Abstract

Quality of Life (QoL) in urban environments represents people’s well-being and is influenced by various factors. This paper introduces an innovative approach to promote urban equity by integrating spatial analysis and Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM). The proposed method focuses mainly on accessibility to urban facilities and environmental health factors. In this research, data fusion techniques were utilized to generate criteria maps for urban air pollution and heat islands, while factor analysis, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and entropy were employed to provide a comprehensive assessment of equity related to these environmental factors in the case study area. Expert opinions, collected through the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Best–Worst Method (BWM), were refined using Dempster–Shafer theory to adjust the weights assigned to each evaluation criterion. The results highlight that access to educational facilities and green spaces significantly impacts urban equity, with respective weights of 0.189 and 0.149. Air pollution was also identified as a critical factor, with a weight of 0.152. These findings underscore the potential of this integrated approach in assessing urban livability, particularly in Tehran, Iran.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Throughout history, cities have driven scientific, economic, social, and cultural development. They offer a variety of services and amenities to improve citizens’ welfare and comfort.1,2. As a result, many people find urban living more appealing. However, modern cities are currently confronting major obstacles, including environmental degradation, traffic congestion, overpopulation, economic inequality, and various social issues3. These issues have profoundly influenced lifestyles, environmental conditions, and public health, reducing the overall Quality of Life (QoL). Nonetheless, policymakers and planners on both the international and national levels highlight cities’ ability to improve QoL4,5,6.

Despite the crucial role cities play in fostering development and providing essential services, the increasing complexity of urban challenges poses significant threats to residents’ QoL. Factors such as pollution, traffic jams, overcrowding, and socio-economic disparities have intensified in recent decades, adversely affecting public health, social cohesion, and environmental sustainability. These persistent problems complicate efforts to promote livable and equitable urban environments7,8,9,10. To better understand and respond to these challenges, it is essential to identify key evaluation criteria, particularly those related to environmental and spatial conditions, and to analyze their distribution across urban areas. In this context, Geographic Information Science (GIS) allows planners to visualize spatial disparities and access to services, providing a clearer foundation for targeted and sustainable interventions10.

Given the multifaceted and dynamic nature of these issues, assessing urban QoL requires comprehensive approaches that can capture the diversity of influencing factors. However, current evaluation methods often struggle to address this complexity effectively, limiting the ability of planners and policymakers to implement targeted and impactful interventions8. Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) techniques, including popular methods such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the Best–Worst Method (BWM), have proven effective in addressing complex urban QoL assessments by integrating diverse criteria and expert judgments.

Numerous studies have endeavored to quantify and spatially visualize urban QoL through diverse data sources and multi-criteria assessment techniques. Lo and Faber4 utilized Landsat Thematic Mapper satellite imagery alongside U.S. census data to evaluate urban QoL in Atlanta, generating detailed spatial maps. Similarly, Rinner5 generated a spatial visualization framework that uses MCDM methods such as AHP to evaluate social, economic, and environmental factors in Toronto communities. This approach allows planners to investigate weighting scenarios and identify spatial QoL trends, thereby facilitating informed policymaking. Javadi and Taleai11, proposed a mixed-method framework integrating subjective and objective criteria to measure QoL at the intra-national level, highlighting Tehran’s relatively higher QoL compared to less favorable regions such as Sistan-and-Balouchestan and Kermanshah. Beyond urban contexts, Mocuta6 examined the impacts of climate change on rural QoL, emphasizing health, agriculture, and well-being. Although focused on rural areas, the findings underscore the broader significance of policy measures applicable to urban settings, particularly regarding environmental challenges.

A substantial body of research has applied MCDM methods to evaluate QoL12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, with a predominant focus on AHP and BWM as leading weighting techniques. Dadashpoor et al.12 employed the AHP technique for data integration and used the Gini coefficient to evaluate inequality. They also examined the metrics such as neighborhood effect, accessibility, and the percentage of urban areas covered by services. Bhatti et al.13 assessed QoL using data on physical health, psychological and social connections, the environment (natural and built), economic circumstances and development, and access to facilities and services. The weighting procedure in their study was carried out using the AHP approach. Özdemir Işık and Demir,14 studied how changes in recreation and tourism affect the QoL along the Trabzon coastline in Turkey, with the objective of improving inhabitants’ well-being. They employed the AHP approach for the primary criterion and the ELECTRE method for the sub-criteria. Hussain et al.18 additionally suggested a novel MCDM framework for assessing ideological and political education strategies under uncertainty, which includes methodological innovations useful in complex, value-driven decision environments. Badi et al.19 designed a hybrid MCDM framework by combining Fuzzy Simple Weight Calculation for criteria weighting and the MARCOS method for ranking strategic logistics alternatives in Free Trade Zones, demonstrating the utility of fuzzy and MCDM techniques in infrastructure decision-making. In a similar effort to utilize robust MCDM frameworks in high-stakes environments, Moslem et al.20 evaluated accident analysis techniques in process industries using the Logarithmic Methodology of Additive Weights (LMAW) and the Double Normalization-Based Multiple Aggregation (DNMA) method, demonstrating the increasing utility of advanced ranking and weighting models in complex decision-making scenarios.

At the city scale, Dissanayake et al.16 established a life quality index (LQI) for Kandy City employing an AHP-like MCDM method. Gradient analysis indicated that socioeconomic factors, especially transportation, had a stronger influence on QoL than environmental ones. Withanage et al.17 examined spatial inequities in QoL in Polpitigma town by applying 20 geographical variables using GIS and AHP. The outcome had the highest influence of cultural variables compared to the environment, service, security, and socioeconomic variables, with only 4.5% of the area having high QoL. Ptak-Wojciechowska21 examined the urban QoL of elderly citizens with multi-criteria analysis and the AHP approach. The results confirm the applicability of AHP in urban planning and suggest that future assessments could be enhanced through the use of machine learning (ML) for greater precision.

While prior research predominantly utilized a single MCDM technique, the current study integrates AHP and BWM to enhance evaluation robustness by combining expert judgment with both qualitative and quantitative data12,13,14,22,23,24. Although methods like ELECTRE and TOPSIS are widely used, they are less appropriate for this context due to limitations such as rigid utility assumptions or a focus on ranking options. In contrast, AHP and BWM are more appropriate for assigning weights to diverse urban QoL indicators, making them particularly effective for complex assessments such as Tehran’s urban environment. AHP was employed due to its ability to capture expert judgment through pairwise comparisons, ensuring a structured evaluation of subjective criteria. BWM was selected for its consistency and efficiency in deriving reliable weights with fewer comparisons, which is especially valuable in complex, large-scale urban studies25,26.

Recent advancements in QoL evaluation have increasingly leveraged innovative analytical tools, particularly those rooted in ML, deep learning, and a variety of MCDM approaches. Yao et al.27 combined spatial syntax with machine learning algorithms (Random Forest and XGBoost) to evaluate spatial quality from pedestrian perspectives. Etminani-Ghasrodashti et al.28 employed machine learning models such as Random Forests, Decision Trees, and Multilayer Perceptrons to investigate how factors in the built environment affect cancer patients’ QoL. Brodny et al.29 evaluated living conditions in smart sustainable cities using MCDM tools like EDAS and WASPAS. Similarly, Vakilipour et al.30 assessed TOPSIS, VIKOR, ELECTRE, and SAW approaches for measuring urban QoL at various geographical levels. Iamtrakul et al.31 used GIS spatial analysis and deep learning models like OCRNet to investigate the impact of the built environment on transportation-related QoL. Kayiran32 applied machine learning techniques to predict material stress behavior, a predictive modeling strategy that could be adapted to urban QoL assessments to estimate environmental or socioeconomic stressors. Akbulut33 utilized the Grey MARCOS model in complex financial evaluations under ambiguity, highlighting its potential for QoL assessments where variables are uncertain or incomplete. These approaches collectively illustrate the evolution of QoL assessment methodologies towards more data-driven and computationally sophisticated techniques.

Building on traditional MCDM methods like AHP and BWM, recent studies have proposed more sophisticated MCDM techniques like Parsimonious Spherical Fuzzy AHP (P-SF-AHP) and Z-number Parsimonious BWM (Z-PBWM)34,35. For instance, Moslem et al.34 proposed P-SF-AHP, which simplifies pairwise comparisons while allowing experts to express hesitation and ambiguity. However, due to their methodological complexity and the need for specialized knowledge, these advanced methods were not applied in this study.

However, despite their technical strength, these novel methods often face considerable limitations, namely the complexity of model interpretation, heavy reliance on large and often inaccessible datasets, and challenges in addressing subjective uncertainty. To overcome such issues, there has been a growing interest in developing hybrid frameworks that combine the rigor of quantitative methods with the contextual insight of expert judgment. In this regard, the current study proposes an integrated approach that blends the AHP and BWM techniques to elicit expert-derived weights, while simultaneously incorporating objective data through statistical methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Entropy23,24. These statistical tools assist in reducing data dimensionality and objectively determining the weights of indicators, thereby complementing the expert judgment derived from MCDM methods.This dual perspective allows for a more balanced and precise evaluation of QoL by capturing both empirical patterns and domain expertise.

Nevertheless, the incorporation of expert judgment introduces inherent uncertainty, especially when opinions are diverse, incomplete, or conflicting. Traditional models often fall short in addressing these uncertainties effectively. To enhance the reliability and robustness of the proposed framework, this study introduces the Dempster–Shafer Theory (DST) as a complementary mechanism for uncertainty management36,37. DST provides a flexible mathematical framework for combining evidence from multiple sources, allowing for reasoning under both uncertainty and ignorance without requiring precise prior probabilities. Unlike probabilistic models that require predefined distributions, DST enables the fusion of independent evidence sources and allows for reasoning under both uncertainty and ignorance. By integrating DST with AHP and BWM, the framework not only strengthens the methodological rigor but also enhances interpretability and decision confidence, making it a more suitable solution for complex urban environments where data ambiguity is inevitable38,39. This integration offers a distinct advantage over methods like Fuzzy AHP, which are limited to handling vagueness within a single framework, whereas DST facilitates cross-method synthesis and delivers a more transparent decision-making process40.

This study fills the methodological and practical gap in the existing QoL assessment frameworks by integrating qualitative expert-based MCDM techniques (AHP & BWM) with quantitative statistical tools (PCA & Entropy), while enhancing uncertainty modeling through DST. The case of Tehran provides a critical testbed due to its complex socio-environmental dynamics and urban inequities.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: Section "Materials and methods" introduces the proposed methodology in detail, followed by Section "Results and discussion", which presents the results and offers a comprehensive discussion of the findings. Section "Conclusion" concludes the study by summarizing the key insights, and provides suggestions and directions for future research.

Materials and methods

Case study

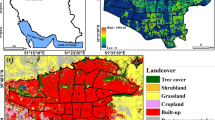

Tehran is located in Tehran Province, in north-central Iran, within the Middle East (Fig. 1). It is the capital and most populated city in Iran41. This city has 22 municipal districts, each with its own administrative center. As of the 2016 census, the city’s population was approximately 8,693,706, making it the 24th most populous metropolis globally and the most populous in Western Asia42. Tehran has major issues such as air and noise pollution, a deficient transportation system, insufficiency and lack of equitable access to urban services, welfare, and public places, particularly in older districts, and a high resident unemployment rate. Because of these circumstances, the study area is a top priority for determining the QoL. The city consistently ranks among the world’s most polluted capitals, with air quality indices frequently exceeding safe levels, leading to significant health concerns. Additionally, traffic congestion exacerbates air pollution, with vehicular emissions accounting for a substantial portion of pollutants30.

Case study/ The authors created the maps using ArcGIS 10.8.1 software (https://support.esri.com).

Proposed methodology

The proposed methodology, demonstrated in Fig. 2, is structured into five integrated steps to comprehensively evaluate urban QoL. First, data were collected and prepared for spatial layers containing physical, environmental, and socioeconomic factors such as accessibility to educational, medical, and recreational facilities; proximity to green spaces and industrial zones; air and noise pollution levels; urban heat island intensity; literacy; and unemployment rates. In the second step, objective statistical analyses were used. PCA was employed to reduce dimensionality and determine the most influential criteria, while Entropy analysis determined each indicator’s inherent variability. These data-driven methods ensured that the assigned weights precisely represented each factor’s factual importance, with no subjective interference.

The third step involved incorporating subjective expert knowledge using two MCDM techniques: the AHP and the BWM. These tools enabled domain experts to express professional judgment about the relative importance of each criterion. However, to deal with the inherent uncertainty and potential inconsistency in expert evaluations, the fourth step employed DST. DST enabled the integration of AHP and BWM outcomes into a unified weighting scheme by accounting for both uncertainty and ignorance, providing an interpretable and mathematically rigorous alternative to other methods.

In step five, the different QoL maps that were created using weights from (PCA + Entropy), AHP, BWM, and DST were compared both visually and quantitatively using metrics like MAE, RMSE, Pearson Correlation Coefficient, and SSIM. This multi-method comparison allowed for the validation of spatial distribution patterns, ensuring that the resulting QoL indices were reliable and actionable. Overall, this hybrid approach, which combines objective statistical rigor with subjective expert insight and is supported by a robust uncertainty-handling framework, provides a practical, scalable model for assessing urban QoL in Tehran and other cities facing complex urban challenges.

Step 1: data collection and preparation

Many factors including physical, socioeconomic, and environmental must be considered, each with distinct analytical units. Therefore, this study determined relevant factors suitable for grid-based analysis. A grid-based technique was employed to prepare spatial data, enabling the identification of distinct areas and integration of multiple datasets43,44. Based on a review of previous research, this study applied a 100 × 100 m grid size, consistent with prior studies that use grid sizes between 100 and 500 meters45.

Table 1 summarizes the indicators and factors used in this study. Before selecting the ten QoL criteria, an extensive literature review was conducted.

These indicators were chosen after a thorough review of existing urban QoL literature, and they were further validated through expert consultation. While the number of indicators is purposefully limited, each was carefully selected to reflect the most important dimensions influencing urban QoL (physical access to services, environmental exposure, and socioeconomic conditions). Various studies have emphasized the significance of access to educational facilities, which are highly associated with long-term personal and societal well-being. Likewise, access to medical and recreational facilities performs a critical role in residents’ health, life satisfaction, and social cohesion. Environmental variables such as green space availability, air pollution, noise pollution, and urban heat islands have been shown to significantly affect both physical and mental health. Finally, literacy and unemployment rates are two widely used socioeconomic indicators that reflect larger issues such as equity, opportunity, and economic stability in urban areas. We have reduced the number of factors to 10 to avoid overloading the experts and to allow for a more transparent and trustworthy rating procedure. Including more criteria may contribute to confusion and inconsistencies in the evaluation process, reducing the assessment’s robustness and clarity. Therefore, the criteria were determined after conducting a thorough assessment of the literature, consulting with experts, and recognizing the practical requirement for a reasonable and successful evaluation framework.

In this study, noise pollution was estimated based on Euclidean distance from the road network. Although urban noise data is typically collected through monitoring stations in many countries, such infrastructure is not available on a city-wide scale in Iran. We used a proximity-based method because there were no high-resolution, direct noise measurements available in Tehran. The approach is based on previous work that shows that traffic-related noise levels highly correlate with distance to major roads, particularly in dense urban environments where vehicular flow is the primary cause of environmental noise54. As a result, we concentrated on these three broad categories and found the most relevant individual elements within each. In addition to the literature study, we discussed with professionals in the field to rank and confirm the significance of these criteria. Experts confirmed the inclusion of these variables. Also,

Table 1 highlights the methods used to create maps for each criterion, which were chosen based on their features and suitability for accurate data representation. Euclidean distance was utilized for Green Space, Noise Pollution, and Industries because it allows for a simple assessment of closeness in a straight line. This technique accurately captures the impact radius of these factors without requiring route-specific considerations. Network distance was chosen for educational, medical, and recreational facilities since they include human contact and real travel pathways are important. Network distance allows for the actual paths that people would travel, offering a more realistic portrayal of accessibility and service reach. Therefore, network distance was utilized for human-related services (such as education, health, and recreation), Euclidean distance was chosen specifically for variables such as green spaces and industrial zones due to their geographical and environmental properties. These elements have a diffuse environmental impact on the surrounding areas, such as air or noise dispersion, visual access, and land use conflict, that is independent of real pedestrian or vehicular paths. As a result, calculating the straight-line proximity to such sources provides a more realistic representation of their environmental risk.

Table 2 presents the significance of each indicator in QoL mapping, along with the costs and benefits of their inclusion.

The detailed explanation of the data fusion process used to generate air pollution and surface temperature maps is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Section S1).

Step 2: statistical analysis

In this study, statistical methods including PCA and Entropy were employed to reduce dimensionality and calculate weights. Prior to PCA, KMO and Bartlett’s tests were used to determine data suitability for factor analysis23,30.

KMO Test value (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin)

The KMO test assesses the sampling adequacy for PCA by evaluating the extent to which variables can be predicted from others in the dataset. A value close to 1 suggests that the data is suitable for factor analysis30. The detailed formula and calculation are presented in the supplementary information (Section S2).

Bartlett’s test of sphericity

The Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity determines whether the correlation matrix deviates significantly from an identity matrix, indicating that the variables are interrelated and appropriate for PCA. A significant test result (p < 0.05) confirms the usefulness of PCA30. The detailed formula and calculation are provided in the supplementary information (Section S2).

Principal component analysis

PCA is a widely used statistical technique for dimensionality reduction, especially when dealing with complex datasets containing numerous correlated variables59. The method transforms the original variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components, which are ordered so that the first few retain most of the variation present in the original data. By doing so, PCA reduces redundancy and reveals the underlying structure of the data60. To identify relationships between variables, the covariance matrix is calculated:

where C is the covariance matrix,\({Z}_{i}\) is the observation value, and \(\overline{Z}\) is the mean vector of the data. Then eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the covariance matrix calculated as follows:

where \({\lambda }_{k}\) is the eigenvalue and \({v}_{k}\) is the eigenvector. Variance for each principal component is as follows:

Entropy

Entropy measures the degree of uncertainty or randomness in data. Criteria with higher variability contribute more to this uncertainty and are considered more influential. In order to calculate weights, the probability distribution of each variable’s values should be computed23. This method calculates the diversity of each criterion’s values across all spatial units and assigns objective weights based on their contribution to the overall uncertainty. In this study, entropy weighting was employed to reduce subjective bias and provide a more data-driven assessment of each indicator’s importance24.

Step 3: multi-criteria decision making

MCDM techniques facilitate complex decision-making by evaluating multiple criteria at the same time61,62. Various studies on spatial analysis of QoL, have used different MCDM techniques such as AHP and BWM. Prakash et al.63 analyzed QoL at the district level in India, based on three pillars of sustainable development. They used AHP to assign weights to indicators and sub-indices. Dissanayake et al.16 constructe a LQI and analyzed its regional distribution. They employed MCDM technique to establish a hierarchy of 13 components selected based on two key criteria: environmental and socioeconomic. Pairwise comparison matrices were generated, and the AHP calculated the weight of each element. Jafarı-Sırızı et al.64 attempted to rate QoL in Tabriz city using a combination of BWM, TOPSIS, and GIS. The BWM approach was used to establish the weighting of criteria. In this study, we adopted an integrated approach combining both AHP and BWM.

AHP is a frequently employed multi-criteria decision-making technique that assigns weights to criteria based on structured expert judgments. It depends on pairwise comparisons to assess the ranking of factors on a numerical scale (typically 1 to 9). AHP is especially beneficial in complex decision-making scenarios where both qualitative and quantitative criteria must be considered30,54,62,63,65,66. Numerous studies have used the AHP method to rank multiple criteria. Abd El Karim and Awawdeh,15 applied AHP to assign weights to public facilities such as hospitals, recreational centers, schools, and security services, which influence QoL. Also, Dissanayake et al.16 conducted expert interviews to identify the criteria, sub-criteria, and factors associated with the AHP.

In this study, the AHP was employed to assign weights to QoL indicators. To ensure a comprehensive evaluation, 20 experts were selected based on their professional backgrounds relevant to urban QoL. The expert panel included five experts in GIS, five specialists in urban planning and development, five experts in environmental science and management, and five professionals in public health and social welfare, with expertise in community well-being, access to services, and social equity. Each expert conducted a pairwise comparison of criteria. Individual responses were averaged to produce the final pairwise comparison matrix. The logical consistency of these comparisons was assessed using the consistency ratio (CR), which is described in the supplementary information (Section S2).

BWM is a structured multi-criteria decision-making technique that uses fewer pairwise comparisons and improves consistency. Experts must identify the most and least important criteria (best and worst) and then compare them to all others. Compared to AHP, BWM reduces inconsistency and the number of comparisons required, making it appropriate for complex decision scenarios22,67. Specifically, BWM requires only 2n − 3 comparisons for n criteria, significantly less than traditional pairwise methods, while a consistency ratio is used to ensure reliable judgments. Additionally, BWM solves a min–max optimization model to derive criterion weights, providing more stable and unique solutions compared to other methods25,68.

In this study, 20 experts were asked to identify the best and worst criteria. The experts had backgrounds in GIS, urban planning, environmental science, and public health and social welfare. Each expert was asked to determine the best and worst criterion, followed by a rating of the relative importance of the best criterion over all others (Best-to-Others) and all others over the worst(Others-to-Worst). These responses were used to determine the optimal weights for each criterion.

Step 4: Dempster–Shafer Theory (DST)

The DST is one of the most effective ways of information fusion. This theory provides a mathematical structure for deciding in the presence of uncertainty, allowing evidence from several independent sources to be combined.36,37,40,69. In the context of this study, DST is employed to combine subjective weights obtained independently from the AHP and the BWM, improving reliability as well as reducing ambiguity.

DST depends on Dempster’s rule of combination, which mathematically combines two belief mass functions m1 and m2 defined in the same frame of discernment. The rule is expressed as:

where K represents the total conflict between the two sources. In this study, both AHP and BWM weight vectors were normalized so that they could be examined as basic belief assignments (BBAs) over singleton sets of criteria. That is, for each criterion i, its normalized AHP and BWM weights, denoted \({\omega }_{AHP}(i)\) and \({\omega }_{BWM}(j)\), are treated as belief masses \({m}_{1}\left(\left\{i\right\}\right)\) and \({m}_{2}\left(\left\{j\right\}\right)\) respectively.

Since belief is assigned only to singleton subsets (individual criteria), the combination rule simplifies to:

This yields the final weight for criterion i, incorporating both AHP and BWM evidence while resolving inconsistencies between them. An illustrative example showing the combination process of weights from AHP and BWM using Dempster’s rule is provided in supplementary information (Section S2).

DST results in a more complete and integrated model36,37,40,70. Al Sharif and Pokharel36 applied DST in a smart city planning, indicating its ability to deal with uncertainty in urban risk analysis. Wang et al.37 proposed a clustering-based MCDM framework that incorporates DST to handle both discrete and continuous uncertain evaluations, improving decision accuracy in large-scale problems. Gorsevski et al.70 applied DST in spatial hazard modelling and demonstrated its effectiveness in combining uncertain spatial data for landslide risk prediction. Furthermore, Tang et al.40 proposed a new correlation belief function within DST that improves evidence fusion in classification tasks, broadening its application in complex decision environments.

In our approach, DST was used to refine the weights derived from AHP and BWM. DST treats the AHP and BWM outputs as separate sources of evidence and fuses them accordingly. This fusion increases the reliability of the final weights. This integration guarantees that the decision-making process is not only based on the best available data, but also resistant to the uncertainties associated with subjective judgments, resulting in more trustworthy and believable outcomes when analyzing QoL.

Finally, Dempster-shapher’s combination rule aggregates the mass functions of all criteria to produce a complete evaluation, effectively addressing uncertainties and improving decision-making accuracy37.

Step 5:comparison QoL maps using quantitative and visual metrics

Comparing different QoL maps helps to validate the findings obtained from multiple methods. When two approaches yield comparable maps, it boosts confidence in the accuracy and dependability of the data71. To compare maps created using different methodologies, the combination of visual assessment and quantitative measurements can be used.

Side-by-side visual comparison helps reveal spatial patterns and discrepancies. This aids in evaluating the general trends and regions with high and low values qualitatively72. The objective evaluation and comparison of the maps’ correctness and similarity is performed using these quantitative measures, which include SSIM, MAE, RMSE, and Pearson correlation coefficient. These metrics quantify errors and assess spatial similarity between maps73,74,75,76. Given that observable data (ground truth) is not accessible, these measures are only utilized to evaluate the performance and results of the two techniques, DST and (PCA + Entropy), in measuring QoL. Although direct validation with observed data is not feasible, comparing projected maps from these two approaches helps us to determine whether strategy gives a more accurate or consistent picture of QoL.

Results and discussion

As previously stated, the QoL was examined following the implementation of a composite index that included multiple criteria. Each criteria represented a domain of QoL and is assessed using a set of indicators. Figure 3 represents the criteria maps produced utilizing the mentioned indicators in Table 1, according to step 1. Based on previous experience and articles, a grid size of 100m by 100m was initially chosen for this study. Euclidean distance analysis was used to create accessibility maps to industrial facilities and green spaces, and noise pollution map. Then, using network distance analysis, accessibility maps to educational, medical, and recreational facilities were generated. The data fusion process was then used to produce air pollution and urban heat island maps, providing an integrated and comprehensive overview of urban QoL.

The criteria maps for QoL evaluation/ The authors created the maps using ArcGIS 10.8.1 software (https://support.esri.com).

According to Fig. 3, the accessibility map of educational and medical facilities reveals areas with limited access to essential services, particularly in peripheral districts, highlighting disparities in service distribution. likewise, the green space accessibility map demonstrates regions with insufficient access to parks and recreational areas, both of which are important for physical and mental health. The air pollution map identifies high pollutant concentration zones, which are frequently located near industrial areas and major transportation routes, ashowing a direct impact on public health. Finally, the urban heat island map identifies areas with elevated surface temperatures as a result of dense development and limited green space.

The noise pollution map, derived from proximity to major road networks, demonstrates that central and high-traffic corridors are experiencing higher noise levels, which may adversely impact residents’ well-being through stress, sleep disruptions, and long-term health consequences.Access to recreational facilities, such as theaters and shopping malls, appears to be uneven, with suburban areas facing more challenges in reaching such amenities.

The industrial proximity map highlights the spatial clustering of industrial zones, particularly in southern Tehran, where environmental burdens are expected to be more severe.ocioeconomic factors supplement this spatial understanding: areas with lower literacy rates are frequently associated with lower service accessibility and higher environmental stress, whereas regions with higher unemployment reflect broader patterns of social vulnerability.

According to step 2, KMO and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity are employed to the 10 criteria for statistical analysis. The high KMO value (0.823) indicates excellent sampling adequacy, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2 = 2,942,548.65, p < 0.001) confirms strong intercorrelations among the variables. These findings support the use of PCA to identify latent structures in the dataset. This step reinforces the robustness of the selected indicators while also supporting the validity of the subsequent dimensionality reduction and weight assignment. Thus, factor analysis not only reduces the complexity of multidimensional data, but it also ensures that key QoL patterns are statistically supported and interpretable.

Table 3 shows the factor loadings for the first three components which indicate the correlation coefficients between observed variables and factors. They represent the extent to which a factor influences a variable. Network distance to educational facilities has factor loadings of − 0.62 on Component 1, − 0.64 on Component 2, and − 0.19 on Component 3. Similarly, network distance to medical facilities loaded at − 0.47 on Component 1, − 0.81 on Component 2, and − 0.18 on Component 3. Variables like Euclidean distance to parks and Euclidean distance to industry facilities have substantial positive loadings on Component 1 (0.87 and 0.88, respectively), but only moderate loadings on the other components. The social variables also revealed interesting trends. “Literacy rates” was largely loaded on Component 3 (0.72), but unemployment rates had a high loading on Component 1 (0.88) and moderate loadings on the remaining components.

While the three-component model first looked to be consistent with theoretical components, subsequent statistical analysis revealed significant flaws. First, the eigenvalues for the second and third components were particularly low (0.91 and 0.48, respectively), implying that they contributed little to explaining variance in the dataset. Second, the factor loadings were quite similar between Component 1 and Component 2, especially for environmental and accessibility variables. Several variables, including Euclidean distance to parks, Euclidean distance to industry facilities, noise pollution, urban heat island, and air pollution, had a significant impact on both components. This pattern identified redundancy among components and suggested reducing their number to improve clarity and interpretability.

Given the limitations found in the three-component model, the factor analysis was recalculated with two components to simplify the factor structure and eliminate redundancy. This adjustment improves the model’s interpretability, as shown in Table 4, by distinguishing between the two primary dimensions of QoL: environmental stressors and service accessibility.

The redesigned two-component structure showed a clearer difference between environmental stressors and accessibility considerations. Component 1 generally caught environmental variables like pollution, urban heat, and industrial closeness, whereas Component 2 mostly represented service accessibility characteristics like distances to school, healthcare, and recreation. To improve factor discrimination, Promax rotation was used instead of Varimax. Unlike Varimax, which assumes independent components, Promax rotation accommodates correlated factors, resulting in a more realistic and interpretable factor structure. This change eliminated the overlap between components seen in the earlier model, resulting in a more meaningful depiction of QoL dimensions.

The resulting two-component model produced a theoretically sound and statistically sound assessment of QoL by ensuring that all criteria were maintained without introducing redundancy.

Table 5 presents the criterion weights calculated using PCA and Entropy methods. Prior to applying these techniques, all variables were normalized using min–max scaling (0–1) to ensure comparability across different data layers with varying units and scales. This normalization step was essential for maintaining consistency in the analysis. For PCA, the eigenvalues and the variance explained by the first three principal components were 8.07, 0.91, and 0.48, respectively. The PCA weights were derived based on the absolute values of the loadings from the first principal component, reflecting the most influential variables in the dataset. In parallel, Entropy weighting was employed to evaluate the significance of each criterion based on its degree of variability, with higher variability indicating greater information contribution. Finally, the combined weights were obtained by averaging the PCA and Entropy weights, offering a balanced estimation that reflects both statistical structure and informational content of the criteria.

The PCA and Entropy weight comparison in Table 5 demonstrates that the majority of criteria have values that are comparatively constant between the two approaches. Nonetheless, several variables show clear disparities, including literacy rates, Euclidean distance to parks, network distance to recreational facilities, and network distance to medical services. This mismatch is mostly due to the basic differences in the way PCA and Entropy allocate weights.

PCA assigns weights depending on the variance contribution of every criteria. If a variable has less variance across the research region, PCA gives it a lower weight because it contributes less to overall differentiation. Entropy weighting, on the other hand, is sensitive to spatial heterogeneity and gives greater weight to variables with considerable local variability, even if their overall variance is minimal. These variations resulted in greater Entropy weights for criterion with skewed distributions, such as literacy rates, whereas PCA assigned lower weights due to their low variance over the whole study area.

To ascertain an equitable representation of both statistical variance and spatial heterogeneity, the arithmetic mean was chosen as the most acceptable method for combining the two weighting systems. This decision ensures uniformity across all criteria by using a uniform calculation procedure that does not favor one technique over another. Furthermore, the arithmetic mean avoids overemphasis on variables with severe outliers, which could affect the final weighting scheme. This is especially crucial for criteria like literacy rates, where highly skewed distributions have a large impact on Entropy weighting, potentially overestimating their value. The arithmetic mean ensures that no single approach dominates the results by combining both PCA and Entropy contributions equally. Another significant benefit of implementing the arithmetic mean is its simplicity and reproducibility. Unlike more complex combination approaches, the arithmetic mean offers a simple and transparent methodology that can be used to a wide range of datasets without adding extra computing complexity. It is a commonly used method in multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), ensuring that the weighing procedure is both methodologically sound and simply interpretable.

Figure 4 presents the weights generated by PCA, Entropy, and their combination.

According to Table 5 and Fig. 4, the network distance to education facilities had a PCA score of 0.103, an Entropy score of 0.145, and a total score of 0.124. Similarly, Network Distance to Medical Facilities received scores of 0.099 (PCA), 0.035 (Entropy), and 0.067 (Combined). In conclusion, the combination of (PCA + Entropy) values gives a solid foundation for evaluating the correlations and implications of numerous criteria in our dataset. The significant KMO value and Bartlett’s test affirm the validity of our factor analysis, while a thorough investigation of loadings and combined scores provides useful insights into the data’s patterns and trends.

Accoroding to step 3, AHP was applied to systematically assess the relative relevance of parameters influencing QoL. To acquire a more thorough comprehension and wider perspective, consultations with specialists, such as professional researchers and municipal employees, were performed. Twenty experts participated in the discussions and were asked to rank ten factors that affect QoL index. The expert assessment were utilized to generate a pairwise comparison matrix. By contributing to the definition of the AHP, this participation made guaranteed that the analysis was based on expert knowledge.The analysis produced a set of weights for the criteria, which is demonstrated in Table 6 (CR = 0.01).

Based on the AHP results, air pollution received the highest weight (0.152), reflecting its critical role in shaping urban QoL, followed by network distance to educational facilities (0.117). Urban heat islands, on the other hand, had a lower weight of 0.065, suggesting that their impact on QoL was perceived as less immediate or severe compared to air pollution and service accessibility. Proximity to educational and healthcare facilities was among the most significant factors, reflecting their critical role in promoting health, human capital development, and long-term social well-being. Although recreational and sports services are beneficial to physical and mental health, they received lower ratings, possibly due to their perceived indirect impact on immediate urban living conditions.

Also, the BWM was employed to ascertain the relative importance of 10 factors influencing urban growth. Expert opinions on the significance of each criterion were provided by twenty participants in the study. Each expert identified the most and least significant factors and ranked the remaining criteria based on their relative importance to these two extremes. A large number of experts agreed that the literacy rate is the best criterion, while the worst criterion is the distance to the park. Expert evaluations were used to produce the Best-Optimal (BO) and Optimal-Worst (OW) vectors for each criterion. Subsequently, the mean BO and OW vectors were calculated across all experts to establish a consensus ranking for each criterion. To determine the weights of the criteria, an optimization problem was designed with the goal of minimizing the difference between expert evaluations and generated weights. As long as the weights are non-negative and add up to 1, the goal was to reduce the maximum possible deviation between the expert evaluations and the generated weights. Sequential Least Squares Programming (SLSQP) was used to perform the optimization. The analysis findings generated a set of weights for the criterion, as shown in Table 7. (CR = 0.001).

According to the BWM results, literacy rates determined as the most critical factor with a weight of 0.210, underscoring the importance of education in urban growth. Conversely, network distance to medical facilities received the lowest weight (0.033), indicating that accessibility to healthcare, while important, was ranked lower than other factors such as education and environmental conditions.

According to step 4, the DST was employed to integrate the results from AHP and BWM, enhancing both the robustness and accuracy of the model by leveraging the complementary strengths of these two methods. This integration provides a more comprehensive and reliable assessment compared to using either method in isolation, reducing uncertainty and increasing confidence in the outcomes. The aggregated weights derived through the DST approach for each criterion are presented in Table 8.

According to the DST results, literacy rates identified as the most significant criterion, with a weight of 0.269, reinforcing its significance across multiple analytical approaches and its central role in urban development. Conversely, the network distance to medical facilities emerged its lower relevance, with a weight of 0.023, suggesting that proximity to healthcare services was identified less critical compared to educational and environmental factors in the context of urban QoL.

Figure 5 represents a linear graph of the weights created by DST as well as the weights from (PCA + Entropy) combined weights.

This comparison identifies major criteria influencing urban living conditions in Tehran. Both methods consistently prioritize network distance to educational facilities, with DST assigning a slightly higher weight (0.152 vs. 0.124), highlighting the critical role of educational access in improving urban QoL. Significant differences are observed in variables such as network distance to medical services (PCA: 0.067, DST: 0.023) and urban heat islands (PCA: 0.106, DST: 0.048), with PCA giving higher weights. These disparities reflect the two methods’ different priorities, which can be employed to direct targeted interventions in healthcare and environmental management. In contrast, DST prioritizes literacy rates (0.269) over PCA (0.152), implying that expert-informed methodologies may prioritize education as a foundation for long-term urban development. These findings imply that, while both methodologies reveal critical aspects such as educational accessibility, weight assignments emphasize differing viewpoints on other criteria, which can help policymakers prioritize efforts to improve urban QoL.

As a conclusion, these findings show that, while both techniques uncover crucial factors such as educational accessibility, weight assignments emphasize divergent opinions on other criteria, which might help policymakers prioritize efforts to improve urban QoL. The observed weight reversal, notably in the ranking of the first three criteria, demonstrates the basic differences between the two methodologies. While (PCA + Entropy) focus on statistical variance and spatial heterogeneity, DST includes evidential reasoning to account for uncertainty in data dependability. This causes a reordering of certain components, as uncertainty plays a larger role in DST, resulting in different prioritization than (PCA + Entropy). This disparity in weight allocation might directly enlighten policymakers by demonstrating how data-driven and expert-informed viewpoints may result in differing prioritizing of urban interventions. For example, although (PCA + Entropy) quantitatively reveals spatial inequalities, DST may boost criteria such as environmental dangers or social justice issues that experts consider significant but have lower statistical variance. Understanding these methodological variations allows decision-makers to strike a balance between quantitative objectivity and contextual expertise, resulting in more inclusive and effective urban development policies.

To visually demonstrate the results, QoLmaps were generated using the AHP, BWM, and DST weights. The spatial distribution of the criteria and the weights produced from the AHP are integrated in this map (Fig. 6), thereby providing a full perspective of locations with various levels of QoL.

Spatial representation of QoL based on calculated weights derived from (PCA + Enropy), AHP, BWM, and DST/ The authors created the maps using ArcGIS 10.8.1 software (https://support.esri.com).

According to Fig. 6, the spatial distribution of QoL utilizing different weighting methods (PCA + Entropy, AHP, BWM, and DST) reveals substantial disparities across Tehran’s districts, shaped by varying prioritizations of criteria. Both DST and BWM place a greater emphasis on literacy rates, demonstrating the importance of educational factors in urban QoL evaluation. In contrast, (PCA + Entropy) and AHP distribute weights more evenly across environmental and accessibility-related variables, implying a broader understanding of what constitutes urban livability. These methodological differences can reveal important insights into how each approach emphasizes different urban priorities, such as education versus environmental health.

The spatial analysis of the maps reveals distinct spatial disparities in QoL across the city. The central and northern districts primarily concentrate high QoL areas, and these districts provide nearby essential services, have improved infrastructure, and offer more readily accessible public amenities. Peripheral neighborhoods, particularly in the southern and western regions, have consistently lower QoL scores. These areas frequently lack access to educational institutions, healthcare facilities, efficient transportation, and green spaces, all of which contribute to decreased urban livability. This spatial disparity reflects underlying urban inequities, implying that residents in marginalized areas face barriers that limit their access to critical resources for well-being. The concentration of higher QoL scores near the city center is consistent with established urban theories emphasizing the importance of centrality in access to services, though the extent of this pattern varies across methods. Notably, DST and AHP demonstrate a more dispersed pattern of QoL distribution, implying a more nuanced understanding of less obvious factors influencing livability beyond mere proximity.

The prominence of literacy rates in DST and BWM methodologies underscores the fundamental role of education in shaping urban QoL. This finding emphasizes that improving educational opportunities in lower-scoring districts may be a pivotal strategy to bridge spatial inequalities. Meanwhile, (PCA + Entropy) and AHP’s broader weighting of environmental and accessibility variables highlight the disproportionate environmental challenges faced by peripheral zones, emphasizing the need for integrated policies that address both the social and ecological dimensions of urban equity. In conclusion, these spatial inequalities highlight critical challenges in achieving equitable urban development and emphasize the importance of targeted interventions that improve access to QoL resources across all city regions. Urban planners and policymakers require a comprehensive understanding of these spatial patterns to promote inclusive and sustainable cities.

The analysis confirms that all maps place better QoL regions near the city center, which is consistent with the expected benefit of proximity to services and infrastructure. However, DST and AHP show more dispersed high-value areas, implying that these methods capture a broader range of QoL factors, including those that are not immediately apparent in proximity-based models. AHP and DST display a wider range of medium-value zones, indicating a more equitable distribution of QoL across regions. DST, in particular, reveals a more dispersed pattern with fewer clearly defined poor QoL zones on the periphery, indicating a more balanced integration of various data sources. In contrast, (PCA + Entropy) demonstrate significant differences between areas with good and poor QoL, emphasizing the importance of environmental factors in shaping urban livability. BWM is similar to (PCA + Entropy), but it prioritizes higher-value areas, demonstrating a focus on environmental and accessibility factors. Finally, DST provides the most dispersed and balanced QoL map, implying that this method better integrates multiple sources of evidence, resulting in a more comprehensive view of urban QoL.

Figure 7 compares different calculated weights from various methods in a radar graph. This graphical representation demonstrates how the importance of each criterion varies across the methods, allowing for a clear comparison of how each technique prioritizes urban QoL factors in Tehran.

Comparing Weight from various methods in radar graph/ Graph created by the authors using Python 3.9. C1: Network distance to education facilities/ C2: Network distance to medical facilities. C3: Network distance to recreational facilities/ C4: Euclidean distance to parks. C5: Euclidean distance to industry facilities/ C6: Noise pollution/ C7: Urban heat island. C8: Air pollution/ C9: Literacy rates/ C10: Unemployment rates.

The radar charts (Fig. 7) compare BWM, AHP, (PCA + Entropy), and DST for QoL criteria in Tehran, revealing significant variances and similarities. All techniques consistently stress C1 (Network distance to educational institutions) and C9 (Literacy rates) as key criteria, with BWM and DST assigning the greatest weights to C1 and C9. AHP has a more balanced distribution across criteria, emphasizing C1, C2 (Network distance to medical facilities), and C9, whereas (PCA + Entropy) likewise maintains a balanced approach, with a focus on C1, C6 (Noise pollution), and C9. DST and BWM, on the other hand, de-emphasize criteria such as C2, C4 (Euclidean distance to parks), C5 (Euclidean distance to industry facilities), C7 (Urban heat island), and C8 (Air pollution), implying that fewer but more impactful criteria should be prioritized, as opposed to AHP and (PCA + Entropy), which distribute weights more evenly across multiple factors .

Although the (PCA + Entropy) method assigns a relatively low weight to literacy rate due to its limited spatial variance, DST emphasizes its importance based on expert evaluations, resulting in a significantly higher weight. While this may seem contradictory at first glance, it in fact reflects the nature of DST’s belief aggregation mechanism: although DST-generated weights often follow the general trends of (PCA + Entropy), in cases like this, it amplifies criteria strongly supported by expert input—even when statistical variance is low.

DST does not simply average values; rather, it sharpens beliefs when strong support is provided by at least one credible source. In this case, AHP and, particularly, BWM rated the literacy rate higher, whereas (PCA + Entropy), which are data-driven and variance-based, rated it lower. DST combined these perspectives by emphasizing the higher belief mass, resulting in a heavier final weight. Such differences are not anomalies but instead highlight DST’s capacity to deal with uncertainty and represent conflicting or imbalanced evidence in a structured and robust manner.

Accroding to step 5, we compared the map generated by DST to the map derived from (PCA + Entropy) to assess its effectiveness. Figure 8 depicts a difference map, which is obtained by subtracting the DST map from the (PCA + Entropy) map. This difference map visually depicts the spatial areas where the two methodologies diverge, revealing regions where each approach prioritizes different aspects of QoL.

A difference map between DST and (PCA + Entropy)/ The authors created the maps using ArcGIS 10.8.1 software (https://support.esri.com).

To quantify these differences, several evaluation metrics were calculated, including RMSE, MAE, Pearson correlation coefficient, and SSIM.

Visual examination of the maps reveals that both maps follow similar patterns, with high and low-value areas overlapping in the majority of regions. However, there are minor differences between the two maps, especially in areas where the values diverge. These variations highlight the methods’ different emphases and sensitivities. To further determine these differences, multiple quantitative metrics were calculated, providing more information for the comparison (Table 9). The MAE value of 0.058 and the RMSE value of 0.068 show the average magnitude of the differences between the two maps, with lower values indicating greater similarity. The Pearson Correlation Coefficient (0.856) indicates a strong positive correlation between the maps, implying that the two methods follow similar spatial patterns and rankings. The high SSIM value of 0.959 suggests the (PCA + Entropy) and DST maps are structurally very similar, with comparable brightness, contrast, and spatial structure. This reveals that both maps have substantially identical spatial patterns and intensity distributions, demonstrating the robustness of the methods used to analyze urban QoL.

Conclusion

This study proposed an integrated framework for evaluating urban QoL in Tehran by combining multiple decision-making methods (AHP, BWM, and DST) with statistical techniques such as PCA and Entropy. This hybrid approach allowed for both expert-driven weighting and data-based validation, enhancing the robustness of the results. Educational accessibility and literacy rates consistently emerged as the most influential criteria across all methods, emphasizing the central role of human capital in shaping urban livability. Moreover, Spatial analysis revealed a clear central-peripheral divide, with central districts enjoying higher QoL scores, while peripheral areas lagged behind, reflecting structural disparities in access to services and environmental quality.

To address these disparities, spatially targeted investments are needed, particularly in underserved peripheral zones, with priority given to infrastructure in education, health, and public transit. Urban planning must also incorporate environmental justice through neighborhood-level interventions such as green space expansion and air quality control. Moreover, institutionalizing the hybrid model developed in this study can enable planning agencies to monitor spatial inequalities and evaluate policy effectiveness using composite QoL indicators at the district level. Cross-sectoral collaboration—bringing together planners, environmental scientists, public health experts, and data analysts—will be essential to implement such integrated approaches effectively.

Looking ahead, future research may enhance this framework by integrating real-time data sources (air quality sensors, traffic APIs), higher-resolution satellite imagery, and advanced machine learning techniques to capture dynamic urban conditions more accurately. Additionally, the use of next-generation MCDM methods such as P-SF-AHP and Z-PBWM could offer more robust and cognitively efficient decision-making under uncertainty. These techniques were not employed in the present study due to their reliance on extensive expert calibration and computational complexity, which may not align with the practical constraints of urban-scale data collection. Nonetheless, future studies could benefit from comparing these advanced models with the current AHP–BWM–DST framework to evaluate their relative effectiveness in urban QoL assessments.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Leitmann, J., Bartone, C. & Bernstein, J. Environmental management and urban development issues and options for Third World cities. Environ. Urban. 4(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/095624789200400213 (1992).

Huang, J. Strategic thinking on the new urbanization road in the era of ecological civilization. Eco Cities 1(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.54517/ec.v1i1.1824 (2020).

Willis, M. D. et al. A population-based cohort study of traffic congestion and infant growth using connected vehicle data. Sci. Adv. 8(43), eabp8281. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abp8281 (2022).

Lo, C. P. & Faber, B. J. Integration of landsat thematic mapper and census data for quality of life assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 62(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(97)00088-6 (1997).

Rinner, C. A geographic visualization approach to multi-criteria evaluation of urban quality of life. Int. J. Geographical Inform. Sci. 21(8), 907–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/13658810701349060 (2007).

Mocuta, D. N. Influence of the climate changes on the human life quality, in rural areas. Rev. Chim. 68(6), 1392–1396. https://doi.org/10.37358/RC.17.6.5680 (2017).

Wesz, J. G. B., Miron, L. I. G., Delsante, I. & Tzortzopoulos, P. Urban quality of life: A systematic literature review. Urban Sci. 7(2), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci7020056 (2023).

Marans, R. W. & Stimson, R. An overview of quality of urban life. Investigating quality of urban life: Theory, methods, and empirical research, 1–29 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1742-8_1

Jun, B.-W. Exploring the spatial relationships between environmental equity and Urban quality of life. J. Korean Associat. Geographic Inf. Stud. 14(3), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.11108/kagis.2011.14.3.223 (2011).

Wang, X. & Zhan, S. Exploring the Spatial Distribution of ICH by Geographic Information System (GIS). Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022(1), 8689113. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8689113 (2022).

Javadi, G. & Taleai, M. Integration of user generated geo-contents and official data to assess quality of life in intra-national level. Soc. Indic. Res. 152(1), 205–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02437-1 (2020).

Dadashpoor, H., Rostami, F. & Alizadeh, B. Is inequality in the distribution of urban facilities inequitable? Exploring a method for identifying spatial inequity in an Iranian city. Cities 52, 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.12.007 (2016).

Bhatti, S. S., Tripathi, N. K., Nagai, M. & Nitivattananon, V. Spatial interrelationships of quality of life with land use/land cover, demography and urbanization. Soc. Indic. Res. 132, 1193–1216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1336-z (2017).

Özdemir Işık, B. & Demir, S. Integrated multi-criteria decision-making methods for the sustainability of historical–cultural structures on the Trabzon Coastline. Sustainability 9(11), 2114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112114 (2017).

Abd El Karim, A. & Awawdeh, M. M. Integrating GIS accessibility and location-allocation models with multicriteria decision analysis for evaluating quality of life in Buraidah city, KSA. Sustainability 12(4), 1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041412 (2020).

Dissanayake, D., Morimoto, T., Murayama, Y., Ranagalage, M. & Perera, E. Analysis of life quality in a tropical mountain city using a multi-criteria geospatial technique: A case study of Kandy City, Sri Lanka. Sustainability 12(7), 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072918 (2020).

Withanage, N. C. et al. A quality of life index for the rural periphery of Sri Lanka using GIS multi-criteria decision analysis techniques. PLoS ONE 19(9), e0308077. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0308077 (2024).

Hussain, A. & Ali, M. A critical estimation of ideological and political education for sustainable development goals using an advanced decision-making model based on intuitionistic fuzzy Z-numbers. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Goals 1, 23–44 (2025).

Badi, I., Bouraima, M. B., Yanjun, Q. & Qingping, W. Advancing sustainable logistics and transport systems in free trade zones: A multi-criteria decision-making approach for strategic sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Goals 1, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.59543/ijsdg.v1i.14213 (2025).

Moslem, S. et al. A comparative assessment of domino accident analysis methods in process industries using LMAW and DNMA techniques. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 260, 110981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2025.110981 (2025).

Ptak-Wojciechowska, A. Use of the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) method to assess the urban quality of life of seniors in terms of architectural and urban planning aspects. Architectus, 80(4), (2024). https://doi.org/10.37190/arc240409

Srdjevic, B., Srdjevic, Z., Reynolds, K. M., Lakicevic, M. & Zdero, S. Using analytic hierarchy process and best–worst method in group evaluation of urban park quality. Forests 13(2), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13020290 (2022).

Merschdorf, H., Hodgson, M. E. & Blaschke, T. Modeling quality of urban life using a geospatial approach. Urban Sci. 4(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci4010005 (2020).

Xiao, K., Tamborski, J., Wang, X., Feng, X., Wang, S., Wang, Q., Lin, D. & Li, H.. A coupling methodology of the analytic hierarchy process and entropy weight theory for assessing coastal water quality. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 1–18 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17247-2

Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 53, 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2014.11.009 (2015).

Saaty, R. W. The analytic hierarchy process—what it is and how it is used. Math. Modell. 9(3–5), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/0270-0255(87)90473-8 (1987).

Yao, T., Xu, Y., Sun, L., Liao, P. & Wang, J. Application of machine learning and multi-dimensional perception in urban spatial quality evaluation: A case study of Shanghai underground pedestrian street. Land 13(9), 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13091354 (2024).

Etminani-Ghasrodashti, R., Kan, C., Arif Qaisrani, M., Mogultay, O. & Zhou, H. Examining the impacts of the built environment on quality of life in cancer patients using machine learning. Sustainability 13(10), 5438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105438 (2021).

Brodny, J., Tutak, M. & Bindzár, P. Measuring and assessing the level of living conditions and quality of life in smart sustainable cities in poland—Framework for evaluation based on MCDM methods. Smart Cities 7(3), 1221–1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities7030052 (2024).

Vakilipour, S., Sadeghi-Niaraki, A., Ghodousi, M. & Choi, S.-M. Comparison between multi-criteria decision-making methods and evaluating the quality of life at different spatial levels. Sustainability 13(7), 4067. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074067 (2021).

Iamtrakul, P. et al. Exploring the spatial effects of built environment on quality of life related transportation by integrating GIS and deep learning approaches. Sustainability 15(3), 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032785 (2023).

Kayiran, H. F. Machine learning-based investigation of stress in carbon fiber rotating cylinders. Knowl. Decis. Syst. Appl. 1, 1–106 (2025).

Akbulut, O. Y. Analysis of the corporate financial performance based on grey PSI and grey MARCOS model in Turkish insurance sector. Knowl. Decis. Syst. Appl. 1, 57–69 (2025).

Moslem, S. A novel parsimonious spherical fuzzy analytic hierarchy process for sustainable urban transport solutions. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 128, 107447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107447 (2024).

Moslem, S. Evaluating commuters’ travel mode choice using the Z-number extension of Parsimonious Best Worst Method. Appl. Soft Comput. 173, 112918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2025.112918 (2025).

Al Sharif, R. & Pokharel, S. Risk analysis with the dempster–shafer theory for smart city planning: The case of qatar. Electronics 10(24), 3080. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10243080 (2021).

Wang, S., Ma, W. & Zhan, J. A clustering multi-criteria decision-making method for large-scale discrete and continuous uncertain evaluation. Entropy 24(11), 1621. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24111621 (2022).

Curley, S. P. The application of Dempster–Shafer theory demonstrated with justification provided by legal evidence. Judgment Decision Making 2(5), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500000590 (2007).

Albogami, S. M., Ariffin, M. K. A. B. M., Supeni, E. E. B. & Ahmad, K. A. A new hybrid AHP and dempster—shafer theory of evidence method for project risk assessment problem. Mathematics 9(24), 3225. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9243225 (2021).

Tang, Y., Zhang, X., Zhou, Y., Huang, Y. & Zhou, D. A new correlation belief function in Dempster–Shafer evidence theory and its application in classification. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 7609. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34577-y (2023).

Kazemi, Z. et al. Hidden health effects and economic burden of stroke and coronary heart disease attributed to ambient air pollution (PM2.5) in Tehran, Iran: Evidence from an assessment and forecast up to 2030. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 286, 117158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117158 (2024).

Rad, A. K. et al. Machine learning models for predicting interactions between air pollutants in Tehran Megacity, Iran. Alex. Eng. J. 104, 464–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.08.023 (2024).

Kim, K., Pant, P. & Yamashita, E. Accidents and accessibility: Measuring influences of demographic and land use variables in Honolulu, Hawaii. Transp. Res. Record 2147(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.3141/2147-02 (2010).

Iamtrakul, P. et al. Exploring the spatial effects of built environment on quality of life related transportation by integrating GIS and deep learning approaches. Sustainability 15(3), 2785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su1503278510.3390/su15032785 (2023).

Mao, R., Bao, Y., Huang, Z., Liu, Q. & Liu, G. High-resolution mapping of the urban built environment stocks in Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54(9), 5345–5355. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b07229 (2020).

Bertram, C. & Rehdanz, K. The role of urban green space for human well-being. Ecol. Econ. 120, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.10.013 (2015).

Zhang, F. & Qian, H. A comprehensive review of the environmental benefits of urban green spaces. Environ. Res., 118837, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.10.013

Kaczynski, A. T. & Henderson, K. A. Environmental correlates of physical activity: A review of evidence about parks and recreation. Leis. Sci. 29(4), 315–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400701394865 (2007).

Brender, J. D., Maantay, J. A. & Chakraborty, J. Residential proximity to environmental hazards and adverse health outcomes. Am. J. Public Health 101(S1), S37–S52. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300183 (2011).

Pope, C. A. III. & Dockery, D. W. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 56(6), 709–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485 (2006).

Seidman, M. D. & Standring, R. T. Noise and quality of life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7(10), 3730–3738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-021-10474-7 (2010).

Oke, T. R. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 108(455), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49710845502 (1982).

Mouratidis, K. Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities 115, 103229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103229 (2021).

Maserrat, Z., Alesheikh, A. A., Jafari, A., Charandabi, N. K. & Shahidinejad, J. A Dempster–Shafer enhanced framework for urban road planning using a model-based digital twin and MCDM techniques. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 13(9), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi13090302 (2024).

Eriksson, M. K. et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness of a 3-year trial of lifestyle intervention in primary health care. Arch. Intern. Med. 170(16), 1470–1479. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.301 (2010).

Dos Santos Silva, E. K. et al. Cost-effectiveness in health: Consolidated research and contemporary challenges. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00940-5 (2021).

Macků, K. & Barvíř, R. Quality of life indices: How robust are the results considering different aggregation techniques?. J. Maps 19(1), 2126801. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2022.2126801 (2023).

Brent, R. J. Cost-benefit analysis versus cost-effectiveness analysis from a societal perspective in healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(5), 4637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054637 (2023).

Bai, L., Wang, J., Ma, X. & Lu, H. Air pollution forecasts: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15(4), 780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15040780 (2018).

Núñez-Alonso, D., Pérez-Arribas, L. V., Manzoor, S. & Cáceres, J. O. Statistical tools for air pollution assessment: Multivariate and spatial analysis studies in the Madrid region. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2019(1), 9753927. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9753927 (2019).

Barjasteh-Askari, F., Nabizadeh, R., Najafpoor, A., Davoudi, M. & Mahvi, A.-H. Multi-criteria decision-making for prioritizing photocatalytic processes followed by TiO2-MIL-53 (Fe) characterization and application for diazinon removal. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 7086. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34306-5 (2023).

Taherdoost, H. & Madanchian, M. Multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) methods and concepts. Encyclopedia 3(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia3010006 (2023).

Prakash, M., Shukla, R., Chakraborty, A. & Joshi, P. Multi-criteria approach to geographically visualize the quality of life in India. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 23(6), 469–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2016.1141119 (2016).

Jafarı-Sırızı, R., Oshnooeı-Nooshabadı, A., Khabbazı-Kenarı, Z. & Sadeghı, A. Determination of the QUALITY OF LIFE USING HYbrid BWM-TOPSIS Analysis: Case study of Tabriz (District 1, 2, 3 and 8) Iran. Türkiye Uzaktan Algılama Dergisi 4(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.51489/tuzal.106657810.51489/tuzal.1066578 (2022).

Elaalem, M., Comber, A. & Fisher, P. A comparison of fuzzy AHP and ideal point methods for evaluating land suitability. Trans. GIS 15(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9671.2011.01260.x (2011).

Zhan, Y. et al. Risk assessment of land subsidence in Shanghai municipality based on AHP and EWM. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 7339. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91109-6 (2025).

Tahura, S. S., Shabur, M. A. & Nuva, T. J. BWM analysis of online and offline learning effectiveness in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 8377. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92831-x (2025).

Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method: Some properties and a linear model. Omega 64, 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2015.12.001 (2016).

An, Y., Li, L., Gao, H., Luo, Z. & He, Y. Fusing multiple source data for foundation excavation risk assessment based on cloud model and Dempster Shafer evidence theory. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 9894. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-94628-4 (2025).

Gorsevski, P. V., Jankowski, P. & Gessler, P. E. Spatial prediction of landslide hazard using fuzzy k-means and Dempster–Shafer theory. Trans. GIS 9(4), 455–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9671.2005.00229.x (2005).

Congalton, R. G. & Green, K. Assessing the accuracy of remotely sensed data (CRC Press, 2008). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420055139.

Brewer, C. A., MacEachren, A. M., Pickle, L. W. & Herrmann, D. Mapping mortality: Evaluating color schemes for choropleth maps. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 87(3), 411–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.00061 (1997).

Brunelli, U., Piazza, V., Pignato, L., Sorbello, F. & Vitabile, S. Two-days ahead prediction of daily maximum concentrations of SO2, O3, PM10, NO2, CO in the urban area of Palermo, Italy. Atmospheric Environ. 41(14), 2967–2995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.12.013 (2007).

Fan, J. et al. Evaluating the effect of air pollution on global and diffuse solar radiation prediction using support vector machine modeling based on sunshine duration and air temperature. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 94, 732–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.06.029 (2018).

Adler, J. & Parmryd, I. Quantifying colocalization by correlation: the Pearson correlation coefficient is superior to the Mander’s overlap coefficient. Cytometry A 77(8), 733–742. https://doi.org/10.1002/cyto.a.20896 (2010).

Wang, Z., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13(4), 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2003.819861 (2004).

Acknowledgements

This work has been partially supported by the Center for International Scientific Studies & Collaborations (CISSC), Ministry of Science Research and Technology of Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alireza Zhalehdoost wrote the main manuscript text. Mohammad Taleai reviewed the manuscript for accuracy and clarity. Both authors supervised the research process, contributed to the conceptual framework, and engaged in critical revisions to enhance the overall quality of the work. Additionally, they collaborated on refining the methodology and ensuring the integrity of the findings. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material