nested named entity recognition. Sci. Rep. 14, 16106 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The work in this paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. U23B2056, and the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant No. 2022YFC3340900.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Z. conceived the conceptualization, K.Z., J.L. Z.A. and Z.L. conceived the methodology; software, K.Z. and L.W.; validation, L.W. and P.G.; resources, K.Z.; data curation, K.Z.; writing-original draft preparation, K.Z.; writing-review and editing, J.L., L.W., X.L. and Z.A.; Funding acquisition, L.W.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Lu, J., Ai, Z. et al. Transformer-based prototype network for Chinese nested named entity recognition. Sci Rep 15, 19820 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04946-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04946-w