Abstract

In this study, the impact of Al, Co, and Cu as promoters for NiO to enhance its catalytic performance in methane decomposition has been investigated. The catalysts were synthesized via a co-precipitation route and comprehensively characterized using SEM, BET, XRD, XPS, Raman, TPR, and TGA techniques. Catalytic performance was evaluated in a fixed-bed reactor operated at 800 °C with a feed gas flow rate of 20 mL/min. Al³⁺ and Cu²⁺ incorporation into NiO reduced crystallite size and increased surface area, while Co2+ had the opposite effect, indicating a distinct structural impact. Additionally, Al³⁺ doping induced a charge imbalance in NiO, leading to an increase in Ni2⁺ content and oxygen vacancies, as confirmed by XPS analysis. Catalytic activity tests revealed that Al³⁺ was the most effective promoter for NiO, followed by Co²⁺ and Cu²⁺, respectively. The highest CH₄ conversion rate and H₂ production rate, achieved with 10% Al-NiO at a time-on-stream (TOS) of 25 min, were 71% and 216.2 × 10⁻⁵ mol H₂ g⁻¹ min− 1, respectively. The methane decomposition process exhibited stable operation with minimal CO and CO₂ emissions. The catalytic performance was correlated with the detailed physicochemical properties of both fresh and spent catalysts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Presently, the world’s major energy needs are met through the consumption of natural fossil fuels. The commercial use of fossil fuels creates two major issues for the modern world, (1): reducing fossil fuel reserves, and (2): increased emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) into the environment1. To address these issues, emphasis has been placed on the use of renewable energy resources, which will be challenging, require new technological developments and investments in renewable energy, and may take decades or generations to implement2. Fuel cell technologies are considered one of the best ways to deal with current energy issues and environmental crises. Fuel cells are electrochemical equipment that convert hydrogen into electrical energy and heat3. Therefore, hydrogen energy has become one of the alternative sources that can play a role in reducing fossil fuel consumption and controlling environmental pollution. The use of fuel cell technology has led to a growing demand for hydrogen production in many industrial applications4. The technology of fuel cells is more appropriate and greener than present combustion fuels, such as gasoline and natural gas. Moreover, hydrogen can be used in many applications, such as rocket fuel, fuel for non-polluting vehicles, and clean fuel for aircraft, and water is the merely product resulting from the hydrogen combustion. The uses of hydrogen also extend beyond that, as it can be used in the petroleum industry, the production of ammonia, methanol, ethanol, dimethyl ether, and the hazardous waste hydrogenation5.

Several methods have been developed for hydrogen fuel production such as plasma assisted techniques6,7,8, water splitting9,10, photocatalysis11, hydrocarbon decomposition12, and steam reforming process13,14. Methane steam reforming (MSR) is presently the greatest economical pathway for hydrogen production14. Currently, about 97% of international hydrogen production is produced through MSR, accompanied by large emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). Consequently, additional technologies are being used to capture CO2, separate and storage to produce clean hydrogen, which increases production costs. To correct defects in the MSR process, thermal catalytic decomposition of methane (CDM) is a suitable and desirable alternative path to produce clean hydrogen with small levels of harmful emissions and lower energy consumption. An additional advantage of this process is the production of high-quality carbon nanomaterials with unique properties as a by-product, which is valuable in the applications of nanotechnology and nanoscience15. The thermal catalytic decomposition of methane reaction occurs in one step, as shown in the following equation16:

Methane (CH4) is an excellent source of hydrogen because it is easily obtainable and has a high hydrogen-to-carbon ratio (H/C) compared to other hydrocarbons. However, due to the strong C-H bonds in the structure of the methane molecule, non-catalytic thermal decomposition of methane requires temperatures higher than 1200 °C to obtain an acceptable yield. Consequently, employing transition metal as catalysts is a suitable approach to lower the reaction temperature of methane decomposition16.

Various transition metals have been used as catalysts for the catalytic decomposition of methane. Pt, Pd, Ru, Rh, Mo, Ni, Fe and Co are examined as effective catalysts particularly when supported on inert metal oxides such as Al2O3, MgO, TiO2 and SiO2. Fe, Co and Ni have been extensively studied due to their relative abundance and lower cost compared with noble metals. Irrespective of the noble metals, the catalytic activity of nickel (Ni) is the highest, followed by cobalt (Co), and then iron (Fe)5,15,16,17,18,19. From the literature, it was reported that nickel catalyst possesses high catalytic activity in CDM reaction, however, its activity is sensitive to reaction conditions and deactivates rapidly at high reaction temperature20,21. Sintering and agglomeration of nickel catalyst particles as well as their encapsulation with deposited carbon are considered as the main reasons for the deactivation of Ni-catalyst activity in CDM reactions22,23. Therefore, choosing the appropriate support for nickel catalyst, adding a second metal, and preparing the catalysts are the solutions to overcome the drawbacks of nickel-based catalysts23. It was reported that the alteration of nickel-based catalysts with second transition metals is a viable solution to avoid the deactivation of nickel catalysts. Ni impregnation with a second metal can lead to important changes in its stability and activity because of the effect of alloy formation24. Bayat et al.25 studied the influence of Fe addition into Ni/Al2O3 catalyst in methane decomposition reaction for hydrogen production. They observed that the addition of 10 wt% of Fe led to improving the stability and activity of Ni/Al2O3 catalyst through obstruction the carbon encapsulating formation on the surface of catalyst, along with enhancing the carbon diffusion rate. Ali et al.26 examined the influence of adding other metals, such as La, Ce, Cu, Co, and Fe, on the catalytic performance of Ni/MgO·Al2O3 catalyst at different reaction temperatures. Among the added metals studied, it was found that adding 10 wt% Cu to the Ni/MgO·Al2O3 catalyst led to an enhancement of its catalytic performance, methane conversion and hydrogen yield. Al-Fatesh et al.27,28 investigated the impact of modifying ZrO2 supports with La₂O₃ or WO₃ on the performance of Fe–Ni/x-ZrO2 catalysts for methane decomposition. Their results showed that doping ZrO₂ with La₂O₃ or WO₃ significantly enhanced hydrogen yield and catalyst stability. Further, they reported that incorporation of Ni further improved the activity and stability of all Fe-based catalysts. Awadallah et al.29 studied the effect of Mo on the catalytic activity of Ni/Al2O3 catalyst. Their results exhibited that the addition of Mo enhances methane conversions and carbon nanotube (CNT) production. They suggested that Ni component in the catalyst played a role in the decomposition of methane into hydrogen and carbon, while the Mo acts as a carbon diffusion center by facilitating the dissolution of carbon formed on the surface of the nickel particle onto the catalyst. Moreover, the presence of Mo as a promoter in the Ni/Al2O3 catalyst provided appropriate metal–support interaction, which could reduce the sintering of catalyst metals and ultimately increase the catalytic activity and stability. Chatla et al.30 investigated the effect of rare earth metals (La, Pr, Gd, Nd and Sm) adding to the Ni-Al catalyst activity for catalytic decomposition of methane. They observed that the promotion of Ni-Al catalyst with La metal has enhanced the Ni-Al catalyst activity and achieved the highest methane conversions rate compared to the parent catalyst. They attributed the improved activity of the nickel catalyst to the increase in its surface area as well as the strong interaction between nickel and rare metals.

In this study, the catalytic activity of NiO was enhanced by modifying it with secondary metals such as Al, Co, and Cu, aimed at improving its efficiency for the direct decomposition of methane into hydrogen and carbon nanostructures. This approach also seeks to avoid the need for catalyst support materials, which can sometimes cause strong metal-support interactions that reduce catalytic performance21,31,32. A key objective of this work is to develop cost-effective catalysts with well-defined properties by carefully selecting metal types and using a simple wet-chemical synthesis method, ultimately achieving high efficacy of methane decomposition.

Experimental

Synthesis of mixed oxides catalysts

Nickel nitrate hexahydrate Ni (NO3)2.6H2O, (99%), cobalt nitrate hexahydrate Co (NO3)2.6H2O (98%), copper nitrate trihydrate Cu (NO3)2.3H2O (99.5%) were purchased from Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., while aluminum nitrates nonahydrate Al (NO3)3.9H2O (98%) was supplied by alpha chemika. These chemicals have been used without additional purification. Nickel oxide, NiO, was prepared by direct calcination of nickel nitrate hexahydrate in air at temperature of 500 °C. The simple wet chemical method was adopted to synthesize mixed metal oxides. For 10 wt% Al-NiO metal oxide sample, in agate mortar 8.917 g of Ni (NO3)2.6H2O was dissolved in a small amount of distilled water while stirring it by a pestle until completely dissolved. This was followed by adding 2.78 g of Al (NO3)3.9H2O to the solution and then continuing to stir with the pestle again. The solution was kept in the air and then dried in the oven overnight at 80 °C. Later, the resultant was crushed into powder and calcined in furnace for 4 h at 500 °C. The preparation of 10% Co-Ni and 10% Cu-Ni (wt./wt.) metal oxides, same procedures were used by taking 0.9877 and 0.98 g of cobalt nitrate hexahydrate and copper nitrate trihydrate, respectively.

Characterization of materials

Characterization of fresh and spent materials (catalysts) was performed using different techniques. Texture properties of these materials, surface area and pore size, were measured utilizing Quantachrome autosorb IQ model ASIQA3V600000-6. For materials morphology, scanning electron microscope SEM (QUANTA 250 FEI; USA) was used. The identification of materials phases was confirmed using X-ray diffractometer XRD (Rigaku International) with Cu Ka radiation of =1.543 Å. Raman spectra of the materials has been taken by a Micro Raman (SENTERRA II, Brucker) spectrometer at wavelength 532 nm and laser power of 2.25 mW, respectively. The reducibility of the synthesized materials was conducted using temperature programmed reduction (TPR) (Micromeritics AutoChem-II 2920). The surface chemical composition and oxidation states of materials were investigated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, XPS. Thermo K Alpha spectrometer utilizing Al K alpha X-rays (1486.6 eV) with a spot size of 400 μm utilizing flood gun for charge compensation. Moreover, the values of all binding energy were standardized to C 1s = 284.5 eV as an internal standard. Thermogravimetric measurements, TGA, (NETZSCH TG 209 F1 Libra) was utilized in the air environment in the temperature range from room temperature up to 1000 °C, with heating rate of 10 °C/min to estimate the weight of the carbon formed on spent materials by assistance of Netzsch proteus 70 software.

Catalytic activity and product analysis

The activity of NiO, Al-Ni, Co-Ni, and Cu-Ni materials for direct methane decomposition was investigated in a fixed-bed reactor made of a quartz tube, 50 cm in length and 1.5 cm in internal diameter. A 0.5 g sample of the unreduced material was placed as a sandwich between ceramic fibers at the center of the quartz tube, which was in the middle of the heating zone at 800 °C. The materials were not subjected to reduction processes because methane itself is considered reductant. A gas mixture of 75% CH4 and 25% N2 (purity 99.99%, supplied by AHG) was used as the reactant. The flow rate of the gas mixture into the reactor was set to 20 mL/min using a mass flow controller (MKS PR4000B). Nitrogen was used as an internal standard during the analysis. The reaction products were analyzed by connecting the reactor outlet to an on-line gas chromatograph (Agilent GC Model 7890 B) equipped with a 19,043 Restek Micropacked GC Column, Shin carbon ST 80/100, 2 m, 0.53 mm i.d., Bellefonte, USA. The column was connected to a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) with helium as the carrier gas. During the analysis, the detected gas phases were unreacted to methane, nitrogen, and produced hydrogen. CO and CO2 traces were measured using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Thermo Scientific OMNIC).

Results and discussion

Fresh catalysts characterization

Textural properties

Figure 1(a, b) displays the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms and the pore size distribution profiles of fresh NiO,10%Al-NiO, 10%Co-NiO and 10%Cu-NiO materials at temperature of 77 K.

From Fig. 1 (a), the isotherm of pure NiO nanostructures exhibits a type IV isotherm with H3 hysteresis loops. According to the IUPAC classification, this result indicates that NiO has a mesoporous structure with non-rigid aggregates of plate-like particles33. The hysteresis is flattened and narrow hysteresis up to p/p° ~ 0.75 and slightly increases at higher p/p° > > 0.8 due to capillary condensation. Similar BET isotherms for NiO nanowires have been reported in34. The isotherms of NiO promoted with Al³⁺, Co²⁺, and Cu²⁺ ions also exhibit type IV with H3 hysteresis, but with varying nitrogen uptake values and steeper capillary condensation. Notably, the isotherm of 10%Al-NiO shows a wide mesoporous range from p/po ~ 0.45 − 0.9, with the highest N₂ uptake, indicating a larger and wider pore distribution compared to NiO, 10%Co-NiO, and 10%Cu-NiO materials. In contrast, the isotherm of 10%Co-NiO is lower than that of NiO, suggesting a reduced mesoporous content. The pore size distribution of these materials was also studied using the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method, and the results are plotted in Fig. 1(b). As expected, 10%Al-NiO exhibits an asymmetric monomodal-wide distribution, with a maximum pore radius at ~ 39 Å. The 10%Cu-NiO has a maximum pore radius at ~ 61 Å. In contrast, NiO and 10%Co-NiO display a very narrow distribution, suggesting consistent pore radii. Moreover, the surface areas of these materials were measured by Brunauer-Emmett Teller (BET). Table 1 summarizes the textural parameters of the examined materials, clearly showing that the surface area follows the order 10%Al-NiO > > 10%Cu-NiO > > NiO > > 10%Co-NiO. From the literature, it is suggested that the catalytic performance of materials is closely related to their porous properties35.

Morphology analysis

The surface morphology of fresh NiO and Al³⁺, Co²⁺, and Cu²⁺-doped NiO materials is shown in Fig. 2. ImageJ software was used to estimate the nanostructure size distributions for all examined samples, as seen in the inset of Fig. 2. The morphology of pure NiO nanostructures (Fig. 2 (a)) exhibits various morphologies nanostructure such as nano prism, nanoplates and nanoparticles tending to aggregate into larger grains. The NiO nanostructures have a wide size range with an average size of 300–400 nm as shown in the inset of Fig. 2(a). The incorporation of Al³⁺ and Cu²⁺ ions into NiO preserves the morphology, however, smaller size nano prism and nanoparticles with an average size of 150 nm and 120 nm for 10% Al–NiO and 10% Cu–NiO, as seen in Fig. 2 (b, d). In contrast, the incorporation of Co²⁺ ions into NiO leads to the formation of relatively larger nanoflowers and nano cauliflower as shown in Fig. 2(c). The 10% Co–NiO nanoflowers composed of petals that growth radially, while the nano cauliflower composed of aggregated nanoparticles of size 130 nm. The average size of the 10% Co–NiO nanoflowers/ nano cauliflower is 300–450 nm. The pore size/volume, which is the gap between the nanostructures, correlates with the nanostructure size. As a result, smaller nanostructures could lead to increased interparticle porosity. Therefore, the 10% Al–NiO and 10% Cu–NiO composites probably have higher porosity than pure NiO and 10% Co–NiO materials.

XRD studies

The phases and crystallinity of the examined materials have been investigated with XRD and results are depicted in Fig. 3. For the pure NiO sample, the diffraction peaks are sharp, implying a high degree of crystallinity. The peak positions at 2θ ~ 37.20°, 43.20°, 62.87°, 75.20°, and 79.38° correspond to the standard face-centered cubic (FCC) structure of NiO (JCPDS No. 04-0835). Hence, the observed peaks are indexed to the (111), (200), (220), (311), and (222) diffraction planes36. No other unknown peaks were observed suggesting the purity and mono-phase of the synthesized NiO material. The XRD patterns of NiO incorporated with Al3+, Co2+, and Cu2+ promoter ions are also presented in Fig. 3. Clearly, the XRD patterns of 10%Al-NiO, 10%Co-NiO, and 10%Cu-NiO materials resemble that of pure NiO, indicating that the NiO phase dominates in the examined materials. The absence of distinct Al, Co, and Cu peaks in the XRD patterns of these NiO-based materials likely reflects the fine distribution of these ions within the NiO matrix. Alternatively, the concentration of Al, Co, and Cu in the composites may be below the detection limit of the XRD instrument. However, zooming in on the (200) peak, as shown in the inset of Fig. 3, reveals that the width and position of the (200) peak vary upon the incorporation of Al3+, Co2+, and Cu2+ promoters’ ions. This is likely attributed to the differences in ionic radii (rNi²⁺ = 0.69 Å, rNi³⁺ = 0.56 Å, rAl³⁺ = 0.54 Å, rCo²⁺ = 0.74 Å, rCu²⁺ = 0.73 Å). A peak shift to a lower diffraction angle indicates an increase in the lattice spacing (d-spacing) of the crystal lattice, and vice versa. Meanwhile, the broadening of the diffraction peaks suggests a reduction in crystallite size. The crystallite size and lattice parameter a of the pure NiO and NiO-based materials were calculated from the (200) peak using the Scherrer equation G\(\:=\frac{0.9\cdot\:\lambda\:}{\beta\:\cdot\:\text{cos}\theta\:}\), and the relation \(\:a=\sqrt{{d}^{2}\left({h}^{2}+{k}^{2}+{l}^{2}\right)}\), respectively. Here, λ = 1.54 Å, β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM), hkl refers to the miller indices of the peak (200) at angle θ and d is the inter-planar distance. Table 2 summarizes the XRD analysis data of the examined materials.

As inferred from Table 2, the crystallite size of NiO decreases upon the incorporation of Al³⁺ and Cu²⁺, from 30.5 nm to 28.5 nm and 25.11 nm, respectively. Meanwhile, the crystallite size increases to 35.6 nm with the incorporation of Co²⁺ ions. The crystallite size estimated from the XRD data of NiO-based materials shows somewhat the same trend as the nanostructure size estimated from SEM images. Furthermore, based on the lattice parameter a value, it can be suggested that the NiO lattice is slightly compressed with Al³⁺ and Cu²⁺, while it expands with Co²⁺ incorporation. The observed slight lattice compression upon Cu²⁺ incorporation may not be explained by ionic size alone and probably due to Jahn-Teller compression37. Similar observations have been reported for NiO structures upon the incorporation of Al³⁺, Cu²⁺, and Co²⁺ ions38,39,40. The compression of the lattice parameters likely induces structural defects, which play a crucial role in catalytic performance.

H2-TPR measurements

Figure 4 shows the H2-TPR profiles of pure NiO and NiO promoted with 10 wt% of Al, Co and Cu separately. The H2-TPR profile of pure NiO exhibits a broad peak centered at 435 °C, with a shoulder at a higher temperature of 502 °C. These peaks correspond to the reduction of NiO to metallic Ni (Ni2+→Ni0)41. SEM images of the NiO nanoparticles indicate a wide distribution size ranging from 50 to 700 nm. Incorporating 10 wt% of Al, Co, or Cu as promotors into NiO results in distinct TPR profiles compared to pure NiO, with additional reduction peaks and shifts in peak positions. The H2-TPR profile of 10% Al-NiO is dominated by a reduction peak at 495 °C, with additional shoulders observed at 385 and 573 and 683 °C. Ahmed et al.42 characterized the 60%Ni/Al2O3 catalyst by temperature-programmed reduction by H2 (H2-TPR). They observed that there are three broad reduction peaks at temperatures of 200–400, 400–500 and 600–700 °C. They suggested that the reduction peak between 200 and 400 °C can be attributed to the facile reduction of pure NiO phases, whereas the second reduction peak between 400 and 500 °C can be related to the reduction of both NiO with small particles and NiO contact with the aluminum. Lastly, the third peak of reduction at higher temperature of 600–700 °C is corresponding to the reduction of some NiAl2O4 species. Therefore, it can be suggested that the peaks at 385 °C and 495 °C are associated with the reduction of smaller NiO NPs and NiO contact with the Al, respectively, while the peak at 573 °C is likely attributed to reduction of possible formed NiAl2O4 species.

The H2-TPR profile of 10% Co-NiO shows a broad reduction peak centered at 477 °C, attributed to the reduction of NiO nanoparticle. No distinct reduction peak for Co° is observed, indicating that Co3O4 reduces to Co° (Co3O4→CoO→Co°) within the temperature range of 200–600 °C43. This suggests an overlap in the reduction processes of Co and Ni, resulting in a broad peak rather than distinct peaks for Co and Ni, as seen in Fig. 4.

Finally, the H2-TPR profile of 10% Cu-NiO shows two distinct reduction peaks around 208 °C and 385 °C, which are ascribed to the reduction of finely dispersed CuO NPs and NiO NPs, respectively44. It is evident that the reduction profile of NiO strongly dependent on the type of promoters.

XPS and Raman analysis

To identify the surface chemical composition of the examined materials, survey XPS spectra were acquired, and the results are shown in Fig. 5. The survey XPS spectrum of NiO (Fig. 5A (a)) is dominated by the characteristic peaks of Ni and oxygen45. For example, Ni 3p, Ni 3s, Ni LMM (Auger), Ni 2p, and Ni 2s peaks are observed, representing Ni metal. Additionally, one observes O 1s peak corresponds to oxygen and small peak at 285 eV assigned to carbon C 1s as a residual contamination during the material synthesis process. The survey spectra of NiO incorporated with 10 wt% of Al, Co, and Cu are also shown in Fig. 5A. Clearly, the spectra resemble that of pure NiO; however, traces of the incorporated Al, Co, and Cu ions can be observed. For example, the Al 2p peak at 72 eV overlaps with the Ni 3p peak at 66.5 eV, as seen in Fig. 5A(b); the Co 2p3/2 peak appears at 778.5 eV (Fig. 5A(c); and the Cu 2p3/2 peak is at 923.5 eV (Fig. 5A(d)). The elemental analysis of the samples investigated is summarized in Table 3. It should be mentioned that XPS is a surface-sensitive technique, therefore, when confirming the presence of the incorporated ions, the quantitative elemental composition should be interpreted with caution.

To resolve the oxidation states of NiO nanostructure upon the incorporation of Al3+, Co2+ and Cu2+ prompter ions, high-resolution spectra of Ni 2p and O 1s from the examined materials and results are depicted in Fig. 5 (B, C). The high-resolution Ni 2p spectrum of pure NiO exhibits a strong peak Ni 2p3/2 at 856 eV and shake-up at the higher B.E of 862 eV as seen in Fig. 5B (a). The peak Ni 2p3/2 can be deconvolved into two sup-peaks; at 853.8 eV and 855.6 eV correspond to Ni2+ and Ni3+, respectively46. The incorporation of Al³⁺, Co2+, and Cu²⁺ ions exert distinct effects on the Ni 2p₃/₂ spectrum. The incorporation of Al³⁺ and Co²⁺ results in an increase in the Ni²⁺ component in the Ni 2p₃/₂ spectrum, as shown in Fig. 5B(b), whereas Cu²⁺ incorporation does not significantly alter the Ni²⁺ signal. The increase in Ni²⁺ upon Al³⁺ doping is likely due to the charge imbalance caused by substituting a trivalent Al³⁺ ion into a divalent Ni²⁺ site, which is compensated by the reduction of Ni³⁺ to Ni²⁺ or the formation of oxygen vacancies. In the case of Co²⁺, the similar ionic charge allows substitution without formal charge imbalance; however, its redox-active nature and potential for Co³⁺/Co²⁺ transitions may influence local electron distribution, promoting partial reduction of Ni³⁺ to Ni²⁺. On the other hand, Cu²⁺ also a divalent ion, does not introduce charge imbalance and appears to have limited redox interaction under the tested conditions, resulting in minimal impact on the Ni oxidation state.

The O 1s spectrum for NiO material is shown in Fig. 5C(a), and it is fitted into three peaks: at 529.5 eV, assigned to nickel atom bonded to oxygen (Ni − O); at 531.2 eV (Odef) corresponding to oxygen defect/vacancy47; and at 532.6 eV (Oads), attributed to chemisorbed water on the surface48. The O 1s spectra of NiO incorporated with Al³⁺, Co²⁺, and Cu²⁺ ions are also presented in Fig. 5C (b, c,d). The incorporation of Al3+ induces an increase in the oxygen defect component (Odef) compared to that in pure NiO and NiO incorporated Co2+ and Cu2+ ions. This change in the oxidation state of NiO due to Al3+ incorporation may affect its performance as catalyst for methane decomposition.

Figure 6 shows the Raman spectra of pure NiO and NiO incorporated with 10% Al³⁺, Co²⁺, and Cu²⁺ ions. The Raman spectrum of pure NiO nanostructures exhibits four peaks at 352 cm⁻¹, 531 cm⁻¹, 693 cm⁻¹, and ~ 1067 cm⁻¹, which are assigned to the TO (1st order transverse optical), LO (1st order longitudinal optical), 2TO (2nd order transverse optical), and 2LO (2nd order longitudinal optical) modes of face-centered cubic NiO nanostructures, respectively49. The LO and 2LO modes are associated with the vibrations of Ni—O bonds. Furthermore, the sharp LO emission peak indicates the presence of nickel defects and/or the coexistence of Ni³⁺ and Ni²⁺ ions. Similar Raman modes of intrinsic NiO nanostructures have been reported by50, confirming the phase purity of the synthesized NiO nanostructures.

The Raman modes of NiO incorporated with 10% Al³⁺, Co²⁺, and Cu²⁺ ions resemble those of pure NiO and exhibit the characteristic TO, LO, 2TO, and 2LO Raman modes, as shown in Fig. 6 (b, c,d). However, variations in Raman band intensity, position, and width are observed when compared to the intrinsic NiO modes. For example, the intense LO mode in the spectra of 10% Cu-NiO suggests an increase in nickel defects48,49, which is consistent with the XRD and XPS results. The shift in band position and broadening is likely related to cation redistribution, as ions with different radii replace Ni2+, Ni3+ ions, affecting the vibrational frequencies and leading to mode broadening. Additionally, a new Raman mode at 945 cm⁻¹ is observed in the 10% Cu-NiO Raman spectra, which is assigned to a combination of TO and LO modes49.

Catalytic activity studies

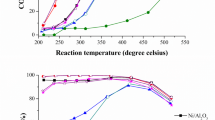

Figure 7 (a, b) demonstrates the methane conversion rate percentage and the rate of hydrogen formation as a function of time on stream (TOS) for direct decomposition of methane over pure NiO, 10% Al-NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO catalysts at temperature of 800 °C and gas flow rate of 20 mL/min.

From Fig. 7 (a), it is obvious that there is variation in the activity of the catalysts used in terms of percentage of methane conversion rate. The catalysts activity was in order of 10% Al-Ni > 10% Co-NiO > NiO > 10% Cu-NiO, which have achieved the highest percentage of methane conversion rate of 71.0, 49.50, 34.80 and 26.90%, respectively. Figure 7 (b) shows the hydrogen formation rate, which is consistent with the percentage of methane conversion rate over these catalysts. Similarly, the highest rates of hydrogen formation were 216.20, 161.70, 124.60 and 103.40 × 10− 5 mol H2 g− 1 min − 1 for the catalysts of 10% Al-NiO > 10% Co-NiO > NiO > 10% Cu-NiO, respectively.

The superior catalytic performance of 10%Al-NiO compared to 10%Co-NiO and 10%Cu-NiO in methane conversion can be attributed to a synergistic combination of textural, structural, and electronic properties influenced by the incorporated promoter Al3+ ions. BET analysis reveals that Al³⁺ incorporation significantly enhances the surface area and mesoporosity of NiO, as evidenced by the highest nitrogen uptake and broad pore size distribution, providing more accessible active sites for methane adsorption and activation. Additionally, H₂-TPR analysis indicates a multi-step reduction process for Al-NiO, with a major peak at 495 °C and additional peaks up to 683 °C, suggesting strong metal–support interaction and the formation of NiAl₂O₄ spinel species, which are known to improve thermal stability and redox behavior. XPS analysis supports these findings by showing an increase in the Ni²⁺ state and oxygen vacancies in 10% Al-NiO, due to charge compensation from Al³⁺ substitution, which enhances the electron density around active sites and facilitates methane activation. Raman spectroscopy further confirms structural modifications through shifts and broadening of LO and 2LO modes, indicating cation substitution and defect formation. In contrast, 10% Co-NiO shows moderate performance, with a relatively lower surface area and overlapping reduction peaks, indicating weaker interaction and less-prominent redox behavior. Although the 10% Cu-NiO material exhibits somewhat enhanced porosity, it demonstrates the lowest catalytic performance among the tested catalysts. This can be attributed to the early reduction of CuO at 211 °C, compared to NiO at 311 °C, leading to the premature formation of metallic Cu. The presence of metallic Cu may block Ni active sites or reduce their dispersion, thereby impairing the catalyst’s effectiveness in methane conversion. Furthermore, copper has a strong affinity for carbon, which can promote carbon deposition on the catalyst surface. As a result, the active Ni phase becomes encapsulated by carbon layers, further diminishing its catalytic activity51.

Table 4 presents a comparative summary of the catalytic performance of the synthesized catalysts for methane decomposition alongside relevant catalysts reported in the literature. As evident, the Ni-based catalysts promoted with 10% Al, Co, and Cu demonstrate significantly enhanced stability, with stable performance beyond 300 min, surpassing many of their supported counterparts. Notably, the 10% Al-NiO and 10% Co-NiO catalysts exhibit not only superior stability but also high methane conversion efficiencies, making them competitive with or superior to similar Ni-based catalysts reported previously. These findings highlight the potential of promoter-incorporated NiO nanostructures as effective and durable catalysts for methane decomposition. It should be noted that the experimental parameters for the same catalyst type/composition affect the catalyst performance of methane decomposition51,52.

In the current experiment, the NiO, 10% Al-NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO metal were used without reduction pr-treatment. During the methane decomposition reaction, CH4 reduces the oxide’s component in these catalysts, producing CO and CO2, which accompany hydrogen production. The production of CO and CO2 accompanying hydrogen production represents the reduction process of these catalysts61. Figure 8. (a, b) illustrates the CO and CO2 formation rate, associated with hydrogen production, against time on stream (TOS) at same condition of Fig. 7. From Fig. 8 (a, b), the CO and CO2 were formed throughout the reaction and obviously indicate that the reduction process of these catalysts is taking place. The highest formation rates of CO and CO2 were observed in the order of 10% Al-NiO > 10% Co-NiO > pure NiO > 10% Cu-NiO. This indicates that the highest reduction processes of these catalysts occurred in this order. As observed from the XPS and Raman analysis of the 10% Al-NiO catalyst, Figs. 5 and 6, it seems that the Al-doped NiO presumably highly facilitated the reduction process by forming more active metal sites compared to other catalysts. This result could be one of the reasons contributing to the high activity of the 10% Al-NiO catalyst.

(a) CO formation rate and (b) CO2 formation rate associated with the hydrogen production, with time on stream (min) at same conditions of Fig. 7.

Spent catalysts characterization

XRD studies

Figure 9. displays the XRD patterns of the spent NiO, 10% Al-NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO catalysts. The spaniel structure of these spent catalysts has completely changed compared to the fresh ones, Fig. 3. This is due to the reduction process that occurred during the reaction. On the other hand, it is noticeable that these spent catalysts had similar patterns which indicate the formation of graphitic carbon and metallic Ni. The diffraction peak at 2θ = 26.2° was appointed to the formation of crystalline graphitic carbon with (002) lattice plane, while there are three characteristic diffraction patterns attributed to metallic nickel which are evidently noted at ca. 44.5°, 52.1°, and 76.5° corresponding to (111), (200) and (220) lattice planes (JCPDS file: No. 03-1051)62.

Moreover, the XRD patterns did not show any obvious phases related to the incorporated metals of Al, Co and Cu, but the dominant phases were related to metallic nickel and graphitic carbon. As previously mentioned, the absence of these phases may be due to their fine distribution within the nickel matrix and/or their quantities being very small and falling below the detection limit of the X-ray instrument.

From Fig. 9 (b), a magnified view of the nickel (111) peak at 2θ of 44.5° is presented for the spent NiO, 10% Al-NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO catalysts. The position of this peak has been slightly shifted to higher 2θ values by incorporating Al, Co and Cu under the applied reaction conditions. From the literature, it has been reported that the formation of nickel alloys leads to a shift in the position of this peak to higher 2θ values54,63. Therefore, it can be suggested that the incorporation of Al, Co and Cu into nickel matrix resulted in the formation of alloys of Ni-Al, Ni-Co and Ni-Cu. Considering, the diffusion of carbon deposited throughout the lattice of these materials could be played a role in this shifting.

TGA studies

Figure 10 (a, b) shows the results of the TGA oxidation analysis, along with the corresponding first derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) profiles. Figure 10 (a) illustrates the weight loss of the spent NiO, 10% Al-NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO catalysts when subjected to high temperatures in the existence of air. It can be observed that all samples exhibited significant mass loss in the region beyond 500 °C which is due to the combustion of carbon deposited on the catalysts. From Fig. 10 (a), it is possible to estimate the amounts of carbon deposited on these catalysts. It was found that the weight percentages of carbon deposited were ca. 62.10, 72.60, 70.20 and 65.70 wt% spent NiO, 10% Al-NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO catalysts, respectively. Since the products of methane decomposition are only hydrogen and carbon, the amounts of carbon deposited are related to the activity of these catalysts. Thus, there is an agreement between the activity results of these catalysts shown in Fig. 7 and the amounts of carbon formed, which are shown in the results of TGA in Fig. 10 (a).

Figure 10 (b) displays the profiles of derivative weight alterations for the spent catalysts. These profiles can track the differences between the spent catalysts more evidently. It can be observed that each catalyst exhibited a single peak in the coke combustion region in the range of 500–770 °C, indicating the deposition of a single type of carbonaceous species in each catalyst.

It has been stated that there are three main forms of carbon formed during the decomposition of hydrocarbons over metallic catalysts: amorphous, graphitic sheets and filamentous64,65. Filamentous carbon is one of graphitic carbon types. It was found that the combustion region of amorphous carbon is at a temperature of approximately 330 °C, while the combustion region of graphitic carbon of all types is between 500 and 750 °C5. Therefore, amorphous carbon did not form over the catalysts used, while graphitic carbon was formed. This is confirmed by the absence of oxidation temperature peak of the amorphous carbon in region at 330 °C, and the appearance of combustion region peak of graphitic carbon in the range of 500–770 °C, as it is shown in the TGA analysis result, Fig. 10 (b). In addition, the XRD analysis results showed the appearance of graphitic carbon peak at 2θ = 26.2°, Fig. 9 (a).

Morphology analysis of spent catalysts

Figure 11 presents FE-SEM images of the spent NiO, 10% Al-NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO catalysts. From these images, it is evident that carbon filaments did not form over these spent catalysts except for the spent 10% Al-NiO catalyst. It was reported that the particle size of catalysts is a significant factor in the growth of carbon nanotubes, one of the types of carbon filaments, and catalysts with large particle sizes have been assumed to be ineffective, and both experimentally and theoretically studies showed that the formation rate of carbon filament can be increased with decreasing particle size of catalysts66. Noda et al.67 investigated the influence of reaction temperature on the formation of carbon nanotubes from the catalytic decomposition of methane over Ni/SiO2 catalyst. They observed that at a reaction temperature above 700 °C, Ni particles sinter to form large Ni particles, which reduce the formation of carbon filaments. Sun et al.68 investigated the effect of nickel particle size in Ni/Al2O3 catalyst on the growth of carbon filaments during the methane decomposition reaction. Their results revealed that the nickel catalyst with particle size of about 56 nm produced the highest yield of carbon filaments. Sakae et al.69 studied the effectiveness of a Ni/SiO2 catalyst for methane decomposition into carbon nanofibers and hydrogen. They noted that nickel particle diameters in range of 60–100 nm resulted in longer lifetime of Ni catalyst and highest yield of carbon nanofibers.

The estimated particle sizes as inferred from Fig. 11, were 2, (80 nm and 2 μm), 3 and 2 μm for NiO, 10% Al-NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO, respectively. Obviously, the particle sizes of spent catalysts are much larger than their fresh one as shown in Fig. 2. This is probably due to agglomeration and/or sintering of the catalyst particles under the applied reaction conditions, especially the temperature of 800 °C. Thus, it appears that the increase in microscale particles size played a role in the failure of carbon filament growth. However, this does not fully apply to the 10% Al-NiO catalyst, which showed carbon filaments growth because it has a small particle size of about 80 nm. It has been stated that the size of the catalyst particle plays a role in the activity and stability of the catalyst. Kim et al.70 investigated the activity of activated carbon as a catalyst for hydrogen production from methane decomposition. Their study included the effect of particle size of the activated carbon catalyst. They observed that as the particle size decreased, the catalyst activity increased. They suggested that this was because of mass transfer. That is, as the particle size increases, it will take more time for the methane molecules to reach the inner surface of the particle because of the limited rate of transport of the reactant, methane, and therefore, the overall reaction rate is lower. This suggestion was also supported by Abbas and co-worker71. Consequently, it can be suggested that the incorporation of Al3+ with NiO resulted in the formation of suitable particle size which improved the catalytic performance of NiO catalyst to produce hydrogen and carbon filaments.

In most of the cases studied, catalysts used in methane decomposition reactions are usually subject to deactivation, which is attributed to the formation of a carbon layer encapsulating the metal particles of the catalyst, which hinders the decomposition of methane72. Thus, the absence of carbon filaments on the surface of spent NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO catalysts, Fig. 11 (a, c,d), and the presence of graphitic carbon in the composition of these catalysts as shown in the XRD and TGA results, Figs. 9 and 10, indicate that graphitic carbon may have been formed on these catalysts either by deposition of graphitic carbon on their surface and/or by encapsulating of the metal catalyst particles with graphitic carbon layers. From the above, it can be suggested that the formation of graphitic carbon layers around the metal particles of the catalyst played a role in the low activity of NiO, 10% Co-NiO and 10% Cu-NiO catalysts compared to the10% Al-NiO catalyst.

Raman spectra

Figure 12 shows the Raman spectra of the spent NiO catalyst and NiO catalysts incorporated with 10% of Al³⁺, Co²⁺, and Cu²⁺ ions. The Raman spectra of all spent catalysts are dominated by three sharp peaks at ~ 1336, ~1570, and ~ 2679 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the D, G, and 2D bands of graphitic carbon, respectively73. This observation confirms the deposition of graphitic carbon nanostructures on the surface of the spent catalysts as a by-product of the thermo-catalytic decomposition of methane. The D band is associated with defects in the carbon structure, the G band corresponds to well-ordered carbon structures, and the 2D band represents the second-order overtone of the G band. The degree of disorder in the carbon structure is estimated from the ID/IG peak ratio74. A higher ID/IG ratio indicates a higher level of defects in the carbon structure and vice versa. The ID/IG ratio for the spent NiO catalyst is 0.29, which increases to 0.42 for carbon deposited on the spent 10% Al³⁺-NiO catalyst. Meanwhile, it decreases to 0.23 for carbon deposited on the spent 10% Cu²⁺-NiO catalyst. In other words, the use of Cu²⁺ ions as promoters in the NiO catalyst improves the quality of the deposited carbon during the thermo-catalytic decomposition of methane compared with pure NiO or NiO promoted with Al³⁺ and Co²⁺ ions.

Conclusion

In this study, NiO catalysts promoted with 10 wt% of Al³⁺, Co²⁺, and Cu²⁺ ions were successfully synthesized via a co-precipitation method and evaluated for methane decomposition. Among the three promoters, Al³⁺ showed the most significant enhancement in catalytic performance. The incorporation of Al³⁺ into the NiO lattice led to reduced crystallite size, increased surface area, higher oxygen vacancy concentration, and improved dispersion, all contributing to superior CH₄ conversion (71%) and H₂ production (216.2 × 10–5 mol H2 g–1 min− 1) at 800 °C. XPS confirmed the creation of charge imbalance and increased Ni²⁺ species, while Raman and SEM analyses revealed the formation of graphitic carbon nanostructures, especially on the Al-promoted catalyst. The findings demonstrate that Al³⁺ is an effective promoter for enhancing the physicochemical and catalytic properties of NiO in methane decomposition.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Raza, J. et al. Methane decomposition for hydrogen production: A comprehensive review on catalyst selection and reactor systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 168, 112774 (2022).

Weger, L., Abanades, A. & Butler, T. Methane cracking as a Bridge technology to the hydrogen economy. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 42, 720–731 (2017).

Vaidya, P. D. & Rodrigues, A. E. Glycerol reforming for hydrogen production: a review. Chem. Eng. Technol. 32, 1463–1469 (2009).

Kruger, P. Alternative Energy Resources: the Quest for Sustainable Energy (Wiley, 2006).

Alharthi, A. I. Pd supported on ZSM-5 with different ratios of si/al as catalysts for direct catalytic decomposition of methane. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 15, 567–573 (2021).

Sajjadi, S. M., Haghighi, M., Fard, S. G. & Eshghi, J. Various calcium loading and plasma-treatment leading to controlled surface segregation of high coke-resistant Ca-promoted NiCo-NiAl2O4 nanocatalysts employed in CH4/CO2/O2 reforming to H2. J. Hydrogen Energy. 47, 24708–24727 (2022).

Sajjadi, S. M., Haghighi, M. & Rahman, F. On the synergic effect of various anti-coke materials (Ca–K–W) and glow discharge plasma on Ni-based spinel nanocatalyst design for Syngas production via hybrid CO2/O2 reforming of methane. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 108, 104810 (2022).

Sajjadi, S. M., Haghighi, M., Rahman, F. & Eshghi, J. Plasma-enhanced sol-gel fabrication of CoWNiAl2O4 nanocatalyst used in oxidative conversion of greenhouse CH4/CO2 gas mixture to H2/CO. J. CO2 Util. 61, 10203 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Metal link: a strategy to combine graphene and titanium dioxide for enhanced hydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 41, 22034–22042 (2016).

Xie, G. et al. Graphene-based materials for hydrogen generation from light-driven water splitting. Adv. Mater. 26, 3820–3839 (2013).

Cao, S. & Yu, J. Carbon-based H2-production photocatalytic materials. J. Photochem. Photobiol C Photochem. Rev. 27, 72–99 (2016).

Tsoncheva, T. et al. dal Nanostructured copper-zirconia composites as catalysts for methanol decomposition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 165, 599–610 (2015).

Pinilla, J. L., de Llobet, S., Moliner, R. & Suelves, I. H2-rich gases production from catalytic decomposition of biogas: viability of the process associated to the co-production of carbon nanofibers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 42, 23484–23493 (2017).

Izquierdo, U. et al. Hydrogen production from methane and natural gas steam reforming in conventional and microreactor reaction systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 37, 7026–7033 (2012).

Guerra, E. L., Shanmugharaj, A. M. & Choi, W. S. Sung Hun ryu, thermally reduced graphene oxide-supported nickel catalyst for hydrogen production by propane steam reforming. Appl. Catal. Gen. 468, 467–474 (2013).

Al-Fatesh, A. S. et al. Rooney. Non-supported bimetallic catalysts of Fe and Co for methane decomposition into H2 and a mixture of graphene nanosheets and carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 48, 26506–26517 (2023).

Abdel–Fattah, E., Alharthi, A. I. & Alotaibi, M. A. Synergetic effects of al addition on the performance of CoFe2O4 catalyst for hydrogen production and filamentous carbon formation from direct cracking of methane. J. Alloys Compd. 997, 174982 (2024).

Alharthi, A. I. et al. Mg and Cu incorporated CoFe2O4 catalyst: characterization and methane cracking performance for hydrogen and nano-carbon production. Ceram. Int. 47, 27201–27209 (2021).

Alharthi, A. I. et al. Influence of Zn and Ni dopants on the physicochemical and activity patterns of CoFe2O4 derived catalysts for hydrogen production by catalytic cracking of methane. J. Alloys Compd. 938, 168437 (2023).

Alharthi, A. I. et al. Cobalt ferrite for direct cracking of methane to produce hydrogen and carbon nanostructure: effect of temperature and methane flow rate. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 27, 101641 (2023).

Alharthi, A. I. et al. Facile modification of Cobalt ferrite by SiO2 and H-ZSM-5 support for hydrogen and filamentous carbon production from methane decomposition. Int J Energy Res. 46, 17497 (2022)

Qian, J. X. et al. Lu zhou, methane decomposition to produce COx-free hydrogen and nano-carbon over metal catalysts: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 45, 7981–8001 (2020).

Hasnan, N. S. N. et al. Recent developments in methane decomposition over heterogeneous catalysts: an overview. Mater. Renew. Sustain. Energy. 9, 8 (2020).

Muhammad, A. F. S. et al. Recent advances in cleaner hydrogen productions via thermo-catalytic decomposition of methane: admixture with hydrocarbon. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 43, 18713–18734 (2018).

Bayat, N., Rezaei, M. & Meshkani, F. Methane decomposition over Ni-Fe/Al2O3 catalysts for production of COx-free hydrogen and carbon nanofiber. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 41, 1574–1584 (2016).

Rastegarpanah, A., Meshkani, F. & Rezaei, M. Thermocatalytic decomposition of methane over mesoporous nanocrystalline promoted Ni/MgO·Al2O3 catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 42, 16476–16488 (2017).

Al-Mubaddel, F. et al. H2 production from catalytic methane decomposition using Fe/x-ZrO2 and Fe-Ni/(x-ZrO2) (x = 0, La2O3, WO3) catalysts. Catalysts 10, 793 (2020).

Fakeeha, A. H. et al. Al-Fatesh. Methane decomposition over ZrO2-Supported Fe and Fe–Ni Catalysts—Effects of doping La2O3 and WO3. Front. Chem. 8, 1–13 (2020).

Awadallah, A. E. et al. Direct conversion of natural gas into COx-free hydrogen and MWCNTs over commercial Ni–Mo/Al2O3 catalyst: effect of reaction parameters. Egypt. J. Petroleum. 22, 27–34 (2013).

Anjaneyulu, C. et al. Influence of rare Earth (La, pr, nd, gd, and Sm) metals on the methane decomposition activity of Ni – Al catalysts. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 3, 1298–1305 (2015).

Alharthi, A. I. et al. Deciphering the influence of support in the performance of NiFe2O4 catalyst for the production of hydrogen fuel and nanocarbon by methane decomposition. Ceram. Int. 50, 37932–37943 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Engineering metal-support interaction to construct catalytic interfaces and redisperse metal nanoparticles. Chem. Catal. 3, 100768 (2023).

Thommes, M. et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87, 1051–1069 (2015).

Wei, J. et al. Highly improved ethanol gas-sensing performance of mesoporous nickel oxides nanowires with the stannum donor doping. Nanotechnology 29, 245501 (2018).

Lalea, A. et al. Highly active, robust and reusable micro-/mesoporous TiN/Si3N4 nanocomposite-based catalysts for clean energy: Understanding the key role of TiN nanoclusters and amorphous Si3N4 matrix in the performance of the catalyst system. Appl. Catal. B. 272, 118975 (2020).

. Rák, Z. et al. Evidence for Jahn-Teller compression in the (Mg, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) O entropy-stabilized oxide: A DFT study. Mater. Lett. 217, 300–303 (2018).

Chen, H. L. & Yang, Y. S. Effect of crystallographic orientations on electrical properties of sputter-deposited nickel oxide thin films. Thin Solid Films. 516, 5590–5596 (2008).

Irum, S. et al. Chemical synthesis and antipseudomonal activity of Al-Doped NiO nanoparticles. Front. Mater. Sci. 8, 673458 (2021).

Allali, M. et al. Synthesis and investigation of pure and Cu-Doped NiO nanofilms for future applications in wastewater treatment rejected by textile industry. Catalysts 12, 931 (2022).

Sharma, K. R. & Negi, N. S. Doping effect of Cobalt on various properties of nickel oxide prepared by solution combustion method. J. Supercond Nov Magn. 34, 633–645 (2021).

Zhao, B. et al. CO methanation over Ni/SiO2 catalyst prepared by Ammonia impregnation and plasma decomposition. Top. Catal. 60, 879–889 (2017).

Ahmed, W., Noor El-Din, M. R., Aboul-Enein, A. A. & Awadallah, A. E. Effect of textural properties of alumina support on the catalytic performance of Ni/Al2O3 catalysts for hydrogen production via methane decomposition. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 25, 359–366 (2015).

Ud Din, I., Shaharun, M. S., Subbarao, D. & Naeem, A. Synthesis, characterization and activity pattern of carbon nanofibers-based copper/zirconia catalysts for carbon dioxide hydrogenation to methanol: influence of calcination temperature. J. Power Sources. 274, 619–628 (2015).

Jirátová, K. et al. Cobalt Oxide Catalysts in the Form of Thin Films Prepared by Magnetron Sputtering on Stainless-Steel Meshes: Performance in Ethanol Oxidation. Vol. 9806 (Catalysts, 2019).

Salunkhe, P., AliAV, M. & Kekuda, D. Investigation on tailoring physical properties of nickel oxide thin films grown by Dc Magnetron sputtering. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 016427 (2020).

Liu, L., Zhang, H., Fang, L., Mu, Y. & Wang, Y. Facile Preparation of novel dandelion-like Fe-doped NiCo2O4 microspheres @ nanomeshes for excellent capacitive property in asymmetric supercapacitors. J. Power Sources. 327, 135–144 (2016).

An, C. et al. Porous NiCo2O4 nanostructures for high performance supercapacitors via a microemulsion technique. Nano Energy. 10, 125–134 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. Self-assembled 3D foam-like NiCo2O4 as efficient catalyst for lithium oxygen batteries. Small 12, 602–611 (2016).

Salunkhe, P., Muhammed Ali, A. V. & Kekuda, D. Investigation on tailoring physical properties of nickel oxide thin films grown by Dc Magnetron sputtering. Mater. Res. Express. 7, 016427 (2020).

Ravikumar, P., Kisan, B. & Perumal, A. Enhanced room temperature ferromagnetism in antiferromagnetic NiO nanoparticles. AIP Adv. 5, 087116 (2015).

Karimi, S. et al. Promotional roles of second metals in catalyzing methane decomposition over the Ni-based catalysts for hydrogen production: A critical review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 46, 20435–20480 (2021).

Meloni, E., Martino, M. & Palma, V. A short review on Ni based catalysts and related engineering issues for methane steam reforming. Catalysts 10, 352 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Preparation of bimetallic catalysts Ni-Co and Ni-Fe supported on activated carbon for methane decomposition. Carbon Resour. Convers. 3, 190–197 (2020).

Ray, K., Sengupta, S. & Deo, G. Reforming and cracking of CH4 over Al2O3 supported ni, Ni-Fe and Ni-Co catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 156, 195–203 (2017).

Torres, D., Pinilla, J. L. & Suelves, I. Co-, Cu- and Fe-Doped Ni/Al2O3 catalysts for the catalytic decomposition of methane into hydrogen and carbon nanofibers. Catalysis 8, 300 (2018).

Fakeeha, A. H. et al. Hydrogen production by catalytic methane decomposition over ni, co, and Ni-Co/Al2O3 catalyst. Pet. Sci. Technol. 34, 1617–1623 (2016).

de Almeida, R. M. et al. Preparation and evaluation of porous nickel-alumina spheres as catalyst in the production of hydrogen from decomposition of methane. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 259, 328–335 (2006).

Schwengbera, C. A. et al. Methane dry reforming using Ni/Al2O3 catalysts: Evaluation of the effects of temperature, space velocity and reaction time. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4, 3688–3695 (2016).

Lia, J. et al. Evolution of the Ni-Cu-SiO2 catalyst for methane decomposition to prepare hydrogen. Fusion Eng. Des. 125, 593–602 (2017).

Cunha, A. F. & Figueiredo, J. J. M. J. L. Methane decomposition on Ni–Cu alloyed Raney-type catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 34, 4763–4772 (2009).

Balakrishnan, M. et al. Hydrogen production from methane in the presence of red mud – making mud magnetic. Green. Chem. 11, 42–47 (2009).

Bora, D. K. et al. Fabrication of alkaline electrolyzer using ni@mwcnt as an effective electrocatalyst and composite anion exchange membrane. ACS Omega. 7, 15467–15477 (2022).

Pandey, D. & Deo, G. Promotional effects in alumina and silica supported bimetallic Ni–Fe catalysts during CO2 hydrogenation. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 382, 23–30 (2014).

Baker, R. T. K. Catalytic growth of carbon filaments. Carbon 27, 315–323 (1989).

Guo, J., Lou, H. & Zheng, X. The deposition of coke from methane on a Ni/MgAl2O4 catalyst. Carbon 45, 1314–1321 (2007).

Yu, Z., Chen, D., Tøtdal, B. & Holmen, A. Effect of catalyst Preparation on the carbon nanotube growth rate. Catal. Today. 100, 261–267 (2005).

Noda, L., Gonçalves, N., Valentini, A., Probst, L. & Almeida, R. Effect of Ni loading and reaction temperature on the formation of carbon nanotubes from methane catalytic decomposition over Ni/SiO2. J. Mater. Sci. 42, 914–922 (2007).

Yunfei, S. et al. Catalytic decomposition of methane over supported Ni catalysts with different particle sizes, Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 4, 814–820 (2009).

Takenaka, S., Kobayashi, S., Ogihara, H. & Otsuka, K. Ni/SiO2 catalyst effective for methane decomposition into hydrogen and carbon nanofiber. J. Catal. 217, 79–87 (2003).

Kim, M. H. et al. Hydrogen production by catalytic decomposition of methane over activated carbons: kinetic study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 29, 187–193 (2004).

Abbas, H. F. et al. Thermocatalytic decomposition of methane using palm shell based activated carbon: kinetic and deactivation studies. Fuel Process. Technol. 90, 1167–1174 (2009).

Latorre, N. et al. Development of Ni–Al catalysts for hydrogen and carbon nanofibre production by catalytic decomposition of methane. Effect of MgO addition. Top. Catal. 51, 158–168 (2008).

Yan, P., Zhang, K. & Peng, Y. Study of Fe2O3-Al2O3 catalyst reduction parameters and conditions for catalytic methane decomposition. Chem. Eng. Sci. 250, 117410 (2022).

Pimenta, M. A. et al. Studying disorder in graphite-based systems by Raman spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 1276–1290 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (PSAU/2024/01/78921).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Abdulrahman I. Alharthi: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing –original draft, Mshari A. Alotaibi: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Essam Abdel-Fattah: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. F. Qahtan: Methodology, Data curation. Osama A. Alshreef: Methodology, Data curation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alharthi, A.I., Alotaibi, M.A., Abdel‑Fattah, E.M. et al. The role of promoters on NiO catalysts for methane decomposition and hydrogen production. Sci Rep 15, 21448 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05727-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05727-1