Abstract

The heat treatment process is a key technology to improve the performance of cast aluminum-copper alloys with micro-nano boron nitride (BN) particles, but its strengthening mechanism still needs to be studied. Orthogonal tests were used to carry out heat treatment experiments on aluminum matrix ceramic composites prepared by adding different contents of micro-nano BN particles. Then, a crystal model was established, and the heat treatment process was simulated by the molecular dynamics (MD) method. The heat treatment results show that the mechanical strength and elongation of the nano-BN/aluminum matrix composites with a content of “2%” are significantly increased (9.52% and 23.28%) after heat treatment with a solution temperature of 545 °C, a solution duration of 9 h, an aging temperature of 150 °C and an aging of 8 h. The stress calculation results based on MD are also consistent with the experimental conclusions. The results of microstructure and MD calculations show that the micro/nano BN particles would promote the rearrangement of the lattice and make other lattice types transform to the hexagonal close-packed (HCP) phase during heat treatment, which would be enforced the grain boundaries of the alloy, hindered the movement and diffusion of dislocations, reduced the formation of dislocation defect surfaces, and improved the tensile strength and hardness of the alloy. At the same time, the recrystallization of heat treatment causes the dislocations to undergo cross-slip and lattice rotation in the process of plane slip, resulting in the annihilation of multiple groups of dislocations due to interaction, which makes the plasticity of the material slightly decrease. The coexistence of the residual face-centered cubic phase and the HCP phase in the internal structure makes the composite material have a good balance of strength, hardness and ductility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aluminum alloys and boron nitride (BN) materials occupy a pivotal position in modern materials science and engineering technology. Aluminum alloys, as outstanding representatives of metal materials, are an important achievement of mankind in the pursuit of lightweight and high-strength materials, and have demonstrated unparalleled advantages in casting1,2, and therefore many innovative studies have been conducted on processing methods and other aspects3,4,5,6. Boron nitride, on the other hand, with its unique physical and chemical properties, has shown great potential in the fields of superhard materials, high-temperature ceramics, and electronic devices, and has become one of the hot spots in materials science research7,8,9.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, since Balmain10 discovered that unstable boron nitride was synthesized by combining molten boric acid and potassium cyanide, the preparation, characterization, and application of boron nitride became a hot spot for early research. For example, Wentorf et al.11 prepared P-type and N-type semiconductor crystals of cubic boron nitride (cBN) by adding lithium or magnesium nitride to hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) at high temperatures and high pressures. It found that the diffusion of the additives in c-BN crystals was not as fast as that of diamond. Chopra et al.12 produced carbonless plasma discharges with an inner diameter of approximately 1–3 nm and a length of 200 nm, resulting in stable multi-walled boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) measuring up to 200 nm in length.

As the preparation technology of boron nitride nanomaterials (e.g., boron nitride nanosheets, boron nitride nanotubes, etc.) matured around the 2000s, researchers began to focus on the strengthening, lubrication, and thermal stability of boron nitride nanomaterials in aluminum alloys in their studies13,14,15,16,17,18. Antillon et al.19 found that the nano-stiffness and elastic modulus of the laminated composites of aluminum and BNNTs and modulus of elasticity increased by 52% and 17%, respectively, and the improved properties were attributed to the effect of increased interfacial shear stress and dislocation density on payload transfer. Tian et al.20 succeeded in realizing a significant synergistic effect of high strength and elongation in Cu–Al–Ni alloys by combining thermomechanical treatments, such as cold rolling, split hopkinson pressure bar (SHPB) deformation and aging treatments.

In recent years, because of the continuous progress of computer simulation and experimental techniques and the increasing demand for high-performance materials, researchers have also begun to use more advanced research tools and methods to explore the mechanism of boron nitride’s action and the way to optimize its properties in aluminum alloys21,22,23,24,25. For example, Rohmann et al.26 investigated the interaction of BNNTs with Al by quantum chemical calculations, and found that the formation of aluminum nitride (AlN) and aluminum diboride (AlB2) is due to N or B vacancy defects within the BNNTs, and that the bonding interactions between the defect-free BNNTs and the Al substrate are very weak. Li et al.27 used first principles to investigate the structural stability, properties, and behavior of AlBN2, AlB3N4 and Al3BN4 using first principles to study the structural stability, electronic structure, optical properties, and thermodynamic properties of Al3BN4. It found that all three substances are dynamically stable and optically anisotropic, and their thermodynamic stability is in the order of Al3BN4 > AlB3N4 > AlBN2.

In this study, with the help of molecular dynamics simulation, the theoretically simulated material alloying and heat treatment processes were integrated with the actual heat treatment state. Through a series of experiments, the mechanical properties of the materials under different heat treatment conditions were tested, and then the complex influence mechanism of micro and nano boron nitride particles on the properties of the composites under different heat treatment processes was analyzed in depth from a microscopic perspective. At the same time, the molecular dynamics behavior of BN particles, alloy phase defects, phase transition organization and other key states in the casting aluminum-copper (Al–Cu) alloy system were analyzed deeply, the complementary relationship between theoretical calculations and experiments was explored, and the optimal parameters of the heat treatment process were finally summarized. The innovation of this study is that the crystal model containing micronized BN particles is constructed, and the molecular dynamics simulation is carried out based on the actual heat treatment state, which provides a new path for the design and preparation of high-performance alloys with boron nitride as an additive.

Materials and methods

Material preparation method and heat treatment experimental protocol

In this study, Al–5Cu–Mn alloy (ZL201) was used as the matrix material, and its chemical element composition and mass percentage are shown in Table 1. Two kinds of hBN particles with 99.9% purity and average particle sizes of 100 nm and 1–10 μm were used as reinforcement additions. The mass fraction of BN particles in ZL201 alloy was formulated according to a certain ratio before the experiment: 0.5%, 1%, 2%, and 3%, respectively. The casting method used in this experiment was metal-type casting, and the mold material was cast iron and graphite powder was used as a coating on the cavity surface to avoid the casting from sticking to the mold. In order to accurately assess the influence of BN micro-nano particles on the properties of ZL201 alloy, BN with different contents and particle sizes (BN1: particle size is 100 nm, BN2: particle size is 1–10 μm) was added to the ZL201 alloy, and the specific addition scheme is shown in Table 2.

To prepare the material, the ZL201 alloy is first melted in a crucible at 750 °C, then the melt temperature is reduced to 635 °C, and the aluminum foil-wrapped micro-nano BN ceramic particles are pressed into the bottom of the melt with a bell jar, followed by stirring for 5 min. After the BN particles are evenly dispersed in the matrix, the melt is heated to 735 °C and the surface oxides and slag are removed and then poured into a mold preheated at 300 °C. The whole material preparation process is shown in Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the specimen casting process. Images were constructed as 3d models by Unigraphics NX 12.0 (https://plm.sw.siemens.com/en-US/nx/) and assembled by PowerPoint.

After mold opening, the casting of Al–5Cu–xBN (x = 0.5, 1, 2, 3) target alloy material was obtained. The casting is cooled at room temperature, and the test rod required for the tensile test at room temperature and in accordance with the GB/T228.1-2010 standard is intercepted. You can see the casting and test rods size is shown in Fig. 2.

In order to study the influence of heat treatment process parameters on the mechanical properties of the composites, and to determine the optimal heat treatment process parameters under the experimental conditions, the values of the orthogonal experimental factor level were set with reference to the T5 heat treatment process parameters, as shown in Table 3. In this environment, the L9 (3, 4) orthogonal table was selected to generate the heat treatment process scheme of this experiment, as shown in Table 4. At the same time, in order to reduce the error caused by the experimental design, each group did 3 repeated experiments and averaged to ensure the accuracy of the results.

Before the experiment, each group of test materials was numbered and carried out one by one according to the heat treatment process. During the experiment, the solid solution temperature of the experimental furnace was set first, and the castings were put into the furnace for solid solution treatment.Then after waiting for the set solid solution time, the materials were taken out and quenched in water at 70 °C. Secondly, the aging temperature of the experimental furnace was set, and the quenched materials were put into the furnace for aging treatment, after waiting for the set aging time, the materials were taken out and cooled down at room temperature, and then the mechanical property test could be carried out. Finally, the mechanical properties of the materials were measured by a tensile testing machine (WAW-300 microcomputer servo controlled hydraulic universal testing machine), a multi-function hardness tester (Vickers hardness) and an electronic extensometer (ASTM E8). The fracture morphology of the tensile specimens as well as the surface scanning of the chemical elements were carried out by using a scanning electron microscope (ZEISS Gemini 300) with the equipped X-ray spectrometer. And information about grain size, shape and orientation and grain boundaries in the test specimens was obtained by using electron backscatter diffraction (Oxford-SYMMETRY S2). The microstructure of the materials was characterized by transmission electron microscopy (ZEISS Gemini 300 thermal field emission electron microscope) and the morphology and distribution of the reinforcing phases were observed.

MD model and calculation parameter settings

The crystal structure model was built with Atomsk28, starting from the pure aluminum FCC system (lattice constant: 4.0495 Å), replacing 5.3% of the atoms with the element Cu, and replacing the corresponding Al atoms with the elements B and N according to the different contents of the BN additions, so as to design the chemical compositions of the Al–5Cu–xBN (x = 0.5, 1, 2, 3). Figure 3 shows the Al–5Cu–xBN model for each alloy. The simulations in this study were implemented using the MD software LAMMPS, and the Al–Cu atomic interactions were described by the empirical embedded atom method (EAM) potentials (AlCu.eam.alloy), and the B-N atomic interactions were described by the extended Tersoff potentials (BN.extep) using the Lennard–Jones potential function mixing rule to describe the remaining atomic interactions, including Al, Cu, B, and N. In MD simulation, periodic boundary conditions (P P P) are applied in all X, Y and Z axes, and the conjugate gradient algorithm is used to optimize the geometry and minimize the model energy. The isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) system is used to simulate the heat treatment, including melting, solid solution and aging in three processes of temperature control and pressure control to simulate the melting and cooling process. Specifically, the temperature of the simulated system was controlled using a Nose’s Hoover heat bath, and the temperature and pressure were coupled once for each updated time step, with the upper and lower temperature limits set according to the parameters in the experimental protocol for heat treatment. Finally, the visualization software OVITO2429 was used to analyze and post-process the calculated results.

Crystal model of Al–5Cu–xBN (x = 0.5, 1, 2, 3) alloys.Images were modeled by Atomsk Beta 0.12.1 (https://atomsk.univ-lille.fr/), displayed using OVITO Basic (www.ovito.org) and exported as individual models, which were then assembled by PowerPoint.

The simulation of the crystal melting and heat treatment process of Al–5Cu–xBN (x = 0.5, 1, 2, 3) alloy is shown in Fig. 4. The temperature is first raised to 1008 K (735 °C) and then cooled to 300 K to obtain a cast alloy before solid solution and aging. Secondly, the solid solution and aging of the simulated materials were carried out according to the experimental heat treatment process parameter scheme, with solid solution temperatures of 806 K (535 °C), 816 K (545 °C), 826 K (555 °C), and aging temperatures of 421 K (150 °C), 431 K (160 °C), 441 K (170 °C), respectively. As for the supercell model in the MD simulation, a time scale of 50 ps is sufficient for the heat treatment stage to be completed, and when the system is warmed up to reach equilibrium, the holding time is set to 50 ps to allow the internal atoms to reach a steady state and maintain the phase transition29. After this, the temperature is reduced to 300 K at different cooling rates, respectively, when the solid solution cooling time is 10 times shorter than the aging time, to simulate the typical effects of quench cooling after solid solution and room temperature cooling after aging. Finally, uniaxial tensile simulation tests were carried out on the alloys in the cast states and heat-treated states, respectively, with the tensile tests being conducted using a Nose’s Hoover heat bath maintained at 300 K. The tensile tests were carried out by applying the fix deform command in LAMMPS, applying a uniaxial tensile load along the X-axis with a time step of 0.001 ps. Specifically, the dimensions of the box along the Y-axis and the Z-axis were kept fixed during the tensile tests while the dimensions of the box along the X-axis were increased according to the settings of the fix deform command and the box was tensile by applying a constant strain rate.

Experimental and simulation results

Experimental results

Mechanical property

Figure 5 shows the variation curves of the tensile strength of the alloy without BN particles and the composites. Firstly, it can be seen from Fig. 5a that the tensile strength of the alloys is greatly improved by the addition of both types of BN particles in the cast state. As the content of BN particles increases, the tensile strength is also gradually improved, after which the strength curves show a trend of first increase and then decrease, and all of them reach the maximum strength value when the content is 2% (BN1: 293 MPa, BN2: 291 MPa), relative to the alloy without BN particles material (253 MPa), the composite tensile strength increased by 15.81%, 15.02%, 15.02%, and 15.02%, respectively, with the addition of two types of BN particles at the cast state. 15.81% and 15.02% respectively, which indicates that BN particles can enhance the tensile strength of Al–Cu alloys.

And then, observing the effect of different heat treatment processes and BN particle content on the strength of the alloys in Fig. 5b,c, the change in strength has the same increasing and decreasing trend as in the cast state. The strength of the alloy without BN particles as well as the composite material is significantly increased after heat treatment, and the same reaches its maximum value at 2% content (BN1: 414 MPa, BN2: 407 MPa). Comparing the strength values for different heat treatment process parameters in the graphs, it can be observed that the best overall strength values are obtained when the heat treatment scheme is A2B3C1D2, i.e., when the solid solution temperature is 545 °C, the solid solution time is 9 h, and the aging temperature is 150 °C, and the aging time is 8 h. At this time, relative to the alloy without BN particles (378 MPa), the tensile strength of the composite material increased by 9.52% and 7.67% respectively after adding two specifications of BN particles, and the heat treatment process has a more obvious effect on the strength of the composite material. According to the comparison between the two in Fig. 5d, it is found that when the addition of BN particles is 2%, the enhancement effect of BN1 particles on the strength of the ZL201 alloy is slightly better than that of BN2 particles. So, nano-sized BN particles are modified better than micron BN particles. The strength values of the composites all change particularly near the A2B3C1D2 heat treatment process, and the strength values increase with the increase of the solid solution time.

Figure 6 shows the hardness variation curves of the alloy without BN particles and the composite material. It can be seen from Fig. 6a that the hardness of the alloys is greatly enhanced by the addition of both types of BN particles in the cast state. As the content of BN particles increases, the hardness of the composites is also gradually improved, after which the hardness curve shows a trend of first increase and then decrease, and all of them are in the content of 2% when the strength value reaches the maximum (BN1: 92.9 HV, BN2: 91.6 HV), relative to the alloy without BN particles (82.9 HV), in the cast state after the addition of both specifications of BN particles. And the tensile strength of the composites was increased respectively by 12.06% and 10.49%, which indicates that BN particles can enhance the hardness of Al–Cu alloys.

The hardness changes have the same trend as in the cast state, according to Fig. 6b,c. The hardness of the alloy without BN particles as well as the composite material is significantly increased after heat treatment, and the same reaches the maximum value at a content of 2% (BN1: 143 HV, BN2: 135 HV). Comparing the hardness values for different heat treatment process parameters in Fig. 6d, it can be observed that the best overall hardness values are obtained when the heat treatment scheme is A2B3C1D2. At this time, relative to the alloy without BN particles (116 HV), the hardness of the composite material increased by 23.28% and 16.38% after adding two specifications of BN particles, respectively, and the heat treatment process has a more obvious effect on the hardness of the composite material. According to the comparison of the two in Fig. 6d, it is found that the enhancement effect of BN1 particles on the hardness of the ZL201 alloy is slightly better than that of BN2 particles when the addition amount of BN particles is 2%. It means nano-specification BN particles have a better modification effect than that of micron BN particles. The hardness values of the composites in the vicinity of the A2B3C1D2 heat treatment process all change especially significantly, and the hardness values increase with the increase of the solid solution time.

Figure 7 shows the elongation variation curves of the alloy without BN particles and the composite. Firstly, it can be seen from Fig. 7a that the elongation of the alloys in the cast state with the addition of both types of BN particles decreases with the increase of the content of BN particles, and then the change curve tends to flatten out, and the value of elongation is smooth at a content of 2%. Secondly, observing the effects of different heat treatment processes and BN particle contents on the elongation of the alloys in Fig. 7b,c, the magnitude of the change is different from that in the cast state, and the plasticity of the alloy without BN particles as well as the composites is enhanced to a certain extent after the heat treatment. The effect of the addition of each content on the elongation is not significant, but the effect of different heat treatment conditions is quite obvious. When the heat treatment scheme is A2B3C1D2, the overall elongation is improved the most, compared with the alloy without BN particles (6.37%), the elongation of the composite material after the addition of two specifications of BN particles under this condition is only different by 0.12% and 0.03%, respectively, which indicates that this heat treatment process parameter plays a great role in the composite material plasticity. And according to the comparison of the elongation of both BN1 and BN2 in Fig. 7d, it is found that the enhancement effect of BN2 particles on the strength of the ZL201 alloy after heat treatment is slightly better than that of BN1 particles, i.e., the modification effect of micrometer-sized BN particles is better than that of nanometer-sized BN particles, which is in line with the common sense, the enhancement of the strength and hardness is inevitably at the cost of plasticity. Similarly, the elongation of the composites in Fig. 7d peaks at the A2B3C1D2 heat treatment process and increases with the increase of solid solution time.

Fracture topography

In order to compare the fracture morphology effects of the alloy by heat treatment and BN particle addition, the fracture morphology is shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

The fracture morphology of the alloy without BN particles is shown in Fig. 8. It can be observed that the appearance of the organization changes a lot before and after heat treatment. In Fig. 8a, the fracture consists of a large number of flaky tissues and a small number of grayish-white inclusions with microcracks, showing a typical rough and irregular morphology. This may be due to the fact that the Al–Cu alloy formed a large number of grains during the solidification process of the liquid metal, and defects such as grain boundaries and porosity existed between the grains. As a result, the fracture surface tends to show an inhomogeneous grain structure, and defects such as porosity and inclusions may also be present, leading to a decrease in the mechanical properties of the cast Al–Cu alloy. In contrast, the fracture morphology of Al–Cu alloys after heat treatment exhibits more uniform and detailed characteristics, as shown in Fig. 8b. Through heating and heat preservation treatment, the grains inside the alloy material are aligned and crystallized, thus eliminating the stability of defects, improving the stability of grain boundaries, and enhancing the crystallinity of grains. This will significantly improve the mechanical properties of the Al–Cu alloy, and these results are consistent with previous mechanical property test results.

The fracture morphology of the composites containing BN particles is shown in Fig. 9. As shown in zone A in Fig. 9a and zone B in Fig. 9b, the cast composites containing 2% BN particles showed long tear ribs and smooth blocky structures with steps. Compared with the cast alloy without BN particles, the incorporation of BN particles significantly improves the fracture morphology, and the fracture mainly exhibits a structure of alternating intergranular fracture and flat fracture regions. This indicates that the composites are a combination of ductile and brittle fracture. This phenomenon may be due to the fact that the BN particles are dispersed in the melt and localized regions will form a saturated state, which leads to the stable growth of crystals during solidification. Of course, the presence of BN particles may form irregular grains and grain boundaries, which may change the fracture path of the cast composites, which is the reason why the fracture paths along the grain boundaries appear around the formation of tear ribs in the figure.

The fracture surface with nano-BN particles added after heat treatment shows a honeycomb morphology with many pits as well as a fine mesh, which is shown at the C zone of Fig. 9c. Whereas, many sharp air holes appear on the fracture surface of the sample containing micron-sized BN particles. It is shown as zone D in Fig. 9d. Similarly, the fracture structures of the heat-treated composites are more diverse than those of the alloys without BN particles, and areas of smooth and depressed areas can be clearly seen both within the honeycomb and near the pore openings. The honeycomb on the nano-fracture surface is usually considered as evidence that the BN particles act as a barrier to crack extension in the matrix. When the material is subjected to external stress (tensile), the high hardness and strength of the BN particles enable them to absorb the energy released during crack expansion and act to slow down the rate of crack expansion, resulting in the formation of a honeycomb fracture, which contributes to the impact resistance of the composite. Whereas the small holes on the surface of the micron fracture indicate that the grain boundaries cracked during the deformation process, the micropores that appeared were formed due to the high stress concentration and dislocation collapse. The existence of micropores can promote the formation and movement of dislocations, which is conducive to the rearrangement of dislocations, thus improving the plastic deformation capacity of the material. This is the reason for the large difference in elongation of composites before and after heat treatment in the mechanical property test results.

From the fracture energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) and energy spectra in Fig. 10, it can be observed that the B and N elements are uniformly distributed on the fracture, which indicates that the BN particles are associated with the emergence of tear forks and quasi-dissociative fractures. It is due to the fact that aluminum in a molten state enables better fusion of BN particles with the matrix, while the lubricity and mechanical agitation of BN particles prevent the aggregation of BN particles in the matrix, which results in a uniform distribution of BN particles. The dispersed BN particles further promote the dissolution of B and N elements, which more uniformly changes the grain structure and grain boundary distribution of the composite, refines the grain size, and forms reinforcing-phase grains, such as AlB2, AlN, and copper nitride (CuN), internally, which leads to a more homogeneous grain boundary organization, and ultimately significantly improves the hardness of the material.

Crystal orientation and recrystallisation

Crystal orientation and recrystallization during heat treatment have a direct impact on material properties30,31,32,33,34. In order to gain a deeper understanding of the effect of nano-BN particles on the internal grain structure and grain boundaries of the matrix material at the microscopic level, electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) was carried out to analyze the two test samples before and after the addition of nano-BN particles with a content of 2% under the heat treatment condition of A2B3C1D2 (the solid solution temperature is 545 °C, the solid solution time is 8 h, the aging temperature is 150 °C and the aging time is 8 h, the results are shown in the Fig. 11.

According to the grain orientation distribution (inverse pole figure, IPF) of Fig. 11a1,b1, the grain orientation rearrangement and partial orientation shift were manifested after the addition of nano-BN particles. So, nano-BN particles significantly refined the alloy grain. Compared with the average grain orientation spread (GOS) in Fig. 11a2,b2, the partial orientation difference becomes smaller as shown in the E region, and the smaller orientation difference suppresses the further movement of grain boundaries and increases the consistency of the internal grain orientation. According to the recrystallization (REC) results of Fig. 11c1,c2, the area of the yellow area is significantly reduced after the addition of nano-BN particles, which indicates that the addition of nano-BN can transform the structure containing high energy storage morphology into a low-energy storage substructure through recrystallization, and the energy distributed at the alloy interface is reduced through recrystallization, which significantly improves the overall stability of the alloy system. This is consistent with the conclusion that BN and other additions can enhance the grain boundary strengthening effect and improve the strength and toughness of materials35,36,37,38,39.

In order to compare the effects on the morphology and dislocation motion of grain boundary, the unit cell diagrams (UC) were calculated for the matrix material without nano-BN particles and with the addition of 2% nano-BN particles. According to the changes in the UC diagrams of Fig. 12a,b, it can be seen that the addition of nano-BN particles significantly reduces the unit cell size and occupancy direction of the matrix material. And some lattice structures are arranged slightly. It may be caused by the interaction between the nanoparticles and the crystal lattice: BN particles added may lead to compressive stress effects, which cause the crystal lattice to shrink and prevent the merging of small grains during the recrystallization process. This process could effectively inhibit grain growth and continuously refine the grains.

The resite dot-matrix crystallography and grain boundary maps are shown in Fig. 13. The CLS map demonstrates the satisfaction of the dislocation condition of a particular grain boundary and GB shows the interface of grains with different crystal orientations. Comparing Fig. 13a1,a2, Fig. 13b1,b2, it can be found that the eutectic morphology of the alloy with the addition of 2% nanoparticles is denser, with relatively shorter grain boundaries, clearer morphology, and new types of grain boundaries. And the proportion of newly formed small-angle grain boundaries increases and is accompanied by many small dots (grains) with different colors. It indicates that the interaction between the nano-BN particles and the grains affects the arrangement of the crystal lattice and the formation of grain boundaries during the recrystallization process, increases the degree of coincidence between the two lattice structures in the crystal, and hinders the stress transfer between the crystals. It makes the two adjacent grains no longer slide and migrate during the material under forcing, and this structure can hinder the movement of the dislocation, which can improve the tensile and compressive properties of the material.

Stress–strain calculation results

The stress–strain curves of uniaxial tensile testing with different BN particle content and different heat treatment conditions are shown in the Fig. 14, which can obtain the peak tensile stress σmax to evaluate the tensile strength of the material.

From Fig. 14a, it can be found that the tensile strength of the composites with BN particles added in the cast state is higher than that of the alloy without BN particles, and the peak tensile stress reaches a maximum of 0.765 GPa at 2% content, which is an improvement of 4.65% (0.731 GPa) compared to the alloy without BN particles, which suggests that the addition of BN particles is favorable for the improvement of the tensile strength. Observing the tensile peak stress of the alloy without BN particles under different heat treatment conditions in Fig. 14b, the maximum peak tensile stress is 0.866 GPa when the solid solution temperature is 816 K and the aging temperature is 421 K, which is enhanced by 18.47% relative to the cast state (in Fig. 14a: 0.731 GPa), while the tensile stresses with different BN particle contents in Fig. 14c–f are all enhanced compared to the alloy without BN particles. The maximum peak tensile stresses are 0.883 GPa, 0.879 GPa, 0.918 GPa, 0.911 GPa. 16.03%, 18.62%, 20.0%, and 23.61% enhancement relative to the cast state (in Fig. 14a: 0.761 GPa, 0.741 GPa, 0.765 GPa, 0.737 GPa), which indicates that the heat treatment has a significant influence on the tensile strength of the composites after the addition of BN particles was significantly enhanced. At the same time, the maximum tensile stress value is obtained by comparing the maximum peak tensile stress when the BN particle content is 2%, which is 0.918 GPA. It is worth noting that they also obtained the maximum peak tensile stress when the solid -soluble temperature was 816 K and the timing temperature was 421 K.

In summary, both BN particles and heat treatment have enhanced the tensile strength of the as-alloyed materials, and the maximum tensile stress of the composites was obtained at a BN particle content of 2% and heat treatment conditions of 816 K + 421 K. The maximum tensile stress of the composites was obtained at a BN particle content of 2% and heat treatment conditions of 816 K + 421 K. It can be seen that this coincides with the tensile property effects achieved in the previous experiments with a BN particle content of 2% and heat treatment process conditions of A2B3C1D2.

Discussion and analysis

Effect of dislocation lines and defect faces on material properties

In order to further understand the reasons for the changes in the properties of the alloys during the tensile tests and the microscopic mechanisms of the BN particle action, the dislocation slip lines and the surfaces of the dislocation defects that appeared before and after the simulated casting condition and the heat treatment were analyzed. The trajectory file (dump_tensile.Lammpstrj) output from the tensile test was imported into the OVITO software, and the dislocations generated during the deformation of the alloy were observed using the Dislocation Analysis (DXA) module. According to the previous heat treatment experiments and MD simulation results, the content of 2% BN, heat treatment process at 816 K + 421 K. (experiment: A2B3C1D2) under the best overall performance of the composite materials obtained and the alloy without BN particles for comparison and analysis.

The internal dislocation line of the material during a uniaxial tensile test is shown in Fig. 15. You can see that both materials are dominated by 1/6 < 112 > Shockley dislocations under uniaxial stretching. It is because the alloy materials are mainly composed of Al–Cu elements, and due to the differences in lattice parameters between aluminum atoms and copper atoms, the lattice mismatch between adjacent grains is likely to occur, so a large number of Shockley dislocations are prone to occur. Comparing the results of Fig. 15a1 and a2, after the addition of BN particles, the Shockley dislocations are significantly reduced, and the density of dislocation lines is significantly lower and shorter than that without BN particles. Previous studies have shown that materials containing BN particles have smaller KAM values and a lower degree of mismatch40, and the presence of BN particles would lead to good interfacial connection between grains, resulting in fewer material defects. Comparing the results of Fig. 15b1 and b2, the dislocation density in the alloy also decreased significantly after heat treatment. On the contrary, an interesting phenomenon is that the dislocation density of the same material increases significantly after heat treatment compared to the cast state. It shows that the addition of BN particles and heat treatment conditions have a great influence on the dislocation lines in the alloy. The above phenomenon is mainly caused by the following reasons: (1) The dispersion of BN particles in aluminum alloy can effectively hinder the movement and diffusion of dislocations, thereby reducing the generation and propagation of dislocations, and the length of dislocation lines becomes shorter. (2) The distribution of BN particles in grain boundaries and crystals can promote the absorption and digestion of dislocations, and further reduce the accumulation and diffusion of dislocations. Therefore, BN particles can inhibit the plastic deformation of the master alloy, which improves the strength and hardness. It is consistent with the test results of mechanical properties in heat treatment experiments. However, after heat treatment, these dislocation lines would be reasonably regulated and optimized, and the coupling effect of different types of dislocation lines can greatly improve the strength and hardness of composite materials.

Dislocation slip line of the material after uniaxial stretching: (a1,b1) are without BN particles, (a2,b2) are with the 2% nanoparticles; Dark blue line is Perfect dislocation, Yellow line is Frank dislocation, Green line is Shockley dislocation, Purple line is Stair-rod dislocation and the Red line is other dislocation. Images were displayed via OVITO Basic (www.ovito.org) to show the misaligned lines of the computational model and exported, then assembled via PowerPoint.

The occurrence of dislocation lines in the tensile process of the material is inevitably accompanied by the formation of defect surfaces. The defect structure of the alloy material after the uniaxial tensile simulation test is shown in Fig. 16. Comparing Fig. 16a1,a2, Fig. 16b1,b2, it can be seen that the defect surfaces of the composites with BN particles are significantly reduced, indicating that the addition of BN particles is conducive to improving the internal defects of the original alloy materials. Similarly, comparing Fig. 16a1,b1, Fig. 16a2,b2, there are fewer defect surfaces than in the as-cast state, indicating that the heat treatment process conditions (816 K + 421 K) also improve the internal defects of the alloy material. In contrast, the composite material in Fig. 16b2 has the fewest dislocation defect surfaces during the tensile process, and there are more vacancies and large gaps between the defect surfaces. It is because BN particles can act as grain boundary strengtheners, hindering the movement and diffusion of dislocations and reducing the formation of dislocation defect surfaces. In addition, the heat treatment process can eliminate internal stresses and defects in the material, improve the clarity of grain boundaries, and make the crystal structure more stable and less prone to fracture when stretched.

Dislocation defect surface of the material after uniaxial stretching: (a1,b1) are without BN particles, (a2,b2) are with the 2% nanoparticles. Images were displayed by OVITO Basic (www.ovito.org) to calculate the modeled defective surfaces and exported, then assembled by PowerPoint.

Influence of phase change structure on material properties

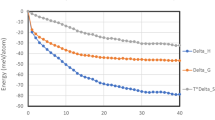

In order to determine the effect of BN particles on the phase transformation of the alloy during the tensile process and to reveal the response states of different crystal structures to mechanical strain, phase diagrams of strain and percentage of atomic coordination (coordination number neighbor analysis, cNNA) in different states were compared and the results were shown in Fig. 17.

Phase diagram of strain and percentage of atomic coordination (cNNA): (a) is alloy without BN particles and casting state, (b) is alloy without BN particles and heat treatment, (c) is alloy with BN particles and casting state and (d) is alloy with BN particles and heat treatment; the conditions of the heat treatment process are “816 K + 421 K”.

Each curve corresponds to a different structural organization (FCC, BCC, HCP, and other). It can be found that the material structure was dominated by other structures, and the coexistence of FCC and HCP phases were presented, but there was no BCC structure in the Fig. 17. Comparing Fig. 17a with c and b with d, it can be found that the initial percentage of FCC and HCP structure in the composite before the arrival of strain is (FCC: 6.7%, 8.5%, HCP: 4.8%, 5%), compared to the alloy without BN particles increased (FCC: 1.5%, 5.0%, HCP: 1.2%, 3.5%). Comparing Fig. 17a with b and c with d, can be observed that the proportion of FCC and HCP structures also increased after heat treatment, indicating that the addition and heat treatment of BN particles can promote the formation of FCC and HCP structures in the alloy. With the increase of strain, the FCC and HCP structures show a tendency of increasing and then decreasing, reaching a peak between 0.05 and 0.1 strain. In addition, Fig. 17d shown the composites proportion of FCC is 25.8% and HCP is 29.0%, with 2% BN nanoparticles added and after heat-treated. This coincides with the maximum peak tensile stress in the 0.05 to 0.1 strain interval and the optimal BN particles in the uniaxial tensile test stress–strain curves in the previous section. According to related studies, the increase of FCC and HCP phases inside the alloy is beneficial to the structural stability and promotes the improvement of mechanical properties due to the different crystal structure characteristics, atomic arrangement and dense stacking mode of FCC and HCP phases41,42,43,44. Therefore, when both FCC and HCP phases exist in the alloy, this multiphase structure can improve the stability of the material, and the interface between different crystalline phases in the multiphase structure can play a role in fixing the grains, preventing dislocation movement and crack extension, thus increasing the deformation and fracture resistance of the material.

It is noteworthy that the difference in the percentage of FCC and HCP phases is found to increase gradually with increasing strain in the above strain interval of 0.05 to 0.1 in Fig. 17b,d. Also, the phase change of HCP and FCC was significant, and the difference between the proportion of HCP and FCC gradually increased. This is due to the fact that during stretching, the lattice is rearranged under external strain, resulting in the transformation of some other structures into HCP, which usually has a tighter atomic arrangement and closer bonding between the atoms, and is capable of transmitting and carrying higher stresses45,46,47. Also, there are multiple active slip systems in the FCC structures, and the grain shape is generally more regular and the grain boundary energy is lower, resulting in a structure with higher plastic deformation capacity48,49,50. In addition, the B and N atoms in the BN particles form a solid solution in the alloy and form solid solution clusters with the alloy atoms, leading to distortion of the lattice. Therefore, when some of the other structures are transformed into HCP, the change in crystal structure may lead to an increase in the local brittleness of the material, and the material is more prone to fracture when subjected to force, which reduces the ductility of the material. This is why the heat-treated alloy exhibits reduced plasticity in the mechanical property tests, whether BN is added or not.

In summary, the HCP structure of Al–Cu alloys produced after the addition of BN particles and heat treatment is conducive to the enhancement of the strength and hardness of the material, while the existence of the FCC structure makes the material usually have better plasticity. Therefore, the coexistence of FCC and HCP structures not only increases the complexity of the internal structure of the material, but also complements each other in terms of strength, hardness and ductility, resulting in better mechanical properties.

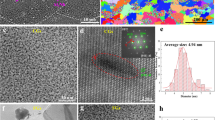

Influence of reinforcing phase structure and composition on material properties

Figure 18 shows the results of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) on the specimens prepared by the heat treatment process (A2B3C1D2). The yellow, red, and blue areas of the figure all show the presence of a reinforcing phase, demonstrating strong chemical bonding at the interface between the BN particles and the Al–Cu matrix. It can be seen from the figure that the enhanced phase of the sample mainly exists in the form of AlN, CuN and AlB2 compounds, which may be formed by the combination reaction between BN particles and the elements in the second phase of Al–Cu alloy Al2Cu, as shown in (1).

Fourier transform analysis of transmission electron microscopy in different regions shows that: (1) The plane spacing d = 0.204 in the yellow region corresponds to the (2 0 0) plane of the hexagonal AlN phase, and there are a large number of AlN-enriched phases with a length of 10 nm in the sample. This may be due to the good chemical activity and wettability of the micro-nano BN particles, which can provide better homogeneity during the stirring stage in the molten aluminum, making nitrogen (N) easily dissolved in the aluminum (Al). In this case, N replaces part of Al, forming AlN on the grain boundaries in the form of a concave structure. This concave structure will cause the distortion of the crystal structure, hinder the grain boundary slip in the form of a grain boundary strengthener, and increase the strain energy of the crystal lattice. (2) The crystal plane spacing d = 0.202 in the red region corresponds to the (-3 1 1) crystal plane of the monoclinic CuN phase, and the formation of the CuN phase is easy to cause the solution strengthening effect, that is, the solid solution elements (such as nitrogen) are dissolved in the solid solution (such as copper) to form a solid solution melt. These solute atoms diffuse into the crystal structure, forming solid solution solute clusters, increasing crystal boundaries and dislocation density within the crystal, thereby increasing the hardness of the material. However, since the CuN phase is a hard phase metal compound, when the CuN phase is enriched or unevenly distributed, these hard phases may become the starting point of cracking, resulting in an increase in brittleness and fracture of the material. (3) The plane spacing d = 0.208 in the blue region corresponds to the (1 0 1) plane of the hexagonal AlB2 phase, indicating that the doping of BN particles contributes to the AlB2 phase of the alloy. When recrystallized (heat treated), the AlB2 phase produces a grain boundary strengthening effect, increasing the grain boundary area while refining the grains, thereby increasing the hardness and making the material more resistant to wear and scratches. Therefore, when BN particles are added to the Al–Cu alloy, the CuN phase and AlB2 phase will be generated, the matrix will be dispersed and hardened, and the hardness of the composite material will be significantly improved. This is also the reason why the hardness gradually increases with the increase of BN dosage in the experimental and simulated mechanical property test results.

In Fig. 18, partial dislocation streaks were also observed in the sample (mainly near the second phase Al2Cu). The area was further screened and analyzed, and the light (dark) field and inverse Fourier transform were obtained as shown in Fig. 19. In the two different locations selected, there were periodic “split-tip” dislocation fringes in different regions of the sample. The accompanying dislocations around the matrix phase can be directly observed in bright field, which are intrinsic defects formed in the synthesis of materials. The dislocation density in the matrix material is estimated to be about 104/cm2 (expressed by the length of the dislocation line per unit area) from the brightfield image. Through the reverse Fourier transform, the dislocations in (b) and (d) in Fig. 19 are obtained, and both dislocations can form edge-shaped dislocations along the [-1 0 0] band axis under atomic resolution. Figure 19b shows a blade dislocation with an additional hemiatomic surface of (0 0 2), and Fig. 19d shows an edge dislocation with an additional hemiatomic surface of (0 2 0).

When these two blade dislocations meet, a cross dislocation pair may be formed to move, and the atoms on the ribbon axis will also diffuse to accommodate the movement of the dislocation during the slip process, forming a model of two vertical positive edge dislocations intersecting as shown in Fig. 20. In Fig. 20a, when the (0 2 0) edge-type dislocations and (0 0 2) edge-type dislocations meet each other along the [- 1 0 0] crystallographic band axis direction, they will attract each other, which will form a localized strain concentration and dislocation aggregation in the region B in Fig. 20b, increasing the resistance to dislocation movement, thus forming a reinforced region, which can increase the hardness and strength of the material to some extent. In Fig. 20b, the dislocation motion has passed through the hidden part of the atom, and it can be more intuitively observed that a dislocation stress field is generated when two positive-edge dislocations intersect at the B position, and this effect may lead to dislocation slippage or dislocation disintegration in crystals, in order to reduce the impact of the dislocation stress field, resulting in the formation of the spiral dislocations, resulting in the reduction of the plasticity capacity51,52,53,54, but due to the heat treatment of the grain refining and strengthening of the grain boundaries, the effect of plasticity reduction is not much. In this case, the atoms in the crystal are rearranged and adjusted, and a certain number of HCP lattices are created in the FCC lattice to accommodate the interactions between dislocations. This is one of the reasons for the increase of HCP lattice after heat treatment.

Conclusions and prospects

In this research, the experimental and MD calculations were combined to systematically study the state of micro-nano BN particles in cast aluminum alloys. The optimal heat treatment process was obtained and the mechanism of BN particles in the heat treatment process was discussed at the atomic level. The following conclusions are drawn.

-

1.

Different contents of BN particles were added to cast alloy and the Al–5Cu–xBN composites were prepared. The optimal heat treatment process is like this: solid solution temperature is 545 °C and needs 9 h, aging temperature is 150 °C and needs 8 h. The maximum strength and hardness can be obtained when the nano BN particles with a content of 2% are added under this heat treatment parameter.

-

2.

MD was used to calculate the aluminum matrix composites with BN particles according to the heat treatment process and the uniaxial tensile properties of the composite materials were analyzed. The results show that the crystal structure and grain boundary distribution of the alloy were changed because of adding the nano BN particle. It is conducive to the refinement of grains, and the AlB2, AlN and CuN reinforcement phases were formed in the matrix. The crystal slip and kinematic resistance would be increased for these reinforcing phases, which can improve the strength and hardness of the alloy.

-

3.

The addition of micro-nano BN particles caused the lattice to rearrange during the stretching process after heat treatment, so that the alloy has a tendency to transform to the HCP structure. In addition, the degree of coincidence between the lattice structures inside the crystals will be increased during the recrystallization process of BN particles, and the stress transfer between the crystals will be hindered, so that the composites will show a fine and more uniform grain state, and the tensile strength and hardness of the materials will be strengthened. At the same time, the recrystallization of heat treatment will cause the dislocations to cross-slip and rotate the lattice during the plane slip process, which will lead to the annihilation of multiple groups of dislocation pairs and the slight reduction of alloy plasticity. The coexistence of the residual FCC phase and HCP phase in the internal structure makes the composite material have a good balance in terms of strength, hardness and ductility.

The prepared nano-BN high-performance casting aluminum alloy can be widely used in the aerospace and new energy automobile industries, which have high comparative strength, wear and corrosion resistance, as well as in the forming of high-performance parts with very complex internal cavities. This study verifies the consistency of the molecular dynamics simulation results with the trend of the actual casting experimental results, but the molecular dynamics model constructed for the alloying elements in the study is based on aluminum-copper with the addition of B and N elements, and the influence of other elements on the heat treatment of the material should be considered in subsequent studies. In addition, the kinetic model and the law of motion of micro-nano-materials in the melting process have not been fully grasped, which is helpful for predicting the final properties of the materials.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Viswanathan, S. et al. (eds) Casting (ASM International, 2008). https://doi.org/10.31399/asm.hb.v15.9781627081870.

Lynch, P., Hasbrouck, C. R., Wilck, J., Kay, M. & Manogharan, G. Challenges and opportunities to integrate the oldest and newest manufacturing processes: metal casting and additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp. J. 26(6), 1145–1154. https://doi.org/10.1108/RPJ-10-2019-0277 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Bo-LSTM based cross-sectional profile sequence progressive prediction method for metal tube rotate draw bending. Adv. Eng. Inform. 58, 102152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aei.2023.102152 (2023).

Xie, J. et al. Phase transformation mechanisms of NiTi shape memory alloy during electromagnetic pulse welding of Al/NiTi dissimilar joints. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 893, 146119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2024.146119 (2024).

Yuhua, C., Yuqing, M., Weiwei, L. & Peng, H. Investigation of welding crack in micro laser welded NiTiNb shape memory alloy and Ti6Al4V alloy dissimilar metals joints. Opt. Laser Technol. 91, 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2016.12.028 (2017).

Zhang, D. et al. Electromagnetic shocking induced fatigue improvement via tailoring the α-grain boundary in metastable β titanium alloy bolts. J. Alloys Compd. 966, 171536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.171536 (2023).

Caldwell, J. D. et al. Photonics with hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4(8), 552–567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-019-0124-1 (2019).

Cohen, M. L. & Zettl, A. The physics of boron nitride nanotubes. Phys. Today 63(11), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3518210 (2010).

Golberg, D., Bando, Y., Tang, C. C. & Zhi, C. Y. Boron nitride nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 19(18), 2413–2432. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200700179 (2007).

Balmain, W. H. Bemerkungen über die Bildung von Verbindungen des Bors und Siliciums mit Stickstoff und gewissen Metallen. J. für Praktische Chem. 27(1), 422–430 (1842).

Wentorf, R. H. Jr. Preparation of semiconducting cubic boron nitride. J. Chem. Phys. 36(8), 1990–1991. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1732816 (1962).

Chopra, N. G. et al. Boron nitride nanotubes. Science 269(5226), 966–967. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.269.5226.966 (1995).

Meng, Q. et al. Highly ductile and mechanically strong Al-alloy/boron nitride nanosheet composites manufactured by laser additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 89, 384–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2023.01.051 (2023).

Xu, X., Zhao, Z., Ren, J. & Ma, D. Hysteresis and loss characteristics of Fe-based nanocrystalline alloys based on a novel variable-temperature dynamic Jiles-Atherton hysteresis model. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/ad0fbc (2023).

Cui, M. et al. Microstructure classification of steel samples with different heat-treatment processes based on laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS). J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 39, 1361–1374. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ja00453h (2024).

Li, W. et al. Effects of spraying parameters and heat treatment temperature on microstructure and properties of single-pass and single-layer cold-sprayed Cu coatings on Al alloy substrate. Surf. Coat. Technol. 490, 131184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2024.131184 (2024).

Liu, W. et al. Effects of recrystallization and element diffusion behavior on interfacial bonding quality and mechanical properties of aluminum laminated composites. J. Alloys Compd. 985, 174045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.174045 (2024).

Shao, L. et al. Why do cracks occur in the weld joint of Ti-22Al-25Nb alloy during post-weld heat treatment?. Front. Mater. 10, 1135407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2023.1135407 (2023).

Antillon, M., Nautiyal, P., Loganathan, A., Boesl, B. & Agarwal, A. Strengthening in boron nitride nanotube reinforced aluminum composites prepared by roll bonding. Adv. Eng. Mater. 20(8), 1800122. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.201800122 (2018).

Tian, X. et al. Cooperative effect of strength and ductility processed by thermomechanical treatment for Cu–Al–Ni alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 849, 143485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2022.143485 (2022).

Cong, Z. & Lee, S. Study of mechanical behavior of BNNT-reinforced aluminum composites using molecular dynamics simulations. Compos. Struct. 194, 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.03.103 (2018).

Li, J., Huang, Y., Zhou, Y. & Zhu, F. Role of boron nitride nanosheet coatings on aluminum substrates during the nanoindentation from the atomic perspective. Appl. Surf. Sci. 608, 155126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.155126 (2023).

Vijayaraghavan, V. & Zhang, L. Tensile properties of boron nitride-carbon nanosheet-reinforced aluminum nanocomposites using molecular dynamics simulation. JOM 72, 2305–2311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-020-04031-9 (2020).

Zhao, Y. Stability of phase boundary between L12-Ni3Al phases: A phase field study. Intermetallics 144, 107528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intermet.2022.107528 (2022).

Fan, T. et al. Nucleation and growth of L12-Al3RE particles in aluminum alloys: A first-principles study. J. Rare Earths 41, 1116–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2022.05.018 (2023).

Rohmann, C. et al. Interaction of boron nitride nanotubes with aluminum: a computational study. J. Phys. Chem. C 122(27), 15226–15240. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b00774 (2018).

Li, B. et al. First-principles calculations: Structural stability, electronic structure, optical properties and thermodynamic properties of AlBN2, Al3BN4 and AlB3N4 nitrides. Mater. Sci. Semiconductor Process. 160, 107400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2023.107400 (2023).

Hirel, P. Atomsk: A tool for manipulating and converting atomic data files. Comput. Phys. Commun. 197, 212–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2015.07.012 (2015).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open Visualization Tool. Modell. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18(1), 015012. https://doi.org/10.1088/0965-0393/18/1/015012 (2009).

Ma, K., Ren, S., Sun, H. & Ma, X. Molecular dynamics simulations of TC4 titanium alloy with mechanical property calculations after various heat treatments. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 25367–25372. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2cp03739d (2022).

Attar, H., Ehtemam-Haghighi, S., Kent, D. & Dargusch, M. S. Recent developments and opportunities in additive manufacturing of titanium-based matrix composites: A review. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 133, 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2018.06.003 (2018).

Jiang, Y. & Qiu, K. Computational micromechanics analysis of toughening mechanisms of particle-reinforced bulk metallic glass composites. Mater. Des. (1980–2015) 65, 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2014.09.013 (2015).

Liu, Y. et al. Research on the interface properties and strengthening–toughening mechanism of nanocarbon-toughened ceramic matrix composites. Nanotechnol. Rev. 9, 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2020-0017 (2020).

Wu, G., Zhang, Q., Yang, X., Huang, Z. & Sha, W. Effects of particle/matrix interface and strengthening mechanisms on the mechanical properties of metal matrix composites. Compos. Interfaces 21, 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/15685543.2014.872914 (2014).

Baazamat, S., Borhani, E. & Tajally, M. The correlation of microstructure, recrystallization texture and mechanical properties with second–phase content in Al/WO3/SiC hybrid nanocomposite during ARB process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 798, 109743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2020.140060 (2020).

Kesharwani, R., Jha, K. K., Imam, M., Sarkar, C. & Barsoum, I. Comparison of microstructural, texture and mechanical properties of SiC and Zn particle reinforced FSW 6061–T6 aluminum alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 26, 3301–3321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.08.161 (2023).

Kumar, R., Gupta, A., Dandekar, T. R. & Khatirkar, R. K. Microstructure and texture development in AA3003 aluminum alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 24, 100965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.100965 (2020).

Liu, T. S. et al. Insights into the influences of nanoparticles on microstructure evolution mechanism and mechanical properties of friction-stir-welded Al 6061 alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 871, 144929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2023.144929 (2023).

Sidor, J. J., Petrov, R. H. & Kestens, L. A. I. Modeling the crystallographic texture changes in aluminum alloys during recrystallization. Acta Mater. 59, 5735–5748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2011.05.050 (2011).

Qin, G. et al. Strengthening FCC-CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloys by Mo addition. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 35, 578–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2018.10.009 (2019).

Schönecker, S., Li, W., Vitos, L. & Li, X. Effect of strain on generalized stacking fault energies and plastic deformation modes in fcc-hcp polymorphic high-entropy alloys: A first-principles investigation. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 075004. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.5.075004 (2021).

Wu, Y., Du, C., Yu, Z., Wang, R. & Ren, X. Effect of Cu content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Fe20Co30Ni10Cr20Mn20 FCC-typed HEAs. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 897, 146336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2024.146336 (2024).

Zhu, C., Xu, L., Liu, M., Guo, M. & Wei, S. A review on improving mechanical properties of high entropy alloy: interstitial atom doping. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 7832–7851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.05.002 (2023).

Hao, P. D. et al. Anisotropic elastic and thermodynamic properties of the HCP-Titanium and the FCC-Titanium structure under different pressures. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 3488–3501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.01.086 (2020).

Hsieh, K.-T. et al. Atomistic simulations of the face-centered-cubic-to-hexagonal-close-packed phase transformation in the equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi high entropy alloy under high compression. Comput. Mater. Sci. 184, 109864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.109864 (2020).

Skrotzki, W. et al. Microstructure, texture, and strength development during high-pressure torsion of CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. Crystals 10, 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10040336 (2020).

Zhao, S. et al. Amorphization in extreme deformation of the CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. Sci. Adv. 7, eabb3108. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb3108 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Towards ultrastrong and ductile medium-entropy alloy through dual-phase ultrafine-grained architecture. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 126, 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2022.02.052 (2022).

Sabirov, I., Estrin, Y., Barnett, M. R., Timokhina, I. & Hodgson, P. D. Tensile deformation of an ultrafine-grained aluminum alloy: Micro shear banding and grain boundary sliding. Acta Mater. 56, 2223–2230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2008.01.020 (2008).

Shen, Z., Wagoner, R. & Clark, W. Dislocation and grain boundary interactions in metals. Acta Metall. 36, 3231–3242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(88)90058-2 (1988).

Domain, C. & Monnet, G. Simulation of screw dislocation motion in iron by molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 215506. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.215506 (2005).

Duesbery, M. Dislocation motion, constriction and cross-slip in fcc metals. Mater. Sci. Eng. 6, 35. https://doi.org/10.1088/0965-0393/6/1/005 (1998).

Nadgornyi, E. Dislocation dynamics and mechanical properties of crystals. Prog. Mater. Sci. 31, 1–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/0079-6425(88)90005-9 (1988).

Olson, G. B. & Cohen, M. A general mechanism of martensitic nucleation: Part I. General concepts andthe FCC→ HCP transformation. Metall. Trans. A 7, 1897–1904. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02659822 (1976).

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Guizhou Industry Simulation Design & Innovation Center (QKZYD NO.[2016]4006). Moreover, this research was also financially supported by Doctoral Research Foundation of Guizhou Normal University (2017), Guizhou Education Department Science and Technology Research Project Serve for the “Four New” and “Four Modernization” (QJJ [2022] No. 005) and the Advanced Equipment Manufacturing Industry Mentor Group Project (C423015/118).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L.; Methodology, Zq.Z. and C.Z.; Software, Zq.Z., Lx.W., and C.Z.; Formal analysis, C.Z., Lx.W. and Zq.Z.; Resources, R.L. and Q.Z.; Writing-original draft, Zq.Z., C.Z.; Writing-review & editing, R.L., C.Z., Xh.J. and X.L.; Supervision and Resources, R.L.; Funding acquisition, Q.W. and R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, R., Zhou, C., Zhang, Z. et al. Simulation and experiment research on heat treatment of micro and nano BN particles modified casting aluminum copper alloys. Sci Rep 15, 21258 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05162-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05162-2