Abstract

While the Kuroshio, a western boundary current in the North Pacific, transports a large amount of nutrients in dark subsurface layers, it remains elusive whether and how these subsurface nutrients are supplied to continental shelves along southern coast of Japan. Recent observations revealed that the upstream Kuroshio flowing through rough topography forms a large-scale turbulence hotspot that may supply nutrients to sunlit surface layers. However, the Kuroshio-Island interaction in this region may also induce eddies and nutrient upwelling which have neither been observed directly nor quantified. Here, through high-resolution in-situ observations, we show submesoscale ∼10 km nitrate structures along isopycnals, suggestive of eddy-induced upwelling. High-resolution simulations reproduce these features generated by submesoscale cyclonic eddy-induced nitrate upwelling at O(10) mmol N m−2 day−1, accounting ∼ 9% of net primary production in the area 400 km downstream during non-stratified season. Ecosystem model results suggest that rapid small zooplankton grazing could suppress the small phytoplankton increase, leaving a large fraction of supplied nitrate remain unused while it is carried by cyclonic eddies. These rather complex responses of lower trophic level ecosystem associated with submesoscale eddies in the upstream Kuroshio may partly explain how the Kuroshio sustains high biodiversity and biological production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Kuroshio Current is a strong western boundary current in the North Pacific, essential for the transport of large amounts of water, heat, and tracers from tropical to subarctic regions1,2. The Kuroshio accommodates large biodiversity within the main stream and its adjacent waters, supporting important spawning and nursery grounds for pelagic fish3 and good fishing areas4,5. In addition, the Kuroshio region has been found to be one of the major net CO2 sinks for the atmosphere6. However, this vast ecological and carbon hotspot is inconsistent with the oligotrophic Kuroshio waters (‘Kuroshio paradox’4). The Kuroshio waters present significant lateral nitrate flux in the subsurface layers with a maximum at σθ = 26 kg m−37,8, similar to the Gulf Stream9. Nitrate is considered to be a primary limiting macronutrient, particularly in nutrient-depleted subtropical regions, where its availability constrains photosynthesis10,11. Therefore, the supply of nitrate to the euphotic zone is a key factor in regulating phytoplankton growth in these oligotrophic Kuroshio waters. Several microstructure observations have revealed elevated turbulence generated when the upstream Kuroshio flows over topographic features12,13,14,15,16,17. The generated turbulence can spread laterally over 100-km along the current across the Tokara Strait18 with associated nitrate vertical diffusive flux of O (1) mmol N m−2 day−119,20,21, ten times greater than the nitrate diffusive flux observed in the Kuroshio Extension region22,23 and that estimated in the regions between the Brazil Current and the intermediate western boundary current24. On the other hand, other nutrient supply routes can also arise through adiabatic vertical motions (up/downwelling) with fine spatial scales of < O(10) km, submesoscale, in regions of intense vorticity and deformation, e.g., near eddies and fronts25,26,27,28, possibly impacting on the ecosystem29 from plankton30 to fish31. Despite the importance of submesoscale processes in the nitrate supply, they pose challenges for observations and numerical models due to their small spatial and temporal scales. Although recent high-resolution simulations and observations indicate that submesoscale vertical motions can result from the interactions between flow and topographic features31,32,33, there is no sufficient observational evidence of such nitrate supply in the region south of Japan, where the Kuroshio Current directly interacts with island topography. To address this gap, this study involved a series of intensive high-resolution in-situ observations using a-state-of-the-art twin tow-yo system to profile microscale turbulence and biochemical parameters. Additionally, high-resolution numerical simulations coupled with a N2P2Z2D2 ecosystem model were performed to reproduce the observed physical and biological structures at a submesoscale resolution, providing an opportunity to link observations and simulations at this scale. The objectives of this study are to directly observe and characterize submesoscale nitrate upwelling signatures associated with eddies, to quantify the nutrient upwelling caused by submesoscale eddy activities during non-stratified season (November) off the southern coast of Yakushima Island (Japan, Fig. 1), and to elucidate their effects on the ecosystem, focusing on the primary and secondary producers.

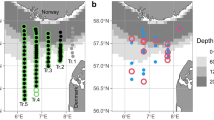

Map of the study area. (a) Topography [m] in color shading with black contours every 1000 m from ETOPO Global Relief Model. Observation lines shown as magenta line for November 2021 research cruise, yellow line for December 2022, and purple line for January 2023. (b) Sea Surface Temperature (SST, in °C) in model November from ROMS simulation. Black square encloses the first nested grid region with a lateral resolution at 1.5 km, and blue square encloses the second nested grid region at a resolution of 700 m. Shorelines extracted from Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution. Geography Database (GSHHG).

Results

Submesoscale structures in the observations

During the November 2021 transect survey, a convex upward structure of high nitrate concentration was captured in the upstream part of the section (black dashed circle in Fig. 2a), right above Yaku-shin-sone seamount at distance 20–40 km, infiltrating nitrate above the mixed layer depth (from now on MLD, as a magenta line) with values above 1.5 µM. Just 10 km from this location, at 130.5° E, the nitrate concentration (\({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\)) showed much lower values above the MLD of less than 0.8 µM. At this location, the top 100-m average ADCP current velocity (black bars Fig. 2d,e, arrows indicate the pattern of velocity direction) changed its direction from southeast to west (white arrow in Fig. 2d) with isopycnals aligned laterally within the mixed layer, indicating a front. Near the end of the transect, \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) of 1.5 µM exhibited a filament extending from 120 m depth to the surface along the shoaling isopycnals, towards downstream with a lateral scale of ∼ 5 km (black dashed arrow in Fig. 2a). Furthermore, elevated turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rates (ε, Fig. 2c) with values of 10−6 to 10−5 W kg−1 were primarily concentrated in the upstream region near the Yaku-shin-sone seamount. The ε values ∼ O(10−8 to 10−7) W kg−1 were observed along the inclined MLD where the tongue of nitrate was observed, and several patches of high values of ε were present in the downstream part within the surface layers. The sea surface temperature (SST) obtained from the GCOM-C satellite at a high resolution of 250 m, captured wavy rotational structures of ∼ O(1–10) km along the edge of the Kuroshio Current delimited by the contours and shade in Fig. 2d,e at the south of Yakushima Island on November 14th, 2021, a few days prior to the survey period, a little further north of the in-situ observation line. Despite the presence of clouds in the vicinity, which resulted in some obscure areas in the satellite data, chlorophyll-a concentrations (Chl a) exhibited a slight increase of 0.1 µg L−1 in the downstream region, consistent with the observed surface chlorophyll-a increase observed in situ up to 0.5 from the ambient concentration of 0.4 µg L−1 (black dashed circle in Fig. 2b).

Vertical sections of November 2021 research cruise. (a) \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration [µM], (b) chlorophyll-a concentration [µ gL−1], and (c) turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate ε [W kg−1], with longitude positions on top abscissa. White/black contours represent isopycnals every 0.3 σθ [kg m−3], and magenta line represents mixed layer depth (MLD). Symbols of ∗ and + represent profile locations for SUNADAYODA and UVMP, respectively. Satellite images from GCOM-C for (d) SST [°C] on November 14th, and (e) chlorophyll-a concentration [µ gL−1] on November 17th. Blues contours in (d) represent geostrophic velocity delimiting > 0.5 ms−1, and in (e) sea surface height (SSH) from CMEMS GLORYS12V1 reanalysis on November 14th. Magenta line in (d, e) represents the observation line, and black bars 100-m average ADCP velocity vectors during the observation time. The tow-yo survey took 3 days and 3 h along the Kuroshio over roughly 150 km. The resolutions of tow-yo profiles vary from 500 m to 3 km depending on the bottom depth. Shorelines extracted from Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database (GSHHG).

In the December 2022 transect, the measured \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) vertical section revealed a chimney-like structure with a scale of 2–3 km, spanning the water column, at 130.68–130.7° E (distance of 17–18 km, black dashed circle in Fig. 3a). In addition, intense ε values O(10−6) Wkg−1 were observed from the surface to 70 m at most where shallow bottom depths (Fig. 3c) limited the maximum depth reached by the tow-yo vertical profiler for microstructures (Underway-VMP hereinafter UVMP, see Methods). The transect coincided with an SST sharp front, presented by the satellite images from the GCOM-C, between water masses of 19 °C and 22 °C (Fig. 3d). ADCP velocities provided further evidence that shows an anticlockwise rotational flow (see the arrows in Fig. 3d). It should be noted that despite the resemblance in spatial distribution patterns between observed Chl a and satellite images, the in-situ observed Chl a values showed much higher values near 1 µg L−1 (Fig. 3b), in the surrounding of the high \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration, 3 µM, compared to the satellite-derived Chl a values that were below 0.5 µg L−1 (Fig. 3e).

Vertical sections of December 2022 research cruise. (a) \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration [µM], (b) chlorophyll-a concentration [µ gL−1], and (c) turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate ε [W kg−1], with longitude positions on top abscissa. White/black contour lines represent isopycnals every 0.3 σθ [kg m−3], and magenta line represents MLD. ∗ and + represent profile locations for SUNADAYODA and UVMP, respectively. Satellite images from GCOM-C for (d) SST [°C], and (e) chlorophyll-a concentration [µ gL−1] on December 31st. Dark contours in (d) represent geostrophic velocity delimiting > 0.5 ms−1, and in (e) SSH from CMEMS GLORYS12V1on the same day. Magenta line in (d, e) represents the observation line, and black bars represent 100-m average ADCP velocity vectors during the observation time. The tow-yo survey took 17 h across the cyclonic eddy structure off the south coast of Yakushima Island. The resolutions of tow-yo profiles vary from 200 m to 5 km depending on the bottom depth. Shorelines extracted from Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database (GSHHG).

The vertical transects measured on January 1st, 2023, off the eastern coast of Tanegashima Island, revealed convex isopycnal structure of 10–15 km from the beginning of the transect associated with \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) uplifts (black dashed arrows in Fig. 4a). In addition to these structures, a blob of low \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) at the distance 5 km of the transect was located between two frontal structures with standing isopycnals (follow purple dashed arrows). A similar, though less intense \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) decrease of ∼ 1 µM was also noted at 25 km, again within a frontal region characterized by standing isopycnals, suggesting not only the presence of nitrate uplifting but also frontal subduction of low \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) surface water. Although ε values remained relatively low < 10−8 W kg−1 compared to the previous transects, there was a noticeable increase up to > 10−6 W kg−1 toward the end of the transect possibly coinciding with another chimney-like structure where, unfortunately, the nitrate data could not be obtained due to a technical problem (white shaded arrow in Fig. 4c). It is in this part of the transect where isopycnals exhibited a frontal structure, characterized by standing isopycnals with a subduction-like structure of elevated Chl a down to 100 m depth (Fig. 4b). The satellite SST image showed a distinct ring of cold water with temperatures below 20 °C off the east coast of Tanegashima Island, where ADCP current velocity data at this location revealed an anticlockwise (cyclonic) rotational flow pattern (see the arrows in Fig. 4d,e), suggesting the presence of a cyclonic eddy.

Vertical sections of January 2023 research cruise. (a) \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration [µM], (b) chlorophyll-a concentration [µ gL−1], and (c) turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate ε [Wkg−1], with latitude positions on top abscissa. White/black contour lines represent isopycnals every 0.3 σθ [kg m−3], thin white contours in (a, b) every 0.1 σθ [kg m−3], and magenta line represents MLD. Satellite images from GCOM-C for (d) SST [°C], and (e) chlorophyll-a concentration [µ gL−1] on December 31st. Black contours in (d) geostrophic velocity delimiting > 0.5 ms−1, and in (e) SSH from CMEMS GLORYS12V1 dataset on December 31st. Magenta line in (d, e) represents the observation line, and black bars represent 100-m average ADCP velocity vectors during the observation time. The tow-yo survey took 17 h across the cyclonic eddy structure off the east coast of Tanegashima Island. The resolutions of tow-yo profiles vary from 1 to 15 km. Shorelines extracted from Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database (GSHHG).

A convex upward nitrate structure infiltrating into the mixed layer, nitrate tongues extended along tilted isopycnal, and the length scales seen in the both in-situ and satellite observations were within the submesoscales, suggesting the existence of submesoscale vertical advective processes caused by submesoscale cyclonic eddies. In our observations, positive and negative correlations between nitrate and chlorophyll-a concentrations were confirmed above the MLD (Supplementary Fig. S1). As nitrate concentrations increased above the MLD and the euphotic depth, they became available to phytoplankton for consumption accompanied by an increase in Chl a, presenting a positive correlation as an initial response, which seemed to be the case for observations in November 2021 (Supplementary Fig. S1a) and December 2022 (Supplementary Fig. S1b) in the cyclonic eddies close to the generation site. However, prolonged nitrate supply caused by cyclonic eddies does not necessarily ensure the positive correlation between nitrate concentrations and Chl a, as zooplankton grazing could reduce phytoplankton, resulting in a negative correlation (Supplementary Fig. S1c). A negative correlation between these nitrate and Chl a was found within the submesoscale cyclonic eddy off the east coast of Tanegashima Island, which most likely has been advected northeastward for several days after the generation at the south of Yakushima Island. Broadly, nitrate supply can be associated with elevated phytoplankton immediately after nutrient supply or with low phytoplankton concentrations as new production is rapidly transferred to zooplankton, thus maintaining the characteristic dark blue watercolor in the Kuroshio region4.

Although our tow-yo observations allowed us to capture lateral and vertical submesoscale features, spatial and temporal coverages are still limited. The GCOM-C satellite SST data have wider spatiotemporal coverages at the surface, but the presence of clouds could easily prevent continuous observations. Since submesoscale processes evolve rapidly within days to a week, these observational limitations always hinder the search for the submesoscale features. Because of this, we cannot rule out the possibility that the in-situ observed nitrate tongue on November 17th could be attributed to the wavy structures in the satellite data on November 14th, 2021. Also, the cyclonic eddy that successfully resolved at the end of December 2022 off the east coast of Tanegashima Island may have been advected by the Kuroshio from the region off the southern coast of Yakushima Island.

Therefore, we conducted numerical simulations from September through December, aligning with the period of observation, to track and analyze the origin and progression of submesoscale structures accurately. The model reproduced the observed Kuroshio well, comparing daily satellite data with the daily averaged model output for temperature and sea surface height with high correlation (R = 0.6–0.8) and similar standard deviations, despite the fact that the model runs with the climatological forcing, while the satellite data are obtained daily during November 2021 (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S4). The same daily comparison for surface Chl a showed relatively low correlation (R = 0.3) with a higher model standard deviation (Supplementary Fig. S4). This is probably because Chl a is distributed more patchily, depending on the location of submesoscale fronts. More importantly, the vertical distribution of the model \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) with respect to the Kuroshio in the Tokara Strait are found to be consistent with the in-situ data taken along the historical line observation of the Japan Meteorological Agency (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Evolution of submesoscale structures in the simulation

Similarly to the SST satellite images, the hourly output of the simulation with a fine grid resolution of 700 m showed that cyclonic eddies emerged at the south of Yakushima Island during the month of November (Supplementary Movie 1). We chose this month for the following analyses as it exhibited patterns closely aligned with those observed in both the in-situ data and satellite images (Supplementary Figs. S2–S5), and as the model November MLD was consistent with the in-situ observations (Supplementary Fig. S2b–d). In Fig. 5, three different snapshots in the simulation were presented, each showing the formation of a different new cyclonic eddy (Eddy-A in Fig. 5a, Eddy-B in Fig. 5b, Eddy-C in Fig. 5c). Eddy A, generated at the beginning of November, persisted near the island for relatively longer periods, which then progressed slowly at a speed ∼ 0.1 ms−1 to the northern downstream. On the contrary, Eddy-B and Eddy-C, formed in early and mid-November, respectively, were detached from the island and veered slightly southward offshore. Before Eddy-B was detached from the Island, Eddy-B was also hovering around the region south of Yakushima Island until mid-November. Once Eddy-B was detached from the island, its propagation speed increased from ∼ 0.1 to 0.2 ms−1, similar to that of Eddy-C. The Eddy-B then traveled downstream alongside Tanegashima Island (Supplementary Movie 1), supporting the proposition that the in-situ observed cyclonic eddy found east of Tanegashima Island originated from Yakushima Island (observed eddy in Fig. 4d). The Kuroshio Current advects cyclonic eddies toward the downstream, with speeds consistent with those of frontal eddies in the Gulf Stream34 and coherent vortices moving toward the Kuroshio Extension region35. At 100 m depth, the density presented two sharp fronts on both sides of the Kuroshio flow: the onshore side, where the meandering flow interacts with the island directly, and the offshore side (Fig. 5g–i). The density variation across both fronts was ∼ 0.5 kg m−3 over distances of ∼ 5 and ∼ 20 km for the onshore and offshore side front, respectively. Due to the horizontal deformation caused by the meander of the frontal jet, the horizontal buoyancy gradients |∇hb| were enhanced for both fronts. On the onshore side, the intensification of |∇hb| was particularly notable at the southern edges of the cyclonic eddies, where only positive relative vorticity was enclosed (Fig. 5d–f). Anticyclonic relative vorticity streaks were also originating on the northern side of the island, which seemed to be entrained to the northwestern edge of the cyclonic eddies. In contrast, vorticity on the offshore side of the Kuroshio in the southwestern part of the model domain showed alternative negative and positive signs, enhanced in magnitudes at the edges of the swirls formed in the lees of Kuchinoshima, Nakanoshima, and Suwanosejima Islands at 129.7°–130.75° E 29.2°–29.8° N.

Eddy formations in the ROMS simulation. Snapshots of the plane view for (a–c) SST [°C] in color and SSH as black contours, (d–f) relative vorticity (ζ) at surface and SSH as black contours, and (g–i) density [kg m−3] at 100 m depth in color with horizontal buoyancy gradient (|∇hb|) as black contours. Shading in (a–f) represents the geostrophic velocity higher than 0.5 ms−1, and vertical line remarks 131° E. Three snapshots are for (a, d, g) November 2nd 23:00 h for Eddy-A; (b, e, h) November 13th 19:00 h for Eddy-B; and, (c, f, i) November 17th 08:00 h for Eddy-C. Shorelines extracted from Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database (GSHHG).

The vertical section in depth for the simulated \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) and Chl a during the presence of the eddies (Fig. 6) along latitude 30.15° N, within the longitudes 130.5°–131° E, then extended northeastward to 30.4° N and 131.3° E (magenta line in Fig. 5a–f) encompassed the area where the eddies were shed and then advected toward downstream. The MLD (magenta line in Fig. 6) appeared around 100 m depth with occasional uplifts to depths of 40–60 m (follow black dashed arrows), near the euphotic depth (thick black line). The euphotic depth (z1%), that is the depth where 1% of the surface photosynthetic available radiation (PAR) remains, was on average above 100 m depth in the simulation, close to previous observations in the Kuroshio36. Along the zonal transect at 30.15° N (before marked longitude 131° E), isopycnals displayed convex upward structures around the center of low SST values within the three presented eddies, accompanied by shoaling MLD. This uplift was correlated with relatively high \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration ∼ 1 µM, particularly above the MLD, comparable to the elevated nitrate concentrations of 1–2 µM observed above the MLD in the Yaku-shin-sone seamount (Fig. 2a). In a different section sliced across the eddy structure in mid-month, tongues of \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration were captured along the shoaled isopycnals and reached the surface layers (Supplementary Fig. S2f). Chl a concentrations were high across the transect above the MLD during Eddy-A (Fig. 6d). Then, by mid-month (Eddy-B and Eddy-C), lower surface temperatures may have slowed phytoplankton growth, making Chl a levels predominantly confined within the eddies, where the isopycnals and MLD were shallow, with values reduced to 0.8 µ gL−1 from that within Eddy-A (Fig. 6e,f). Similarly to the observations, the length scales of the front and eddies generated in the simulation were within ∼ O(1–10) km, filled mostly with positive relative vorticity and surrounded by intense horizontal buoyancy gradients on the onshore side of the Kuroshio. These structures were accompanied by nitrate distributions likely influenced by vertical flows, suggesting the presence of submesoscale cyclonic eddy induced upwelling.

Vertical sections of biochemical parameters in the ROMS simulation. Sections along the magenta line in Fig. 5a–f for a–c \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) [µM], and (d–f) chlorophyll-a concentration [µgL−1]. Magenta line represents MLD, black line for the euphotic zone depth (z1%), and white contours for isopycnals every 0.3 σθ kg m−3. The vertical sections in (a, d) are for Eddy-A; (b, e) Eddy-B; and, (c, f) Eddy-C.

Eddy detection was conducted in the model domain with the highest resolution (see Detecting submesoscale eddies in “Methods”). Within the detected eddies, the vorticity enclosed was only positive and most of them originated behind the islands located in the southwestern region of the domain with considerably smaller diameters below 5 km (Supplementary Movie 1b). Although the eddies generated in the Kuroshio-Yakushima interaction region, 29.8°–30.6° N 130.0°–131.5° E, constituted 30% of all the detected eddies, their diameters were near 10 km and the occurrence of one eddy was approximately every 3 days, in total 6 eddies near Yakushima Island in the model November. Through the detection process, high \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) above 1 µM was identified extending from the MLD to the surface within the eddies. At the edges, the \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentrations decreased noticeably to 0.3 µM with a minimum value of less than 0.1 µM. This pattern was consistent with observations, where \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentrations associated with the upwelling ranged above 1.5 µM, while surrounding waters had much lower concentrations of < 0.5 µM.

Up- and downwelling near/within detected submesoscale eddies

The model nitrate diffusive flux, FNO3 is a product of diffusivity derived from KPP (K-Profile Parameterization) and the vertical gradient of \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration (c.f. Eq.4). The total advective nitrate vertical flux, TNO3 is a product of vertical velocity and \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration (Eq. 9). FNO3 and TNO3 were then obtained during the presence of the eddies-A, B, C (Fig. 7). To investigate fluxes caused by subinertial vertical flow induced by cyclonic eddies, short-term fluctuations were removed by smoothing the hourly fluxes using a 29-h moving average, since the inertial period in the Tokara Strait is 24 h. At 100 m depth, the TNO3 values showed pronounced upwelling and downwelling nitrate fluxes of O(10–100) mmol N m−2 day−1 on the eastern and western sides of the eddies, respectively (Fig. 7a–c). Yet, prominent bands of positive and negative signs were evident on the western side just to the south of Yakushima Island (within a thick green circle in Fig. 7a–c), suggesting their association with stationary lee waves generated in the vicinity of Hirase (30.1° N 130.2° E) and Yaku-shin-sone (30° N 130.5° E) seamounts. The vertical section of TNO3 along the magenta line in Fig. 7a–c revealed that the TNO3 values traversed through mean pycnocline and MLD (magenta lines in Fig. 7d–f) for all the three eddy events, with an upwelling pattern at a horizontal scale O(10) km at 130.8°–131° E. On the other hand, model FNO3 values were O (1–10) mmol N m−2 day−1 (Fig. 7g–i), less intense compared to the magnitude of TNO3 values and predominantly above the MLD. The model FNO3 below MLD showed much lower values than that in the observations during December 2022 (not shown), probably due to the observed transect was much closer to Yakushima Island with a much shallower bottom (Fig. 3c).

Nitrate fluxes in ROMS simulation. Plain views of 29-h moving average of TNO3 at 100 m depth for (a) Eddy-A, (b) Eddy-B, (c) Eddy-C, with black contours that represent SSH. Along the magenta transect in (a–c), vertical sections of (d–f) TNO3 [mmol N m−2 day−1] and for (g–i) FNO3 [mmol N m−2 day−1], with white/black contours for isopycnals every 0.3 σθ kg m−3 and magenta line for MLD. Position 131° E where the transect turns northeastward is delimited.

To identify the processes that may govern the vertical motions observed during the eddy events described above, the values of the frontogenetic parameter (FP, to determine frontogenesis/frontolysis, Eq. 6) and potential vorticity (PV, Eq. 8) were averaged within the detected eddies in the Kuroshio-Yakushima interaction region at both surface layer (Fig. 8a–c) and 100 m depth (Fig. 8d–f). A frontogenesis tendency (FP > 0) was seen at the southwestern edges of the eddies, with larger FP values at the surface (Fig. 8a), while a frontolysis tendency (FP < 0) was on the eastern side of the eddies for both layers, with greater intensification at 100 m depth (Fig. 8d). Although the PV values presented mainly positive values for both layers, negative PV appeared on the northern edge at the surface (Fig. 8b), coinciding with the eddies colliding directly with the sloping topography near the Yakushima Island during the first days of model November. Although, the TNO3 at surface was more dominated by downwelling flux of ∼ − 10 mmol N m−2 day−1 than upwelling (Fig. 8c), both up- and downwelling fluxes were intensified at 100 m depth as ± 50 mmol N m−2 day−1 with an overall more \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) upwelling flux of ∼ 17 mmol N m−2 day−1 (Fig. 8f). For both depths, the downwelling (upwelling) of nitrate coincided with the frontogenesis (frontolysis) tendency on the western (eastern) side of the eddies. The relative vorticity was positive for all eddies, then, the vertical motions under the frontogenesis/frontolysis conditions are expected to exhibit respective downwelling and upwelling, as they are located on the cyclonic side of the front, which aligns with the deformation-induced ageostrophic secondary circulation37,38.

Results of the eddy detection analysis. Parameters are averaged as function of distance from the eddy center for (a, d) frontogenetic parameter FP [Eq. 6, × 10−11 s−3], (b, e) potential vorticity PV [Eq. 8, × 10−9 m−1 s−1], (c, f) nitrate vertical flux TNO3 [Eq. 9, mmol N m−2 day−1]. Parameters computed at (a–c) surface layer, and (d–f) for 100 m depth.

Drivers of the submesoscale cyclonic eddies in the simulation

Up to this point, we found that the simulated submesoscale cyclonic eddies provided a net nitrate upwelling of ∼ 17 mmol N m−2 day−1 at the base of the ML. Next, we explored the origins of these eddies thoroughly through an energy conversion analysis. The Kuroshio interacted directly with the southwestern coast of Yakushima Island during the first days of the simulation (Supplementary Movie 1), increasing the chances of energy transfer from the mean to the smaller-scale flow. Horizontal shear production (HSP, Eq. 10) computed at 100 m depth indicated that barotropic shear instability was dominant in the first 10 days of the simulation, presenting two geographically fixed peaks at the longitudes 130.4° E and 131.0° E (blue lines in Fig. 9a). During the following days, the intensity of the first peak decreased while a second peak in the downstream part was enhanced, and finally, both peaks decreased but remained moderate values during the last 10 days (green lines in Fig. 9a). Although positive and negative values were seen at 130.2°–130.3° E (black circle in Fig. 9a), right before the first peak, they apparently originated from the small islands located west (Kuchinoerabu Island) and southwest (Kuchinoshima Island) of the domain. On the other hand, during mid-month, energy transfer from the eddy to the mean flow (HSP < 0) was captured right before the second peak (red circle in Fig. 9a) where the Kuroshio changed the direction from southeast to northeast and where the vertical buoyancy flux (BF, Eq. 11) varied the most (red circle in Fig. 9b). Although the BF values did not present geographically fixed peaks (Fig. 9b), its magnitude was amplified between the two fixed peaks of the HSP. Since the simulation was conducted during non-stratified season, month of November, a deeper MLD should have increased the available potential energy and fueled the eddy energy through baroclinic instabilities, which reflected the BF values even higher than that resulting from HSP. Interestingly, the intensified values of BF > 0 appeared to propagate toward the downstream as time progressed, with large positive values on days 1–20 (blue and red lines within the red circle in Fig. 9b) and moderately large values downstream on days 21–30 (green lines within black circle in Fig. 9b).

Development of instabilities in the simulation. Meridionally averaged (a) horizontal shear production, HSP [Eq. 10, m2 s−3] and (b) vertical buoyancy flux, BF [Eq. 11, [m2 s−3] computed every 6 h between latitudes 30.0–30.4° N as a function of longitude at 100 m depth for the days of (blue) 1–10, (red) 11–20, and (green) 21–30. Thick black lines represent monthly mean values.

Effect on primary producers

Analyzing the results of the ecosystem model would prompt a more comprehensive understanding of the source and fate of nitrate and its potential contribution to primary production. To achieve this, we first incorporate the nitrate input from either diffusive (FNO3) or vertical (TNO3) fluxes into the surface layers in time (days) along the transect shown in Fig. 5a–c (magenta line). The FNO3 values above the MLD (Fig. 10a) did not exceed 10 mmol N m−2 day−1, while TNO3 exhibited values of O(10) mmol N m−2 day−1. TNO3 values were considerably higher with a consistent downwelling and upwelling pattern on the western and eastern sides of the transect, respectively, from day 6 through day 10 (follow the arrows of Fig. 10b), during which the cyclonic Eddy-B was initiated and stagnating south of Yakushima Island before propagating to the northeast from longitude 131.0◦E (Supplementary Movie 1). On that account, we examined the simulation results of plankton (Fig. 11). As the euphotic depth z1% remained near the MLD, the \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) input might have been used by the primary producers. The \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration above the MLD in time showed an increase up to 1 µM from the initial days when Eddy-A appeared, mainly in the western region to longitude 130.9◦E, and then further enhanced in mid-month when Eddy-B and Eddy-C appeared (follow the arrows in Fig. 11a). The initial surge potentially reflected the influence of Eddy-A that was positioned and remained above the continental shelf near the island, resulting in no perceptible \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) increases in the downstream of the transect. The subsequent \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) increase ~ 1 µM propagated northeastward to downstream 131.0° E, coinciding with the detachment of Eddy-B and Eddy-C from the coastline, veered south and proceeded further downstream 131.3° E following the oblique part of the transect. Similarly to the variations in \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\), a moderate elevation in phytoplankton concentration was found, propagating downstream along the transect during eddy events, as seen in \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) (Fig. 11b). The average zooplankton concentration above the MLD increased up to 0.45 µM simultaneously with the phytoplankton increase of 0.5 µM (Fig. 11c), with a dominance of small zooplankton ( microzooplankton). The grazing rates by microzooplankton were O(0.01) mmol N m−3 day−1, showing intense and constant grazing from the initial days, particularly in the western section of the transect where the phytoplankton concentrations declined (Fig. 11d), illustrating that the rapid grazing suppressed the phytoplankton abundance. Interestingly, the nitrate concentration was relatively high in some portions where phytoplankton was absent.

Hovmoeller plots in time [days] of NO3− related parameters in the simulation. (a) FNO3 [mmol N m−2 day−1], (b) TNO3 [mmol N m−2 day−1], and (c) \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) assimilation by small phytoplankton [mmol N m−3 day−1], averaged above MLD along the magenta transect in Fig. 5a–f. Nitrate fluxes are moving-averaged 29-h to remove super-inertial fluctuations.

Hovmoeller plots in time [days] for biochemical parameters in the simulation. (a) \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration [µM], (b) phytoplankton concentration [mmol N m−3], (c) zooplankton concentration [mmol N m−3], and (d) microzooplankton grazing [mmol N m−3 day−1], averaged above MLD along the magenta transect shown in Fig. 5a–f.

Discussion

Co-working effect of diapycnal mixing and adiabatic upwelling

From the in-situ tow-yo profiling observations, FNO3 values (Eq. 4) were computed along the three transects at the subsurface layers (Supplementary Fig. S6). In November 2021, intense ε values near the convex upward structure behind the Yaku-shin-sone seamount induced a FNO3 of ∼ O(1–10) mmol N m−2 day−1, similar to the observed diffusive fluxes by Nagai et al.15, but with low values along the tilted MLD. During the transect surveys in December 2022 and January 2023, the FNO3 were mainly intense ∼ O (1–10) mmol N m−2 day−1 along the entire transect, generated by strong turbulence from the Kuroshio-topography interaction above the seamounts. Although diabatic turbulent mixing and submesoscale adiabatic upwelling do not necessarily coexist, our observations showed elevated \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration within the mixed layer above the \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) upliftings associated with submesoscale cyclonic eddies. This implies that strong turbulence can mix the upwelled nitrate by submesoscale eddies, promoting further nutrient supply in the upstream Kuroshio region. The numerical simulations showed a consistent picture that intense diffusive flux of nitrate FNO3 of ∼ O(1–10) mmol N m−2 day−1 appears above the uplifted pycnocline and nutricline above the cyclonic eddies (Fig. 7g–i), suggesting that this co-working is indeed the case.

Submesoscale cyclonic eddy generation and implications for seasonality

In our simulation, the spatiotemporal evolution in HSP (Eq. 10) and BF (Eq. 11) suggested that barotropic shear instability occurred in the first days of the model November as the flow of the Kuroshio was constrained by the coast of the island. This resulted in the formation of pronounced horizontal shear with the change in relative vorticity sign across the frontal, leading to barotropic shear instability at the locations of 130.4° E and 131° E transferring mean kinetic energy to the eddy kinetic energy32,39,40 (Fig. 9a). When the meander of the Kuroshio spread south of Yakushima Island, warm waters collided with colder coastal waters, leading to pronounced buoyancy gradients across a deepened mixed layer front and generating baroclinic instabilities (BF > 0), which can support the formation of small-scale vortices41. The study region is already well known for nutrient fluxes enhanced by turbulent mixing related to flow-topography interactions that occur throughout the year. However, seasonal deepening of the mixed layer during the autumn and winter seasons could have some potential impacts on seasonality in the nutrient supply not only due to seasonal nutrient entrainment. First, a deeper mixed layer could increase the horizontal shear production of eddy kinetic energy throughout the mixed layer when the Kuroshio Current collides with the western coast of Yakushima Island. In addition, with a deep mixed layer, more available potential energy off the south coast of the island can be converted to eddy kinetic energy, leading to a greater prevalence of submesoscale surface cyclonic eddies. In other words, HSP fueled eddy energy when the Kuroshio directly collided with the island and continental slopes, while BF took over its development more pronouncedly during non-stratified seasons, allowing eddies to be maintained further downstream. Although more numerous eddies, either cyclones or anticyclones, also appear during stratified periods (Supplementary Fig. S7), their contribution to nutrient enrichment is limited due to stronger stratification. Without a deep mixed layer, the vertical transport of subsurface nutrients along sloping isopycnals is less effective, reducing their impact during summer months, as mentioned in the previous section.

Although we did not include them in the eddy analysis, cyclonic eddies coming from the islands in the southwestern region of the domain were also detected, accompanied by anticyclonic vorticity streaks originated on the opposite sides of the cyclonic vorticity generation (Supplementary Movie 1). The formation of anticyclonic and cyclonic vortices in the northeast and southwest halves of the island wakes, respectively, have already been pointed out previously in the Tokara Strait by Liu et al.42. While cyclonic vortices may enhance upwelling of nutrients through divergent flows in the lee of islands16,43, the anticyclonic ones tend to decay and break through inertial instabilities12 which presumed to be the case in our model results. The number of detected anticyclonic eddies was notably low compared to cyclonic ones during both stratified or non-stratified seasons (Supplementary Fig. S7). More importantly, unlike an isolated island in the flow, the Kuroshio flowed mostly on the southern side of Yakushima Island, not reaching the shallow region ∼ 100 m north of the island, that may explain why only cyclonic eddies were detected in the region south of Yakushima Island. Despite this, the average PV (Eq. 8) near the eddies showed negative values on their northwestern side at the surface layer (Fig. 8b), mainly associated in the first half of the model November. When the detected eddies remained connected to the region proximity to the island, large negative vertical vorticity was generated and contributed to negative PV where centrifugal (inertial) instability32,39,44 and associated turbulent mixing can be expected.

Although the lateral patterns of vertical flows near the eddies do not necessarily align with the compass, our analysis suggested that on average upwelling and downwelling occurred on the eastern and western sides of the detected cyclonic eddies, respectively. Within them, the horizontal buoyancy gradients were weakened on the eastern side from the surface to the MLD (100 m depth) with a frontolytic tendency (FP < 0). This led to divergence and upwelling, which was intensified at 100 m depth with an average TNO3 of ∼ 17 mmol N m−2 day−1. On the other hand, following the eddy rotational flows, water masses were drawn from the northwestern side to the center, while the front on the western side of the eddy underwent frontogenesis (FP > 0), leading to a sinking motion at the surface where the average TNO3 was − 1.1 mmol N m−2 day−1.

Elucidating friction induced ageostrophic secondary circulations (ASCs)

In comparison to previous studies that associate vertical motions with wind-driven frontogenesis27,45, our simulation used a monthly climatological wind from the Comprehensive Ocean—Atmosphere Data Set (COADS) and presented that surface net buoyancy flux was ten times stronger than the Ekman buoyancy fluxes, implying negligible wind-driven frontogenesis. Under this condition, geostrophic shear stress can be balanced by ageostrophic shear stress alone, which may generate friction-induced Ageostrophic Secondary Circulations (ASCs) that always act to flatten the fronts46,47. The ASCs can be induced also by large-scale deformation (confluence/diffluence) in the vicinity of high relative vorticity. Nagai et al.47 proposed a parameter that represents the relative importance between friction and large-scale deformation to induce ASCs, i.e.,

where H is the vertical scale of the front, which was assumed here as the MLD [m], Ao vertical eddy diffusivity which was the KPP vertical viscosity coefficient [m2s−1], and \(\alpha\) deformation rate obtained by computing the principal axis of strain, i.e., \(\alpha =\sqrt{\frac{1}{4}{(\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial u}{\partial y})}^{2}+{(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x})}^{2}}\). Averaging Ao and \(\alpha\) from surface to 150 m depth, where the maximum velocity was found, \(\alpha {H}^{2}/{A}_{o}\) was ∼ 10, implying that friction-induced ASCs may not be negligible compared to that caused by deformation. As the deformation-induced upwelling ASCs were dominantly controlled by the frontolysis on the eastern flank of the cyclonic eddies, the friction-induced ASCs could only act against to the deformation (frontolysis)-induced ASCs, which served to strengthen the front. Therefore, friction-induced ASCs, which constantly weaken the front, could have only collaborated with the adiabatic subduction on the western side of the cyclonic eddies under the frontogenesis. At the surface, more realistic wind conditions need to be examined to investigate further effects from wind-driven frontogenesis, although moderately strong northerly wind during the observations may have been blocked by Yakushima and Tanegashima Islands. However, this blocking effect by Yakushima Island, the second highest mountain in western Japan, could have substantial influences on the generation of wind curl, leading to up- and downwelling at the base of the Ekman layer. This topic is beyond the scope of this paper and left for future study. On the other hand, at the bottom, an upwelling over a shallow depth might have occurred through the "tea-cup" mechanisms16,48. By averaging Ao at the bottom boundary layer and \(\alpha\) above 100 m depth of the bottom, \(\alpha {H}^{2}/{A}_{o}\) was > 100, suggesting that an upwelling through this mechanism should be overwhelmed by the deformation near the Yakushima Island.

Where the upwelled \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) comes from?

Although our simulation showed upwelled nitrate associated with the generated cyclonic eddies, the origins of the nutrients remained unclear. As the cyclonic eddies were generated near an island, waters from the shallow continental shelf may have been entrained into the eddies in addition to the subsurface Kuroshio nutrient-rich waters. To find the origins, we tracked Lagrangian particles from November 13th back in time to the beginning of November (Supplementary Movie 2). Particles that originated from the northwestern part of the domain reached the southwestern coast of Yakushima Island during mid-November. They remained within warm waters above 25 °C before being entrapped by the rotating flows of cyclonic eddies generated off the southern coast of the island. In the vertical section, within latitudes 29.6°–30.3° N, the particles originated from depths above 200 m, way below the MLD, but, upon reaching longitude 130.5° E, they exhibited vertical movements, initially descending before ascending again around longitude 131° E, consistent with the down- and upwelling induced by the eddies (Fig. 7). Finally, they congregated at the starting positions of the tracking. These results implied that a large fraction of the nitrate upwelled within the eddies originated from the subsurface Kuroshio nutrient stream, not from coastal waters.

On the other hand, nitrogen nutrients can be supplied through other processes such as regeneration, nitrification, and N2 fixations. However, nutrients in the subsurface layer ∼ 100 m depth in this region typically show the dominance of nitrate in its concentration compared to other nitrogen nutrients through regeneration or fixation processes, such as ammonium and nitrite. This was the case for water samples taken from the subsurface layers in the present study that can be upwelled by submesoscale eddies.

Complex trophic interactions

In nutrient-depleted oligotrophic environments, primary producers respond quickly to the upwelled nutrients, resulting in rapid biomass growth within hours to days30. In the simulations, the nitrate input by a cyclonic eddy was estimated to be ∼ 17 mmol N m−2 day−1, that can account for an increase rate of Chl a concentration in upper 30 m of ∼ 1.33 mg m−3 day−1 with a chlorophyll/carbon ratio of 30/149 and carbon/nitrogen Redfield ratio 106/16. From Fig. 11a, an upwelling event prevailed over 5 days, then 6.63 mg m−3 of Chl a was expected to increase. However, if we compared this with Chl a from the observations, the elevation of Chl a from its background value was only 0.1–0.2 mg m−3 in November 2021 cruise, and just 0.5 mg m−3 for the other two transects, much less than the estimation. This could be attributed to the response time of phytoplankton to grow after a nitrate injection event. In other words, observed Chl a was lower than expected since phytoplankton have not fully responded to the nitrate input. However, the results of the ecosystem model illustrate rather complex interplays among nitrate, phytoplankton and zooplankton.

In our simulation, small phytoplankton (flagellates) was predominant in the domain above the MLD accounting 74%, consistent with the in-situ experiments in the Tokara Strait that showed a large contribution from pico- and nano-phytoplankton to standing stocks and production50. Meanwhile, small zooplankton (microzooplankton) was dominant in the model accounting nearly 90% of the total model zooplankton. Previous studies suggested that grazing impact of these microzooplankton often dominates the phytoplankton production51 as the major consumer in tropical and subtropical oligotrophic waters52. Although, establishing a direct correlation between \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) and phytoplankton is difficult due to the time lag in nitrate uptake and the rapid grazing of phytoplankton by zooplankton20, a tendency of a slight positive correlation between \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) and small phytoplankton was seen at the onset of Eddy-B event (Fig. 12a) and right after the beginning of the Eddy-C event. After the events started, this correlation turned negative. The influence of zooplankton grazing became apparent as negative correlations emerged between phytoplankton and zooplankton right after the eddy events started (Fig. 12b), along with a positive tendency for the correlation between \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) and zooplankton (Fig. 12c). This suggests that the observed Chl a concentrations, which were lower than expected based on the nitrate input, were not solely due to the delayed response of phytoplankton growth but also to grazing pressure by zooplankton. These temporal changes in the correlation between \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) and phytoplankton can be considered to be consistent with the observed correlation between \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) and Chl a that was found positive during November 2021 and December 2022 within the eddies near their generation site, south of Yakushima Island (Supplementary Fig. S1a,b) and found negative during January 2023 in the downstream, off the east coast of Tanegashima Island away from the eddy generation site (Supplementary Fig. S1c).

To investigate the importance of the microzooplankton grazing on the phytoplankton concentration, another simulation without zooplankton was run and it demonstrated that phytoplankton concentration was nearly doubled in abundance (Supplementary Fig. S8), consistent with the discrepancy between the observed Chl a increase and the expected increase based on the nitrate supply. This indicates that we managed to observe only a fraction of phytoplankton increase in response to the nitrate supply due largely to zooplankton grazing. Although the biochemical model employed a Holling Type II functional response for calculating the grazing rates53, a Type III response could be more appropriate as active zooplankton feeders may exhibit a potential transition to the nonlinear Type III dependency between grazing and low phytoplankton concentration54,55,56. Thus, the Type III response was also evaluated, but keeping the same phytoplankton concentration modulated with Holling Type II. The results exhibited similar peaks during the initial days and mid-month but quantitatively less than Type II by a factor of three, suggesting that regardless of the choice of the grazing response, rapid grazing by microzooplankton on small phytoplankton should be one of the major players in formulating trophic transfers in an oligotrophic environment, consistent with the onboard incubation experiments by Kobari et al.20. By comparing primary production based on nitrate by small phytoplankton (Fig. 10c) against the rate of microzooplankton grazing (Fig. 11d, Holling type II), the primary production was higher than the grazing rate by a factor of 2, suggesting that even under the pressure of rapid grazing, phytoplankton growth was supported near the cyclonic eddies off the southern coast of Yakushima Island. Thus, this rapid trophic transfer may sustain good nursery environments for pelagic fish, improving their recruitment.

Impact of eddy induced upwelling and its implications

Our simulations showed that a total of 6 submesoscale cyclonic eddies were generated in a month south of Yakushima Island. The high-resolution satellite SST obtained in December 2024 shows a strikingly consistent image with this eddy shading frequency with at least 7 cyclonic eddies every 30–50 km along the Kuroshio over 220 km (Fig. 13). Considering a propagation speed at 0.1 ms−1, 6 eddies generated per month should have a distance of 50 km between 2 eddies, which is consistent with the eddy shading frequency seen in the simulation. The image also illustrates how these submesoscale cyclonic eddies are continuously generated and advected, forming a chain of cyclones that could enhance the biological production in the downstream region. With a net upwelling nitrate flux of ∼ 17 mmol N m−2 day−1, a duration of ∼ 5 days, and a typical radius of an eddy of 15 km, the nitrate input is estimated as 60 × 106 mol N or 60 Mmol N per eddy. Net primary production (NPP) from 2021 through 2022 during non-stratified season (Nov–Feb) using the Carbon, Absorption, and Fluorescence Euphotic- resolving (CAFE) model57 showed elevated NPP values within the region from south of Kyushu to 400 km downstream (Supplementary Fig. S9) between the Kuroshio and the coast. The integrated NPP over this area, except the coastal region within 60 km from the coast to avoid effects from coastal processes, can be ∼ 16 Gmol N during non-stratified season. Over the same period, the contributions of the cyclonic eddies can be 1.4 Gmol N, accounting ∼ 9% of the total production of the area 400 km downstream in the southwestern coast of Japan. Although our numerical simulations of 700 m lateral resolution was not conducted sufficiently long with a wide spatial coverage to obtain overall eddy effects on primary production in the downstream region of the Tokara Strait, nearly 10% contributions, derived by our rough estimation, would suggest that the eddies generated near Yakushima Island might be the major drivers for nitrate supply. However, it should be noted that since NPP estimations are based on phytoplankton carbon biomass, there is a probability of underestimation as phytoplankton can be rapidly consumed by zooplankton in this oligotrophic environment.

There are similar regions of the ocean where flow-topographic interactions could generate the submesoscale cyclonic eddies, such as the East China Sea, where topographically induced submesoscale eddies are prominent58, as well as in other regions where western boundary currents interact with complex topography, intensifying submesoscale flows, including the Brazil Current33,40, the East Australian Current31, the Gulf Stream39, or regions downstream of the Kuroshio Current path59. Since submesoscale cyclonic eddies in these studies were found to induce vertical velocities of O(100) m day−1, similar to our simulation, they probably supply nitrate at similar rates as shown here in the upstream Kuroshio. In similar oligotrophic waters, eddy-induced nitrate upwelling could induce complex trophic interactions, as illustrated in the upstream Kuroshio region by the present study. This nitrate upwelling includes the enhancement of primary and secondary producers, which can ultimately lead to elevated particulate organic carbon (POC) fluxes. Such elevated POC fluxes have been observed at the edges of mesoscale eddies in the Kuroshio region60. As submesoscale eddies and flows could have more pronounced vertical flows at the periphery of these mesoscale eddies, they might be playing a critical role in carbon export and atmospheric carbon sequestration61.

In addition to cyclonic eddies, mesoscale anticyclonic eddies have been found to play a role in nitrate supply in the Agulhas Current62, inducing an upwelling of O(10) m day−1 and signatures of submesoscale instabilities on the anticyclonic side of the Agulhas Current. In our simulation, although anticyclonic vorticity is generated on the one side of the islands, it cannot form anticyclonic eddies. This implies that submesoscale centrifugal instability prevents formation of small anticyclones while generating overturning to promote nitrate injection. Although cyclonic eddies dominated in the surface layers near Yakushima Island, submesoscale anticyclonic vortices are prominent in the subsurface layers near seamounts of Tokara Strait63. Further studies are necessary to unravel roles of these topographically induced surface and subsurface submesoscale eddies.

Methods

In-situ observations

The first part of the study consists of in-situ observations taken onboard the Training Vessel Kagoshima-maru (Faculty of Fisheries, Kagoshima University) from November 19th to 21st of 2021, and the Research Vessel Shinsei-maru (Japan Agency for Marine Earth Science and Technology, JAMSTEC) from December 30th of 2022 to January 1st of 2023. Data collected in both research cruises were from the Tokara Strait region, off the southeastern coast of the Yakushima and Tanegashima Islands, within the region between 29.5°–31° N and 130°–131.5° E (Fig. 1a). During these observations, a state-of-the-art twin tow-yo high-resolution profiling system was deployed, which consists of the Underway Vertical Microstructure Profiler (UVMP) and the SUNADAYODA system, which carries multiple sensors described below. We alternatively obtained 47 profiles from each profiler from the 2021 cruise, covering a distance of 110 km. In the December 2022 transect, 65 profiles for UVMP and 38 profiles for SUNADAYODA were obtained, covering a distance of ∼ 70 km, while the January 2023 transect covered ∼ 60 km with 19 profiles for SUNADAYODA and 83 km with 24 profiles for UVMP.

The UVMP is a free-fall tow-yo vertical microstructure profiler that consists of an Underway CTD winch (Teledyne Oceanscience, USA) and a Vertical Microstructure Profiler 250 (VMP250, Rockland Scientific International, Victoria, BC, Canada). The VMP250 carries two airfoil shear probes, two microscale thermistor sensors (FP07), an accelerometer, and a CTD (JFE-Advantech, Tokyo, Japan). The airfoil shear probes measure gradients of turbulent velocities, and the high-resolution thermistor sensors measure microscale temperature gradient, both at the frequency of 512 Hz. The accelerometer is used to detect and remove unwanted noises from instrument vibrations at low frequencies that can contaminate the shear signals. On the other hand, the biochemical profiler SUNADAYODA consists of a CTD, a chlorophyll-turbidity sensor, a RINKO dissolved oxygen sensor (JFE-Advantech, Tokyo, Japan), a deep-SUNA nitrate sensor (SBE, USA), and, similar to the UVMP, it is tow-yoed using another Underway CTD winch. Both profilers were deployed repeatedly and alternatively for five to seven minutes down to 200–300 m depth, providing vertical sections at 1–2 km horizontal resolutions. In addition, CTD casts were conducted to measure salinity, concentration of nutrients (nitrite, nitrate, ammonium, phosphorus, and silica) and chlorophyll-a. Simultaneously, UVMP and SUNADAYODA sensors were mounted on the CTD frame to calibrate the acquired measurements. The nitrate concentrations were measured at the laboratory using AutoAnalyzer (QuAAtro 2-HR, BLTech) for the cross calibration of \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) from deep SUNA mounted on the SUNADAYODA (Supplementary Fig. S10a,b). Chlorophyll a concentrations were measured from the CTD attached fluorometer for the cross calibration of chlorophyll a measured by YODA profiler (JFE-Advantech, Supplementary Fig. S10c,d). These CTD fluorometer readings had been validated using in-situ water samples analyzed with Turner fluorometers (Trilogy for the November 2021 cruise and 10-AU for the December 2022 cruise).

Satellite observations and reanalysis data

Satellite dataset were used to acquire a broader understanding of the ocean structures during the research cruise periods. Sea surface temperature (SST) and chlorophyll-a concentrations were from daily dataset of the Global Change Observation Mission-Climate ‘Shikisai’ (GCOM-C, https://global.jaxa.jp/) at a resolution of 250 m. We selected satellite images during the research cruise periods with minimal cloud cover within the study area. Additionally, Sea Surface Height (SSH) dataset were obtained from the daily dataset of the Global Ocean Physics Analysis and Forecast Copernicus Marine Service CMEMS GLORYS12V1 (http://marine.copernicus.eu/) at a spatial resolution of 0.083 × 0.083 degree, and geostrophic velocity derived from SSALTO/DUACS Sea Surface Height L4 product and derived variables by AVISO at spatial resolution of 0.25 degree (https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/en/home.html).

Numerical simulation

To conduct a high-resolution numerical simulation of the Kuroshio in the region the south of Japan, the Regional Oceanic Modeling System (ROMS) was used. The ROMS can solve incompressible hydrostatic primitive equations under Boussinesq approximation with a s-coordinate vertical grid and a horizontal curvilinear grid64. At the surface, the model was forced with monthly climatological wind, heat and freshwater fluxes from the Comprehensive Ocean—Atmosphere Data Set (COADS)65. For the lateral boundary conditions, Levitus climatology was employed. The model vertical diffusion was parameterized with the K-Profile Parameterization (KPP)66, while the Smagorinsky scheme was employed for the lateral diffusion. We used a three level horizontal nesting, the parent grid with the coarsest resolution at 5–8 km, and two successive nested grids of 1.5 km resolution, which covered the south of Japan within the range of 28–32° N 128°–134° E, and of 700 m resolution, which covered essentially off the southern coast of Yakushima Island, 29°–30.5° N 129.5°–132° E (Fig. 1b).

The ROMS simulation was coupled with a nitrogen-based N2P2Z2D2 ecosystem model53, an evolution of the ROMS NPZD model67. Since our use of biogeochemical model did not explicitly integrate an equation for chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-a concentration (in µg L−1) was calculated from phytoplankton concentration (in mmol N m−3), for both small and large phytoplankton, by using a chlorophyll-nitrogen ratio as follows:

where [Chl a] is chlorophyll-a concentration, Chl a/Carbon is a Chlorophyll-Carbon ratio, Carbon/Nitrogen is the Redfield ratio 106/16, [Phyto] phytoplankton concentration (mmol N m−3), and 12 g mol−1 is a mass of 1 mol of carbon. The Chl a/Carbon for small and large phytoplankton were taken from Hung et al.49. The simulations were first conducted only for the parent grid for 8 years and 8 months. Then, the initial conditions of the nested grids were taken from the last output of the model (August, Year 9) to conduct nested simulations until December, Year 9. Finally, the results for model Month 11 (November), Year 9 were analyzed. The validation of the ROMS output was performed using the statistical tool of Taylor diagram to show the standard deviation, root mean square error and correlation between daily satellitle observational data and model output for the parameters of SST, SSH, and Chl a. Use of daily satellite data allowed us to compare the model against the observations for submesoscale variabilities at surface layer. Also, vertical sections of \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) and density measured by Japan Meteorological Agency along TK-Line a few times in several years from 1993 through 2023 were compared with the daily ROMS output using Taylor diagram. More details in the Supplementary Figs. S2–S5.

Analysis

In-situ microscale turbulence

The turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate, ε (W kg−1), which is proportional to the turbulence strength, was measured directly using two airfoil shear probes mounted on the VMP250 of the UVMP. After the deployment, the profiler sinks quasi-freefall with speeds at 0.3–0.8 ms−1, while it acquires time series of turbulent velocity gradients, or shear. The shear spectra in wavenumber space are then computed using the shear data. The ε is determined by integrating the shear spectra to quantify the turbulent shear variance, assuming isotropic turbulence,

where ut and vt are the lateral turbulent velocities, normal to each other and to the profiling direction, z the vertical coordinate, and \(\nu\) kinematic viscosity (m2s−1). Before the integration, the shear spectra are corrected for attenuated high wavenumber signals using the response function by Macoun and Lueck68.

In-situ nitrate diffusive flux

The nitrate concentration \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) (µM) from SUNADAYODA profiler was averaged vertically every 3 m to reduce the level of noise. Then, averaged values from the sensor were calibrated with values from the water samples collected in the CTD casts (Supplementary Fig. S10a,c). Lastly, the vertical nitrate gradient \(\frac{\partial {\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}}{\partial \text{z}}\) was obtained for the nitrate diffusive flux,

where Kρ eddy diffusivity (m2 s−1) calculated as,

where Γ is assumed to be 0.269, and \({N}^{2}=-\frac{g}{{\rho }_{o}}\frac{d\rho }{dz}\) buoyancy frequency square with ρ background seawater density, ρo its reference value, and g gravitational acceleration.

Detecting submesoscale eddies

To fill the gap in spatiotemporal coverages in the observations, high-resolution simulation results were analyzed with a special emphasis on submesoscale processes. We aimed to quantify the net upwelling produced by submesoscale eddy activities. Thus, we extracted the eddy induced submesoscale processes in the regions of eddy generation and propagation at the south of Yakushima Island in the month of November in the simulation.

First, we identified the model submesoscale eddies in the interaction region of the Kuroshio and Yakushima Island within the range 29.8°–30.6° N and 130°–131.6° E (Kuroshio-Yakushima interaction region). The eddy detection method was based on closed contours of spatially high-pass filtered sea surface height (SSH) at a value of ± 0.04 m. The high-pass SSH was obtained by subtracting the moving averaged SSH at ∼ 25 km from the instantaneous SSH. The relative vorticity, \(\zeta =\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}-\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}\) (u zonal and v meridional velocities; x and y for respective coordinates) within each eddy was averaged to determine whether the eddy is cyclonic with positive or anticyclonic with negative values of \(\zeta\) in the Northern Hemisphere (see the evolution of the structures in Supplementary Movie 1). To avoid too small or too large closed contours to be detected as submesoscale eddies, we used the criteria for the minimum (5 km) and maximum (20 km) radius of eddies.

Associated submesoscale processes within detected eddies

Once all the eddies within the interaction region were identified, frontogenetic parameter (FP), Ertel’s potential vorticity (PV), and nitrate vertical flux (TNO3) within the detected eddies in the Kuroshio-Yakushima interaction region were extracted from the hourly model output. Monthly averaged values for these parameters were then calculated as a function of distance from the center of the eddies to quantify the effects on the nutrient inputs at two different depths, 10 m (surface and above mixed layer depth: MLD), and 100 m (base of the MLD) in the study region.

The frontogenetic parameter (FP) was computed to determine whether the deforming motions in the periphery of the cyclonic eddies can strengthen the horizontal density gradients, frontogenesis, or weaken them, frontolysis38,41,

where \(b=-g\rho /{\rho }_{o}\) is buoyancy, the \(\text{Q}=-(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}\frac{\partial b}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\frac{\partial b}{\partial y},\frac{\partial u}{\partial y}\frac{\partial b}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\frac{\partial b}{\partial y})\) is the Q-vector, \(\text{Q }\cdot {\nabla }_{h}b\) product of velocity and buoyancy gradients that represents the rate at which horizontal velocity goes across the density surfaces, and \({\nabla }_{h}=\frac{\partial }{\partial x}+\frac{\partial }{\partial y}\) a horizontal gradient operator. To determine the model frontal sharpness, we computed the magnitude of the horizontal buoyancy gradient \(\left|{\nabla }_{h}b\right|\),

Moreover, submesoscale instabilities can be triggered when the Ertel’s Potential Vorticity (PV) changes its sign from the background values32,44,70 to negative sign in the Northern Hemisphere. Since sloping bottom boundaries near islands and seamounts can generate negative PV and may induce inertial-symmetric instability, PV was also computed in the simulation, ignoring small vertical velocity, i.e.,

where f is the Coriolis parameter.

Lastly, the advective nitrate vertical flux TNO3 was also computed to quantify the eddy-induced nitrate upwelling within and near the cyclonic eddies,

where, w is the vertical velocity (m s−1) and \({\text{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) nitrate concentration (µM).

Analysis on the eddy generation

We computed energy source terms to identify the nature of the instability processes responsible for the eddy generation.

Therefore, we followed previous analysis made by Gula et al.32, Calil et al.40, and Luko et al.33, and used the equations of horizontal shear production (HSP) and vertical buoyancy flux (BF). When the former and the latter dominate, the responsible mechanisms for eddy generation can be considered as barotropic or baroclinic instabilities, respectively.

The overbars indicate time average for a month of model November, and the primes denote deviations from the averages.

The conversion from mean to eddy kinetic energy (MKE → EKE) indicates that the pathway occurs through horizontal shear instabilities (HSP > 0), while the conversion from eddy potential to eddy kinetic energy (EPE → EKE) is associated with baroclinic instabilities (BF > 0). However, the presence of Hirase and Yaku-shin-sone seamounts in the vicinity may influence the BF values, as the vertical velocity w near these seamounts could be generated by local processes, such as lee waves. Therefore, we discarded the data when the inverse coefficient of variation of BF, the ratio of mean BF to its standard deviation, exceeded 0.45, assuming that stationary lee waves increase mean BF and its inverse coefficient of variation. This could eliminate the stationary bands of BF behind the seamount at certain degrees. Values of HSP and BF were computed every six hours and separated in three groups for every ten days in the model November at the depth of 100 m in the Kuroshio-Yakushima interaction region.

Lagrangian particle simulation to track nitrate back in time

We employed a backward Lagrangian particle tracking to determine the origin of the upwelled/downwelled nitrate at the cyclonic eddies generated south of Yakushima Island. The particle initial locations and numbers per grid cell were set proportional to the nitrate concentrations of the releasing time, November 13th, which then were tracked back in time until November 1st. The total number of released particles was 20,000, but the hourly output data for only 700 particles placed within the cyclonic eddy at the initial step were analyzed. For the particle tracking, the vertical diffusion was not considered. As the releasing depth range was set as 120–200 m below the mixed layer, the neglecting the vertical diffusion can be justified (see the particle tracking animation in Supplementary Movie 2).

Data availability

The processed data from the cruises, and codes for analyzing are available from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11093255. The ROMS code is available from https://www.myroms.org/ Codes for Taylor diagrams are available from: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15504052 . Bathymetry data used in Fig. 1 from ETOPO Global Relief Model, available from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/etopo-global-relief-model. And, the shorelines used for figures with Japanese coastline (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 13, Supplementary Figs. S2, S3, S9) were extracted from Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database (GSHHG) from https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/, coastline file has been added as japan.mat in https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15504052. Satellite data used for the SST and SSH snapshot comparison in Supplementary Fig. S2. Sea surface temperature (SST): daily dataset of the Global Change Observation Mission-Climate ‘Shikisai’ GCOM-C at a resolution of 250 m available from https://global.jaxa.jp/, and sea surface height (SSH) daily dataset of the Global Ocean Physics Analysis from Copernicus Marine Service GLORYS12V1 at a spatial resolution of 0.083 × 0.083 degree available from https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_ANALYSISFORECAST_PHY_001_024/description. Satellite data used for the climatology surface chlorophyll comparison in Supplementary Fig. S3 : seasonal climatology from Aqua-MODIS level 3 at a resolution of 4 km from Ocean Biology Processing Group NASA available from https://oceandata.sci.gsfc.nasa.gov/directdataaccess/. Satellite daily data used for the Taylor diagrams in Supplementary Fig. S4 : for SST, Global Ocean OSTIA Sea Surface Temperature and Sea Ice Reprocessed Level 4 at 0.05º spatial resolution from https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SST_GLO_SST_L4_REP_OBSERVATIONS_010_011/description;. for SSH, it was used the summation of mean dynamic topography from Global Ocean Mean Dynamic Topography Level 4 at 0.125º resolution https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_MDT_008_063/description, and sea surface height above sea level from Global Ocean Gridded L 4 Sea Surface Heights And Derived Variables Reprocessed Copernicus Climate Service Level 4 at 0.25º resolution https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_CLIMATE_L4_MY_008_057/description;. for chlorophyll, Global Ocean Colour (Copernicus-GlobColour), Bio-Geo-Chemical, L4 (monthly and interpolated) from Satellite Observations (1997-ongoing) Level 4 at 4 km resolution from https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/OCEANCOLOUR_GLO_BGC_L4_MY_009_104/description. Observational data from TK line, 28.5–30.3º N 129.75–131.0º E, from Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) for vertical sections validation in Supplementary Fig. S5 from https://www.data.jma.go.jp/kaiyou/db/vessel_obs/data-report/html/ship/ship.php. Animation for hourly output at the surface from the simulation (Supplementary Movie 1) is available on https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25522816.v1. Animation for tracked Lagrangian particles in the domain of the finest grid of the simulation (Supplementary Movie 2) is available on https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25522840.v1.

References

Kawabe, M. Variations of current path, velocity, and volume transport of the Kuroshio in relation with the large meander. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 25, 3103–3117 (1995).

Komatsu, K. & Hiroe, Y. Structure and Impact of the Kuroshio Nutrient Stream, In Kuroshio Current: Physical, biogeochemical, and ecosystem dynamics, T. Nagai, H. Saito, K. Suzuki, M. Takahashi (Eds.) (AGU-Wiley, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119428428.ch5.

Okazaki, Y. et al. Diverse trophic pathways from zooplankton to larval and juvenile fishes in the Kuroshio ecosystem. Kuroshio Curr. Phys. Biogeochem. Ecosyst. Dyn. 245–256 (2019).

Saito, H. The Kuroshio: Its recognition, scientific activities and emerging issues, In Kuroshio Current: Physical, biogeochemical, and ecosystem dynamics, T. Nagai, H. Saito, K. Suzuki, M. Takahashi (Eds.) (AGU-Wiley, 2019).

Durán Gómez, G. S., Nagai, T. & Yokawa, K. Mesoscale warm-core eddies drive interannual modulations of swordfish catch in the Kuroshio Extension System. Front. Mar. Sci. (2020).

Takahashi, T. et al. Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea–air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep. Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 554–577, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.12.009 (2009).

Guo, X., Zhu, X.-H., Wu, Q.-S. & Huang, D. The Kuroshio nutrient stream and its temporal variation in the East China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 117 (2012).

Guo, X., Zhu, X.-H., Long, Y. & Huang, D. Spatial variations in the Kuroshio nutrient transport from the East China Sea to south of Japan. Biogeosciences 10, 6403–6417 (2013).

Williams, R. G. et al. Nutrient streams in the North Atlantic: Advective pathways of inorganic and dissolved organic nutrients. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 25 (2011).

Browning, T. J. & Moore, C. M. Global analysis of ocean phytoplankton nutrient limitation reveals high prevalence of co-limitation. Nat. Commun. 5014. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40774-0 (2023).

Sarmiento, J. L. Ocean biogeochemical dynamics. In Ocean Biogeochemical Dynamics (Princeton University Press, 2013).

Chang, M.-H., Tang, T. Y., Ho, C.-R. & Chao, S.-Y. Kuroshio-induced wake in the lee of Green Island off Taiwan. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 118, 1508–1519 (2013).

Nagai, T. et al. First evidence of coherent bands of strong turbulent layers associated with high-wavenumber internal-wave shear in the upstream Kuroshio. Sci. Rep. 7, 14555 (2017).

Tsutsumi, E. et al. Turbulent mixing within the Kuroshio in the Tokara Strait. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 122, 7082–7094 (2017).

Nagai, T. et al. How the Kuroshio Current delivers nutrients to sunlit layers on the continental shelves with aid of near-inertial waves and turbulence. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6726–6735 (2019).

Hasegawa, D., Yamazaki, H., Lueck, R. & Seuront, L. How islands stir and fertilize the upper ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31 (2004).

Nagai, T., Rosales Quintana, G. M., Durán Gómez, G. S., Hashihama, F. & Komatsu, K. Elevated turbulent and double-diffusive nutrient flux in the Kuroshio over the Izu Ridge and in the Kuroshio Extension. J. Oceanogr. 1–20 (2021).

Nagai, T. et al. The Kuroshio flowing over seamounts and associated submesoscale flows drive 100-km-wide 100–1000-fold enhancement of turbulence. Commun. Earth Environ. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00230-7 (2021).

Hasegawa, D. Island mass effect. Kuroshio Curr. Phys. Biogeochem. Ecosyst. Dyn. In Kuroshio Curr. Phys. biogeochemical, ecosystem dynamics, T. Nagai, H. Saito, K. Suzuki, M. Takahashi (Eds.) 163–174 (2019).

Kobari, T. et al. Phytoplankton growth and consumption by microzooplankton stimulated by turbulent nitrate flux suggest rapid trophic transfer in the oligotrophic Kuroshio. Biogeosciences 17, 2441–2452 (2020).

Durán Gómez, G. S. & Nagai, T. Elevated nutrient supply caused by the approaching Kuroshio to the southern coast of Japan. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 842155 (2022).

Kaneko, H., Yasuda, I., Komatsu, K. & Itoh, S. Observations of the structure of turbulent mixing across the Kuroshio. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39 (2012).

Kaneko, H., Yasuda, I., Komatsu, K. & Itoh, S. Observations of vertical turbulent nitrate flux across the Kuroshio. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 3123–3127 (2013).

Lazaneo, C. Z. et al. On the role of turbulent mixing produced by vertical shear between the Brazil Current and the Intermediate Western Boundary Current. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 125, e2019JC015338 (2020).