Abstract

Chronic osteomyelitis (COM) is a persistent bone infection associated with severe complications, making early and accurate diagnosis essential. Traditional diagnostic methods, including imaging and bacterial cultures, are often limited by low sensitivity, long processing times, and the inability to detect infections in certain clinical scenarios. In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic utility of inflammatory biomarkers for COM, including neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6). A total of 200 participants, including 100 COM patients and 100 healthy controls, were enrolled. Our results showed that Gram-positive bacteria were more prevalent (59%), with Staphylococcus aureus being the most frequently isolated pathogen. Antibiotic resistance profiling revealed that Gram-positive bacteria exhibited high resistance to Penicillins but remained sensitive to Vancomycin and Linezolid. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria showed high resistance to certain Penicillins, while sensitive to Carbapenems. Inflammatory marker levels (NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6) were significantly elevated in COM patients, with higher levels in Gram-negative infections. Multivariate logistic regression analysis and ROC curve analysis demonstrated that these inflammatory markers were significant predictors of COM, and the combination of these biomarkers showed superior diagnostic performance. Our findings suggest that NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 are valuable diagnostic biomarkers for COM, and their combination enhances diagnostic precision, offering a promising tool for clinical management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic osteomyelitis (COM) is a persistent infection of the bone and surrounding soft tissues, commonly arising as a complication of open fractures, hematogenous infections, or inadequately treated acute osteomyelitis1,2,3,4. COM can result in severe complications, including extensive bone destruction, osteonecrosis, and suppurative arthritis, which may result in amputation and long-term disability5. These outcomes can exert significant impact on a patient’s quality-of-life and increase the economic burden on their families. Recent studies reported that open fractures and implant-associated osteomyelitis account for 80% of all cases of osteomyelitis, with 10–30% progressing to chronic stages. Over the past four decades, the incidence of COM has almost doubled, reaching 21.8 per 100,000 individuals, with approximately 23% of patients requiring multiple debridement procedures and 6% ultimately needing amputation due to uncontrolled infections6,7. Due to its complex etiology, prolonged treatment course, high recurrence rates, and the potential for limb disability8it is critical that COM is diagnosed early and accurately to initiate timely interventions, improve patient prognosis, and prevent disease progression.

The current diagnostic approach for COM integrates clinical examination, imaging studies (e.g., X-rays, Computed Tomography (CT) scans), and bacterial cultures8,9,10. However, these tools are associated with a number of limitations. For example, the early-stage symptoms of COM are often non-specific, resembling other musculoskeletal disorders and contributing to diagnostic delays or errors. Furthermore, imaging techniques may fail to detect abnormalities in the early stages of infection, and significant structural changes are usually only observed in cases of advanced disease. Bacterial cultures, while considered the gold standard for identifying pathogens are frequently hindered by a range of factors, including previous antibiotic use, polymicrobial infections, or the presence of non-viable organisms1,11. Moreover, the lengthy processing time for cultures often delays treatment decisions, thus exacerbating patient outcomes.

These challenges highlight the urgent need for complementary diagnostic approaches. Recent advances in immunology have revealed that pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs), particularly TLR2 and TLR411. This activation triggers downstream signaling pathways such as NF-κB and MAPK, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-612–15. These cytokines, in turn, could serve as reliable biomarkers for diagnosing in COM. Moreover, serum inflammatory biomarkers, such as the NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6, have emerged as promising tools for the early detection and monitoring of infections16,17,18,19,20. Despite their widespread clinical use in diagnosing various conditions, their diagnostic utility in COM, particularly in distinguishing infections caused by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, remains underexplored.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the diagnostic value of NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 in COM patients, with a focus on their potential to enhance diagnostic precision and guide personalized treatment strategies. Specifically, we sought to address the gap in current understanding relating to how these biomarkers may be able to distinguish pathogen-specific infection profiles. By systematically analyzing these markers in COM patients and comparing them to healthy controls, we provide novel insights into their clinical applicability for early and accurate diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Patients and controls

The study included 100 patients diagnosed with COM treated at Lianyungang Municipal Oriental Hospital between January 2014 and June 2023. The cohort consisted of 58 males and 42 females. An additional 100 healthy individuals, undergoing routine physical examinations during the same period, were recruited as the control group. The sample size for this study was determined using the Power and Sample Size online tool (https://powerandsamplesize.com/), with the following parameters: a significance level (α) of 0.05, power (1 - β) set at 0.80 to ensure 80% probability of correctly rejecting the null hypothesis, and a 1:1 ratio for sample sizes between the two groups. The required sample size for each biomarker— NLR, CRP, TNF-α and IL-6 —was calculated based on mean values and standard deviations derived from literature and our preliminary data21. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Lianyungang Municipal Oriental Hospital (Approval Number: 2022-030−01), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria required that patients had been diagnosed with COM, which was confirmed by X-ray or CT scans, in accordance with the criteria described in Practical Orthopedics22. Additionally, patients had to provide informed consent and have a positive bacterial culture from the lesion site identifying a single dominant strain of bacteria. Patients were excluded if they met the diagnostic criteria for COM but had negative bacterial cultures, had polymicrobial infections, were pregnant or lactating, or had a history of malignant tumors or serious infectious diseases. Additionally, patients with a history of antibiotic use within two weeks prior to admission were excluded from the study.

Microbiological and antibiotic sensitivity testing

Upon admission, all COM patients underwent bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity testing. Exudates were collected from the lesion site using aseptic techniques. The procedure involved irrigating the sinus tract or puncture site with sterile physiological saline to collect the sample, which was then transported to the laboratory within two hours to ensure the integrity of the specimen. Bacterial cultures were incubated in a Thermo-240i carbon dioxide incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) under optimal conditions for 24–48 h. After incubation, bacterial colonies were analyzed using the MicroScan AutoSCAN-4 (Beckman Coulter) automated microbiological identification system, which identifies bacterial species based on their biochemical profiles. Antibiotic sensitivity testing was performed immediately following bacterial identification using the MicroScan AutoSCAN-4 system. The system tested various antibiotics against the isolated bacteria, providing precise information on the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for each antibiotic. The results of the antibiotic sensitivity test were typically available within 48–72 h and used to guide the selection of the most appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

Biomarker detection

All blood samples collected from COM patients were immediately processed after collection. The serum was separated by allowing the sample to stand at room temperature for at least 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 10 min, and then stored at −80 °C for further analysis. The samples were thawed only once before measurement to ensure the integrity of the biomarkers. For the healthy control group, blood collection, processing, and storage procedures were identical to those for the COM group to minimize diurnal variations in biomarker levels.

Upon admission, 4 ml of peripheral venous blood was drawn from COM patients on an empty stomach the following morning for the measurement of TNF-α and IL-6 levels using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISA kits were supplied by Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co. Samples were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and absorbance values were measured to determine the concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6. In addition, NLR and CRP levels were measured using the BC-5390 automated hematology analyzer (Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics Co.).

Quality control

Microbiological testing and antibiotic sensitivity assays adhered to standardized protocols, with both positive and negative bacterial controls included in each batch. Regular calibration and maintenance of the MicroScan AutoSCAN-4 ensured optimal performance. For TNF-α and IL-6 detection, ELISA assays included controls, with the coefficient of variation (CV) maintained under 10% for precision. Detection limits followed manufacturer guidelines, and assays were performed in duplicate to reduce errors. NLR and CRP detection involved both internal and external quality controls. The BC-5390 analyzer underwent regular calibration, and quality control samples were tested alongside patient samples to ensure result accuracy, with automated checks ensuring consistent performance.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 19.0). Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR), depending on the distribution. Normality was tested with the Shapiro-Wilk test. For normally distributed data, comparisons between the COM and control groups were performed using independent t-tests. For non-normally distributed data, comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as percentages and were compared using the chi-squared test.

A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed to determine the diagnostic value of biomarkers (NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6), adjusting for potential confounders such as age and sex. The diagnostic performance of individual biomarkers and their combinations was evaluated using ROC curve analysis. For the combined biomarkers, a composite score was derived by combining the selected biomarkers based on their weighted coefficients from the logistic regression model. The relative diagnostic performance of different biomarker combinations was compared by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) and assessing sensitivity and specificity. A statistical comparison of ROC curves was performed using the DeLong test to assess the significance of differences in the AUC between individual biomarkers and combinations23. Missing data were handled using listwise deletion (complete case analysis), as the proportion of missing data was minimal and occurred randomly, ensuring the integrity and reliability of the results. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study cohorts

To investigate the pathogenic bacteria and antibacterial drug profiles associated with COM and assess the diagnostic value of key inflammatory markers, we enrolled 200 participants, including 100 COM patients and 100 healthy controls (Fig. 1). A range of clinical data, including sex, age, and lesion location, were acquired to ensure comparability between groups (Table 1). The two groups were well-matched, with no significant differences in sex distribution (male: 54% vs. 58%, p = 0.569) or mean age (42.1 ± 11.0 years vs. 43.4 ± 10.8 years, p = 0.415). Lesion distribution in COM patients varied, with the tibia (36%) and femur (28%) being the most frequently affected bones. These characteristics ensured the reliability of subsequent comparative analyses.

Study design and biomarker detection overview. (a) Diagram illustrating the two cohorts: 100 chronic osteomyelitis (COM) patients and 100 controls. (b) Illustration of the common pathogenic bacteria and antibacterial drugs used in the study. (c) Distribution of inflammatory marker levels, including neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), between the control group and the COM group (left) and between Gram-positive and Gram-negative infection groups (right). (d) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve showing the diagnostic value of inflammatory markers (NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6) for COM.

Pathogen detection and distribution in COM patients

Given the infectious nature of COM, we investigated the distribution of pathogens to identify the predominant causative organisms (Table 2). Analysis confirmed that Gram-positive bacteria were more prevalent (59% of cases), with Staphylococcus aureus being the most frequently isolated pathogen (43%), followed by Streptococcus viridans (4%) and Streptococcus pyogenes (3%). However, Gram-negative bacteria also played a significant role (41%); Pseudomonas aeruginosa (13%) and Escherichia coli (12%) being the most common forms. In terms of demographic distribution, there were no significant differences between male and female patients regarding the isolation of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, pathogen distribution did not show significant variation across different lesion locations, including tibia, femur, and other locations.

Antibiotic resistance profile of major pathogenic bacteria

To guide effective antibiotic therapy, we conducted resistance profiling of major pathogenic bacteria. For Gram-positive bacteria (Table 3), including Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Staphylococcus epidermidis, high resistance rates (97.7–100%) were observed against Penicillins such as Penicillin and Ampicillin, with resistance also notable against Erythromycin. However, these strains were sensitive to Glycopeptides (Vancomycin) and Oxazolidinones (Linezolid). In contrast, for Gram-negative bacteria (Table 4), resistance varied significantly among different species. Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibited high resistance to Penicillins such as Ampicillin and Piperacillin, with resistance rates up to 92.3%. Interestingly, these Gram-negative strains remained sensitive to Carbapenems (Meropenem and Imipenem), with low resistance rates, highlighting their potential utility as therapeutic options.

Inflammatory marker levels in COM and pathogen-specific differences

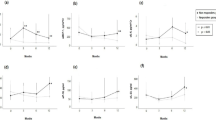

Since COM is associated with a pronounced inflammatory response, we measured the levels of key inflammatory markers (NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6) in both COM patients and healthy controls to evaluate their diagnostic relevance. Analysis revealed that all four markers were significantly elevated in COM patients when compared to controls, as shown in Fig. 2a. Further analysis revealed pathogen-specific differences in inflammatory marker levels, as shown in Fig. 2b. Infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria were associated with significantly higher levels of NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 compared to Gram-positive infections (P < 0.05). These data suggest that Gram-negative pathogens may trigger a more robust inflammatory response, which could have implications for the severity of disease and patient management. Additionally, subgroup analysis based on lesion location revealed no significant changes in the levels of these inflammatory markers between the different lesion sites (Table S1), indicating that the inflammatory response in COM is not significantly affected by lesion location.

Inflammatory marker levels in COM and pathogen-specific groups. (a) Comparison of NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels between COM patients and healthy controls. All markers were significantly elevated in the COM group. (b) Inflammatory marker levels stratified by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial infections. Gram-negative infections were associated with higher levels of all markers, indicating a stronger inflammatory response. Data in a and b are presented as the mean ± SD for normally distributed data and as the Median (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Diagnostic value of inflammatory markers for COM

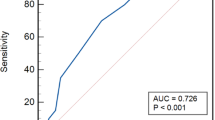

To further evaluate the diagnostic relevance of inflammatory biomarkers in COM, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed, adjusting for gender and age. The results showed that NLR (OR = 1.86), CRP (OR = 1.34), TNF-α (OR = 1.17), and IL-6 (OR = 1.32) were all significant predictors of COM, as demonstrated in Table 5, indicating strong associations (P < 0.001). Additionally, ROC curve analysis was used to assess the sensitivity and specificity of these markers both individually and in combination (Table 6; Fig. 3). Among the individual markers, CRP exhibited the highest diagnostic accuracy with an AUC of 0.930, followed closely by IL-6 (AUC = 0.923) and TNF-α (AUC = 0.887). NLR demonstrated a moderate diagnostic value with an AUC of 0.857. Remarkably, the combination of these biomarkers achieved an AUC of 0.988, which was significantly higher than that of any individual marker (P < 0.001), indicating that a multi-marker approach offers superior diagnostic performance compared to single biomarkers.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels were significantly elevated in COM patients, thus highlighting their potential as diagnostic biomarkers. The combination of multiple markers further improved diagnostic performance, emphasizing the value of a multi-marker approach. Additionally, Gram-negative infections were associated with higher levels of NLR, TNF-α, and CRP than Gram-positive infections. This reflects distinct inflammatory responses and highlights the need for tailored diagnostics. Our findings confirm the predominance of Staphylococcus aureus in COM infections and provide valuable insights into optimizing early diagnosis and personalized treatment strategies for COM.

Our analysis showed that the tibia and femur were the most frequently affected bones in COM, with lower-limb involvement accounting for over 50% of cases. This finding aligns with previous results of Yeh et al. who reported that COM predominantly affects the lower limbs due to their higher exposure to trauma and compromised vascular supply24. These anatomical and physiological vulnerabilities may contribute to the development of chronic infections in these regions. In this study, pathogen detection indicated that Gram-positive bacteria were the leading causative agents, accounting for 59% of cases. Staphylococcus aureus identified as the most prevalent pathogen (43%). These findings align closely with previous reports25,26which consistently identified Staphylococcus aureus as the predominant pathogen in osteomyelitis. The presence of other Gram-positive bacteria, such as Streptococcus viridans and Streptococcus pyogenes, emphasized the diversity of the pathogens contributing to bone infections. Furthermore, Gram-negative bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli, were frequently identified. This highlights the need for broad-spectrum coverage during empirical treatment.

The antibiotic resistance profile of major pathogenic bacteria in our study highlights a significant clinical challenge in the management of COM. For Gram-positive bacteria, high resistance rates were observed against Penicillins, such as Penicillin and Ampicillin, along with notable resistance to Erythromycin. However, these strains exhibited sensitivity to Vancomycin and Linezolid. This confirms their efficacy as therapeutic options for treating infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. This finding aligns with regional resistance patterns, where Gram-positive pathogens are increasingly resistant to commonly used antibiotics27. In contrast, for Gram-negative bacteria, resistance varied significantly across species. Escherichia coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae showed high resistance to Penicillins such as Ampicillin and Piperacillin, with resistance rates reaching up to 92.3%. Interestingly, these Gram-negative strains remained sensitive to Carbapenems (Meropenem and Imipenem), with low resistance rates. This highlights the potential utility of Carbapenems as a therapeutic option. The observed differences in resistance profiles between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria underscore the importance of understanding pathogen-specific resistance patterns when selecting antibiotics for treatment. This finding is consistent with global concerns about the rise of multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens, commonly known as superbugs, which pose an increasing threat to public health28.

Inflammatory markers play crucial roles in the immune response, highlighting these as valuable tools for the clinical diagnosis of infectious diseases29,30. Research has shown that PAMPs activate TLRs on immune cells, playing a key role in pathogen recognition. Specifically, TLR2 recognizes lipoteichoic acid from Gram-positive bacteria, while TLR4 is activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria12. This activation triggers a series of downstream signaling pathways, leading to the excessive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines13. The abnormal activation of immune cells and the excessive release of inflammatory mediators are key features in the pathogenesis of COM31. For example, infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus can stimulate macrophages via endotoxins, triggering the release of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. These cytokines activate vascular endothelial cells, promoting the expression of adhesion molecules and contributing to bone tissue destruction32. Given the pathophysiology of COM, the selection of appropriate inflammatory markers for early diagnosis is essential for guiding timely interventions.

Among commonly used clinical biomarkers, NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 are particularly valuable for evaluating inflammatory responses. NLR, which reflects changes in the distribution of leukocytes, has gained significant clinical attention due to its ease of measurement, low cost, and high sensitivity. Elevated levels of NLR have been linked to poor outcomes in various inflammatory diseases, including acute pancreatitis and ulcerative colitis, and are known to be predictive of disease severity33,34. Similarly, CRP, an acute-phase protein synthesized in the liver, is known to increase significantly during bacterial infections but remains relatively low in viral infections. This makes CRP a sensitive and specific indicator of bacterial infections17,35. CRP is also commonly utilized to monitor the severity and recurrence of infectious diseases, including COM. TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, is crucial in COM progression. Its levels correlate with disease severity36,37. Likewise, IL-6 activates immune cells and endothelial function, contributing to tissue damage32. Both TNF-α and IL-6 increase in bacterial infections, highlighting their diagnostic value in COM38.

In this study, we found that the levels of NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 were significantly elevated in COM patients compared to healthy controls, demonstrating their diagnostic potential. Multivariate logistic regression and ROC curve analysis confirmed the value of these biomarkers. CRP showed the highest individual diagnostic accuracy. A previous meta-analysis, utilizing Forrest plots and ROC curves, aligned with previous findings. The meta-analysis also highlighted that CRP exhibited high sensitivity and specificity for diabetic foot osteomyelitis, with pooled values of 0.72 and 0.76, respectively, and a pooled AUC of 0.7739. This variation in AUC may reflect differences in inclusion criteria and control groups. Moreover, the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 are elevated not only in COM but also in other chronic inflammatory conditions like psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In RA, TNF-α has a diagnostic value of 0.99, while IL-6 is 0.67 (compared to PsA)40. These biomarkers also show high expression and diagnostic value in other conditions, suggesting their broad applicability. Future studies should evaluate their specificity in both COM and other inflammatory conditions. This would help establish more robust and condition-specific cut-off values for optimal diagnostic accuracy. The combination of NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6, achieving an AUC of 0.988, underscores the complementary roles of cellular immunity (NLR), acute-phase proteins (CRP), and cytokine networks (TNF-α and IL-6) in capturing the multidimensional inflammatory landscape of COM. Furthermore, the elevated levels of these biomarkers in patients with Gram-negative infections, compared to Gram-positive infections, align with previous studies41. This elevation corresponds with the hyperactivation of innate immune pathways, particularly TLR4-mediated signaling. For example, Gram-negative pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli primarily activate TLR4 via LPS recognition. This leads to robust NF-κB activation and the subsequent release of IL-6 and TNF-α. This mechanistic pathway is further supported by studies on COVID-1915, where TLR4 hyperactivation contributes to cytokine storms, a phenomenon that mirrors the systemic inflammation observed in our Gram-negative COM cohort.

The clinical utility of these biomarkers lies in their ability to provide accessible, rapid, and cost-effective diagnostic information. We estimate that the combined cost for testing the four biomarkers is approximately $20. The dynamics of these biomarkers during antibiotic therapy further support their clinical utility. Studies have shown that in diabetic foot osteomyelitis, CRP and IL-6 levels significantly declined after three weeks of vancomycin/piperacillin-tazobactam therapy42. Another study indicated that after initiating antibiotic treatment, WBC, CRP, and PCT levels returned to near-normal levels by day 7, although ESR remained elevated in COM until 3 months post-treatment43. This suggests that the kinetics of NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 may be more effective for predicting early treatment response. In scenarios involving delayed or negative bacterial cultures, these biomarkers could provide critical diagnostic support, enabling timely and appropriate intervention. Incorporating NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 into routine diagnostic protocols for COM holds significant promise for improving diagnostic accuracy, guiding personalized treatment strategies, and ultimately enhancing patient outcomes.

Limitations

This study offers valuable insights into the diagnostic utility of NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 for COM, but several limitations should be acknowledged. First, comorbidities, such as diabetes and autoimmune disorders, may affect biomarker levels. Research has shown that inflammation markers, such as CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 are significantly elevated in conditions such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus44. Future studies should address this by conducting more detailed subgroup analyses based on patients’ medical histories, providing a deeper understanding of the factors influencing biomarker levels. Second, the lack of disease control groups is a significant limitation. Biomarker levels in other bone and joint inflammatory conditions, such as RA and osteoarthritis (OA), have shown marked elevations in CRP and TNF-α45,46. However, studies have reported that IL-6 levels do not significantly change in conditions like chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis47. Comparing these biomarkers across different inflammatory diseases will be crucial for validating their specificity and diagnostic potential and improving the clinical applicability of our findings. In future studies, we plan to include patients with RA and OA to assess the specificity of these biomarkers. Third, the absence of stratification by infection etiology, clinical type, infection stage, and disease severity limits our understanding of how biomarkers perform across different infection profiles. Stratified analyses by these factors in future research will refine the diagnostic use of these biomarkers. Fourth, the retrospective nature of the study introduces biases, including selection bias and the inability to control for unmeasured confounders, which could affect generalizability. We acknowledge these limitations and recommend that future prospective studies help address these issues. Fifth, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the relatively homogenous patient population studied. Future studies should validate these results in diverse patient groups and across different geographic locations to assess the broader applicability of our findings. Sixth, this study did not compare the biomarkers we evaluated with other commonly used biomarkers, such as WBC count or ESR, which are typically part of the diagnostic workup for infections. This comparison will be crucial to assess their relative diagnostic value. Lastly, we observed two cases of S. epidermidis infection, which may indicate superficial contamination despite aseptic procedures, emphasizing the need for stringent sampling methods. Expanding the sample size and exploring other biomarkers, such as procalcitonin and interleukin-1, may improve diagnostic accuracy. Longitudinal studies to assess biomarker levels throughout treatment will also enhance our ability to monitor disease progression and predict treatment outcomes.

Conclusions

Our analysis demonstrated that NLR, CRP, TNF-α, and IL-6 are valuable diagnostic markers for COM. The combination of these markers enhances diagnostic precision, thus providing practical tools for early detection, especially when bacterial cultures are delayed or inconclusive. The distinct biomarker profiles observed between Gram-positive and Gram-negative infections underscore the potential for etiology-driven therapeutic strategies, aligning with pathogen-specific antibiotic resistance patterns. Importantly, the preserved sensitivity of key antibiotics against predominant pathogens supports the integration of biomarker-guided early intervention to optimize empirical therapy and mitigate antimicrobial resistance. Incorporating these accessible biomarkers into routine clinical practice could facilitate timely intervention and personalized treatment. Future research with larger cohorts and additional biomarkers will further refine diagnostic strategies and improve patient outcomes in COM.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Lew, D. P., Waldvogel, F. A. & Osteomyelitis Lancet 364, 369–379, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5 (2004).

Dym, H. & Zeidan, J. Microbiology of acute and chronic osteomyelitis and antibiotic treatment. Dent. Clin. North. Am. 61, 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2016.12.001 (2017).

Besal, R., Adamic, P., Beovic, B. & Papst, L. Systemic antimicrobial treatment of chronic osteomyelitis in adults: A narrative review. Antibiot. (Basel). 12, 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12060944 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Flourishing antibacterial strategies for osteomyelitis therapy. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 10, e2206154. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202206154 (2023).

Cox, A. J., Zhao, Y. & Ferguson, P. J. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and related Diseases-Update on pathogenesis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 19, 18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-017-0645-9 (2017).

Schmidt, B. M. et al. Comorbid status in patients with osteomyelitis is associated with long-term incidence of extremity amputation. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care. 11, e003611. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2023-003611 (2023).

Camilleri-Brennan, J. et al. A scoping review of the outcome reporting following surgery for chronic osteomyelitis of the lower limb. Bone Jt. Open. 4, 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1302/2633-1462.43.BJO-2022-0109.R1 (2023).

Hatzenbuehler, J. & Pulling, T. J. Diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis. Am. Fam Physician. 84, 1027–1033 (2011).

Maffulli, N. et al. The management of osteomyelitis in the adult. Surgeon 14, 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2015.12.005 (2016).

Peel, T. N., Cherk, M. & Yap, K. Imaging in osteoarticular infection in adults. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 30, 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2023.11.001 (2024).

Mader, J. T., Ortiz, M. & Calhoun, J. H. Update on the diagnosis and management of osteomyelitis. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 13, 701–724 (1996).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Toll-like receptor-guided therapeutic intervention of human cancers: molecular and immunological perspectives. Front. Immunol. 14, 1244345. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1244345 (2023).

Behzadi, P., Kim, C. H., Pawlak, E. A., Algammal, A. & Editorial The innate and adaptive immune system in human urinary system. Front. Immunol. 14, 1294869. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1294869 (2023).

Behzadi, P. et al. The Interleukin-1 (IL-1) superfamily cytokines and their single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). J. Immunol. Res. 2022 (2054431). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2054431 (2022).

Behzadi, P. et al. The dual role of toll-like receptors in COVID-19: balancing protective immunity and Immunopathogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 284, 137836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.137836 (2025).

Zahorec, R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratisl Lek Listy. 122, 474–488. https://doi.org/10.4149/BLL_2021_078 (2021).

Sproston, N. R. & Ashworth, J. J. Role of C-reactive protein at sites of inflammation and infection. Front. Immunol. 9, 754. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00754 (2018).

Zelova, H. & Hosek, J. TNF-alpha signalling and inflammation: interactions between old acquaintances. Inflamm. Res. 62, 641–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-013-0633-0 (2013).

Tanaka, T., Narazaki, M. & Kishimoto, T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 6, a016295. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a016295 (2014).

Surendar, J. et al. Osteomyelitis is associated with increased anti-inflammatory response and immune exhaustion. Front. Immunol. 15, 1396592. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1396592 (2024).

Ranganathan, P., Deo, V. & Pramesh, C. S. Sample size calculation in clinical research. Perspect. Clin. Res. 15, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.4103/picr.picr_100_24 (2024).

Erdman, W. A. et al. Osteomyelitis: characteristics and pitfalls of diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiology 180, 533–539. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.180.2.2068324 (1991).

Cai, H., Pang, Y., Fu, X., Ren, Z. & Jia, L. Plasma biomarkers predict alzheimer’s disease before clinical onset in Chinese cohorts. Nat. Commun. 14, 6747. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42596-6 (2023).

Yeh, T. C. et al. Characteristics of primary osteomyelitis among children in a medical center in taipei, 1984–2002. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 104, 29–33 (2005).

Gimza, B. D. & Cassat, J. E. Mechanisms of antibiotic failure during Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. Front. Immunol. 12, 638085. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.638085 (2021).

Yang, L. et al. Pathogen identification in 84 patients with post-traumatic osteomyelitis after limb fractures. Ann. Palliat. Med. 9, 451–458. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm.2020.03.29 (2020).

Algammal, A. M., Behzadi, P. & Antimicrobial Resistance A global public health concern that needs perspective combating strategies and new talented antibiotics. Discov Med. 36, 1911–1913. https://doi.org/10.24976/Discov.Med.202436188.177 (2024).

Algammal, A., Hetta, H. F., Mabrok, M., Behzadi, P. & Editorial Emerging multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens superbugs: A rising public health threat. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1135614. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1135614 (2023).

Groeneveld, N. S. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid inflammatory markers to differentiate between neonatal bacterial meningitis and sepsis: A prospective study of diagnostic accuracy. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 142, 106970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2024.02.013 (2024).

Han, Q. et al. Clinical value of monitoring cytokine levels for assessing the severity of mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. Am. J. Transl Res. 16, 3964–3977. https://doi.org/10.62347/OUPW3987 (2024).

Hofmann, S. R. et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO): presentation, pathogenesis, and treatment. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 15, 542–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-017-0405-9 (2017).

Huang, R. L. et al. LPS-stimulated inflammatory environment inhibits BMP-2-induced osteoblastic differentiation through crosstalk between TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappaB and bmp/smad signaling. Stem. Cells. Dev. 23, 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2013.0345 (2014).

Kong, W., He, Y., Bao, H., Zhang, W. & Wang, X. Diagnostic Value of Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio for Predicting the Severity of Acute Pancreatitis: A Meta-Analysis. Dis Markers 9731854, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9731854 (2020).

Huang, Z., Fu, Z., Huang, W. & Huang, K. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in sepsis: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 38, 641–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.10.023 (2020).

Rizo-Tellez, S. A., Sekheri, M. & Filep, J. G. C-reactive protein: a target for therapy to reduce inflammation. Front. Immunol. 14, 1237729. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1237729 (2023).

Deutschmann, A., Mache, C. J., Bodo, K., Zebedin, D. & Ring, E. Successful treatment of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis with tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockage. Pediatrics 116, 1231–1233. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2206 (2005).

Costa-Reis, P. & Sullivan, K. E. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. J. Clin. Immunol. 33, 1043–1056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-013-9902-5 (2013).

Jiang, N., Qin, C. H., Hou, Y. L., Yao, Z. L. & Yu, B. Serum TNF-alpha, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and IL-6 are more valuable biomarkers for assisted diagnosis of extremity chronic osteomyelitis. Biomark. Med. 11, 597–605. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2017-0082 (2017).

Ansert, E. A. et al. Update of biomarkers to diagnose diabetic foot osteomyelitis: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Wound Repair. Regen. 32, 366–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/wrr.13174 (2024).

Cheleschi, S., Tenti, S., Bedogni, G. & Fioravanti, A. Circulating Mir-140 and leptin improve the accuracy of the differential diagnosis between psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study. Transl Res. 239, 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2021.08.001 (2022).

Abe, R. et al. Gram-negative bacteremia induces greater magnitude of inflammatory response than Gram-positive bacteremia. Crit. Care. 14, R27. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc8898 (2010).

Van Asten, S. A. et al. The value of inflammatory markers to diagnose and monitor diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Int. Wound J. 14, 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12545 (2017).

Michail, M. et al. The performance of serum inflammatory markers for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with osteomyelitis. Int. J. Low Extrem Wounds. 12, 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534734613486152 (2013).

Lontchi-Yimagou, E., Sobngwi, E., Matsha, T. E. & Kengne, A. P. Diabetes mellitus and inflammation. Curr. Diab Rep. 13, 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-013-0375-y (2013).

Scherer, H. U., Haupl, T. & Burmester, G. R. The etiology of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 110, 102400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2019.102400 (2020).

Abramson, S. B. & Yazici, Y. Biologics in development for rheumatoid arthritis: relevance to osteoarthritis. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 58, 212–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.008 (2006).

Hofmann, S. R. et al. Serum Interleukin-6 and CCL11/Eotaxin May be suitable biomarkers for the diagnosis of chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Front. Pediatr. 5, 256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2017.00256 (2017).

Funding

This research was supported by the Jiangsu Province 333 High-level Talent Training Project (Grant number: 201412); the Lianyungang Science and Technology Project (Social Development, Grant number: SH1545); and the Research and Development Fund of Kangda College of Nanjing Medical University (Grant number: KD2024KYJJ112).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wanwen Feng, Wenhui Zhao, and Yanbin Dong designed the research. Wenhui Zhao and Dongxiang Xu drafted the manuscript, conducted clinical sample collection, and performed data analysis, as well as generated the figures. Wanwen Feng and Yanbin Dong were responsible for the revision of the manuscript. All authors thoroughly reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Lianyungang Municipal Oriental Hospital (Approval number: 2022-030-01) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual patients included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, W., Xu, D., Dong, Y. et al. Diagnostic value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and serum biomarkers in chronic osteomyelitis. Sci Rep 15, 21752 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05856-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05856-7