Abstract

Aspartame, a widely used artificial sweetener, has been extensively studied for its potential health effects. Emerging evidence suggests that aspartame intake may directly impact the composition and function of the intestinal microbiota, which could subsequently influence the risk, progression, and treatment of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) within the tumor microenvironment. However, it remains unclear whether aspartame intake affects intestinal flora, gene expression, and epigenetic regulation during tumor progression. To address these gaps in knowledge, we conducted a comprehensive metagenomics and transcriptomics analysis of aspartame’s impact on gut microbiota and glioblastoma progression in a mouse model. Using a well-established mouse model and a rigorous metagenomics and transcriptomics approach, our results demonstrated that although the aspartame diet did not significantly affect tumor growth, it induced changes in the composition of the gut microbiota, particularly a decrease in the relative abundance of the Rikenellaceae family. Additionally, key N6-methyladenosine (m6A)-regulated genes, such as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A), MYC (myelocytomatosis) oncogene, and transforming growth factor-β (TGFB1), were significantly upregulated in GBM tumors exposed to aspartame. Notably, the expression of TGFB1 (transforming growth factor-β) suggested a critical role in the progression of GBM mediated by aspartame-induced m6A modifications. Our integrative analysis offered novel perspectives on the intricate interplay between dietary aspartame intake, gut microbiota, and tumor biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Aspartame, an artificial sweetener discovered in 1965, has been widely used in the food and beverage industry since the 1980s due to its intense sweetness and low caloric content1,2. It is commonly found in low-sugar drinks, chewing gum, and certain medications like cough syrups and chewable vitamins3. Despite its widespread use, the safety and health risks of aspartame have been the subject of ongoing debate. Recently, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the Joint FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)/WHO (World Health Organization) Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) have jointly released the latest report on the safety and health risks of aspartame4,5,6. The IARC classified aspartame as a substance possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B) based on limited evidence7,8,9,10. However, JECFA confirmed the previously set Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) of 0–40 mg per kilogram of body weight. The WHO stated that while current evidence suggests aspartame is safe at typical consumption levels, potential effects need further investigation through comprehensive studies.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive and lethal type of primary brain tumor, characterized by its rapid growth, resistance to conventional therapies, and a highly immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment11,12. Although a detailed analysis found no significant link between high aspartame intake (≥ 600 mg/day) from diet beverages and the risk of hematologic cancers or gliomas, recent studies have suggested that aspartame intake might directly influence the composition and function of the intestinal microbiota13,14,15. The gut-brain axis, which enables two-way communication between the gut and the brain, was suggested as a way the gut microbiota could affect glioblastoma16,17. Gut microbiota may influence the risk, the progression and the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme by involving in immunity and metabolism in the GBM microenvironment16,17,18,19,20. For example, the main metabolites of the gut microbiota are short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate21 and the non-SCFAs such as tryptophan (Trp), which can activate cellular receptors and affect cellular metabolism22,23. Vice versa, tumor microenvironment could also affects the gut flora24. For a long time, intratumoural microbiota, once overlooked, are now recognized as key players in tumor development by influencing genomic stability, immune evasion, and metabolism. As research advances, targeting these microbiota holds promise for early cancer diagnosis, prognosis assessment, and novel antitumor therapies, particularly in immunotherapy25. One of the important findings in GBM was that intratumoral bacterial DNA has been identified26. All these highlighted the intricate and potentially significant interplay among aspartame consumption, gut microbial balance, and glioma pathogenesis. However, it remains unclear whether aspartame intake influences gene expression and epigenetic regulation during tumor progression by altering the gut microbiota. Thus, we here aim to test the hypothesis that aspartame intake modulates microbiota changes, thereby inducing alterations in gene expression and regulation during tumorigenesis.

Epigenetic modifications, particularly N6-methyladenosine (m6A) in mRNA, have emerged as critical regulators of gene expression and cellular processes27. The m6A modification is also closely linked with organismal metabolism and the intestinal microbiota28,29,30, suggesting a potential connection between aspartame-induced changes in gut microbiota and glioma progression through epigenetic regulation. In this research, we employed metagenomic sequencing, transcriptomic sequencing, and m6A sequencing to investigate how aspartame influence gut bacteria, glioma progression and gene expression. This study aims to provide new insights into the potential effects of aspartame on glioblastoma and the underlying biological processes.

Materials and methods

Lentiviral construction

The lentiviral vectors used to induce gliomas in mice contain two key components: (1) HrasG12V: Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (HRAS) with a glycine-to-valine mutation at codon 12, which is an activating oncogenic mutation frequently observed in cancer studies, and (2) shp53: short hairpin RNA targeting the tumor suppressor gene TP53 (also known as p53), commonly used to knock down p53 expression in experimental models. These vectors promote HrasG12V and luciferase expression through an internal ribosome entry site (IRES), as we reported previously27,31. The lentiviral vector was cotransfected into human embryonic kidney 293 T cells along with the packaging plasmids pCMVA8.9 and pMD2.G31. The supernatant containing the lentiviral particles was then collected and subjected to centrifugation at 130,000 × g for 2.5 h at 4 °C. The lentiviral particles were subsequently resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and quantified via quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

Construction and care of the mouse model of glioblastoma

The ten 7–8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice used for the experiments were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All the mice were intracranial xenograft tumor models. After being infected with lentiviruses carrying GFP, HrasG12V, or sh-p53 for 7 days, the animals were housed in the SPF-level animal facility at the Animal Center of Guangxi Medical University. The light cycle was 14:10, with the environmental temperature maintained between 20–27 °C and the relative humidity between 40–70%. The mice were randomly assigned to the experimental group (aspartame diet) or the control group (normal diet), with n = 5 mice per group, and housed together. All animal experiments were conducted in strict accordance with the animal protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University.

Aspartame diet experiment and sampling

The experimental group of mice were given drinking water containing a prepared solution of aspartame (50 mg/kg), whereas the control group was given normal water continuously for 15 days under otherwise identical conditions. For in vivo fluorescence imaging, the substrate D-luciferin potassium salt was injected intraperitoneally into the mice to study its biodistribution and tumor-targeting ability. The fluorescence imaging data were processed via the PerKinElmer IVIS Lumina XRMS imaging system and collected upon observing protruding tumor masses in the head. The signal was collected from defined regions of interest (ROIs) via the isopleth ROI tool, and the total photon flux intensity (photons/second) was analyzed via Living Image. Differences in bioluminescent signals between groups were compared via independent samples t tests. At the end of the experiment, the mice were using physical methods in compliance with animal ethics regulations, and their heads were dissected to collect brain and tumor samples, which were then rapidly frozen and used for MeRIP-Seq. Fecal samples from each group of mice were collected simultaneously for subsequent sequencing.

Metagenomic sequencing and analysis

To avoid any potential batch effects during DNA isolation and sequencing, experimental and control samples were mixed prior to shipping them for processing. The frozen fecal samples were transported from Drikold to Novogene Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The isolation of DNA from the fecal samples was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols, and the quantity of DNA was subsequently determined via a Qubit. Qualified DNA samples were randomly fragmented into approximately 350 bp segments via a Covaris ultrasonicator. The entire library preparation process then involved steps such as end repair, A-tailing, addition of sequencing adapters, purification, and PCR amplification. Finally, the libraries were sequenced on an Illumina PE150 instrument.

The raw data were filtered according to the following criteria: reads containing a high proportion of low-quality bases (quality value < = 38) exceeding a certain threshold (40 bp) were removed, reads containing a high proportion of N bases (10 bp) were removed, and finally, reads with adapter overlaps exceeding a specified threshold (15 bp) were removed. The generated clean data were assembled via MEGAHIT software28. The assembled scaffolds were broken at N connections to obtain scaffold sequences without N bases. For scaffolds generated from single-sample assemblies, fragments shorter than 500 bp were filtered out, followed by statistical analysis and subsequent gene prediction32,33.

RNA-Seq and m6A peak calling

We used HISAT2 (v2.1.0)34 to align the filtered reads to the mm10 reference genome. The resulting BAM files from the alignment were used as input for read quantification. We used StringTie (v1.3.4)35 to calculate counts for Ensembl-annotated genes as we reported previously36.

We used ExomePeak237 to detect RNA methylation sites and identify differential RNA methylation sites between the experimental and control groups. Genes (concatenated exons) were initially divided into continuous bins of 50 bp, where read counts from input and immunoprecipitation samples were quantified. Next, we applied a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test to identify bins significantly enriched in the immunoprecipitant samples compared with the input samples. Specifically, we constructed a contingency table that included read counts of a bin in input (a) and IP (b) samples, as well as median read counts of bins within genes containing the bin in input (c) and IP (d) samples. The odds ratio (OR) was calculated as (b × c)/(d × a) to assess enrichment. For each gene, we performed an FDR control procedure and used a cutoff of FDR < 5% to call a peak bin for each sample33,38.

To gain insight into m6A methylation patterns, we utilized Homer239 to detect known motifs and predict potential novel motifs. This analysis was conducted under default parameters to ensure consistency and reproducibility. The distribution of m6A peaks across transcripts was visualized via Guitar (v.2.18.0)40. To determine the regions overlapping by at least one nucleotide between aspartame-induced peaks and normal peaks, we used bedtools (v2.29.2)27 to analyze peak bed files with default parameters (bedtools intersect -a APM_peaks.bed -b Control_peaks.bed -wa > overlap.bed). We visualized the results via ggvenn (v0.1.10)39. The BigWig files were loaded into the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (v2.17.4)41 to visualize the peaks.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes

The gene expression profile was derived from RNA-Seq data. The read counts for each gene, determined by HTSeq42, were analyzed for differential expression via DESeq2 v3.1.043. Genes with an FDR (false discovery rate) ≤ 0.05 and average CPM (counts per million) > 100 were considered differentially expressed. Among these genes, genes with a log2-fold change (log2FC) ≥ 2 and P < 0.05 were defined as upregulated, whereas genes with a log2FC ≤ -2 and P < 0.05 were defined as downregulated in gene expression, as we reported previously44. CGGA and GEPIA245 were used for gene expression analysis and survival analysis.

GO functional enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis

To investigate the potentially different mechanisms between the aspartame and normal diet groups, the DEGs identified in the previous step were subjected to a series of enrichment analyses, including those of biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), cellular component (CC), and gene ontology (GO) annotations and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html). These analyses were conducted via the Benjamini‒Hochberg (BH) method. Ontology (GO) annotation and enrichment analysis were performed via Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, and false discovery rate (FDR) values were obtained via the Benjamini‒Hochberg (BH) method, with FDR ≤ 0.05 as the threshold. Entries in the GO/Pathway database that satisfied this condition were defined as significantly enriched entries in the differentially expressed genes, as we reported previously39.

Statistical analyses

All the statistical analyses were conducted in R (v4.3.3). Student’s t test was used to compare data between the aspartame diet group and the normal diet group. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The results of the correlation analysis were presented graphically via the ggplot2 (v3.4.4) and pheatmap (v1.0.12) packages, as we reported previously32.

Results

Changes in the gut microbiota of GBM mice induced by an aspartame diet

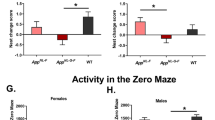

To assess whether the aspartame diet alters the microbial structure in glioblastoma (GBM) mice, we constructed a glioma model by implanting lentivirus-transfected 293 T cells into healthy C57BL/6 mice and controlling their diet (Fig. 1A). Fluorescence imaging comparisons were performed when the mice developed cranial protrusions (Fig. 1B). Taxonomic analysis revealed the top ten genera in terms of the relative abundance of the microbiota at the family level in both groups: Bacteroidaceae, Clostridiaceae, Eggerthellaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Eubacteriaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Muribaculaceae, Oscillospiraceae, Prevotellaceae, and Rikenellaceae (Fig. 1C). Further differential analysis revealed significant differences in the relative abundances of Erysipelotrichaceae, Clostridiaceae, and Rikenellaceae between the two groups (Fig. 1D), with Rikenellaceae notably decreased in the aspartame diet group (Fig. 1E).

(A) Experimental group (aspartame diet) versus the control group (normal diet). (B) Biophotonic imaging of glioma regions. (C) Families in the top ten rankings. (D) Heatmap illustrating the disparity in the relative abundance of each family within the microbial community. (E) The relative abundance of Rikenellaceae families was significantly lower in the aspartame diet group (P < 0.05).

Differential genes and differential methylation

We analyzed total mRNA expression patterns via microarray analysis to study mRNA expression. The analysis revealed that, compared with those in the normal diet group, 6,146 mRNAs were significantly differentially expressed in the aspartame diet group (|log FC|≥ 2, p < 0.05), with 2,730 mRNAs upregulated and 3,416 mRNAs downregulated (Fig. 2A). Additionally, to investigate differences in m6A methylation levels between the two groups, we analyzed immunoprecipitated m6A-methylated RNA. Compared with those in the control samples, there were 6,322 transcripts with differential methylation in the aspartame diet group, including 2,928 transcripts with increased methylation and 3,394 transcripts with decreased methylation (|Log FC|≥ 2, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2B). Hierarchical clustering identified relationships between samples and revealed distinct m6A methylation patterns and mRNA expression patterns between the aspartame diet group and the normal diet group (Figs. 2C & 2D).

Differential analysis of m6A methylation and mRNA expression. (A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between the aspartame diet group and the normal diet group. Genes significantly upregulated are shown in red, genes significantly downregulated in blue, and genes with no significant difference in expression are shown with gray dots. (B) Volcano plot showing differential m6A methylation of transcripts between the two groups. Transcripts with high methylation are shown in red, and those with low methylation are shown in blue. (C) Heatmap illustrating differences in gene expression between the two groups. (D) Heatmap demonstrating different mRNA methylation patterns between the two groups.

Correlation between m6A methylation and mRNA expression

To investigate whether m6A methylation affects mRNA translation, we conducted correlation analyses between the differentially expressed mRNAs and the differentially methylated m6A-mRNAs. We identified four patterns: 1,314 mRNAs with high methylation showing decreased expression, 1,169 mRNAs with high methylation showing increased expression, 1,504 mRNAs with low methylation showing decreased expression, and 1,207 mRNAs with low methylation showing increased expression (Figs. 3A-3D). Additionally, we analyzed the correlations between differentially expressed m6A regulatory factors and transcripts with differential methylation or expression (Fig. 3E).

Correlation analyses between differentially expressed mRNAs and differentially methylated m6A-mRNAs. (A) Downregulation-Hypermethylation; (B) Upregulation-Hypermethylation; (C) Downregulation-Hypomethylation; (D) Upregulation-Hypomethylation; (E) Nine-quadrant plot depicting the correlation between log2-fold changes (log2FC) in differentially expressed transcripts and log2FC in differential m6A methylation between the two groups.

GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes

To explore the potential biological functions and molecular pathways of the 6,146 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), we conducted Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses on these DEGs. GO analysis revealed that the most enriched biological process (BP) terms included gliogenesis, tumor necrosis factor production, neuron apoptotic process, and forebrain development. Cellular component (CC) analysis revealed enrichment in the collagen-containing extracellular matrix and neuron-to-neuron synapses. Molecular function (MF) analysis revealed enrichment in the terms “metal ion transmembrane transporter activity” and “actin binding” (Fig. 4A). Enriched pathways such as the cell cycle, ECM-receptor interaction, DNA replication, the p53 signaling pathway, and the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway were significantly associated with tumor development (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B).

GO enrichment and pathway analysis. (A) GO enrichment of 6,146 differential genes between the two groups; (B) KEGG pathway analysis of 6,146 differential genes between the two groups; (C) KEGG pathway analysis of 1,314 differentially expressed genes in the first quadrant (transcripts upregulated in MeRIP-seq but downregulated in RNA-seq); (D) KEGG pathway analysis of 1,169 differentially expressed genes in the third quadrant (transcripts upregulated in both MeRIP-seq and RNA-seq); (E) KEGG pathway analysis of 1,504 differentially expressed genes in the seventh quadrant (transcripts downregulated in both MeRIP-seq and RNA-seq); (F) KEGG pathway analysis of 1,207 differentially expressed genes in the ninth quadrant (transcripts downregulated in MeRIP-seq but upregulated in RNA-seq) (G). GO enrichment of differentially expressed genes in the ninth quadrant.

Furthermore, we performed GO and KEGG analyses separately for mRNAs whose expression was downregulated under high methylation conditions, upregulated under high methylation conditions, downregulated under low methylation conditions, and upregulated under low methylation conditions (Figs. 4C, 4D & 4E). We focused on mRNAs whose expression was upregulated under low methylation conditions, and the results revealed that these 1,207 genes were enriched mainly in pathways such as the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, pathways in cancer, the p53 signaling pathway, and the cell cycle (Figs. 4F & 4G), which was highly consistent with the aforementioned results.

Analysis of m6A sites and peaks

Comparison of the m6A peaks between the aspartame diet group and the normal diet group revealed similar patterns (Fig. 5A). The m6A peaks were most enriched in the 3’ UTR, followed by the 5’ UTR and coding sequence (CDS) (Fig. 5B), which is consistent with previous reports. The sequences within the peaks are enriched with the “RRACH” motif (R = G or A; H = A, C, or U) (Fig. 5C). We found that the m6A peaks and gene expression levels of the MYC (myelocytomatosis), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (CDKN1A), and transforming growth factor-β (TGFB1) transcripts were greater in the aspartame diet group than in the normal diet group (Fig. 5D-I). These three genes are transcripts whose expression is downregulated according to MeRIP-seq but upregulated according to RNA-seq.

Validation of aspartame-regulated gene expression and its impact on clinical outcomes in TCGA and CGGA

To further analyze the potential impact of aspartame-regulated m6A-modified genes on the progression of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), we examined the differential expression of these genes between GBM patients and healthy controls via GEPIA245 (Fig. 6A). Our findings indicated that CDKN1A, MYC, and TGFB1 were upregulated in GBM tumor tissues. Among these, only the expression of TGFB1 was associated with adverse clinical outcomes according to CGGA46 (Fig. 6B), suggesting that the aspartame-m6A-TGFB1 axis might be a crucial molecular mechanism regulating the progression of GBM.

A: Boxplot showing the expression of CDKN1A, MYC and TGFB1 . CDKN1A (The 95% confidence intervals for gene expression show little overlap (Tumor: 6.16–6.64, Normal: 4.28–4.72), indicating a significant difference. The effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.22) suggests higher expression in the tumor group), MYC, The confidence interval for the tumor group is (4.8, 5.6), while for the normal group, it is (2.3, 3.0). The intervals barely overlap, and Cohen’s d is 1.5, indicating significantly higher MYC expression in GBM. TGFB1 The confidence interval for the tumor group is (5.2, 5.9), while for the normal group, it is (2.6, 3.3). There is no overlap between the intervals, and Cohen’s d is around 1.6, suggesting significantly higher TGFB1 expression in GBM. B: Kaplan‒Meier curve showing survival rates based on the expression levels of CDKN1A, MYC, and TGFB1.

Discussion

Aspartame, as a widely used artificial sweetener, has gained popularity in the food and beverage industry due to its high sweetness and low-calorie properties47. However, concerns about its potential health risks, especially its classification as a possible human carcinogen, have led to a reevaluation of its safety and could negatively affect its market prospects48,49. Researchers have uncovered substantial evidence indicating that aspartame consumption is associated with an elevated risk of various cancers, including those affecting the brain, hematopoietic system, digestive tract, and reproductive organs50,51,52. Additionally, aspartame intake has been linked to the development of liver, lung, cardiovascular, endometrial cancers, and headaches53,54,55,56,57. Additionally, factors such as sex can influence how aspartame affects the body58. Beyond this, food additives like aspartame may contribute to central nervous system disorders such as memory impairment59,60. Currently, exploration of the underlying impact by which aspartame might influence tumor progression remains notably inadequate. Our study, for the first time, investigated the impact of an aspartame diet on the gut microbiota, gene expression, and m6A methylation status in a well-established mouse model.

The composition and abundance of gut microbiota, particularly the Rikenellaceae family, are closely associated with the levels of volatile fatty acids, such as acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid61. Numerous findings have provided compelling evidence of a robust connection between the abundance of the Rikenellaceae family in the gut and a diverse array of metabolic health conditions, including Parkinson’s disease62 and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)63. Our study concluded that although the aspartame diet did not significantly affect tumor growth, it did induce changes in the composition of the gut microbiota, particularly a decrease in the relative abundance of the Rikenellaceae family. We speculated that gut microbiota could influence the progression of glioblastoma multiforme by gut-brain axis.

Additionally, such a diet resulted in significant differences in mRNA expression and m6A methylation levels, suggesting a potential role of m6A methylation in gene regulation. Our further analysis revealed alterations in biological processes and molecular pathways associated with tumor development, such as the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and the cell cycle, both of which have been clinically implicated in the progression of various malignancies64. Specifically, changes in m6A peaks and the expression levels of key genes such as MYC, CDKN1A, and TGFB1 suggested that these genes might be important targets influenced by aspartame. Among the three genes, the MYC oncogene, a pivotal transcription factor, has a diverse range of functions that significantly impact cellular activities such as the cell cycle, the DNA damage response, and hematopoiesis65,66. Related investigations have revealed striking similarities between the modes of action and signaling pathways associated with aspartame-related targets and those associated with established carcinogenic mechanisms67.

Studies have also suggested that aspartame can reduce the transcription of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α), thus activating TP53 through metabolic pathways in tumors and promoting hepatocellular carcinoma68. This study might indicate a correlation between sweeteners such as aspartame and the development of tumors; however, the underlying mechanism and its potential implications remain largely unexplored. From the perspective of m6A, we elucidated how aspartame regulates the host-gut microbiota, leading to differences in glioma epigenetic modifications and sparking research interest in the molecular mechanisms and regulatory pathways relevant to tumors. Currently, there are still divergences in research findings regarding the impact of aspartame on tumor development, with some studies yielding contrasting conclusions. We hypothesized that these discrepancies might result from various factors, including tumor types, sex, dietary patterns, and sample size, all of which could introduce individual variability in studies exploring the interplay between the host and the gut microbiota.

In conclusion, while aspartame intake did not significantly influence tumor growth, it did alter the composition of gut microbiota. Notably, key m6A-regulated genes were significantly upregulated in GBM tumors exposed to aspartame, and the expression of TGFB1 highlighted its potential role in GBM progression mediated by aspartame-induced m6A modifications. Our findings not only provide critical evidence for evaluating the safety of artificial sweeteners but also offer a comprehensive assessment of their impact on tumor progression. These insights open new avenues for GBM treatment strategies, including gene-targeted therapies and microbial-based interventions, among others.

However, we acknowledge certain limitations in our study due to constraints in the number of experimental samples, techniques and knowledge. For example, we did not investigate the potential role of aspartame metabolites—such as phenylalanine, aspartic acid, and methanol—and their impact on GBM progression. These metabolites could significantly influence the tumor microenvironment, and further exploration of their effects may uncover additional mechanisms through which aspartame contributes to GBM development. Moreover, this study did not examine the role of the intratumoral microbiome in mediating aspartame’s effects. Given the growing evidence that the microbiome influences tumor progression and treatment responses, future research incorporating microbiome analysis could provide critical insights into how aspartame interacts with the tumor microenvironment and shapes therapeutic outcomes. Addressing these limitations in subsequent studies will enhance our understanding of aspartame’s broader biological implications.

Our upcoming research will delve into how aspartame-induced alterations in intestinal flora impact metabolism and the tumor microenvironment. Leveraging metabolome sequencing, we aim to unravel the complex regulatory networks driving these changes, alongside characterizing the microbial composition within the tumor microenvironment. To enhance the scope and reliability of our findings, we will expand the study by increasing the sample size and incorporating diverse gender groups. Furthermore, future investigations will include models with IDH mutations to explore whether the presence of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) modulates the effects of aspartame in GBM, providing deeper insights into the metabolic and molecular interplay in tumor progression.

Data availability

The data presented in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive at the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (GSA: CRA017450) and are publicly accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa.

References

Czarnecka, K. et al. Aspartame—true or false? Narrative review of safety analysis of general use in products. Nutrients 13(6), 1957. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061957 (2021).

Butchko, H. H. et al. Aspartame: Review of safety. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 35(2 Pt 2), S1–S93. https://doi.org/10.1006/rtph.2002.1542 (2002).

Magnuson, B. A. et al. Aspartame: A safety evaluation based on current use levels, regulations, and toxicological and epidemiological studies. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 37(8), 629–727. https://doi.org/10.1006/rtph.2002.1542 (2007).

Soffritti, M. et al. Aspartame induces lymphomas and leukaemias in ratsa L’aspartame induce linfomi e leucemie nei ratti. Eur. J. Oncol. 10(2), 107–116 (2005).

Soffritti, M. et al. First experimental demonstration of the multipotential carcinogenic effects of aspartame administered in the feed to Sprague-Dawley rats. Environ. Health Perspect. 114(3), 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8711 (2006).

Soffritti, M. et al. Life-span exposure to low doses of aspartame beginning during prenatal life increases cancer effects in rats. Environ. Health Perspect. 115(9), 1293–1297. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10271 (2007).

Stepien, M. et al. Consumption of soft drinks and juices and risk of liver and biliary tract cancers in a European cohort. Eur. J. Nutr. 55(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-014-0818-5 (2016).

Jones, G. S. et al. Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of liver cancer by diabetes status: A pooled analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 79, 102201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2022.102201 (2022).

McCullough, M. L. et al. Sugar-and artificially-sweetened beverages and cancer mortality in a large US prospective cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarker. Prev. 31(10), 1907–1918. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-22-0392 (2022).

Riboli, E. et al. Carcinogenicity of aspartame, methyleugenol, and isoeugenol. Lancet Oncol. 24(8), 848–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00341-8 (2023).

Tong, M. F. et al. Joint analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing and bulk transcriptome reveals the heterogeneity of the urea cycle of astrocytes in glioblastoma. Neurobiol. Dis. 10, 106835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2025.106835 (2025).

Zhong, R., He, H. M. & Wang, X. D. Novel neutrophil targeting platforms in treating Glioblastoma: Latest evidence and therapeutic approaches. Int. Immunopharmacol. 150, 114173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114173 (2025).

Lim, U. et al. Consumption of aspartame-containing beverages and incidence of hematopoietic and brain malignancies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarker. Prev. 15(9), 1654–1659. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0203 (2006).

Suez, J. et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature 514(7521), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13793 (2014).

Ruiz-Ojeda, F. J. et al. Effects of sweeteners on the gut microbiota: a review of experimental studies and clinical trials. Adv. Nutr. 10(suppl_1), S31–S48. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy037 (2019).

Yan, J. Q., Li, B. & Luo, C. Gut microbiota’s role in glioblastoma risk, with a focus on the mediating role of metabolites. Front. Neurol. 15, 1386885. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1386885 (2024).

Ishaq, H. M. et al. The gut-brain-axis: A positive relationship between gut microbial dysbiosis and glioblastoma brain tumour. Heliyon 10(9), e30494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30494 (2024).

Chen, X., Han, L. H. & Xu, W. Z. Dissecting causal relationships between gut microbiota, blood metabolites, and glioblastoma multiforme: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1403316. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1403316 (2024).

Jiang, H. X. et al. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in glioblastoma patients and potential biomarkers for risk assessment. Microb. Pathog. 195, 106888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2024.106888 (2024).

Zhang, X. H. et al. The immunosuppressive microenvironment and immunotherapy in human glioblastoma. Front. Immunol. 13, 1003651. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1003651 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Association between gut microbiota and glioblastoma: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Genet. 14, 1308263. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1308263 (2024).

Rothhammer, V. et al. Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and central nervous system inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat. Med. 22(6), 586–597. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4106 (2016).

Rothhammer, V. et al. Microglial control of astrocytes in response to microbial metabolites. Nature 557(7707), 724–728. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0119-x (2018).

Zhou, M. N. et al. Short-chain fatty acids reverses gut microbiota dysbiosis-promoted progression of glioblastoma by up-regulating M1 polarization in the tumor microenvironment. Int. Immunopharmacol. 141, 112881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112881 (2024).

Cao, Y. Q. et al. Intratumoural microbiota: A new frontier in cancer development and therapy. Sig. Transduct. Target Ther. 9(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01693-0 (2024).

Dono, A. et al. Glioma and the gut-brain axis: opportunities and future perspectives. Neurooncol. Adv. 4(1), vdac054. https://doi.org/10.1093/noajnl/vdac054 (2022).

An, S. Q. et al. Integrative network analysis identifies cell-specific trans regulators of m6A. Nucleic Acids Res. 48(4), 1715–1729. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz1206 (2020).

Zhang, C. H. et al. Dietary modulation of gut microbiota contributes to alleviation of both genetic and simple obesity in children. EBioMedicine 2(8), 968–984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.07.007 (2015).

Wang, X. Y. et al. Transcriptome-wide reprogramming of N6-methyladenosine modification by the mouse microbiome. Cell Res. 29(2), 167–170. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-018-0127-2 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Investigational microbiological therapy for glioma. Cancers (Basel) 14(23), 5977. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14235977 (2022).

Zhou, X. et al. A new method of identifying glioblastoma subtypes and creation of corresponding animal models. Oncogene 37(35), 4781–4791. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0305-1 (2018).

Bao, Y. et al. GutUDB: A comprehensive multiomics database for intestinal diseases. Imeta 3(3), e195. https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.195 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Identification and analysis of lncRNA, microRNA and mRNA expression profiles and construction of ceRNA network in Talaromyces marneffei-infected THP-1 macrophage. PeerJ 9, e10529. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.10529 (2021).

Kim, D. et al. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37(8), 907–915. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33(3), 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015).

Xiong, Y. et al. Transcriptomic characteristics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in COVID-19 patients. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9(1), 761–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1747363 (2020).

Meng, J. et al. A protocol for RNA methylation differential analysis with MeRIP-Seq data and exomePeak R/Bioconductor package. Methods 69, 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.06.008 (2014).

Zou, R. C. et al. Co-expression analysis and ceRNA network reveal eight novel potential lncRNA biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma. PeerJ 7, e8101. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8101 (2019).

Chu, J. M. et al. Dynamic m6A profiles reveal the role of YTHDC2-TLR2 signaling axis in Talaromyces marneffei infection. J. Med. Virol. 96(2), e29466. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.29466 (2024).

Lin, Y. et al. Pan-cancer Analysis Reveals m6A Variation and Cell-specific Regulatory Network in Different Cancer Types. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 22(4), qzae052. https://doi.org/10.1093/gpbjnl/qzae052 (2024).

Rouse, W. B. et al. Prediction and analysis of functional RNA structures within the integrative genomics viewer. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 4(1), lqab127. https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/lqab127 (2022).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq-a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31(2), 166–169. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638 (2015).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15(12), 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Platten, M. et al. A vaccine targeting mutant IDH1 in newly diagnosed glioma. Nature 592(7854), 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03363-z (2021).

Tang, Z. F. et al. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(W1), W556–W560. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz430 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA): A comprehensive resource with functional genomic data from Chinese glioma patients. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 19(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2020.10.005 (2021).

Xie, J. M. et al. An integrative analysis reveals cancer risk associated with artificial sweeteners. J. Transl. Med. 23(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-06047-0 (2025).

Sharma, H. et al. Sweet or sour? A review of the Aspartame market landscape, carcinogenicity, and its socioeconomic impact. J. Food Sci. Technol. 62(1), 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-024-06077-y (2025).

Soffritti, M. Understanding the link between aspartame and cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 24(9), 793–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2024.2383675 (2024).

Bernardo, W. M. et al. Adverse effects of the consumption of artificial sweeteners-systematic review. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 62(2), 120–122. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.62.02.120 (1992).

Li, H. et al. Association between Consumption of Sweeteners and Endometrial Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Br. J. Nutr. 131(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114523001484 (2023).

Debras, C. et al. Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 19(3), e1003950. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003950 (2022).

Soffritti, M. et al. Aspartame administered in feed, beginning prenatally through life span, induces cancers of the liver and lung in male Swiss mice. Am. J. Ind. Med. 53(12), 1197–1206. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20896 (2010).

Van den Eeden, S. K. et al. Aspartame ingestion and headaches: A randomized crossover trial. Neurology 44(10), 1787–1793. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.44.10.1787 (1994).

Newman, L. C. & Lipton, R. B. Migraine MLT-down: An unusual presentation of migraine in patients with aspartame-triggered headaches. Headache 41(9), 899–901 (2001).

Choudhary, A. K. & Lee, Y. Y. Neurophysiological symptoms and aspartame: What is the connection?. Nutr. Neurosci. 21(5), 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2017.1288340 (2018).

Millichap, J. G. & Yee, M. M. The diet factor in pediatric and adolescent migraine. Pediatr. Neurol. 28(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0887-8994(02)00466-6 (2003).

Schernhammer, E. S. et al. Consumption of artificial sweetener–and sugar-containing soda and risk of lymphoma and leukemia in men and women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 96, 1419–1428. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.030833 (2012).

Fadaei, M. et al. Food additives for the central nervous system, useful or harmful? An evidence-based review. Nutr. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2024.2433257 (2025).

Bai, H. J. et al. Non-nutritive sweetener aspartame disrupts circadian behavior and causes memory impairment in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72(42), 23478–23492. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.4c05394 (2024).

Chen, S. P. et al. Studies on fatty acids and microbiota characterization of the gastrointestinal tract of Tianzhu white yaks. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1508468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1508468 (2025).

Bai, F. S. et al. Association between increased and decreased gut microbiota abundance and Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and subgroup meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 191, 112444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2024.112444 (2024).

Michels, N. et al. Human microbiome and metabolic health: An overview of systematic reviews. Obes Rev. 23(4), e13409. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13409 (2022).

Lim, S. H. et al. PLD1 is a key player in cancer stemness and chemoresistance: Therapeutic targeting of cross-talk between the PI3K/Akt and Wnt/β-catenin pathways. Exp. Mol. Med. 56(7), 1479–1487. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-024-01260-9 (2024).

Ahmadi, S. E. et al. MYC: a multipurpose oncogene with prognostic and therapeutic implications in blood malignancies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 14(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01152-9 (2021).

Lourenco, C. et al. MYC protein interactors in gene transcription and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21(9), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-021-00367-9 (2021).

Chen, D. D. & Hou, X. B. Aspartame carcinogenic potential revealed through network toxicology and molecular docking insights. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 11492. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-62461-w (2024).

Sergi, C. M. MASLD and aspartame: Are new studies in the horizon?. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 10, 1266918. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1266918 (2023).

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Guangxi Major Science and Technology Program (GK-AA22117015-3), Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Sciences Basic Research Project (GNK2021YT117), Guangxi Academy of Agricultural Science and Technology Development Project (GNK2023ZX06), and Guangdong 3D Orthopedics Biomimetic Translational Medicine Engineering Technology Research Center (2019E016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K.M and Y.B. conducted the data analysis and wrote original draft. J.R.Q., X.H.D., and S.Y.L. performed the experiments. S.Q.A. reviewed the manuscript. Y.C. collected materials. G.L.C., X.L.X., and X.J.F. conceptualized, supervised, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Guangxi Medical University (Ethics: 202307007). All methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, K., Bao, Y., Chen, G. et al. Metagenomics and transcriptomics analysis of aspartame’s impact on gut microbiota and glioblastoma progression in a mouse model. Sci Rep 15, 23298 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06193-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06193-5