Abstract

Green food certification (GFC) represents a critical step toward achieving sustainable agricultural practices. However, its adoption among kiwifruit farmers in China remains limited, primarily due to financial constraints and varying levels of social capital. This study investigates kiwifruit farmers’ willingness to adopt (WTAd) and willingness to pay (WTP) for GFC, focusing on the role of social capital in shaping their decisions. Data were collected from 404 kiwifruit farmers in major kiwifruit-producing Provinces using a structured household survey. A non-parametric contingent valuation method estimated the expected WTP, while a double-hurdle model analyzed the impact of social capital on WTAd and WTP. Results showed that 52% of kiwifruit farmers were willing to adopt GFC, while only 34% were willing to pay for it, with the average WTP being CNY 912.24 per household per year. Key social capital factors, including network strength and institutional trust, were significantly associated with farmers’ WTAd and WTP. Additionally, training and perceived benefits positively impacted both WTAd and WTP, while socio-demographic factors such as age, education, and household labor availability exhibited nuanced effects. These findings highlight the critical role of social capital in promoting GFC adoption. Policymakers are encouraged to provide financial incentives, strengthen social networks, and enhance farmer training programs to bridge the economic and informational gaps that hinder the widespread adoption of sustainable practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread reliance on synthetic chemical inputs, such as fertilizers and pesticides, in Chinese agriculture has raised significant concerns about environmental contamination and threats to human health and ecosystems. Excessive chemical usage has been linked to soil degradation, water pollution, biodiversity loss, and risks to food safety, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable agricultural practices to mitigate these negative impacts1,2. To address these concerns, the Chinese government has implemented a comprehensive certification system for agricultural products that evaluates the entire production process, including the use of inputs, waste management, and environmental impacts, to encourage more sustainable farming practices3. Among these efforts, green food certification (GFC) has emerged as a critical initiative to balance agricultural productivity with ecological conservation by promoting reduced chemical input, efficient resource use, and better waste management. In recent years, the adoption of GFC has gained momentum, reflecting a broader shift toward environmentally sustainable practices in China4,5,6.

China is the world’s leading producer of kiwifruit, boasting the largest cultivation area and highest yield globally7. Despite this prominence, traditional production methods remain prevalent, and the adoption of GFC has been slow8,9. Kiwifruit production in China has historically been dominated by small-scale farmers, for whom certification is often prohibitively expensive, time-consuming, and labor-intensive. Additionally, the immediate economic benefits of certification are not always evident, further discouraging farmers from pursuing GFC adoption. While GFC promotes sustainable agricultural practices, reducing the environmental impact of kiwifruit farming and offering consumers healthier, safer food choices, the marginal private benefits of certified farming are typically lower than the corresponding marginal social benefits10. This disparity underscores the need for additional financial incentives to encourage wider adoption of GFC in kiwifruit production. Consequently, investigating farmers’ willingness to adopt (WTAd) and willingness to pay (WTP) for GFC is crucial to understanding and addressing the barriers to its implementation.

Rural Chinese society is characterized as a “guanxi” society, where relationships are primarily based on blood ties and geographical proximity11,12,13. Due to limitations, such as farmers’ educational levels, information literacy, and decision-making abilities, social capital plays a key role in the adoption of new production methods. This role is achieved through communication, mutual trust, and reciprocity among farmers, reflecting social networks, social trust, and social norms within the farming community8,14,15,16. Social networks represent the relationships accumulated through long-term iterative communication and interaction, reflecting the extent of contact between individuals17. Social trust is the sense of identification and reliance developed based on mutual communication and interaction18. Social norms are the values, ethical guidelines, and visions gradually formed through cooperation and interaction19,20,21. Compared with top-down government-driven promotion methods, social capital embeds into farmers’ lives, influencing their behavioral choices and decisions. Therefore, it is pertinent to examine the role of social capital in the adoption of GFC in the Chinese context as the government-driven promotional campaigns have not led to mass adoption.

Existing literature has predominantly focused on consumers’ WTP for green food and the factors influencing their decisions1,2. These studies have provided valuable insights into consumer behavior, particularly highlighting the demand-side dynamics of the green food market. However, relatively little attention has been directed toward the supply side, specifically the willingness of agricultural producers to adopt GFC and the factors influencing their decision-making. This represents a significant research gap, as producers are the key stakeholders in the implementation of sustainable agricultural practices like GFC. Understanding their behavior, motivations, and constraints is essential for the successful promotion and scaling of such certifications. To address this gap, this study focuses on the willingness of kiwifruit producers to adopt (WTAd) GFC and their willingness to pay (WTP) for certification costs. These two dependent variables—WTAd and WTP—are treated as distinct yet interconnected stages in the adoption process. WTAd represents the initial decision to adopt GFC, while WTP reflects the maximum amount producers are willing to invest in certification. Recognizing the multidimensional nature of decision-making, this research also examines the role of social capital in influencing both WTAd and WTP. By analyzing key dimensions of social capital—such as network size, network strength, institutional trust, and social norms—the study provides a comprehensive understanding of how interpersonal and institutional relationships shape the adoption and financial commitment to GFC among kiwifruit farmers.

The structure of this article is as follows: Sect. 2 provides details on data sources and the econometric models, Sect. 3 presents study results, Sect. 4 offers a discussion of the findings, and finally, the concluding section presents the findings and implications.

Materials and methods

This section illustrates the sampling method, study area, and empirical approach implemented in the analysis, including the statistical models.

Sampling

A four-stage random sampling method was used for the data collection. China has five major kiwifruit production areas: (i) the northern foot of Qinling Mountains in Shaanxi Province, (ii) Dabie Mountain, Henan Province’s Funiu Mountain, and Tongbai Mountain, (iii) the Guizhou plateau and the west of Hunan Province, (iv) Heyuan Heping county in Guangdong Province, and (v) the northwest of Sichuan Province and the southwest of Hubei Province. In the first stage, Zhouzhi and Mei counties in Shaanxi Province and Xixia county in Henan Province were purposively selected as the three major growing areas for kiwifruit (Fig. 1). Zhouzhi county had the highest kiwifruit output in China, with a planting area of 28,800 hectares and a total production of 530,000 tonnes in 2019 (Table 1). Mei county ranked second in output, with a planting area and output of 20,133 hectares and 495,000 tonnes, respectively. Xixia county has the richest wild kiwifruit planting resource in China, boasting an expansive area of 26,600 hectares, along with 8,000 hectares of planted kiwifruit area, making it the county with the highest kiwifruit planting area in China.

Study area map. The map was created using ArcGIS 10.6 (Esri, https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-desktop/overview).

The second stage was the purposive selection of the towns and villages with a high concentration of kiwifruit growers, using the information provided by the local agricultural and rural bureaus. In the third stage, a list of kiwifruit growers in the sample areas was obtained from the local government office, including farmers who had acquired the GFC and those who had not. Finally, farmers were randomly and proportionately selected from the list to serve as survey participants. The sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula22. Assuming a 5% margin of errors, the minimum suggested sample size was determined as follows (Eq. (1)):

where z is the z score, ε is the margin of errors, and \({\hat{p}}\) is the population proportion.

The proportional sample size from each county is presented in Table 2. The actual sample included 404 kiwifruit farmers, of which 97 had obtained the GFC and 307 were conventional farmers. The lower number of GFC kiwifruit farmers was due to its lower adoption status. The research team conducted face-to-face interviews with each farmer to collect information on individual and family status, kiwifruit production, management, certification, and sales.

Empirical analysis

Contingent valuation method

The contingent valuation method (CVM) is one of the most commonly used methods for non-market valuation that measures WTP for environmental scenarios12,17,23. To ensure the robustness of the CVM, this study undertook the following measures: (i) conducting multiple pre-surveys in the main kiwifruit producing areas to determine a reasonable bidding range and reduce the bias of the bidding starting point, (ii) providing detailed explanations to kiwifruit farmers about the concept and content of GFC, Chinese laws, regulations, policies, and other information to reduce information bias, and (iii) introducing the identity of the surveyor to kiwifruit farmers and emphasizing that this survey is only for academic research purposes, reducing strategic bias.

Using the non-parametric estimation method in the CVM, the expected WTP (E(WTP)) for GFC among kiwifruit farmers was calculated as \(\:E\left(WTP\right)=\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}AiPi\), where Ai represents the amount the kiwifruit farmers are willing to pay and Pi is the probability that a kiwifruit farmer chooses a certain amount.

Dependent variables

The two dependent variables in this research are the WTAd, whether the kiwifruit farmer was willing to adopt GFC, and the WTP, the maximum amount the kiwifruit farmer was willing to pay for GFC (Table 3).

Statistical model

Kiwifruit farmers’ decisions regarding GFC adoption were assumed to occur in sequential stages. The first stage assessed “whether they were willing to adopt GFC”. If the decision was positive in the first stage, the second stage assessed “how much they were willing to pay for GFC”. Dichotomous choice models, such as the Probit model, have been widely used to estimate the probability of adoption and its determinants, whereas the Tobit regression model and ordinary least squares estimation have been used to analyze the factors affecting individuals’ WTP24,25,26. However, these methods assume independence of WTAd and WTP27,28. Contrarily, the Heckman model can achieve a two-step estimation regarding the decision-making of technology adoption if the two processes are not independent of each other, where the error term in the first stage WTAd transfers to the second stage WTP. Similarly, the double-hurdle model can analyze the factors associated with farmers’ WTAd and WTP for GFC assuming interdependence of the two error terms29,30,31. This research employed the double-hurdle model for estimation.

The first stage in the adoption process determines whether kiwifruit farmers are willing to adopt the GFC. The second stage determines the WTP for GFC by kiwifruit farmers. Specifically, the double-hurdle model estimates the correlation coefficient ρ between the error terms of the model in stages one and two. If the estimation results reject the null hypothesis of no interdependence, the double-hurdle model is regarded as more appropriate.

The Probit equation for the first stage is constructed as follows:

Equation (2) represents kiwifruit farmers’ unwillingness to adopt GFC, while Eq. (3) represents their WTAd it. Φ (∙) denotes the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. Here, yi represents the observed dependent variable, i.e., whether kiwifruit farmers are willing to adopt the GFC, x1i represents a vector of exogenous variables, such as social networks, social trust, and social norms, and α represents a vector of the corresponding parameters to be estimated. The subscript i represents the i-th kiwifruit farmer of the sample.

The equation for the second stage is constructed as follows:

where E[∙] represents the conditional expected value of the WTP for GFC. λ(∙) is the inverse Mills ratio, x2i represents a vector of exogenous variables, such as social networks, social trust, and social norms, and β is a vector of the corresponding parameters to be estimated. δ represents the standard deviation of the truncated normal distribution.

Building on Eq. (2) to (4), the log-likelihood function is constructed as follows:

where lnZ represents the value of the log-likelihood function, feeding into the maximum likelihood estimation to obtain the relevant parameters. The double-hurdle model was estimated using Stata 17.

Independent variables

There are various factors that may affect the adoption of GFC. Some of these variables are self-explanatory and are presented in Table 3. Others are discussed in detail as follows.

Based on existing research32,33 this study employs two types of social networks: network size and network strength20. Network size is operationalized as “the number of relatives and friends in the community”, while network strength is operationalized as “the frequency of communication with relatives and friends in the community”. The study also distinguishes between two types of social trust: interpersonal trust and institutional trust20. Interpersonal trust is primarily assessed by “the level of trust in relatives and friends in the community”. Given China’s unique governance system, village cadres typically serve as intermediaries between kiwifruit farmers and the government. Therefore, institutional trust is measured by “the level of trust in village cadres”34. Additionally, social norms are classified into two types: descriptive norms and injunctive norms35. Descriptive norms capture farmers’ perceptions of what others are doing, and are measured by whether “relatives and friends in the community have already adopted GFC.” In contrast, injunctive norms reflect perceived social expectations, and are measured by whether “relatives and friends in the community believe that we should adopt GFC”.

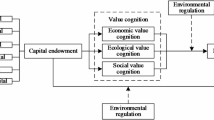

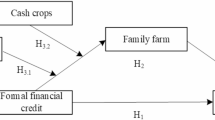

Building upon the preceding discussion of key variables and modeling techniques, Fig. 2 provides a visual synthesis of the overall empirical strategy, including sampling procedures and WTAd/WTP analysis via the double-hurdle model. Figure 3 depicts the distribution of farmers’ WTAd GFC, while Fig. 4 illustrates the distribution of stated WTP for GFC.

Results

Kiwifruit farmers’ WTAd and WTP for GFC

Table 3 shows that 52% of the kiwifruit farmers were willing to adopt GFC. Using the non-parametric estimation method in the CVM, the expected willingness to pay (E(WTP)) among all kiwifruit farmers was calculated to be CNY 181.36/mu/year. The frequency distribution of the WTP bidding value is shown in Table 4. A total of 268 respondents, or 66.3% of the sample, expressed zero WTP. A total of 14 respondents, or 3.5%, selected the tender value of CNY 200/mu/year. A total of 19 respondents, or 4.7%, selected CNY 300/mu/year and 33 respondents, or 8.2%, selected CNY 500/mu/year. Fifteen respondents, or 3.7%, expressed the value of CNY 1,000/mu/year. This shows that despite some respondents expressing high WTP for GFC, two-third of the respondents expressed no ex-ante WTP. This implies that kiwifruit farmers are generally unwilling to pay large amounts for GFC. Considering the average farm size per household (5.03 mu) in the sample, this translates to the expected WTP being CNY 912.24/household/year, the median WTP being zero, and the third quartile WTP being CYN 1,509/household/year. To further support the interpretation of these results, Fig. 3 displays the distribution of farmers’ willingness to adopt (WTAd) GFC as a percentage of respondents, and Fig. 4 presents the percentage distribution of their stated willingness to pay (WTP) for GFC, based on the bidding values used in the CVM.

Determinants of WTAd and WTP

The estimation of the double-hurdle model in Table 5 portrays the factors influencing kiwifruit farmers’ WTAd and WTP for GFC. The Wald chi-square value of 104.71 suggests the statistical significance of the choice of the double-hurdle model. The results reveal that kiwifruit farmers’ WTAd GFC is significantly influenced by social capital factors. Network strength and institutional trust are positively and significantly correlated with WTAd, along with descriptive norms, participation in training, education level, the number of family members engaged in kiwifruit farming, and perceived benefits. On the contrary, injunctive norms and the age of the household head negatively affect WTAd. Specifically, an increase in network strength and institutional trust by one level is associated with a higher Z-score for WTAd by 0.187 and 0.252, respectively, holding other variables unchanged. When the number of friends and relatives adopting GFC increases by one member, the same Z-score rises by 0.172. Participation in government-organized GFC training elevates the Z-score by 0.639; an additional year of education adds 0.123; and one more family member involved in kiwifruit farming contributes + 0.232 to the Z-score. On the other hand, a one-unit increase in injunctive norms and an additional year in the age of the household head reduce the Z-score by 0.218 and 0.015, respectively. Kiwifruit farmers’ WTP for GFC is influenced by several factors. Network size, network strength, institutional trust, training participation, and perceived benefits significantly and positively affect WTP, while education and farm labor have negative effects. When network size increases by one level, the WTP rises by 20.772 on average, conditional on WTAd being 1. Likewise, as network strength increases by one level, the WTP rises by 132.159. When farmers participate in training, the WTP rises by 241.018. A one-level increase in perceived benefits of GFC raises the WTP by 70.168. However, a one-year increase in years of schooling reduces the WTP by 2.699, while a one-person increase in farm labor reduces the WTP by 3.533.

Discussion

The findings underscore a stark disparity between kiwifruit farmers’ WTP and the government-set GFC fee of CNY 8,000 for three years (CNY 2,667/year). Even the households in the third quartile find the GFC unworthy of the fee, without external support, highlighting a significant barrier to adoption. In fact, only 11.6% of the households are currently willing to pay the full amount of the government-set fee, reflecting the limited economic feasibility of the existing pricing structure. To increase this percentage to 20, a subsidy of at least CNY 655/household/year would be necessary. This subsidy would effectively reduce the annual GFC fee to CNY 2,012/household, making it valuable for 22.5% of the kiwifruit farmers. Such financial support would not only promote greater adoption but also enable farmers to overcome the cost-related barriers associated with sustainable agricultural practices like GFC. Studies have shown that subsidies and financial incentives play a critical role in promoting the adoption of environmentally sustainable practices among smallholder farmers by reducing the upfront cost burden and improving perceived economic viability27,36. Furthermore, reducing certification costs through targeted subsidies can align private benefits with societal benefits, addressing the mismatch that often hinders voluntary participation in eco-friendly certifications10. These measures, coupled with awareness campaigns, may create a more conducive environment for GFC adoption.

In terms of social capital characteristics, social network variables, such as network strength, displayed positive effects on kiwifruit farmers’ WTAd and WTP for GFC. Farmers who communicate with others more frequently may be better able to access and share information resources related to GFC, gaining a more comprehensive understanding of its benefits, operational methods, and market demand, which is associated with higher likelihood of adoption and WTP. This result is consistent with Ref34. who found that stronger social networks among farmers in rural China significantly enhance their collective efficacy and participation in sustainable practices, particularly in water environmental management, focusing on staple crops like rice and wheat. Refs20,37. have suggested that the larger the social network size of farmers, the more stable their social resources, effectively improving their capacity to adopt new agricultural production methods. Institutional trust was positively associated with both WTAd and WTP for GFC. Village cadres in China are typically at the forefront of agricultural technology, possessing abundant information resources and having a certain degree of influence and cohesion20,38,39. Moreover, the higher the level of trust among kiwifruit farmers in village cadres, the more likely they are to accept and comply with their decisions and leadership20,34 thus contributing to their increased acceptance of GFC. However, it is also possible that farmers who have already adopted or paid for certification develop greater institutional trust through their engagement with local institutions and perceived support. Therefore, while our model identifies significant associations, the direction of causality should be interpreted with caution. Descriptive norms were positively associated with their WTAd GFC. If farmers perceive that their peers widely adopt environmentally responsible behaviors, they may feel a stronger sense of alignment with their social group and view such adoption as both rational and wise, thereby increasing their likelihood of following suit38,40. Somewhat surprisingly, injunctive norms weakened kiwifruit farmers’ WTAd GFC. It may be the case that strong peer pressure to adopt GFC limits farmers’ autonomy, weakens their intrinsic motivation, and potentially leads to reluctance to adoption. Additionally, participation in agricultural training was positively correlated with both WTAd and WTP for GFC. This aligns with other studies regarding the effects of agricultural training on the adoption of new production methods and technologies41,42,43.

Education exhibited contrasting effects between WTAd and WTP. Specifically, education level was positively associated with WTAd, suggesting that an early stage of education enhances farmers’ understanding of the benefits and requirements of GFC, thereby encouraging adoption44,45. However, among farmers already willing to adopt, higher education levels were associated with a lower WTP for certification, which may be because highly educated farmers are more capable of critically evaluating the cost-benefit trade-offs of certification and may become more selective in their investment decisions. Such an inverted U-shaped relationship is consistent with findings in previous studies on technology adoption behavior, where moderately educated farmers tend to have higher adoption enthusiasm, while highly educated farmers exhibit more strategic decision-making42,46. Similarly, a greater number of family members involved in kiwifruit farming initially facilitated the likelihood of GFC adoption, as additional labor resources can ease the burden of implementing the labor-intensive certification practices47. However, beyond a certain threshold, having excessive family labor may lead households to diversify into other agricultural activities or alternative production systems that are less dependent on certification schemes48 thereby reducing their WTP for GFC. This dynamic reflects household labor allocation theories, where opportunity cost considerations influence production choices36,49.

Furthermore, perceived benefits were positively associated with both WTAd and WTP for GFC. Kiwifruit farmers are likely to be rational decision-makers, maximizing overall utility and aligning their choices with what they perceive as most advantageous for sustainable production and economic gains, which is in line with Refs42,50.

Although this study provides valuable insights into the factors associated with kiwifruit farmers’ WTAd and WTP for GFC, it is important to acknowledge certain methodological limitations. Specifically, the double-hurdle model identifies statistical associations rather than establishing causal relationships. Potential endogeneity issues, such as omitted variable bias, measurement error bias, or reverse causality, may still influence the results. This limitation is consistent with the characteristics of double-hurdle models as discussed in previous studies51,52. Future research employing experimental designs, instrumental variable approaches, or longitudinal data would be beneficial to better uncover the causal mechanisms behind farmers’ adoption decisions. In addition, the CVM used to estimate WTP is subject to hypothetical bias, as respondents’ stated preferences may not fully reflect actual valuation. Although we conducted pre-surveys to calibrate the bidding range and emphasized the academic, non-commercial nature of the questionnaire, this limitation remains and should be taken into account when interpreting WTP estimates53,54.

Conclusion and policy implications

While the GFC in Chinese agriculture reduces adverse environmental impacts due to lower external inputs, the adoption of sustainable practices outlined in the kiwifruit scheme has remained stagnant. The CVM was employed to estimate the WTP for GFC by kiwifruit farmers, and the double-hurdle model was utilized to assess the factors influencing the WTAd and WTP for sustainable kiwifruit production in China’s major kiwifruit belt. The research findings indicated that 52% of the kiwifruit farmers were willing to adopt GFC, with a WTP ranging from zero to CNY 2,000/mu/year. Social capital factors, including network strength, institutional trust, and descriptive norms, were significantly associated with the likelihood of GFC adoption. Other non-social capital factors driving sustainable practices adoption included training, education, family labor in farming, and perceived benefits. However, among those who were already willing to adopt GFC, some factors negatively impacted WTP, such as higher education levels and larger family labor resources, implying non-linear effects of these factors. Additionally, injunctive norms and the age of the household head negatively influenced GFC adoption. These identified associations provide evidence-based implications to policymakers, agricultural extension officers, and other promoters of sustainable agricultural practices for designing effective strategies. Social capital appears to be strongly associated with farmers’ adoption of GFC. Therefore, strengthening rural social capital may be an effective approach to enhance kiwifruit farmers’ participation in GFC.

Based on these results, we propose several policy implications. First, fostering strong local social capital—especially through institutional trust and embedded technical assistance—can promote voluntary adoption and reduce the overreliance on top-down interventions. Second, attention should be given to differentiated farmer segments when designing incentive schemes, particularly in light of the non-linear effects of education and labor characteristics. In addition to the estimated level of financial support, further consideration should be provided to the design of subsidy programs. Direct, one-off subsidies (e.g., fee reductions) may effectively lower entry barriers, while continuous or indirect subsidies (e.g., training support, cooperative services) can sustain long-term participation. However, poorly designed subsidies may create unintended consequences, such as farmer dependency, fiscal strain, or market distortion. To mitigate these risks, we recommend integrating financial subsidies with complementary non-monetary support strategies—such as technical assistance embedded within social networks, peer-led demonstrations, and improved market access for GFC-certified products—in order to strengthen rural social capital and enhance long-term adoption outcomes.

Furthermore, there is a need to vigorously develop basic levels of education in rural areas, continuously improve the training in green production, and enhance farmers’ perceived value as these strategies are likely effective in driving the adoption of GFC.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed for the current study will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hu, Y., Cheng, H. & Tao, S. Environmental and human health challenges of industrial livestock and poultry farming in China and their mitigation. Environ. Int. 107, 111–130 (2017).

Fei, X., Lou, Z., Xiao, R., Ren, Z. & Lv, X. Source analysis and source-oriented risk assessment of heavy metal pollution in agricultural soils of different cultivated land qualities. J. Clean. Prod. 341, 130942 (2022).

Guo, Z., Bai, L. & Gong, S. Government regulations and voluntary certifications in food safety in china: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 90, 160–165 (2019).

Scott, S., Si, Z., Schumilas, T. & Chen, A. Contradictions in state- and civil society-driven developments in china’s ecological agriculture sector. Food Policy. 45, 158–166 (2014).

Chengjun, S. et al. Construction process and development trend of ecological agriculture in China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 42, 624–632 (2022).

Dong, L., Zulfiqar, F., Yaseen, M., Tsusaka, T. W. & Datta, A. Why are Kiwifruit farmers reluctant to adopt eco-friendly green food certification? An investigation of attitude-behavior inconsistency. J. Agric. Food Res. 16, 101106 (2024).

FAO. Supply Utilization Accounts (2010 – onwards). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2020). https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/SCL (Accessed 11 November 2022).

Liu, Y. & Huang, J. Social capital, risk perception, and farmers’ adoption of sustainable agricultural practices in China. Sustain. Dev. 28, 42–53 (2020).

Huang, J. et al. Evaluation of the quality of fermented Kiwi wines made from different Kiwifruit cultivars. Food Biosci. 42, 101051 (2021).

Liu, R., Gao, Z., Yan, G. & Ma, H. Why should we protect the interests of ‘green food’ certified product growers? Evidence from Kiwifruit production in China. Sustainability 10, 4797 (2018).

Smart, A. Guanxi, gifts, and learning from china: A review essay. Anthropos 93, 559–565 (1998).

Danning, W. Guanxi or Li Shang wanglai?? Reciprocity, social support networks and social creativity in a Chinese village. China J. 66, 184–186 (2011).

Barbalet, J. The analysis of Chinese rural society: Fei Xiaotong revisited. Mod. China. 47, 355–382 (2021).

Issahaku, A. R. & Abdulai, A. Small-holder farmers’ climate change adaptation practices in the upper East region of Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 19, 743–759 (2017).

Cofré-Bravo, G., Klerkx, L. & Engler, A. Combinations of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital for farm innovation: how farmers configure different support networks. J. Rural Stud. 69, 53–64 (2019).

Castillo, G. M. L., Engler, A. & Wollni, M. Planned behavior and social capital: Understanding farmers’ behavior toward pressurized irrigation technologies. Agric. Water Manag. 243, 106524 (2021).

Koch, L., Gorris, P., Prell, C. & Pahl-Wostl, C. Communication, trust and leadership in co-managing biodiversity: A network analysis to understand social drivers shaping a common narrative. J. Environ. Manag. 336, 117551 (2023).

Slijper, T., Urquhart, J., Poortvliet, P. M., Soriano, B. & Meuwissen, M. P. M. Exploring how social capital and learning are related to the resilience of Dutch arable farmers. Agric. Syst. 198, 103385 (2022).

Li, F. et al. Incentive mechanism for promoting farmers to plant green manure in China. J. Clean. Prod. 267, 122197 (2020).

Wang, W., Zhao, X., Li, H. & Zhang, Q. Will social capital affect farmers’ choices of climate change adaptation strategies? Evidence from rural households in the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, China. J. Rural Stud. 83, 127–137 (2021).

He, J. et al. Effect of land transfer on farmers’ willingness to pay for straw return in Southwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 369, 133397 (2022).

Cochran, W. G. Sampling Techniques 3rd edn (Wiley, 1977).

Lyon, F. Trust, networks and norms: the creation of social capital in agricultural economies in Ghana. World Dev. 28, 663–681 (2000).

Boccaletti, S. & Moro, D. Consumer willingness-to-pay for GM food products in Italy. AgBioForum 3, 259–267 (2000).

Obeng, E. A. & Aguilar, F. X. Willingness-to-pay for restoration of water quality services across geo-political boundaries. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 3, 100037 (2021).

Waruingi, E., Ateka, J., Mbeche, R. & Herrmann, R. Understanding the nexus between forest dependence and willingness to pay for forest conservation: case of forest dependent households in Kenya. Econ. Rev. 5, 23–43 (2023).

Gao, Y., Zhao, D., Yu, L. & Yang, H. Influence of a new agricultural technology extension mode on farmers’ technology adoption behavior in China. J. Rural Stud. 76, 173–183 (2020).

Sarma, P. K. Adoption and impact of super granulated Urea (Guti Urea) technology on farm productivity in bangladesh: A Heckman two-stage model approach. Environ. Challenges. 5, 100228 (2021).

Okoffo, E. D., Denkyirah, E. K. & Adu, D. T. & Fosu-Mensah, B. Y. A double-hurdle model estimation of cocoa farmers’ willingness to pay for crop insurance in Ghana. SpringerPlus 5, 873 (2016).

Khoza, T. M., Senyolo, G. M., Mmbengwa, V. M. & Soundy, P. Socio-economic factors influencing smallholder farmers’ decision to participate in agro-processing industry in Gauteng province, South Africa. Cogent Soc. Sci. 5, 1664193 (2019).

Tasila Konja, D. & Mabe, F. N. Market participation of smallholder groundnut farmers in Northern ghana: generalised double-hurdle model approach. Cogent Econ. Finance. 11, 2202049 (2023).

Bian, Y. J. Source and functions of urbanites’ social capital: A network approach. Soc. Sci. China. 3, 136–146 (2004).

Łopaciuk-Gonczaryk, B. Does participation in social networks foster trust and respect for other people? Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 11, 1733 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Hu, N., Yao, L., Zhu, Y. & Ma, Y. The role of social network embeddedness and collective efficacy in encouraging farmers’ participation in water environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 340, 117959 (2023).

Cialdini, R. B., Kallgren, C. A. & Reno, R. R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and Reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 24, 201–234 (1991).

Zulfiqar, F. & Thapa, G. B. Determinants and intensity of adoption of ‘better cotton’ as an innovative cleaner production alternative. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 3468–3478 (2018).

Saptutyningsih, E., Diswandi, D. & Jaung, W. J. Does social capital matter in climate change adaptation? A lesson from agricultural sector in yogyakarta, Indonesia. Land. Use Policy. 95, 104189 (2020).

Li, B., Xu, C., Zhu, Z. & Kong, F. How to encourage farmers to recycle pesticide packaging wastes: subsidies vs. social norms. J. Clean. Prod. 367, 133016 (2022).

Reuters. China seeks to boost food output with five-year smart farming plan. Retrieved Reuters (2024).

MacGillivray, B. H. Beyond social capital: the norms, belief systems, and agency embedded in social networks shape resilience to Climatic and geophysical hazards. Environ. Sci. Policy. 89, 116–125 (2018).

Liu, Y., Ruiz-Menjivar, J., Zhang, L., Zhang, J. & Swisher, M. E. Technical training and rice farmers’ adoption of low-carbon management practices: the case of soil testing and formulated fertilization technologies in hubei, China. J. Clean. Prod. 226, 454–462 (2019).

Zulfiqar, F., Datta, A., Tsusaka, T. W. & Yaseen, M. Micro-level quantification of determinants of eco-innovation adoption: an assessment of sustainable practices for cotton production in Pakistan. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 28, 436–444 (2021).

Mgendi, B. G., Mao, S. & Qiao, F. Does agricultural training and demonstration matter in technology adoption? The empirical evidence from small rice farmers in Tanzania. Technol. Soc. 70, 102024 (2022).

Fielke, S. J. & Bardsley, D. K. The importance of farmer education in South Australia. Land. Use Policy. 39, 301–312 (2014).

Sharifzadeh, M. S. & Abdollahzadeh, G. The impact of different education strategies on rice farmers’ knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) about pesticide use. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 20, 312–323 (2021).

Salaisook, P., Faysse, N. & Tsusaka, T. W. Reasons for adoption of sustainable land management practices in a changing context: A mixed approach in Thailand. Land. Use Policy. 96, 104676 (2020).

Sarkar, A., Wang, H., Rahman, A., Qian, L. & Memon, W. H. Evaluating the roles of the farmer’s cooperative for fostering environmentally friendly production technologies: A case of kiwi-fruit farmers in meixian, China. J. Environ. Manag. 301, 113858 (2022).

Jena, P. R., Stellmacher, T. & Grote, U. Can coffee certification schemes increase incomes of smallholder farmers? Evidence from jinotega, Nicaragua. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 19, 45–66 (2017).

Kersting, S. & Wollni, M. New institutional arrangements and standard adoption: evidence from small-scale fruit and vegetable farmers in Thailand. Food Policy. 37, 452–462 (2012).

Liu, R., Yu, C., Jiang, J., Huang, Z. & Jiang, Y. Farmer differentiation, generational differences and farmers’ behaviors to withdraw from rural homesteads: evidence from chengdu, China. Habitat Int. 103, 102231 (2020).

Cragg, J. G. Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica 39, 829–844 (1971).

Heckman, J. J. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47, 153–161 (1979).

Carson, R. T. & Groves, T. Incentive and informational properties of preference questions. Environ. Resour. Econ. 37, 181–210 (2007).

Loomis, J. B. Strategies for overcoming hypothetical bias in stated preference surveys. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 39, 34–46 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the kiwifruit farmers for their cooperation and assistance.

Funding

The scholarship provided by the China Scholarship Council to the first author is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LD: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing - original draft. FZ: methodology, formal analysis, writing - review and editing. SF: visualization, writing - review and editing. MY: visualization, writing - review and editing. SSK: visualization, writing - review and editing. TWT: methodology, formal analysis, writing - review and editing. AD: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing - review and editing, supervision, project administration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. They agreed to its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, L., Zulfiqar, F., Fahad, S. et al. Role of social capital in kiwifruit farmers’ willingness to adopt and pay for sustainable green food certificates in China. Sci Rep 15, 20603 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06997-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06997-5