Abstract

This study delves into the vulnerability of the smart grid to infiltration by hackers and proposes methods to safeguard it by leveraging blockchain and artificial intelligence (AI). A categorization and analysis of cyberattacks against smart grids will be conducted, focusing on those targeting their communication layers. The main goal of the work is to address the challenges in this area by implementing novel detection and defense strategies. The authors categorize attacks on smart grid networks based on the communication classes they want to compromise. They propose novel taxonomies specifically designed to detect and implement defense strategies. The study investigates artificial intelligence and blockchain techniques to identify cyber-attacks that employ deceptive data injection. The study indicates that cyberattacks against smart grids are increasing in frequency and complexity. The paper proposes innovative strategies for defense, such as enhancing cybersecurity with artificial intelligence and blockchain technology. The research further enumerates several challenges, such as counterfeit topological data, imprecise data identification, and combining big data with blockchain technology. Given the increasing risks, the study emphasizes the crucial need for robust cybersecurity safeguards in smart grids. This work contributes to the protection of smart grid infrastructures by categorizing attacks, suggesting novel defenses, and exploring solutions integrating artificial intelligence and blockchain technology. Research should prioritize enhancing technology to maximize security and counter emerging attack methods. The intended audience of our paper comprises graduate-level academics and independent researchers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Context

The transformation of traditional electrical infrastructure into smart grids (SGs) has introduced significant advancements in energy efficiency, automation, and intelligent management. These grids leverage technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Blockchain, and the Internet of Things (IoT) to optimize energy distribution, enhance security, and improve communication among various grid components. The global industrial automation market is projected to reach USD 54.2 billion by 2026, reflecting the rapid adoption of these technologies1.

While SGs offer numerous advantages, they also introduce cybersecurity risks due to their interconnected nature. Cyberattacks targeting communication layers, data integrity, and control mechanisms pose severe threats, leading to financial losses and system failures. Given these vulnerabilities, this study investigates AI and blockchain-based security mechanisms to protect SG infrastructures from emerging cyber threats while ensuring optimal performance and reliability2. Figure 1 shows the main components of smart grids. Effective communication and collaboration between the grid, service providers, and users are crucial for the intelligent grid framework.

Each part of this system can communicate using a diverse array of protocols and channels. At the grid domain level, substantial amounts of electricity are generated, conveyed, and dispersed. Contemporary meters, sensors, and control equipment have been extensively deployed, enabling the practical examination of the advantages of the SG3. Figure 2 shows the characteristics of an SG. Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI) refers to the physical equipment that links individual residential units to the broader communication network. Cloud computing service providers may experience advantages from utilizing intelligent data to gain insights into problems such as energy usage and power outages4.

Propagation methods utilizing either wired or wireless networks have the potential to reach a wider audience. Cables are necessary for the transmission of data across the Internet Protocol Version 2 (Ethernet), power lines, and fiber optics. Optical free-space networks, cellular, ZigBee, Z-wave, and Wi-MAX are all parts of today’s communication infrastructure. All of the smart power grid’s many parts can talk to each other and share information5. Business owners are increasingly concerned about the security vulnerabilities of SG due to their attractiveness to hackers6.

Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of challenges related to SGs in different fields.

Key aspects and novel elements

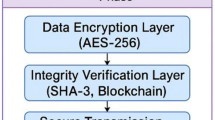

This research proposes an innovative AI-Blockchain Hybrid Security Model, which integrates advanced machine learning (ML) techniques for intrusion detection with blockchain-based authentication and data integrity mechanisms. The proposed model enhances smart grid cybersecurity by leveraging AI-driven predictive analytics to detect anomalies in energy consumption patterns and network behavior, while blockchain ensures a tamper-proof, decentralized security framework for verifying transactions and securing data exchanges.

One of the central contributions of this study is the development of a novel taxonomy that categorizes cyberattacks based on their impact on different smart grid layers, providing a structured approach to understanding threat vectors and their countermeasures. The AI-enhanced Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) proposed in this work utilize supervised and unsupervised learning techniques to detect cyber threats in real-time, significantly improving response time and accuracy. Furthermore, blockchain-based security mechanisms, including smart contracts and decentralized consensus algorithms, offer robust protection against data manipulation and unauthorized access.

This study also presents a comprehensive review of challenges and future directions in integrating AI and blockchain within SGs. Key challenges, such as scalability, interoperability, computational overhead, and latency, are critically analyzed to propose efficient solutions for seamless deployment in real-world smart grid environments. Additionally, we explore the implications of privacy-preserving AI techniques and secure multi-party computation to ensure enhanced security while maintaining system efficiency. Our findings contribute to building a more resilient cyber-physical security model, addressing both internal and external cybersecurity threats.

By addressing these challenges, this research provides a foundational security model that enhances resilience against cyber threats while maintaining the efficiency and adaptability of smart grids.

Structure of the article

5. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Sect “Literature review” explores the existing literature on smart grid security challenges, cyber threats, and defense mechanisms, offering an in-depth analysis of current methodologies and identifying research gaps. Sect “Methodology” outlines the research methodology, including the classification of cyberattacks, data collection strategies, and the security framework design. Sect “Results” presents our findings, detailing the proposed AI-Blockchain Hybrid Security Model, its implementation, and its impact on smart grid cybersecurity. Finally, Sect “Application of blockchain and Artificial intelligence” concludes the study by summarizing key insights and outlining potential future research directions, with an emphasis on enhancing security frameworks through technological advancements and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Literature review

Due to its dependence on computer networks and other networked technology, SG is vulnerable to cyberattacks, which can compromise the system’s dependability. Complementary operations related to the production, distribution, and use of energy encompass the industrial, agricultural, and healthcare sectors1. The subsequent examples illustrate several analogous actions: Feasibly catastrophic and costly assaults on the country’s power infrastructure would compel people to adjust their daily schedules. The impact of cyberattacks that exploit the inherent weaknesses of SG and the subsequent financial burdens of these attacks becomes evident when the total cost of these attacks is taken into account18. The reliability of SG may be compromised by insufficient security application software, defective software and hardware maintenance, and issues with its logical design. In terms of cybersecurity risk management, these security governance procedures may not meet the protocols for the detection, assessment, mitigation, and restoration of dangers, increasing the risks associated with industrial automation in SG environments19. These defects are identified and utilized to directly impact the extent of harm to any electrical system20. Malware software has become the preferred tool for exploiting SG vulnerabilities during attacks21. Only individuals with expertise in criminal software development inside the electrical industry have the skill to decipher this information. The penetration of a system by malware can occur through several means, such as unsolicited emails, hyperlinks to malicious websites, and system weaknesses.

The Internet of Things (IoT) is a fundamental component of the concept of “Industry 4.0,” which integrates embedded software with real-world sensors and cyber-physical technologies. By using ML and artificial intelligence at each phase of production, this approach promotes collaboration22. Industry sectors that could potentially gain advantages from the Internet of Things include medicine, home automation, the arts, business, classrooms, and universities23. IoT devices, however, introduce significant cybersecurity risks, necessitating the deployment of AI-driven detection and prevention mechanisms to mitigate potential network attacks24. If Smart Grid (SG) provides the capacity to remotely operate and monitor different devices, homeowners may obtain an enhanced feeling of security. Notwithstanding the exciting prospects of intelligent buildings, their widespread adoption is impeded by several obstacles. Emphasizing security should be the highest emphasis in all areas of SG management, design, and construction standards25. By leveraging AI-powered anomaly detection and intrusion prevention systems, SG infrastructures can significantly reduce cybersecurity vulnerabilities associated with IoT-enabled devices, improving both security and operational resilience24.

Through using the capabilities of the Internet of Things, SG can augment individuals’ perception of security and tranquility. Furthermore, other than enhancing corporate productivity, they can also reduce energy inefficiency. Enhancing energy consumption control may be achieved by incorporating additional IoT devices into smart grids (SGs)26. The implementation of IoT-based humidity, temperature, and air pressure monitoring has the potential to decrease energy consumption for SG. Intelligent grids employ digital sensors linked to the internet to regulate the lighting. The potential application of internet-connected gadgets in disaster relief and crisis management is under ongoing consideration. Understanding how safety systems work has been greatly simplified by the Internet of Things, which allows sensors to be connected and real-time data to be transmitted to people responsible and at risk27. However, these advancements also introduce novel attack vectors, requiring robust cybersecurity frameworks that integrate both AI-driven security solutions and blockchain-based authentication techniques19. This technology has the potential to simplify users’ lives and enhance the organization of intelligent applications. Incorporating artificial intelligence with Internet of Things-enabled components is crucial for enhancing the energy efficiency of silicon graphene. Table 2 enumerates the several problems associated with SGs and the corresponding fixes to address those challenges.

The authors discussed the essential “SG,” or intelligent electrical system, required to manage variability in energy requirements. In the field of electrical power distribution, the term “SG” refers to a system that efficiently handles energy generation, transmission, and consumption with low demands on computing resources. Due to their structural architecture, these networks distinguish themselves from others. Contemporary technology enables individuals to independently diagnose, communicate, regulate, and monitor themselves21. In regions without sufficient renewable energy sources, the complexity of electrical distribution networks increases. Some of the problems include insufficient service, not making enough use of green power, and misuse of resources1. Renewable forms of energy fill an important function in Central America and Mexico. Renewable sources, such as wind and solar, are projected to account for 50% of the electricity generated by major power plants by 203040.

Energy systems must be efficient, flexible, and intelligent for a country to prosper. About 50% of the electricity would come from conventional sources, while the other 50% would come from smaller, more dispersed sources like residential solar panels and wind farms. This benefits energy, the economy, the environment, and technology. Due to solid-state generators, the electric power sector is becoming more decentralized, accessible, and efficient, benefiting businesses, the environment, and the global economy41. Conducting tests, enhancing technology, educating customers, establishing standards and laws, and exchanging information among electrical workers are all crucial during the transition period for smart grids to become completely implemented42. Hierarchical, unsupervised feature extraction, and semi-supervised feature extraction can teach machines. Popular ML algorithms include SAM, DBN, DBM, RNN and CNN. Deep understanding uses convolutions and drop-out techniques to learn from massive datasets. ML needs more data than traditional training methods. ML methods that extract unsupervised or semi-supervised characteristics are efficient43. Energy cost management and emission reduction require accurate energy demand predictions. Vehicle autonomous vehicles (VAVs) may evaluate pressure, gas flow, and temperature sensors using a wavelet neural network. Noun neural networks (NNs) and wavelet transforms work like this. System expenses and battery charge times can be optimized via time-series analysis. This strategy is now easier to deploy thanks to microgrid dependency prediction32. Both improve accuracy when used together. Time series prediction is vital, and ML should invest heavily in it. Dimensionality of the time series dataset may be an issue. Multiple methods can reduce data dimensionality when graphically showing time series data44. These methods include data-adaptive, model-based, and non-data-adaptive representation. The authors of reference45 developed a time series analysis method for social groups (SGs) to uncover periodic patterns from human and machine behavior data. Universal harmonic search, Fuzzy time series, and support vector machines were used to generate an unfailing electric load model46. This study analyzed occupant count-based building energy consumption calculations. Statistical support vector machines are supervised learning. An expectation survey can help a facility meet future management, resident satisfaction, and safety and security needs47. Support vector machine algorithms locate the hyperplane with the biggest difference between two data sets to partition the data into two groups48.

Upon the eventual implementation of IIoT, numerous organizations will have the opportunity to adopt novel business models. As referenced49, market-enhancing technologies including intelligent data, pervasive connectivity, decision-support systems, and predictive analytics will be used. Nevertheless, potential issues related to centralization, privacy, integrity, and trust may emerge due to the susceptibility of traditional Internet of Things architectures to various security vulnerabilities and network attacks31. This research attempts to provide a simple blockchain security architecture that uses AI to protect IIoT device data. Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) systems that use cloud computing may face security and privacy issues while processing data in the cloud or on devices, innovation was used to solve certain problems. This study49 introduces a novel approach to enhance and simplify security operations by combining the advantages of lightweight boundary conditions with artificial intelligence techniques based on highly tuned sprinting neural networks. The implementation of a genuine intrinsic analysis paradigm that encodes characteristics enables the mitigation of damage caused by strikes50. A comprehensive evaluation of this approach is presently underway using a diverse range of attack datasets to verify its effectiveness. In addition, we assess and analyze the effectiveness of privacy-safeguarding approaches and artificial intelligence methodologies by considering several parameters.

Methodology

Research questions

This Systematic Literature Review (SLR) uses blockchain and AI to discover, appraise, and compress empirical data on secure governance (SG) security. This assessment focuses on Singapore’s blockchain implementation. Supply chain management difficulties and blockchain/AI solutions are examined. SG’s benefits and structure are also examined. Blockchain and AI methods boost SG security51. To achieve this objective, the review will be directed by the research questions and their underlying motives. The flow of the study is shown in Fig. 3, while the research questions are presented in Table 3.

Select data sources

The research papers were obtained from recognized digital libraries, including IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, ACM Digital Library, Springer, and Wiley52. A comprehensive search was conducted on full texts, abstracts, and keywords to retrieve prior studies relevant to the research questions. The chosen data repositories and the total number of studies resulting from search queries are presented in Table 4; Fig. 4.

Search string formulation

To refine the search process, a systematic keyword selection approach was used, based on the research questions (Table 3)52. Boolean operators (‘AND’ and ‘OR’) were employed to construct a precise search string. The search string formulation process is illustrated in Fig. 5 and the selected keywords are presented in Table 5.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The selection of research articles was based on well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure relevance and quality53.

Inclusion criteria

-

Academic publications written in English from 2007 to 2024.

-

Studies focusing on blockchain applications in Sustainable Growth and Smart Grid security.

-

Research including empirical evaluations through supervised experiments or simulations.

-

Publications covering AI and blockchain architectures, applications, and components.

-

Studies discussing blockchain and AI integration for security enhancement in software governance.

-

Only peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, or book chapters were considered.

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies published before 2007.

-

Research focusing on blockchain applications outside cybersecurity or smart grid security.

-

Papers lacking empirical validation or theoretical relevance to AI-blockchain integration.

-

Studies that do not evaluate the impact of AI and blockchain on cybersecurity challenges.

For the inclusion of 2024 publications.

-

The selected studies from 2024 were sourced from preprint repositories and early-access journal articles from IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, ACM Digital Library, and Springer53.

-

These sources were vetted to ensure credibility and alignment with the systematic review methodology.

Define quality assessment criteria

The following quality assessment framework is synthesized from previous systematic reviews54, and adapted to match our research questions. Table 6 lists the evaluation criteria applied to each selected study.

Primary study selections

Primary studies were chosen based on their alignment with the research questions and quality assessment criteria. Using a multi-stage systematic selection methodology, 211 primary sources were selected for analysis. Figure 6; Table 7 present the distribution of selected papers by year, and Fig. 7 provides a PRISMA diagram summarizing the selection process.

Results

Sect “Results” presents both synthesized insights from prior literature and our novel contributions. Specifically, the attack taxonomies and mitigation strategies in Tables 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 are based on an in-depth analysis of existing literature, whereas our proposed AI-Blockchain security model, its layered architecture, and the hybrid detection and authentication techniques represent our original contributions.

Vulnerabilities of SG

The vulnerabilities described in this section are based on synthesized findings from the literature and form the foundation for our proposed layered defense framework.

Demand response (DR) refers to the adaptation of customers’ power consumption patterns in reaction to fluctuations in prices. Consequently, the peak load consumption decreases and the service dependability of the system increases. Numerous years ago, enterprises and industries initiated the use of demand response (DR) as a means to enhance and maintain stability in the electricity grid1,54. According to the most recent Science and Technology report, the Demand Response can greatly influence the residential electricity industry. The incorporation of intelligence and bidirectional communication capabilities into the Smart Grid has the potential to enable utilities to provide customers with up-to-date price information. To optimize the power supply-to-load demand ratio, the Smart Grid (SG) utilizes demand response (DR) methodologies and incentives. This impacts utilities, businesses, and homes regardless of the system’s scale55. DR’s emphasis on client engagement and responsiveness can substantially improve system expansion, functionality, and market effectiveness. There are three distinct methods by which customers can modify their power use during Demand Response (DR)56. One classification of demand response programs (DRPs)57 is based on the approach they use to commence demand reduction. There are three types of programs: rate-based (price-based), incentive-based (event-based), and demand reduction bids. The implementation of a more secure system would benefit both players and clients by providing a wider range of choices, reducing costs, and enhancing market performance. A system is classified as vulnerable in the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (C.V.E.) database if it is susceptible to being readily targeted and attacked. A computer security vulnerability refers to a defect in the logical structure of software or hardware that, if taken advantage of, has the potential to undermine the security of the system. This issue has the potential to jeopardize security.

Typically, in such a situation, the process of addressing vulnerabilities entails the updating of the code. However, it is also feasible that the specification may require modification or total abandonment.

Interoperability and data management vulnerabilities

Interoperability refers to the extent to which various systems and technologies can interchange data and programs with each other. To entirely achieve the possibility of SG technology, it is essential to integrate different intelligent devices and architectures that utilize both software and hardware components1,58. An essential objective of the Internet of Things is to enable objects and systems to establish efficient communication among themselves. Facilitating the integration of new smart products with existing infrastructures and enabling communication between smart goods from different manufacturers is of utmost importance. To optimize the utilization of resources, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs)59 —a vital element of the future smart grid—mandate thorough testing. The challenges encompass the development of intelligent systems for energy management, power distribution from batteries, and optimizing power usage60. Compatibility testing of the intricate power electronics is necessary at every stage of small-scale fabrication. Before they can be implemented, it is necessary to resolve concerns regarding the intricacy and potential disruption they may bring to the system61. Inefficiencies in SG data management include the areas of data aggregation quality, data security, compliance control, common scope, and management technique effectiveness. Considerable amounts of data are generated and exchanged among multiple organizations. By utilizing reliable data streams, operators can effectively monitor and manage the grid system. Encompassed within these data streams are commercial records, meteorological predictions, and grid operational records. Furthermore, adding to the complexity is the challenge of fulfilling the legal need for the timely reporting of precise data. It presents a challenge. The sophisticated systems implemented for data gathering, analysis, processing, maintenance, and security in the era of digital technology do possess inherent weaknesses. Many Supervision Groups lack the means to ensure the confidentiality and security of their data62.

Vulnerabilities in scalability and energy storage

Distribution grid platforms, distributed energy resource management, and complex wealth management can all be built with the help of data collected from both information technology and operational technology. This makes it easier to turn raw data into actionable intelligence. In particular, sustainable energy facilities in industry have demonstrated a plethora of useful applications63. It takes a long time and a lot of effort to use established consensus mechanisms like Proof of Work (PoW) and Proof of Stake (PoS) to create a block or complete a transaction. The procedure also required a lot of power, which became increasingly problematic as the workforce expanded. The result is an increase in the number of nodes, also known as consumers, in the Sub-Grid Energy System (SGES)1,64. In order for the system to support an ever-growing user base, it needs to meet specific requirements. In fact, this situation has the potential to impact the SGES’s scalability65. By concentrating mining power in the hands of a few companies, the current BCN architecture prevents miners from other regions from getting involved and allows the covert consolidation and growth of the SGES activities. Another obstacle that limits the large growth of SGES is the current state of the BCN-enabled system’s interoperability and heterogeneity capabilities. Our goal is to improve scalability by making changes to the current design of the BCN network. Energy Storage Systems (ESSs) are chosen based on certain criteria. Utilizing flywheel technology, an ESS may store energy in the form of kinetic energy66 This device is designed for stationary applications and has a lifespan of 10,000 cycles. Its energy density is around 20 Wh/me, and it is commonly used in conjunction with electric machines that use permanent magnets or induction machines. These features—dynamic reaction speed, self-discharge rate, power density, ruggedness, and excellent energy conversion efficiency—define this gadget. For basic regulatory reasons, flywheel technology—which boasts an efficiency of almost 99.99%—is the ideal large-scale ESS40. This Energy Storage System’s (ESS) fuel cell uses a reversible electrochemical mechanism to produce energy. The hydrogen fuel cell has a lifespan of 20,000 cycles and produces no pollutants because water is the only byproduct. In addition, its storage capacity is enhanced, its efficiency is around 50%, and its dynamic reactivity is excellent. Electricity generation is transformed into thermal energy by thermal energy storage systems (ESS), which then store this thermal energy for usage during times of lower demand. An air-handling device, a heating/cooling setup, and a heat exchanger used for storage make up the system. Effective load transmission is made possible by this storage device, which may be charged either locally or centrally67. The huge store capacity, quick response time, and frequency regulation capabilities of this Energy Store System (ESS) are its most notable advantages. Consequently, these load requirements can be satisfied by taking into account a wide range of functional, technological, and financial factors. Due to their high price tag, energy storage systems (ESS) have been slow to incorporate supercapacitors, magnetic coils, and superconductors.

Cost, availability and complex SG vulnerabilities

Presently, sophisticated equipment and sophisticated systems are operated by large mining corporations. An increasingly complex consensus method can help overcome the difficulty of mining validity, which requires a sophisticated hardware system to compete with current BCN technology68. Because there is a third party involved and a large power usage, an additional medium of exchange is needed. SGES is a more economical option since these problems can be resolved by including new or enhanced features such as the inter-SC algorithm and IBSM into the current BCN technology69. “Availability” in this context refers to the guarantee of timely data access and the maintenance of reliable information. If unavailable, grid management and the delivery of energy could be interrupted. An increase in contact information within an SGES arrangement can slow down data transfer and prevent authorized users from accessing the system70. Thus, keeping high availability requires providing good security. The substantial third-party participation in the existing BCN makes it necessary to update the modeling of the current BCN since it causes the data retrieval process in SGES to be slow, complicated, and inaccurate. As SG improves and grows, more intelligent electronic devices (IEDs) and parts are added. These IEDs and their components connect to many network systems, enabling more applications and services and streamlining communication with crucial infrastructures1,71.

Authentication heterogeneity, interoperability, and security vulnerability

Advanced SGES are made up of several different intelligent parts and the majority of these devices and systems are electrical and electronic. Exact device and owner identification are necessary for efficient system control, monitoring, and maintenance72. Reliable device authentication makes it possible to identify instances of illegal access to the system’s resources. Only authorized nodes or users with the most recent BCN-enabled SGES authentication should be permitted access. During the authentication procedure, an attacker may obtain access to the user’s data and damage the network protocol73. This problem can be resolved by requiring users to carry out authentication processes, such as encryption processes1. SGES’s BCN technology does not sufficiently enable heterogeneity and interoperability. Inter-chain communications need a person to rely on and have trust in the authority of a third party. To improve interoperability and cross-chain activities, there isn’t yet a way to execute smart contracts across various chains. To resolve these problems and make the functions available, the current BCN in the SGES designation must be modified. One major problem is the scalability of the BCN-enabled SEGS. The upcoming version of BCN technology may include the introduction of PoL an enhanced consensus mechanism74. This consensus process enables BCN networks to process transactions using less energy. The efficiency of transaction validation has increased, and it won’t experience any new issues despite the number of nodes It is also possible to remove the concentrated mining authority and the system’s posed centralization. There will be incentives for miners from different locations to take part in the mining process. As a result, more transactions will be made possible by SGES communications75.

Attacks and countermeasures on smart gird

False data injection attack

By manipulating meter readings and surreptitiously influencing state estimation calculations, FDIAs jeopardize the security of the SG1,76. FDIAs may also evade SG BDDs, which identify erroneous data. Over the past decade, FDIAs’ effects on SG networks have been extensively studied77. FDIAs, who hack grids and manipulate data, benefit and suffer from cyber-physical system proliferation. Bus voltage and phase angle were estimated by state using SCADA to examine transmission stability and load shedding78. Installing an energy management system in the control center guarantees the SG operates as designed79. SG reliability and efficacy depend on state estimation precision. To operate and manage SGs effectively, conditions must be accurately assessed. Cyber-physical risk assessment of manipulated data is difficult. FDIAs manipulate network topology, deceive the control center, and disrupt the energy market to profit from power grid applications like the SCADA system and phasor measuring unit. Many research has examined FDIAs’ long-term effects on SGs80. The authors examined whether FDIAs may cause several branch outages at once. Further research was done on FDIAs’ data-dependent outage detection method, P.M.U81. Switchgear generators (SGs) frequency excursions can cause blackouts and electrical equipment damage. Reference25 details these phenomena. FDIAs have become better at hiding their activities and evading detection. Table 8 lists DL, Kullback-Leibler distance, sparse optimization, colored Gaussian noise, spatiotemporal correlations, Kalman filter, and Bayesian clustering (BC) technology as countermeasures. These are simply a few of the methods described in82.

Denial-of-service attack

The cyber defenses of the SG protect its data, power, and communication networks from potentially damaging attacks. Storage group access and power are impacted by denial-of-service attacks. Service disruptions can occur as a result of distributed denial of service attacks. Denial-of-service attacks use system weaknesses or inundate a specific channel or device with an excessive amount of data. Utilizing botnets is a method of launching DDoS attacks. Electrical service dependability is guaranteed by a Substation Generator. Disseminated denial of service attacks target the data, computer, energy, and communication infrastructure of the intelligent grid. A power outage would impact a substantial number of Standard Grid consumers, amounting to millions83. Distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks significantly decrease network throughput and incur costs amounting to billions of dollars. The networking issues and power disruptions experienced by the SG are caused by denial-of-service attacks. Systems utilized by smart grids include data aggregators, smart meters, RTUs, IEDs, P.M.U.s, and P.L.C.s. A complete representation of data denial-of-service attack is depicted in Fig. 81,84.

Due to their use of Internet-sponsored protocols, these devices are vulnerable to denial-of-service attacks. In general, security is fraught with risk. P.M.U. networks may not be acknowledged by many utility companies as crucial cyber assets, thereby posing challenges in the defense against denial-of-service attacks. Denial-of-service attacks, ranging from minor to major, pose a threat to the availability and integrity of services. Subsequently, there are deficits and losses84. It is feasible to detect DoS assaults utilizing honeypots, ML, SDN, DL, and BC. The strategies to mitigate denial-of-service attacks are presented in Table 9. Refer to Table 9 for strategies to mitigate denial-of-service attacks.

MITM attack

Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks pose a significant threat to SG security, particularly in Modbus TCP/IP-based SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) networks. These attacks allow adversaries to intercept, manipulate, or disrupt communication between smart grid components, leading to potential data breaches, operational failures, and unauthorized control over critical infrastructure1. MITM attacks can secretly intercept smart meter data, alter energy consumption measurements, and even manipulate control commands in SG systems85. An attacker can compromise 95% of HTTPS servers by impersonating trusted sources and exploiting certificate vulnerabilities, making smart grids particularly susceptible to spoofing-based MITM attacks.

The SG network, particularly in SCADA-based industrial control systems, is a primary target for MITM attacks. Energy providers, as well as water, gas, oil, and power producers, rely on IEC 60870-5-104 SCADA connections, which have been shown to be vulnerable to MITM interception and control manipulation. Researchers have identified MITM vulnerabilities in SCADA networks, with Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) poisoning being a commonly exploited technique to reroute traffic to malicious nodes86. Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI), responsible for monitoring electricity usage and energy distribution, is particularly vulnerable to MITM attacks. Modbus TCP/IP, a widely used protocol in smart grids, is often the entry point for MITM exploits, allowing attackers to modify metering data and disrupt grid operations87.

Social engineering plays a significant role in facilitating MITM attacks. Attackers use phishing, spear-phishing, and perception manipulation to exploit human vulnerabilities, enabling unauthorized access to smart grid resources and IT infrastructure. Phishing techniques are often the first stage of a MITM attack, where adversaries deceive users into sharing authentication credentials or security tokens, allowing persistent access to SG control systems. A study on serious game-based awareness training demonstrated that educating grid operators about phishing, impersonation attacks, and over-sharing of personal information significantly improves resilience against MITM intrusions88.

Detection and mitigation strategies for MITM attacks include IDS and ML, which play a critical role in identifying anomalies in SG networks. Physical Unclonable Function (PUF) authentication mechanisms enhance smart meter security by generating unique, tamper-resistant cryptographic keys, reducing the risk of MITM-based authentication bypasses. Table 8 provides a detailed overview of various techniques and approaches used to detect and mitigate MITM attacks, including ML-based anomaly detection, IDS monitoring, and cryptographic security measures89. The table illustrates how different methods leverage AI-driven network traffic analysis, pattern recognition, and authentication mechanisms to counter MITM threats effectively. It highlights the comparative advantages of each approach, particularly in terms of response time, accuracy, and integration feasibility in real-world SG environments.

Load altering attack

Large-scale automatic controllers (L.A.A.s) regulate the energy consumption of certain loads to prevent the power system from becoming excessively burdened. There are two alternatives for Local Authorities (L.A.A.s): direct and indirect load compromising. A demand-side management system provides clients with inaccurate pricing information. An excessive amount of electricity cannot be supplied to a circuit unless loads are properly regulated and protected. The LAAs encompass both SLAAs and DLAAs. By employing a closed-loop attack load, the authors demonstrated that DLAAs had a substantial impact on load fluctuations to the peak degree. In SLAAs, the attacker maintains a constant observation of the load’s direction while alternating it. The disadvantage of a DLAA over an SLAA lies in the need for the attacker to monitor the power frequency and adjust the load according to the signal’s reliability. Spectrum generators (SGs) offer frequency detection instruments available for online purchase93. These devices are used to monitor sensitive frequency loads. Large-scale anomalies (L.A.A.s) cause the grid to undergo more abrupt and unforeseen fluctuations. This results in the SG incurring substantial operational expenses and costly frequency deviations. With the assistance of UFLS, SG effectively handles significant power interruptions. It is feasible to implement load shedding and partition the electrical system using Load Allocation Areas (L.A.A.s)94. Table 9 provides a comprehensive list of several approaches for identifying Local Area Areas (L.A.A.s), including observers and model-free defensive frameworks.

Load redistribution attack

The authors of this article devised a method known as load redistribution, which has a resemblance to state estimation-false data injection. While attacks on L.R. do not alter the total power demand, they do impact the electrical flow and load bus measurements. A reallocation of resources is necessitated by the heightened demand on the network caused by the attack. The potential consequences of L.R. include not only financial damages but also bodily injuries, such as stumbling over electrical wires or experiencing violent attacks. Utilizing hacking techniques could be a viable solution for L.R. to prevent power disruptions and resolve the SCED problem97. Furthermore, there are two specific types of attacks associated with load-shedding: one that exploits the immediate operating expenses of load-shedding, and another that exploits the Systemic Control of Electrical Devices (SCED) to activate the solution by tripping lines, which is then postponed98. Table 10 provides a comprehensive list of several methods, including support vector models, closest neighbor identification techniques, and ML-based approaches, for identifying Local Registers (L.R.A.s).

Replay attack

Intercepting wireless data, assuming the identity of an authorized sender, and combining the intercepted data with the first dispatched data comprise a replay attack. This sort of assault relies on cognitive awareness, making it harder for the supervisor to spot. This disrupts electrical energy transmission, delaying alternating frequencies owing to the attack. A replay attacker may interrupt the system and prevent it from performing its operational functions101. Replay attacks with Stux Net were used to access the centrifuge SCADA system. This caused the centrifuge control system to corrupt, rendering 1000 centrifuges inoperable102.

The research implies that deliberately adding noise to the control input may prevent reflected replay assaults. This strategy failed. Game theory provided a dynamic control input that synchronized noise production in another investigation. Table 11 details R.A. identification processes. The methods include the support vector model, ML, and radar antenna nearest neighbor identification103.

Cybersecurity solutions for SG

This section explores potential approaches to safeguard satellites from cyberattacks by utilizing blockchain technology and artificial intelligence technologies such as ML and DL. The selection of these techniques was based on their remarkable capacity to independently identify intricate patterns. Each of these methods is enumerated below.

BC techniques in SGs based on cybersecurity

Smart energy systems may manage contracts and transactions with blockchain technology to prevent hacks and boost self-regulation. In traditional power systems, a successful attack compromises the meter record, data packets, fraudulent energy trading payments, and control center. BC protects SG from cyberattacks108. By identifying Blockchain-based attacks, Table 14 highlights published research on cybersecurity in Smart Grids (SGs) by objective, kind, solution, consensus methodologies, Smart Contract deployment, and performance evaluation criteria109.

In SGs, ArMor uses Bayesian calculation to discover the negative impacts of A.M.I. and S.M. System aimed to discover integrity issues caused by smart meter failure and FDI attacks. This paper proposes a decentralized Ethereum Blockchain solution to DDoS and SPoF. The authors presented a blockchain-based smart grid energy transaction confidentiality solution. Blockchain-based SG used PBFT consensus. The decentralized technique presented by authors110 effectively identified replay problems while simultaneously safeguarding the privacy of local data. To enhance the security of SG systems against cyberattacks, they advocated for a consensus-based approach.

In a similar vein, the developers of secure Smart Grid components leverage Blockchain technology. Miners utilize their computational capabilities to authenticate transactions. Throughout every energy transfer transaction, the rights of the consumer are upheld. The realistic threat model created by111 sought to deter a compromised secure gateway from detecting foreign direct investment (FDI) activities and encourage the submission of accurate data by penalizing users who provided inaccurate or missing information.

Blockchain-based security solutions improve smart grid protection by leveraging decentralized authentication, distributed consensus, and smart contract deployment. These mechanisms ensure enhanced resilience against cyber threats by eliminating single points of failure and providing tamper-resistant records of transactions. However, blockchain implementation in smart grids introduces certain trade-offs in terms of computational costs and transaction processing time. Unlike traditional security mechanisms, such as centralized access controls, encryption-based authentication, and rule-based fraud detection, blockchain solutions incur higher latency due to consensus verification processes but offer improved security guarantees. Additionally, while blockchain-based security frameworks provide enhanced scalability in decentralized architectures, the cost of implementation and maintenance can be higher compared to conventional security methods. Table 12 illustrates the comparison between blockchain-based solutions and traditional security approaches in terms of latency, cost, and scalability, providing insights into their respective advantages and challenges in smart grid environments.

Blockchain application in smart grid

Blockchain technology gained popularity due to Bitcoin, which is now widely accepted by researchers from many fields. The various BC systems were built after the blockchain for bitcoin was created. Blockchain that are federated, private, and public are among the numerous BC platforms. There are a few technical differences between these three kinds of BC119. Public blockchain that are frequently observed these days include Ethereum and Bitcoin. Any user can participate on any node with any publicly available BC type. As a result, everyone using the public blockchain will be able to see every transaction120.

The second kind, private BC, limits participants’ access to transaction information. A node on a private blockchain cannot engage in a transaction or access pertinent data until it is given access privileges. Thirdly, both public and private BC characteristics are present in federated BC. SG’s introduction made several uses in the energy industry possible121. A participant in the Energy Service Network (ESN) or Smart Grid (SG) can conduct peer-to-peer energy trade, such as selling electricity, and create invoices through the use of smart contracts based on blockchain technology. An ESN platform’s ability to store transactions is essential to the peer-to-peer model. Peers include prosumers, consumers, regulators, and those involved in power transfers. Although the centralized architecture has proven to be dependable, as trading volume increases and data interchange volume increases, it may become vulnerable to attacks, resulting in inefficiencies and a single point of failure. The BC servers are essential to the decentralized power grid because they maintain trust and log every transaction. A key principle of BC is the trust mechanism, which blocks the spread of corrupted data. A permission-less or public blockchain, which is a system without access restrictions, requires resources like fuel and processing power, therefore one must take those into account when adding new data22.

In the consensus proof-of-work (PoW) process, nodes solve the hash code and verify one another with one another. In the Proof of Work (PoW) consensus, adding more data (the following block) raises processing costs. A decentralized computer system provided by a blockchain allows for peer-to-peer communication in the absence of a central authority. In order to offer accuracy, effectiveness, and security without the need for middlemen, BC-based systems continue to rely on predetermined rules. Researchers continue to face a number of unresolved issues on the BC platform, despite constant advances and problem-solving efforts. The number of automated decision support systems122 has increased dramatically in the past several years. In this case, a blockchain can be helpful in keeping track of decisions and actions by completing the proof-of-work required to add a validated block to the chain. These tools can also be used to establish a mining approach’s proof-of-work. By using ML algorithms, unusual or malicious activity on the BC can be quickly detected. There will be a number of immersive applications and synergies between blockchain (BC) and ML. When it comes to data mining and safety procedures, the two systems can collaborate. By using Big Data-driven AI solutions through BC, an accurate and thorough decision database may be created for continuous system performance assessment. Decision-making may be tracked at various stages when a process is included into a business continuity paradigm, and artificial intelligence (AI) systems may use sensor data for analysis123. The security and accuracy of data in British Columbia might be greatly increased by implementing big data technology. Proponents of the BC paradigm contend that both are essential. By ensuring privacy and uniqueness, BC implementation should increase the efficiency and reach of data transfer. By independently carrying out the common transaction procedures, an “intelligent contract” eliminates the need for a middleman. Creating autonomous smart contracts that let the buyer and seller manage the sale and payment procedures securely and independently could be one way to implement smart energy systems. Blockchain technology in smart grids may benefit our current and future energy systems in several ways. Due to its tight relationship to the features and workings of the blockchain, the electrical system contributes significantly to the benefits of the decentralized trade network. Less red tape and improved computing power are two of blockchain’s main advantages when it comes to Enterprise Social Network (ESN) features and principles of operation. Moreover, it encourages decentralization, greater security, robustness, openness, and scalability.

AI techniques in SG based on cybersecurity

The implementation of artificial intelligence techniques has the potential to enhance the reliability and resilience of intelligent grid systems. This paper presents the authors’ comprehensive approach to safeguarding against SG attacks using DL and ML techniques.

Cybersecurity techniques in SGs based on DL

When traditional methods are unable to extract useful features, DL models employ more sophisticated training techniques. The phenomenon known as the dimensionality curse presents significant challenges in the successful elimination of essential characteristics. Ultimately, several DL methods successfully addressed the task of safeguarding sensor-gated networks124. This architecture incorporates a concealed fully convolutional layer, as well as two pooling layers, an output layer, and two convolutional layers. Previous studies have utilized several DL approaches, including recurrent neural networks (R.N.N.s), artificial neural networks (ANNs), and deep neural networks (D.N.N.s), to investigate SG attacks. By employing a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and the Kalman filter, the authors of the paper developed a technique for identifying FDIA.

To detect an FDI attack, the dynamic threshold was continuously monitored. A technique for determining the FDIA (Focal Design Index) for gas-fired producing and power-to-gas facilities is provided in reference53. The proposed approach utilized the IN and OUT signals supplied by the facility scheduler. To enhance the detection of FDIA, a hybrid neural network was employed47. In this specific case, the training data lacked any labels. Presented in Table 15 are the accuracy and DL models employed in cyberattacks. Furthermore, the authors identified vulnerabilities in the IEC 61,850 communication standards by using DL techniques. We developed a framework for detecting energy theft, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) approach to ensure energy privacy in Software-Defined Generators, and a Paillier algorithm.

DL models face computational constraints when deployed in real-time smart grid applications. The latency introduced by high-dimensional data processing, the need for significant computational power, and the limitations of traditional infrastructure create challenges in implementing DL-based cybersecurity solutions. Real-time IDS in edge and fog computing environments require lightweight yet efficient models that can process large-scale network traffic without introducing excessive delays. To mitigate these issues, recent studies have explored lightweight AI models such as MobileNet, XGBoost, and federated learning-based approaches, which optimize security detection while reducing computational overhead. These approaches allow for distributed learning while preserving data privacy and minimizing bandwidth consumption.

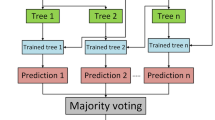

In this paper, an IEEE 1815.1-based Intrusion Detection System (IDS) for a power system is described. A DL system utilizing a bidirectional recurrent neural network (R.N.N.) was used to detect outliers, evaluate their importance, and provide a grade to the suggested approach. The GAN architecture successfully identified several threat categories, including as malware, foreign direct investment (FDI), and attacks that impede reassembly. To identify foreign direct investment (FDI) attacks that cause congestion in transmission lines in Singapore and evade state estimate, the researchers employed a DL-based neural network model125. The researchers implemented ensemble-based DL to identify false positives. The measurements obtained during the adjustment of the window were utilized to train multiple DL models. An ensemble-based detector utilized the ideal model to detect erroneous readings. To facilitate the detection of energy theft by SGs, researchers developed a classification method utilizing D.N.N. The employment of a Bayesian optimizer to selectively enhance and refine the hyper parameters significantly facilitated the detection of instances of energy theft126. The methodologies for DL-based cyberattack detection in smart grids are outlined in Table 13.

ML-based cybersecurity techniques in SGs

The detection and investigation of potential cybersecurity vulnerabilities by SGs are accomplished through the utilization of ML methodologies. The authors investigated the feasibility of employing ML to identify breaches on smart meters, perhaps resulting in a rise in energy bill costs. In their study, the authors of reference132 did not employ ML to forecast future electricity costs. Following the cleaning and arrangement of the data, many methods such as joint mutual information maximization, kernel principal component analysis, and principal component analysis were employed to extract features133. Following the extraction and selection of features, the model underwent training using ML techniques.

The training ML model was responsible for the produced results. A ML-based approach was proposed to identify foreign direct investment (FDI) hacking in state budget estimates. Ensemble learning implements both supervised and unsupervised classifiers as a means to address the challenges associated with dimensionality reduction. To underscore the differences between a physical grid and a data update, the authors conducted a comparison between the two. To produce historical data and assess it for idea drift resulting from changes in data distribution, the initial coefficient analysis was employed. Furthermore, the K-NN approach was employed to showcase the system’s value, achieving the maximum achievable level of accuracy134. One potential strategy for detecting covert attacks is to combine kernel principal component analysis with the technique of the highly randomized tree. The authors utilized SVMLDT to identify anomalies in the SG. Following an assault, remedial actions were taken, and a technique known as adaptive load rejection was used to mitigate the effects of denial-of-service attacks135. The data integrity attacks that were analyzed included pulse, ramp, replay-trip, and replay. The effectiveness and ML techniques employed for the detection of cyberattacks are presented in Table 14.

A novel abnormality detection and mitigation paradigm was provided. ML algorithms K.N.N. and D.T. classified assaults with 96.5% accuracy. This study introduces a cyber-physical anomaly detection system for communication and data integrity threats. This classification model uses D.T. ML with variation mode decomposition. CPADS was tested using the IEEE 39 bus design, the standard. The authors investigated foreign direct investment fraud detection using ensemble and extreme ML. The authors used a FLGB ensemble classifier to automatically recognize FDIA behavior using optimal parameters144. Extreme ML began with Gaussian weight selection. Foreign direct investment and denial of service assaults were classified using hierarchical clustering, hindering the state estimation approach. The authors used the D.T. algorithm with Kalman filters to create an accurate, efficient, and risk-reducing strategy. Foreign direct investment risks were identified using ML methods like data visualization, categorization, and aggregation145.

SGs use ML to find cybersecurity flaws. The authors studied using ML to identify smart meter breaches, which could raise energy bills. The author of the89 did not use ML to predict electricity bills. SG components are shown in Fig. 9.

Following the cleaning and arrangement of the data, many methods such as joint mutual information maximization, kernel principal component analysis, and principal component analysis were employed to extract features90. Following the extraction and selection of features, the model underwent training using ML techniques. The training ML model was responsible for the produced results.

A ML-based approach was proposed to identify foreign direct investment (FDI) hacking in state budget estimates. Ensemble learning implements both supervised and un-supervised classifiers as a means to address the challenges associated with dimensionality reduction. To underscore the differences between a physical grid and a data update, the authors conducted a comparison between the two. To produce historical data and assess it for idea drift resulting from changes in data distribution, the initial coefficient analysis was employed. Furthermore, the K-NN approach was employed to showcase the system’s value, achieving the maximum achievable level of accuracy91. One potential strategy for detecting covert attacks is to combine kernel principal component analysis with the technique of the highly randomized tree. The authors utilized SVMLDT to identify anomalies in the SG. Following an assault, remedial actions were taken, and a technique known as adaptive load rejection was used to mitigate the effects of denial-of-service attacks91. The data integrity attacks that were analyzed included pulse, ramp, replay-trip, and replay.

A unique paradigm for the detection and mitigation of abnormalities was also presented. K.N.N. and D.T., two ML algorithms, achieved a degree of accuracy of 96.5% in classifying attacks. This paper introduces a cyber-physical anomaly detection system designed to identify threats targeting communication and data integrity. This classification model was constructed using the D.T. ML approach with variation mode decomposition. An assessment was conducted to determine the effectiveness of CPADS utilizing the IEEE 39 bus design, which forms the standard. By employing ensemble and extreme ML techniques, the authors also explored the feasibility of detecting foreign direct investment fraud. By employing a FLGB ensemble classifier, the scientists automatically detected FDIA behavior using an optimal set of characteristics92. A first stage in extreme ML involved the random selection of weights from a Gaussian distribution. Hierarchical clustering was used to classify foreign direct investment and denial of service attacks, which significantly hindered the state estimate approach. The authors employed the D.T. algorithm and Kalman filters to develop an approach that achieved both accuracy and efficiency, while simultaneously reducing potential exposure to risk. The authors utilized ML techniques such as data visualization, categorization, and aggregation to identify foreign direct investment risks93. Table 15 presents the efficacy of various ML algorithms in detecting cyberattacks.

It is important to note that this study does not involve experiments with human subjects or any form of personal data collection. Furthermore, although our proposed AI-Blockchain hybrid framework is supported by extensive theoretical and empirical literature, it has not yet been deployed or validated in a real-world smart grid environment. These aspects remain open challenges and are part of our future research agenda.

Application of blockchain and artificial intelligence

Blockchain adaptation in the real-time energy sector

Utility and energy firms have recently started several projects utilizing BCN technology. Energy trading that is safe and transparent is the main use case for the BCN platform. Peer-to-peer transactions using strong encryption and distributed consensus are covered by this. It can be useful for grid maintenance, tracking carbon emissions, renewable energy certificates, tokenization techniques, and IoT integration, among other applications149. Although the objectives remain accessible, current programs have yet to develop to the point where they can fully support them. Significant modeling and testing continue to ensure project reliability, stability, and feasibility. Below, we examine some of these initiatives and explicitly connect them to AI and blockchain techniques discussed earlier in the manuscript.

Tennet

TenneT established a transmission system operator (TSO) in 2017 to manage electricity throughout Europe. The initial members were the Netherlands and Germany. In collaboration with IBM and Venderbron, TenneT developed a blockchain-based system to manage the electrical networks between these two countries. The system allows distributed energy sources to provide grid balancing services, ensuring that renewable energy sources are integrated efficiently. By leveraging blockchain’s decentralized ledger, this system enhances real-time data verification and energy transaction transparency, aligning with the blockchain-based smart grid security techniques discussed in Sect “Results”150.

LO3 energy

The Brooklyn Microgrid (BMGD) project, run by LO3 Energy in partnership with Centrica, Consensys, and Siemens, enables peer-to-peer energy trading using blockchain. This private blockchain network utilizes the PBFT consensus mechanism, built on Ethereum’s smart contract functionality, to facilitate secure transactions between consumers and prosumers151. AI algorithms integrated into the system predict energy demand patterns, optimize energy distribution, and ensure real-time transaction validation. Exergy, an extension of the LO3 project, employs AI-powered grid cloud management to reduce energy loss, detect anomalies, and automate overload responses, demonstrating the synergy between AI and blockchain in smart grid applications152,153,154.

Alliander and spectra

Alliander, a Dutch energy network operator, has implemented a peer-to-peer energy-sharing platform called Juliette, developed in collaboration with Spectral Energy. The project, deployed at De Ceuvel in Amsterdam, enables real-time energy transactions using blockchain tokens. The system relies on distributed AI algorithms to analyze grid congestion patterns, optimize trading strategies, and enhance security through automated fraud detection mechanisms155,156,157. By integrating blockchain for secure transactions and AI for data-driven optimization, this initiative highlights real-world implementations of the techniques proposed in Sect “Results”.

Motion Wrek

The German startup MotionWerk launched the Share & Charge project, utilizing blockchain for decentralized electric vehicle (EV) charging management. This system enables secure transactions between EV owners and charging station providers, facilitating transparent billing and decentralized roaming services158. MotionWerk’s AI-driven predictive analytics model optimizes charging station availability, energy pricing, and load balancing159, reducing grid strain while ensuring fair energy distribution. This use case demonstrates the practical integration of AI for real-time grid management and blockchain for secure transaction processing, reinforcing the methodologies outlined in Sects “Results” and “Algorithms used in smart grid”.

Artificial intelligence application

The advanced metering infrastructure (AMI) of smart grids generates significant volumes of data, which AI techniques can leverage to improve situational awareness, predict grid failures, and optimize energy efficiency. AI is particularly useful for small and medium-sized prosumers who have limited control system budgets but still require automated decision-making capabilities to efficiently manage their energy consumption and production160.

Game theory

AI-driven game-theoretic models improve decision-making in energy markets, enabling dynamic pricing, optimal resource allocation, and enhanced grid stability. Stackelberg and Cournot models, discussed in Sect. 4, have been successfully applied to optimize energy bidding strategies, reduce market manipulation risks, and ensure fair pricing161,162. These techniques support peer-to-peer energy trading platforms, such as those used by LO3 Energy and TenneT, by automating contract negotiations and minimizing transaction disputes.

Optimization approaches

AI-driven heuristic algorithms, such as genetic algorithms (GA), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and artificial immune systems (AIS), optimize energy distribution, fraud detection, and network resilience163,164,165. These methods enhance the real-time efficiency of blockchain-based energy trading platforms by ensuring that grid operations remain balanced, responsive, and secure. For example, Alliander’s AI-enhanced blockchain platform benefits from real-time optimization techniques to improve energy distribution accuracy and prevent grid congestion issues166.

Power generation forecast of renewable energy

Given the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources, AI-based long short-term memory (LSTM) networks and DL models improve energy generation forecasts, ensuring better integration of renewables into the grid. TenneT’s blockchain-based grid management system, for instance, incorporates AI-driven energy forecasting models to predict supply-demand fluctuations, reducing energy curtailment and enhancing system resilience167,168.

Research and implementations

Recent studies have applied game-theoretic optimization models and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms to enhance grid reliability, reduce carbon emissions, and maximize financial incentives for prosumers169,170. The application of these AI models to blockchain-secured smart grids has demonstrated tangible benefits, including improved transaction transparency, reduced operational costs, and increased energy trading efficiency. Real-world implementations, such as LO3 Energy’s Exergy platform and MotionWerk’s Share & Charge network, showcase how these AI-driven models facilitate practical energy management solutions171.

Lessons learned and performance outcomes

The integration of AI and blockchain in energy systems has demonstrated significant improvements in efficiency, security, and transparency. AI-driven models have proven to be invaluable for predicting energy demand, detecting anomalies, and preventing fraud. These applications enhance the accuracy and responsiveness of decentralized energy trading systems, ensuring fair and optimized market conditions.

Blockchain technology ensures secure, tamper-proof transactions, protecting against fraud and unauthorized access. However, while blockchain enhances transaction security and transparency, its computational requirements introduce latency and scalability challenges. AI plays a crucial role in optimizing blockchain efficiency, reducing delays, and enhancing adaptability to dynamic grid conditions.

The combination of AI and blockchain, as demonstrated by projects like LO3 Energy and Alliander, improves decentralized grid management by ensuring data integrity, automation, and secure peer-to-peer transactions. These hybrid systems help balance security concerns with computational scalability, allowing for broader adoption in smart grid applications.

Despite these advancements, future research must focus on developing lightweight AI models that integrate seamlessly with blockchain consensus mechanisms. This will enable real-time decision-making, improve transaction speed, and enhance system efficiency without compromising security. Additionally, further empirical validation through pilot projects and controlled test environments will be essential to measure scalability, interoperability, and long-term economic benefits of these technologies.

Algorithms used in smart grid

Inter-chain SC algorithm

One use case exists for the majority of these technologies, and that is token technology. If a condition is present in another BCn, unfortunately, there is no method to apply a SC to one of them. In the case of non-SC transfer assets, such as Bitcoin, the amount paid is “frozen” on a SC to show who owns it. This means that another work chain can enforce a characteristic of a SC both inside and outside of it172. Put yourself in the shoes of a user who wishes to move data from Ethereum to Polygon. Polygon provides cheaper storage than Ethereum does per unit of space. Notices of SC are broadcast through the Polygon’s DSL whenever an Ethereum node crates. In order to confirm its legitimacy and the likelihood of condition completion, the DSL will invite a set number of miners173.

The result is then displayed to the customer. The transaction is completed, and the miner receives payment from the customer’s charge for validating the data. In this scenario, the penalty the false data source must pay will compensate the miner. To validate the effectiveness of the inter-chain SC algorithm, further research and simulation are required to assess key performance indicators such as transaction finality time, miner verification success rates, and fraud detection efficiency174. Future experimental setups should evaluate how smart contract enforcement across chains influences security and efficiency175.

The pseudo-code aims to outline the process for transferring data from Ethereum to Polygon, leveraging a smart contract to enforce conditions across blockchains. This process involves smart contract notifications, miner verification on the Polygon network, and compensation mechanisms for data validation.

This pseudo-code represents a high-level overview of the process. It begins with the definition of smart contracts on both Ethereum and Polygon networks, followed by a function `TransferData` that manages the data transfer process. This process includes posting the transfer request on Ethereum, notifying the Polygon network, selecting miners for verification, and handling the transaction’s completion based on the verification results. Miners are compensated for their verification efforts, with penalties applied to sources of false data as necessary.

This algorithmic representation is simplified and would require detailed implementation specifics, including handling communication between blockchains, defining DSL (Domain Specific Language) notifications, and setting up secure and effective compensation and penalty mechanisms. Further, actual implementation would require a deeper integration with the blockchain platforms’ APIs and security protocols.

Instant standardization algorithm

The traded prices are stable and unchanging since every network employs a unique procedure. The criteria will be used to determine the transaction fee and exchange rate. Finding a single coin to serve as the de facto standard will further centralize the network, as has happened with all previous monetary systems176. Everyone else will back the BCN in charge of the funds. A regulatory agency is also needed to keep an eye on the value of each currency within the BCn system’s dominant currency. Here, precise evaluation of the value of the money may prove challenging.

In order to solve this issue and make future interoperability easier, we implemented an algorithm to assess the privacy, speed, scalability, security, and inter-chain linkages of any two or more networks177. The proposed approach requires further empirical validation through controlled simulation environments to assess its ability to improve interoperability while avoiding centralization178. Key performance indicators such as transaction latency, exchange rate stability, and computational efficiency should be examined in future studies179.

The Instant Standardization Algorithm’s pseudo-code includes the framework for creating a universally accepted transaction fee and exchange rate for use in various blockchain networks. This ensures cross-blockchain transactions remain efficient without relying on third-party regulatory bodies.

This pseudo-code illustrates a high-level approach to determining and using a standard currency for transactions involving multiple blockchain networks. The process begins with evaluating each participating blockchain’s attributes to identify which one offers the best combination of security, speed, scalability, transparency, and privacy. The blockchain network (BCN) with the highest score is selected as the standard for that particular transaction. The transaction is then executed using the currency of the chosen standard BCN, applying an established exchange rate and transaction fee.

This method promotes competitive improvement among blockchains by incentivizing them to enhance their performance standards to become the standard currency for more transactions, thereby avoiding centralization and eliminating the need for third-party regulation. Actual implementation would require detailed mechanisms for evaluating blockchain attributes and integrating with various blockchain networks to conduct transactions seamlessly.

In-system bridge mechanism

This bridge allows nodes to transfer tokens and other data between chains and networks. It makes it possible for a token to interact with another chain. Tokens are a virtual representation of the assets generated on another BCN using different coins or money. Tokens reflecting one’s network currency can be freely exchanged in any other BCn network. Today, many BCNs communicate across chains using well-liked bridge solutions, such as Binance Bridge, xPollinate, Matic Bridge, and Multi-chain. However, as previously mentioned, they are primarily developed and run by several organizations or businesses69.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the in-system bridge mechanism, experimental analysis is necessary to examine transaction execution speed, bridge security, and miner efficiency180. Future testbed implementations should focus on assessing how this approach impacts transaction completion times and its ability to enhance security in decentralized cross-chain communication181.

For the In-system Bridge Mechanism here, the goal is to enable seamless token and data transfer across different blockchain networks (BCNs) without relying on centralized intermediaries. The mechanism relies on in-system miners as verification agents, ensuring decentralization and reducing dependency on third-party validators182.

This pseudo-code provides a framework for a decentralized, in-system bridge mechanism that facilitates token and data transfers across blockchain networks by utilizing a network of miners as intermediaries. This approach ensures security, privacy, and transaction validity by leveraging the blockchain’s decentralized nature and avoiding centralized control points.

The process begins by deploying the bridge based on the request, followed by the selection of intermediary miners from both the source and target blockchains. These miners are responsible for validating the transaction on both ends, ensuring the tokens or data are locked and then transferred securely across chains. The successful execution of the transaction rewards the intermediary miners, incentivizing their participation and ensuring the bridge mechanism remains decentralized and autonomous.

Issues in the smart grid

Scalability issues

Currently, available consensus techniques include PoW and PoS, both of which make it extremely difficult to complete a transaction or create a block. The workers utilized a great deal of power, and their numbers are continually increasing. As a result, the SGES gains additional nodes, or users169. To keep up with the increasing number of users, it will need to adhere to specific guidelines. In this case, the SGES might not be able to grow178. Furthermore, the current BCN approach hides centralization while allowing the SGES to grow. This is due to the possibility of concentrated mining power in the hands of one or a small number of companies, which prevents miners from other regions from joining. The lack of heterogeneity and interoperability features in the current BCN-enabled system is another factor impeding SGES’s quick expansion. In this scenario, it is imperative to modify the current BCN network’s design to achieve significantly greater scalability179.

Cost inefficiency