Abstract

Anxiety, depression and psychological flexibility appear to be correlated with quality of life in cancer patients. However, the mediating role of psychological flexibility between emotional distress and quality of life are unclear. The aim of the study was to investigate the mediating role of psychological flexibility in the relationships between anxiety, depression, and quality of life in cancer patients undergoing treatment. A hundred and nineteen cancer patients participated in the study by completing the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the Action and Acceptance Questionnaire II, and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire, version 3. Anxiety and depression correlated with psychological flexibility and quality of life. Psychological flexibility correlated with the quality of life scales but not with the diarrhoea and constipation. Mediation analysis showed that depression and anxiety indirectly influenced cognitive and social function through psychological flexibility. Depression indirectly influenced emotional functioning, dyspnoea and insomnia. The results obtained suggest that psychological flexibility may affect the relationship between emotional distress and different aspects of quality of life for cancer patients.

Trial registration This research has been registered in www.ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier [NCT05126823] in 19/11/2021.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the progress made over the years in terms of prevention and treatment, cancer continues to be a major health problem worldwide. It is estimated that around 20 million new cases were diagnosed in 2022; a figure that is expected to rise to 32 million by 2045. The most common types of cancer worldwide are lung, breast, colorectal, prostate and stomach cancer1. In Spain, a similar pattern is observed with an estimated 296,103 cases to be diagnosed by 2025, with colorectal, breast, lung and prostate cancer being the most frequent. The figures are expected to reach 350,000 by 2050, data that are related to a greater population increase, as well as to the ageing of the population, exposure to risk factors (tobacco, alcohol, pollution, sedentary lifestyle, among others) and also to the increase in early detection, as in the case of breast, colorectal, cervical or prostate cancer2,3,4.

Symptoms of emotional distress are common among cancer patients. Recent studies report that up to 17% of patients in this group can be affected by symptoms of anxiety, 12% by depression, and around 8% by both anxiety and depression, although these data may vary according to the type of cancer and the time since diagnosis5,6. Furthermore, the data reveal consistent correlations between anxiety, depression and poorer quality of life, particularly among patients undergoing treatment. Previous research have observed significant correlations between anxiety and depression assessed with the HADS scale, and most of the functional and symptom scales measured with the EORTC QLQ C-307.

On the other hand, psychological flexibility (PF), a key concept in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)8, consistently correlates with lower symptoms of anxiety and depression, and increased quality of life in cancer patients9. As ACT focuses on promoting PF using six different processes (acceptance, cognitive diffusion, contact with the current moment, self-as-context, values, committed action), it is possible that the reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms, as well as improved quality of life may come as a consequence of coping focused on acceptance and connecting with personal values rather than suppression of negative thoughts and symptoms, which in the context of cancer may be an approach that is more tailored to patients’ needs10.

Considering the role that PF plays in this group of patients, it is necessary to establish the relationships and the possible effect of PF on quality of life. Previous research in this regard reports that PF plays a moderating role in the relationship between these variables, since it can be observed that when anxiety and depression decrease, psychologically more flexible participants show better quality of life scores and, furthermore, patients with higher psychological inflexibility show worse quality of life scores regardless of their levels of anxiety and depression11. Though these results might seem interesting, they originate from a study with limited sample size that does not include a complete quality of life evaluation which could help to better understand the role of PF between anxiety, depression and quality of life. In addition, a recently published systematic review emphasized the need to evaluate the mediating role of psychological flexibility in certain processes relevant to the field of psycho-oncology12,13.

Therefore, the hypotheses of this study were, first, that anxiety, depression and psychological flexibility will be related to different aspects of quality of life, including functional and symptoms scales, and, second, that psychological flexibility will play a mediating role in the relationship between emotional well-being (anxiety and depression) and quality of life in patients with cancer.

Methods

Participants

A total of 1394 patients were invited to participate in the study, but only 119 completed the informed consent as well as the assessment. Reasons for not participating were: incompatibility with inclusion criteria (n = 943), reluctance to participate (n = 214), other reasons (n = 120). The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were the following: Participants had to be men or women, aged between 18 and 70, with a confirmed stage I-III cancer diagnosis for breast, colorectal, gynaecologic, or lung cancer, be eligible for treatment, and not be a participant in another study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients younger than 18 years or older than 70 years, with stage IV cancer, other diagnosis than breast, colorectal, gynecological or lung cancer, not eligible for treatment or palliative care, and who were participating in another study.

Instruments

Action and acceptance questionnaire II (AAQ-II)

This instrument was designed to measure psychological flexibility through different items that evaluate how people apply psychological flexibility skills in their daily lives. It consists of 7 items that are scored from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true), with higher scores indicating greater psychological inflexibility. Examples of items of this instrument are: ‘My painful experiences and memories make it difficult for me to live a life I would value’ and ‘I am afraid of my feelings’. This instrument has good psychometric properties in its original version and its Spanish adaptation (α = 0.84–0.93)14,15.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

This scale was designed to evaluate the presence of anxiety and depression in patients with physical illnesses. It excludes somatic symptoms that might be misinterpreted as signs of emotional distress. It consists of two subscales of 7 items each, one for anxiety (HADSA) and one for depression (HADSD), which are scored from 0 to 3 on a range of 0–21. An example of an item from the anxiety subscale is ‘I feel tense or “wound up”’ and from the depression scale is “I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy”. Higher scores on each of the subscales indicate a greater presence of anxiety or depression. The instrument is widely used in cancer research, showing good psychometric properties in the original version as well as the Spanish adaptation (α = 0.86)16,17.

European organisation for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire, version 3. (EORTC QLQ C-30, v.3).

This instrument has been designed to assess quality of life in cancer patients using 30 items, such as ‘Do you have any trouble doing strenuous activities like carrying a heavy shopping bag or suitcase?’ or ’Were you limited in doing either your work or other daily activities?’ It includes five functional scales (Physical functioning/Role functioning/Emotional functioning/Cognitive functioning/Social functioning), three symptom scales (Fatigue/Nausea and vomiting/Pain), and six individual items (Dyspnoea/Insomnia/Appetite loss/Constipation/Diarrhoea/Financial difficulties) that are scored on a range of 1–4. Moreover, it includes a global health and general quality of life scale scored from 1 to 7. The raw scores of the different scales undergo linear transformation in order to standardize the scores to a range of 0-100. The interpretation of the scores depends on the scale. On the functional scale, higher scores mean better functioning, on the symptoms scale higher scores mean greater presence of symptomatology/problems, and on the global health and quality of life scale higher scores equate to better quality of life and global health. The instrument has good psychometric properties (α > 0.70–0.86)18,19.

Participants also completed a clinical and sociodemographic questionnaire that compiled information about their age, the time elapsed since diagnosis, gender, education, employment and marital status, cancer type and treatment, as well as the current state of their cancer.

Procedure

This is a secondary analysis of a study that set out to assess the efficacy of an ACT-based intervention in cancer patients undergoing treatment, and then to compare the results with those of two other groups: a waitlist group and another that also received the ACT intervention but had additional support provided via a mobile app. This research has been registered in a clinical trials repository with ref number: NCT05126823. Participants were recruited at Reina Sofía University Hospital in Córdoba (Spain). Researchers provided nursing staff in charge of recruitment with the study inclusion criteria during established treatment sessions. Once identified, patients were invited to participate in the study. Those who accepted completed the first evaluation as well as the informed consent form, guaranteeing confidentiality with regard to the data obtained, and informing participants of the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any moment without adverse consequences, and without the need to provide explanation of any kind. Prior to the start of the study activities, the approval of the corresponding ethical committee was obtained (ref. ref. 5090). This research was conducted in accordance with the criteria for human experimentation established by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were obtained from the clinical and sociodemographic data of the sample. A Pearson´s test was performed in order to test the correlations between psychological flexibility (AAQ-II), emotional wellbeing in terms of anxiety (HADSA), depression (HADSD) and quality of life scores (EORTC-QLQ C-30). PROCESS model 4 was used to test the mediation effect of psychological inflexibility between the HADS and EORTC-QLQ C-30 functional and symptom scales. Estimates of the indirect effects were based on 10.000 bootstraps iterations of computed simples at 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.28 for Windows20. The results are significant if p < .05.

Results

The sociodemographic and clinical information of the sample can be found in Table 1. Most of the participants were married women of an average age of 52, who had completed primary education and were on sick leave on account of ongoing treatment. The most common cancer type was stage III breast, while surgery, chemo and radiotherapy were the most frequent treatment, with an average of 18 months having passed since diagnosis.

Pearson´s correlation test showed that HADSA and HADSD significantly correlated with AAQ-II and with all the EORT-QLQ C-30 scales, except for the diarrhoea scale. In addition, AAQ-II significantly correlated with all the quality of life scales with the exception of the diarrhoea and constipation scales. The data are showed in Table 2.

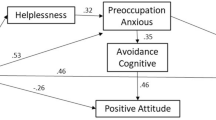

The results of the mediation analysis are shown in Table 3. Depression indirectly influenced the quality of life scores of cognitive function, emotional functioning, social functioning, dyspnoea and insomnia through psychological flexibility, while anxiety indirectly influenced cognitive function and social functioning using psychological flexibility as mediator.

Discussion

In cancer patients, psychological flexibility (PF) correlates with emotional wellbeing and quality of life9,10. However, the mediating role of PF affecting the relationships between anxiety, depression, and different aspects of quality of life has not been explored to date. The results obtained in our study are in line with previous research, observing that there were significant relationships between anxiety, depression, psychological flexibility and quality of life. Furthermore, the findings highlighted the mediating role of psychological flexibility between emotional well-being and most of the evaluated aspects of quality of life in these patients.

Previous research has shown that both anxiety and depression negatively influence the quality of life of cancer patients, something that the data from the present study also reflects7. When analysing the relationships between the different variables, the results show that anxiety and depression are inversely related to all the functional scales of the quality of life questionnaire, and most of the symptoms scales excluding diarrhoea, which indicates that, indeed, greater emotional distress correlates with a poorer quality of life in these patients. Possibly, this relationship is the result of significant emotional distress in patients caused by the cancer diagnosis and the effects of treatment, which negatively affect their quality of life. In addition, it is possible that the lack of relationship observed between psychological well-being and diarrhoea is due to the fact that most of the patients in the present study were women with breast cancer, since this symptom appears more frequently related to anxiety and depression in patients with other types of cancer, such as colorectal or lung cancer21,22,23.

Furthermore, there is a direct relationship between anxiety, depression and psychological flexibility. Considering that higher scores in the questionnaires indicate greater inflexibility, we can conclude that symptoms of emotional distress are related to greater psychological inflexibility in this group of patients. This is similar to results previously obtained in other studies, as psychological flexibility promotes acceptance of the present moment rather than avoiding or running away from negative events, which in cancer patients is more adaptive and promotes their emotional well-being9,10.

In addition, psychological flexibility correlates with most of the quality of life scales, excluding constipation and diarrhoea, and presents a similar pattern to anxiety and depression. Considering that both diarrhoea and constipation are physical symptoms that frequently appear as a consequence of anti-cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, it is possible that the lack of relationship observed in our study is due to the fact that these symptoms are more dependent on the individual’s physical reaction to the treatments than on their psychological flexibility24,25. Finally, in the functional scales higher levels of anxiety (cognitive and social) and depression (cognitive, emotional and social) lead to worse functionality, and this influence can be attributed to higher levels of psychological inflexibility. Furthermore, in the symptom scales (dyspnoea and insomnia), it is depression that results in a greater presence of this symptomatology through higher levels of psychological inflexibility. These data illustrate that psychological inflexibility ought to be understood as a key factor in the attempt to interpret the relationships between emotional distress and quality of life in patients. Overall, these results could be explained by the fact that psychological flexibility allows for greater resilience and healthier behaviours, as it promotes acceptance of the present situation and connection with personal values, which in turn improves the emotional state and quality of life of patients with cancer26,27. Being aware of this may be helpful in the design of interventions aimed at improving psychological flexibility13.

This study has certain limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results obtained. First, the results come from a cross-sectional evaluation, in which most of the participants were women with breast cancer, which may limit the extrapolation to other types of patients. In addition, the analyses of the different types of cancer, stages and treatments have been considered globally. For future research it would be interesting to establish subgroups of patients, and to develop profiles that confirm or refute the results obtained in the present study and it would be advisable for further studies to include patients with a wider variety of cancers in order to achieve greater generalisability of the results.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the results shown offer a novel perspective on the role of psychological flexibility in the relationship between anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients, which may be useful for the design of psychological interventions. Furthermore, clinicians should consider including screening for anxiety, depression and psychological flexibility as part of the routine psychological evaluation of cancer patients, with the aim of developing early interventions that can prevent the onset of emotional symptoms that impair patients’ quality of life.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory. (2024). https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en Accessed 13 Dec 2024.

International Agency for Research on Cancer.Global Cancer Observatory. (2024). https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en Accessed 13 Dec 2024.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory. (2024). https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/724-spain-fact-sheet.pdf Accessed 13 Dec 2024.

Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica. (2025). https://seom.org/images/LAS_CIFRAS_DMC2025.pdf Accessed 31 Mar 2025.

Alwhaibi, M., AlRuthia, Y. & Sales, I. The impact of depression and anxiety on adult cancer patients’ health-related quality of life. J. Clin. Med. 12(6), 2196. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062196 (2023).

Vitale, E. et al. Sex Differences in anxiety and depression conditions among cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers 16(11), 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16111969 (2024).

Papadopoulou, A. et al. Quality of life, distress, anxiety and depression of ambulatory cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Med. Pharm. Rep. 95(4), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.15386/mpr-2458 (2022).

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A. & Lillis, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006 (2006).

Salari, N. et al. The effect of acceptance and commitment therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with cancer: A systematic review. Curr. Psychol. 42(7), 5694–5716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01934-x (2023).

Proctor, C. J., Reiman, A. J. & Best, L. A. Cancer, now what? A cross-sectional study examining physical symptoms, subjective well-being, and psychological flexibility. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 11(1), 2266220. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2023.2266220 (2023).

Novakov, I. Emotional state, fatigue, functional status and quality of life in breast cancer: Exploring the moderating role of psychological inflexibility. Psychol. Health Med. 26(7), 877–886. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1842896 (2021).

Fawson, S. et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy processes and their association with distress in cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 18(3), 456–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2023.2261518 (2023).

Sauer, C., Haussmann, A. & Weissflog, G. The effects of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on psychological and physical outcomes among cancer patients and survivors: An umbrella review. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 33, 100810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2024.100810 (2024).

González-Fernández, S. & Fernández-Rodríguez, C. Acceptance and commitment therapy in cancer: Review of applications and findings. Behav. Med. 45(3), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2018.1452713 (2019).

Ruiz, F. J., Herrera, A. I., Luciano, C., Cangas, A. & Beltrán, I. Measuring experiential avoidance and psychological inflexibility: The Spanish version of the acceptance and action Questionnaire-II. Psicothema 25(1), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2011.239 (2013).

Terol-Cantero, M. C., Cabrera-Perona, V. & Martín-Aragón, M. Revisión de estudios de la Escala de Ansiedad y Depresión Hospitalaria (HAD) en muestras españolas. Ann. Psychol. 31(2), 494–503. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.2.172701 (2015).

Zigmond, A. & Snaith, R. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x (1983).

Aaronson, N. K. et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 85(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 (1993).

Calderon, C. et al. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). Qual. Life Res. 31(6), 1859–1869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-03068-w (2022).

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Versión 21.0. Armonk (IBM Corp, 2021).

Gray, N. et al. Predictors of anxiety and depression in people with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer 22(2), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1963-8 (2014).

Larsson, G., Von Essen, L. & Sjöden, P. Health-related quality of life in patients with endocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Acta Oncol. 38(4), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/028418699432022 (1999).

Wang, X. et al. Proportion and related factors of depression and anxiety for inpatients with lung cancer in china: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 30(6), 5539–5549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-06961-3 (2022).

Phung, T., Pitt, E., Alexander, K. & Bradford, N. Non-pharmacological interventions for chemotherapy-induced diarrhoea and constipation management: A scoping review. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 68, 102485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2023.102485 (2024).

Yilmaz, S. & Vural, G. Determining the relationship between perceived social support levels and chemotherapy symptoms in women with gynaecological cancer. Bezmialem Sci. 9(3), 326–333. https://doi.org/10.14235/bas.galenos.2020.3825 (2021).

Li, Z., Li, Y., Guo, L., Li, M. & Yang, K. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for mental illness in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 75(6), e13982. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13982 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on psychological flexibility, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and quality of life of patients with cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 20(6), 582–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12652 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the Consejería de Economía, Conocimiento, Empresas y Universidad of the Junta de Andalucía (Spain) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), grant number: P20_00485.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to study design and conceptualization. FGT conducted the data analysis. FGT MGC and FJ wrote the first draft of the study. The final draft was reviewed and approved by all the authors prior submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study received approval from the Andalusian Biomedical Research Ethics Portal (ref. 5090). All participants completed a written informed consent prior their participation in this study..

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Torres, F., García-Carmona, M., Gómez-Solís, Á. et al. Anxiety, depression, quality of life and the mediating role of psychological flexibility: A study on Spanish cancer patients. Sci Rep 15, 22530 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06942-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06942-6