Abstract

Topological crystalline insulators (TCIs) are a class of materials with metallic surface states on high-symmetry crystal surfaces. TCIs discovered so far have cubic structures, which, compared to the layered structure of first-generation topological insulators such as \(\text {Bi}_{2}\text {Se}_{3}\) and \(\text {Bi}_{2}\text {Te}_{3}\), offer the potential for branched structures or strong coupling with other materials for large proximity effects. In the present work we implement low-energy \(\overrightarrow{\text {k}}\cdot \overrightarrow{\text {p}}\) theory and the Green’s function technique on the tight-binding Hamiltonian to study the major electronic properties and electronic thermal conductivity (ETC) of pristine TCI SnTe (001). For the first time, we calculate the ETC of this material and explore the effects of strain and electric fields to tune its topological phase. The xx component dominates in the pristine case (5.311 \(\text {Wm}^\text {-1}\text {K}^\text {-1}\) at room temperature) aligning well with related experimental results on similar materials. We assess the impact of uniaxial and biaxial strains, observing an overall ETC increase (up to 159% for the xx component under uniaxial strain and 215% for the xy component (Anomalous Righi-Leduc effect) under biaxial strain). Applying an electric field further enhances ETC in all components (as high as 14.367 \(\text {Wm}^\text {-1}\text {K}^\text {-1}\) for xx component at 190 K). These findings highlight strain and electric field perturbations as effective methods to control the thermal properties of SnTe (001), offering insights into its future applications in thermoelectrics and tunable electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The fundamental principles of matter can be understood by studying the symmetry and topology of materials1,2,3,4. The intriguing characteristics of topological properties, as well as the transitions between different topological phases, have garnered significant attention in condensed matter physics5,6,7,8,9. The practical applications of these materials are limited since on/off switching is not possible due to the gapless nature of such 2D materials. Various approaches have been developed so far, including thickness engineering (thin films), strain, Rashba spin-orbit coupling, proximity coupling to ferromagnetism, dilute charged impurities, chemical doping, and more10,11,12,13. These techniques enable the creation of a band gap, facilitating the switching on and off of such materials. These advancements position these materials as promising candidates for the next generation of low-energy-consumption electronics and spintronics14,15,16,17,18.

Topological insulators (TIs)19,20, topological superconductors21,22, Chern insulators23, topological crystalline insulators (TCIs)2,11,21, Weyl semimetals24,25 and Dirac semimetals24,26,27 are examples of topological materials28,29,30 in which surface/edge and bulk bands demonstrate properties different from conventional 3D topologically trivial insulators or metals31,32. A variety of quantum quasiparticles such as Dirac, Weyl, and Majorana fermions play a significant role in describing the properties of such materials33. The number of Dirac cones present on the surface or edge, along with the associated protective symmetry, are mostly responsible for the difference between strong TIs and TCIs. An odd number of Dirac cones preserve the topological characteristics of strong TIs, whereas an even number of Dirac cones occur on the surface or edge of TCIs34,35,36. Furthermore, the gapless surface/edge states in TIs are protected by the time-reversal symmetry37, whereas those in TCIs are protected by crystal symmetries including rotation38,39 and mirror12,40 symmetries. Consequently, these enable us to more readily adjust the topological surface states in TCIs through temperature changes, mirror symmetry breaking, and other methods such as doping, strain engineering, or applied electric fields, leading to topological phase transitions from a trivial to a non-trivial phase6,7. These novel TCI characterizations have been observed both experimentally and theoretically. Experimentally by using the angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy method in IV–VI semiconductors10,16,41,42,43,44 and theoretically through the tight-binding model and density functional theory (DFT)45,46. SnTe, \(\text {Pb}_\text {1-x}\text {Sn}_\text {x}\text {Se}\) (x\(\ge\) 0.2) and \(\text {Pb}_\text {1-x}\text {Sn}_\text {x}\text {Te}\) (x\(\ge\) 0.4) are among the first materials discovered to have gapless surface states protected by lattice symmetries1,8,10,11,12,41,47,48,49. Two types of surface states have been identified for SnTe and related alloys: (a) (110) and (001) surface states, and (b) (111) surface states50. Since the orientation of the crystal face influences the tuning of the gap, researchers are particularly interested in the first type for two reasons: The first is that they have been experimentally observed in SnTe (001) and related alloys, and the second is that they exhibit mirrored Dirac cones, making them potential carriers of interesting features33,51. Due to these reasons, we have decided to examine the ETC of this specific surface, which has not been previously studied.

Several studies have made efforts to investigate the topological phase transition as an electronic property to date. To the best of our knowledge, although there have been a number of studies52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 on the thermal conductivity of TCI SnTe (001), the main focus of all of them is calculating the total thermal conductivity and phononic contribution to this property using mostly classical and semi-classical methods. This encouraged us to utilize the purely quantum mechanical approach to explore the ETC in the pristine case and the presence of physical and electrical perturbations (strain and external electric field, the Stark effect), which is still missing in the literature and should be studied. The study of the thermal conductivity is technologically helpful in managing the generated heat by tuning the electric field and physical deformations in nanodevices.

In this manuscript, we present a novel theoretical investigation of the impact of strain and perpendicular electric field (Stark field) on the ETC of SnTe (001), marking a significant contribution to the existing literature. We achieved this by utilizing the low-energy \(\overrightarrow{\text {k}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\text {p}}\) theory12,33,61, the Green’s function method62,63 and the Kubo-Greenwood (KG) transport approach.64,65,66 With regard to experimental studies, the modification of the gap by applying strain49,67 and a perpendicular electric field61,68 provides opportunities for a wide range of potential applications across various disciplines. One can make use of such property for some purposes in which the speed of heating and cooling of the system is important. To this end, we focus on the band structure, the electronic density of states (DOS) and the ETC quantities.

The presentation of the paper contains the following sections. In the Theory and Method section, we introduce the pristine effective low-energy Hamiltonian of the SnTe (001) surface which is used to present the main electronic properties (Band Structure and DOS) with the use of Green’s function approach. Also, the ETC formulation in terms of the Onsager transport coefficients (which are calculated by the KG approach) is included to investigate the ETC of the pristine and perturbed states. Pristine Case section deals with the intrinsic ETC of this material and describes the behavior of different components of it. The Perturbed Cases section is divided into physical and electrical perturbations namely strain and Stark effect. We first explore the effects of uniaxial and biaxial strain on the ETC, followed by an investigation of the Stark effect. And finally, a summary of the results and predictions is presented in the Conclusions section.

Theory and method

We begin by providing a concise overview of the formation of the topological gapless phase on the (001) surface of TCIs. To this end, we start by going over the bulk band structure of SnTe, which is the basis for determining surface states.

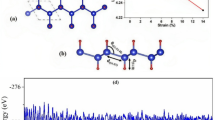

The crystal structure of SnTe is a simple rocksalt with corresponding Brillouin zone depicted in Fig. 112. In IV–VI semiconductors, the band gap occurs at four L points. The Bloch state of the valence band at L in ionic insulators like PbTe is obtained from the p orbitals of the anion Te, whereas the Bloch state of the conduction band is taken from the cation Pb69.

SnTe, on the other hand, has an intrinsically inverted band ordering, where the conduction band comes from Te and the valence band from the cation Sn. This band inversion develops the TCI phase in SnTe in comparison to a trivial ionic insulator12. In SnTe and its related alloys, the bulk Brillouin zone points are mapped onto the surface Brillouin zone (SBZ) points, resulting in the emergence of an even number of Dirac cones. The responsible elements for topological features on the TCI SnTe (001) are four gapless Dirac cones, two of which are along the \(\Gamma\)X\(_1\) and the other two along the \(\Gamma\)X\(_2\) direction of the SBZ. Taking into account that the SnTe (001) SBZ has a square lattice structure, indicates that the X\(_1\) and X\(_2\) points can be interchanged by a rotation of \(\pi /2\). Thus, it is not required to examine both points. Conversely, the two Dirac cones around the X\(_1\) (X\(_2\)) point have mirror symmetry with respect to the yz (xz) plane12,33,70,71. The band structure close to each L point can be characterized using a four-band \(\overrightarrow{\text {k}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\text {p}}\) theory, based on the four Bloch states at L, \(\psi _{\sigma ,\tau }\)(L)71. Here, \(\sigma\) = 1(-1) denotes the state formed by the cation (anion), and \(\tau\) corresponds to the Kramers doublet. The \(\overrightarrow{\text {k}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\text {p}}\) Hamiltonian \(\mathcal {H}(\overrightarrow{k})\) is defined as follows12,33:

Here, \(\overrightarrow{s}\) and \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }\) denote two sets of Pauli matrices in distinct spaces and \(k_3\) is oriented parallel to the \(\Gamma\)L direction, while \(k_1\) is aligned with the (1\(\overline{\text {1}}\)0) reflection axis. Also the sign of \(m_0\) specifies the two distinct sorts of band ordering, assigning \(m_0 > 0\) for PbTe and \(m_0 < 0\) for SnTe, by convention12.

For the desired case of this study, SnTe (001) surface, L points are projected on the surface momenta with equal values for which (L\(_1\),L\(_2\))\(\rightarrow\)X\(_1\) and (L\(_3\),L\(_4\))\(\rightarrow\)X\(_2\) as illustrated in the right part of Fig. 1. This leads to the emergence of a peculiar spin texture and band dispersion, brought by their interaction, which creates distinct kinds of topological surface states33,61.

First, we consider a smooth interface with a trivial insulator, then we exert an adiabatic deformation on this interface for the purpose of connecting to the desired surface states. This gives rise to the Hamiltonian corresponding to (001) surface states given by12,33

where \(k_x\) and \(k_y\) are parallel to \(\Gamma\)X\(_2\) and \(\Gamma\)X\(_1\), respectively and \(\overrightarrow{k}\) is measured from X\(_1\). Note that in this study we only examine X\(_1\) for all the results apply to the X\(_2\) point via a \(\pi /2\) rotation (C\(_4\) symmetry). \(\overrightarrow{\sigma }\) and \(\overrightarrow{\tau }\) represent a set of Pauli matrices in correspondence with the Kramers doublet of each flavor. \(\eta _x = 2.4\) eVÅ and \(\eta _y = 1.3\) eVÅ are typical Fermi velocities along the x- and y-direction obtained from numerical ab initio calculations which are inherently different33,61,68. The two additional terms, \(m = 70\) meV and \(\delta = 26\) meV, portraying the lattice scale intervalley scattering, are off diagonal in flavor space12,50,72. It is worth noting that the associated symmetries has been taken to account. The matrix representation for the aforementioned Hamiltonian is shown as follows:

The above matrix is diagonalized as usual to provide four surface bands with dispersion energies:

where \(\mu = \pm 1\) and \(\nu = \pm 1\) refer to the dual (\(\mu\)) high (\(\nu =+1\)) and low (\(\nu = -1\)) energy surfaces plotted in Fig. 3. The achieved band structure by incorporating this theory shows great consistency with the experimental results of the Tanaka et al.16 work which validates our chosen theory so far.

Figure 2 illustrates how two Dirac cones, \(\Lambda _+\) and \(\Lambda _-\), centered at X\(_1\), which result from the interaction between the two {L\(_1\),L\(_2\)} valleys, topologically characterize the SnTe (001) surface states. At this point, two crossed bands with mirror symmetry about the xy-plane are placed at energy \(\mathcal {E}^\mu _{\text {X}_1} = \mu \sqrt{m^2 + \delta ^2}\) and two Dirac cones with the momentum \(\Lambda ^\pm _y = \sqrt{n^2 + \delta ^2} / \eta _x\) are situated at energy \(\mathcal {E} = 0\) meV.

Figure 2 highlights the corresponding Fermi surfaces pertaining to three distinct energy ranges, \(|\mathcal {E}| < \delta\) , \(|\mathcal {E}| = \delta\) and \(|\mathcal {E}| > \delta\). In the first scenario (\(|\mathcal {E}| < \delta\)), there exist two distinct electron wave pockets positioned at \(\Lambda ^\pm _y\) and along the \(\Gamma\)-X\(_1\) line. As the Fermi energy is elevated beyond the Dirac points to \(|\mathcal {E}| = \delta\), a Lifshitz transition occurs, resulting in a modification of the Fermi surface topology. Consequently, at this particular energy level, two separate electron wave pockets converge at saddle points \(S_\pm = (\pm m / \eta _x)\). Subsequently, in the last case (\(|\mathcal {E}| > \delta\)), as the Fermi energy surpasses the threshold of the \(\delta\) value, the two previously separated and intersecting electron wave pockets transform into two pockets centered at X\(_1\).

The electronic DOS as a function of carrier energy is another electronic parameter that aids in understanding the changes in the underlying physics of the system. To achieve DOS, we employ the reciprocal-space Green’s functions approach. The electronic DOS are related by the following equation62,63:

The overall DOS is acquired through the summation across the entire SBZ. Here \(\beta\) refers to both spin and surface states. As one can see in this equation, DOS is explained in terms of the imaginary parts of the diagonal terms of the Green’s function. The relation used to compute the Green’s function matrix is \(G_0 (\overrightarrow{k}, \mathcal {E}) = \left[ \mathcal {E} + i {\varvec{o}}^{+} - {\mathcal H}_{\text {X}_1} (\overrightarrow{k}) \right] ^{-1}\), where the quantity \({\varvec{o}}^{+}\) is the broadening factor which is a very small number that in this work is set to 1 meV. Also \(\underline{\underline{\mathcal {H}}}_{\text {X}_1}\) is the matrix representation of the clean Hamiltonian in Equation (2) in the basis set of \(\{|c\uparrow \rangle , |a\uparrow \rangle , |c\downarrow \rangle , |a\downarrow \rangle \}\) (c (a) and \(\uparrow\) (\(\downarrow\)) stand for the cation (anion) sublattice and the spin up (down) degrees of freedom, respectively)62,63. Since we are only interested in the diagonal terms of the Green’s function which are used in the DOS expression, the following describes these elements:

Here \(\zeta = {{\left( {\eta _x}^2 {k_x}^2 + {\eta _y}^2 {k_y}^2 \right) }}^2 + 2 {\left( {\eta _x}^2 {k_x}^2 - {\eta _y}^2 {k_y}^2 \right) }{\left( \delta ^2 - m^2 \right) } +{{\left( \delta ^2 +m^2\right) }}^2 - \mathcal {E}^2 (2 \delta ^2+ 2 {\eta _x}^2{k_x }^2 + 2 {\eta _y}^2 {k_y}^2 +2 m^2-\mathcal {E}^2)\) and \(\tilde{\mathcal {E}} = \mathcal {E} + i {\varvec{o}}^{+}\). Based on the aforementioned calculations, the 2D electronic band structure and the DOS of SnTe (001) surface states across the high symmetry points \(\Gamma\)-X-M are illustrated in Fig. 3. The 2D electronic band structure exhibits three significant energy levels, identified as \(|\mathcal {E}|\) equal to \(\delta\), \(2 \delta\), and \(\sqrt{m^2 + \delta ^2}\), where distinct features such as a van Hove singularity, a notch, and a valley are observed, respectively.

The Lifshitz transition occurs at the energy value of \(|\mathcal {E}| = \delta\), which is associated with the saddle points \(S_1\) and \(S_2\), ultimately resulting in the emergence of van Hove singularities. The configuration of the DOS illustrated in the graph demonstrates a prominent concordance with the findings presented in references12,50, and73.

Next, we employ the Kubo-Greenwood method and the well-established theoretical description of charge and heat transport in associated materials to determine the electronic transport properties of TCI SnTe (001)74. This choice is due to the fact that this method is fully quantum mechanical and valid at all temperatures. Additionally, our numerical calculations will incorporate the Onsager transport coefficients (OTCs) \(\mathcal {L}\) and linear response theory75. A gradient of electrical potential and temperature, represented as \({\varvec{E}}^{\beta }\) and \(\nabla ^\beta T\), respectively, along the Cartesian direction \(\beta\), can generate electrical and thermal currents. In this formalism, these fields are related to the \(\alpha\) components of the respective fluxes \({\varvec{J}}^\alpha _1\) (charge) and \({\varvec{J}}^\alpha _2\) (heat) by:76

where e is the elementary unit of electric charge. Also, OTC \(\mathcal {L}^{\alpha \beta }_{mn} = \mathcal {L}^{\alpha \beta }_{nm}\) (\(m,n \in \{1,2\}\)) are associated with ETC through:

Pristine SnTe is a widely recognized semiconductor that exhibits a high density of p-type carriers, around (\(10^{21}\)cm\(^{-3}\)), due to the presence of intrinsic Sn vacancies77. With regard to phononic thermal conductivity, phonons usually play a dominant role in the thermal conductivity quantity but their contribution here, is comparable to that of electrons60,78. The large atomic masses of Sn and Te also counteract the anisotropy of the hinge-like structure. In general, the anisotropic feature of phonon transport in SnTe could be much weaker than that of electrical transport52. Given that the phononic aspect of thermal conductivity has been previously computed (see Table 1) and considering the reasons mentioned, this article focuses solely on the electronic aspect to fill a gap in the literature. The conventional approach involves the utilization of the Wiedemann-Franz law, expressed as \(\kappa \equiv \kappa _e=N_L \sigma _e T\), with \(N_L\) denoting the Lorenz number, to determine the ETC (\(\kappa\)) in relation to electrical conductivity (\(\sigma _e\)). Nevertheless, in the case of semiconductors, the values of \(N_L\) used for metals (\(N_{L_0} = (\pi ^2/3)k_B^2 /e^2\)) may not be applicable79. With this in mind, we proceed to a brief introduction to Kubo-Green approach. Using Kubo’s quantum-statistical linear response theory14,80, which enables the correlation functions to be factorized into products of single-particle Green’s functions and their time derivatives, a general formula to calculate OTCs can be derived from the current-current time-correlation functions in the KG approach78,81. The correlation functions of current operators specified in Eq. (7) have the following definition:

Here A, demonstrates the area of the system including the number of unit cells considered in the numerical computations, \(\tau\) stands for the imaginary time and \(i \omega _M\) is the Matsubara frequency. For our intended purpose, we focus on the acceptable \(\omega \rightarrow 0\) limit (completely static direct-current (DC) OTCs), which leads to the transport coefficients being \(\mathcal {L}^{\alpha \beta }_{mn} = \lim _{\omega \rightarrow 0}\textrm{Im} ~ \mathcal {L}^{\alpha \beta }_{mn} (i \omega _m \rightarrow \omega + i {\varvec{o}}^{+})\) Assessing the time-autocorrelation function in the limit of dimension \(d = 2\) in the Heisenberg picture and considering the previous limit, the transport coefficients take the form as follows:

Here \(n_\text {\tiny FD} = 1/[1+ \exp (\mathcal {E}/k_B T)]\) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution function and \(\mathcal {V}^{\mu \nu }_{\alpha }(\overrightarrow{k}) = \partial \mathcal {E}^{\mu \nu }(\overrightarrow{k})/\hbar \partial k_\alpha\) stands for the group velocity of Dirac fermions of the SnTe (001) surface states.

Pristine case

Before investigating the impact of certain perturbations, let us look at the ETC in the pristine state. In contrast to Topological Insulators (TIs) in which an odd number of Dirac cones exist due to time-reversal symmetry, TCIs have an even number of Dirac cones that are safeguarded by specific crystal point group symmetries. While in TIs, gapless surface states emerge where bulk gap states are formed, the gapless surface states in SnTe (001) and similar alloys lack protection from time-reversal symmetry and are not positioned at the same location as bulk states (the intersecting bands at X\(_1\) and X\(_2\) points). Consequently, the linear and parabolic dispersions of surface and bulk states in SnTe (001) do not align at the same momentum (which remains invariant under time-reversal symmetry) as in TIs, indicating potential differences in transport properties. Equation (10) highlights the significant impact of dispersion energy on the OTCs, particularly with a greater reliance in \(\mathcal {L}_{12}\) and \(\mathcal {L}_{22}\) where the \(\mathcal {E}\) stays put in the integral. The xx, yy, and xy components of the ETC (\(\kappa\)) of the pristine SnTe (001) surface states with respect to temperature are shown in Fig. 4. The xy component is also known as Anomalous Righi-Leduc conductivity82,83 which is the thermal analog of the Hall conductivity. To ensure that thermal effects predominate and high quantum effects are no longer included in the high-temperature domain, we set the temperature range 0 to 1000 K in all calculated quantities.

Figure 4 demonstrates that all components of the ETC exhibit an upward trend with temperature until reaching the critical temperature \(T_c = 190\) K. Subsequently, they experience a decline, which aligns well with experimental investigations conducted on related materials like PbTe81 Pb\(_{0.6}\)Sn\(_{0.4}\)Te14,78 and Pb\(_{0.5}\)Sn\(_{0.5}\)Te84,85

The ascending and descending trends are explicable by the fact that the carrier mobility of the system is negligible at low temperatures, making the transition probability of carriers to be close to zero. With the escalation of thermal energy, the transition probability rises as a result of elevated carrier mobility. Nevertheless, upon reaching the critical temperature (\(T_c\)), an equilibrium caused by a scattering process is established, halting the inclination in transition probability, leading eventually to a decline. Consequently, upon surpassing this critical thermal energy threshold, the system transitions into a so-called diffusive regime. In this regime, scattering events dominate the increase in transition probability caused by the rise in temperature. This reduces carrier mobility and the efficiency of heat transport, leading to a decrease in the ETC. This process is similar to the Umklapp process, which applies to phonons.

The ETC figures at room temperature (300 K) for xx, xy and yy components are 5.311, 1.012 and 0.046 Wm\(^{-1}\)K\(^{-1}\), respectively. The outcomes for \(\kappa _{xx}\) and \(\kappa _{xy}\) are in good agreement with previous works on the thermal conductivity in monolayered, thin film and bulk cases in the sense that they are within a similar range of magnitudes. (See Table 1)

Scrutinizing the values corresponding to each component, we find that a major part of the ETC arises from the xx component and a smaller portion is due to the xy component. However, \(\kappa _{yy}\) plays a minute role in contributing to the total ETC which can be described by the intrinsic anisotropy in the propagation of fermions which manifests itself in distinct values for \(\mathcal {V}^{\mu \nu }_x\) and \(\mathcal {V}^{\mu \nu }_y\). The intrinsic anisotropy stems from the positioning of L points, which lie at the edges of the whole Brillouin zone. This leads to a non-homogeneous spin-orbit interaction at these points. For a detailed explanation, refer to the paper by Ezawa68.

The ultra-low thermal conductivity in yy component opens a door to a wide range of opportunities in engineering devices with different thermal conductivity for different directions. From a physical perspective, the unexpected characteristics of the ETC can be traced back to the various intrinsic symmetries present in the edges containing an even or odd quantity of atoms on the (001) surface of SnTe11,12,21,33,40. It is worth noting the individual expressions for the briefly mentioned velocities in Eq. (10). The expanded expressions for \(\mathcal {V}^{\mu \nu }_{\alpha }(\overrightarrow{k})\) are as follows:

The distinction between two velocities is of utmost importance when establishing the lines between high-symmetry regions. The variance in the propagation of electronic atomic waves along different paths is evident in Fig. 2 and 3, as indicated by the emergence of distinct bands. However, the transport coefficients are heavily influenced by the dispersion energy, resulting in distinct ETCs along different directions. In simple terms, the velocities convey that the intervalley scattering potentials described by m and \(\delta\) in the velocities have a role in defining the dominating contribution of charge and heat currents in transport.

Perturbed cases

Strain effects

A commonly held understanding is that strain causes atoms’ spatial wave functions to condense and tighten, resulting in bonding and non-bonding states as well as displacement \(\overrightarrow{u}\) of the Dirac points on the surface of SnTe (001). Nonetheless, various behaviors are expected based on the type of the strain. Strain causes the Dirac points to move without time-reversal symmetry breaking, but in some cases it leads to mirror-symmetry breaking and therefore, band gap opening88,89.

These quantum effects appear in transport, and consequently in the topological phase in general. An approach to such displacement is a strain-induced gauge field vector potential like \(\overrightarrow{A} = \tilde{\overrightarrow{\Lambda }}' - {\overrightarrow{\Lambda }}'\) where \({\overrightarrow{\Lambda }}'\) and \(\tilde{\overrightarrow{\Lambda }}'\) are the momenta before and after applying the strain. It has been found that \(\overrightarrow{A}_{x/y}\) has a linear correlation with the strain fields \(u_{ij} = (\partial _j u_i + \partial _i u_j)/2\) via:49,67

in which \(\alpha _i\) are the independent coupling constants and \(u_{xy/yx}\) represent the shear terms. As can be observed, the strain causes a linear displacement of the Dirac points both uniaxially and biaxially. Neglecting the shear terms, the momenta under strain can be expressed by:

for \(\alpha _1 = 0.3\) \(\text {\text{\AA }}^{-1}\) and \(\alpha _2 = 1.4\) \(\text {\text{\AA }}^{-1}\)67. Hence, we apply the linearly inward shifts of the momenta near the \(X_1\) point in the SBZ. The effects of uniaxial (either \(u_{xx}\) or \(u_{yy}\)) and biaxial (\(u_{xx}\) = \(u_{yy}\)) strains on the ETC are examined in the following.

The strain-induced DOS and ETC are produced by substituting Eqs. (12) and (13) into the dispersion energy and the Green’s functions. It is essential to note that the ETC exhibits symmetry in relation to the strain sign. This is because in Eq. (10), the summation is performed over all k points of the SBZ. Regardless of whether the strain is positive or negative, it is observed that the transport coefficients remain unchanged when the sign of k is inverted. Nevertheless, the existence of strain does not invalidate the significant anisotropy between components. From a physical standpoint, the altered band gap of the primary system has a significant impact on the change in the ETC. In this situation (strain turned on), the current dispersion energy relation takes the form

where \(\overrightarrow{\tilde{k}}\) is the altered form of the previous \(\overrightarrow{k}\); Hence, it is clear that the strain components have an impact on the band structure. Although this shifts the location of the Dirac points, it does not open the band gap. The anisotropic rates are due to the strain-induced alterations in Fermi velocities, which are significantly impacted by the directional character of p orbitals in topological materials, that make the hopping inevitably anisotropic67.

Correspondingly, the strain impacts the group velocity of Dirac fermions near the gap edges and then the Green’s functions (affected by strain-induced energy and \(\overrightarrow{\tilde{k}}\)), group velocities and the strain-induced energy itself in Eq. (10) leads to modifications in ETC. For the intensity of applied strain, we have chosen 0.5, 0.75 and 1 percent compressive and tensile strains. These specific choices were made due to the experimental limits in deforming the material synthesized on a substrate in accordance to the experimental paper by Walkup et al.67. Considering the orientation of the thermal gradient (\(\beta\)) and the calculated component of \(\kappa _{\alpha \beta }\), it follows naturally that when \(\beta\) is x(y), for \(\alpha =\) y(x) We concentrate only on the biaxial strain. In contrast, for \(\kappa _{xx/yy}\) we also investigate the uniaxial case. In hindsight, let us divide the following into two sections: biaxial and uniaxial strain:

Uniaxial strain

As mentioned before, regarding the mutual direction of the thermal gradient and the measuring orientation, the application of uniaxial strain leads to significant alterations in the thermal conductivity components \(\kappa _{xx}\) and \(\kappa _{yy}\). These modifications arise from the strain-induced changes in the electronic band structure, which directly influence the thermal transport properties of the material. The observed increases in \(\kappa _{xx}\) and \(\kappa _{yy}\) suggest an enhancement in the carrier mobility and the DOS near the Fermi level, which are critical factors for improving thermal conductivity.

ETC of SnTe (001) vs. temperature under three different uniaxial strains along (a) x direction for xx and (b) y direction for yy component. The solid blue line represents the pristine case, the dash-dotted green line shows the 0.5% strain, the dotted purple line denotes 0.75 % and the dashed red line corresponds to 1 % strain.

The data, illustrated in Fig. 5, reveal that \(\kappa _{xx}\) exhibits substantial amplification, increasing by 47%, 90%, and 159% for strains of 0.5%, 0.75%, and 1%, respectively. Similarly, \(\kappa _{yy}\) shows notable growth, with 49%, 63%, and 84% increases for the corresponding strain levels. This uniform enhancement in both \(\kappa _{xx}\) and \(\kappa _{yy}\) indicates that the uniaxial strain effectively modulates the electronic structure in a manner that consistently boosts the thermal conductivity across different directions. Moreover, our results demonstrate that these enhancements in thermal conductivity are maintained across a wide temperature range, implying that the strain effects are mostly independent of temperature. This temperature independence suggests that uniaxial strain can be a robust method to optimize the thermal properties of SnTe (001) in various thermal environments.

The anisotropic nature of the thermal conductivity modifications also highlights the potential for directional tuning of the material’s properties. By carefully selecting the direction and magnitude of the applied strain, it is possible to tailor the thermal conductivity to meet specific application requirements. This flexibility makes uniaxial strain a valuable tool for enhancing the performance of thermoelectric devices, where precise control of heat flow is essential.

Biaxial strain

The biaxial strain, applied symmetrically along two orthogonal directions, results in substantial enhancements in all components of the ETC. As depicted in Fig. 6, \(\kappa _{xx}\) experiences an additional enhancement of 23%, 41%, and 71% for 0.5%, 0.75%, and 1% biaxial strain, respectively. This enhancement builds on the increases observed under uniaxial strain, highlighting the cumulative effect of applying strain in multiple directions. For \(\kappa _{yy}\), the biaxial strain contributes to a 14%, 27%, and 49% boost over the values achieved with the uniaxial strain. The biaxial strain anisotropically modifies hopping parameters, causing unequal Dirac node shifts in orthogonal directions.67 The increase in the ETC is associated with the enhanced mobility of charge carriers and, consequently, their velocities, as described in Eq. (11). This enhanced asymmetry under biaxial strain boosts the velocities and therefore \(\kappa _{xy}\), offering a stronger effect than uniaxial strain.

Interestingly, although the ETC under biaxial strain for each intensity surpasses the values achieved with uniaxial strain at the same intensity, it does not exceed the value corresponding to the next higher intensity in the uniaxial case. For example, the ETC for 0.75% biaxial strain does not surpass the ETC for 1% uniaxial strain. This indicates that while biaxial strain provides significant enhancements, there is a threshold effect that limits these increases to levels below the next higher uniaxial strain value. This suggests a nonlinear relationship between the strain magnitude and the thermal conductivity enhancement, emphasizing the need to carefully consider the type and magnitude of strain applied to achieve desired thermal properties.

Furthermore, examinations of the \(\kappa _{xy}\) component under biaxial strain of 0.5%, 0.75%, and 1%, reveal substantial increases of 67%, 125%, and 215%, respectively, compared to the pristine state, as shown in Fig. 6. The pronounced effect of strain on \(\kappa _{xy}\) highlights its sensitivity to changes in the electronic structure induced by biaxial strain. This behavior is crucial for applications requiring tailored thermal conductivity in specific directions, as it provides a means to significantly alter the material’s response to thermal gradients through precise strain engineering.

By applying strains in the expressed manner, an overall increase is observed for all components under both types of strains which is demonstrated in Fig. 7. Although this behavior is uncommon, it is compatible with the results for another 2D material, Silicene90. These graphs also emphasize the appropriateness of our chosen amounts of applied strain. It is clear that the increase in ETC is consistent until around 1% in both Uniaxial and Biaxial cases; However, the figures start to take up as the applied strain escalates above 1%, leading to a swift elevation. This convinces us that the chosen percentages seem to be the best range for this case. Overall, the effects of biaxial strain are more pronounced on the xy component, following the xx component. This anisotropic response suggests that biaxial strain can be strategically used to develop materials with directionally dependent thermal properties, opening avenues for innovative applications in thermal management and thermoelectric devices.

Stark effect

Now we aim for our second perturbation, introducing a perpendicular electrical field \(E_z\) which is induced to the system from the top/bottom voltage on the surface of the material68. The schematic configuration for such setup is illustrated in Fig. 8.

This field resembles itself in the Hamiltonian in the following form68:

where \(E_z\) is the magnitude of the electric field. The matrix representation for the new Hamiltonian is

which immediately yields the electric field induced dispersion energy by

therefore, the band structure evidently changes with \(E_z\) and subsequently the diagonal terms of Green’s functions, which ultimately leads to variations of ETC.

For the purpose of this section, we decided on three voltages, 35, 45 and 55 meV exerted upon the z axis of the surface. We think these values are in a fine range for our purpose due to a couple of reasons; One is the experimental considerations which do not suggest applying intense fields91, due to the sensitivity of the 2D materials which can be damaged under high voltages. Another reason arises from the innate properties of this matter. Earlier in the present work we examined the band structure and introduced m and \(\delta\) and their crucial role in the distinct features of SnTe (001). This brings us to setting the appropriate domain for applying the external electric field between 26 meV = \(\delta\) and the turning point at energy equal to \(\approx\) 75 meV = \(\sqrt{m^2 + \delta ^2}\) (see Fig. 3). Our findings, consistent with the strain section, again show an overall increase for all components of the ETC. By analyzing each component, exhibited in Fig. 9, we deduce that \(\kappa _{xx}\) goes through the most transformation, reaching ETCs up to 14.367 Wm\(^{-1}\)K\(^{-1}\) for \(E_z\) = 55 meV, 10.587 Wm\(^{-1}\)K\(^{-1}\) for \(E_z\) = 45 meV and 7.297 Wm\(^{-1}\)K\(^{-1}\) for \(E_z\) = 35 meV at the peak (T = 190 K). The peak ETC values for the yy (xy) component are 0.068 (2.621), 0.063 (1.967), and finally 0.059 (1.592) Wm\(^{-1}\)K\(^{-1}\), respectively. Delving into the data, we observe a homogeneous rate, indicating that the increase is relative to the magnitude of the electric field. \(\kappa _{yy}\) seems to experience the least effects under this perturbation, similar to its contribution to the total ETC.

ETC of SnTe (001) vs. temperature under induction of three different intensities of external electric field for (a) xx, (b) xy and (c) yy components. The solid blue line represents the pristine case, the dash-dotted green line shows the 35 meV electric field, the dotted purple line denotes 45 meV and the dashed red line corresponds to 55 meV electric field.

To better understand the impact of the induced electric field on the ETC analyzed in this section, in Fig. 10 we have represented each component of the ETC with respect to the electric field (ranging from zero to 0.08 eV) at room temperature (300 K), which distinctly illustrates the trend of escalating modifications in conductivity as a function of varying field intensities.

Conclusions

In this research, we have made a novel contribution to the existing literature by exploring the ETC of the topological crystalline insulator SnTe (001) in pristine condition and in response to physical and electrical perturbations, namely uniaxial and biaxial strains and an external electric field (Stark effect). Our theoretical approach consists of low-energy \(\overrightarrow{\text {k}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\text {p}}\) theory and Green’s function techniques, as well as the Kubo-Greenwood approach, which allowed for a detailed analysis of the electronic properties and transport behaviors of the system. Our findings reveal that SnTe (001) exhibits significant anisotropy in ETC, with the largest contribution from the xx component. This anisotropy is the result of the intrinsic different group velocities of fermions in each direction. When subjected to external perturbations, notable variations in ETC appear. In the case of uniaxial and biaxial strains, the ETC gets an overall enhancement, which can be attributed to modifications in the band structure and therefore changes in the electronic DOS and Green’s functions. Applying the external electric field, similarly, increases the ETC in all components except the yy component, but with a more modest intensity. Although \(\kappa _{yy}\) increases, it shows a much weaker response which can be considered as an advantage in specific applications. This indicates that the ETC in SnTe (001) is highly tunable through the adjustment of external fields, making it a promising candidate for applications where controlled thermal transport is desired. In general, we discovered that strain engineering yields more variations in ETC relative to induction of an electric field. Our results underscore the potential of SnTe (001) and similar TCIs for advanced thermal management in nanoscale devices. The ability to tune the ETC by application of strain and electric fields offers significant advantages for the development of next-generation low-energy electronic and spintronic devices. Future research could focus on experimental validation of these theoretical predictions and explore the implications of these findings for practical device applications.

In summary, the current study demonstrates that SnTe (001) holds promise not only as a robust topological crystalline insulator with tunable electronic properties but also as an efficient material for managing heat in electronic applications.

Additional information

It is worth taking another look at the symmetry of the (001) surface for a better understanding of the physics at the lattice scale. See that the X points remain invariant when subjected to the time-reversal transformation plus three specific group operations: (i) The x-coordinate reflection to -x (M\(_x\)); (ii) The y-coordinate reflection to -y (M\(_y\)); and (iii) \(\pi\) rotation around the surface normal (\(C_2\)). One can identify these symmetries by scrutinizing the right side of Fig. 1150.

To enhance understanding of the roles of the off-diagonal parameters m and \(\delta\) within the context of the band structure, three potential scenarios are examined below:

(i) \(\delta = 0\) meV and \(m = 0\) meV, (ii) \(\delta = 0\) meV and \(m = 70\) meV, and (iii) \(\delta = 26\) meV and \(m = 0\) meV. (i): According to Eq. (4), the dispersion relation takes the form \(\mathcal {E}_\mu (\overrightarrow{k}) = \mu \sqrt{\eta _x^2 k_x^2 + \eta _y^2 k_y^2}\) in which the surface states exhibit doubly degenerate conduction and valence bands, depicted in top middle part of the Figure. (ii) Conversely, if \(\delta = 0\) and \(m = 70\) meV, the dispersion relation \(\mathcal {E}_{\mu \nu }(\overrightarrow{k}) = \mu (m + \nu \sqrt{\eta _x^2 k_x^2 + \eta _y^2 k_y^2})\) applies. This results in linear energy states at point \(X_1\) with energies \(\pm m\), as shown in the bottom right. Here, the lower conduction band and the upper valence band intersect at zero energy \(\mathcal {E}(\overrightarrow{k}) = 0\), defined by \(m^2 = \eta _x^2 k_x^2 + \eta _y^2 k_y^2\). The topological characteristics of the crystalline tin telluride topological insulator stem from this inverted bulk gap, due to the spin-orbit interaction. (iii) In the final case, as illustrated in the bottom left, where \(\delta = 26\) meV and \(m = 0\) meV, the surface band structure is given by the dispersion relation \(\mathcal {E}_{\mu \nu }(\overrightarrow{k}) = \mu \sqrt{(\eta _x^2 k_x^2 + \delta + \nu \eta _y k_y)^2 }\), resulting in two Dirac cones at zero energy with momenta \(k_x = \pm \delta / \eta _x\) and \(k_y = \pm \delta / \eta _y\) along the X\(_1\) and X\(_2\) directions. These behaviors clearly demonstrate the crucial role of the parameters m and \(\delta\) in achieving the distinctive features of the (001) surface states.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.82.3045 (2010).

Ando, Y. Topological insulator materials. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 102001. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSJ.82.102001 (2013).

Wojek, B. M. et al. Direct observation and temperature control of the surface Dirac gap in a topological crystalline insulator. Nat. Commun. 6, 8463. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9463 (2015).

Bansil, A., Lin, H. & Das, T. Colloquium: Topological band theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 021004. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.88.021004 (2016).

Li, Q., Mo, S.-K. & Edmonds, M. T. Recent progress of MnBi\(_2\)Te\(_4\) epitaxial thin films as a platform for realising the quantum anomalous Hall effect. Nanoscale 16, 14247–14260. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NR00194J (2024).

Wang, J. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological states of condensed matter. Nat. Mater. 16, 1062–1067. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat5012 (2017).

Wen, X.-G. Colloquium: Zoo of quantum-topological phases of matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 041004. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.89.041004 (2017).

Moore, J. E. The birth of topological insulators. Nature 464, 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08916 (2010).

Götte, M., Joppe, M. & Dahm, T. Pure spin current devices based on ferromagnetic topological insulators. Sci. Rep. 6, 36070. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36070 (2016).

Dziawa, P. et al. Topological crystalline insulator states in Pb\(_{1-\text{ x }}\)Sn\(_\text{ x }\)Se. Nat. Mater. 11, 1023–1027. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3449 (2012).

Fu, L. Topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 106802. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.106802 (2011).

Hsieh, T. H. et al. Topological crystalline insulators in the SnTe material class. Nat. Commun. 3, 982. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1969 (2012).

Huang, S.-M., Yan, Y.-J., Yu, S.-H. & Chou, M. Thickness-dependent conductance in Sb\(_2\)SeTe\(_2\) topological insulator nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 7, 1896. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02102-7 (2017).

Roychowdhury, S., Shenoy, U. S., Waghmare, U. V. & Biswas, K. Tailoring of electronic structure and thermoelectric properties of a topological crystalline insulator by chemical doping. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 15241–15245. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201508492 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Routes for advancing SnTe thermoelectrics. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 16790–16813. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0TA05458E (2020).

Tanaka, Y. et al. Experimental realization of a topological crystalline insulator in SnTe. Nat. Phys. 8, 800–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys2442 (2012).

Schönle, J. et al. Field-tunable 0-\(\pi\)-transitions in SnTe topological crystalline insulator squids. Sci. Rep. 9, 1987. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-38008-1 (2019).

Pandey, A. et al. High performing flexible optoelectronic devices using thin films of topological insulator. Sci. Rep. 11, 832. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80738-8 (2021).

Jin, K.-H., Jiang, W., Sethi, G. & Liu, F. Topological quantum devices: A review. Nanoscale 15, 12787–12817. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3NR01288C (2023).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Z\(_{2}\) topological order and the quantum spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 146802. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.146802 (2005).

Ando, Y. & Fu, L. Topological crystalline insulators and topological superconductors: From concepts to materials. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 6, 361–381. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-031214-014501 (2015).

Sato, M. & Ando, Y. Topological superconductors: A review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 076501. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6633/aa6ac7 (2017).

Lahiri, S. & Basu, S. Second order topology in a band engineered Chern insulator. Sci. Rep. 14, 1880. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52321-y (2024).

Armitage, N. P., Mele, E. J. & Vishwanath, A. Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.90.015001 (2018).

Soluyanov, A. A. et al. Type-II Weyl semimetals. Nature 527, 495–498. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15768 (2015).

Jiang, W. et al. A topological nodal line semi-metal with a negative Poisson’s ratio in a three-dimensional carbon network with sp\(^2\) hybridization. Nanoscale 16, 13543–13550. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4NR01298D (2024).

Bernevig, A., Weng, H., Fang, Z. & Dai, X. Recent progress in the study of topological semimetals. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 041001. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSJ.87.041001 (2018).

Banik, A., Roychowdhury, S. & Biswas, K. The journey of tin chalcogenides towards high-performance thermoelectrics and topological materials. Chem. Commun. 54, 6573–6590. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CC02230E (2018).

Kane, C. L. & Mele, E. J. Quantum spin Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 226801. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.226801 (2005).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Materials 1, 011002. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4812323 (2013).

Sulich, A. et al. Unit cell distortion and surface morphology diversification in a SnTe/CdTe (001) topological crystalline insulator heterostructure: influence of defect azimuthal distribution. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 3139–3152. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TC05733B (2022).

Li, F. et al. Rare three-valence-band convergence leading to ultrahigh thermoelectric performance in all-scale hierarchical cubic SnTe. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3EE02482B (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Spin-filtered edge states with an electrically tunable gap in a two-dimensional topological crystalline insulator. Nat. Mater. 13, 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3828 (2014).

Wang, X., Du, Y., Dou, S. & Zhang, C. Room temperature giant and linear magnetoresistance in topological insulator Bi\(_{2}\)Te\(_{3}\) nanosheets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 266806. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.266806 (2012).

Wang, Z., Qiu, R. L. J., Lee, C. H., Zhang, Z. & Gao, X. P. A. Ambipolar surface conduction in ternary topological insulator Bi\(_2\)(Te\(_{1-\text{ x }}\)Se\(_\text{ x }\))\(_3\) nanoribbons. ACS Nano 7, 2126–2131. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn304684b (2013).

Xiao, G. et al. Unexpected room-temperature ferromagnetism in nanostructured Bi\(_2\)Te\(_3\). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 729–733. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201309416 (2014).

Mong, R. S. K., Essin, A. M. & Moore, J. E. Antiferromagnetic topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 81, 245209. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.81.245209 (2010).

Zhou, X. et al. Topological crystalline insulator states in the Ca\(_2\)As family. Phys. Rev. B 98, 241104. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.98.241104 (2018).

Tang, F., Po, H. C., Vishwanath, A. & Wan, X. Comprehensive search for topological materials using symmetry indicators. Nature 566, 486–489. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0937-5 (2019).

Teo, J. C. Y., Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Surface states and topological invariants in three-dimensional topological insulators: Application to Bi\(_{1-\text{ x }}\)Sb\(_\text{ x }\). Phys. Rev. B 78, 045426. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.78.045426 (2008).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Observation of a topological crystalline insulator phase and topological phase transition in Pb\(_{1-\text{ x }}\)Sn\(_\text{ x }\)Te. Nat. Commun. 3, 1192. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2191 (2012).

Yan, C.-H. et al. Growth of topological crystalline insulator SnTe thin films on Si (111) substrate by molecular beam epitaxy. Surf. Sci. 621, 104–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susc.2013.11.004 (2014).

Taskin, A. A., Yang, F., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Topological surface transport in epitaxial SnTe thin films grown on Bi\(_2\)Te\(_3\). Phys. Rev. B 89, 121302. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.89.121302 (2014).

Nadj-Perge, S., Drozdov, I. K., Bernevig, B. A. & Yazdani, A. Proposal for realizing Majorana fermions in chains of magnetic atoms on a superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 88, 020407. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.88.020407 (2013).

Zhang, J., Ji, W.-X., Zhang, C.-W., Li, P. & Wang, P.-J. Nontrivial topology and topological phase transition in two-dimensional monolayer Tl. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 24790–24795. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CP02649A (2018).

Zhang, R.-W. et al. Ethynyl-functionalized stanene film: A promising candidate as large-gap quantum spin Hall insulator. New J. Phys. 17, 083036. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/17/8/083036 (2015).

Zhang, H., Lu, L., Meng, W., Cheng, S.-D. & Mi, S.-B. Nanoscale fabrication of heterostructures in thermoelectric SnTe. Nanoscale 16, 2303–2309. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3NR04646J (2024).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.83.1057 (2011).

Tang, E. & Fu, L. Strain-induced partially flat band, helical snake states and interface superconductivity in topological crystalline insulators. Nat. Phys. 10, 964–969. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys3109 (2014).

Liu, J., Duan, W. & Fu, L. Two types of surface states in topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. B 88, 241303. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.88.241303 (2013).

Korenman, V. & Drew, H. D. Subbands in the gap in inverted-band semiconductor quantum wells. Phys. Rev. B 35, 6446–6449. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.35.6446 (1987).

Li, Y. et al. Promising thermoelectric properties and anisotropic electrical and thermal transport of monolayer SnTe. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 083901. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5085255 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Evolutional carrier mobility and power factor of two-dimensional tin telluride due to quantum size effects. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 4181–4191. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9TC06611J (2020).

Pandit, A., Haleoot, R. & Hamad, B. Thermal conductivity and enhanced thermoelectric performance of SnTe bilayer. J. Mater. Sci. 56, 10424–10437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-021-05926-x (2021).

Zhu, J., Fan, X., Zhang, K., Zhou, J. & Tang, D. Thermoelectric performance of SnTe nano-films depending on thickness, doping concentration and temperature. Mater. Res. Lett. 12, 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/21663831.2024.2307372 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of SnTe thin film through designing oriented nanopillar structure. J. Alloys Compds. 737, 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.12.011 (2018).

Li, J. Q. et al. Enhancement of thermoelectric properties in SnTe with (Ag, In) co-doping. J. Electron. Mater. 47, 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-017-5745-9 (2018).

Pathak, R., Sarkar, D. & Biswas, K. Enhanced band convergence and ultra-low thermal conductivity lead to high thermoelectric performance in SnTe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 17686–17692. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202105953 (2021).

Banik, A. & Biswas, K. Lead-free thermoelectrics: Promising thermoelectric performance in p-type SnTe\(_{1-\text{ x }}\)Se\(_\text{ x }\) system. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 9620–9625. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA01333F (2014).

Banik, A., Shenoy, U. S., Saha, S., Waghmare, U. V. & Biswas, K. High power factor and enhanced thermoelectric performance of SnTe-AgInTe\(_2\): Synergistic effect of resonance level and valence band convergence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13068–13075. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b08382 (2016).

Ezawa, M. Magnetic-field induced semimetal in topological crystalline insulator thin films. Phys. Lett. A 379, 1183–1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2015.02.028 (2015).

Mahan, G. D. Many-Particle Physics (Springer, 2000).

Grosso, G. & Parravicini, G. P. Solid State Physics (Academic Press, 2000).

Kubo, R. Statistical-mechanical theory of irreversible processes. I. General theory and simple applications to magnetic and conduction problems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 12, 570–586. https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.12.570 (1957).

Greenwood, D. A. The Boltzmann equation in the theory of electrical conduction in metals. Proc. Phys. Soc. 71, 585. https://doi.org/10.1088/0370-1328/71/4/306 (1958).

Rickayzen, G. Green’s Functions and Condensed Matter. Dover Books on Physics (Dover Publications, 2013).

Walkup, D. et al. Interplay of orbital effects and nanoscale strain in topological crystalline insulators. Nat. Commun. 9, 1550. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03887-5 (2018).

Ezawa, M. Electrically tunable conductance and edge modes in topological crystalline insulator thin films: minimal tight-binding model analysis. New J. Phys. 16, 065015. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/16/6/065015 (2014).

Wojciechowski, K. T., Parashchuk, T., Wiendlocha, B., Cherniushok, O. & Dashevsky, Z. Highly efficient n-type PbTe developed by advanced electronic structure engineering. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 13270–13285. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0TC03067H (2020).

Shen, J. & Cha, J. J. Topological crystalline insulator nanostructures. Nanoscale 6, 14133–14140. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4NR05124F (2014).

Mitchell, D. L. & Wallis, R. F. Theoretical energy-band parameters for the lead salts. Phys. Rev. 151, 581–595. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.151.581 (1966).

Lent, C. S. et al. Relativistic empirical tight-binding theory of the energy bands of GeTe, SnTe, PbTe, PbSe, PbS, and their alloys. Superlatt. Microstruct. 2, 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-6036(86)90017-0 (1986).

Fang, C., Gilbert, M. J. & Bernevig, B. A. Topological insulators with commensurate antiferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085406. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.88.085406 (2013).

Jiang, J.-H. & Imry, Y. Enhancing thermoelectric performance using nonlinear transport effects. Phys. Rev. Appl. 7, 064001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.7.064001 (2017).

Shapiro, D. S., Feldman, D. E., Mirlin, A. D. & Shnirman, A. Thermoelectric transport in junctions of Majorana and Dirac channels. Phys. Rev. B 95, 195425. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.95.195425 (2017).

Vining, C. B. An inconvenient truth about thermoelectrics. Nat. Mater. 8, 83–85. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2361 (2009).

Brebrick, R. F. & Strauss, A. J. Anomalous thermoelectric power as evidence for two-valence bands in SnTe. Phys. Rev. 131, 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.131.104 (1963).

Roychowdhury, S., Sandhya Shenoy, U., Waghmare, U. V. & Biswas, K. Effect of potassium doping on electronic structure and thermoelectric properties of topological crystalline insulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 193901. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4948969 (2016).

Huang, B.-L. & Kaviany, M. Ab initio and molecular dynamics predictions for electron and phonon transport in bismuth telluride. Phys. Rev. B 77, 125209. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.77.125209 (2008).

Rameshti, B. Z. & Asgari, R. Thermoelectric effects in topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. B 94, 205401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.94.205401 (2016).

Xu, E. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric properties of topological crystalline insulator PbSnTe nanowires grown by vapor transport. Nano Res. 9, 820–830. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-015-0961-1 (2016).

Madon, B. et al. Anomalous and planar Righi-Leduc effects in Ni\(_{80}\)Fe\(_{20}\) ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 94, 144423. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.94.144423 (2016).

Li, X. et al. Anomalous Nernst and Righi-Leduc effects in Mn\(_3\)Sn: Berry curvature and entropy flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 056601. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.056601 (2017).

Ginting, D. et al. Enhancement of thermoelectric performance via weak disordering of topological crystalline insulators and band convergence by Se alloying in Pb\(_{0.5}\)Sn\(_{0.5}\)Te\(_{1-\text{ x }}\)Se\(_\text{ x }\). J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 5870–5879. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8TA00381E (2018).

Ginting, D. et al. Thermoelectric properties and chemical potential tuning by K- and Se-coalloying in (Pb\(_{0.5}\)Sn\(_{0.5}\))\(_{1-\text{ x }}\)K\(_\text{ x }\)Te\(_{0.95}\)Se\(_{0.05}\). Electron. Mater. Lett. 15, 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13391-019-00130-1 (2019).

Pandit, A. & Hamad, B. Thermoelectric and lattice dynamics properties of layered MX (M = Sn, Pb; X = S, Te) compounds. Appl. Surf. Sci. 538, 147911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147911 (2021).

Ding, G., Gao, G. & Yao, K. High-efficient thermoelectric materials: The case of orthorhombic IV-VI compounds. Sci. Rep. 5, 9567. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09567 (2015).

Miao, M. S. et al. Polarization-driven topological insulator transition in a GaN/ InN/ GaN quantum well. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 186803. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.186803 (2012).

Qian, X., Fu, L. & Li, J. Topological crystalline insulator nanomembrane with strain-tunable band gap. Nano Res. 8, 967–979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-014-0578-9 (2015).

Xie, H. et al. Large tunability of lattice thermal conductivity of monolayer silicene via mechanical strain. Phys. Rev. B 93, 075404. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.93.075404 (2016).

Zhang, T., Ha, J., Levy, N., Kuk, Y. & Stroscio, J. Electric-field tuning of the surface band structure of topological insulator Sb\(_{2}\)Te\(_{3}\) thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 056803. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.056803 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Research Council of Amirkabir University of Technology for its support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M. and M.E worked out the theoretical methods, E.G. conducted the analytical and computational calculations, and E.G. and F.M. analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The first corresponding author is responsible for submitting a http://www.nature.com/srep/policies/index.html#competingcompeting interests statement on behalf of all authors of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gholami, E., Mohammadi, F., Ebrahimi, M. et al. Impact of electric field and strain on the electronic thermal conductivity of topological crystalline insulator SnTe (001). Sci Rep 15, 21665 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06357-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06357-3