Abstract

Exposure to communal music may help regulate mood and cultivate feelings of belonging. Across two studies, we tested whether exposure to communally experienced (communal) music could impact participants’ affect following social ostracism and negative mood induction. Participants were exposed to a social media ostracism paradigm (SMOP; n = 106) or an autobiographical negative memory recollection task (ANMIT; n = 116), followed by a communal or a control song. Participants exposed to the communal song showed improved positive affect in both studies (p study 1 = 0.004; p study 2 = 0.022), whereas affect worsened for those exposed to the control songs. Additionally, participants in the communal condition reported a greater sense of belonging associated with the music compared to the control (p = 0.026). These findings suggest that communal music may improve affect—improving positive affect by strengthening social connectedness—even when listened to in isolation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Feelings of non-belonging, or ambiguity about whether or not one belongs, pervade individuals’ experiences of work, their local communities, and their country1. Among a United States sample including 4,797 respondents, fewer than 36% of people expressed a firm sense of belonging across different social contexts. In addition, 17% of individuals in the same study experienced a sense of non-belonging, or ambiguity about belonging in every domain of their life, including with family and friends. These statistics are especially concerning since feelings of social connectedness may be protective factors against anxiety and depression2. Communal music-based interventions may be uniquely poised to increase feelings of belongingness and to improve affect in times of exclusion and distress.

Music-based interventions are remarkably versatile and have shown positive benefits in a variety of clinical and non-clinical settings3. Participatory music (i.e., active involvement in music creation and performance, encompassing activities such as singing and playing instruments), for instance, is known to improve quality of life4,5, perceived social support, self-esteem, and self-confidence4,6,7 (see Dingle, Sharman8 for a comprehensive review). On the other hand, receptive music listening, which is a more passive activity that often does not involve the participant choosing what to listen to8, is commonly employed in healthcare and other settings. Receptive music listening has shown promising results in promoting overall well-being through mechanisms such as pain relief and anxiety reduction9. Furthermore, intentional music listening studies, characterized by protocols involving participants in the choice of repertoire, have also shown positive results, including improved mood10,11.

Music-based interventions are likely successful because music has the capacity to induce different affective states, with recent growing interest in the topic (see Chong, Kim12 for a review). Blasco-Magraner, Bernabé-Valero13, for instance, investigated how receptive and participatory music exposure modulated positive and negative affect, finding that both led to an increase in positive affect and a decrease in negative affect (with sad music particularly effective for decreasing negative affect). Interestingly, the authors also report that participatory music (i.e., participants coming together to play a song) led to better results than simply listening to music. The same is true in the context of mood inductions. Using the Trier Social Stress Test14 to induce anxiety, Groarke, Groarke15 showed that simply listening to music (compared to silence) led to a decrease in state anxiety. Unfortunately, the potential for social belonging experienced through music was not explored in either study. In short, these findings demonstrate that music is effective in shifting emotional experiences, not only enhancing positive emotions, but also mitigating negative ones, reinforcing its value as a means for affect regulation.

Multicultural studies point to the use of music for similar goals and with similar effects, across different countries. For instance, Feneberg, Stijovic16 showed, in a cohort study of 711 adults in Austria and Italy, that music listening significantly reduced stress and improved mood, with heightened effects for individuals with chronic stress. Additionally, in a survey spanning 11 countries (n = 5,619), Granot, Spitz17 found that music (among activities such as information seeking, entertainment using movies, games, or series, physical activities, etc.) was the most effective activity for producing enjoyment, venting negative emotions, and fostering self-connection. Notably, it was second only to socialization for creating togetherness. These findings were consistent across genders and countries, with minor age variations as well as a notable impact of music’s personal importance.

Music-based interventions are inherently complex, encompassing an array of variables that likely interact to produce the observed benefits. For example, researchers may consider musical arrangement (style, tempo, melody, instrumentation, harmony), music attributes (genre, complexity, thematic elements), modes of engagement (singing, listening, playing, composing), and previous music exposure (relevance, familiarity, preferences) when evaluating the impact of music on mental health or wellbeing18. The interplay between musical characteristics and individual traits (cultural background, age, gender) as well as the context in which music is applied (clinical, community, home-based, or self- or therapist-guided) is also expected to significantly influence the outcomes.

Most studies investigating the connection between individually targeted music listening and affective states have investigated music familiarity, nostalgia, and preference3,19,20,21,22,23. Familiar music refers to pieces previously encountered by the listener, allowing for easier recognition, memory retrieval, and expectation fulfillment, often enhancing emotional engagement 23,24. For example, exposure to long-known music (20 + years) was associated with improved memory markers in individuals with early-stage cognitive decline22, subsequently contributing to enhanced measures of well-being. Along the same lines, exposure to music that evokes nostalgia, i.e., “a self-relevant emotion, incorporating personal, meaningful, and mostly positive autobiographical memories”25, p. 2046–2047], has also led to interesting findings. In a recent review, Sedikides, Leunissen25 highlight several psychological benefits of nostalgia-evoking music, including, but not limited to, an increased sense of connectedness and belonging. Interestingly, these findings remain even in the absence of music (i.e., with lyrics alone)26. Adding to that, preferred music was found to differentially activate the ventral striatum19, a region associated with reward processing and implicated in various mental disorders27. Finally, listening to music relevant to oneself, i.e., chosen by the individual, differentially modulates pain responses and anxiety28,29. In short, the effectiveness of music-based interventions is significantly influenced by various musical characteristics and the interplay between these attributes and individual traits, engagement modes, and context. Unfortunately, the social context where music is experienced has been largely neglected or overlooked as a variable in many psychological studies.

Music-based interventions demonstrate significant potential across social contexts, spanning family, peer, educational, and workplace settings. Boer and Abubakar30 investigated how music experienced in families and among peers contributes to social cohesion and emotional well-being of younger individuals. Drawing on data from 760 participants across Kenya, the Philippines, New Zealand, and Germany, the findings revealed that music listening strengthens family cohesion and peer group bonds, with peer group music generally linked to well-being. However, these experiences were particularly impactful for emotional well-being in traditional/collectivistic cultures. Additionally, family music consistently fostered cohesion across all stages, while peer group rituals’ effects varied depending on cultural and developmental contexts. Although interesting, the study’s cross-sectional design, coupled with the fact that participants were not exposed to the music they reported on, limit the generalizability of its findings.

Studying the effect of music and its association with the context in which it is experienced is important because previous research suggests that music listening can serve as a substitute for the social environment in which it occurs31. Schäfer and Eerola31 argue that this sense of connection may arise through memory recall or identification processes, functioning as a type of social surrogate. For instance, in a small qualitative study with elderly individuals (n = 14), Groarke, MacCormac32 identified that listening to music reminded participants of communal settings where the songs had been previously experienced. The songs were intentionally chosen by the participants to induce positive affect and potentially functioned as a social surrogate during the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine. These findings are promising and point to the need to further explore the role communal music (i.e., music experienced by most people in a given context) plays in fostering wellbeing. Within the existing body of literature, the terms “communal” and “community” are often used interchangeably to describe artistic initiatives aimed at nurturing social engagement and inclusivity within group contexts. As a differentiation between these terms may be lacking within music psychology studies, we propose a distinction: communal music here emphasizes music that is experienced within a group or community with a shared identity (e.g., listening to one’s national anthem in a stadium), contributing to an increase in sense of belonging, whereas community music serves as a broader term encompassing a wide range of musical activities and programs in general group settings (e.g., listening to a foreign national anthem in a stadium). In other words, for communal music to be experienced, the individual must have a sense of affiliation to the community in which that musical experience happened.

Taken together, the findings reported above build on the well-established phenomenon that music listening can enhance well-being and suggest that fostering a sense of belonging may be a mechanism by which it occurs, even when the music is experienced in isolation. In the present study, we investigated whether individual exposure to communal music versus neutral or non-communal positive music specifically serves as an affect regulator—either by enhancing levels of positive affect or mitigating increases in negative affect and state anxiety during times of social exclusion or personal distress (associated with the likelihood of exclusion). We hypothesized that individuals exposed to a communal music stimulus following exposure to a social media ostracism paradigm (SMOP; Study 1) or an autobiographical negative mood induction task (ANMIT; Study 2) would experience a less marked decline in general affect (positive affect, an improvement in their negative affect, and decreased state anxiety) compared to individuals exposed to a control (i.e., neutral or non-communal positive) music stimulus. We further hypothesized that feelings of belonging (more than positive characteristics related to the song) would be higher in those exposed to communal versus control music and would mediate the relationship between change in affect and the condition. Finally, we explored the role of familiarity, music affect, and nostalgia in improving affect.

The SMOP utilized in the first study allowed us to consider whether communal music improved affect after an externally driven event of being ostracized. The ANMIT, on the other hand, allowed us to consider this same dynamic after an internally driven experience of remembering a time when participants felt they disappointed others (disappointing others may be a measure of falling short of relational expectations, risking ostracism33,34,35). Using these two different procedures allowed us to consider the impact of communal music on both externally and internally driven negative affect, which, in these protocols, were both related to social bonds or one’s perceived social standing. Given that many theories on the evolutionary role of music emphasize its social functions, we felt it was particularly important to examine how communal music affects affect in the context of socially relevant events. Several evolutionary psychologists propose that, in our ancestral past, music was critical in helping people to bond and maintain a sense of group solidarity, especially in the context of larger group sizes29. Others propose that music may have been primarily important in mate selection, conflict reduction, or transgenerational communication36. Given these proposed links between music and social bonding, this study investigated whether re-experiencing songs previously shared in a communal setting could help ease feelings of social exclusion or memories of having disappointed someone.

Study 1

Materials and methods

Transparency and openness

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study. The study follows Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS)37. The data were analyzed using R, version 2024.09.0 + 375 (R Core Team, 2020). This study’s design and analysis were not preregistered.

Participant recruitment and song selection

To select the communal music stimulus, we first recruited a sample of participants from the United States who reported watching sports in general and baseball in particular (phase 1). These participants were recruited using Prolific. Participants were asked 1) if they had ever seen a baseball game in a stadium, 2) what the home team was, 3) how much (on a 0–10 scale) they considered themselves to be a fan of that team, and 4) if any particular song came to mind when they thought about being at the stadium, and if so, what that song was. Responses were only considered for those participants who reported having seen a game at the stadium (n = 270). The song “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” was mentioned by more than 40% of the participants. Accordingly, this song was chosen as the communal music for the experimental group. Details on the participants’ demographics and songs are provided in Table S1.

Individuals who reported having attended a live baseball game in a stadium were subsequently invited to participate in the second phase of study 1, which was presented to them as an independent project. We restricted participation to this sample to ensure that these participants had been exposed to “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” in a communal setting. The final sample consisted of 106 participants (see Table 1 for further details). The sample size was determined by the available funding for this pilot test.

Cultural contexts of experimental and control songs

Both songs used in study 1, "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" and "Guggisberglied,” can be regarded as forms of communal music. They are often employed in contexts that unite people through shared singing, cultural traditions, and unifying themes, potentially fostering a sense of community and shared identity among participants in the musical experience. The "Take Me Out to the Ball Game," composed by Jack Norworth and Albert Von Tilzer in 1908, has become an unofficial anthem of North American baseball, with its chorus traditionally sung collectively by fans during the seventh inning stretch, enhancing the communal atmosphere and highlighting the common experience of attending a baseball game. The Library of Congress recognizes the enduring impact of the song on American musical culture and often considers it a part of Americana38. Similarly, "Guggisberglied” by Christine Lauterburg and Doppelbock is deeply rooted in Swiss folk traditions and is often performed in communal settings, encouraging active audience participation and storytelling that connects the community to their shared heritage, thus reinforcing the communal nature of the song. “Guggusberglied” was used as the control stimulus in this study because, although communal in Swiss culture, it was not culturally relevant for the sample of US participants. The audio versions of the materials used in the study are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Measures

In addition to providing demographic information (age, gender, Latino/Hispanic status, race/ethnicity, and employment status), participants reported on their musical training (in years) and completed the Symptom Checklist 27 Plus (SCL-27)39 and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory-5 (STAI-5)40. Participants also completed positive affect and negative affect questionnaires.

Symptom checklist – 27 plus

The Symptom Checklist 27 Plus (SCL-27)39 is a short screening questionnaire that provides a general severity index (GSI) of clinical symptoms. Respondents were asked about depressive, vegetative, agoraphobic, sociophobic, and pain symptoms in addition to other concerns (e.g., headaches, fear of saying something embarrassing, hopelessness). Symptoms are rated according to the frequency with which they occur on a scale ranging from never (0) to very often (4). The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) in our sample was excellent to satisfactory (GSI, 24 items α = 0.92; subscales: depressive, 5 items α = 0.84, vegetative, 5 items α = 0.78, agoraphobic, 4 items α = 0.83, sociophobic, 5 items α = 0.91, pain, 5 items α = 0.76).

State-trait anxiety inventory–5 (STAI-5)

The STAI-540 is a five-item questionnaire that measures state anxiety using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (1) to very much so (4). The STAI-5 scale has shown excellent reliability and internal consistency40. In our sample, good internal consistency was found for both pre- and post-assessments (Pre α = 0.83; Post α = 0.81).

Positive affect

To measure positive affect, participants were asked the following questions: (i. PA) how happy/positive do you feel at the moment?; (ii. PA) How excited/motivated do you feel at the moment?; (iii. PA) How connected to others do you feel at the moment?; and (iv. PA) How much in tune with yourself and your emotions do you feel at the moment? The questions were presented on a visual analog scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely), and participants responded using a slider. All items loaded into the same factor (see Figure S1), with good and excellent internal consistency (4 items; Pre α = 0.89; Post α = 0.90).

Negative affect

To measure negative affect, the following questions were asked: (i.e., NA) how sad/negative do you feel at the moment?; (ii. NA) How anxious do you feel at the moment? and (iii.) NA) How self-conscious do you feel at the moment? Similar to positive affect, questions were presented with a visual analog scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). The items also loaded into the same factor (Fig. S1), with satisfactory internal consistency (3 items; Pre α = 0.75; Post α = 0.76). Questions for positive and negative affect were presented as a block.

Social ostracism manipulation and evaluation

The social media ostracism paradigm (SMOP) was used to induce social exclusion41. In brief, participants were asked to create a nickname, choose an avatar, and write a bio to be shared with other people with whom they believed they would be connected to next. Once their profile was complete, participants had three minutes to interact with other preprogrammed profiles. Participants were informed that they could like as many profiles as they wanted and that their profile would also be shown to the other participants, who would be able to like their profiles as well. They were informed that there were no limits to the number of likes they could distribute. Ostracism consisted of the participant receiving only one such like, while other profiles received more (2–9 likes). Previous research has shown that the SMOP is suitable for online data collection and is considered effective in inducing feelings and thoughts of social exclusion41. A sample of the exclusion condition can be found at http://smpo.github.io/socialmedia/. To check the effect of the social ostracism manipulation, participants were asked to respond about their feelings and thoughts during the SMOP (see Table S2 for details), as in Wolf, Levordashka41. SMOP scores ranged from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The internal consistency scores for SMOP feelings (5 items; α = 0.86) and SMOP thoughts (3 items; α = 0.86) in our sample were good.

Procedure

The present protocol was approved by the Harvard University-Area Committee on the Use of Human Subjects (IRB21-1685). All data collection for this study was performed online and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants digitally signed informed consent. After providing demographic information and completing the SCL-27, participants completed the STAI-5, positive affect, and negative affect measures in a randomized order (Pre, T1). They were then directed to the SMOP. Immediately following the SMOP, participants were randomly assigned to the communal or control condition. The communal condition consisted of the audio presentation of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” Virtual Choir. For the control condition, participants listened to “Guggisberglied” by Christine Lauterburg and Doppelbock. The control song was in German. The musical stimulus was played for 2 min 21 s. Following the music, participants were asked to complete the positive affect, negative affect, and the STAI scales, once again in a randomized order (Post, T2). Participants rated their familiarity with the music they had listened to and were debriefed on the study objectives following completion of the SMOP feelings and SMOP thoughts. See Fig. 1.

Statistical analyses

Demographic

Given the non-normal distribution of our data, Mann‒Whitney U tests were used for between-group comparisons for continuous measures (age, musical training, SCL-27, SMOP feelings, SMOP thoughts) and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical measures (gender, Latinx/Hispanic, ethnicity, and employment status).

Main analyses

To investigate the effects of communal music on affect, we fit linear regression models using the Post (T2) affect scores (positive affect; negative affect) as the dependent variable and condition (communal; control) as the independent variable controlling for Pre (T1) affect scores. Both T1 and T2 affect measures were log-transformed to address issues of non-normality and heteroscedasticity. We then used the anova function to generate F statistics and p values. Partial η2 were calculated using the eta_squared function (effectsize package) in R. Due to the impossibility of log-transformed state anxiety values (due to the presence of zeros), we calculated a change score (scoreT2 – scoreT1) for the state anxiety measure. The choice for this measure was based on our main hypothesis that communal music would reduce the change compared to the control condition. Furthermore, no between-group differences were found in the baseline (T1) scores. Given the non-normal distribution of the data, Mann‒Whitney U tests were used for state anxiety group comparisons.

Follow-up analyses

We used Spearman’s correlations (non-normal distribution) to examine the relationship between affect change and familiarity with the music presented for significant between-group findings. These correlations were performed for the whole sample and at the group level. Finally, to explore whether characteristics of music other than its communal component (including language) influenced our findings, we repeated the analysis in a subset of native English-speaking individuals who reported not being baseball fans and never having attended a live baseball game. Given that the control song was in a foreign language, we repeated the same procedure as well as the analysis that was found to be significant in our main sample in a subset of native English-speaking individuals. These individuals were recruited separately and had declared that they were not baseball fans and had never attended a live game (n = 44; 23 = communal, 21 = control; see Table S3 for details).

Results

Details for demographic and other measures can be found in Table 1. There were no significant differences between groups for age, gender (although this approached significance, p = 0.059), Latino/Hispanic ethnicity, employment status, or musical training (all p values > 0.05). Similarly, no significant difference was found between groups for depressive symptoms (p = 0.817), vegetative symptoms (p = 0.663), agoraphobic symptoms (p = 0.507), sociophobic symptoms (p = 0.972), pain symptoms (p = 0.622) or GSI (p = 0.967) measured by the SCL-27.

No significant differences were found between groups for SMOP feelings (Mdn communal = 3.4; Mdn control = 2.8; W = 1501, p = 0.534) or SMOP thoughts (Mdn communal = 3.6; Mdn control = 3.3; W = 1479, p = 0.629). In summary, both groups exhibited comparable moderate effects from ostracism, with no significant differences observed between them (Table S2).

Main analyses

We found a significant difference between conditions across time for positive affect (F(1, 103) = 8.667, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.08). In other words, while self-reported positive affect significantly decreased following SMOP (T2) for the control group, it remained relatively unchanged for the communal music group. No significant difference was found for changes in negative affect (F(1,92) = 0.114, p = 0.7362) or state anxiety (both groups Mdn = 0, p = 0.988). See Table 2 for descriptive information and Fig. 2 for more details.

Follow-up analyses. We did not find a significant correlation between familiarity and change in positive affect (r(104) = 0.15, p = 0.13; r(49) communal = -0.12, p = 0.41; r(53) control = -0.06, p = 0.65; Fig. S2).

Study 2

Materials and methods

Participant recruitment and song selection

As in study 1, individuals who reported being baseball fans were invited to complete a screening form through Prolific. Individuals who reported having attended a live baseball game in a stadium (n = 157) were subsequently invited to participate in the main study, which, again, was presented to them as a separate project. Of those who completed the survey (n = 143), two individuals failed the attention checks included in the study and were subsequently excluded from the analyses. We also added a question to determine whether the songs included in the study either had been experienced in a communal setting or not within the past year. More specifically, participants were asked, “how many times did you experience the song you listened to in a communal setting in the past year?”. Participants who reported not having experienced the communal stimulus (n = 13) or who reported experiencing the control stimulus (n = 12) in a communal setting were further excluded from the study. The final sample consisted of 116 participants (see Table 2 for details).

Experimental and control songs

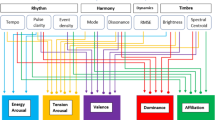

An alternative version of "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" served as the communal stimulus, while "In the Good Old Summertime" was used as the control stimulus, both performed by The Andrews Sisters. These selections enhanced the previous study by enabling control over various musical elements that could influence emotional response, such as affect type, tempo, metric signature, language, and arrangement, as these characteristics have the potential to modulate affect42,43. For more details on the stimuli used in this study, please refer to the Supplemental Materials.

Measures

The same demographic measures reported in study 1 were collected. Similarly, SCL-27 (Hardt, 2008) was collected. The SCL-27 internal consistency ranged from excellent to satisfactory (GSI, 24 items α = 0.92; subscales: depressive, 5 items α = 0.87, vegetative, 5 items α = 0.76, agoraphobic, 4 items α = 0.88, sociophobic, 5 items α = 0.87, pain, 5 items α = 0.72). Since no significant differences were found between groups for STAI in study 1, this measure was not included in study 2.

Positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS)

In study 2, the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)44 was used to measure affect. The PANAS is a well-validated tool that includes items that assess both positive (i.e., interested, excited, strong, enthusiastic, proud, alert, inspired, determined, attentive, and active) and negative (i.e., distressed, upset, guilty, scared, hostile, irritable, ashamed, nervous, jittery, and afraid) emotions. Items range from Very slightly or not at all (0) to Extremely (4). Internal validity for both scales (positive, 10 items; negative, 10 items) was excellent in every time point (all α > 0.90).

Modified general belongingness scale (Mod-GBS)

To assess how much belonging individuals felt while listening to the respective musical stimulus, we included a modified version of the General Belongingness Scale45. In the present version, we prompted participants to “think about the song [they] listened to” and respond how they felt “while listening to the music played.” Items ranged from Strongly disagree (0) to Strongly disagree (6) and included statements like “While listening to the music played, I felt included,” “I was reminded of close bonds with family and friends,” “I felt like an outsider,” and “I was reminded of people who care about me (Fig. 3).” Cronbach’s alpha for the Mod-GBS Belonging scale (9 items) was excellent (α = 0.94).

Music affect

Similarly to Mod-GBS, we included 5 questions assessing the affect associated with the musical stimulus presented. We included the following statements: “While listening to the music played, I had positive feelings,” “I felt sad,” “I felt like I had a smile on my face,” “I felt a sense of content,” and “I was reminded of positive memories”. Items also ranged from Strongly disagree (0) to Strongly agree (6) and were highly internally consistent (α = 0.92).

Nostalgia

We further assessed whether the nostalgia brought up by the songs differed between groups. Since this measure was included following reviewers’ suggestions, no specific inventory was used. Instead, we selected items from the Mod-GBS and the Music affect scale that included the expressions “I was reminded of…” Items also ranged from Strongly disagree (0) to Strongly agree (6), and, as in the previous measures, our measure for nostalgia had excellent internal consistency (α = 0.92). See Fig. 3 for a full list of the items included in all three scales.

Negative autobiographical memory recollection task

To induce negative mood and remind them of a time their belonging to a group was at risk, we asked participants to complete a writing task that involved recalling a negative autobiographical memory. As in Allen and Hooley46, participants were asked to “write a short paragraph about a time in [their] life when [they] felt worthless, failed to meet the expectations of someone important to [them], and/or a source of shame.” Participants had a least 5 min to reflect and complete the writing task.

Procedure

After signing the consent form, participants provided demographic information, completed the SCL-27, and then the PANAS (Baseline, T1). Next, they completed the negative autobiographical memory recollection task and the PANAS again (post induction, T2). The inclusion of the PANAS here aimed to address a methodological issue from study 1 (i.e., the absence of a tool to evaluate the effects of the mood manipulation task). They were then randomly assigned to either the communal condition (listening to "Take Me Out to the Ballgame") or the control condition (listening to "In the Good Old Summertime"). Each song lasted 2 min, and participants could not advance in the survey until the song ended. Afterward, they completed the PANAS a final time (post music exposure, T3). Finally, participants completed the Mod-GBS and Music affect questionnaires and were debriefed about the experiment.

Statistical analyses

Measures

Between-group comparisons for continuous measures were done via Mann–Whitney-Wilcox (for non-normally distributed data) or Welch’s t-test (for normally distributed data) and chi-square (categorical variables).

Main analyses

To investigate the effects of communal music on affect, we fit linear mixed models using PANAS scores (positive affect; negative affect) as dependent variables and the interaction of condition (communal; control) and time [baseline (T1); post mood induction (T2); post music exposure (T3)] as fixed effects. Subject was treated as a random effect. We also explored between-group differences in GBS-mod, Music Affect, and Nostalgia scores fitting three separate linear models and using the anova function to generate F statistics. The eta_square function was used to generate effect sizes when appropriate. Every model resulting in significant findings was repeated including the variables that were found to be significantly different between groups (i.e., age and pain symptoms) as covariates. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05 for every test in both studies.

Mediation analysis

We ran a mediation analysis exploring the role of sense of belonging (Mod-GBS) as a mediator between change scores in positive affect and condition (communal vs control). Change scores for positive affect (scoreT3 – scoreT1) were created. The relationship between the condition and change in positive affect was evaluated using linear regression. To explore the indirect effects of the condition on positive affect change, a mediation analysis was conducted including sense of belonging (GBS-mod) as a mediator. To assess the significance and estimate the confidence intervals of the indirect effects, a bootstrapping method was employed using the mediation package in R. Specifically, effects were computed for each of the 5,000 bootstrapped samples.

Follow-up analyses

We used Pearson’s correlations to examine the relationship between affect change and feelings of belonging associated with the music (GBS-mod). We explored the role of belonging in improving affect in the whole sample and by group. Finally, as in study 1, we examined the relationship between change in positive affect and familiarity as well as change in positive affect and nostalgia with the music listened to.

Results

Details for demographic and other measures can be found in Table 3. There was a significant difference between groups for age (p = 0.014) and pain symptoms (p = 0.018). No other differences were found between groups for demographics and SCL-27 measures.

Main analyses

We found a significant effect of time (p = 0.030) and the interaction time * condition (p = 0.022) for positive affect. As expected, positive affect significantly decreased, independently of condition, following the negative autobiographical memory recollection, suggesting that the mood induction was successful in worsening affect (b = -0.18). Furthermore, individuals in the control condition showed significantly lower positive affect compared to those in the communal condition post music exposure (T3; b = -0.27). In other words, listening to the communal music significantly improved positive affect, while listening to a positive affect song with similar musical arrangements did not. See Fig. 4 for means and standard deviations. Further details can be found in Table 4. The inclusion of the covariates (age and pain symptoms) in the model did not alter the result (See Table S4).

Study 2. Positive affect across time points by condition. Positive affect significantly decreased following the negative autobiographical memory recollection task for both groups (T2). Participants in the communal condition reported a significant increase in positive affect following the music (T3), while no improvement was seen for those in the control condition.

We also found a significant between-group difference for sense of belonging measured in response to the musical stimulus (GBS-mod; F(1, 114) = 5.054, p = 0.026, η2 = 0.04). Individuals in the communal condition reported higher sense of belonging (M = 4.22, SD = 1.22) than those in the control condition (M = 3.71, SD = 1.24). Once again, the inclusion of age and pain symptoms as covariates did not alter the result (Table S5). Music induced feelings (music affect) did not significantly differ between groups (F(1, 114) = 3.63, p = 0.059), although there was a trend for increased positive feelings in the communal group. Finally, although a trend was found (p = 0.081), the songs did not significantly differ in levels of nostalgia (F(1, 114) = 3.08, p = 0.081).

Mediation analysis

The effect of the condition on positive affect change was mediated by sense of belonging (GBS-mod). The bootstrapped indirect effect was 0.07 (CI = 0.01; 0.16), p = 0.026. Figure 5 shows the coefficients.

Follow-up analyses

In the entire sample, we found a significant correlation between the sense of belonging associated with the music (GBS-mod) and change in positive affect (r(114) = 0.36, p < 0.001). When looking at the group level, this correlation was more significant for the communal (r(54) = 0.45, p < 0.001) than the control (r(58) = 0.23, p = 0.077) condition. See Fig. 6 for details. A significant correlation was found between positive affect change and familiarity (r(114) = 0.24, p = 0.011) for the whole sample. However, at the group level, familiarity was not significantly correlated with change in positive affect for the communal (r(54) = 0.09, p = 0.49) nor the control (r(58) = 0.05, p = 0.71) condition (Fig. 7). Finally, a significant relationship between positive affect change and nostalgia was found for the whole (r(114) = 0.40, p < 0.001) and for both groups (communal r(54) = 0.40, p = 0.002; control r(58) = 0.27, p = 0.034)). See Fig. 8 for details.

Negative affect

There was a significant effect of time for negative affect (p < 0.001). Negative affect post-induction (T2) was significantly higher compared to the baseline (T1), suggesting, once again, that the mood induction was successful in worsening mood. No further effects were found. See Table 5 for details.

Discussion

The present research explores the potential of communal music exposure as a means to improve affect in the context of social ostracism or negative mood associated with disappointing others. Our findings suggest that simply listening to communal music, i.e., music previously experienced in a communal setting and leading to an increase in sense of belonging, has the capacity to mitigate (study 1) or repair (study 2) the decline in positive affect typically associated with social exclusion and negative mood, as observed in our control groups. Partially confirming our initial hypothesis, individuals who listened to communal music following the social ostracism or negative mood induction tasks reported higher levels of positive affect compared with those who listened to non-communal music. Interestingly, the participants who were exposed to music without communal associations actually experienced a decline in positive affect, a trend which was not noted in the communal music group. Notably, this effect was evident after brief exposures of roughly two minutes. Furthermore, sense of belonging in connection to the music listened to was significantly higher in the communal vs control condition and mediated the relationship between condition and change in positive affect, while the affect of the song (i.e., how positive it sounded) and levels of nostalgia did not significantly differ between conditions. It is essential to emphasize that, as expected, feelings of exclusion during the social media ostracism paradigm (study 1) as well as global psychopathology symptoms measured by the SCL-27 (studies 1 and 2) did not generally differ between groups.

Communal music may differentially improve positive affect compared to other types of music. While familiar and preferred music impacts wellbeing markers in different samples19,22, our findings suggest that communal music’s impact might extend beyond mere recognition and preference. Although we did not ask participants to indicate their music preferences, it is very unlikely that the findings are associated with preferences. In other words, it is unlikely that the stimulus used (“Take me Out to the Ballgame”) is the group’s favorite song. Furthermore, while familiarity was high in the experimental group and low in the control group (study 1), there was no significant association between familiarity ratings and change scores in general or for either group. In study 2, familiarity correlated with change in affect across the entire sample, however, group level analyses revealed no significant correlations between change in positive affect and familiarity, suggesting that other characteristics of the music were driving the effects found.

These findings are likely not due to music characteristics present in one song but not the other. Research has shown, for instance, that timbre (i.e., the identity of a sound), mode (i.e., major/minor), and tempo (fast/slow) differentially modulate emotions42,47,48. For example, major-mode and fast-tempo songs tend to be associated with happiness, which, in turn, could impact how people perceive and report their own emotions18. In study 2, we purposefully included a song with similar characteristics of the communal stimulus (i.e., same mode, similar tempo, similar arrangement, same vocal timbre and harmony, etc.) as the control song, and the results remained similar to those found in study 1. Moreover, the nostalgia felt while listening to the song does not fully explain the group differences. The control song is study 2, as the experimental song, also contained lyrics that evoked nostalgia (in the good old summertime), and group comparisons were not significantly different. Furthermore, as expected, follow up analyses revealed a significant relationship between positive affect change and nostalgia for the whole sample and both groups, strengthening the idea that the levels of nostalgia did not differ between groups. Finally, while nostalgia seems to be one aspect that differentially increase sense of belonging25, our results suggest that communality adds to that.

Sense of belonging experienced while listening to the song may explain the boost in positive affect. Participants in the communal music condition reported a higher sense of belonging than those in the control condition, while positive affect associated with the music and nostalgia was less significant. Furthermore, our model revealed that sense of belonging significantly mediated the relationship between the condition and changes in positive affect. Given that a wide base of research has suggested that people’s sense of being a member of a specific group can be primed and re-activated through environmental cues49,50, our findings suggest that re-exposure to communal music acts as a cue that activates the sense of belonging leading to affect preservation or repair, both in the case of externally driven or internally driven negative affect. This finding aligns with previous research that posits that the sense of belonging to a group and feelings of connectedness can provide emotional support and buffer against stress2,51,52, even when experienced in an individual context53. Additionally, the effects of communal music may be partially explained by the theory of social surrogacy, wherein music acts as a substitute of the community where the social connections and shared experiences took place. For example, individually listening to church music may not only deepen a person’s spiritual engagement but also foster a sense of belonging by evoking feelings of belonging to their religious community.

The demonstrated ability of communal music to boost positive affect warrants further study because research supports the idea that boosting positive affect in times of distress is protective.2 For example, Cohn, Fredrickson54 demonstrated that positive emotions predict resilience and overall life satisfaction, even when concurrent negative emotions are present. Similarly, Fredrickson, Tugade55 found that the experience of positive emotions after the 9/11 tragedies mediated both the relationship between pre-crisis resilience and post-crisis growth and reduced depressive symptoms. These findings are further supported by Tugade, Fredrickson56, who showed that positive affect mediated the relationship between trait resilience and reduced cardiovascular reactivity during stress, and Ong, Bergeman57, who observed that high levels of positive affect aid recovery from stressful life events, even amidst increased negative affect. Future research leveraging communal music interventions is needed to evaluate whether the immediate boost in positive affect observed in our study may have longer-term impacts, especially when participants have repeated exposures to communally experienced music.

The potential for communal music to boost participants’ acute sense of belonging may also have important implications. Ones’ sense of belonging—or social identification with a group—is considered to be one crucial determinant of mental health2. For this reason, it is important that future studies evaluating the efficacy of music-based interventions over time consider whether communally experienced music offers unique benefits for participants because of the social context in which it is produced. Research informed by the social identity approach to health underscores that identifying with a social group can reduce depression58, buffer against stress during life transitions59, alleviate posttraumatic stress symptoms60, and reduce burnout while enhancing workplace well-being61.

The integration of these two constructs—positive affect and sense of belonging—is particularly compelling. Positive affect not only promotes resilience and recovery but may also enhance the capacity for individuals to connect and engage socially, reinforcing their sense of belonging. Conversely, a strong sense of belonging within a social group creates conditions that foster and sustain positive affect. Communal music exposure offers a unique and promising avenue to address both these dimensions simultaneously, strengthening social bonds and group identification. This dual impact may make it a valuable tool for improving mental health outcomes, even in contexts of heightened stress or adversity, and warrants further exploration.

Our findings offer promising insights into the potential effects of communal music on emotional wellbeing. However, to build a more comprehensive understanding, further research is critical. First, it is essential to continue exploring the interplay between familiar and communal musical characteristics and their differential effects on mood and affect. Understanding how these aspects interact to influence mood and affect can offer valuable insights into the mechanisms at play. Second, it is important to explore a broader range of types of communal music, encompassing different genres, cultural origins, and contexts. This diversity will help clarify the generalizability of our findings and determine whether certain types of communal music are more effective in particular scenarios. Third, it is possible that, while designed to be a mostly receptive task (i.e., simply listening to the music piece), the nature of communal music may lead individuals to sing along with the song, and this relationship should be further explored. Future research may also evaluate whether communal associations with music can be formed during music interventions among people who do not have strong pre-existing ties to certain identity groups—as these isolated or disconnected groups may be at highest risk of negative mental health outcomes. Another promising area of research involves the exploration of the relationships among communal music, memory, and affect. Investigating how communal music evokes collective memories and how these memories, in turn, influence mood and emotional states can offer profound insights into the intricate interplay between music, memory, and emotion. Similarly, exploring the role of identity recollection when experiencing communal music may lead to interesting findings. Finally, it would be relevant to examine the beneficial qualities of communal music against various mood induction methods and instruments.

Lastly, this study is not without limitations. First, our study focused exclusively on baseball fans. Broadening the participant pool (both in terms of sample size and community where they are drawn from) would enhance the generalizability of our findings and further clarify the role of communal music on affect, specifically disentangling the effects found here from the sports context. Second, as this was a first attempt to study the concept of communal music and its potential as a tool to improve affect, we only included a positive communal stimulus. Future studies should test other types of communal music, including those that are experienced in negative contexts, such as funerals, where levels of valence and arousal differ. We expect that even in these contexts, similar findings will emerge (sad music would likely also lead to a decrease in negative affect as shown by Blasco-Magraner, Bernabé-Valero13 and this could potentially be one of the reasons we did not find significant differences in negative affect in the present study). In study 1 we collected information on the participants’ preferred baseball teams, and, using data freely available on the Major League Baseball website on wins and losses in 2022 (when study 1 data was collected), we were able to calculate percentage of wins for the teams represented in our sample. These ranged from 0.37 to 0.686, with no significant difference between groups (see Table S6 for more details). Although we did not ask participants whether their teams had won or lost the times they attended a live game, it is very unlikely that participants had only attended wins (percentage wins average was approximately 0.5 for both conditions). Because sports games elicit a wide range of emotions which are based on outcomes—with fans of winning teams typically experiencing higher levels of excitement and gratitude, while fans of losing teams report higher levels of boredom, anger, and resentment even before the end of the match62—we consider this context ideal for the pilot nature of the present study. Building on this initial exploration of communal music’s impact, future studies may investigate how different musical styles and contexts interact to influence feelings of belonging and affect. Third, the measures of sense of belonging, affect associated with the music, and nostalgia need further validation. Even though they were adapted from an existing validated questionnaire (the General Belongingness Scale)45, studies exploring this measure associated with a specific situation (in this case, the music) would advance the studies on the topic. Furthermore, the scale used to measure nostalgia was created a posteriori following reviewers’ comments and may address factors not explored in other studies investigating the construct. Fourth, a more balanced sample in terms of sex and gender would improve generalizability. Our sample mostly consisted of males, which, given the nature of the present study and the population recruited, was expected (e.g., mostly men report attending baseball games63). Lastly, future studies should compare the effects of communal music interventions with other, non-communal music interventions over time. While our research demonstrated an acute boost in feelings of belonging and positive affect following communal music exposure, longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate whether these changes ultimately impact mental health, especially given repeated exposures to communal music.

Conclusion

This study investigated the potential of communal music exposure to counteract the consequences of social ostracism and negative autobiographical memory recollection. Our findings suggest that briefly listening to communal music, i.e., songs often experienced in collective environments, can mitigate the decline in positive affect triggered by social exclusion and negative mood. Individuals exposed to communal music maintained relatively stable or increased positive affect levels after experiencing social exclusion and negative mood, while those exposed to control music experienced a decline in positive affect. Change in affect was mediated by sense of belonging evoked by the music listened to. These findings are promising, as this is the first study, to our knowledge, to suggest that simply listening to a communally experienced song has the potential to improve positive mood following social media ostracism paradigm or the induction of a negative mood state.

Data availability

All data, analysis codes, and research materials are available at https://osf.io/yxn28/?view_only=4afa1499d6324c939ac0e4683524a772.

References

Over Zero and The American Immigration Council, The belonging barometer: The state of belonging in America. (2024).

Wickramaratne, P. J. et al. Social connectedness as a determinant of mental health: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 17(10), e0275004 (2022).

Golden, T. L. et al. The Use of Music in the Treatment and Management of Serious Mental Illness: A Global Scoping Review of the Literature. Front Psychol 12, 649840 (2021).

Perkins, R. & Williamon, A. Learning to make music in older adulthood: A mixed-methods exploration of impacts on wellbeing. Psychol. Music 42(4), 550–567 (2014).

Seinfeld, S. et al. Influence of Music on Anxiety Induced by Fear of Heights in Virtual Reality. Front Psychol. 6, 1969 (2015).

Knapp, D. H. & Silva, C. The Shelter Band: Homelessness, social support and self-esteem in a community music partnership. Inter. J. Commun. Music 12(2), 229–247 (2019).

Wilson, G. B. & MacDonald, R. A. R. The Social Impact of Musical Engagement for Young Adults With Learning Difficulties: A Qualitative Study. Front Psychol. 10, 1300 (2019).

Dingle, G. A. et al. How Do Music Activities Affect Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review of Studies Examining Psychosocial Mechanisms. Front Psychol. 12, 713818 (2021).

Gomez-Gallego, M., et al., Comparative Efficacy of Active Group Music Intervention versus Group Music Listening in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021. 18(15).

Ihara, E. S. et al. Results from a person-centered music intervention for individuals living with dementia. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 19(1), 30–34 (2019).

Sarkamo, T. et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 54(4), 634–650 (2014).

Chong, H. J., Kim, H. J. & Kim, B. Scoping Review on the Use of Music for Emotion Regulation. Behav. Sci. 14(9), 793 (2024).

Blasco-Magraner, J. S. et al. Changing positive and negative affects through music experiences: a study with university students. BMC Psychol. 11(1), 76 (2023).

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M. & Hellhammer, D. H. The ’Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28(1–2), 76–81 (1993).

Groarke, J. M. et al. Does Listening to Music Regulate Negative Affect in a Stressful Situation? Examining the Effects of Self-Selected and Researcher-Selected Music Using Both Silent and Active Controls. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 12(2), 288–311 (2020).

Feneberg, A. C. et al. Perceptions of stress and mood associated with listening to music in daily life during the COVID-19 lockdown. JAMA Netw. Open 6(1), e2250382–e2250382 (2023).

Granot, R. et al. “Help! I need somebody”: music as a global resource for obtaining wellbeing goals in times of crisis. Front. Psychol. 12, 648013 (2021).

Juslin, P. N. & Laukka, P. Expression, Perception, and Induction of Musical Emotions: A Review and a Questionnaire Study of Everyday Listening. Journal of New Music Research 33(3), 217–238 (2004).

Blood, A. J. & Zatorre, R. J. Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 98(20), 11818–11823 (2001).

Ferreri, L. et al. Dopamine modulates the reward experiences elicited by music. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 116(9), 3793–3798 (2019).

Ferreri, L., et al., Dopamine modulations of reward-driven music memory consolidation. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci., (2021).

Fischer, C. E. et al. Long-Known Music Exposure Effects on Brain Imaging and Cognition in Early-Stage Cognitive Decline: A Pilot Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 84(2), 819–833 (2021).

Pereira, C. S. et al. Music and emotions in the brain: familiarity matters. PLoS ONE 6(11), e27241 (2011).

van den Bosch, I., Salimpoor, V. N. & Zatorre, R. J. Familiarity mediates the relationship between emotional arousal and pleasure during music listening. Front Hum. Neurosci. 7, 534 (2013).

Sedikides, C., Leunissen, J. & Wildschut, T. The psychological benefits of music-evoked nostalgia. Psychol. Music 50(6), 2044–2062 (2022).

Batcho, K. I. Nostalgia and the Emotional Tone and Content of Song Lyrics. Am. J. Psychol. 120(3), 361–381 (2007).

Tremblay, L., Worbe, Y. & Hollerman, J. R. Chapter 3 - The ventral striatum: a heterogeneous structure involved in reward processing, motivation, and decision-making. In Handbook of Reward and Decision Making (eds Dreher, J.-C. & Tremblay, L.) 51–77 (Academic Press, 2009).

Bernatzky, G. et al. Emotional foundations of music as a non-pharmacological pain management tool in modern medicine. Neurosci Biobehav. Rev. 35(9), 1989–1999 (2011).

Dunbar, R. I. M. et al. Performance of Music Elevates Pain Threshold and Positive Affect: Implications for the Evolutionary Function of Music. Evol. Psychol. 10(4), 147470491201000420 (2012).

Boer, D. & Abubakar, A. Music listening in families and peer groups: benefits for young people’s social cohesion and emotional well-being across four cultures. Front. Psychol. 5, 392 (2014).

Schäfer, K. & Eerola, T. How listening to music and engagement with other media provide a sense of belonging: An exploratory study of social surrogacy. Psychol. Music 48(2), 232–251 (2020).

Groarke, J. M. et al. Music Listening Was an Emotional Resource and Social Surrogate for Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Behav. Chang. 39(3), 168–179 (2022).

Leary, M. R. et al. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68(3), 518–530 (1995).

Wesselmann, E. D. et al. Social Exclusion in Everyday Life. In Social Exclusion: Psychological Approaches to Understanding and Reducing Its Impact (eds Riva, P. & Eck, J.) 3–23 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Elenbaas, L. & Killen, M. Research in Developmental Psychology: Social Exclusion Among Children and Adolescents. In Social Exclusion: Psychological Approaches to Understanding and Reducing Its Impact (eds Riva, P. & Eck, J.) 89–108 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Huron, D. Is music an evolutionary adaptation?. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 930, 43–61 (2001).

Appelbaum, M. et al. Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am. Psychol. 73(1), 3 (2018).

Library of Congress, Take me Out to the Ball Game.

Hardt, J., The symptom checklist-27-plus (SCL-27-plus): a modern conceptualization of a traditional screening instrument. Psychosoc Med, 2008. 5: p. Doc08.

Zsido, A. N. et al. Development of the short version of the spielberger state-trait anxiety inventory. Psychiatry Res. 291, 113223 (2020).

Wolf, W. et al. Ostracism Online: A social media ostracism paradigm. Behav. Res. Methods 47, 361–373 (2015).

Hailstone, J. C. et al. It’s not what you play, it’s how you play it: timbre affects perception of emotion in music. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Hove) 62(11), 2141–2155 (2009).

Ribeiro, F. S. et al. Emotional Induction Through Music: Measuring Cardiac and Electrodermal Responses of Emotional States and Their Persistence. Front Psychol. 10, 451 (2019).

Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 47, 1063–1070 (1988).

Malone, G. P., Pillow, D. R. & Osman, A. The General Belongingness Scale (GBS): Assessing achieved belongingness. Personality Individ. Differ. 52(3), 311–316 (2012).

Allen, K. J. & Hooley, J. M. Negative mood and interference control in nonsuicidal self-injury. Compr Psychiatry 73, 35–42 (2017).

Hunter, P.G. and E.G. Schellenberg, Music and emotion. Music perception, 2010: p. 129–164.

Koelsch, S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15(3), 170–180 (2014).

Shih, M., Pittinsky, T. L. & Ambady, N. Stereotype susceptibility: Identity salience and shifts in quantitative performance. Psychol. Sci. 10(1), 80–83 (1999).

Steele, C. M. & Aronson, J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 69(5), 797 (1995).

Abrams, D. Social Identity, Psychology of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (eds Smelser, N. J. & Baltes, P. B.) 14306–14309 (Pergamon, 2001).

Cohen, S. & Wills, T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98(2), 310 (1985).

Ghaffari, M., et al., The impact of COVID-19 on online music listening behaviors in light of listeners’ social interactions. Multimedia Tools Applications, (2023).

Cohn, M. A. et al. Happiness unpacked: positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion 9(3), 361 (2009).

Fredrickson, B. L. et al. What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84(2), 365 (2003).

Tugade, M.M., B.L. Fredrickson, and L. Feldman Barrett, Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. J. personal. 72(6): p. 1161–1190. (2004).

Ong, A. D. et al. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91(4), 730 (2006).

Sani, F. et al. Comparing social contact and group identification as predictors of mental health. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 51(4), 781–790 (2012).

Iyer, A. et al. The more (and the more compatible) the merrier: Multiple group memberships and identity compatibility as predictors of adjustment after life transitions. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 48(4), 707–733 (2009).

Muldoon, O. T. & Downes, C. Social identification and post-traumatic stress symptoms in post-conflict Northern Ireland. Br. J. Psychiatry 191(2), 146–149 (2007).

Avanzi, L. et al. Why does organizational identification relate to reduced employee burnout? The mediating influence of social support and collective efficacy. Work Stress. 29(1), 1–10 (2015).

Kerr, J. H. et al. Emotional dynamics of soccer fans at winning and losing games. Personality Individ. Differ. 38(8), 1855–1866 (2005).

Sports Business Research, N. and Statista, Share of MLB fans by gender US 2024: Share of respondents who attended or watched MLB games in the United States as of January 2024, by gender. (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the Hooley Laboratory for their invaluable input, especially Timothy Valshtein, Chelsea Boccagno, and Ellen Finch, as well as Craig McDonald.

Funding

Talley Fund, Department of Psychology, Harvard University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P., D.W.S., and J.H. designed the study. M.P. and D.W.S. performed the experiments. M.P. and S.H. analyzed the data. M.P. and J.H. obtained funding. All authors wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Piccolo, M., dos Santos, D.W., Herold, S. et al. Communal music as a tool to improve positive affect after social ostracism or negative autobiographical memory recollection. Sci Rep 15, 33821 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05119-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05119-5