Abstract

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis causes caseous lymphadenitis (CLA) in goats and sheep. This study assessed oral fluid (OF) as a minimally invasive sample for CLA serodiagnosis by detecting antibodies to phospholipase D (PLD), CP40 protein, and protein kinase G (PknG) using Western blot (WB). Serum and OF samples from 96 goats from a CLA-affected herd in Poland were tested using a commercial ELISA coated with recombinant PLD (rPLD-ELISA; serum only) and WB (serum and OF). Depending on the cut-off, the rPLD-ELISA had 70–80% diagnostic sensitivity. WB on serum showed very high diagnostic sensitivity (98%) and good agreement with the rPLD-ELISA. WB on OF was highly consistent with WB on serum, however it had slightly lower diagnostic sensitivity (90%). Moreover, WB on OF showed substantial variations in antigen detection, with antibodies to PLD being most effectively detected. Considerably fewer OF samples had anti-CP40 and PknG antibodies, likely due to antibody class variations or detection limitations. Further investigation into immunoglobulin classes in different sample types and optimized secondary antibodies is essential for developing an effective OF-based diagnostic test for CLA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (C. pseudotuberculosis) is a Gram-positive facultatively anaerobic coccobacillus. It causes several diseases, including caseous lymphadenitis (CLA) in sheep and goats, and ulcerative lymphangitis in horses and cattle1,2,3,4. C. pseudotuberculosis also affects camels5,6,7, alpacas8,9,10, and wild ruminants11,12,13,14. It has some zoonotic potential, although only a few cases in people have so far been reported15. CLA occurs worldwide and is economically significant in small ruminants10,16. The disease follows a chronic course with a long incubation period and presumably a lifelong carrier state following recovery, although this issue has not been ultimately settled. Several months after the infection, clinical signs, including mainly abscesses in the superficial lymph nodes, become apparent – it is called the external form of CLA. Some animals develop abscesses in the internal lymph nodes or internal organs, referred to as the internal form of CLA16,17,18,19. Over the last decades, CLA has become a widespread disease in goat herds in Poland20. Its herd-level seroprevalence was first determined in 1996, and it was shown to have increased from approximately 13% to over 60% in 200221. A recent investigation has shown that the herd-level seroprevalence reached approximately 70%20.

Isolation of C. pseudotuberculosis from abscesses and its identification using microbiological or molecular methods is the definitive confirmation of CLA diagnosis16,22,23. However, due to a long incubation period (2–6 months), unknown, but presumably long duration of the carrier state, and an existence of the internal form of the disease, serological tests play an important role, especially, in the evaluation of the status of herds as well as of individual animals before introduction into a herd19. Routine serological diagnostics is mainly based on immunoenzymatic assays (ELISA). However, western blot (WB) is considered the serological reference standard24. Several antigens of C. pseudotuberculosis with potential diagnostic applicability have been described25,26,27. Phospholipase D (PLD), an approximately 30 kDa protein, is the main exotoxin and the major virulence factor, favouring the infection process28. PLD is characterized by very high immunogenicity and antigenicity, making it a suitable component of vaccines29 and an antigen of serological tests30. A recombinant form of PLD (rPLD) has been used for developing commercial ELISAs (rPLD-ELISA), and they are commonly used for serological diagnostics of CLA31,32. Other antigens are a CP40, an approximately 40 kDa secreted endo-b-N-acetylglucosaminidase33,34 and a serine/threonine protein kinase G (PknG)35,36, an approximately 70 kDa protein homologous to an important virulence factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis30,37,38. In some preliminary studies based on in-house ELISAs, CP40 has shown high diagnostic specificity (dSp) of 97% but very low diagnostic sensitivity (dSe) of only 43%30, while PknG turned out to be both highly sensitive and specific (94% and 97%, respectively)39.

Oral fluid (OF) is a mixture of saliva and serum transudate that enters the mouth by crossing the buccal and gingival mucosa from the capillaries40,41. Therefore, OF contains antibodies from the systemic immune system (from the passage of serum antibodies) and locally produced antibodies from the secretory immune system in the salivary glands42,43,44. OF also contains feed particles, cell detritus, tracheal-nasal secretions, gastrointestinal reflux, and other particles from the environment currently being chewed by an animal. In ruminants, contrary to other species, the composition of OF is also vastly affected by rumination, which involves the regurgitation of material from the reticulo-rumen to the buccal cavity, where solid material is re-masticated and re-insalivated before being swallowed. Serological tests based on OF are becoming increasingly popular in non-ruminating animal species, especially pigs. Such tests are used for diagnosing classical swine fever45,46,47, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome48,49,50, porcine circovirus type 251 and Toxoplasma gondii infections52,53. Although theoretically, rumination can hinder diagnostic application of OF, it has so far been shown to be a suitable material for serological diagnostics of foot-and-mouth disease54 and Schmallenberg virus infection55 in ruminants. An in-house OF-based ELISA for Mycobacterium bovis infection in goats has also been developed56. OF offers several advantages over traditional diagnostic specimens, such as blood or tissue. The OF collection procedure is minimally invasive and welfare-friendly, with much less discomfort or stress for the animals than blood collection43. Moreover, it can be performed by non-veterinarian personnel with minimal training and, depending on the country regulations, might not require the consent of the Ethics Committee when carried out within the frame of scientific studies. Contrary to another type of non-invasive sample, milk, OF can also be collected from males and non-lactating females.

Our study aimed to evaluate the potential usefulness of OF as a material for serological identification of C. pseudotuberculosis-infected goats based on detecting antibodies to PLD, CP40, and PknG using WB. The dSe of rPLD-ELISA and WB performed using serum samples was also estimated.

Results

Diagnostic sensitivity of rPLD-ELISA

In the rPLD-ELISA, 67 serum samples (69.8%) were positive, 10 (10.4%) – inconclusive, and 19 (19.8%) – negative. Sample-to-positive control ratio (S/P%) of the aforementioned samples ranged from 50.1 to 157.5% (median of 88.9%), from 40.1 to 49.0% (median of 46.0%), and from 0.6 to 39.9% (median of 34.2%), respectively. The dSe of rPLD-ELISA was 69.8% (CI 95%: 60.0%, 78.1%) if only serum samples with S/P% >50% were considered positive and 80.2% (CI 95%: 71.1%, 87.0%) if all serum samples with S/P% >40% were considered positive.

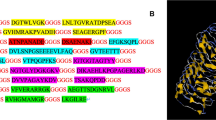

Antigenic structure of the reference strain

The sodium dodecyl sulphate – polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed to show the distribution of antigens in the C. pseudotuberculosis strain isolated from the investigated herd. Multiple bands were visible in the gel, with the most prominent bands located at heights corresponding to approximately 30 kDa (two bands), 35 kDa (one band), 40 kDa (one band), 70 kDa (multiple bands) (Fig. 1). An original gel is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2. Based on previous findings30,57, the locations of the bands corresponded to: LexA protein (28 kDa), PLD (30 kDa or 31.4 kDa) TrxR (35 kDa), CP40 (40 kDa), and PknG (70 kDa). The band corresponding to CP40 was the most visible.

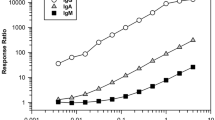

Comparison of diagnostic sensitivity of WB on serum and OF samples

Antibodies to any of the three antigens were detected in a significantly higher (by 8.3%; CI 95%: 2.3%, 15.8%; P = 0.003) proportion of serum (94 / 96 goats; 97.9%; CI 95%: 92.7%, 99.4%) than OF samples (86 / 96 goats; 89.6%; CI 95%: 81.9%, 94.2%).

Antibodies to PLD were present in a similar proportion of serum (89 / 96 goats; 92.7%) and OF samples (84 / 96 goats; 87.5%; P = 0.302). Antibodies to CP40 were detected in a significantly higher proportion of serum (82 / 96 goats; 85.4%) than OF samples (10 / 96 goats; 10.4%; P < 0.001). Also, antibodies to PknG were detected in a significantly higher proportion of serum (73 / 96 goats; 76.0%) than OF samples (31 / 96 goats; 32.3%; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2; Table S1).

Diagnostic sensitivity (i.e. proportion of 96 goats that tested positive) of the western blot performed using serum and oral fluid (OF) samples depending on the antigen of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. P-values indicate statistical significance of comparisons between serum and OF samples (McNemar’s test). Letters (a, b,c) indicate statistical significance of comparisons between antigens separately for serum (red letters) and OF samples (blue letters) – proportions denoted by the different letters differed significantly in the Cochrane Q test followed by McNemar’s test with Bonferroni correction.

In the serum samples, antibodies to PLD were detected significantly more often than antibodies to PknG (PBC = 0.004). In contrast, the differences between the proportion of samples with antibodies to PLD and CP40 or between the proportion of samples with antibodies to CP40 and PknG were not significant (PBC = 0.438 and PBC = 0.372, respectively). In the OF samples, antibodies to PLD were detected significantly more often than antibodies to PknG (PBC < 0.001) or CP40 (PBC < 0.001), and antibodies to PknG were detected significantly more often than antibodies to CP40 (PBC < 0.001) (Fig. 2, Table S2).

Most serum samples were positive for antibodies to all three antigens (63.5%), followed by sera positive for antibodies to PLD and CP40 (16.7%). Only 2 / 94 seropositive goats (2.1%) did not have antibodies to PLD (instead, they had antibodies to CP40) (Table S2). Over a half of the OF samples were only positive for antibodies to PLD (56.3%), followed by sera positive for antibodies to PLD and PknG (20.8%), and sera positive for antibodies to all three antigens (9.4%). Only 2 / 86 goats with positive results of OF (2.3%) did not have antibodies to PLD (instead, they had antibodies to PknG) (Table S2).

Combination of PLD with any of the two other antigens did not significantly increase the dSe of WB either in serum (Fig. 3a) or OF (Fig. 3b). Combination of CP40 and PknG (without PLD) performed significantly worse than any other antigen combination in OF (P < 0.001) but not in serum. The difference between dSe of a combination of PLD and CP40 compared to dSe of PLD alone (98% vs. 93%, respectively) was closest to statistical significance but still insignificant (P = 0.074).

The agreement between WB performed using serum, and WB performed using OF was high (AC1 = 86.6%; CI 95%: 79.2%, 94.1%; Po = 88.5%). The high agreement resulted only from similar results with respect to antibodies to PLD (AC1 = 81.0%; CI 95%: 72.1%, 89.8%; Po = 84.4%) since the agreement between serum and OF concerning PknG was poor (AC1 = -3.5%; CI 95%: -23.3%, 16.4%; Po = 47.9%), and it was even significantly negative in terms of CP40 (AC1 = -53.9%; CI 95%: -70.7%, -37.1%; Po = 22.9%) (Table S3).

Serum and OF samples negative in WB

In terms of samples classified as negative, distribution of samples without any band and with weak bands was generally balanced, except for PLD in serum samples where samples with weak bands significantly predominated (P = 0.047) and CP40 in OF samples where samples without any band significantly predominated (P = 0.001) (Fig. S1).

Agreement between rPLD-ELISA and WB on serum samples

The agreement between rPLD-ELISA and WB was good: AC1 = 61.4% (CI 95%: 49.1%, 73.8%; Po = 71.9%) if only serum samples with S/P% >50% in rPLD-ELISA were considered positive and AC1 = 75.4% (CI 95%: 65.5%, 85.3%; Po = 80.2%) if all serum samples with S/P% >40% in rPLD-ELISA were considered positive. Interestingly, of the two serum samples negative in WB, one was inconclusive in rPLD-ELISA (S/P% = 47.1%). The other was negative, but its S/P% was still relatively high (S/P% = 36.0%).

Discussion

Our study shows for the first time that the OF of goats contains antibodies to C. pseudotuberculosis and can serve as a material for serological diagnostics of CLA in this species. Antibodies to PLD appear to be the only ones of potential clinical usefulness. Surprisingly, antibodies to CP40 and PknG are detectable in OF of a low proportion of CLA-affected goats.

The main difficulty encountered when investigating the accuracy of diagnostic tests for CLA is the determination of the true health status of an animal. This problem results from an ambiguous definition of an animal diseased with CLA. If a CLA-diseased animal is defined as the one with abscess(es) confirmed bacteriologically to be of C. pseudotuberculosis origin, serological tests turn out to be perfectly sensitive but rather unspecific, like in the studies of Ellis et al. and Costa et al.32,58. Abscesses usually develop after several months of infection, which is long enough for an animal to mount a humoral immune response, detectable in serological tests17,19. However, in many animals infected with C. pseudotuberculosis, apparent abscesses develop much later, or even never, which leads to positive results of serology in many, by definition, “healthy” animals. In terms of the evaluation of diagnostic accuracy of serological tests, classifying only animals with abscesses as CLA-diseased animals does not seem reasonable because bacteriology, not serology, is the diagnostic test of choice in such animals. Another approach to determining true health status is to define a CLA-diseased animal as one with antibodies to C. pseudotuberculosis. In this situation, the most acknowledged serological test is chosen as a gold standard – it is usually WB as it detects antibodies to the broadest array of pathogen’s antigens. Animals positive in this test are considered CLA-diseased. This approach has been commonly applied to evaluate the accuracy of serological tests for CLA24,30,59. Obviously, no serological gold standard can overcome the problem of delayed seroconversion. Furthermore, the assumption is that the persistence of antibodies parallels the lifelong infection. This is highly likely to be true as C. pseudotuberculosis can remain viable inside phagocytes and establish long-lasting intracellular infection19. However, we do not know any study directly evidencing the lifelong nature of C. pseudotuberculosis infection. In our study, we assumed that all adult goats born, raised, or kept in the herd affected by a clinical form of CLA for several years must have been exposed to C. pseudotuberculosis and likely mounted an immune response. It is a strict and conservative approach, and it could have led to underestimating the dSe of rPLD-ELISA, especially when we take note of the fact that our estimate of dSe of rPLD-ELISA is relatively low (70-80%) compared to many previous studies24,27,30. However, if we consider WB performed with serum as the gold standard, an increase in the estimated dSe of rPLD-ELISA is negligible (from to 69.8–71.3% when only serum samples with S/P% >50% are considered positive and from 80.2 to 80.9% when all serum samples with S/P% >40% are considered positive). Therefore, we suspect that there may be some variability in the diagnostic performance of rPLD-ELISA caused by unknown animal- or pathogen-related factors. Our study does not allow drawing any conclusions regarding dSp, as only diseased animals have been enrolled.

Virtually 90% of OF samples contained antibodies to PLD, approximately 30% to PknG, and only 10% to CP40. It means that 8 times more serum than OF samples contained antibodies to CP40, and two times more serum than OF samples contained antibodies to PknG. This can be explained by the fact that serum antibody levels are significantly higher for many pathogens in various mammalian species than in OF. Thus, the concentration of antibodies corresponds to their detectability in the sample44,60,61,62.

CP40 has a high antigenic potential, stimulating the production of specific antibodies detectable in the serum of goats and sheep30. Also, in our study, 85% of goats had antibodies to CP40 in serum but only 10% in OF. Further, 28 goats had a weak band in WB, indicating that some low antibody concentrations could be present in OF. The existence of some physical or physiological barrier for antibodies to CP40 and PknG between systemic circulation and OF is one of the explanations, yet it is highly unlikely. More probable is that antibodies to PLD are not only of the IgG class but also of the IgA class and are produced locally at higher concentrations, while antibodies to CP40 and PknG are mostly of systemic origin and reach OF in low amounts. If correct, WB shows true differences in antibody concentrations between serum and OF. However, another explanation may be that it is just a technical shortcoming of our WB protocol. Maybe antibodies to PLD are mainly of the IgG class and systemic origin, and they are efficiently detected by rabbit anti-goat IgG secondary antibodies, which we used in our study. At the same time, antibodies to CP40 and PknG are mostly local IgA secretory antibodies. In this situation, using anti-goat IgA secondary antibodies together with anti-goat IgG secondary antibodies could have increased the detectability of anti-CP40 and anti-PknG antibodies. Both scenarios are feasible, as, according to the datasheet, the rabbit anti-goat IgG (H/L) antibody recognizes the heavy and light chains of goat IgG but may react with the light chains of other goat immunoglobulins. Determination of the class of antibodies in OF could clarify this problem and this aspect warrants further investigation.

Showing that specific antibodies are detectable in WB is the first step on the long pathway to developing an ELISA for CLA with OF as diagnostic material. An indirect ELISA based on the whole-bacterium antigen used in our study was developed over 20 years ago by Kaba et al. and has performed very well on goat sera ever since24. Results of our study indicates that using more targeted antigen, e.g., rPLD, may be worth considering as antibodies to PLD are most abundant or at least most effectively detected in OF. Developing an efficient serological diagnostic test based on non-invasively collected material would be of value. Stress-reducing procedures become increasingly popular in modern veterinary medicine and animal disease control programs based on such procedures have been shown to play a useful role63. The method of OF collection employed in our study differs from those described previously. For pigs, a rope hung in the pen is recommended because pigs are eager to interact with the rope and chew it. In ruminants, more active OF collection using cotton swabs54,56 or commercial plastic shafts55 (Copan Flocked Swabs) has been performed. We used a sponge held in metal forceps. This was an extremely inexpensive and efficient method, as by squeezing the sponge in a syringe, we obtained between 1 and 3 ml of OF without centrifugation. This amount was enough to perform several rounds of testing.

Last but not least, we encountered some problems identifying PknG owing to inconsistent information regarding its molecular mass, which can be found in the literature. According to Barral et al.30, PknG weighs 69 kDa. The corresponding electrophoresis band lay somewhere between 55 and 70 kDa (Fig. 1 in Barral et al.30). On the other hand, in the studies of Santana-Jorge et al.36 and Silva et al.64 PknG was claimed to weigh 83 kDa. In comparison, the band on the electrophoresis gel presented in Fig. 1 of Silva et al.64 was located slightly above 70 kDa. We decided to stick to the molecular mass indicated on the pictures of electrophoresis gels and mentioned by Barral et al.30.

Concluding, OF appears to be a promising material for non-invasive and non-stressing serological testing of goats for CLA. However, classes of anti-C. pseudotuberculosis immunoglobulins predominating in OF should be determined first, to allow for the most optimal selection of secondary antibodies to be used in the OF-targeted serological assay.

Materials and methods

Animals and sample collection

The study enrolled all 96 adult (> 1-year-old) Saanen dairy goats, 92 females and 4 males, from the dairy herd affected by CLA. The owner of the goats used in this study provided informed consent for all procedures described in the manuscript. The owner confirmed understanding and agreement with the experimental protocols and authorized the use of data collected from the animals for research and publication purposes. The herd was located in north-eastern Poland. All goats in the herd had been under regular observation (clinical examination at least every month, bacteriological testing of every mature abscess) since August 2022, and serum and OF samples were collected in November 2022. At the moment of the study, the goats were kept in two spacious and high concrete-wooden barns and were irregularly grazed on a small backyard pasture during the summer months. In 2018, CLA was first diagnosed in a male goat with a superficial abscess. The diagnosis was based on isolation of C. pseudotuberculosis from the abscess. In the following years, the disease gradually spread over the entire herd. It was repeatedly re-confirmed by positive results of bacteriological culture of swabs collected from abscesses of the superficial lymph nodes. The herd was also tested for caprine arthritis-encephalitis (CAE) using an indirect ELISA (ID Screen MVV-CAEV Indirect Screening test, IDvet Innovative Diagnostics, Grabels, France) twice in 2018 and 2022, and all goats tested negative. Between August and November 2022, 26 / 96 goats enrolled in the study (27.1%) had had at least one abscess confirmed by bacteriological culture to be caused by C. pseudotuberculosis. Given that all goats enrolled in this study had been either born and raised in this herd or kept in the herd for at least 3 years (since the purchase of the herd by the current owner in 2019), we classified all of them as exposed to C. pseudotuberculosis and potentially affected by CLA (either clinically or subclinically). Therefore, the proportion of goats whose serum or OF samples tested positive in a given test (rPLD-ELISA with serum, WB with serum, or WB with OF) was considered an estimate of dSe of this particular test.

Samples of blood and OF were collected from each goat at the same time. The blood was collected from the jugular vein into 10-ml dry tubes (BD Vacutainer, BP-Plymouth, UK) and transported to the laboratory. After 24 h storage in the refrigerator (4–8 °C), blood was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, serum was harvested into 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and stored at -20 °C until testing using rPLD-ELISA and WB. The OF was collected with a 5 × 1 × 1 cm fragment of polypropylene sponge held in stainless steel forceps. It was inserted into the oral cavity and kept there for approximately 30 s., so an animal could thoroughly chew it up. Then, the sponge was placed in a 20-ml clogged syringe to prevent fluid leakage, and in such a form, the material was transported to the laboratory. There, OF was squeezed out of sponges into 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. OF samples were stored at -20 °C until testing with WB. OF samples were not centrifuged. Forceps were washed in the mild detergent (soap) between animals.

We confirmed that all experiments in this study were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations. All the procedures of the study followed the ARRIVE guidelines. Blood collection was performed as part of routine herd diagnostics for infectious diseases and was approved by the Local Ethics Committee in Warsaw (Approval No. WAW2/048/2021). OF was collected non-invasively, and this procedure did not require the Ethics Committee approval according to Polish legal regulations (the Act on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes of 15 January 2015).

Commercial rPLD-ELISA

Serum samples were tested using a commercial indirect ELISA based on rPLD (ID Screen CLA, IDvet Innovative Diagnostics, Grabels, France) according to the manufacturer’s manual. Briefly, serum samples were diluted 1:20 in the dilution buffer, and reading was performed at 450 nm using the Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek, USA). The samples’ optical density (OD) was corrected by the OD of the manufacturer’s positive and negative control serum. The sample-to-positive control ratio (S/P%) was interpreted as follows: S/P% ≤40% – negative result, S/P% >40–50% – inconclusive result, and S/P% > 50% – positive result.

Western blot

The positive control serum was obtained from an adult female goat from this herd several months before the study. The goat had multiple abscesses in the superficial lymph nodes, from which C. pseudotuberculosis was isolated in a bacteriological culture. The goat was also positive in the commercial rPLD-ELISA. The negative control serum and OF were obtained from an apparently healthy adult goat from another herd with no history of CLA and a negative rPLD-ELISA result.

The whole-bacterium antigen for WB was prepared from the C. pseudotuberculosis isolate obtained from an abscess of a goat from the same herd according to the method described by Kaba et al.24 with minor modifications. Briefly, the C. pseudotuberculosis isolate was cultivated on Columbia blood agar (Graso Biotech, Poland) for 24 h at 37 °C in the aerobic atmosphere, then 5 ml of Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth (Graso Biotech, Poland) was inoculated with a few colonies, and incubated in the same conditions with agitation. This culture was transferred into a 50 ml BHI broth, and incubation was continued under the same conditions for 24 h. Next, 2 L of BHI broth were inoculated with the 50 ml culture and incubated in the same conditions for 16 h. Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation (7000 rpm, 10 min) and then washed three times in PBS (phosphate buffered saline; 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 9 mM Na2HPO4 × 12H2O, 2.5 mM KCl, pH 7.2) with 0.2% Tween-80 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The cell pellet was resuspended in 12 ml of the antigen preparation buffer (0.5 M Tris pH 6.8; 5.2% SDS; 8.7% 2-mercaptoethanol), boiled (100 °C) for 10 min, and then centrifuged (at 10,000 rpm for 15 min). The collected supernatant represented the ELISA solid phase antigen and was stored in 500 ml aliquots at − 80 °C.

The antigen was electrophoresed by the sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to standard procedures. Briefly, antigens were heated at 98 °C for 5 min in sample buffer containing 0.0625 M Tris (pH 6.8), 2.0% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulphate, 25.0% Glycerol, 5.0% (vol/vol) b-mercaptoethanol, and 0.00125% bromophenol blue. Antigens were separated on polyacrylamide gels (stacking gel: 4%, running gel: 8%). The protein standard Precision Plus Protein Standards Dual Color (Bio Rad Laboratories, USA) was used. Electrophoresis was performed under a voltage of 60 V for the stacking gel and 120 V for the running gel. Before analysis, SDS gels were stained with Coomassie blue (2.5% brilliant blue in 50% methanol, 10% acetic acid). Subsequently, the electrophoresed antigen was transferred from the gel to the supported nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, USA) in the TransBlot Turbo Transfer system (Bio-Rad, USA). Membranes were washed in TBST (a mixture of tris-buffered saline and Polysorbate 20) for 10 min. and incubated in the Everyblot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad, USA) for 20 min. Then, the membranes were washed 3 times for 10 min. An estimation of the suitable dilutions of the tested samples was performed. Finally, serum samples were diluted 1:100 in the blocking buffer. OF samples were centrifuged at 2600 rpm for 5 min. To separate the liquid from the solid particles and then diluted 1:5 in the blocking buffer. One-hour serum and OF samples incubation on membranes was performed in the Mini Protean Multi II (Bio-Rad, USA). Then, the membranes were washed 3 times for 10 min. in TBST. In the following 1-hour incubation process, secondary antibodies (Rabbit anti-goat IgG H/L conjugated to alkaline phosphatase, Bio-Rad, USA) were used at a dilution of 1:4500 for membranes incubated with sera and 1:4000 for membranes incubated with OF. After the incubation, membranes were washed twice for 5 min. in TBST, once for 5 min. in TBS, and twice for 5 min. in alkaline phosphatase color development buffer (Bio-Rad, USA). The results were visualized using the Alkaline Phosphatase Conjugate Substrate Kit (Bio-Rad, USA). The Precision Plus Protein™ Standards Dual Color (Bio-Rad, USA) ladder was used to estimate protein sizes.

The results of WB were visually reviewed by a single investigator (KB) and classified as (i) no band present, (ii) weak band present, and (iii) strong band present, separately at the level of each of 3 antigens: PLD – approximately 30 kDa, CP40 – approximately 40 kDa, PknG – approximately 70 kDa. When a band at the level of a relevant antigen was absent or weak, the result was classified as negative; only a strong band was considered a positive result. The serum or OF sample was considered positive in WB if a strong band at the level of at least one of the aforementioned antigens was present.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were presented as counts (n) and proportions (%). Proportions of positive results were compared between tests (rPLD-ELISA vs. WB), biological materials (serum vs. OF), or antigens (PLD vs. CP40 vs. PknG) using the McNemar’s test (in the case of 2 compared groups) or the Cochrane Q test (in the case of > 2 compared groups). If the Cochrane Q test was significant, post-hoc analyses were performed using the McNemar’s test with Bonferroni correction (denoted as PBC). The 95% confidence intervals (CI 95%) for proportions were calculated using the Wilson score method65 and for the difference between proportions using the Newcombe’s method57. Proportions of negative results without bands and with weak bands were compared using the log-likelihood ratio goodness-of-fit test66. The chance-corrected agreement of results of rPLD-ELISA and WB and of WB between serum and OF was assessed using the Gwet’s AC1 coefficient of agreement67. The chance-corrected agreement was categorized as follows: AC1 = 0.81-1.0 – very good agreement, 0.61–0.80 – good (substantial), 0.41–0.60 – moderate, 0.21–0.40 – fair, ≤ 0.20 – poor agreement68. The observed agreement (Po) was also presented. All significance tests were two-sided, and a significance level (α) was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted in TIBCO Statistica 13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yeruham, I., Elad, D., Van-Ham, M., Shpigel, N. Y. & Perl, S. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection in Israeli cattle: clinical and epidemiological studies. Vet. Rec. 140, 423–427. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.140.16.423 (1997).

Connor, K. M., Fontaine, M. C., Rudge, K., Baird, G. J. & Donachie, W. Molecular genotyping of multinational ovine and caprine Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis isolates using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Vet. Res. 38, 613–623. https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2007013 (2007).

Boysen, C., Davis, E. G., Beard, L. A., Lubbers, B. V. & Raghavan, R. K. Bayesian Geostatistical analysis and ecoclimatic determinants of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection among horses. PLoS One. 10, e0140666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140666 (2015).

Mathewos, M. & Fesseha, H. Cytopathological and bacteriological studies on caseous lymphadenitis in cattle slaughtered at Bishoftu municipal abattoir, Ethiopia. Vet. Med. Sci. 8, 1211–1218. https://doi.org/10.1002/vms3.744 (2022).

Radwan, A. I., El-Magawry, S., Hawari, A., Al-Bekairi, S. I. & Rebleza, R. M. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection in camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Saudi Arabia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 21, 229–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02261094 (1989).

Tejedor, M. T., Martin, J. L., Corbera, J. A., Shulz, U. & Gutierrez, C. Pseudotuberculosis in dromedary camels in the Canary Islands. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 36, 459–462. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:TROP.0000035012.63821.12 (2004).

Terab, A. M. A. et al. Pathology, bacteriology, and molecular studies on caseous lymphadenitis in Camelus dromedarius in the emirate of Abu dhabi, UAE, 2015–2020. PLoS One. 16, e0252893. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252893 (2021).

Anderson, D. E., Rings, D. M. & Kowalski, J. Infection with Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis in five alpacas. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 225, 1743–1747. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.2004.225.1743 (2004).

Sprake, P. & Gold, J. R. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis liver abscess in a mature alpaca (Lama pacos). Can. Vet. J. 53, 387–390 (2012).

Sting, R. et al. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infections in alpacas (Vicugna pacos). Animals 12, 1612 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12131612

Stauber, E., Armstrong, P., Chamberlain, K. & Gorgen, B. Caseous lymphadenitis in a white-tailed deer. J. Wildl. Dis. 9, 56–57. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-9.1.56 (1973).

Morales, N. et al. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection in Patagonian Huemul (Hippocamelus bisulcus). J. Wildl. Dis. 53, 621. https://doi.org/10.7589/2016-09-213 (2017).

Varela-Castro, L. et al. Endemic caseous lymphadenitis in a wild Caprinae population. Vet. Rec. 180, 405. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.103925 (2017).

Di Donato, A. et al. First report of caseous lymphadenitis by Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and pulmonary verminosis in a roe deer (Capreolus capreolus linnaeus, 1758) in Italy. Animals 14, 566. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14040566 (2024).

Bastos, L. B. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis: immunological responses in animal models and zoonotic potential. J. Clin. Cell. Immunol. S4, 005. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9899.S4-005 (2012).

Smith, M. C. & Sherman, D. M. Goat Medicine 3rd edn (Wiley Blackwell, 2023).

Ashfaq, M. K. & Campbell, S. G. Experimentally induced caseous lymphadenitis in goats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 41, 1789–1792 (1980).

Williamson, L. H. Caseous lymphadenitis in small ruminants. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 17, 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30033-5 (2001).

Baird, G. J. & Fontaine, M. C. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and its role in ovine caseous lymphadenitis. J. Comp. Pathol. 137, 179–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2007.07.002 (2007).

Kaba, J. et al. Herd-level true Seroprevalence of caseous lymphadenitis and paratuberculosis in the goat population of Poland. Prev. Vet. Med. 230, 106278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2024.106278 (2024).

Kaba, J. et al. Evaluation of the risk factors influencing the spread of caseous lymphadenitis in goat herds. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 14 https://doi.org/10.2478/v10181-011-0035-6 (2011).

Dorella, F. A., Pacheco, L. G. C., Oliveira, S. C., Miyoshi, A. & Azevedo, V. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis: microbiology, biochemical properties, pathogenesis and molecular virulence studies. Vet. Res. 37, 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2005056 (2006).

Almeida, S. et al. Quadruplex PCR assay for identification of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis differentiating biovar Ovis and equi. BMC Vet. Res. 13, 290. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1210-5 (2017).

Kaba, J. Development of an ELISA for the diagnosis of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infections in goats. Vet. Microbiol. 78, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1135(00)00284-4 (2001).

Dorella, F. A. et al. Antigens of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and prospects for vaccine development. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 8, 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1586/14760584.8.2.205 (2009).

Galvão, C. E. et al. Identification of new Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis antigens by immunoscreening of gene expression library. BMC Microbiol. 17, 202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-1110-7 (2017).

Silva, M. T. D. O. et al. The combination of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis Recombinant proteins rPLD, rCP01850, and rCP09720 for improved detection of caseous lymphadenitis in sheep by ELISA. J. Med. Microbiol. 68, 1759–1765. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.001096 (2019).

Pépin, M., Boisramé, A. & Marly, J. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis: biochemical properties, production of toxin and virulence of ovine and caprine strains. Ann. Rech Vet. 20, 111–115 (1989).

De Pinho, B. R. et al. A novel approach for an immunogen against Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection: an Escherichia coli bacterin expressing phospholipase D. Microb. Pathog. 151, 104746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104746 (2021).

Barral, T. D. et al. A panel of Recombinant proteins for the serodiagnosis of caseous lymphadenitis in goats and sheep. Microb. Biotechnol. 12, 1313–1323. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.13454 (2019).

Sting, R. et al. Clinical and serological investigations on caseous lymphadenitis in goat breeding herds in Baden-Wuerttemberg. Berl Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 130, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.2376/0005-9366-16024 (2017).

Costa, L. et al. Utility assessment of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of subclinical cases of caseous lymphadenitis in small ruminant flocks. Vet. Med. Sci. 6, 796–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/vms3.297 (2020).

Silva, J. W. et al. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis cp09 mutant and cp40 Recombinant protein partially protect mice against caseous lymphadenitis. BMC Vet. Res. 10, 965. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-014-0304-6 (2014).

Shadnezhad, A., Naegeli, A. & Collin, M. CP40 from Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis is an endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase. BMC Microbiol. 16, 261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0884-3 (2016).

Trost, E. et al. The complete genome sequence of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis FRC41 isolated from a 12-year-old Girl with necrotizing lymphadenitis reveals insights into gene-regulatory networks contributing to virulence. BMC Genom. 11, 728. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-728 (2010).

Santana-Jorge, K. T. O. et al. Putative virulence factors of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis FRC41: vaccine potential and protein expression. Microb. Cell. Fact. 15, 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-016-0479-6 (2016).

Walburger, A. et al. Protein kinase G from pathogenic Mycobacteria promotes survival within macrophages. Science 304, 1800–1804. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1099384 (2004).

Warner, D. F. & Mizrahi, V. The survival kit of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 13, 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0307-282 (2007).

Farias, A. P. F. D. et al. rSodC is a potential antigen to diagnose Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis by enzyme-linked immunoassay. AMB Expr. 10, 186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-020-01125-0 (2020).

Atkinson, J. et al. Guidelines for saliva nomenclature and collection. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 694, XI–XII (1993).

Chiappin, S., Antonelli, G., Gatti, R. & De Palo, E. F. Saliva specimen: A new laboratory tool for diagnostic and basic investigation. Clin. Chim. Acta. 383, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2007.04.011 (2007).

Mestecky, J. Saliva as a manifestation of the common mucosal immune system. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 694, 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18352.x (1993).

Henao-Diaz, A., Giménez-Lirola, L. & Baum, D. H. Guidelines for oral fluid-based surveillance of viral pathogens in swine. Porc Health Manag. 6, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40813-020-00168-w (2020).

Page, L. J., Lagunas-Acosta, J., Castellana, E. T. & Messmer, B. T. Accurate prediction of serum antibody levels from noninvasive saliva/nasal samples. Biotechniques 74, 131–136. https://doi.org/10.2144/btn-2022-0106 (2023).

Mur, L. et al. Potential use of oral fluid samples for serological diagnosis of African swine fever. Vet. Microbiol. 165, 135–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.034 (2013).

Giménez-Lirola, L. G. et al. Detection of African swine fever virus antibodies in serum and oral fluid specimens using a Recombinant protein 30 (p30) dual matrix indirect ELISA. PLoS One. 11, e0161230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0161230 (2016).

Panyasing, Y., Thanawongnuwech, R., Ji, J., Giménez-Lirola, L. & Zimmerman, J. Detection of classical swine fever virus (CSFV) E2 and Erns antibody (IgG, IgA) in oral fluid specimens from inoculated (ALD strain) or vaccinated (LOM strain) pigs. Vet. Microbiol. 224, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.08.024 (2018).

Kittawornrat, A. et al. Kinetics of the Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) humoral immune response in swine serum and oral fluids collected from individual boars. BMC Vet. Res. 9, 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-9-61 (2013).

Rotolo, M. L. et al. Detection of Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV)-specific IgM-IgA in oral fluid samples reveals PRRSV infection in the presence of maternal antibody. Vet. Microbiol. 214, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.11.011 (2018).

Henao-Diaz, A., Giménez-Lirola, L., Magtoto, R., Ji, J. & Zimmerman, J. Evaluation of three commercial Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) oral fluid antibody ELISAs using samples of known status. Res. Vet. Sci. 125, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2019.05.019 (2019).

Prickett, J. R. et al. Prolonged detection of PCV2 and anti-PCV2 antibody in oral fluids following experimental inoculation: prolonged detection of PCV2 infection by oral fluid. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 58, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1865-1682.2010.01189.x (2011).

Campero, L. M. et al. Detection of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in oral fluid from pigs. Int. J. Parasitol. 50, 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2019.11.002 (2020).

Kauter, J. et al. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii-specific antibodies in pigs using an oral fluid-based commercial ELISA: advantages and limitations. Int. J. Parasitol. 53, 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2022.11.003 (2023).

Archetti, I. L., Amadori, M., Donn, A., Salt, J. & Lodetti, E. Detection of foot-and-mouth disease virus-infected cattle by assessment of antibody response in oropharyngeal fluids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33, 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.33.1.79-84.1995 (1995).

Lazutka, J., Spakova, A., Sereika, V., Lelesius, R. & Sasnauskas, K. Petraityte-Burneikiene, R. Saliva as an alternative specimen for detection of Schmallenberg virus-specific antibodies in bovines. BMC Vet. Res. 11, 237. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-015-0552-0 (2015).

Ortega, J. et al. Evaluation of P22 ELISA for the detection of Mycobacterium bovis-specific antibody in the oral fluid of goats. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 674636. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.674636 (2021).

Hodgson, A. L., Bird, P. & Nisbet, I. T. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression in Escherichia coli of the phospholipase D gene from Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 172, 1256–1261. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.172.3.1256-1261.1990 (1990).

Ellis, J. A., Hawk, D. A., Holler, L. D., Mills, K. W. & Pratt, D. L. Differential antibody responses to Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis in sheep with naturally acquired caseous lymphadenitis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 196, 1609–1613 (1990).

ter Laak, E. A., Bosch, J., Bijl, G. C. & Schreuder, B. E. Double-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Immunoblot analysis used for control of caseous lymphadenitis in goats and sheep. Am. J. Vet. Res. 53, 1125–1132 (1992).

Hunt, A. J. et al. The testing of saliva samples for HIV-1 antibodies: reliability in a non-clinic setting. Sex. Transm Infect. 69, 29–30. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.69.1.29 (1993).

Langenhorst, R. et al. Development of a fluorescent microsphere immunoassay for detection of antibodies against Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus using oral fluid samples as an alternative to serum-based assays. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 19, 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1128/CVI.05372-11 (2011).

Nokes, D. J. et al. Has oral fluid the potential to replace serum for the evaluation of population immunity levels? A study of measles, Rubella and hepatitis B in rural Ethiopia. Bull. World Health Organ. 79, 588–595 (2001).

Nagel-Alne, G. E., Valle, P. S., Krontveit, R. & Sølverød, L. S. Caprine arthritis encephalitis and caseous lymphadenitis in goats: use of bulk tank milk ELISAs for herd‐level surveillance. Vet. Rec. 176, 173–173. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.102605 (2015).

Silva, M. T. D. O. et al. NanH and PknG putative virulence factors as a Recombinant subunit immunogen against Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis infection in mice. Vaccine 38, 8099–8106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.010 (2020).

Altman, D. G., Machin, D., Bryant, T. N. & Gardner, M. J. Statistics with Confidence 2nd edn (BMJ Books, 2000).

Zar, J. H. Biostatistical Analysis 5th edn (Pearson Prentice Hall, 2010).

Gwet, K. L. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 61, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711006X126600 (2008).

Altman, D. G. Practical statistics for medical research (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. (1990). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429258589

Funding

The publication was (co)financed by Science development fund of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft; MMi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation; ZN: investigation; AMFik: Methodology, Investigation; MR: Methodology, Investigation; Resources; Writing – review & editing; EK: Methodology, Investigation; MMu: Methodology, Investigation; TN: Investigation; OSJ: Investigation; LW: Investigation; IMD: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing; EB: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing; MC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization; Supervision, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft; JK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethic statement

This study did not involve experimental procedures on animals. Blood collection was performed as part of routine herd diagnostics for infectious diseases and was approved by the Local Ethics Committee in Warsaw (Approval No. WAW2/048/2021). OF was collected non-invasively, and this procedure did not require the Ethics Committee approval according to Polish legal regulations (the Act on the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific or Educational Purposes of 15 January 2015).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biernacka, K., Mickiewicz, M., Nowek, Z. et al. Oral fluid as a material for serological diagnostics of caseous lymphadenitis in goats. Sci Rep 15, 23293 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06957-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06957-z