Abstract

Efficient resource forecasting in multi-component application scenarios necessitates comprehensive consideration of inter-component dependencies and resource interaction characteristics. Existing methods primarily rely on single-step predictions, adopt univariate models, and ignore inter-component dependencies, making them less effective in addressing complex dynamics in multi-component applications. To address these challenges, this study introduces MMTransformer, a multivariate time series forecasting model designed for multi-component applications. The model offers several innovations: (1) a segmented embedding strategy to effectively capture sequence features; (2) a multi-stage attention mechanism to model intricate inter-variable dependencies; and (3) a multi-scale encoder-decoder structure to adapt to dynamic variations in local and global information. To evaluate the model’s performance, we constructed workload datasets for courseware production and digital human video creation systems using real-world application scenarios, with three key performance metrics established by monitoring core resource states. Experimental results indicate that MMTransformer achieves average reductions of 42.15% in MSE and 35.37% in MAE compared to traditional time series models such as LSTM, GRU, and RNN. Compared to state-of-the-art time series models like Fedformer, Autoformer, and Informer, MSE and MAE are reduced by an average of 27.14% and 25.55%, respectively. The findings confirm that MMTransformer significantly enhances resource prediction accuracy in multi-component applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cloud computing has emerged as a key component of modern IT infrastructure, with its market size expanding rapidly. Statistics show that the global cloud computing market reached $602.31 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 21.2% by 20301. Leveraging high elasticity and flexibility, cloud computing systems can dynamically adapt resource allocation to real-time workload changes. However, to guarantee top-tier Quality of Service (QoS) and prevent Service Level Agreement (SLA) violations, cloud providers tend to overprovision resources to manage demand uncertainties. Although this practice mitigates service interruption risks, overprovisioning wastes resources and inflates costs, while under provisioning can degrade service performance and cause customer attrition2. Consequently, accurate resource allocation tailored to real-time application demands has become a pressing challenge for cloud service providers.

Resource management strategies can be broadly classified into passive and active approaches. Passive methods rely on monitoring system metrics, such as CPU usage and queue length, and trigger resource scaling when thresholds are breached3. While simple to implement, these methods suffer from delayed response times, often resulting in performance degradation4. In contrast, active methods predict future resource needs, allowing for preemptive resource allocation or release. This helps improve utilization, reduce latency, lower costs, and prevent SLA breaches5. Nevertheless, current active methods encounter significant limitations in handling complex application scenarios:

-

(1)

Excessive reliance on single-step predictions Most existing cloud resource prediction methods emphasize single-step predictions6,7,8,9. Single-step prediction involves forecasting only the next time step at each iteration, leading to error accumulation, particularly in long-term forecasting scenarios where accuracy diminishes significantly as the prediction horizon increases. Additionally, in scenarios demanding rapid responses, single-step prediction struggles to offer decision-makers enough lead time to adapt to changes. In contrast, multi-step prediction forecasts multiple future time windows at once. This reduces response time and allows the model to capture long-term dependencies, improving prediction accuracy.

-

(2)

Limitations of univariate time series models Most cloud resource prediction methods rely on univariate time-series models10,11,12,13,14,15,16. These models generally focus on a single resource consumption metric, such as CPU utilization, using its historical data for forecasting. However, in practical applications, there are often strong correlations between different resource variables (e.g., CPU and GPU). Multivariate models leverage these relationships to deliver more accurate predictions. For example, a linear increase in CPU load coupled with a significant rise in GPU load might suggest a shift of computational tasks to the GPU. These interactions underscore the critical role of multivariate time series prediction. Furthermore, univariate models fall short of meeting practical production and operational needs.

-

(3)

Lack of consideration for inter-component dependencies Most existing methods target resource consumption prediction for single components17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. In real-world scenarios, multiple application components frequently share resources and demonstrate cross-time-scale dependencies. For instance, shared resource usage among components can lead to interdependent utilization rates. Moreover, the operation of one component might depend on the completion of a prior component’s execution. Integrating inter-component dependencies into model design would substantially improve prediction accuracy.

To address these challenges, we introduce a multivariate time series resource prediction model specifically designed for multi-component applications. This study is the first to tackle this problem. Our approach develops an innovative framework that captures long-term dependencies in time series and models the complex interactions between variables in multi-component systems. The key contributions of this study are summarized as follows: (1) This study is the first to address the multivariate time series forecasting problem considering resource dependencies among components. High-quality datasets were constructed using two real-world application scenarios to validate the proposed model. These scenarios were selected for their complexity and real-world applicability, providing a robust basis for model validation; (2) A novel Transformer-based framework is proposed, which incorporates Segment-based Embedding (SBE) and Multi-Stage Attention (MSA). This framework efficiently addresses long-sequence modeling challenges and accurately captures the interactions among variables in multi-component scenarios, thereby greatly improving the prediction performance for multivariate time series tasks; and (3) Comprehensive experiments were conducted using the collected datasets to validate the proposed model. This includes analyzing how past and future time window sizes affect prediction accuracy. Comparisons of four traditional models and three state-of-the-art time series prediction models demonstrate the proposed model’s superiority in multi-component resource prediction scenarios.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: “Related work” section reviews related work on time series prediction models. “Methodology” section elaborates on the methodology. “Numerical experiments” section details the experiments and analysis. Finally, “Conclusion” section concludes with the key findings and discusses potential future research directions.

Related work

Numerous methods have been proposed by researchers to address the resource prediction problem in cloud computing28,29,30. However, current studies still face challenges in modeling multi-component interactions, in capturing multivariate dependencies, and in generalizing complex scenarios. To systematically review advancements in this field, this paper categorizes and summarizes existing research from the following perspectives.

Resource prediction in cloud computing

Cloud resource prediction is a fundamental aspect of resource management, focusing on optimizing resource allocation and efficiency amid uncertain and dynamic resource demands. Chen et al.13 suggested that resource provisioning schemes based on demand prediction are instrumental in maintaining service level objectives in cloud systems. To tackle the challenge of resource overprovisioning, they introduced a resource-efficient predictive provisioning system tailored to manage resource surges. Wang et al.18 categorized task arrivals as either periodic or non-periodic and highlighted the nonlinear relationship between requested, allocated, and utilized cloud resources, irrespective of arrival patterns. They emphasized that mapping these relationships using historical and current data is critical for effective cloud resource prediction. Kumaraswamy19 introduced a virtual machine workload prediction method that identifies whether applications are CPU-intensive or memory-intensive by analyzing workload patterns from multiple data centers over various time intervals within a week, enabling resource configuration accordingly. Xu et al.20 developed a predictive mechanism to forecast the periodic resource demands of virtual networks, acknowledging that most virtual networks are long-term and demonstrate periodic resource usage patterns. Iqbal et al.21 proposed a hybrid approach combining a reactive model for under-provisioning and a predictive model for over-provisioning, utilizing polynomial regression to forecast the number of Web and database server instances based on observed workloads. Hisham22 focused on predicting resource demands for CPU, memory, and disk utilization from a cloud consumer perspective. They introduced a swarm intelligence-based prediction approach (SIBPA) that accounts for the long-term dynamics of consumer requests and seasonal or trend patterns in time series data.

Deep learning-based methods for cloud computing resource prediction

The rapid advancement of deep learning has opened new possibilities for cloud resource prediction. Deep neural network models enable researchers to automatically extract resource usage patterns in complex scenarios while uncovering latent time dependencies and nonlinear relationships. Janardhanan14 employed LSTM to predict CPU utilization in data center machines and compared its performance with ARIMA, demonstrating that LSTM achieved superior accuracy and outperformed ARIMA significantly. Given the inconsistencies and nonlinearities in cloud computing workloads, Mahfoud et al.15 proposed an efficient deep learning model leveraging Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Networks (DCRNN). Yadav et al.23 introduced an LSTM-based mechanism for automated scaling, which forecasts server traffic and estimates corresponding resource requirements. Tassawar Ali et al.24 developed a cluster-based differential evolution neural network model to optimize feature weights in deep neural networks for predicting future cloud data center workloads. The model incorporates a novel mutation strategy to balance exploration and exploitation. Bi et al.25 aimed to enhance prediction accuracy by preprocessing data through three distinct methods and by integrating BiLSTM with GridLSTM for training and testing time series datasets.

Methods for multivariate time series prediction

Multivariate time series prediction methods have gained significant attention in resource management, with a core focus on capturing dynamic temporal changes and complex variable interactions. Gupta et al.16 developed diverse multivariate frameworks to enhance predictions of future resource metrics in cloud environments, analyzed techniques for identifying and predicting sets of resource metrics associated with target resource indicators. Their proposed framework for multivariate feature selection and prediction was validated using CPU utilization predictions in Google cluster traces. Ullah et al.26 introduced a multivariate time series-based framework for workload prediction in multi-attribute resource allocation, utilizing a BiLSTM model to forecast resource provisioning and utilization. Jin et al.27 proposed an Enhanced Long-Term Cloud Workload Forecasting (E-LCWF) framework designed for efficient resource management in dynamic and heterogeneous environments. The E-LCWF framework processes individual resource workloads as multivariate time series and enhances performance through anomaly detection and mitigation. Zhang et al.31 introduced Crossformer, a Transformer-based model for multivariate time series prediction, capable of capturing temporal dependencies while effectively modeling cross-dimensional relationships between variables. Wan et al.32 developed a novel framework termed the Feature-Temporal Block to extract both temporal and feature-level information. Each block comprises two components: a feature module employing a gating mechanism to interpret competitive feature interactions, and a temporal module utilizing learnable filters for frequency-domain processing. This innovative structure allows FTMLP to integrate feature and sequence dimensions with both time and frequency-domain information. He et al.33 proposed a Knowledge-Enhanced LSTM (KeLSTM) as the encoder-decoder architecture of T-net, accounting for negative noise from non-predictive variables and temporal differences in prediction importance.

Methodology

Multivariate and multi-component time-series resource prediction tasks encounter dual challenges: high-dimensional complexity and long-term sequence dependencies. To address these issues, this study introduces MMTransformer, a Transformer-based framework that systematically resolves these challenges by integrating segment-based embedding, multi-stage attention mechanisms, and a multi-scale encoder-decoder strategy.

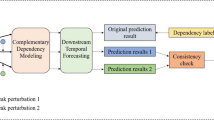

The framework is designed to balance the capture of global temporal patterns with detailed modeling of local features while uncovering inter-variable collaborations. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the modular design comprises three key components: SBE for enhanced temporal feature segmentation, MSA for iterative extraction of relational information, and Multi-Scale Encoder–Decoder (MED) for integrating multi-scale contexts to boost overall prediction accuracy.

Problem description

Consider an application system comprising \(C\) components, each with \(V\) associated variables, where all variables have observed values over a given time window \(\text{T}\). The system’s historical time-series data is denoted by the matrix \({X}_{C}\in {R}^{T\times V}\) where \({X}_{C}\) represents the time-series observations of \(V\) variables for the c-th component. The complete historical time-series data of the system can be expressed as:

where \(\text{T}\) denotes the length of the time window. The aim is to predict the future resource utilization of each component based on these historical data. Specifically, the model aims to learn the relationship between the input sequence \(X\) and the output sequence \(Y\), enabling it to predict multivariate combinations at future time points. The predicted results are defined as:

where \(\text{H}\) denotes the number of future time steps for prediction.

To effectively capture interactions among multiple components and dependencies between variables, the proposed model extracts global temporal features from historical data and improves its capability to analyze dependency structures across components and variables. Specifically, when multiple components share resources and exhibit dependencies, the model must emphasize the coupling relationships in their temporal resource utilization. To address this, the proposed framework integrates multi-component, multivariate, and temporal dependencies to improve prediction accuracy and robustness.

Segment-based embedding

To effectively capture the temporal dependencies between components and variables in time-series data, we propose an SBE framework. This framework segments the time-series data along the temporal axis and maps the raw data into a high-dimensional feature space to extract the temporal characteristics of each segment. This design improves the accuracy of multivariate time-series predictions by facilitating the modeling of interactions among complex components and variables.

SBE’s core innovation lies in its temporal decomposition strategy and the associated linear mapping mechanism. By applying linear transformations and feature reconstruction to each segment of the time-series data, this approach preserves critical information from the original dataset and generates feature sets optimized for subsequent deep learning tasks.

Specifically, for an input sequence of shape \((T,C,V)\), SBE divides the time dimension into fixed-length segments as predefined, reorganizing these segments into a matrix of shape \((C*V*L,S)\), enabling independent processing of each segment’s features. For each time segment, SBE applies a unified linear mapping function to obtain key feature values, specifically expressed as:

Here, \(E\) denotes the embedded feature representation, \(W\) represents the weight matrix of the linear transformation, and \(b\) is the bias term. This mapping embeds the data from each time segment into a \(D\)-dimensional latent space, enabling more effective capture of intra-interval feature patterns while supporting interaction models among complex components.

SBE divides long time series into short segments for independent modeling, effectively capturing local temporal features while improving computational efficiency and gradient stability, making it particularly suitable for multi-component and multivariate time series prediction tasks.

Multi-stage attention

To address the need for modeling complex interactions among variables in time-series data, we propose an MSA module that integrates temporal and channel dual-stage attention mechanisms to effectively capture the dynamic characteristics of multivariate time-series data. This design consists of two core stages: the temporal stage and the dimensional stage, each addressing specific challenges to collectively improve the modeling of complex multivariate interactions. In the temporal stage, it captures cross—time—segment dynamic dependencies; in the channel stage, it adopts a shared routing matrix to encode interactions between components and variables. This mechanism enables the model to capture synchronous and lagged interactions between components (such as shared GPU memory usage).

-

(1)

Temporal stage attention mechanism

Time-series data exhibit pronounced temporal dependencies, and directly modeling dynamic temporal changes aids in capturing the relationships and interactions among variables across the temporal dimension. The temporal stage leverages a multi-head self-attention mechanism to explicitly model temporal dependencies, improving the model’s responsiveness to dynamic variations. For the input tensor \(X\in {R}^{B\times C\times V\times L\times D}\), where \(B\) is the batch size, \(C\) is the number of components, \(V\) is the number of variables, \(L\) is the number of time segments, and \(D\) is the embedding dimension, the time-segment attention mechanism captures the dynamic relationships of variables across time segments using a multi-head attention operation. The specific equation is as follows:

Here, \({W}_{Q}\), \({W}_{K}\), \({W}_{V}\in {R}^{D\times h}\) are the projection matrices for queries, keys, and values, and \({D}_{h}\) is the dimension size of each head. The attention scores for the time-segment layer are then calculated as:

To ensure model stability and information integrity, the time-segment layer further incorporates residual connections and normalization operations:

And enhances the feature representation capability through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP):

-

(2)

Channel stage attention mechanism

In multi-component scenarios, interactions between components and variables can have a significant impact on model performance. To address this, the channel stage models variable interactions in greater detail, enhancing prediction accuracy while reducing computational complexity. Specifically, a shared routing matrix \(R\in {R}^{L\times F\times D}\) (where \(F\) represents the number of routers) is introduced to model channel interactions.

First, the output of the time phase \({O}_{t}\in {R}^{B\times C\times V\times L\times D}\) is reshaped via a dimensional reconstruction operation into \({X}_{dim}\in {R}^{(B*L)\times (C*V)\times D}\) enabling channel-interaction modeling among dimensions through dimension reconstruction for modeling interactions among dimensions to enable channel interaction modeling. The channel stage aims to capture collaborative relationships among components and variables via sending and receiving phases, while maintaining computational efficiency. The specific equations are as follows:

The channel receiving phase distributes interaction information via the routing matrix:

Finally, the output of the channel stage is reshaped back to its original form \({X}_{out}\in {R}^{B\times C\times V\times L\times D}\), with residual connections and an MLP layer applied:

In the dual-stage attention mechanism, the temporal stage focuses on dynamically modeling temporal dependencies, while the channel stage captures interactions among components and variables, with the routing matrix substantially reducing the computational overhead of channel interactions.

Multi-scale encoder–decoder

Encoder

We introduce a multi-scale encoder structure designed to progressively extract multi-granularity features and capture the dynamic evolution of local and global information. The encoder is composed of multiple encoder blocks, each comprising a segment merging layer and several MSA layers.

The segment merging layer primarily serves to combine adjacent data segments along each dimension, producing coarser-grained representations. This approach aggregates local information, reduces sequence length, and enhances the efficiency of processing long sequences. Let the input tensor have a shape \({X}_{padded}\in {R}^{B\times C\times V\times L\times D}\), When the number of sequence segments \(S\) is not divisible by the window size \(w\), padding is applied to the input data to ensure operational integrity. The resulting padded tensor shape is \({X}_{padded}\in {R}^{B\times C\times V\times (L+P)\times D}\)

Here, \(P=w-(L mod w)\). Then, segment merging is used to combine \(w\) adjacent data segments along each dimension to generate a new representation:

Here, LayerNorm is used for normalization, and Linear is a linear transformation for further mapping of the merged features. An encoding block is the basic building unit of the encoder. Each encoding block includes an optional segment merging layer and multiple MSA layers. The depth s of an encoding block determines the number of MSA layers at each scale:

The entire encoder’s architecture progressively extracts features in a multi-scale manner, and its output is a list containing the encoding results for each scale:

Here, \({E}_{s}\) denotes the output from the s-th encoder block. As the scale increases, sequence length decreases progressively, while feature dimensions expand, facilitating the effective fusion of multi-scale information.

Decoder

The decoder aims to integrate encoded results from various scales and incrementally produce the final prediction. The decoder comprises multiple decoding layers, with each layer generating local predictions at its corresponding scale and combining all scale predictions to yield the final output. Each decoding layer comprises an MSA layer and a cross-attention layer.

The MSA layer captures both local and global dependencies in time-series data, while the cross-attention layer dynamically integrates intermediate outputs from the decoding layer with encoded results at the corresponding scale, thereby strengthening multi-scale dependency modeling. Specifically, the output from the preceding decoding layer is first processed by the MSA layer. The cross-attention mechanism then combines this output with the corresponding encoding layer’s result to generate weighted feature representations, further enhancing prediction accuracy.

Here, \({Q}_{D}\), \({K}_{e}\), \({Q}_{e}\) are the query, key, and value feature representations of the decoder and encoder, respectively. After cross-attention, the features are transformed non-linearly using an MLP, which consists of two fully connected layers and utilizes the GELU activation function to enhance feature representation:

Additionally, residual connections and layer normalization are employed to stabilize the training process and enhance generalization capability. Following these steps, each decoding layer produces local prediction results. The final output is computed by aggregating the predictions from all decoding layers:

Here, \({X}^{{Pred}_{i}}\) is the prediction result of the \(i\)-th decoding layer. By progressively extracting time-series features of varying granularity using the multi-scale encoder and integrating these with the decoder for multi-scale fusion and decoding, the MSA module enables efficient modeling of both global and local features. The segment merging layer in the encoder greatly improves the efficiency of processing long sequences, while the decoder leverages multi-layer cross-attention and MSA layers to model intricate temporal dependencies and multivariate relationships, culminating in high-precision predictions.

Numerical experiments

Dataset and implementation details

Existing datasets primarily focus on single-component systems or fail to account for the intricate dependencies among components in multi-component applications, which are crucial for accurate resource prediction. To achieve our research objectives, we constructed two high-quality datasets derived from real-world application scenarios: the Courseware Production system workload Dataset (CPD) and the Digital Human Video Creation system workload Dataset (DHVCD). This section elaborates on the dataset construction process and highlights its key characteristics.

Dataset overview

The datasets developed in this study target two representative application scenarios, each emphasizing the resource usage patterns of three core components to capture the intricate resource consumption characteristics of multi-component applications.

-

(1)

CPD

This dataset originates from an intelligent educational content generation application designed to produce high-quality PPTs based on user-provided prompts. The core components are:

Image Generation Generates images related to the theme based on the given prompts;

Image Expansion Extends the generation of additional images consistent with the theme;

Copywriting Generation Analyzes the generated images and drafts text content that aligns with the PPT.

These components constitute the core functional modules of the application, with resource usage patterns significantly influenced by the dynamics and interactivity of input information, as well as the scale and type of generated content.

-

(2)

DHVCD

The digital human video creation system workload dataset originates from a digital human construction and interaction application designed to generate digital humans from user-input appearances and support real-time interaction. The core components are:

Digital Human Model Inference Processes user-input appearances to infer and generate the basic features of the digital human;

Video Synthesis Synthesizes seamless interactive videos based on the digital human’s appearance;

Service Invocation Enables real-time dialogue between users and the digital human, encompassing both voice and text interactions.

These components collaboratively construct a complete digital human service functionality chain, with dependencies existing among them. Furthermore, its resource usage patterns dynamically evolve based on user interaction intensity and application complexity.

Dataset construction process

To capture resource usage patterns in multi-component application scenarios and offer high-quality support for resource prediction and optimization research, we developed two realistic and fine-grained datasets. The following sections provide a detailed explanation of the dataset construction process across three aspects: collection metrics, collection methods, and collection steps.

-

(1)

Collection metrics

The key to collecting performance data is monitoring and evaluating the core resource states during system operation. This study primarily focuses on the performance of six modules: CPU, GPU, video memory, disk, memory, and network. To ensure the data accurately captures the dynamic nature of multi-component scenarios, multiple components were deployed, focusing on recording regular fluctuations in resource usage while avoiding prolonged inactivity or sustained high loads.

Ideal datasets should demonstrate clear fluctuation patterns with substantial differences between peaks and troughs, improving the accuracy of resource prediction. During the actual collection process, it was observed that disk, memory, and network usage exhibited minimal fluctuations, rendering them insufficient for research purposes. Consequently, the following three core metrics were chosen as the primary focus of the study:

CPU Utilization Indicates the percentage of CPU usage during a specific time period, used to measure the level of CPU resource activity.

GPU Memory Usage Measured in megabytes (MB), reflecting the task’s occupation of GPU memory.

GPU Utilization Indicates the percentage of effective time spent by the GPU executing computational tasks, used to assess the GPU’s actual workload.

These three metrics collectively provide a critical perspective on computational resource usage, encompassing the performance dimensions of CPU and GPU while uncovering their collaborative usage patterns in multi-task scenarios, thereby establishing a robust data foundation for multi-component resource optimization research.

-

(2)

Collection methods

In both the CPD and DHVCD, the three core component services are deployed on servers using Docker containers. The Docker API and Python Docker library are used to obtain performance data for each container, including CPU usage and real-time GPU status (memory usage and utilization). Precise CPU utilization is calculated by measuring time differences and normalizing the data. Data from multiple containers is collected in parallel using a multithreading approach, with a 1-s sampling interval. A streaming interface is employed to extract data sequentially, ensuring temporal consistency.

-

(3)

Collection steps

The overall data collection process is divided into the following three steps: Deploy the services using Docker containers, specifying memory size, CPU core allocation, and GPU device numbers, and open API interfaces to enable external interactions; Write automated scripts to loop through service component startups, randomly set sleep times to simulate real-world usage scenarios, and adjust configurations once the services stabilize for formal data collection; Use collection scripts to access API interface objects for each container and collect metrics such as CPU utilization, GPU memory usage, and GPU utilization via multi-threading, formatting the data and storing it as CSV files.

For the CPD, data was collected once per second, resulting in a total of 40,000 data points; for the DHVCD, data was collected every 5 s, resulting in a total of 55,420 data points. During the data validation process, timestamp comparisons at the beginning, end, and middle ensured that time interval differences were within 0.01 s. The consistency between resource usage trends and scenario characteristics was also observed to further verify the data’s accuracy and reliability.

Finally, the dataset was split into training, validation, and the test sets in a 70%, 10%, and 20% ratio, with the detailed distributions presented in Fig. 2. With this meticulously designed collection process, this study successfully developed a high-quality multi-component resource usage dataset, offering critical support for future research on resource prediction and optimization.

Experimental setup

To ensure uniformity in data features and stability in model learning, zero-mean normalization was applied to the training, validation, and test sets using the mean and standard deviation derived from the training set. The primary goal of the experiment is to assess the model’s prediction performance across various future window sizes \(\text{H}\) and to analyze how past window size (\(\text{T}\)) influences prediction accuracy. During the experiment, we varied the past window size (\(\text{T}\)) to observe its effect on future window prediction performance \(\text{H}\) and identified the optimal \(\text{T}\) value. The process involved incrementally adjusting \(\text{T}\) and selecting the best value based on the model’s predictive performance. Once the optimal \(\text{T}\) was determined, it remained fixed for subsequent experiments.

Batch training was employed in the experiments, with a batch size of 24, 20 epochs, and a segment merging window size \(w=2\). To enhance training efficiency and mitigate overfitting, an early stopping strategy was employed, terminating training if the loss failed to decrease significantly over three consecutive iterations. Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Squared Error (MSE) were utilized as the primary evaluation metrics to comprehensively assess the model’s prediction performance and stability. Optimizing these metrics can more accurately predict system resource requirements (such as GPU memory usage), thus avoiding waste caused by over-allocation of resources and process blockages triggered by insufficient resources.

Experiments were conducted on a system equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 24GB GPU, leveraging its high-performance computing capabilities to ensure reliable and efficient results. For clarity in describing experimental results, the three components in each dataset were labeled as Component A, Component B, and Component C.

Main experiment

The experimental results, presented in Tables 1 and 2, systematically compare the performance of eight model frameworks in multi-component, multivariate resource prediction scenarios. To thoroughly assess the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed MMTransformer model, we conducted a comparative analysis against several representative traditional models (LSTM34, GRU35, and RNN36) and state-of-the-art time-series forecasting models (Transformer37, Autoformer38, Informer39, and Fedformer40). The comparative models range from traditional recurrent networks to the latest self-attention-based methods, ensuring a comprehensive and scientifically rigorous evaluation.

The results in Table 1 for the courseware production system dataset show that MMTransformer consistently outperforms other models in MSE and MAE across all time steps, highlighting its superior capability in complex time-series prediction tasks. For example, under a short past window (24), MMTransformer significantly surpasses the best-performing traditional model, RNN, reducing MSE and MAE by approximately 68.9% and 62.8%, respectively. Compared to the top-performing mainstream time-series model, Fedformer, MMTransformer achieves reductions of 53.4% and 69.0%, respectively.

In the dataset experiment of the digital human video authoring system in Table 2, MMTransformer also demonstrated its strong adaptability and prediction accuracy. In the past short time window (24), MMTransformer’s MSE and MAE indicators decreased by 27.6% and 20.9% relative to the RNN model, and by 5.9% and 1.3% relative to the Fedformer model. However, with the increase of the past time window (e.g. 384), MMTransformer’s MSE and MAE indicators decreased by 13.1% and 19.9% relative to the Fedformer model.

A deeper analysis indicates that MMTransformer’s superior performance is attributed to its innovative multi-scale encoder-decoder architecture and multi-stage attention mechanism. This architecture enables dynamic weight allocation between local and global patterns in time-series data, effectively capturing both short-term dependencies and long-term trends. The segment merging module mitigates feature redundancy and improves the efficiency of modeling high-dimensional multivariate data. The multi-stage attention mechanism strengthens the ability to capture intricate multi-component interactions and adapt to dynamic multivariate variations.

To evaluate the model’s performance in resource prediction across different scenarios, we conducted experiments on the CPD and DHVCD, using an input sequence length of T = 48 and a prediction length of \(H\) =192. For the three primary resource metrics in both datasets (CPU utilization, GPU memory consumption, and GPU utilization), we visually compared the model’s predictions against the actual data, as illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4.

Figure 3 presents the prediction results for the CPD. Compared to the DHVCD, this dataset exhibits more complex resource usage patterns, yet the model achieves high prediction accuracy across all three components and three resource dimensions. The relatively constant GPU memory usage and GPU utilization of Component C in the CPD can be attributed to its nature as a persistent large model service deployed with vllm41. After deployment, GPU memory usage and utilization become fixed. Figure 4 illustrates the prediction results on the DHVCD. The model effectively captures the periodic variation trends in resource usage across the three components (Component A, Component B, and Component C). Specifically, the predictions for GPU memory usage and GPU utilization closely align with the actual values, highlighting the model’s strong capability to capture complex dynamic changes in resource utilization. The prediction accuracy for CPU utilization in Component A is relatively lower due to the significant variability in CPU usage during actual operations. When the component is inactive, CPU utilization is close to 0%, but when active, it fluctuates between 0 and 800% (utilizing 8 CPU cores, hence utilization can exceed 100%).

Ablation studies

Impact of hyperparameters on experimental results

To further evaluate the model’s performance under different parameter configurations, we conducted three sets of ablation experiments, focusing on the effects of past window size \(\text{T}\), fixed segment length S, and the number of attention heads \(N\) on prediction performance. All experiments were performed on the DHVCD.

First, we analyzed the impact of varying past window sizes \(\text{T}\), gradually increasing T from 24 to 384. The results are summarized in Table 3. When \(\text{T}\)=48, the model achieves its optimal performance, as evidenced by the low MSE and MAE values. This suggests that a moderate input sequence length is most effective at capturing short-term dependencies. As \(\text{T}\) increases further, the prediction performance deteriorates (e.g., when \(\text{T}=384\), \(\text{H}=192\), MSE rises from 0.3081 to 0.3205), indicating that excessively long input sequences may introduce irrelevant information, burdening the model’s learning process. When T is too small (e.g., \(\text{T}=24\)), the model exhibits poorer performance, highlighting that short input sequences are insufficient to capture essential contextual information. For consistency, the past window size T was fixed at 48 in all other experiments.

Next, we analyzed the effect of varying segment lengths (\(\text{S}\)) on model performance, gradually increasing S from 3 to 12. The corresponding results are presented in Table 4. When \(\text{S}=6\), the model achieves its best MSE and MAE values, demonstrating that a well-chosen segment length effectively structures the input information. As \(\text{S}\) extends to 12, model performance either stabilizes or slightly declines, indicating that overly long segments may introduce information overload, thereby diminishing prediction accuracy. The adaptability of segment length is especially vital for capturing local temporal dependencies, as both overly short and overly long segments can impair model performance. Therefore, in all subsequent experiments, \(\text{S}\) was set to 6.

Next, we explored how varying the number of attention heads (\(\text{N}\)) affects model performance, increasing N from 2 to 8. The corresponding results are presented in Table 5. Increasing the number of attention heads enhances model performance. When N is increased from 2 to 4, both MSE and MAE exhibit noticeable reductions. However, when N is further increased to 8, performance gains become negligible, and in certain cases, slight degradation is observed. This effect may stem from excessive attention heads increasing model complexity. In small-scale datasets, redundant parameters fail to significantly improve the model’s representational capacity. Consequently, in all subsequent experiments, \(\text{N}\) was set to 4.

The results of the three ablation studies confirm that input sequence length, segment length, and the number of attention heads are critical factors affecting model prediction accuracy. A well-chosen parameter configuration ensures an optimal balance between model complexity and predictive performance.

Therefore, in all subsequent experiments, the parameters were set as follows: \(\text{T}=48\), \(\text{S}=6\), and \(\text{N}=4\).

Effect of network structure on experimental performance

This section analyzes the impact of three crucial components in the proposed network architecture on experimental performance. In this analysis, we use the Transformer model as the baseline, incorporate the SBE model, and subsequently introduce the MSA and MED modules to examine their impact on performance. The results are presented in Table 6.

Initially, without any enhancement modules, the baseline Transformer model demonstrates suboptimal prediction performance, with MSE increasing by 24.0% at \(\text{H}=24\) and 19.9% at H = 384. This suggests that the baseline model has significant limitations in capturing complex temporal dependencies and processing long-sequence tasks.

With the integration of the SBE module, the model exhibits notable improvements across all future windows. Specifically, at \(\text{H}=24\), MSE and MAE decrease by 9.8% and 15.1%, respectively, while at \(\text{H}=384\), they decrease by 13.7% and 23.1%, confirming the SBE module’s effectiveness in capturing essential local features.

When the MSA module is added on top of the SBE module, performance improves further. At \(\text{H}=24\), MSE and MAE decrease by 19.0% and 23.3%, respectively, while at \(\text{H}=384\), reductions reach 19.7% and 29.7%. These results confirm the MSA module’s effectiveness in two-stage attention feature modeling, with particularly notable enhancements in long-sequence tasks. Likewise, integrating the MED module on top of the SBE module leads to further improvements, albeit slightly less than those achieved with the MSA module. Nonetheless, this confirms that the MED module strengthens the model’s ability to represent complex temporal relationships by incorporating multi-level features into the decoding process via a dynamic routing mechanism.

The “SBE + MSA + MED” configuration achieves the best results. At H = 24, MSE and MAE decrease by 20.6% and 24.3% respectively, while at H = 384, the decreases reach 23.8% and 31.7%. These results demonstrate the synergy among the modules: SBE enhances feature representation, MSA captures complex dependencies, and MED fuses multi-scale information. This detailed breakdown clearly illustrates the contribution of each component to the overall model performance, considering both the interdependencies among modules and isolating their independent effects.

Figure 5 visualizes the resource prediction outcomes for different model configurations. To effectively showcase the multi-component and multivariate characteristics of the DHVCD, we select Component A’s CPU utilization, Component B’s GPU memory usage, and Component C’s GPU utilization as the prediction targets, with a future time window of \(\text{H}=192\).

To evaluate the effectiveness of the multi-scale encoding strategy within the MED module, we conducted a systematic analysis of multi-scale encoding results across different prediction step lengths. The results are presented in Fig. 6.

The multi-scale encoding strategy proves highly effective in both short-term and long-term prediction tasks. In short-term prediction tasks, a properly chosen encoding depth significantly improves the ability to model local features. In long-term prediction tasks, global feature extraction can be achieved without excessively deep network layers.

Computational complexity analysis

Table 7 provides a theoretical complexity comparison between our model architecture and other models, where T denotes the past window size, \(\text{H}\) represents the future window size, \(\text{S}\) indicates the segment length in the SBE module, and \(\text{D}\) denotes the number of dimensions.

In the encoder stage, our model partitions the input sequence and applies a scaling mechanism to the segment dimension \(\text{D}\), and thereby reduces complexity to \(O(\frac{D{T}^{2}}{{S}^{2}})\). If S is sufficiently large (indicating appropriate segmentation granularity) or \(\text{D}\) does not increase significantly, our model can sustain low computational costs even for long sequences.

During the decoding phase, our model exhibits a complexity of \(O(\frac{DH(H+T)}{{S}^{2}})\). Compared to the Transformer and other models, our approach demonstrates superior efficiency, particularly when the future window \(\text{H}\) is large.

Beyond theoretical complexity, we also measured real-world resource consumption. MMTransformer maintains GPU memory usage under 24GB even with long future windows (\(\text{H}>3072\)), outperforming Transformer and Autoformer, which exceed this limit. We conducted a comparison of memory usage across different models for varying future window sizes H and analyzed the training speed per batch, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The Transformer and Autoformer models surpassed the 24 GB single GPU memory limit at \(\text{H}=3072\) and \(\text{H}=4608\), respectively.

As shown in the charts, our model achieves the lowest memory usage when \(\text{H}<3072\) and surpasses all other models in training speed, which is highly significant for efficient model training.

Conclusion

To tackle the resource prediction challenges in multi-component applications, this paper introduces MMTransformer, a Transformer-based model. To address the limitations of traditional single-step and single-variable forecasting methods, this model integrates SBE, MSA, and MED. By incorporating these modules, MMTransformer achieves substantial improvements in time-series feature extraction and modeling, demonstrating superior performance in complex multi-component and multi-variable resource prediction tasks.

Furthermore, to validate the effectiveness and superiority of MMTransformer, two real-world multi-component datasets were developed. By analyzing multiple resource metrics, three key indicators were selected. In predicting core resource metrics, MMTransformer exhibits superior performance compared to traditional models (e.g., LSTM, GRU, RNN) and state-of-the-art models (e.g., Fedformer, Autoformer, Informer). Specifically, compared to the best-performing baseline models, MMTransformer achieves a 17.46% reduction in MSE and a 4.49% reduction in MAE, while demonstrating greater stability and accuracy in long-sequence forecasting.

Ablation experiments systematically examined the effects of input length, attention head count, and segment length on model performance, confirming the complementary roles of SBE, MSA, and MED in improving prediction accuracy. Additionally, computational complexity analysis underscores MMTransformer’s efficiency in managing high-dimensional, complex time-series forecasting tasks.

Although current validation focuses on CPD and DHVCD datasets, MMTransformer exhibits promising generalization potential. In future work, we will apply the model to broader application scenarios, such as multi-server orchestration in cloud platforms, distributed edge computing environments, and industrial IoT systems. These tests will further demonstrate its cross-domain adaptability.

In addition, we plan to evaluate MMTransformer on larger-scale public datasets such as the Google Cluster Traces and Azure Telemetry. The model will also be tested on multi-component systems with heterogeneous resources (e.g., CPU-GPU-TPU hybrids) and dynamic workloads, supporting robustness assessment under more realistic conditions.

Lastly, due to real-world limitations, current datasets only cover single-day high-frequency samples. To assess seasonal robustness, we plan to work with industry partners to collect multi-week and quarterly data, validating the model’s long-term prediction performance and adaptability to seasonal fluctuations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reason able request.

References

Dempsey, D. & Kelliher, F. Industry trends in cloud computing. (Pallgrave McMillian, 2018).

Smendowski, M. & Nawrocki, P. Optimizing multi-time series forecasting for enhanced cloud resource utilization based on machine learning. Knowl. -Based Syst. 304, 112489 (2024).

Golshani, E. & Ashtiani, M. Proactive auto-scaling for cloud environments using temporal convolutional neural networks. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 154, 119–141 (2021).

Saxena, D. & Singh, A. K. A proactive autoscaling and energy-efficient VM allocation framework using online multi-resource neural network for cloud data center. Neurocomputing 426, 248–264 (2021).

Rampérez, V., Soriano, J., Lizcano, D., Lara, J. A. & FLAS. A combination of proactive and reactive auto-scaling architecture for distributed services. Futur Gener Comput. Syst. 118, 56–72 (2021).

Amiri, M., Mohammad-Khanli, L. & Mirandola, R. A sequential pattern mining model for application workload prediction in cloud environment. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 105, 21–62 (2018).

Ruan, L., Bai, Y., Li, S., He, S. & Xiao, L. Workload time series prediction in storage systems: A deep learning based approach. Clust Comput. 26, 25–35 (2023).

Bi, J., Li, S., Yuan, H. & Zhou, M. Integrated deep learning method for workload and resource prediction in cloud systems. Neurocomputing 424, 35–48 (2021).

Singh, P., Gupta, P. & Jyoti, K. TASM: Technocrat ARIMA and SVR model for workload prediction of web applications in cloud. Clust Comput. 22, 619–633 (2018).

Ruiz, A. P., Flynn, M., Large, J., Middlehurst, M. & Bagnall, A. The great multivariate time series classification bake off: A review and experimental evaluation of recent algorithmic advances. Data Min. Knowl. Disc. 35 (2), 401–449 (2020).

Shih, S. Y., Sun, F. K. & Lee, H. Y. Temporal pattern attention for multivariate time series forecasting. Mach. Learn. 108 (8–9), 1421–1441 (2019).

Patel, Y. S., Jaiswal, R. & Misra, R. Deep learning-based multivariate resource utilization prediction for hotspots and coldspots mitigation in green cloud data centers. J. Supercomput. 22, 5806–5855 (2022).

Chen, L. & Shen, H. Towards resource-efficient cloud systems: Avoiding over-provisioning in demand-prediction based resource provisioning. In IEEE International Conference on Big Data 184–193 (2016).

Janardhanan, D. & Barrett, E. CPU workload forecasting of machines in data centers using LSTM recurrent neural networks and ARIMA models. In 2017 12th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST), 55–60 (2017).

Al-Asaly, M. S. et al. A deep learning-based resource usage prediction model for resource provisioning in an autonomic cloud computing environment. Neural Comput. Appl. 34 (13), 10211–10228 (2022).

Gupta, S., Dileep, A. D. & Gonsalves, T. A. A joint feature selection framework for multivariate resource usage prediction in cloud servers using stability and prediction performance. J. Supercomput. 74, 6033–6068 (2018).

Dogani, J. et al. Multivariate workload and resource prediction in cloud computing using CNN and GRU by attention mechanism. J. Supercomput. 79 (3), 3437–3470 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Online cloud resource prediction via scalable window waveform sampling on classified workloads. Futur Gener Comput. Syst. 117, 338–358 (2021).

Kumaraswamy, S. & Nair, M. K. Intelligent VMs prediction in cloud computing environment. In 2017 International Conference on Smart Technologies for Smart Nation, 288–294 (2017).

Xu, Z., Liang, W. & Xia, Q. Efficient embedding of virtual networks to distributed clouds via exploring periodic resource demands. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 6 (3), 694–707 (2016).

Iqbal, W., Dailey, M. N., Carrera, D. & Janecek, P. Adaptive resource provisioning for read-intensive multi-tier applications in the cloud. Futur Gener Comput. Syst. 27 (6), 871–879 (2011).

Kholidy, H. A. An intelligent swarm-based prediction approach for predicting cloud computing user resource needs. Comput. Commun. 151, 133–144 (2020).

Yadav, M. P., Yadav, D. K. & Rohit & Resource provisioning through machine learning in cloud services. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47, 1–23 (2022).

Ali, T. et al. Hybrid deep learning and evolutionary algorithms for accurate cloud workload prediction. Computing 106 (12), 3905–3944 (2024).

Bi, J. et al. Integrated deep learning method for workload and resource prediction in cloud systems. Neurocomputing 424, 35–48 (2021).

Ullah, F., Bilal, M. & Yoon, S. K. Intelligent time-series forecasting framework for non-linear dynamic workload and resource prediction in cloud. Comput. Netw. 225, 109653 (2023).

Kim, Y. M. et al. Enhancing long-term cloud workload forecasting framework: Anomaly handling and ensemble learning in multivariate time series. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 12 (2), 789–799 (2024).

Zhang, J., Huang, H. & Wang, X. Resource provision algorithms in cloud computing: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 64, 23–42 (2016).

Masdari, M. & Khoshnevis, A. A survey and classification of the workload forecasting methods in cloud computing. Clust Comput. 23 (4), 2399–2424 (2020).

Amiri, M. & Mohammad-Khanli, L. Survey on prediction models of applications for resources provisioning in cloud. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 82, 93–113 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Yan, J. & Crossformer Transformer utilizing cross-dimension dependency for multivariate time series forecasting. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (2023).

Wang, H. et al. FTMLP: MLP with feature-temporal block for multivariate time series forecasting. Neurocomputing 607, 128365 (2024).

He, X. et al. Multi-step forecasting of multivariate time series using multi-attention collaborative network. Expert Syst. Appl. 211, 118516 (2023).

Graves, A. Long short-term memory. In Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks 37–45 (2012).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323 (6088), 533–536 (1986).

Cho, K. et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder–decoder for statistical machine translation. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (2014).

Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 6000–6010 (2017).

Zhou, T. et al. Fedformer: Frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 27268–27286 (2022).

Wu, H. et al. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 22419–22430 (2021).

Zhou, H. et al. Informer: Beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (2021).

Kwon, W. et al. Efficient memory management for large language model serving with paged attention. In Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 611–626 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Science and Technology Program (No. 2023C01042)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. C. and T. H. wrote the paper and designed the methodology. T. H. designed the experiments. G. C., T. H. and W. Z. conducted the experiments. G. C., T. H., W. Z. and H. B. analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, G., Hu, T., Zhang, W. et al. MMTransformer: a multivariate time-series resource forecasting model for multi-component applications. Sci Rep 15, 29740 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07162-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07162-8