Abstract

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) harness electroencephalographic signals for direct neural control of devices, offering significant benefits for individuals with motor impairments. Traditional machine learning methods for EEG-based motor imagery (MI) classification encounter challenges such as manual feature extraction and susceptibility to noise. This paper introduces EEGEncoder, a deep learning framework that employs modified transformers and Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) to surmount these limitations. We propose a novel fusion architecture, named Dual-Stream Temporal-Spatial Block (DSTS), to capture temporal and spatial features, improving the accuracy of Motor Imagery classification task. Additionally, we use multiple parallel structures to enhance the model’s performance. When tested on the BCI Competition IV-2a dataset, our proposed model achieved an average accuracy of 86.46% for subject dependent and average 74.48% for subject independent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) represent an emerging technological field, offering an innovative approach to human-computer interaction. By enabling direct neural communication, BCIs allow individuals to control external devices or systems solely through brain activity, bypassing traditional motor pathways. BCIs hold significant promise for applications in healthcare, rehabilitation, entertainment, and education. In the medical sector, they provide hope for individuals with motor impairments, enabling the restoration of control over bodily functions. For instance, BCIs have been crucial in helping individuals with spinal cord injuries operate prosthetic limbs and have supported stroke survivors in regaining mobility1,2.

A critical BCI modality is EEG-based motor imagery (MI), which utilizes electroencephalographic (EEG) signals to deduce a user’s intent for limb movement. MI signals, which are the brain’s response to the mental rehearsal of motor actions, are essential for a BCI to identify the intended limb movement and control external devices accordingly.

Researchers have traditionally relied on pattern recognition and machine learning methods, using handcrafted features to classify EEG data. These approaches have proven highly effective, enabling the development of communication aids for stroke and epilepsy patients, brainwave-controlled devices like wheelchairs and robots for individuals with mobility impairments, and remote pathology detection systems based on EEG3,4,5. Despite these advancements, creating effective BCI systems remains a significant challenge. The limited spatial resolution, low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and dynamic nature of MI signals complicate the extraction of reliable features. Additionally, the substantial inherent noise in EEG data adds another layer of complexity to the analysis of brain dynamics and the precise classification of EEG signals.

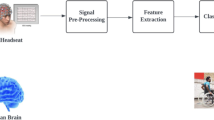

Traditional BCIs generally encompass five main processing stages: data acquisition, signal processing, feature extraction, classification, and feedback6. Each stage often relies on manually specified signal processing7, feature extraction8, and classification methods9, requiring significant expertise and prior knowledge of the expected EEG signals. For instance, preprocessing steps are typically tailored to specific EEG features of interest, such as band-pass filtering for certain frequency ranges, which might exclude other potentially relevant EEG features outside the band-pass range. As BCI technology expands into new application areas, the demand for robust feature extraction techniques continues to grow10,11,12,13.

Early research in EEG signal classification has significantly contributed to our understanding of MI and other cognitive tasks. For example, the study on the classification of MI BCI using multivariate empirical mode decomposition (MEMD) demonstrated the effectiveness of MEMD in dealing with data nonstationarity, low SNR, and closely spaced frequency bands of interest. This approach allows for enhanced localization of frequency information in EEG, providing a highly localized time-frequency representation14. Another study focused on emotional state classification from EEG data using machine learning approaches, highlighting the importance of power spectrum features and feature smoothing methods in improving classification accuracy15. Additionally, research on mu rhythm (de)synchronization and EEG single-trial classification illustrated the importance of event-related desynchronization (ERD) and synchronization (ERS) patterns in discriminating between different MI tasks16.

These early studies have laid a solid foundation for the field, deepening our understanding of EEG signals and MI classification. The insights gained from these traditional methods have significantly influenced the development of subsequent technologies, which continue to benefit from the robust feature extraction techniques and classification strategies established by prior research. As a result, contemporary models are better equipped to handle the complexities of EEG data, leveraging the advancements made by earlier studies to achieve improved performance in various BCI applications.

In recent years, BCI technology has gained significant attention in the classification of MI tasks. Traditional MI classification methods mainly rely on manual feature extraction and machine learning algorithms. While these methods have achieved some success, they also have certain limitations, such as the cumbersome feature extraction process and the high demand for domain expertise17,18,19. The advent of deep learning has brought new possibilities for MI classification by learning discriminative features directly from raw EEG data, thereby reducing the need for manual feature extraction. Among deep learning methods, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become foundational due to their layered feature extraction capabilities and end-to-end learning potential. Various CNN architectures, such as Inception-CNN, Residual CNN, 3D-CNN, and Multi-scale CNN, have been widely applied in MI classification20,21,22,23,24,25.

In addition to CNNs, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) have been used to capture the temporal dynamics in EEG signals26,27. For instance, Kumar et al.28 proposed an LSTM model combined with FBCSP features and an SVM classifier, while Luo and Chao26 utilized FBCSP features as inputs to a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) model, which showed superior performance over LSTM.To overcome the limitations of individual models, researchers have attempted to combine different deep learning models. For example, integrating CNNs with LSTM to leverage their respective strengths23. Additionally, TCNs, a novel variant of CNNs designed for time-series modeling and classification, can exponentially expand the receptive field size by linearly increasing the number of parameters, thereby avoiding the gradient issues faced by RNNs29.

The emergence of attention mechanisms has further advanced EEG signal decoding. Since Bahdanau et al.30 introduced attention-based models, these mechanisms have been widely applied in various fields, such as Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Computer Vision (CV)30,31. Recent efforts in MI classification have begun to harness the potential of transformer models, yielding promising results24,32.

Despite the impressive capabilities of deep learning, it also faces significant challenges. For instance, RNNs, while adept at capturing temporal dynamics, are difficult to train, computationally costly, and susceptible to gradient vanishing problems. Similarly, CNNs excel in local feature extraction but may struggle with capturing global information. Transformer models, although effective with sequential data, often require large datasets to converge, posing a limitation with the typically scarce EEG data. In the realm of motor imagery (MI) classification, these challenges are compounded by the limited availability of publicly accessible EEG MI datasets, leading to overfitting in models with extensive parameter spaces2,33. Unlike more mature fields like computer vision and natural language processing, where deep learning has benefited from abundant data, EEG data presents unique hurdles such as high variability, low signal-to-noise ratio, and non-stationarity, complicating model training and generalization34. While transfer learning offers potential, the distinct characteristics of EEG signals necessitate customized approaches35,36. Thus, there is a pressing need for deep learning models specifically optimized for EEG data, alongside further research to improve data understanding and model robustness in this emerging field.

Our proposed model amalgamates the contextual processing prowess of transformers with the nuanced temporal dynamics captured by temporal convolutional networks (TCNs). This amalgamation is meticulously engineered to discern both the global and local dependencies that are characteristic of EEG signals. In our pursuit, we have also integrated cutting-edge developments from transformer architectures to bolster our model’s efficacy. Our methodology represents a concerted effort to refine the interplay between transformers and TCNs, with the objective of bolstering the robustness and precision of EEG signal classification in a systematic and empirical fashion.

Our contribution: In this paper, we introduce EEGEncoder, a novel model for EEG-based MI classification that effectively combines the temporal dynamics captured by TCNs with the advanced attention mechanisms of Transformers. This integration is further augmented by incorporating recent technical enhancements in Transformer architectures. Moreover, we have developed a new parallel structure within EEGEncoder to bolster its robustness. Our work aims to provide a robust and efficient tool to the MI classification community, thereby facilitating progress in brain-computer interface technology. Notably, our model has demonstrated outstanding performance on the BCI Competition IV dataset 2a37, highlighting its potential and effectiveness in real-world applications.

Methods

The input to the EEGEncoder model consists of segmented EEG data recorded during motor imagery tasks. These segments are preprocessed through the Downsampling Projector, which employs multiple layers of convolution to reduce the dimensionality and noise of the input signals. The processed signals are then fed into the DSTS blocks for feature extraction.

The output of the model is a classification of the EEG segments into one of several categories, which correspond to the intended movements as labeled in the training dataset. The number of categories is determined by the specific dataset used. For instance, in the BCIC IV 2a dataset, there are four categories: left hand, right hand, feet, and tongue.

The proposed EEGEncoder model, as depicted in Fig. 1, is designed to classify motor imagery (MI) EEG signals into specific movement categories. The architecture of EEGEncoder primarily consists of a Downsampling Projector and multiple parallel Dual-Stream Temporal-Spatial (DSTS) blocks. Each DSTS block integrates Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) and stable transformers to capture both temporal and spatial features of EEG signals. To enhance the model’s robustness, dropout layers are introduced before each parallel DSTS branch. The following sections provide a detailed description of the structure and function of each module.

Downsampling projector for EEG signal preprocessing

The Downsampling projector module within our EEG-based deep learning framework is designed to preprocess Motor Imagery EEG data, preparing it for intricate analysis by subsequent Transformer and Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) layers. This module adeptly reshapes high-dimensional EEG sequences, characterized by a temporal resolution of 1125 and 22 channels, into a format that is conducive to convolutional processing. The main purpose of this process is to reduce the length of the sequence by passing continuous EEG signals through simple convolutional layers and average pooling layers.

Considering the EEG data analogous to an image with dimensions (1125, 22, 1), our approach involves the application of convolutional layers to extract spatial-temporal features, while concurrently mitigating noise and reducing inter-channel latency effects.

The core architecture of the Downsampling projector, as illustrated in Fig. 2, comprises three convolutional layers. The first convolutional layer is designed to initiate the feature extraction process without the application of an activation function. In contrast, the second and third convolutional layers are each followed by a batch normalization (BN) layer and an exponential linear unit (ELU) activation layer to stabilize the learning process and introduce non-linear dynamics into the model. The ELU38 activation function is defined as:

where \(\alpha\) is a hyperparameter that defines the value to which an ELU saturates for negative net inputs.

Architecture of the Downsampling projector. The figure provides a detailed schematic of the Downsampling projector’s architecture. It includes three convolutional layers, with the second and third layers each followed by a batch normalization (BN) layer and an ELU activation layer. Additionally, two average pooling layers and two dropout layers are incorporated to foster model generalization. Specific parameters, such as the kernel size and stride for the convolutional layers, and the kernel size for the average pooling layers, are also depicted. For example, ”Conv 1x16, (64,1)” signifies a convolutional layer transitioning from an input channel depth of 1 to an output channel depth of 16, with a stride of 64 along the width and 1 along the height of the input feature map.

The second convolutional layer employs filters of size (1, 22) to compress the channel dimension, effectively encoding channel-wise information into a singular spatial dimension. This strategic choice is informed by the understanding that variations among EEG channels are generally subtle and often predominantly due to noise.

Following this, average pooling layers with a stride of 7 are applied to reduce the temporal dimension. Interspersed dropout layers serve to promote regularization.

Stabilizing the transformer layer

In the subsequent modules, we employ a modified Transformer layer39, which has been adapted with recent technological advancements to enhance training stability and model efficacy. Here, we detail the specific alterations applied to the Transformer architecture.

Pre-normalization is a widely adopted strategy in deep learning, particularly for large-scale natural language processing (NLP) models like the Transformer. It is instrumental in stabilizing the training of very deep networks by addressing the vanishing and exploding gradient issues.

Unlike the standard Transformer architecture, where each sub-layer (such as self-attention and feed-forward layers) is succeeded by a residual connection and layer normalization (post-normalization), pre-normalization involves applying LayerNorm before each sub-layer.

Below is the simplified pseudocode for a Transformer block utilizing pre-normalization:

The advantages of pre-normalization are manifold:

-

Enhanced Gradient Flow: By normalizing inputs prior to each layer, we mitigate the risk of gradient vanishing or exploding during backpropagation, thus enabling the training of deeper architectures.

-

Stable Training Dynamics: Normalization ensures a consistent distribution of inputs across layers, fostering stability throughout the training phase.

-

Quicker Convergence: Pre-normalization has been associated with faster convergence rates in training models.

Our approach also incorporates RMSNorm, or Root Mean Square Layer Normalization40, as the normalization function. RMSNorm diverges from traditional Layer Normalization by normalizing solely the standard deviation of activations, not the mean and standard deviation. It achieves this by dividing the activations by their root mean square, which maintains gradient scale and facilitates the training of deep networks.

Here, x represents the layer input, N is the input’s dimensionality, and \(\epsilon\) is a small constant to prevent division by zero. This equation computes the RMS of the input and normalizes it by this value.

The key benefits of RMSNorm include:

-

Reduced Computational Burden: RMSNorm obviates the need to compute the mean, thereby reducing computational demands relative to Layer Normalization.

-

Stable Training: By normalizing activation scales, RMSNorm aids in gradient flow, enhancing the overall stability of the training regimen.

-

Compatibility with Deep Networks: RMSNorm is particularly advantageous for deep networks, where it helps avert the typical gradient issues associated with such architectures.

To further enhance our model, we have substituted the typically-used ReLU activation with the Swish Gated Linear Unit (SwiGLU)41. SwiGLU is defined as the componentwise product of two linear transformations of the input, one of which is Swish-activated:

In the equation, \(x\) is the input, \(W\) and \(V\) are weight matrices, Swish42 is defined as \(x \cdot \delta (\beta x)\), where \(\delta (z) = (1 + exp(-z))^{-1}\) is the sigmoid function and \(\beta\) is either a constant or a trainable parameter. SwiGLU’s principal advantages are:

-

Computational Efficiency: The gating mechanism of SWiGLU is notably efficient.

-

Augmented Model Capacity: It empowers the model to encapsulate more complex functionalities.

-

Performance Enhancement: SWiGLU typically boosts model performance across a range of tasks.

Dual-stream temporal-spatial block

The Dual-Stream Temporal-Spatial Block (DSTS Block) , as shown in Fig. 3 presents an architecture specifically designed for the analysis of electroencephalogram (EEG) data during Motor Imagery (MI) tasks. This architecture integrates Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) with stable Transformer modules, capitalizing on their complementary strengths to capture the temporal and spatial characteristics inherent in EEG signals.

TCNs utilize causal convolutions to process time-series data, effectively capturing temporal features with a high level of detail. The convolutional approach simplifies training and enhances feature extraction, which is particularly advantageous when dealing with the noisy and redundant nature of EEG data. However, the local focus of TCNs may result in insufficient representation of global dependencies, a notable challenge when analyzing extensive EEG sequences.

In contrast, Transformers employ a global self-attention mechanism that allows for the integration of contextual information across entire sequences. This capability enables the Transformer to perceive the broader context within the data, addressing a limitation of TCNs. Nonetheless, training Transformers can be complex, especially initially, and their performance may be less than optimal with the inherently noisy and complex EEG data.

The DSTS Block is engineered to leverage the TCN’s proficiency in local feature extraction and the Transformer’s capacity for global context comprehension, thus aiming to provide a comprehensive analysis of EEG data. We also adopt the relative position representations as proposed by Shaw et al. in their seminal work43. This dual-stream approach is anticipated to improve the model’s ability to identify patterns relevant to MI tasks by enhancing its analytical complexity.

EEG data is processed through two distinct yet parallel pathways within the DSTS Block:

-

The TCN pathway focuses on extracting local temporal features (\(H_{\text {temporal}}\)), utilizing causal convolutions to prioritize recent inputs and maintain temporal continuity.

-

The Transformer pathway is dedicated to identifying global spatial relationships (\(H_{\text {spatial}}\)), applying self-attention to consider inputs across the full sequence for a holistic spatial analysis.

To preserve the temporal sequence of EEG signals, a causal mask is integrated into the stable Transformer, ensuring information flow remains unidirectional. This approach is essential for maintaining the sequence’s integrity, as it guarantees that predictions are based solely on past and present data:

The variables \(H_{\text {temporal}}^{\prime }\) and \(H_{\text {spatial}}^{\prime }\) denote the final hidden states from the TCN and stable Transformer pathways, respectively, extracted from the last element in the sequence dimension. This selection strategy captures the accumulated temporal and spatial information up to the current moment.

These final hidden states are then integrated to create a composite feature representation, which is processed by a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) for the classification task:

The integration of TCN and Transformer pathways within the DSTS Block is designed to balance their respective strengths and limitations, enhancing the robustness and precision of BCI applications.

EEG signal classification with EEGEncoder

The EEGEncoder architecture represents a novel approach to the classification of electroencephalogram (EEG) signals. Traditional methodologies in this domain have frequently employed moving window techniques to extract temporal features from EEG data. These methods involve slicing the EEG sequence into overlapping temporal windows, which are then fed into the model to capture the dynamic aspects of the signal.

However, our architecture departs from this convention by harnessing the Transformer’s intrinsic capability to contextualize data across the entire sequence. We postulate that this feature of the Transformer reduces the dependency on moving window slicing, thereby preserving the continuity and integrity of the temporal sequence.

To introduce variability and enhance the robustness of the model, we incorporate multiple parallel dropout layers. These layers independently introduce perturbations to the hidden states of the EEG sequence, a strategy designed to improve the model’s performance by simulating a form of ensemble learning within the architecture itself.

After extensive experimentation and comparative analysis, we have optimized the EEGEncoder by configuring the DSTS block with a stable transformer consisting of four layers and two attention heads. Additionally, we have integrated five parallel branches, each comprising a dropout layer followed by a DSTS block. This configuration was determined to strike an optimal balance between model complexity and performance, leading to improvements in classification accuracy and generalizability.

Results

In this section, we provide a detailed evaluation of the EEGEncoder model, demonstrating its classification capabilities on the BCI Competition IV 2a dataset37. We compare the performance of our model with various established models to underscore its effectiveness in decoding the complex patterns inherent in EEG signals for motor imagery tasks. The subsequent subsections elaborate on the model’s performance metrics, a comparative analysis with other models, and discuss the significance of these results for the progression of brain-computer interface technologies.

Dataset

In our study, we primarily utilized the BCI Competition IV dataset 2a (BCI-2a) for training and evaluating the EEGEncoder model. The BCI-2a dataset comprises recordings from nine healthy subjects, each performing four different motor imagery (MI) tasks: left hand (class 1), right hand (class 2), feet (class 3), and tongue (class 4) movements.

Each subject participated in two sessions recorded on different days. Each session consisted of six runs, with each run containing 48 trials (12 trials per MI task), resulting in a total of 288 trials per session. The EEG signals were recorded using 22 Ag/AgCl electrodes at a sampling rate of 250 Hz. The signals were bandpass filtered between 0.5 Hz and 100 Hz, and a 50 Hz notch filter was applied to reduce power line interference.

At the beginning of each session, a recording of approximately 5 minutes was performed to estimate the EOG influence, divided into three blocks: two minutes with eyes open, one minute with eyes closed, and one minute with eye movements. Due to technical problems, the EOG block for subject A04T contains only the eye movement condition.

During the experiments, subjects were seated in a comfortable armchair in front of a computer screen. Each trial began with a fixation cross appearing on a black screen, accompanied by a short acoustic warning tone. Two seconds later, a cue in the form of an arrow (pointing left, right, down, or up) appeared for 1.25 seconds, prompting the subject to perform the corresponding motor imagery task until the fixation cross disappeared at six seconds.

For our research, one session was used for model training, while the other was reserved for evaluation testing. The raw MI EEG signals from all bands and channels were fed into the model in the form of a \(C \times T\) two-dimensional matrix. Minimal preprocessing was applied to the raw data, employing a standard scaler to normalize the signals to have zero mean and unit variance.

Our research concentrates on the BCI-2a dataset due to its increased complexity and the greater challenge it presents, which better demonstrates the performance capabilities of our model. The dataset is well-documented and has been extensively used in the BCI community, ensuring its reliability and relevance for evaluating EEG classification models.

Certainly, here’s the revised section with the inclusion of Information Transfer Rate (ITR) as a new metric:

Performance metrics

To evaluate the performance of the EEGEncoder, we employ three key metrics: accuracy, Cohen’s kappa, and ITR. These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s classification capabilities.

Accuracy (Acc) is calculated as follows:

where n is the number of categories, \(TP_i\) represents the true positive count for class i, and \(I_i\) is the total number of samples in class i. Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified samples, offering a straightforward evaluation of the model’s overall performance.

Cohen’s kappa (Kappa) is computed using the formula:

where \(P_a\) denotes the actual percentage of agreement, and \(P_e\) represents the expected percentage of agreement by chance. Kappa is particularly important for this task as it adjusts for chance agreement, providing a more reliable measure of the model’s performance, especially in scenarios with imbalanced class distributions.

Information Transfer Rate (ITR) is another crucial metric in the field of BCI, as it quantifies the speed and efficiency of information transmission from the brain to the computer. ITR is calculated using the formula:

where T is the average time in seconds per trial, N is the number of possible targets or classes, and P is the classification accuracy. ITR is measured in bits per minute (bits/min) and provides an insight into how efficiently the system can convert brain signals into actionable commands.

Accuracy and Cohen’s kappa are standard metrics for evaluating the performance of classification tasks. Accuracy provides a direct measure of the model’s ability to correctly classify EEG segments and is typically expressed as a percentage. However, in datasets with imbalanced classes, relying solely on accuracy may not be sufficient. Cohen’s kappa addresses this issue by accounting for the possibility of chance agreement, offering a more reliable evaluation metric. Kappa is represented as a decimal ranging from 0 to 1.

ITR is particularly important in the BCI domain as it not only considers the accuracy but also the speed of communication, making it a vital metric for practical applications where both precision and efficiency are critical. By incorporating ITR, we ensure that our evaluation captures the real-world usability of the EEGEncoder in BCI applications.

This dual evaluation approach, now augmented with ITR, ensures a comprehensive assessment of the model’s effectiveness, reliability, and efficiency in classifying MI-EEG signals. Additionally, these metrics are commonly used in similar studies, making them suitable for our evaluation.

Training configuration

The model is trained with a specific set of parameters, as outlined in Table 1.

The CrossEntropyLoss function is employed with label smoothing, which is set to a value of 0.1 to soften the target distributions, potentially improving the generalization of the model. To further regularize the training process and prevent overfitting, a dropout ratio of 0.3 is applied across the network, and weight decay with a coefficient of 0.5 is applied to all MLP layers.

Results on BCI IV 2a dataset

The EEGEncoder model underwent a comprehensive evaluation using the BCI Competition IV dataset 2a. Performance was assessed across three key metrics: accuracy, Cohen’s kappa, and ITR. We compared EEGEncoder with four state-of-the-art models: ATCNet, TCNetFusion, EEGTCNet, and D-ACTNet. To ensure the robustness and reliability of the results, we conducted experiments with five distinct random seeds. Each model was trained and tested under identical experimental settings, and the average results from these five iterations were reported.

It is important to note that while we reimplemented ATCNet, TCNetFusion, and EEGTCNet using the official implementations provided by Altaheri et al.32, the source code for D-ACTNet was not available. Consequently, we used the average performance metrics reported in the D-ACTNet paper as a basis for comparison. Due to this limitation, we did not compute ITR for D-ACTNet. The classification results for all nine subjects, along with detailed comparisons across models, are presented in Table 2

In terms of accuracy and Cohen’s kappa metrics, the EEGEncoder outperformed the comparative models in eight out of nine subjects, with the exception of subject 4. The model demonstrated particularly significant performance improvements in subjects 2 and 5, highlighting its enhanced ability to manage the EEG signal variations observed in these individuals.

In terms of ITR comparison, the EEGEncoder model outperforms other models. ITR primarily evaluates the model’s prediction accuracy and speed, and we attribute EEGEncoder’s advantages to three main factors. First, the architecture of EEGEncoder significantly compresses sequential information at its base, allowing for four layers of transformers without introducing excessive complexity. Second, the optimizations in PyTorch accelerate the computation of attention mechanisms, enhancing overall model efficiency. Finally, the use of Stable Transformers, which are faster and consume less memory compared to traditional transformers, contributes to quicker predictions. Consequently, EEGEncoder demonstrates superior speed alongside its already impressive accuracy when compared to other models.

The results indicate that the EEGEncoder not only excels in overall performance but also shows resilience in subjects where other models tend to falter. This resilience could be attributed to the model’s architecture, which may be more adept at capturing the nuances of EEG signals across diverse cognitive tasks. However, further studies are warranted to confirm these findings and to explore the full potential of EEGEncoder in real-world BCI applications.

Ablation study

To validate the efficacy of the various enhancements applied to the EEGEncoder, we conducted a series of ablation experiments. We began by consolidating the data from all nine subjects, merging their respective training and testing sets into single, comprehensive datasets. This approach allowed us to more effectively evaluate the generalizability of the model’s improvements across different subjects.

Here, we present a selection of key experiments that were instrumental in assessing the impact of specific modifications. These experiments included removing the transformer component from the DSTS block, using 5 shift windows instead of five dropout branches, varying the number of transformer layers, adjusting the quantity of DSTS branches within the EEGEncoder, and comparing the performance of our modified stable transformer against the Vanilla Transformer. To ensure the statistical significance of our results, we averaged the outcomes across five iterations, each initialized with a different random seed. The summarized results are displayed in Table 3.

The data in Table 3 illustrates the impact of each modification on the EEGEncoder’s performance. The removal of the transformer component led to a noticeable decrease in both accuracy and Cohen’s kappa, underscoring its contribution to the model’s effectiveness. Adjusting the number of transformer layers showed that a balance is needed to optimize performance, as evidenced by the slight decrease in accuracy with eight layers compared to two. Similarly, the number of DSTS branches was found to be a factor, with a single branch reducing performance and ten branches not improving it significantly. Lastly, the comparison between our stable transformer and the Vanilla Transformer variant indicates the importance of our modifications for achieving higher accuracy and Cohen’s kappa.

Discussion

In our research, we have innovatively designed a model based on Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN) and Transformers, specifically optimized for the classification of Motor Imagery (MI) signals derived from electroencephalograms (EEG). Our model introduces the DSTS block, a novel component that enhances the extraction of both local and global information from EEG data. By incorporating the Stable Transformer, we have stabilized the training process of the Transformer and reduced computational complexity. Furthermore, we have replaced the commonly used window shift technique with parallel multi-branch dropout+DSTS, which adds robustness and diversity to the feature extraction process.

Confusion matrices of the classification results for four models: EEGEncoder, ATCNet, TCNetFusion, and EEGTCNet. These matrices represent the average performance across nine subjects. The EEGEncoder model demonstrates superior accuracy in the ’Foot’ category compared to the other models, while the ’Tongue’ category shows relatively lower performance.

The empirical evaluation of our proposed model has yielded promising results in the BCI Competition IV dataset 2a, where we achieved commendable performance without the need for complex preprocessing-relying only on a simple standard scalar. Looking ahead, our goal is to extend the training and validation of our model across a more diverse and extensive range of datasets. We aim to incorporate cutting-edge deep learning techniques, such as pre-training, to enhance the model’s complexity and effectiveness. Ultimately, we aspire to achieve superior performance in MI classification tasks across a broader spectrum of categories, supported by larger datasets and more sophisticated model architectures.

Additionally, we computed the confusion matrices for the classification results of four models, as shown in Fig. 4. These confusion matrices were derived by averaging the performance of the models across nine subjects. From the Fig. 4, it is evident that, compared to the other three models (’ATCNet’, ’TCNetFusion’, ’EEGTCNet’), our EEGEncoder significantly outperforms in the ’Foot’ category. This superior performance in the ’Foot’ category is a key factor contributing to the overall better performance of the EEGEncoder.

However, the ’Tongue’ category exhibits the lowest performance among all categories. This lower performance might be due to the fact that the other three actions involve larger motor imagery movements of major body parts, whereas ’Tongue’ involves relatively finer and smaller movements. If more data of similar but distinct categories were available for training, it could potentially enhance the classification accuracy for the ’Tongue’ category significantly.

Moreover, the confusion matrices reveal that for the ’Right hand’ and ’Left hand’ categories, the EEGEncoder is not the best performing model among the four. Nevertheless, when considering the average performance across all four categories, the EEGEncoder exhibits the best overall performance. Additionally, the performance differences between categories are the smallest for EEGEncoder, which can be attributed to our DSTS module’s ability to extract global information and utilize multiple branches to enhance model robustness.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study is provided by the Institute for Knowledge Discovery (Laboratory of Brain-Computer Interfaces), Graz University of Technology, (Clemens Brunner, Robert Leeb, Gernot Müller-Putz, Alois Schlögl, Gert Pfurtscheller) (details here: https://bbci.de/competition/iv/desc_2a.pdf). The dataset is available at this link: https://bbci.de/competition/iv/index.html#download.

Code availability

The code used in this article are available on GitHub and can be accessed at the following link: https://github.com/BlackCattt9/EEGEncoder.

References

Ahmed, I., Jeon, G. & Piccialli, F. From artificial intelligence to explainable artificial intelligence in industry 4.0: A survey on what, how, and where. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 18, 5031–5042 (2022).

Altaheri, H. et al. Deep learning techniques for classification of electroencephalogram (eeg) motor imagery (mi) signals: A review. Neural Comput. Appl. 35, 14681–14722 (2023).

Tonin, L., Carlson, T., Leeb, R. & Millán, J. d. R. Brain-controlled telepresence robot by motor-disabled people. In 2011 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 4227–4230 (IEEE, 2011).

Hossain, M. S., Amin, S. U., Alsulaiman, M. & Muhammad, G. Applying deep learning for epilepsy seizure detection and brain mapping visualization. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. (TOMM) 15, 1–17 (2019).

Muhammad, G., Hossain, M. S. & Kumar, N. Eeg-based pathology detection for home health monitoring. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 39, 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2020.3020654 (2021).

Nicolas-Alonso, L. F. & Gomez-Gil, J. Brain computer interfaces, a review. Sensors 12, 1211–1279 (2012).

Bashashati, A., Fatourechi, M., Ward, R. K. & Birch, G. E. A survey of signal processing algorithms in brain-computer interfaces based on electrical brain signals. J. Neural Eng. 4, R32 (2007).

McFarland, D. J., Anderson, C. W., Muller, K.-R., Schlogl, A. & Krusienski, D. J. Bci meeting 2005-workshop on bci signal processing: Feature extraction and translation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 14, 135–138 (2006).

Lotte, F., Congedo, M., Lécuyer, A., Lamarche, F. & Arnaldi, B. A review of classification algorithms for eeg-based brain-computer interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 4, R1 (2007).

Lance, B. J., Kerick, S. E., Ries, A. J., Oie, K. S. & McDowell, K. Brain-computer interface technologies in the coming decades. Proc. IEEE 100, 1585–1599 (2012).

Zander, T. O. & Kothe, C. Towards passive brain-computer interfaces: Applying brain-computer interface technology to human-machine systems in general. J. Neural Eng. 8, 025005 (2011).

Blankertz, B. et al. The berlin brain-computer interface: Non-medical uses of bci technology. Front. Neurosci. 4, 198 (2010).

Gordon, S. M., Jaswa, M., Solon, A. J. & Lawhern, V. J. Real world bci: Cross-domain learning and practical applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Workshop on An Application-oriented Approach to BCI out of the laboratory, 25–28 (2017).

Park, C., Looney, D., ur Rehman, N., Ahrabian, A. & Mandic, D. P. Classification of motor imagery bci using multivariate empirical mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 21, 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2012.2229296 (2013).

Wang, X.-W., Nie, D. & Lu, B.-L. Emotional state classification from eeg data using machine learning approach. Neurocomputing 129, 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2013.06.046 (2014).

Pfurtscheller, G., Brunner, C., Schlgl, A. & Lopes da Silva, F. Mu rhythm (de)synchronization and eeg single-trial classification of different motor imagery tasks. NeuroImage 31, 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.12.003 (2006).

Xu, J., Zheng, H., Wang, J., Li, D. & Fang, X. Recognition of eeg signal motor imagery intention based on deep multi-view feature learning. Sensors 20, 3496 (2020).

Zhang, R. et al. Hybrid deep neural network using transfer learning for eeg motor imagery decoding. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 63, 102144 (2021).

Zhang, D., Chen, K., Jian, D. & Yao, L. Motor imagery classification via temporal attention cues of graph embedded eeg signals. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 24, 2570–2579 (2020).

Defferrard, M., Bresson, X. & Vandergheynst, P. Convolutional neural networks on graphs with fast localized spectral filtering. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 29 (2016).

Tabar, Y. R. & Halici, U. A novel deep learning approach for classification of eeg motor imagery signals. J. Neural Eng. 14, 016003 (2016).

Lawhern, V. J. et al. Eegnet: A compact convolutional neural network for eeg-based brain-computer interfaces. J. Neural Eng. 15, 056013 (2018).

Amin, S. U., Alsulaiman, M., Muhammad, G., Mekhtiche, M. A. & Hossain, M. S. Deep learning for eeg motor imagery classification based on multi-layer cnns feature fusion. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 101, 542–554 (2019).

Jia, Z. et al. Mmcnn: A multi-branch multi-scale convolutional neural network for motor imagery classification. In Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases: European Conference, ECML PKDD 2020, Ghent, Belgium, September 14–18, 2020, Proceedings, Part III, 736–751 (Springer, 2021).

Li, D., Xu, J., Wang, J., Fang, X. & Ji, Y. A multi-scale fusion convolutional neural network based on attention mechanism for the visualization analysis of eeg signals decoding. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 28, 2615–2626 (2020).

Luo, T.-J., Zhou, C.-L. & Chao, F. Exploring spatial-frequency-sequential relationships for motor imagery classification with recurrent neural network. BMC Bioinform. 19, 1–18 (2018).

Tang, X., Wang, T., Du, Y. & Dai, Y. Motor imagery eeg recognition with knn-based smooth auto-encoder. Artif. Intell. Med. 101, 101747 (2019).

Kumar, S., Sharma, R. & Sharma, A. Optical+: A frequency-based deep learning scheme for recognizing brain wave signals. Peerj Comput. Sci. 7, e375 (2021).

Bai, S., Kolter, J. Z. & Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.01271 (2018).

Bahdanau, D., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473 (2014).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30 (2017).

Altaheri, H., Muhammad, G. & Alsulaiman, M. Physics-informed attention temporal convolutional network for eeg-based motor imagery classification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 19, 2249–2258. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3197419 (2023).

Al-Saegh, A., Dawwd, S. A. & Abdul-Jabbar, J. M. Deep learning for motor imagery eeg-based classification: A review. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 63, 102172 (2021).

Ladda, A. M., Lebon, F. & Lotze, M. Using motor imagery practice for improving motor performance-a review. Brain Cogn. 150, 105705 (2021).

Decety, J. The neurophysiological basis of motor imagery. Behav. Brain Res. 77, 45–52 (1996).

Lotze, M. & Halsband, U. Motor imagery. J. Physiol. 99, 386–395 (2006).

Brunner, C., Leeb, R., Müller-Putz, G., Schlögl, A. & Pfurtscheller, G. Bci competition 2008–graz data set a. Institute for Knowledge Discovery (Laboratory of Brain-Computer Interfaces), Graz University of Technology 16, 1–6 (2008).

Clevert, D.-A., Unterthiner, T. & Hochreiter, S. Fast and accurate deep network learning by exponential linear units (elus). arXiv: Learning (2015).

Touvron, H. et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 (2023).

Zhang, B. & Sennrich, R. Root mean square layer normalization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (Vancouver, Canada, 2019).

Shazeer, N. Glu variants improve transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.05202 (2020).

Ramachandran, P., Zoph, B. & Le, Q. V. Searching for activation functions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.05941 (2017).

Shaw, P., Uszkoreit, J. & Vaswani, A. Self-attention with relative position representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.02155 (2018).

Musallam, Y. K. et al. Electroencephalography-based motor imagery classification using temporal convolutional network fusion. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 69, 102826 (2021).

Ingolfsson, T. M. et al. Eeg-tcnet: An accurate temporal convolutional network for embedded motor-imagery brain–machine interfaces. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), 2958–2965 (IEEE, 2020).

Altaheri, H., Muhammad, G. & Alsulaiman, M. Dynamic convolution with multilevel attention for eeg-based motor imagery decoding. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 18579–18588 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liao WD: Algorithm, Experiments, Writing. Liu HY and Wang WD: Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, W., Liu, H. & Wang, W. Advancing BCI with a transformer-based model for motor imagery classification. Sci Rep 15, 23380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06364-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06364-4