Abstract

This study presents a novel closed-loop bionic hand control system that integrates electromyography (EMG)-driven intent recognition with adaptive neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) to mitigate muscle fatigue and improve user performance. The proposed system features a 3D-printed bionic hand actuated by five independent servomotors, a custom-built electrical stimulator, and a real-time dual-classifier architecture. Muscle fatigue is detected using a Support Vector Machine (SVM) based on frequency-domain EMG features, while handgrip state is classified using a fuzzy logic controller. Experimental trials with 10 neurologically healthy participants demonstrated a 28.6% reduction in muscle fatigue and a 22% improvement in grip force consistency under hybrid control compared to EMG-only operation. The system achieved classification accuracies of 95.4% for fatigue detection and 93% for grip estimation. These results confirm the feasibility of hybrid EMG–NMES systems in enhancing functional performance, stability, and user experience in assistive applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The integration of NMES into bionic hand systems marks a substantial advancement in assistive and rehabilitation technologies, enabling individuals with upper-limb impairments to regain essential motor functions. Despite these innovations, muscle fatigue remains a critical impediment to sustained performance in electromyography (EMG)-based control systems. Fatigue degrades the quality of EMG signals and diminishes the precision of motor commands, ultimately compromising the effectiveness and usability of bionic prostheses.

Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES), a subclass of NMES, facilitates muscle contraction through externally applied electrical impulses delivered via superficial or implanted electrodes. The effectiveness of FES in eliciting functional hand movements is highly dependent on electrode configuration and channel count, as demonstrated by multi-pad systems capable of producing up to seven distinct grasp patterns, such as precision and power grasps1,2. These advanced configurations significantly expand the user’s range of motion, whereas single-channel systems are often limited to basic hand closure3,4. Most FES-based devices focus on palmar and lateral grasps to address common daily activities5. Aligning electrical stimulation with user intent enhances functional outcomes and promotes motor learning over time6. Nevertheless, key challenges remain—particularly in achieving high stimulation specificity and control accuracy, which are essential for restoring refined hand movements in patients with diverse impairments7.

Muscle fatigue further complicates the control of EMG-driven bionic hands by altering both the signal’s quality and the cortical mechanisms underlying motor command generation. Research indicates that fatigue disrupts inter-hemispheric cortical coherence while transiently enhancing coherence between the cortex and muscle post-fatigue, a dual effect that complicates signal interpretation and prosthetic control8,9. EMG median frequency serves as a key biomarker for fatigue and recovery, making it crucial for developing systems that adapt in real time to changes in muscle condition10,11. By analyzing both the amplitude and spectral characteristics of EMG signals, systems can dynamically adjust control strategies to preserve precision and stability under fatigue12.

Surface electromyography (sEMG) is the most widely adopted non-invasive technique for evaluating muscle fatigue, offering high-resolution insights into localized muscle performance13,14. Beyond sEMG, fatigue assessment protocols often include subjective evaluations and performance-based metrics, such as alternating fatiguing exercises with brief maximal contractions to track muscle endurance and recovery15,16. Associations between EMG parameters and perceived discomfort during prolonged manual tasks further support the multidimensional nature of fatigue evaluation17. These combined metrics provide a foundation for optimizing bionic hand performance under realistic conditions.

In addition to mitigating fatigue, FES offers several benefits for bionic hand control, including adjustable robotic assistance during muscle exhaustion and dynamic modulation of stimulation intensity to maintain muscle engagement throughout extended sessions18. This flexibility allows for optimized joint positioning and improved energy efficiency through reduced muscle co-contraction19,20. Real-time control of cocontraction patterns enhances movement fluidity and user comfort, contributing to the broader clinical relevance of FES systems in improving upper-limb functionality and autonomy21,22.

Despite these advantages, the integration of FES with EMG-based control remains technically demanding. Key challenges include the complexity of interpreting volitional EMG signals under variable fatigue conditions, and the presence of electrical artifacts generated by stimulation, which can obscure accurate signal acquisition23,24,25,26,27. These challenges must be addressed to realize the full potential of hybrid control systems for real-world assistive applications.

Several recent studies have explored FES–robotic or prosthetic system integration, demonstrating improvements in muscle activation and functional task execution1,2,6. However, many of these systems suffer from fixed stimulation protocols, lack of real-time adaptability, or require extensive manual calibration. To address these limitations, this work introduces a real-time closed-loop control architecture that incorporates a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier for muscle fatigue detection and a fuzzy logic classifier for grip state estimation. By dynamically modulating NMES parameters based on real-time physiological states, the system offers improved adaptability, control precision, and user-specific performance optimization.

This research investigates the impact of stimulation techniques on reducing muscle fatigue in EMG-controlled bionic hand systems with the overarching goal of enhancing functionality and user experience. We present a novel bionic hand fabricated using advanced 3D printing techniques and integrated with a custom-built stimulator. The system incorporates real-time EMG signal processing and dual classifiers to provide adaptive and fatigue-aware control. Experimental results from ten healthy participants demonstrate the system’s ability to significantly reduce muscle fatigue and improve grip force consistency, underscoring its potential in assistive and rehabilitative contexts.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Sect “Materials and methods” details the materials, hardware components, and methodology employed in the system design and implementation. Sect “Results and discussion” presents the experimental protocol, results, and performance analysis. Finally, Sect “Conclusions” concludes the study with a summary of key findings and outlines future research directions.

Materials and methods

Approach

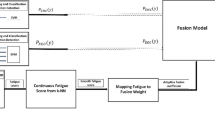

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of various neuromuscular stimulation techniques in mitigating muscle fatigue within EMG-controlled bionic hand systems, with a broader objective of enhancing both functional performance and user experience. To this end, we present a novel hybrid architecture that integrates a custom-designed, 3D-printed bionic hand with a bespoke electrical stimulator and a real-time dual-classifier control strategy.

Muscle fatigue and handgrip states are continuously estimated through the real-time analysis of sEMG signals. Fatigue detection is performed using a SVM classifier trained on frequency-domain features, while grip state estimation is handled by a fuzzy logic-based classifier leveraging amplitude-based indicators. The control unit receives and interprets the outputs of both classifiers, executing a dual control mechanism.

Specifically, based on the fatigue classification outcome, the system dynamically selects the appropriate NMES stimulation parameters and relays them to a dedicated control board that activates the electrical stimulator, targeting specific muscle groups. In parallel, the grip state classification is transmitted to the bionic hand controller, enabling accurate replication of the user’s intended grasp patterns. This closed-loop process operates iteratively, providing real-time adaptation to changes in muscle condition and user input.

The proposed architecture enables comparative analysis of bionic hand performance under different stimulation modes, including scenarios with and without active NMES assistance. By continuously adapting to the user’s physiological state, the system is designed to optimize motor function, reduce fatigue accumulation, and ensure seamless, intuitive integration between the user’s intent and the prosthetic actuation.

An overview of the developed approach is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Bionic hand

The bionic hand employed in this study (Fig. 2), previously introduced in our earlier work28, is a carefully engineered device that emulates the anatomical structure and kinematics of the human hand. Designed using SolidWorks CAD software, the hand strikes a deliberate trade-off between anatomical fidelity and functional performance to support both research flexibility and practical usability.

The mechanical structure offers five degrees of freedom (DoF), with each finger actuated independently by a dedicated servomotor. This configuration supports essential grasping patterns such as cylindrical and pinch grips, enabling functional hand movements suitable for assistive and rehabilitation contexts. The phalanges and palm components were fabricated using polylactic acid (PLA) via advanced 3D printing techniques, ensuring lightweight construction and mechanical robustness.

Tendon-like motion is simulated through the routing of high-tensile fishing line through the finger joints, allowing for naturalistic finger articulation. Finger re-extension is facilitated by return springs, while pulleys link each servomotor to its corresponding digit. The assembled device weighs approximately 350 g.

Control is achieved via an Arduino-based embedded system that receives classification results—relating to grip type and fatigue state—via serial communication from the LabVIEW-based processing unit. The modularity of the design supports rapid prototyping and customization, and it is fully compatible with wearable EMG acquisition systems and electrical stimulation modules. This makes it an ideal platform for real-time, closed-loop human-in-the-loop experimentation.

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation

NMES involves delivering controlled electrical impulses to skeletal muscles to induce tetanic contractions by activating lower motor neurons via peripheral nerve stimulation29. FES, a subset of NMES, is used to either substitute or augment voluntary muscle activity, facilitating functional movements in individuals with neuromotor impairments.

The effectiveness of NMES depends critically on three primary stimulation parameters: pulse frequency, pulse amplitude, and pulse width (duration). Pulse frequency—defined as the number of impulses delivered per second—is typically set between 30 and 80 Hz to elicit smooth and sustained muscle contractions29. Frequencies at the higher end of this spectrum can maximize contraction strength but also increase the risk of muscle fatigue30. Lower frequencies are less fatiguing but may fail to achieve functional contractions. For comfort and safety, a consistent frequency is generally employed to avoid sudden transitions that could cause discomfort or irregular contractions31.

Pulse amplitude, measured in mA, and pulse width, measured in μs, together determine the intensity and spread of muscle activation. Higher amplitudes and longer durations recruit more motor units, thereby increasing contraction force29. While amplitude and pulse width are usually kept constant during a stimulation cycle, they can be modulated in adaptive systems based on user tolerance and therapeutic goals.

In this study, a custom-designed electrical stimulator was developed in-house for precise and flexible control32. The circuit and printed circuit board (PCB) were designed and simulated using Proteus software. The stimulator supports three predefined stimulation modes tailored for rehabilitation scenarios:

-

Pain relief mode (80 Hz): Delivers continuous stimulation at 80 Hz to produce strong, sustained contractions optimized for muscle activation.

-

Relax mode (3 s 80 Hz / 3 s 2 Hz): Alternates between high-frequency stimulation and low-frequency vibration to promote circulation and reduce post-activation fatigue.

-

Massage mode (3 s 80 Hz / 3 s 0 Hz): Alternates between active stimulation and rest, producing a rhythmic muscle-pumping effect that simulates a therapeutic massage.

The choice of these modes and parameters was informed by established NMES protocols in the literature29,33 and refined through pilot testing with three healthy participants to ensure comfort, safety, and effective muscle engagement. In particular, the massage mode was selected as the default for fatigue mitigation trials due to its dynamic stimulation profile and user-reported comfort.

The system allows therapists to manually activate any of the stimulation modes. Additionally, the massage mode can be automatically triggered by the control system based on real-time fatigue assessments provided by the SVM classifier, enabling a responsive and adaptive rehabilitation experience.

EMG acquisition and preprocessing

Acquisition

EMG signals were acquired using an open-source, eight-channel EMG armband34 capable of capturing high-resolution muscle activity data. For this study, two key muscles of the forearm were targeted: the Flexor Carpi Radialis (FCR), known as wrist flexor (WF), and the Extensor Carpi Radialis Longus (ECRL), known as wrist extensor (WE). These muscles were selected due to their direct involvement in common grasping movements such as cylindrical and pinch grips. Although the armband supports eight channels, only these two were utilized to streamline data processing and reduce computational load while maintaining functional relevance.

The EMG armband was interfaced with a National Instruments sbRIO-9637 real-time acquisition board via a serial-to-USB TTL converter, ensuring efficient signal transmission with minimal latency. This configuration provided a robust and scalable platform for integrating EMG signals into the hybrid control framework. Figure 3 illustrates the anatomical placement of the EMG sensors over the FCR and ECRL muscles, which were the primary sites for signal acquisition.

The raw EMG signals were initially sampled at 100 kHz to capture fine-grained temporal dynamics and accommodate subsequent high-fidelity filtering. However, to align with real-time processing constraints, the data was downsampled to an effective rate of 10 kHz per channel. This balance enabled accurate signal acquisition while maintaining computational efficiency and system responsiveness35.

Signal quality was further enhanced through a two-stage filtering process implemented using LabVIEW’s Digital Filter Design module. A 10–500 Hz Butterworth bandpass filter was employed to isolate the frequency band relevant to surface EMG, while a 50 Hz notch filter was applied to suppress power line interference. The amplification gain was set to 1000 to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio during acquisition.

This acquisition and preprocessing pipeline ensured that the EMG data fed into the classifiers retained sufficient temporal resolution and spectral integrity, thereby supporting accurate real-time classification of fatigue states and handgrip intentions.

EMG processing for muscle fatigue estimation

A variety of signal processing and pattern recognition techniques, including feature extraction and classification, have been developed to extract meaningful features from EMG signals for the purpose of muscle fatigue analysis. Among these, frequency-domain and time–frequency-domain metrics, particularly those derived from Power Spectral Density (PSD) analysis, are widely recognized for their effectiveness in capturing fatigue-related signal changes.

In this study, two key spectral features were selected as inputs for the SVM classifier: Mean Frequency (MNF) and Mean Power (MNP). These features are commonly employed in fatigue estimation due to their sensitivity to muscle activation dynamics36.

The MNF is defined as the weighted average of the frequency components within the EMG power spectrum and is calculated using Eq. (1):

where \({f}_{j}\) is frequency of the spectrum at frequency bin j, \({P}_{j}\) is the EMG power spectrum at frequency bin j, and M is length of the frequency bin.

The MNP quantifies the average energy distributed across the EMG power spectrum and is computed as shown in Eq. (2):

For both features, the PSD was computed using a 1 Hz frequency resolution, which enabled high-fidelity estimation within the relevant EMG bandwidth of 10–500 Hz. This resolution ensures fine-grained tracking of frequency shifts associated with fatigue-induced spectral compression.

To evaluate signal stability, the MNP values were monitored across successive isometric grasping trials. A reduction in variability of MNP over time was interpreted as evidence of consistent muscle activation, thereby serving as a proxy for neuromuscular performance stability during task execution.

EMG processing for handgrip state estimation

In this component of the system, feature extraction is applied to EMG signals acquired from two channels: FCR and ECRL, rather than from a single channel as in previous studies28. This dual-channel approach enables more accurate representation of muscular activity and enhances the fidelity of handgrip state replication in the bionic hand.

Two distinct features are extracted for separate purposes: one to detect movement onset and another to estimate handgrip strength, both of which are used to drive the fuzzy logic controller.

To initiate the grasping sequence, Mean Absolute Value (MAV) is used as the onset detection feature. MAV is widely adopted in EMG processing for its simplicity and effectiveness in representing muscle activation amplitude37,38. It quantifies the average of the absolute values of the EMG signal amplitude over a specified time window, as defined in Eq. (3):

where \({X}_{i}\) represents the ith sample of the EMG signal segment, and N is the total number of samples in that segment. The use of MAV enhances the responsiveness of the system to initiation of muscle activity and facilitates timely activation of the fuzzy classifier.

Once the fuzzy logic classifier is activated, a second feature—Root Mean Square (RMS)—is employed to estimate handgrip strength. RMS is one of the most widely used metrics in EMG signal processing due to its ability to capture the energy content of the signal, particularly during constant-force, non-fatiguing contractions. These contractions are typically modeled as amplitude-modulated Gaussian random processes39. RMS has been extensively utilized for predicting grip force levels, making it a reliable indicator for estimating muscular effort39. The mathematical formulation of RMS is presented in Eq. (4):

where \({X}_{i}\) is the ith sample in the signal window, and N denotes the number of samples over which the root mean square is computed.

SVM-based muscle fatigue estimation

Physical exhaustion is a common manifestation of several chronic and neurological conditions, including musculoskeletal disorders, multiple sclerosis, stroke, and persistent insomnia. Despite its prevalence, muscle fatigue remains difficult to objectively quantify due to its inherently subjective nature, varying widely in intensity based on individual physiological states and psychological factors such as mood and motivation. This complexity poses significant challenges in accurately predicting fatigue onset and progression.

To address this, we developed and deployed an SVM-based classifier within the LabVIEW environment to estimate muscle fatigue in real time. The model utilizes two features: MNF and MNP, extracted from the EMG signals as detailed in the previous section. Figure 4 illustrates the complete workflow for fatigue classification using the SVM model.

The classifier was implemented using the LabVIEW Analytics and Machine Learning Toolkit, which extends LabVIEW’s capabilities to include model training, classification, and anomaly detection. This toolkit supports deployment on both NI Linux Real-Time and Windows platforms, enabling real-time data acquisition, processing, and adaptive classification without additional external hardware.

SVMs are particularly well-suited for EMG-based fatigue estimation due to their robustness in handling high-dimensional, non-linear datasets. They effectively identify complex patterns in EMG signals, allowing for accurate discrimination between fatigue and non-fatigue states. This classification is critical for real-time decision-making in assistive and rehabilitation technologies. Furthermore, SVMs exhibit strong generalization capabilities, making them adaptable to inter-subject variability and different experimental contexts—key requirements for deployment in personalized rehabilitation systems.

To construct and train the SVM classifier, a dataset was assembled using EMG recordings from 76 neurologically healthy participants performing repetitive handgrip exercises. For each trial, MNF and MNP features were extracted from segmented EMG windows and labeled as either ‘fatigue’ or 'non-fatigue’ based on visual inspection and spectral analysis thresholds consistent with established clinical guidelines40,41. The dataset was randomly partitioned into 80% for training and 20% for testing. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using a fivefold cross-validation strategy, optimizing kernel type (Radial Basis Function, RBF) and regularization parameter (C).

Classifier performance was evaluated using standard metrics, including classification accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC). The final model achieved 95.4% accuracy on the test set, demonstrating excellent generalization to unseen data. Importantly, the model was successfully deployed in real time within the LabVIEW environment, making it suitable for continuous monitoring and adaptive control in fatigue-aware prosthetic systems.

Fuzzy classifier for handgrip state estimation

To estimate the user’s handgrip state, a fuzzy logic-based classifier was implemented using the LabVIEW platform and its PID and Fuzzy Logic Toolkit. The classifier processes four EMG-based input features—RMS and MAV values extracted from the FCR and ECRL muscles, yielding a single output representing the predicted handgrip level. The system structure is illustrated in Fig. 5.

The fuzzy inference system operates in three stages: fuzzification, inference, and defuzzification. In the first stage, normalized input signals are mapped to linguistic terms using five Gaussian-shaped membership functions: very low, low, medium, high, and very high. These functions were empirically designed based on calibration trials across multiple participants and were optimized to reflect increasing levels of muscle activation. The shape and positioning of the membership functions are shown in Fig. 6.

The fuzzy rule base then combines these inputs to infer the user’s grip state. The output is discretized into one of three grip levels: Relaxed, Moderate Grip, or Strong Grip. These levels are translated into commands to actuate the bionic hand accordingly. The membership functions associated with the output variable are depicted in Fig. 7.

The use of Gaussian membership functions, rather than triangular ones used in prior implementations28,42, ensures smoother interpolation and higher classification granularity. Their overlap was carefully tuned to improve classification robustness under signal variability. Although a formal comparison of membership function types was not conducted, the current configuration achieved a classification accuracy of 93%, validating its effectiveness in interpreting EMG signals. Future efforts will focus on adaptive tuning of the membership functions to personalize performance across users with varying neuromuscular profiles.

Participants

This study involved 10 neurologically healthy volunteers (four female; age range: 23–31 years), selected to ensure a representative and homogeneous sample for evaluating the proposed system. Each participant completed two experimental sessions on separate days to assess the consistency and repeatability of outcomes.

Prior to participation, all individuals provided written informed consent after receiving a detailed explanation of the study’s objectives, procedures, and potential risks. The experimental protocol was conducted in full compliance with international ethical standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki, and was formally reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Sfax (Approval No. 11/2024; Protocol Code: USF2024-0023).

This approval affirms the study’s commitment to ethical research conduct, ensuring the protection of participants’ rights, safety, and well-being throughout the research process.

Flowchart of the control system

The control architecture of the proposed system follows a closed-loop cycle designed for real-time operation. As shown in Fig. 8, the process begins with system initialization, during which hardware components are activated and communication protocols are established. Subsequently, EMG signals are acquired and processed through feature extraction modules that compute both time- and frequency-domain characteristics relevant to fatigue and handgrip estimation.

These features are then input into two classifiers: a SVM for fatigue detection and a fuzzy logic system for grip state estimation. Based on the classifier outputs, the control unit generates appropriate commands either to trigger NMES or to actuate the bionic hand. The system then loops back to acquire new EMG data, enabling continuous monitoring and dynamic adaptation to changes in the user’s physiological state.

This real-time iterative loop ensures responsiveness, personalization, and functional integration between the user’s neuromuscular input and the assistive robotic output.

Results and discussion

The proposed EMG-controlled bionic hand system was experimentally validated to evaluate its effectiveness in mitigating muscle fatigue and improving grip control reliability. Validation was conducted through technical performance assessments and trials involving human participants, focusing on both physiological and subjective outcomes.

Experimental setup and procedure

Ten neurologically healthy participants (aged 23–31) took part in the study, performing a series of repetitive isometric handgrip tasks under two distinct control conditions:

-

1.

EMG-only control (referred to as “bionic hand alone”) where hand movement was triggered solely by EMG-based classification, without stimulation.

-

2.

Hybrid control where EMG classification was augmented with NMES to reduce muscle fatigue and support movement.

In both conditions, participants interacted with the same bionic hand system, and their responses were logged for comparative analysis. Each participant completed two experimental sessions on different days to assess intra-subject repeatability and mitigate fatigue carryover effects.

The experimental protocol was structured into three key phases:

-

Familiarization: Participants were introduced to the system, including the bionic hand and NMES interface, to ensure they were comfortable with the experimental environment and equipment.

-

Calibration: Baseline EMG recordings were obtained under two conditions: complete muscle relaxation and maximal voluntary contraction (MVC). These recordings were used to normalize extracted EMG features for each individual.

-

Task Execution: Participants performed 10 grasp cycles under each control condition. Each cycle consisted of a 5-s isometric handgrip, followed by a 10-s rest period, simulating functional task repetitions with progressively increasing fatigue. Both control modes (EMG-only and hybrid) were executed in a counterbalanced order across participants to minimize order effects.

To ensure data consistency and reduce variability:

-

Electrode placement, acquisition parameters, and system settings were kept constant across sessions.

-

Each session was supervised by the same experimenter.

-

Instructions were standardized across participants.

After completing the sessions, participants were asked to evaluate their experience using a brief 3-item Likert-scale questionnaire of p < 0.05 (1–10) assessing:

-

Perceived comfort during system use,

-

Perceived fatigue reduction when using hybrid control versus EMG-only,

-

Overall usability of the system in an assistive or rehabilitative context.

Statistical analysis was conducted using paired-sample t-tests to compare performance between EMG-only and hybrid control conditions. A significance level was used to determine statistically meaningful differences. Subjective evaluation results from this questionnaire will be presented and discussed in Sect “Performance metrics and discussion”, along with supporting visual data in Fig. 15.

Performance metrics and discussion

Figure 9 summarizes the system’s performance across the two experimental conditions (EMG-only vs. Hybrid control), based on classification accuracy and task completion time. Classification accuracy was assessed using the methodology described in Sects. “SVM-based muscle fatigue estimation” and “Fuzzy classifier for handgrip state estimation”, where two classifiers, SVM for fatigue state detection and fuzzy logic for handgrip estimation, were trained on EMG-derived features. The SVM achieved an accuracy of 95.4% in distinguishing between fatigue and non-fatigue states, outperforming prior EMG-based systems such as13, which reported 90%. The hybrid system’s improved performance is likely due to its ability to incorporate adaptive NMES feedback, enhancing classifier robustness under varying muscle conditions.

Similarly, the fuzzy classifier delivered an accuracy of 93% in estimating grip state, which marks a 6% improvement over previous implementations that used triangular membership functions (87%, see33). This supports the decision to adopt Gaussian membership functions in the current design for smoother transitions and better classification granularity.

Task completion time measured from EMG onset to the end of the grip cycle over 10 repetitions was 15.3% longer under the hybrid controller compared to the EMG-only condition. Despite this delay, the increased task duration was justified by significantly enhanced muscle fatigue resistance and grip force stability. This is particularly relevant in assistive and rehabilitation contexts, where priorities often shift from speed to reliability, muscular endurance, and long-term usability, a viewpoint also supported by25,43.

To assess muscle fatigue progression, Fig. 10 presents the decline in the MNP feature extracted from EMG signals. The hybrid system reduced fatigue progression by an average of 28.6%, calculated based on the slope of MNP decline across task repetitions (see Sect.“EMG acquisition and preprocessing”). This result aligns with31, who reported 25–30% fatigue reductions using NMES-assisted systems, validating the hybrid system’s capacity to maintain neuromuscular performance.

Moreover, the hybrid system improved force consistency by 22%, inferred from the reduced variability in RMS values, which correlate with grip strength as supported by39. Although absolute grip force was not measured using force sensors, RMS has been validated in the literature as a reliable proxy for estimating muscle contraction intensity.

Figure 11 depicts grip force variability via box plots, revealing a narrower interquartile range for the hybrid condition. This confirms that the hybrid controller produces more stable and repeatable grip outputs, crucial for tasks requiring precision and safety.

Energy efficiency was also improved. NMES was found to reduce co-contractions by 18%, effectively conserving energy across repetitive trials. This aligns with findings from19, who achieved 20% energy savings using optimized NMES parameters.

Figure 12 displays a representative set of raw and processed EMG signals before and after applying RMS and MAV feature extraction. These visualizations support the validity of our preprocessing pipeline and the features’ relevance for classification, as detailed in Sects. “EMG acquisition and preprocessing” and “Fuzzy classifier for handgrip state estimation”.

To evaluate classification performance, a confusion matrix was employed (Fig. 13). True Positive and True Negative rates dominate, with minimal false classifications, confirming the high reliability of the SVM in detecting fatigue states during real-time control.

Regarding stimulation parameters, Fig. 14 illustrates the impact of stimulation frequency on fatigue reduction. Fatigue mitigation improved with increased NMES frequency, peaking at 70% reduction at 80 Hz, while lower frequencies (e.g., 2 Hz) were significantly less effective. The optimal therapeutic window lies between 60–80 Hz, balancing effectiveness with user comfort.

Subjective feedback was obtained via a 3-item Likert-scale questionnaire, as shown in Fig. 15. The majority of participants reported high satisfaction with fatigue reduction (90%), followed by usability (88%), and comfort (85%). The slightly lower comfort rating may stem from transient discomfort associated with higher NMES frequencies. This feedback validates the hybrid system’s design goals, while highlighting areas for ergonomic refinement.

To assess statistical significance, paired-sample t-tests were conducted across three key metrics:

-

Task duration: Slight increase, not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

-

Fatigue index (MNP slope) and subjective fatigue reduction: Significant improvements in favor of the hybrid control (p < 0.05).

-

Comfort and usability scores: No significant difference between modes (p > 0.1), indicating general acceptance.

In terms of computational performance, real-time execution was achieved on the sbRIO-9637 platform, with average CPU usage < 65% and memory consumption < 50 MB, supporting the system’s feasibility for embedded applications.

Finally, the system responded about 140 to 150 ms after the muscle signal was detected, this includes the time needed to read the EMG signal, process it, classify it, and then activate the bionic hand or stimulation. This amount of delay is considered acceptable for real-time control in rehabilitation and assistive systems (as shown in references23,25). It’s short enough that users did not notice any lag during operation.

To evaluate classifier performance, a confusion matrix was used to assess the accuracy of the SVM classifier in distinguishing between fatigue and non-fatigue states (Fig. 13). The results demonstrate that True Positives (correctly identified fatigue states) and True Negatives (correctly identified non-fatigue states) dominate, indicating high classification accuracy. In contrast, False Positives (non-fatigue mislabeled as fatigue) and False Negatives (missed fatigue cases) were minimal, confirming the classifier’s reliability and its suitability for real-time system adaptation.

To assess the effectiveness of stimulation frequency, Fig. 14 illustrates the relationship between NMES frequency (Hz) and fatigue reduction (%). The results show that fatigue reduction improves with higher stimulation frequencies, reaching up to 70% at 80 Hz. In contrast, lower frequencies such as 2 Hz were considerably less effective, likely due to inadequate muscle activation. While 80 Hz was the most effective, it may approach the upper threshold of user comfort and safety. Thus, an optimal stimulation range appears to lie between 60–80 Hz, offering a practical balance between efficacy, comfort, and system efficiency.

Finally, to capture user perception of system performance, a three-item Likert-scale questionnaire was administered. Figure 15 summarizes user feedback regarding comfort, fatigue reduction, and overall usability. Participants reported a high perceived fatigue reduction (90%), aligning with the objective EMG performance data. Slightly lower ratings for usability (88%) and comfort (85%) may reflect minor concerns related to system complexity or NMES-induced discomfort, particularly at higher stimulation frequencies. Overall, users expressed strong satisfaction with the hybrid system, especially for its ability to reduce fatigue. Nonetheless, there is potential for improvement in comfort through ergonomic refinements and adaptive tuning of stimulation parameters.

The results were benchmarked against recent studies in EMG-controlled bionic systems to contextualize performance. Signal stability was evaluated by computing the standard deviation of MNP values across repeated tasks. The hybrid control system exhibited reduced MNP variability (8%) compared to the standalone EMG system (12%), indicating more consistent muscle activation and greater resistance to fatigue under NMES support.

In terms of classifier adaptability, the use of Gaussian membership functions in the fuzzy logic classifier resulted in higher handgrip state estimation accuracy than the triangular functions employed in our previous work33, thereby enabling finer control and better adaptation to signal variability. Furthermore, the massage stimulation mode, alternating between 80 and 0 Hz, proved effective in reducing fatigue, delivering results comparable to those reported in43, where sequentially distributed NMES protocols were employed for similar objectives.

To statistically assess the performance differences between the EMG-only and hybrid control conditions, paired-sample t-tests were conducted on the following metrics:

-

Task completion time

-

Fatigue index, calculated as the slope of MNP decline over task repetitions

-

User-reported fatigue reduction, derived from subjective Likert-scale responses

The analysis revealed significant improvements in both the fatigue index and perceived fatigue reduction under hybrid control (p < 0.05). Although task completion time was slightly longer in the hybrid mode, the increase was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), suggesting a functional trade-off between execution speed and control stability. Ratings for comfort and usability showed no significant differences between the two modes (p > 0.1), supporting the hybrid system’s general acceptance.

The entire hybrid control pipeline—including EMG acquisition, signal filtering, real-time SVM-based fatigue detection, fuzzy handgrip classification, and NMES triggering, was implemented and executed in real time on the sbRIO-9637 embedded platform. During operation, the system maintained low computational overhead, with average CPU usage below 65% and memory consumption under 50 MB, confirming its suitability for real-time applications without requiring high-performance computing resources.

Experimental trials confirmed that the hybrid system consistently outperformed the standalone bionic hand in all evaluated metrics, including fatigue mitigation, grip force consistency, and control robustness. Classifier latency was negligible, and real-time performance was sustained throughout all sessions. User feedback indicated improved comfort, responsiveness, and naturalistic movement replication, reinforcing the system’s potential for assistive and rehabilitative applications.

Some limitations were also observed. System latency, defined as the end-to-end delay from EMG acquisition to actuator or stimulator response, was measured using timestamp logging in LabVIEW. The average delay was approximately 140–150 ms, which is within acceptable thresholds for real-time rehabilitation control systems23,25, and did not result in perceptible lags during use.

Additionally, the system’s reliance on subject-specific EMG patterns underscores the need for personalized calibration. In this study, calibration was performed manually at the beginning of each session by recording baseline EMG signals during rest and during maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) of both the wrist flexor and extensor muscles. These baseline values were used to normalize input features for classification. While effective, this approach lacks automation. A more formal and automatic calibration protocol, potentially based on adaptive algorithms, would improve both reproducibility and ease of deployment. Addressing this aspect remains an important direction for future work.

Limitations

Although the system supports three stimulation modes, pain relief (80 Hz), relax (alternating 80 Hz/2 Hz), and massage (alternating 80 Hz/0 Hz), this study focused primarily on the massage mode for fatigue reduction trials. This mode was selected due to its cyclic stimulation pattern, which aligned well with the dynamic fatigue levels monitored by the SVM classifier. A formal comparison of the three modes was not conducted but is recognized as an important direction for future work. Each mode involves trade-offs in terms of stimulation intensity, user comfort, and fatigue recovery, and these will be evaluated in subsequent experiments to determine the most effective application scenarios.

Another limitation lies in the system’s reliance on user-specific EMG signal patterns, which necessitates individualized calibration. While basic manual calibration was performed in this study using rest and maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) recordings, the process can be time-consuming and may affect repeatability. Future research will explore automated calibration strategies, including the use of reinforcement learning, to enhance adaptability, reduce setup time, and improve system generalizability across users.

In addition, the current system estimates grip effort indirectly using EMG features such as RMS, which correlate with muscle activity but do not provide absolute force measurements. The lack of integrated physical force sensors limits the system’s ability to monitor actual grip strength or object interaction forces. Future developments will address this by incorporating pressure or tactile sensors (e.g., Force Sensitive Resistors (FSRs), capacitive touch sensors) into the fingertips or palm of the bionic hand. This enhancement would enable real-time feedback, improve grasp stability, and support closed-loop force control, which is essential for safe and functional object manipulation.

Finally, while the system was tested on healthy individuals, extending trials to neurologically impaired users is critical for assessing real-world usability and therapeutic potential. This step will be central to validating the system’s clinical relevance and tailoring it to diverse rehabilitation needs.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of integrating NMES with EMG-controlled bionic hand systems to reduce muscle fatigue and enhance control reliability. The proposed hybrid framework combines a custom 3D-printed bionic hand, real-time signal processing, and machine learning-based classifiers to deliver accurate and responsive control in assistive applications.

Key findings from the experimental evaluation include:

-

Superior performance: The hybrid system (EMG + NMES) yielded significant improvements over the standalone EMG-only approach, including a 28.6% reduction in muscle fatigue, 22% improvement in grip force consistency, and high classification accuracies (95.4% for SVM, 93% for fuzzy logic).

-

Enhanced control stability: Slower decay rates in MNF during extended tasks confirmed the system’s effectiveness in sustaining muscle performance under fatigue conditions.

-

Improved precision and repeatability: Analysis of grip force variability and task trajectory showed that the hybrid system more accurately and consistently replicated user intent.

Collectively, these results validate the proposed system’s potential to enhance functionality, user comfort, and fatigue resilience in EMG-based prosthetic control. Compared to previous studies, this work offers clear advancements in classification robustness, adaptive stimulation, and real-time implementation, highlighting the value of NMES integration in assistive and rehabilitation robotics.

Looking ahead, future research will focus on:

-

Optimizing classifier algorithms for improved personalization and adaptability,

-

Investigating advanced feature extraction methods to boost classification accuracy,

-

Conducting trials with neurologically impaired populations to evaluate real-world applicability and therapeutic effectiveness.

Addressing these areas will enable further refinement of the system and support its application across a broader range of assistive and healthcare scenarios.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Cardoso, L. R., Bochkezanian, V., Forner-Cordero, A., Melendez-Calderon, A. & Bo, A. P. Soft robotics and functional electrical stimulation advances for restoring hand function in people with SCI: a narrative review, clinical guidelines and future directions. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 19, 66 (2022).

Popović, D. B. Advances in functional electrical stimulation (FES). J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 24(6), 795–802 (2014).

Zulauf-Czaja, A. et al. On the way home: a BCI-FES hand therapy self-managed by sub-acute SCI participants and their caregivers: a usability study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 18, 1–8 (2021).

Kapadia, N., Moineau, B. & Popovic, M. R. Functional electrical stimulation therapy for retraining reaching and grasping after spinal cord injury and stroke. Front. Neurosci. 14, 718 (2020).

Barelli, R. G., Avelino, V. F. & Castro, M. C. F. STIMGRASP: A home-based functional electrical stimulator for grasp restoration in daily activities. Sensors 23, 10 (2023).

Suzuki, Y. et al. Evidence that brain-controlled functional electrical stimulation could elicit targeted corticospinal facilitation of hand muscles in healthy young adults. Neuromodulation 26(8), 1612–1621 (2023).

Jovanovic, L. I. et al. Brain–computer interface-triggered functional electrical stimulation therapy for rehabilitation of reaching and grasping after spinal cord injury: a feasibility study. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 7(1), 24 (2021).

Hsu, L. I., Lim, K. W., Lai, Y. H., Chen, C. S. & Chou, L. W. Effects of muscle fatigue and recovery on the neuromuscular network after an intermittent handgrip fatigue task: Spectral analysis of electroencephalography and electromyography signals. Sensors 23(5), 2440 (2023).

Avilés-Mendoza, K., Gaibor-León, N. G., Asanza, V., Lorente-Leyva, L. L. & Peluffo-Ordóñez, D. H. A 3D printed, bionic hand powered by emg signals and controlled by an online neural network. Biomimetics 8(2), 255 (2023).

Tyagi, O. & Mehta, R. K. A methodological framework to capture neuromuscular fatigue mechanisms under stress. Front. Neuroergonom. 2, 779069 (2021).

Li, L., Li, Y. X., Zhang, C. L. & Zhang, D. H. Recovery of pinch force sense after short-term fatigue. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 9429 (2023).

Andrushko, J. W. et al. High force unimanual handgrip contractions increase ipsilateral sensorimotor activation and functional connectivity. Neuroscience 452, 111–125 (2021).

Mugnosso, M., Marini, F., Holmes, M., Morasso, P. & Zenzeri, J. Muscle fatigue assessment during robot-mediated movements. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 15, 1–4 (2018).

Al-Mulla, M. R., Sepulveda, F. & Colley, M. A review of non-invasive techniques to detect and predict localised muscle fatigue. Sensors 11(4), 3545–3594 (2011).

Li, N. et al. Non-invasive techniques for muscle fatigue monitoring: A comprehensive survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 56(9), 1–40 (2024).

Yousif, H. A. et al. Assessment of muscles fatigue based on surface emg signals using machine learning and statistical approaches: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 705(1), 012010 (2019).

Fu, J. et al. Continuous measurement of muscle fatigue using wearable sensors during light manual operations. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). 11581, 266–277 (2019).

Meyer-Rachner, P., Passon, A., Klauer, C. & Schauer, T. Compensating the effects of FES-induced muscle fatigue by rehabilitation robotics during arm weight support. Curr. Direct. Biomed. Eng. 3(1), 31–34 (2017).

Aout, T., Begon, M., Jegou, B., Peyrot, N. & Caderby, T. Effects of Functional Electrical Stimulation on Gait Characteristics in Healthy Individuals: A Systematic Review. Sensors 23(21), 8684 (2023).

Thorsen, R., Dalla Costa, D., Beghi E. & Ferrarin, M. Myoelectrically Controlled FES to Enhance Tenodesis Grip in People With Cervical Spinal Cord Lesion: A Usability Study. Front. Neurosci. 14, 412 (2020).

Vieira, T. M. et al. Timing and modulation of activity in the lower limb muscles during indoor rowing: What are the key muscles to target in FES-rowing protocols?. Sensors (Switzerland) 20(6), 1666 (2020).

Bardi E., Dalla Gasperina, S., Ambrosini A. P. E. Adaptive Cooperative Control for Hybrid FES-Robotic Upper Limb Devices: A Simulation Study. Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS (2021).

Khan, M. A. et al. A systematic review on functional electrical stimulation based rehabilitation systems for upper limb post-stroke recovery. Front. Neurol. 14, 1272992 (2023).

Crepaldi, M. et al. FITFES: A Wearable Myoelectrically Controlled Functional Electrical Stimulator Designed Using a User-Centered Approach. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 29, 2142–2152 (2021).

Ambrosini, E. et al. A Robotic System with EMG-Triggered Functional Eletrical Stimulation for Restoring Arm Functions in Stroke Survivors. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 35, 4 (2021).

Bi, Z. et al. Wearable EMG Bridge - A Multiple-Gesture Reconstruction System Using Electrical Stimulation Controlled by the Volitional Surface Electromyogram of a Healthy Forearm. IEEE Access 8 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. SEMG-Driven Functional Electrical Stimulation Tuning via Muscle Force. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68, 10 (2021).

Abdallah, I. B., Bouteraa, Y. A new design of a bionic hand controlled by EMG signals : A preliminary study. In 20th International Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals & Devices (SSD) (2023).

Peckham, P. H. & Knutson, J. S. Functional electrical stimulation for neuromuscular applications. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 7, 327–360 (2005).

Doucet, B. M., Lam, A. & Griffin, L. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation for Skeletal Muscle Function. Yale J. Biol. Med. 85(2), 201 (2012).

Binder-Macleod, S. A., Halden, E. E. & Jungles, K. A. Effects of stimulation intensity on the physiological responses of human motor units. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 27(4), 556–565 (1995).

Abdallah, I. B. & Bouteraa, Y. An Optimized Stimulation Control System for Upper Limb Exoskeleton Robot-Assisted Rehabilitation Using a Fuzzy Logic-Based Pain Detection Approach. Sensors 24(4), 1047 (2024).

Y. Bouteraa, Y., Ben Abdallah, I. & Elmogy, A. Design and control of an exoskeleton robot with EMG-driven electrical stimulation for upper limb rehabilitation. Ind. Robot 47, 489–501 (2020).

A. T. Ossaba, A. T., Tigreros, J. J. J. & Orjuela, J. C. T. Open Source Multichannel EMG Armband design. 2020 9th International Congress of Mechatronics Engineering and Automation, CIIMA 2020 - Conference Proceedings (2020).

Bouteraa, Y., Abdallah, I. B. & Boukthir, K. A New Wrist-Forearm Rehabilitation Protocol Integrating Human Biomechanics and SVM-Based Machine Learning for Muscle Fatigue Estimation. Bioengineering 10(2), 219 (2023).

Avci, E. A new intelligent diagnosis system for the heart valve diseases by using genetic-SVM classifier. Expert Syst. Appl. 36(7), 10618–10626 (2009).

Fialkoff, B., Hadad, H., Santos, D., Simini, F. & David, M. Hand grip force estimation via EMG imaging. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 74, 103550 (2022).

Lv, J. et al. Prediction of hand grip strength based on surface electromyographic signals. Journal of King Saud University- Computer and Information Sciences. 35(5), 101548 (2023).

Phinyomark, A. et al. A feasibility study on the use of anthropometric variables to make muscle-computer interface more practical. 26, 1681–1688 (2013).

Merletti, R. & Philp, P. Electromyography: Physiology, Engineering, and Non-Invasive Applications | IEEE eBooks | IEEE Xplore (John Wiley & Sons, 2004).

Venugopal, G., Navaneethakrishna, M. & Ramakrishnan, S. Extraction and analysis of multiple time window features associated with muscle fatigue conditions using sEMG signals. Expert Syst. Appl. 41(6), 2652–2659 (2014).

Bouteraa, Y. et al. Design and Development of a Smart IoT-Based Robotic Solution for Wrist Rehabilitation. Micromachines 13, 973 (2022).

Laubacher, M. et al. Stimulation of paralysed quadriceps muscles with sequentially and spatially distributed electrodes during dynamic knee extension. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 16, 1–12 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the King Salman Center for Disability Research through Rresearch group no KSRG-2024-360.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman center For Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2024–360.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and methodolgy Ismail Ben Abdallah. and Yassine Bouteraa.; software, Ismail Ben Abdallah. and Yassine Bouteraa; validation, Ismail Ben Abdallah. and Yassine Bouteraa.; resources, Yassine Bouteraa and Ahmed Alotaibi; writing—original draft preparation, Ismail Ben Abdallah and Yassine Bouteraa.; supervision, Yassine Bouteraa and Ahmed Alotaibi.; project ad-ministration, Yassine Bouteraa, Ahmed Alotaibi.; funding acquisition, Yassine Bouteraa and Ahmed Alotaibi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdallah, I.B., Bouteraa, Y. & Alotaibi, A. Hybrid EMG–NMES control for real-time muscle fatigue reduction in bionic hands. Sci Rep 15, 22467 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05829-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05829-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A hybrid EMG–EEG interface for robust intention detection and fatigue-adaptive control of an elbow rehabilitation robot

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A Novel Gender Identification Approach Based on 4-Channel EMG Signals Measured During Different Hand Movements

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)