Abstract

The triglyceride‒glucose (TyG) index is associated with the development and prognosis of cardiovascular disease. The relationship between it and subclinical right ventricular (RV) systolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate this relationship in T2DM patients. A total of 170 T2DM patients were enrolled. The TyG index was calculated and then stratified into tertiles: the T1 group (TyG index ≤ 9.1495, n = 52), the T2 group (9.1495 < TyG index ≤ 9.7611, n = 54), and the T3 group (TyG index > 9.7611, n = 52). RV systolic function was evaluated in terms of RV free-wall longitudinal strain (RV FWLS). One-way analysis of variance revealed significant differences in the RV FWLS among the three groups. As the TyG index increased, the severity of RV systolic dysfunction increased. After adjusting for age and sex, the multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that a higher TyG index was significantly associated with a RV FWLS < 20%, which was maintained after adjusting for body mass index (BMI), systolic pressure (SBP), left ventricular global longitudinal systolic strain (LV GLS), hypertension, and dyslipidemia. In T2DM patients, a higher TyG index was significantly associated with subclinical RV systolic dysfunction independent of other cardiovascular risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic cardiomyopathy, which was first confirmed by Rubler et al.1 generally manifests as pathological cardiac remodeling and systolic and diastolic dysfunction. However, changes in myocardial function in the early stage of diabetic cardiomyopathy are usually ignored and underestimated. Cardiovascular complications are the main cause of death in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients. Therefore, early identification followed by timely intervention is vital for individuals with T2DM at high risk of cardiovascular complications.

Diabetic cardiomyopathy is the result of the interaction of many factors. Studies have demonstrated that insulin resistance (IR) and/or hyperinsulinemia are also involved in the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy2,3. IR is defined as reduced efficiency of insulin in promoting the uptake and utilization of glucose in the body. It causes an imbalance in glucose and lipid metabolism, which leads to metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, and is also recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). In the past, the glucose clamp technique and the insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) were the two main methods used to evaluate IR. However, these two methods are difficult to apply on a large scale in clinical practice because of high costs and complicated calculations4. The triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index is a novel biological parameter used for identifying insulin resistance, easy to calculate, and proven more beneficial for evaluating IR than HOMA-IR5. Several studies have demonstrated that the TyG index is closely related to CVD6,7. Chen Y et al. confirmed that in T2DM patients, a higher TyG index was significantly associated with subclinical LV systolic dysfunction, which was assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking technology (2D-STE), a new method for the early evaluation of subclinical myocardial dysfunction8.

However, it remains unclear whether the TyG index and subclinical RV systolic dysfunction are related in T2DM patients. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to determine the relationship between the TyG index and subclinical RV systolic dysfunction in T2DM patients.

Methods

Study population

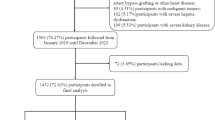

This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of Changzhou No.2 People’s Hospital. Also, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

A total of 170 consecutively hospitalized T2DM patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were included in this research. The T2DM patients were divided into three groups according to the tertile of the TyG index: the T1 group (TyG index ≤ 9.1495, n = 52), the T2 group (9.1495 < TyG index ≤ 9.7611, n = 54), and the T3 group (TyG index > 9.7611, n= 52). T2DM was diagnosed in accordance with the World Health Organization criteria, which were as follows: fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L on 2 occasions and/or 2-hour plasma glucose value during a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test ≥ 11.1 mmol/L9. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) type 1 diabetes mellitus; (2) LVEF < 50%; (3) coronary artery disease (coronary artery stenosis diagnosed by CT examination ≥ 50%); (4) atrial fibrillation (including paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and persistent atrial fibrillation); (5) congenital heart disease; (6) cardiomyopathy; (7) valvular heart disease (mild and above); (8) pulmonary embolism, (9) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and (10) cerebrovascular disease (Fig. 1).

Clinical variables and biochemical measurements

Demographic data, including age, sex, height, weight and blood pressure (systolic blood pressure: SBP, diastolic blood pressure: DBP), were obtained from all T2DM patients. Body mass index (BMI) was defined as weight/height2 (kg/m2). After at least 12 h of overnight fasting, the levels of fasting plasma glucose (FPG), glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were measured with an automatic biochemical analyzer. The TyG index was subsequently calculated as follows: Ln (fasting TG [mg/dL] × fasting glucose [mg/dL]/2), as previously described10.

Conventional echocardiography examination and two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography analysis

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed by an experienced cardiologist using a E9 ultrasound system (GE Healthcare, USA) by an experienced cardiologist. Routine echocardiography parameters of RV were measured from the apical 4-chamber view (focusing on the right ventricle). The basal diameter and middle diameter of the RV were measured during end-diastole. The RV end-diastolic area (RVA-D) and RV end-systolic area (RVA-S) were measured by manually defining the endocardial border of the RV, and the right ventricular fractional area change (RV-FAC) was calculated as the difference between the end-diastolic area and the end-systolic area divided by the end-diastolic area and expressed as a percentage. Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) was measured through M-mode with the cursor aligned along the direction of the tricuspid lateral annulus. The early (E) and late (A) transtricuspid inflow velocities were determined using pulse-wave Doppler. The peak systolic, early diastolic and late diastolic velocities of the tricuspid annulus were measured using tissue Doppler imaging (TDI S, TDI E, and TDI A). The LVEF was calculated according to the biplane Simpson’s rule. The RV FWLS was analyzed using Echo PAC PC software, version 203 (GE Healthcare, Horten, Norway). Three consecutive cardiac cycles images of apical four chamber of RV were acquired during an end-expiratory breath-hold and transferred to EchoPAC software. The endocardial border of the RV was traced manually in the end-systolic frame at the point in the cardiac cycle in which the endocardial border was the clearest. Then the software would generate a region of interest automatically, and adjusted the region of interest to make the myocardial included well. If it was not feasible to track 1 or more segments, the case was excluded. The RV free wall was automatically divided into three segments: basal, middle, and apical. RV free wall systolic longitudinal strain (RV FWLS) was calculated as the mean of the values of the three segments of the RV free wall. The predefined cutoff of RV FWLS < 20% was adopted to evaluate subclinical RV systolic dysfunction11. Left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LV GLS) was analyzed as previously described in detail12. Because RV FWLS and LV GLS were negative values, we took their absolute values for a simpler interpretation.

Repeatability test

The measurement of RV FWLS was repeated in 20 randomly selected subjects by the same physician (intraobserver variability) and another physician (interobserver variability) to analyze its intraobserver and interobserver variability.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) if normally distributed after the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test and were compared using an independent Student’s t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Least significant difference was used to compare the 2 samples when variance was homogeneous, and Dunnett T3 method was used when variance was heterogenetic, according to Levene test for homogeneity of variance. A nonparametric test was performed when the data did not have a normal distribution, and the results are expressed as medians (interquartile ranges). Categorical variables are expressed as n (%) of the sample and were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The correlations between clinical risk factors and RV FWLS were tested using Pearson correlation coefficients. Three forced-entry logistic regression models were used to determine the independent associations of RV FWLS < 20% with the TyG index: Model 1 (an unadjusted model), Model 2 (a multivariable model) adjusted for age and sex, and Model 3 (a multivariable model) adjusted for age, sex, BMI, SBP, LV GLS, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate intraobserver and interobserver variability, and an ICC ≥ 0.75 indicated good reliability. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 23.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Twelve of the 170 T2DM patients were excluded from the final analysis for meeting the exclusion criteria (3 patients with congenital heart disease, 2 patients with coronary artery disease, 3 patients with atrial fibrillation, 2 patients with valvular heart disease, and 2 patients with poor image quality).

Clinical characteristics

Table 1 shows the comparison of clinical characteristics by TyG index tertiles [T1 (TyG index ≤ 9.1495), T2 (9.1495 < TyG index ≤ 9.7611), and T3 (TyG index > 9.7611)]. Patients in the T3 group were older than those in the T1 and T2 groups and had higher incidences of hypertension and dyslipidemia, accompanied by higher levels of BMI, SBP, DBP, FPG, HbA1c TC, TG, LDL-C and lower level of HDL-C (all P < 0.05). Compared with the T1 group, the values of BMI, SBP, FPG, HbA1c TC, TG, and LDL-C in the T2 group were significantly higher (all P < 0.05). There were no differences in diabetes duration or medication treatment among the three groups (all P > 0.05).

Echocardiographic parameters

Table 2shows the comparison of echocardiographic parameters by TyG index tertiles. From the lowest to the highest tertiles of the TyG index, the RV FWLS decreased significantly (20.28, 19.29 and 18.56; P < 0.01). There were no differences in the RVd-base, RVd-mid, RVA-D, RVA-S, RV-FAC, TDI S, TDI E, TDI A, TAPSE, or LVEF (all P > 0.05) (Fig. 2).

Association of clinical risk factors with RV FWLS

Bivariate correlation analysis with Pearson’s correlation indicated that age, BMI, SBP, TC, TG, LDL-C, FPG, HbA1c, and TyG index were negatively correlated with RV FWLS (all P < 0.05), whereas LV GLS was positively correlated with RV FWLS (P < 0.05) (Table 3). According to the univariate analysis, the TyG index was significantly correlated with RV FWLS < 20% (OR 1.988, 95% CI 1.195–3.308; P = 0.008). After adjusting for age and sex, the TyG index was still related to RV FWLS < 20% (OR 1.809; 95% CI 1.072–3.053; P = 0.026), which was maintained after further adjustment for BMI, SBP, LV GLS, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (OR 1.888, 95% CI 1.005–3.545; p = 0.048) (Table 4).

Intraobserver and interobserver variability

The ICCs of the intraobserver and interobserver variabilities of the RV FWLS were 0.978 (95% CI 0.890–0.993) and 0.911 (95% CI 0.788–0.964), respectively, indicating good reliability.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to reveal that, in T2DM patients, an increased TyG index is independently associated with subclinical RV systolic dysfunction, which is evaluated by 2D-STE.

LV function has long been a subject of clinical and ultrasound studies. Most previous studies on myocardial dysfunction in patients with diabetes have focused on LV function13,14. With the deepening research on heart function, RV function has gradually entered people’s field of vision and attracts increasing attention. RV function is a critical link between systemic and pulmonary circulation. It plays an important role in the cardiac cycle and is crucial for maintaining overall cardiac function. RV dysfunction can ultimately lead to the failure of the entire heart function. Numerous studies have shown that RV function is valuable in diagnosing and predicting the prognosis of various cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases15,16. In recent years, the RV function of patients with left heart disease has also received increasing attention17,18,19. The main function of the RV is to maintain effective cardiac output. The contraction of RV mainly occurs through the shortening of longitudinal myocardial fibers. Thus, measuring RV longitudinal systolic strain by echocardiography can reflect RV systolic performance early and sensitively20. It can evaluate RV systolic dysfunction earlier than traditional parameters (e.g., TAPSE and RV-FAC), that is subclinical RV systolic dysfunction. It directly measures intrinsic RV myocardial deformation without angle dependence and is less affected by left ventricular apex motion, thus enabling more accurate early assessment of RV systolic function. Therefore, in this study, we chose to evaluate RV systolic function by analyzing RV FWLS. Insulin resistance (IR) is characterized by the reduced efficiency of insulin in promoting the uptake and utilization of glucose in the body. It can cause an imbalance in glucose and lipid metabolism, which leads to metabolic syndrome and T2DM. The TyG index is a biological parameter calculated by multiplying TG and FPG values. It is easily calculated, providing reliable measurement results, and has been proven to be an effective alternative indicator for evaluating IR21. Recent studies have shown that the TyG index is not only a reliable indicator for evaluating IR but also closely related to the development and prognosis of cardiovascular disease (CVD)22,23,24.

Several studies have suggested that a higher TyG index may be associated with subclinical LV dysfunction in T2DM patients8,25. Although previous studies have reported that RV systolic dysfunction is also present in T2DM patients with preserved LVEF26,27. Moreover, RV dysfunction and fibrosis are associated with left ventricular arrhythmias, sudden death, exercise limitation, and impaired RV cardiac output28. However, there is no study on the TyG index and subclinical RV systolic dysfunction in T2DM patients. In this study, we used 2D-STE to evaluate RV systolic function and reported that a higher TyG index is closely related to impaired RV systolic function in T2DM patients. Further multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, SBP, LV GLS, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, the TyG index was still related to RV FWLS < 20%. Thus, the TyG index was significantly associated with RV subclinical systolic dysfunction in T2DM patients, independent of generally accepted cardiovascular risk factors.

Currently, the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy has not been fully elucidated. IR causes an imbalance in glucose metabolism in the human body, leading to inflammation and oxidative stress and causing myocardial impairment. Moreover, IR induces the production of glycation products and free radicals, as well as changes in lipid metabolism, leading to dyslipidemia, as evidenced by elevated TG levels, elevated LDL-C levels, and decreased HDL-C levels. These changes in glucose and lipid metabolism may ultimately lead to myocardial injury and fibrosis.

Our research suggests that a higher TyG index can indicate subclinical RV myocardial dysfunction in T2DM patients. This information can help guide clinicians in the early identification of T2DM patients at high risk of cardiovascular complications as well as in the implementation of early interventions to prevent cardiovascular events and reduce the risks of morbidity and mortality of patients. Moreover, these findings can also guide the early evaluation of the efficacy of hypoglycemic drugs in improving insulin resistance.

Limitations

First, the sample size was relatively small, so further large-scale studies are needed to validate our findings. Second, this was a cross-sectional retrospective study, and the specific causal relationship of the TyG index with reduced RV FWLS remains unclear. Third, owing to the absence of a cutoff value for the TyG index, we could not perform receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to determine a specific TyG index value that indicates subclinical RV myocardial dysfunction.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that an increase in the TyG index is independently associated with a decrease in RV FWLS. It is a good indicator for the early detection of subclinical RV myocardial dysfunction in T2DM patients.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the author Xiang-ting Song (E-mail: wylsxt@163.com), without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

References

Rubler, S. et al. New type of cardiomyopathy associated with diabetic glomerulosclerosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 30 (6), 595–602 (1972).

Jia, G. et al. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: a hyperglycaemia- and insulin-resistance-induced heart disease. Diabetologia 61 (1), 21–28 (2018).

Jia, G. et al. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 12 (3), 144–153 (2016).

Vazquez Rocha, L. et al. The use and effectiveness of selected alternative markers for insulin sensitivity and secretion compared with gold standard markers in dietary intervention studies in individuals without diabetes: results of a systematic review. Nutrients 14 (10), 2036 (2022).

Luo, P. et al. TyG index performs better than HOMA-IR in Chinese type 2 diabetes mellitus with a BMI < 35 kg/m2: A hyperglycemic clamp validated study. Med. (Kaunas). 58 (7), 876 (2022).

Tao, L. C. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index as a marker in cardiovascular diseases: landscape and limitations. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21 (1), 68 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Positive association between triglyceride glucose index and arterial stiffness in hypertensive patients: the China H-type hypertension registry study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19 (1), 139 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Association between triglyceride glucose index and subclinical left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lipids Health Dis. 22 (1), 35 (2023).

Alberti, K. G. et al. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med. 15 (7), 539–553 (1998).

Zhao, Q. et al. Impacts of triglyceride-glucose index on prognosis of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: results from an observational cohort study in China. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19 (1), 108 (2020).

Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults. An update from the American society of echocardiography and the European association of, cardiovascular imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 17 (4), 412 (2016).

Cheung, Y. F. et al. Left ventricular myocardial deformation and mechanical dyssynchrony in children with normal ventricular shortening fraction after anthracycline therapy. Heart 96 (14), 1137–1141 (2010).

Ikonomidis, I. et al. Early detection of left ventricular dysfunction in first-degree relatives of diabetic patients by myocardial deformation imaging: the role of endothelial glycocalyx damage. Int. J. Cardiol. 233, 105–112 (2017).

Xu, H. Y. et al. Volume-time curve of cardiac magnetic resonance assessed left ventricular dysfunction in coronary artery disease patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 17 (1), 145 (2017).

Foppa, M. et al. Right ventricular volumes and systolic function by cardiac magnetic resonance and the impact of sex, age, and obesity in a longitudinally followed cohort free of pulmonary and cardiovascular disease: the Framingham heart study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 9 (3), e003810 (2016).

Arenja, N. et al. The prognostic value of right ventricular long axis strain in non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathies using standard cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur. Radiol. 27 (9), 3913–3923 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Right ventricular size and function in chronic heart failure: not to be forgotten. Heart Fai L Clin. 15 (2), 205–217 (2019).

Koifman, E. et al. Impact of right ventricular function on outcome of severe aortic stenosis patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Am. Heart J. 184, 141–147 (2017).

Mascherbauer, J. et al. Presence of ´isolated´ tricuspid regurgitation should prompt the suspicion of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. PLoS One. 12 (2), e0171542 (2017).

Pinsky, M. R. The right ventricle: interaction with the pulmonary circulation. Crit. Care. 20 (1), 266 (2016).

Ramdas Nayak, V. K. et al. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index: A surrogate biomarker of insulin resistance. J. Pak Med. Assoc. 72 (5), 986–988 (2022).

Wu, S. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose index and risk of arterial stiffness: a cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20 (1), 146 (2021).

Kim, M. K. et al. Relationship between the triglyceride glucose index and coronary artery calcification in Korean adults. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 16 (1), 108 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Association between triglyceride glucose index, coronary artery calcification and multivessel coronary disease in Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21 (1), 187 (2022).

Sun, Q. C. et al. Association of the triglyceride-glucose index with subclinical left ventricular dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A retrospective cross-sectional study. J. Diabetes Investig. 14 (8), 953–960 (2023).

Linssen, P. B. C. et al. Associations of (pre)diabetes with right ventricular and atrial structure and function: the Maastricht study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19 (1), 88 (2020).

Widya, R. L. et al. Right ventricular involvement in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Care. 36 (2), 457–462 (2013).

Warnes, C. A. Adult congenital heart disease importance of the right ventricle. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 54 (21), 1903–1910 (2009).

Funding

This study was funded by Young Talent Science and Technology Project of Changzhou (No.: QN202230).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F.B. and X.T.S. conceived and designed the study and data collection. Y.F.B. wrote the manuscript. L.F. and L.C. acquired ultrasound images of the patients. L.F. performed the statistical analysis. X.T.S. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bian, Yf., Fan, L., Cui, L. et al. Association of the triglyceride‒glucose index with subclinical right ventricular systolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Sci Rep 15, 19915 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05356-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05356-8