Abstract

The formulations were prepared using standard protocols, with 4% (w/w) spirulina powder added to each product. After each digestion phase, the samples were analyzed for carbohydrates, protein, carotenoids, and phycocyanin. The results showed that the formulated food products had altered nutritional compositions compared to their spirulina-free counterparts, with increased protein and decreased carbohydrate levels. Our findings indicated that spirulina-infused formulation exhibited increasing concentrations of carotenoids in cake (186.468 µg/g), peanut balls (164.596 µg/g), and biscuit (196.448 µg/g) and in the case of phycocyanin levels were found to higher in the spirulina infused cake (6.097 mg/g), peanut balls (6.88 mg/g), biscuit (5.467 mg/g). In contrast, phycocyanin is a potential antioxidant that is only present in spirulina-infused formulations, not in non-infused snack formulations. Thus, uniqueness gives better nutritional and therapeutic value to spirulina-infused formulations. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the digestibility and bioavailability of nutrients in spirulina-based nutrition formulations, contributing to their potential health benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spirulina belongs to the Cyanobacteria phylum, found as either blue-green bacteria or algae, both common foods and nutritional supplements1. Spirulina is a kind of blue-green vegetable microalgae that grows only in lakes with high alkalinity levels. Additionally, spirulina is one of the rich sources of carotenoids, phycocyanin, essential fatty acids, vitamin E, B complex vitamins, copper, manganese, magnesium, iron, selenium, and zinc2. It also possesses potent biologically active compounds like polyunsaturated fatty acids, phycocyanin, and phenolics, responsible for its medicinal benefits3,4,5. Many reports in the literature have explored the biochemical properties of spirulina, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immune booster; apart from that, spirulina contributes a major role in combat malnutrition diseases because it contains close to 60% proteins6. While phycocyanin extracted from Spirulina is used as an industrial and food coloring agent4,7. Spirulina is a commercial food supplement that can overcome vitamin deficiency and protein energy malnutrition through pills and/or tablets. The processing and transportation of algal biomass need highly skillful personalities to avoid environmental pollution8. In addition to those the nutritional and toxicological properties of the formulated food supplements may vary because of cultivation techniques developed to improve the productivity levels and meet the rising demand for these products. The feed also influences the chemical footprint of the algal biomass applied and the method followed for production9. To analyze the quantity and quality of nutrients in processed or supplemented food preparations, it is crucial to assess the effects of temperature on the nutritional contents of spirulina. According to the research, cooking spirulina at a temperature of 100 °C for 10 to 15 min can be considered as safe10.

The previous reports in the literature specifically address the anticancer activity evaluated using cell culturing techniques. This may be due to the presence of biologically active polysaccharides in the spirulina, which possess DNA cleavage and nuclease-like activity, thereby blocking cell proliferation. According to feeding studies, even small doses of spirulina strengthen the immune system through cellular and humoral defense mechanisms11,12,13. In vitro digestion models facilitate the analysis of the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of nutrients, medications, and non-nutritive substances more easily. They mimic the biological digestion process to some extent to compare the results and findings.14 15. Numerous reports in the literature strongly describe the various types of static and dynamic in vitro digestion models that explore the biological importance of drugs, food and food supplements, and non-nutritive compounds. Among the different protocols available, INFOGEST and TIM were mostly used in the digestive model for both types of processes, such as static and dynamic16. In vitro digestion models are generally used to assess the role of the food matrix in releasing essential nutrients after digestion as well as elucidate the composition of digestate compared with in vivo17. In vivo, feeding approaches using either humans or animals typically yield the most accurate results, although they are time-consuming18. Static and dynamic in vitro digestion techniques are the two main categories of techniques that are frequently utilized for food. These models try to replicate bodily processes during the upper gastrointestinal systems’ oral, gastric, and small intestine stages19. So, the present work aims to formulate three different food products like cake, biscuit, and peanut balls infused with spirulina, and evaluate the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of proteins, carbohydrates, carotenoids, and phycocyanin for understanding the health benefits of spirulina-infused food formulation.

Materials and methods

Ingredients and reagents

The spirulina-infused foods were formulated with the following ingredients: spirulina powder (Healthy Hey Organics), wheat flour, jaggery, vegetable oil, baking soda, baking powder, cumin, peanuts, and salt. The above products were purchased from a local market. For In vitro digestion: KCl (Merck, India), NaCl (Merck, India), sodium acetate (Merck, India), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (Merck, India), dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (Merck, India), acetic acid (Merck, India), amylase (TCL, India),, gastric lipase (TCL, India), pepsin (TCL, India), bile salts (TCL, India), pancreatin (TCL, India), trypsin (TCL, India). For nutritional estimation, anthrone (Merck, India), concentrated sulphuric acid (Merck, India), sodium hydroxide (Merck, India), sodium carbonate (Merck, India), cupric sulfate (Merck, India), sodium potassium tartrate (Merck, India), acetone (Merck, India), and whatmann filter paper were used.

Preparation of foods

Three food formulations, such as cake, peanut balls, and salt biscuits infused with spirulina into it. Spirulina is typically consumed in 1–3 g per day, yet up to 10 g have been used successfully13. From this each of our product 4% (w/w) of spirulina powder was used based on WHO and research-backed recommendations suggest a daily intake of 1–3 g of spirulina for general health, with therapeutic doses up to 10 g per day. The 4% spirulina content in our products was carefully chosen to ensure that consuming a reasonable portion (e.g., 1–2 servings per day) aligns with these recommended intake levels. and maintained the maximum temperature for cooking spirulina to 100℃ if necessary13 and monitored not to exceed 100℃ using standard FSSAI protocols.

Cake

140 g jaggery, boiled, filtered, and combined with 100 g wheat and 10 g spirulina powder. 250 ml vegetable oil, a pinch of baking soda and baking powder, and vanilla essence were combined and thoroughly mixed. Bake the cake for 40 min on low heat with the container closed20.

Peanut balls

140 g of powdered jaggery, 100 g of roasted peanut, and 10 g of spirulina powder were mixed thoroughly and molded into balls used for in vitro digestion models21.

Salt biscuit

40 g of jaggery and 10 g of salt were added, and 200 ml of vegetable oil was mixed finely. Then, 200 g of wheat flour and 10 g of spirulina powder were mixed thoroughly into the prepared jaggery mixture. Finally, make the flour into biscuit shapes and bake it for 15–20 min at low flame22.

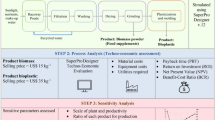

In Vitro modified dynamic digestion

After successfully preparing three formulations, Cake, Peanut balls, and Salt biscuits, 100 mg/ml in each formulation was taken for crushing using a mortar pestle, which mimics the chewing23. Salivary juice was prepared by adding 0.12 g of NaCl, 0.15 g of KCl, and 2.0 g of amylase in 1 L of distilled water with a pH of 7. Gastric juice was prepared by adding 0.25 g of gastric lipase and 0.236 g of pepsin in 1 L of distilled water with the pH of 3. Intestinal juice was prepared by adding 10 g of bile salt, 5 g of pancreatin, and 13 mg of trypsin in 100 ml of distilled water with a pH of 724. Acidic and basic buffers were prepared using buffer capsules of pH 3 and pH 7, respectively. Briefly, in the oral phase, 2 ml of the crushed sample was added to 2 ml of salivary juice in a ratio of 1:1 and was kept in a shaker for 5 min at 200 rpm, mimicking mouth digestion. After 5 min 10 ml of acidic buffer and 4 ml of gastric enzymes mixture was added and kept in a shaker for 2 h. at 120 rpm25 After the completion of gastric phase, 10 ml of basic buffer and 4 ml of intestinal enzymes were to the chyme (Gastric Digesta) were added and kept in a shaker for 2 h at 40 rpm26 mimicking intestinal digestion. Acidic and basic buffers were used to maintain the pH of the stomach and small intestine. At each phase of digestion, the mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was kept for further analysis (Fig. 1).

Biochemical analysis

Before and after digestion, products like cake, peanut balls, and biscuits were measured for carbohydrates, proteins, and carotenoids in spirulina-infused and control products using the methods already reported in the literature125,27,28. Bio accessibility (BA) and Bioavailability for the digested products were measured using the formula reported previously in the literature29.

Statistical analysis

All the data were expressed as mean ± Standard Deviation with n = 4 and carried out two-way ANOVA with 95% confidence interval (p < 0.05) between the groups.

Results and Discussion

Food formulation exhibited differences in color and structures

Spirulina was successfully incorporated into all three products. The cake and peanut balls were darker green than the salt biscuits due to the infusion of spirulina into the cake and peanut balls. Salt biscuits were dry and brittle in nature. The cake was soft and airy. Peanut balls were sweeter than cake and salt biscuits, which may be attributed to the sweet taste and the quantity of jaggery added to the cake30,31. The preparation methods for these products are simple, cost-effective, and adaptable for small-scale or large-scale production. Additionally, they do not require highly specialized equipment, making them feasible for real-world applications. Among the food items, peanut balls were sweeter because the ingredients used were only 3 (peanut, jaggery, spirulina). Here, the peanut and spirulina do not suppress the sweetness of jaggery. Peanut balls were the only product prepared without any heat. In spirulina-infused biscuits, wheat suppresses the sweetness of jaggery. These findings are also correlated with the previous reports indicating the preparation of spirulina-infused cookies and spirulina-infused ragi biscuits, which increase the protein content and improve sensory factors30.

Nutritional values of Spirulina-infused formulations (Cake, peanut balls and salt biscuits)

Table 1. Raw food samples quantification with and without infusion of spirulina. Values are expressed as mean ± S.D, n = 4. * p < 0.05 with non-spirulina-infused products. **p < 0.0001 with non-spirulina infused products.

Visual transformation of food products

Three different spirulina-infused formulations were prepared for dynamic in vitro digestion protocols. The breakdown of the food matrix at each phase of in vitro digestion was well observed by the change in color of the products. Images (Fig. 3) were taken at the end of sample preparation, mouth, gastric, and intestinal phases, with time intervals of 0, 5, 125, and 245 min, respectively. The dark green color completely disappeared in the peanut balls, showing the quick degradation of the food matrix and exposed acidic pH and finally turning into brown compared with cake and salt biscuits. This is primarily due to the release of carotenoids and phycocyanin in every stage of the digestion, from a green color to a brown tone. This may be due to the vibrant degradation of phycocyanin with changes in pH from 7 to 3 and 7 from the oral phase to the intestinal phase, as well as by mechanical degradation of the food matrix34.

Biochemical analysis

At each phase of digestion, nutrients like carbohydrates, carotenoids, and phycocyanin were quantified and compared with the native amount of nutrients in the formulations. After intestinal digestion, the mixture was separated into supernatant (filtrate) and pellet (retentate) by Whatmann filter paper. Values are expressed as Mean ± SD with four independent trials. Foods with a porous structure, such as cake or bread, contain air pockets or cavities that facilitate enzyme penetration and favor digestion. The porous structure allows for a larger surface area, increasing the exposure of enzymes to the food particles and enhancing digestion. Foods with a denser structure, like peanut balls or certain biscuits, may have a more compact and solid matrix. This denser structure can slow digestion since enzymes take longer to penetrate and break down the food particles.

Protein quantification

The total protein content of the three different formulated food items varied significantly, with salt biscuits having the highest amount at 18.8%, peanut balls at 13.4%, and cake at 10.9%. During the mouth phase of digestion, cake and peanut balls released approximately half of their total protein from the matrix, with 55.4% and 59.5%, respectively (p < 0.05), significantly compared with the native formulation. The soft and airy nature of the cake and the preparation method involving powdered supplements and the crushing of peanut balls contributed to the higher protein release in the mouth phase. In contrast, the dry and brittle characteristics of the salt biscuit resulted in a protein release of around 24.7% during the mouth phase. However, salt biscuits exhibited a significant amount of protein released in the intestinal phase, suggesting differences in protein breakdown and release based on the food item composition and characteristics compared with other digestive phases (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). The results clearly indicated that the total protein contents were significantly reduced in the non-absorbed (small intestine – pellet) and absorbed (small intestine – supernatant) compared with the total proteins (p < 0.05), which may be attributed to the release of proteins in the spirulina and conversion of proteins into amino acids indicate maximum conversion of proteins. These results are concurrent with the previous reports on the in vitro digestibility of spirulina-infused formulations due to the release of protein in every stage of digestion from the food matrix.

Carbohydrate quantification

The spirulina infused formulations often contains large amount of carbohydrates due to their ingradients that includes jaggery and wheat, typically ranging from 60 to 80%. IN general, Wheat has a carbohydrate content of around 72%, while jaggery has an even higher carbohydrate content of approximately 98%. In the formulation, the carbohydrate content of the cake, peanut ball, and salt biscuit is 84.7%, 62.4%, and 74.2%, respectively. During the oral phase of digestion, all three food items release approximately 3–4.5% of their carbohydrates. In contrast, during the stomach phase, the cake and salt biscuit have released about 11–12% of their carbohydrate content (p < 0.05), while the peanut ball exhibits a slightly higher release of 18%. In the intestinal phase, the cake had released 24.4% of its carbohydrates significantly compared with the other two formulations. The peanut balls demonstrated an even higher release of carbohydrtaes from the matrix (32.4%), while the salt biscuit exhibited a lower release percentage of 13.5% (Fig. 3). The release of carbohydrates from the food matrix is also influenced by various factors, which include pH, enzymes, and mechanical degradation. Our findings clearly indicated that a significant quantity of carbohydrates was released at the last stage of digestion. This is because of the complete degradation of carbohydrates into their corresponding monomeric units. This, in turn, increases the bioavailability of carbohydrate monomers.

Total carotenoid content

Carotenoid content in the spirulina-infused formulation is less than 0.02% from the 4% spirulina infusion. The quantity of carotenoids present in the spirulina-infused food formulations such as cake, peanut balls, and salt biscuits were 186.2, 167.1, and 196.05 µg/g. After the process of in vitro digestion, we found that the release of carotenoids increased significantly between the formulations like cake, biscuit, and peanut balls. This may be attributed to the architecture of the food matrix, which releases the carotenoids in the different stages of the digestion process concurrent with the previous reports35.The release of carotenoids from spirulina-infused cake was relatively low across all phases of digestion compared with biscuits and peanut balls (p < 0.05). The mouth phase showed the lowest release (1.6%), and there was a noticeable increase in carotenoid release in the stomach phase, possibly due to hydrochloric acid that degraded the matrix (6.43%)35. The highest release occurred in the intestine phase (48.2%) (p < 0.05). The release of carotenoids from peanut balls was moderately higher compared to cake. The mouth phase showed a higher release (2.79%) of carotenoids from all three food formulations. On the other hand, the release of carotenoids decreased in the stomach phase (4.6%). However, a significant increase in carotenoid release was observed in the intestine phase (50.38%). The release of carotenoids from the salt biscuit was relatively low in the mouth (0.3%) and stomach (1.9%) phases. However, the release significantly increased in the intestine phase (p < 0.05) (33.7%) (Fig. 4).

Phycocyanin content

Phycocyanin is one of the important antioxidant protein pigment complexes widely present in microalgae, including spirulina. Our results clearly indicated that the changes in the color of the spirulina-infused cake, peanut ball, and salt biscuit are due to the successful incorporation of spirulina phycocyanin into the products and approximately 0.5–0.7%. The release of phycocyanin from the spirulina-infused cake was relatively low in the mouth phase (7.4%), and there was a noticeable increase in phycocyanin release in the stomach phase (8.8%) due to acid digestion. The highest release occurred in the intestine phase (52.3%). The release of phycocyanin from peanut balls showed a higher percentage in the mouth phase (10.4%), and the release decreased in the stomach phase (6.8%), suggesting partial degradation of the peanut balls compared with cake and biscuits, which may be attributed to the difference in the food matrix architecture. The highest release was observed in the intestine phase (53.8%), indicating efficient breakdown and subsequent release of phycocyanin for absorption. The release of phycocyanin from the salt biscuit was relatively low in the mouth phase (5.7%) and increased in the stomach phase (17.7%). The release further increased in the intestine phase (36.2%) (Fig. 5). The slow-releasing pattern for phycocyanin may be attributed to the encapsulation of spirulina with carbohydrates and lipids in the food matrix. The maximum release of phycocyanin in the gastric phase is due to acid and mechanical degradation of the food matrix to release water-soluble phycocyanin On the other hand, in the intestinal phase, the presence of bile salts facilitates the release of phycocyanin for the food matrix7.

In vitro bioaccessibility and In vitro bioavailability

Bio accessibility has been calculated from the above equation mentioned in the methodology (Sect. 2.8), a fraction of the nutrient released during digestion(supernatant). The bioaccessibility of protein was higher in the salt biscuit (83.4%), followed by peanut balls (77.8%) and cake (60.6%). This suggests that the salt biscuit is the most efficient to release the protein accessible for absorption after digestion. Cake showed the lowest protein bioaccessibility, indicating that the structural composition or matrix arrangements might hinder protein breakdown and release. The bioaccessibility of carbohydrates was highest in peanut balls (54.9%), followed by cake (39.9%) and salt biscuits (29.1%). This indicates that peanut balls have a higher potential for carbohydrate release and accessibility during digestion. Salt biscuits showed the lowest bioaccessibility of carbohydrates, suggesting that their network as well as the quantity of the carbohydrates might have an influence of carbohydrate digestion and release after digestion. The bioaccessibility of carotenoids was relatively similar across all three food formulations, with percentages ranging from 35.9 to 50.8%. This suggests that the digestion process and factors influencing carotenoid release and accessibility may have comparable effects across spirulina-infused food formulations. The bioaccessibility of Phycocyanin was relatively high for all three food items, with percentages ranging from 59.6 to 73.9% compared with carotenoids36,37. This suggests that digestion is generally efficient in releasing phycocyanin accessible for absorption. Among the three-food spirulina infused food formulations, salt biscuits had the highest protein bioavailability (60.1%), followed by peanut balls (50.4%) and cake (23%). Peanut balls showed the highest carbohydrate bioavailability (24.2%), followed by cake (9.1%) and salt biscuits (2.5%). Carotenoid bioavailability varied across the food items, with salt biscuits having the lowest bioavailability (6.2%) and cake having the highest (20.5%). For phycocyanin, peanut balls and salt biscuits exhibited similar bioavailability (39.4% and 39.9%, respectively), while cake had the lowest bioavailability (13.3%). These findings suggest that the bioavailability of nutrients varies among the food items, likely influenced by factors such as food composition and structural characteristics. Further research is needed to understand better these findings’ implications for nutritional value and potential health benefits38.

Overall, the research findings provide insights into the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of essential nutrients and bioactive compounds in spirulina-infused food products. This information can contribute to a better understanding of these products’ nutritional benefits and biological significance. Further research and optimization of formulation and digestion protocols can help enhance spirulina’s nutritional value and bioavailability in food products for improved health outcomes. These formulations may have a potential lead in the food and nutritional based industry for preparing low glycemic index healthy snacks and supplements in future.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Manzoor, M. F. et al. Recent progress in natural seaweed pigments: green extraction, health-promoting activities, techno-functional properties and role in intelligent food packaging. J. Agric. Food Res. 15, 100991 (2024).

Dillon, J. C., Phuc, A. P. & Dubacq, J. P. Nutritional value of the Alga Spirulina. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 77, 32–46 (1995).

Bhat, V. B. & Madyastha, K. M. Scavenging of peroxynitrite by phycocyanin and Phycocyanobilin from Spirulina platensis: protection against oxidative damage to DNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 285, 262–266 (2001).

Piñero Estrada, J. E. & Bermejo Bescós, P. Villar Del fresno, A. M. Antioxidant activity of different fractions of Spirulina platensis protean extract. Farmaco 56, 497–500 (2001).

Nagaoka, S. et al. A novel protein C-phycocyanin plays a crucial role in the hypocholesterolemic action of Spirulina platensis concentrate in rats. J. Nutr. 135, 2425–2430 (2005).

Manzoor, M. F. et al. Nutraceutical tablets: manufacturing processes, quality assurance, and effects on human health. Food Res. Int. 197, 115197 (2024).

Santana Andrade, J. K. et al. Bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds after in vitro Gastrointestinal digestion and probiotics fermentation of Brazilian fruits residues with antioxidant and antidiabetic potential. LWT 153, 112469 (2022).

Chapman, V. J. & Chapman, D. J. Seaweeds and their Uses (Springer Netherlands, 1980). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-5806-7

Rao, G. P. & Singh, P. Value addition and fortification in Non-Centrifugal sugar (Jaggery): A potential source of functional and nutraceutical foods. Sugar Tech. 24, 387–396 (2022).

Qureshi, M. A., Garlich, J. D. & Kidd, M. T. Dietary Spirulina platensis enhances humoral and cell-mediated immune functions in chickens. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 18, 465–476 (1996).

Pang, Q. S., Guo, B. J. & Ruan, J. H. [Enhancement of endonuclease activity and repair DNA synthesis by polysaccharide of Spirulina platensis]. Yi Chuan Xue Bao. 15, 374–381 (1988).

Shen, C. H. Quantification and analysis of proteins. in 187–214 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802823-0.00008-0

Grosshagauer, S., Kraemer, K. & Somoza, V. The true value of Spirulina. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 4109–4115 (2020).

Joye, I. J., Davidov-Pardo, G. & McClements, D. J. Nanotechnology for increased micronutrient bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 40, 168–182 (2014).

Hur, S. J., Lim, B. O., Decker, E. A. & McClements, D. J. In vitro human digestion models for food applications. Food Chemistry 125, 1–12 (2011).

Lucas-González, R., Viuda-Martos, M. & Pérez-Alvarez, J. A. Fernández-López, J. In vitro digestion models suitable for foods: opportunities for new fields of application and challenges. Food Res. Int. 107, 423–436 (2018).

Mackie, A., Mulet-Cabero, A. I. & Torcello-Gómez, A. Simulating human digestion: developing our knowledge to create healthier and more sustainable foods. Food Funct. 11, 9397–9431 (2020).

Boisen, S. & Eggum, B. O. Critical evaluation of in vitro methods for estimating digestibility in Simple-Stomach animals. Nutr. Res. Rev. 4, 141–162 (1991).

Huang, M., Zhao, X., Mao, Y., Chen, L. & Yang, H. Metabolite release and rheological properties of sponge cake after in vitro digestion and the influence of a flour replacer rich in dietary fibre. Food Res. Int. 144, 110355 (2021).

(PDF) Optimization of Spirulina-Enriched Vegan Cake Formulation Using Response Surface Methodology. ResearchGate (2025). https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.70116

Kamath, P. et al. Effectiveness of peanut ball intervention on childbirth experiences, maternal satisfaction and behavioural responses among pregnant mothers: A randomised control trial. Clin. Epidemiol. Global Health. 29, 101712 (2024).

Dantas, B. S. et al. SALT COOKIE ENRICHED WITH SPIRULINA PLATENSIS. (2019).

Full article. Comparison of five in vitro digestion models to in vivo experimental results: lead bioaccessibility in the human Gastrointestinal tract. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10934520701434919

Park, S., Mun, S. & Kim, Y. R. Effect of Xanthan gum on lipid digestion and bioaccessibility of β-carotene-loaded rice starch-based filled hydrogels. Food Res. Int. 105, 440–445 (2018).

Flores, F. P., Singh, R. K., Kerr, W. L., Pegg, R. B. & Kong, F. Total phenolics content and antioxidant capacities of microencapsulated blueberry anthocyanins during in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 153, 272–278 (2014).

Loo, Y. T. et al. Sugarcane polyphenol and fiber to affect production of short-chain fatty acids and microbiota composition using in vitro digestion and pig faecal fermentation model. Food Chem. 385, 132665 (2022).

Dala-Paula, B. M., Deus, V. L., Tavano, O. L. & Gloria, M. B. A. In vitro bioaccessibility of amino acids and bioactive amines in 70% cocoa dark chocolate: what you eat and what you get. Food Chem. 343, 128397 (2021).

Ohemeng-Ntiamoah, J. & Datta, T. Evaluating analytical methods for the characterization of lipids, proteins and carbohydrates in organic substrates for anaerobic co-digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 247, 697–704 (2018).

Zavřel, T., Chmelík, D., Sinetova, M. A. & Červený, J. Spectrophotometric determination of Phycobiliprotein content in Cyanobacterium Synechocystis. J. Vis. Exp. 58076 https://doi.org/10.3791/58076 (2018).

Kumar, T. M., Nikhil, M. & Padmavathi, T. V. N. Development and evaluation of spirulina ragi biscuits. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 8, 208–210 (2020).

Prakash, G. & Pandey, V. Development and quality evaluation of cookies fortified with Spirulina. Int. J. Agric. Food Sci. 5, 162–166 (2023).

Technology of Biscuits, Crackers and Cookies. (2000).

Koli, D., Rudra, G., Bhowmik, S., Pabbi, S., Nutritional & A. & Functional, textural and sensory evaluation of Spirulina enriched green pasta: A potential dietary and health supplement. Foods 11, 979 (2022).

(PDF) Stability of phycocyanin extracted from Spirulina sp.: Influence of temperature, pH and preservatives. ResearchGate (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2012.01.010

Mishra, A. K. et al. The influence of food matrix on the stability and bioavailability of phytochemicals: A comprehensive review. Food Humanity. 2, 100202 (2024).

Colosimo, R., Warren, F. J., Finnigan, T. J. A. & Wilde, P. J. Protein bioaccessibility from mycoprotein hyphal structure: in vitro investigation of underlying mechanisms. Food Chem. 330, 127252 (2020).

O’Connell, O., Ryan, L., O’Sullivan, L., Aherne-Bruce, S. A. & O’Brien, N. M. Carotenoid micellarization varies greatly between individual and mixed vegetables with or without the addition of fat or fiber. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 78, 238–246 (2008).

Hassaan, M. S. et al. Comparative study on the effect of dietary β-carotene and phycocyanin extracted from Spirulina platensis on immune-oxidative stress biomarkers, genes expression and intestinal enzymes, serum biochemical in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 108, 63–72 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Prof. TRR’s funds from SASTRA-deemed University and infrastructural support from SASTRA-deemed University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC - Carryout experiments and curation of Data. Draft writingKK - Literature Collection, Experiments and Curation of Data, Drafting the PaperARR - Compilation of Data, SS - Idea Generation and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and animal rights

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chinnadurai, S., Kumar, K., Ramu, A.R. et al. In vitro digestion of cake, biscuit and peanut balls infused with Spirulina using dynamic models. Sci Rep 15, 33851 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05595-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05595-9