Abstract

Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs) are rare, highly aggressive skin cancers with poor outcome due to early lymphatic tumor spread and frequent recurrences. MCCs mostly occur in the head and neck and are mainly caused by an infection with the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV). Increasing evidence suggests that Piwil-2 and small non-coding PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) play an important role in solid malignancies and we thought that this might also be the case for MCCs. Therefore, Piwil-2 expression was first evaluated in 27 MCC specimens and correlated with oncological outcome. We found an association with high Piwil-2 expression and advanced tumor stage, MCPyV positivity and poor outcome. Next, we utilized siRNAs for Piwil-2 knock-down in MCC cells. Downregulation of Piwil-2 caused a significant change of 202 different piRNAs and 419 proteins. Interestingly, proteins related to viral driven MCC pathways (TRRAP, BRD8, PRIM2, ORC4) were significantly downregulated. Moreover, there was a moderate cell cycle arrest of cells in the G0/G1-phase, as well as a significant upregulation of SOX-2, a key regulator of Merkel cells. Altogether, Piwil-2 poses a poor prognosticator in MCCs, which is linked to MCC oncogenesis and SOX-2. Further research is needed to better understand underlying mechanisms and to prove their clinical relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

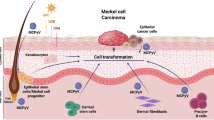

Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs) are highly aggressive neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin with two distinct etiologies1. Up to 80% of MCCs emerge after clonal integration of the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) with subsequent expression of small T (ST) and large T (LT) oncoproteins2. Contrary to virus associated MCCs (MCCP), non-viral MCCs (MCCN) are caused by chronic UV exposure accompanied by high tumor mutational burden3.

Despite an improved understanding of MCC pathogenesis as well as the identification of ATOH1 and SOX-2 as pivotal transcription factors, prognosis is often exceptional poor4,5. Especially, due to frequent metastases to regional lymph nodes and distant organs, MCCs are twice as lethal as melanomas with a 5-year overall survival rate of 51% for local, 35% for nodal involvement, and 14% for metastatic disease3,6,7.

Within the past decades, growing evidence indicates an emerging role of small non-coding RNAs (snRNAs) in tumor biology. It is widely assumed that roughly one third of protein-coding genes are subject of snRNA-mediated control8. Among those, PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) are relatively unknown and less-studied with 24–32 nucleotides in length that were primarily described in germlines for regulating stem cell maintenance9. Those piRNAs exclusively form complexes with proteins of the PIWI family of Argonaute proteins, like Piwil-2, to accomplish their function as epigenetic regulators10,11,12,13,14,15.

During tumorigenic processes, cancer cells may develop “stem cell-like” epigenetic and signaling characteristics. Indeed, a dysregulation of the Piwil-2 / piRNA axis, has been already described in numerous solid malignancies and their therapeutic potential is constantly discussed16,17,18,19. This also sparked our interest in the potential pathogenic and prognostic role of the Piwil-2 / piRNA complex in MCCs.

Therefore, we primarily aimed to evaluate the association of Piwil-2 with clinicopathological parameters and outcome, and secondarily, to assess its pathogenic role through Piwil-2 knock-down experiments with subsequent analyses.

Results

Study cohort

Our cohort comprised 27 MCC cases with a male predominance (15:12) and a median (± SD) age of 77.8 (10.1) years. Most of whom had primary MCC diagnoses (n = 16; 59.3%), which occurred mainly in the head and neck region (n = 17; 63%). Despite absent (Tx) or small primaries (T1/T2) in 93% (n = 25) of patients, lymph node and distant metastases were present in 16 (59.3%) and 6 (22.2%) cases, respectively. Almost half of our cohort was tested positive for MCPyV infection (n = 14; 51.9%; Table 1).

High Piwil-2 expression is associated with worse outcome

A strong, moderate, weak and absent Piwil-2 expression was found in 5 (18.5%), 8 (29.6%), 10 (37.0%), and 4 (14.8%) of the 27 tested specimens, respectively (Fig. 1A). Among them, those with lymph node positive (p = 0.019) or metastatic (p = 0.017) disease and MCPyV positivity (p = 0.006) showed higher Piwil-2 expressions (Table 1).

Moreover, a moderate to strong Piwil-2 expression (high) was associated with a significantly worse disease specific survival (DSS; p = 0.009; Fig. 1B) compared to cases with absent or low expression (low). Comparably, a worse DSS was also found in patients with positive lymph nodes (N+) and metastatic disease (M1); (p = 0.027; p = 0.001; data not shown).

Piwil-2 expression in Merkel cell carcinoma cell lines

Next, we utilized western blotting to evaluate Piwil-2 in cell lysates of five human MCC cell lines (MCC13, MCC26, MKL1, PeTa, WaGa). Characteristic Piwil-2 bands of 130kD, corresponding to full-length protein, were found in all tested cell lines (Fig. 2A).

Effect of Piwil-2 knock-down on piRNAs and protein expression. Piwil-2 expression was detected in five different MCC cell lines (A). Figure A has been modified for the sake of plainness and visualization. Original uncropped gels are provided as supplementary material (Supplementary Fig. 1). PeTa cells were transfected with two siRNAs (siRNA 1 & 2) to knock-down Piwil-2. The total amount of western blot volumes is shown (B). 202 different piRNAs were found of which 11 were significantly dysregulated after transfection (C). Regarding proteomics, 4092 proteins were totally detected in untreated PeTa cells (D) and Piwil-2 knock-down caused an up- and downregulation of 334 (E) and 62 (F) proteins, respectively.

Piwil-2 knock-down by SiRNA

To further assess the potential role of Piwil-2 in MCC tumorigenesis, we evaluated piRNA expression and MCC proteomics depending on Piwil-2 levels. Given the fact that western blot data showed ident Piwil-2 expression in all cell lines, PeTa cells were considered as representative for subsequent analyses. Piwil-2 knock-down experiments were carried out applying two different stealth siRNAs leading to a 35.8% and 61.0% downregulation of Piwil-2 levels after transfection with siRNA1 and siRNA2, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Expressed and altered PiRNAs

Small RNA-sequencing was applied for assessing piRNA expression profiles based on Piwil-2 levels. As previously described20an arbitrary threshold of 10 counts was used as cut-off for piRNA detection. Thereby, 202 piRNAs were found with a mean (± SD) of 640 (± 2246,6) counts in untreated PeTa cells. The 20 highest expressed piRNAs as well as their known physiological and/or oncological function are summarized in Table 2. Among those 202 identified piRNAs, 26 piRNAs were at least 2-fold upregulated and 17 piRNAs downregulated by less than half after transfection with one siRNA. Of note, only 7 of 26 and 4 of 17 piRNAs were up – or downregulated in both siRNA knock-downs (Table 3; Fig. 2C). The entire list of expressed piRNAs is provided as supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1).

Proteomics and pathway enrichment analysis

Altogether, 4092 different proteins were detected and knock-down caused a significant dysregulation (FDR < 0.01) of 419 proteins (Fig. 2D). In particular, 334 proteins were up – and 62 – downregulated in both knock-downs (Fig. 2E,F), while 23 proteins were either down or upregulated.

Gene Ontology (GO) slim biology process analysis (https://pantherdb.org) revealed that downregulated proteins were significantly involved to DNA-replication and RNA metabolic processes, while upregulated proteins were significantly associated to intracellular cell-substrate junction assembly, mitochondrial electron transport, protein transport or translation for instance (Fig. 3A).

Functional analysis. The PANTHER online database was utilized to assess the functional involvement of dysregulated proteins among Gene Ontology (GO) slim biology processes. The ten most altered pathways are indicated for upregulated proteins as well as the two for downregulated proteins (A). String analysis among the 62 downregulated proteins identified six functional clusters of which Cluster 1 with TRRAP and BRD8 and Cluster 2 with ORC4 and PRIM2 deemed most relevant (B).

Cluster analyses, EP400 complex & E2F transcription factors

Based on these results, we hypothesized that particularly downregulated proteins are most likely linked to the pathogenic function of Piwil-2 in MCCs. Therefore, we used the free available string database (https://string-db.org/) to launch a cluster analysis of the 62 significantly downregulated proteins. As shown in Fig. 3B, six clusters have been identified of which Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 are of paramount relevance.

Interestingly, the proteins TRRAP and BRD8 of Cluster 1 are members of the EP400 chromatin remodeling complex, which forms a complex with the MYC paralog MYCL, its heterodimeric partner MAX and MCPyV ST1,21. This complex further activates downstream targets, such as MDM2 that specifically downregulates p53 in MCCP1,21.

With regards to Cluster 2, ORC4 and PRIM2 are linked to the E2F mediated regulation of DNA replication. E2F transcription factors bind and activate the promoters of genes required for G1/S transition and therefore DNA replication. RB can inhibit cell progression by binding and repressing E2F transcriptions factors22,23.

Apoptosis and cell cycle control by Piwil-2

According to these results, we expected significant effects of Piwil-2 knock-down on apoptosis and / or cell cycle control. However, cleaved caspase 3 levels, as apoptosis marker, were unchanged by Piwil-2 knock out (Fig. 4A). Contrary, we detected effects on cell cycle progression. In comparison to untreated cells (61.6%), there was an increase of cells in the G0/G1-phase (61.6% vs. 69.5% in siRNA1, and 61.6% vs. 64.5% in siRNA2) accompanied by a decrease of cells in the S-phase (8.26% vs. 5.56% in siRNA1 and 8.26% vs.6.59% in siRNA2). The number of cells in the G2/M-phase was also decreased (19% vs. 14.9% in siRNA1 and 19% vs. 15.% in siRNA2), suggesting a moderate cell cycle arrest of cells in the G0/G1-phase (Fig. 4B) after Piwil-2 knock-down.

Cell cycle control by Piwil-2. Knock-down of Piwil-2 showed only limited effects on apoptosis (A). Figure has been modified for the sake of plainness and visualization. Original gels are shown as supplementary material (Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, cell-cycle experiments demonstrated a 0.16 to 0.33 and 0.17 to 0.22-fold decrease of cells in the S - and the G2/M – phase, respectively (B). In comparison, a SOX-2 knock-down caused a 0.46 to 0.61-fold decline of cells in the S-phase (C).

Interaction of Piwil-2 and SOX-2

Surprisingly, knock-down of Piwil-2 led also to a 4.26 and 2.98-fold increase of SOX-2, a well-known pivotal transcription factor for MCC development4,24. We hypothesize that the increase of SOX-2 caused, at least partially, the insignificant effects of Piwil-2 knock-down on apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. As shown in Fig. 4C, knock-down of SOX-2 significantly induced cell-cycle arrest in our MCC cell line. In particular, we noticed an incline of cells in the G0/G1-phase (61.6% vs. 70.0% in siRNA1, and 61.6% vs. 75.8% in siRNA2), a lower percentage of cells in the S-phase (8.26% vs. 3.22% and 4.48%, respectively) as well as in the G2/M-phase (19% vs. 15.9% and 11%, respectively).

Discussion

A high Piwil-2 expression was found in advanced tumor stages with regional and / or distant metastasis and MCPyV infection, which, altogether, resulted in worse disease-specific survival. There exists controversial data about MCPyV positivity as poor prognosticator25,26while Piwil-2 as an adverse factor for outcome has been already described in numerous studies and meta-analyses27,28,29,30,31,32.

However, there exist also conflicting data showing opposing effects16,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Even among same tumor entities, like breast28,33 or bladder16,31 cancer, data have shown both beneficial and adverse effects of high Piwil-2 expression. These divergent data illustrate that the Piwil-2/piRNA complex may affect multiple pathways in malignancies.

To begin with, we initially identified Piwil-2 in all five tested MCC cell lines, which suggests a general function of Piwil-2 in MCCs. Knock out experiments revealed significant changes of piRNAs and proteomics depending on Piwil-2 levels. So far, more than 20.000 piRNA genes have been identified in the human genome36 and 202 were detected in our MCC cells as well. Among them, 43 were significantly dysregulated after Piwil-2 knock-down. Given the variety of piRNAs and lack of studies, it is currently unclear what role piRNAs actually play in the pathogenesis of MCCs, which factors are causative and whether they are Piwil-2 dependent. Direct piRNA and RNA interaction with subsequent post-transcriptional gene silencing has been described as well as epigenetic regulation by hypo – and hypermethylation via the Piwil-2 / piRNA complex37,38,39,40.

Considering what we know about Piwil-2 as key-regulator of genomic integrity40,41 it is not surprising that its knock-down significantly altered protein profiles. In particular, 419 proteins were affected that have formerly been linked to transcription, translation, intracellular assembling and targeting processes. Most strikingly, downregulated proteins were especially involved in DNA-templated DNA replication pathways. String analyses helped us to further understand and identify altered protein clusters. One of those clusters comprised TRRAP and BRD8, both members of the EP400 complex, which is crucial for MVPyV ST mediated downregulation of p531,21. In more detail, the EP400 complex gets recruited by MYCL and MCPyV ST to activate downstream target genes, such as transcription of MDM2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which specifically binds and degrades p53 causing therefore a decrease of apoptosis42,43.

In addition, ORC4 and PRIM2 have been identified in another cluster and both proteins have previously been linked to the E2F mediated regulation of DNA replication. The E2F family of transcription factors in turn is essential for G1/S transition, therefore cell progression, and finally DNA replication. The tumor suppressor RB can oppose these effects by binding and repressing E2F transcriptions factors1,21,22. Interestingly, MCPyV LT binds and inactivates RB in MCCP, while RB (and p53) is generally mutated in MCCN1.

However, although our data fit well with both major MCC pathways, on the one hand TRRAP and BRD8 to the ST-MYCL-EP400 pathway (MYCL) and, on the other hand, ORC4 and PRIM2 to E2F transcription factors and cell cycle control (cell cycle), our subsequent analyses were not as significant as expected. For instance, decline of TRRAP and BRD8 should result in less MDM2 activity and therefore higher levels of p53 and increased apoptosis, which was not the case in our study. Secondly, we expected, based on that, also a more pronounced effect on the cell cycle, but indeed we observed only a 1.05 to 1.13 fold increase of cells in the G0/G1 phase.

We speculate that the significant upregulation of SOX-2 might be an explanation for these attenuated effects. As previously described, SOX-2 represents an established marker for MCs and is crucial for MCC tumorigenesis as well4,24,44,45. More precisely, SOX-2 can be directly upregulated by MCPyV LT through its Rb-inhibition domain and it represents a direct upstream transcriptional activator of ATOH1, which is required for MC development again4,23. Knock-down of SOX-2 led to a significant cell cycle arrest of our MCC cells (more pronounced than that of Piwil-2), which is in accordance to literature4,24. Therefore, the upregulation of SOX-2 fostering MCC maintenance or even progression most likely attenuates Piwil-2 effects. Nonetheless, our data are the first describing an interaction of the Piwil-2 / piRNA complex and SOX-2 in MCCs.

Despite the novelty and relevance of our data, it should be considered that complete Piwil-2 knock-out may facilitate to narrow down the broad range of dysregulated proteins and piRNAs in order to identify one single pathway as main causative player for the carcinogenic effect of Piwil-2 ± piRNA in MCCs.

Conclusion

High Piwil-2 expression was associated with advanced tumor stage, MCPyV positivity and worse oncological outcome. The downregulation of proteins related to the ST-MYCL-EP400 complex (MYCL) and the E2F family of transcription factors (cell cycle), might explain the role of Piwil-2 as poor prognosticator in MCCs. Surprisingly, Piwil-2 knock-down led to an upregulation of SOX-2 an opposing factor that warrants further research.

Materials and methods

Ethics & inclusion statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna prior to enrollment (1412/2015) and due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna waived the need of obtaining informed consent. Moreover, all methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study cohort

Between 01/1994 and 12/2015, 54 patients with MCCs were treated at the Medical University of Vienna. After exclusion of cases with missing clinical data (n = 23) or missing evaluable tumor tissue (n = 4), 27 patients (15 males, 12 females) with a median (± SD) age of 77.8 (± 10.1) were finally included. Clinical and socio-demographic characteristics, surgical and pathological reports and imaging findings were obtained from medical hospital records (Table 1). The disease-specific survival (DSS) was used as main oncological outcome parameter and was defined from time of diagnosis to date of death from MCC, while unrelated deaths or deaths from unknown causes were censored.

Immunohistochemistry

The monoclonal anti-Piwil-2 antibody (1:50, sc377347, Clone D-5, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany) was used as primary antibody for Piwil-2 detection. After antigen retrieval with ULTRA Cell Conditioning CC1 (pH 8.0) for 60 min (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA), the automated Ventana Benchmark staining platform with a universal DAB detection kit was utilized for immunohistochemical stainings. As previously described, the LT protein of the MCPyV (sc136172, 1:200, Santa Cruz) was used as marker for a MCPyV infection46,47.

Furthermore, we applied a scoring system ranging from 0 to 3 to assess Piwil-2 expression. MCCs with less than 3% of reactive tumor cells were classified as negative or absent expression (0), whereas remaining MCCs were further graded according to their staining intensities and their percentage of positive tumor cells into weak [(1), < 10% of reactive cells], moderate [(2), < 30%] or strong [(3), > 30%] Piwil-2 expressing MCCs. Two observers (S.J. and J.P.) independently assessed scoring. Patients with negative or weak staining (0–1) were classified as low and those with moderate to strong staining (2–3) as high Piwil-2 expression cohort.

Cell culture

Five human MCC cell lines (MCC13, MCC26, MKL1, PeTa, WaGa) were cultured in RPMI medium (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The MCC cell lines were provided with the kind permission of Dr. Houben48. RPMI medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (PAA Laboratories, Linz, Austria) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Aliquots of 5 × 105 cells of each cell line were seeded in 10 cm2 culture dishes. After 24 h cell lines were lysed with lysis buffer 200 µl Laemmli SDS sample buffer containing protease inhibitors and stored at -80 °C until further experiments.

Western blot

For western blotting, 50 µg protein was analyzed via SDS–PAGE electrophoresis (GE Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). Proteins were electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), which was dried and incubated in blocking buffer (5% non-fat dry milk in PBS) followed by immune overlay with monoclonal Piwil-2 antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology, Heidelberg, Germany; dilution 1:500), monoclonal GAPDH antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, UK; dilution 1:2000) or monoclonal cleaved caspase-3 antibody (Asp175; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA). After washing, bound antibodies were detected with HRP-labeled sheep anti-mouse-IgG (Amersham Life Science, UK) and immunoreactions were visualized by chemiluminescence using SuperSignal™ West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Transfection with SiRNA

Two stealth anti-Piwil-2 siRNAs (siRNA1: HSS123934; siRNA2: HSS123935) were used for transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). Aliquots of 5 × 105 Peta cells per ml, cultured without antibiotics, were seeded in 6 well plates according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Next, 2.5 ml OPTI-MEM medium (Gibco) and 50 µl Lipofectamine 2000 were mixed and incubated for 10 min. This solution was further mixed at equal volumes with the prediluted siRNA (13 µl in 500 µl) or scrambled control RNA, incubated at room temperature for another 10 min, until it was finally added to 4 ml RPMI medium (Gibco). Additionally, a mock control with Lipofectamine alone and untreated cells were used as control. After resuspension of cells in the prepared media, cells were cultivated for 48 h and then lysed for further analyses. Similarly, two stealth anti-SOX-2 siRNAs (siRNA1: HSS144045; siRNA2: HSS186041) were used for knock-down of SOX-2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA). Transfection of cell lines as well as all subsequent experiments were performed once with two technical replicates. Given that donor variability is eliminated when using a stable cell line, biological replication was deemed unnecessary.

Small RNA sequencing

Sequencing libraries were prepared at the Core Facility Genomics (Medical University of Vienna) using the NEB Next small RNA Library Prep Kit according to manufacturer’s protocols (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, UK). Libraries were QC-checked on a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a High Sensitivity DNA Kit for correct insert size and quantified using a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Pooled libraries were sequenced on a NextSeq500 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) in 1 × 50 bp single-end sequencing mode. Approximately 15 million reads were generated per sample. Reads in fastq format were analyzed on the Illumina Basespace platform using the Small RNA Sequencing analysis module (version 1.0.1), featuring bowtie aligner (version 0.12.8) and DESeq2 (version 1.0.17). Reads were aligned against the Homo sapiens maskedPAR UCSC hg19 reference and miRBase version 21, outputting read counts for each miRNA and piRNA in the database, respectively. For re-analysis starting from the counts generated in Basespace, differential gene expression between experimental groups was re-analyzed with DESeq2 (Version 1.0.17) in R49.

Proteome analysis

Cells were lysed using the Total Protein Extraction kit from Merck Millipore (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and protein precipitation was performed using dichloromethane (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and methanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Three volumes of methanol, one volume of dichloromethane, and three volumes of distilled water were added to one sample volume and incubated at -20 °C for 20 min. Then, samples were centrifuged at 9,000xg for 5 min at room temperature. The upper phase was discarded, and three volumes of methanol were added. Samples were centrifuged at 9,000xg for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded again, after which pellets were air-dried. Dry pellets were dissolved in 50 µl 50mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 0.1% RapiGest SF (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Protein concentration was measured by a nano spectrophotometer (DS-11, DeNovix, Wilmington, NC, USA). An aliquot of 20 µg protein was further reduced using 5mM dithiothreitol for 30 min at 60 °C and alkylated for 30 min in the dark by using 15 mM iodoacetamide (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Digestion with MS grade porcine trypsin (1:20, w/w) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was carried out overnight at 37 °C and aliquots of 1 µg digested protein were prepared and stored at -80 °C until injection.

Chromatographic separation was performed using a nano-RSLC UltiMate 3000 system with a PepMap C18trap-column (both Thermo Fischer Scientific) of 300 μm ID x 5 mm length, 5 μm particle size, 100 Å pore size for sample loading and desalting and a 200 cm C18 µPAC analytical column (PharmaFluidics, Ghent, Belgium; dimensions 5 μm pillar diameter, 2.5 μm inter-pillar distance, 18 μm pillar height, and 315 μm bed channel width). Gradient elution was performed by mixing mobile phase A (MPA: 95% H2O, 5% ACN, 0.1% FA) and mobile phase B (MPB: 50% ACN, 30% MeOH, 10% TFE, 10% of 0.1% FA) at 800 nl/min for the first 10 min at 5% MPB, and then 600 nl/min for 150 min during which MPB increased from 5 to 90%. Eventually the flow rate was increased to 800 nl/min and MPB returned to 5% until 240 min where reached.

Mass spectrometry analysis was performed using a Q Exactive Orbitrap Plus equipped with a Nanospray Flex ESI source (both Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) and stainless-steel emitter needle (20 μm ID x 10 μm tip ID). The needle emitter voltage was set to 3.1 kV, and the scan range was 200-2,000 m/z. Full MS resolution was set to 70,000, AGC target to 3E6, and maximum injection time was set to 50 ms. For the MS/MS analysis, the mass resolution was set to 35,000, AGC target to 1E5, and the maximum injection time to 120 ms. The isolation width for MS/MS was set to m/z 1.5, and top 15 ions were selected for fragmentation; single charged ions and ions bearing a charge higher than + 7 were excluded from MS/MS. Dynamic exclusion time was set to 20 s. The NCE was set to 30.

Raw MS/MS data were searched against the human SwissProt protein database (Version November 2020) with Proteome Discoverer 2.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the following parameters: Taxonomy: Homo sapiens; Modifications: carbamidomethyl on C as fixed modification, carboxymethylation on M as a variable modification; Peptide tolerance was set to 10 ppm and the MS/MS tolerance to 0.05 Da; trypsin was selected as the enzyme used and two missed cleavages were allowed; false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1%, and the decoy database search was used for estimating the FDR.

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed using the BrDU cell-cycle kit (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 24 h after siRNA transfection, KC were incubated with BrdU (10 µM) for 4 h. After fixation, cells were stained with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated anti-BrdU antibody for 30 min. Prior to FACS-analysis, 7-AAD was added. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using BD FACSCanto II and BD FACSDiva software (version 6.1.3) (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA). Gates were set according to the manufacturer’s instructions and data were evaluated using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0 software (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, USA) and R (v4.2.0; http://www.r-project.org). Data in the results section are shown as median ± standard deviation (SD) or mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Unpaired student’s t test and one-way ANOVA were used for normally distributed variables with two or more than two groups, respectively, and Tukey’s-B and Bonferroni correction were performed in case of multiple testing. Chi-square test was used to assess associations between nominal variables. Kaplan-Meier analyses and Log-rank test were assessed for survival analysis. Testing for differentially regulated proteins was performed using the R-package “limma”50.

Conference presentation

Preliminary results were presented at the 61th Annual Meeting of the Austrian Society of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD059625 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/profile/reviewer_pxd059625). Moreover, generated miRNA data are available in the SRA repository with the dataset identifier PRJNA1194193 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA1194193?reviewer=1d2i57a590u2b5b7gjlh8nnkqq). All data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

DeCaprio, J. A. Molecular pathogenesis of Merkel cell carcinoma. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 16, 69–91 (2021).

Feng, H., Shuda, M., Chang, Y. & Moore, P. S. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 319 (5866), 1096–1100 (2008).

Harms, K. L. et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 Merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 23 (11), 3564–3571 (2016).

Harold, A. et al. Conversion of Sox2-dependent Merkel cell carcinoma to a differentiated neuron-like phenotype by T antigen Inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 116 (40), 20104–20114 (2019).

Fan, K. et al. MCPyV large T Antigen-Induced atonal homolog 1 is a Lineage-Dependency oncogene in Merkel cell carcinoma. J. Invest. Dermatol. 140 (1), 56–65e3 (2020).

Lewis, C. W. et al. Patterns of distant metastases in 215 Merkel cell carcinoma patients: implications for prognosis and surveillance. Cancer Med. 9 (4), 1374–1382 (2020).

Lebbe, C. et al. European dermatology forum (EDF), the European association of Dermato-Oncology (EADO) and the European organization for research and treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur. J. Cancer. 51, 2396–2403 (2015).

Zeng, Q. et al. Role of PIWI-interacting RNAs on cell survival: proliferation, apoptosis, and cycle. IUBMB Life. 72 (9), 1870–1878 (2020).

Cox, D. N. et al. A novel class of evolutionarily conserved genes defined by Piwi are essential for stem cell self-renewal. Genes Dev. 12, 3715–3727 (1998).

Sasaki, T., Shiohama, A., Minoshima, S. & Shimizu, N. Identification of eight members of the argonaute family in the human genome. Genomics 82, 323–330 (2003).

Teixeira, F. K. et al. piRNA-mediated regulation of transposon alternative splicing in the Soma and germ line. Nature 552, 268–272 (2017).

Guo, D., Barry, L., Lin, S. S. H., Huang, V. & Li L.-C. RNAa in action: from the exception to the norm. RNA Biol. 11, 1221–1225 (2014).

Zhang, P. et al. MIWI and piRNA-mediated cleavage of messenger RNAs in mouse testes. Cell. Res. 25, 193–207 (2015).

Barckmann, B. et al. Aubergine iCLIP reveals piRNA-dependent decay of mRNAs involved in germ cell development in the early embryo. Cell. Rep. 12, 1205–1216 (2015).

Ng, K. W. et al. Piwi-interacting RNAs in cancer: emerging functions and clinical utility. Mol. Cancer. 15, 1–13 (2016).

Taubert, H. et al. Piwil 2 expression is correlated with disease-specific and progression-free survival of chemotherapy-treated bladder cancer patients. Mol. Med. 21, 371–380 (2015).

Qu, X., Liu, J., Zhong, X., Li, X. & Zhang, Q. PIWIL2 promotes progression of non-small cell lung cancer by inducing CDK2 and Cyclin A expression. J. Transl Med. 13, 301 (2015).

Zhou, S., Yang, S., Li, F., Hou, J. & Chang, H. P-element induced wimpy protein-like RNA-mediated gene Silencing 2 regulates tumor cell progression, apoptosis, and metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Int. Med. Res. 49 (11), 3000605211053158 (2021).

Chattopadhyay, T., Biswal, P., Lalruatfela, A. & Mallick, B. Emerging roles of PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) and PIWI proteins in head and neck cancer and their potential clinical implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 1877 (5), 188772 (2022).

Pammer, J. et al. PIWIL-2 and PiRNAs are regularly expressed in epithelia of the skin and their expression is related to differentiation. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 312 (10), 705–714 (2020).

Ahmed, M. M., Cushman, C. H. & DeCaprio, J. A. Merkel cell polyomavirus: Oncogenesis in a stable genome. Viruses 14 (1), 58 (2021).

Cam, H. & Dynlacht, B. D. Emerging roles for E2F: beyond the G1/S transition and DNA replication. Cancer Cell. 3 (4), 311–316 (2003).

Ostrowski, S. M., Wright, M. C., Bolock, A. M., Geng, X. & Maricich, S. M. Ectopic Atoh1 expression drives Merkel cell production in embryonic, postnatal and adult mouse epidermis. Development 142 (14), 2533–2544 (2015).

Laga, A. C. et al. Expression of the embryonic stem cell transcription factor SOX2 in human skin: relevance to melanocyte and Merkel cell biology. Am. J. Pathol. 176 (2), 903–913 (2010).

Haymerle, G. et al. Expression of merkelcell polyomavirus (MCPyV) large T-antigen in Merkel cell carcinoma lymph node metastases predicts poor outcome. PLoS One. 12 (8), e0180426 (2017).

Yang, A. et al. The impact of Merkel cell polyomavirus positivity on prognosis of Merkel cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 12, 1020805 (2022).

Oh, S. J., Kim, S. M., Kim, Y. O. & Chang, H. K. Clinicopathologic implications of PIWIL2 expression in colorectal Cancer. Korean J. Pathol. 46 (4), 318–323 (2012).

Zhang, H. et al. The expression of stem cell protein Piwil2 and piR-932 in breast cancer. Surg. Oncol. 22 (4), 217–223 (2013).

Zhao, X. et al. PIWIL2 interacting with IKK to regulate autophagy and apoptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell. Death Differ. 28 (6), 1941–1954 (2021).

Chen, Y. J. et al. Expression and clinical significance of PIWIL2 in hilar cholangiocarcinoma tissues and cell lines. Genet. Mol. Res. 14 (2), 7053–7061 (2015).

Eckstein, M. et al. Piwi-like 1 and – 2 protein expression levels are prognostic factors for muscle invasive urothelial bladder cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 17693 (2018).

Hu, W. et al. PIWIL2 May serve as a prognostic predictor in cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. BUON. 25 (6), 2721–2730 (2020).

Erber, R. et al. PIWI-Like 1 and PIWI-Like 2 expression in breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 12 (10), 2742 (2020).

Li, W. et al. The prognosis value of PIWIL1 and PIWIL2 expression in pancreatic Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 8 (9), 1275 (2019).

Iliev, R. et al. Decreased expression levels of PIWIL1, PIWIL2, and PIWIL4 are associated with worse survival in renal cell carcinoma patients. Onco Targets Ther. 9, 217–222 (2016).

Sai Lakshmi, S. & Agrawal, S. PiRNABank: a web resource on classified and clustered Piwi-interacting RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 (Database issue), D173–D177 (2008).

Collins, L. J. & Penny, D. The RNA infrastructure: dark matter of the eukaryotic cell? Trends Genet. 25 (3), 120–128 (2009).

Malone, C. D. & Hannon, G. J. Small RNAs as guardians of the genome. Cell 136 (4), 656–668 (2009).

Han, Y. N. et al. PIWI proteins and PIWI-Interacting RNA: emerging roles in Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 44 (1), 1–20 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. The emerging role of the pirna/piwi complex in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 18 (1), 123 (2019).

Robine, N. et al. A broadly conserved pathway generates 3’UTR-directed primary PiRNAs. Curr. Biol. 19, 2066–2076 (2009).

Slack, A. et al. The p53 regulatory gene MDM2 is a direct transcriptional target of MYCN in neuroblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102 (3), 731–736 (2005).

Chen, L. et al. p53 is a direct transcriptional target of MYCN in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 70 (4), 1377–1388 (2010).

Kervarrec, T. et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus T antigens induce Merkel cell-Like differentiation in GLI1-Expressing epithelial cells. Cancers (Basel). 12 (7), E1989 (2020).

Novak, D. et al. SOX2 in development and cancer biology. Semin Cancer Biol. 67 (Pt 1), 74–82 (2020).

Erovic, B. M. et al. Significant overexpression of the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) large T antigen in Merkel cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 35 (2), 184–189 (2013).

Fochtmann, A. et al. Prognostic significance of lymph node ratio in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 272, 1777–1783 (2015).

Houben, R. et al. Mechanisms of p53 restriction in Merkel cell carcinoma cells are independent of the Merkel cell polyoma virus T antigens. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133 (10), 2453–2460 (2013).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15 (12), 550 (2014).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (7), e47 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Barbara Neudert (Clinical Institute of Pathology, Medical University of Vienna) for help with immunohistochemical staining.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJ, JP, ES, UK, RH, DC, MM, GM, MB, SD, MU, KK did experiments and analyses. SJ wrote main manuscript. All authors: Review and revision of manuscript. SJ, SG, KK, MU: Responsible for statistical analyses. SJ, BME: Conception and design of study. SJ, ES, MM, GM, MU, KK: Figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Janik, S., Pammer, J., Simader, E. et al. Piwil-2 represents a poor prognosticator in Merkel cell carcinomas that regulates oncoproteins, cell cycle arrest and SOX-2 expression. Sci Rep 15, 39198 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06247-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06247-8