Abstract

It is essential to adopt effective therapy strategies for periodontal diseases to achieve optimal results while avoiding adverse effects on the system. This study has developed various PEGylated chitosan-based biodegradable xerogels for localized release of doxycycline hyclate (DH) to treat periodontal infectious diseases. The xerogels were formulated using the solvent casting method, and the solvent (0.25 M HCl) was slowly evaporated at ambient conditions. Two different molecular weights were employed for chitosan and polyethylene glycol, and twelve combinations, including the placebos and controls, were prepared for the formulation of xerogels. Different physical and chemical characteristics of the prepared DH xerogels were studied, such as drying time and rate, thickness, moisture content, swelling index, organoleptic characteristics, scanning electron microscopy, FTIR spectrometry, differential scanning calorimetry, drug release and kinetics, and antibacterial activity. The results revealed that the drug transforms from a crystalline to an amorphous state, thus rapidly releasing the drug (> 60% in 30 min. in all xerogels), followed by a sustained release up to 10 h. The release kinetics results revealed that the drug followed the Korsmeyer–Peppas model. It is concluded that the formulated DH-loaded xerogels showed promising results for use in the periodontal pockets to treat various infectious diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Xerogels have garnered significant attention recently as novel drug delivery systems. They are extensively studied for their potential in numerous drug delivery systems1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, including a few reported applications in the oral cavity17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25.

The selection of biomedical materials, particularly for applications in periodontal pathologies, is paramount due to their intrinsic characteristics. Not only the type of polymers and drugs but also the nature of the solvent affect the physicochemical characteristics of the dosage form. During the sol–gel process, the solvent facilitates the hydrolysis and condensation reactions necessary to form the gel network26,27. It also affects the porosity, surface area, and mechanical strength of the resulting xerogel28,29,30. The solvent volatility and interactions with the gel components are crucial for efficient solvent removal, ultimately determining the xerogel structure and drug release profiles29,30. Previously, our group has studied the sustained release effect of doxycycline hyclate (DH) from PEGylated acetic acid-based chitosan xerogels, and the rationale for selecting those polymers has already been discussed31. However, the choice of solvent plays a critical role in preparing xerogels, significantly influencing their structural and functional characteristics32,33. Despite these promising results, there remains a need to explore alternative solvents that might offer improved control over xerogels’ physicochemical characteristics and drug release behavior.

Currently, no xerogel dosage form of DH is available in the market. Internationally, two different novel commercial products, PerioChip® (i.e., a polymeric chip of chlorhexidine gluconate) and Atridox® (a 10% solution of doxycycline and polymers, both given separately in prefilled syringes), are available for the treatment of periodontal diseases. Due to their high costs, they are unaffordable to most patients; thus, dental practitioners rarely use these products. In contrast, the xerogels developed in this study present a cost-effective alternative. The present study aims to create a relatively economical xerogel system using hydrochloric acid for local drug delivery of DH. This study would help develop an understanding of the solvent effect on the physicochemical properties and drug release behaviors of PEGylated chitosan xerogels.

Materials and methods

Materials

Doxycycline hyclate (DH, ≥ 98%), polyethylene glycol (PEG, Mw: 8000 and 20,000), and chitosan (CHT, ≥ 95% acylated; medium: 100–200 mPa.s and high: 200–400 mPa.s) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All the other chemicals and solvents used were of analytical grade. Freshly prepared double reverse osmosis deionized water with zero total dissolved solids (TDS) was used throughout the study (FineTech Water Treatment, Pakistan).

Preparation of placebo xerogels

All the solutions of each ingredient were prepared in 0.25 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) in the desired concentrations (Table 1) with continuous magnetic stirring (ACE–HS–5L, ACE GmbH, Germany). A 3% solution of each medium (MMW) and high molecular weight (HMW) CHT was prepared using 0.25 M HCl and stirred for 90 min at 60 ± 5 °C. Various combinations of polymers were prepared with respect to their molecular weights to obtain the final concentration at the desired level (Table 1). Each type of PEG solution (i.e., MMW and HMW) was mixed with each CHT solution (i.e., MMW and HMW) and magnetically stirred for 90 min. at 60 ± 5 °C. Once a homogenous solution was formed and the temperature of the mixture was dropped to 30 ± 5 °C, the polymer mixture was poured (10 ml) into the plastic Petri dishes (55 mm diameter) and left to dry without lids in ambient conditions (i.e., 25 ± 2 °C) for up to 120 h to develop the placebo xerogels (X1–X6). Of these placebos, xerogels X1, X2, and X7, X8 served as controls containing each CHT type only without or with DH, while X3–X6 were prepared as placebos. Each sample was prepared in at least triplicate. The illustrative image of the formulation procedure is presented in Fig. 1.

Preparation of drug-loaded xerogels

As described above, polymers (CHT and PEG) were mixed at 60 ± 5 °C. Once the solution temperature dropped to 30 ± 5 °C, the drug solution was added (Table 1), and the mixture was further stirred for 30 min. with occasional overhead stirring (MS 5060D, MTOPS, Misung Scientific, Korea) since it became viscous at room temperature. After forming a homogenous gel matrix, the drug-polymer gels were dried as described above. A DH control with each CHT type only was also prepared similarly. Each sample was prepared in at least triplicate.

Storage of the xerogels

All xerogel samples prepared in the Petri dishes were covered with the lids and stored in the sealed desiccator at room temperature (i.e., 25 ± 2 °C).

pH Measurement of the gels before drying

The pH of the gel samples before drying was recorded with the help of a digital pH meter (Elmetron CP501, Poland) using a glass electrode and a temperature probe. The instrument’s calibration was performed using solutions prepared from commercially available buffer tablets of pH 4.00 and 7.00 (Merck, Germany).

Drying Time and drying rate of the xerogels

The placebo and DH-containing solutions poured into the Petri dishes were weighed on a weighing balance (ALS 220-4, KERN, Germany) at 0, 24, 48, 72, 78, 84, 90, 96, 102, 108, 114, and 120 h. The weighing was continued until the samples reached a constant weight. The following formula determined the drying rate:

where N = Drying rate, W0 = Weight of the sample at zero-time (minus the weight of the Petri dish), WD = Weight of the sample after drying (minus the weight of the Petri dish), t = Drying time.

Thickness of the xerogels

The thickness of the xerogels was measured using a calibrated digital vernier caliper (Insize, 1108-150, China). Each sample measurement was made in a triplet.

Moisture content determination of the xerogels

Moisture content (MC) was calculated by pre-weighing 10 × 10 mm of the xerogel and thoroughly drying it at 100 °C in a hot air oven (Memmert, Germany) for 60 min. The MC of the dried xerogel samples was determined after reweighing the samples using the following formula34,35,36:

where Wgel is the pre-drying weight of the xerogel, Wdry is the post-drying weight of the xerogel.

Swelling index of the xerogels

The basic steps in calculating the swelling index (SI) ratio are the same as those discussed in the section on MC. The dried samples were weighed and placed on a porous aluminum foil (porous to act as a sieve). The foil containing the dried sample was placed in a Petri dish filled with simulated saliva (pH 6.8) and left for 15 min. to swell. The additional saliva was removed, and the sample was reweighed. The following formula was used to determine the SI ratio37,38,39,40,41:

where Wswell is the weight of the swelled xerogel sample, Wdry is the weight of the dried xerogel sample.

Organoleptic studies

The organoleptic parameters of the xerogels were analyzed using a descriptive sensory analysis. A total of ten panelists with normal sensory acuity were included, trained, and oriented. They received a questionnaire (Table S1) with instructions on recording the perceived results42. The parameters of the questionnaire included fragrance, taste (taste and aftertaste), and texture [visual (color, gloss, smoothness, appearance) and tactile characteristics (roughness, hardness)]. The visual analysis was performed with the naked eye. The tactile elements were determined by retrieving a small piece and feeling it by holding it between the index finger and thumb, whereas other properties were evaluated visually. The study followed the Helsinki guidelines after approval from the Institutional Research and Ethics Board of Baqai Medical University ‘Ref: BMU-EC/03-2022’, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the xerogels

The surface topography of placebo and DH-loaded xerogels was performed using a scanning electron microscope (JSM-6380A, JEOL, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. Before the analysis, the samples were fixed on a 0.5-inch aluminum stub using carbon adhesives. Sputter coating (JFC-1500, JEOL, Japan) of the samples was performed using gold to make the samples electrically conducive. Various magnifications were chosen to obtain the best details of the samples.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometric analysis of the xerogels

FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet iS5, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was used to record the IR spectra of all the raw materials, their physical mixtures, and all xerogel samples. The physical mixtures were prepared in the same concentration as the formulations by mixing the drug powder with the polymer in a Petri dish with the help of a spatula for five minutes. The samples were placed on the diamond crystal optical base (iD7 ATR, ThermoFisher Scientific, Great Britain). Each spectra was recorded at 4 cm−1 with 128 scans between 4000 and 700 cm−1. The spectra were analyzed using Omnic software (version 9).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis of the xerogels

The thermal characteristics of the pure, physical mixtures and xerogel samples were assessed using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC 100, Lab-Kits, Hong Kong). DSC was purged with 20 ml/min nitrogen, and the data was processed using built-in Pyris software. Standard indium and zinc were used to calibrate the instrument. The DH-loaded xerogel samples were weighed in ceramic crucibles and heated to 400 °C at a rate of 10 °C per min. The samples were cooled at 20ºC per min. and the data was recorded until they reached room temperature.

In-vitro drug release kinetics of the xerogels

Drug release from the xerogels was performed using a dissolution apparatus basket method (Type I, GDT-6L, Galvano Scientific, Pakistan)43. Each xerogel sample (55 mm diameter) was placed into the basket that was rotated at a speed of 200 rpm into the dissolution vessels containing 600 ml of simulated saliva kept at a constant temperature of 37 ± 0.5 °C. The samples (5 ml each) were periodically withdrawn at 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 360, and 600 min. The volume of the withdrawn sample was replaced with a fresh medium to maintain the sink conditions. The samples were subjected to UV spectrometric assay (Evolution 201, ThermoFisher, USA) to quantify the amount of DH released from the xerogels.

The kinetics of the drug release from the xerogels was evaluated using the following equations44,45,46:

where C0 = initial concentration; Ct = concentration at time t; kH = Higuchi dissolution constant; k = release rate constant; n = slope.

Antibacterial analysis

The bacterial strains used in the study were Escherichia coli (ATCC 25,922), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27,853), and Streptococcus mutans (ATCC 35,668). The antibacterial activity of the samples was evaluated using the disc diffusion method. Tryptone soya agar (TSA) was used for E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa, and blood agar (i.e., TSA + human blood) was used for S. mutans47. A uniform amount (i.e., 19 ml) of media was poured into each petri dish to maintain the thickness of 4 mm in each plate. Each culture was standardized using the 0.5 McFarland standard. A uniform lawn of each bacterial culture was made on each plate using a sterile cotton swab. DH-loaded xerogels and placebo xerogel discs (5 × 5 mm) were inoculated at equal distances in the plates. The plates were incubated in an aerobic environment at 37 °C for 24 h, and the diameter of the growth inhibition zones surrounding each xerogel disc was measured in mm. DH solution (1%) was used as a control, and the discs (5 mm diameter) were prepared by pouring 5 μl of the solution onto it using a sterile micropipette. Each experiment was performed in triplicate for each sample.

Results and discussion

Development of the xerogels

The formulation ingredients possess good in-silico compatibility and are suitable for developing xerogels for periodontal applications31. The drug and polymer solutions prepared in 0.25 M HCl appeared homogenous. A total of 12 xerogels were prepared (Table 1) and subjected to various physical and chemical characterizations.

pH Measurement of the gels before drying

After the ingredients of the xerogels were carefully mixed, the pH of each gel was measured before it was placed in a Petri dish to begin the drying process. The placebo and DH-loaded gels showed nearly identical pH values (Table 2). No pH adjustment was made to the gels before drying. The paired sample two-tailed t-test comparing the pH values between the placebo and drug-loaded gels did not reveal any significant difference (p = 0.363). This finding implies that adding DH to the xerogel matrix did not result in a discernible shift in the medium acidity or alkalinity compared to the placebos.

Drying time and drying rate of the xerogels

The drying time, defined as the time a sample needs to lose its moisture at ambient temperature (i.e., 25 ± 2 °C), is influenced mainly by the polymer composition48. The drying time and rate are significantly influenced by temperature, humidity, and surface area49,50,51. It is crucial to remember that the raw materials’ moisture content may affect the drying time52. In this study, the samples were periodically weighed for a maximum of 120 h to determine the drying time, with the recorded drying time signifying the time taken for the samples to reach complete dryness (Table 2).

The drying time of the placebo xerogels was observed between 90 and102 h, while that of the drug-loaded xerogels was achieved between 66 and 86 h (Table 2). The high drying time is due to the viscous nature of the gels, which requires adequate time to transform into xerogels in ambient conditions. On the other hand, the time difference can be attributed to the supplementary mixing of the drug-loaded gels during their preparation, which results in some moisture loss. However, the drying rates showed no significant difference between the placebo and drug-containing xerogels of a similar type (i.e., X1 with X7, X2 with X8, etc.), and this slight difference can be attributed to factors such as those mentioned during the drying of the gels (Table 2).

It has also been observed that the drying rate is comparatively lower in most of the xerogels containing higher molecular weight polymers. These observations can be explained by the molecular weight of CHT, which influences the moisture release characteristics. Increasing the molecular weight of CHT leads to a decrease in hydration and, consequently, a reduction in drying rate31,53,54. Similarly, PEG is known for its hygroscopic nature, and its molecular weight is inversely related to its hygroscopicity. Thus, increasing the molecular weight of PEG reduces the hygroscopic potential, which reduces the drying rate55,56. It is, therefore, essential to understand variations in drying time to maintain consistent xerogel quality and improve drug delivery performance.

Thickness of the xerogels

Xerogels containing both types of polymers are thicker than those containing CHT only (Table 2). The higher molecular weight of the polymers seems to have little effect on the thickness of the xerogels (Table 2). These findings suggest that multi-polymer xerogel formulations may have advantages in periodontal applications. This could facilitate their application due to their thicker consistency without causing local irritation while maintaining steady drug delivery performance.

Moisture content of the xerogels

It is crucial to perform MC evaluation to predict the synthesized samples’ biocompatibility57. Generally, a higher MC in a sample indicates the presence of hydrophilic agents inside the xerogel matrix58. Additionally, high MC can predict increased microbial growth and decreased sample purity59. This study observed approximately 3–13% MC in the xerogels (Table 2). It is known that CHT possesses hygroscopic characteristics, mainly when dry60, while for PEG, it is reported that their hygroscopicity decreases with increasing molecular weight and that, in general, all PEGs with higher molecular weight to 4000 are non-hygroscopic60.

After heating the xerogels in a hot air oven, the CHT-containing xerogels showed no visible changes in their appearance. However, samples containing PEG showed a slight alteration in color, as PEGs are known to discolor at high temperatures60. Additionally, all samples were more fragile after being removed from the hot air oven. Furthermore, xerogel samples composed of MMW CHT and PEG displayed lower MC than xerogels with HMW (Table 2). This phenomenon can be explained by the longer molecular chains in HMW CHT and PEG, which results in better water absorption within the molecular structure due to hydrogen ligation with the terminal –OH groups56.

Surprisingly, the xerogels containing MMW PEG had a very low MC. This phenomenon can be explained by the possibility that the glass transition temperature of MMW PEG is lower than that of HMW PEG (Table 2). Therefore, MMW PEG can present a more soft and flexible polymeric structure, facilitating water absorption and forming compact and solid xerogels. This, in turn, decreases water dispersion and reduces moisture loss during heating. On the other hand, xerogels containing DH presented a lower MC than the placebo samples, probably due to the greater uniformity of xerogels obtained due to excessive mixing, as discussed earlier in the Drying Rate and Drying Time Section (Table 2). Understanding MC is essential to ensure adequate drug delivery, highlighting its importance in xerogel-based therapies. It is, therefore, necessary to evaluate the MC to ensure the purity and biocompatibility of xerogels, especially in local drug delivery applications in periodontal pockets. The observed MC, influenced by CHT and PEG, affects the physical characteristics and yield of xerogels.

Swelling index of the xerogels

PEG, CHT, and DH in the xerogels can absorb significant amounts of water61,62,63. The SI plays a vital role in evaluating the ability of dried xerogel samples to absorb moisture or water during storage64 or when exposed to the oral cavity. This parameter also provides information about the release characteristics of the drug from the xerogel65. The hydrophilic functional groups in the xerogel matrix, i.e., –OH, –NH2, and –COOH, play an essential role in the swelling behavior, allowing the xerogel to absorb significant fluid volumes66.

In this study, xerogel samples were dried according to the instructions provided in the section on MC, which resulted in physical changes similar to those mentioned previously. After immersion in artificial saliva, there was an increase in the weight and volume of the xerogel samples (Table 2). Xerogels containing CHT-only showed a more significant weight change with comparatively higher SI levels (X1 and X2, X7 and X8) than the samples containing both polymers (Table 2). It may have occurred due to comparatively increased water absorption in CHT since the pKa of CHT is ~ 6.567. The results are in accordance with those observed in the MC analysis, and the reasons could be the same as those already explained in that section.

On the other hand, adding PEG caused a decrease in the SI ratio of xerogels (Table 2), probably due to its presence in greater quantities (Table 1), making the polymeric matrix more dense and less sensitive to water. The SI relationship between MMW CHT and PEG was lower than that between HMW CHT and PEG (Table 2). This might have occurred due to the comparatively stronger binding of water with HMW polymers through hydrogen bonding56, as also observed in the MC analysis (Table 2). Xerogels containing DH showed comparatively lower SI than placebos, which may be attributed to the hydrogen bonding of DH with the polymers, which allows for relatively lower interaction between saliva and polymers (Table 2). A two-tailed t-test revealed a significant (p = 0.012) difference between placebo and drug-loaded xerogels. The study highlights the impact of polymer concentration variations, particularly CHT and PEGs, on the SI. The prepared xerogels thus show good swelling capability, enabling them to withstand the saliva and also avoid removal of the drug by the saliva from the periodontal pockets. It is essential to capture this dynamic to optimize xerogel formulations to ensure efficient drug delivery and achieve positive therapeutic outcomes during periodontal therapies.

Organoleptic studies

All xerogel samples were subjected to a thorough organoleptic analysis to assess the appearance and tactile properties, including the texture of the xerogels. Additionally, their sensory characteristics, such as odor, taste, and aftertaste, were evaluated.

Visual evaluation

The visual assessment of the xerogel samples revealed distinct characteristics (Table 3). MMW and HMW CHT-only xerogels (X1 and X2) exhibited mixed color shades of ‘5’ and ‘6’, featuring a matte, smooth, and unblemished surface. The xerogels with MMW CHT and MMW PEG (X3), as well as those with HMW CHT and MMW PEG (X5), were rated '4' and displayed a matte, grainy texture but remained unblemished. The xerogels with MMW CHT and HMW PEG (X4), as well as those with HMW CHT and HMW PEG (X6), earned a color rating of '5' and exhibited a matte, smooth, and unblemished appearance. On the other hand, DH-loaded xerogels exhibited the same appearance but with significant color change. The color of DH-loaded MMW CHT xerogels and HMW CHT xerogels (X7 and X8) is rated ‘6’. The DH-loaded xerogel with MMW CHT and MMW PEG (X9) and those with HMW CHT and MMW PEG (X10) were rated ‘5’ and ‘6’, respectively. The DH-loaded xerogels with MMW CHT and HMW PEG (X11) and HMW CHT and HMW PEG (X12) earned a color rating of '9'. The visual color comparison of the xerogels is shown in Fig. S1.

Tactile evaluation

The tactile examination of the xerogel samples revealed variations in surface texture (Table 3). All the xerogel samples (X1, X2, X3, and X5) showcased smooth and hard surfaces, except xerogels containing MMW CHT with HMW PEG (X4) and HMW CHT with HMW PEG (X6), which were characterized by a smooth and soft texture. The DH-loaded xerogels exhibited the same textures as those of the placebo xerogels. The variations observed could be due to the different molecular weights of PEG since HMW PEGs impart more remarkable plasticity or smoothness60, as observed in this study.

Olfactory evaluation

The olfactory assessment revealed a slight chemical (acid-like) smell in several xerogel samples (X3, X4, X5, X6) (Table 3). In contrast, no distinct smell was detected in CHT xerogels (X1 and X2). The DH-loaded xerogels exhibited the same smells as the placebo xerogels.

Gustatory evaluation

The gustatory evaluation of the xerogels revealed various taste characteristics (Table 3). CHT xerogels had a bitter taste (X1 and X2). Xerogels of MMW CHT with MMW PEG (X3) and HMW CHT with MMW PEG (X5) had a complex taste profile, including bitter and sour notes. Xerogels of MMW CHT with HMW PEG (X4) and HMW CHT with HMW PEG (X6) had a sour taste. The DH-loaded xerogels exhibited the same tastes as the placebo xerogels. All the xerogels are found to have a bitter aftertaste.

SEM analysis of the xerogels

The morphology and surface topography of placebo and drug-loaded xerogels have been examined using SEM, and their differences have been highlighted. According to SEM analysis, all xerogels exhibited a porous texture, consistent with previous research results31,68. The pore formation decreases with increasing molecular weights of both polymers (Fig. 2.1). The presence of the drug on the surface of the xerogels can also be visualized, particularly in the image of samples X7, X9, and X10 (Fig. 2.1).

Analysis of the cross-sectional area of the xerogel samples using SEM revealed rough and irregular surfaces, which became denser as the molecular weight of the polymers increased (Fig. 2.2). The origin of these differences lies in the different chemical reactions that occur during the formation phase of the xerogel. The use of HCl induces acetylation of CHT, which increases the molecular weight of CHT69,70, giving it a more dense appearance. The intermolecular interactions and hydrogen bonding between polymeric chains create voids, thus creating a porous structure71,72.

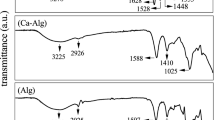

FTIR spectrometric analysis of the xerogels

It is of utmost importance to ensure the purity of the active drug and avoid any interaction with other materials when developing a dosage form for any delivery system. It is essential to identify any possible interferences from degrading products or unwanted impurities in the sample73. FTIR spectrometry was used to ascertain the purity of DH and all other excipients used to develop xerogels. Individual analyses of the raw materials showed that the significant peaks of all compounds (Fig. 3) are in accordance with their chemical structure and correspond to those reported in the literature that have been discussed in detail elsewhere31.

The FTIR analysis on the physical mixtures of DH with each excipient (Fig. 3) was also evaluated to identify any molecular interactions between them in the solid state. The physical combination of DH with CHT did not show any prominent changes in the spectrum. All major peaks were observed without significant alterations (Fig. 3). On the other hand, there was a slight broadening between 3500–3100 cm−1 and 3000–2700 cm−1, which corresponds to the stretching vibrations of O–H and N–H groups. Some minor variations in the peaks between 1700–1500 cm−1 that is attributed to the C=C, =O, and C–N stretching and N–H bending vibrations and 1100–900 cm−1, which are characterized by C–H asymmetric stretching, C–O–H bending, C–N stretching, C–O–C, C–H, and C–C ring vibrations have been noted when DH and PEG were mixed physically (Fig. 3). These changes indicate towards the formation of weak hydrogen bonds between the drug and PEG when mixed physically.

On the contrary, significant changes were observed when the xerogels were subjected to FTIR analysis, i.e., broadening, shifting, and disappearance of specific peaks, identified and compared in Table 4. These modifications confirm the formation of hydrogen bonds between the drug and polymers, as well as possible changes in the solid state characteristics of the drug, i.e., the transition from crystalline state to amorphous form during xerogel preparation (Fig. 3). It is evident from the spectra that both the drug and the polymers, particularly PEG, possess specific ionizable groups, i.e., OH and –NH (Fig. 3), which could result in the formation of hydrogen bonds between them (Fig. 3). The transformation in the solid state properties of DH could be confirmed by studying the thermal characteristics using DSC.

DSC analysis of the xerogels

DSC was used to evaluate the thermal characteristics of the raw materials, physical mixtures, and xerogel samples. DH displayed two melting peaks at 170.87 ± 3.20 °C and 225.98 ± 2.71 °C (Fig. 4.1a), corresponding to the melting of crystalline and semicrystalline particles of DH31,74,75,76,77,78. The CHT revealed a significant endothermic hump at approximately 50–150 °C (Fig. 4.1b), indicating water loss. In addition, CHT showed a melting peak at approximately 291.83 ± 4.89 °C (Fig. 4.1b), corresponding to the decomposition of their amine groups79,80,81. Interestingly, HMW CHT showed a steeper gradient than MMW CHT, suggesting more significant water loss and a more intense exothermic process82. PEG displayed a gradient of 64.60 ± 1.70 °C, suggesting its degradation, while it showed a significant exothermic hump at approximately 200–260 °C (Fig. 4.1c)83,84.

Regarding the physical mixtures, there was no significant change in thermal characteristics between DH and CHT (Fig. 4.1d), and there was only a slight decrease in the level of DH peak. On the other hand, shifting of the DH melting peak was observed in the DH and PEG physical mixture (Fig. 4.1e). This change in the thermal peak of DH testifies to an interaction between the two compounds. This interaction was also observed during the FTIR study of the two compounds (Fig. 3). The physical combination of all three compounds also showed a similar thermal graph with reduced DH peaks with a slight shift (Fig. 4.1f). The thermal variations of the physical mixtures of DH and PEG agree with the FTIR data, which further confirms the interaction and formation of hydrogen bonds between the two compounds.

The drug-loaded HCl-based xerogels showed similar changes with more profound results than the physical mixtures (Fig. 4.1g–l). No peak of DH in any of the xerogels has been observed (Fig. 4.1g–l). Thermal data confirmed that the solid-state characteristics of the drug have significantly changed, thus supporting the results of the FTIR analysis. The distinction between the xerogels thermograms of CHT-only (X7 and X8) and those containing PEG xerogels (X9–X12) is due to the presence of PEG in greater quantities, which highlights the thermal gradient (Fig. 4.1i–l).

Studying DSC thermograms during the cooling process can sometimes provide valuable information about recrystallization and the physical and chemical characteristics of the active drug. In this study, no peak of any sample during cooling has been noted, demonstrating good miscibility between the drug and the polymers (Fig. 4.2). Additionally, this suggests minimal likelihood of drug recrystallization upon moisture absorption, as SI studies also revealed minimal values for moisture absorption.

In-vitro drug release of the xerogels

The dissolution study was carried out to evaluate the DH release rate from different xerogel formulations. Since xerogels are intended to be used orally in periodontal pathologies, the dissolution tool used in this work was simulated saliva at a nearly neutral pH (pH 6.8). It is essential to consider this pH-dependent solubility when formulating DH for pharmaceutical applications. DH exhibits some intrinsic hydrophilicity, with solubility influenced by pH and other ions or molecules in the solution.

Both CHT and PEG are known to be biodegradable either alone or in combination60,85,86,87. During this study, all drug-loaded xerogels (X7–X12) were dissolved entirely in simulated saliva within 30 min. during dissolution studies. Likewise, the placebo xerogels showed a similar dissolution pattern. These results align with previous reports85,86,87, thus proposing that both CHT-only xerogels (X7 and X8) and CHT-PEG xerogels (X9–X12) will be easily degraded in the periodontal pockets.

In all xerogel formulations, more than 60% of the drug was found to be released during the initial 30 min. (Table S2). Thereafter, a plateau was achieved that showed a consistent slow release of DH till 10 h (Fig. 5). The initial rapid release of DH could be due to its chemical characteristics since it is inherently hydrophilic, with polar functional groups such as hydroxyl (–OH) and amino (–NH) groups. These polar groups can bond hydrogen and water molecules, facilitating DH dissolution in aqueous media88,89. The capability of DH to form hydrogen bonding has also been observed and discussed in the FTIR analysis section.

Nevertheless, it is essential to emphasize that the solubility of DH in water varies with pH, with increased solubility in acidic media and reduced solubility in neutral or alkaline media90,91. The pH of the gels before drying was acidic, leading to an increased burst of DH release initially. However, over time, the pH effect of the saliva could have impacted the xerogels, leading to a slow release later on. Moreover, the transformation of the drug from crystalline to an amorphous state also leads to an initial rapid release.

The molecular weight of CHT affects the release of DH since it gets slowed with an increase (Table S2). Comparatively, the impact of PEG molecular weight has not influenced the release rate significantly as much as CHT (Table S2). The highest release has been observed in xerogels containing MMW CHT and PEG, while the slowest release has been observed in those containing HMW CHT and PEG (Table S2). However, based on the release profile obtained for DH, it can be envisaged that it will be suitable for clinical use in treating periodontal diseases, particularly where an initial rapid antibiotic release is required.

Different release models were employed to predict the release kinetics of DH from the xerogels. The choice of the most appropriate release model was based on the quality of the fit, represented by the results of R2 regression (Table 5). It was noted that the cumulative logarithmic release of DH from the xerogels presented a relatively constant relationship with the logarithm of time, which corresponds to the Korsmeyer–Peppas model.

In-vitro in-vivo correlation (IVIVC)

DH is classified as a Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) Class I drug, characterized by high solubility and high permeability92,93. BCS Class I drugs are eligible for biowaivers. IVIVC is based on predictive mathematical models that describe the relationship between an in-vitro property of a dosage form and a relevant in-vivo response, thus avoiding the need to perform in-vivo studies92,93. Previously, our group predicted computationally that the DH-loaded CHT-PEG xerogels are highly suitable for localized drug delivery in the periodontium and expected to have no or minimal side effects with negligible systemic ADME. Furthermore, existing local drug delivery systems for periodontal diseases (i.e., Atridox®, containing 10% DH) have also demonstrated insignificant systemic absorption (i.e., 0.07–0.1 µg/ml)94.

However, based on the availability of in-vivo drug release data of DH from gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) in humans94, alongside the in-vitro release profiles obtained in this study, a multiple-level-C IVIVC has been established95,96 to assess the relationship between the two datasets. A graph was plotted between the log values of in-vivo release data of DH in GCF94 versus the in-vitro drug release of each drug-loaded sample of this study, and an IVIVC was made95,96. The results demonstrated a predominantly strong correlation, as evident from the regression values (Table 6), between in-vivo DH release in GCF and the in-vitro release observed in this study. Based on these findings, it is proposed that DH will have no or negligible systemic effects in the studied xerogel system.

Antibacterial analysis

The antibacterial activity of both placebo and drug-loaded xerogels was evaluated against the ATCC cultures of E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and S. mutans. It has been observed that significant antibacterial activity is present in both placebo and drug-loaded xerogels. CHT is responsible for the antibacterial activity of placebo xerogels60,97,98. DH is a versatile antibiotic known for acting against Gram-positive and negative bacteria, including S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, S. mutans, and E. coli99,100,101,102,103,104. When comparing the results, it was observed that the activity of the drug-loaded xerogels was more significant than that of the control, as well as that of their placebos against all the tested bacteria (Table 7). It was further confirmed statistically, and a significant difference (p < 0.05) was noted between placebo and drug-loaded xerogels when a paired sample two-tailed t-test was applied against E. coli (p = 0.0001), S. aureus (p = 0.001), P. aeruginosa (p = 0.011), and S. mutans (p = 0.00035).

S. mutans is considered one of the most critical bacteria forming dental caries. As a result, significant activity against it testifies to the effectiveness of xerogels in treating oral dental conditions. It is possible that the acidic nature of the xerogels played a crucial role in inhibiting the bacteria because their growth is also influenced by the pH of the medium100,104.

The MIC90 (minimum inhibitory concentration for 90% of isolates) of DH against red-complex bacteria that is predominantly responsible for the progression of the periodontal disease is reported to be 0.063 and 0.8 µg/ml105,106,107,108. In comparison, the MIC90 values for the bacteria tested in this study are reported109 as 0.5 µg/ml (E. coli), 0.25 µg/ml (S. aureus), 4 µg/ml (P. aeruginosa), and 3.9 µg/ml (S. mutans)110. Based on the findings of release and antibacterial analysis of this study, incorporating 1% DH in xerogels (X7–X12) is expected to demonstrate strong clinical efficacy within periodontal pockets. Since the amount released from the xerogels (Table S2) far exceeds the 4 µg/ml threshold, ensuring effective inhibition of pathogenic bacteria. However, further detailed studies in this regard would be beneficial for determining the optimum dose or minimum inhibitory concentration of the drug in the xerogel system.

Conclusion

The placebo and DH-loaded xerogels were developed and characterized using various analytical techniques. The solvent selection is critical in making the xerogels as it may significantly affect the physicochemical properties. The results showed that DH-loaded xerogels displayed different release profiles, having a rapid release of the bulk of the drug in 30 min. The results are promising for the pharmaceutical industry, especially in localized drug delivery within periodontal pockets to treat acute periodontal pathologies. This method can increase bioavailability and reduce systemic side effects, making it a valuable tool for dentists. This approach may improve treatment outcomes while reducing unwanted systemic adverse effects when treating various periodontal conditions. Further studies on stability, cytotoxicity, clinical efficacy, and pharmacokinetics would be of prime importance for commercializing the product.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

da Fonseca, L. S. et al. Nanocapsule@xerogel microparticles containing sodium diclofenac: A new strategy to control the release of drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 358, 292–295 (2008).

Wu, Z., Joo, H., Tai, G. L. & Lee, K. Controlled release of lidocaine hydrochloride from the surfactant-doped hybrid xerogels. J. Control. Releas. 104, 497–505 (2005).

Radin, S. & Ducheyne, P. Controlled release of vancomycin from thin sol–gel films on titanium alloy fracture plate material. Biomaterials 28, 1721–1729 (2007).

Barbé, C. et al. Silica particles: A novel drug-delivery system. Adv. Mater. 16, 1959–1966 (2004).

Maver, U. et al. Novel hybrid silica xerogels for stabilization and controlled release of drug. Int. J. Pharm. 330, 164–174 (2007).

Santos, E. M., Radin, S., Shenker, B. J., Shapiro, I. M. & Ducheyne, P. Si-Ca-P xerogels and bone morphogenetic protein act synergistically on rat stromal marrow cell differentiation in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 41, 87–94 (1998).

Roveri, N., Morpurgo, M., Palazzo, B., Parma, B. & Vivi, L. Silica xerogels as a delivery system for the controlled release of different molecular weight heparins. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 381, 601–606 (2005).

Sieminska, L., Ferguson, M., Zerda, T. W. & Couch, E. Diffusion of steroids in porous sol–gel glass: Application in slow drug delivery. J. Sol–Gel Sci. Technol. 81(8), 1105–1109 (1997).

Limón, D. et al. Cationic supramolecular hydrogels for overcoming the skin barrier in drug delivery. ChemistryOpen 6, 585–598 (2017).

Idumah, C. I. Characterization and fabrication of xerogel polymeric nanocomposites and multifunctional applications. Res. Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/RS.3.RS-1961392/V1 (2022).

Slavkova, M., Tzankov, B., Popova, T. & Voycheva, C. Gel Formulations for topical treatment of skin cancer: A review. Gels 9, 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9050352 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Antibacterial, antioxidant and biocompatible nanosized quercetin-PVA xerogel films for wound dressing. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces 209, 112175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.112175 (2022).

Elshishiny, F. & Mamdouh, W. Fabrication of nanofibrous/xerogel layer-by-layer biocomposite scaffolds for skin tissue regeneration: In vitro study. ACS Omega 5, 2133–2147 (2020).

Meza-Valle, K. Z. et al. Characterization and topical study of aloe vera hydrogel on wound-healing process. Polymers (Basel) 13, 3958. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13223958 (2021).

Rajalekshmy, G. P. & Rekha, M. R. Strontium ion cross-linked alginate-g-poly (PEGMA) xerogels for wound healing applications: In vitro studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 251, 117119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117119 (2021).

Khalil, A. P. S. A., Yahya, E. B., Tajarudin, H. A., Balakrishnan, V. & Nasution, H. Insights into the role of biopolymer-based xerogels in biomedical applications. Gels 8, 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels8060334 (2022).

Boateng, J., Mitchell, J., Pawar, H. & Ayensu, I. Functional characterisation and permeation studies of lyophilised thiolated chitosan xerogels for buccal delivery of insulin. Protein Pept. Lett. 21, 1163–1175 (2014).

Ayensu, I., Mitchell, J. C. & Boateng, J. S. In vitro characterisation of chitosan based xerogels for potential buccal delivery of proteins. Carbohydr. Polym. 89, 935–941 (2012).

Niknia, N. & Kadkhodaee, R. Gum tragacanth-polyvinyl alcohol cryogel and xerogel blends for oral delivery of silymarin: Structural characterization and mucoadhesive property. Carbohydr. Polym. 177, 315–323 (2017).

Kubis, A. & Malecka, K. Studies on dressings for mucosa of oral cavity. Part 1: Influence of hydrophilizing substances of xerogel properties of dressings comprising Kunitz protease inhibitor. Pharmazie 43, 486–488 (1988).

Malecka, K. & Kubis, A. Studies on dressings for treatment of mucous membranes of oral cavity. Part 2: Influence of hydrophilizing substances on properties of hydrogel dressings comprising Kunitz protease inhibitor. Pharmazie 43, 694–696 (1988).

Małecka, K. & Kubis, A. Studies on dressings for mucosa of the oral cavity. Part 3: Effect of preparation technology on the physical and chemical properties of stomatological xerogel dressings. Pharmazie 51, 240–241 (1996).

Malecka, K. & Kubis, A. A. Studies on dressings for mucosa of the oral cavity. Part 4: Influence of technology used in the preparation of dental xerogel dressings in the presence of acetone on their properties. Pharmazie 53, 396–398 (1998).

Malecka, K. & Kubis, A. A. Studies on dressings for oral cavity mucosa. Part 5: Properties of xerogel stomatological dressings with one-side antiadhesive coating. Pharmazie 56, 64–65 (2001).

Malecka, K. & Kubis, A. A. Studies on dressings for mucosal oral cavity. Part 6: Influence of a solvent and 1,2-propylene glycol on the pharmaceutic properties of dental xerogel dressings. Pharmazie 56, 669–670 (2001).

Schubert, U. Chemistry and Fundamentals of the Sol–Gel Process in Sol–Gel handbook 1st edn, 1–28 (Wiley-VCH, 2015).

Artaki, I., Zerda, T. W. & Jonas, J. Solvent effects on the condensation stage of the sol–gel process. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 81, 381–395 (1986).

Lorjai, P., Chaisuwan, T. & Wongkasemjit, S. Porous structure of polybenzoxazine-based organic aerogel prepared by sol–gel process and their carbon aerogels. J. Sol–Gel Sci. Technol. 52, 56–64 (2009).

Feinle, A., Elsaesser, M. S. & Hüsing, N. Sol–gel synthesis of monolithic materials with hierarchical porosity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 3377–3399 (2016).

Lofgreen, J. E. & Ozin, G. A. Controlling morphology and porosity to improve performance of molecularly imprinted sol–gel silica. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 911–933 (2014).

Zafar, F. et al. Novel antibiotic-loaded pegylated xerogels of acidified chitosan for periodontal diseases. Curr. Drug Deliv. 22, 1–21 (2025).

Zhu, G. & Dordick, J. S. Solvent effect on organogel formation by low molecular weight molecules. Chem. Mater. 18, 5988–5995 (2006).

Farjami, T. & Madadlou, A. An overview on preparation of emulsion-filled gels and emulsion particulate gels. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 86, 85–94 (2019).

Curcio, M. et al. Grafted thermo-responsive gelatin microspheres as delivery systems in triggered drug release. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 76, 48–55 (2010).

Bao, Y., Ma, J. & Li, N. Synthesis and swelling behaviors of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose-g-poly(AA-co-AM-co-AMPS)/MMT superabsorbent hydrogel. Carbohydr. Polym. 84, 76–82 (2011).

Nesseem, D. I., Eid, S. F. & El-Houseny, S. S. Development of novel transdermal self-adhesive films for tenoxicam, an anti-inflammatory drug. Life Sci. 89, 430–438 (2011).

Rokhade, A. P. et al. Semi-interpenetrating polymer network microspheres of gelatin and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose for controlled release of ketorolac tromethamine. Carbohydr. Polym. 65, 243–252 (2006).

Mishra, R. K., Datt, M. & Banthia, A. K. Synthesis and characterization of pectin/PVP hydrogel membranes for drug delivery system. AAPS PharmSciTech 9, 395–403 (2008).

Oprea, A.-M. et al. Cellulose/chondroitin sulfate hydrogels: Synthesis, drug loading/release properties and biocompatibility. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 44, 369 (2010).

Jana, S. & Sen, K. K. Gellan gum/PVA interpenetrating network micro-beads for sustained drug delivery. Mater. Today Proc. 11, 614–619 (2019).

Franklin, D. S. & Guhanathan, S. Synthesis and characterization of citric acid-based pH-sensitive biopolymeric hydrogels. Polym. Bull. 71, 93–110 (2014).

Murray, J. M., Delahunty, C. M. & Baxter, I. A. Descriptive sensory analysis: Past, present and future. Food Res. Int. 34, 461–471 (2001).

British Pharmacopoeia Commission. British Pharmacopoeia (2024 ed.) (Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 2023).

Furqan Ahsan, S. et al. Formulation and stability studies of fast disintegrating tablets of amlodipine besylate. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 53, 480–493 (2019).

Higuchi, T. Rate of release of medicaments from ointment bases containing drugs in suspension. J. Pharm. Sci. 50, 874–875 (1961).

Helal, D. A., Abd El-Rhman, D., Abdel-Halim, S. A. & El-Nabarawi, M. A. Formulation and evaluation of fluconazole topical gel. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 4, 176–183 (2012).

Krzyściak, W., Kościelniak, D., Papiez, M., Jurczak, A. & Vyhouskaya, P. Methods of biotyping of Streptococcus mutans species with the routine test as a prognostic value in early childhood caries. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 6859543. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6859543 (2017).

Waje, S. S. et al. Drying and shrinkage of polymer gels. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 22, 209–216 (2005).

Satha, H., Atamnia, K. & Despetis, F. Effect of drying processes on the texture of silica gels. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 04, 17–21 (2013).

Simpkins, P. G., Johnson, D. W. & Fleming, D. A. Drying behavior of colloidal silica gels. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 72, 1816–1821 (1989).

Miranda, M., Maureira, H., Rodríguez, K. & Vega-Gálvez, A. Influence of temperature on the drying kinetics, physicochemical properties, and antioxidant capacity of Aloe Vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) gel. J. Food Eng. 91, 297–304 (2009).

Tsagareishvili, D., Sesikashvili, O., Dadunashvili, G., Sakhanberidze, N. & Tsagareishvili, S. The influence of the moisture content of raw materials on the structuring of the extrudates. Potravin. Slovak J. Food Sci. 13, 898–905 (2019).

Krisanti, E., Aryani, S. D. & Mulia, K. Effect of chitosan molecular weight and composition on mucoadhesive properties of mangostin-loaded chitosan-alginate microparticles in AIP Conference Proceedings (American Institute of Physics Inc., 2017).

Kubota, N. & Kikuchi, Y. Preparation and properties of macromolecular complexes consisting of [2-(diethylamino)ethyl]dextran hydrochloride and potassium metaphosphate. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 47, 815–821 (1993).

Baird, J. A., Van Eerdenbrugh, B. & Taylor, L. S. A classification system to assess the crystallization tendency of organic molecules from undercooled melts. J. Pharm. Sci. 99, 3787–3806 (2010).

Kapanya, A., Somsunan, R., Phasayavan, W., Molloy, R. & Jiranusornkul, S. Effect of molecular weight of poly(ethylene glycol) as humectant in interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels based on poly(sodium AMPS) and gelatin for wound dressing applications. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 70, 496–506 (2021).

Cadée, J. A. et al. In vivo biocompatibility of dextran-based hydrogels. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 50, 397–404 (2000).

Ahmed, E. M. Hydrogel: Preparation, characterization, and applications—A review. J. Adv. Res. 6, 105–121 (2015).

Stark, J. M. & Firestone, M. K. Mechanisms for soil moisture effects on activity of nitrifying bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 218–221 (1995).

Sheskey, P. J., Cook, W. G. & Cable, C. G. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients 8th edn. (Pharmaceutical Press, 2017).

Tao, R. E., Prajapati, S., Pixley, J. N., Grada, A. & Feldman, S. R. Oral tetracycline-class drugs in dermatology: Impact of food intake on absorption and efficacy. Antibiotics 12, 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071152 (2023).

Albers, P. T. M., Van Der Ven, L. G. J., Van Benthem, R. A. T. M., Esteves, A. C. C. & De With, G. Water swelling behavior of poly(ethylene glycol)-based polyurethane networks. Macromolecules 53, 862–874 (2020).

Bajpai, M., Bajpai, S. K. & Jyotishi, P. Water absorption and moisture permeation properties of chitosan/poly(acrylamide-co-itaconic acid) IPC films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 84, 1–9 (2016).

Yousf, N., Nazir, F., Salim, R., Ahsan, H. & Sirwal, A. Water solubility index and water absorption index of extruded product from rice and carrot blend. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 6, 2165–2168 (2017).

Agarwal, S. & Murthy, R. S. R. Effect of different polymer concentration on drug release rate and physicochemical properties of mucoadhesive gastroretentive tablets. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 77, 705–714 (2015).

Ahmadi, F., Oveisi, Z., Samani, M. & Amoozgar, Z. Chitosan based hydrogels: Characteristics and pharmaceutical applications. Res. Pharm. Sci. 10, 1–16 (2015).

Mohammed, M. A., Syeda, J. T. M., Wasan, K. M. & Wasan, E. K. An overview of chitosan nanoparticles and its application in non-parenteral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 9, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics9040053 (2017).

Zhang, Q., Li, X., Zhao, Y. & Chen, L. Preparation and performance of nanocomposite hydrogels based on different clay. Appl. Clay Sci. 46, 346–350 (2009).

Santoso, J., Adiputra, K. C., Soerdirga, L. C. & Tarman, K. Effect of acetic acid hydrolysis on the characteristics of water soluble chitosan. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 414, 7029–7032 (2020).

Rinaudo, M., Pavlov, G. & Desbrières, J. Influence of acetic acid concentration on the solubilization of chitosan. Polymer (Guildf). 40, 7029–7032 (1999).

Inan, T., Dalgakiran, D., Kurkcuoglu, O. & Güner, F. S. Elucidating doxycycline loading and release performance of imprinted hydrogels with different cross-linker concentrations: A computational and experimental study. J. Polym. Res. 28, 408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-021-02740-6 (2021).

Farkas, N. I. et al. Preparation and characterization of doxycycline-loaded electrospun pla/hap nanofibers as a drug delivery system. Materials (Basel) 15(6), 2105. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15062105 (2022).

Fanelli, S., Zimmermann, A., Totóli, E. G. & Salgado, H. R. N. FTIR spectrophotometry as a green tool for quantitative analysis of drugs: Practical application to amoxicillin. J. Chem. 2018, 3920810. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3920810 (2018).

Kogawa, A. C., Zoppi, A., Quevedo, M. A., Nunes Salgado, H. R. & Longhi, M. R. Increasing doxycycline hyclate photostability by complexation with β-cyclodextrin. AAPS PharmSciTech 15, 1209–1217 (2014).

Jia, L. N. et al. Development of a doxycycline hydrochloride-loaded electrospun nanofibrous membrane for GTR/GBR applications. J. Nanomater. 2016, 6721806. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6507459 (2016).

Honary, S. & Zahir, F. Effect of process factors on the properties of doxycycline nanovesicles. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 11, 169–175 (2012).

Hosseini, S. M. et al. Doxycycline-encapsulated solid lipid nanoparticles as promising tool against Brucella melitensis enclosed in macrophage: A pharmacodynamics study on J774A.1 cell line. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 8, 1–12 (2019).

De Cicco, F. et al. Prilling and supercritical drying: A successful duo to produce core-shell polysaccharide aerogel beads for wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 147, 482–489 (2016).

Acosta-Ferreira, S. et al. Production and physicochemical characterization of chitosan for the harvesting of wild microalgae consortia. Biotechnol. Rep. 28, e00554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00554 (2020).

Song, H. et al. Homogeneous synthesis of cationic chitosan via new avenue. Molecules 23, 1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23081921 (2018).

Ferrero, F. & Periolatto, M. Antimicrobial finish of textiles by chitosan UV-curing. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 12, 4803–4810 (2012).

Campos, J., Díaz-García, P., Montava, I., Bonet-Aracil, M. & Bou-Belda, E. Chitosan pretreatment for cotton dyeing with black tea. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 254, 112001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/254/11/112001 (2017).

Jayaramudu, T. et al. Preparation and characterization of poly(ethylene glycol) stabilized nano silver particles by a mechanochemical assisted ball mill process. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 133, 43027. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.43027 (2016).

Biswal, S., Sahoo, J. & Murthy, P. N. Characterisation of gliclazide-PEG 8000 solid dispersions. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 8, 417–424 (2009).

Hashemi Doulabi, A., Mirzadeh, H., Imani, M. & Bagheri-Khoulenjani, S. Chitosan/polyethylene glycol fumarate blend films for wound dressing application: In vitro biocompatibility and biodegradability assays. Prog. Biomater. 7, 143–150 (2018).

Pereira, I. C., Duarte, A. S., Neto, A. S. & Ferreira, J. M. F. Chitosan and polyethylene glycol based membranes with antibacterial properties for tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 96, 606–615 (2019).

Hasan, M. M. et al. Fabrication and characterization of chitosan-polyethylene glycol (Ch-PEG) based hydrogels and evaluation of their potency in rat skin wound model. Int. J. Biomater. 2021, 4877344. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4877344 (2021).

Cunha, B. A., Sibley, C. M. & Ristuccia, A. M. Doxycycline. Ther. Drug Monit. 4, 115–135 (1982).

Puyathorn, N., Senarat, S., Lertsuphotvanit, N. & Phaechamud, T. Physicochemical and bioactivity characteristics of doxycycline hyclate-loaded solvent removal-induced ibuprofen-based in situ forming gel. Gels 9, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9020128 (2023).

Bogardus, J. B. & Blackwood, R. K. Dissolution rates of doxycycline free base and hydrochloride salts. J. Pharm. Sci. 68, 1183–1184 (1979).

Legendre, A. O. et al. Solid state chemistry of the antibiotic doxycycline: Structure of the neutral monohydrate and insights into its poor water solubility. CrystEngComm 14, 2532–2540 (2012).

Jantratid, E. et al. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Doxycycline hyclate. J. Pharm. Sci. 99, 1639–1653 (2010).

Strauch, S., Jantratid, E. & Dressman, J. B. Comparison of WHO and US FDA biowaiver dissolution test conditions using bioequivalent doxycycline hyclate drug products. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 61, 331–337 (2009).

Stoller, N. H., Johnson, L. R., Trapnell, S., Harrold, C. Q. & Garrett, S. The pharmacokinetic profile of a biodegradable controlled-release delivery system containing doxycycline compared to systemically delivered doxycycline in gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, and serum. J. Periodontol. 69, 1085–1091 (1998).

Chilukuri, D. M., Sunkara, G. & Young, D. Pharmaceutical Product Development: In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation. Pharmaceutical Product Development: In Vitro-In Vivo Correlation 1st edn. (Informa Healthcare, 2007).

Bhise, S. B., Dias, R. J., Dhawale, S. C. & Mali, K. K. Laboratory Manual of Biopharmaceutics and Pharmacokinetics 1st edn. (Trinity Publishing House, 2010).

Goy, R. C., Morais, S. T. B. & Assis, O. B. G. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of chitosan and its quaternized derivative on E. coli and S. aureus growth. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 26, 122–127 (2016).

Tsai, G. J. & Su, W. H. Antibacterial activity of shrimp chitosan against Escherichia coli. J. Food Prot. 62, 239–243 (1999).

Krakauer, T. & Buckley, M. Doxycycline is anti-inflammatory and inhibits Staphylococcal exotoxin-induced cytokines and chemokines. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 3630–3633 (2003).

Aleanizy, F. S. et al. Measurement and evaluation of the effects of pH gradients on the antimicrobial and antivirulence activities of chitosan nanoparticles in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Saudi Pharm. J. 26, 79–83 (2018).

de Carvalho, L. D. et al. Doxycycline release and antibacterial activity from PMMA/PEO electrospun fiber mats. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 27, e20180663. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0663 (2019).

Gaurav, A., Kothari, A., Omar, B. J. & Pathania, R. Assessment of polymyxin B–doxycycline in combination against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 56, 106022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106022 (2020).

Jodlowski, T., Ashby, C. R. & Nath, S. G. Doxycycline for ESBL-E cystitis. Clin Infect. Dis. 73, e274–e275. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1898 (2021).

Costa, F. G. & Horswill, A. R. Overcoming pH defenses on the skin to establish infections. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010512. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010512 (2022).

Mandell, G. L., Bennette, J. E. & Dolin, R. Principles and Practices of Infectious Diseases 6th edn. (Elsevier Health Sciences, 1990).

Cortellini, P., Pini-Prato, G. & Tonetti, M. Periodontal regeneration of infrabony defects (V). Effect of oral hygiene on long-term stability. J. Clin. Periodontol. 21, 606–610 (1994).

Southard, G. L. 2 multi-center trials assessing the clinical efficacy of 5% sanguinarine in a biodegradable drug delivery system. J. Clin. Periodontol. 23, 782–788 (1996).

Polson, A. M. et al. Multi-center comparative evaluation of subgingivally delivered sanguinarine and doxycycline in the treatment of periodontitis. I. Study design, procedures, and management. J. Periodontol. 68, 110–118 (1997).

Petkova, T., Rusenova, N., Danova, S. & Milanova, A. Effect of N-acetyl-l-cysteine on activity of doxycycline against biofilm-forming bacterial strains. Antibiotics 12, 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071187 (2023).

Mostafa, E. M., Badr, Y., Hashem, M. M., Abo-EL-Sooud, K. & Faid, A. H. Reducing the effective dose of doxycycline using chitosan silver nanocomposite as a carriers on gram positive and gram-negative bacteria. Sci. Rep. 14, 27819. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78326-1 (2024).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.Z., M.A.S., S.A.A. Data Curation: F.Z., M.R. Formal Analysis: F.Z., M.R., S.H.K., S.T. Investigation: F.Z., M.R. Methodology: F.Z., M.A.S., S.A.A. Project Administration: M.A.S., S.A.A., S.A., Z.A. Resources: M.A.S., S.A.A., S.A., Z.A. Supervision: M.A.S., S.A.A., S.A., Z.A. Writing—Original Draft: F.Z. Writing—Review and Editing: F.Z., M.A.S., S.A.A., M.R., S.A., S.H.K., S.T., Z.A.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study followed the Helsinki guidelines after approval from the Institutional Research and Ethics Board of Baqai Medical University’ Ref: BMU-EC/03–2022’, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zafar, F., Sheraz, M.A., Ali, S.A. et al. PEGylated chitosan xerogels for localized periodontal therapy: design, characterization, and drug release. Sci Rep 15, 20519 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05894-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-05894-1