Abstract

This paper presents a highly optimized metal-insulator-metal (MIM) filter designed for لrefractive index sensing applications, with dual cut-off bands at 1008 nm and 1348 nm. The filter’s dimensions are optimized using the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm, ensuring maximum sensitivity and miniaturization. The Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) method is employed for simulations, while the Drude-Debye model accurately captures the dispersive dielectric properties of the metallic layers. Also, the optimized sensor exhibits high sensitivity, with values of 7504 nm/RIU for the first cut-off band and 8000 nm/RIU for the second, demonstrating enhanced responsiveness in the longer-wavelength range. The figure of merit (FOM) values of 250.13 (1/RIU) and 250 (1/RIU) for the two cut-off bands, respectively, along with detection limits of 0.0039 RIU and 0.004 RIU, further highlight the sensor’s precision and reliability in detecting small refractive index changes. Furthermore, this dual-band MIM filter is well-suited for real-time refractive index detection, providing a compact, efficient design with excellent filtering capabilities. The integration of the PSO algorithm ensures optimal performance across both wavelength bands, making the sensor a promising candidate for applications in biosensing, chemical detection, and environmental monitoring. The high sensitivity, combined with the dual-band functionality, enables versatile sensing applications with enhanced precision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plasmonic is a rapidly evolving field that explores the interaction between electromagnetic waves and free electrons at the interface of metallic and dielectric materials. This interaction gives rise to surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs), which are collective oscillations of electrons that propagate along metal-dielectric boundaries. These unique optical phenomena enable subwavelength confinement of light, making plasmonic structures highly attractive for various applications, including sensing, imaging, and optical communication1,2,3.

Among different plasmonic configurations, MIM waveguides have gained significant attention due to their ability to efficiently confine and guide SPPs over long propagation distances. An MIM waveguide consists of a thin dielectric layer sandwiched between two metal layers, which supports strong field confinement and enables high-sensitivity sensing. This feature is particularly useful in refractive index (RI) sensing, where small variations in the surrounding medium’s RI lead to measurable shifts in resonant wavelengths4,5,6.

RI sensors based on MIM structures have become crucial tools in various applications, including biosensing, chemical detection, and environmental monitoring. These sensors exploit SPPs to confine electromagnetic fields at the metal-dielectric interface, which results in high sensitivity to RI changes in the surrounding medium. However, designing such sensors requires addressing several challenges, including maximizing sensitivity, enhancing transmission efficiency, and reducing optical losses. Achieving these improvements requires careful tuning of sensor dimensions and optimization of the quality factor (Q-factor), as these factors directly influence sensor performance across different applications.

Several studies have explored different aspects of MIM-based RI sensors. For biosensing applications, Ebbesen et al.7 investigated the extraordinary optical transmission of subwavelength hole arrays, laying the groundwork for plasmonic sensor designs. Barnes et al.8 expanded on this concept by examining surface plasmon subwavelength optics, emphasizing how MIM structures enhance biomolecular detection. In contrast, Zonouri et al.9 developed a dual-mode graphene-based optical sensor specifically tailored for cancer cell detection, demonstrating the potential of advanced plasmonic designs in medical diagnostics.

In the field of chemical detection, Libon et al.10 introduced an optically controllable terahertz filter, showcasing how MIM structures can be adapted for real-time chemical sensing. These findings were further supported by studies such as Butt et al.11, who proposed a plasmonic MIM waveguide sensor optimized for improved sensing performance in detecting temperature.

The sensitivity of MIM-based sensors is typically defined as the wavelength shift per unit change in RI (measured in nm/RIU). Enhancing this sensitivity is vital for detecting even small variations in the RI, which is particularly important in biological sensing and chemical analysis. Previous studies have focused on increasing the sensitivity by introducing different metal-dielectric combinations, optimizing layer thickness, and utilizing stubs or resonators. For instance, Ref.12 demonstrated that a properly tuned MIM sensor could achieve high sensitivity by carefully optimizing the metal layer thickness and dielectric material properties. Similarly, Ref13. showed that the use of multi-resonant structures could further enhance the sensitivity by providing multiple sensing bands in the visible and infrared spectrum.

A waveguide-based H-shaped plasmonic RI sensor using a MIM waveguide configuration is introduced in14 for sensing interactions. The structure’s performance was evaluated using the finite element method (FEM), and the sensor detects RI changes by monitoring shifts in resonant wavelengths. The plasmonic structure facilitates light interaction, and variations in the environment’s RI directly influence the resonant wavelength. While the sensor shows potential for applications like blood glucose monitoring, it suffers from bulky design and slower transmission rates.

Also, other cavity models, such as T-shaped, L-shaped, ring resonator-based, square-shaped, slot cavity, asymmetric cavity, and coupled resonator cavities, have also been explored for optimizing sensitivity, compactness, and transmission efficiency4,15.

Furthermore, the physical dimensions of the MIM sensor—such as the length, width, and thickness of the metal and dielectric layers—play a significant role in defining its optical characteristics. Researchers have employed various methods to optimize these dimensions. Ref16. utilized parametric sweeps to manually explore the design space, identifying the best dimensions for maximizing sensitivity in a dual-band MIM structure. However, this trial-and-error approach, while effective, can be time-consuming and does not guarantee an optimal solution. More advanced approaches, such as evolutionary algorithms, have also been explored. In17, a genetic algorithm was used to optimize the dimensions of the MIM sensor, and the obtained results showed that such methods can significantly reduce the design time and at the same time improve the performance. Despite these advances, these optimization techniques often struggle with the highly non-linear and multi-modal nature of the design space, necessitating further exploration of efficient and robust optimization methods.

Optimization techniques such as simulated annealing, genetic algorithms (GA), and gradient-based methods have been employed in the past to fine-tune MIM sensor designs. However, each of these methods has limitations. GAs can efficiently explore large design spaces but often suffer from convergence issues, particularly in high-dimensional spaces. Simulated annealing, on the other hand, is more effective for escaping local minima but can be slow and inefficient for larger design problems. Gradient-based methods, while faster, often fail to find global optima in non-linear, highly complex systems like MIM structures18,19.

One recent method that has shown promise for sensor optimization is PSO, a population-based algorithm that is highly effective in finding global optima for non-linear and multi-modal problems. PSO, inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking, uses particles (potential solutions) to explore the search space and iteratively improve their positions based on both individual and group experiences. In20, PSO has been used to optimize photonic crystal sensor designs and significant improvements in sensitivity and transmission efficiency have been achieved. However, few studies have applied PSO specifically to MIM sensor design, highlighting an opportunity for innovation.

A new methodical strategy is presented in21, providing a quick cut to reducing human involvement and difficulties in photonic crystal waveguide design. An optimization issue is used to frame the photonic crystal waveguide design process in this technique. With the help of an optimization technique, the best design for the provided photonic crystal waveguide is then automatically determined. Several constraints are used during optimization to make sure the optimized structure doesn’t break any laws of physics. To prove that this strategy works, a case study is tailored for the structure of a slotted Bragg corrugated photonic crystal waveguide.

The quality factor (Q-factor) is another critical parameter in MIM sensors, representing the sharpness of the resonances and the sensor’s ability to distinguish small RI changes. A high Q-factor typically correlates with enhanced sensitivity and improved performance. However, achieving a high Q-factor in MIM sensors can be challenging due to intrinsic losses in the metal layers, especially in noble metals like silver and gold22,23. Ref. [24] demonstrates that incorporating dielectric multilayers or altering the geometry of the metal layer can enhance the Q-factor while preserving a high transmission rate. However, achieving an optimal balance between the Q-factor and sensor sensitivity is a complex task, requiring precise control of the sensor’s dimensions and material properties.

Recent advancements in MIM-based refractive index sensors have explored various design strategies to enhance sensitivity, quality factor, and detection precision. Studies have demonstrated that incorporating multi-slot structures, hybrid plasmonic-photonic designs, and optimized waveguide geometries can significantly improve SPP confinement and resonance sharpness. For instance, slot-based MIM waveguide configurations have been shown to increase modal overlap with the analyte, resulting in enhanced RI sensitivity25. Similarly, photonic crystal-assisted MIM sensors have been employed to achieve a high-quality factor through photonic bandgap engineering, leading to sharper resonance shifts26. Another study introduced a dual-band MIM sensor with nanostructured resonators, demonstrating the feasibility of multi-wavelength RI detection in plasmonic sensing applications27. Additionally, investigations into dielectric tuning and multilayer MIM sensors have provided insights into optimizing plasmonic mode dispersion and reducing propagation losses, further enhancing sensor performance28. These developments underscore the importance of precision-engineered MIM structures in next-generation plasmonic sensing.

Table 1 provides a comparison of several recent studies that focused on sensitivity enhancement, dimensional optimization, and size improvement in MIM sensors. Each study presents different optimization approaches and outcomes in terms of sensitivity, size, and computational efficiency.

While various studies have explored optimization methods for enhancing MIM sensor performance, significant gaps remain. Most previous studies have focused on traditional optimization techniques such as parametric sweeps or genetic algorithms, which, while effective, are either time-consuming or prone to convergence issues. Furthermore, very few works have applied PSO to MIM structures, despite its demonstrated success in other optical sensor designs.

In this paper, we address the current gaps by employing PSO to optimize the dimensions of a dual-band MIM sensor structure, focusing on maximizing sensitivity and the quality factor. The sensor’s dimensions are compact, with a size of only 200 nm × 420 nm, and incorporate new stubs and geometry to enhance performance. Through automated dimensional optimization and an FDTD simulation-based feedback loop, we achieved sensitivity exceeding 7504 nm/RIU and 8000 nm/RIU, representing a significant improvement in transmission and RI sensitivity compared to previous designs. This approach offers a novel, efficient, and robust optimization method applicable to a wide range of sensing applications.

Design of the MIM sensor

In this study, the FDTD method was initially employed to analyze how variations in the RI affected the transmission rate of the waveguide. Following this, the geometrical characteristics of the structure were adjusted to assess their influence on the filter’s performance. The contribution of the SPP depth was minimal in the overall results. Note that a three-dimensional (3D) model is reduced to a two-dimensional (2D) one, as both models yield similar results in simulations and experiments1. This simplification allows us to neglect the effect of the device’s height on the obtained results by assuming an infinite height. Additionally, the 2D approach significantly reduces simulation time and computational resource requirements without sacrificing calculation accuracy15,29,30.

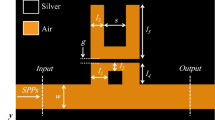

Figure 1 demonstrates the filter design, which consists of silver metal and air as the insulating material. This figure depicts a symmetric structure along the centerline, featuring a MIM waveguide with two newly designed stubs, each containing two internal holes. Additionally, a small vertical stub is positioned in the middle. The holes are symmetrically placed within each stub, maintaining equal spacing in both stubs for balanced design.

The internal air holes serve multiple key functions in enhancing the optical response of the system. First, they modify the local RI, which results in improved mode confinement and field enhancement at the metal-dielectric interface. This leads to a stronger localization of SPPs, enhancing the resonance properties of the structure. Second, the presence of air holes influences phase-matching conditions, allowing precise tuning of the cutoff and passband wavelengths. By adjusting the diameter and positioning of these holes, the resonance characteristics can be optimized to achieve a sharper spectral response. Additionally, the air holes contribute to reducing propagation losses by introducing regions of lower refractive index, which help confine the optical field more effectively within the dielectric layer, thereby improving overall transmission efficiency. Furthermore, these air holes enhance the coupling efficiency between incident light and SPP modes, which leads to improved quality factor and more distinct resonance dips in the transmission spectrum.

Ө in this design has an opening angle of 135°, which determines the field distribution and resonance behavior. A larger angle results in broader spectral features, while a smaller angle leads to sharper resonance dips and improved wavelength selectivity. The chosen 135° angle ensures a balance between high sensitivity and efficient filtering, making the sensor highly effective for real-time refractive index detection.

These carefully engineered design features significantly enhance the performance of the MIM sensor, providing a compact, highly sensitive structure that is well-suited for biosensing and chemical detection applications.

The various dimensions, such as the length of the stubs (L1, L3, L4) and widths (W1, W2, and L2), are labeled in the diagram. Pin and Pout represent the input and output power, respectively, of the waveguide. The ratio of Pout/Pin determines the transmission efficiency of the structure (\(\:T=\frac{{P}_{out}}{{P}_{in}}\)). This design was simulated using Ansys Lumerical FDTD solver (version 2024 R1) under Perfectly Matched Layer (PML) boundary conditions and a 1 nm mesh size. This software version was selected due to its advanced meshing capabilities, accurate Drude- Debye material modeling, and efficient computational resource management, which are critical for analyzing plasmonic waveguide-based sensors. The fine meshing ensures precise calculation of light propagation and interaction with the structure, optimizing the transmission characteristics for sensor applications.

The FDTD method was used to simulate the optical response of the proposed MIM-based RI sensor. FDTD is a widely used computational technique for solving Maxwell’s equations in both time and space domains, enabling accurate modeling of electromagnetic wave interactions with structured materials. The fundamental governing equations used in the FDTD method are derived from Maxwell’s curl Eqs.30,31,32:

where D is the electric displacement field, H is the magnetic field, B is the magnetic flux density, E is the electric field, and J is the current density. These equations are discretized using Yee’s algorithm, which applies central finite differences in both time and space to iteratively solve the fields over the simulation domain.

SPPs are a specific type of TM mode that arise from the interaction between electromagnetic waves and electrons at the metal-dielectric interface, even when no metal is present at the boundary. SPPs propagate along the interface, with their electric and magnetic fields aligned according to the TM mode. This characteristic allows SPPs to concentrate electromagnetic fields on a sub-wavelength scale at the interface, a crucial feature for photonic circuits and sensors. In contrast, TE modes cannot generate such localized field fluctuations, making the TM mode central to our focus on SPP dispersion33.

In a vacuum, the wave vector \(\:{k}_{0}\) is equal to 2π/λ0, \(\:{\alpha\:}_{c}^{2}\) is equal to \(\:{k}_{0}^{2}\)(εin − εm)+ \(\:{k}^{2}\), and p is equal to εin/εm. The permittivity of the insulator is represented by εin, whereas the permittivity of the metal is denoted by εm.

A broadband plane-wave source with a wavelength range of 600–1800 nm was used to excite the stubs. The incident light was coupled into the MIM waveguide sensor using an edge coupling mechanism, where the waveguide is directly excited at its input facet. This method is widely used in plasmonic waveguide structures, as it efficiently transfers energy into the system with minimal insertion loss. Additionally, other coupling techniques, such as grating couplers and tapered fiber coupling, have been explored in previous studies to enhance coupling efficiency in plasmonic waveguides5,11. The transmission rate, which is defined as the ratio of the structure’s output power to its input power, was evaluated at the output facet of the waveguide.

To ensure accurate simulation conditions, perfectly matched layers were applied as boundary conditions on all sides of the computational domain, effectively eliminating artificial reflections. The light entering the system was TM polarized, as this is the only mode capable of exciting SPPs in the MIM waveguide configuration. The simulations were performed at a constant temperature of 300 K, ensuring consistency in material properties. These settings allow for a precise evaluation of the sensor’s optical response, ensuring that key physical phenomena, such as plasmonic wave propagation and resonance shifts, are accurately captured while maintaining computational efficiency.

The performance of MIM waveguides is highly dependent on the width of the dielectric layer. This parameter plays a critical role in determining the waveguide’s mode support and propagation characteristics. The dielectric layer width (h) directly influences whether the structure can support TM modes while suppressing or eliminating TE modes. For instance, at an optimized width of approximately 50 nm, TM mode propagation can be enhanced, while TE modes can be minimized, improving the waveguide’s overall efficiency and functionality8,9,10,11.

Nanostructured silver is an ideal material for the next generation of plasmonic waveguides due to its exceptional optical properties. It offers high-quality imaging, excellent optical waveguiding, nanoscale beam confinement, and low propagation losses. To calculate silver’s relative permittivity, we used the Drude-Debye model, which considers the frequency-dependent dielectric constant of metals. For comparison, air is assumed to have a permittivity of 1. This model helps in accurately determining silver’s optical behavior and its suitability for nanoscale applications34,35.

A relative permittivity of 3.8344 is associated with infinite frequencies \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{\infty\:}\).A relaxation period (τ) of 7.4 × 10− 15 seconds and a static dielectric coefficient (\(\:{\epsilon\:}_{s}\)) of -9530.5 are given. Moreover, the angular frequency (\(\:\omega\:\)) is 1.38 × 1016 rad/s, and the conductivity is 1.1486 × 107 s/m.

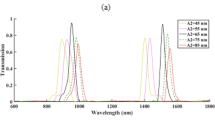

Figure 2 showcases the transmission rate as a function of wavelength for a dual cut-off band MIM filter under various structural modifications. The black curve in each graph represents the most ideal response, where the filter achieves high transmission in the passband (regions with minimal signal attenuation) and near-zero transmission in the cutoff band (regions where the signal is strongly attenuated).

Figure 2a demonstrates the impact of stub width (W1) on the transmission spectrum. As W1 increases from 40 nm to 70 nm, the cutoff wavelengths and transmission profile shift accordingly. At W1 = 60 nm (black curve), the filter operates most effectively, with sharp cutoffs at approximately 1008 nm and 1348 nm. At these cutoff points, the transmission drops to near-zero, effectively filtering the undesired signals. The black curve also shows the highest transmission in the passband, indicating that W1 = 60 nm is the most efficient design. On the other hand, Fig. 2b illustrates the influence of stub length (L1) on the transmission characteristics of the filter. As L1 increases from 150 nm to 180 nm, the cutoff bands shift accordingly. This configuration also shows the highest transmission in the passband with minimal signal loss, indicating that L1 = 160 nm provides the most precise filtering and strong suppression in the stopband. As the length of the stubs increases, the resonance wavelengths generated become shorter. This demonstrates a clear inverse relationship between stub length and the resonance wavelength, meaning longer stubs result in lower resonance wavelengths.

The results in Fig. 2c illustrate the effect of varying the L2/L3 ratio on the transmission spectrum. This ratio influences the overall structure geometry and the spacing between the stubs. As the L2/L3 ratio increases from 0.8 to 1.4, both the cutoff wavelengths and transmission efficiency change. While increasing the ratio leads to longer resonance wavelengths, further increases eventually degrade the filter’s performance. The optimal result is achieved when L2/L3 = 1.2 (black curve), where the cutoff wavelengths are sharp and the transmission is most efficient.

The final diagram (Fig. 2d) explores the influence of hole diameter on the transmission rate. As the diameter increases from 10 nm to 17.5 nm, the filter’s performance changes, primarily in the cutoff and bandpass wavelengths. The optimal result occurs at d = 12.5 nm, with well-defined cutoffs near 1008 nm and 1348 nm. Notably, unlike other figures, there are no significant changes in the resonance wavelengths; only the transmission rate is affected, while the resonance wavelengths remain nearly constant throughout.

To ensure a consistent and controlled evaluation of the effect of each geometric parameter, all simulations were conducted under the same conditions, with only one parameter varied at a time. This approach allows for an accurate assessment of how W1, L1, L2/L3, and d individually influence the transmission spectrum, without interference from other structural variations. The fixed values for each case, as detailed in Fig. 2, ensure that the observed changes in transmission characteristics are solely attributed to the parameter being optimized.

Simulation results of the transmission rate for different geometric parameters: (a) W1, (b) L1, (c) L2/L3, and (d) d. In (a), the parameters are L1 = 160 nm, L2/L3 = 1.2, and d = 12.5 nm; in (b), W1 = 60 nm, L2/L3 = 1.2, and d = 12.5 nm; in (c), W1 = 60 nm, L1 = 160 nm, and d = 12.5 nm; and in (d), L1 = 160 nm, L2/L3 = 1.2, and W1 = 60 nm.

The chosen cavity shape is designed to enhance light confinement, transmission efficiency, and sensing performance in the MIM-based plasmonic RI sensor. The dual-stub structure with internal holes improves the interaction between SPPs and the surrounding medium, leading to higher sensitivity to refractive index variations. The vertical stub (L3) in the middle of the waveguide serves as a mode filter, optimizing the coupling efficiency and reducing unwanted reflections. Additionally, the presence of symmetrically placed holes helps control the dispersion characteristics of the SPPs, ensuring a sharp and well-defined transmission spectrum. This geometry facilitates dual-band sensing, allowing the device to operate effectively at 1008 nm and 1348 nm, making it suitable for applications such as biosensing, chemical detection, and environmental monitoring.

To analyze the influence of the angle (θ) on the transmission properties of the proposed plasmonic filter, simulations were performed at different θ values. The results, presented in Fig. 3, illustrate how variations in the angle affect the passband transmission efficiency and cutoff band suppression.

The transmission characteristics exhibit the following key trends:

Passband and Cutoff Band Behavior:

-

At smaller fan angles (e.g., 90° and 105°), the passband transmission remains relatively low, and the cutoff band does not reach complete attenuation, resulting in suboptimal filtering.

-

As θ increases beyond 120°, the transmission within the passband improves, while the cutoff band achieves stronger suppression, leading to a more distinct filtering effect.

Optimal Stub Angle at 135°:

-

The best performance is achieved at θ = 135°, where the passband transmission is maximized (close to 1), and the cutoff band reaches near-zero transmission.

-

This ensures high filtering efficiency, allowing strong signal propagation within the desired spectral bands while effectively blocking unwanted frequencies.

Degradation at Higher Angles (> 135°):

-

When θ increases beyond 135° (e.g., 150°), the resonance dips become broader, leading to reduced spectral selectivity.

-

This behavior indicates that excessive widening of the fan angle results in weaker mode confinement, thereby compromising filtering precision.

Based on these findings, the optimal fan resonator angle is determined to be 135°, ensuring maximum passband transmission, strong resonance definition, and effective suppression of unwanted spectral components. This selection significantly enhances the filter’s overall performance in dual-band refractive index sensing applications, providing high sensitivity, precision, and reliability.

Although the initial values for the filter’s dimensions (stub width, length, hole diameter, etc.) show promising performance, they are not fully optimized for the best possible filter and sensor efficiency. Manual tuning of these parameters provides useful insights, but it lacks the precision and thoroughness required for optimal results. In order to achieve the highest transmission efficiency and sharp cutoffs with minimal signal loss, the dimensions need to be calculated using a more advanced method. The PSO algorithm is therefore employed to systematically determine the ideal dimensions, ensuring maximum filter and sensor performance. PSO is particularly suited for this task as it explores the entire design space efficiently and converges on the most optimal solution.

Optimization of filter dimensions

Particle swarm optimization is a computational algorithm inspired by the social behavior of birds flocking or fish schooling. It is an iterative optimization technique that explores a large search space by using a population of potential solutions, called “particles,” to find the optimal result for a given problem. Each particle adjusts its position in the search space based on its previous experience and the experiences of neighboring particles36.

The objective function for the PSO algorithm in this case is designed to optimize the transmission characteristics of the MIM filter. The algorithm seeks to maximize the transmission rate in the passband and minimize the transmission rate (close to zero) in the cutoff bands, ensuring efficient filtering performance.

The objective function \(\:f\left(X\right)\) is defined as:

Where, \(\:T\left(\lambda\:\right)\) is the transmission rate at wavelength λ, \(\:{\lambda\:}_{passband}\) represents the wavelengths in the passband where transmission should be maximized, \(\:{\lambda\:}_{cutoff}\) represents the wavelengths in the cutoff band where transmission should be minimized.

The PSO algorithm is a robust method for addressing complex, non-linear optimization challenges. Each particle within the swarm maintains two types of memory: one stores the particle’s best position, while the other helps guide its next movement. During each iteration, the global best and local best solutions are used to update the particle’s velocity and position. The particle’s new location is determined by adding its updated velocity to its current position, facilitating efficient exploration of the solution space37,38.

Where \(\:{X}_{j}\left(i\right)\) denotes particle j’s location, \(\:{V}_{j}\left(i\right)\) denotes particle j’s velocity, and i is the number of repetitions of the velocity variable. The following equation may be used to find the speed:

Based on Ref.39, parameters \(\:{c}_{1}\) and \(\:{c}_{2}\) reflect individual and group learning components, \(\:{r}_{1}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}\) are uniformly distributed random values in the interval (0,1), and \(\:{V}_{j}\left(i\right)\) represents the i-th component of particle j’s velocity.

Both the global best position (\(\:{G}_{best}\)) and the particle’s local best position (\(\:{P}_{best,j}\)) are communicated. The inertial weight θ(i) is employed in controlled laboratory studies to modify the particle’s velocity. The value of θ(i) can -be determined using the formula provided in40.

The minimum number of iterations in the PSO algorithm is represented by \(\:{\theta\:}_{min}\), while the maximum is denoted by \(\:{\theta\:}_{max}\). These values also correlate with the inertia weights, which play a crucial role in determining the balance between exploration and exploitation during optimization. Based on the design requirements of the MIM sensor, the inertia weights must be tuned to ensure efficient convergence. Experimental studies commonly suggest optimal values of \(\:{\theta\:}_{min}=0.4\) and \(\:{\theta\:}_{max}=0.7\) for achieving precise dimensional optimization, enhancing both transmission efficiency and cutoff sharpness40.

The design characteristics for this MIM sensor were tuned using the PSO algorithm, with specific values tailored to the proposed structure. A population size of 100 particles was used, with inertia weights of \(\:{\theta\:}_{max}=0.7\:\)and \(\:{\theta\:}_{min}=0.4\), allowing for an effective balance between exploration and convergence. The optimization process was capped at 500 iterations, ensuring sufficient exploration of the design space. The acceleration constants \(\:{c}_{1}\) and \(\:{c}_{2}\), both set to 2, were chosen to maintain a balance between the particles’ personal and global best positions.

The flowchart presented in Fig. 4 illustrates the process of optimizing the MIM sensor’s design using the PSO algorithm with simultaneous MATLAB and Lumerical FDTD co-simulation. Initially, the PSO parameters such as population size, inertia weights, and acceleration constants are defined. For each particle in the population, the dimensions are simulated in Lumerical’s FDTD module to calculate the transmission spectrum. MATLAB then evaluates the objective function, aiming to maximize transmission in the passband and minimize it in the cutoff band. The process iteratively updates the particles’ positions until optimal convergence is reached.

The final optimized dimensions of the filter, determined through the PSO algorithm, are provided in Table 2.

Figure 5 presents a comparison between the transmission rates of the filter with its initial dimensions and the optimized dimensions. As expected, the structure with optimized dimensions demonstrates significantly higher transmission in the passband, while the transmission is nearly zero at the cutoff wavelengths, which is ideal for effective filtering. The optimization process clearly enhances the performance of the designed filter, leading to superior transmission efficiency and sharper cutoff behavior.

Figures 6a to c illustrate the field profile of the magnetic field component ∣Hz∣ at three different wavelengths: 750 nm, 1008 nm, and 1600 nm. These figures represent the field distribution of the proposed filter, with two passing wavelengths and one cutoff wavelength.

-

Figure 6a (750 nm, passband): This shows a wavelength in the passband, where the filter allows strong transmission, as indicated by the red and yellow regions representing the high field intensity through the structure.

-

Figure 6b (1008 nm, cutoff band): This figure shows the field distribution at a cutoff wavelength. The stubs in the structure play a significant role here by effectively blocking transmission. The low field intensity (blue areas) indicates strong suppression of the signal, reflecting the filter’s ability to minimize unwanted transmission.

-

Figure 6c (1600 nm, passband): This figure also represents a passband wavelength, where the sensor again exhibits strong transmission. The field profile shows high-intensity regions near the center, demonstrating effective propagation through the structure.

The stubs are crucial at the cutoff wavelengths, as they enhance the filter’s ability to block signals, making the design highly efficient for dual-band applications.

Results, applications, and final discussion

The performance of the optimized MIM sensor is demonstrated through transmission simulations, highlighting its innovative design and its potential as a highly effective RI sensor. The results reveal that this sensor design achieves excellent transmission efficiency and sensitivity across different wavelengths, particularly in the cutoff and passband regions.

Figure 7a illustrates the transmission spectrum of the designed filter for refractive indices ranging from 0.999 to 1.003. The results clearly show that, with optimized dimensions, the sensor delivers a highly efficient transmission rate in the passband, while sharply attenuating transmission at the cutoff wavelengths. This figure spans the wavelength range from 600 nm to 1800 nm, indicating that the sensor performs well over a broad spectrum. The sharp dips at approximately 1008 nm and 1348 nm represent the cutoff bands where the transmission is effectively reduced to near-zero, confirming that the filter successfully blocks unwanted signals.

The refractive index range of 1.000 to 1.003 was selected to evaluate the sensor’s performance in detecting minute RI variations, which is crucial for applications in biosensing, chemical detection, and environmental monitoring. The value of 0.999 is uncommon for most solid or liquid materials but is representative of low-density gases under specific conditions. For instance, the refractive index of air at standard temperature and pressure (STP) is approximately 1.0003, making it a relevant reference point. Variations in air composition, temperature, or pressure can cause slight deviations in its RI, which the sensor must accurately detect. Additionally, this RI range is applicable to low-concentration aqueous solutions, where solute presence causes only minor shifts in the refractive index.

The purpose of these simulations is to measure the accuracy and high sensitivity of the designed sensor. By selecting an RI range with changes as small as 0.001, the study demonstrates the sensor’s ability to detect subtle environmental variations, which is critical for real-time gas sensing and biomedical applications. The ability to resolve such small RI differences highlights the effectiveness of the proposed design, ensuring that the sensor can be applied to high-precision monitoring systems where even the slightest RI change must be reliably detected.

From Eq. (7), we can deduce that the filter’s quality factor for the first passband is 7.43% and for the second passband it is 6.3%. The filter’s excellent bandwidth and sharpness performance are guaranteed by these features, making it an ideal choice for applications that demand accurate wavelength discrimination. The Eq. (7) can be written as:

The values of \(\:{\lambda\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\lambda\:}_{2}\) are the high and low cut-off wavelengths, which are − 3dB, respectively. Two new stubs are used to create the filter, which has final dimensions of 200 nm × 420 nm. Importantly, for the passbands, the transmission rate reaches 98.5%, while in the cutoff bands, this value approaches zero, making it suitable for attaining great selectivity and efficiency.

Figure 7b and c zoom in on the cutoff wavelengths to provide a clearer picture of the sensor’s performance. These magnified views, focusing on the ranges around working wavelengths, show how the transmission spectrum shifts as the RI changes. The transmission dips become sharper as the RI increases, demonstrating the sensor’s sensitivity to even small changes in RI. This capability is crucial for applications such as biosensing or chemical detection, where minute variations in the surrounding medium need to be detected.

One of the key performance metrics for a plasmonic sensor is its spectral sensitivity. It can be calculated using the formula \(\:S={\Delta\:}\lambda\:/{\Delta\:}n\), where \(\:{\Delta\:}n\) represents the change in the RI and \(\:{\Delta\:}\lambda\:\) is the corresponding shift in the resonant wavelength. High sensitivity indicates the sensor’s capability to detect small variations in the surrounding medium, which is critical for applications like biosensing and chemical analysis. For the proposed structure, the sensitivity values for the first and second cutoff bands are 7504 nm/RIU and 8000 nm/RIU, respectively. This indicates that the sensor demonstrates a higher sensitivity in the second cutoff band, reflecting its greater ability to detect changes in the RI at that wavelength range.

To assess the performance of the designed sensor under various conditions, several parameters are evaluated, which are calculated using the formulas provided in Eqs. (8), (9). These calculations help quantify the sensor’s effectiveness and ensure that it functions optimally across different scenarios41,42.

.

where FWHM is full wave half maximum. For the figure of merit (FOM) in the two cutoff bands, values of 250.13 (1/RIU) and 250 (1/RIU) are obtained, respectively. Additionally, the detection limit (DL) in these two bands is calculated to be 0.0039 RIU and 0.004 RIU. These results highlight the sensor’s strong performance in both sensitivity and precision across the cutoff bands. So, the performance of the sensor can be praised for its high sensitivity, dual-band filtering, and precision in blocking unwanted signals. The optimized design ensures that the sensor operates efficiently within the desired wavelength ranges, while also demonstrating excellent responsiveness to changes in the RI.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed sensor in comparison with similar designs, a comparison is presented in Table 3. The results indicate that this sensor features the smallest size among the compared sensors, while also achieving the highest sensitivity. Additionally, the use of the PSO optimization algorithm has contributed to its superior performance. In terms of quality factor and design innovation, this sensor stands out as the most advanced and innovative, making it the best overall solution in the comparison.

Fabrication challenges and practical considerations

While the proposed MIM-based dual-band plasmonic filter demonstrates exceptional performance in simulation, its practical fabrication presents several challenges that must be considered for real-world implementation:

Precision in nanofabrication

The design features nanoscale structures, including stubs with internal holes and precisely defined waveguide dimensions. Achieving such geometries requires high-resolution lithography techniques such as electron beam lithography or focused ion beam milling. However, these methods are time-consuming and costly, limiting large-scale production potential46,47.

Material compatibility and surface roughness

The proposed design utilizes silver (Ag) as the metallic layer, which offers excellent plasmonic properties but suffers from oxidation and surface roughness issues that can degrade performance over time. Alternative materials such as gold (Au) or aluminum (Al) might be considered, but each introduces trade-offs in plasmonic response, stability, and fabrication feasibility48.

Scalability and reproducibility

Large-area fabrication of such complex nanostructures remains a major hurdle. Nanoimprint lithography and self-assembly techniques have been explored for mass production but may not provide the same level of precision as electron beam lithography49. Additionally, maintaining consistent performance across multiple fabricated devices requires stringent process control and metrology techniques.

Integration with optical and sensing systems

To fully utilize this plasmonic structure in biosensing or chemical detection applications, integration with microfluidic channels or fiber-optic systems must be considered. Challenges include alignment accuracy, biocompatibility, and long-term stability of the fabricated sensor50.

Despite these challenges, recent advancements in hybrid nanofabrication techniques, improved material engineering, and scalable lithographic methods have significantly enhanced the feasibility of plasmonic sensors for real-world applications. Future work will focus on developing cost-effective, high-throughput fabrication techniques to bridge the gap between theoretical designs and experimental realization.

Conclusion

An MIM filter having two cut-off bands, one at 1008 nm and one at 1348 nm, was developed for use in RI sensing in this paper. To get the most out of it, we used the PSO algorithm to dial in the exact size of the filter. The developed sensor has remarkably small dimensions of about 200 nm × 420 nm, which makes it an incredibly tiny option for applications that need to be miniaturized. With first cut-off band values of 7504 nm/RIU and second band values of 8000 nm/RIU, the sensor showed great sensitivity performance. The sensor’s accuracy and capacity to detect minute changes in RI are further demonstrated by its low detection limits of 0.0039 RIU and 0.004 RIU, as well as its high FOM values of 250.13 (1/RIU) and 250 (1/RIU), respectively. The optical response of the structure was also faithfully reproduced by the FDTD simulation, which utilized the Drude-Debye model to account for the dielectric characteristics of the metal. Biosensing, environmental monitoring, and chemical detection are just a few of the many real-time sensing applications that might benefit from the sensor’s dual-band architecture, small size, and high sensitivity. An effective and adaptable solution for cutting-edge sensor technologies, the optimized design guarantees efficient operation across the desired wavelength ranges.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chao, C. T. C. et al. Plasmonic refractive index sensor based on the combination of rectangular and circular resonators including baffles. Chin. J. Phys. 71, 286–299 (2021).

Zonouri, S. A., Basem, A. & Younis Al-zahy, M. A. Innovative MIM diplexer with neural network enhanced refractive index detection for advanced photonic applications. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 31473 (2024).

Chau, Y. F. C. Enhancing imaging capabilities with a high-sensitivity multichannel optical filter. Micro Nanostruct. 186, 207732 (2024).

Butt, M. A. Review of Innovative Cavity Designs in Metal–Insulator-Metal Waveguide-based Plasmonic Sensors, 1–20 (Plasmonics, 2024).

Butt, M. A., Kazanskiy, N. L. & Khonina, S. N. Tapered waveguide mode converters for metal-insulator-metal waveguide plasmonic sensors. Measurement 211, 112601 (2023).

Chau, Y. F. C. Enhancing broadband Terahertz absorption via a graphene-based metasurface absorber featuring a rectangular ring and triple crossbars. Phys. Scr. 99 (5), 055905 (2024).

Ebbesen, T. W., Lezec, H. J., Ghaemi, H. F., Thio, T. & Wolff, P. A. Extraordinary optical transmission through sub-wavelength hole arrays. Nature 391 (6668), 667–669 (1998).

Barnes, W. L., Dereux, A. & Ebbesen, T. W. Surface plasmon subwavelength optics. Nature 424 (6950), 824–830 (2003).

Zonouri, S. A. et al. A dual-mode graphene-based optical sensor with high sensitivity for cancer-cell detection. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56 (11), 1808 (2024).

Libon, I. et al. An optically controllable Terahertz filter. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76 (20), 2821–2823 (2000).

Butt, M. A. & Piramidowicz, R. Orthogonal mode couplers for plasmonic chip based on metal–insulator–metal waveguide for temperature sensing application. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 3474 (2024).

Butt, M. A., Khonina, S. N. & Kazanskiy, N. L. Simple and improved plasmonic sensor configuration established on MIM waveguide for enhanced sensing performance. Plasmonics 17 (3), 1305–1314 (2022).

Zonouri, S. A. & Hayati, M. Design and simulation of MIM optical filter structure based on plasmonic diagonal T-Shaped resonators using ANN method. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 22, 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNANO.2023.3305020 (2023).

Rahad, R. et al. Plasmonic Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) Refractive Index Sensor for Glucose Level Monitoring, 1–10 (Plasmonics, 2024).

Chau, Y. F. C. Mid-infrared sensing properties of a plasmonic metal–insulator–metal waveguide with a single stub including defects. J. Phys. D. 53 (11), 115401 (2020).

Zonouri, S. A. & Hayati, M. Design of a MIM sensor using an optical resonator and GMDH algorithm for high efficiency applications. J. Comput. Electron. 23 (2), 467–480 (2024).

Shi, Q. et al. Tunable plasmon refractive index sensor and a slow-light device optimized by an improved genetic algorithm based on a MIM waveguide. JOSA B. 41 (2), A6–A17 (2024).

Liu, H. & Maghsoodloo, S. Simulation optimization based on Taylor kriging and evolutionary algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 11 (4), 3451–3462 (2011).

Sahoo, S. K. et al. Moth flame optimization: theory, modifications, hybridizations, and applications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30 (1), 391–426 (2023).

Han, L., Xu, C., Huang, T. & Dang, X. Improved particle swarm optimization algorithm for high performance SPR sensor design. Appl. Opt. 60 (6), 1753–1760 (2021).

Abedi, K. & Mirjalili, S. M. Slow light performance enhancement of Bragg slot photonic crystal waveguide with particle swarm optimization algorithm. Opt. Commun. 339, 7–13 (2015).

Zhu, J. & Lou, J. High-sensitivity Fano resonance temperature sensor in MIM waveguides coupled with a polydimethylsiloxane-sealed semi-square ring resonator. Results Phys. 18, 103183 (2020).

Zonouri, S. A. & Hayati, M. A compact graphene-based dual-band band-stop filter using new hook-shaped resonator for THz applications. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 153, 107150 (2023).

Chou Chau, Y. F. et al. Significantly enhanced coupling effect and gap plasmon resonance in a MIM-cavity based sensing structure. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 18515 (2021).

Chao, C. T. C. et al. Visible-range multiple-channel metal-shell rod-shaped narrowband plasmonic metamaterial absorber for refractive index and temperature sensing. Micromachines 14 (2), 340 (2023).

Chau, Y. F. C. Enhanced plasmonic waveguide sensing performance with a semicircular-ring resonator. Micro Nanostruct. 174, 207469 (2023).

Chou Chao, C. T. & Chou Chau, Y. F. Highly sensitive multichannel Fano resonance-based plasmonic sensor for refractive index and temperature sensing application. In Photonics (Vol. 10, No. 1, 82). (MDPI, 2023).

Chou Chau, Y. F. Multiple-mode bowtie cavities for refractive index and glucose sensors working in visible and near-infrared wavelength ranges. Plasmonics 16 (5), 1633–1644 (2021).

Wang, L., Zeng, Y. P., Wang, Z. Y., Xia, X. P. & Liang, Q. Q. A refractive index sensor based on an analogy T shaped metal–insulator–metal waveguide. Optik 172, 1199–1204 (2018).

Taflove, A., Hagness, S. C. & Piket-May, M. Computational electromagnetics: the finite-difference time-domain method. Electr. Eng. Handb. 3 (629–670), 15 (2005).

Maier, S. A. Plasmonics: Fundamentals and Applications, 245 (Springer, 2007).

Sabaruddin, N. R. et al. Designing a Broadband Terahertz Metamaterial Absorber Through bi-layer Hybridization of Metal and Graphene, 1–14 (Plasmonics, 2024).

Choi, B. B., Kim, B., Bice, J., Taylor, C. & Jiang, P. Inverse DVD-R grating structured SPR sensor platform with high sensitivity and figure of merit. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 116, 321–330 (2022).

Ghasemi, M. R., Moghadam, L., Bayati, M. S. & P., & Design of a tunable metal–insulator-metal power splitter and wavelength demultiplexer for optical interconnect networks. Opt. Quant. Electron. 56 (8), 1289 (2024).

Qiao, L., Zhang, G., Wang, Z., Fan, G. & Yan, Y. Study on the Fano resonance of coupling M-type cavity based on surface plasmon polaritons. Opt. Commun. 433, 144–149 (2019).

Kennedy, J. & Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks (Vol. 4), 1942–1948 (IEEE, 1995), November.

Clerc, M. & Kennedy, J. The particle swarm-explosion, stability, and convergence in a multidimensional complex space. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 6 (1), 58–73 (2002).

Bai, Q. Analysis of particle swarm optimization algorithm. Comput. Inform. Sci. 3 (1), 180 (2010).

Fakhouri, H. N., Hudaib, A. & Sleit, A. Multivector particle swarm optimization algorithm. Soft. Comput. 24 (15), 11695–11713 (2020).

Zonouri, S. A., Hayati, M. & Bahrambeigi, M. Design of dual-band Wilkinson power divider based on novel stubs using PSO algorithm. Int. J. Microw. Wirel. Technol. 15 (9), 1495–1506 (2023).

Sun, Y., Ren, Y., Qu, D., Qin, F. & Li, C. Plasmonic Sensor Based on S-Shaped Metal-Insulator-Metal Waveguide for the Detection of Water-Soluble Vitamins, 1–9 (Plasmonics, 2024).

Yadav, G. K., Metya, S. K., Zafar, R. & Garg, A. K. High sensitivity plasmonic refractive index sensor for early anaemia detection. Photonics Nanostructures-Fundamentals Appl. 58, 101235 (2024).

Achi, S. E., Hocini, A., Salah, H. B. & Harhouz, A. Refractive index sensor MIM based waveguide coupled with a slotted side resonator. Progress Electromagnet. Res. M. 96, 147–156 (2020).

Yan, S. et al. MIM waveguide based nano refractive index sensor for hemoglobin and glucose concentration detection in human body. Phys. Scr. 99 (6), 065541 (2024).

Chang, S. et al. Nanosensor based on the circular ring with external rectangular ring structure. In Photonics (Vol. 11, No. 6, 568). (MDPI, 2024).

Matsui, S. et al. Three-dimensional nanostructure fabrication by focused-ion-beam chemical vapor deposition. J. Vacuum Sci. Technol. B: Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 18 (6), 3181–3184 (2000).

Pease, R. F. & Chou, S. Y. Lithography and other patterning techniques for future electronics. Proc. IEEE. 96 (2), 248–270 (2008).

Wadell, C., Syrenova, S. & Langhammer, C. Plasmonic hydrogen sensing with nanostructured metal hydrides. ACS Nano. 8 (12), 11925–11940 (2014).

Schift, H. Nanoimprint lithography: an old story in modern times? A review. J. Vacuum Sci. Technol. B: Microelectron. Nanometer Struct. Process. Meas. Phenom. 26 (2), 458–480 (2008).

Stewart, M. E. et al. Nanostructured plasmonic sensors. Chem. Rev. 108 (2), 494–521 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. D.: Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology, and M. R. M.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Darabi, A., Malekshahi, M.R. Design and optimization of a compact dual band metal insulator metal filter for high sensitivity refractive index sensing using particle swarm optimization. Sci Rep 15, 22436 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05569-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05569-x