Abstract

Cancer confers the risk for cardiovascular diseases. This longitudinal study aimed to explore the relationship between changes in aortic morphology and muscle mass in cancer. One hundred patients with cancer who underwent thoracoabdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) at baseline and 1-year follow-up were retrospectively included. Aortic diameter and tortuosity were assessed using CT. Skeletal muscle mass was also evaluated. Pearson correlation analysis and multivariate-adjusted regression models were used to explore the relationship between changes in aortic morphology and muscle mass. Thirty-six patients were male. The average patient age was 57.3 ± 11.3 years. Breast cancer was the most common malignancy. A significant increase in aortic diameter and tortuosity and a decrease in muscle mass were observed. Aortic morphological changes were correlated with changes in muscle mass, diastolic pressure, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and C-reactive protein levels. In the fully adjusted multivariable regression analysis, a one-unit increase in muscle mass change was associated with a decrease of 0.503, 0.382, 0.241, 0.174, and 0.163 mm in the diameter of the L1-L5 aortic segments, respectively; a 0.020 decrease in aortic tortuosity; a 0.017 decrease in descending thoracic tortuosity; and a 0.016 decrease in abdominal aortic tortuosity. Increased muscle mass helps maintain aortic morphology in cancer, suggesting that muscle loss is a key factor in increased cardiovascular risk. Muscle might be an important therapeutic target to improve cancer patients’ prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer are the leading causes of death globally1. Improvements in technological advancements and cancer treatments have resulted in an overall decline in the cancer-related mortality rate, leading to more patients surviving longer and likely developing a secondary chronic disease. A study showed that 25% of patients with cancer had CVD, and the rate of first hospitalization for CVD in these patients was 30% higher than that in the general population2. Moreover, the CVD mortality risk is the highest within the first year after cancer diagnosis3. The increased CVD burden not only decreases the quality of life but also increases the cost of care in cancer survivorship4. Therefore, it is crucial to prevent CVD in patients with cancer.

Aortic morphological changes, such as tortuosity and dilation, are closely related to the occurrence and development of cardiovascular disease. These variations induce changes in haemodynamic processes, thereby increasing the burden on cardiovascular system and risk of cardiovascular disease. It is reported that the intricate geometrical features of aorta have prominent effects on haemodynamics5. What’s more, irregular contour and large degree of curvature of aorta might affect flow variables and wall shear stress, which is related to atheroma and aneurismal diseases6. Morphological changes in the aorta are also related to hypertension, aortic dissection and heart failure3. In addition, aortic dilation and tortuosity are closely associated with vascular remodeling, inflammation and oxidation that play a vital role in pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease7. Previous studies have indicated that arterial stiffness increases in patients with cancer8. Hence, accurate evaluations of aortic dilation and tortuosity are of great significance in predicting, preventing, and treating CVD in patients with cancer. Developments in imaging technology have facilitated comprehensive and systematic evaluation of aortic morphology. The overlap between cancer and CVD provides opportunities to assess both diseases concurrently through the use of computed tomography (CT), and CT is convenient in this context, with its 3D capabilities permitting reproducible and accurate measurements9.

Skeletal muscle is considered a biomechanical and endocrine organ, which plays important roles in health. Several studies revealed the prevalence of low muscle mass in patients with cancer10,11,12. What’s more, low muscle mass is related to cancer-related mortality13. Ko et al.14 showed that low muscle mass is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease. Meanwhile, other research works suggested that lower skeletal muscle mass was related to metabolic syndrome, atherosclerotic CVD, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and atrial fibrillation15,16. Our previous study also found an association between skeletal muscle index and aortic diameter and tortuosity17. Hence, we hypothesized that aortic morphological changes were related to lower muscle mass in patients with cancer.

Materials

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’ an Jiaotong University. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Subjects

The study included patients with cancer who underwent thoracoabdominal enhanced CT for disease evaluation between April 2022 and June 2024. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with diabetes, hypertension, or kidney disease; (2) patients with dissection, aneurysms, vascular malformation, or any variations on CT; (3) patients whose CT images showed artifacts; (4) patients for whom the follow-up duration was less than 1 year; (5) patients for whom the life expectancy was less than two years; and (6) patients whose complete clinical information was not available for analysis.

Characteristic collection

Information on the variables of interest such as age, sex, height, weight, systolic pressure, and diastolic pressure was collected. The primary tumor origin was also recorded. Peripheral blood was obtained with the patients in the supine position within 24 h of admission. Levels of triglycerides, low- and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C and HDL-C, respectively), total cholesterol, total protein, aspartate transaminase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, urea, creatinine, hemoglobin, fasting glucose, and C-reactive protein (CRP) as well as red blood cell, white blood cell, and platelet counts were determined. Biochemical indicators were determined using standard approaches.

CT image acquisition and evaluation of aortic diameter and tortuosity index

Thoracoabdominal enhanced CT data were collected at baseline and 1-year follow-up using two 256-slice CT scanners: Revolution CT (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) and Philips Brilliance iCT (Medical System, Best, The Netherlands). The parameters of CT scanning are presented in Supplementary Table 1. All patients accepted a standardized median cubital vein injection by power injector consisting of iomeprol with either 350 or 400 mg I/mL at a dose of 0.5 g I/kg and a rate of 2.7 mL/s follow by 30 mL saline chaser. CT was performed from lung apices to the iliac crest, without electrocardiography gating. All data were analyzed using a standard post-processing workstation (uInnovation-CT, R001, United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China). The outer edge-to-outer edge method was used to measure the aortic diameter at five levels, as described previously18: ascending aorta (L1), located 1 cm distal to the aortic valve; descending aorta (L2), in line with L1; the level of the diaphragm (L3); 3 cm above the level of aortic bifurcation (L5); and midway between L3 and L5 (L4). Each segment of the aorta was defined by two points corresponding to the anatomical landmark. An automated centerline between the two points was generated. The tortuosity index of the aorta was calculated using the following formula: tortuosity index = centerline length/straight-line length. The aortic diameter and tortuosity were quantitatively analyzed at baseline and 1-year follow-up. Moreover, to account for the effect of diverse body shapes on data analysis, the diameter and tortuosity were standardized by body surface area (BSA). BSA was calculated using the formula19: BSA (m2) = 0.007184 × height (cm)0.725 × weight (kg)0.425.

Evaluation of muscle mass using CT scans

The cross-sectional area of the mid-third lumbar (L3) vertebral muscle was considered as a proxy for muscle mass. 3D-Slicer software (Version 5.0.3, https://www.slicer.org/) was used to generate axial and sagittal CT images. Midline sagittal images were applied to determine the L3 level. Tissues with attenuation thresholds ranging from − 29 to 150 HU were automatically outlined on the corresponding axial image. The paraspinal, psoas, and abdominal wall muscles were manually delineated. After that, muscle mass can be automatically obtained. Muscle mass was quantitatively analyzed at baseline and 1-year follow-up. Finally, muscle mass was standardized by BSA.

The intraobserver and interobserver reliability were evaluated for aortic diameter, tortuosity index and muscle mass. Two experienced radiologists (L.G. and Z.J.J., both with 6 years of experience in cardiovascular imaging) perfomed the measurements independently and the time interval of the two repeated measurements for assessing the intraobserver reliability was 3 months. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and Bland-Altman plots were used to evaluate the intraobserver and interobserver reliability.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc (MedCalc 13.0, Mariakerke, Belgium). ICC and Bland-Altman plots were used for consistency. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (percentage), as appropriate. Differences between baseline and 1-year follow-up were assessed using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed rank test according to whether the data showed normal distribution. Pearson correlation analysis was used to analyze the relationship between the changes in morphological features and those in the potential influencing factors. Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to assess if the change in muscle mass was associated with changes in the morphological characteristics of the aorta. Age, sex, and body mass index (BMI) were adjusted for model 1, and age, sex, BMI, changes in HDL-C level, diastolic pressure, and CRP were adjusted for model 2. Linear regression coefficient and the 95% confidence interval (CI) have been reported. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

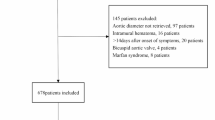

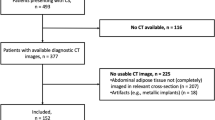

The study flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. Overall, 100 patients (64 women and 36 men) were enrolled in this study; the average patient age was 57.3 ± 11.3 years. All patients had malignant tumors. Most tumors were those of the breast (36%) and lungs (32%). Additionally, a considerable number of tumors were urinary carcinomas/carcinomas of the reproductive system (22%). The detailed baseline demographic information and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

The intraobserver reliability for measuring aortic diameters, tortuosity index and muscle mass was excellent, with values ranging from 0.880 to 0.989. In terms of interobserver reliability, the measurement of aortic diameters, tortuosity index and muscle mass also exhibited excellent values ranging from 0.868 to 0.984 (Supplementary Table 2).

The Bland-Altman plots indicated that the differences between the two repeated measurements fell within the limits of agreement (Supplementary Fig. 1A and 1B).

Quantitative changes in the regional morphology of the aorta are shown in Table 2. The aortic diameter and tortuosity were increased (L1: from 18.671 mm to 20.123 mm, percent change: 7.269%, p = 0.001; L2: from 12.791 mm to 14.101 mm, percent change: 10.371%, p < 0.001; L3: from 11.822 mm to 13.001 mm, percent change: 10.149%, p < 0.001; L4: from 9.015 mm to 10.074 mm, percent change: 12.250%; and L5: from 8.955 mm to 9.816 mm, percent change: 9.974%, p < 0.001; aortic tortuosity: from 1.152 to 1.195, percent change: 5.775%, p = 0.002; tortuosity of the descending thoracic aorta (DTA): from 1.135 to 1.183, percent change: 6.889%, p < 0.001; and tortuosity of the ascending aorta: from 0.663 to 0.696, percent change: 5.082%, p = 0.014) (Fig. 2).

Factors influencing aortic morphology at baseline and follow-up are shown in Table 3. Significant changes were found in HDL-C, LDL-C, systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, hemoglobin, and CRP. Moreover, muscle mass significantly decreased (Fig. 3). However, BMI and the levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting glucose did not change.

The correlations between aortic morphology and influencing factors are shown in Fig. 4. The changes in L1-L5 and tortuosity of the aorta, DTA, and AA were significantly correlated with the change in HDL-C (r = − 0.310, p = 0.002; r = − 0.221, p = 0.027; r = − 0.180, p = 0.043; r = − 0.226, p = 0.024; r = − 0.202, p = 0.043; r = − 0.174, p = 0.033; r = − 0.264, p = 0.008; r = − 0.221, p = 0.027, respectively) and muscle mass (r= − 0.347, p < 0.001; r = − 0.267, p = 0.007; r = − 0.265, p = 0.008; r = − 0.264, p = 0.008; r = − 0.239, p = 0.016; r = − 0.395, p < 0.001; r = − 0.363, p < 0.001; r = − 0.353, p < 0.001, respectively). We also found positive correlations between the change in CRP levels and those in aortic morphology (r = 0.257, p = 0.010; r = 0.242, p = 0.015; r = 0.220, p = 0.028; r = 0.212, p = 0.034; r = 0.205, p = 0.041; r = 0.382, p < 0.001; r = 0.195, p < 0.001; r = 0.173, p = 0.042). The change in diastolic pressure (L1-L4: r = 0.257, p = 0.010; r = 0.196, p = 0.049; r = 0.295, p = 0.003; r = 0.261, p = 0.009) only correlated with the change in the diameters of the proximal aortic segment. However, there was no remarkable relationship between the change in aortic morphology and that in systolic pressure (r = 0.128, p = 0.205; r = 0.067, p = 0.510; r = 0.164, p = 0.104; r = 0.014, p = 0.894; r = 0.138, p = 0.172; r = 0.139, p = 0.169; r = 0.137, p = 0.174; r = 0.192, p = 0.056), hemoglobin (r = 0.103, p = 0.307; r = 0.101, p = 0.320; r = 0.119, p = 0.237; r = 0.164, p = 0.102; r = 0.073, p = 0.473; r = 0.163, p = 0.106; r = 0.016, p = 0.877; r = 0.095, p = 0.349) and LDL-C (r = 0.232, p = 0.406; r = 0.247, p = 0.277; r = 0.257, p = 0.430; r = 0.091, p = 0.366; r = 0.076, p = 0.451; r = 0.133, p = 0.188; r = 0.243, p = 0.108; r = 0.160, p = 0.077).

In the fully adjusted multivariable regression analysis, a one-unit decrease in muscle mass change was associated with an increase of 0.503, 0.382, 0.241, 0.174, and 0.163 mm in the L1-L5 diameter respectively, a increase of 0.020 in aortic tortuosity, a increase of 0.017 in DTA tortuosity, and a increase of 0.016 in AA tortuosity. Detailed results of the regression analysis are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

Cancer survivors are at increased risk of CVD as well as death from CVD20. Aortic morphology has been found to be the predictor of CVD events21. Additionally, previous research has shown that low muscle mass is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular related mortality22. However, the data available were limited, mainly pertained to aortic diameter, and suggested an association of aortic diameter with influencing factors23. The evidence on tortuosity in cancer remains limited. The relationship between long-term changes in aortic morphology and those in muscle mass in cancer remains unknown. For the first time, we conducted a 1-year longitudinal study on cancer patients, which revealed a negative correlation between changes in muscle mass and morphological remodeling of the aorta, including dilation and tortuosity. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of the morphological features of various segments of the aorta and muscle mass, thereby providing novel imaging biomarkers for assessing cardiovascular risk in cancer patients.

Through longitudinal study, we found that the diameter and tortuosity of the aorta increased over one year in cancer patients. These morphological changes are associated with the aging process and progressive arterial stiffness. Imaging confirmed that the aorta in cancer patients underwent significant adverse remodeling within a year following diagnosis and treatment. Importantly, this phenomenon may be associated with the increased incidence of CVD and poor cardiovascular prognosis in cancer patients24. Concurrently, we observed a significant decrease in muscle mass among cancer patients over one year, indicating that these patients are at a higher nutritional risk and more prone to muscle loss25. Cancer patients have a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular complications, which has an important impact on the overall prognosis of patients. In the context of cardiovascular risk assessment, recent studies have highlighted two key dimensions. First, traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as hypertension, diabetes and obesity, are also applicable in cancer patients, and these factors are closely related to cardiovascular complications related to cancer treatment26. Second, emerging evidence suggests that cancer treatments themselves may induce cardiovascular toxicity. For instance, the CARDIOTOX registry study demonstrated that pre-treatment cardiovascular risk evaluation using the SCORE system effectively predicts severe cardiotoxicity and all-cause mortality during cancer treatment, primarily through traditional risk factor profiling27. In our study, we identified a negative correlation between changes in muscle mass and alterations in aortic morphology. Even after controlling for confounding variables, higher muscle mass was significantly associated with reduced aortic diameter and tortuosity. These findings indicate that muscle loss is associated with inadequate morphological remodeling of the aorta. Furthermore, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that long-term physical activity can reduce CVD risk in cancer survivors28. This suggested that muscle mass may serve as a potential cardiovascular risk factor for future interventions in cancer patients. Such implications may extend across age groups. While comprehensive geriatric assessments (incorporating frailty, nutrition, and cognitive evaluations) have proven effective for cardiovascular risk identification in elderly cancer patients (> 70 years)29. Our study focused on middle-aged to older adults (40–70 years), and this demonstrated that muscle mass preservation remains a critical concern independent of chronological age.

Contrast-enhanced CT is the primary modality utilized for evaluating tumor grade and patient prognoses, particularly in distinguishing changes following cancer treatment. In this study, we utilized contrast-enhanced CT data from the chest and abdomen to comprehensively assess the diameter and tortuosity of various segments of the aorta, evaluate skeletal muscle mass, and investigate the relationship between muscle mass and aortic morphological remodeling. This approach offers a novel method for assessing cardiovascular risk without necessitating additional procedures for patients. Furthermore, our segmental analysis revealed a stronger association between the changes in the diameter of proximal aortic segments and muscle mass. Additionally, compared with the changes in thoracic aorta tortuosity, the changes in abdominal aorta tortuosity showed a weaker association with muscle mass changes. The preferential influence of muscle mass on the proximal segment of the aorta may be related to the structure of the aorta. Segmental changes exist in the structure, composition, and hemo- dynamics of the aorta30,31. Significant differences were found in morphometry and composition among different segments of the aorta, with the collagen and elastin contents, respectively, being higher distally and proximally32. Patients with cancer are markedly insulin resistant33. Insulin resistance would result in a decrease in elastin fibers, reducing the stretch and flexibility of the aorta and leading to changes in aortic tortuosity and dilatation34.

A previous study showed that HDL-C, diastolic pressure, and systolic pressure were associated with aortic diameter23. However, our current study indicated a link between aortic diameter and tortuosity and HDL-C, diastolic pressure, and CRP in some aortic segments. High HDL-C levels are positively correlated with a decreased cancer risk35. It is also generally accepted that HDL-C has many protective effects on the cardiovascular system. Hence, the improvement in HDL-C levels is good for cardiovascular health in cancer patients. A large prospective cohort study showed that hypertension was related to increased risks of cancer and mortality36. Our data indicated a positive correlation of diastolic pressure with the diameters of the aortic segments L1-L4. Surprisingly, systolic pressure was not related to morphological features. Excessive secretion of renin, angiotensin, and angiotensin I by carcinoma cells may lead to paraneoplastic hypertension21. Hypertension might result in the dysfunction of endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscles, further inducing morphological and physiological changes in the arterial wall37. We also found CRP was positively associated with aortic morphology. Previous reports have shown that inflammation plays a crucial role in tumorigenesis and vascular structure38. The soft inner elastic membrane degrades, and the tunica intima thickens owing to increased protein deposition in the basement membrane39. Additionally, increased collagen fiber deposition decreases the flexibility of the aorta, which ultimately results in aortic morphology changes39. Although we did not explore the relationship between aortic morphology and categorical variables, such as sex, these variables did not change during the follow-up period. However, sex differences in aortic morphology exist23. To eliminate the effect of sex on the relationship between aortic morphology and muscle mass, we adjusted for these factors as confounding factors. To explore the effect of categorical variables on aortic morphology, subgroup analysis is required.

After a 1-year longitudinal follow-up, we observed decreased muscle mass and increased aortic diameter and tortuosity in patients with cancer. The underlying mechanisms of this phenomenon may involve inflammation, endocrine and other factors. Previous research has indicated that cancer survivors may face a higher burden of low muscle mass40. Skeletal muscle is the main organ responsible for glycogen storage and glucose uptake, which play central roles in metabolic homeostasis41. Low muscle mass is related to an increased risk for the development of type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance42. However, improved skeletal muscle strength and physical activity are cornerstones in the prevention, treatment, and management of metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hepatic steatosis43. Furthermore, proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1, and interleukin-6, secreted from tumors may cause appetite loss and contribute to the degradation of myofibrillar proteins and reduced protein synthesis, eventually resulting in muscle wasting44,45. Inflammatory states in cancer might prevent iron absorption by the gut and promote iron retention by macophages46. The resulting iron deficiency triggers anemia, which might affect skeletal muscle oxygenation and cardiac function47. Inflammation may lead to endothelial cell dysfunction and thus cause abnormal vasodilation and vasocontriction39. Our study also indicated that CRP was positively associated with aortic morphological characteristics, which suggests that inflammation might play an important role in aortic morphology. Moreover, recent studies suggested that the skeletal muscle is an endocrine organ and secretes a vast majority of myokines48. Some myokines such as fibroblast growth factor 21, musclin, and apelin have a salutary effect on the cardiovascular system, which is related to protection against atherosclerosis and blood pressure control. Hence, skeletal muscle atrophy may lead to impaired cardiovascular protection function48. Further, the “muscle pump” effect is crucial in regulating blood flow during exercise49. During muscle contraction, peripheral venous blood is expelled, thus promoting venous return and increasing cardiac output and stroke volume49. Low muscle mass will change the “muscle pump” effect, affect returned blood volume and aortic afterload, alter hemodynamics, and finally change the aortic morphology. Overall, we hypothesize that the specific characteristics of cancer, in conjunction with muscle loss, may adversely affect vascular morphology, thereby creating a vicious cycle involving cancer, muscle, and the aorta.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center study. Multicenter studies with larger sample sizes were needed to verify our findings. Second, we did not evaluate skeletal muscle function, which might have potentially affected the relationships described herein. In addition, information regarding medication use and smoking habits is worth considering; however, unfortunately, we could not obtain these data. This limitation might have limited us from fully assessing the confounding factors in the correlation between muscle mass and the geometry of the aorta. Finally, different tumor types were included in this study, which may have affected the results to some extent. In the future, we would include patients with a specific tumor type to validate our results.

Conclusions

Our study revealed the relationship between muscle loss and aortic regional morphological changes in cancer, highlighting that muscle loss is a key factor in increased cardiovascular risk. This study advanced the understanding of the mechanisms of cancer-cardiovascular comorbidity and promoted the development of comprehensive interventions for cancer patients. Muscle might be an important therapeutic target, with strategies such as nutritional support and physical therapy offering potential to improve cancer patients’ prognosis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

de Boer, R. A., Meijers, W. C., van der Meer, P. & van Veldhuisen, D. J. Cancer and heart disease: associations and relations. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 21, 1515–1525 (2019).

Rugbjerg, K. et al. Cardiovascular disease in survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: a Danish cohort study, 1943–2009. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106, dju110 (2014).

Paterson, D. I. et al. Incident cardiovascular disease among adults with cancer: A Population-Based cohort study. JACC CardioOncology. 4, 85–94 (2022).

Merollini, K. M. D., Gordon, L. G., Ho, Y. M., Aitken, J. F. & Kimlin, M. G. Cancer survivors’ Long-Term health service costs in queensland, australia: results of a Population-Level data linkage study (Cos-Q). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 9473 (2022).

Al-Jumaily, A. M. et al. Computational modeling approach to profile hemodynamical behavior in a healthy aorta. Bioeng. (Basel). 11, 914 (2024).

Zolfaghari, H., Andiapen, M., Baumbach, A., Mathur, A. & Kerswell, R. R. Wall shear stress and pressure patterns in aortic stenosis patients with and without aortic dilation captured by high-performance image-based computational fluid dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011479 (2023).

Totoń-Żurańska, J., Mikolajczyk, T. P., Saju, B. & Guzik, T. J. Vascular remodelling in cardiovascular diseases: hypertension, oxidation, and inflammation. Clin. Sci. (London). 138, 817–850 (2024).

Rasouli, R. et al. Local arterial stiffness measured by ultrafast ultrasound imaging in childhood cancer survivors treated with anthracyclines. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1150214 (2023).

Wilcox, N. S. et al. Cardiovascular disease and cancer: shared risk factors and mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 617–631 (2024).

Grønberg, B. H., Valan, C. D., Halvorsen, T., Sjøblom, B. & Jordhøy, M. S. Associations between severe co-morbidity and muscle measures in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 10, 1347–1355 (2019).

de Jong, C. et al. The association between skeletal muscle measures and chemotherapy-induced toxicity in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 13, 1554–1564 (2022).

Cameron, M. E. et al. Low muscle mass and radiodensity associate with impaired pulmonary function and respiratory complications in patients with esophageal Cancer. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 236, 677–684 (2023).

Pierobon, E. S. et al. The prognostic value of low muscle mass in pancreatic Cancer patients: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 10, 3033 (2021).

Ko, B. J. et al. Relationship between low relative muscle mass and coronary artery calcification in healthy adults. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 36, 1016–1021 (2016).

Xia, M. F. et al. Sarcopenia, sarcopenic overweight/obesity and risk of cardiovascular disease and cardiac arrhythmia: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Nutr. 40, 571–580 (2021).

Nomura, K. et al. Association between low muscle mass and metabolic syndrome in elderly Japanese women. PLoS One. 15, e0243242 (2020).

Jian, Z. et al. Relationship between low relative muscle mass and aortic regional morphological changes in adults underwent contrast CT scans for cancer diagnostics. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 28, 100167 (2024).

Hickson, S. S. et al. The relationship of age with regional aortic stiffness and diameter. JJACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 3, 1247–1255 (2010).

Du Bois, D. & Du Bois, E. F. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Nutrition 5, 303–311 (1916). discussion 12–13 (1989).

Knisely, J. P. S., Henry, S. A., Saba, S. G. & Puckett, L. L. Cancer and cardiovascular disease. Lancet 395, 1904 (2020).

Vasan, R. S., Song, R. J., Xanthakis, V. & Mitchell, G. F. Aortic root diameter and arterial stiffness: conjoint relations to the incidence of cardiovascular disease in the Framingham heart study. Hypertension 78, 1278–1286 (2021).

Han, P. et al. The predictive value of sarcopenia and its individual criteria for cardiovascular and All-Cause mortality in Suburb-dwelling older Chinese. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 24, 765–771 (2020).

Chen, T. et al. Potential influencing factors of aortic diameter at specific segments in population with cardiovascular risk. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 22, 32 (2022).

Wernhart, S. & Rassaf, T. Exercise, cancer, and the cardiovascular system: clinical effects and mechanistic insights. Basic. Res. Cardiol. 120, 35–55 (2025).

Tian, C., Li, N., Gao, Y. & Yan, Y. The influencing factors of tumor-related sarcopenia: a scoping review. BMC cancer. 25, 426 (2025).

Johnson, C. B., Davis, M. K., Law, A. & Sulpher, J. Shared risk factors for cardiovascular disease and cancer: implications for preventive health and clinical care in oncology patients. Can. J. Cardiol. 32, 900–907 (2016).

Caro-Codón, J. et al. Cardiovascular risk factors during cancer treatment. Prevalence and prognostic relevance: insights from the CARDIOTOX registry. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 29, 859–868 (2022).

Rueegg, C. S. et al. Effect of a 1-year physical activity intervention on cardiovascular health in long-term childhood cancer survivors-a randomised controlled trial (SURfit). Br. J. Cancer. 129, 1284–1297 (2023).

Aaldriks, A. A. et al. Prognostic factors for the feasibility of chemotherapy and the geriatric prognostic index (GPI) as risk profile for mortality before chemotherapy in the elderly. Acta Oncol. 55, 15–23 (2016).

Wang, R., Mattson, J. M. & Zhang, Y. Effect of aging on the biaxial mechanical behavior of human descending thoracic aorta: experiments and constitutive modeling considering collagen crosslinking. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 140, 105705 (2023).

Schaafs, L. A. et al. Quantification of aortic stiffness by ultrasound Time-Harmonic elastography: the effect of intravascular pressure on elasticity measures in a Porcine model. Invest. Radiol. 55, 174–180 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. A study to characterize the mechanical properties and material constitution of adult descending thoracic aorta based on uniaxial tensile test and digital image correlation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1178199 (2023).

Màrmol, J. M. et al. Insulin resistance in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 62, 364–371 (2023).

Deane, C. S., Cox, J. & Atherton, P. J. Critical variables regulating age-related anabolic responses to protein nutrition in skeletal muscle. Front. Nutr. 11, 1419229 (2024).

Patel, K. K. & Kashfi, K. Lipoproteins and cancer: the role of HDL-C, LDL-C, and cholesterol-lowering drugs. Biochem. Pharmacol. 196, 114654 (2022).

Harding, J. L. et al. Hypertension, antihypertensive treatment and cancer incidence and mortality: a pooled collaborative analysis of 12 Australian and new Zealand cohorts. J. Hypertens. 34, 149–155 (2016).

Martinez-Quinones, P. et al. Hypertension induced morphological and physiological changes in cells of the arterial wall. Am. J. Hypertens. 31, 1067–1078 (2018).

Soehnlein, O. & Libby, P. Targeting inflammation in atherosclerosis - from experimental insights to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 589–610 (2021).

Hooglugt, A., Klatt, O. & Huveneers, S. Vascular stiffening and endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 33, 353–363 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. Low muscle mass is associated with a higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality in cancer survivors. Nutrition 107, 111934 (2023).

Neoh, G. K. S. et al. Glycogen metabolism and structure: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 346, 122631 (2024).

Consitt, L. A., Dudley, C. & Saxena, G. Impact of endurance and resistance training on skeletal muscle glucose metabolism in older adults. Nutrients 11, 2636 (2019).

Egan, B. & Sharples, A. P. Molecular responses to acute exercise and their relevance for adaptations in skeletal muscle to exercise training. Physiol. Rev. 103, 2057–2170 (2023).

Rausch, V., Sala, V., Penna, F., Porporato, P. E. & Ghigo, A. Understanding the common mechanisms of heart and skeletal muscle wasting in cancer cachexia. Oncogenesis 10, 1 (2021).

Kim, D., Lee, J., Park, R., Oh, C. M. & Moon, S. Association of low muscle mass and obesity with increased all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in US adults. Physiol. Rev. 103, 2057–2170 (2023).

Camaschella, C., Nai, A. & Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the Hepcidin era. Haematologica 105, 260–272 (2020).

Chung, Y. J. et al. Iron-deficiency anemia reduces cardiac contraction by downregulating RyR2 channels and suppressing SERCA pump activity. JCI Insight. 4, e125618 (2019).

Gomarasca, M., Banfi, G., Lombardi, G. & Myokines The endocrine coupling of skeletal muscle and bone. Adv. Clin. Chem. 94, 155–218 (2020).

Hogan, M. C., Grassi, B., Samaja, M., Stary, C. M. & Gladden, L. B. Effect of contraction frequency on the contractile and noncontractile phases of muscle venous blood flow. J. Appl. Physiol. 95, 1139–1144 (2003).

Acknowledgements

L.G. and W.J.L. contributed equally to this work. We thank the Biobank of First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University for their support of this study. All authors performed data collection, analyzed the data, and wrote or reviewed the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82370461), National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (No. 82425004), the Institutional Foundation of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China (No. 2021ZYTS-01,2021ZYT S-04), the Foundation of Key Research and Development Plan of Shaanxi Province of China (2023-YBSF-403), and the Clinical Research Award of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China (No. XJTU1AF-CRF- 2023-011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the research were made by LG, WJL, YW and JZJ; data collection was handled by LG, ZXM, LKM, YG and TYZ; data analysis and/or interpretation the data for the study was made by JZ, WJL and LLC; drafting and revising of the study was made by LG, YW and JZJ. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, L., Liu, W., Meng, Z. et al. One-year longitudinal association between changes in aortic regional morphology and muscle mass in cancer. Sci Rep 15, 22130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06189-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06189-1