Abstract

Heart failure (HF) is a severe cardiovascular disease often worsened by respiratory infections like influenza, COVID-19, and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). This study aims to uncover the molecular commonalities among these respiratory diseases and their impact on HF, identifying key mediating genes. By performing differential expression analysis on GEO database data, we found 51 common molecules of three respiratory diseases. The gene module of HF was identified by weighted gene co-expression network analysis, and 10 characteristic genes of respiratory diseases that aggravate HF were obtained. GO and KEGG enrichment analysis showed that these genes were mainly involved in innate immune response, inflammation and coagulation pathways. By using three machine learning algorithms, LASSO, RF and SVM-RFE, we identified RSAD2 and IFI44L as key genes, and the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve verification results showed high accuracy (Area Under the Curve, AUC > 0.7). ssGSEA showed that RSAD2 was involved in complement and coagulation cascade reactions, while IFI44L was related to myocardial contraction in the progression of heart failure. DSigDB prediction results showed that 6 drugs such as acetohexamide may have potential therapeutic effects on HF aggravated by respiratory diseases. Immune infiltration analysis revealed significant differences in eight immune cell types between HF patients and healthy controls. Our findings enhance the understanding of molecular interactions between respiratory diseases and heart failure, paving the way for future research and therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure is a major public health challenge, affecting around 6.2 million adults in the United States, and its numbers are expected to keep rising as the population ages1. When heart failure patients develop respiratory infections, their risk of hospitalization and death increases significantly. Research shows that 15.3% of heart failure hospitalizations are linked to respiratory infections, and these patients have a 60% higher chance of dying while hospitalized2. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began in late 2019, public health systems worldwide have faced immense pressure3. While influenza rates decreased during the pandemic, it still contributed to the strain on healthcare resources4. In addition, community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)—one of the most common respiratory infections—became harder to treat during the COVID-19 pandemic due to co-infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus5,6. Symptoms like cough, shortness of breath, fever, inflammation, and immune system changes can worsen the burden on the heart in patients with heart failure7,8.

Research shows that respiratory infections, such as COVID-19, influenza, and CAP, can make heart failure worse, leading to higher rates of illness and death9. For example, COVID-19 increases the risk of heart injury and heart failure, especially in patients with existing heart conditions10. Similarly, influenza and CAP can trigger sudden worsening of heart failure, making it harder to manage these patients clinically11. These respiratory infections worsen heart failure in several ways, including causing inflammation, increasing the heart’s workload, and damaging heart function. However, how exactly these diseases interact with heart failure at the molecular level is not yet fully understood. Understanding these mechanisms is important for developing targeted treatments to help heart failure patients who suffer from respiratory infections.

In this study, we first identified genes associated with COVID-19, influenza, and CAP by analyzing gene expression patterns. Next, we used a method called Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to find genes linked to heart failure, identifying those that may play key roles in worsening heart failure due to respiratory infections. We then used functional analysis to understand what these genes do in the body. To identify the most important genes, we applied three machine learning techniques: Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machine-Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE). We validated our findings with external datasets and checked their accuracy using ROC curves. Additionally, we performed single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) on the key genes. We also used the DSigDB database to predict potential drugs that could help treat heart failure patients affected by respiratory infections. Lastly, we analyzed immune system responses to explore how they might contribute to heart failure in these patients. Figure 1 shows the flow of the study.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

This study’s data were sourced from the publicly accessible GEO database12, with prior consent and ethical clearance obtained for the datasets involved, eliminating the need for institutional review board approval. For heart failure analysis, we utilized dataset GSE57338, containing left ventricular myocardial samples from 95 ischemic heart failure patients and 136 controls13. We randomly selected 70% of the samples to be assigned to the training set for data analysis and the remaining 30% to be assigned to the test set. The dataset GSE5406, as an independent dataset, was used for external validation of the machine learning model. This dataset includes samples from 108 patients with ischemic heart failure and 16 controls14. Influenza-related analyses were based on GSE111368, featuring whole blood samples from 229 influenza patients and 130 controls15. The COVID-19 dataset, GSE157103, included leukocyte samples from 100 patients and 26 controls16, while the community-acquired pneumonia dataset, GSE196399, involved leukocyte samples from 56 patients and 21 controls17. For the respiratory disease datasets’ validation, we employed GSE164805, GSE185576, and GSE9491618. The detailed information of the dataset is shown in Table 1.

Data processing and differentially expressed gene screening

Data preprocessing was conducted using R software (version 4.4.0). We excluded probes linked to multiple molecules, retaining only the highest signal probe for each molecule. Batch effects were corrected by sva package, and probe IDs were mapped to gene symbols using the platform’s annotations (The annotation information for each platform is fixed). For the respiratory disease datasets, differential expression analysis was executed with the limma package (Version 3.58.1, Default Parameters), identifying genes as differentially expressed based on p-values < 0.05 and |log2(FC)|≥ 119.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis and module gene selection

We applied Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to explore gene modules related to heart failure (Version 1.72-5)20. WGCNA is a method to identify clusters of genes (called modules) with similar gene expression patterns, which can then be studied for associations with specific biological traits or disease states. Initially, we used a 0.5 threshold in the goodSamplesGenes function to filter out unsuitable genes and samples, leading to the construction of a scale-free co-expression network. We then determined the soft-thresholding power at β = 30 and set scale-free R2 to 0.9 for adjacency calculations, which was transformed into a Topological Overlap Matrix (TOM) to assess gene ratios and dissimilarities. Genes with similar expression patterns were clustered into modules via average linkage hierarchical clustering, with a preference for larger modules by setting the minimum module size at 200. Finally, after calculating the dissimilarity of module eigengenes, we selected a cut-off for the module dendrogram to merge specific modules for deeper analysis and visualized the eigengene network.

Functional enrichment analysis

To comprehend the shared molecular characteristics of the three respiratory infectious diseases (COVID-19, influenza, and CAP) and their potential impact on heart failure, we initially intersected the differentially expressed genes of these three respiratory infectious diseases to identify their common genes. Subsequently, we intersected these common genes with the key modules identified by WGCNA for heart failure, thereby screening for candidate genes that may contribute to the exacerbation of heart failure by respiratory infectious diseases. To explore the biological processes and functions involving these genes, we conducted Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses using the clusterProfiler package (Version 4.10.1, Default Parameters, Analysis date was 07 Jun 2024)21,22.

Machine learning

We utilized three machine learning algorithms—LASSO23, RF24, and SVM-RFE25—to identify key genes involved in the exacerbation of heart failure by respiratory infectious diseases26. By combining these three methods, their respective advantages can be fully utilized, such as the sparsity and feature selection capabilities of LASSO, the high-dimensional data processing and generalization capabilities of RF, and the feature selection accuracy of SVM-RFE. At the same time, their defects can be complemented to a certain extent. For example, LASSO and SVM-RFE can reduce the shortcomings of RF in feature selection, while RF’s high-dimensional data processing capabilities can alleviate the limitations of LASSO on high-dimensional data. Combining these methods, key genes can be identified and verified more comprehensively, and the accuracy and reliability of the analysis can be improved. The LASSO algorithm was executed with the glmnet package, using ten-fold cross-validation to highlight significant genes. The RF algorithm, conducted with the randomForest package, selected genes with higher scores as candidates. The SVM-RFE algorithm, implemented via the e1071 package, identified the number of genes with the highest accuracy as candidates. All machine learning algorithms used default parameters. Ultimately, we determined the key genes by selecting the intersection of the three sets.

Key genes verification

To confirm the accuracy and reliability of the key genes identified, we validated them using datasets related to heart failure and respiratory diseases. We assessed their diagnostic accuracy by constructing Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and quantifying their performance through the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the ROC. We deemed key genes with an AUC > 0.7 as accurate and reliable.

Single sample gene set enrichment analysis

We performed single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) for the key genes using the clusterProfiler package (default parameters) to explore the functions involved in the exacerbation of heart failure by respiratory infectious diseases27. ssGSEA is an extension of the GSEA method, which allows the analysis of gene expression data of a single sample. Its core idea is to convert the gene expression profile of a single sample into a gene set enrichment profile, so that the cell state can be described according to the activity level of biological processes and pathways, rather than relying solely on the expression level of a single gene.

Drug prediction

The Drug Signatures Database (DSigDB) is a comprehensive database designed to facilitate the association studies between gene sets and drug characteristics28. It includes the effects of various drugs on cells and the gene expression changes induced by these drugs, providing valuable resources for drug repurposing and new drug discovery. We compiled a list of the previously identified key genes and utilized the DSigDB database to predict potential drug molecules that may alleviate symptoms and cardiac burden in heart failure patients, particularly those exacerbated by respiratory infections. P-value correction was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg method, thereby increasing the chance of discovering truly significant genes while maintaining a low false positive rate.

Immune infiltration analysis

We employed the CIBERSORT package to analyze the composition of immune and stromal cells in myocardial samples, aiming to illustrate the cellular heterogeneity in myocardial expression profiles and perform immune cell infiltration analysis29. Bar plots visualized the proportions of various immune cells across samples. We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare cell distribution differences between heart failure and normal groups, considering p < 0.05 as the significance threshold.

Results

Respiratory diseases have 51 signature genes

After completing data processing and differential expression analysis, we identified 215 differentially expressed genes for influenza, 1315 for COVID-19, and 5989 for community-acquired pneumonia. By intersecting the differentially expressed genes of the three diseases, we obtained 51 specific genes associated with respiratory infectious diseases, as illustrated in Fig. 2A.

Results of Differentially Expressed Genes and WGCNA. (A) 51 specific genes associated with respiratory infectious diseases. (B) Gene co-expression modules represented by different colors under the gene tree. (C) 9 gene co-expression modules. (D) Intersection of genes in respiratory infectious diseases and heart failure. CAP: community-acquired pneumonia. HF: heart failure.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis identified 10 respiratory disease-related genes that aggravate HF

Using WGCNA, we identified nine gene co-expression modules relevant to heart failure. Notably, the yellow module, containing 1033 genes, showed the strongest correlation with heart failure (correlation coefficient = 0.75, p = 2e−31), marking it as the key module for further study. By comparing the genes in this module with those associated with respiratory diseases, we pinpointed 10 genes potentially critical in worsening heart failure due to respiratory infections. These findings are illustrated in Fig. 2B–D.

Enrichment analysis results of related genes

We conducted GO and KEGG enrichment analyses on the 51 genes specific to respiratory diseases and the 10 genes that may play critical roles in exacerbating heart failure caused by respiratory infectious diseases. The GO enrichment analysis categories included Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF).

For the 51 genes specific to respiratory diseases, the BP terms were primarily linked to defense response to Gram-negative bacterium, antimicrobial humoral response, defense response to bacterium, antibacterial humoral response, and innate immune response in mucosa. The CC terms were mainly associated with primary lysosome, azurophil granule, secretory granule lumen, cytoplasmic vesicle lumen, and vesicle lumen. The MF terms were predominantly connected to lipopolysaccharide binding, serine-type endopeptidase activity, serine-type peptidase activity, serine hydrolase activity, and heparin binding. KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that these 51 genes were primarily involved in Staphylococcus aureus infection, NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, Transcriptional misregulation in cancer, Neutrophil extracellular trap formation, and Hepatitis C.

For the 10 genes that may play critical roles in exacerbating heart failure caused by respiratory infectious diseases, the BP terms were primarily associated with response to virus, negative regulation of viral genome replication, regulation of viral genome replication, negative regulation of viral process, and defense response to virus. No significant results were obtained for CC terms. The MF terms were mainly linked to double-stranded RNA binding, caspase binding, immunoglobulin binding, GTP binding, and adenylyltransferase activity. KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that these genes were mainly involved in Hepatitis C, Influenza A, Measles, Coronavirus disease—COVID-19, and Epstein-Barr virus infection. The visualization results are shown in Fig. 3.

Functional Enrichment Analysis. (A) Enrichment analysis results of 51 specific genes associated with respiratory infectious diseases. (B) Enrichment analysis results of 10 key genes. BP: Biological Process. CC: Cellular Component. MF: Molecular Function. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

RSAD2 and IFI44L are key genes respiratory disease-related genes that aggravate HF

We utilized three machine learning algorithms—LASSO, RF, and SVM-RFE—to refine our search for key genes. LASSO pinpointed 2 potential genes, while RF identified 5 potential genes with importance scores above 7. SVM-RFE highlighted 7 genes as having the highest accuracy and lowest error rate. By analyzing the intersection of these algorithms’ results, we identified RSAD2 and IFI44L as the key genes, with the visualization presented in Fig. 4.

Machine learning in screening key genes. (A) Key genes screening in the Lasso model. As λ increases, the values of the model coefficients gradually decrease from 9 to 2, which indicates that some coefficients are compressed to 0 as the regularization strength increases. The value of the binomial deviation gradually increases from 1.05 to 1.35. This indicates that the goodness of fit of the model may decrease as the regularization strength increases. The results show that when the λ value is 2, a balance is achieved between the goodness of fit of the model and the complexity of the model. (B) Key genes in the random forest (RF) model. The horizontal axis represents the number of trees in the RF, and the vertical axis represents the error. As the number of trees increases, the error of the RF model will gradually decrease. We sort the genes screened by importance. (C) Key genes in the SVM-RFE model. The horizontal axis represents the number of features. The results show that changes in the number of features will change the accuracy and error of the model. When the number of features is 7, the highest accuracy and the lowest error are obtained. (D) Venn diagram shows that 2 key genes are identified via the above three algorithms. LASSO: Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator. SVM-RFE: Support Vector Machine-Recursive Feature Elimination. RF: Random Forest.

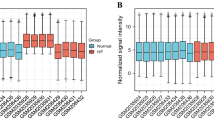

Validation of key genes in multiple datasets

We first verified the accuracy of RSAD2 and IFI44L in myocardial samples, including the internal validation set GSE57338 and the external validation set GSE5406. The results indicated that the AUCs of both genes were greater than 0.7 in both the internal and external validation sets. Subsequently, we validated these two genes in external datasets for influenza, COVID-19, and community-acquired pneumonia. The results showed that RSAD2 and IFI44L had high accuracy in the COVID-19 validation set, with AUCs greater than 0.7. In the influenza validation set, only RSAD2 had an AUC greater than 0.7. In the community-acquired pneumonia validation set, only IFI44L had an AUC greater than 0.7. The visualization results are shown in Fig. 5.

Validation of the precision of pivotal genes. (A) Expression of pivotal genes in heart failure patients relative to healthy controls in dataset GSE57338-train. (B) The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of each pivotal gene in GSE57338-test. (C) The ROC curve of each pivotal gene in GSE5406. (D) The ROC curve of each pivotal gene in influenza dataset. (E) The ROC curve of each pivotal gene in COVID-19 dataset. (F) The ROC curve of each pivotal gene in Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) dataset.

Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis on RSAD2 and IFI44L

We performed ssGSEA on RSAD2 and IFI44L. The results indicated that during the progression of heart failure (HF), RSAD2 is primarily involved in functions such as complement and coagulation cascades, interactions between viral proteins and cytokines and cytokine receptors, proteasome, and compound metabolism. IFI44L is mainly involved in myocardial contraction, the intestinal immune network for IgA production, and various compound metabolism functions. Detailed results are shown in Fig. 6.

Drug prediction of RSAD2 and IFI44L

We utilized the DSigDB database to predict potential drug molecules that may alleviate symptoms and cardiac burden in heart failure patients, particularly those exacerbated by respiratory infections. We selected drugs with an adjusted P-value less than 0.01, identifying a total of 6 drugs: acetohexamide, Gadodiamide hydrate, suloctidil, 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine, testosterone enanthate, and tamoxifen. Detailed information is provided in Table 2.

Immune infiltration analysis of HF

We conducted immune infiltration analysis on myocardial samples from the training set using the CIBERSORT algorithm. The bar plots clearly depicted the composition of different subpopulations in each sample. We evaluated the heterogeneity of cellular composition between heart failure samples and healthy samples. The results indicated significant disparities in the infiltration of 8 types of immune cells. This could offer novel insights into comprehending the mechanisms through which respiratory infections worsen heart failure and potentially provide regulatory points for treating heart failure patients affected by respiratory infections. The visualization results are presented in Fig. 7.

The immune cell infiltration analysis in the GSE57338-train dataset, comparing HF and control groups. (A) The distribution of 22 types of immune cells across different samples, as depicted in a bar plot. (B) The expression of dysregulated immune cells between HF patients and controls, visualized using a violin plot.

Discussion

Winter is a peak season for cardiovascular diseases, and infectious diseases such as influenza also tend to be prevalent during this time. Therefore, the importance of special care for heart failure patients in winter cannot be overstated. Respiratory infectious diseases such as COVID-19, influenza, and CAP have high incidence and mortality rates, potentially leading to severe complications that exacerbate the overall health burden. For instance, CAP is associated with a range of cardiac complications, including arrhythmias, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction, which can result in hospitalization and long-term mortality30. Similarly, COVID-19 has been shown to cause severe acute respiratory infections (SARI), with outcomes comparable to other causes of SARI, necessitating prolonged hospital stays and intensive care31. Given the significant impact of these respiratory infectious diseases on cardiovascular health, understanding their molecular mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets is crucial.

In this study, we focused on the common molecular characteristics of respiratory infectious diseases and their potential impact on heart failure. By integrating datasets from three major respiratory infectious diseases, we identified 51 specific genes associated with respiratory infections. Enrichment analysis revealed that the shared molecular features of these three respiratory infectious diseases primarily involve innate immune responses, inflammation, and coagulation pathways. Defense responses to various bacteria, innate immune responses in mucosa, and the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are crucial defense mechanisms in respiratory infectious diseases32. However, it is important to note that excessive NETs formation can also lead to tissue damage33. NOD-like receptors are intracellular pattern recognition receptors that can recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns. Activation of the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway can trigger inflammatory responses and cell death to combat pathogen invasion34. Heparin-binding proteins and serine-type peptidases play roles in regulating inflammation and coagulation. In respiratory infectious diseases, altered activity of these factors may affect the extent of the inflammatory response and tissue repair processes35.

To understand the mechanisms by which respiratory infectious diseases exacerbate heart failure, we conducted enrichment analysis on 10 key genes. The results indicated that these genes are primarily involved in immune responses following viral infection, cell death, and inflammatory responses. Viral infections activate the body’s immune system to eliminate invading virues. However, this immune response, while clearing the virus, can also cause damage to the heart. Accumulation of viral antigens and inflammatory cells can directly harm myocardial cells, leading to myocarditis and myocardial cell dysfunction36. Additionally, cytokine storms induced by viral infections, such as the excessive release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), can exacerbate cardiac inflammation and injury37. Viral infections can also activate host immune cells to release pro-apoptotic signaling molecules, such as Fas ligand and TRAIL, thereby accelerating myocardial cell death38. The inflammatory response triggered by viral infections is another key factor in the exacerbation of heart failure. Viral infections activate the host’s innate immune system, leading to the infiltration of numerous inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils, into the heart, releasing inflammatory mediators like interleukins and interferons. These inflammatory mediators not only exacerbate cardiac inflammation but also affect the electrophysiological properties and contractile function of the heart, further worsening the symptoms of heart failure39.

Using machine learning algorithms, we identified RSAD2 and IFI44L as key genes and validated their high accuracy (AUC > 0.7), further demonstrating their potential as biomarkers for disease progression and therapeutic targets. RSAD2, also known as viperin, is an interferon-induced protein containing a radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) domain. It plays a crucial role in the innate immune response against viral infections. Studies have shown that RSAD2 exhibits broad-spectrum antiviral activity by inhibiting the replication of various viruses through different mechanisms40. Additionally, RSAD2 is involved in regulating immune responses by promoting dendritic cell maturation via the IRF7-mediated signaling pathway41. In the development of heart failure, RSAD2 is one of the key genes associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and immune cell infiltration42. Therefore, given its importance in the interaction between respiratory infections and heart failure, RSAD2 has the potential to become a therapeutic target. IFI44L is another interferon-induced gene associated with antiviral responses by inhibiting viral RNA synthesis43. During infection, IFI44L promotes macrophage differentiation and the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, thereby exacerbating myocardial injury44. Moreover, ssGSEA results suggest that IFI44L may also be related to myocardial contractile function. Therefore, inhibiting the expression of IFI44L during infection may reduce myocardial damage and protect cardiac function.

Based on the significant roles of RSAD2 and IFI44L in respiratory infectious diseases and heart failure, we used the DSigDB database to predict six potential therapeutic drugs: acetohexamide, Gadodiamide hydrate, suloctidil, 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine, testosterone enanthate, and tamoxifen. Currently, there is no direct evidence indicating the efficacy of the sulfonylurea hypoglycemic agent acetohexamide in treating respiratory infections and heart failure, but controlling blood glucose may indirectly improve the prognosis of heart failure patients45. Testosterone enanthate is an androgen used to treat hypogonadism. Studies suggest that testosterone therapy may improve insulin sensitivity and cardiac function in heart failure patients46. Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties and may reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases47. Although some drugs show therapeutic potential, most require further research to determine their efficacy and safety.

Our study revealed significant differences in immune cell infiltration between HF samples and healthy controls. Consequently, the impact of respiratory infections on immune cells may exacerbate the progression of HF. Research indicates that myocardial samples from SARS-CoV-2 infection models show a significant increase in T lymphocytes and macrophages, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 infection induces an excessive inflammatory response, leading to myocardial remodeling and subsequent fibrosis, thereby worsening HF48. Additionally, severe COVID-19 patients exhibit dysregulated immune responses, particularly cytokine storms that result in systemic inflammation and multi-organ failure49. Dysregulation of monocytes in COVID-19 patients, especially the reduction of the non-classical CD14dimCD16 + subset, is associated with worse clinical outcomes, increasing mortality in patients with respiratory failure and cardiovascular diseases50. The immune response in HF patients with respiratory infections becomes more complex due to the dysregulation of regulatory T cells (Treg) and other lymphocyte subsets. Studies have shown that children with congenital heart disease and bronchopneumonia exhibit altered levels of CD3 + , CD4 + , and CD8 + T cells, indicating impaired cellular immunity, which may predispose them to severe infections and subsequent HF51. Furthermore, macrophages have been implicated in cardiac injury during viral ARDS, with an increase in CCR2 + macrophages leading to cardiac inflammation and dysfunction52. Therefore, understanding the immune status of HF patients in the context of respiratory infections is crucial. The significant differences in immune cell infiltration and associated inflammatory responses provide deeper insights into the mechanisms by which respiratory infections exacerbate HF, paving the way for the development of targeted therapies aimed at modulating immune responses to improve clinical outcomes in HF patients.

The novelty of our study lies in several key aspects. First, we identified the common molecular characteristics of respiratory infectious diseases and their impact on heart failure using bioinformatics approaches. Subsequently, we pinpointed the key genes exacerbating heart failure due to respiratory infectious diseases through three machine learning algorithms and validated these findings across multiple external datasets. We identified six potential therapeutic drugs using the DSigDB database. Finally, we assessed the impact of immune cells on the myocardium, which aids in understanding the mechanisms by which respiratory infections worsen HF.

Despite these advancements, our study has several limitations. It remains unclear whether the elevated mRNA levels will lead to a parallel increase in protein expression, as many biological functions are executed through post-translational modifications. We validated our findings across multiple datasets, further animal experiments and clinical trials are necessary to confirm our results. Although we did not merge the data sets during the analysis, ensuring that the samples were collected by the same institution according to the same standards, factors such as the heterogeneity of the disease itself, sample preservation and contamination, and sequencing technology may have a certain impact on the analysis results. Even if the findings are validated across a number of disease datasets, the GO and KEGG datasets may be more up to date in some analysis tools than in others, and so repeating the functional enrichment analysis on the same disease datasets with another tool could yield slightly different results. Although transcriptomics is convenient for clinical application, the lack of proteomics and metabolomics data limits in-depth study of the mechanisms. Our predicted drugs and immune-targeted therapies have not been validated for relevance and efficacy in clinical settings, necessitating future integration of clinical trials to enhance the reliability of our findings.

Conclusion

Our study successfully identified the common molecular characteristics of respiratory infectious diseases (COVID-19, influenza, and community-acquired pneumonia) and their potential impact on heart failure. Through differential expression analysis, WGCNA, and machine learning algorithms, we pinpointed key genes that may exacerbate heart failure in the context of respiratory infectious diseases. Enrichment analysis and ssGSEA provided insights into the biological processes and pathways involving these genes. Immune infiltration analysis helped us understand the mechanisms by which respiratory infections worsen HF. Finally, we predicted potential therapeutic drug molecules using the DSigDB database. Overall, our findings contribute to a better understanding of the molecular interactions between respiratory infectious diseases and heart failure, paving the way for future research and therapeutic strategies.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: GSE57338, GSE5406, GSE157103, GSE196399, GSE164805, GSE185576, and GSE94916.

References

Kane, S. F. Heart failure: Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. FP Essent. 506, 11–19 (2021).

Fonarow, G. C. et al. Factors identified as precipitating hospital admissions for heart failure and clinical outcomes: Findings from OPTIMIZE-HF. Arch. Intern. Med. 168(8), 847–854. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.8.847 (2008).

Huang, C. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Feb 15;395(10223):496. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30252-X]. Lancet 395(10223), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 (2020).

Bonacina, F. et al. Global patterns and drivers of influenza decline during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 128, 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.12.042 (2023).

Metlay, J. P. & Waterer, G. W. Treatment of community-acquired pneumonia during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Ann. Intern. Med. 173(4), 304–305. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-2189 (2020).

Bai, Y. & Tao, X. Comparison of COVID-19 and influenza characteristics. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 22(2), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B2000479 (2021).

Talbot, H. K. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) versus influenza in hospitalized adult patients in the United States: Differences in demographic and severity indicators. Clin Infect Dis. 73(12), 2240–2247. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab123 (2021).

Ye, Z. et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in COVID-19 based on evidence for COVID-19, other coronavirus infections, influenza, community-acquired pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 192(27), E756–E767. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200645 (2020).

Barzin, A. Heart failure: Right-sided heart failure. FP Essent. 506, 27–30 (2021).

Herzinsuffizienz, D. F. Folge 1: Akute Herzinsuffizienz [Heart failure. 1: Acute heart failure]. MMW Fortschr Med. 141(24), 50–52 (1999).

Herzinsuffizienz, D. F. Folge 2: Chronische Herzinsuffizienz [Heart failure. 2: Chronic heart failure]. MMW Fortschr Med. 141(25), 64–66 (1999).

Barrett, T. et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets–update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D991–D995. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1193 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. RNA-Seq identifies novel myocardial gene expression signatures of heart failure. Genomics 105(2), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2014.12.002 (2015).

Hannenhalli, S. et al. Transcriptional genomics associates FOX transcription factors with human heart failure. Circulation 114(12), 1269–1276. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632430 (2006).

Dunning, J. et al. Progression of whole-blood transcriptional signatures from interferon-induced to neutrophil-associated patterns in severe influenza [published correction appears in Nat Immunol. 2019 Mar;20(3):373. 10.1038/s41590-019-0328-y]. Nat. Immunol. 19(6), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-018-0111-5 (2018).

Overmyer, K. A. et al. Large-scale multi-omic analysis of COVID-19 severity. Cell Syst. 12(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2020.10.003 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. NETosis is critical in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Front. Immunol. 13, 1051140. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1051140 (2022).

Zhang, Q. et al. Inflammation and antiviral immune response associated with severe progression of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 12, 631226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.631226 (2021).

Smyth, G. K. limma: Linear models for microarray data. In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Statistics for Biology and Health (eds Gentleman, R. et al.) (Springer, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-29362-0_23.

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 (2008).

The Gene Ontology Consortium. The gene ontology resource: 20 years and still going strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(D1), D330–D338. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1055 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33(1), 1–22 (2010).

Petralia, F., Wang, P., Yang, J. & Tu, Z. Integrative random forest for gene regulatory network inference. Bioinformatics 31(12), i197–i205. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv268 (2015).

Huang, S. et al. Applications of support vector machine (SVM) learning in cancer genomics. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 15(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.21873/cgp.20063 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Identification of key biomarkers for predicting atherosclerosis progression in polycystic ovary syndrome via bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 183, 109239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109239 (2024).

Huang, J., Zhang, J., Wang, F., Zhang, B. & Tang, X. Comprehensive analysis of cuproptosis-related genes in immune infiltration and diagnosis in ulcerative colitis. Front. Immunol. 13, 1008146. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1008146 (2022).

Yoo, M. et al. DSigDB: Drug signatures database for gene set analysis. Bioinformatics 31(18), 3069–3071. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv313 (2015).

Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12(5), 453–457. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3337 (2015).

Feldman, C. Cardiac complications in community-acquired pneumonia and COVID-19. Afr. J. Thorac. Crit. Care Med. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJTCCM.2020.v26i2.077 (2020).

Pannu, A. K. et al. Severe acute respiratory infection surveillance during the initial phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in North India: A comparison of COVID-19 to other SARI causes. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 25(7), 761–767. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23882 (2021).

Han, L. et al. Transcriptomics analysis identifies the presence of upregulated ribosomal housekeeping genes in the alveolar macrophages of patients with smoking-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon Dis. 16, 2653–2664. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S313252 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes and signaling pathways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease via bioinformatic analysis. FEBS Open Bio 9(11), 1880–1899. https://doi.org/10.1002/2211-5463.12719 (2019).

Wei, L. et al. Comprehensive analysis of gene-expression profile in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron Obstruct. Pulmon Dis. 10, 1103–1109. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S68570 (2015).

Sun, S. et al. Identification and validation of autophagy-related genes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon Dis. 16, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S288428 (2021).

Fairweather, D., Stafford, K. A. & Sung, Y. K. Update on coxsackievirus B3 myocarditis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 24(4), 401–407. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e328353372d (2012).

Mann, D. L. Inflammatory mediators and the failing heart: Past, present, and the foreseeable future. Circ. Res. 91(11), 988–998. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.res.0000043825.01705.1b (2002).

Mangalmurti, N. & Hunter, C. A. Cytokine storms: Understanding COVID-19. Immunity 53(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.017 (2020).

Libby, P. & Ridker, P. M. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: Role of C-reactive protein in risk assessment. Am. J. Med. 116(Suppl 6A), 9S-16S. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.006 (2004).

Honarmand, E. K. A unifying view of the broad-spectrum antiviral activity of RSAD2 (viperin) based on its radical-SAM chemistry. Metallomics 10(4), 539–552. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7MT00341B (2018).

Jang, J. S. et al. Rsad2 is necessary for mouse dendritic cell maturation via the IRF7-mediated signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 9(8), 823. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0889-y (2018).

Yu, H., Yu, M., Li, Z., Zhang, E. & Ma, H. Identification and analysis of mitochondria-related key genes of heart failure. J. Transl. Med. 20(1), 410. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03605-2 (2022).

Kreijtz, J. H., Fouchier, R. A. & Rimmelzwaan, G. F. Immune responses to influenza virus infection. Virus Res. 162(1–2), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2011.09.022 (2011).

Jiang, H., Tsang, L., Wang, H. & Liu, C. IFI44L as a forward regulator enhancing host antituberculosis responses. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 5599408. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5599408 (2021).

Paolillo, S., Scardovi, A. B. & Campodonico, J. Role of comorbidities in heart failure prognosis Part I: Anaemia, iron deficiency, diabetes, atrial fibrillation. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 27, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320960288 (2020).

Cittadini, A., Isidori, A. M. & Salzano, A. Testosterone therapy and cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc. Res. 118(9), 2039–2057. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvab241 (2022).

Cushman, M. et al. Tamoxifen and cardiac risk factors in healthy women: Suggestion of an anti-inflammatory effect. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21(2), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.atv.21.2.255 (2001).

Rabbani, M. Y., Rappaport, J. & Gupta, M. K. Activation of immune system may cause pathophysiological changes in the myocardium of SARS-CoV-2 infected monkey model. Cells 11(4), 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11040611 (2022).

Loganathan, S. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2): COVID 19 gate way to multiple organ failure syndromes. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 283, 103548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2020.103548 (2021).

Mueller, K. A. L. et al. Numbers and phenotype of non-classical CD14dimCD16+ monocytes are predictors of adverse clinical outcome in patients with coronary artery disease and severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cardiovasc. Res. 117(1), 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvaa328 (2021).

Huang, R. et al. Cellular immunity profile in children with congenital heart disease and bronchopneumonia: Evaluation of lymphocyte subsets and regulatory T cells. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 39(4), 488–492. https://doi.org/10.5114/ceji.2014.47734 (2014).

Grune, J. et al. Virus-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome causes cardiomyopathy through eliciting inflammatory responses in the heart. Circulation https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.066433 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Figdraw and Servier Medical Art for providing the drawing materials.

Funding

Our work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (CN) [Grant Nos. ZR2023MH053, ZR2021LZY038].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT authorship contribution statement Yiding Yu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Quancheng Han: Supervision,Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Juan Zhang: Supervision, Software, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Jingle Shi: Supervision, Software, Writing – review & editing. Huajing Yuan: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Yitao Xue: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Yan Li: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Y., Han, Q., Zhang, J. et al. Integrating bioinformatics and machine learning to investigate the mechanisms by which three major respiratory infectious diseases exacerbate heart failure. Sci Rep 15, 23526 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07090-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07090-7