Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) constitutes a neurodegenerative disorder predominantly observed in the geriatric population. If AD can be diagnosed early, both in terms of prevention and treatment, it is very beneficial to patients. Therefore, our team proposed a novel deep learning model named 3D-CNN-VSwinFormer. The model consists of two components: the first part is a 3D CNN equipped with a 3D Convolutional Block Attention Module (3D CBAM) module, and the second part involves a fine-tuned Video Swin Transformer. Our investigation extracts features from subject-level 3D Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data, retaining only a single 3D MRI image per participant. This method circumvents data leakage and addresses the issue of 2D slices failing to capture global spatial information. We utilized the ADNI dataset to validate our proposed model. In differentiating between AD patients and cognitively normal (CN) individuals, we achieved accuracy and AUC values of 92.92% and 0.9660, respectively. Compared to other studies on AD and CN recognition, our model yielded superior results, enhancing the efficiency of AD diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals afflicted with AD predominantly constitute the elderly. Its main manifestations include gradual memory impairment, cognitive dysfunction, personality changes, and language difficulties, significantly impacting social, occupational, and daily functioning. As reported by the Alzheimer’s Association in 2023, an estimated 6.7 million American seniors, those 65 years old and over, suffer from AD. Unless there are medical breakthroughs in prevention, slowing down, or curing AD, this number could increase to 13.8 million by 20601.

The human brain possesses an extraordinarily complex internal structure, where elucidating its structural and functional attributes is pivotal for deducing the etiology of various psychiatric disorders, a focal point of contemporary scientific inquiry. The development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology has greatly propelled advances in brain science research. MRI technology generates detailed images by measuring the signals of atomic nuclei within the human body and their interactions with a strong magnetic field. Widely employed in clinical medicine, neuroscience, and research, MRI provides high-resolution, multi-level anatomical, and functional information. MRI is a kind of professional medical imaging technology. It accurately reflects structural and functional changes in different brain tissues, characterizing morphological changes and metabolite concentrations within the brain. Therefore, this technology has shown good application effectiveness and reliable detection capabilities in the early identification of diverse neurodegenerative conditions like AD2.

In recent years, deep learning models utilizing whole-brain MRI images have made significant progress in predicting and identifying AD. The predictive accuracy of these algorithms has even surpassed that of experts in the field of AD3. Currently, there are two main types of MRI data used in deep learning algorithms. The first involves using 2D MRI slices. In this process, MRI is employed to partition the cerebral structure along a specified plane, yielding a sequence of 2D slices. where the MRI of a person’s brain is sliced along a certain axis to obtain a series of 2D images. Due to the high similarity between adjacent slices, this method of dataset partitioning suffers from data leakage, rendering the results unreliable. The second approach utilizes 3D whole-brain MRI images at the subject level, where each patient’s data consists of a single MRI scan. This method completely avoids data leakage and ensures that the obtained results are genuine and reproducible. The data used in this study comprises 3D whole-brain MRI images, thus mitigating concerns related to data leakage.

As computer vision progresses continuously, a multitude of remarkable algorithm models have surfaced. After studying the model proposed by Liu et al.4, we gained some insights. Thus, our contribution is the formulation of a novel deep learning architecture, designated as 3D-CNN-VST, amalgamating the 3D Convolutional Neural Network with the Video Swin Transformer modality, for the early identification of AD. The 3D-CNN-VST combines the advantages of 3D CNN in extracting local features from 3D MRI images and the advantages of Video Swin Transformer in multi-scale feature fusion. It comprehensively captures the pathological features of participants’ whole-brain MRI images, thereby enabling better identification of AD patients.

The salient contributions of this research are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

The 3D Convolutional Block Attention Module (3D CBAM) was proposed and incorporated into 3D CNN, which enhances the model’s capability to capture crucial features in volumetric data and weight information from different regions. This augments the model’s aptitude for discerning localized attributes within cerebral MRI scans.

-

(2)

Proposed the 3D-CNN-VSwinFormer model by integrating a 3D CNN with CBAM module and Video Swin Transformer, the model integrates the advantages of CNNs in capturing local features and Transformers in extracting global features, and validated its performance on the ADNI dataset.

-

(3)

In the absence of data leakage, the proposed model was evaluated against other existing studies, showing superior diagnostic efficacy in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Subsequent sections: Section II summarizes relevant literature and analyzes the impact of data leakage. Section III provides a detailed introduction to the constructed 3D-CNN-VSwinFormer model. Section IV delineates the experimental outcomes and furnishes comparative analyses with extant research. Section V outlines the experimental procedures and the obtained results. Section VI synthesizes the scholarly work and proffers perspectives on prospective research trajectories.

Related works

In this section, I will introduce the mainstream methodologies for the detection and diagnosis of AD in contemporary research. Additionally, my analysis will concentrate on the burgeoning utilization of deep learning for the precursory detection and diagnosis of AD. The mainstream early diagnosis methods for AD primarily fall into following categories.

Region of interest (ROI)-based analysis

ROI-based analysis in the field of neuroimaging can be traced back to around the year 2000. ROI-based analysis was a widely used method for automated AD diagnosis in earlier years. Upon the artificial demarcation of the ROI, it may serve as a characteristic for disease diagnosis. Based on the quantity of delineated ROIs, the approach can be bifurcated into single ROI methods5 and multi-ROI methods6,7,8.

Chupin et al.9 utilized a fully automated segmentation technique to delineate the hippocampus, which was subsequently applied for the identification of AD patients. The yielded experimental outcomes demonstrated a 76% accuracy rate in the correct identification of individuals with AD. Ahmed et al.7 integrated visual characteristics of the hippocampus with the volume of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to formulate a diagnostic framework for AD. They employed post-fusion to enhance the accuracy of the results. This methodology culminated in an 87% rate of diagnostic precision. Liu et al.10 utilized 83 regions of interest (ROIs) to represent features of the entire brain. The findings suggest that this approach is viable for the recognition of AD.

Diagnosis of AD based on biomarkers

This involves using specific molecules or substances detected within the body to diagnose diseases. In recognition research of AD, biomarkers mainly consist of proteins associated with the disease, particularly β-amyloid (Aβ) and tau proteins. The detection of these biomarkers typically involves blood tests, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sampling, or molecular imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET).

Palmqvist et al.11 utilized plasma tau 217 (P-tau217) as a biomarker for AD diagnosis. Experimental findings indicated that the incorporation of P-tau217 could reliably differentiate AD from alternative neurodegenerative conditions. Moreover, its performance showed no significant difference from CSF or PET biomarkers. Lee et al.12 proposed a non-invasive method for diagnosing AD and predicting its future risk of onset. Experimental findings revealed that the secretion levels of Aβ42 were more than double in all AD cases compared to the control group.

AD diagnosis based on machine learning

The utilization of machine learning techniques for the diagnosis of AD has attracted considerable interest in the scientific community over recent years. The application of machine learning classification models for diagnosing AD has yielded promising results.

Kloppel et al.13 employed linear support vector machines for classifying AD and CN subjects, highlighting the utility of SVM in AD diagnosis. Peng et al.14 utilized brain MRI images and genetic data as input features and employed multi-kernel learning with support vector machines for subject classification. They utilized leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) to identify the optimal model.

AD diagnosis based on deep learning

Deep learning is a branch of machine learning. Its main characteristic is the inclusion of multiple layers (depth) of neural networks, which pass learned features layer by layer to accomplish tasks. Compared to general machine learning methods, deep learning models, while not as interpretable, exhibit greater accuracy in AD detection. They also automatically extract features without the need for specialized medical image knowledge. Deep learning is currently the most prominent branch of artificial intelligence, with various models continuously emerging. Within computer vision, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) are arguably the most prominent visual models. It have achieved significant success in the realm of image processing, with widespread deployment in tasks including image or video classification, recognition, and object detection.

For medical images such as MRI brain scans, using CNN is highly suitable. To date, researchers have proposed numerous CNN architectures, including AlexNet, VGGNet, ResNet, DenseNet, MobileNet, EfficientNet, ConvNext, and many others. The advent of the Vision Transformer (ViT) has been a recent innovation, astutely transferring the Transformer architecture from the realm of natural language processing to visual tasks15. Subsequent to the proposition of the ViT model, an array of Transformer-based visual models have gradually been introduced, such as DETR and Swin Transformer, to name a few.

Using deep learning for AD diagnosis, MRI data inputted into the deep learning model can mainly be classified into two types: 2D slices and 3D whole-brain MRI. MRI brain images are three-dimensional image data, with corresponding three dimensions: coronal, sagittal, and axial planes.

The first approach involves slicing the 3D MRI brain image along different dimensions, typically retaining only several dozen 2D slices from the middle portion. This is because the information contained in the initial and final slices, resembling the shape of an ellipsoid, is minimal. The obtained slices are then fed into a deep learning model for training. Since this method is based on 2D slice images, the utilized deep learning models are also 2D, such as 2D CNN and 2D ViT.

The use of 2D slices can greatly risk data leakage, a concern that is often overlooked by researchers. Based on my extensive experimentation and literature review, as described by Ekin et al.16, utilizing 2D slice datasets for training resulted in an erroneous 29% increase in accuracy on the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). This error arises because some researchers, when slicing 3D MRI images, retain several slices per patient, and the adjacent slices of each patient are highly similar. Subsequently, these slices are randomly partitioned into training, validation, and test sets. Therefore, these similar slices inevitably exist in both the training, validation, and test sets, leading to data leakage.

Some studies based on 2D slice analysis include Liu et al.17, who utilized a depthwise separable CNN for AD detection, achieving a final experimental accuracy of 91%. Ahmad et al.18 proposed a CNN model for classification of AD, achieving a 99% accuracy rate in a three-class task distinguishing between mild, normal, and AD. Jain et al.19 applied VGG16 for early AD detection, resulting in a final accuracy of 95%. Farooq and colleagues20 proposed a deep CNN model for classifying AD, MCI, LMCI, and CN, achieving an experimental accuracy of 98.8%. Ramzan et al.21 realized a 100% accuracy rate in a quintuple-class categorization endeavor associated with Alzheimer’s disease. These studies may suffer from potential data leakage issues, casting doubt on the experimental results and warranting further scrutiny regarding their reliability and applicability.

The second approach involves subject-level classification, where instead of slicing 3D MRI, the entire volume undergoes preprocessing before being fed into a deep learning model for training. This constitutes a 3D image classification task, employing 3D deep learning models such as 3DCNN and 3D ViT. Training with 3D MRI inevitably entails increased computational complexity and training time. However, due to the richer information on brain structural changes contained in 3D MRI images, feature extraction through 3D algorithms allows for better identification of AD-related pathologies. Consequently, the diagnostic performance obtained is expected to surpass that of 2D approaches significantly. Therefore, the training data utilized in this study is based on 3D subject-level MRI, and the proposed model is also a 3D medical image model.

Chen et al.22 integrated slice-level attention mechanisms within 3D CNN and utilized comprehensive brain MRI to diagnose AD. The team introduced a slice-level attention to highlight particular 2D slices and eliminate redundant features. Following this, a 3D CNN was employed to globally capture structural changes at the subject level. The model achieved accuracies of 91.1% for AD detection and 80.1% for MCI prediction on the ADNI-1. Li et al.23 combined ResNet and Transformer for AD diagnosis. To address the issue of small datasets, the authors first pre-trained their model on large-scale datasets and then applied transfer learning to achieve higher performance. Liu et al.24 proposed an unsupervised learning neural network for feature extraction followed by clustering, achieving an 84% accuracy in AD vs. CN classification tasks. Lu et al.25 employed Inception-ResNet-V2 as the base model for transfer learning in AD diagnosis, achieving a 90.9% accuracy on the ADNI dataset.

The mentioned studies generally avoid the issue of data leakage. However, it’s crucial to note that even in 3D subject-level classification, precautions against data leakage are necessary. Sequential MRI scans from an individual patient, captured at distinct temporal intervals, should not be concurrently included in the training, validation, and testing datasets. To mitigate this concern, our approach in this paper is to select only one 3D MRI image per patient. This strategy effectively circumvents data leakage, ensuring that the experimental results are both authentic and reproducible.

Methods

This section presents the methodological framework relevant to our work, encompassing the 3D Convolutional Attention Mechanism (3D CBAM) and Video Swin Transformer. Subsequently, we provide a detailed exposition of the 3D-CNN-VSwinFormer model constructed in this study. The code for the model can be obtained from: https://github.com/Yiming0110/3D-CNN-VswinFormer.

3D-CBAM

Woo et al.26 introduced the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) in 2018, presenting a simple yet effective feedforward neural network attention mechanism. CBAM serves as a lightweight and versatile module seamlessly integrable into any CNN architecture, incurring negligible overheads. Integration of CBAM into various CNN models has consistently led to performance enhancements in classification and detection tasks. However, as CBAM was originally designed for 2D convolutions, whereas our task involves 3D data, we were inspired by Woo et al. to propose 3D-CBAM. Experimental results indicate performance improvements for our task with 3D-CBAM. The following figure provides an overview of 3D-CBAM.

The input feature map is denoted as \(F \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{C \times D \times H \times W}}\). As illustrated in Figs. 1. 3D-CBAM sequentially derives the 1D channel attention map \({M_c} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{C \times 1 \times 1 \times 1}}\) and the 3D spatial attention map \({M_s} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{1 \times D \times H \times W}}\). The entire procedure can be outlined as follows:

Where \(\otimes\) denotes multiplication conducted on an element-by-element basis, \(\:{M}_{C}\) represents the 3D channel attention module, and \(\:{M}_{S}\) denotes the 3D spatial attention module. \(F^{\prime}\) represents an intermediary product, while \(F^{\prime\prime}\) constitutes the ultimate output. The procedural methodology for computing channel attention and spatial attention is delineated in Fig. 2. The following details the two attention modules in 3D-CBAM.

3D channel attention module

The basic idea of channel attention is to learn the weights of each channel and then apply these weights to the corresponding feature maps. This allows the network to more flexibly focus on channels that are meaningful for solving specific tasks, thereby improving the network’s performance. The core idea is to utilize the relationships between channels of features to generate channel attention maps27.

Initially, two 3D pooling operations are utilized, specifically 3D average pooling and 3D max pooling, to aggregate the spatial information of the 3D feature maps from 3D MRI scans. This results in two parameters, \(F_{{avg}}^{c}\) and \(F_{{\hbox{max} }}^{c},\) which correspond to the feature matrices derived from these pooling operations. These matrices are subsequently input into a fully connected layer to produce the 3D channel attention map, denoted as \({M_c} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{C \times 1 \times 1 \times 1}}\). Following this, an element-wise summation of the feature vectors is conducted. To encapsulate, the computation of 3D channel attention is as described by Formula (2).

Herein, F denotes the input feature map, σ symbolizes the sigmoid activation function, and fc is indicative of the fully connected layer.

3D Spatial attention module

The core idea of spatial attention is to learn the weights for each spatial position, allowing the network to enhance or diminish the representation capacity of specific positions at different layers28.

In a similar vein, we utilize two pooling operations, average and maximum, to amalgamate the channel information of the 3D feature maps, yielding a pair of 3D maps: \(F_{{avg}}^{s} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{1 \times D \times H \times W}}\) and \(F_{{\hbox{max} }}^{s} \in {{\mathbb{R}}^{1 \times D \times H \times W}}\). Then, we concatenate these features and apply a 3D convolution operation with a kernel size of 7 and padding of 3. In summary, the calculation of 3D spatial attention is illustrated by Formula (3).

Herein, F denotes the input feature map, σ symbolizes the sigmoid activation function, and \({f^{7 \times 7}}\) is indicative of the convolution with a 7 × 7 kernel.

Video Swin transformer

Mentioning Video Swin Transformer4 inevitably leads to the discussion of Swin Transformer29. Video Swin Transformers are an enhancement built upon the foundation of Swin Transformers, enabling them to tackle tasks in the realm of video processing. Video Swin Transformer treats videos as sequences of images and applies Swin Transformer in the temporal dimension. In our MRI classification task, we retain the central 64 slices of the transverse plane. After computation with 3DCNN, we obtain a feature map of size (112, 112, 32) as the input to the Video Swin Transformer module. Figure 3. depicts the architecture of the Video Swin Transformer model.

Video Swin transformer block

Figure 3. illustrates the core structure of the Video Swin Transformer block. This block utilizes an attention mechanism predicated on a 3D sliding window multi-head self-attention (MSA) mechanism (detailed in Sect. 3D shifted window based MSA module), representing an innovative enhancement. In essence, the Video Swin Transformer is composed of an MSA module based on the 3D sliding window and an MLP module. Interposed between these two modules is Layer Normalization (LN) for standardization. Additionally, residual connections are implemented subsequent to each module. The calculation formula for the Video Swin Transformer block is represented by Formula (4).

Where \({\hat {z}^l}\) and \({{\text{z}}^l}\) respectively represent the output feature maps of the 3D(S)-W-MSA module and the MLP module in the l block; 3D-W-MSA and 3D-SW-MSA represent the multi-head self-attention with conventional window and the multi-head self-attention based on the shifted window, respectively.

3D shifted window based MSA module

Following4, let’s assume the given MRI consists of \(D^{\prime} \times H^{\prime} \times W^{\prime}\) 3D tokens, and the 3D window size is \(P \times M \times M.\) The windows partition the 3D MRI input uniformly and non-overlappingly, resulting in a total of \(\left\lceil {\frac{{D^{\prime}}}{P}} \right\rceil \times \left\lceil {\frac{{H^{\prime}}}{M}} \right\rceil \times \left\lceil {\frac{{W^{\prime}}}{M}} \right\rceil\) windows. Taking our task as an example, suppose the size of the input MRI token is \(16 \times 56 \times 56,\) and the window size is \(8 \times 7 \times 7\). Then, at layer l, the number of windows is \(2 \times 8 \times 8=128.\) Multi-head self-attention is performed within each 3D window. Formula (5) illustrates the computation of self-attention.

In the equations, Q, K, and V denote the query, key, and value matrices, respectively, where d represents the dimension of the query and key features.

3D-CNN-VSwinFormer

Taking inspiration from the achievements of Video Swin Transformer in video classification, Fig. 4 illustrates the architecture of the proposed 3D-CNN-VSwinFormer model. The preprocessed MRI data can be fed into the model for training (detailed in Sect. 4). As Video Swin Transformer essentially treats video input as a sequence of consecutive frames, the default output size is \(32 \times 224 \times 224\)(\(D \times H \times W\)), representing a video composed of 32 frames of size \(224 \times 224\). Subsequently, the data undergoes Patch Embedding to compress it to a size of \(16 \times 56 \times 56\), with the default window size being \(8 \times 7 \times 7\).

We observe that Video Swin Transformer computes multi-head self-attention within the window with minimal sliding in the first dimension, D. While this significantly reduces computational overhead, it may compromise the extraction of crucial information along the first dimension. This approach works well for video classification tasks, as videos consist of sequential frames with subtle changes between consecutive frames, requiring less information retention. However, for our MRI classification task, as MRI data is in the form of 3D medical images, information along any dimension is valuable. However, if 3DSwinTransformer is used to calculate multi-head self-attention by sliding Windows in all dimensions, the training time consumed will be multiplied, and the training effect will not increase significantly. So, we adopt compromise approach, first utilize a 3D-Res-Dw CNN module to extract information from each dimension and then employ a Video Swin Transformer module to capture global features.

3D-Res-Dw CNN module

For this 3D-Res-Dw CNN module, we employed the CenterSpatialCrop function from the monai package to crop the input size to \(1 \times 64 \times 112 \times 112\)(\(C \times D \times H \times W\)). Within this module is a 3D convolution characterized by a kernel size of 3, a stride of 1, and padding of 1, alongside a suite of 3D depth-wise (Dw) convolutions. Group Normalization is used for normalization, and a 3D CBAM module is incorporated between each convolution. Inspired by ResNet, we applied a residual connection to add the output feature maps of the convolutional layers to the original input feature maps. Finally, a 3D MaxPooling operation is used to downsample the feature maps to \(3 \times 32 \times 112 \times 112\)(\(C \times D \times H \times W\)).

Vide Swin transformer module

For the Video Swin Transformer module, we made some improvements compared to Liu et al.4. The original Video Swin Transformer takes input of size 32 × 224 × 224, while our input is \(32 \times 112 \times 112.\) To adapt to the input feature map size of this work, we changed the patch size from (2, 4, 4) to (2, 2, 2). This allows us to obtain token sizes of \(16 \times 56 \times 56\) through Patch Embedding. Choosing this input size better suits preprocessed MRI data and also reduces computational complexity. We use Patch Merging for downsampling, reducing the spatial resolution of the feature map while allowing interactions between larger receptive field patches to extract more global spatial information. In this paper, we chose the tiny version of the Video Swin Transformer, with specific hyperparameters including:

Swin-Tiny: C = 96, layer numbers = {2, 2, 6, 2}.

where C represents the number of channels in the hidden layers of the initial stage. The default window size is \(8 \times 7 \times 7.\) Each head of the query dimension is set to d = 32, and the expansion layer of each MLP is configured as α = 4.

Dataset and evaluation criteria

MRI dataset preprocessing

The research conducted by our team employed whole-brain MRI data acquired from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). ADNI serves as an extensive medical imaging repository, providing imaging data pertinent to Alzheimer’s disease at no cost to investigators. To date, ADNI has executed four distinct phases of research: ADNI-1, ADNI-GO, ADNI-2, and ADNI-3. The MRI datasets utilized in our investigation were derived from these collective phases. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org.

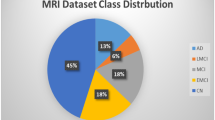

In our work, 798 MRI images were obtained from the ADNI database. To avoid data leakage and ensure the authenticity and reproducibility of the experiments, only one image per subject was retained. The 798 images correspond to 798 subjects. Table 1 presents the demographic information of the subjects.

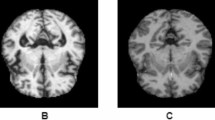

MRI preprocessing is necessary because the pristine MRI datasets could potentially be influenced by a multitude of extraneous variables, thus reducing the quality of the images and affecting the reliability of subsequent analyses. Preprocessing is instrumental in eliminating noise that may be introduced during the data collection process, thereby allowing the model to concentrate on the morphological variances within the brain structures of the subjects30. Irrelevant factors such as the subjects’ skull and neck can also impact model training, leading to slow convergence or even failure to converge. As depicted in Fig. 5, the MRI data undergo preprocessing, displaying only one slice of the axial view. First, we perform skull stripping to extract the brain from the original MRI scans, removing non-brain tissues such as the skull and neck. Then, we conduct image registration to map the images of different subjects to a common standard space, eliminating individual differences and facilitating comparisons and analyses at the population level. The standard space template used for registration is the MNI152 template, with a spatial resolution of each voxel. Following registration, all images are resized to \(182 \times 218 \times 182{\text{ }}\left( {X \times Y \times Z} \right)\). Finally, we apply smoothing with a 4 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian filter.

All preprocessing operations were performed using FMRIB Software Library (FSL)31. FSL is a software toolkit designed for analyzing functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI and sMRI) data, developed by the functional magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (FMRIB) Analysis Group at the University of Oxford. In this study, the following FSL commands were utilized: The BET command was used for brain extraction. The Flirt command was employed for image registration. The Fslmaths command was utilized for smoothing.

It is noteworthy that during the first step of brain extraction, some images may not have the skull and neck completely removed. In such cases, it is necessary to manually inspect and adjust parameters before re-executing the BET command to ensure proper brain extraction. Failure to do so may adversely affect model training and convergence. The final dataset comprises 798 preprocessed MRI images, with 360 from AD patients and 438 from CN individuals.

Evaluation criteria

In this study, four evaluative metrics were utilized to substantiate the efficacy of the model we introduced. These encompass accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC). The formulas are as follows:

In the context of this study, TP, TN, FP, and FN denote true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Accuracy serves as a fundamental evaluation metric, describing the probability of correct prediction outcomes. Sensitivity can be understood as the probability that the model correctly predicts all positive instances in the sample, representing the disease detection rate. Specificity, on the other hand, signifies the probability that the model accurately predicts all negative instances in the sample. AUC is particularly robust in handling class imbalance issues. In situations of class imbalance, metrics such as accuracy may be affected, but AUC better reflects the model’s classification ability.

Experimental results

Experimental setup

In our experiments, the dataset of 798 subject MRI images was divided into two subsets: training and testing, with 75% for training and 25% for testing. Since each subject only retains one MRI image, there is no data leakage issue, ensuring the validity of the experiments. Additionally, we utilized the MONAI library (https://monai.io/) for data augmentation. This involved methods such as CenterSpatialCrop, RandSpatialCrop, Resize for cropping and resizing images, NormalizeIntensity for intensity normalization, and RandFlip and RandRotate90 for flipping and rotating images.

In the experiments, we utilized the pretrained weights of the tiny version of Video Swin Transformer provided by the official sources as initial weights, retaining only the matching weights. For unmatched weights, we applied the default initialization weight strategy. The experiments were conducted using a GPU model 3080. Due to GPU memory constraints, the batch size was set to 2. To achieve optimal performance, we conducted extensive experiments on hyperparameter selection. The optimizer chosen was AdamW32, with a learning rate of 0.000005 and weight decay set to 0.1. For the learning rate scheduler, we employed CosineAnnealingWarmRestarts. With these configurations, the loss and accuracy curves for the model proposed for distinguishing between AD and CN subjects are depicted in Fig. 6.

Diagnosis accuracy

Figure 6 illustrates the training progress of the classification tasks involving AD and CN subjects within this investigation. It can be observed that the model tends to converge after 500 epochs of training, achieving an optimal accuracy of 92.92%. To validate the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed 3D-CNN-VST algorithm, based on the ADNI dataset used in this study, comparative experiments were conducted against algorithms proposed in recent years22,24,25,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, as shown in Table 2. It is worth noting that our experiments completely avoided data leakage, ensuring the reliability and authenticity of the results. Although the experimental results may not appear as impressive as those from studies with data leakage, the credibility and reliability of our experiments are guaranteed. From Table 2, it can be observed that for the classification task of AD and CN, the proposed model achieves superior performance in terms of accuracy and sensitivity compared to the methods proposed by other researchers in 2023 and 2024. The achieved accuracy is 92.92%, and the sensitivity is 95.41%, which fully demonstrates the advantages and contributions of our model in the field of computer-aided early diagnosis of AD.

We know that the size of the dataset used by each researcher may vary, The preprocessing techniques employed on the dataset might vary, the strategies for dataset partitioning may vary, and the hyperparameters selected during training may also differ. Simply conducting such comparative experiments may not be sufficient. To further validate the superiority of the proposed algorithm in this study, under the condition that the dataset, preprocessing pipeline, and experimental procedures are kept identical, we compared our proposed model with the state-of-the-art models in the visual domain for AD and CN classification tasks, including: 3D ResNet41, 3D ConvNext, 3D Swin Transformer, and Video Swin Transformer4. For ConvNext and 3D Swin Transformer, which are modifications based on the 2D visual domain ConvNext42 and Swin Transformer29, respectively. The comparative outcomes are presented in Table 3. As indicated within this table, the model we have introduced demonstrates superior efficacy across the quartet of evaluative criteria. Acc increased by 2.52%, Sen increased by 2.75%, Specificity (Spe) remained equal to the best values achieved by other models, and AUC increased by 2.63%. The ROC curves of our proposed model compared with the four benchmark models are depicted in Fig. 7, demonstrating that our model achieves the best classification performance.

We conducted a visual analysis of the model’s misclassifications. Table 4 presents the classification report of the model. The formulas for the three parameters in the classification report - precision, recall, and f1-score - are as follows.

Precision indicates the proportion of samples that truly belong to a class among all samples predicted by the model as that class. Recall represents the proportion of samples correctly identified by the model among all true positive samples. F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balance between these two metrics. In AD diagnosis, a high recall is more crucial as we aim to identify as many truly affected individuals as possible. Figure 8 shows the confusion matrix of the validation set, where the diagonal data represents correct predictions, and off-diagonal entries indicate misclassifications. The figure demonstrates that a large number of individuals were correctly classified, with only 14 misclassifications, indicating a high overall model accuracy. Table 4 further shows that the precision for AD is 0.94118 and for CN is 0.92035. However, analyzing the recall and misclassification patterns reveals that among the misclassified individuals, 9 AD cases were predicted as CN, while 5 CN cases were predicted as AD. The former is nearly twice the latter. This is also reflected in Table 4, where the recall for AD is 0.89888, and for CN is 0.95413, showing a 5% difference. Upon investigation, we found that this discrepancy is due to the imbalance in the proportion of AD to CN cases in our dataset. Our data comprises 360 AD cases and 438 CN cases. In future research, we plan to balance the ratio of AD to CN cases as much as possible and collect more MRI data to enhance the model’s performance.

Ablation

In antecedent studies pertaining to the precocious detection of AD, typical preprocessing steps for brain MRI include skull stripping, registration to a standard space, and segmentation. Smoothing is a common step in voxel-based morphometry (VBM) methods aimed at denoising, compensating for segmentation defects, and facilitating statistical analysis. However, the effectiveness of smoothing in MRI brain image preprocessing in the field of deep learning has not been thoroughly validated. To evaluate the impact of the smoothing operation on the model’s performance, we conducted comparative experiments. The experimental results are presented in Table 5. From the table, we can conclude that the smoothing operation has almost no effect on the model’s performance. Researchers can conduct their own comparative experiments to choose the optimal results.

In 2D image-based visual tasks, the plug-and-play CBAM module has been demonstrated to enhance model performance. However, the effectiveness of the 3D CBAM module in AD detection tasks based on 3D MRI remains to be validated. Therefore, in this task, we conducted experiments to verify the necessity of the 3D CBAM module. Through experimentation, we found that incorporating the 3D CBAM module after depthwise separable convolution to extract features is beneficial for accurate AD recognition. The empirical findings are delineated in Table 6. Examination of Table 6 indicates that incorporating the 3D CBAM module substantially enhances the precision of the model.

Visualization analysis

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed model in identifying AD and improve the interpretability of the model, we referred to the Grad-CAM method43 to visualize the focus points of the model. Since our model processes 3D MRI data, we performed slice-wise processing of the MRI data along the axial plane and extracted some of them for illustration, as shown in Fig. 9. By observing the visualization, we can find that the attention of our model is mainly concentrated on the parietal lobe, cerebral cortex, Broca’s area, and the medial temporal lobe. Further research by our team suggests that the parietal lobe is responsible for the processing of bodily sensations44, the Broca’s area is closely related to human speech and language45, and these regions may be associated with the onset of AD. The medial temporal lobe involves structures like the hippocampus and amygdala, which can affect memory and emotion processing, and their atrophy may even lead to AD46. These findings indicate that our model has a certain effect on the early diagnosis of AD. The visualized results provide insights into the key brain regions that the model focuses on, which aligns with the known pathological mechanisms of AD. This can help improve the interpretability and robustness of our AD identification model.

Computational analysis

In this subsection, we evaluated and compared the computational complexity of the model. We used the ptflops and torchinfo libraries in PyTorch to calculate the model’s floating point operations (FLOPs) and the number of parameters, which reflect the model’s computational requirements and memory usage. As shown in Table 7, there is a clear relationship between accuracy, model parameters, and FLOPs. Our model achieved the highest accuracy while maintaining significantly lower parameter count and FLOPs compared to the second-best model. This demonstrates that our model not only excels in accuracy but also offers a distinct advantage in computational efficiency.

Discussion

Currently, the trained model has achieved promising prediction results on the ADNI dataset. However, how to integrate the model into clinical practice and its impact on early AD diagnosis are important issues worth discussing for future work. To successfully implement the proposed model in clinical practice and achieve excellent diagnostic performance, we believe it is crucial to ensure seamless integration with existing medical imaging systems. Through automated preprocessing and analysis of patients’ 3D MRI images, the model can quickly generate classification results and present them to clinicians. This enables physicians to rapidly obtain diagnostic recommendations from the model, while also providing intuitive heatmaps that highlight the areas of interest identified by the model, further assisting clinical decision-making. The model is capable of capturing subtle pathological changes that are difficult for the human eye to detect, aiding physicians in their decision-making process. This not only improves diagnostic accuracy but also significantly reduces diagnosis time, alleviates the workload of doctors, and lowers healthcare costs for patients. While this is our envisioned outcome, achieving such results will require substantial time and resources. For instance, the cost of training the model is a significant factor, as we have only trained it on the ADNI dataset. To integrate the model into clinical practice, a much larger dataset will be required. Specifically, we would need to collect MRI data from AD and CN individuals across various age groups to enhance the model’s generalization and predictive capabilities.

To assess the generalization capability of our model, we conducted tests on the open-source dataset OASIS47. We collected 104 3D MRI images from 104 subjects, equally distributed between AD and CN (52 each). We directly applied our model, trained on the ADNI dataset, to test on the collected OASIS database. We then compared our results with those of current state-of-the-art models in the vision domain, as mentioned earlier. The results are presented in Table 8. As evident from the table, our model demonstrates superior generalization performance on the OASIS dataset, achieving an accuracy of 75.96%, significantly outperforming other models. Overall, the generalization ability of all models listed in the table appears limited. We attribute this to two main factors:

-

(1)

Insufficient training data volume. The ADNI dataset, with 798 MRI images, uses only 75% for training. This quantity is still relatively small, especially considering the complexity of 3D data, which makes feature generalization more challenging.

-

(2)

The difference between the ADNI and OASIS datasets. While ADNI contains MRI images specifically related to AD, OASIS includes images of patients with various forms of dementia. The pathological features represented in these MRI scans may differ slightly, potentially contributing to the suboptimal generalization results.

Despite these challenges, our model ultimately achieved an accuracy of 75.96%, significantly outperforming other models in terms of generalization. This demonstrates our model’s superior ability to capture AD-specific features. However, we also recognize the existing limitations. In the future, our team plans to collaborate with local hospitals, while ensuring patient privacy, to gather more MRI data for further training. Additionally, we plan to collect and incorporate MRI data containing artifacts and noise into our training process to enhance the model’s robustness. Another important aspect to consider is the computational complexity of the model. Improving the computational efficiency while maintaining model performance can further facilitate its clinical application. Therefore, we plan to continue our research in areas such as knowledge distillation and model pruning to optimize our model.

At the same time, we believe that ethical considerations must not be overlooked when using deep learning models for AD diagnosis, particularly regarding patient data privacy and the potential impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on clinical decision-making for AD diagnosis. In this study, as well as in our future research, protecting patient data privacy remains a core principle. All the MRI data we have used in this research have been anonymized to ensure that patients’ personal information cannot be traced. We will maintain this approach in our future research. AI-assisted diagnosis for AD offers considerable benefits, such as enhancing early detection and assisting clinicians in identifying subtle pathological changes that might be missed otherwise. However, the potential for adverse outcomes exists if AI is misused. It is crucial that physicians do not become overly dependent on AI, as this may compromise their decision-making independence. Clinicians should exercise discernment when using AI models, ensuring that the results are considered alongside other clinical assessments for a thorough evaluation. Additionally, as researchers, we must focus on improving the transparency and interpretability of AI models to support clinicians in making well-informed decisions.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a novel deep learning model, 3D-CNN-VSwinFormer, for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. In this model, a residual-based depthwise separable CNN combined with a 3D CBAM module is used to extract low-dimensional features from MRI data. The Video Swin Transformer progressively integrates local spatial features to obtain information about structural changes in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. For the first time, we applied the Video Swin Transformer to the field of 3D medical image diagnosis for AD, and integrated it with a custom 3D CNN, achieving satisfactory results.

From the perspective of the dataset utilized, we employed 3D MRI brain scans as input, with only one image per subject. This approach effectively circumvented data leakage, ensuring the authenticity and accuracy of the experiment. However, the use of 3D MRI datasets consequently extended the model training duration significantly. The inability to train using a 2D slice approach inherently limited the size of our dataset, as evidenced by our use of merely 798 3D MRI images. Despite this, we achieved remarkably accurate AD detection results, which attests to the exceptional performance of our highlighted model. Looking ahead, our work will focus on two key areas:

Expanding the dataset: By acquiring more diverse 3D MRI data, we aim to address the current limitations in data volume and variety. This expansion will likely lead to improved model robustness and generalization across different populations and imaging protocols.

Longitudinal analysis: We will investigate techniques to effectively incorporate temporal information from sequential MRI scans. This approach could potentially reveal subtle changes in brain structure over time, offering insights into the progression of AD and enhancing our model’s predictive capabilities.

Data availability

The raw data used in the current study are all available from the ADNI dataset, http://adni.loni.usc.edu, and OASIS dataset, https://sites.wustl.edu/oasisbrains/.

References

Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 19, 1598–1695. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13016 (2023).

Poulakis, K. et al. Stage vs subtype hypothesis: A longitudinal MRI study investigating the heterogeneity in AD: neuroimaging/optimal neuroimaging measures for tracking disease progression. Alzheimer’s Dement. 16. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.042907 (2020).

Fathi, S., Ahmadi, M. & Dehnad, A. Early diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease based on deep learning: A systematic review. Comput. Biol. Med. 146, 105634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105634 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Video swin transformer. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 3202–3211. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.13230 (2022).

Visser, P. J. et al. Medial Temporal lobe atrophy predicts alzheimer’s disease in patients with minor cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 72, 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.72.4.491 (2002).

Magnin, B. et al. Support vector machine-based classification of alzheimer’s disease from whole-brain anatomical MRI. Neuroradiology 51, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-008-0463-x (2009).

Ahmed, B. Classification of alzheimer’s disease subjects from MRI using hippocampal visual features. Multimedia Tools Appl. 74, 1249–1266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-014-2123-y (2015).

Zhou, Q. et al. An optimal decisional space for the classification of alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 61, 2245–2253. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2014.2310709 (2014).

Chupin, M. et al. Fully automatic hippocampus segmentation and classification in alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment applied on data from ADNI. Hippocampus 19, 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20626 (2009).

Liu, S. et al. Multimodal neuroimaging feature learning for multiclass diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 62, 1132–1140. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2014.2372011 (2014).

Palmqvist, S. et al. Discriminative accuracy of plasma phospho-tau217 for alzheimer disease vs other neurodegenerative disorders. Jama 324, 772–781 (2020).

Lee, M. et al. A method for diagnosing alzheimer’s disease based on salivary amyloid-β protein 42 levels. J. Alzheimers Dis. 55, 1175–1182 (2017).

Klöppel, S. et al. Automatic classification of MR scans in alzheimer’s disease. Brain 131, 681–689. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awm319 (2008).

Peng, J. et al. Structured sparsity regularized multiple kernel learning for alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Pattern Recogn. 88, 370–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2018.11.027 (2019).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv: 2010.11929. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929 (2020).

Yagis, E. et al. Effect of data leakage in brain MRI classification using 2D convolutional neural networks. Sci. Rep. 11, 22544. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01681-w (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Alzheimer’s disease detection using depthwise separable convolutional neural networks. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 203, 106032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.106032 (2021).

Salehi, A. W. A CNN model: earlier diagnosis and classification of Alzheimer disease using MRI. International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC). 156–161. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICOSEC49089.2020.9215402 (IEEE, 2020).

Jain, R. et al. Convolutional neural network based alzheimer’s disease classification from magnetic resonance brain images. Cogn. Syst. Res. 57, 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsys.2018.12.015 (2019).

Farooq, A. et al. A deep CNN based multi-class classification of Alzheimer’s disease using MRI. in IEEE International Conference on Imaging systems and techniques (IST). 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/IST.2017.8261460 (IEEE, 2017).

Ramzan, F. et al. A deep learning approach for automated diagnosis and multi-class classification of alzheimer’s disease stages using resting-state fMRI and residual neural networks. J. Med. Syst. 44, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-019-1475-2 (2020).

Chen, L., Qiao, H. & Zhu, F. Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis with brain structural mri using multiview-slice attention and 3D Convolution neural network. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 871706. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.871706 (2022).

Li, C. Trans-resnet: Integrating transformers and cnns for alzheimer’s disease classification. in IEEE 19th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISBI52829.2022.9761549 (IEEE, 2022).

Liu, Y. et al. An unsupervised learning approach to diagnosing alzheimer’s disease using brain magnetic resonance imaging scans. Int. J. Med. Informatics. 173, 105027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105027 (2023).

Lu, B. et al. A practical alzheimer’s disease classifier via brain imaging-based deep learning on 85,721 samples. J. Big Data. 9, 101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-022-00650-y (2022).

Woo, S. et al. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. in Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 3–19. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1807.06521 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 11534–11542. https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_CVPR_2020/papers/Wang_ECA-Net_Efficient_Channel_Attention_for_Deep_Convolutional_Neural_Networks_CVPR_2020_paper.pdf (2020).

Song, C. H., Han, H. J. & Avrithis, Y. All the attention you need: Global-local, spatial-channel attention for image retrieval. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision. 2754–2763. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2107.08000 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proc. IEEE/CVF Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 10012-10022 https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.14030 (2021).

Hu, Z. et al. Conv-Swinformer: integration of CNN and shift window attention for alzheimer’s disease classification. Comput. Biol. Med. 164, 107304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107304 (2023).

Smith, S. M. et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23, S208–S219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051 (2004).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1711.05101. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1711.05101 (2017).

Liu, M. et al. A multi-model deep convolutional neural network for automatic hippocampus segmentation and classification in alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 208, 116459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116459 (2020).

Zhu, W. et al. Dual attention multi-instance deep learning for alzheimer’s disease diagnosis with structural MRI. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 40, 2354–2366. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2021.3077079 (2021).

Xing, X. Advit: Vision transformer on multi-modality pet images for alzheimer disease diagnosis. in IEEE 19th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI). 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISBI52829.2022.9761584 (IEEE, 2022).

Asgharzadeh-Bonab, A., Kalbkhani, H. & Azarfardian, S. An alzheimer’s disease classification method using fusion of features from brain magnetic resonance image transforms and deep convolutional networks. Healthc. Analytics. 4, 100223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.health.2023.100223 (2023).

Diogo, V. Early diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease using machine learning: a multi-diagnostic, generalizable approach. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 14, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-022-01047-y (2022).

Duan, Y., Wang, R. & Li, Y. Aux-vit: classification of Alzheimer’s disease from mri based on vision transformer with auxiliary branch. in 5th International Conference on Communications, Information System and Computer Engineering (CISCE). 382–386. https://doi.org/10.1109/CISCE58541.2023.10142358 (IEEE, 2023).

Lozupone, G. et al. AXIAL: Attention-based eXplainability for Interpretable Alzheimer’s Localized Diagnosis using 2D CNNs on 3D MRI brain scans. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.02418. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.02418 (2024).

Atalar, A., Adar, N., Savaş & Okyay A novel fusion method of 3D MRI and test results through deep learning for the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Preprint at medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.15.24312032 (2024).

Chen, S., Ma, K. & Zheng, Y. Med3d: Transfer learning for 3d medical image analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1904.00625. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1904.00625 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. A convnet for the 2020s. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 11976–11986. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.03545 (2022).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-019-01228-7 (2015).

Fogassi, L. et al. Parietal lobe: From action organization to intention Understanding. Science 308, 5722, 662–667. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1106138 (2005).

Flinker, A. et al. Redefining the role of Broca’s area in speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2871–2875. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414491112 (2015).

Visser, P. J. et al. Medial Temporal lobe atrophy predicts alzheimer’s disease in patients with minor cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 72 (4), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.72.4.491 (2002).

Marcus, D. S. et al. Open access series of imaging studies: longitudinal MRI data in nondemented and demented older adults. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 12, 2677–2684. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21407 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). Data were provided by OASIS [OASIS-2: Longitudinal: Principal Investigators: D. Marcus, R, Buckner, J. Csernansky, J. Morris; P50 AG05681, P01 AG03991, P01 AG026276, R01 AG021910, P20 MH071616, U24 RR021382].This work is supported by the Jiangxi Provincial natural science fund (No. 20232BAB202025, 20232BAB202022 and 20204BCJL23035).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H. and H.L. collected MRI image data. R.T. and W.Z. preprocessed MRI data. X.L. made the outline. Y.W. and J.Z. conducted experiments and completed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., Wei, Y., Li, X. et al. A deep learning model for early diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease combined with 3D CNN and video Swin transformer. Sci Rep 15, 23311 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05568-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05568-y