Abstract

This cross-sectional study investigated the correlation between choriocapillaris flow area (CCFA) and retinal vascular changes in diabetic macular ischemia (DMI) using optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA). Age-matched participants were divided into three groups: control (46 eyes), diabetic without macular ischemia (Non-DMI, 59 eyes), and diabetic with macular ischemia (DMI, 54 eyes). Correlation analyses between CCFA and retinal capillary density were performed using OCTA. Results showed that CCFA was significantly reduced in the DMI group compared to the control and Non-DMI groups (H(2) = 40.526, P < 0.01). CCFA was positively correlated with the density of the superficial and deep capillary plexuses (SCP: H(2) = 40.526, P < 0.01; DCP: H(2) = 30.942, P < 0.001), negatively correlated with the foveal avascular zone perimeter (FAZ-P: H(2) = 7.841, P = 0.02), and positively correlated with the acircularity index (FAZ-CI: H(2) = 20.3, P < 0.001). Our study results show that the choriocapillaris flow area (CCFA) is significantly reduced in patients with diabetic macular ischemia (DMI) and is strongly correlated with retinal capillaries. This may reflect concurrent microvascular impairment in both the retina and choroid. Further longitudinal studies are needed to validate the feasibility of CCFA as a potential imaging biomarker for the early detection and monitoring of DMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common ocular microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) and is the leading cause of blindness among the working-age population worldwide. By 2045, the number of people aged 20–79 with diabetes is projected to reach approximately 783 million globally, with an estimated 160.5 million affected by DR. This poses a serious threat to visual health in the working population and may lead to irreversible vision loss1,2. Diabetic macular ischemia (DMI) is a severe complication of DR and has been shown to be closely associated with poor visual prognosis3,4. The main pathological features of DMI include capillary occlusion, enlargement of the foveal avascular zone (FAZ), and visual decline. Currently, there is still a lack of effective treatment options for DMI5,6.

The introduction of optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) has significantly advanced the study of retinal and choroidal microvascular structures. Numerous studies have demonstrated that changes in retinal capillaries are closely associated with the severity of DR7,8. Although the relationship between the choriocapillaris (CC) and DR remains unclear, some researchers have found that CC alterations show a weaker association with DR compared to retinal capillaries. However, other studies have reported that choriocapillaris perfusion may be reduced even in diabetic patients without clinical signs of DR9,10, suggesting that impaired CC perfusion might play a role in the development of DR. DMI is characterized primarily by macular ischemia. Previous studies have shown that in patients with DMI, in addition to retinal capillary changes and enlargement of the FAZ, a reduction in choriocapillaris perfusion may also occur11. Nevertheless, there is currently a lack of systematic research on the correlation between retinal and choroidal microvascular changes in DMI. Therefore, this study aims to use the quantitative capabilities of OCTA to analyze the relationship between choriocapillaris flow area (CCFA) and retinal capillary parameters in patients with DMI, diabetic patients without DMI, and healthy controls, in order to provide preliminary imaging based evidence for the pathogenesis of DMI.

Results

Among the three patient groups: normal controls (Controls, n = 46), diabetic patients without macular ischemia (Non-DMI, n = 59), and diabetic patients with macular ischemia (DMI, n = 54), no significant difference was observed in age (H(2) = 1.772, P = 0.41, η2 = 0), while a weak difference was found in sex distribution (χ2(2) = 6.044, P = 0.014, Cramér’s V = 0.195) (Table 1). Compared to the control group, the DMI group showed a significant difference in disease duration (Z = − 2.054, P = 0.04, r = 0.19). Since the control group consisted of healthy volunteers without ocular complaints and with normal vision based on routine examinations, BCVA and HbA1c data were not collected for this group, and disease duration was not applicable. Within our study, BCVA (LogMar) differed significantly between the Non-DMI and DMI groups (Z = − 2.449, P = 0.014, r = 0.23), whereas no significant difference was observed in HbA1c levels (Z = − 0.319, P = 0.75, r = 0.030).

Significant differences were found among the three groups in the choroidal capillary flow area (CCFA) (H(2) = 40.526, P < 0.01, η2 = 0.247), superficial capillary plexus (SCP whole) (H(2) = 36.824, P < 0.01, η2 = 0.223), and deep capillary plexus (DCP whole) (H(2) = 30.942, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.186). Furthermore, measurements at FAZ revealed significant differences in area (FAZ-A) (H(2) = 7.566, P = 0.023, η2 = 0.036), perimeter (FAZ-P) (H(2) = 7.841, P = 0.02, η2 = 0.037), and circularity index (FAZ-CI) (H(2) = 20.3, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.117) across groups. No significant differences were observed in OCTA image quality among the three groups (H(2) = 2.324, P = 0.313, η2 = 0.0021).

Intergroup comparative analysis of quantitative OCTA parameters

We performed pairwise comparisons of OCTA quantitative parameters among the three groups using the Mann–Whitney U test, with Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons (adjusted significance level α_adj = 0.05/3 = 0.0167). The results revealed significant differences in several parameters between the DMI group and the other two groups (Table 2).

Specifically, CCFA was significantly lower in the DMI group compared to the normal control group (Control vs. DMI: U = 376, P < 0.001, r = 0.60) and the Non-DMI group (Non-DMI vs. DMI: U = 801, P < 0.001, r = 0.45).FAZ-A showed no significant difference between the DMI group and the other groups (Control vs. DMI: U = 1207, P = 0.809, r = 0.02; Non-DMI vs. DMI: U = 1189.5, P = 0.020, r = 0.23). FAZ-P did not differ significantly between Control and DMI (U = 1061, P = 0.211, r = 0.45), while the difference between Non-DMI and DMI was marginally significant (U = 1428.5, P = 0.008, r = 0.12). FAZ-CI showed significant differences in both comparisons, with notably lower values in the DMI group (Control vs. DMI: U = 564, P < 0.001, r = 0.46; Non-DMI vs. DMI: U = 1236, P = 0.040, r = 0.20).

Furthermore, SCP (whole) differed significantly between Control and DMI (U = 1111.5, P < 0.003, r = 0.59) and between Non-DMI and DMI (U = 1022, P = 0.001, r = 0.32). SCP (fovea) showed no significant differences (Control vs. DMI: U = 409, P = 0.367, r = 0.09; Non-DMI vs. DMI: U = 1212, P = 0.029, r = 0.22). SCP (parafovea) was significantly different in both comparisons (Control vs. DMI: U = 666.5, P < 0.001, r = 0.58; Non-DMI vs. DMI: U = 1058, P = 0.002, r = 0.30).DCP (whole) showed significant differences between Control and DMI (U = 487, P < 0.001, r = 0.52) and between Non-DMI and DMI (U = 1058, P = 0.009, r = 0.26). DCP (fovea) did not differ significantly between Control and DMI (U = 975, P = 0.605, r = 0.19), but was significantly different between Non-DMI and DMI (U = 1136, P = 0.009, r = 0.30). DCP (parafovea) also showed group differences (Control vs. DMI: U = 543, P < 0.001, r = 0.44; Non-DMI vs. DMI: U = 1217, P = 0.030, r = 0.21), with more pronounced differences in the parafoveal region.

Correlation analysis between CCFA and retinal capillary plexuses in the macular region

We analyzed the correlations between CCFA and the superficial and deep retinal capillary plexuses in the macular region (Fig. 1). The results showed that reduced CCFA was significantly positively correlated with the SCP (whole) (r = 0.344, P < 0.001) and DCP (whole) (r = 0.399, P < 0.001). Similarly, CCFA was significantly positively correlated with both the SCP (parafovea) (r = 0.345, P < 0.001) and DCP (parafovea) (r = 0.386, P < 0.001). In contrast, no significant correlation was observed between CCFA and the SCP (fovea) (r = 0.007, P = 0.382), whereas a significant positive correlation was found with the DCP (fovea) (r = 0.222, P = 0.005). Neither inner retinal thickness (r = − 0.018, P = 0.823) nor outer retinal thickness (r = − 0.100, P = 0.208) showed significant correlations with CCFA.

The correlation analysis between CCFA and retinal vascular structural parameters. Spearman correlation analysis between CCFA and SCP and DCP as well as retinal thickness parameters in the macular region. Reduced CCFA was significantly positively correlated with SCP (whole) (P < 0.001) and DCP (whole) (P < 0.001) (a,d). Similarly, CCFA showed significant positive correlations with SCP (parafovea) (P < 0.001) and DCP (parafovea) (P < 0.001) (c,f). No significant correlation was found between CCFA and SCP (fovea) (P = 0.382) (b), whereas a significant positive correlation was observed with DCP (fovea) (P = 0.005) (e). Neither inner retinal thickness (P = 0.823) nor outer retinal thickness (P = 0.208) showed significant correlations with CCFA (g,h).

Correlation analysis between CCFA and FAZ

Next, we performed Spearman correlation analysis between CCFA and FAZ parameters including FAZ-A, FAZ-P, and FAZ-CI across the three patient groups (Fig. 2).The results showed no significant correlation between CCFA and FAZ area (r = − 0.099, P = 0.215), but a negative correlation with FAZ perimeter (r = − 0.167, P = 0.035) and a significant positive correlation with FAZ-CI (r = − 0.242, P = 0.002). Additionally, comparison between Non-DMI and DMI groups revealed a significant negative correlation between CCFA and BCVA (LogMAR) (r = − 0.319, P < 0.001).

The correlation analysis between CCFA and FAZ structural parameters. Spearman correlation analysis between CCFA and FAZ parameters in the three groups (control, non-DMI, and DMI). The results showed no significant correlation between CCFA and FAZ-A (P = 0.215) (a). CCFA was significantly negatively correlated with FAZ-P (P = 0.035) and significantly positively correlated with FAZ-CI (P = 0.002) (b,c). Additionally, CCFA was significantly negatively correlated with LogMAR visual acuity in the non-DMI and DMI groups (P = 0.023) (d).

Adjustment for confounding factors using generalized linear models (GLM)

GLM was used to evaluate the associations between CCFA and various potential covariates. The analysis revealed no statistically significant associations between CCFA and age (β = − 0.001, P = 0.444), gender (β = − 0.043, P = 0.260), duration of diabetes (β = − 0.005, P = 0.073), HbA1c (β = − 0.008, P = 0.220), BCVA (LogMAR) (β = 0.091, P = 0.299). Significance testing was performed using Wald χ2 statistics (Table 3).

Collinearity diagnostics for covariates included in the generalized linear model

Collinearity diagnostics were performed on the covariates included in the GLM, including age, gender, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, and BCVA (LogMAR). The tolerance values ranged from 0.727 to 0.982, all exceeding the threshold of 0.2, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) values ranged from 1.019 to 1.376, all below the commonly accepted cutoff of 5. These results indicate no significant multicollinearity among the variables (Table 4).

Discussion

DMI frequently results in irreversible vision loss and currently lacks effective therapeutic options. Its hallmark features include capillary nonperfusion, enlargement of the FAZ, and progressive visual deterioration10,11. In this study, we employed OCTA to, for the first time, investigate the correlation between CCFA and retinal microvascular parameters in patients with DMI. Our findings revealed that CCFA was significantly reduced in the DMI group compared with both the control and non-DMI groups. Furthermore, CCFA showed a strong positive correlation with both the SCP and DCP, a negative correlation with FAZ-A and FAZ-P, and a significant positive correlation with the FAZ-CI. These results provide robust evidence supporting CCFA as a potential imaging biomarker for the evaluation of DMI.

Although the choroidal and retinal circulatory systems are anatomically independent, both originate from branches of the ophthalmic artery. Approximately 80% of the oxygen supply for photoreceptors comes from the choroid, with the remaining 20% supplied by the retinal vasculature12. Diabetes, as a chronic inflammatory disease, not only damages the retinal microvasculature but also affects the choriocapillaris. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β in diabetic patients lead to thickening of the capillary basement membrane, increased extracellular matrix deposition, and enhanced leukocyte adhesion, causing endothelial cell injury and apoptosis13,14,15. These pathological changes manifest as reduced retinal capillary density and insufficient choroidal perfusion. Leukocyte stasis in retinal capillaries and accumulation of activated neutrophils in ischemic choroidal regions suggest similar pathological mechanisms in both systems16. Decreased expression and activity of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) are associated with microcirculatory dysfunction in the retina and choroid, where nitric oxide (NO) plays a key role in vascular regulation17,18. Deposition of the complement terminal complex C5b-9 around choriocapillaris leads to structural changes and reduced blood flow, potentially triggering retinal vascular abnormalities19. Animal models have also shown reduced choroidal blood flow and abnormal expression of VEGF and CD31, indicating that diabetes may affect choroidal structure and perfusion by regulating VEGF20,21. In summary, diabetes-related inflammatory and immune responses jointly impair the microvascular structure and function of both the retina and choroid.

OCTA can clearly visualize the superficial and deep retinal vascular networks, as well as microvascular changes in CC. As DR progresses, perfusion defects in the CC become more pronounced22. In non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), focal perfusion deficits of the CC can be observed, while in the proliferative stage (PDR), the CC shows widespread and severe ischemia23. Concurrently, the retinal vasculature also exhibits capillary occlusion and perfusion abnormalities24,25. Unlike the retinal circulation, which possesses autoregulatory capacity, the choroidal circulation lacks such a mechanism, and its blood flow decreases as oxygen tension drops26. These studies consistently demonstrate that diabetic patients experience damage to the choriocapillaris, which is closely associated with retinal vascular abnormalities. Our findings align with these results, suggesting that a reduction in CCFA may be related to impaired autoregulatory function of the retinal microvasculature.

FAZ is an important imaging biomarker of DMI, located at the center of the macula and bordered by a ring of capillaries. The underlying outer retinal layer is nourished by the choriocapillaris to maintain tissue transparency and visual function27, making the FAZ highly sensitive to hypoxia28. In diabetic patients, the FAZ area is significantly enlarged, with more pronounced disruption of the capillary ring observed in DCP29. Structural abnormalities of the FAZ are closely associated with the severity of DR30 and are also related to decreased choroidal blood flow31. In patients with PDR, FAZ enlargement is mainly concentrated at the central fovea and accompanied by reduced choriocapillaris vessel density32. In diabetic macular edema (DME), FAZ enlargement is often accompanied by increased choriocapillaris flow voids, indicating impaired choroidal perfusion33. The primary pathological feature of DMI is capillary occlusion at the foveal center, resulting in irregular FAZ borders. FAZ-CI is more sensitive and stable than FAZ-A in reflecting microvascular structural changes34,35. In our study, CCFA was positively correlated with FAZ-P and FAZ-CI, and negatively correlated with BCVA (LogMAR). Previous studies have also shown that CCFA is associated with visual function, and choriocapillaris non-perfusion may play a more critical role than retinal non-perfusion in photoreceptor loss36. In PDR, choroidal perfusion loss is more severe and more strongly correlated with vision impairment than in NPDR37. These findings support the existence of functional coupling between the retinal and choroidal microvasculature. DMI may represent a full-thickness macular perfusion disorder involving both systems. Therefore, CCFA may serve as a promising imaging biomarker for evaluating macular perfusion and predicting the onset and progression of DMI.

Although the choroid supplies the outer retina, the SCP and DCP, supplied by the retinal artery, are more vulnerable to systemic and vascular changes38. In elderly diabetic patients, choriocapillaris alterations often coincide with systemic conditions like hypertension and renal insufficiency, worsening microvascular damage39. In type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients, age and longer disease duration (≥ 10 years) are linked to reduced vascular density in SCP and especially DCP, with greater impact in males, and are associated with HbA1c levels40,41. To account for confounding factors such as age, sex, diabetes duration, and glycation, we used GLM and collinearity diagnostics. Results showed no significant correlations or multicollinearity among the variables.

This study has several limitations. First, as a cross-sectional, single-center study with a small sample size, it could not distinguish the characteristics of different DMI severities (mild, moderate, severe) or determine causal relationships. We plan to conduct a prospective cohort study to observe the dynamic changes in the choroidal and retinal vasculature. Second, although OCTA is highly sensitive for assessing the FAZ, image artifacts and inter-device variability may affect measurement accuracy. A recent prospective study showed that during a 1-year follow-up of DMI patients, the 3 × 3 mm scan mode (Avanti RTVue-XR, Optovue) provided clearer FAZ boundaries than the 6 × 6 mm mode, although manual correction was still required42. In this study, we used the 3 × 3 mm scan mode, preferentially included patients with relatively good visual acuity to reduce the impact of image quality, selected images with quality scores ≥ 7, and manually corrected FAZ boundaries to minimize errors. Additionally, since refractive error may also affect the choriocapillaris to some extent, we included only patients with refractive errors within ± 2.00 diopters and excluded those with a history of high myopia or hyperopia to further reduce the potential bias caused by extreme refractive statuses. However, refractive error was not recorded in this study and will be included in future research. Moreover, patients with diabetic macular edema (DME) and some with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) were excluded, which may have introduced selection bias; we plan to address this in subsequent studies. Finally, because the control group had normal visual acuity and HbA1c levels, complete data collection was not performed; only differences between the DMI and Non-DMI groups were analyzed. In future work, we will complete this data, expand the sample size, and incorporate grading assessments to improve the clinical relevance of the study.

Conclusion

To date, no studies have independently investigated the correlation between choroidal and retinal microvasculature specifically in DMI. In this cross-sectional study, we found that the reduction in CCFA was significantly more pronounced in DMI patients compared to controls and diabetic patients without macular ischemia. The observed concurrent decrease in both retinal and choroidal perfusion, reflected by reduced CCFA, may be involved in the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying irreversible visual loss in DMI. These findings provide preliminary evidence that CCFA is closely associated with retinal microvascular alterations in DMI. Although causality has not been established, further longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the clinical utility of CCFA as a potential imaging biomarker for early detection and disease monitoring in DMI.

Methods

Participants

This study is a cross sectional observational clinical research, This retrospective study was approved by the First People’s Hospital of Zunyi Ethics Committee:approval number: (2022)-1-120, with written informed consent obtained from all participants for the use of their clinical data. All procedures adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Inclusion criteria: (1) Non-diabetic individuals and patients with T2DM; (2) Spherical equivalent refractive error within ± 2.00 diopters ( ≤ ± 2.00D); (3) Axial length between 22 and 24 mm; (4) Diagnosis of DMI based on fluorescein angiography (FFA), defined as disruption and enlargement of the FAZ with or without parafoveal patchy retinal capillary non-perfusion areas. DMI severity was graded according to the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) criteria: mild DMI (FAZ contour disruption involving < 50% of the original perimeter), moderate DMI (FAZ contour disruption involving > 50% of the original perimeter), and severe DMI (complete FAZ contour disruption). Exclusion criteria: (1) Clinically significant DME; (2) Intraocular pressure (IOP) > 21 mmHg or history of glaucoma, refractive error greater than ± 2.00 diopters (> ± 2.00D); (3) Coexisting retinal/choroidal diseases (e.g., anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, retinal vein occlusion, age-related macular degeneration, uveitis); (4) History of ocular trauma or intraocular surgery; (5) Previous retinal laser photocoagulation or intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy; (6) Presence of cilioretinal arteries; (7) Poor-quality imaging due to media opacity or inadequate cooperation (Scan Quality < 7); (8) Systemic comorbidities (e.g., coronary artery disease, anemia, renal diseases).

Blood sample parameters

Blood sample parameters were collected from all diabetic patients during their ophthalmology outpatient visits for HbA1c analysis.

Eye examinations

All subjects underwent BCVA assessment, intraocular pressure measurement, fundus examination using slit-lamp biomicroscopy, ultra-widefield fundus imaging, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) to observe cross-sectional scan images and exclude the presence of DME. Due to the invasive nature of FFA, eyes in the normal control group and Non-DMI group eyes did not undergo FFA examination. FFA was performed on patients diagnosed with DMI (according to the ETDRS grading criteria) to evaluate the morphological structure of the FAZ. All included study eyes were discussed and confirmed by two clinically experienced retina specialists.

OCTA

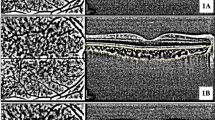

OCTA examinations were performed by a single experienced operator using the RTVue Avanti spectral-domain OCT system (Optovue Inc., Fremont, CA, USA), which employs split-spectrum amplitude-decorrelation angiography (SSADA) technology to detect blood flow signals. Three-dimensional data were obtained through fast transverse scanning along the X-axis and slow transverse scanning along the Y-axis. The system uses an 840 nm light source with an A-scan rate of 70,000 scans per second. At each sampling location, two consecutive B-scans were acquired, each consisting of 8 repeated B-scans, to generate structural and angiographic images. The SSADA algorithm narrows the spectral bandwidth to 45 nm and averages the decorrelation values between spectral bands. A 3 × 3 mm area centered on the macula was scanned, and each B-scan consisted of 304 scan lines to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Automatic segmentation of the retinal and choriocapillaris layers was performed using the built-in Angioanalytics™ software (version 2018.1.1.63, Optovue Inc.), which defined three vascular layers as follows: SCP: inner boundary at 3 μm below the internal limiting membrane, outer boundary at 15 μm below the inner plexiform layer (IPL); DCP inner boundary at 15 μm below the IPL, outer boundary at 70 μm below the IPL; CCFA: located 30–60 μm below the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).Scans with image quality scores below 7 or with obvious motion or segmentation artifacts were excluded. The ETDRS grid was applied to quantify the CCFA within the central 3.144 mm2 region, as well as the VD of the SCP and DCP in the foveal (central 1 mm) and parafoveal (500–1500 μm from the foveal center) zones. In our Optovue AngioVue system, the SCP is defined from the internal limiting membrane to 15 μm below the inner nuclear layer (INL), while the DCP spans from 15 μm below the INL to approximately 15 μm below the outer plexiform layer (OPL), thus encompassing the intermediate capillary plexus (ICP) as well.The measurement of the FAZ using OCTA remains somewhat controversial. Most algorithms include both the SCP and DCP, but the default automatic measurement is based primarily on the DCP. Manual adjustment of segmentation is required to assess the SCP accurately. Although we used the default automatic segmentation mode in this study, we found that automatic FAZ detection in DMI patients often led to substantial errors. Therefore, manual correction was applied. As a result, the FAZ area, foveal retinal thickness, and CCFA were independently measured and manually corrected by two graders (CZX and HHY). FAZ-CI was calculated as the ratio of the perimeter to the circumference of a perfect circle of equivalent area, with values closer to 1 indicating a more circular shape. During quality control, real-time signal strength indicators (green: adequate signal; red: poor signal) were used to assess image quality. Eyes with poor fixation, signal quality scores < 7, artifacts, or media opacities were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 3).

OCTA structural images. Representative OCTA images illustrating structural differences between the control and DMI groups. Images show measurement areas for CCFA, and vascular distribution in the SCP and DCP. Morphological differences in perifoveal capillary arcade circularity between groups are also highlighted, providing a visual reference for evaluating of FAZ configuration.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 29.0, IBM Corporation) and GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0, GraphPad). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a significance level was set at α = 0.05; P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

First, the Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to assess the normality of all continuous variables. Since none of the data followed a normal distribution, continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges [M (P25, P75)]. Comparisons among the three groups (control, Non-DMI, and DMI) were conducted using the Kruskal–Wallis H test. Categorical variables (e.g., gender) were presented as frequencies (n) and compared using the chi-square test. For parameters compared only between the Non-DMI and DMI groups (such as diabetes duration, HbA1c, and visual acuity), the Mann–Whitney U test was used. For OCTA quantitative parameters that showed significant differences among the three groups (including CCFA, SCP, DCP, FAZ-A, FAZ-P, FAZ-AI, inner retinal thickness, and outer retinal thickness), pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test, with Bonferroni correction applied to adjust for multiple comparisons. To further explore the correlations between CCFA and retinal microvascular parameters (e.g., SCP, DCP, FAZ) among the three groups, Spearman rank correlation analysis was performed. GLM was then used to adjust for potential confounding factors (e.g., age, diabetes duration, HbA1c), and collinearity diagnostics were conducted to ensure the robustness of the model and validate the independent associations between CCFA and retinal microvascular parameters.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Sun, H. et al. IDF Diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diab. Res. Clin. Pract. 183(109119), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres109119 (2022).

Tan, T. E. & Wong, T. Y. Diabetic retinopathy: Looking forward to 2030. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 13(1–8), 1077669. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo1077669 (2022).

Cheung, C. et al. Diabetic macular ischaemia: A new therapeutic target. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 89(101033), 1–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres101033 (2022).

Usman, M. An overview of our current understanding of diabetic macular ischemia (DMI). Cureus 10(e3064), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus3064 (2018).

Mohite, A. A., Perais, J. A., McCullough, P. & Lois, N. Retinal ischaemia in diabetic retinopathy: Understanding and overcoming a therapeutic challenge. J. Clin. Med. 12, 2406. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062406 (2023).

Duffy, B. V. et al. Foveal avascular zone enlargement correlates with visual acuity decline in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmol. Retina https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oret.2024.12.015 (2024).

Małyszczak, A., Przeździecka-Dołyk, J. W., Szydełko-Paśko, U. & Misiuk-Hojło, M. Retinal and choroidal vascularization parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes without diabetic retinopathy. Clin. Ophthalmol. 18, 3019–3029. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH (2024).

Terada, N. et al. Quantification of dilated deep capillaries in diabetic retinopathy on optical coherence tomography angiography. Sci. Rep. 3(1), 17884. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44848-3 (2023).

Ryu, G., Kim, I. & Sagong, M. Topographic analysis of retinal and choroidal microvasculature according to diabetic retinopathy severity using optical coherence tomography angiography. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 259(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-020-04785-7 (2021).

Dai, Y. et al. Microvascular changes in the choriocapillaris of diabetic patients without retinopathy investigated by swept-source OCT angiography. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 61(3), 50–50. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.61.3.50 (2020).

Peng, S. Y. et al. Choroidal changes in patients with diabetic retinopathy: A retrospective study. Diagnostics (Basel) 14(5), 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14050537 (2024).

Scuderi, L., Fragiotta, S., Di Pippo, M. & Abdolrahimzadeh, S. The role of diabetic choroidopathy in the pathogenesis and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(12), 10167. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241210167 (2023).

Chen, Y. L. et al. Serum TNF-α concentrations in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients and diabetic nephropathy patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Immunol. Lett. 186, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imlet.2017.04.003 (2017).

Gomułka, K. & Ruta, M. The role of inflammation and therapeutic concepts in diabetic retinopathy-a short review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(2), 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021024 (2024).

Roy, S. & Kim, D. Retinal capillary basement membrane thickening: Role in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 82(100903), 1–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100903 (2021).

Lutty, G. A. Diabetic choroidopathy. Vis. Res. 139, 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2017.04.011 (2017).

Kone, B. C. Molecular biology of natriuretic peptides and nitric oxide synthases. Cardiovasc. Res. 51(3), 429–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00327-3 (2021).

Sakurai, M., Higashide, T., Takeda, H. & Shirao, Y. Characterization and diabetes-induced impairment of nitric oxide synthase in rat choroid. Curr. Eye Res. 24(2), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1076/ceyr.24.2.139.8163 (2002).

Gerl, V. B. et al. Extensive deposits of complement C3d and C5b-9 in the choriocapillaris of eyes of patients with diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 43(4), 1104–1108 (2002).

Muir, E. R., Rentería, R. C. & Duong, T. Q. Reduced ocular blood flow as an early indicator of diabetic retinopathy in a mouse model of diabetes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53(10), 6488–6494. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-9758 (2012).

Matsathit, U., Komolkriengkrai, M. & Khimmaktong, W. Glabridin and gymnemic acid alleviates choroid structural change and choriocapillaris impairment in diabetic rat’s eyes. World J. Diab. 16(3), 97336. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v16.i3.97336 (2025).

Coscas, G., Lupidi, M., Coscas, F., Chhablani, J. & Cagini, C. Optical coherence tomography angiography in healthy subjects and diabetic patients. Ophthalmologica 239(2–3), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1159/000485323 (2018).

Nesper, P. L. et al. Quantifying microvascular abnormalities with increasing severity of diabetic retinopathy using optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 58(6), BIO307–BIO315. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.17-21787 (2017).

Li, L. et al. Quantitative analysis of retinal and choroid capillary ischaemia using optical coherence tomography angiography in type 2 diabetes. Acta Ophthalmol. 97(3), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14076 (2019).

Conti, F. F. et al. Choriocapillaris and retinal vascular plexus density of diabetic eyes using split-spectrum amplitude decorrelation spectral-domain optical coherence tomography angiography. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 103(4), 452–456. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-311903 (2019).

Nickla, D. L. & Wallman, J. The multifunctional choroid. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 29(2), 144–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.12.002 (2010).

Provis, J. M., Dubis, A. M., Maddess, T. & Carroll, J. Adaptation of the central retina for high acuity vision: Cones, the fovea and the avascular zone. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 35, 63–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.01.005 (2013).

Joyal, J. S., Gantner, M. L. & Smith, L. Retinal energy demands control vascular supply of the retina in development and disease: The role of neuronal lipid and glucose metabolism. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 64, 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.11.002 (2018).

Cui, Y. et al. Quantitative assessment of OCT and OCTA parameters in diabetic retinopathy with and without macular edema: Single-center cross-sectional analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1275200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.11.002 (2023).

Mansour, S. Z., Hatchell, D. L., Chandler, D., Saloupis, P. & Hatchell, M. C. Reduction of basement membrane thickening in diabetic cat retina by sulindac. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 31(3), 457–463 (1990).

Cao, J., McLeod, S., Merges, C. A. & Lutty, G. A. Choriocapillaris degeneration and related pathologic changes in human diabetic eyes. Arch. Ophthalmol. 116(5), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.116.5.589 (1998).

Sodhi, P. K. et al. The association of neovascularization with optical coherence tomography angiography parameters in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Cureus 15(5), e39633. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.39633 (2023).

Thaker, S., Kumar, V., Singh, U. & Kumar, S. Novel optical coherence tomography angiography biomarkers in the diagnosis and assessment of diabetic macular edema and diabetic macular ischemia in patients with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 71(1), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_1294_22 (2023).

Bresnick, G. H. et al. Abnormalities of the foveal avascular zone in diabetic retinopathy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 102(9), 1286–1293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-015-3148-2 (1984).

Shiihara, H. et al. Objective evaluation of size and shape of superficial foveal avascular zone in normal subjects by optical coherence tomography angiography. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 10143. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28530-7 (2018).

Mirshahi, R. et al. Colocalization of ellipsoid zone disruption with capillary nonperfusion in different retinal vascular layers and choriocapillaris on en Face OCT of diabetic patients. Microcirculation 32(1), e70000. https://doi.org/10.1111/micc.70000 (2025).

Ma, D. J., Kim, S. M. & Choi, J. M. Associations of retinal vessel geometry and optical coherence tomography angiography metrics with choroidal metrics in diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 65(13), 31. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.65.13.31 (2024).

Stino, H. et al. Intereye microvascular differences in patients with same-stage diabetic retinopathy revealed by OCTA. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 65(6), 11. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.65.6.11 (2024).

Kang, P., Kim, K. Y. & Shin, H. Y. Association between dyslipidemia and glycated hemoglobin in a population-based study. Metabolites 14(2), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14020092 (2024).

Chan, W. et al. Contribution of systemic factors on macular vessel density: A sex-specific population-based study. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 68(3), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10384-024-01053-7 (2024).

Kim, T. Y. et al. The impairment of the deep vascular complex in prolonged type 2 diabetes patients without clinical diabetic retinopathy. PLoS ONE 17(6), e0269182. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269182 (2022).

Tsai, W. S. et al. A comparison of optical coherence tomography angiography metrics and artifacts on scans of different sizes in diabetic macular ischemia. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 269, 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2024.09.012 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all clinicians and medical staff for their kind assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zunyi Municipal Science and Technology Project (Grant No. H [2022] 78).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yueling Cui contributed to conception of the study and drafted the manuscript. Hengyan Hua and Zhaoxi Song collected the data. Xinyu Zhao & Wei Tan reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All the patients gave their written consent for the personal and clinical details along with any identifying images to be published in this study.

Consent to participate/consent to publish

This retrospective study was approved by The First People’s Hospital of Zunyi Ethics Committee (approval number: (2022)-1-120).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, Y., Wang, T., Wang, L. et al. Investigation of the impact of choroidal capillary flow area on macular ischemia in diabetic patients. Sci Rep 15, 23615 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07130-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07130-2