Abstract

Several spatiotemporal data fusion methods have been developed to generate continuous fine-resolution satellite imagery using widely available datasets. This study introduces the Residual Distribution-based Spatiotemporal Data Fusion Method (RDSFM), designed to enhance fusion accuracy. RDSFM addresses residuals caused by spatial and temporal variations, utilizing the IR-MAD algorithm to estimate subpixel distribution weights based on multivariate data collected over time. Compared to existing methods, RDSFM offers several key advantages: (1) It accurately predicts seasonal variations in bands such as red and NIR, (2) It effectively handles heterogeneous landscapes and shifting land cover, and (3) It requires only one high-resolution reference image as input, minimizing data requirements. The effectiveness of RDSFM was validated using real satellite images and benchmarked against methods like unmixing-based data fusion (UBDF). Experimental results show that RDSFM successfully captures seasonal changes in coarse-resolution bands, particularly in red and NIR, making it especially useful for vegetation analysis. Additionally, RDSFM demonstrates strong performance in managing heterogeneous landscapes and areas with dynamic land cover, as confirmed by both visual and quantitative assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing demand for monitoring land cover changes and terrestrial ecosystems has driven the development of spatiotemporal data fusion techniques to address critical challenges in phenology18, natural disaster response1, anthropogenic disturbances7,11, and agricultural management12. Traditional satellite systems face inherent limitations, including frequent cloud contamination6 and lengthy revisit cycles17, which restrict their effectiveness in capturing high-resolution spatiotemporal dynamics23. To overcome these constraints, fusion methods have emerged to integrate complementary data sources—combining fine-spatial-resolution imagery (e.g., Landsat) with coarse-spatial-but-high-temporal-resolution data (e.g., MODIS)—to generate synthetic datasets with dual high resolution19.

The pioneering STARFM framework6 established the foundation for temporal interpolation-based approaches, leveraging neighboring pixels to predict intermediate states. Subsequent variants like ESTARFM22 and STARRFM10 enhanced temporal sensitivity but remained constrained by mixed-pixel challenges in heterogeneous landscapes23. Parallel developments in unmixing-based methods, initiated by Zhukov et al.25, addressed spectral heterogeneity through endmember proportion analysis, assuming temporal consistency of land cover components26. While effective in stable environments, these approaches struggle with dynamic systems where spectral signatures vary nonlinearly across bands and seasons (Fig. 1).

Spectral variability is a significant factor affecting the performance of image fusion techniques. Recent studies have highlighted the challenges posed by spectral variations, particularly in heterogeneous landscapes, where the reflectance values across different spectral bands can change drastically over time due to seasonal dynamics3. For example, in regions with diverse land cover types, such as agricultural or forested areas, the spectral reflectance can vary significantly between seasons, making it difficult for traditional fusion methods to accurately model these changes. A recent study demonstrated that spectral variability often leads to suboptimal fusion results, as the temporal changes in spectral characteristics are not always linearly predictable across different bands9.

Recent spatiotemporal data fusion methods aim to synthesize high-resolution spatial and temporal data by integrating both sparse fine-resolution images and frequent coarse-resolution images from different satellite sensors. These approaches are designed based on various principles, each with distinct strengths and limitations, making it challenging for users to select the most suitable method for their specific applications2,24. Recent studies have introduced novel machine learning techniques: Extreme Learning Machine (ELM), which directly learns mapping functions from difference images, rather than relying on complex feature representations13. In addition, deep learning methods have gained increasing attention for their ability to handle complex spatiotemporal fusion tasks, especially in the presence of cloud contamination and large land cover changes. For example, the Multi-scene Spatiotemporal Fusion Network (MUSTFN) based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) integrates multi-level features from different resolutions and sensors to improve fusion accuracy, even in areas with large registration errors and rapid land cover changes16. Similarly, Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks have been applied to fuse optical and microwave data, effectively filling gaps in cloud-contaminated imagery and improving data availability14. Other deep learning approaches, like the Dual-Branch Subpixel-Guided Network (DSNet), have been proposed for hyperspectral image classification, combining subpixel information with spectral features to enhance classification accuracy, demonstrating the growing potential of deep learning models in handling mixed pixels and improving decision boundaries8. These advancements highlight the increasing shift toward data-driven fusion techniques, offering more accurate, efficient, and adaptable solutions for spatiotemporal data fusion in remote sensing applications.

Despite these advancements, two critical gaps remain in the current spatiotemporal fusion methods. First, while deep learning approaches have shown promising results, they often require large amounts of training data, which can limit their applicability in regions where historical imagery is sparse or unavailable. This issue is particularly challenging in remote or under-monitored areas, where obtaining sufficient labeled data for training models is not feasible. Second, traditional unmixing frameworks, often struggle to accurately capture seasonal spectral variations, especially in heterogeneous landscapes with dynamic land cover changes. These methods, while effective in stable environments, struggle to account for the complex, nonlinear changes in reflectance values across different seasons and land cover types, leading to suboptimal fusion results in regions with high variability in land use or climate conditions (Fig. 1).

In temperate zones, the phenology of various landscapes is distinctly reflected in the changing reflectance values across different spectral bands, as influenced seasonal variations. This phenomenon is noticeable in a variety of land covers such as farmlands, grasslands, wetlands, and riversides. Specifically, Fig. 2a depicts the spectral data from built areas, where the change in band values between two seasons is almost negligible. In contrast, for vegetation-covered areas like farmland (Fig. 2c) and forests (Fig. 2b), there is a significant shift in Band 5 (NIR band). This band is particularly sensitive to growth, thus showing the greatest variation. Figure 2d highlights the transformation at the riverside from water to bare ground depending on the water flow resulting in a completely altered spectrum between the seasons. The degree of change in band values varies significantly across different types of land cover, which introduces uncertainties these land-cover types coexist within a single coarse pixel.

To address these limitations, we propose the Residual-Distribution-based Spatiotemporal Data-Fusion Method (RDSFM). This method aims to distribute residuals more accurately across the sub-pixels of each band. is specifically designed to effectively reflect the degree of change in heterogeneous areas and in regions where land cover types have altered. RDSFM requires only one high resolution image and two high temporal resolution images to function optimally. This study lies in its potential to improve the precision of remote sensing data analysis by refining the spatial and temporal details captured in heterogeneous landscapes. This particularly valuable in ecological monitoring, urban planning, and agricultural management. Additionally, the RDSFM method could substantially contribute to the advancement of remote sensing technologies and methodologies, more sustainable management of natural resources.

Methods

To more accurately distribute residuals across each subpixel, this study introduces a weighting system based on multivariate relationships between images captured at times t1 and t2. This weighting is determined through the Iteratively Regularized Multivariate Alteration Detection (IR-MAD) method, which is designed detect changes in multivariate data collected at two temporal points from the same geographical area15. The custom code used in this study for the RDSFM is available at on personal webpage (https://homepage.ybu.edu.cn/jinyihua).

Estimate the residuals

The real changed values of coarse images between t1 and t2 can be written as follows:

where \(\:{C}_{1}({x}_{i},\:{y}_{i},\:b)\) is band b value of coarse pixel at location \(\:({x}_{i},\:{y}_{i})\) at t1, and \(\:{C}_{2}({x}_{i},\:{y}_{i},\:b)\) is band b value at t2.

In the context of a homogeneous landscape, the errors stemming from temporal changes can be characterized by the discrepancies between the actual values and \(\:{F}_{2}^{TP}\), the temporally predicted fine-resolution image at t2. Therefore, the predicted changes between \(\:{F}_{2}^{TP}\) and the actual fine-resolution image at t1 are as follows:

\(\:m\) is the number of fine pixels within one coarse pixel, and \(\:{F}_{2}^{TP}\)is the temporal predicted value of fine pixels at t2 using unmixing-based method.

Between the real changed values and the temporally predicted changed values, there are residuals. These residuals mainly are caused by spatial and temporal change, such as a land-cover type change and within-class variability across the image, and the pixel value changed by season23. Distributing residuals \(\:\text{R}\left({\text{x}}_{\text{i}},\:{\text{y}}_{\text{i}},\:\text{b}\right)\) to fine pixels within a coarse pixel is important to improve the accuracy of the predict fine pixel value at t2. The residual R of each band between the true changed values and the predicted changed values can be derived as follows:

Because different landscape types have similar reflectance at a particular time, it will be misclassified and generate errors in some cases. The important terms of residual distribution is understanding the variation of each bands. For more precisely distribute the residuals to subpixels, we introduce MAD-based weights, estimated by IR-MAD.

Estimate weights for residual distribution using IR-MAD

The IR-MAD method is adopted for multi-variate calculation, owing to its effectiveness, speed and fully automatic processing. For distributing the residuals to each subpixel more properly, this study introduced a weight based on multi-variates between the images at t1 and t2. It is estimated by iteratively regularized multi-variate alteration detection (IR-MAD), which detect changes in multi-variate data acquired at two points in time covering the same geographical region15.

The main idea of IR-MAD is a simple iterative scheme to place high weights on observations that exhibit little change over time. The IR-MAD algorithm is an established change detection technique based on canonical correlation analysis. Mathematically, the IR-MAD tries to identify linear combinations of two variables, \(\:{a}^{T}X\) and \(\:{b}^{T}Y\), to maximize the objective function \(\:{max}_{a,b}\:var({a}^{T}X-{b}^{T}Y)\) with \(\:V\left\{{a}^{T}X\right\}=V\left\{{b}^{T}Y\right\}=1\). The dispersion matrix of the MAD variates is as follows:

A MAD variate is the difference between the highest order canonical variates and it can be expressed as follows:

where \(\:{a}_{i}\) and \(\:{b}_{i}\) are the defining coefficients from a standard canonical correlation analysis.

Using a brief derivation, the objective function can be reformulated to minimize the canonical correlation of two variables, that is \(\:min\lambda\:=corr({a}^{T}X,\:{b}^{T}Y)\), where corr represents a correlation function. If we let the variance-covariance matrix of X and Y be \(\:{{\Sigma\:}}_{XX}\) and \(\:{{\Sigma\:}}_{YY}\), respectively, and their covariance be \(\:{{\Sigma\:}}_{XY}\), the correlation can be formulated to Rayleigh quotients as follows:

Equation (8) is just an eigenvalue problem, that is \(\:{{\Sigma\:}}_{XY}{{\Sigma\:}}_{YY}^{-1}{{\Sigma\:}}_{YX}a={\lambda\:}^{2}{{\Sigma\:}}_{XX}a\), and hence the solutions are the eigenvectors of \(\:{a}_{1},\:\dots\:,\:{a}_{n}\) corresponding to the eigenvalues \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}^{2}\ge\:\dots\:\ge\:{\lambda\:}_{n}^{2}\ge\:0\) of \(\:{{\Sigma\:}}_{XY}{{{\Sigma\:}}_{YY}^{-1}{\Sigma\:}}_{YX}\) with respect to \(\:{{\Sigma\:}}_{XX}\). Now assuming that the MODIS image is preprocessed to be zero mean, we denote \(\:MAD={a}^{T}X-{b}^{T}Y\) as the MAD components of the combined bi-temporal image. In this process, the ENVI extension for IR-MAD generated by Canty4 was used for running the IR-MAD and obtaining the MAD variates.

MAD variates are determined by the correlation between two images; a larger value means much change occurred in the spectrum, indicating changed areas, and lower values means there are no changes in the spectrum and indicate the areas are the same as the previous image4,15. Here, the input data for multi-variate calculation are a fine-resolution image at t1 and coarse-resolution image at t2, which resampled to a fine resolution through a bilinear interpolation method.

Distribute the residuals to the fine pixel

Errors in temporal prediction are mainly caused by land-cover type change and within-class variability across the image. Therefore, this study proposed a new weighted function to distribute residuals to subpixels, considering the variates in each band and the heterogeneous degree. This study introduced a multi-variate-based weight (\(\:{W}_{MAD}\)) as follows:

.For the heterogeneity pixels, we addressed the issue of heterogeneous coarse pixels with higher residual weights by utilizing the Homogeneous Index (HI).

where \(\:{\text{I}}_{\text{k}}\) approaches 1, means the kth fine pixels within a moving window with the same land cover type as the central fine pixel \(\:({x}_{ij},\:{y}_{ij})\) being considered, otherwise \(\:{\text{I}}_{\text{k}}\) approaches 0. HI ranges from 0 to 1, and larger values indicate more homogeneous landscape, and smaller values indicate more heterogeneous. The weight for combining the two cases is:

The weight is then normalized as follows:

Then, the residual distributed to jth fine pixel is as follows:

Summing the distributed residual and the temporal change, we can obtain the prediction of the total change of a fine pixel between t1 and t2 as follows:

Testing experiment

For the experiments, this study utilized Landsat images to cover two distinct study areas, each exhibiting unique spatial and dynamics. The first area features a complex and heterogeneous landscape, while the second undergoes significant land-cover-type changes. These sites have been pivotal in various spatiotemporal data-fusion methods, such as STARFM, ESTARFM, and FSDAF, serving as benchmarks for comparing testing these techniques. The satellite images for both sites are cloud-free Landsat 7 ETM + images (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov), which were atmospherically corrected using the FLAASH (Fast Line-of-sight Atmospheric Analysis of Spectral Hypercubes) algorithm.

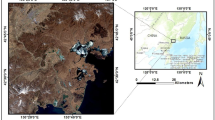

At the first site (Fig. 2), located in the southern region of New South Wales, Australia, characterized by complex and heterogeneous terrain, with coordinates at 145.0675ºE, 34.0034ºS. These images, corresponding to Path/Row93/84, were taken on November 25, 2001, and January 12, 2002, respectively. The predominant land types within this locale include irrigated rice cropland, dryland agriculture, and woodlands. Notably, rice croplands are typically irrigated during October and November5,23. The phenological changes in this area, particularly in the rice cropland, are defined by the seasonal irrigation practices, where rice fields are typically flooded in October and November, marking a distinct shift in vegetation dynamics. This seasonal change is crucial in understanding the land-cover transitions in this region.

Test data in a complex and heterogeneous landscape: Landsat images acquired on (a) November 25, 2001 and (b) January 12, 2002, (c) and (d) are the corresponding MODIS images with a 500-m spatial resolution to (a) and (b). All images use red-green-blue as RGB. The Landsat 7 ETM + images were obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) (https://www.usgs.gov/), while the MODIS MOD09GA were provided by NASA’s Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) (https://earthdata.nasa.gov/).

The second site (Fig. 3), experiencing land cover type changes, is located in northern New South Wales, Australia (149.2815°E, 29.0855°S). This area is relatively homogeneous, featuring extensive croplands and natural vegetation. Two Landsat images were captured, on November 26, 2004, and the other on December 12, 2004 (Path/Row 91/80). A flood event occurred in December 2004, which is evident from the 12 Landsat image displaying a vast inundated region. This flood event caused a distinct and rapid phenological change in the land cover, particularly transforming some of the croplands and vegetation areas into water-covered pixels. The phenological shift from terrestrial vegetation to water in these regions illustrates the dynamic land-cover type change during extreme weather events. Such changes are crucial for monitoring and understanding the temporal variations in land cover in this region.

Test data in area with land-cover type change: Landsat images acquired on (a) November 26, 2004 and (b) December 12, 2004, (c) and (d) are the corresponding MODIS images with a 500-m spatial resolution to (a) and (b). All images use red-green-blue as RGB. The Landsat 7 ETM + images were obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) (https://www.usgs.gov/), while the MODIS MOD09GA were provided by NASA’s Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) (https://earthdata.nasa.gov/).

MODIS images were also incorporated for data fusion in this study. The MODIS data utilized comes from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) onboard the Terra and Aqua satellites, with a spatial resolution of 500 m. The specific product used in this study is the MOD09GA (Surface Reflectance, 8-day L3 Global 500 m), which provides corrected surface reflectance values for bands 1 to 7. To ensure proper alignment between the MODIS and Landsat data, a coregistration process was performed. This process involved resampling the MODIS data to match the spatial resolution of Landsat imagery (30 m) and aligning the georeferencing to ensure pixel-wise accuracy. Furthermore, atmospheric correction was applied to both the MODIS and Landsat datasets to mitigate atmospheric scattering and absorption effects. The MODIS data were corrected using the MOD09GA product’s built-in atmospheric correction algorithm, while Landsat data underwent standard atmospheric correction through the FLAASH (Fast Line-of-sight Atmospheric Analysis of Spectral Hypercubes) method. These preprocessing steps ensured that the data fusion process was based on accurately coregistered and atmospherically corrected datasets, allowing for reliable change detection and fusion results.

The performance of the RDSFM was evaluated in comparison with the unmixing-based data-fusion algorithm (UBDF) developed by Zhukov et al. in 1999, and the FSDAF algorithm introduced by Zhu et al. in 2016. This comparative analysis was pertinent since RDSFM is similarly based on an unmixing methodology. Both the predicted fine-resolution images derived from these algorithms were assessed against the actual images through qualitative and quantitative means. To represent the different facets of accuracy, several indices were employed. The root mean square error (RMSE) measured the deviation between the predicted and actual reflectance values. Additionally, the correlation coefficient (r) was utilized to quantify the linear relationship between the predicted reflectance and the true reflectance. The mathematical definitions for RMSE and r are as follows:

where n is the number of samples, \(\:{P}_{i}\) is the predicted value of pixel i, and \(\:{O}_{i}\) is the observed value in pixel i:

where \(\:{x}_{i}\), \(\:{y}_{i}\) are the single sample indexed with I, and \(\:\stackrel{-}{x}=\frac{1}{n}\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}xi\) (the sample mean), and analogously \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\).

The average difference (AD) between the predicted and true images was employed to quantify the overall bias in the predictions. A positive AD suggests that the fused image tends to overestimate the actual values, whereas a negative AD indicates an underestimation.

In addition to the previously mentioned quantitative evaluations, a visual assessment index, the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM)20,23, was also employed to measure the similarity in overall structure between the true and predicted images as follows:

where \(\:{\mu\:}_{X}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{Y}\) are means; \(\:{\sigma\:}_{X}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{Y}\) are the variance of the true and predicted images, respectively; \(\:{\sigma\:}_{XY}\) is the covariance of the two images; and \(\:{C}_{1}\) and \(\:{C}_{2}\) are two small constants to avoid unstable results when the denominator of Eq. 15 is very close to zero. A SSIM value closer to 1 indicates more similarity between the two images.

Results

Test in heterogeneous landscape

Visually comparing the predictive results generated by the two methods, as depicted in Fig. 4, it is evident that both methods successfully preserve spatial details. Figures 4b and c showcase a Landsat-like image dated January 11, 2002, predicted using the FSDAF and RDSFM methods respectively. Figures 5 and 6 depict the predicted red band and NIR band, which are crucial for vegetation analysis. The visual comparison indicates that the images predicted by both methods bear a general resemblance to the original Landsat image shown in Fig. 4. Given that pixels exhibiting significant changes are assigned relatively large change values, the predictions made using the RDSFM method appear to more closely replicate the actual image in terms of detail and color. This observation suggests that while both methods are capable of capturing the general phenological changes in complex and heterogeneous landscapes, the results from the RDSFM method are more consistent with the actual image.

In an analysis of the quantitative indices derived from the original Landsat image dated January 11, 2002, it is evident that three methodologies have effectively incorporated temporal change information into the Landsat imagery to predict outcomes for the same date. Among the three bands, the fusion results from RDSFM exhibit a lower Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and a higher correlation coefficient (R) compared to those obtained through UBDF and FSDAF (Table 1). This indicates a superior accuracy in the predictions made by RDSFM over the alternative methods. Notably, the Near-Infrared (NIR) band shows the most pronounced disparity in accuracy between RDSFM and the other methods. Given that the Landsat images were captured during the early growing season, both the NIR and red bands displayed significant changes in reflectance compared to other bands. RDSFM’s substantial enhancement in predicting outcomes for the NIR and red bands suggests a more robust capability in capturing the significant temporal changes between the dates of input and prediction.

Test in land cover type change

A zoom-in section was utilized to underscore the distinctions between the predicted and actual images (Fig. 7). The image predicted by RDSFM aligns more closely with the original in terms of spatial details compared to those predicted by FSDAF, as evident in the enhanced views of the red and NIR bands shown in Figs. 8 and 9. Notably, when comparing the zoomed-in sections of the two original Landsat images, a small area of a lake is observed transitioning from non-water to water. Despite FSDAF accurately predicting the pixel values for this small area, RDSFM demonstrates superior capability in preserving such minor changes.

The quantitative indices derived from the fused outcomes compared with the original Landsat image at the forecast interval show that all data-fusion techniques successfully captured essential temporal change information between the input and prediction images. Among the three bands, RDSFM delivered the most precise forecasts, evidenced by the lowest RMSE and highest values in correlation coefficient (R) and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM). Regarding the overall predictive bias, the minimal Absolute Difference (AD) values indicate that all three methods achieved nearly unbiased results (Table 2).

Discussion

To track the rapid dynamics of land surfaces with temporal changes, spatiotemporal data-fusion techniques have been developed to integrate satellite imagery with varying spatial and temporal resolutions. Traditional methods, however, have struggled to accurately predict pixel values in areas of land-cover change during the intervals between the input and forecast dates. Addressing this challenge, this study introduces a novel spatiotemporal data-fusion approach, named Residual Distribution Spatiotemporal Fusion Method (RDSFM). This method blends temporally sparse, high-resolution images with temporally dense, low-resolution images. RDSFM incorporates principles from IR-MAD, which enables the detection of spectrally changed pixels without supervision, the unmixing-based method, and the Histogram Intersection (HI) concept, previously implemented in FSDAF with proven high accuracy in handling mixed coarse pixels. The findings confirm that RDSFM delivers superior accuracy and more effectively predicts areas with significant spectral changes.

The spectral variation of each pixel in RDSFM is more robust compared to other methodologies due to the application of Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) for weighting. This adaptation leverages MAD to detect significant changes across multiple bands and bi-temporal datasets through a statistical approach. Data utilized in the IR-MAD method encompass both a high-resolution image at time t1 and a lower-resolution image at time t2, facilitating the detection of temporal transformations. Similarly, the use of a high-resolution image from t1 and a lower-resolution image from t1 in the IR-MAD technique allows for the identification of changes caused by different sensors.

Weights are derived by combining the MAD values, as shown in Figs. 10b and 11b, which present the distribution of MAD variates for the red and NIR bands between the initial input time and the prediction time. The similarity in the change detection distribution observed in the original Landsat images at t1 and t2 (Figs. 10b and 11b) with the estimated MAD distribution between these times highlights the effectiveness of this method. The MAD-based weights applied in RDSFM help more accurately capture temporal variations in these plant-sensitive bands, leading to more reliable NDVI calculations. The analysis of the results across all bands indicates that RDSFM performs well not only in the red and NIR bands, which were initially emphasized, but also in the other spectral bands (i.e., blue, green, SWIR1, and SWIR2). Thus, MAD-based weights efficiently address individual band reflectance variations, applying uniform weights across bands despite heterogeneous reflectance changes. This MAD-based weighting recognizes the non-uniform reflectance changes over time, as evidenced in Figs. 10 and 11, band 5 (SWIR1) shows a notable decrease in reflectance, while other bands, particularly the NIR and SWIR2 bands, exhibit increases. By adopting a MAD-based weight system, this study offers a more realistic distribution of temporal changes, demonstrating a significant improvement over conventional method.

The results of RDSFM combine two changes in the distribution results distributed by the homogeneous index and the weight based on MAD. In heterogeneous landscapes, if one pixel has little variation between t1 and t2, the result has the possibility to be biased toward HI. On the contrary, if one pixel has a large variation between t1 and t2, the result has a possibility of depending on the weight of MAD. Therefore, in some cases, some bands do not change much through temporal change, such as Band 1 (blue) and Band 2 (green), then the blending result depends on HI, and the result will be similar to that of the FSDAF, which also uses an HI index for heterogeneous landscape prediction. In contrast, for bands like Band 4 (NIR), Band 5 (SWIR1), and Band 6 (SWIR2), the MAD-based weights are more effective in capturing temporal changes, resulting in higher accuracy than methods relying solely on unmixing or HI. The weights-based MAD is most effective in the NIR band, the band with a large difference in reflectance value depending on the season, and shows higher accuracy than unmixing based method. This is because the MAD can detect temporal differences in each band, and can more accurately predict the pixels that have a spectral change.

Recent studies on spatiotemporal fusion, such as the work of Qin et al.16, have introduced deep learning-based fusion techniques and hybrid statistical models to enhance prediction accuracy. While these methods show promise, they often require large-scale training datasets and significant computational resources, limiting their applicability in certain remote sensing scenarios. In contrast, RDSFM provides a computationally efficient alternative by leveraging statistical change detection and unmixing principles, achieving comparable or superior accuracy in heterogeneous landscapes without the need for extensive training datasets. Furthermore, RDSFM integrates MAD-based weighting to better handle temporal variations, particularly in plant-sensitive bands such as NIR and SWIR2. This enhancement underscores the significance of this study in advancing spatiotemporal fusion methodologies by balancing computational efficiency and predictive accuracy.

Conclusion

This study introduces the Residual Distribution based Spatio-temporal Data Fusion Method (RDSFM), a novel approach designed to enhance the accuracy and applicability of spatio-temporal data fusion in satellite imagery. Through the strategic utilization of the IR-MAD algorithm to estimate subpixel distribution weights, RDSFM effectively addresses the challenges posed by spatial and temporal variability in heterogeneous landscapes.

Our findings demonstrate several key advantages of RDSFM over existing methods. Firstly, RDSFM excels in predicting variable bands seasonally, particularly in the red and NIR bands, crucial for vegetation-related analyses. Secondly, it demonstrates robust performance in accommodating landscapes with dynamic land cover changes, surpassing traditional methods in accuracy and detail preservation. Thirdly, RDSFM requires minimal input data, making it practical for applications where comprehensive satellite imagery may be limited.

Although the RDSFM is capable of predicting both heterogeneous landscapes and spectral changes between input and prediction dates, it struggles to detect minute spectral variations due to land-cover changes. This limitation becomes apparent when only a few fine pixels undergo land-cover changes that are not visible in interpolated coarse-resolution images. Moreover, since RDSFM is designed based on the IR-MAD framework, it does not directly support other products like NDVI and LST. The RDSFM requires at least three bands for effective blending15,21. While machine learning approaches do not suffer from this limitation, RDSFM’s ability to focus on changes in individual reflectance bands through the MAD weighting gives it an edge in vegetation-focused analyses where NDVI and similar indices are crucial. RDSFM improves accuracy by adjusting the residual distribution, particularly in scenarios involving spatial and temporal pixel variations. RDSFM enhances prediction accuracy across different seasonal bands, and adapts well to scenarios with mixed pixels and variations in land cover types.

In conclusion, RDSFM represents a significant advancement in spatio-temporal data fusion methodologies, offering practical solutions for monitoring dynamic landscapes and supporting a wide range of environmental and agricultural applications.

Data availability

The data and RDSFM code used in this study are available on the first author’s personal homepage at https://homepage.ybu.edu.cn/jinyihua.

References

Behling, R., Roessner, S., Segl, K., Kleinschmit, B. & Kaufmann, H. Robust automated image Co-Registration of optical Multi-Sensor time series data: database generation for Multi-Temporal landslide detection. Remote Sens. 6, 2572–2600 (2014).

Belgiu, M. & Stein, A. Spatiotemporal image fusion in remote sensing. Remote Sens. 11, 818 (2019).

Borsoi, R. A. et al. Spectral variability in hyperspectral data unmixing: A comprehensive review. IEEE Geoscience Remote Sens. Magazine. 9, 223–270 (2021).

Canty, M. J. Image Analysis, Classification and Change Detection in Remote Sensing: with Algorithms for ENVI/IDL and Python. (Third edition ed.). CRC Press (2014).

Emelyanova, I. V., McVicar, T. R., Van Niel, T. G., Li, L. T. & van Dijk, A. I. J. M. Assessing the accuracy of blending Landsat–MODIS surface reflectances in two landscapes with contrasting Spatial and Temporal dynamics: A framework for algorithm selection. Remote Sens. Environ. 133, 193–209 (2013).

Feng, G., Masek, J., Schwaller, M. & Hall, F. On the blending of the Landsat and MODIS surface reflectance: predicting daily Landsat surface reflectance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44, 2207–2218 (2006).

Grinand, C. et al. Estimating deforestation in tropical humid and dry forests in Madagascar from 2000 to 2010 using multi-date Landsat satellite images and the random forests classifier. Remote Sens. Environ. 139, 68–80 (2013).

Han, Z. et al. Dual-Branch Subpixel-Guided network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 62, 1–13 (2024).

Han, Z. et al. Subpixel spectral variability network for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 63, 1–14 (2025).

Hilker, T. et al. A new data fusion model for high spatial- and temporal-resolution mapping of forest disturbance based on Landsat and MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 113, 1613–1627 (2009).

Jin, Y. et al. Characterization of two main forest cover loss transitions in North Korea from 1990 to 2020. Forests 14, 1966 (2023).

Li, S. & Li, X. Global Understanding of farmland abandonment: A review and prospects. J. Geog. Sci. 27, 1123–1150 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. Fast and accurate Spatiotemporal fusion based upon extreme learning machine. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 13, 2039–2043 (2016).

Mizuochi, H., Iijima, Y., Nagano, H., Kotani, A. & Hiyama, T. Dynamic mapping of Subarctic surface water by fusion of microwave and optical satellite data using conditional adversarial networks. Remote Sens. 13, 175 (2021).

Nielsen, A. A. The regularized iteratively reweighted MAD method for change detection in Multi- and hyperspectral data. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 16, 463–478 (2007).

Qin, P., Huang, H., Tang, H., Wang, J. & Liu, C. MUSTFN: A Spatiotemporal fusion method for multi-scale and multi-sensor remote sensing images based on a convolutional neural network. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 115, 103113 (2022).

Roy, D. P. et al. Multi-temporal MODIS–Landsat data fusion for relative radiometric normalization, gap filling, and prediction of Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 112, 3112–3130 (2008).

Shen, M., Tang, Y., Chen, J., Zhu, X. & Zheng, Y. Influences of temperature and precipitation before the growing season on spring phenology in grasslands of the central and Eastern Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 151, 1711–1722 (2011).

Song, Y., Njoroge, J. B. & Morimoto, Y. Drought impact assessment from monitoring the seasonality of vegetation condition using long-term time-series satellite images: a case study of mt. Kenya region. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185, 4117–4124 (2013).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Wang, B., Choi, S. K., Han, Y. K., Lee, S. K. & Choi, J. W. Application of IR-MAD using synthetically fused images for change detection in hyperspectral data. Remote Sens. Lett. 6, 578–586 (2015).

Zhu, X., Chen, J., Gao, F., Chen, X. & Masek, J. G. An enhanced Spatial and Temporal adaptive reflectance fusion model for complex heterogeneous regions. Remote Sens. Environ. 114, 2610–2623 (2010).

Zhu, X. et al. A flexible Spatiotemporal method for fusing satellite images with different resolutions. Remote Sens. Environ. 172, 165–177 (2016).

Zhu, X., Cai, F., Tian, J. & Williams, T. K. A. Spatiotemporal fusion of multisource remote sensing data: literature survey, taxonomy, principles, applications, and future directions. Remote Sens. 10, 527 (2018).

Zhukov, B., Oertel, D., Lanzl, F. & Reinhackel, G. Unmixing-based multisensor multiresolution image fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 37, 1212–1226 (1999).

Zurita-Milla, R., Clevers, J. G. P. W. & Schaepman, M. E. Unmixing-Based Landsat TM and MERIS FR data fusion. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 5, 453–457 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Jingrong Zhu for her valuable contributions to the earlier stages of this manuscript. Her input in literature survey was instrumental in shaping the direction of the study. We are grateful for her support throughout this project.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province of China (NO. YDZJ202401516ZYTS) and Higher Education Discipline Innovation Project (No. D18012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yihua Jin conceived the study, designed the experiments, and supervised data analysis; Zhenhao Yin performed collection and processing; Weihong Zhu contributed to manuscript writing; Dongkun Lee provided expert insights on the theoretical framework and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, Y., Yin, Z., Zhu, W. et al. Improving spatiotemporal data fusion method in multiband images by distributing variates. Sci Rep 15, 20854 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05016-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05016-x