Abstract

To address the problem of large errors in 3D maps caused by mismatching due to white flares formed through specular reflections on smooth object surfaces during digital image acquisition, we propose applying the polarization principle to filter out the orthogonally polarized component of linearly polarized light in the reflected light, thereby reducing or eliminating the white flare area. The experimental results demonstrate that the system can effectively suppress the flare intensity on nonmetallic surfaces, which mitigates artifacts in 3D reconstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasing adoption of intelligent unmanned workshops, cranes must possess 3D environmental perception capabilities1,2. To achieve autonomous obstacle avoidance, intelligent cranes commonly rely on sensors such as stereo cameras and multiline LiDAR to construct 3D digital maps3,4. Under illumination conditions, smooth surfaces obey the law of specular reflection, directionally reflecting incident light to form a virtual image of the light source. When the camera lens forms a specific angle with the reflective surface, these high-intensity reflected rays enter the optical system. Within the lens, the light undergoes multiple reflections and refractions at air-glass interfaces (such as Fresnel reflections between front and rear lens groups), ultimately reaching the sensor through non-imaging paths. Since the energy density of such reflected light far exceeds the average scene brightness, its superposition on normal imaging paths creates localized overexposed white glare spots (i.e., glare phenomenon) in digital images. The geometric shape of these spots is jointly determined by the number of aperture blades and lens curvature. However, the widespread presence of smooth object surfaces in workshops generates substantial specular reflections5. Under illumination, these reflections form high-intensity bright areas, resulting in numerous white flares on digital images, as illustrated in (Fig. 1). Such flares obscure the intrinsic color and texture details of objects, severely interfering with the stereo matching process during map reconstruction6 and degrading the accuracy of 3D maps. Consequently, the suppression of specular reflections on workshop surfaces has garnered significant attention from researchers worldwide7,8.

Light waves encompass information on intensity, frequency, phase, and polarization, with conventional applications predominantly utilizing intensity and frequency data9. Current 3D mapping methods based on digital images largely neglect the impact of specular reflections on 3D map accuracy10. For flare suppression, researchers predominantly employ machine learning methods to mitigate high-intensity regions caused by specular reflections. Polarization, however, constitutes a critical optical property: any natural object imparts polarization spectral characteristics to reflected or transmitted light, which are determined by its intrinsic properties11. Both specular and diffuse reflections exhibit linear polarization effects, yet their polarization signatures differ significantly. This inherent disparity enables polarization features to provide effective prior information for suppressing specular reflections12. 3D maps reconstructed from polarization-processed images exhibit enhanced accuracy and robustness against varying illumination conditions and surface roughness, as they inherently exclude specular interference.

The application of geometric constraints such as confidence maps and epipolar constraints has achieved promising results in optimizing digital images. Rong et al. proposed a multi-view 3D microscopic ranging system that mitigates optical contamination like multiple reflections by leveraging optimal candidate selection based on epipolar deviation, demonstrating robustness against multi-reflections when testing printed circuit boards with dense components13. Xiangyang et al. introduced a self-correction method to enhance 3D reconstruction in multi-view photogrammetric systems. This approach repairs 3D surfaces damaged by depth discontinuities and can be extended to integrate range images from other depth-sensing devices14. Michael et al. described a method for detecting and mitigating optical contamination when using active stereo cameras. They statistically analyzed one-dimensional data transformed from digital images to identify contamination events15. Xiao et al. addressed spatial non-uniformity in cameras using flat-field correction, employing a 1.5-meter-diameter integrating sphere to provide uniform illumination, thereby resolving pixel-level variations, manufacturing irregularities, and optical contamination16. Bincai et al. developed a dual-media photogrammetric technique for shallow-water bathymetry using satellite-based stereo multispectral imaging. By utilizing the near-infrared band to eliminate solar glare, they obtained more accurate results than traditional multispectral inversion models in water depths of 5–20 m17.

Atkinson et al. employed diffuse polarization to estimate surface normal directions and obtained high-precision images via linear polarizers coupled with digital cameras18. Cui et al. proposed a novel polarization imaging model capable of handling real-world objects with hybrid polarizations. By integrating per-pixel photometric information from polarizations with epipolar constraints from multiview images, their method enhances 3D reconstruction accuracy19. Hao et al. developed a multispectral polarization-based 3D reconstruction framework for highly reflective nonmetallic targets with smooth surfaces and limited textures. Leveraging the distinct polarization and spectral characteristics of stray and diffuse light across different wavelength bands, their preprocessing step effectively removes flares, substantially improving the final reconstruction precision20. Kadambi et al. introduced a framework that uses polarized normal constraints to refine depth maps. Their approach derives surface normals from the degree and orientation of specular polarization, demonstrating significant error reduction in 3D reconstruction under diverse lighting scenarios21. Smith et al. devised a method for direct surface height estimation from single polarization images by solving large-scale linear systems. By requiring only uncalibrated illumination, this approach enables well-posed depth estimation and delivers robust results for glossy objects under uncontrolled outdoor lighting22. Shakeri et al. exploited full polarization cues from polarization cameras to propagate sparse depth values along and perpendicular to iso-depth contours. Experimental validation confirms that their method significantly enhances depth map accuracy and data density in texture-poor regions23. Tan et al. presented a hybrid technique that combines polarization cameras with line-structured light for weld seam localization and 3D reconstruction. By calibrating polarization-derived relative heights against the precise 3D coordinates of laser stripes, this method generates authentic point clouds while mitigating arc interference in laser-based imaging and overcoming polarization-based height ambiguity24.

Effective methods for high-quality 3D reconstruction by fusing polarization data with depth information have also been explored25. Tian et al. proposed a 3D reconstruction model that integrates polarization imaging with stereo vision, along with an efficient solution to the associated optimization problem. Experimental results demonstrate that their method generates 3D reconstructions with fine-grained texture details, underscoring the broad application prospects of polarization imaging in robotics and computer vision26. Liu et al. introduced a 3D reconstruction method that fuses the polarization shape and polarization state-based ranging, enabling simultaneous acquisition of polarization images and depth data from single-image sensor inputs. Their experimental validation further confirmed the method’s robustness in weak-texture scenarios27.

The integration of polarization information with deep learning techniques has also demonstrated remarkable accuracy improvements28,29,30. Ba et al. incorporated polarimetric shape priors into deep neural network architectures. Through experiments conducted across objects with varying textures, paint conditions, and illuminations, their method achieved the lowest test errors under all the evaluated scenarios31. For precise passive 3D facial reconstruction, Han et al. fused 3D polarimetric facial data with convolutional neural networks (CNNs). By obtaining coarse depth maps via a 3DMM-based CNN and refining polarization-induced ambiguous surface normals, their approach delivered highly accurate 3D facial reconstructions32. By targeting outdoor scenes, Lei et al. proposed a framework that combines polarization imaging for scene-level normal estimation with multihead self-attention modules and view encoding. Experimental results validate that this framework resolves polarization ambiguities caused by complex materials and non-Lambertian reflectance33.

This paper analyzes the polarization states of surface-reflected light. By characterizing the distribution patterns of diffuse and specular reflections in parallel and perpendicular orientations, we propose a system that integrates linear polarizing filters to suppress specular noise. Polarization-processed images are then fed into a stereo matching algorithm to generate high-precision 3D digital maps. The workflow is illustrated in (Fig. 2).

This study extends our prior research. In previous work utilizing stereo cameras, we reported that the maximum error in reconstructed 3D maps originated from white flares caused by specular reflections in overhead crane environments. During stereo mapping, the irregular spatial distribution of flares between the left and right images induced mismatching errors34. To address this issue, we introduce a preprocessing step in which applying linear polarizing filters are applied to stereoimages. We systematically investigated how polarization angles, material properties of target objects, and illumination conditions affect flare suppression efficacy and their subsequent accuracy implications for 3D mapping.

Modeling polarization States of surface reflections

Light reflected from object surfaces consists of specularly reflected polarized light \({I_{\text{S}}}\) and diffuse reflected light \({I_{\text{D}}}\)35. The diffuse component \({I_{\text{D}}}\) can be further divided into diffuse polarized light \({I_{{\text{Dp}}}}\) and diffuse unpolarized light \({I_{{\text{Dunpplar}}}}\), as illustrated in (Fig. 3).

-

(1)

Specularly reflected polarized light \({I_{\text{S}}}\): Specularly reflected polarized light is generated by the direct reflection of external light sources from smooth object surfaces. As described by the Fresnel reflection laws, when a light wave undergoes specular reflection, it transitions from natural light to polarized light, with its polarization direction perpendicular to the plane of incidence.

-

(2)

Diffuse polarized light \({I_{{\text{Dp}}}}\): Diffuse polarized light arises from external light sources that enter the interior of an object, undergo refraction through internal molecular/atomic structures, and subsequently reemerging at the surface. The refracted polarized light exhibits a polarization direction parallel to the plane of incidence.

-

(3)

Diffuse unpolarized light \({I_{{\text{Dunpolar}}}}\): Diffuse unpolarized light is generated by rough object surfaces reflecting ambient illumination. Owing to the stochastic orientation of surface microfacets, this diffuse component remains unpolarized, retaining the characteristics of natural light.

we present a polarization state characterization model that combines specular and diffuse reflections by analyzing the polarization transmission processes of specularly reflected light and diffusely reflected light during reflection, and employing the method of orthogonal polarization decomposition.

Linear polarization has a fixed direction of oscillation. Any wave with partial or no polarization can be described as a superposition of two waves with orthogonal polarization directions. Typically, one polarization direction is defined as the electric field E oscillating perpendicular to the plane of incidence (referred to as transverse electric polarization, or TE polarization), and the other as the electric field oscillating parallel to the plane of incidence (referred to as transverse magnetic polarization, or TM polarization).

For TE polarization, the electric field E is perpendicular to the plane of incidence defined by the material’s surface normal vector n and the wave vector k of the incident wave. The electric field lies within the material’s surface plane (i.e., the case of perpendicular incidence), while the magnetic field vector H ies within the plane of incidence, as illustrated in (Fig. 4). For TM polarization, the electric field E lies within the plane of incidence defined by the surface normal vector n and the wave vector k. Here, E has no component tangential to the material’s surface (i.e., the case of parallel incidence), and the magnetic field vector H lies tangential to the material’s surface.

The Fresnel equations for TE cases are shown in Eq. (1).

Where \(\alpha\) is the incident angle, \(\beta\)is the refracted angle, \({E_{{\text{in}}}}\) is the electric field strength of the incident light, \({E_{{\text{ref}}}}\) is the electric field strength of the reflected light, and \({E_{{\text{tr}}}}\) is the electric field strength of the refracted light.

The Fresnel equations for TM cases are shown in Eq. (2).

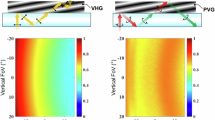

The problem of glare elimination involves the transition of light from a material with lower density to one with higher density, i.e., \({n_1}<{n_2}\). Taking the example of air (with refractive index \({n_1}=1\) ) entering a high-density material (assuming refractive index \({n_2}=2\)), the plotted curves of relative field strength \(E/{E_0}\)versus incident angle \(\alpha\) are shown in (Fig. 5), while the relative intensity \({(E/{E_0})^2}\) versus incident angle \(\alpha\) is illustrated in (Fig. 6).

The analysis reveals that under TM polarization, when the incident angle \(\alpha\) equals the Brewster angle \({\alpha _{\text{B}}}\), the relative field strength \(E/{E_0}\) drops precisely to zero. In this polarization state, no reflection occurs—all incident light is entirely transmitted. If the incoming light consists of randomly polarized waves, the TM-polarized component will not be reflected; consequently, any reflected light will be purely TE-polarized.

The specularly reflected polarized light from object surfaces is partially polarized and can be decomposed into the sum of light intensities in the TE polarizationand TM polarizationrelative to the plane of incidence.

Here, \({I_{{\text{S1}}}}\)and \({I_{{\text{S2}}}}\) denote the perpendicular and parallel light intensity components of the specularly reflected light, respectively; \({R_1}\)and \({R_2}\) represent the perpendicular and parallel reflectivity coefficients; \({P_{\text{S}}}\) corresponds to the illumination intensity of the light source; and \(\theta\) indicates the reflection angle.

The degree of polarization arising from the specular reflection process is defined as:

Similarly, diffuse polarized light can also undergo orthogonal polarization decomposition as follows:

Here, \({I_{{\text{Dp1}}}}\)and \({I_{{\text{Dp2}}}}\) denote the perpendicular and parallel light intensity components of the diffuse polarized light, respectively; \({\varepsilon _1}\)and \({\varepsilon _2}\) represent the perpendicular and parallel directional emissivities; and \({P_{\text{D}}}\) corresponds to the illumination intensity of the refracted light source.

According to Kirchhoff’s law and the law of energy conservation, the sum of the reflectivity and emissivity equals unity for opaque surfaces:

The degree of polarization for diffuse polarized light is defined as:

For diffuse unpolarized light, since the light intensity is isotropic across all directions, it follows that:

Here, \({I_{{\text{Dunpolar}}1}}\) and \({I_{{\text{Dunpolar2}}}}\) denote the perpendicular and parallel light intensity components of the diffuse unpolarized light, respectively.

The intensity of specularly reflected polarized light is predominantly distributed in the perpendicular direction relative to the plane of incidence, exhibiting strong polarization effects. Near the Brewster angle, the degree of polarization reaches unity36. In contrast, diffuse polarized light primarily aligns in the parallel direction, and its degree of polarization increases with the observation angle30. Specular reflections from object surfaces manifest as white flares in digital images. On the basis of the analysis of surface-reflected light components, these flares can be suppressed by blocking specularly reflected polarized light by polarizing filters.

A linear polarizing filter is an optical device capable of selectively transmitting or blocking light waves oscillating in specific orientations. Its operational principle exploits the polarization phenomenon–the restriction of light wave oscillations to a single plane. Through specialized materials and microstructures, linear polarizing filters modulate the polarization states of incident light, thereby filtering rays on basis of their oscillation directions37. As illustrated in (Fig. 7), these filters transmit only light aligned with their polarization axis.

Figure 8 illustrates the workflow of the proposed 3D mapping methodology. First, a disparity map is obtained from stereo images via a block-matching algorithm. The depth map is subsequently derived by applying the triangulation principle to the disparity map. Finally, the depth information from the depth map is reprojected into 3D space to generate the point cloud.

Figure 9 shows the schematic diagram of the binocular stereo matching principle. A sliding window traverses the right-view image while calculating the matching cost between pixels within the window and those in windows at every possible position along the corresponding row of the left-view image. For each position, a matching cost value is computed, which collectively forms a matching cost map. Within a predefined disparity range, the algorithm searches for the disparity value that minimizes the matching cost, which is then assigned as the final disparity for that window. The detailed workflow of the 3D mapping methodology and stereo matching algorithm, along with experimental validations, are described in our previously published work34.

Experiment

Research on polarization-based 3D mapping systems for reflective scenarios in overhead crane environments involves addressing 3D modeling challenges under harsh illumination conditions. Owing to the absence of suitable public datasets for validating this problem, we constructed an experimental testbed to evaluate the proposed methodology. Key variables affecting modeling accuracy, including the polarization angle, surface properties (e.g., material roughness), and illumination intensity, were systematically controlled, with the accuracy of the generated 3D digital maps serving as the primary evaluation metric. The experimental results were subjected to error quantification, followed by a comprehensive analysis of the factors influencing the reconstruction performance.

To validate the efficacy of the proposed methodology, an experimental testbed was constructed, as illustrated in (Fig. 10). The setup comprises a rotary lens stage, linear polarizing filters, stereo cameras, and a base platform. The rotary lens stage is mechanically coupled with linear polarizing filters, maintaining a fixed relative position while enabling rotational adjustments. An angular scale engraved on the stage surface provides precise polarization angle alignment. The linear polarizing filters are employed to selectively attenuate incident light on the basis of its polarization state. The stereo cameras capture polarization-filtered images and transmit the binocular data to a computational unit for 3D map reconstruction. The base platform secures all the components to prevent positional deviations that could introduce measurement errors.

The experimental workflow is depicted in (Fig. 11). Upon initiating the experiment, the polarization angle of the linear polarizing filters is set by rotating the rotary lens stage. After adjusting to a predefined angle, stereo images are captured and processed to generate corresponding 3D maps. This procedure is repeated until 3D maps reacquired across all preset polarization angles. To validate the flare suppression performance under varying surface conditions, the object material is systematically replaced, and the process is reiterated until 3D maps for all the tested surface materials are obtained. The illumination intensity of the ambient light source is subsequently modulated to assess the method’s robustness under different lighting conditions. Following the completion of data acquisition across all combinations of lighting intensities, surface materials, and polarization angles, comprehensive error analysis is performed on all the reconstructed 3D maps to quantify the reconstruction accuracy and identify influential factors.

The experimental equipment and corresponding performance parameters are detailed in (Table 1).

The experiment was conducted according to the following steps.

Experimental preparation

Power activation

The light source is powered on, and the stereo cameras are connected to the laptop via USB 3.0 data cables.

Parameter initialization

Set the polarization angle of the linear polarizing filters and the illumination intensity of the light source to predefined values (e.g., 0°, 2000 lx).

Target placement

Position the test objesct within the 3D mapping coverage of the stereo cameras.

Experimental operation

Polarization angle adjustment

Rotate the adjustment ring on the rotary lens stage to align the polarization angle with the graduated scale.

Illumination calibration

Measure the ambient light intensity via a high-precision lux meter and fine-tune the adjustable light source to maintain the target illuminance.

Results analysis

Point cloud visualization

Open the reconstructed point cloud files (*.pcd) in the PCL Viewer (pcl_viewer) for qualitative inspection.

Quantitative error analysis

Compute the normalized error using the ground-truth distances and reconstructed depth values.

Experiments were conducted following the proposed procedure via the experimental testbed described in this study. With the horizontal direction as the reference axis, the linear polarizing filters in front of the camera lenses were rotated to 0, 30, 60, and 90°. Polarized images at these four angles were captured and labeled I0, I30, I60, and I90. The resulting left-camera images from the stereo setup are shown in (Figs. 12, 13, 14 and 15), where the original photos were cropped to retain only the experimental material regions relevant for glare suppression analysis.

Under an illumination intensity of 2000 lx, the reconstructed point clouds of the ceramic, plastic, metal, and wood surfaces are shown in (Fig. 16). To highlight the impact of glare-induced mismatches, texture-weak objects were selected as the mapping targets.

An analysis of the point cloud experimental results under 2000 lx illumination was performed, where the depth values (Z-direction) of the mapped objects were used as variables to derive the normalized errors for the test materials, as shown in (Fig. 17).

From the experimental results shown in (Figs. 12, 13, 14 and 15), it is evident that under identical illumination conditions, the proposed system effectively suppresses glare on nonmetallic surfaces such as ceramics and plastics. However, metallic surfaces exhibit microscopic irregularities and oxide layers that scatter incident light, introducing complexity to reflection behavior. These phenomena deviate from the assumption of Fresnel theory, resulting in discrepancies between theoretical predictions and practical outcomes. Consequently, accurate prediction and control of specular reflections on metallic surfaces remain challenging for the system. In contrast, wooden surfaces, owing to their high roughness, exhibit predominantly diffuse reflections in the visible spectrum, eliminating intense glare without requiring polarization filtering.

This study systematically evaluates the performance of the linear polarization filtering system for 3D mapping in reflective environments. The experimental variables include the polarization angles (0, 30, 60, 90°), surface materials (ceramic, plastic, metal, wood), and illumination intensities (1500–3000 lx). Quantitative error analysis of the point clouds was performed via pcl_viewer.

Impact of surface material properties

Nonmetallic materials (ceramic and plastic) exhibit significant glare suppression effects after polarization filtering, as shown in (Figs. 9 and 10). For instance, under 2000 lx illumination, the normalized error of the ceramic point cloud decreases from 15.5 to 0.7%. This improvement stems from the effective attenuation of specularly polarized light (perpendicular to the incidence plane) by linear polarizing filters, which aligns with the multispectral polarization-based glare suppression mechanism proposed by Hao et al.20.

In contrast, metallic surfaces suffer from multiple scattering due to microscopic oxide layers, leading to substantial deviations in specular polarization states that exceed the applicability of Fresnel theory. Moreover, wooden surfaces, characterized by high roughness, diffuse over 95% of reflected light, enabling glare-free point cloud reconstruction without polarization processing.

Optimization of illumination intensity and polarization angle

The experimental results reveal a nonlinear coupling effect between the illumination intensity and the polarization angle. When the illumination intensity exceeds 2500 lx, specular reflections on ceramic and plastic surfaces exhibit varying degrees of saturation, diminishing the polarization filtering efficiency. Analysis via the geometrically constrained polarization-normal model (Atkinson et al.18) demonstrated that the optimal polarization angle depends on the material’s refractive index (n), with 60° achieving maximal glare suppression.

Error sources and robustness

The primary error sources include the following: (a) Insufficient disparity resolution: Due to the stereo camera’s baseline distance (65 mm), depth errors increase by 1.8× at distances > 2 m. (b) Polarizer angle calibration accuracy (± 2°): Induces transmittance fluctuations.(c) NonUniform illumination: Causes localized overexposure, particularly in high-reflectance regions.

Method limitations

The system exhibits limited efficacy in suppressing glare on highly reflective metallic surfaces, which is consistent with the inherent constraints of polarization imaging under strong specular reflections noted by Yang et al.5. Future enhancements could integrate multispectral polarization (Hao et al.20) or deep polarization neural networks (Ba et al.31) to improve the reconstruction accuracy.

Innovation points and conclusions this paper addresses the challenge of specular reflection interference degrading 3D mapping accuracy in reflective environments typical of overhead crane operations. A linear polarization filtering-based 3D mapping system is proposed to mitigate such interference, the key innovations are as follows:

Polarization filtering-based specular reflection suppression mechanism

By analyzing the polarization characteristics of surface-reflected light, we propose using a linear polarizing filter to selectively block specularly reflected polarized light (predominantly vertically polarized) while preserving diffusely reflected polarized light (primarily horizontally polarized). This approach effectively eliminates white glare artifacts in digital images. Through polarization-direction filtering, it significantly reduces interference from reflections in binocular stereo matching.

Illumination-polarization angle coupling optimization for multi-material surfaces

Experimental results demonstrate the dynamic correlation between polarization angles and material refractive indices, identifying 60° as the optimal polarization angle for non-metallic surfaces. By adjusting the nonlinear coupling effect between illumination intensity (e.g., 2000 lx) and polarization angles, we optimize 3D mapping accuracy. The system performs exceptionally well on ceramic and plastic surfaces (normalized error reduced from 15.5 to 0.7%), though further improvements are required for metallic surfaces due to Fresnel theory limitations.

Integrated binocular vision and polarization preprocessing for 3d mapping system architecture

We propose a novel system framework combining block-matching algorithms with polarization filtering, comprising: polarized image acquisition, noise reduction processing, depth map generation, and 3D point cloud reconstruction. Bench tests validate performance across various polarization angles, materials, and lighting conditions, delivering an anti-glare 3D perception solution for industrial applications (e.g., bridge cranes) while enhancing mapping robustness in textureless regions.

Through theoretical analysis and experimental validation, the system effectively suppresses white flares caused by specular reflections on smooth surfaces, significantly enhancing the precision and robustness of 3D reconstruction. The key conclusions are summarized as follows:

Efficacy of polarization-driven glare suppression

By leveraging the polarization state disparity between specular and diffuse reflections, the linear polarizing filters effectively attenuate high-intensity glare in images by blocking vertically polarized specular light. The experimental results demonstrate that on nonmetallic surfaces (e.g., ceramic and plastic), the system achieves significant suppression of disparity mismatches induced by glare, with robustness across varying illumination intensities (1500–3000 lx) and polarization angles (0–90°). This mechanism provides a theoretical foundation for addressing glare issues on smooth industrial surfaces such as ceramics and plastics.

Performance evaluation of the 3D mapping system

By integrating polarization preprocessing with stereo vision and block-matching algorithms, the system reduces point cloud reconstruction errors by ≈ 76% compared with conventional methods on nonmetallic surfaces. For instance, the normalized error of ceramic point clouds decreases from 15.5 to 0.7%. However, metallic surfaces exhibit limited glare suppression due to microscopic oxide layers and complex scattering behaviors that invalidate Fresnel theory. Conversely, rough surfaces such as wood inherently lack glare owing to dominant diffuse reflections, validating the system’s material-dependent adaptability.

Industrial application value

The proposed system offers a viable 3D perception solution for digitalized industrial environments such as overhead crane operations. By mitigating glare-induced stereo matching errors, it enhances positioning accuracy and operational safety in reflective scenarios.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Luo, X., Leite, F. & O’Brien, W. J. Requirements for autonomous crane safety monitoring, in Computing in Civil Engineering, Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers, doi: https://doi.org/10.1061/41182(416)41. (2011).

Qing, D., Youcheng, S., Gening, X., Lingjuan, S. & Ze, W. Posture configuration optimization method and system for folding booms of the pump truck under life extension control. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99484-w (2025).

García, J. M., Martínez, J. L. & Reina, A. J. Bridge crane monitoring using a 3D lidar and deep learning. IEEE Lat Am. Trans. 21 (2), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLA.2023.10015213 (2023).

Hassan, M. U. & Miura, J. Sensor pose Estimation and 3D mapping for crane operations using sensors attached to the crane boom. IEEE Access. 11, 90298–90308. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3307197 (2023).

Yang, G. & Wang, Y. Three-dimensional measurement of precise shaft parts based on line structured light and deep learning. Measurement 191, 110837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2022.110837 (2022).

Jialin, W. et al. Polarization suppression reflection method based on Mueller matrix. Acta Opt. Sin. 43 (20), 2012003. https://doi.org/10.3788/AOS230572 (2023).

Van der Jeught, S. & Dirckx, J. J. J. Deep neural networks for single shot structured light profilometry. Opt. Express. 27 (12), 17091. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.27.017091 (2019).

Chen, G., Han, K., Shi, B., Matsushita, Y. & Wong, K. Y. K. Deep photometric stereo for Non-Lambertian surfaces. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44 (1), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3005397 (2022).

Miyazaki, T. & Ikeuchi Hara, and Polarization-based inverse rendering from a single view. In Proceedings Ninth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2, 982–987 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2003.1238455 (IEEE, 2003).

Li, X., Liu, F. & Shao, X. P. Research progress on polarization 3D imaging technology. J. Infrared Millim. Waves. 40 (2), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.11972/j.issn.1001-9014.2021.02.016 (2021).

Wei, Z. & Xia, J. Recent progress in polarization-sensitive photodetectors based on low-dimensional semiconductors. Acta Phys. Sin. 68, 163201. https://doi.org/10.7498/aps.68.20191002 (2019).

Smith, W. A. P., Ramamoorthi, R. & Tozza, S. Height-from-Polarisation with unknown lighting or albedo. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 41 (12), 2875–2888. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2868065 (2019).

Dai, R., Tang, X., Li, W. & Liu, Y. H. Self-Correcting and Globally-Consistent 3D Cross-Ratio invariant model for Multi-View microscopic profilometry. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 21 (3), 2373–2382. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2024.3507177 (2025).

Ju, X. et al. Self-correction of 3D reconstruction from multi-view stereo images. In 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops 1606–1613 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCVW.2009.5457422 (IEEE, 2009).

Schoenberg, M. & Wang, C. Methods of detecting and mitigating light contamination in active Stereo-Cameras. Defensive Publ. Ser. 1–10 (2019).

Liang, X. et al. The navigation and terrain cameras on the Tianwen-1 Mars Rover. Space Sci. Rev. 217 (3), 37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-021-00813-y (2021).

Cao, B., Fang, Y., Jiang, Z., Gao, L. & Hu, H. Shallow water bathymetry from WorldView-2 stereo imagery using two-media photogrammetry. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 52 (1), 506–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/22797254.2019.1658542 (2019).

Atkinson, G. A. & Hancock, E. R. Recovery of surface orientation from diffuse polarization. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 15, 1653–1664. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2006.871114 (2006).

Cui, Z., Gu, J., Shi, B., Tan, P. & Kautz, J. Polarimetric multi-view stereo. In Proceedings – 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, 369–378 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.47 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2017).

Hao, J., Zhao, Y., Zhao, H., Brezany, P. & Sun, J. 3D reconstruction of High-reflective and textureless targets based on multispectral polarization and machine vision. Acta Geod. Cartogr. Sin. 47 (6), 816–824. https://doi.org/10.11947/j.AGCS.2018.20170624 (2018).

Kadambi, A., Taamazyan, V., Shi, B. & Raskar, R. Depth sensing using geometrically constrained polarization normals. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 125, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11263-017-1025-7 (2017).

Smith, W. A. P., Ramamoorthi, R. & Tozza, S. Linear depth Estimation from an uncalibrated, monocular polarisation image, in Computer Vision – ECCV 2016, Springer, Cham, 109–125. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46484-8_7. (2016).

Shakeri, M., Loo, S. Y., Zhang, H. & Hu, K. Polarimetric monocular dense mapping using relative deep depth prior. IEEE Robot Autom. Lett. 6 (3), 4512–4519. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2021.3068669 (2021).

Tan, Z. et al. A welding seam positioning method based on polarization 3D reconstruction and linear structured light imaging. Opt. Laser Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2022.108046 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Yi, C., Kong, S. G., Pan, Q. & Cheng, Y. Multi-band polarization Imaging. J. Sens. 47–71 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-49373-1_3 (2016).

Tian, X., Liu, R., Wang, Z. & Ma, J. High quality 3D reconstruction based on fusion of polarization imaging and binocular stereo vision. Inf. Fusion. 77, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2021.07.002 (2022).

Liu, R., Liang, H., Wang, Z., Ma, J. & Tian, X. Fusion-based high-quality polarization 3D reconstruction. Opt. Lasers Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlaseng.2022.107397 (2023).

Poggi, M., Tosi, F., Batsos, K., Mordohai, P. & Mattoccia, S. On the synergies between machine learning and binocular stereo for depth Estimation from images: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44 (9), 5314–5334. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3070917 (2022).

Deschaintre, V., Lin, Y. & Ghosh, A. Deep polarization imaging for 3D shape and SVBRDF acquisition. In 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 15562–15571 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01531 (IEEE, 2021).

Li, Z., Xu, Z., Ramamoorthi, R., Sunkavalli, K. & Chandraker, M. Learning to reconstruct shape and spatially-varying reflectance from a single image. In SIGGRAPH Asia 2018 Technical Papers, SIGGRAPH Asia 2018 https://doi.org/10.1145/3272127.3275055 (Association for Computing Machinery, Inc, 2018).

Ba, Y. et al. Deep shape from polarization, in Computer Vision – ECCV 2020, Springer, Cham, 554–571. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58586-0_33. (2020).

Han, P. et al. Accurate passive 3D polarization face reconstruction under complex conditions assisted with deep learning. Photonics https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics9120924 (2022).

Lei, C. et al. Shape from polarization for complex scenes in the wild. In 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and (CVPR) 12622–12631 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01230 (IEEE, 2022).

Zhao, K., Zhou, Q., Xiong, X. & Zhao, J. The construction method of the digital operation environment for Bridge cranes. Math. Probl. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5528639 (2021).

Zou, S. et al. 3D human shape reconstruction from a polarization image. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2020 351–368 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58568-6_21 (Springer, 2020).

Li, X. et al. Polarization 3D imaging technology: a review. Front. Phys. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2023.1198457 (2023).

Zhang, D. W., Li, M. & Chen, C. F. Recent advances in circularly polarized electroluminescence based on organic light-emitting diodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (5), 1331–1343. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9cs00680j (2020).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Taiyuan University of Science and Technology Scientific Research Initial Funding (Grant No. 20222142) and the Open Fund Project (Grant No. 2023KF004) of the National Key Laboratory for Market Regulation (Crane Safety Technology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Z and H.Q wrote the main manuscript text, C.G performedthe data analysis and L.J did data visualization, All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, K., Qiu, H., Gao, C. et al. Glare suppressed 3D mapping system based on linear polarization filtering and binocular vision fusion. Sci Rep 15, 20998 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06887-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06887-w