Abstract

Copy number variation (CNV) plays an important role in disease susceptibility as a type of intermediate-scale structural variation (SV). Accurate CNV detection is crucial for understanding human genetic diversity, elucidating disease mechanisms, and advancing cancer genomics. A variety of CNV detection tools based on short sequencing reads from next-generation sequencing (NGS) have been developed. Although many researchers have conducted extensive comparisons of the detection performance of various tools, these studies have not fully considered the comprehensive impact of factors such as variant length, sequencing depth, tumor purity, and CNV types on tools performance. Therefore, we selected 12 widely used and representative detection tools to comprehensively compare their performance on both simulated and real data. For the simulated data, we compared their performance across six variant types under 36 configurations, including three variant lengths, four sequencing depths, and three tumor purities. For the real data, we used the overlapping density score (ODS) to evaluate the performance of the 12 detection tools. Additionally, we compared their time and space complexities. In this study, we analyzed the impact of each configuration on the tools and recommended the most suitable detection tools for each scenario. This study provides important guidance for researchers in selecting the appropriate variant detection tools for complex situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Copy number variation (CNV) is a form of structural variation (SV) in DNA sequence, including gains and losses of gene copies1. The CNV’s length is typically greater than 1 kilobase (Kb) and less than 5 megabases (Mb)2. CNV is recognized as major genetic factors underlying human diseases, with direct consequences for human health and genetic variations. Moreover, CNV may account for 13% of the human genome3,4, and they accounted for 4.7–35% of pathogenic variants depending on clinical specialty5. Therefore, CNV detection is crucial for understanding human genetic diversity, uncovering disease mechanisms, and advancing cancer diagnosis, treatment, and personalized medicine6,7.

With the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS)8,9, various sequencing-based CNV detection tools have been proposed. CNV detection tools can be divided into two categories based on their detection focus: specialized CNV tools and general SV tools, the latter of which can also detect CNV. According to the methods used, these tools can be divided into five categories10: read depth (RD)11, pair end mapping (PEM)12, split reads (SR)13, assembly (AS)14,15 and combinations of the above methods16. Moreover, most of the specialized CNV tools use methods based on read depth, such as CNVkit17, CNVnator18 and Readdepth19. SV tools employ a wider range of strategies. For example, Delly20 uses PEM and SR strategies for SV detection, while LUMPY21 and TARDIS22 use PEM, SR, and RD.

At present, numerous CNV detection tools have been utilized in clinical diagnostics. Many researchers have conducted extensive comparative studies to help others choose the most suitable tools for their goals. Shunichi Kosugi’s team has evaluated 69 SV algorithms23, and Daniel L. Cameron’s team has tested 10 SV algorithms for whole genome sequencing24. However, these studies are comprehensive analyses and comparisons of SV tools and do not specifically focus on CNV research. Lanling Zhao’s team has evaluated 4 popular CNV tools25, Fatima Zare’s team has tested 6 somatic tools26, and Ruen Yao’s team has evaluated three RD-based CNV detection tools27. But they are based on whole exome sequencing, not whole genome sequencing, and the tools they used to compare are based on RD strategy. Le Zhang’s team has compared 10 commonly used CNV detection tools28, and José Marcos Moreno-Cabrera’s team has tested 5 CNV calling tools on targeted NGS panel data29. But these tools do not distinguish between single-sample detection and dual-sample detection with a control sample. They evaluated tools using different numbers of samples in the same analysis, which may lead to biased comparisons. However, multiple samples or a suitable control sample are often not available. Ke Lin’s team has evaluated the impact of different detection signals on variant detection10, and Yibo Zhang’s team has compared the performance of those two core segmentation algorithms in detecting CNV30. But they are not evaluating the performance of detection tools in practical applications. To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive comparative study exists on CNV detection tools for single-sample whole-genome sequencing data. These studies did not consider the comprehensive impact of variation length, sequencing depth, and tumor purity on detection performance. In CNV detection, shorter variants may be overlooked or filtered out, whereas longer variants are more readily detected. At the same time, factors such as the quality of sequencing data and tumor purity may influence the detection results. Tumor purity refers to the proportion of cancerous cells present within a heterogeneous tumor sample31. It is significantly associated with clinical features, gene expression, and tumor biology; tumor purity greatly impacts the accuracy and reliability of CNV detection. In the absence of normal sample controls, tumor samples with low purity can cause signal confounding, affecting CNV detection results32. More importantly, there is currently no comparison of CNV detection tools for different types, such as tandem duplications, interspersed duplications, inverted tandem duplications, inverted interspersed duplications, heterozygous deletions, and homozygous deletions33,34. To address this issue, we conducted a comprehensive comparison of 12 representative CNV detection tools using whole genome sequencing.

No single method is suitable for all data sets, so it is essential to analyze and study these tools, each with its own characteristics and advantages. Considering factors such as public availability, implementation stability, and ease of use, there are 12 popular and representative tools, including Breakdancer35, CNVkit17, Control-FREEC36, Delly20, LUMPY21, GROM-RD37, IFTV38, Manta39, Matchclips240, Pindel41, TARDIS22, and TIDDIT42,that were selected for assessment and comparison. They do not require multiple samples, such as control and tumor samples. The detailed information of these 12 CNV detection tools is given in Table 1. In addition, it should be noted that our analysis and comparison are based on the latest reference genome, the GRCh38 series. We did not compare such tools as Readepth19, iCopyDAV43, rdxplorer44, etc., because they cannot use GRCh38 as the reference genome and can only use the reference genome of GRCh37. Similarly, WisecondorX45 utilizes multi-sample detection, while CuteSV46, SVIM47, and Sniffles48 are SV detection tools developed based on third-generation sequencing data. We compare the performance of detection tools based on next-generation sequencing in single-sample analysis. We evaluated the performance of these tools on simulated and real data. For the simulated data, we comprehensively evaluated the algorithm from four aspects: Precision, Recall, F1_score, and Boundary Bias (BB). These evaluation metrics are commonly utilized across various domains of machine learning and deep learning49,50,51. To ensure more comprehensive and objective comparison results, we tested three CNV lengths and four sequencing depths. In addition, tumor purity is a fundamental property of a cancer sample and affects CNV investigations52,53. We also assessed the tools’ detection performance at different tumor purities. For real data, we evaluated the performance with the Overlapping Density Score (ODS)54, and showed the distribution of CNV detected by the 12 tools across the 22 autosomes for each real data using a chord diagram. Additionally, we also compared the time and space complexity of these tools during detection. By comparing the performance of these tools, we highlight their limitations and advantages and provide recommendations, helping researchers choose the most suitable CNV detection tools for their goals. The installation and usage methods of 12 detection tools are shown in Supplementary Material 1.

Materials and methods

Materials

We selected 12 easy-to-use and publicly available CNV detection tools that are based on NGS data. For these 12 detection tools, we evaluated their performance for single-sample detection. After aligning the short sequences to the human reference genome, using the detection tools, the corresponding detection results can be obtained. The reference genome we used is GRCh38, which can be downloaded from The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

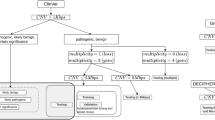

In order to comprehensively evaluate the performance of these 12 CNV detection tools, we compared them using simulated and real data. In the simulation experiment, we used Seqtk V1.0 (https://github.com/lh3/seqtk) and Sinc V2.0 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/sincsimulator/)55 to simulate the data56. Seqtk is a fast and lightweight tool for processing sequences in FASTA or FASTQ format. SInC is an accurate and fast error-model based simulator for SNPs, Indels, and CNVs coupled with a read generator for short-read sequence data. SInC performs two jobs; first it simulates variants (simulator) and then it generates reads (read generator). It is capable of generating single- and paired-end reads with user-defined insert size and with high efficiency compared to the other existing tools. SInC simulator consists of three independent modules (one each for SNV, indel, and CNV) that can either be executed independently in a mutually exclusive manner or in any combination55. SInC includes three files, each serving a distinct function: genProfile, which generates a quality profile from the desired input file; SInC_simulate, which simulates three different variants; and SInC_readGen, which uses paired-end sequencing to simulate the sequencer and generate FASTQ files. Seqtk can be used to set the tumor purity in the simulation data, while SInc_readGen is used to simulate the sequencing depths in the simulation data. We set up simulation experiments with three different parameters, including three different CNV variant lengths (1 K–10 K, 10 K–100 K, 100 K–1 M), four different sequencing depths (5x, 10x, 20x, 30x), and three different tumor purities (0.4, 0.6, 0.8). Genomic rearrangements, which include large deletions, duplications, insertions, chromosomal translocations, and chromosome gain or loss caused by mitotic non-disjunction lead to CNV57. This also contributes to the complexity of CNV. In order to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of CNV detection tools, we also considered six different types of CNV, including tandem duplications, interspersed duplications, inverted tandem duplications, inverted interspersed duplications, heterozygous deletions, and homozygous deletions. Tandem duplication refers to the repeated occurrence of a DNA sequence in the genome, arranged consecutively in a head-to-tail manner. Interspersed duplications refer to repeated DNA sequences that are dispersed across the genome and appear multiple times, although the size of the repeated fragments may vary. Inverted duplications refer to a sequence where the direction of the repeat is opposite to that of the original, typically forming an inverted symmetric structure. For homozygous deletions, we set the copy number of both chromosomes to zero. In the case of heterozygous deletions, we set the copy number of one chromosome to zero, while the copy number of the other chromosome remains unchanged. Figure 1 shows simple examples of the six CNV types to help more intuitive understanding of their characteristics and differences. To ensure the accuracy of the simulation results, we combined three variant lengths, four sequencing depths, and three tumor purities, resulting in a total of thirty-six experimental conditions. Under each condition, we generated 50 sets of duplicate samples to minimize the impact of random error. When evaluating the detection results of simulated data, we used F1_score and Boundary Bias (BB) as evaluation indicators. Through these comprehensive experimental settings and precise evaluation methods, we can effectively compare the performance of detection algorithms in different situations.

For real data analysis, we downloaded data from The International Genome Sample Resource (https://www.internationalgenome.org/), including samples from a family of three members of the Yoruba in Ibadan: mother NA19238, father NA19239, and daughter NA19240. Additionally, we obtained HG002 from NCBI, a real sample from a Jewish family. To evaluate the detection results of real data, we used the Overlap Density Score (ODS)38,54,58 and compared the time complexity and space complexity23. To visually demonstrate the detection performance of each tool in real data, we use chord diagrams to display the number of bases detected by all tools in each real sample. For the detection results of the real sample HG002, we used the ground truth of CNV obtained from the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB, https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/genome-bottle) as a reference to calculate Precision, Recall, and F1_score. We evaluated the performance of the detection tools by comparing the above indicators.

Performance evaluation criteria

In the simulation experiment, we set three different variant lengths, four sequencing depths, and three tumor purities, resulting in a total of 36 different setups. For each setup, we generated 50 groups of random data to reduce the likelihood of experimental errors. After obtaining the simulated data, we used BWA V0.6 (https://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/)59,60,61 and Samtools V1.4 (https://samtools.sourceforge.net/)62,63 with their default settings to produce the aligned BAM file. Subsequently, the BAM file was sorted by the genome position using Samtools, which can be used by CNV detection tools. By analyzing CNV detection results in different configurations, we can better evaluate their performance under different situations. This evaluation will enable us to understand the advantages and limitations of different tools, offering valuable insights for future research endeavors.

We used Precision, Recall, F1_score and Boundary Bias (BB) as performance evaluation criteria64,65. Precision is an indicator to measure the accuracy of the method’s prediction results. It is defined as the proportion of the number of positive samples correctly predicted by the method to the total number of positive samples predicted. Precision refers to the ratio of the number of correct CNVs detected to the total number of all CNVs detected. Due to the wide range of copy number variations and the long length of variations, we have redefined the concept of true positives and false positives in order to reduce computational complexity and improve result accuracy. In our study, a detected CNV is considered a true positive (TP) if it overlaps with at least 50% of the length of a ground truth CNV region and the CNV types match. Notably, this is a one-sided overlap criterion: we only require that the predicted CNVs spans at least 50% of the corresponding ground truth CNVs, regardless of whether the ground truth CNVs also span 50% of the predicted region. This approach accounts for boundary imprecision commonly observed in CNV detection tools and allows partial but meaningful overlaps to be counted as valid detections. Predicted CNVs that do not satisfy this overlap requirement with any ground truth CNVs of the same type are classified as false positives (FP). Any portion of the standard CNV region that is not detected is categorized as a false negative (FN)38. Precision can be expressed as in Formula (1). The sum of TP and FP represents the positives detected by the detection tool.

Recall is an indicator that measures the completeness of method prediction results. It is defined as the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples to all true positive samples. Recall can be expressed as in Formula (2). The sum of TP and FN in the formula represents the total number of CNVs in the ground truth.

F1_score is an indicator used to measure the accuracy of classification models. It considers both the accuracy and recall of the classification model. The F1_score can be viewed as a harmonic mean of model precision and recall, with higher values indicating better model performance. F1_score can be expressed as in Formula (3).

Boundary bias (BB)66 is also an important indicator for measuring the reliability of CNV detection tools. The BB in CNVs is defined as the deviation of the detected CNVs region from the ground truth. It can be calculated by Formula (4). Here, i represents the i-th detected true positive CNVs, and n represents the total number of detected true positive CNVs. Ri_s denotes the starting position of the CNVs in the ground truth, while Di_s indicates the starting position of the true positive CNVs in the detection results. Ri_e denotes the ending position of the CNVs in the ground truth, while Di_e indicates the ending position of the true positive CNVs in the detection results. The smaller the BB, the higher the performance of the CNVs detection method.

The overlapping density score measures the overlap between bases detected by a specific tool and those identified by others. Formula (5) shows the calculation method for the ODS. In this formula, Ns represents the average overlap between one method and others, while Np represents the ratio of the average overlap to the total number of calls made by the method. SUMoverlap represents the total length (in bases) of the overlapping CNVs regions between this tool and the others. CNVcalled represents the total number of CNVs bases detected on a chromosome by this tool. Num represents the number of additional tools needed to compare CNVs overlap density. In Formula (5), Num is set to 11.

Comparison results

Comparison under different CNVs lengths

In tumor genetics, cancer is often caused by multiple factors. In cancer genetics, CNVs are divided into two categories based on their size: small-scale variations, which typically do not exceed 3 MB in length, and large-scale variations, also known as chromosome arm level variants encoding > 25% or 1/3 of the chromosome arm67,68. In CNVs detection, sequencing data can be influenced by noise or other factors, making it difficult to detect shorter variant fragments. Longer variant fragments are more stable, leading to more reliable detection results.

To simulate variation complexity69, we defined three length ranges in the experiment: 1 K–10 K, 10 K–100 K, and 100 K–1 M70. Different variant lengths resulted in different detection performance across various tools. In the simulation data with variant lengths ranging from 1 K to 10 K, the CNV detection performance is not as good as in the other two groups due to the shorter length of the variants. For the 10 K–100 K sample data, the F1_scores of Control-FREEC, GROM-RD, IFTV, and Pindel outperform those in the other two variant length groups. This is because their model parameter settings are better suited for detecting medium-length variants. In the 100 K–1 M sample data, tools such as Breakdancer, CNVkit, Delly, LUMPY, Manta, Matchclip2, and TIDDIT have demonstrated better F1_scores in detecting CNVs. Their detection effectiveness improves as the variant length increases, since smaller variant fragments are more likely to be overlooked. The TARDIS algorithm performed equally well on 1 K–10 K and 10 K–100 K samples, but its performance was not as strong on the 100 K–1 M samples. As the mutation length increases, CNV detection performance improves. However, GROM-RD is most suitable for detecting mutations between 1 K and 100 K in length. Its detection performance decreases when the variation length exceeds this range.

Under the same environmental configuration, each detection tool has its own advantages and disadvantages in terms of performance. In Tables 2, 3, and 4, we list the detection tools with the highest F1_scores across different combinations of variant length, sequencing depth, and tumor purity. As shown in the tables, Delly and Breakdancer exhibit superior detection performance compared to other tools when the variation length is between 1 K and 10 K. For CNVs variation lengths ranging from 10 K to 100 K, Control-FREEC, IFTV, and GROM-RD demonstrate excellent detection performance. When the mutation length exceeds 100 K, multiple detection tools show significant performance due to tumor purity and sequencing depth influences, with the F1 score of Breakdancer significantly surpasses that of other tools. The detailed results of the Precisions, Recalls and F1 scores of all detection tools are shown in Supplementary Material 2.

Comparison under different sequencing depths

According to Illumina (https://www.illumina.com/science/technology/next-generation-sequencing/plan-experiments/coverage.html), the sequencing coverage level often determines whether variant discovery can be made with a certain degree of confidence at particular base positions. Sequencing depth refers to the ratio of the total base number obtained by sequencing to the size of the genome to be the subject. That is, the average number of times each base in the genome is measured71,72. As sequencing depth increases, both time and spatial costs rise. Therefore, it is necessary to detect data at different sequencing depths to evaluate the performance of 12 detection tools and compare the advantages of these tools at the same sequencing depth.

For the sample data in the simulation experiment, we set four different sequencing depths: 5x, 10x, 20x, and 30x73. Through the detection of sample data under different sequencing depths, the impact of sequencing depth on detection tools can be analyzed. As shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4, the F1_scores of Breakdancer, Matchclips2, Delly, and LUMPY increase as sequencing depth increases. The F1_score of Control-FREEC decreases as sequencing depth increases, but the change is minimal. The F1_score of GROM-RD reduces, but it is also influenced by tumor purity. Its detection performance improves with higher tumor purity. Manta, LUMPY, and TIDDIT perform better with a sequencing depth of 10x. Matchclips2 performs poorly at 5x, and effective results cannot be obtained. As sequencing depth increases, the detection performance of Matchclips2 gradually improves. Pindel and TARDIS are significantly influenced by sequencing depth, performing best at 30x compared to other depths. In Supplementary Material 3, we demonstrate the changes in detection performance of each tool under various sequencing conditions.

Comparison under different tumor purities

Tumor purity refers to the proportion of tumor cells in a sample to all cells54. Because it is difficult to ensure that all cells collected from real samples are tumor cells, the presence of normal somatic cells may interfere with subsequent analyses52. In the case of tumor analysis, the genotyping of an allele needs to be independent of the native human ploidy expectation. Genotyping is difficult in tumors. We set the purity of the tumor through Seqtk in the simulation experiment. The higher the purity of the tumor, the larger the proportion of tumor cells, making it easier to detect tumor variants. As tumor purity improves, the detection performance also increases. In the simulation experiment, three kinds of tumor purity were set: 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8. Figure 5 shows the F1_scores under different tumor purities with the same variant lengths and sequencing depths.

From the figure at a sequencing depth of 5x, we can clearly see that as tumor purity increases, the detection performance of the tools improves. Since detection performance is easily influenced by sequencing depth and tumor purity, tumor purity becomes a crucial factor affecting performance when sequencing depth is low. From the figure, at a sequencing depth of 10x, the performance of detection tools also improves, but the change in performance of some tools is not as noticeable as that at 5x sequencing depth. From Fig. 5, we observe that at a sequencing depth of 5x, the detection performance of Breakdancer, Delly, and IFTV shows noticeable changes with increasing tumor purity. However, as sequencing depth increases, the impact of tumor purity on their performance gradually decreases. The detection performance of CNVkit is also influenced by variation length. Specifically, when variation length ranges from 1 K to 10 K or 100 K to 1 M, CNVkit’s detection performance improves as tumor purity increases. Matchclips2 is primarily influenced by tumor purity, and its detection performance improves as tumor purity increases. For GROM-RD within the effective detection range, tumor purity plays a key role in performance. Notably, at a tumor purity of 0.8, GROM-RD’s detection performance outperforms the other two purity groups.

Comparison under different CNVs types

Cancers are characterized by the accumulation of mutations in coding and regulatory gene regions, changes in gene expression, and structural genomic rearrangements. Genomic rearrangements, which include large deletions, duplications, insertions, chromosomal translocations, and chromosome gain or loss caused by mitotic non-disjunction led to CNV74. Nowadays, it is no longer difficult to identify and characterize the genome, and the diversity of variations is an important part of genome analysis75. In the simulation experiment, we set up six different types of variation, including tandem duplication, interspersed duplication, inverted tandem duplication, inverted interspersed duplication, homozygous deletion, and heterozygous deletion23. We hope to see the detection performance of each tool through various variant types.

At Fig. 6, we list the number of different CNV types detected by various tools. The primary types of CNV that have been detected by these tools include duplication, deletion, insertion, and inversion. From Fig. 6, we can see that Pindel and TARDIS have many types of detections. From their introductions, we can learn that Pindel can detect breakpoints of large deletions, medium-sized insertions, inversions, tandem duplications, and other structural variants. And TARDIS can detect tandem, direct, and inverted interspersed segmental duplications. Other tools to detect variant types mainly include tandem duplication (DUP) and deletion (DEL).

In Fig. 7, we show the true and false positives from all detection results. It is evident that the number of true positives significantly exceeds the number of false positives for most detection tools. Only GROM-RD and Pindel report more false positives than true positives. This discrepancy may be attributed to the dataset used in the detections and the evaluation criteria employed. Specifically, for GROM-RD, a minimum of 10% reciprocal overlap between a predicted CNV and a simulated CNV is required to classify a result as a true positive. In our study, we assert that detection results can only be classified as true positives when they overlap with CNVs in the ground truth by at least 50%. In contrast, our evaluation criteria are more stringent. In Pindel’s experiment, they simulated 30x coverage of 36 BP paired-end short reads with an average insert size of 200, whereas we set the average insertion length to range from 5000 to 500,000. This difference in parameters can significantly impact the detection results.

Comparison under Boundary Bias (BB)

In CNV detection, there are still considerable challenges in accurately identifying CNV. How to accurately identify CNV and determine breakpoints is also a problem that each detection tool should consider. In the simulation experiment, we calculated the BB between the detection result of the detection tool and ground truth. The smaller the BB, the more accurate the detection performance. When the variation length is 1 K–10 K, the BB of 12 detection tools are shown at Fig. 8.

As shown at Fig. 8, when the variation length is less than 10 K, LUMPY and Matchclips2 show excellent results, and their BB not exceeding 2000. With the increase in sequencing depth, the detection performance of Breakdancer, Delly, Manta, and Matchclips2 becomes more stable. The significant gap in BB is also narrowing, indicating that the increase of sequencing depth benefits CNV detection using these tools. However, Control-FREEC, IFTV, and Pindel exhibit relatively large BB, with values reaching tens of thousands. The detection performance of CNVkit is not stable, leading to extreme differences in BB.

Comparison under real data

In order to evaluate the detection performance of the tool in real data, we used the real data of a three-member family (NA19238, NA19239, NA19240) of the Yoruba in Ibadan from The International Genome Sample Resource and the real data of a single Jewish family (HG002) in the NCBI. The reference genome version corresponding to NA19238 is GRCh38, and the reference genome version corresponding to HG002 is GRCh37.

In order to directly observe the detection performance of each detection tool in real data, we draw a chord graph for the detection results of each tool. As shown at Figs. 9, 10, 11, and 12, the upper part of the circle represents 12 detection tools, while the lower part represents chr1 to chr22. Each arc in the graph represents the total number of CNVs bases detected. From these figures, it is evident that Delly detected the greatest number of CNVs in the real data. The results of other detection tools in the Yoruba people don’t change significantly. In HG002, the number of CNVs detected by Delly remains the most. We used an UpSet plot to illustrate the relationship between the detection results for chromosome 22 in HG00276,77. Figure 13 clearly shows that only a small portion of the detection results are relevant, while the majority are unrelated. From the figure, we can observe that Lumpy and Tardis show the strongest association, with 22 CNVs overlapping in their detection results.

For the performance of real data detection, we use the Overlap Density Score (ODS) to evaluate the detection performance. The ODS values of 12 detection tools are shown at Fig. 14. The higher the ODS, the greater the consistence between the detection results of detection tools and other tools, and the better the detection performance. According to Fig. 14, in the CNVs detection of three Yoruba people, Pindel’s detection results exhibit the highest ODS compared to other detection tools, as identified a greater variety of more CNV types. Pindel classified CNVs into nine different variant types, enhancing the comprehensiveness of the detection results. Compared to other tools, the detection performance of TARDIS is lower. However, we think it is important to consider the influence of data samples and the experimental environment on detection tools as well.

For the detection of HG002, we used standard ground truth obtained from Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) to analyze the detection results. GIAB is a consortium hosted by NIST dedicated to the authoritative characterization of benchmark human genomes. Figure 15 shows that the Precision, Recall and F1_score calculated based on the standard ground truth in GIAB. From this figure, we can clearly see that Control-FREEC and IFTV exhibit the highest precision, while Delly demonstrates superior Recall and F1_score compared to other detection tools. In the simulated data, due to the 36 experimental parameters, the detection performance of Control-FREEC and IFTV did not meet expectations. HG002 represents a specific combination of experimental configurations, and it is possible that Control-FREEC and IFTV are particularly well-suited for detecting this type of data, which could explain their high precision and recall. This observation highlights that each detection tool has its own strengths and weaknesses, emphasizing the importance of selecting the appropriate tool for the detection task.

Further, under the same configuration, we calculated the time complexity and space complexity of each tool in real data. All our experiments were conducted on an Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS system. The computer used for the experiments was equipped with a 13th generation Intel® Core™ i7-13700F processor (24 cores), 16 GB of RAM, and 512.1 GB of storage. Additionally, we recorded the time and physical memory consumption of 12 tools while detecting real data. Figure 16 shows the time complexity of the tools when detecting real data. In the detection process, Pindel exhibits the highest time complexity, while Control-FREEC demonstrates the lowest time complexity. We evaluated the space complexity by measuring the physical memory consumption of these tools when they detect CNVs. Figure 17 shows the physical memory consumed when detecting real data. TARDIS uses the most physical memory, whereas Control-FREEC consumes the least physical memory.

Discussion

In this paper, we evaluated 12 popular and representative CNV detection tools, comparing their performance in detecting six CNV types under three variant lengths, four sequencing depths, and three tumor purities. We also studied the impact of different configurations on detection effectiveness and provided recommendations for selecting detection tools based on various experimental setups. This information will assist researchers in making more informed recommendations for selecting detection tools. During the detection process, highly overlapping results often appear in the same detection report VCF generated by individual tools, with some findings differing by only a few tens of bases. To ensure the fairness of the results, we filtered out these closely coincident findings. This comparison aims to assist researchers in selecting the most suitable tools for exploring CNV.

In the study, we used simulated data and real data to evaluate and compare 12 detection tools. For simulated data, we compared the Precision, Recall and F1_score, while for real data, we used ODS and standard ground truth to analyze the detection results. We not only analyzed the impact of different configurations on detection tools but also made recommendations for the selection of detection tools under various configurations. For example, Breakdancer has a good detection performance when the variant length is 1 K–10 K, while GROM-RD is suitable for 1 K–100 K variant length detection. Pindel detects the most variant types, and Matchclips2 has a small boundary bias but is suitable for higher sequencing depth.

In our study, we provided more suitable recommendations for researchers in selecting detection tools by conducting an extensive comparison of the detection performance of six types of CNV under 36 different parameter settings. However, there is still room for improvement. (1) The experimental configuration can be more comprehensive. The sequencing depth can be set to 50x and 100x, and the CNV variant lengths can be set to 1 M–3 M and 3 M–5 M. (2) Variant types are more complex. Although we have set up six types of CNV, there are more intricate CNV in clinical medicine. Therefore, we need to simulate more kinds of CNV to enhance the simulation accuracy of the generated data and make it more representative of real samples.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the “The International Genome Sample Resource”: The data of NA19238: https://www.internationalgenome.org/data-portal/sample/NA19238, The data of NA19239: https://www.internationalgenome.org/data-portal/sample/NA19239, The data of NA19240: https://www.internationalgenome.org/data-portal/sample/NA19240, The data of HG002: https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ReferenceSamples/giab/data/AshkenazimTrio/HG002_NA24385_son/NIST_Stanford_Illumina_6kb_matepair/bams/GRCh38/.

References

Eichler, E. E. Human genome structural variation and disease. Pathology 44, S30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-3025(16)32674-5 (2012).

Garsed, D. W. et al. The architecture and evolution of cancer neochromosomes. Cancer Cell 26, 653–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.010 (2014).

Balachandran, P. & Beck, C. R. Structural variant identification and characterization. Chromosome Res. 28, 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10577-019-09623-z (2020).

Baker, M. Structural variation: The genome’s hidden architecture. Nat. Methods 9, 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1858 (2012).

Stankiewicz, P. & Lupski, J. R. Structural variation in the human genome and its role in disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 61, 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-100708-204735 (2010).

Gordeeva, V., Sharova, E. & Arapidi, G. Progress in methods for copy number variation profiling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23042143 (2022).

Pös, O. et al. Copy number variation: methods and clinical applications. Appl. Sci. 11, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020819 (2021).

Pabinger, S. et al. A survey of tools for variant analysis of next-generation genome sequencing data. Brief. Bioinform. 15, 256–278. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbs086 (2014).

Hu, T. S., Chitnis, N., Monos, D. & Dinh, A. Next-generation sequencing technologies: An overview. Hum. Immunol. 82, 801–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2021.02.012 (2021).

Lin, K., Smit, S., Bonnema, G., Sanchez-Perez, G. & de Ridder, D. Making the difference: integrating structural variation detection tools. Brief Bioinform 16, 852–864. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbu047 (2015).

Szatkiewicz, J. P., Wang, W., Sullivan, P. F., Wang, W. & Sun, W. Improving detection of copy-number variation by simultaneous bias correction and read-depth segmentation. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(3), 1519–1532 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1363.

Korbel, J. O. et al. Paired-end mapping reveals extensive structural variation in the human genome. Science 318, 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1149504 (2007).

Zhang, Z. D. D. et al. Identification of genomic indels and structural variations using split reads. BMC Genomics 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-375 (2011).

Sohn, J. I. & Nam, J. W. The present and future of de novo whole-genome assembly. Brief Bioinform. 19, 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbw096 (2018).

Dida, F. & Yi, G. Empirical evaluation of methods for de novo genome assembly. PeerJ. Comput. Sci. 7, e636. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.636 (2021).

Zhao, M., Wang, Q. G., Wang, Q., Jia, P. L. & Zhao, Z. M. Computational tools for copy number variation (CNV) detection using next-generation sequencing data: features and perspectives. BMC Bioinform. 14, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-s11-s1 (2013).

Talevich, E., Shain, A. H., Botton, T. & Bastian, B. C. CNVkit: genome-wide copy number detection and visualization from targeted DNA sequencing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12, 18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004873 (2016).

Abyzov, A., Urban, A. E., Snyder, M. & Gerstein, M. CNVnator: An approach to discover, genotype, and characterize typical and atypical CNVs from family and population genome sequencing. Genome Res. 21, 974–984. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.114876.110 (2011).

Miller, C. A., Hampton, O., Coarfa, C. & Milosavljevic, A. ReadDepth: A parallel R package for detecting copy number alterations from short sequencing reads. PLoS ONE 6, 7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016327 (2011).

Rausch, T. et al. DELLY: structural variant discovery by integrated paired-end and split-read analysis. Bioinformatics 28, I333–I339. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts378 (2012).

Layer, R. M., Chiang, C., Quinlan, A. R. & Hall, I. M. LUMPY: a probabilistic framework for structural variant discovery. Genome Biol. 15, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2014-15-6-r84 (2014).

Soylev, A., Le, T. M., Amini, H., Alkan, C. & Hormozdiari, F. Discovery of tandem and interspersed segmental duplications using high-throughput sequencing. Bioinformatics 35, 3923–3930. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz237 (2019).

Kosugi, S. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of structural variation detection algorithms for whole genome sequencing. Genome Biol. 20, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1720-5 (2019).

Cameron, D. L., Di Stefano, L. & Papenfuss, A. T. Comprehensive evaluation and characterisation of short read general-purpose structural variant calling software. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11146-4 (2019).

Zhao, L. L., Liu, H., Yuan, X. G., Gao, K. & Duan, J. B. Comparative study of whole exome sequencing-based copy number variation detection tools. BMC Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-020-3421-1 (2020).

Zare, F., Dow, M., Monteleone, N., Hosny, A. & Nabavi, S. An evaluation of copy number variation detection tools for cancer using whole exome sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. 18, 286. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-017-1705-x (2017).

Yao, R. et al. Evaluation of three read-depth based CNV detection tools using whole-exome sequencing data. Mol. Cytogenetics https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-017-0333-5 (2017).

Zhang, L., Bai, W. Y., Yuan, N. & Du, Z. L. Comprehensively benchmarking applications for detecting copy number variation. PLoS Comput. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007069 (2019).

Moreno-Cabrera, J. M. et al. Evaluation of CNV detection tools for NGS panel data in genetic diagnostics. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 28, 1645–1655. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-020-0675-z (2020).

Zhang, Y., Liu, W. & Duan, J. On the core segmentation algorithms of copy number variation detection tools. Brief. Bioinform https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbae022 (2024).

Li, Y. & Xie, X. H. Deconvolving tumor purity and ploidy by integrating copy number alterations and loss of heterozygosity (vol 30, pg 2121, 2014). Bioinformatics 31, 618–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu683 (2015).

Koo, B. & Rhee, J. K. Prediction of tumor purity from gene expression data using machine learning. Brief. Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab163 (2021).

Hermetz, K. E. et al. Large inverted duplications in the human genome form via a fold-back mechanism. PLoS Genet. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004139 (2014).

Alkan, C., Coe, B. P. & Eichler, E. E. Genome structural variation discovery and genotyping. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 363–376. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2958 (2011).

Chen, K. et al. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat. Methods 6, 677. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1363 (2009).

Boeva, V. et al. Control-FREEC: a tool for assessing copy number and allelic content using next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 423–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr670 (2012).

Smith, S. D., Kawash, J. K. & Grigoriev, A. GROM-RD: resolving genomic biases to improve read depth detection of copy number variants. PeerJ 3, 18. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.836 (2015).

Yuan, X. G. et al. CNV_IFTV: An isolation forest and total variation-based detection of CNVs from short-read sequencing data. IEEE-ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 18, 539–549. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcbb.2019.2920889 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Manta: rapid detection of structural variants and indels for germline and cancer sequencing applications. Bioinformatics 32, 1220–1222. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv710 (2015).

Wu, Y., Tian, L., Pirastu, M., Stambolian, D. & Li, H. MATCHCLIP: locate precise breakpoints for copy number variation using CIGAR string by matching soft clipped reads. Front. Genet. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2013.00157 (2013).

Ye, K., Schulz, M. H., Long, Q., Apweiler, R. & Ning, Z. M. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 25, 2865–2871. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394 (2009).

Eisfeldt, J., Vezzi, F., Olason, P., Nilsson, D. & Lindstrand, A. TIDDIT, an efficient and comprehensive structural variant caller for massive parallel sequencing data. Research https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11168.1 (2017).

Dharanipragada, P., Vogeti, S. & Parekh, N. iCopyDAV: Integrated platform for copy number variations-detection, annotation and visualization. PLoS ONE 13, e0195334. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195334 (2018).

Yoon, S., Xuan, Z., Makarov, V., Ye, K., & Sebat, J. Sensitive and accurate detection of copy number variants using read depth of coverage. Genome Res. 19(9), 1586–1592. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.092981.109 (2009).

Raman, L., Dheedene, A., De Smet, M., Van Dorpe, J. & Menten, B. WisecondorX: improved copy number detection for routine shallow whole-genome sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 1605–1614. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1263 (2019).

Jiang, T. et al. Long-read-based human genomic structural variation detection with cuteSV. Genome Biol. 21, 189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-020-02107-y (2020).

Heller, D. & Vingron, M. SVIM: structural variant identification using mapped long reads. Bioinformatics 35, 2907–2915. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz041 (2019).

Sedlazeck, F. J. et al. Accurate detection of complex structural variations using single-molecule sequencing. Nat. Methods 15, 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0001-7 (2018).

Wang, Y. H., Han, Y. Y., Wang, Y. T., Pan, Q. K. & Wang, L. Sustainable scheduling of distributed flow shop group: A collaborative multi-objective evolutionary algorithm driven by indicators. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 28, 1794–1808. https://doi.org/10.1109/tevc.2023.3339558 (2024).

Wang, Y. H. et al. Reinforcement learning-assisted memetic algorithm for sustainability-oriented multiobjective distributed flow shop group scheduling. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsmc.2024.3518625 (2025).

Jia, R. C., Zhang, Z. L., Jia, Y. L., Papadopoulou, M. & Roche, C. Improved GPT2 event extraction method based on mixed attention collaborative layer vector. IEEE Access 12, 160074–160082. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2024.3487836 (2024).

Yuan, X. G., Li, Z., Zhao, H. Y., Bai, J. & Zhang, J. Y. Accurate inference of tumor purity and absolute copy numbers from high-throughput sequencing data. Front. Genet. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.00458 (2020).

Liu, B. et al. MEpurity: estimating tumor purity using DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics 35, 5298–5300. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz555 (2019).

Yuan, X. et al. CONDEL: Detecting copy number variation and genotyping deletion zygosity from single tumor samples using sequence data. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf. 17, 1141–1153. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcbb.2018.2883333 (2020).

Pattnaik, S., Gupta, S., Rao, A. A. & Panda, B. SInC: an accurate and fast error-model based simulator for SNPs, Indels and CNVs coupled with a read generator for short-read sequence data. BMC Bioinform. 15, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-40 (2014).

Escalona, M., Rocha, S. & Posada, D. A comparison of tools for the simulation of genomic next-generation sequencing data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.57 (2016).

Mirzaei, G. & Petreaca, R. C. Distribution of copy number variations and rearrangement endpoints in human cancers with a review of literature. Mutat. Res./Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagenesis 824, 111773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2021.111773 (2022).

Yuan, X., Li, J., Bai, J. & Xi, J. A local outlier factor-based detection of copy number variations from NGS data. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 18, 1811–1820. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcbb.2019.2961886 (2021).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 (2010).

Li, H. J. a. G. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. (2013).

Cock, P., Bonfield, J., Chevreux, B. & Li, H. (bioRxiv, 2015).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 (2009).

Jia, D. C., Dong, J. X., Jiang, H., Zhao, Z. Y. & Jiang, X. L. TD-COF: A new method for detecting tandem duplications in next generation sequencing data. Softwarex https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2024.101881 (2024).

Zhang, Z. L., Jia, Y. L., Zhang, X. L., Papadopoulou, M. & Roche, C. Weighted co-occurrence bio-term graph for unsupervised word sense disambiguation in the biomedical domain. IEEE Access 11, 45761–45773. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2023.3272056 (2023).

Huang, T. H., Li, J. Q., Jia, B. X. & Sang, H. Y. CNV-MEANN: A neural network and mind evolutionary algorithm-based detection of copy number variations from next-generation sequencing data. Front. Genet. 12, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.700874 (2021).

Brosens, R. P. et al. Candidate driver genes in focal chromosomal aberrations of stage II colon cancer. J. Pathol. 221, 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.2724 (2010).

Pös, O. et al. DNA copy number variation: Main characteristics, evolutionary significance, and pathological aspects. Biomed. J. 44, 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2021.02.003 (2021).

Qi, M.-Y., Li, J.-Q., Han, Y.-Y. & Dong, J.-X. Optimal chiller loading for energy conservation using an improved fruit fly optimization algorithm. Energies 13, 3760. https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153760 (2020).

Wang, X. W. et al. PEcnv: accurate and efficient detection of copy number variations of various lengths. Brief. Bioinform. 23, 9. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbac375 (2022).

Pfeifer, S. P. From next-generation resequencing reads to a high-quality variant data set. Heredity 118, 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2016.102 (2017).

Sims, D., Sudbery, I., Ilott, N. E., Heger, A. & Ponting, C. P. Sequencing depth and coverage: Key considerations in genomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3642 (2014).

Ajay, S. S., Parker, S. C. J., Abaan, H. O., Fajardo, K. V. F. & Margulies, E. H. Accurate and comprehensive sequencing of personal genomes. Genome Res. 21, 1498–1505. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.123638.111 (2011).

Mirzaei, G. & Petreaca, R. C. Distribution of copy number variations and rearrangement endpoints in human cancers with a review of literature. Mutat. Res.-Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 824, 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2021.111773 (2022).

Lei, Y. et al. Overview of structural variation calling: Simulation, identification, and visualization. Comput. Biol. Med. 145, 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105534 (2022).

Conway, J. R., Lex, A. & Gehlenborg, N. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics 33, 2938–2940. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx364 (2017).

Lex, A., Gehlenborg, N., Strobelt, H., Vuillemot, R. & Pfister, H. UpSet: Visualization of intersecting sets. IEEE Trans. Visual Comput. Graphics 20, 1983–1992. https://doi.org/10.1109/tvcg.2014.2346248 (2014).

Funding

This paper was supported by Special Task Subject of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China-Cloud Native Database Architecture Innovation and High Performance Core Technology Project under Grant ZTZB-23-990-024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruchao Du and Jinxin Dong wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, R., Dong, J., Jiang, H. et al. Comparative study of tools for copy number variation detection using next-generation sequencing data. Sci Rep 15, 22145 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06527-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06527-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

An improved GPT2-based joint event extraction method with position expansion and knowledge augmentation

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Research on the similarity calculation of short text in the terminology domain based on siamese BERT model

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

SSLCNV: A Semi-supervised Learning Framework for Accurate Copy Number Variation Detection

Interdisciplinary Sciences: Computational Life Sciences (2025)