Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is a treatment modality for several hematological and immune-driven diseases. A conditioning regimen precedes transplantation. These comprise myeloablative (MA) conditioning consisting of chemotherapeutics often in combination with high-dose total body irradiation (TBI), while non-myeloablative (NMA) conditioning regimens use reduced dosage of chemotherapy and TBI allowing allo-HCT to patients who would otherwise not be eligible for treatment. While cellular immune reconstitution in allo-HCT patients has been well studied, differences between MA and NMA conditioned patients including the functional status of the immune system post-transplantation remains unclear. Seventy-seven patients undergoing allo-HCT were included in the main study, only including patients receiving peripheral blood stem cell grafts, no ATG treatment and no other GVHD prophylaxis than tacrolimus + methotrexate or cyclosporine + MMF + sirolimus (median age 59; IQR: 48–65). The cohort consisted of 34 patients receiving MA conditioning and 43 NMA conditioned patients. As a proxy for post-transplantation immune function, we analyzed stimulated cytokine release patterns in whole-blood samples from MA and NMA patients before and after transplantation alongside major immune cell phenotypes and T cell chimerism on day 28 after transplantation. Notably, among patients receiving grafts from peripheral blood apheresis, MA patients exhibited higher T cell counts, and elevated CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release compared to NMA patients. Assessment of associations between cytokine release and immune cell concentration associations indicated that variation in T cell or other immune cell concentrations between the cohorts could not account for differences in CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release. Meanwhile, LPS- and R848-stimulated cytokine release was associated with innate immune cell subtypes. A secondary study amongst MA conditioned patients further revealed that those who received fludarabine and treosulfan (n = 35) had higher T cell concentration and stimulated immune function compared to patients receiving more intense MA regimens (n = 15). These findings highlight the complex impact conditioning has on immune function after allo-HCT. Further analyses of T cell compartments and myeloid/lymphoid innate cells are needed to further understand the functional differences observed between conditioning groups and the potential impact on clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is a treatment modality for hematological diseases such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)1. A major treatment-related factor in allo-HCT is the conditioning regimen that precedes the transplantation of the hematopoietic cell graft2. Myeloablative (MA) conditioning regimens consist of treatment with chemotherapy often in combination with high-dose total body irradiation (TBI), to which anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) can be added to further target the T cell compartment as graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) prophylaxis3. The intensity of pre-transplantation conditioning regimens has been modulated to reduce toxicity. This has led to the introduction of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) and reduced-toxicity conditioning (RTC), which in turn has created the need for new assessment tools such as treatment conditioning intensity (TCI) grading. Stratification into MA and non-myeloablative (NMA) conditioning regimens is still a possibility due to the myeloablative properties of the alkylating agents used in e.g. RTC2,4,5. MA conditioning regimens include these RTC regimens that lead to less organ toxicity and better clinical outcomes and are still considered to be myeloablative6,7. RIC or NMA conditioning regimens are offered to patients with a higher risk of treatment induced toxicity and treatment related mortality (TRM), including elderly patients and patients with comorbidities or organ dysfunction who were previously deemed ineligible for allo-HCT8,9.

Timely immune reconstitution of donor-derived immune cells after allo-HCT is important for a favorable outcome for patients, i.e. low incidence of infections, relapse and TRM10,11. Many complications after allo-HCT are related to the dysregulated state of the immune system. Infections can reflect underlying immunodeficiencies, while hyperinflammatory states such as GVHD can also occur. While the cellular reconstitution after allo-HCT has been studied12,13and stimulated cytokine release in relation to allo-HCT also has been explored14the impact on both cellular and functional immune reconstitution by different conditioning regimens remains unclear.

Pre-transplantation conditioning exerts multiple effect on the immune system and other affected tissues such as the intestinal lining. These effects vary depending on the type of applied conditioning regimen. MA conditioning creates a highly proinflammatory environment through radiation ± chemotherapy via release of damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in affected tissues. Conditioning also leaves the patient exposed to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by damaging immune barrier integrity which further increases a pro-inflammatory environment with subsequent increased antigen presentation and activation of antigen-presenting cells, as well as bridging activation of adaptive lymphocytes such as T cells15,16. While the release of e.g. DAMPs is also present in reduced intensity/NMA conditioning, these conditioning regimens exert lower tissue toxicity. NMA conditioning also entails a higher prevalence of mixed donor/recipient chimerism early after allo-HCT17. Consequently, successful disease control in the NMA conditioning setting relies more heavily on the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect, as the conditioning alone is insufficient to eradicate residual malignant cells2. In both MA and NMA conditioning regimens, immune status is impeded by multiple treatment-related factors such as GVHD prophylaxis. Investigation of key differences in immune composition and function between conditioning regimens post-HCT could improve understanding of immune mechanisms in allo-HCT complications and may help elucidate potential targets for better tailored treatment strategies.

To improve our understanding of the immunological status of patients after allo-HCT, this study aimed at assessing functional immune profiles in patients receiving MA vs. NMA conditioning regimens. Findings could provide a basis for identifying new potential targets for preventing immune-related complications. For this purpose, stimulated cytokine release, immune cell reconstitution, and donor/recipient T cell chimerism were assessed and compared between MA and NMA patients, and within subgroups of the MA subcohort. The main study was a comparative analysis of patients receiving MA vs. NMA conditioning with exclusion of patients receiving grafts other than peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC), ATG-treatment, or GVHD-prophylaxis other than cyclosporine (CsA)/mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)/sirolimus or tacrolimus(Tac)/methotrexate (MTX) (Fig. 1). The secondary study investigated differences between patients receiving combined fludarabine + treosulfan (FluTreo) vs. patients receiving other MA-classified conditioning regimens, but without the previously mentioned exclusion criteria regarding graft type or ATG.

Methods

Patient inclusion, sample, and data collection

This study included 100 adult patients (> 18 years of age) who were scheduled for allo-HCT at The Department of Hematology, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark after giving written and oral informed consent. Apart from adult age and HCT treatment, no specific criteria was applied in inclusion in the study period and patients were included consecutively. Due to time-dependent constraints on the applied advanced immunological analyses, concurrent study participation, clinical factors, and patient self-exclusion, only a subset of HCT patients at the department were included in the study. Blood samples for immunophenotyping were obtained just prior to conditioning, which was approximately 4 days before transplantation for NMA patients and 7 days for MA conditioning with an overall median of 6 days prior to transplantation for all patients. A second sampling was analyzed on day 28 post-HCT (median: 28.0; IQR: 27.0–30.0, min. 25; max 39). Post-transplant outcomes registered during the follow-up time were occurrence of relapse, acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, or death due to relapse or non-relapse mortality (NRM). Clinical data was retrieved from the clinical allo-HCT database at The Department of Hematology, Rigshospitalet. Data on chimerism was collected from electronic health records. Where available, donor/recipient chimerism data was acquired from the Department of Clinical Immunology. Short tandem repeats were applied for chimerism analysis until March 2022. Afterwards, analyses were performed by next generation sequencing18. Chimerism was reported as percentage of donor cells for CD4 and CD8 T cells. The study is part of the ImmuneMo study19and was approved by the Data Protection Agency (RH-2015-04, I-Suite nr: 03605) and Danish Ethical Committee (H-17024315) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conditioning regimens

MA conditioning regimens included: cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg) and 12 Gy TBI (CyTBI-12 Gy), and etoposide (1.800 mg/m2) and 12 Gy TBI (EtoTBI-12 Gy). Fludarabine and busulfan (FluBu). Fludarabine (120 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (120 mg/m2) (FluCy) and fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and 2 Gy TBI (FluCyTBI-2Gy). Fludarabine (150 mg/m2) and treosulfan (42 g/m2) (FluTreo). Fludarabine, treosulfan, and 2 Gy TBI (FluTreoTBI-2Gy). Conditioning with FluCy or FluTreo are known to be RTC regimens but are still classified as myeloablative. The NMA regimen included fludarabine (90 mg/m2) and 2–3 Gy TBI (FluTBI-2Gy), as well as fludarabine (90 mg/m2) and 3 Gy TBI (FluTBI-3 Gy). ATG was added to MA conditioning regimens for 12 patients.

GvHD prophylaxis

For GVHD prophylaxis, 43 patients received combined cyclosporin (CsA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and sirolimus, which was solely used for patients that had undergone NMA conditioning. Combined tacrolimus (Tac) and methotrexate (MTX) was administered to 36 MA patients and CsA and MTX to 18 patients. Combined Tac and MMF was given to a single MA and NMA patient, while only one MA patient received combined CsA and MMF.

TruCulture immune stimulation assay

As previously described14heparinized whole blood samples were incubated with or without stimuli for a 22-hour period in commercially available functional immune stimulation TruCulture tubes (Rules-Based Medicine, USA). Specifically, applied stimuli included: (1) the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) agonist bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS), (2) the TLR7/8 agonist resiquimod (R848) representing single strand ribonucleic acid (ssRNA) viruses, (3) the TLR3 agonist Poly I:C representing double stranded RNA (dsRNA) viruses, (4) the T cell receptor/co-receptor stimulator anti-CD3/CD28. An unstimulated tube was incubated in parallel with the stimulated tubes. Following stimulation, a Luminex (Luminex, Belgium) analysis of the levels of nine select innate and adaptive immune process-related cytokines of both pro- and anti-inflammatory nature (IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17A, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF) were analyzed in TruCulture supernatants. Reference values from 31 healthy individuals were displayed in Supplementary information file 2 tables S1.

DuraClone flow cytometry analysis

Flow cytometry was carried out on EDTA treated whole-blood within 24 h of sampling as previously described20,21. Briefly, pre-dried antibodies (DuraClone, Beckman Coulter, USA) were applied in a cell marker panel routinely used for clinical immunodeficiency diagnostics in adult and pediatric patients. Absolute concentrations of major immune cell lines were reported including T cells and CD4/CD8 subsets, B cells, NK cells, monocytes, and neutrophils. Antibodies used for flow cytometry cell phenotyping were listed in Supplementary information file 2 tables S2 and cell concentration ranges for adults were listed in Supplementary information file 2 tables S3.

Statistical analyses

Mann-Whitney U-tests (MWU) were used to assess differences in stimulated cytokine release and immune cell subset concentrations between MA/NMA patients. Non-parametric analyses were chosen because data were not normally distributed. Bonferroni adjusted Pearson correlation matrices of cytokine release and immune cell subtype concentration were conducted for MA/NMA patients for day 28, using hierarchical clustering under default parameters. Adjustments were made for 9 tests/cytokine analyses. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis were applied for cytokine release variables at day 28 after allo-HCT, with log-transformed cytokine concentration values as the response variable and log-transformed immune cell subset concentration values as covariates. Only positive or negative coefficient estimates over/under 0.3 and − 0.3 and with p-values under the Bonferroni adjusted p-value threshold (p = 0.0055, also adjusting for 9 tests/analyzed cytokines) were reported as significant. For the multivariate linear regression analyses we used CD4, CD8, NK cells, monocytes, and neutrophil concentrations as covariates to analyze the relationship between these specific immune cell subset concentrations and the cytokine release after LPS-, R848, and CD3/C28-stimulation. To investigate whether model adjustments for patient characteristics were needed, univariate linear regression analyses for the following patient characteristics for both the main study cohort of 77 individuals and for both MA/NMA cohorts were carried out: age (continuous), age over 55 (0/1), donor/recipient match grade (unrelated matched/other), donor age (continuous), and donor age over 30 (0/1), and in addition conditioning was also analyzed for in the main study cohort. These analyses found that conditioning and donor age over 30 showed multiple significant associations in the main study cohort, while only donor age over 30 was added in the MA/NMA subcohort analyses. The multivariate analyses were subsequently adjusted for these variables.

Associations between T cell chimerism and stimulated cytokine output from patients with available CD4 and/or CD8 chimerism data at day 28 post-HCT, were assessed using linear models with log-transformed CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release as response variable and log-transformed CD4 or CD8 chimerism as covariates, adjusting for cell concentrations of CD4 or CD8 T cells respectively. All statistical analyses and visualizations were conducted using R v. 4.4.1.

Study design overview. (A) Study subgroups. (B) Applied immunophenotyping assays. The primary study analyzed differences in myeloablative (MA) versus NMA conditioned patients (total n = 77) where only patients receiving peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) grafts and either combined cyclosporin (CsA), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and sirolimus or combined tacrolimus (Tac) and methotrexate (MTX) as GVHD-prophylaxis, were included, while patients receiving anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) were excluded. The secondary study featured analyses of patients receiving MA conditioning with FluTreo (fludarabine + treosulfan) versus other MA conditioning regimens (cyclophosphamide + total body irradiation, etopophos + total body irradiation or fludarabine + busulfan. Samples were taken before conditioning and around day 28 post-HCT. Created in BioRender. Ostrowski, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/28qxbcs.

Results

Patient inclusion and characteristics

The main study included 77 patients (> 18 years of age) that underwent allo-HCT between March 2021 and July 2023 (Table 1). Only patients receiving peripheral blood apheresis grafts were included and patients receiving ATG or GVHD-prophylaxis other than CsA/MMF/sirolimus or tacrolimus/MTX were excluded. The patients had a median age of 59 years, and 39% were female. Most patients were transplanted for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS, n = 40) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n = 24). Thirty-four patients underwent MA conditioning, and 43 received NMA conditioning. Median donor age was 26 years, 35 donors were female, and 14% of transplantations were female-to-male.

Tissue type matching between donors and recipients included 62 unrelated 10/10 HLA matched, 7 identically matched siblings and 8 unrelated single-antigen or allele mismatched.

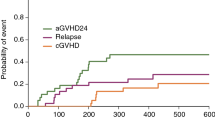

During the 438 days median follow-up time (IQR: 281–728; min. 115; max 932), 10 patients experienced relapse and 13 had grade II aGVHD. Twelve died within the follow-up time with 4 due to relapse and 8 due to non-relapse mortality (NRM) (Supplementary Material Table T1). The entire cohort (n = 100) from which the main and secondary study cohorts are derived is presented in Supplementary Material Table T2, including clinical outcomes (Supplementary Material Table T3).

Stimulated cytokine release on day 28 post-HCT

When investigating variations in immune function between conditioning regimens post-HCT in response to both innate (TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7/8) and adaptive (T-cell) stimuli, the patients in the main study cohort had a more homogeneous T cell profile. While no differences were observed in the unstimulated cytokine response (Fig. 2A, Supplementary information file 2 tables S4), CD3/CD28-stimulated IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-17 A release was reduced in NMA patients compared to MA patients (Fig. 2B). LPS-stimulated IL-10, IL-6, and IL-8 release and R848-stimulated IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-6 release was reduced in NMA compared to MA patients (Fig. 2C-D). The Poly I:C-stimulated cytokine release did not differ between MA and NMA patients (Fig. 2E).

Stimulated cytokine release in myeloablative (MA, n = 34) and non-myeloablative (NMA, n = 43) conditioned patients on day 28 post-HCT. Concentrations were log transformed. (A) Unstimulated (B) CD3/CD28 (T cell stimulation) (C) LPS (TLR4 stimulation) (D) R848 (TLR7/8 stimulation) (E) Poly I:C (TLR3 stimulation). Significance levels: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Blue shaded area represents normal concentration reference ranges for stimulated cytokine release.

Stimulated cytokine release before conditioning vs. post-HCT

CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release at day 28 post-HCT was reduced compared to samples taken before conditioning for IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-17A, and TNF (Supplementary Material Figure S1 & Supplementary information file 2 tables S4). Unstimulated, LPS-, and R848-stimulated cytokine release was increased for multiple cytokines 28 days post-HCT compared to pre-conditioning, especially observed after R848-stimulation, but only IL-8 was increased after Poly I:C stimulation.

Immune cell composition and concentrations post-HCT

In the main study cohort, all immune cells subsets except neutrophils were lower at day 28 post-HCT in NMA compared to MA patients (Fig. 3 & Supplementary information file 2 tables S5 & S6).

Looking at the MA and NMA cohorts combined, comparison of immune cell concentrations before and after treatment revealed a significant decline of B cells and T cells including CD4 and CD8 subsets post-HCT (Supplementary Material Figure S2 & Supplementary information file 2 tables S6). In contrast, a significant increase in the concentration of monocytes and NK cells was observed post-HCT compared to before conditioning while neutrophil concentrations did not differ between the two investigated timepoints (Supplementary information file 2 tables S6). No differences were observed between MA and NMA patients before conditioning (Supplementary Material Figure S3 & Supplementary information file 2 tables S6).

Distribution of immune cell subset concentrations day 28 after allo-HCT between myeloablative (MA)(n = 34) and non-myeloablative (NMA) (n = 43) conditioned patients. (A) Stacked barplots of cell percentages between MA and NMA conditioning groups. (B) Boxplots of log-transformed cell concentrations. Significance levels: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Grey rectangles represent normal reference ranges.

Correlation between stimulated cytokine release and immune cell subset concentrations

To investigate whether the observed differences in CD3/CD28-, LPS- and R848-stimulated cytokine release among all patients (n = 77), as well as within subset cohorts of patients undergoing MA (n = 34) or NMA conditioning (n = 43), could be explained by variation in immune cell subset concentrations, correlation analysis between each cytokine variable and immune cell subtype concentration was applied (Fig. 4).

For all patients, CD3/CD28-stimulated IFN-γ release was positively correlated with overall T cell concentrations, LPS-stimulated IL-10 was positively correlated with monocytes, overall T cells and CD8 T cells, and R848-stimulated IL-6 release correlated positively with monocytes. The R848-stimulated IL-6/monocyte correlation persisted in MA conditioned patients. When comparing results, overall correlations between variables differed for MA and NMA patients. Inter/intra correlation of cytokines and immune cells also differed between conditioning regimens (Fig. 4A-C). Correlations between CD3/CD28-, LPS- and R848-stimulated cytokine release and immune cell subsets revealed few significant findings.

Heatmaps of correlation analyses. Day 28 post-HCT stimulated cytokine release and immune cell types from all patients (n = 77), as well as subset cohorts of patients undergoing myeloablative (MA) (n = 34) or non-myeloablative conditioning (NMA) (n = 43). Only significant results after Bonferroni adjustment for multiple tests are shown with asterisks. Red boxes indicate stimulated cytokine release and immune cell correlation analysis results. Inter/intra correlation of cytokines and immune cells are located outside red boxes. Colored grading of intensity presented in bottom bar of each plot shows R-values where blue coloring shows negative correlation and red shows positive correlation between variables. (A) CD3/CD28 stimulation. (B) LPS stimulation. (C) R848 stimulation. Significance levels: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

Modelled association between stimulated cytokine release and immune cell subset concentrations

To better assess the complex nature of stimulated cytokine release and given that whole blood samples contain multiple immune cell subtypes that interact, univariate and multivariate linear regression models were fitted with cytokine release concentrations as the response variable and immune cell concentrations as covariates for all patients in the main study cohort (n = 77) and for the MA and NMA patient subcohorts (Fig. 5; model data reported in Supplementary information file 2 tables S7. Estimate plots shown in Supplementary Material Figure S4-S9).

In the univariate analysis, positive associations between immune cell concentrations of CD4, CD8, NK-cells, monocytes and CD3/CD28-stimulated IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-17A were observed in the main study cohort, and CD4 and CD8 T cells were associated with CD3/CD28-stimulated IFN-γ and IL-10 in the NMA patient subcohort. No associations between immune cells and CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release persisted in subsequent multivariate analyses.

In the main study cohort, monocytes were positively associated with R848-stimulated IL-12, IL-17A, IL-8 and TNF release, while neutrophils were negatively associated with release of IFN-α, IL-12, IL-17A, and TNF in analyses for all patients in the main study. In the NMA subcohort, monocyte association with R848-stimulated IL-12 (coefficient estimate: 1.03; p-value = 0.001) and IL-17 A (coefficient estimate: 0.89; p-value = 0.002) persisted. In the MA subcohort, R848-stimulted IFN-γ (coefficient estimate: 1.67; p-value = 0.0059) and IFNα release (coefficient estimate: 1.2; p-value = 0.0057) exhibited notably high positive model coefficient estimates (Supplementary information file 2 tables S7) taking into regard that the p-values of these model results were just above the Bonferroni adjusted p-value threshold (p = 0.0055).

Volcano plots showing -log10 p-values versus linear regression model coefficient estimates from univariate (A & C) and multivariate (B & D) modelling of associations between post-HCT stimulated cytokine release as dependent variables and immune cell subtype concentration variables as covariates. Results from both the main study cohort (n = 77, green) and patients undergoing myeloablative (MA, n = 34, red) and non-myeloablative conditioning (NMA, n = 43, blue) are presented. Multiple immune cell subtypes (CD4, CD8, NK-cells, monocytes and neutrophils) were adjusted for in the multivariate model, that also included adjustment for donor age over 30, and conditioning in linear models with all patients (n = 77). Only significant results (Bonferroni adjusted p-values correcting for 9 tests per each stimulus) and coefficient estimates >/< ±0.3) are reported with labels. Only patients transplanted with a peripheral blood stem cell graft were included and patients receiving ATG or TAC + MMF/CsA + MMF GVHD prophylaxis were excluded. Dashed red line is p = 0.05, while solid red line represents Bonferroni corrected p-value threshold (p = 0.055). (A) Univariate linear regression model results of CD3/CD28, LPS, and R848 for all patients. (B) Multivariate analyses of CD3/CD28, LPS, and R848 linear regression model results for all patients. (C) Univariate analyses of CD3/CD28, LPS, and R848 linear models results for MA and NMA patients. (D) Multivariate analyses of CD3/CD28, LPS, and R848 linear models results for MA and NMA patients.

Associations between stimulated cytokine output and chimerism

Data on T cell subset chimerism (CD4 and/or CD8) measured within +/- 5 days of day 28 sampling was available for 65 patients from the main study (Fig. 6). A single positive association was observed between CD4 donor chimerism and CD3/CD28-stimulated IL-10 in NMA patients (n = 35) (Supplementary information file 2 tables S8), but no association was found for T cell chimerism and CD3/CD28 stimulated cytokine release in MA patients (n = 30).

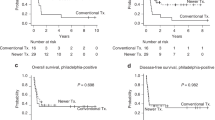

Immune cell differences within different myeloablative conditioning regimens - FluTreo vs. other myeloablative

In the secondary study, 35 patients undergoing MA conditioning with combined fludarabine + treosulfan (n = 35) were compared to patients receiving more intense MA conditioning regimens (n = 15) including cyclophosphamide + TBI, etoposide + TBI, or fludarabine + busulfan (Fig. 7). On day 28 post-HCT, CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release was significantly higher in fludarabine + treosulfan conditioned patients compared to other MA-patients, observed for all measured cytokines except IL-6 (Fig. 7A, Supplementary information file 2 tables S9). Overall T cell (CD3), CD4 T cell and B-cell concentrations were elevated in patients receiving fludarabine + treosulfan post-HCT, while CD8 T cells and innate cell concentrations did not differ between groups (Fig. 7B-C). On the contrary, LPS-stimulated release of IL-12, IL-17A and TNF was decreased in patients receiving fludarabine + treosulfan (Supplementary Material Figure S10). The distribution of CD4/CD8 donor/recipient chimerism was similar between groups (Supplementary Material Figure S11).

Secondary study results. Day 28 post-HCT comparison of patients undergoing the myeloablative (MA) conditionings; Combined fludarabine + treosulfan (n = 35) compared to patients receiving “other” MA regimens (n = 15): cyclophosphamide + total body irradiation (TBI), etoposide + TBI or fludarabine + busulfan. (A) Distribution of CD3/CD28-stimulated between fludarabine + treosulfan and “other” MA regimens. (B) Stacked barplots of cell percentages. (C) Immune cell concentrations between groups. Boxplots of log-transformed cell concentrations. Significance levels: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Grey rectangles represent normal reference ranges.

Sex-specific differences in stimulated cytokine release and immune cell concentrations

No differences were found when comparing either stimulated cytokine release or immune cell concentrations between males and females in the main study cohort (Supplementary information file 2 table S10, Supplementary Material Figures S12 & S13).

Discussion

For patients undergoing peripheral blood-derived hematopoietic cell transplantation, those receiving NMA conditioning exhibited reduced post-HCT cytokine release following both T cell stimulation (CD3/CD28) and innate immune stimulation (LPS; R848), compared to patients receiving MA conditioning. This suggests an overall impairment or dysregulation of immune function in the NMA group during early immune reconstitution. In parallel, post-HCT concentrations of all major immune cell lineages, except neutrophils, were lower in patients who received NMA conditioning. However, only specific innate immune cell subsets were associated with cytokine production after innate stimulation. In contrast, no clear associations were observed between T cell concentrations and cytokine release after T cell stimulation, suggesting that the observed differences in immune function between MA and NMA conditioning post-HCT may be influenced by factors beyond immune cell concentrations.

Secondary analyses found that among patients receiving MA conditioning regimens, patients treated with combined fludarabine and treosulfan had improved post-HCT T cell concentrations and CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release compared to patients receiving the more intense MA conditioning regimens. Interestingly, patients with more intense MA regimens had improved LPS stimulated cytokine release compared to combined fludarabine and treosulfan, while no differences in innate cell concentrations between the groups was observed, which could indicate that fludarabine and treosulfan conditioned patients have improved post-HCT T cell function while either the conditioning itself or other patient characteristics may negatively impact their innate immune function.

The reduced CD3/CD28-, LPS- and R848 stimulated cytokine release observed at day 28 post-HCT in NMA patients who received PBSC grafts was unexpected, since the more toxic conditioning regimens in the MA group were expected to impede immune reconstitution and function compared to NMA patients. Our findings of a general improvement of LPS- and R848-stimulated cytokine release early after transplantation compared to before conditioning is initiated are in line with a previous study of stimulated cytokine responses in patients undergoing allo-HCT14. Factors affecting the observed differences in immune function post-HCT are multi-faceted. Age-related changes are amongst other possible contributors to the functional T cell disparity in NMA compared to MA patients receiving PBSC grafts. Where mixed chimerism is present, senescent or damaged immune cells still persisting at day 28 could play a part in the reduced T cell stimulated response22,23. Since patients receiving NMA conditioning were generally older than MA patients with a median age increase of 15 years, poorer function of the bone marrow niche could also be a contributing factor24 albeit that damage of the bone marrow niche leading to reduced cellularity has previously been shown to be more pronounced in MA conditioned patients25. Functional differences could also reflect the T cell targeted immune suppressive treatments given to prevent development of GVHD26. In the main study cohort, MA patients received either Tac combined with MTX, while the NMA patients received combined CsA, MMF and sirolimus, but whether the differences in GVHD prophylactic measures contributed to CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release is unknown. MMF and sirolimus both target the cell cycle of lymphocytes27so the reduced CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release in NMA patients could be an effect of their GVHD prophylaxis which combines both calcineurin and cell cycle targets in T cells. The specific effect of these drug combinations on stimulated whole blood cytokine release is also unknown. Infectious complications and antimicrobial treatments that are administered in response to infections or as prophylactic measures also affect the post-transplantation immunity due to the complex interaction between the commensal microbiota, conditioning, applied antimicrobial treatments and the immune system28,29where associations with allo-HCT complications such as GVHD have previously been shown30,31.

The observed differences in immune function between the conditioning regimens must be partially determined by immune cell concentrations within each group. While overall T cell concentrations, including CD4 and CD8 subsets, were expectedly reduced at day 28 compared to levels prior to conditioning, the NMA patients had lower post-HCT concentrations of T cells, including CD4 and CD8 subsets, B cells, NK cells, and monocytes in the main study cohort. Multiple studies have described the typical progression of T cell immune reconstitution after allo-HCT in both adult and pediatric patients32,33,34,35but the relation of cell function and concentrations has been less rigorously studied.

Functional immune reconstitution after allo-HCT has been studied in recent years. One study found that cell damage due to reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated DNA damage was associated with T cell dysfunction further leading to increased immune evasion of the underlying often malignant hematological primary condition and poorer outcomes for patients, but the underlying cause and possible relations to conditioning remain unclear36. In our study, analyzing immune cell concentrations and stimulated cytokine release associations with linear modelling revealed multiple univariate associations between immune cell concentrations and CD3/CD28-, LPS-, and R848-stimulated cytokine release. However, multivariate modeling, adjusted for multiple immune cell subset concentrations, revealed that CD3/CD28-stimulated IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-17 were independent of cell concentrations. This observation, also considering the observed low correlations between CD3/CD28-stimulated cytokine release and immune cell concentrations, implies that the functional disparities between conditioning regimens after CD3/CD28-stimulation cannot solely be explained by concentrations of T cells or other major immune cell lines.

Notably, in multivariate analyses of MA conditioned patients, NK cells and monocytes were positively associated with cytokine release following R848 and LPS stimulation. In contrast, neutrophils showed an unexpected negative association with cytokine responses to both stimuli, although the effect sizes were small. The positive associations between NK cells and monocytes, and innately stimulated cytokine release in both conditioning groups emphasize the importance of these cells for immune function in patients during early post-HCT reconstitution. Of note are the associations observed between NK cells and R848-stimulated IFN-α and IFN-γ in MA patients persisted in both univariate and multivariate analysis. NK cells express TLRs and their activation by pathogen associated molecular patterns play important roles in combatting infectious diseases37. In allo-HCT, NK cell reconstitution has been implicated in GvL-effect and relapse free survival32,38 and has been shown to be associated with lower TRM, fewer cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections and better overall survival39. Innate immune reconstitution has also been shown to affect reconstitution of CD4 T cells35 again highlighting the interplay between innate and adaptive cell subsets post-HCT.

Day 28 post-HCT donor chimerism distribution displayed an expected pattern of high day 28 donor CD4/CD8 donor chimerism for MA patients while NMA patients were more evenly distributed across the donor chimerism ranges. Modelling of chimerism and stimulated cytokine release only revealed a single association between CD3/CD28-stimulated IL-10 release and donor CD4 T cell chimerism in NMA patients. This indicates that while the amount of active immune cells originating from either the donor and/or the recipient has profound impact on the progress of the transplantation procedure and outcomes i.e. relapse and overall survival40 chimerism does not seem to be greatly involved in the stimulated cytokine release. While the observed variation in T cell chimerism cannot inherently explain the observed functional T cell disparities, having a larger proportion of mixed CD4 chimerism around day 28, has previously been connected to allo-tolerogenicity in post-HCT NMA patients41.

The discovery of elevated post-HCT T cell reconstitution and improved T cell function in MA conditioning with fludarabine and treosulfan compared to more intense regimens was surprising. Both fludarabine + treosulfan and conditioning regimens with combined chemotherapy and high-dose TBI are considered as MA, but combined fludarabine and treosulfan is also classified as a reduced toxicity conditioning regimen due to the regimen displaying MA properties42 but with toxicity profiles matching reduced intensity conditioning43. While toxicity from the applied chemotherapy must play a major role in immune reconstitution in all MA conditioning regimens, a contributing factor to the observed differences in T cells could be TBI-related damage to the recipient’s bone marrow niche leading to increased treatment toxicity44.

Distribution of distinct T cell subsets such as exhausted or PD-1 positive phenotypes could also contribute to the observed impaired function. T cells with PD-1 overexpression, have been implicated in reduced anti-tumor activity with differing immune profiles observed between CD4 and CD8 T cells45. The reduced levels of T cell stimulated IFN-γ, IL-10 and IL-17A observed in NMA compared to MA patients, could indicate dysfunction in or lack of specific CD4 T cell effector subsets such Th1, Treg or Th17 cells in NMA patients. Reconstitution of other immune cell types such as γδ T cells have also been implicated in reduced incidence of relapse as well as improved OS and relapse-free survival after allo-HCT46. Previous studies have investigated functional immune reconstitution post-HCT using T-cell proliferation assays, ELISPOT, tetramer assays, and CMV/EBV viral-specific responses using cytokine secretion assays47. Functional T cell impairment against post-HCT fungal and viral infectious agents has previously been described48 and measurement of functional CMV-specific T cell immune responses between conditioning regimens using e.g. IFN-γ-ELISpot assays has been applied as a component of evaluating immune reconstitution49 and the risk of relapse50 post-HCT.

This study was limited by being a single-center study with a relatively low number of study participants. However, several findings from a previous study at our institution14 were reproduced i.e. the observed changes in stimulated and unstimulated cytokine output between before conditioning and around day 28 after allo-HCT. Patient characteristics were well balanced between MA and NMA patients, but the heterogeneity of variable combinations of the included patients impedes interpretation. Steroid treatment had been administered for aGVHD in 5 patients at sampling time around day 28 but was equally distributed between MA (n = 3) and NMA (n = 2) patients. Further stratification of patients into for example toxicity-based groups RTC and non-RTC groups within MA conditioning regimens, as well reduced intensity and other NMA groups in future studies could lead to better understanding of the different effects conditioning has on the patient’s immune system post-HCT. The observed unstimulated IL-8 concentrations, which could originate from either the plasma compartment or ‘smoldering’ cells taken at sampling, could produce elevated IL-8 output in Poly I:C stimulated samples, due to the low cytokine output reference range of this specific stimuli. The presence of cytokine-autoantibodies was not measured and could also affect the cytokine output as shown in a previous study51.

In conclusion, these results show that patient immune profiling using multimodal assessment with combined functional and descriptive modalities can reveal underlying differences between patients receiving different transplantation conditioning regimens. However, the task of uncovering connections between these findings and clinical outcomes remains. If connections with clinical outcomes are detectable, the applied assays could lead to information that could help identifying patients at risk of allo-HCT complications.

Data availability

Due to Danish privacy regulations, the clinical data supporting the conclusions of this study can only be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Duarte, R. F. et al. Indications for Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: Current practice in europe, 2019. Bone Marrow Transpl. 54, 1525–1552 (2019).

Gyurkocza, B. & Sandmaier, B. M. Conditioning regimens for hematopoietic cell transplantation: One size does not fit all. Blood 124, 344–353 (2014).

Salas, M. Q. et al. Outcomes of antithymocyte Globulin-Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide-Cyclosporine-Based versus antithymocyte Globulin-Based prophylaxis for 10/10 HLA-Matched unrelated donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transpl. Cell. Ther. 30, 1–13 (2024).

Giralt, S. et al. Reduced-Intensity conditioning regimen workshop: Defining the dose spectrum. Report of a workshop convened by the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 15, 367–369 (2009).

Spyridonidis, A. et al. Redefining and measuring transplant conditioning intensity in current era: A study in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Bone Marrow Transpl. 55, 1114–1125 (2020).

Oudin, C. et al. Reduced-toxicity conditioning prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation improves outcome in patients with myeloid malignancies. Haematologica 99, 1762–1768 (2014).

Shimoni, A. et al. Fludarabine and treosulfan: A novel modified myeloablative regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation with effective antileukemia activity in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk. Lymphoma. 48, 2352–2359 (2007).

Gagelmann, N. & Kröger, N. Dose intensity for conditioning in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: Can we recommend when and for whom in 2021? Haematologica 106, 1794–1804 (2021).

Cooper, J. P. et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with non-myeloablative conditioning for patients with hematologic malignancies: improved outcomes over two decades. 106, 1599–1607 (2021).

Troullioud Lucas, A. G. et al. Early immune reconstitution as predictor for outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant; a tri-institutional analysis. Cytotherapy 25, 977–985 (2023).

Ogonek, J. et al. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front. Immunol. 7, 1–15 (2016).

Yanir, A., Schulz, A., Lawitschka, A., Nierkens, S. & Eyrich, M. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic Haematopoietic cell transplantation: From observational studies to targeted interventions. Front. Pediatr. 9, 1–25 (2022).

Bertaina, A. et al. An ISCT stem cell engineering committee position statement on immune reconstitution: The importance of predictable and modifiable milestones of immune reconstitution to transplant outcomes. Cytotherapy 24, 385–392 (2022).

Gjærde, L. K. et al. Functional immune reconstitution early after allogeneic Haematopoietic cell transplantation: A comparison of pre- and post-transplantation cytokine responses in stimulated whole blood. Scand. J. Immunol. 94, 1–11 (2021).

Brennan, T. V., Rendell, V. R. & Yang, Y. Innate immune activation by tissue injury and cell death in the setting of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front. Immunol. 6, 1–9 (2015).

Hill, G. R., Betts, B. C., Tkachev, V., Kean, L. S. & Blazar, B. R. Current concepts and advances in Graft-Versus-Host disease immunology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 39, 19–49 (2021).

Koreth, J. et al. Donor chimerism early after reduced-intensity conditioning hematopoietic stem cell transplantation predicts relapse and survival. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 20, 1516–1521 (2014).

Pettersson, L. et al. Development and performance of a next generation sequencing (NGS) assay for monitoring of mixed chimerism. Clin. Chim. Acta. 512, 40–48 (2021).

Drabe, C. H. et al. Immune function as predictor of infectious complications and clinical outcome in patients undergoing solid organ transplantation (the immunemo:sot study): A prospective non-interventional observational trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 1–8 (2019).

Svanberg, R. et al. Early stimulated immune responses predict clinical disease severity in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Commun. Med. 2, 1–15 (2022).

Ronit, A. et al. Compartmental immunophenotyping in COVID-19 ARDS: A case series. J Allergy Clin. Immunol 147, (2021).

Gorgoulis, V. et al. Cellular senescence: defining a path forward. Cell 179, 813–827 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Immunosenescence: molecular mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther 8, (2023).

Matteini, F., Mulaw, M. A. & Florian, M. C. Aging of the hematopoietic stem cell niche: new tools to answer an old question. Front. Immunol. 12, 1–21 (2021).

Wilke, C. et al. Marrow damage and hematopoietic recovery following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute leukemias: effect of radiation dose and conditioning regimen. Radiother Oncol. 118, 65–71 (2016).

Gooptu, M. & Antin, J. H. G. V. H. D. Prophylaxis Front. Immunol. 12, 1–13 (2021). (2020).

Hamilton, B. K. Current approaches to prevent and treat GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Hematol. (United States) 228–235 (2018). (2018).

Gea-banacloche, J. T. & Infections Transpl. Infect. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28797-3. (2016).

Miller, M. & Singer, M. Do antibiotics cause mitochondrial and immune cell dysfunction? A literature review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 77, 1218–1227 (2022).

Miller, H. K. et al. Infectious risk after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation complicated by acute Graft-versus-Host disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 23, 522–528 (2017).

Gjærde, L. I., Moser, C. & Sengeløv, H. Epidemiology of bloodstream infections after myeloablative and non-myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A single-center cohort study. Transpl Infect. Dis 19, (2017).

Minculescu, L. et al. Improved Relapse-Free survival in patients with high natural killer cell doses in grafts and during early immune reconstitution after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol 11, (2020).

Velardi, E., Tsai, J. J. & van den Brink, M. R. M. T cell regeneration after immunological injury. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 277–291 (2021).

Dekker, L., de Koning, C., Lindemans, C. & Nierkens, S. Reconstitution of t cell subsets following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancers (Basel). 12, 1–21 (2020).

de Koning, C., Plantinga, M., Besseling, P., Boelens, J. J. & Nierkens, S. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in children. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 22, 195–206 (2016).

Karl, F. et al. Oxidative DNA damage in reconstituting T cells is associated with relapse and inferior survival after allo-SCT. Blood 141, 1626–1639 (2023).

Noh, J. Y., Yoon, S. R., Kim, T. D., Choi, I. & Jung, H. Toll-Like Receptors in Natural Killer Cells and Their Application for Immunotherapy. J. Immunol. Res. (2020). (2020).

Mushtaq, M. U. et al. Impact of natural killer cells on outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 13, 1–13 (2022).

Minculescu, L. et al. Early natural killer cell reconstitution predicts overall survival in T cell–Replete allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 22, 2187–2193 (2016).

Reshef, R. et al. Early donor chimerism levels predict relapse and survival after allogeneic stem cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 20, 1758–1766 (2014).

Kinsella, F. A. M. et al. Mixed chimerism established by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is maintained by host and donor T regulatory cells. Blood Adv. 3, 734–743 (2019).

Ruutu, T. et al. Reduced-toxicity conditioning with Treosulfan and fludarabine in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndromes:final results of an international prospective phase II trial. Haematologica 96, 1344–1350 (2011).

Sakellari, I. et al. Survival advantage and comparable toxicity in Reduced-Toxicity Treosulfan-Based versus Reduced-Intensity Busulfan-Based conditioning regimen in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia patients after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantatio. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 23, 445–451 (2017).

Hill, G. R. & Koyama, M. Cytokines and costimulation in acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood 136, 418–428 (2020).

Simonetta, F. et al. Dynamics of expression of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) on T cells after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front Immunol 10, (2019).

Minculescu, L. et al. Improved overall survival, relapse-free-survival, and less graft-vs.-host-disease in patients with high immune reconstitution of TCR gamma delta cells 2 months after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Front. Immunol. 10, 1–18 (2019).

Van Den Brink, M. R. M., Velardi, E. & Perales, M. A. Immune reconstitution following stem cell transplantation. Hematol. (United States). 2015, 215–219 (2015).

Mehta, R. S. & Rezvani, K. Immune reconstitution post allogeneic transplant and the impact of immune recovery on the risk of infection. Virulence 7, 901–916 (2016).

Naik, S. et al. Toward functional immune monitoring in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 26, 911–919 (2020).

Mathioudaki, A. et al. The remission status of AML patients after allo-HCT is associated with a distinct single-cell bone marrow T-cell signature. Blood 143, 1269–1281 (2024).

von Stemann, J. H. et al. Cytokine autoantibodies are stable throughout the Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation course and are associated with distinct biomarker and blood cell profiles. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–10 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the nursing staff and transplantation coordinators at the Department of Hematology and biomedical technicians and academic staff at the Department of Clinical Immunology, Rigshospitalet. This study was partly funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation Borregaard Grant received by S.D.N. in 2015 and S.R.O. in 2020. Figure 1 was Created in BioRender. Ostrowski, S. (2025) https://BioRender.com/28qxbcs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.T.B collected, analyzed, and interpreted data, and authored the manuscript. R.S.T., H.J.H., J.A.S., L.S.F., B.K., I.S., S.L.P., N.S.A., J.L., and H.M. interpreted data and authored the manuscript. L.M. and L.K.G., supervised the study, interpreted the data, and authored the manuscript. S.D.N., H.S. and S.R.O. conceived, designed, and supervised the study, interpreted the data, and authored the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the Capital Region, Denmark (approval nr H-17024315). All study participants gave informed written consent before inclusion.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brooks, P.T., Minculescu, L., Svanberg Teglgaard, R. et al. Functional immune reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in myeloablative and non-myeloablative conditioned patients. Sci Rep 15, 21029 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06718-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06718-y