Abstract

Patients with severe motor and intellectual disability (SMID) experience persistent spastic pain and severe malpositioning of the limbs, exacerbated by the lack of effective treatment for severe spastic palsy. This study (UMIN-CTR, UMIN000048842) aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy (rESWT) for spastic palsy in these patients. rESWT was applied to the biceps brachii of 15 elbow joints with flexion pattern spastic palsy of Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) grade 1+ or greater in 11 patients with SMID. The MAS score, elbow range of motion (ROM) and adverse events were monitored for up to 10 weeks. Electromyography signals at rest were recorded on 8 elbow joints. Following a single rESWT session, the spasticity of the elbow joint immediately decreased, the MAS score significantly decreased from 2 (range, 2–3) to 1 (range, 1–2), and the elbow ROM significantly increased by 10° (range, 0°–15°). Moreover, muscle activity decreased by 24% (range, 11–37%), being clinically meaningful in SMID. rESWT resulted in an immediate and clear improvement in the MAS score for approximately 8 weeks and in the elbow ROM, continuing even at 10 weeks. Our findings highlight rESWT as a non-invasive therapy for spastic palsy in patients with SMID.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In Japan, severe motor and intellectual disability (SMID) is defined as limited physical functioning with a bedridden or sedentary condition and an intelligence quotient < 351,2. SMID is a subset of profound intellectual and motor disabilities (PIMD) and severe or profound intellectual and motor disabilities (SPIMD), which are globally accepted terminologies3. SMID is most commonly caused by cerebral palsy, in addition to encephalitis, encephalopathy, congenital abnormalities, traumatic brain injury, and degenerative diseases1. A previous study including long-term residents of Japanese national sanatoriums and national hospital wards reported that the average life expectancy of severely disabled children was < 15 years in 1982 but had improved significantly to approximately 36 years by 2009; nonetheless, many issues in daily life still need to be addressed1, such as different types of paralysis, joint contractures, and postural problems caused by muscle tension4. Spasticity occurs in 80% of children with cerebral palsy5, and up to 60% of children with spastic-predominant cerebral palsy also exhibit dystonia6, making it one of one of the most serious problems in SMID7,8. Researchers have not proposed that spastic paresis includes movement abnormalities that are caused by both nerve and muscle problems and not only spasticity, spastic myopathy, co-contraction, spastic dystonia, or stretch-sensitive paresis9,10,11,12. Although it is a common symptom associated with neurological disorders such as stroke, spinal cord injury, and cerebral palsy13,14,15, patients with SMID experience particularly severe spastic palsy throughout the body, and their mobility is confined to transitioning from a bedridden state to a wheelchair.

Efforts to manage spastic palsy in patients with SMID have included various approaches. These involve using positioning techniques, developing sit-to-stand devices, and adapting wheelchairs to individual physical needs16. Additionally, oral muscle relaxants have been utilized to help alleviate symptoms17. However, the effects of the above measures are limited, and patients continue to experience persistent spastic pain, requiring substantial assistance, severe malpositioning of the limbs, which progresses gradually, and a decline in activities of daily living and overall quality of life (Fig. 1).

Currently, botulinum neurotoxin-A injection is a highly effective treatment for spastic palsy but is dose-limited18,19. Its effectiveness is limited when dealing with large areas of spastic palsy. In institutions using this treatment for patients with SMID, there are concerns about the administration of the drug by doctors and securing the necessary financial resources for this expensive medication, which limits its widespread use among patients with SMID. In addition, intrathecal baclofen is a more effective treatment due to the direct application of muscle relaxants to the spinal cord20,21; however, it is not an option for patients with SMID, as the procedure is highly invasive and requires transfer to a hospital for implantation. Other approaches, including targeted physical therapy, occupational therapy, orthotic interventions, neuromodulation, and emerging technologies such as virtual reality-based rehabilitation, have also demonstrated beneficial effects on spasticity and motor function1,2. Its use is not feasible in patients with SMID. Therefore, a feasible, safe, and sustainable treatment for spasticity that is suitable for patients with SMID needs to be established.

Radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy (rESWT) sends high-energy sound waves directly to the affected area to reduce pain and promote tissue repair. It is mainly used in the fields of orthopedics and rehabilitation and is effective for chronic pain, such as tendonitis and muscle pain. rESWT has traditionally been used for muscle fatigue and pain in athletes, providing pain relief and promoting tissue repair22,23,24. Furthermore, its efficacy in managing spasticity in patients with stroke has recently been documented25,26,27. The application of rESWT in patients with post-stroke spastic palsy has been shown to relieve muscle stiffness and induce functional improvements28.

In several studies, rESWT has been reported to be effective in improving symptoms of spastic gait disturbance in children with cerebral palsy29,30,31. Although rESWT is a promising method for the treatment of spasticity, its mechanism has not been clearly understood, nor has the duration of its effect and the optimal treatment protocols been fully established. In addition, the treatment of spasticity in patients with SMID has not been reported. We hypothesized that rESWT would improve severe spasticity, which causes continuous pain and skeletal deformities in patients with chronic SMID. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of rESWT therapy for spasticity in patients with SMID. Our findings can help develop an effective and consecutive method that can be used to treat spastic palsy in routine clinical practice.

Methods

Study design, setting, and period

In this single-center, longitudinal, interventional study, we used convenient sampling to recruit patients with SMID who were admitted to the Tokyo Metropolitan Tobu Ryoiku Center (Tokyo, Japan) , a facility that offers disability care. These facilities provide long-term care for patients with SMID, offering appropriate medical and rehabilitation services. We recruited patients who met the inclusion criteria and whose parents or guardians agreed to their participation. This study was conducted from August 2023 to August 2024.

Participants

Although elbow joint flexion is affected by other muscles, such as the BR and brachial muscles, it is mainly moved by the biceps as the brachialis lies deep beneath the biceps brachii and may not be effectively treated with rESWT. The BR is less palpable and difficult to accurately target in clinical settings; thus, the elbow joint was selected as the target muscle of this study since it can reduce the number of elements involved in complex muscle activity. The inclusion criteria were enrollment in the Tokyo Metropolitan Tobu Ryoiku Center, age ≥ 20 years, and an elbow flexor spasticity of grade 1+ or more in the elbow. Patients were excluded if they were aged < 20 years and had elbow flexor spasticity of grade 4 with complete retraction and no passive elbow extension. Also, they were excluded if they had contraindications to rESWT (such as malignancy, severe coagulation dysfunction, or infections), had previously received botulinum toxin injections, or did not provide signed informed consent (either from the patients or their families).

Participant characteristics

Of a total of 120 residents in the facility, 42 met the inclusion criteria. The study was conducted with 11 residents whose families agreed to their recruitment in the study. rESWT was performed on 15 elbows of the 11 included patients with SMID and spastic elbows (eight males and five females; average age, 44.5 years). Of these, nine patients had clinically diagnosed cerebral palsy and two had traumatic brain injury in early childhood. In terms of physical ability, all patients were bedridden (Table 1), and seven patients also had scoliosis.

Treatment

rESWT was performed between August 2023 and March 2024 on all participants on the elbow with spasticity using a pressure wave treatment device (Physio Shockmaster®, Sakai Medical Co. Tokyo, Japan). The target muscle was the biceps brachii at the elbow joint. rESWT was performed for only one session per patient, and the sessions were all conducted by the first author after identifying the biceps brachii and with the patient in the bed-rest position. The treatment protocol of rESWT includes 1000 shots (frequency, 17 Hz frequency; pressure, 1.4 bar pressure) applied with an R15 probe, mainly in the middle of the muscle belly of the biceps brachii. Furthermore, 1500 shots (frequency, 17 Hz; pressure, 1.6 bar) with an R20 probe were applied diffusely on the tendon of the biceps brachii at the elbow. This protocol was based on previous studies using rESWT in patients with upper limb spasticity after stroke or brain injury32,33,34,35,36.

Data collection and reduction

The spasticity of the biceps brachii was assessed using the MAS before and immediately after rESWT and once a week thereafter for up to 10 weeks to evaluate the immediate and persistent effect of the treatment on spasticity at the bed-rest position. The MAS grades resistance encountered during passive stretching37 on a six-point scale: 0, no increase in tone; 1, slightly increased tone with a catch/release or minimal resistance at the end of ROM; 1+, slightly increased tone with a catch followed by minimal resistance throughout less than half of the ROM; 2, a more marked increased tone through most of the ROM but the affected part moves easily; 3, considerably increased tone making passive movement difficult; and 4, rigidity in flexion or extension. For the convenience of statistical analysis, MAS grade 1+ was counted as 1.5. Additionally, passive extension of the elbow ROM was measured with a goniometer before and immediately after rESWT and once a week thereafter for up to 10 weeks.

EMG signals at rest were recorded on eight elbow joints using a surface EMG (Ultium EMG, EM-U810M8, Noraxon USA Inc., Scottsdale, AZ, USA) and recorded at 2000 Hz with a band-pass filter (5–500 Hz) on a personal computer. Before attaching the electrodes, the skin was cleaned with alcohol. The electrode application site for EMG was determined according to the guidelines of SENIAM (Surface ElectroMyoGraphy for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles; URL: http://seniam.org/). Bipolar surface electrodes (SNAPRODE, TEO-3030DR, Fukuda-Denshi, Tokyo, Japan) were attached to the long head of the biceps brachii and triceps brachii muscles. The electrode to the biceps was placed on the line between the medial acromion and the fossa cubit at 1/3rd the distance from the fossa cubit. The electrode to the triceps was placed on the line between the medial acromion and the fossa cubit at 1/3rd the distance from the fossa cubit. The electrode to the triceps was placed in the middle of the line between the posterior crista of the acromion and olecranon at two finger widths lateral to the line. Since the SENIAN guidelines recommend a 20-mm interelectrode spacing, the diameter of this electrode was 30 mm, which overlapped the adhesive frames and set the spacing to 25 mm to reduce crosstalk38. The electrodes for each muscle were attached parallel to the muscle fibers of the biceps brachii and triceps brachii (Fig. 2a,b). Since patients were bedridden, the EMG and angle of the elbow were both measured in the relaxed posture they usually adopt while lying in bed. In patients who were able to extend their elbows after rESWT, we measured the EMG at the extended elbows. The EMG of the biceps and triceps during active extension was also measured in patients who were able to extend their elbows on their own after pressure wave therapy.

Data on the patient’s age, sex, height, weight, body mass index, primary disease, and adverse events were collected from the medical databases of the institutes. Regarding adverse events, the first author and attending physicians documented them during and after the treatment. Patients with SMID have difficulty speaking, and their facial expressions can be difficult to interpret due to co-contraction of the facial muscles. Therefore, we also evaluated changes in blood pressure and heart rate during the treatment and interpreted facial expressions with the help of the attending nurse, therapist, and the patient’s usual caregiver during the study.

Data analysis

Since this is the first study to examine the effects of rESWT treatment for patients with SMID, the effect size was unknown; hence, a statistical sample size calculation was not implemented.

Forty-nine patients met the inclusion criteria, of which, we expected to recruit around 30 patients. However, due to the difficulty of contacting the guardians, we were only able to recruit 11 patients. Because of the small sample size, we considered only using descriptive statistics; however, due to the large effect, we conducted a significance test.

In the statistical analysis, the MAS scores and ROM were compared before rESWT, immediately afterward, and weekly thereafter. In the analysis of surface EMG data from the biceps and triceps brachii, all raw EMG signals were rectified and smoothed using the root-mean-square algorithm with a 100-ms time reference. The average amplitude of over 10 consecutive seconds at rest, before and immediately after rESWT, was compared. The improvement rate was calculated by dividing the post-rESWT value by the pre-rESWT value. Because MAS is discrete data, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-sided) was used to assess changes between pre-treatment and each follow-up time point. Additionally, to examine the overall time-dependent change in MAS scores across the 10-week period, a supplementary Friedman test was conducted. ROM and surface EMG data are continuous, but normality could not be confirmed due to the small sample size; hence, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-sided) was used. Spearman’s correlation was used to assess the relationship between MAS score changes (ΔMAS: 10w − pre) and ROM maintenance (ΔROM: 10w − post). The significance level was set at α = 0.05. The statistical tests used the Bell Curve for Excel 2016 (Social Research and Information, Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Modified Ashworth Scale

The median (interquartile range [IQR], range) MAS scores significantly decreased from 2 (2–3, 1.5–2) at the baseline assessment to 1(1–2, 1–2) immediately after rESWT (p = 0.0011) and remained significant until 8 weeks after treatment (Fig. 3).

Changes in MAS scores and the changes of the elbow ROM as a result of rESWT. The x-axis (pre is before treatment, post is immediately after rESWT, and then every week subsequently), and compare it to the pre-value. The MAS data are presented as median and IQR and the changes in the elbow ROM are shown as mean, median, and IQR. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed to compare the MAS before and immediately after rESWT and then every week subsequently. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed to compare the pre-baseline ROM and pre and paired ROM each week after rESWT. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed between the passive maximum extension angle before rESWT and the maximum extension angle each week. MAS Modified Ashworth Scale, ROM range of motion, rESWT radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy

These comparisons between pre-treatment and each subsequent time point were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. To further examine overall time-dependent changes in MAS scores, a supplementary Friedman test was conducted across the entire 10-week period, revealing a significant difference (χ2(7) = 41.97, p < 0.000001).

Passive elbow joint range of motion

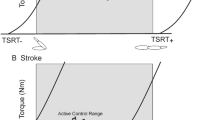

Performing ESWT on the biceps resulted in immediate improvement in the extension direction in passive ROM (Fig. 4). The median (IQR) of the passive extension of the elbow ROM significantly increased from baseline assessment to after the rESWT 10° (0°–15°) (p = 0.0096) and remained significant until 10 weeks after treatment (Fig. 3). No significant correlation was found between changes in MAS (ΔMAS: 10w − pre) and ROM maintenance (ΔROM: 10w − post) (Spearman ρ = − 0.14, p = 0.618), indicating that increased spasticity did not directly correspond to loss of passive ROM.

The elbow passive ROM before and after rESWT. The range of motion of the elbow is measured according to the angles in the figure, and the reference range of motion of the elbow joint is considered to be from 0 to 145°. Patients with SMID are often thin and have a large flexion angle that exceeds this reference range of motion. The figure shows the passive range of motion of the elbow joint before and after rESWT in all patients. The lower value of the bar in the graph is the “angle when the elbow is fully extended,” and the upper value is the “angle when the elbow is fully flexed.”

Electromyography

Surface electromyography (EMG) of the biceps brachii and the triceps brachii showed strong muscle hyperactivity in the biceps brachii at rest. On the active extension of the elbow, co-contraction of the biceps and triceps muscles was observed if the patient had difficulty in extending their elbow before rESWT. Immediately after the rESWT to the biceps brachii, in all cases, the amplitude of the surface EMG of the biceps brachii decreased, and active elbow extension was possible along with triceps contraction due to decreased muscle contraction of the biceps brachii muscle (Fig. 5). The amplitude of the biceps brachii muscle during the 10 s immediately after the rESWT decreased to 24% (11–37) of that before the rESWT. The amplitude of the triceps brachii muscle during the 10 s immediately after the rESWT was 70% (47–109%) of that before the rESWT (Fig. 6).

All the raw amplitude of the biceps brachii (A) and triceps (B) at rest before and after rESWT. The ratio of change in the average amplitude of resting surface electromyography over 10 consecutive seconds before and after rESWT (C). The data were not normally distributed; therefore, the mean and standard deviation values and numerical data group of the quartiles are presented.

Adverse events

Two patients experienced small, mild subcutaneous hemorrhages immediately after treatment; both patients recovered within 2 days.

Discussion

In a single rESWT session targeting the elbow of patients with SMID, the MAS score decreased by 1.0 after the treatment. The biceps muscle surface EMG showed high muscle activity at rest due to spasticity, and the average amplitude during the 10 s immediately after the rESWT decreased to 32 ± 5% of that before rESWT.

Post-hoc power analyses using G*Power (version 3.1) were conducted for the three main outcome measures: MAS scores, passive elbow ROM, and EMG amplitudes of the biceps brachii. For MAS scores (n = 15), the effect size was estimated as dz = 1.35, resulting in a calculated power of 0.98. For passive elbow ROM (n = 15), the effect size was estimated as dz = 0.90, with an achieved power of 0.8639. For surface EMG amplitudes (n = 8), the effect size was estimated as dz = 3.9, indicating a power greater than 0.99. These results support the statistical validity of the observed significant differences despite the small sample size.

Kenmoku et al. reported that rESW exposure significantly reduced compound muscle action potential amplitude without delaying latency in exposed muscles. The rESW-exposed muscles exhibited NMJs with irregular end plates in an animal study, and this transient degeneration of NMJs reduced the compound muscle action potential amplitude40. Botulinum toxin blocks the release of acetylcholine from nerve endings to paralyze muscles and decrease pain response; it has a long duration of action, lasting up to 5 months after initial treatment41. However, we excluded its use because it could have interfered with the effect of rESWT. In our study, there was an immediate marked decrease in surface muscle activity of the biceps after the rESWT in patients with SMID.

Although the MAS score gradually increased each week, a significant reduction was observed at 8 weeks compared to the pre-rESWT levels. Li et al. reported that the MAS score after a single rESWT session was significantly lower than that after sham rESWT after 8 weeks in patients with chronic stroke, a duration similar to that in our study of patients with SMID34.

The passive elbow ROM improved immediately at an average of 10° (0°–15°) in extension after the rESWT to the biceps brachii, along with a decrease in the MAS score, although the average age of our study population was 44.5 years in the elbow joint, which is limited to MAS1+ to 3 in the inclusion criteria this time. In patients with adult SMID (mostly due to cerebral palsy), spasticity typically develops within 1 or 2 years of birth, and the course of the disease is considerably longer than that in patients with stroke who have undergone rESWT25,27. In cases of adult SMID, the patients have been in a spastic state, and the tendon has been fibrosed as “spastic myopathy”9 for a long period; therefore, even if biceps spasticity is relieved, there is limited improvement in extension. However, cases with an improvement of 30° were also noted in the elbow joint, which is limited to a MAS grade of 1+ to 3, although the elbow ROM remained limited in elbow extension even after the rESWT due to long-term contracture in our patients (Fig. 4).

The improvement in the elbow ROM persisted even as the MAS scores increased, with some cases showing further gains over the 10-week period. Physiotherapists perform passive ROM exercises on joints with spastic myopathy and joint contractures daily. This improvement was attributed to the effect of rehabilitation conducted while the MAS scores decreased due to rESWT. In rehabilitation therapy for patients with SMID, the high level of spasticity typically limits joint ROM training, leading to progressive joint contracture over time. However, after rESWT, ROM treatment could progress when spasticity was suppressed. Even as the MAS scores increased over time, some cases showed sustained or improved ROM. ESWT is meaningful in rehabilitation treatment, and its concept is similar to rehabilitation treatment that improves ROM while suppressing spasticity with botulinum toxin42,43,44.

The observed dissociation between the gradual increase in MAS scores and the sustained or improved elbow ROM may be explained by a combination of physiological and rehabilitative factors. While MAS reflects neural-mediated resistance to passive stretch, ROM is also influenced by the mechanical properties of muscles and connective tissues. rESWT may have transiently suppressed motor neuron hyperexcitability and reduced reflex hyperactivity, contributing to a short-term decrease in spasticity. Concurrently, rESWT may have induced structural changes such as reduced muscle stiffness or improved elasticity in fibrotic or contracted tissues. In our setting, these biological effects were likely enhanced by continuous passive ROM exercises and positioning therapy, which were administered during the MAS-lowering phase. This rehabilitative input may have helped preserve or even increase joint mobility, even as neural spasticity indicators began to rebound. Therefore, the observed improvement in ROM despite rising MAS scores may reflect the synergy between transient neuromodulatory effects of rESWT and ongoing physical therapy aimed at preserving soft tissue extensibility.

The mechanisms underlying the effects of shock waves may vary. Dymarek et al. observed a significant increase in infrared thermal imaging values after ESWT, suggesting an improvement in the trophic conditions of the spastic muscles45. Similarly, Leng et al. used the NeuroFlexor method, a myotonometer, and electrical impedance myography and found a significant decrease in muscle tone, stiffness, and viscosity after ESWT46. Wang et al. reported that shock wave therapy promotes neurovascular ingrowth associated with the early release of angiogenesis-related markers at the Achilles tendon-bone junction in rabbits47. Nada et al. reported that rehabilitation interventions using rESWT for patients with chronic stroke (more than 6 months after onset) resulted in reduced fat infiltration and fibrosis, alongside a replacement of spastic muscles33. ESWT may induce a biological response that alternates between metabolic and proliferative processes, affecting muscle fibrosis and rheological properties. By alleviating spasticity, effective passive ROM rehabilitation becomes possible despite existing limitations in the elbow ROM due to joint contracture or the shortening of muscles and tendons in all cases. ESWT may have induced a biological response that alternately stimulates metabolic and proliferative processes and may have improved ROM by improving tendon fibrosis and affecting muscle fibrosis and its rheological properties. Our findings suggest that continued treatment may lead to cumulative improvements in the ROM.

rESWT was performed on patients with SMID and the procedure resulted in temporary redness in the treated area and subcutaneous petechial hemorrhage in two cases; however, no hematoma formation was reported. rESWT may cause a certain degree of irritation and pain; however, no signs of severe pain were observed in the facial expressions of patients with SMID. Additionally, no symptomatic events, such as fractures, were monitored during the rESWT session and subsequent rehabilitation, although a marked reduction in bone density was observed in the severely affected patients48. No specific symptomatic events were observed, similar to the findings of other studies on chronic stroke or cerebral palsy31,49.

Although this study was conducted on the elbow, rESWT treatment for spasticity may also be effective for spasticity throughout the body. Li et al. also reported that stimulation in three consecutive sessions, comprising one session per week, decreases the MAS scores significantly more and for a longer duration (up to 16 weeks) than stimulation in a single session24. Thus, multiple stimulations can have a stronger and more sustained effect on spasticity in patients with SMID. Further investigation is needed to understand the optimal energy of the stimulation and interval between sessions to achieve more effective results. Nonetheless, it is a safe and inexpensive treatment that can be applied to multiple joints throughout the body simultaneously, and it could be used in a wide range of facilities.

In this study, the ROMs of the joints of patients with SMID were measured by physiotherapists, who perform rehabilitation daily, using a goniometer. Normally, ROM measurements should be taken in a fixed posture; however, it is difficult to measure patients with limited body posture or joint contracture. To make the measurement easier and more accurate, 3D video analysis, inertial measurement, wearable sensors, and smartphones were introduced50,51,52,53,54. The markerless video-based motion analysis techniques may also be effective as the approaches for non-invasive, objective quantification of elbow flexion and extension and are particularly well suited for patients with SMIDS who may not tolerate marker-based systems55,56. These evaluation methods should be used to assess the effectiveness of rESWT in improving the ROM of various joints.

This study has some limitations. First, we only examined 15 elbows in this single center study, resulting in a small dataset with limited variation in the results. Further multicenter studies are required to validate our findings, and future studies with a larger sample size are warranted. Second, we applied the same intensity, number of shots, and frequency settings for the treatment, limiting the study to a single session. Although rESWT was very effective in reducing the severe spasticity of patients with SMID and improving the ROM of the elbow joint, developing a comprehensive protocol will require including multiple stimuli or performing multiple treatments, as well as considering joints other than the elbow and evaluating the effects of multiple stimuli and cumulative effects of treatment. A few studies have suggested that multiple repetitions of rESWT will lead to further improvements, and we will also consider repeating rESWT in the future. Third, the size of the electrodes in our study was larger than that recommended by SENIAM, and although we tried to shorten the distance between the electrodes, crosstalk could still have happened. Further research is needed on topics such as the current state of spasticity and potential for rESWT to mitigate the progression of scoliosis by controlling spasticity in patients with SMID.

In conclusion, rESWT for severe spasticity in the elbow of patients with SMID resulted in an immediate and clear improvement, with effects lasting for approximately 8 weeks, including an increase in the elbow ROM despite contracture. The improvement in the elbow ROM, despite the gradual increase in MAS scores, continued even at 10 weeks. In some cases, the angle improved over the course of the study due to ROM rehabilitation conducted, while the MAS scores decreased due to rESWT. Our study findings suggest that rESWT is a useful non-invasive therapy for spasticity in patients with SMID.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sasaki, M. Considering the way of medical care from the cause of death of children (and adults) with severe mental and physical disabilities (Japanese). J. Jpn Soc. Severe Mot. Intellect. Disabil. 37, 51–57 (2012).

Sakai, T., Shirai, T. & Oishi, T. Vitamins K and D deficiency in severe motor and intellectually disabled patients. Brain Dev. 43, 200–207 (2021).

Nakken, H. & Vlaskamp, C. A need for a taxonomy for profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Policy Pract. Intel. Disabil. 4, 83–87 (2007).

Matsubasa, T., Mitsubuchi, H., Kimura, A., Shinohara, M. & Endo, F. Medically dependent severe motor and intellectual disabilities: Time study of medical care. Pediatr. Int. 59, 714–719 (2017).

Vitrikas, K., Dalton, H. & Breish, D. Cerebral palsy: An overview. Am. Fam. Phys. 101, 213–220 (2020).

Ueda, K., Aravamuthan, B. R. & Pearson, T. S. Dystonia in individuals with spastic cerebral palsy and isolated periventricular leukomalacia. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 65, 94–99 (2023).

Ishimaru, K. et al. Tumor screening, incidence, and treatment for patients with severe motor and intellectual disabilities. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 89, 212–214 (2022).

Ohta, K. et al. Tendency and risk factors of acute pancreatitis in children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities: A single-center study. Brain Dev. 45, 126–133 (2023).

Gracies, J. M. et al. Spastic paresis: A treatable movement disorder. Mov. Disord. 40, 44–50 (2025).

Gracies, J. M. Pathophysiology of spastic paresis. II. Emergence of muscle overactivity. Muscle Nerve 31, 552–571 (2005).

Gracies, J. M. Pathophysiology of spastic paresis. I. Paresis and soft tissue changes. Muscle Nerve 31, 535–551 (2005).

Baude, M., Nielsen, J. B. & Gracies, J. M. The neurophysiology of deforming spastic paresis: A revised taxonomy. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 62, 426–430 (2019).

Ward, A. B. A literature review of the pathophysiology and onset of post-stroke spasticity. Eur. J. Neurol. 19, 21–27 (2012).

Albright, A. L. Spasticity and movement disorders in cerebral palsy. Childs Nerv. Syst. 39, 2877–2886 (2023).

Field-Fote, E. C. et al. Characterizing the experience of spasticity after spinal cord injury: A national survey project of the spinal cord injury model systems centers. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 103, 764-772.e2 (2022).

Sato, H. Postural deformity in children with cerebral palsy: why it occurs and how is it managed. Phys. Ther. Res. 23, 8–14 (2020).

Peck, J. et al. Oral muscle relaxants for the treatment of chronic pain associated with cerebral palsy. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 50(Suppl 1), 142–162 (2020).

Dressler, D. et al. Consensus guidelines for botulinum toxin therapy: General algorithms and dosing tables for dystonia and spasticity. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 128, 321–335 (2021).

Simpson, D. M. et al. Practice guideline update summary: Botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of blepharospasm, cervical dystonia, adult spasticity, and headache: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 86, 1818–1826 (2016).

Hasnat, M. J. & Rice, J. E. Intrathecal baclofen for treating spasticity in children with cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD004552 (2015).

Coulter, I. C., Lohkamp, L. N. & Ibrahim, G. M. Intrathecal baclofen for hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP). Childs Nerv. Syst. 36, 1585–1587 (2020).

Walewicz, K. et al. Effect of radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy on pain intensity, functional efficiency, and postural control parameters in patients with chronic low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Med. 9, 568 (2020).

Melese, H., Alamer, A., Getie, K., Nigussie, F. & Ayhualem, S. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy on pain and foot functions in subjects with chronic plantar fasciitis: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Disabil. Rehabil. 44, 5007–5014 (2022).

Costantino, C., Nuresi, C., Ammendolia, A., Ape, L. & Frizziero, A. Rehabilitative treatments in adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 62, 1505–1511 (2022).

Brunelli, S. et al. Effect of early radial shock wave treatment on spasticity in subacute stroke patients: A pilot study. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 8064548 (2022).

Cabanas-Valdés, R. et al. The effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy to reduce lower limb spasticity in stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 27, 137–157 (2020).

Li, G. et al. Effects of radial extracorporeal shockwave therapy on spasticity of upper-limb agonist/antagonist muscles in patients affected by stroke: A randomized, single-blind clinical trial. Age Ageing 49, 246–252 (2020).

Tabra, S. A. A., Zaghloul, M. I. & Alashkar, D. S. Extracorporeal shock wave as adjuvant therapy for wrist and hand spasticity in post-stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Egypt. Rheumatol. Rehabil. 48, 21 (2021).

Lin, Y., Wang, G. & Wang, B. Rehabilitation treatment of spastic cerebral palsy with radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy and rehabilitation therapy. Medicine 97, e13828 (2018).

Vidal, X., Morral, A., Costa, L. & Tur, M. Radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy (rESWT) in the treatment of spasticity in cerebral palsy: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. NeuroRehabilitation 29, 413–419 (2011).

Chang, M. C. et al. Effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy on controlling spasticity in cerebral palsy patients: A meta-analysis of timing of outcome measurement. Children (Basel) 10, 332 (2023).

Hsu, P. C., Chang, K. V., Chiu, Y. H., Wu, W. T. & Özçakar, L. Comparative effectiveness of botulinum toxin injections and extracorporeal shockwave therapy for post-stroke spasticity: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. EClinicalmedicine 43, 101222 (2022).

Nada, D. W., El Sharkawy, A. M., Elbarky, E. M., Rageh, E. S. M. & Allam, A. E. S. Radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy as an additional treatment modality for spastic equinus deformity in chronic hemiplegic patients. A randomized controlled study. Disabil. Rehabil. 46, 4486–4494 (2024).

Li, T. Y. et al. Effect of radial shock wave therapy on spasticity of the upper limb in patients with chronic stroke: A prospective, randomized, single blind, controlled trial. Medicine (Baltim.) 95, e3544 (2016).

Dymarek, R. et al. Shock waves as a treatment modality for spasticity reduction and recovery improvement in post-stroke adults: Current evidence and qualitative systematic review. Clin. Interv. Aging 6(15), 9–28 (2020).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on spasticity in patients after brain injury: A meta-analysis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 26(10), 1641–1647 (2014).

Bohannon, R. W. & Smith, M. B. Interrater reliability of a modified Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys. Ther. 67, 206–207 (1987).

Merlo, A., Bò, M. C. & Campanini, I. Electrode size and placement for surface EMG bipolar detection from the brachioradialis muscle: A scoping review. Sensors (Basel) 21, 7322 (2021).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39(2), 175–191 (2007).

Kenmoku, T. et al. Extracorporeal shock wave treatment can selectively destroy end plates in neuromuscular junctions. Muscle Nerve 57, 466–472 (2018).

Patil, S. et al. Botulinum toxin: Pharmacology and therapeutic roles in pain states. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 20, 15 (2016).

Farag, S. M., Mohammed, M. O., El-Sobky, T. A., ElKadery, N. A. & ElZohiery, A. K. Botulinum toxin A injection in treatment of upper limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. JBJS Rev. 8, e0119 (2020).

Bascuñana-Ambrós, H. et al. Emerging concepts and evidence in telematics novel approaches or treatments for spasticity management after botulinum injection. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2, 720505 (2021).

Mills, P. B., Finlayson, H., Sudol, M. & O’Connor, R. Systematic review of adjunct therapies to improve outcomes following botulinum toxin injection for treatment of limb spasticity. Clin. Rehabil. 30, 537–548 (2016).

Dymarek, R., Taradaj, J. & Rosińczuk, J. Extracorporeal shock wave stimulation as alternative treatment modality for wrist and fingers spasticity in poststroke patients: A prospective, open-label, preliminary clinical trial. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016, 4648101 (2016).

Leng, Y. et al. The effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on spastic muscle of the wrist joint in stroke survivors: Evidence from neuromechanical analysis. Front. Neurosci. 14, 580762 (2020).

Wang, C. J. et al. Shock wave therapy induces neovascularization at the tendon-bone junction. A study in rabbits. J. Orthop. Res. 21, 984–989 (2003).

Sakai, T., Honzawa, S., Kaga, M., Iwasaki, Y. & Masuyama, T. Osteoporosis pathology in people with severe motor and intellectual disability. Brain Dev. 42, 256–263 (2020).

Xiang, J., Wang, W., Jiang, W. & Qian, Q. Effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on spasticity in post-stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Rehabil. Med. 50, 852–859 (2018).

Rajkumar, A. et al. Wearable inertial sensors for range of motion assessment. IEEE Sens. J. 20, 3777–3787 (2020).

Palmieri, M., Donno, L., Cimolin, V. & Galli, M. Cervical range of motion assessment through inertial technology: A validity and reliability study. Sensors (Basel) 23, 6013 (2023).

Walmsley, C. P. et al. Measurement of upper limb range of motion using wearable sensors: A systematic review. Sports Med. Open 4, 53 (2018).

Cox-Brinkman, J., Smeulders, M. J., Hollak, C. E. & Wijburg, F. A. Restricted upper extremity range of motion in mucopolysaccharidosis type I: No response to 1 year of enzyme replacement therapy. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 30, 47–50 (2007).

Meislin, M. A., Wagner, E. R. & Shin, A. Y. A comparison of elbow range of motion measurements: Smartphone-based digital photography versus goniometric measurements. J. Hand Surg. Am. 41, 510-515.e1 (2016).

Rammer, J. R., Krzak, J. J., Riedel, S. A. & Harris, G. F. Evaluation of upper extremity movement characteristics during standardized pediatric functional assessment with a Kinect®-based markerless motion analysis system. in 2014 36th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2525-8 (2014).

Francia, C. et al. Validation of a MediaPipe system for markerless motion analysis during virtual reality rehabilitation. In Extended Reality. XR Salento 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science Vol. 15029 (eds De Paolis, L. T. et al.) 40–49 (Springer, 2024).

Acknowledgements

The equipment used in this research was purchased with funds raised through a crowdfunding campaign ‘'rESWT for severely mentally and physically disabled children suffering from incapacity.’ on ‘Ready for.’ We thank all the contributors for their support. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the therapists at the Tobu Rehabilitation Center, who helped us coordinate the timing of the shockwave therapy and provided support for the treatment. We would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing and assistance in proofreading the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S. conceived the study and planned and performed the treatment. M.H and Y.T. analyzed the data and contributed to preparation of the manuscript. A.Y. and T.O supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (approval number: M2022-021; August 1, 2023) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (52nd World Medical Association General Assembly Edinburgh, Scotland, October 2000). Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from the participants or their parents or guardians in cases of participants with diminished capacity to provide consent. This study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR, UMIN000048842) on 01/12/2022.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakai, T., Hirao, M., Takashina, Y. et al. Pragmatic single center longitudinal study assessing radial extracorporeal shock wave therapy for patients with severe mental and physical disabilities. Sci Rep 15, 22968 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06414-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06414-x