Abstract

This study proposes ConditionCDVAE+, a crystal diffusion variational autoencoder (CDVAE) based deep generative model for inverse design of van der Waals (vdW) heterostructures. To address the challenges of traditional experimental methods relying on trial-and-error and existing models struggling to incorporate target property constraints, this work achieves breakthroughs through three innovative stages: (1) introduce the SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network EquiformerV2 as the encoder-decoder within the CDVAE framework to enhance the generation quality of the model; (2) design a module integrating Low-rank Multimodal Fusion and Generative Adversarial Networks to map properties and structures into a joint latent space; and (3) for the first time propose a generative model for the vdW heterostructures, by conducting experimental validation on the dataset constructed from Janus III–VI vdW heterostructures. Experiments demonstrate that ConditionCDVAE+ achieves optimal root mean square error for crystal reconstruction, with improved generation quality. Density Functional Theory calculations confirms 99.51% of generated samples converge to energy minima, indicating superior ground-state convergence. The effectiveness of the model under conditional guidance has also been extensively validated. This framework provides an efficient solution for target-oriented design of vdW heterostructures and holds promise for accelerating the development of novel optoelectronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the first discovery of graphene exfoliated from graphite in 20041, the materials science community has witnessed blossom of two-dimensional materials due to their exotic electronic, optical, and mechanical properties compared to corresponding bulk materials2,3. With further research, scientists discovered that combining different two-dimensional materials into van der Waals (vdW) heterostructures allows for the modulation of their electronic, optical, and mechanical properties, thereby expanding their applications in electronic devices, optoelectronic materials, and catalysis4. Due to the lack of strict lattice matching requirements and diverse bandgap properties5, various vdW heterostructures can be created by integrating various two-dimensional materials in a relatively flexible manner. With the extensive exploration of two-dimensional materials in recent years6,7,8,9, the number of possible two-dimensional materials has reached thousands, and the potential combinations of vdW heterostructures could even reach millions. However, traditional design methods through experiments such as mechanical stacking, physical epitaxy growth, and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) still rely heavily on empirical experiments and lack systematic design strategies.

In the context of the development of computational materials science, high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) calculations have been widely utilized to discover vdW heterostructures with powerful functionalities, leading to the creation of a series of databases10,11,12,13. Nevertheless, due to the intrinsic sophistication in physics and numerical method, DFT calculations often results in significant computational costs despite of these achievements. Fortunately, with the introduction of machine learning algorithms such as ALIGNN14 and CGCNN15, researchers can train models using data generated from first-principles calculations or classical molecular dynamics simulations to predict the properties of materials. This strategy of combining machine learning with high-throughput calculations enables researchers to screen potential vdW heterostructures in a shorter time frame16,17. Such strategy provides new momentum for the advancement of materials science, yet it still does not address the inverse design challenge of generating novel structures with favored property.

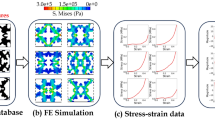

Training and generation flow chart of ConditionCDVAE+. In the first step of the training process, the latent vector \(z\), produced by the encoder, is fused with the conditional property vector \(c\) through LMF to obtain the conditional latent vector \(z_{c}\). Then, \(z_{c}\) is processed by multiple MLPs to predict the lattice parameters \(L\), atom types (including the number of atoms) \(A\), and properties of the structure. Subsequently, the \(A\) and fractional coordinates \(X\), with different levels of noise added, are input into the decoder along with the \(L\) and \(z_{c}\) to denoise the \(\bar{A}\) and \(\bar{X}\). In the second step of training, noise and \(c\) are served as inputs to the GAN to generate \(z'\) with the target \(c\). Subsequently, the discriminator evaluates the scores of \(z\) and \(z'\) to compute their Wasserstein distance, and updates the parameters of the generator and discriminator. During the generation process, the generator samples a target latent vector \(z\) from the latent space using \(c\). Subsequently, \(z\) undergoes feature fusion with the \(c\) through LMF, yielding the \(z_c\). This fused representation is then processed by MLPs, followed by Langevin dynamics-based denoising conditioned on \(z_c\), ultimately producing the final structure.

In recent years, deep generative models, as an advanced artificial intelligence technology, have been widely applied in the field of materials design18. By learning from extensive materials data, deep generative models are capable of generating innovative material structures, especially those deviated from scientific intuition. For example, Noh et al. proposed iMatGen, an inverse design framework based on 3D voxel structural representation and variational autoencoders, which successfully predicted several synthesizable novel structures19. Long et al. introduced the CCDCGAN model, which combines generative adversarial networks (GAN) with constrained feedback, enabling the generation of stable and synthesizable crystal structures20. Both methods demonstrate the potential of deep generative models to generate reasonable crystal structures. In spite of such exciting breakthroughs, it is noteworthy that these models address crystal invariance features through data augmentation strategies, which does not fully resolve the challenge of generating stable periodic structures. Most recently, Xie et al. proposed the Crystal Diffusion Variational Autoencoder (CDVAE), which successfully incorporates invariance neural networks to account for the invariance of crystal structures in terms of permutation, translation, rotation, and periodicity21. This innovative approach significantly enhances the generation and characterization capabilities for crystalline materials. However, existing deep generative models for materials often lack effective conditional guidance mechanisms when handling target-property constraints, resulting in structures that struggle to meet diverse functional requirements. Therefore, developing an efficient, stable, and flexible deep generative model for inverse design that can effectively incorporate target properties remains a significant challenge in the field of materials science.

In this study, we propose ConditionCDVAE+, an improved model based on CDVAE, specifically designed for the application scenario of inverse design of vdW heterostructures. The framework of the model is illustrated in Fig. 1. The model primarily consists of three components: a variational autoencoder (VAE) module, a diffusion module, and a conditional guidance module. To achieve improved generation performance, we employ EquiformerV222-based encoders and decoders in both the VAE and diffusion modules. Through this enhancement, ConditionCDVAE+ demonstrates superior reconstruction and generation performance compared to CDVAE on the Janus 2D III–VI van der Waals Heterostructures (J2DH-8) dataset23. Furthermore, we introduce a conditional guidance approach that combines Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN)24 and Low-rank Multimodal Fusion (LMF)25, enabling the generation of valid and diverse vdW heterostructures based on target properties, offering a novel solution to explore the vast material space of vdW heterostructures.

Results

This section demonstrates the inverse design performance of the ConditionCDVAE+ model on vdW heterostructures. Derived from CDVAE21, ConditionCDVAE+ employs the equivariant graph neural network EquiformerV222 as both the encoder and decoder, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to capture angular resolution and directional information. Moreover, ours model innovatively integrates LMF and GAN to achieve inverse design objectives. The detailed model architecture is described in the Methods section. This study compares ConditionCDVAE+ with four baseline models: (1) FTCP26, a general inverse design framework based on VAE that enables reversible representation of crystals through encoding real-space and reciprocal-space features; (2) CDVAE, which generates physically stable inorganic crystal structures through a diffusion process combined with periodic invariant graph neural networks; (3) DiffCSP27 an improvement upon CDVAE that synchronously generates lattice and fractional coordinates via a joint equivariant diffusion model, effectively handling the periodicity and symmetry of crystal structures; and (4) DP-CDVAE28, which incorporates a diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM)29 to generate crystal structures through an improved coordinate denoising process, resulting in structures that are closer to the ground state calculated by DFT.

We employed the Janus 2D III–VI van der Waals Heterostructures (J2DH-8) dataset to evaluate the model’s performance on vdW heterostructures. The J2DH-8 dataset was constructed by Sa et al. using the high-throughput first-principles calculation platform ALKEMIE30, which systematically generated 19,926 two-dimensional Janus III–VI vdW heterostructures by vertically stacking 45 types of III-VI monolayer materials (MX, MM\('\)X\(_2\), M\(_2\)XX\('\), and MM\('\)XX\('\), where M, M\('\) = Al, Ga, In and X, X\('\) = S, Se, Te) with various rotation angles and interlayer flip patterns23. To validate the generalizability of our model, we also conducted partial evaluations on the MP-2031 dataset. The MP-20 dataset encompasses a wide range of inorganic materials, including most of the experimentally discovered materials with less than 20 atoms in a unit cell. For both datasets, we adopted a 6:2:2 ratio for random partitioning into training, validation, and test sets.

Reconstruction performance

This section evaluates the ability of ConditionCDVAE+ to reconstruct crystal structures from its encoded latent vectors. We assess the reconstruction performance by comparing the similarity between the reconstructed structures decoded from the latent vectors and the ground-truth structures in the dataset. Similarity is calculated using the StructureMatcher algorithm from the pymatgen library32. The StructureMatcher algorithm performs Niggli reduction on the input pair of structures and then compares the lattice parameters and atomic positions. To ensure the rigorousness of the evaluation, we adopt the default settings from CDVAE21: stol=0.5, angle_tol=10, ltol=0.3. The match rate represents the percentage of reconstructed structures that meet the criteria. For matched structures, the normalized root mean square distance (RMSE) between paired atoms is calculated.

Table 1 presents the reconstruction performance of several models on the MP-20 and J2DH-8 datasets. As to J2DH-8 dataset, ConditionCDVAE+ achieves the best performance, with a match rate of 25.35% and an RMSE of 0.1842. Compared with FTCP, this model exhibits a slightly higher match rate and a significantly lower RMSE. When it comes to the comparison with CDVAE, ConditionCDVAE+ improves the match rate by 23% and reduces the RMSE by 13%. On the MP-20 dataset, ConditionCDVAE+ also achieves the best RMSE performance. The model demonstrates significant improvements in both match rate and RMSE, which can be attributed to the Attention Re-normalization mechanism in EquiformerV2, enabling more effective information aggregation when handling complex geometric structures22.

Generation performance

In order to evaluate the generative performance of the model, we adopted the assessment methodology from CDVAE. To be specific, Validity represents the percentage of generated materials that are valid. Structural validity is based on the criterion proposed by Court et al.33: a structure is considered valid if the minimum distance between any pair of atoms is greater than 0.5 Å. Compositional validity is determined by ensuring charge neutrality through SMACT34. COV evaluates the similarity between generated structures and ground-truth structures based on structural and compositional fingerprints35,36. COV-R represents the percentage of ground-truth structures covered by the generated structures, while COV-P indicates the percentage of high-quality structures generated (with thresholds for structural and compositional distances set at \(\delta struc.=0.4\) and \(\delta comp.=10\)). For detailed information, please refer to Fig. S1. Property measures the Wasserstein distance between the property distributions of generated structures and ground-truth structures, which quantifies the similarity between two probability distributions. Therefore, we specifically evaluate the structural density \(\rho\) (total atomic mass per volume) and the number of elements (\(\#elem.\)). Validity and COV are calculated based on 9,600 structures randomly sampled by the model, while Property is computed using 1,000 structures that pass the Validity test and selected at random in the meanwhile.

Table 2 shows that the ConditionCDVAE+ model achieves 100% Structure Validity and Composition Validity on the J2DH-8 dataset, performing comparably to CDVAE and slightly outperforming other baseline models. In terms of COV-R, ConditionCDVAE+ achieves the best performance along with other baseline models apart from excluding FTCP. For COV-P, ConditionCDVAE+ delivers the highest generation quality. In terms of the property metrics, although ConditionCDVAE+ is slightly underperforms CDVAE in \(\rho\), it shows significant improvement in (\(\#elem.\)). On the MP-20 dataset, ConditionCDVAE+ demonstrates convincing generalizability. Compared to CDVAE and CDVAE-based models, it exhibits similar performance and excels in property metrics.

DFT local optimizations performance

To validate the effectiveness of the generated structures, newly generated structures absent from the the training set are selected for DFT relaxation calculations. Verifying the proximity of the generated structures to the relaxed ground-state configurations is a key metric for evaluating model performance. Following the evaluation framework established by Luo37 and Pakornchote28, we adopted the following quantitative metrics: Convergence Rate, which refers to the percentage of structures successfully optimized by VASP, and Average Iteration Steps, which represents the average number of iterations required for the relaxation process to achieve energy convergence. Unreasonable atomic arrangements in the initial structures may cause divergence in the self-consistent field calculations, thus requiring more ionic relaxation steps to meet the convergence criteria. As shown in Table 3, ConditionCDVAE+ exhibits higher convergence rates and lower average iteration steps compared with the baseline CDVAE model. ConditionCDVAE+ also demonstrates excellent performance in terms of the average energy difference between the model-generated structures and their relaxed counterparts. Overall, the improved model generates structures that are closer to the ground state compared with those of CDVAE. Fig. 2 displays the stable configurations of 6 exemplary vdW heterostructures with negative formation energies after relaxation.

Given the substantial computational resources required for DFT calculations, this section merely uses CDVAE as the baseline model to validate the effectiveness of the improvements on the J2DH-8 dataset. The evaluation focuses on 400 randomly generated structures that are not present in the training set (The screened structures are not limited to those appearing in the test and validation sets). The screening process employs the StructureMatcher algorithm, where structures with an RMSD not less than 0.3 Å9 are considered potentially novel.

Inverse design performance

Based on the J2DH-8 dataset, ConditionCDVAE+ is trained using formation energy and chemical formula as independent guidance for the target-property guided generation of novel vdW heterostructures. Using formation energy as a guidance for inverse design significantly increases the probability of sampling candidate heterostructures with thermodynamic stability, thereby reducing the time cost in the inverse design process. The formation energies of the generated structures were predicted by CGCNN15 trained on J2DH-8. Fig. 3a shows the original formation energy distribution of the dataset and the distribution of randomly sampled structures without conditional training. The resemblance between the two distributions indicates that the model has learned the structure-property relationships in vdW heterostructures. In Fig. 3b, we used formation energies of -0.2 eV and 0 eV as conditional guidance for sampling and the results demonstrate significant changes in the formation energy distributions with the former shifts toward -0.2 eV and the latter shifts toward 0 eV. To accelerate the sampling of vdW heterostructures with desired stoichiometries, chemical formula guided sampling is performed as well. In Fig. 3c and d, we compared randomly generated structures with those generated from three different chemical formula. The results demonstrate that the conditionally guided model more readily samples vdW heterostructures with stoichiometries consistent with the input chemical formula, significantly accelerating the exploration of the vdW heterostructure material space with specific favored stoichiometry.

Formation energy and vdW heterostructures of randomly sampled and condition-guided structures. (a) The formation energy distribution of 9600 randomly sampled structures compared to the original dataset. (b) The formation energy distribution of 100 structures sampled under two formation energy conditions. (c) The vdW heterostructures distribution of 50 randomly sampled structures. (d) The vdW heterostructures distribution of 50 structures sampled restrained to three chemical formula conditions.

To validate the effectiveness of incorporating conditional information into the latent space via LMF under single guidance, we evaluated the changes in the latent space distribution under the conditions of formation energy and chemical formula. respectively. The mapping of latent vectors was conducted using t-SNE38 for two-dimensional visualization. In Fig. 4, (a) and (c) displays the results without feature fusion, while the (b) and (d) shows the results with feature fusion. As shown in Fig. 4 (a) and (b), in the latent space with feature fusion, structures with formation energy < 0 eV are distributed in the center, while those with > 0 spread toward the bottom-left and top-right, exhibiting an overall \(45^\circ\) symmetry. In Fig. 4 (c) and (d), a transition from disordered distributions to evident aggregation of heterostructures with the same chemical formula can be observed. This result demonstrates that LMF effectively clusters heterostructures with similar properties in the latent space, thereby enhancing the model’s conditional generation capability and accuracy.

Discussion

The ConditionCDVAE+ model proposed in this study demonstrates significant advantages in the inverse design of vdW heterostructures. By introducing EquiformerV2 as encoder and decoder , the model achieves significant reduction in RMSE regarding reconstruction performance, which directly reflects the enhanced representation capability for angular resolution and directional information. This is attributed to its equivariant feature processing mechanism based on irreducible representations22.

In terms of generation performance, the model demonstrated \(100\%\) structural and compositional validity on the J2DH-8 dataset, indicating that the generated vdW heterostructures satisfy fundamental physical stability requirements. The model not only demonstrated superior performance in terms of structural quality (COV-P) compared to baseline models, it also achieved comparable performance on the MP-20 dataset with property distribution \(\rho\) remains to be further optimized. DFT relaxation verification further confirmed the practical rationality of the generated structures, with a convergence rate of \(99.51\%\) and a lower average energy difference compared with CDVAE. The relatively fewer ionic steps indicate that the the model-generated structures are closer to the energy minima before relaxation, significantly reducing subsequent computational costs. In terms of inverse design performance, our conditional guidance module, combining LMF and GAN, achieved more precise target property constraints. Under single-condition guidance based on formation energy and chemical formula, the model achieved outstanding performance with desired structure generated in an orchestrated manner. Notably, due to the uneven distribution of formation energy in vdW heterostructures within the dataset, sampling in regions with more concentrated formation energy yields better performance compared to other regions. It is believed that supplementary dataset containing additional vdW heterostructures with diverse property data could further enhance model performance. Subsequently, we conducted an ablation study on single-property conditional guidance. By comparison with the latent vector distributions before and after feature fusion (as shown in Fig. 4), significant potential of the LMF module in constructing a property-structure joint latent space can be demonstrated. The methods and benchmarks introduced here will provide valuable references for future work in the field of vdW heterostructure inverse design and offer new approaches for functional material design.

Despite the fact that ours model delivered very promising results in inverse design of complex heterostructures, a few improvements can still be implemented in the future work. First, it is surprising that the model not only learn the atomic type relationship between M and X in III-VI monolayer materials and resulting vdW heterostructures, but also realized that generated vdW heterostructures with novelty should exhibit vacuum spaces to prevent interlayer bondings (as shown in Fig. 2). However, it is worth pointing out that current three-dimensional periodic modeling does not align well with structural characteristics of ‘semi-periodic’ vdW heterostructures. As a result, this mismatch leads to a small number of generated structures where the two single layers are significantly separated along the z-axis. Additionally, we observed that the model tends to generate structures with atomic substitutions and different rotation angles on the J2DH-8 dataset, which may be attributed to the limited structural diversity in the dataset. During the screening of novel heterostructures, we identified that while configurations recognized as “novel” by the StructureMatcher algorithm met the symmetry matching criteria, these structures occasionally maintained high similarity to existing configurations in terms of atomic stacking sequences and local bonding environments, which might lead to false identification of structural novelty. In future work, we plan to address this limitation by developing more robust feature matching methods. The evaluation of novelty is presented in Table S2. In the future, we plan to construct a vdW heterostructure dataset with more diversified heterostructures to further investigate the performance of the generative model. Second, the current conditional guidance is limited to single-property constraints, which rarely happens in the application of materials. On the contrary, multi-objective optimization capabilities require further exploration through Pareto frontier analysis to cope with more complex scenario39. While LMF feature fusion effectively aggregates latent space distributions, the ability to guide conditions for complex physical properties still requires further investigation. In the future, we will investigate how to perform periodic modeling tailored to ‘semi-periodic’ properties and introduce key properties such as absorption coefficient and bandgap as multi-objective conditional guidance to discover novel and stable vdW heterostructures.

Methods

NCSN diffusion model

Score-based generative models represent a significant approach within the realm of diffusion models. This methodology is rooted in the estimation and sampling of the Stein score associated with the logarithm of data density. Song and Ermon explored this novel principle in generative modeling and proposed an enhanced framework. The overarching strategy of the model involves estimating the gradient of the data density through score matching, followed by the generation of samples utilizing Langevin dynamics. During this process, challenges such as the manifold assumption and regions of low data density are addressed by perturbing the data with varying levels of Gaussian noise. A noise-conditioned score network (NCSN) is trained to jointly estimate the scores across all noise levels, thereby improving the model’s robustness and versatility40.

In the NCSN40 framework, adhering to the original design of CDVAE21, we established distinct sequences of progressively increasing standard deviations for both the fractional coordinates \(X\) and atom types \(A\), denoted as \(\{\sigma _X\}_{t=1}^{T_X}\) and \(\{\sigma _A\}_{t=1}^{T_A}\), respectively. This methodological approach facilitates the incorporation of Gaussian noise into the data in a structured manner.

In Eq. (1), \(p_{\text {comp}}\) denotes the one-hot encoding of the crystal chemical formula predicted by the Multilayer Perceptron \(MLP\). To estimate the scores of all perturbed data distributions, we train an equivariant graph network, \(s_x((X_t, A_t, L) \mid z_c; \sigma _A, \sigma _X)\), to minimize the Fisher divergence between the model and the data distributions, where \(z_c\) represents the latent vector after conditional feature fusion, and \(L\) signifies the lattice parameters of the crystalline structure..

During the reverse process, we iteratively denoise the coordinates of each atom towards their true values using the Langevin dynamics algorithm, and progressively update the atomic types to converge towards the authentic probability distribution.

In Eq. (2), the subscript of \(s_x\) denotes the specific component being predicted, while \(\eta _t\) represents the step size.

Equivariant graph neural networks

Equivariant graph neural networks (EGNNs) significantly improve model performance by preserving equivariance under geometric transformations of input data, such as rotations and reflections. Specifically, EGNNs formulate equivariant feature embeddings through irreducible representations (irreps). For the SE(3) group (encompassing three-dimensional rotations and translations), these equivariant features are mathematically formalized via Wigner-D matrices \(D^{(L)}(R)\), where the \(L\) corresponds to the angular momentum quantum number, which rigorously quantifies the angular momentum state of the system, and \(R\) denotes the rotation matrix within the SE(3) symmetry framework.

The proposed framework implements the EquiformerV2, an equivariant graph neural network, as both encoder and decoder. EquiformerV2 constitutes an enhanced equivariant Transformer model that integrates the attention mechanism of Transformers with principles of equivariance22, thereby incorporating geometric invariance under rotations and reflections of input data. Unlike Invariant graph neural networks employed in CDVAE (e.g., DimeNet++41 and GemNet-T42), which rely on invariant features for message passing, EquiformerV2 systematically constructs equivariant irreducible representations (irreps) from vector spaces of irreducible representations. Compared to other equivariant GNNs such as NequIP43, EquiformerV2 demonstrates enhanced scalability to higher values of \(L\), thereby facilitating the superior extraction of angular resolution and directional information. We compared the reconstruction performance of EquiformerV2 and NequIP, as shown in Table S1. This advancement significantly enhances the model’s capability to accurately predict both the magnitude and orientation of intermolecular forces during interaction computations.

To systematically explore the material space of vdW heterostructures with wide-ranging interlayer rotation angles, the selection of a high-performance encoder decoder holds critical significance for our investigation. Within the encoder design, node embeddings \(x_i''\), post processing through Transformer blocks, are projected into a latent vector via a Feed Forward Network (FFN). Notably, in the decoder architecture, the latent vector \(z_c\) serving as conditional prior knowledge is concatenated with atom embeddings \(x_i\) and edge degree embeddings \(d_{ij}\) and \(e_{ij}\), thereby enabling context-aware feature fusion for local geometric reconstruction.

In Eq. (3), \(D_{ij}^{-1}\) represents the inverse rotation matrix that restores computational results to the original coordinate system, while \(r_f\) denotes the scaling factor. Subsequently, The resulting node embedding \(x_i''\), derived from the summation of \(x_i'\) and \(e_i'\), is processed through Transformer blocks and subsequently bifurcated into dual prediction pathways: FFN dynamically refines the probability distribution of atomic types, and SO(2)-equivariant graph attention layer estimates noise scores for coordinate vectors.

ConditionCDVAE+

The transition from target properties to material structure and composition represents one of the critical steps in inverse design, where conditional guidance plays an indispensable role. To implement such guidance, we propose ConditionCDVAE+ through dual modifications to the original CDVAE21 architecture, with its training and generation workflow illustrated in Fig. 1. During the initial training phase, the model employs the LMF25 method to achieve feature fusion between target properties and latent vectors. This integration establishes a property-structure co-optimized latent space (visualized in Fig. 4). Following completion of preliminary model and LMF training, we introduce GAN – a module inspired by architectural principles from CVAE-GAN44 and LatentGAN45 – to generate initial latent vectors conditioned on target material properties. The proposed framework implements a dual-phase training regimen analogous to Con-CDVAE, wherein gradient clipping is first applied to stabilize parameter optimization during the model initialization stage46, followed by gradient penalty enforcement in subsequent iterations to maintain the discriminator’s compliance with K-Lipschitz continuity constraints47.

During the generation phase, random noise vectors are synthesized with conditional inputs through the generator to produce targeted latent vectors. These vectors subsequently undergo conditioning via LMF-mediated feature fusion, yielding property-informed latent representations with embedded prior constraints. Subsequently, the properties of the structures were predicted using MLP, implementing a 100 : 1 screening ratio to select optimal \({z}_c\) vectors demonstrating closest alignment with target properties. The decoder subsequently employs Langevin dynamics conditioned on \(z_c\) to iteratively refine atomic coordinates and elemental species, thereby yielding the final crystallographic configuration.

Low-rank multimodal fusion

Discrete attributes (e.g., atomic species) and continuous attributes (e.g., bandgap and formation energy) were subjected to distinct processing methodologies prior to feature fusion. Specifically, continuous attributes underwent expansion through Gaussian basis functions48.

In Eq. (4) The variable \(x\) represents the input properties, where \(\mu _j\) and \(\sigma _j\) denote the mean and standard deviation of the j-th Gaussian basis function, respectively. These parameters are typically initialized and optimized based on the underlying data distribution through iterative learning processes. Following this expansion, the transformed properties \(x_{expanded} = \left[ \phi _j(x)\right] _{j=1}^{N_j}\) emerge as a higher-dimensional representation determined by \(N_j\) Gaussian basis functions. Meanwhile, discrete attributes undergo transformation using embedding layers to obtain vector representations compatible with subsequent computational operations.

The LMF methodology was employed to integrate conditional vectors with latent vectors through feature fusion. Initially, the weight matrix \(W\) undergoes tensor decomposition into \(M\) modality-specific low-rank factors, where M denotes the number of modal. Each modality-adaptive feature matrix \(w_m\) manifests as

where \(R\) specifies the predefined rank, \(d_h\) denotes the desired output dimensionality and \(d_m\) corresponds to the input modality dimension25. Following the derivation of modality-specific feature matrices \(w_m\) associated with modality M, each modality undergoes dimensional augmentation through unitary padding with scalar unity, followed by performing an outer product operation on the latent vectors and property vectors to obtain \(Z\).

Ultimately, the tensor fusion process is performed like Eq. (6), yielding \(z_c\). We prioritize the training of LMF along with Encoder, Decoder, and MLP as the first step.

Generative adversarial networks

In the second step, we employ the Conditional Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (CWGAN-GP)49 to implement the GAN module. As illustrated in Fig. 1, this architecture consists of two neural networks trained in adversarial balance: the conditional generator G for latent vector generation and the discriminator D for authentic evaluation.

The generator G takes as input the concatenation of noise \(\tilde{z}\) and the conditional property \(c\), and consists of 5 hidden layers and 1 fully connected layer. The five sequentially connected hidden layers gradually expand the latent dimension from the original input size to 1,024 units, with each layer incorporating a leaky ReLU activation function50 and batch normalization. The discriminator, on the other hand, is composed of 3 hidden layers and 1 fully connected layer, with the hidden layers progressively increasing the unit dimension from the input size to 512 units, each equipped with a leaky ReLU activation function and Dropout51. The fully connected layers of both the generator and the discriminator do not include activation functions.

After the generator G produces the latent vector \({z}'\) based on the given conditional attribute \(c\), it concatenates \({z}'\) with the conditional property \(c\) and inputs it into the discriminator to obtain the authenticity score \(D(z' \mid c)\) of the generated latent vector; similarly, the authenticity score of the real latent vector is \(D(z \mid c)\). Based on this, the discriminator loss with gradient penalty can be derived as

In Eq. (7), \(\ \lambda\) is the weight coefficient for the gradient penalty, set to \(10\); \(\hat{z}\) is an interpolated sample between the real and generated samples; and \(\Vert \nabla _{\hat{z}} D(\hat{z} \mid c)\Vert _2\) represents the \(L_2\) norm of the gradient of the discriminator’s output with respect to its input. By penalizing deviations of this value from \(1\), it ensures that the discriminator’s gradients do not become excessively large, thereby improving training stability. The generator updates its parameters by minimizing \(\mathcal {L}_G = -\mathbb {E}_{\tilde{z} \sim P_g} [D(G(\tilde{z} \mid c) \mid c)]\) to produce samples that are closer to real data. The model employs the asynchronous update strategy from Wasserstein GAN52 for training, where the discriminator parameters are updated five times for each generator iteration. Both networks are trained using the Adam optimizer53, with initial learning rates set to \(0.0002\) for both, and \(\beta _1\) and \(\beta _2\) set to \(0.5\) and \(0.999\), respectively. During training, the same Learning Rate Scheduler as in Step One is used, reducing the learning rate to \(0.6\) times its original value if no improvement in loss is observed after \(30\) iterations. The minimum learning rate is set to \(0.00001\).

DFT calculations

The DFT calculations are based on the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)54, employing the Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) method55. The exchange-correlation functional is chosen as the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional within the framework of the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA)56. During the self-consistent calculations, the convergence thresholds are set to \(10^{-6}~\text {eV}\) for energy and \(0.05~\text {eV} \cdot \text {\text{\AA }}^{-1}\) for interatomic forces. The cutoff energy for the plane-wave basis set is uniformly set to 550 \(eV\). To address the limitations of traditional DFT in describing long-range van der Waals interactions, this study incorporates the zero-damping form of the DFT-D3 dispersion correction method57.

Data availibility statement

The code is available on Github: https://github.com/GaoShikun/ConditionCDVAEplus. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1102896 (2004).

Choi, J. R. et al. Black phosphorus and its biomedical applications. Theranostics 8, 1005–1026. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.22573 (2018).

Naclerio, A. E. & Kidambi, P. R. A review of scalable hexagonal boron nitride ( h -BN) synthesis for present and future applications. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207374. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202207374 (2023).

Deng, D. et al. Catalysis with two-dimensional materials and their heterostructures. Nature Nanotechnol. 11, 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.340 (2016).

Novoselov, K. S., Mishchenko, A., Carvalho, A. & Castro Neto, A. H. 2D materials and van der Waals heterostructures. Science 353, 9439 (2016).

Zhou, J. et al. 2DMatPedia, an open computational database of two-dimensional materials from top-down and bottom-up approaches. Sci. Data 6, 86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0097-3 (2019).

Mounet, N. et al. Two-dimensional materials from high-throughput computational exfoliation of experimentally known compounds. Nature Nanotechnol. 13, 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-017-0035-5 (2018).

Haastrup, S. et al. The computational 2D materials database: High-throughput modeling and discovery of atomically thin crystals. 2D Materials 5, 042002 (2018).

Lyngby, P. & Thygesen, K. S. Data-driven discovery of 2D materials by deep generative models. NPJ Comput. Mater. 8, 232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-022-00923-3 (2022).

Linghu, J. et al. High-throughput computational screening of vertical 2D van der Waals heterostructures for high-efficiency excitonic solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 32142–32150. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b09454 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Design and analysis of III-V two-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures for ultra-thin solar cells. Appl. Surface Sci. 586, 152799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.152799 (2022).

Nitika Arora, S. & Ahlawat, D. S. High-throughput screening on optoelectronic properties of two-dimensional InN/GaN heterostructure from first principles. J. Mol. Model. 30, 318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00894-024-06121-w (2024).

Hua, L. & Li, Z. Ideal vacuum-based efficient and high-throughput computational screening of Type II heterojunctions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.3c11082 (2023).

Choudhary, K. & DeCost, B. Atomistic line graph neural network for improved materials property predictions. NPJ Comput. Mater. 7, 185. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00650-1 (2021).

Xie, T. & Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 145301. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.145301 (2018).

Willhelm, D. et al. Predicting Van der Waals heterostructures by a combined machine learning and density functional theory approach. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 25907–25919. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c04403 (2022).

Nair, A. K., Da Silva, C. M. & Amon, C. H. Machine-learning-derived thermal conductivity of two-dimensional TiS2/MoS2 van der Waals heterostructures. APL Machine Learn. 2, 036115. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0205702 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Generative artificial intelligence and its applications in materials science: Current situation and future perspectives. J. Materiomics 9, 798–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmat.2023.05.001 (2023).

Noh, J. et al. Inverse design of solid-state materials via a continuous representation. Matter 1, 1370–1384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matt.2019.08.017 (2019).

Long, T. et al. Inverse design of crystal structures for multicomponent systems. Acta Mater. 231, 117898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2022.117898 (2022).

Xie, T., Fu, X., Ganea, O.-E., Barzilay, R. & Jaakkola, T. S. Crystal diffusion variational autoencoder for periodic material generation. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2022).

Liao, Y.-L., Wood, B. M., Das, A. & Smidt, T. Equiformerv2: Improved equivariant transformer for scaling to higher-degree representations. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (2024).

Sa, B. et al. High-throughput computational screening and machine learning modeling of Janus 2D III-VI van der Waals heterostructures for solar energy applications. Chem. Mater. 34, 6687–6701. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c00226 (2022).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 63, 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1145/3422622 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Efficient Low-rank Multimodal Fusion With Modality-Specific Factors. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2247–2256, https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P18-1209 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 2018).

Ren, Z. et al. An invertible crystallographic representation for general inverse design of inorganic crystals with targeted properties. Matter 5, 314–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matt.2021.11.032 (2022).

Jiao, R. et al. Crystal structure prediction by joint equivariant diffusion. In Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (2023).

Pakornchote, T. et al. Diffusion probabilistic models enhance variational autoencoder for crystal structure generative modeling. Sci. Reports 14, 1275. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51400-4 (2024).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (Curran Associates Inc., 2020).

Wang, G. et al. ALKEMIE: An intelligent computational platform for accelerating materials discovery and design. Comput. Mater. Sci. 186, 110064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.110064 (2021).

Jain, A. et al. Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 1, 011002. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4812323 (2013).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): A robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2012.10.028 (2013).

Court, C. J., Yildirim, B., Jain, A. & Cole, J. M. 3-D inorganic crystal structure generation and property prediction via representation learning. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 60, 4518–4535. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00464 (2020).

Davies, D. et al. SMACT: Semiconducting materials by analogy and chemical theory. J. Open Source Software 4, 1361. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01361 (2019).

Xu, M., Luo, S., Bengio, Y., Peng, J. & Tang, J. Learning neural generative dynamics for molecular conformation generation. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2021).

Ganea, O. et al. Geomol: Torsional geometric generation of molecular 3d conformer ensembles. In Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P. & Vaughan, J. W. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 34, 13757–13769 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2021).

Luo, X. et al. Deep learning generative model for crystal structure prediction. NPJ Comput. Mater. 10, 254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-024-01443-y (2024).

van der Maaten, L. & Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Machine Learn. Res. 9, 2579–2605 (2008).

Momma, M., Dong, C. & Liu, J. A multi-objective / multi-task learning framework induced by pareto stationarity. In Chaudhuri, K. et al. (eds.) Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning, vol. 162 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 15895–15907 (PMLR, 2022).

Song, Y. & Ermon, S. Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution. In Wallach, H. et al. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 32 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2019).

Gasteiger, J., Giri, S., Margraf, J. T. & Günnemann, S. Fast and Uncertainty-Aware Directional Message Passing for Non-Equilibrium Molecules (In Machine Learning for Molecules Workshop, NeurIPS, 2020).

Klicpera, J., Becker, F. & Günnemann, S. GemNet: Universal Directional Graph Neural Networks for Molecules. In Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P. & Vaughan, J. W. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2021).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-Equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nature Commun. 13, 2453. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29939-5 (2022).

Bao, J., Chen, D., Wen, F., Li, H. & Hua, G. CVAE-GAN: Fine-Grained Image Generation through Asymmetric Training. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2764–2773, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2017.299 (IEEE, Venice, 2017).

Prykhodko, O. et al. A de novo molecular generation method using latent vector based generative adversarial network. J. Cheminform. 11, 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-019-0397-9 (2019).

Ye, C.-Y., Weng, H.-M. & Wu, Q.-S. Con-CDVAE: A method for the conditional generation of crystal structures. Comput. Mater. Today 1, 100003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commt.2024.100003 (2024).

Gulrajani, I., Ahmed, F., Arjovsky, M., Dumoulin, V. & Courville, A. C. Improved training of wasserstein gans. In Guyon, I. et al. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 30 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Gebauer, N. W. A., Gastegger, M., Hessmann, S. S. P., Müller, K.-R. & Schütt, K. T. Inverse design of 3d molecular structures with conditional generative neural networks. Nature Commun. 13, 973. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28526-y (2022).

Zheng, M. et al. Conditional Wasserstein generative adversarial network-gradient penalty-based approach to alleviating imbalanced data classification. Inform. Sci. 512, 1009–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2019.10.014 (2020).

Maas, A. L., Hannun, A. Y., Ng, A. Y. et al. Rectifier nonlinearities improve neural network acoustic models. In Proc. icml, vol. 30, 3 (Atlanta, GA, 2013).

Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1929–1958 (2014).

Adler, J. & Lunz, S. Banach wasserstein gan. In Bengio, S. et al. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 31 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2018).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. CoRR abs/1412.6980 (2014).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/0927-0256(96)00008-0 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. The J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3382344 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 2024NSFSC0137).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. developed methodology into the code. S.G., Q.H., C.L., D.X., Z.L., and M.D. conceived the research and designed its implementation. C.H., B.S., and Y.Y. constructed the dataset and performed DFT relaxation. S.G. and K.L. implemented model evaluation and analyzed results. S.G. and Z.L. wrote the paper. Q.H., Z.L., and M.D. supervised the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, S., Huang, Q., Huang, C. et al. Deep generative model for the inverse design of Van der Waals heterostructures. Sci Rep 15, 23023 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06432-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06432-9

This article is cited by

-

Accelerating the search for carbon cluster isomers via machine learning potential

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2026)

-

Generative AI for crystal structures: a review

npj Computational Materials (2025)