Abstract

The global rise in mental disorders presents a significant public health challenge, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of their underlying risk factors. Existing studies on obesity and brain health primarily rely on metrics such as body mass index and waist-to-hip ratio, which inadequately capture central obesity, a fat distribution strongly associated with increased health risks. This underscores the need for more precise metrics, with the body roundness index (BRI) emerging as a promising option. 321,596 UK Biobank participants were analyzed in this study. Cox regression models assessed associations between BRI and incident mental disorders, while logistic and multiple linear regression models explored relationships with psychiatric symptoms and white matter integrity, respectively. Results indicated that higher BRI was significantly associated with increased risks of incident overall mental disorders (HR [95% CI] = 1.12 [1.09, 1.15]), as well as specific high-prevalence disorders including substance use disorder (1.05 [1.01, 1.11]), depressive disorder (1.34 [1.24, 1.45]), and anxiety disorder (1.09 [1.03, 1.15]). An overall positive association was also observed between elevated BRI and adverse psychiatric symptoms and reduced white matter integrity. These findings highlighted BRI as a potential indicator of mental health. BRI’s association with clinical and subclinical psychiatric outcomes emphasized its relevance in understanding the interplay between central adiposity and brain health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global rise in mental disorders represents a critical public health challenge1. Growing evidence suggests that lipid dysregulation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of mental disorders, due to its involvement in neurotransmission, synaptic plasticity, and neuroinflammation2. However, monitoring and modulating the brain’s lipid environment is difficult, owing to the blood-brain barrier and the complexity of neural lipid dynamics3,4. These challenges underscore the need for alternative approaches to understanding lipid-related risks to mental health. Obesity, a systemic metabolic condition, provides a feasible proxy for examining lipid dysregulation and its influence on brain function5. Among its various forms, central obesity, characterized by visceral fat accumulation, has garnered attention for its pronounced role in releasing pro-inflammatory mediators that cross the blood-brain barrier and contribute to neuroinflammation6,7. As a modifiable and easily measurable risk factor, central obesity offers unique opportunities to explore metabolic influences on mental health and provides a practical target for interventions aimed at reducing systemic and neuroinflammatory pathways implicated in mental disorders8.

To comprehensively assess the impact of central obesity on brain metabolism and mental health, the body roundness index (BRI) has emerged as a promising metric9. Traditional measures, such as body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), are commonly used to evaluate obesity-related mental health risks10. However, these indices have notable limitations, BMI does not distinguish between fat and lean mass, and WHR only partially addresses fat distribution by focusing on waist circumference alone11. By combining waist circumference with height, BRI offers a precise estimate of visceral adiposity. While existing evidence does not consistently demonstrate BRI’s superiority over these traditional indices across all cardiometabolic conditions, it has shown enhanced predictive value in specific contexts, including metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease12,13,14,15. These applications highlight BRI’s potential to capture physiologically consequential aspects of adipose distribution beyond mere body size metrics. Given its capacity to quantify central fat with greater anatomical and functional specificity, BRI may also serve as a valuable somatic biomarker for assessing vulnerability to mental disorders across populations. However, empirical evidence linking BRI to mental health remains scarce, with existing studies yielding inconsistent findings constrained by small sample sizes or cross-sectional designs16,17,18. These limitations highlight the need for large-scale, longitudinal research to clarify the role of BRI in mental health and to establish its utility in assessing risks associated with mental disorders.

Leveraging data from the UK Biobank, our study aimed to advance understanding of the associations between the BRI and a spectrum of mental health outcomes, encompassing both overall mental disorders and specific diagnoses including substance use disorder, depressive disorder, and anxiety disorder. Additionally, we explored associations with related psychiatric symptoms and alterations in white matter (WM) integrity. This multi-dimensional approach allowed us to assess the mental health implications of central adiposity across diagnostic, symptomatic, and structural domains. By adopting a prospective longitudinal design and leveraging a physiologically relevant index of adiposity, our study contributes novel evidence the understandings of the metabolic determinants of mental health.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

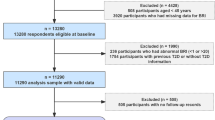

A total of 321,596 participants were included in the final analytical sample for primary outcomes in this prospective cohort study (Fig. 1). Participants were excluded in a stepwise manner: those with a diagnosis of mental disorders at baseline, those with missing or invalid exposure data, and those with missing key covariates used in subgroup analyses. Subsequent subsamples were derived for secondary analyses, including psychiatric symptoms and brain MRI analyses. A full overview of the selection process is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Baseline characteristics of the participants included in the primary analysis (N = 321,596) are presented in Table 1. Among the participants, 57.5% were under the age of 60, 51.1% were female, 50.0% had a high index of multiple deprivation (IMD), 36.5% had a low education level, and 55.9% had a high-income level. In total, 179,985 (56.0%) reported never smoking, 210,328 (65.4%) reported no heavy alcohol intake, 176,632 (54.9%) engaged in regular physical activities, 180,179 (56.0%) had healthy sleep patterns, and 124,756 (38.8%) adhered to a healthy diet. Supplementary Table 1 provides data on mental disorders occurrences disaggregated by sex, shown as total person-years and incidence rates.

Study workflow. This study analyzed data from 321,596 UK Biobank participants, tracking outcomes for mental disorders, including depressive disorder, substance use disorder, and anxiety disorder, with psychiatric symptoms and alterations in brain white matter as secondary outcomes. (A) The study cohort, including population flowchart and baseline characteristics. (B) Body roundness index. (C) Cox proportional hazards regression models were applied to examine associations between BRI levels and mental disorders risk. Hazard ratios (HRs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated in our analyses. Subgroup analyses were conducted stratified by age (< 60/≥60), sex (male/female), region (urban/other), and prevalent diseases (yes/no). Further analyses were also utilized to estimate the relationships of BRI levels with psychiatric symptoms and impairments of brain white matter by logistic regression models and multiple linear regression models, respectively.

Associations of BRI with overall and specific mental disorders

After adjusting for age, sex, IMD, education, income, healthy lifestyle factors, prevalent diseases, blood pressure, metabolic biomarkers, and medication use, we assessed the associations between BRI levels and incident mental disorders by Cox proportional hazards models with false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P values (Table 2). Compared to the low BRI group, participants demonstrated elevated risks of overall mental disorders with hazard ratio (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of 1.05 (1.03, 1.08) and 1.12 (1.09, 1.15) in the moderate and high BRI group, respectively. In specific conditions, the moderate BRI group showed increased risks of depressive disorder (1.13 [1.04, 1.22]) and anxiety disorder (1.09 [1.03, 1.15]), while the high BRI group exhibited higher risks of substance use disorder (1.05 [1.01, 1.11]), depressive disorder (1.34 [1.24, 1.45]), and anxiety disorder (1.18 [1.11, 1.26]). In the age-stratified analysis, individuals younger than 60 years had a higher risk of experiencing overall mental disorders (1.23 [1.20, 1.26] for participants < 60, 1.08 [1.05, 1.11] for participants ≥ 60, P for interaction < 0.001), substance use disorder (1.13 [1.07,1.20], 0.95 [0.88, 1.02], P for interaction < 0.001), depressive disorder (1.60 [1.49, 1.73], 1.20 [1.09, 1.31], P for interaction < 0.001), and anxiety disorder (1.34 [1.24, 1.45], 1.02 [0.94, 1.11], P for interaction < 0.001). In the gender-stratified analysis, males were at a lower risk for substance use disorder (0.97 [0.91, 1.04] for males, 1.14 [1.07, 1.22] for females, P for interaction = 0.001). Results demonstrated no significant difference in stratification analyses by region- and disease- subgroups (Table 3).

Associations of BRI with psychiatric symptoms

Using the same adjustment strategy, we further examined the associations between BRI levels and 19 psychiatric symptoms by logistic regression models with FDR-corrected P values, finding significant associations overall, with 11 of 19 symptoms remaining significantly related to BRI levels (Fig. 2). Specifically, high BRI showed significant associations with unhappiness with own health (OR [95% CI] = 1.87 [1.75, 1.99]), recent changes in speed of moving or speaking (1.37 [1.25, 1.51]), recent feelings of inadequacy (1.10 [1.04, 1.16]), recent feelings of tiredness or low energy (1.35 [1.30, 1.41]), recent feelings of depression (1.15 [1.09, 1.21]), recent trouble concentrating on things (1.23 [1.17, 1.30]), recent poor appetite or overeating (2.45 [2.32, 2.59]), recent lack of interest or pleasure in doing things (1.28 [1.21, 1.35]), recent easy annoyance or irritability (1.17 [1.11, 1.23]), recent feelings of foreboding (1.09 [1.03, 1.16]), and recent feelings or nervousness or anxiety (0.92 [0.88, 0.96]) (Supplementary Table 2). In the sex-stratified subgroup analyses, the associations between BRI levels and the psychiatric symptoms were generally stronger in females compared to males (general unhappy: 0.79 [0.69, 0.91] for males, 1.29 [1.14, 1.45] for females, P for interaction < 0.001; unhappiness with own health: 1.61 [1.46, 1.79] for males, 2.00 [1.85, 2.16] for females, P for interaction = 0.001; recent feelings of inadequacy: 1.00 [0.91, 1.09] for males, 1.17 [1.09, 1.25] for females, P for interaction = 0.003; recent feelings of depression: 1.00 [0.92, 1.09] for males, 1.23 [1.16, 1.32] for females, P for interaction < 0.001, recent lack of interest or pleasure in doing things: 1.13 [1.04, 1.23] for males, 1.35 [1.26, 1.44] for females, P for interaction = 0.001) (Supplementary Table 3).

Associations between BRI levels and the psychiatric symptoms. The relationships of low, moderate and high-BRI group (the low-BRI group serving as the reference) with the 19 symptoms were estimated with available information, utilizing logistic regression models. The 19 symptoms were grouped into three primary categories: subjective well-being including 3 symptoms, 9 depressive symptoms, and 7 anxiety symptoms. Data were presented as the odds ratios (ORs). Significance was determined through the FDR-corrected P value (PFDR <0.05). An asterisk indicates a statistically significant association.

Associations of BRI with brain white matter integrity

We further examined the associations between BRI and WM integrity after adjusting for psychiatric symptom burden, operationalized by the total scores of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). The descriptive statistics for brain phenotypes are demonstrated in Supplementary Table 4. The results of multiple linear regression analyses of DTI metrics, including mean diffusivity (MD) and isotropic volume fraction (ISOVF), with FDR-corrected P values are presented in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 5. Generally, positive associations were identified for MD in tract middle cerebellar peduncle (β [95% CI] = 0.187 [0.153, 0.222]), tract anterior thalamic radiation (0.119 [0.087, 0.151]), tract cingulate gyrus part of cingulum (0.096 [0.063, 0.131]), and others, suggesting potential tissue degradation or an increase in extracellular space. In addition, a significant positive association for ISOVF was also found with estimated βs of 0.242 [0.207, 0.277] for tract middle cerebellar peduncle, 0.215 [0.180, 0.250] for tract anterior thalamic radiation, 0.123 [0.088, 0.250] for tract cingulate gyrus part of cingulum, 0.101 [0.067, 0.136] for tract superior thalamic radiation, and others, indicating an increase in isotropic diffusion, which may reflect alterations in extracellular fluid distribution and potential disruption of WM structure. In the sex-stratified subgroup analyses, the associations between BRI and alterations in WM integrity were generally stronger in males compared to females (MD of tract anterior thalamic radiation: 0.190 [0.146, 0.234] for males, 0.039 [-0.009, 0.086] for females, P for interaction = 0.012; tract posterior thalamic radiation: 0.129 [0.083, 0.175] for males, -0.043 [-0.091, 0.007] for females, P for interaction < 0.001; tract superior thalamic radiation: 0.138 [0.092, 0.185] for males, 0.033 [-0.015, 0.082] for females, P for interaction = 0.038, and others. ISOVF of tract anterior thalamic radiation: 0.255 [0.207, 0.302] for males, 0.144 [0.095, 0.193] for females, P for interaction = 0.018; tract superior longitudinal fasciculus: 0.142 [0.094, 0.190] for males, 0.065 [0.016, 0.115] for females, P for interaction = 0.020; tract posterior thalamic radiation: 0.100 [0.053, 0.147] for males, -0.081 [-0.130, -0.031] for females, P for interaction < 0.001, and others) (Supplementary Table 6).

Associations between BRI levels and brain white matter integrity. The relationships between BRI levels and the integrity of white matter tracts were evaluated using multiple linear regression models among 27,361 participants with available MRI data from the UK Biobank. The mean diffusivity (MD), and isotropic volume fraction (ISOVF) of white matter tracts were utilized as reference metrics. Results are presented as β values, with significance determined by FDR-corrected P values. Furthermore, the results of stratified analyses by sex are presented on the right. Regions marked in red denote positive correlations. The brain structure marked with an asterisk indicates a statistically significant association.

Mediation analyses of white matter tracts on the associations between BRI and psychiatric symptoms

analyses to explore whether alterations in WM microstructure, as measured by MD values and ISOVF values, mediate the associations between BRI and psychiatric symptoms. Based on prior analyses, we selected 11 psychiatric symptom outcomes that showed significant associations with BRI. The analyses revealed that several WM tracts demonstrated significant mediating effects (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). In particular, the tract forceps minor and tract anterior thalamic radiation emerged as relatively consistent mediators across a broad range of symptom domains. Other notable tracts such as tract superior longitudinal fasciculus, tract middle cerebellar peduncle, tract cingulate gyrus part of cingulum, tract posterior thalamic radiation, and tract superior thalamic radiation, mediating specific symptoms such as trouble falling asleep, feelings of inadequacy, and depression. The results of the sensitivity analyses indicated that the main findings were robust (Supplementary Table 9).

Discussion

This study with a large population from the UK Biobank, examined the relationship between BRI levels and mental disorders, as well as related psychiatric symptoms and alterations in WM microstructures. Results indicated that elevated BRI was associated with increased risks of incident mental disorders. Additionally, higher BRI levels were associated with adverse psychological symptoms, accompanied by elevated MD and ISOVF values across several WM tracts. These results provide crucial epidemiological evidence linking BRI to mental health, and is, to our knowledge, the first large-scale prospective cohort study to integrate psychiatric diagnoses, symptomatology, and neuroimaging phenotypes in this context. By employing BRI as a physiologically informed index of central adiposity, our work extends existing research beyond traditional obesity metrics and offers novel insights into the somatic underpinnings of mental vulnerability. These findings may inform the development of more targeted preventive strategies for metabolic-psychiatric comorbidity.

Obesity is a chronic, multifaceted condition associated with a wide range of health complications. Among its forms, abdominal obesity has been identified as a particularly relevant factor, demonstrating stronger associations with many health outcomes19,20. WHR is a commonly used metric for assessing abdominal obesity, with previous studies suggesting it may serve as a more accurate predictor than BMI, as it can better account for fat distribution21,22. However, without considering height, the precision of WHR as an obesity measure can vary across individuals of different statures23. To address these limitations, BRI, which incorporates both height and waist circumference, has been proposed as a more robust alternative. Previous studies have demonstrated BRI’s superiority over BMI and WHR in predicting cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and other health conditions15,24,25. However, research exploring the association between BRI and brain health remains scarce, with existing findings showing inconsistency. Some studies report a weak or absent link between BRI and depressive or anxiety symptoms, raising concerns about the generalizability of BRI as a universal predictor of mental health risk across diverse populations26,27. In contrast, research based on NHANES database, has identified a positive association between elevated BRI and the prevalence of mental disorders, suggesting that the strength of this relationship may vary by demographic group or healthcare setting17. These findings suggest that contextual factors may modulate the BRI-mental health relationship, indicating a potential link and underscoring the need for further studies to confirm this association and explore underlying mechanisms.

Our study identified a significant association between mental disorders and BRI levels. These findings also underscore the importance of exploring underlying mechanisms given the associations we observed with alterations in WM integrity and related psychiatric symptoms. One plausible mechanism involves the role of central obesity in promoting visceral fat accumulation, which has been associated with increased fat deposition in the brain28,29. Visceral fat, being metabolically active, releases adipokines that drive the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)30,31. Elevated ROS levels, combined with weakened antioxidant defenses, may activate pro-inflammatory pathways, damage essential cellular components and induce apoptosis32. These processes are likely to impact WM function, as indicated by increases in MD and ISOVF, which suggest the potential presence of brain edema and reflect compromised cellular integrity and disrupted microstructural organization33. Such edema could intensify neuroinflammatory processes, further impairing brain network connectivity and resilience, which may, in turn, heighten vulnerability to mental disorders34. Additionally, central obesity and mental disorders share risk factors, such as disruptions in gut microbiota composition. The gut microbiota communicates with the brain through the gut-brain axis, influencing metabolic and neurological functions. Considering the limitations of current research, future experimental studies are essential to elucidate these mechanistic pathways in greater depth.

Our study included several subgroup analyses. In the age-stratified analysis, individuals under 60 showed a significantly higher risk of mental disorders, likely due to age-related neuroendocrine dynamics, such as increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis sensitivity, which may exacerbate the effects of central adiposity, highlighting the need for early interventions35. The gender-stratified analysis revealed a stronger association between BRI and mental disorders in females, likely driven by biological factors including hormonal, inflammatory, and psychosocial factors, including weight stigma and stressors unique to women36,37. These findings emphasize the potential for precision medicine in mental health, with targeted approaches based on age, gender, and comorbidities enhancing prevention and treatment. Notably, the urban-rural stratification showed no significant differences, suggesting that BRI is a robust indicator of mental health risks across populations, though urban challenges like air pollution and social stressors merit further exploration38.

Beyond the diagnosis of mental disorders, our study reveals that higher BRI levels are significantly associated with a wide range of psychiatric symptoms, particularly those reflecting affective and somatic dimensions such as tiredness, poor appetite or overeating, anhedonia, and motor retardation. These findings suggest that central adiposity may contribute to subclinical psychological distress even before overt psychopathology manifests. The pattern of symptom associations aligns with existing evidence linking visceral adiposity to inflammatory responses, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysregulation, and reward system alterations—mechanisms that may underpin motivational deficits, cognitive fatigue, and emotional dysregulation39,40,41,42. Notably, while higher BRI was generally associated with increased odds of depressive symptoms, certain anxiety- or worry-related symptoms exhibited inverse associations. This pattern may reflect the engagement of distinct neurobiological pathways by central adiposity in shaping different psychiatric dimensions43. One plausible explanation lies in the divergent pathophysiological mechanisms underlying depressive and anxiety symptoms. Although both conditions have been linked to systemic inflammation and dysregulation of the HPA axis, emerging evidence suggests that central obesity may preferentially activate neuroimmune circuits associated with anhedonia and psychomotor retardation—hallmark features of depression44,45,46. In contrast, its influence on hyperarousal and anticipatory anxiety appears more complex and potentially moderated by behavioral or psychosocial buffers47,48. For instance, individuals with higher BRI may exhibit reduced engagement in stress-inducing social contexts due to lifestyle adaptations or social withdrawal, which could paradoxically mitigate certain anxiety-related manifestations49. Additionally, residual confounding from unmeasured factors, such as personality traits, or differential symptom perception, may contribute to these divergent patterns, highlighting the importance of symptom-specific approaches in future psychiatric epidemiological research50.

Our mediation results provide preliminary support for a structural pathway linking central adiposity to psychiatric symptoms. Notably, the forceps minor and anterior thalamic radiation generally mediated the associations between BRI and a range of symptoms, implicating interhemispheric connectivity and thalamo-prefrontal circuits in central adiposity–related neuropsychiatric vulnerability51,52. Additional tracts, including the superior longitudinal fasciculus and cingulum, also emerged as mediators for more specific symptom domains such as insomnia, feelings of inadequacy, and depressive affect, highlighting the symptom-specific neural correlates of adiposity. These findings reinforce the hypothesis that excess visceral fat may influence mental health not only through metabolic or hormonal pathways, but also via structural brain alterations affecting circuits central to emotion, cognition, and motivation53,54.

Our study had some limitations. First, we cannot establish a causal relationship between BRI and mental disorders, and further evidence is required to validate our findings. Second, mental disorder diagnoses were based on electronic health records, which could lead to underreporting or delayed diagnoses. Third, partial volume effects may have influenced our findings, potentially compromising tissue characterization and estimates of WM microstructure, despite the use of specific imaging techniques designed to mitigate such issues. Fourth, although we accounted for some confounders, the possibility of residual or unmeasured confounding effects cannot be ruled out entirely. Lastly, the UK Biobank cohort comprises predominantly individuals of European descent, which limits the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups. Further studies are required to confirm these results in diverse populations.

In conclusion, our study found significant associations between higher BRI and increased risks of mental disorders. Elevated BRI was also genarally linked to adverse psychiatric symptoms and compromised WM integrity. Subgroup analyses suggested that demographic factors may influence these associations. This study provides robust epidemiological evidence of BRI’s relevance in mental health, highlighting its potential as a simple, accessible tool for early detection of obesity-related mental health risks. By identifying central adiposity as a key risk factor, BRI offers a valuable tool for preventive and therapeutic strategies, enabling more personalized interventions and improving mental health outcomes at individual and population levels.

Methods

Study population

The UK Biobank is a large-scale, ongoing cohort study that initially enrolled approximately 500,000 individuals aged 37 to 73 between 2006 and 2010. Recruitment occurred across 22 assessment centers throughout England, Scotland, and Wales, selected to represent a wide range of socioeconomic and health backgrounds. The data were collected through touchscreen questionnaires, physical assessments, biological samples, and other evaluations, creating a comprehensive health database. Participants have been monitored for disease outcomes via national health records. Ethical approval for the UK Biobank was granted by the North West Multi-Center Research Ethics Committee, with informed consent obtained from all participants (UK Biobank application number: 99001 [2023-01-31 to 2026-01-31]). Participants lacking data of exposure, outcome, or specific covariates, and presenting with mental disorders at baseline were excluded, yielding a final sample of 321,596 individuals, including 27,361 with data on brain MRI. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.

Exposure assessment

In this study, BRI was employed as a metric to evaluate body composition. In the UK Biobank, waist circumference (Data Field 48) and standing height (Data Field 50) were recorded at baseline during physical assessments. The formula for BRI is as follows:

BRI scores generally range from 1 to 16, with higher values indicating greater adiposity16. For this analysis, we focused on the range of 1 to 10, as more than 95% of participants in the UK Biobank fall within this interval, making it a representative spectrum of body fat distribution in the general population. To facilitate meaningful comparisons, participants were classified into three BRI exposure groups: low, moderate, and high, with the low-BRI group serving as the reference. This tripartite grouping, though arbitrary due to the absence of established BRI cutoffs, allows a nuanced examination of BRI’s association with health outcomes, especially within a representative and widely applicable range for general body composition.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of this study were defined as a broad spectrum of mental health disorders, identified through hospital inpatient records and self-reported diagnoses in the UK Biobank. Hospital records were linked to national health registers and coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions (ICD-9 and ICD-10). We examined both composite and specific mental health outcomes, encompassing overall mental disorders (ICD-10: F00-F99) as well as several high-prevalence subtypes. Specifically, we assessed substance use disorder (ICD-10: F10-F19), depressive disorder (identified via self-reported diagnoses [UK Biobank field 20002: codes 1286, 1291, 1531] and hospital records [ICD-9: 311, 290.6, 296.2; ICD-10: F32, F33]), and anxiety disorder (self-reported diagnoses [field 20002: code 11287] and hospital records [ICD-9: 300.0, 296.0, 296.2; ICD-10: F40, F41]). A list of case ascertainment criteria is provided in Supplementary Table 10. Participants were followed from the date of their baseline assessment to the earliest of the following endpoints: diagnosis of any mental disorders, death, the last available date in either primary care data or hospital inpatient data, or December 19, 2022, whichever occurred first.

The secondary outcomes of this study focused on the presence of 19 psychiatric symptoms and alterations in WM. Psychiatric symptoms were assessed using the UK Biobank’s online mental health self-assessment questionnaire. The symptoms with broad sample representation was chosen and grouped into three categories. Subjective well-being was evaluated by asking participants how happy, healthy, and satisfied they felt in life overall. Responses of “Extremely unhappy” or “Not at all” for any of these questions indicated unhappiness. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the PHQ-9, and anxiety symptoms were evaluated with the GAD-7 scale. Both PHQ-9 and GAD-7 used a 4-point Likert scale, where responses ranged from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”), with any score of 1 or above signifying the presence of a symptom. Detailed information for the definition of psychiatric symptoms can be found in Supplementary Table S9.

WM imaging data were derived from the UK Biobank, utilizing diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) acquired on Siemens Skyra 3T MRI scanners equipped with 32-channel head coils across dedicated imaging centers55. The standardized imaging protocol, implemented since 2014, ensures high consistency and reproducibility across participants. The diffusion MRI protocol employed a monopolar Stejskal-Tanner spin-echo echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) = 3600 ms, echo time (TE) = 92 ms, voxel size = 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm³, and multiband acceleration factor = 3. Diffusion weighting was applied using two shells with b-values of 1000 and 2000 s/mm², each comprising 50 unique diffusion-encoding directions, along with 5 b = 0 images and 3 additional b = 0 images with reversed phase-encoding polarity to facilitate distortion correction55,56. These DWI data were preprocessed using the UK Biobank’s standardized pipeline, which integrates tools from the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) and other established neuroimaging packages. The pipeline included corrections for head motion and eddy current-induced distortions using FSL’s eddy, susceptibility-induced distortion correction via topup, and brain extraction using the Brain Extraction Tool (BET)57. Following preprocessing, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metrics, MD were derived using DTIFIT. Additionally, metrics from neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI), including ISOVF, were computed to characterize microstructural complexity beyond that captured by conventional DTI metrics. WM integrity was assessed using these imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs), extracted from 15 anatomically defined WM tracts. We selected MD and ISOVF as markers due to their complementary roles in characterizing WM microstructure. MD represents the overall diffusivity, with elevated values suggestive of tissue degradation or increased extracellular space. ISOVF quantifies the proportion of isotropic diffusion, where higher values indicate extracellular fluid expansion, often associated with disrupted WM architecture58. Together, these metrics provide a multidimensional framework for evaluating WM integrity in relation to mental health outcomes. All continuous brain structure measures were normalized to facilitate cross-individual comparison. Details of IDPs are presented in Supplementary Table 10.

Covariates

To mitigate the influence of confounding variables on mental disorders and BRI level, various covariates were integrated into the statistical models. These covariates encompassed age, sex, IMD, educational level, income level, healthy lifestyles (never smoking, no heavy alcohol intake, healthy sleep patterns, healthy diet, and regular physical activity), prevalent diseases (hypertension and diabetes), blood pressure (systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure), metabolic biomarkers (glucose, hemoglobin A1c, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, total cholesterol, and triglycerides), and medication use (opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory or antirheumatic drugs [NSAID]). The IMD was utilized to assess social deprivation at the neighborhood level, encompassing seven distinct domains, which include health, education, income, employment, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment59. Educational level was categorized into “high” and “low” groups for analysis. Participants with qualifications such as College or University degree, National Vocational Qualification (NVQ), or professional certifications were classified as the “high” group. Those with lower qualifications, including Advanced Levels (A levels), General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSEs), Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE), or no formal qualifications, were classified as the “low” group. Participants’ income level was divided into high and low groups based on the median value (cut-off: £ 3100). Never smoking was defined as a binary classification: individuals categorized as “Yes” had no history of smoking at baseline, while those categorized as “No” included both current and former smokers. No heavy alcohol intake was defined as the average daily intake ≤ 16 g of pure alcohol (2 units of alcohol) for both men and women. Regular physical activity was assessed according to the American Heart Association’s guidelines, which recommend engaging in a minimum of 150 min of moderate-intensity exercise or 75 min of vigorous-intensity exercise (or an equivalent combination) per week60. A healthy diet was characterized by the consumption of at least four out of seven food groups that are commonly recommended as dietary priorities for cardiometabolic health. Healthy sleep patterns was characterized by meeting at least four out of five criteria for healthy sleep behaviors, which included: an early chronotype; sleeping 7 to 8 h per day; experiencing insomnia rarely or never; not self-reporting snoring; and dozing off during the day rarely or never. A detailed list of included medications is provided in Supplementary Table 13.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the study participants were summarized as medians (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables and counts (percentages) for categorical variables. After assuring that the proportional hazard assumption was met through the Scaled Schoenfeld Residual, Cox proportional hazard regression models were utilized to assess the associations between BRI level and the incidence risks of mental disorders. Missing values were deleted from the analyses.

s were adopted in our study, Model 1 served as the unadjusted baseline. Model 2 adjusted for core demographic and socioeconomic factors, including age, sex, IMD, education level, and income level. Model 3 further adjusted for healthy lifestyle factors, prevalent diseases, blood pressure measures, metabolic biomarkers and medication use. HRs and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated. To further identify the potential modifiers of the associations above, a series of stratified analyses were performed by age (< 60/≥60), sex (female/male), region (urban/other), hypertension (yes/no), and diabetes (yes/no). A test of the interaction between BRI levels and each term was conducted in the model.

Additionally, the associations between BRI levels and 19 psychiatric symptoms were assessed using logistic regression models with the same adjustment strategy, with results expressed as (ORs and 95% CIs. For neuroimaging analyses, multiple linear regression models were utilized to examine the associations between BRI levels and WM integrity markers, specifically MD, and ISOVF, based on Model 3 with additional adjustment for total scores of the PHQ-9 and GAD-7. Stratified analyses by sex (female/male) were performed to assess potential effect modification. Effect estimates are presented as βs coefficients with corresponding 95% CIs, and FDR correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons across P values. To examine potential mechanistic pathways, we conducted mediation analyses to assess whether alterations in white matter microstructure mediate the associations between BRI and psychiatric symptoms. Specifically, we treated BRI as the independent variable, psychiatric symptoms as dependent variables, and the MD and ISOVF values of 15 major white matter tracts as potential mediators. Analyses were performed using the mediation package in R, with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals based on 1,000 resamples to determine statistical significance.

To assess the robustness of our findings, several sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, we restricted the cohort to individuals with White European ancestry, given that non-White participants represent only approximately 3% of the total dataset. Second, we categorized BRI into four levels, using the first quartile (Q1) as the reference group. Third, to minimize bias, we excluded participants who had been diagnosed with mental disorders within the first two years of follow-up. Fourth, recognizing the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our results, we advanced the follow-up deadline to December 31, 2019. The statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05. All analyses were conducted using the R software, version 4.2.2.

Data availability

The data used in the present study are available from the UK Biobank with restrictions applied. Access to the UK Biobank data can be requested through a standard protocol (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/register-apply/). This research has been conducted with UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 99001 (2023-01-31 to 2026-01-31). Data analysis and results representation were produced by R software (https://www.r-project.org/) and BioRender (https://app.biorender.com/). The codes in detail for statistical analysis are available upon request from corresponding authors.

References

Global and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 137–150 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(21)00395-3

Wallace, C. W. & Fordahl, S. C. Obesity and dietary fat influence dopamine neurotransmission: exploring the convergence of metabolic state, physiological stress, and inflammation on dopaminergic control of food intake. Nutr. Res. Rev. 35, 236–251. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954422421000196 (2022).

Kawade, N. & Yamanaka, K. Novel insights into brain lipid metabolism in alzheimer’s disease: oligodendrocytes and white matter abnormalities. FEBS Open. Bio. 14, 194–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/2211-5463.13661 (2024).

Shichkova, P., Coggan, J. S., Markram, H. & Keller, D. Brain metabolism in health and neurodegeneration: the interplay among neurons and astrocytes. Cells 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13201714 (2024).

Devlin, M. J., Yanovski, S. Z. & Wilson, G. T. Obesity: what mental health professionals need to know. Am. J. Psychiatry. 157, 854–866. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.854 (2000).

Migueles, J. H. et al. Effects of an exercise program on cardiometabolic and mental health in children with overweight or obesity: A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 6, e2324839. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.24839 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. The association between metabolic score for visceral fat and depression in overweight or obese individuals: Evidence from NHANES. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1482003. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1482003 (2024).

Uchida, K. et al. Association between abdominal adiposity and cognitive decline in older adults: A 10-year community-based study. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 28, 100175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnha.2024.100175 (2024).

Thomas, D. M. et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obes. (Silver Spring). 21, 2264–2271. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20408 (2013).

Avila, C. et al. An overview of links between obesity and mental health. Curr. Obes. Rep. 4, 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-015-0164-9 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Predicting metabolic syndrome by obesity- and lipid-related indices in mid-aged and elderly chinese: A population-based cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1201132. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1201132 (2023).

Calderón-García, J. F. et al. Effectiveness of body roundness index (BRI) and a body shape index (ABSI) in predicting hypertension: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111607 (2021).

Khanmohammadi, S. et al. Effectiveness of body roundness index for the prediction of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 24, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-025-02544-3 (2025).

Fahami, M., Hojati, A. & Farhangi, M. A. Body shape index (ABSI), body roundness index (BRI) and risk factors of metabolic syndrome among overweight and obese adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disorders. 24, 230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-024-01763-6 (2024).

Qiu, L., Xiao, Z., Fan, B., Li, L. & Sun, G. Association of body roundness index with diabetes and prediabetes in US adults from NHANES 2007–2018: A cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 23, 252. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02238-2 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Body Roundness Index and All-Cause Mortality Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open 7, e2415051 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051

Zhang, L. et al. The relationship between body roundness index and depression: A cross-sectional study using data from the National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2011–2018. J. Affect. Disord. 361, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.05.153 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Predicting depressive symptom by cardiometabolic indicators in mid-aged and older adults in china: A population-based cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1153316. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1153316 (2023).

Hawton, K., Casañas, I. C. C., Haw, C. & Saunders, K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 147, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004 (2013).

Nigatu, Y. T., Reijneveld, S. A., de Jonge, P., van Rossum, E. & Bültmann, U. The combined effects of obesity, abdominal obesity and major depression/anxiety on Health-Related quality of life: The lifelines cohort study. PLoS One. 11, e0148871. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148871 (2016).

Chen, W. et al. Mendelian randomization analyses identify bidirectional causal relationships of obesity with psychiatric disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 339, 807–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.044 (2023).

Ahlberg, A. C. et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms in relation to anthropometry and metabolism in men. Psychiatry Res. 112, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00192-0 (2002).

Wiltink, J. et al. Associations between depression and different measures of obesity (BMI, WC, whtr, WHR). BMC Psychiatry. 13, 223. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-13-223 (2013).

Hryhorczuk, C., Sharma, S. & Fulton, S. E. Metabolic disturbances connecting obesity and depression. Front. Neurosci. 7, 177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00177 (2013).

Després, J. P. & Lemieux, I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature 444, 881–887. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05488 (2006).

Li, Y. et al. Body roundness index and Waist-Hip ratio result in better cardiovascular disease risk stratification: Results from a large Chinese Cross-Sectional study. Front. Nutr. 9, 801582. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.801582 (2022).

Lotfi, K. et al. A body shape index and body roundness index in relation to anxiety, depression, and psychological distress in adults. Front. Nutr. 9, 843155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.843155 (2022).

Ozato, N. et al. Association between visceral fat and brain structural changes or cognitive function. Brain Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081036 (2021).

Raji, C. A. et al. Visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat predict brain volume loss at midlife in 10,001 individuals. Aging Dis. 15, 1831–1842. https://doi.org/10.14336/ad.2023.0820 (2024).

Fernández-Sánchez, A. et al. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12, 3117–3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms12053117 (2011).

Zhang, C. X. W., Candia, A. A. & Sferruzzi-Perri, A. N. Placental inflammation, oxidative stress, and fetal outcomes in maternal obesity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 35, 638–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2024.02.002 (2024).

Naomi, R. et al. The role of oxidative stress and inflammation in obesity and its impact on cognitive Impairments-A narrative review. Antioxid. (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12051071 (2023).

Beydoun, M. A. et al. Cardiovascular health, infection burden and their interactive association with brain volumetric and white matter integrity outcomes in the UK biobank. Brain Behav. Immun. 113, 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2023.06.028 (2023).

Bao, Y. et al. Chronic Low-Grade inflammation and brain structure in the middle-aged and elderly adults. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142313 (2024).

Keller, J. et al. HPA axis in major depression: cortisol, clinical symptomatology and genetic variation predict cognition. Mol. Psychiatry. 22, 527–536. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.120 (2017).

Smith, D. T., Mouzon, D. M. & Elliott, M. Reviewing the assumptions about men’s mental health: An exploration of the gender binary. Am. J. Mens Health. 12, 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988316630953 (2018).

McHugh, R. K., Votaw, V. R., Sugarman, D. E. & Greenfield, S. F. Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 66, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.012 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Long-term exposure to ambient benzene and brain disorders among urban adults. Nat. Cities. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-024-00156-z (2024).

Sehgal, P. et al. Visceral adiposity independently predicts time to flare in inflammatory bowel disease but body mass index does not. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 30, 594–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izad111 (2024).

Björntorp, P. Endocrine abnormalities of obesity. Metabolism 44, 21–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(95)90315-1 (1995).

Payant, M. A. & Chee, M. J. Neural mechanisms underlying the role of fructose in overfeeding. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 128, 346–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.06.034 (2021).

Tsigos, C. & Chrousos, G. P. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 53, 865–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00429-4 (2002).

Raison, C. L., Capuron, L. & Miller, A. H. Cytokines Sing the blues: Inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 27, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006 (2006).

Milaneschi, Y., Simmons, W. K., van Rossum, E. F. C. & Penninx, B. W. Depression and obesity: Evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol. Psychiatry. 24, 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0017-5 (2019).

Ogrodnik, M. et al. Obesity-Induced cellular senescence drives anxiety and impairs neurogenesis. Cell. Metab. 29, 1061–1077e1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.12.008 (2019).

Mokhtari, T., Irandoost, E. & Sheikhbahaei, F. Stress, pain, anxiety, and depression in endometriosis-Targeting glial activation and inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 132, 111942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111942 (2024).

Ma, X. et al. Lactobacillus casei and its supplement alleviate Stress-Induced depression and anxiety in mice by the regulation of BDNF expression and NF-κB activation. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112488 (2023).

Boxer, A. & Gill, P. R. Predicting anxiety from the complex interaction between masculinity and spiritual beliefs. Am. J. Mens Health. 15, 15579883211049021. https://doi.org/10.1177/15579883211049021 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 attenuated high-fat diet induced anxiety-like behavior and social withdrawal of male mice by improving antioxidant capacity, intestinal barrier function and modulating intestinal dysbiosis. Behav. Brain Res. 438, 114172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114172 (2023).

Türkmen, H. & Sezer, F. The effect of fear of happiness as a cultural phenomenon on anxiety and Self-Efficacy in the puerperae. J. Transcult Nurs. 34, 356–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/10436596231188361 (2023).

Bolkan, S. S. et al. Thalamic projections sustain prefrontal activity during working memory maintenance. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4568 (2017).

Delevich, K., Jaaro-Peled, H., Penzo, M., Sawa, A. & Li, B. Parvalbumin interneuron dysfunction in a Thalamo-Prefrontal cortical circuit in Disc1 locus impairment mice. eNeuro https://doi.org/10.1523/eneuro.0496-19.2020 (2020).

Pasha, E. P. et al. Visceral adiposity predicts subclinical white matter hyperintensities in middle-aged adults. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 11, 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2016.04.003 (2017).

Gonzales, M. M. et al. Central adiposity and the functional magnetic resonance imaging response to cognitive challenge. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 38, 1193–1199. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.5 (2014).

Alfaro-Almagro, F. et al. Image processing and quality control for the first 10,000 brain imaging datasets from UK biobank. Neuroimage 166, 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.10.034 (2018).

Miller, K. L. et al. Multimodal population brain imaging in the UK biobank prospective epidemiological study. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 1523–1536. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4393 (2016).

Maximov, I. I., Alnæs, D. & Westlye, L. T. Towards an optimised processing pipeline for diffusion magnetic resonance imaging data: effects of artefact corrections on diffusion metrics and their age associations in UK biobank. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 40, 4146–4162. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24691 (2019).

Beydoun, M. A. et al. Mediating and moderating effects of plasma proteomic biomarkers on the association between poor oral health problems and brain white matter microstructural integrity: the UK biobank study. Mol. Psychiatry. 30, 388–401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-024-02678-3 (2025).

Burke, A. & Jones, A. The development of an index of rural deprivation: A case study of norfolk, England. Soc. Sci. Med. 227, 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.019 (2019).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Defining and setting National goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: The American heart association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 121, 586–613. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.109.192703 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number: 82304102 (J. Ran); Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai, grant number: 23ZR1436200 (J. Ran); Shanghai Science and Technology Development Foundation, grant number: 22YF1421100 (J. Ran); Joint Research Fund for Medical and Engineering and Scientific Research at SJTU, grant number: YG2022QN003 (J. Ran); Shanghai Science and Technology Development Foundation, grant number: 23YF1421200 (L. Han). We thank the UK Biobank participants and the UK Biobank team for their work in collecting, processing, and disseminating the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G. contributed to methodology, validation, and the initial draft. Y.B. was responsible for visualization and contributed to the original draft. Y.L. worked on software and reviewed and edited the manuscript. X.C. and S.Y. curated data and contributed to software development. Y.Z., H.P., and X.D. provided resources and conducted investigations. L.H. and J.R. supervised the project, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and managed administration, with J.R. securing funding. All authors accept full responsibility for the work and the decision to publish.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, J., Bao, Y., Li, Y. et al. Body roundness index and mental health in middle-aged and elderly adults: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 22994 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06994-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06994-8