Abstract

Canned pickled cucumbers, tomato paste, and olives are three commonly consumed products in Iranian households that may be a source of heavy metals for individuals due to the type of packaging. Therefore, in this study, samples of these three types of food were collected from the market and were measured for mineral and heavy metal content. The levels of metals including Cadmium, Copper, Arsenic, Iron, Lead, and Zinc were determined using an AAS- Flame and Graphite furnace. Moreover, the concentrations of Mercury and Tin were determined using the ICP-MS. In canned cucumber samples, only two metals, tin and lead, were detected. The levels of heavy metals in these three products were compared using statistical tests. A significant difference was observed in the amount of cadmium (p < 0.05). The average lead content in these three products was above the permissible limit. The levels of copper, arsenic, iron, cadmium, zinc, mercury, and tin in the canned food samples were found to be within the acceptable limits set by national and international regulatory authorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Minerals and heavy metals are non-biodegradable substances that have the potential to accumulate in the environment and food1,2,3. These components can enter the human body through inhalation, oral ingestion, and skin exposure4. Minerals, such as sodium (Na), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), potassium (K), and phosphorus (P), play a crucial role in promoting human health5. On the other hand, heavy metals including mercury (Hg), tin (Sn), lead (Pb), arsenic (As), and cadmium (Cd) can pose significant health risks even at low concentrations6,7. These metals have been demonstrated to induce both acute and chronic poisoning in humans8. The metals mentioned induce oxidative stress within cells, leading to an increase in oxidative damage. This damage affects lipids, proteins, and DNA molecules, ultimately leading to cancer development9. Heavy metals originate from natural sources or as a result of anthropogenic activities10,11. Both of these processes contaminate the environment and food. Natural activities such as volcanic eruptions lead to the release of metals into soil and surface water12. Recently, there has been a significant increase in human exposure from anthropogenic activities13,14. The anthropogenic activities include industrial, mining, transport and agricultural activities, which are major sources of heavy metals15,16. One of the most important sources of human exposure to heavy metals is through food17,18. Food can become contaminated with heavy metals in several ways. One of the major causes of food contamination with heavy metals comes from the environment17. Other factors that cause food contamination with heavy metals include food processing and packaging19,20. One of the most common packaging and food technology is canning21. Heavy metals in canned food can migrate into the food contents of the cans22,23. Canned foods may contain heavy metal residues due to factors such as soldering (Sn, Pb), migration from metal packaging, and contamination during processing24. In a study, the levels of heavy metals in a variety of canned food products were measured. Lead levels ranged from 0.002 to 2.84 mg/kg and cadmium levels ranged from 0.03 to 0.65 mg/kg25. In another study, lead levels in canned foods were measured in the range of 1.40 to 1.76 mg/kg, above the established limit26.

Determining these compounds in foods plays an important role in increasing food safety27. The 2013 priority list of hazardous substances from the US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) ranked As, Pb, Hg, and Cd as the first, second, third, and seventh most critical elements, respectively28,29. Canned tomatoes30olives31and pickles32 can be mentioned among the most commonly used canned foods in Iranian households. Therefore, assessing the safety of these products is essential. This study aims to investigate the metals including lead, copper, arsenic, iron, tin, zinc, mercury, and cadmium in these products.

Materials and methods

Materials and sample collection

49 samples of canned tomatoes, olives, and pickled cucumbers from the 5 most popular brands were collected from stores in Tehran. All samples were transported to the chemistry laboratory. According to standard protocols, all samples were stored in a clean and dry place until digestion and analysis33.

All chemicals used were of analytical reagent grade. Ultrapure water was used with a Milli-Q system (Millpore, Bedford, MA, USA). All plastic and glassware were cleaned by soaking 24 h in 10% (v/v) HNO3. After cleaning, all containers were rinsed three times with ultrapure water. Stock solutions of each metal (1000 mgL−1 in 10% HNO3) were obtained from (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) to prepare standard solutions for calibration curves and spiked to samples. The necessary working standards were prepared according to the linear range listed in Table 1 by diluting the stock standard with ultrapure water.

Sample Preparation and digestion

First, the contents of the sample cans were homogenized for more accurate assessment and to facilitate subsequent digestion. The next step was the digestion procedure, to break the matrix, one gram of each sample was weighed and placed into a 150 mL beaker. Slowly and in portions, 50 mL of a freshly prepared mixture of H2O2 (30%) and HNO3 (65%) in a 1:1 ratio (v: v) was added to the beaker. The beakers were covered with watch glasses and heated on a hot plate until the solution became clear. The resulting clear solution was filtered into a flask using a vacuum system with a 0.45 μm pore size filter. To clean up and modify the solution, phosphoric acid (170 µL) was added to each tube and then shaken using a tube-shaker6,20.

Instrumental analysis

The levels of metals, including Cu, Fe, and Zn were determined using flame atomic absorption spectroscopy and Cd, As, Pb, were determined using graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (Shimadzu AA-6300). And the concentrations of Hg and Sn were determined using the ICP-MS (The Agilent ICP-MS 7500-Ce).

The hollow cathode lamp of metal was operated at 10 mA with the spectral bandwidth of 1 nm. The selected wavelength in AAS methods was 324.7, 248.3 and 213.9 nm for Cu, Fe and Zn, and 228.8, 193.7 and 217.0 nm for Cd, As and Pb respectively.

Determination of each metal was performed using the calibration curve by the measurement device. The accuracy of the method was checked and confirmed by spiking the standard material to the sample and calculating the related recovery (Table 1). The validation parameters are shown in Table 1. For calculation Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ), blank samples are read ten times, and the average and standard deviation (SD) are calculated. LOD for the determination of analyte was calculated based on CLOD=3SD/m (where CLOD, SD and m are the limit of detection, standard deviation of the blank, and slope of the calibration graph (, and LOQ based on 10 Sd/m. All analysis was performed in triplicates. The quality control (QC) and quality assurance (QA) analytical approach was conducted by evaluating prepared spiked standard solutions to the blank sample, on a standard protocol. The results for QC/QA analyses were presented in Table 1.

Results

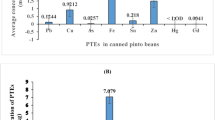

This study investigated the levels of lead, copper, arsenic, iron, tin, zinc, mercury, and cadmium in canned pickled cucumbers, tomato paste, and olives. Table 2 shows the level of heavy metals and minerals tested. Two metals, tin and lead, were observed in all canned goods. All metals except mercury were detected in canned tomato paste samples. Mercury was not detected in all tomato paste, pickled cucumber, and olive samples. Lead was observed in all samples, with the highest levels observed in canned pickle samples.

Statistical analysis was also performed and significant differences between groups were calculated. Data distribution was checked with the Shapiro-Wilk test, and because the data did not have a normal distribution, Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests were used. No significant difference (P > 0.05) was observed between the lead amount in the three types of canned food (Fig. 1).

However, a significant difference was observed between the levels of cadmium between canned foods (P ≤ 0.05). The cadmium in tomato paste was significantly higher than canned olives and pickles (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the Kruskal-Wallis test showed no significant difference between canned pickled cucumbers, tomato paste, and olives regarding other metals levels (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The current research investigated the levels of various heavy metals, including Cd, Cu, As, Fe, Pb, Zn, Hg, and Sn, present in commonly consumed canned food products such as pickled cucumbers, tomato paste, and olives. Food contact with packaging materials can be a source of exposure to chemical compounds34. The type of these chemical compounds depends on the structure and materials used in the packaging. In present study, all metals except iron and lead were not detected in canned pickle cucumbers samples (Table 2). According to the present study, the average and standard division of lead in canned pickled cucumbers were found to be 0.22 ± 0.08 mg/kg. According to the Codex standard, the permissible limit of lead in canned products is 0.1 mg/kg35. Therefore, the results in this study were above the limit established of lead in canned products. In research conducted by Jannat et al. (2021), fifty samples of pickled cucumbers were bought and evaluated by the polarography method. They reported the mean level of cadmium and lead was slightly above the limit established by Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC). The amount of cadmium was higher than in the present study, but the amount of lead in the study of Jannet et al. was lower than in the present study36. Furthermore, the previous study conducted by Afrooz et al. (2024), showed that pickled cucumbers had the highest mercury levels among all acidic food products35. Unlike the present study, mercury was not detected in canned pickle samples. One of the significant differences between the levels of heavy metals in pickles is the type of water used to irrigate the cucumbers37. Experimentally, cucumbers were irrigated with drinking water and wastewater. Copper, cadmium, lead, nickel and chromium were measured in the resulting pickled cucumbers. The levels of these metals were ND in the pickled cucumbers of the first group, but measurable levels were detected in the second group, where the cucumbers used in the pickled cucumbers were irrigated with wastewater37.

Another canned food product examined in this study was canned tomato paste. In the present study, the amount of cadmium detected was 0.008 ± 0.005 mg/kg. According to the Codex standard, the permissible limit of cadmium for some plants, including fruiting vegetables, is 0.05 mg/kg. Therefore, the cadmium level was below the permissible limit. A study by Raptopoulou et al. (2012) used electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry to analyze several heavy metals present in canned tomato paste. The results showed that the concentration of Cd exceeded the maximum permissible level of 0.05 mg/kg38. Cadmium metal is a toxic metal that leads to carcinogenesis, increased blood pressure, and kidney damage39,40. Also, a study in 2016 reported concentrations of Cd and Fe in tomato samples exceeded the legal limits41. Arsenic was detected in canned tomato paste samples. This metal is a toxic and carcinogenic compound42. However, trace amounts were detected in canned tomato paste. The study conducted in Ghana analyzed canned tomato paste samples to detect the levels of heavy metals including Fe, Zn, Hg, Cd, and Pb by using flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Unlike the current study, cadmium was below the LOD, but mercury was detected in canned tomato samples43. The present study showed that the lead content in canned tomato paste was 0.19 ± 0.07 mg/kg that this amount is more than acceptable. Male infertility, damage to the nervous system, decreased learning in children, and anemia are some of the toxic effects of exposure to lead39. The result of the lead level was contrary to the findings of the study by Hadiani et al. (2014). They analyzed samples of canned purchased tomato paste. Levels of lead and all metals were below national and international standards30. Additionally, another study investigated the concentration of heavy metals in canned tomato paste in Nigeria. The authors of this study reported the lead content in all samples, ND44.

Reports indicate the presence of tin in various types of canned foods45. A thin layer of tin is usually added to cans to prevent corrosion46. The acceptable limit of tin in canned foods is 200 mg/kg according to European Union regulations, and 150 to 250 mg/kg according to Codex Alimentarius standards47. In our study, the amount of tin in canned tomato paste was 0.41 ± 0.21 mg/kg, which is lower than the standards level. Similar results to this research were observed in many studies. Morte et al. (2012) measured tin levels in canned tomato sauce storage at room temperature (20.0 ± 1.8 °C) for 0 to 150 days. The tin content increased by 43–91% after 150 days, but it remained well below the maximum level allowed of 250 mg/kg48. Tin determination in canned foods by flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS) showed the amount of tin in tomato pastes and black olives was non-detectable49.

The level of metals in the canned olive product was also measured. In our study, we found that the average and standard deviation of lead levels in canned olives was 0.19 ± 0.04 mg/kg. Therefore, the lead content in canned olives was higher than the permissible limit. Similarly, Shariatifar et al. (2022), conducted a study on lead levels in both industrial and traditional canned olive samples from various regions in Iran. They utilized inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) for their analysis. The industrial samples showed an average lead concentration of 0.26 mg/kg50. Also, in the Karatasli study in Turkey, the lead level in olive samples was measured at 4.55 mg/kg, which was higher than in the present study51. Our study showed the level of cadmium in canned olives was 0.005 ± 0.001 mg/kg, which is below the permissible amount set by the EU.

Conclusion

This study was conducted to investigate the presence of minerals and heavy metals including Cd, Cu, As, Fe, Pb, Zn, Hg and Sn in canned pickles cucumbers, tomato paste and canned olives. Only two metals, tin and lead, were detected in canned pickles. The amount of metals in canned tomato paste was higher than other canned products. Mercury was not detected in all samples. All the determined levels except lead were within the limits declared by Codex Alimentarius and the European Union. Therefore, continuous and ongoing monitoring is recommended to determine the amount of heavy metals, especially lead. Furthermore, the origin of heavy metals from packaged materials may be from other components of food ingredients such as salt and spices, which is recommended for future research.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sarker, A. et al. Heavy metals contamination and associated health risks in food webs—a review focuses on food safety and environmental sustainability in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(3), 3230–3245 (2022).

Hussain, I. et al. Effect of metals or trace elements on wheat growth and its remediation in contaminated soil. J. Plant Growth Regul. 42(4), 2258–2282 (2023).

Peirovi-Minaee, R., Alami, A., Esmaeili, F. & Zarei, A. Analysis of trace elements in processed products of grapes and potential health risk assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31(16), 24051–24063 (2024).

Jaishankar, M., Tseten, T., Anbalagan, N., Mathew, B. B. & Beeregowda, K. N. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip Toxicol. 7(2), 60–72 (2014).

Godswill, A. G., Somtochukwu, I. V., Ikechukwu, A. O. & Kate, E. C. Health benefits of micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) and their associated deficiency diseases: A systematic review. Int. J. Food Sci. 3(1), 1–32 (2020).

Massadeh, A. M. & Al-Massaedh, A. A. T. Determination of heavy metals in canned fruits and vegetables sold in Jordan market. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 25(2), 1914–1920 (2018).

Karimi, A. et al. Assessment of human health risks and pollution index for heavy metals in farmlands irrigated by effluents of stabilization ponds. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 10317–10327 (2020).

Witkowska, D., Słowik, J. & Chilicka, K. Heavy metals and human health: possible exposure pathways and the competition for protein binding sites. Molecules 26(19), 1–16 (2021).

Mahurpawar, M. Effects of heavy metals on human health. Int. J. Res. Granthaalayah. 3, 1–7 (2015).

Ahogle, A. M. A. et al. Heavy metals and trace elements contamination risks in peri-urban agricultural soils in Nairobi City catchment, Kenya. Front. Soil. Sci. 2, 1048057 (2023).

Peirovi-Minaee, R., Taghavi, M., Harimi, M. & Zarei, A. Trace elements in commercially available infant formulas in iran: determination and Estimation of health risks. Food Chem. Toxicol. 186, 114588 (2024).

Saidon, N. B., Szabó, R., Budai, P. & Lehel, J. Trophic transfer and biomagnification potential of environmental contaminants (heavy metals) in aquatic ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 340, 122815 (2024).

Real, M. I. H., Azam, H. M. & Majed, N. Consumption of heavy metal contaminated foods and associated risks in Bangladesh. Environ. Monit. Assess. 189, 651 (2017).

Neisi, A. et al. Consumption of foods contaminated with heavy metals and their association with cardiovascular disease (CVD) using GAM software (cohort study). Heliyon 10, (2). (2024).

Ohiagu, F. O., Chikezie, P., Ahaneku, C. & Chikezie, C. Human exposure to heavy metals: toxicity mechanisms and health implications. Mater. Sci. Eng. 6(2), 78–87 (2022).

Ali, M. M., Hossain, D., Khan, M. S., Begum, M. & Osman, M. H. Environmental pollution with heavy metals: A public health concern. In Heavy metals-their environmental impacts and mitigation, IntechOpen: (2021).

Munir, N. et al. Heavy metal contamination of natural foods is a serious health issue: A review. Sustainability 14(1), 161 (2021).

Peirovi-Minaee, R., Alami, A., Moghaddam, A. & Zarei, A. Determination of concentration of metals in grapes grown in Gonabad vineyards and assessment of associated health risks. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 201(7), 3541–3552 (2023).

Rather, I. A., Koh, W. Y., Paek, W. K. & Lim, J. The Sources of Chemical Contaminants in Food and Their Health Implications. Frontiers in Pharmacology 8. (2017).

Sadighara, P. et al. Concentration of heavy metals in canned tuna fish and probabilistic health risk assessment in Iran. International J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 104, (2022).

Rana, M. M., Asdari, R., Chowdhury, A. J. K. & Munir, M. B. Heavy metal contamination during processing of canned fish: a review on food health and food safety. Desalination Water Treat. 315, 492–499 (2023).

Ni, L., Zhong, J., Chi, H., Lin, N. & Liu, Z. Recent advances in sources, migration, public health, and surveillance of bisphenol A and its structural analogs in canned foods. Foods 12(10), 1989 (2023).

Effiong, E. A. et al. Probabilistic non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risk assessments of potential toxic metals (PTMs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in canned foods in nigeria: Understanding the size of the problem. J. Trace Elem. Minerals. 4, 100069 (2023).

Massadeh, A. M., Al-Massaedh, A. A. T. & Kharibeh, S. Determination of selected elements in canned food sold in Jordan markets. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25(4), 3501–3509 (2018).

Ajayi, A. & Njoku, K. Concentration and human health risk assessment of alkylphenols, bisphenols and some heavy metals in selected canned foods in lagos, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 27(3), 531–541 (2023).

Ojezele, O., Okparaocha, F., Oyeleke, P. & Agboola, H. Quantification of some metals in commonly consumed canned foods in south-west nigeria: probable pointer to metal toxicity. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. 25(8), 1519–1525 (2021).

Sohrabi, H. et al. Metal–organic framework-based biosensing platforms for the sensitive determination of trace elements and heavy metals: a comprehensive review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62(11), 4611–4627 (2022).

Koch, W., Czop, M., Iłowiecka, K., Nawrocka, A. & Wiącek, D. Dietary Intake of Toxic Heavy Metals with Major Groups of Food Products-Results of Analytical Determinations. Nutrients 14, (8). (2022).

Clemens, S. & Ma, J. F. Toxic heavy metal and metalloid accumulation in crop plants and foods. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 67, 489–512 (2016).

Hadiani, M., Farhangi, R., Soleimani, H., Rastegar, H. & Cheraghali, M. Evaluation of heavy metals contamination in Iranian foodstuffs: canned tomato paste and tomato sauce (ketchup). Food Addit. Contaminants Part. B Surveillance. 7, 74–78 (2014).

Aboutaleb, E., Kazemi, Z., Kazemi, Z. & Azizi Khereshki, N. Analysis and evaluation of trace elements in Iranian Olive samples using ICP-OES. J. Adv. Environ. Health Res. 11(3), 168–173 (2023).

Jannat, B., Mirshamsi, S., Sadeghi, N., Oveisi, M. R. & Hajimahmoodi, M. Measuring the levels of zn, cu, Pb and cd via the polarography method in fermentative pickled cucumbers purchased from Tehran market 7, (2021).

Al Zabadi, H., Sayeh, G. & Jodeh, S. Environmental exposure assessment of cadmium, lead, copper and zinc in different Palestinian canned foods. Agric. Food Secur. 7, 1–7 (2018).

Geueke, B. et al. Systematic evidence on migrating and extractable food contact chemicals: most chemicals detected in food contact materials are not listed for use. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63(28), 9425–9435 (2023).

Saadatzadeh, A., Ghazi, A. A. M. S. & Sabahi, S. Measuring and comparing the concentration of heavy metals (arsenic, cobalt, cadmium, lead and mercury) in canned foods (strong acid, acid, low acid) in Ahvaz city. Iranian journal of food science and industry 21, (147). (2024).

Jannat, B., Mirshamsi, S., Sadeghi, N., Oveisi, M. R. & Hajimahmoodi, M. Measuring the levels of zn, cu, Pb and cd via the polarography method in fermentative pickled cucumbers purchased from Tehran market, Iran. J. Food Saf. Hygiene. 7(1), 52–59 (2021).

Akbudak, N. & Ekrem Üstün, G. The effect of irrigation of pickling cucumber with urban wastewater on product quality and heavy metal accumulation. Gesunde Pflanzen. 75(3), 593–601 (2023).

Raptopoulou, K. G., Pasias, I. N., Thomaidis, N. S. & Proestos, C. Study of the migration phenomena of specific metals in canned tomato paste before and after opening. Validation of a new quality indicator for opened cans. Food Chem. Toxicol. 69, 25–31 (2014).

Mohammadi, M. J. et al. Evaluation of carcinogenic risk of heavy metals due to consumption of rice in Southwestern Iran. Toxicol. Rep. 12, 578–583 (2024).

Neisi, A., Farhadi, M., Angali, K. A. & Sepahvand, A. Health risk assessment for consuming rice, bread, and vegetables in Hoveyzeh City. Toxicol. Rep. 12, 260–265 (2024).

Yenisoy-Karakaş, S. Estimation of uncertainties of the method to determine the concentrations of cd, cu, fe, pb, Sn and Zn in tomato paste samples analysed by high resolution ICP-MS. Food Chem. 132(3), 1555–1561 (2012).

Molin, M., Ulven, S. M., Meltzer, H. M. & Alexander, J. Arsenic in the human food chain, biotransformation and toxicology–Review focusing on seafood arsenic. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 31, 249–259 (2015).

Boadi, N., Mensah, J., Twumasi, S., Badu, M. & Osei, I. Levels of selected heavy metals in canned tomato paste sold in Ghana. Food Addit. Contaminants: Part. B. 5(1), 50–54 (2012).

Uroko, R., Okpashi, V., Etim, N. & Fidelia, A. Quantification of heavy metals in canned tomato paste sold in Ubani-Umuahia, Nigeria. J. Bio-Science. 28, 1–11 (2019).

Fowler, B. A., Alexander, J. & Oskarsson, A. Toxic metals in food. In Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, Elsevier: ; pp 123–140. (2015).

Alamri, M. S. et al. Food packaging’s materials: A food safety perspective. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 28(8), 4490–4499 (2021).

Ibrahim, I. D. et al. Need for sustainable packaging: an overview. Polymers 14, (20), 4430. (2022).

da Morte, B., dos Santos Barbosa, E. S., Santos, I., Nóbrega, E. C. & Korn, J. A. d. G. A., axial view inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry for monitoring Tin concentration in canned tomato sauce samples. Food Chem. 131(1), 348–352 (2012).

MUNTEANU, M., CHIRILĂ, E., STANCIU, G. & MARIN, N. Tin determination in canned foods. Ovidius Univ. Annals Chem. 21, 79–82 (2010).

Shariatifar, N. et al. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk assessment of lead in traditional and industrial canned black olives from Iran. Nutrire 47(2), 26 (2022).

Karatasli, M. Radionuclide and heavy metal content in the table Olive (Olea Europaea l.) from the mediterranean region of Turkey. Nuclear Technol. Radiation Prot. 33(4), 386–394 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.SG. and N.I. wrote the main manuscript text and A.A. and S.M prepared figures and tests. N.Y and P.S reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shavali -gilani, P., Abedini, A., Irshad, N. et al. Investigation of heavy metal levels in canned tomato paste, olives, and pickled. Sci Rep 15, 20923 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06896-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06896-9