Abstract

Leisure time and occupational physical activity (LTPA, OPA) seem to have opposite associations with some health outcomes. Few studies have investigated this for musculoskeletal pain. We investigated the association between (1) LTPA and OPA, and (2) combinations thereof, and persistent pain and number of pain sites, respectively, among adults. We used cross-sectional data from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. LTPA and OPA was measured using the Saltin-Grimby Physical Activity Level Scale. The outcomes were persistent pain and number of pain sites (past six months). Using hurdle models, the association between physical activity and the outcomes was expressed as odds ratios (OR) and incidence rate ratios. We included 2787 individuals. High LTPA was associated with decreased odds of persistent pain and lower number of pain sites, whereas high OPA was associated with increased odds of persistent pain and higher number of pain sites (e.g., high LTPA vs. inactive, OR: 0.38, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.26, 0.57; high OPA vs. sedentary work, OR: 2.94, 95% CI 1.66, 5.20). All LTPA-OPA-combinations indicated higher odds for persistent pain and higher number of pain sites when compared to moderate-to-high LTPA and sedentary work. This study highlights that not all physical activity may be beneficial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Physical activity is generally considered to be beneficial for musculoskeletal health, in particular leisure time physical activity (LTPA)1,2,3,4,5. This is reflected in clinical guidelines for the management of musculoskeletal disorders, such as low back pain and knee and hip osteoarthritis, which recommend patients to exercise and remain physically active6,7,8. In contrast, preventive workplace interventions often focus on reducing exposure to high occupational physical activity (OPA), which is considered to increase the risk of musculoskeletal pain in this setting3,9,10,11,12. Thus, LTPA and OPA appear to have opposite associations with musculoskeletal pain – commonly referred to as the physical activity health paradox13.

Most previous studies have investigated the effects of physical activity on musculoskeletal health focusing on physical activity either during leisure or during work4,5,8,12. This is problematic since the effect of LTPA on musculoskeletal pain may interact with the level of OPA. For example, a systematic review has indicated higher levels of LTPA to be more protective among individuals with low OPA than among individuals with moderate to high OPA14. It is, therefore, important to take both domains into account, and to investigate the combined effect of LTPA and OPA when analysing the association between physical activity and musculoskeletal pain.

A plausible explanation for the contrasting effects of LTPA and OPA on musculoskeletal health is differences in type and pattern of activity and the subsequent possibility for restitution12,15. LTPA is typically characterised by physical activity of relative short duration and high intensity with good opportunities for restitution whereas high OPA is typically accumulated over longer durations with lower intensity. OPA also often involves handling of heavy loads, repetitive work, or long durations of static and awkward body postures that are well-documented risk factors for musculoskeletal pain12,15,16. In contrast, well planned exercise programmes have been shown to be highly effective as treatment12. The risk of musculoskeletal pain is also influenced by psychosocial factors17,18 such as high work demands and low levels of influence at work12. Therefore even the same activity may have different effects depending on differences in work-related psychosocial factors.

Knowledge about the combined effect of physical activity during leisure and work on musculoskeletal pain is fundamental to develop physical activity recommendations and advise patients with musculoskeletal pain. We therefore aimed to investigate the association between (1) self-reported physical activity during leisure and work, and (2) combinations of LTPA and OPA, and persistent pain and number of pain sites, respectively, among adults in Denmark. In accordance with the physical activity health paradox, we expect the physical activity in leisure and work to have contrasting associations with persistent pain and number of pain sites.

Methods

Data source and study design

We used cross-sectional data from the fifth examination of the Copenhagen City Heart Study (CCHS) collected between October 2011 and February 201519. The CCHS is a dynamic cohort study consisting of adults (≥ 20 years) of the general population living in two parts of Copenhagen, Denmark. The study participants were randomly chosen from the Copenhagen Population Register using the Danish civil registration number19. In total, 9215 individuals were invited to participate in the fifth examination of which 4543 (49.3%) individuals participated.

Data collection

Study participants filled out a questionnaire and underwent a physical examination. In the current study, we only used data from the questionnaire, which included questions about socioeconomic status; general, physical, and mental health; symptoms and diseases including, but not limited to, questions about persistent or recurrent pain; diet; tobacco and alcohol consumption; medication use; physical activity; and healthcare seeking behaviour19.

The current analyses are registered at the University of Southern Denmark and the Danish Data Protection Agency (registration no.: 11.561). The National Committee on Health Research Ethics approved the data collection (approval no.: VEK: H-KF 01–144/01 31104). Participation was voluntary and in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the fifth examination of the CCHS.

Study population – eligibility criteria

We included all individuals from the fifth examination of the CCHS with data on (i) self-reported physical activity during leisure and work and (ii) presence of persistent musculoskeletal pain. Individuals who reported pain considered as non-musculoskeletal (i.e., limited to the stomach, genitalia, and/or headache) were not included.

Variables

Exposure

Physical activity during leisure and work was assessed with modified versions of the Saltin-Grimby Physical Activity Level Scale20,21. For LTPA, study participants were asked to “State your physical activity level during your leisure time (including transportation to and from work) within the last year”. Response options were:

-

“I. Being almost completely inactive or active in light physical activity for less than 2 h/week (e.g., reading, watching television, cinema)”,

-

“II. Light physical activity for 2–4 h/week (e.g., walks, cycling trips, light gardening, light calisthenics)”,

-

“III. Light physical activity for >4 h/week or strenuous physical activity for 2–4 h/week (e.g., brisk walking and/or fast cycling, heavy gardening, heavy calisthenics, where you sweat or get out of breath)”, and

-

“IV. Strenuous physical activity for >4 h/week or regular hard physical exercise and possibly competitions several times a week”.

The four LTPA levels are referred to as “inactive”, “low”, “moderate”, and “high”.

For OPA, study participants were asked to “State your physical activity level during work within the last year (also completed by housewives, students, and currently unemployed, while retirees without actual employment are asked to go to the next question)”. Response options were:

-

“I. Mainly sedentary work (e.g., paperwork/desk work; housewife/house husband without underage children but with domestic help)”,

-

“II. Sitting or standing, some walking (e.g., shop assistant, teacher; housewife/house husband, who wash and clean, without underage children)”,

-

“III. Walking, some lifting (e.g., postman; nursing staff; housewife/house husband, who wash and clean, with one or more underage children)”,

-

“IV. Heavy manual work (e.g., remover, concrete worker)”.

The four OPA levels are referred to as “sedentary”, “low”, “moderate”, and “high”.

Before investigating the combined effect of LTPA and OPA on the number of pain sites, we collapsed “moderate” and “high” LTPA and OPA due to a low number of observations in both high LTPA and high OPA. Also, to ease interpretation, we created a group variable with all combinations of LTPA and OPA using “moderate-high LTPA” and “sedentary work” as the reference group since we considered this to be the most protective combination of physical activity in relation to musculoskeletal pain. Specifically, because high LTPA has well-established beneficial effects on musculoskeletal health, and several studies report sedentary work to be protective against pain22,23,24, although suggested to be occupation-dependent24.

Outcomes

The outcomes were persistent pain and number of pain sites, which we defined as follows: Persistent pain was assessed with the question “Have you experienced persistent or recurrent pain within the last six months?” with response options “Yes” and “No”. Study participants answering “Yes” were asked in what body region(s) they experienced the pain. We then derived the number of pain sites by adding the number of painful body regions (neck, low back, shoulders, arms, wrists, fingers, hips, knees, ankles, and feet; count, maximum number = 10). Participants answering “No” to the experience of pain were assigned 0 pain sites.

Covariates

Age, sex, and level of education were used as covariates in the analyses. Age at date of physical examination was derived from date of birth. Sex was derived from the Danish civil registration number (by study staff). Level of education was used as an overall measure of socioeconomic status. It was assessed using the question “What education have you completed since you left municipal primary and lower secondary school?” with the following response options: “No [further] education”, “Short education (≤3 years with books)”, “Vocational or similar education (1–3 years)”, “Higher education (≥3 years, e.g., teacher, nurse or similar)”, and “University education”.

Statistical analysis

We described the study population using medians with first and third quartiles (Q1, Q3) and frequencies with percentages, overall and stratified by number of pain sites (categorised into 0, 1–2, ≥3 for descriptive purposes).

We compared characteristics of the study participants who fulfilled and did not fulfil the inclusion criteria using Wilcoxon rank sum test and Pearson’s Chi-squared test (p-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate differences between groups).

We investigated the association between self-reported physical activity and number of pain sites with hurdle models25. The hurdle model was chosen because (i) the outcome was zero-inflated and over-dispersed and (ii) the outcome data were generated through two processes (i.e., no pain vs. pain and ‘degree of widespread pain’). The model was specified for a binomial (zero-count model) and negative binomial distribution (zero-truncated count-model). In this context, the model estimates odds ratios (OR) and incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), which reflect the odds of persistent pain vs. no pain, and the relative difference in estimated number of pain sites for a given physical activity level compared to the reference level.

The following four models were used to investigate the association between LTPA and OPA, respectively, and number of pain sites.

-

1.

Unadjusted LTPA model

-

2.

Unadjusted OPA model

-

3.

Mutually adjusted model (including LTPA and OPA)

-

4.

Fully adjusted model (including LTPA and OPA, and adjustment for age, sex, and level of education)

We investigated if and how the association between LTPA and number of pain sites was dependent on the level of OPA using the combined LTPA and OPA group variable (nine groups) in an unadjusted model and a model adjusted for age, sex, and level of education.

We chose not to adjust for BMI and psychological factors as these variables are potential mediators and/or colliders in the investigated association. In all adjusted models, we tested for interactions between physical activity and sex and age, respectively (no evidence found), and for quadratic effect of age (no evidence found). We assessed the fit of the hurdle models using rootograms26 and quantile–quantile plots. No imputation method was used for missing values.

We estimated E-values to investigate how strong an unmeasured confounder would have to be to explain away any observed exposure-outcome association27. E-values were estimated for the adjusted ORs, IRRs, and the corresponding CIs closest to one (i.e., null effect)27. A large E-value means that substantial unmeasured confounding would be needed to explain away an effect estimate, and vice versa for a small E-value27.

As a sensitivity analysis, we added a requirement of a pain intensity of ≥3 to the outcome construct (average during the last 6 months, measured on a scale from 0–10, where 0 was “No pain” and 10 was “Worst pain imaginable”). This was done to investigate whether the association between physical activity and number of pain sites differed when limited to moderate-to-severe pain.

We conducted the analyses in R version 4.3.2 (R Core Team [2023]. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/). The hurdle models were fitted using the package ‘countreg’28. E-values were estimated using the package ‘EValue’27,29,30.

Results

In total, 2787 individuals fulfilled our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The median age was 52 (Q1: 37, Q3: 60) years and 55% were women. University education was the most common level of education (39%). About 7% were inactive during leisure time, while 36%, 47%, and 10% reported a low, moderate, and high level, respectively. In contrast, for OPA, 45% reported sedentary work, while 35%, 18%, and 2% reported a low, moderate, and high level, respectively (Table 1).

Among individuals with ≥3 pain sites, the median age was higher, and a higher proportion was women, compared to those with <3 pain sites. Furthermore, individuals with ≥3 pain sites were less active during leisure, but more active at work than those with <3 pain sites (Table 1).

A higher proportion of those who did not fulfil the inclusion criteria were women, were in general older, had a lower level of education, a lower LTPA level, and more pain sites compared to those included (Supplementary Table S1). The main reason for exclusion was missing data on OPA (n = 1618), but the majority of these were >65 years (n = 1412; i.e., reflecting retirement age).

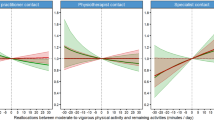

The odds of persistent pain decreased with 42–62% with increasing levels of LTPA (Table 2 and Fig. 2a). Conversely, the odds of persistent pain increased with 4–194% with increasing levels of OPA (Table 2 and Fig. 2a). The estimates were stable across all models for LTPA, while the estimated ORs were lower for OPA in the adjusted model compared to the unadjusted and mutually adjusted models (Table 2).

Adjusted odds ratios (OR) of persistent pain (a) and incidence rate ratios (IRR) of number of pain sites (b) for low, moderate, and high physical activity during leisure and work (vs. inactive and sedentary work, respectively). Vertical lines reflect 95% confidence intervals (CI). Model adjusted for age, sex, and level of education. LTPA, leisure time physical activity; OPA occupational physical activity.

For number of pain sites, the estimated IRR differed across the models for both LTPA and OPA (Table 2 and Fig. 2b). In the adjusted model, the estimated number of pain sites was 23%, 26%, and 23% lower among individuals with a low, moderate, and high LTPA level, respectively, compared to inactive individuals (Table 2 and Fig. 2b), whereas for OPA, in the adjusted model, the estimated number of pain sites was 21%, 19%, and 78% higher among individuals with a low, moderate, and high OPA level, respectively, compared to individuals with a sedentary work (Table 2 and Fig. 2b).

All combinations of LTPA and OPA indicated a higher OR for persistent pain compared to a moderate-to-high LTPA level and sedentary work (Table 3 and Fig. 3a). Specifically, the OR increased with decreasing LTPA across all OPA levels. This was most pronounced for combinations of LTPA and moderate-to-high OPA, except for the inactive LTPA and sedentary work combination that had the highest OR (Table 3 and Fig. 3a).

Adjusted odds ratios (OR) of persistent pain (a) and incidence rate ratios (IRR) of number of pain sites (b) for different combinations of physical activity during leisure and work (vs. moderate-high leisure time physical activity [LTPA] and sedentary work). Vertical lines reflect 95% confidence intervals (CI). Model adjusted for age, sex, and level of education. OPA, occupational physical activity.

A similar pattern was observed for number of pain sites, where the IRR increased with decreasing levels of LTPA across all OPA levels (Table 3 and Fig. 3b). The highest IRRs, for the combinations inactive LTPA and low and moderate-to-high OPA, respectively, indicated a 95–98% higher number of pain sites compared to the reference level (Table 3 and Fig. 3b). For unadjusted estimates, see Supplementary Table S2.

In general, the size of the E-values indicated that moderate unmeasured confounding would be needed to explain away the observed estimates. For LTPA and persistent pain, the E-values ranged from 1.95 to 2.63 (CI closest to 1: 1.48–1.98), and for OPA from 1.16 to 2.83 (CI closest to 1: 1.o0-1.90). For LTPA and number of pain sites, the E-values ranged from 1.92 to 2.04 (CI closest to 1: 1.00–1.43), and for OPA from 1.71 to 2.96 (CI closest to 1: 1.00–1.83) (Supplementary Table S3). E-values for the combinations of LTPA and OPA are presented in Supplementary Table S4.

In the sensitivity analysis where we applied a requirement of an average pain intensity of ≥ 3, the overall results did not change. However, some ORs and IRRs were larger while the corresponding CIs became wider, reflecting a stronger association with lower precision. This was most pronounced for high OPA with regards to persistent pain (adjusted OR: 3.92, 95% CI: 2.27, 6.79; Supplementary Table S5, S6). Additionally, for the inactive leisure and sedentary work combination, the OR for persistent pain was smaller compared to the main analysis (adjusted OR: 2.20, 95% CI 1.41, 3.45).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of adults, we found that increasing levels of LTPA was associated with decreased odds of persistent pain and lower number of pain sites whereas increasing levels of OPA was associated with increased odds of persistent pain and higher number of pain sites. When investigating the combined effect of LTPA and OPA, the mitigating effect of LTPA decreased with increasing levels of OPA. The findings support the existence of a physical activity health paradox with regards to both the presence of persistent pain and number of pain sites.

The findings of the current study agree with previous general population studies and systematic reviews reporting that LTPA is beneficial in relation to (chronic) low back pain and neck pain1,31,32,33,34, and an increased risk of pain from high levels of OPA3,10,11,32,34. However, there is a lack of studies where associations between combinations of LTPA and OPA and musculoskeletal pain are investigated. Commonly, researchers have adjusted for OPA without reporting the estimate1, have not differentiated between LTPA and OPA (i.e., using a sum of the two domains)35, or investigated ‘mixed’ physical activity groups that does not allow for differentiation of effects (e.g., heavy manual work or vigorous leisure activity)2. But the current results agree with the findings of one study investigating associations between combinations of LTPA and OPA34.

One proposed hypothesis for why LTPA and OPA have contrasting associations with health, including musculoskeletal pain, is differences in the type of physical activity, how it is performed, and under which conditions12,15. OPA and LTPA are typically diverse in the accumulated load, the temporal pattern of duration, intensity, and frequency, as well as in opportunities for restitution12,15. For example, LTPA is characterised by dynamic work involving large muscle groups, which benefits whole-body metabolism and cardiac function36. In contrast, OPA, is typically characterised by heavy lifting, pulling, pushing, prolonged standing and walking, repetitive work, working with hands at or above shoulder height, and working with the back twisted or bent forward (i.e., known risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders)12,15,16. The relative intensity and duration of physical activity during leisure and work relative to each other37, the subsequent period for restitution12, as well as psychosocial factors are also of importance17,18. As high OPA can involve excessive work demands combined with low levels of influence and control it may lead to increased psychological stress that predispose an individual to pain (i.e., the stress-diathesis model)17. Such contextual factors may therefore result in different effects even if the activity is similar. Although there are plausible explanations for the contrasting effects of LTPA and OPA on musculoskeletal health, studies investigating mechanisms with a comprehensive biopsychosocial approach are warranted.

Given the cross-sectional data, the risk of reversed causality should be kept in mind when interpreting the current results, since persistent pain may affect physical activity levels both at work and leisure. As a post hoc analysis, we investigated the association between persistent pain (exposure) and LTPA and OPA (outcomes), using a multinominal logistic regression model. This revealed ORs of similar size as in our main analysis, which highlights that the estimates should be interpreted as measures of association and not causal effects.

There were relatively few observations with high levels of LTPA and OPA, which resulted in lower precision in the estimates for these groups as reflected in the CIs. Also, when we investigated associations between combinations of LTPA and OPA and pain, we were forced to merge “moderate” and “high” due to too few observations at the cost of less detailed results.

For most estimates, the E-values indicated that the analyses were not robust to uncontrolled confounding. The highest E-values were found for high LTPA and OPA (adjusted OR: 0.4 and 2.9, respectively), where the strongest associations between physical activity and persistent pain were found. If an unmeasured confounder should be able to explain away these associations, it should be associated with both the exposure and outcome by an OR of 2.6- and 2.8-fold, respectively.

The prevalence of persistent pain in the current study (47%) is relatively high compared to other population based studies (21–51%)38,39,40. This may be explained by the longer time period in the pain question (i.e., pain within the past 6 months vs. 3-months and 14 days in other general population studies)38,39,41, and the relatively old study population as individuals ≥50 years appear to have a higher prevalence of chronic pain compared to younger individuals39,40.

The Saltin-Grimby Physical Activity Level Scale has limited validity and reliability when compared to accelerometer-based measurements of physical activity20,42,43,44. This results in inaccurate measurements that can bias regression estimates towards null (i.e., regression dilution bias). Also, there is a risk of differential misclassification given that individuals with pain may experience and rate their physical activity different (e.g., overestimate intensity and duration) than those without pain45. Additionally, the OPA-item seems to have a lower correlation with accelerometer-measured physical activity (total day) than the LTPA-item20,44, which may have led to a higher degree of misclassification of OPA compared to LTPA in the current study. However, we have found both the LTPA- and the OPA-item to be relatively good at differentiating between individuals’ time spent in sedentary behaviour and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity during leisure, and in sedentary behaviour, light-intensity physical activity, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity during work (Johansson et al., unpublished results). In addition, the OPA-item has been used as exposure measurement in several studies with consistent findings of associations with different health-related outcomes, such as long-term sickness absence13, ischemic heart disease46,47, major adverse cardiovascular events48, cardiovascular disease-specific and all-cause mortality48,49,50. These consistent findings suggest that the OPA-item (similar to the LTPA-item) is able to capture important aspects of OPA rather than reflecting random findings. Also, self-reported instruments may capture more subjective nuances than accelerometers (e.g., relative intensity), and can be used to assess physical activities that are more difficult to measure with accelerometers, such as weightlifting, pushing and pulling, and lifting.

Housewives were asked to answer the OPA-item while retired were asked to skip it. This is a limitation since retired individuals likely have similar “domestic” physical activity exposures as housewives (without underage children). We lack detailed data on occupation and related job exposures such as psychosocial and environmental factors.

The sensitivity analysis based on a requirement of a pain intensity of ≥ 3 on a numeric rating scare (0–10) showed similar results although some ORs and IRRs reflected a stronger association (but with lower precision) than in the main analyses. One potential explanation for this, may be that less severe pain have a lower impact on physical activity levels than moderate to severe pain. Individuals with a low pain intensity may, hence, introduce more noise in the data that results in weaker associations.

One of the two parts of Copenhagen from which the study population was randomly drawn is characterized by a high socioeconomic status. This likely explains the relatively high proportion of participants with a university education and is also reflected in the distribution of OPA (university education most often leads to jobs characterised by sedentary work). A higher proportion of study participants with low level of education would likely have led to a higher proportion of individuals reporting high OPA and a higher precision in the estimates.

Given that the participation rate in the fifth examination of the CCHS was about 50%, we acknowledge the risk of selection bias, which is important to consider when generalizing the results. Additionally, we excluded 1756 participants not fulfilling the inclusion criteria of which the majority (92%) lacked data on OPA. Most of these missing values were likely due to retirement as 87% of those with missing OPA were ≥65 years (retirement age in Denmark at the time of the data collection) and hence not part of our target population. This is also reflected in the higher median age, and may partly explain the higher proportion of low level of education and ≥3 pain sites compared to the included participants. Also, a healthy worker effect may be present in the current study as in all epidemiological studies based on working populations51. We hence acknowledge the risk of selection bias, which should be kept in mind when interpreting the results.

Conclusions

In this adult population, we found a beneficial association between LTPA and persistent pain and number of pain sites, but a detrimental association for OPA. The association between LTPA and persistent pain became less beneficial with increasing levels of OPA. This study highlights that not all physical activity may be beneficial, but we acknowledge the risk of reversed causality. The interplay between LTPA and OPA is important to consider when recommending physical activity to working adults.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data (General Data Protection Regulation, European Union), which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. The corresponding author may be contacted for further information about the data application process.

References

Fjeld, M. K. et al. Consistent pattern between physical activity measures and chronic pain levels: the Tromsø Study 2015 to 2016. Pain 164, 838–847. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002773 (2023).

Niederstrasser, N. G. & Attridge, N. Associations between pain and physical activity among older adults. PLoS ONE 17, e0263356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263356 (2022).

Øverås, C. K. et al. Association between objectively measured physical behaviour and neck- and/or low back pain: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pain 24, 1007–1022. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1551 (2020).

Shiri, R. & Falah-Hassani, K. Does leisure time physical activity protect against low back pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 prospective cohort studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 51, 1410–1418. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097352 (2017).

Alzahrani, H., Mackey, M., Stamatakis, E., Zadro, J. R. & Shirley, D. The association between physical activity and low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci. Rep. 9, 8244. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44664-8 (2019).

Foster, N. E. et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 391, 2368–2383. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30489-6 (2018).

Bannuru, R. R. et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartil. 27, 1578–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011 (2019).

Geneen, L. J. et al. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, Cd011279 (2017).

Cillekens, B. et al. How does occupational physical activity influence health? An umbrella review of 23 health outcomes across 158 observational studies. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1474–1481. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102587 (2020).

Shiri, R. et al. Risk factors for low back pain: A population-based longitudinal study. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 71, 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23710 (2019).

Heuch, I., Heuch, I., Hagen, K. & Zwart, J. A. Physical activity level at work and risk of chronic low back pain: A follow-up in the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. PLoS ONE 12, e0175086. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175086 (2017).

Søgaard, K. & Sjøgaard, G. Physical activity as cause and cure of muscular pain: Evidence of underlying mechanisms. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 45, 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1249/jes.0000000000000112 (2017).

Holtermann, A., Hansen, J. V., Burr, H., Søgaard, K. & Sjøgaard, G. The health paradox of occupational and leisure-time physical activity. Br. J. Sports Med. 46, 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2010.079582 (2012).

Prince, S. A. et al. The effect of leisure time physical activity and sedentary behaviour on the health of workers with different occupational physical activity demands: a systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 18, 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01166-z (2021).

Holtermann, A., Krause, N., van der Beek, A. J. & Straker, L. The physical activity paradox: six reasons why occupational physical activity (OPA) does not confer the cardiovascular health benefits that leisure time physical activity does. Br. J. Sports Med. 52, 149–150. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097965 (2018).

Lund, T., Labriola, M., Christensen, K. B., Bültmann, U. & Villadsen, E. Physical work environment risk factors for long term sickness absence: prospective findings among a cohort of 5357 employees in Denmark. BMJ 332, 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38731.622975.3A (2006).

Linton, S. J. & Shaw, W. S. Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Phys. Ther. 91, 700–711. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100330 (2011).

Engel, G. L. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 196, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460 (1977).

Schnohr, P. et al. The Copenhagen City Heart Study. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 3, H1–H83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90110-5 (2001).

Grimby, G. et al. The “Saltin-Grimby physical activity level scale” and its application to health research. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 25(Suppl 4), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12611 (2015).

Saltin, B. & Grimby, G. Physiological analysis of middle-aged and old former athletes. Comparison with still active athletes of the same ages. Circulation 38, 1104–1115. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.38.6.1104 (1968).

Kyriakidis, S. et al. The “sweet- and sour-spot” of occupational physical activity for back pain: a prospective accelerometer study among eldercare workers. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.4170 (2024).

Wiben, A., Skovsgaard, C., Søgaard, K., Schiøttz-Christensen, B. & Olsen, K. R. Tip of the iceberg: unveiling the impact on back disorders from cumulative physical job exposure and evaluating bias from the healthy worker effect using a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Eur. Spine J. 33, 2395–2404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-024-08212-x (2024).

Dzakpasu, F. Q. S. et al. Musculoskeletal pain and sedentary behaviour in occupational and non-occupational settings: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 18, 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01191-y (2021).

Zeileis, A., Kleiber, C. & Jackman, S. Regression models for count data in R. J. Stat. Softw. 27, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v027.i08 (2008).

Kleiber, C. & Zeileis, A. Visualizing count data regressions using rootograms. Am. Stat. 70, 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2016.1173590 (2016).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Ding, P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: Introducing the E-value. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-2607 (2017).

countreg: Count Data Regression v. R package version 0.2-1. (2022).

Smith, L. H. & VanderWeele, T. J. Bounding bias due to selection. Epidemiology 30, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000001032 (2019).

Mathur, M. B. & VanderWeele, T. J. Sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding in meta-analyses. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 115, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2018.1529598 (2020).

Heuch, I., Heuch, I., Hagen, K. & Zwart, J. A. Is there a U-shaped relationship between physical activity in leisure time and risk of chronic low back pain? A follow-up in the HUNT Study. BMC Public Health 16, 306. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2970-8 (2016).

Björck-van Dijken, C., Fjellman-Wiklund, A. & Hildingsson, C. Low back pain, lifestyle factors and physical activity: a population based-study. J. Rehabil. Med. 40, 864–869. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0273 (2008).

Nilsen, T. I., Holtermann, A. & Mork, P. J. Physical exercise, body mass index, and risk of chronic pain in the low back and neck/shoulders: longitudinal data from the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 174, 267–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr087 (2011).

Fjeld, M. K. et al. The physical activity paradox; exploring the relationship with pain outcomes. The Tromsø Study 2015–2016. Pain https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000003344 (2024).

Rhim, H. C. et al. Association between physical activity and musculoskeletal pain: an analysis of international data from the ASAP survey. BMJ Open 12, e059525. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059525 (2022).

Garber, C. E. et al. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43, 1334–1359. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb (2011).

Merkus, S. L. et al. An exploratory study on the physical activity health paradox-musculoskeletal pain and cardiovascular load during work and leisure in construction and healthcare workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 2751 (2022).

Rikard, S. M., Strahan, A. E., Schmit, K. M. & Guy, G. P. J. Chronic pain among adults — United States, 2019–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1 (2023).

Nahin, R. L., Feinberg, T., Kapos, F. P. & Terman, G. W. Estimated rates of incident and persistent chronic pain among US adults, 2019–2020. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2313563–e2313563. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13563 (2023).

Fayaz, A., Croft, P., Langford, R. M., Donaldson, L. J. & Jones, G. T. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 6, e010364. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364 (2016).

Christensen, A. I. et al. The Danish National Health Survey: Study design, response rate and respondent characteristics in 2010, 2013 and 2017. Scand. J. Public Health 50, 180–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820966534 (2020).

Ekblom, Ö. et al. Concurrent and predictive validity of physical activity measurement items commonly used in clinical settings– data from SCAPIS pilot study. BMC Public Health 15, 978. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2316-y (2015).

Gupta, N., Heiden, M., Mathiassen, S. E. & Holtermann, A. Prediction of objectively measured physical activity and sedentariness among blue-collar workers using survey questionnaires. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 42, 237–245. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3561 (2016).

Emaus, A. et al. Does a variation in self-reported physical activity reflect variation in objectively measured physical activity, resting heart rate, and physical fitness? Results from the Tromso study. Scand. J. Public Health 38, 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810378919 (2010).

Gupta, N., Heiden, M., Mathiassen, S. E. & Holtermann, A. Is self-reported time spent sedentary and in physical activity differentially biased by age, gender, body mass index, and low-back pain?. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 44, 163–170. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3693 (2018).

Allesøe, K., Søgaard, K., Aadahl, M., Boyle, E. & Holtermann, A. Are hypertensive women at additional risk of ischaemic heart disease from physically demanding work?. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 23, 1054–1061. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487316631681 (2016).

Allesøe, K. et al. High occupational physical activity and risk of ischaemic heart disease in women: the interplay with physical activity during leisure time. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 22, 1601–1608. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487314554866 (2015).

Holtermann, A., Schnohr, P., Nordestgaard, B. G. & Marott, J. L. The physical activity paradox in cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: the contemporary Copenhagen General Population Study with 104 046 adults. Eur. Heart J. 42, 1499–1511. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab087 (2021).

Holtermann, A. et al. Occupational and leisure time physical activity: risk of all-cause mortality and myocardial infarction in the Copenhagen City Heart Study. A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2, e000556. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000556 (2012).

Holtermann, A. et al. The interplay between physical activity at work and during leisure time–risk of ischemic heart disease and all-cause mortality in middle-aged Caucasian men. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 35, 466–474. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1357 (2009).

McMichael, A. J. Standardized mortality ratios and the “healthy worker effect”: Scratching beneath the surface. J. Occup. Med. 18, 165–168. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-197603000-00009 (1976).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all individuals participating in the fifth examination of the CCHS and the study staff contributing to the data collection.

Funding

Danish Regions, the Danish Foundation for Chiropractic Research and Post-graduate Education (R155-A3568-B2234 and R185-A4250-B2234).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MSJ developed the analysis plan with critical input from JH, MK, MTJ, AH, and KS. MSJ conducted the analyses and prepared all figures. MSJ, JH, and KS performed the initial data interpretation and drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Johansson, M.S., Hartvigsen, J., Korshøj, M. et al. The leisure time and occupational physical activity paradox in persistent musculoskeletal pain. Sci Rep 15, 21806 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05815-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05815-2