Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in various animal species, including dogs. While human-to-animal transmission has been documented, the extent and distribution of SARS-CoV-2 exposure in dogs across the United States of America (USA) remain unclear. To address this need, we investigated the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in dogs in the USA and scanned for spatial and temporal clusters of high seroprevalence. Serum samples from 953 dogs from 37 states were screened by serological assays, and 58 (6.09%) samples tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The lowest seropositivity was detected in the third quarter of 2021 (1.16%), while the highest was in the third and fourth quarters of 2024 (23.26%). Maps visualized the distribution of seroprevalence, and the Pacific Northwest and Florida had high seroprevalence, while the Northeast and Midwest USA had low seroprevalence. Two significant space–time clusters were identified. The primary cluster in areas in the state of Washington in October 2024, and the secondary cluster in Florida in March 2022. These findings highlight the importance of surveillance to understand SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology in companion animals and its implications for public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged in late 2019 in Wuhan and poses a significant threat to public health1,2. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the family of Coronaviridae in the order Nidovirales, which are enveloped viruses with a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome around 30 kilobases3,4. SARS-CoV-2 can infect many animal species, including wild and domestic cats and dogs5,6,7. Recent studies have revealed that dogs, compared to cats, are less susceptible to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and develop milder clinical symptoms and humoral responses, however, they are still susceptible to the virus under high-exposure settings8,9,10,11. Certain high-risk owner-pet interactions, such as kissing the pets or allowing them to sleep on the bed, have been associated with an increased risk of viral exposure and transmission12. Therefore, household dogs, besides cats, can also be considered as a potential sentinel species for human-to-animal transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

SARS-CoV-2 has been reported to be able to transmit from humans to animals, including cats and dogs13,14. Previous studies showed that dogs in contact with people with COVID-19 become asymptomatically infected, and some showed low levels of viral RNA in their nasal swabs15. Since pet animals can potentially transmit SARS-CoV-2 to humans16, monitoring the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 exposure in household pet populations is needed.

Surveillance studies focusing on SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in pet populations could provide information on viral spillover events from animals and potential reservoirs that could facilitate viral evolution17,18. However, most current surveillance studies on SARS-CoV-2 infections in dog populations are geographically limited and have small sample sizes. A comprehensive and large-scale epidemiological study is needed to evaluate the spatial and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 exposure in the household dog population across the United States of America (USA).

To achieve our study objective, we conducted serological surveillance of household dogs to determine the prevalence and distribution of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies across the USA in four periods (Period 1: July 29, 2021-March 12, 2022; Period 2: March 13, 2022- April 7, 2022; Period 3: April 8, 2022-May 4, 2022; Period 4: September 23, 2024-October 18, 2024). We identified seropositive cases using serological assays and applied spatial and space–time cluster analysis to determine locations and periods with higher-than-expected SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in dog populations. Our study could aid public health stakeholders in understanding the dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 exposure in companion animals.

Results

Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in dogs

A total of 953 serum samples were collected across the USA (248 cities from 37 states) and tested for SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies (Suppl. Table 1). 58 dog serum samples (6.09% had specific antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 (Suppl. Table 2). Samples were collected between July 2021 and October 2024 at various periods, involving two diagnostic laboratories from Washington and New York state.

Table 1 displays the seropositivity distribution of dogs across sampling periods. The fourth period (2024 Q3- 2024 Q4) had the highest positivity rate (n = 10, 23.26%), while the first period (2021 Q3) had the lowest (n = 1, 1.16%).

To address the uneven distribution of samples collected over time and better evaluate the temporal trends in SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity among household dogs, we applied a Poisson regression model to compare the number of seropositive cases across different sampling periods while adjusting for the total number of tests conducted in each period. Instead of analyzing by year, we categorized the dataset into distinct sampling periods to account for variations in sample size distribution across time, in which the time frames that did not have sample collection (8/9/2021–2/25/2022; 5/4/2022–9/22/2024) were excluded from the analysis. The rest of the time from 7/29/21 to 10/18/2024 was evenly divided into four periods, including 7/29/2021–3/12/2022 (Period 1), 3/13/2022–4/7/2022, (Period 2), 4/8/2022–5/4/2022 (Period 3), 9/23/2024–10/18/2024 (Period 4). Period 1 was used as the reference category. Serum samples from New York state were collected during Periods 1–3, while samples from Washington state were collected during Period 4.

The Poisson regression analysis showed an increase in the incidence rate ratio (IRR) of SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity over the study periods (Fig. 1). Compared to period 1, period 2 (IRR: 2.32; 95% CI 1.03–5.20; p = 0.042), and period 4 (IRR: 7.91; 95% CI 3.12–20.03; p < 0.01) had significantly higher seropositivity rates. Period 2 (IRR; 1.94; 95% CI 0.84–4.47; p = 0.118) was not different from period 1.

Variation in SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity among household dogs in the USA across sampling periods. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) of SARS-CoV-2 seropositive cases was estimated using the Poisson regression model, with Period 1 as the reference category. Error bars in each period represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs). An IRR > 1 represents an increase, and an IRR < 1 represents a decrease in the IRR compared to the first period.

Disease mapping

We further evaluated the spatial distribution of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in household dogs across the USA. Point-based maps were generated to visualize the locations of seropositive cases and seropositivity rates at each location. Locations at the city level were plotted based on their geographic latitude and longitude coordinates. The seropositivity rate and the number of seropositive samples were illustrated in choropleth point maps (Fig. 2A,C). The number of seropositive samples ranged from 0 to 5 (Fig. 2A), and the seropositivity rate ranged from 0 to 100% (Fig. 2C).

Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 seropositive household dogs across the USA. Point maps illustrate the distribution of the number of seropositive cases (A) and seropositivity rates (C) by city. The darker color represents a higher seropositive case number or rate. Isopleth maps illustrate the spatially interpolated distribution of the number of seropositive cases (B) and seropositivity rates (D) across the USA by using the Empirical Bayesian kriging method. ArcGIS Pro version 3.4 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI), Redlands, CA, USA) software was used to construct the map and perform the spatial interpolation.

The locations with the highest number of seropositive cases were in Boca Raton City and Palm Beach County, in the state of Florida, with 5 seropositive cases. The lowest seropositive case numbers with no positive test results were observed in 203 cities from 37 states. In terms of the total number of tests among cities, Palm Beach County had the highest number of tests conducted (n = 47), followed by Harrison in Ohio (n = 45), Montgomery in Maryland (n = 35), Bergen in New Jersey (n = 33), and Madison in New York (n = 23).

The highest seropositivity rate was found in Carroll and Frederick in Maryland, Los Angeles in California, Polk in Iowa, Prince George’s in Maryland, Saratoga and Seneca in New York, and King, Spokane, Walla Walla, Whitman, and Yakima counties in the state of Washington, with 100% seropositivity rate. The lowest seropositivity was observed in 203 cities with a 0% rate.

The interpolated number of seropositive cases (Fig. 2B) and seropositivity rates (Fig. 2D) were illustrated in isopleth maps. Seropositive case numbers were high in the Western USA, the Midwest, the Northeast, and Florida. The high seropositivity rates were located in the same regions as the number of seropositive cases, except in Florida, which had a 7.5% seropositivity (8 seropositive cases of 107 samples tested).

Global and local spatial cluster analysis

To evaluate the spatial clustering of SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity in household dogs across the USA, global and local spatial clustering analyses were conducted. The global spatial clustering was assessed by the Incremental Spatial Autocorrelation (Global Moran’s I), to identify the intensity (Z-score values) and significance (p-values) of global autocorrelation at incremental distances (Suppl. Table 3). As shown in Fig. 3 and Supplemental Table 3, the maximum peak (where the Z-score (z = 8.711) was at peak and started to decrease) was identified at 123.4 km. This suggests a strong global spatial clustering pattern of SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity at this distance among tested dogs.

Incremental Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibody seropositivity in household dogs. Thirty incremental distances were included in the analysis. The distance bands were established according to the average nearest-neighbor distance among locations. Z-scores represent the intensity of spatial clustering of cases. The higher values of Z-scores represent stronger autocorrelation. The maximum peak Z-score was observed at 123.4 km, showing the optimal distance at which clustering effects are most significant. The fixed distance band conceptualization parameter was used. Statistically significant clustering at p ≤ 0.05.

The 123.4 km distance band and the zone of indifference conceptualization of spatial relationship parameter were applied in subsequent local spatial cluster analysis, to balance proximity-based weighting with neighboring influences, where the locations within the specified distance have a maximum weight, and the weight decreases as this distance is passed.

Local spatial clustering was evaluated using the Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi)*, which identifies statistically significant clusters of high (hot spots) and low (cold spots) seropositivity rates. Hot spots are locations where dogs exhibit high SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence, surrounded by neighboring areas with similarly high seroprevalence. Conversely, cold spots are locations of low seroprevalence and are surrounded by areas with comparably low seroprevalence. The analysis revealed several cities in the Pacific West of the USA as significant hot spots (P-value < 0.01), where the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was higher than in surrounding areas (Fig. 4). In addition, in the Western USA, two locations in California, and one location in Montana and Utah were also identified as hot spots (P-value < 0.01). Conversely, several cold spots were identified in the eastern USA, indicating areas of low seroprevalence surrounded by similarly low-seroprevalence regions.

Hot spot analysis of the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in household dogs. The Getis-Ord Gi* statistic was applied to identify statistically significant local clusters of SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in household dogs. Hot spots (red-colored locations) are locations where dogs exhibit high SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence, surrounded by neighboring areas with similarly high seroprevalence. Conversely, cold spots (blue-colored locations) are locations of low seroprevalence and are surrounded by areas with comparably low seroprevalence. The distance band of 123.4 km and the zone of indifference conceptualization of spatial relationship parameters were used to identify spatial clustering at p ≤ 0.05. ArcGIS Pro version 3.4 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI), Redlands, CA, USA) software was used to conduct the hot-spot analysis and illustrate the results on the map.

Additionally, Cluster and Outlier Analysis using Local Moran’s I was conducted to identify spatial clusters and outliers of SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in dogs. High-high clusters represent locations where dogs had high seroprevalence and were surrounded by neighboring areas with similarly high values, while low-low clusters indicate locations where dogs had low seroprevalence and were surrounded by other low-seroprevalence areas. Spatial outliers were defined as locations where seroprevalence levels differed from those of surrounding areas. A high-seroprevalence location surrounded by low-seroprevalence areas was defined as a high-low outlier, and the low-seroprevalence location surrounded by high-seroprevalence areas was defined as a low–high outlier. The results revealed 12 locations in the state of Washington and one in California in the western USA as high-high clusters (Fig. 5). Several locations in the states of Florida, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York were identified as high-low outliers (P-value < 0.10), suggesting that they are high-seroprevalence areas surrounded by low-seroprevalence regions. Several low-low clusters were also detected in the eastern USA. A few low–high outlier areas were observed in cities in California, Washington, Utah, and Montana. Several high-low outlier areas were identified in locations across the eastern and midwestern USA.

Cluster and outlier analysis (Local Moran’s I) of SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in household dogs across the USA. High-high clusters (dark red colored locations) were areas with high seroprevalence surrounded by similarly high-seroprevalence areas. Low-low clusters (light blue colored locations) represent locations with low seroprevalence surrounded by other low-prevalence areas. High-low outliers (light red colored locations) were high-seroprevalence areas surrounded by low-seroprevalence areas. Low–high outliers (dark blue colored locations) represented low-seroprevalence areas adjacent to high-seroprevalence locations. The Euclidean distance band of 123.4 km was used to define the distance around the target areas, and the zone of indifference was used as the conceptualization of spatial relationships. Statistical significance was determined at p ≤ 0.05. ArcGIS Pro version 3.4 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI), Redlands, CA, USA) software was used to conduct the cluster and outlier analysis and illustrate the results on the map.

Spatial, and space–time scan statistical analysis

The results of the spatial and space–time scan statistics are shown in Table 2.

The spatial scan analysis detected one significant spatial cluster (SP Cluster 1, p = 0.005), which was located across Washington and Oregon states (Fig. 6; Table 2). This cluster contained 13 observed SARS-CoV-2 seropositive cases, significantly higher than the expected number of 2.74 seropositive cases, resulting in a 5.26 relative risk (RR).

Spatial clustering of high SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in household dogs across the USA. The Poisson model was used with a circular scanning window that included 5% of the population at risk. 999 Monte Carlo permutations and likelihood ratios assessed statistical significance (p < 0.05). The red circle represents the spatial extent of the cluster. Location within the cluster and their relative risks (RR) are illustrated as choropleth points using the ArcGIS Pro version 3.4 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI), Redlands, CA, USA) software.

The space–time scan analysis identified two significant (p < 0.05) clusters (Fig. 7; Table 2). The primary space–time cluster (ST Cluster 1, p = 0.01) occurred between September and October 2024, located in the state of Washington, covering 26 locations with a radius of 255.31 km. This cluster included six seropositive cases, higher than the expected 0.67 seropositive cases. The relative risk (RR) of this cluster is 9.88. This space–time cluster overlapped with the spatial cluster. The secondary space–time cluster (ST Cluster 2, p = 0.02) occurred in March 2022, located in the state of Florida, covering 22 seropositive cases with a relative risk of 14.04, suggesting an intense localized exposure event.

Space–time clustering of SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in household dogs across the USA The Bernoulli model was used with a circular scanning window that included 5% of the population at risk and 5% of the study period. 999 Monte Carlo permutations and likelihood ratios assessed statistical significance (p < 0.05). The circles represent the locations of the identified space–time clusters. ArcGIS Pro version 3.4 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI), Redlands, CA, USA) software was used to illustrate the results of the space–time scan statistics.

Discussion

This study evaluated the seroprevalence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in household dogs across the USA through a large-scale serological surveillance that included several locations and periods between 2021 and 2024. A stepwise spatial analysis was followed to describe the distribution and clustering of dog populations with high SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence.

SARS-CoV-2 has been reported to infect humans and various animal species, including companion animals. Studies have demonstrated that dogs are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infections but have not shown clinical symptoms. Most of the SARS-CoV-2-infected pets had a direct exposure history to a COVID-19-positive person19. The fact that seropositivity rates in dogs mirrored peaks in human COVID-19 case rates suggests that humans can infect dogs20,21. As household dogs are in close contact with humans and other pet animals, understanding their role in SARS-CoV-2 transmission is important for public health and disease surveillance.

In this study, differences in SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in household dogs between four sampling periods were evaluated. The lowest seropositivity rate was observed in period 1 (1.16%), while the other periods had higher seroprevalence rates (6.22% in period 2, 4.80% in period 3, and 23.26% in period 4). This observation was further demonstrated by the finding of the Poisson model, where the last study period had a significantly higher incidence rate ratio compared to the first study period. The differences in seropositivity suggest that SARS-CoV-2 exposure in dog populations fluctuates over periods, potentially corresponding with human infection trends and changes in transmission dynamics or transmissibility of different SARS-CoV-2 variants. The increase in seroprevalence in dogs observed in period 2 (March 2022-April 2022) seems to align with the peak of SARS-CoV-2 infections among humans during the Omicron wave, which resulted in widespread community transmission22. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, the weekly reported COVID-19 cases in Florida peaked during the Omicron wave in January 2022, then sharply declined in March 2022, and showed a small peak in June-July 2022 (Supplemental Figure S1). This finding aligns with the high dog seropositivity observed in our study in early 2022 (Period 2) and lower seropositivity in late spring (Period 3), supporting a possible correlation between human case surges and increased exposure risk in dogs. Dogs in close contact with infected individuals may have had increased exposure during Period 2. The decrease in Period 3 could be attributed to a decline in human cases and the reduced chance of exposure caused by lower virulence and shedding period of the Omicron variant23,24. Interestingly, period 4 exhibited the highest seroprevalence (23.26%), which suggests a higher SARS-CoV-2 exposure among household dogs. This increase correlates with a resurgence of human COVID-19 cases in Washington state during September–October 2024. Since all samples collected during this period originated exclusively from Washington state, the increase in seroprevalence may reflect regional variation rather than a broader national trend.

In this study, a stepwise geospatial analysis was used to understand the distribution and clustering of SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity within domestic dog populations. We first generated disease maps to visualize the number and the rates of seropositivity across multiple cities. Our dataset included dog serum samples collected from 37 states in the USA; however, because our study depended on diagnostic laboratories and their caseload, the distribution of samples was not uniform, as some regions had a higher number of samples, and from some regions, we did not have any submissions. To address potential biases, we constructed isopleth maps using empirical Bayesian kriging to interpolate seroprevalence across the study area25. Notably, the Pacific Northwest region and the Florida peninsula had a high seropositivity, while other areas, particularly in the central and southeastern USA, had a low seropositivity. In addition, we also calculated the proportion of positive samples across different regions to account for variations in sample submissions from different regions. Several regions in the Pacific West of the USA, including parts of Washington and California, displayed high seropositivity rates. Conversely, despite having a high number of seropositive samples, the Florida peninsula and the Northeastern USA exhibited relatively lower positivity rates because of the larger number of overall tests conducted in these regions. The geographic variability of seropositive rates might be explained by different exposure risks to SARS-CoV-2 and pet-human interactions20. In urban areas, the higher population density and more frequent visits to shared public spaces, including public transport systems and veterinary clinics, may create higher direct and indirect contact between infected and susceptible individuals and pets, potentially leading to higher exposures and seropositivity rates than in rural regions.

To further evaluate spatial clustering patterns, we applied first the global and next the local cluster analysis methods. For the conceptualization of spatial relationships, the zone of indifference method was used, assuming that all cities within a specific distance band had the highest weighting, while locations beyond this threshold experienced a rapid decline in spatial influence26,27. The global clustering results showed a statistically significant peak in z-score at 123.4 km, representing that SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence follows a non-random, spatially dependent distribution. The maximum peak represented the scale at which the clustering effect was most pronounced, reflecting the geographic extent of spatial processes influencing SARS-CoV-2 seropositive case distributions.

The first local clustering method included the Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*), which identified statistically significant high-seroprevalence areas (hot spots) and low-seroprevalence areas (cold spots)28. The Pacific Northwest region, particularly locations in the states of Washington and parts of Northern California, showed a strong clustering of high-seroprevalence rate (99% confidence), which was consistent with our previous disease mapping plot. The hotspot areas included major cities such as Seattle, Spokane, and Portland, and these urban centers might serve as hubs of human SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and household dogs in these areas could have higher exposure risks. In contrast, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York, which are located in the Northeastern and Midwestern regions of the USA, exhibited strong cold spot clustering (99% confidence), showing lower seroprevalence compared to surrounding areas. The cold spots observed might show less pet exposure or differences in the demographics of pet ownership and veterinary care in these regions.

To further explore localized clustering patterns, the second analysis included the Local Moran’s I Cluster and Outlier Analysis, which identified the high-high (hotspots) and low-low (cold spots) areas, and also the spatial outliers26. This analysis focuses on whether regions with high seroprevalence are surrounded by similarly high-prevalence areas or if they are outliers within otherwise low-prevalence regions28. Significantly high-high clusters were detected in Seattle and Spokane in the state of Washington, and parts of California near San Francisco. Several low-low clusters were identified in the Mideastern and Southeastern USA, particularly in Wisconsin, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and surrounding areas. Several high-low outliers, where locations had high seroprevalence compared to their surrounding low-prevalence areas, were detected in several major cities in the Midwest and Eastern areas of the USA, including the cities of Boston and Chicago. Low–high outliers were also identified in several cities in Washington state, where areas that had low seroprevalence were surrounded by high-seroprevalence regions. Spatial outlier areas might be caused by differences in local exposure risks that influence SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and in these locations, future studies should assess differences in exposure risk and other factors impacting the epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2.

At the third stage of analysis, in addition to the spatial analysis, we conducted a spatial and space–time scan analysis using the Poisson and Bernoulli models to detect statistically significant clusters of SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity. First, we employed a purely spatial scan statistic, which presumes that the seroprevalence follows a Poisson distribution. In this model, the seropositive case numbers in each location are adjusted by the number of tests performed in that location to account for the sampling effort. A single spatial cluster was identified in the states of Washington and Oregon, where seroprevalence was significantly higher than expected (where 26.67% of the samples tested positive). Next, the Bernoulli model was used to identify space–time clusters. This model includes a case–control comparison (SARS-CoV-2 antibody seropositive vs. seronegative dogs) and identifies locations and periods with high seroprevalence21. Two statistically significant clusters were identified. The primary space–time cluster (ST 1) was detected in locations across the state of Washington in October 2024, covering 26 seropositive cases within a 255.31 km radius. This high seroprevalence in dogs is consistent with the increase in human COVID-19 cases around September and October 2024 in Washington state29. The second space–time cluster (ST 2) was identified in Florida in March 2022, where four seropositive cases were observed among five tested dogs. This increase in seropositivity in dogs correlates with the public health surveillance data from the Florida Department of Health30, in which a distinct peak of human COVID-19 case numbers was found in January 2022. These findings might suggest localized human-to-dog transmission events that might have occurred during these periods. Future studies should test this hypothesis and concomitantly test human and dog samples during a peak in human COVID-19 cases. The overlap between spatial and space–time clusters in Washington State emphasizes the persistence of high seroprevalence among the dog population in this region.

We initially screened all dog serum samples collected by using a blocking ELISA (bELISA) test, and the positive samples were confirmed using a virus neutralization assay and commercial assays (Lumit™ Dx SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassay and cPass™ SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Assay). A small subset of samples had inconsistent results across different assays and were excluded from the analysis. The inconsistency between different assays could be caused by the different targets of the assays. bELISA is made to detect antibodies against the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2. The Lumit™, cPass™, and virus neutralization assays target antibodies against the spike protein. Besides, the variations in serum sample quality and sensitivity of different assays could also lead to inconsistent results. Despite the exclusion of these samples with inconsistent testing results, the conclusions of our study remain unchanged.

It is important to recognize certain limitations of this study. First, because this study relied on samples submitted to diagnostic laboratories, the samples were not evenly distributed across the USA, and certain regions had fewer submissions, or from some regions, samples were not collected. This may have resulted in an over- or underestimation of seroprevalence. Also, there was a time gap in sample collections between 2022 and 2024, in which the sample collection from Washington state was not started until September 2024. Second, the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in dog serum remains unclear, making it difficult to correlate the seropositivity with precise exposure time. Third, our study focused on serological indication of past exposure rather than active viral shedding, and therefore, it does not provide direct evidence of ongoing transmission of different variants. Fourth, it was reported that some dogs exposed to SARS-CoV-2 may not successfully seroconvert and display measurable antibodies8,11. Thus, the seropositive rate may not be accurately correlated to the actual exposure of dogs to SARS-CoV-2.

In conclusion, this study examined the spatial epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroprevalence in household dogs across the USA. High seroprevalence was observed in dog populations during specific periods and in particular geographic locations. Our study results could inform animal and public health stakeholders on the current seroepidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 in dog populations and might guide their mitigation efforts.

Materials and methods

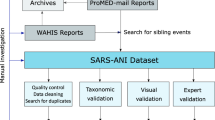

Study design and sample collection

This study is a serological surveillance survey to evaluate the prevalence and spatial–temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in household dogs across the USA. Serum samples were collected between July 2021 and October 2024 from dogs that visited veterinary clinics, animal shelters, and diagnostic laboratories from multiple states across the USA. Metadata for each sample included geographic location (state, county, city), collection date, and test results. Serum samples were excess diagnostic specimens collected during routine veterinary visits. No blood was drawn specifically for this study, and all samples were excess specimens from routine veterinary procedures. All data were anonymized to maintain confidentiality and ensure the pet owner’s privacy.

All sampling methods were performed following the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines and regulations. However, the study included only surplus diagnostic samples, did not involve direct animal participation, and the need to obtain approval was waived by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Serological tests

Serum samples collected from household dogs in this study were tested using blocking enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (bELISA)31, Serum neutralization (SN)7, Lumit™ Dx SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassay (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin), and cPass™ SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Assay (GenScript, Piscataway, New Jersey). All the serum samples collected from the dogs were initially screened by bELISA and SN assay. The bELISA was conducted as we described previously31. Serum neutralization (SN) assay was performed under BSL-3 Laboratory conditions at Cornell University. Serum samples were serially diluted (1:8 to 1:1024) and then incubated with the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral virus (D164G) or Omicron (B.1.1.529) before being added to Vero E6 cell cultures. After 48 h of incubation, the cells were analyzed using an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) to determine the highest serum dilution that was able to completely neutralize viral infection. Samples with dilution titers below 1:8 were classified as negative for neutralizing antibodies. The commercial Lumit™ Dx SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassay or cPass™ SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Assay was conducted following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples that tested positive in both bELISA and SN assays were considered confirmed seropositive. Samples that were positive in only one of the two screening assays (either bELISA or SN) were subsequently tested using one of the two commercial confirmatory assays: Lumit™ Dx SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassay or cPass™ SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization Antibody Detection Assay, depending on kit availability. Only those samples that yielded consistent positive results in commercial confirmatory assays were classified as seropositive and included in the analysis. A total of 58 (out of 953) samples consistently showed positive results in two different assays and were used for subsequent epidemiological analysis (Suppl. Table 2).

Analysis for temporal differences in seroprevalence

We used the Poisson regression model to estimate the incidence rate ratio (IRR) across four different sampling periods to evaluate the difference in SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity in household dogs. Because of the unequal distribution of sample collection time and the absence of samples for the year 2023, we categorized the dataset into four sampling periods, considering the period and the number of samples to be evenly distributed. Four periods were created: 7/29/2021–3/12/2022 (Period 1), 3/13/2022–4/7/2022 (Period 2), 4/8/2022–5/4/2022 (Period 3), 9/23/2024–10/18/2024 (Period 4). Period 1 was used as the reference category. The dependent variable was the number of positive samples in each period, including the number of tests conducted in each period, as an exposure to account for differences in the sampling. The period was included as the independent categorical variable, where period 1 was set as the reference category to which all the other periods were compared. The coefficient was represented by the IRR, where an IRR > 1 signified a higher, and an IRR < 1 a lower seroprevalence. Statistical significance was determined at p ≤ 0.05.

Spatial and temporal cluster analysis

To evaluate the spatial and temporal distribution of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in household dogs, we conducted a stepwise spatial and temporal analysis32. The spatial data were geocoded at the city level based on sample collection locations. ArcGIS Pro version 3.4 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI), Redlands, CA, USA) was used to construct all maps and conduct spatial analysis. Latitude and longitude coordinates for county centroids were assigned. Temporal data were stratified by the sample collection date, allowing for the detection of space–time clusters.

Disease mapping

Using geometrical intervals, a point map was constructed to illustrate the distribution of the city-level seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in household dogs. NAD 1983 UTM Zone 16N was used as the projection for all spatial analysis in this study.

A spatial interpolation of the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies was achieved using the empirical Bayesian Kriging method. This method applied a restricted maximum likelihood estimation and constructed several semivariograms to account for the error when estimating the semivariograms33. The result of the spatial interpolation was illustrated in isopleth maps.

Global spatial cluster analysis

Incremental Spatial Autocorrelation analysis was conducted to evaluate the intensity of SARS-CoV-2 antibody clustering in household dogs at different distances. This method evaluates spatial autocorrelation at multiple distance intervals to identify the scale at which clustering is most pronounced34. The first distance in the distance increments ensures that each location has at least one neighbor, and distances were incrementally increased based on the average nearest neighbor distance. For each distance increment, Moran’s I value, Expected Index, Variance, z-scores, and p-values were calculated to assess the statistical significance of clustering (Supplemental Table S3). Peaks in z-scores indicated the distances at which clustering was most pronounced. The distance where the first statistically significant peak was observed was selected for subsequent local cluster analysis. The zone of indifference for the conceptualization of spatial relationships was used for the local spatial cluster analysis35.

Local spatial cluster analysis

Local spatial cluster analysis was conducted to identify statistically significant clusters of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in household dogs using the Cluster and Outlier Analysis (Anselin Local Moran’s I) and Hot Spot Analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*) methods36.

Hot spot analysis

To identify hotspots and cold spots of SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence, we employed Getis-Ord Gi* statistics by measuring whether high (hot spot) or low (cold spot) seroprevalence areas are spatially clustered. A local value was computed for each geographic unit (city or county) and compared to the overall study region. The results were mapped using color-coded intensity levels representing high-seroprevalence (red) and low-seroprevalence (blue) areas.

Cluster and outlier analysis

To detect clustering patterns and spatial outliers, we performed the Anselin local Moran’s I analysis. The high-high (hot spot) and low-low (cold spot) clusters, as well as high-low and low–high outliers, were identified by comparing the Moran’s I index of the target area to the surrounding areas’ I index values. A hot spot location where a high seroprevalence area was surrounded by a high prevalence area was classified as a high-high area, while cold spots indicated areas with low seroprevalence surrounded by areas with low seroprevalence. Besides these clusters, the analysis identified high-low and low–high outlier areas.

Spatial and space–time scan statistics

Spatial and space–time scan statistics were applied to identify significant clustering patterns of SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in household dogs using SaTScan v9.6 software37. For both models latitude and longitude parameters for each sample location were calculated. The spatial extent was represented by the samples’ location at the city level, and the temporal scale included the month and year of sample collection.

Spatial scan statistics were conducted with a discrete Poisson model. In this analysis, a circular scanning window moved across the study area to detect regions with significantly higher seroprevalence than expected38. The scanning window was set to a maximum of 5% of the population. Monte Carlo simulations (9999 replications) were used to determine the statistical significance (p < 0.05). Spatial clusters were visualized in maps, illustrating the spatial cluster location and the relative risks of areas within the significant cluster.

To identify spatiotemporal clustering, space–time scan statistics were applied using a cylindrical scanning window39, where the circular base represented the space and the height represented time. The Bernoulli model was used, where the SARS-CoV-2 seropositive dogs were included as cases and the negative samples as controls. The maximum spatial cluster size was set to 5% of the population, and 5% of the study time. Monte Carlo simulations (999 replications) were used to ensure statistical accuracy.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Lu, R. et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The Lancet 395, 565–574 (2020).

Hu, B., Guo, H., Zhou, P. & Shi, Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 141–154 (2021).

Hasöksüz, M., Kilic, S. & Saraç, F. Coronaviruses and sars-cov-2. Turkish J. Med. Sci. 50, 549–556 (2020).

Wu, F. et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 579, 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3 (2020).

Mahdy, M. A., Younis, W. & Ewaida, Z. An overview of SARS-CoV-2 and animal infection. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 596391 (2020).

Gaudreault, N. N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, disease and transmission in domestic cats. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 2322–2332 (2020).

Martins, M. et al. The omicron variant BA.1.1 presents a lower pathogenicity than B.1 D614G and delta variants in a feline model of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Virol. 96, e00961-e922. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00961-22 (2022).

Tomeo-Martín, B. D., Delgado-Bonet, P., Cejalvo, T., Herranz, S. & Perisé-Barrios, A. J. A comprehensive study of cellular and humoral immunity in dogs naturally exposed to SARS-CoV-2. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2024, 9970311. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/9970311 (2024).

van Aart, A. E. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in cats and dogs in infected mink farms. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 69, 3001–3007. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14173 (2022).

Dileepan, M. et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) exposure in pet cats and dogs in Minnesota, USA. Virulence 12, 1597–1609. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.1936433 (2021).

Bosco-Lauth, A. M. et al. Experimental infection of domestic dogs and cats with SARS-CoV-2: Pathogenesis, transmission, and response to reexposure in cats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 26382–26388. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2013102117 (2020).

Bienzle, D. et al. Risk FACTORS for SARS-CoV-2 infection and illness in cats and dogs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 28, 1154–1162. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2806.220423 (2022).

Cui, S. et al. An updated review on SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals. Viruses 14, 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14071527 (2022).

Medkour, H. et al. First evidence of human-to-dog transmission of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.160 variant in France. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 69, e823–e830. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14359 (2022).

Sit, T. H. et al. Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2. Nature 586, 776–778 (2020).

Piewbang, C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission from human to pet and suspected transmission from pet to human, Thailand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 60, e01058-e1022. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01058-22 (2022).

Jorwal, P., Bharadwaj, S. & Jorwal, P. One health approach and COVID-19: A perspective. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 9, 5888–5891. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1058_20 (2020).

Castillo, A. P. et al. SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in captive animals at the belo horizonte zoo, Minas Gerais. Brazil. Virol. J. 21, 297. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-024-02505-9 (2024).

Liew, A. Y. et al. Clinical and epidemiologic features of SARS-CoV-2 in dogs and cats compiled through national surveillance in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 261, 480–489. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.22.08.0375 (2023).

Kimmerlein, A. K., McKee, T. S., Bergman, P. J., Sokolchik, I. & Leutenegger, C. M. The transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from COVID-19-diagnosed people to their pet dogs and cats in a multi-year surveillance project. Viruses 16, 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16071157 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Spatial and temporal clustering of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Illinois household cats, 2021–2023. PLoS ONE 19, e0299388 (2024).

Saxena, S. K. et al. Transmission dynamics and mutational prevalence of the novel Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 Omicron Variant of Concern. J. Med. Virol. 94, 2160–2166. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27611 (2022).

Lyoo, K. S. et al. Experimental infection and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 delta and omicron variants among beagle dogs. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 782–785. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2904.221727 (2023).

Sánchez-Morales, L., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J. M., Pérez-Sancho, M., Domínguez, L. & Barroso-Arévalo, S. The Omicron (B.1.1.529) SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern also affects companion animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 940710. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2022.940710 (2022).

Yudhanto, S. & Varga, C. Knowledge and attitudes of small animal veterinarians on antimicrobial use practices impacting the selection of antimicrobial resistance in dogs and cats in illinois, United States: A spatial epidemiological approach. Antibiotics (Basel) 12, 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030542 (2023).

Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 27, 93–115 (1995).

Mitchel, A. The ESRI Guide to GIS analysis, Volume 2: Spartial measurements and statistics. ESRI Guide to GIS analysis 2 (2005).

Varga, C., John, P., Cooke, M. & Majowicz, S. E. Spatial and space-time clustering and demographic characteristics of human nontyphoidal Salmonella infections with major serotypes in Toronto, Canada. PLoS ONE 15, e0235291 (2020).

Health, W. S. D. Respiratory Illness Data Dashboard, <https://doh.wa.gov/data-and-statistical-reports/diseases-and-chronic-conditions/communicable-disease-surveillance-data/respiratory-illness-data-dashboard> (2025).

Health, F. D. Florida COVID-19 Data, <https://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/respiratory-illness/COVID-19/> (2025).

Yuan, F. et al. Development of monoclonal antibody-based blocking ELISA for detecting SARS-CoV-2 exposure in animals. mSphere 8, e00067-e23. https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00067-23 (2023).

Varga, C. et al. Area-level global and local clustering of human salmonella enteritidis infection rates in the city of Toronto, Canada, 2007–2009. BMC Infect. Dis. 15, 359. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-1106-6 (2015).

Krivoruchko, K. Empirical bayesian kriging. ArcUser Fall 6, 1145 (2012).

Thomas, A. & Aryal, J. Spatial analysis methods and practice: Describe–explore–explain through GIS. J. Spatial Sci. 66, 533–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/14498596.2021.1955816 (2021).

Grekousis, G. Spatial analysis methods and practice: Describe–explore–explain through GIS (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Getis, A. & Ord, J. K. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr. Anal. 24, 189–206 (1992).

Kulldorff, M. SaTScan User Guide; 2018. Reference Source 505 (2022).

Kulldorff, M. A spatial scan statistic. Commun. Statist.-Theory Methods 26, 1481–1496 (1997).

Kulldorff, M., Athas, W. F., Feurer, E. J., Miller, B. A. & Key, C. R. Evaluating cluster alarms: A space-time scan statistic and brain cancer in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Am. J. Public Health 88, 1377–1380 (1998).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Tony Vanden Bush from Promega for providing the Lumit™ Dx SARS-CoV-2 Immunoassay kits.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft MN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing CV: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing AN: Investigation, Writing – review & editing HRC: Investigation, Resources; Writing – review & editing MSV: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing NH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing DGD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing YF: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Nooruzzaman, M., Varga, C. et al. Evaluating the distribution and clustering of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in dogs across the United States of America. Sci Rep 15, 21758 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06730-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06730-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in companion animals in Poland during the post-pandemic period (2022–2025)

BMC Veterinary Research (2025)